1. Introduction

The Spanish subjunctive poses one of the biggest challenges for both HL and L2 experienced students and its proper use is often regarded as an indicator of proficiency. According to ACTFL’s proficiency levels, the proper use of the subjunctive is regarded as an indicator of an advanced/superior level. In that level, the subjunctive is needed to express and support opinions and produce coherent argumentation in extended discourse.

Collentine (

2010) says that “the acquisition of the subjunctive forms and their meaning continues to be one of the benchmarks for success” (39). Even though it is an important topic in HL and L2 acquisition, the majority of studies have focused on L2 and HL mood distinction abilities either separately or comparatively. The approaches have been as varied as the structures that have been analyzed in previous literature. On the one hand, authors such as

Kanwit and Geeslin (

2014),

Collentine (

1995,

1998,

2003,

2010),

Sánchez Naranjo (

2009),

Adrada (

2016),

VanPatten (

2004)

Gudmestad (

2006,

2012,

2013),

Henshaw (

2012),

Isabelli and Nishida (

2005), and

Borgonovo et al. (

2015) have focused on mood distinction abilities among L2 learners alone. On the other hand, studies including those of

Lynch (

2008),

Montrul (

2007,

2008,

2009),

Montrul and Perpiñán (

2011),

Torres (

2018),

Potowski et al. (

2009),

Mikulski (

2010),

Correa (

2011a,

2011b), and

Mikulski and Elola (

2013) compared the mood distinction abilities of HL and L2 learners. Some of the approaches used in those studies were Universal Grammar (UG), psycholinguistics based on processing, context of learning (study abroad or in the country of origin), or input–output oriented research. Previous studies suggest that HL learners tend to produce higher rates of indicative in contexts in which both indicative and subjunctive are accepted (

Silva-Corvalán 1994,

2003,

2014), and also that HL learners tend to maintain the subjunctive in contexts in which its use is mandatory, as, for example, volition. As

Silva-Corvalán (

2003) claimed, the Spanish verbal system undergoes a change process towards more categorical rules. The subjunctive is kept in mandatory contexts (

El profesor hacía que yo hiciera the problem) and it is replaced by the indicative in contexts in which pragmatic variation is possible (

No creo que estoy de acuerdo). Studies have also demonstrated that differences in production and interpretation abilities can be traced back to differences in how the language has been acquired, i.e., implicitly vs. explicitly. For example,

Potowski et al.’s (

2009) study showed that Processing Instruction and traditional-output instruction (

VanPatten 2004) are beneficial for both groups, even though L2 instructional methods might not always be the most beneficial for HL learners. The results showed that both groups improved significantly on interpretation and production tasks. However, only L2 learners showed significant improvement for grammaticality judgments and, in general, L2 learners showed more gains than their HL counterparts. Heritage speakers did not show significant improvement on interpretation and grammaticality judgment tasks, but showed some improvement on the production task.

Studies including those of

Mikulski (

2010),

Correa (

2011a),

Torres (

2018), and

Montrul and Perpiñán (

2011) compared HL and L2 interpretive and productive abilities and found that the L2 group outperformed the HL group in terms of metalinguistic knowledge. They found that HL students with the best performance had received previous formal instruction in Spanish. In this regard, HL students who had never been exposed to formal instruction in Spanish would be at a disadvantage and have more difficulties following their classmates in the same traditional L2 courses in which grammar is explicitly presented and metalinguistic knowledge is more abundant.

Correa (

2011a) also claimed that L2 learners outperformed HL learners in metalinguistic knowledge across all levels;

Montrul and Perpiñán (

2011) stated that L2 learners (with more previous formal instruction) at all levels were more accurate than their HL peers in distinguishing semantic interpretations with the subjunctive and obtained higher rates of accuracy on a morphology recognition task; and

Mikulski (

2010) concluded that HL participants who had the highest scores were those who had either received formal Spanish instruction or had spent time abroad with a Spanish-speaking family.

Torres (

2018) studied the effect that task complexity had among 81 Hl and L2 learners of Spanish. Participants in his study had to complete either a simple or a complex version of a monologic computerized task that delivered written recasts as corrective feedback but differed according to intentional reasoning demands. The targeted structure was the subjunctive in adjectival relative clauses. His results showed that students who were in the simple group improved more, especially in written production, than those in the complex group.

Additionally,

Lynch (

2008) compared intermediate HL and advanced L2 learners in oral interviews and found that differences among them could largely be attributed to social factors, i.e., exposure to and use of Spanish beyond the classroom setting. The implications that this body of literature has for the present study are that future research should find pedagogical practices that focus on improving HL learners’ explicit knowledge of the subjunctive. As

Mikulski (

2010) said: “as heritage speaker population in the United States increases, it will become more important to learn about the abilities that they bring to Spanish language classrooms. Additional information is needed about how SHL (Spanish Heritage Learners) learner abilities compare with those of SFL (Spanish Foreign Language) learners at different levels and the diversity of SHL learners itself” (

Mikulski 2010, p. 220). The present study is an attempt to find connections between SLA (Second Language Acquisition) and HLA (Heritage Language Acquisition) by providing empirical comparative data regarding the effects of two specific pedagogical approaches in L2 and HL classrooms.

