Abstract

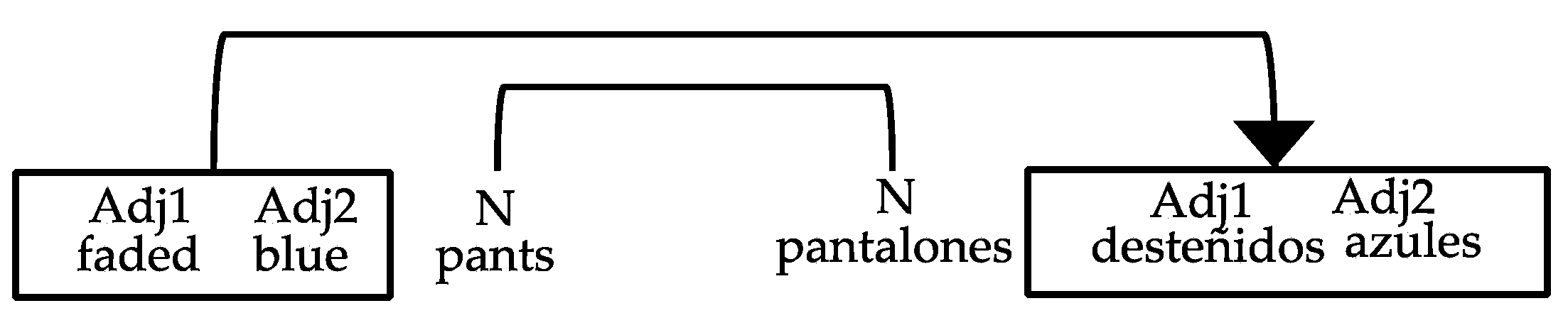

Prior studies have examined the association between modifying adjective placement and interpretation in second language (L2) Spanish. These studies show evidence of convergence with native speaker’s intuitions, which is interpreted as restructuring of the underlying grammar. Two issues deserve further study: (i) there are debates on the nature of native speaker’s interpretations; (ii) previous results could be explained by a combination of explicit instruction and access to the first language (L1). The present study re-examines native and non-native intuitions on the interpretation of variable order adjectives in pre-nominal and post-nominal positions, and extends the domain of inquiry by asking if L2 learners have intuitions about the order of two-adjective sequences, which appear in mirror image order in English and Spanish (faded blue pants vs. pantalones azules desteñidos). Two-adjective sequences are rare in the input, not typically taught explicitly, and have a different word order that cannot be [partially] derived from the L1 subgrammar. Two groups of non-native speakers (n = 50) and native speaker controls (n = 15) participated in the study. Participants completed a preference task, testing the interaction between word order and restrictive/non-restrictive interpretation, and an acceptability judgement task, testing ordering intuitions for two-adjective sequences. Results of the preference task show that the majority of speakers, both native and non-native, prefer variable adjectives in a post-nominal position independent of interpretation. Results of the acceptability judgement task indicate that both native and non-native speakers prefer mirror image order. We conclude that these results support underlying grammar reanalysis in L2 speakers and indicate that the semantic distribution of variable adjectives is not fully complementary; rather, the post-nominal position is unmarked, and generally preferred by both native and non-native speakers.

1. Introduction

To what extent are native and non-native grammars alike? Non-native learners face similar learning tasks as children: the problem of distributional learning of syntactic categories (where to place the forms) and the semantic mapping problem (what the configurations and forms mean). Adult learners must address these problems with reduced exposure, possibly past the age where their ability to make linguistic generalizations is optimal (Hudson Kam and Newport 2005; Schuler et al. 2016), while constantly referencing entrenched L1 representations. Some authors argue that adult learners sometimes fail to fully acquire novel underlying structures.