Even though having a proper command of the subjunctive is regarded as an indicator of proficiency, the quantity of studies focusing on the Spanish subjunctive and its pedagogical approaches comparing HL and L2 groups is very limited. This was brought to focus by

Lynch (

2014), who analyzed a total of 105 articles published in the

Heritage Language Journal from 2003 until 2014. His goal was to provide a retrospective view of research on heritage languages during the past two decades “concurrent with the emergence of Heritage Language Acquisition (HLA) as an autonomous field of academic inquiry” (224). He divided them into six categories: (1) language of HL speaker, (2) attitudes and identities of HL, (3) assessment of HL abilities for institutional purposes, (4) literacy, practices, and acquisition of reading or writing abilities, (5) pedagogical approaches, and finally (6) teacher’s beliefs, attitudes, practices, or abilities. Only 5 of the 105 studies had a focus on an empirical examination of pedagogical approaches or classroom practices. Moreover, only 2 out of those 5 used a comparative method (HL-L2) for the investigation.

Models and Conceptual Instruction

Taking Lynch’s data as a starting point, the present study tries to fill that research gap and provide a deeper insight into the creation of new pedagogies suitable for HL and L2 students using MCE (Mindful Conceptual Engagement), which is based on Concept-Based Instruction (CBI) principles. Previous studies have been conducted using Concept-Based Instruction to teach the concepts of verbal aspect (

Negueruela 2003;

García 2017) and verbal mood (

Negueruela 2003;

García Frazier 2013).

Gregory and Lunn (

2012) claim that in CBI, “grammatical concepts such as tense, aspect, and mood must not be represented with ad hoc rules of thumb, but rather with an abstract explanation of the concept that is as complete as possible in order for learners to be able to generalize their use of the concept across a broad range of circumstance” (337).

MCE has only been used to research the teaching of

ser/estar (

Negueruela and Fernández Parera 2016) and motion events (

Aguiló Mora and Negueruela-Azarola 2015) among L2 learners. MCE is based on the principles of Concept-Based Instruction (

Negueruela 2003;

Negueruela and Lantolf 2006), which has its origins in Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory. Whereas CBI promotes the use of conceptual models that are given to students to complete tasks, MCE proposes that students need to create their own version of the model presented to them and then use it to complete the tasks. According to

Negueruela and Lantolf (

2006), such models must be “maximally informative and at the same time generalizable” and they “must allow students to explain their communicative intentions in actual performances” (85). Such models can be flowcharts, pictures, schemas, etc. In the activity of creating and using the model, students internalize the concept(s) being taught. From a sociocultural perspective, internalization is key in order to understand the learning processes and properly organize teaching. As

Negueruela (

2012) said, “internalization is a psychological construct that articulates the world outside us—our external bodily experiences in the contexts in which we live—and the world inside us—our internal experiences, that is, our self-conscious awareness.” In order for learners to internalize a conceptual meaning, they need to engage in the conceptual manipulation of their own model and use it in meaningful communicative activities. In those activities, the model that students create will orient and regulate the students’ thinking processes.

To ensure that models are maximally functional, it is essential that activities completed using these models are purposeful and meaningful.

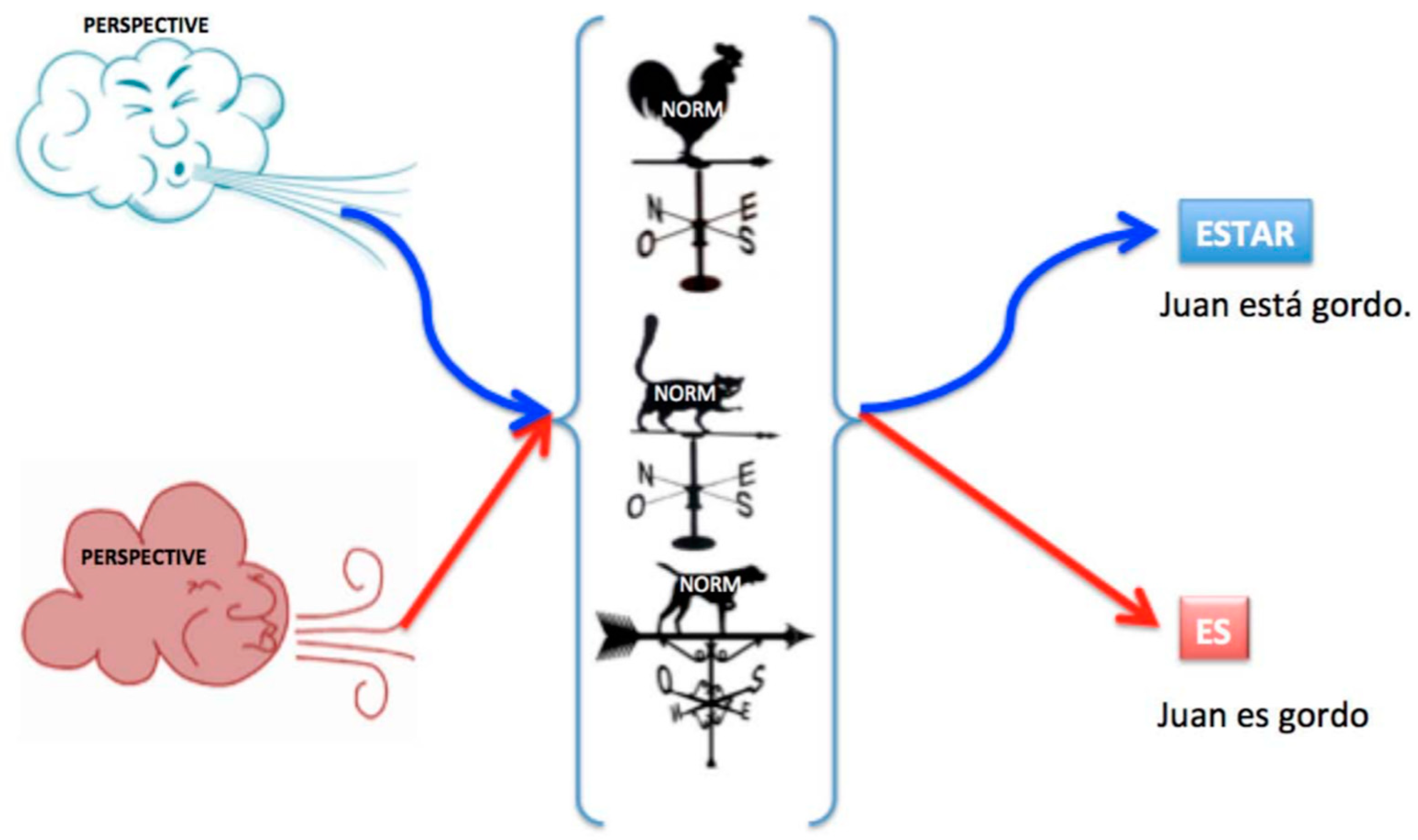

Negueruela and Fernández Parera (

2016) demonstrated the benefits of using models in the Spanish language classroom. The authors taught the different uses of

ser/estar in sentences such as

Juan es gordo and

Juan está gordo (“Juan is fat” vs. “Juan is fatter than usual”). The authors based their model on

Bull’s (

1965) concept of norm. They further explained that “

Bull (

1965) illustrates the use of

ser/estar with regard to normativity through the example of one’s reaction to seeing mountains. Should the mountains conform to one’s expectations,

ser would be employed (

Las montañas son altas or ‘The mountains are tall’) whereas

estar would be used to express surprise, as for instance if the mountains appear higher than expected (

Las montañas están altas or ‘The mountains are taller than usual’). In this case, the speaker’s observation of the height of the mountains did not conform to her expectations, or norms” (205). The authors said that “[…] it was decided to create models around metaphors, thereby representing abstract concepts in terms of familiar, concrete objects” (205). Following Bull’s explanation, the model they created was based on a weather vane or, in Spanish,

veleta, and it is presented in

Figure 1. This model was used by

Negueruela and Fernández Parera (

2016) to represent concepts such as perspective, deviation/following the norm, and the uses of

ser and

estar. Depending on the perspective (blowing cloud), the wind vane (norm), which can have different shapes and sizes, will point towards

ser or

estar. Instead of the example that Bull provided about the mountains (

Las montañas son/están altas), the authors opted to give the example of Juan (

Juan es/está gordo) and chose the red color for the verb

ser and the blue color for the verb

estar.Negueruela and Fernández Parera (

2016) claimed that “evidence of the helpfulness of conceptual models for internalizing concepts is found in differences deriving from the quality of models produced by students in this project” (214). They also found that differences between students could be seen in the quality of their verbalizations. In MCE, conceptual manipulation can be studied by analyzing the verbalizations. Verbalizations are exercises in which students are asked, for example, why they use

ser or

estar in a sentence and the researchers check if they explain why using the concepts that they were taught. The authors found that the students who produced models that were more abstract and generalizable to different communicative situations were those students who internalized the concept being taught. Those students included in their models concepts such as norm, perspective, and deviation/following the norm and they used the concepts in the verbalizations and the worksheets. According to the authors, those were the students who showed a higher degree of internalization in the verbalizations. On the other hand, students who did not include the concepts that were required for the task and did not follow the instructions of the process produced more errors and did not internalize the concepts. They also did not use the concepts in their verbalizations.

Currently, there are no published studies that have applied a comparative HL-L2 methodology using MCE. The importance of the present study lies in the fact that it presents empirical data to support the application of MCE to teach the uses of indicative and subjunctive in variable contexts to HL and L2 students. To do this, the concept of [±EXPERIENCE] (

Bull 1965) was used to teach the variable uses of indicative and subjunctive in adjectival relative clauses such as

Busco unas tijeras que cortan/corten. Production and interpretation exercises were used in pre- and post-test questionnaires to gauge their improvement. Feedback questionnaires were given to measure the attitudes and perceptions towards the MCE process three weeks after the post-test questionnaire had been completed.

In light of the findings from the literature aforementioned, the goal of the study is to compare the efficacy that Mindful Conceptual Engagement has among HL and L2 participants and devise better pedagogies for these two groups.