Earlier work suggests that second language (L2) speakers are limited to surface level learning. An absence of structural dependency is reported in the L2 literature on complex questions and relative clauses (Cook 2006) and scrambling (Hopp 2005). Meisel (2011) argues that L2 German speakers correctly assign verb-second V2 placement to finite verbs in matrix clauses, while using subject-verb-object SVO order in embedded clauses. Meisel (2011) interprets this performance as the result of rightward subject extraposition as opposed to target subject-object-verb (SOV) order with verb raising. He also notes that post-verbal nicht “no” is acquired prior to verbal inflection in L2 German, interpreting this as additional evidence for surface-level word order learning. Further evidence for structural insensitivity to negation comes from English-speaking learners of Spanish who allow the complex predicate formation that licenses clitic climbing over sentence negation (Thomas 2011).

One response to these claims is to point to other sources of difficulty beyond syntactic structures. Difficulty with tense and agreement may reflect difficulties at morphological insertion (Prévost and White 2000; Slabakova 2016); interacting domains may tax processing resources (Sorace 2011); and, an absence of clitic climbing may be prosodic, not syntactic (de Garavito 2019). Psycholinguistic work with L2 populations focuses not on representations, but on parsing, proposing that non-native speakers tend to perform surface (shallow) parsing of complex structures (Clahsen and Felser 2006, 2018). Sagarra et al. (2019) find effects of shallow parsing on semantic interpretation; non-native Spanish speakers interpret object-verb-subject (OVS) relative clauses as SVO and have more difficulty recovering from this analysis.

The last two decades of work have placed intense focus on the challenge of acquiring semantic properties in a second language (Slabakova and Montrul 2003; Slabakova 2006; Guijarro-Fuentes 2012; Cho and Slabakova 2014; Sánchez Alvarado 2018; Hopp et al. 2020; to name a few) and semantic learning is often used to assess claims of L2 syntax. We propose that adjective placement in Romance languages offers an important test of whether learners can acquire novel underlying structure. This domain involves learning the interface between a distributional problem (the variable placement of adjectives in Romance) and a mapping problem (how adjective scope is mapped onto word order).

In languages such as Spanish, adjective position is crucially linked to lexical class. Some adjectives are lexically restricted to either pre- or post-nominal positions (1–2). Others may appear in either position with a lexical change in meaning (3) or under certain discourse conditions (4).

1 El libro azul the book blue “the blue book” 2 El próximo presidente the next president “the next president” 3a El mal cocinero (bad as a chef) the bad chef 3b El cocinero malo (a chef who may be bad in some other respect) the chef bad “the bad chef” 4a El peligroso delincuente (one criminal in the context) the dangerous criminal 4b El delincuente peligroso (one criminal among others) the criminal dangerous “the dangerous criminal”

Word order is associated with interpretation. Adjectives can modify the whole noun (i.e., intersective) or a subpart of the noun (i.e., non-intersective), as illustrated in (3). The pre-nominal adjective in (3a) only has a non-intersective interpretation, where the chef is bad in his role as a chef (i.e., he does not cook well). The post nominal adjective in (3b) has an intersective reading; it identifies someone who is both a chef and bad as a person. Adjective interpretation can also be contingent on the presence or absence of a contrast set, as illustrated by (4) (i.e., restrictive (R)/non-restrictive (NR)). Absent semantic/prosodic focus (see Demonte 2008), (4a) only has a NR reading where there is one criminal in the context and that criminal is dangerous, whereas (4b) has a R reading (i.e., a context with multiple criminals, only one of which is dangerous).