Valdés (

1995) claimed that “it is time for teachers and applied linguists working in this area to examine their research and practice and to begin to frame an agenda that will guide them in the years to come” (321). This investigation contributes to the growing field of heritage language acquisition and expand the research agenda from a comparative HL-L2 approach. In this regard, it will provide empirical results of the use of MCE to teach the Spanish subjunctive among HL and L2 groups. As previously mentioned, this is an area that has been minimally studied before from the perspectives of sociocultural theory and comparative HL-L2 research. As

Lynch (

2003) affirmed, “the general sorts of questions asked in SLA are questions that HLA researchers must be asking, and the research methodologies used to respond to those questions in SLA are methodologies that would lend themselves fruitfully to HLA endeavors” (26). The following study is based on theoretical principles and pedagogical approaches that have been tested on L2 learners, which in turn will help delineate better methodologies for HL students. The research questions of the present study are four: (1) How will MCE impact the performance of HL and L2 students when comparing the results from the pre-test to the results from the post-test? (2) Will there be any differences according to group and type of task? (3) What are the participants’ attitudes toward and perceptions of the MCE process? and (4) Will there be any differences between groups?

2. Materials and Methods

The number of participants in the study was 26. There were a total of 14 intermediate HL and 12 advanced L2 learners of Spanish. Participants were taught by the same instructor, who was also the researcher. Of the 14 HL participants, eight were born in the South Florida/Miami area, five in the US outside Florida, and one in Venezuela. All L2 participants were from states outside Florida. The university in which this investigation was conducted had a high number of out-of-state students or from other countries (74%). The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 28 years old. The average age of the HL group was 20.3 with a standard deviation of 2.4. The average age of the L2 group was 19.9 and the standard deviation was 2.6. In the L2 group, there were 5 male and 7 female students. In the HL group, there were 2 male and 12 female students.

HL and L2 students were enrolled in two different courses. On the one hand, L2 students were enrolled in an advanced language course that had a focus on literary analysis of short novels, stories, and movies based on the book

Ritos de iniciación: Tres novelas cortas de Hispanoamérica (

Rojo and Steele 1986). The course also used the book

Manual de Gramática by

Dozier and Iguina (

2013) to review several different grammar topics during the semester. Students in the L2 class were placed in that level after they had completed either a placement exam or they had completed the mandatory four semesters of language requirement at the university. The course was designed to prepare students for advanced literature, linguistics, and culture courses. On the other hand, the HL group followed a different syllabus that was based on the book

Taller de escritores (

Bleichmar and Cañón 2016). The course was a general language and culture course with special emphasis on grammar and writing skills. The HL course was the last one of a two-semester sequence that fulfilled the language requirement. In contrast to their L2 peers, HL students at that university were required to take two semesters of Spanish split into a basic and an intermediate-level course. The HL intermediate course was designed for students with some prior instruction in Spanish who, because of family background or social experience, could understand casual spoken Spanish and had some functional communication abilities in the language. There was a special emphasis on cultural and societal aspects of the Spanish-speaking world. Both HL and L2 groups met in person on the same days three times per week for 50 min. It was decided that the most suitable groups to take part in the study were advanced L2 and intermediate HL groups because the uses of the subjunctive that were taught using MCE were already part of the content of those courses.

Table 1 contains the background questionnaire responses that students provided before the intervention.

The materials used for the MCE pedagogical intervention can be divided into four parts: pre-test, class activities, homework, and post-test. Whereas the pre-test, the class activities, and the post-test were conducted in class, the homework was conducted at home. The post-test was administered to students three weeks after finishing the last homework assignment. All assignments were conducted individually.

In Spanish adjectival relative clauses, verbal mood choice is used to convey information about the noun. In this sense, choosing indicative or subjunctive can let speakers know if one is talking about a specific, known, or experienced item (indicative) or not (subjunctive). For example, verbal mood choice would be used to let the speaker know if I am looking for any dress that is red when I go shopping (

Busco un vestido que sea rojo or ‘I am looking for any dress that is red’) or a red dress that I have previously seen and I am aware of its existence (

Busco un vestido que es rojo or ‘I am looking for the red dress’). For that purpose, in the pre-test and the post-test questionnaires, students had to complete a total of 6 interpretation and 6 production exercises. Interpretation and production exercises followed the same structure. The exercises were based upon

Borgonovo et al.’s (

2015) study on mood selection in relative clauses, in which they compared L2 learner performance of different levels and native speakers of Spanish. For the interpretation exercises, students had to read a situation in English and choose between options A or B (indicative or subjunctive). For example, “Francisco just bought a new album by his favorite singer. His friend is at home and he also likes the same singer. However, there is one song that they both really like. Francisco tells his friend.” Once the student had read the context, he/she had to choose between options A or B. In this case, the options were (A) “

Escucha bien que ahora viene una canción que nos gusta mucho” (“Listen, now comes the song that we both like a lot”), and (B) “

Escucha bien que ahora viene una canción que nos guste mucho” (“Listen, now comes a song that we both like a lot”). The correct option would be A because it is in indicative. They both know and have experienced the song that they are talking about. It is that specific song and not any other song they like. For the production exercises, the structure was the same and students were also presented with a situation in English. For example, “Pedro has seen on TV that a famous cereal brand has a new kind of cookies. He goes to the supermarket with his wife. He cannot find the ones that he saw advertised on TV. He tells his wife. ” In this situation, the student did not need to choose between options A or B but he/she was required to finish the sentence “

No tienen las galletas que…” (They do not have the cookies that …) by writing the right verbal tense, which in this case is “

busco” (I look for). In both interpretation and production exercises, participants were asked to briefly explain below in English or Spanish why they had chosen option A or B.

Appendix A contains samples of the questions in the interpretation and production sections of the pre- and post-test questionnaires.

For the class activities, the instructor presented a Power Point presentation and explained how to choose between indicative and subjunctive using

Bull’s (

1965) concept of [±EXPERIENCE].

Bull (

1965) defended the perspective of the subjunctive as a marker of meaning and used the concept of [± EXPERIENCE] in a similar way as Gili Gaya’s concept of [±REALIS]. As

Whitley (

2002) argued, “the indicative suggests that an event or entity has been experienced and found to be real, whereas the subjunctive suggests that it is unexperienced (anticipated but uncertain, yet to be encountered, unproven)” (128). MCE was implemented in the study to teach the experience/unexperienced understanding of mood in the Spanish classroom. The concept of [±EXPERIENCE] was presented in a model and, as

Negueruela and Lantolf (

2006) claimed, that model needs to be maximally informative but at the same time generalizable to different communicative contexts.

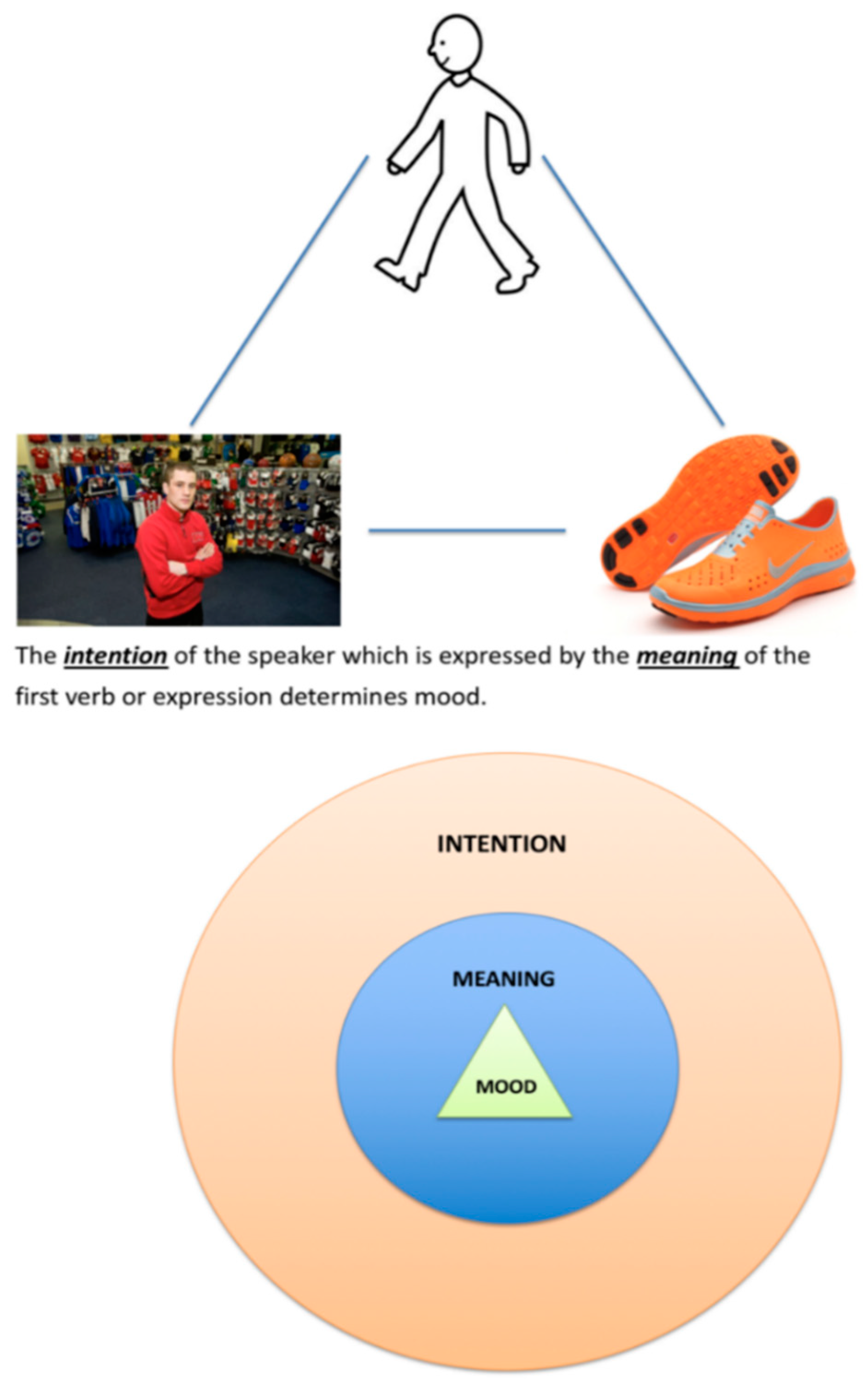

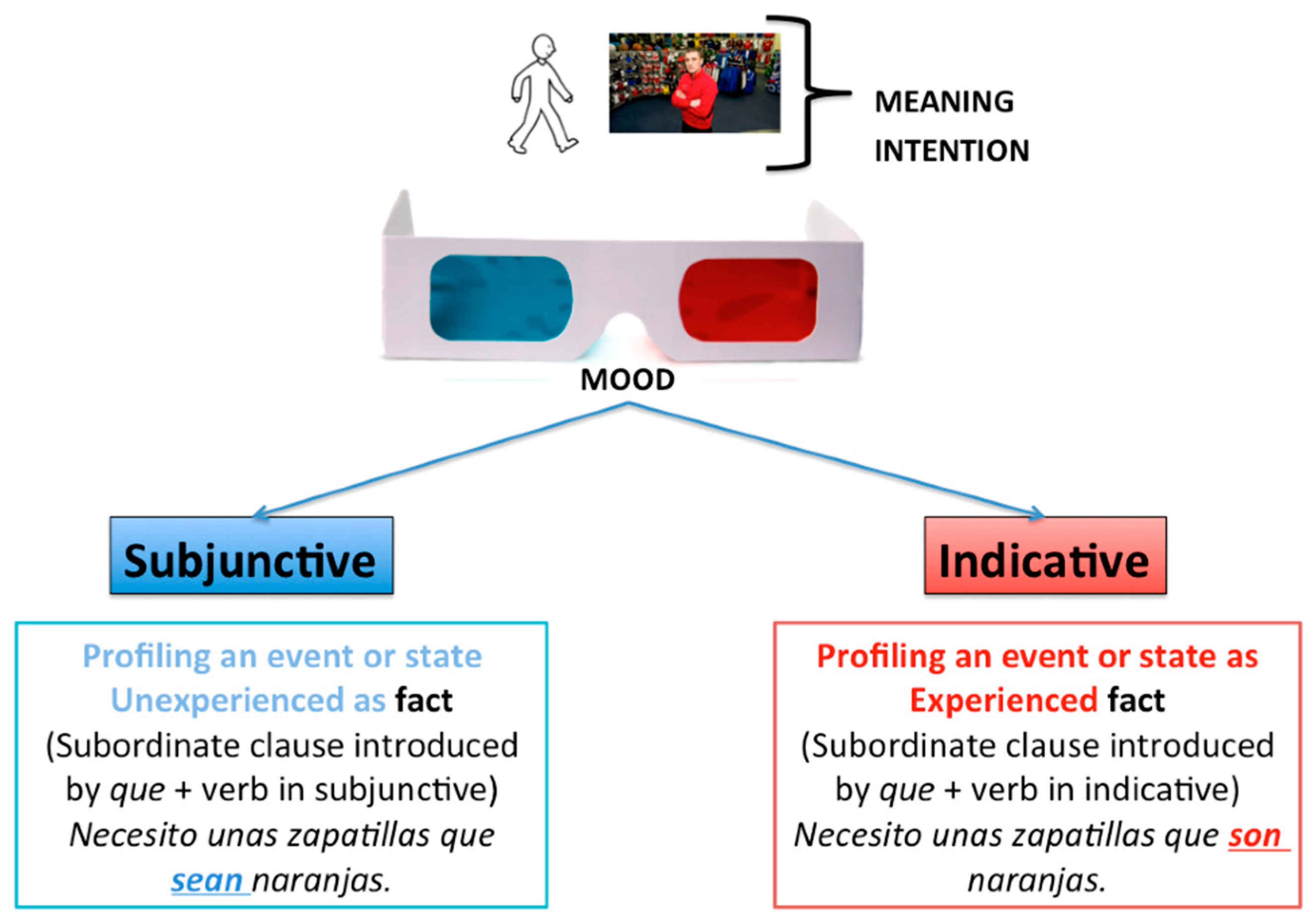

In order to materialize concepts such as intention, mood, perspective, indicative, and subjunctive, the model of the 3D glasses was chosen after a brief explanation and example. The model of the glasses was shown to students after a presentation in which they were provided the context in which Spanish native speakers would use the indicative and the subjunctive. To provide such context, the Power Point started by making them reflect on the existence of the subjunctive in English and in which cases they would use it. Then, participants were told that the intention of the speaker, which is expressed by the meaning of the first verb or expression in the matrix clause, determines mood. In order to bring these concepts to a real-life contextualized example of the use of indicative and subjunctive in adjectival clauses, students were given a presentation in which one protagonist used them in a real-life example. Such story and pictures were inspired by

Whitley and Lunn’s (

2010) “Teaching grammar with pictures. How to use Bull’s

Visual Grammar of Spanish” and it was the following: Juan runs marathons and his running shoes are worn out. He decides to go to the store to get a new pair of running shoes. He likes orange and wants the new shoes to be that color. He does not care about the brand as long as they are orange, so he goes to the running store with that idea in mind: Any kind of brand as long as they are orange. When he asks the shop assistant, he says “

¿Tienen zapatillas deportivas que sean naranjas?” (Do you have orange running shoes?) The shop assistant starts to show him orange running shoes of different prices. Once he has seen all the shoes, he goes back home and he checks online to see if the shoes he liked at the store are cheaper. However, the shoes are more expensive online so he decides to go back to the store. The way he asks the shop assistant for the shoes is different because now he says “

¿Tienen unas zapatillas que son naranjas y que cuestan 160€?” (“Do you have a pair of running shoes that are orange and cost 160€?”). The shop assistant starts showing him shoes until he brings the right ones and he finally buys them.

The slide where there is a triangle with the shoes, Juan, and the shop assistant on each side represents how meaning and intention are formed and shared thanks to these three elements of the conversation (

Figure 2). It explains how the intention of the speaker, which is expressed by the meaning of the first verb or expression, determines mood and, as a consequence, the use of indicative or subjunctive. Finally, students were presented a slide containing a model of a pair of 3D glasses. This model captures all the concepts that were presented to students in the example of the orange shoes and it is presented in

Figure 3. This model contains the concepts of mood, intention, meaning, and [±EXPERIENCE]. Students were told that, depending on the meaning and the intention of the speaker, one will be able to see through the right eye and thus choose subjunctive, or the left eye and thus choose indicative. The model of the 3D glasses is the one that students had to use as a reference in order to create their own version of the model using their own metaphor.

Once students had been shown the presentation and had been provided with the model, they were asked to produce their own version of the model and complete several homework exercises with it. In the instructions to make the model, they were asked to: (1) review the presentation slide by slide, (2) think about a personal metaphor like the one presented about the 3D glasses, (3) create the model and not forget to include the concepts of mood, intention, meaning, indicative, subjunctive, and experienced/unexperienced, and (4) record a video describing the model, explaining why the student chose that metaphor and why it was important for him/her, provide an example of a sentence that can be written with indicative and subjunctive, and explain how the model helped him/her choose the right verb.

In addition to creating the model and recording the video at home, participants were asked to complete two homework worksheets. They had to do these in written format and then they had to record a video explaining their answers and how the model helped them solve the exercises. The first worksheet had the same format as the one they did in the pre-test: interpretation and production of adjectival clauses with indicative or subjunctive in variable contexts. There were three interpretation and three production exercises. For the second homework worksheet, students were provided with six sentences of the kind “Quiero un televisor que vale poco vs. Quiero un televisor que valga poco” (“I would like a TV that does not cost too much” vs. “I would like any TV that does not cost too much”). They were asked to record a video showing how their model helped them distinguish the meaning between indicative and subjunctive in each of the sentences.

Finally, three weeks after the homework worksheets had been completed, participants were administered a feedback questionnaire together with the post-test, which had the same format as the pre-test. The feedback questionnaire had two parts. The first part contained open-ended questions so that students could provide feedback about their experience of creating and using a model to understand the concept of mood. For example, it contained questions such as, “Did you find useful the creation of a model to understand the difference between indicative and subjunctive?” or “Did the PPT presentation of the “Uses of indicative and subjunctive” help you better understand the uses of

indicativo and

subjuntivo? If so, how? Please, explain.” The second part of the feedback questionnaire contained a series of nine statements that students had to rate using two Likert scales from 1 to 5 each. One scale was for the category of difficulty and the other one was for the category of usefulness. The scales ranged from “very difficult” (5) to “very easy” (1) and from “very useful” (5) to “not useful at all” (5). The questionnaire had statements such as “Talking about abstract concepts such as mood, intention, meaning or perspective before making the model” or “Using your own model to do the homework exercises” and students had to rate them based on how useful and how difficult they regarded the statements. Questions from the two sections of the feedback questionnaire can be found in

Appendix B.

All data from the questionnaires were analyzed using SPSS version 24 with paired samples t-tests and crosstabs. In addition to this, Levene’s test of homogeneity of variance was conducted in order to assess if the samples had equal variances. When data from pre- and post-test questionnaires were entered into SPSS, 1 was assigned for correct answers and 2 for incorrect ones. For this reason, tables presenting average results of questionnaires have numbers ranging between 1 and 2. The higher and closer to 2 the score, the more incorrect the average answer is, and the lower and closer to 1, the more correct it is. For example, an average of 1.7 in the pre-test and an average of 1.3 in the post-test mean that students improve from pre- to post-test. This is due to the fact that there are more answers coded as 1 (correct) in the post-test that lower the 1.7 average from the pre-test to 1.3 in the post-test. On the other hand, if the average score of the post-test was, for example, 1.9, that would mean that more answers of the post-test were coded with a 2 (incorrect) and that the students did not improve after instruction.

4. Discussion and Pedagogical Implications

The goal of the present study was to fill an existing HL-L2 comparative research gap and expand the current knowledge to find which existing instructional approaches are suitable for both HL and L2 groups. This investigation is framed in the debate around the creation of a theory of Heritage Language Acquisition (HLA). As

Lynch (

2003) claimed, “research questions and theoretical paradigms of SLA provide a meaningful basis upon which to build in SHL” (83). The fact that the same methods were used simultaneously with HL and L2 learners and that such methods had only been previously used with L2 participants is an effort to build upon existing theories and methods from the field of SLA to enrich the area of HLA.

The results suggest that both HL and L2 students improved after MCE; however, each group improved their abilities differently. Whereas HL students significantly improved their interpretive abilities, L2 learners significantly improved their productive abilities. Differences according to group and type of task were also found by

Torres (

2018), who claimed that previous language experience was an important variable to be considered. He claimed that task complexity appeared to have an even bigger impact on HL learners compared to L2 students. Furthermore, another study that previously compared HL and L2 performance is the one by

Potowski et al. (

2009). The authors concluded that “heritage speakers’ language development may differ from that of L2 learners, although they also suggest that heritage speakers can benefit from focused grammar instruction” (565). They also found that L2 learners showed greater improvement than their HL counterparts on all tasks, and they finished the process with higher levels of grammatical accuracy. The present study demonstrated that after MCE instruction, HL participants obtained significantly higher scores on the interpretation section, whereas L2 learners reflected more significant improvement on the production section.

Potowski et al. (

2009) also observed that “heritage Spanish speakers did show modest linguistic improvement on interpretation and moderate linguistic improvement on production but no statistical improvement on the grammaticality judgment task” (561).

The fact that, in this study, MCE instruction had a statistically significant effect on the interpretive abilities of HL suggests that concept-based methods could possibly aid the HL population in overcoming the struggles they tend to have in interpretive and grammaticality judgment tasks such as those found in

Montrul (

2009),

Montrul and Perpiñán (

2011),

Correa (

2011a), or

Potowski et al. (

2009). Not only might MCE aid HL students in improving their Spanish mood interpretive abilities, but it might also be used to aid them in other conceptually demanding topics such as verbal aspect or deixis.

Zyzik (

2016) affirmed that “HL learners are at a disadvantage when exposed to materials that are intended to teach grammar to L2 learners, especially if such instruction relies heavily on students’ metalinguistic awareness” (25). This study demonstrates that by teaching grammar using MCE, it is possible to significantly improve the interpretive abilities of HL students and also counterbalance this disadvantage when facing metalinguistic knowledge.

Taking into consideration the findings from

Mikulski (

2010),

Correa (

2011a),

Torres (

2018),

Montrul (

2008), and

Lynch (

2008), pedagogically, the results of the present study show that MCE could be useful not only in L2 but also in HL classrooms. In this sense, MCE could help improve HL learner accuracy in tasks implying metalinguistic knowledge. In an article where they propose a concept-based approach to the subjunctive,

Gregory and Lunn (

2012) claim that the idea of providing students with models “is to give students the opportunity to reflect on the information value of indicative/subjunctive morphology in context while engaging them in activities with a genuine communicative purpose, thus giving them opportunities to manipulate and internalize the concept of mood contrast.” This study has shown that engaging HL and L2 students in activities in which they can manipulate and internalize the concept of mood contrast helps them improve their interpretive and productive abilities. It has also demonstrated that differences between HL and L2 students exist according to type of task. It is hypothesized that these differences could be due but not limited to factors such as previous experience with the language (formal/in class vs. informal/at home) or mode of acquisition (implicit vs. explicit). It is possible that MCE could have a more significant effect on the production abilities of learners that have had a more natural or at-home exposure to the language, whereas MCE could have a more significant effect on the interpretive abilities of those students who have had a more formal or in-class exposure to the language. Future studies should take other factors into consideration to have a better understanding of the results.

This investigation has also demonstrated that even though HL and L2 learners perceived positively MCE instruction, there were subtle differences in the “usefulness” and “difficulty” ratings for some of the claims in the feedback questionnaire. At the same time, affective, motivational, and individual differences of learners should be highly taken into consideration due to the heterogeneous backgrounds of HL students. According to

Ortega (

2013), “attitudes towards the formal learning context have been shown to exert a lasting and important influence on motivation [...] current satisfaction with teachers and instruction can boost motivation” (190). Feedback from the questionnaires after MCE showed that HL and L2 learners found the creation of their own models useful and were motivated to use them to solve the exercises and talk about abstract concepts. Future comparative studies should consider the feedback that students provide with questionnaires or interviews in order to deliver a better learning experience and adapt to students’ needs.

In order to understand better the similarities and differences between HL and L2 learners, contrastive HL-L2 research should be further developed in the future. This is not only important at class level but also at the program and syllabus level of HL courses. It has also been reported that similarities and differences exist between HL and L2 learners after MCE; however, there are some issues that should be taken into consideration in future research. Future research should also take into consideration several limitations of the present study. For example, it should increase the number of participants in order to expand the quantitative analysis. Another recommendation for studies of this type in the future would be that they not only include written feedback questionnaires, but also personal perspectives expressed during individual interviews. Allowing participants to explain to an interviewer what they liked and what they disliked about the instructional sequence would provide more opportunities for researchers to ask the participants to clarify or be more specific about certain issues that in a written questionnaire would be left unattended. Another limitation is that the pre- and post-tests were written. This is an important factor to take into consideration due to the different degrees of familiarity that HL and L2 students have with written language. The fact that HL students have had more familiarity and exposure to oral forms of communication contrasts with the situation of L2 students who have had more exposure to written modes of Spanish. Future studies could also include more HL and L2 participants of different levels than those used in this research for teaching other grammatical topics using MCE. In addition to this, having a larger sample of students would provide the opportunity for researchers to examine the influence of variables from the background questionnaire such as having studied Spanish in high school, having lived in a Spanish-speaking country, or having taken AP Spanish in high school. The fact that the researcher and the instructor were the same person could also be regarded as a limitation. In this regard, it is possible that students could have felt pressured to give more positive feedback to the lesson. Future research could be conducted by a researcher that is not the instructor of the course and who does not assign the grades. Mixed-effects models of analysis could also be used as a statistical analysis tool in the future (

Linck and Cunnings 2015) in order to analyze data from different HL and L2 groups. Future studies using this method should also include a control group. The study design would have been more robust with control groups who did not complete a MCE model, and future studies ought to include control groups in their study designs. The fact that the present study did not have one could be regarded as a limitation that future research needs to address. Additionally, future research should include more items in the assessments.

Finally, future research on MCE should also develop a sequence in which students not only develop one version of their conceptual model, but a second or third version in which they improve it based on feedback from the other students and from the instructor. It is necessary to remember that the goal of the MCE researcher is to document the changes in mediational tools and how these help students develop and internalize the concept being taught.