Before we consider whether L2 speakers are able to learn the association between form and position, we should highlight that there is a division among syntacticians as to the interpretation of the post-nominal position. Complementary approaches assumes that the post-nominal position is unambiguously intersective and restrictive (Alexiadou 2001; Bernstein 1993; Demonte 2008; Ticio 2010). Under this approach, ambiguity is only apparent: once context, lexical meaning, and/or the possibility of contrastive stress are accounted for, pre-nominal adjectives have exclusively non-intersective and non-restrictive interpretations, whereas post-nominal adjectives are unambiguously intersective and restrictive. For example, el cocinero malo “the bad chef” has a non-intersective interpretation post-nominally, not because the post-nominal position is ambiguous, but because we generally refer to chefs in their roles as chefs. In contrast, post-nominal ambiguity approaches allow for both interpretations post-nominally (i.e., non-intersective/intersective, non-restrictive/restrictive) (Cinque 2010; Fábregas 2017; Martín 2009), while attributing a special, marked status to the pre-nominal position. A syntax void of post-nominal ambiguity could not, for example, account for the possibility that all Elena’s classes are boring in las clases aburridas de Elena “Elena’s boring classes” (Fábregas 2017, p. 28).

Adjectival order and interpretation is not a phenomenon particularly vulnerable to bilingual transfer. Camacho (2018) found that heritage Spanish speakers evidenced the same ordering restrictions as baseline speakers; they rated post-nominal adjectives higher than pre-nominal adjectives in restrictive contexts. This was true of color and nationality adjectives, which are lexically restricted to post-nominal position, and adjectives that could, in principle, appear in either position. Nonetheless, for adult learners whose native language has a fixed pre-nominal position, post-nominal adjectives may offer evidence of having learned novel underlying structure, on the common premise that post-nominal adjectives in Romance result from raising of the noun to intermediate functional projections, leaving adjectives behind (Gess and Herschensohn 2001; de Garavito and White 2002). A number of L2 studies have found L2 learners possess knowledge of the placement and relative meaning of adjectives in French and Spanish. Anderson (2001, 2008) found English-speaking advanced L2 learners of French assigned target lexical meanings according to position. They interpreted pre-nominal adjectives as non-intersective and post-nominal adjectives as intersective (e.g., simple robe/robe simple “mere dress/plain dress”). Intermediate speakers had only learned post-nominal intersective adjective meanings. Although Anderson (2001, 2008) concluded that implicit structural knowledge had taken place, inductive learning combined with instruction is also a plausible explanation for these results. Anderson (2007a) found that English-speaking intermediate and advanced L2 learners of French differed from native speaker controls when tested on the interaction between word order and NR/R interpretation. Native speakers accepted pre-nominal adjectives well above chance in NR contexts, while L2 speakers preferred post-nominal adjectives. This is an expected result if they have internalized the pedagogical rule (Anderson 2007b). Nonetheless, Anderson (2007a) argues against fundamental differences between native and L2 speakers because both had significantly lower rates of acceptance of pre-nominal adjectives in R contexts. However, methodological issues limit interpretability of the results: relevant trials were not minimal pairs; the uniqueness presupposition of the definite article was not met in the R context, which may have led to lower ratings across speaker groups.

A subsequent study examined L1-French L2-Spanish acquisition, a language pair with both substantial overlap and interlanguage differences. Overall, pre-nominal adjectives are less frequent in Spanish than in French (Scarano 2005; Rizzi et al. 2013), but certain lexical classes actually allow for more pre-nominal adjectives (Androutsopoulou et al. 2008), including adjectives that express a speakers’ evaluation (e.g., una fantástica película/ *un fantastique film “a fantastic film”) and ordinals (la siguiente pregunta/ *la suivante question “the next question”). Androutsopoulou et al. (2008) found that French-speaking intermediate and advanced learners judged Spanish pre-nominal evaluative adjectives that were grammatical in French as significantly better than those where the two languages differed. There were less transfer effects for ordinals. Based on the high degree of variability in L2 judgements, Androutsopoulou et al. (2008) conclude that acquisition proceeds on an item-by-item basis, and is initially influenced by the L1.

Other studies have found that advanced learners of Spanish interpret and produce pre-nominal and post-nominal adjectives with near-native proficiency (Judy et al. 2008; Guijarro-Fuentes et al. 2009; Rothman et al. 2009, 2010). These studies used various combinations of the following tasks: grammaticality judgement combined with correction tasks (GJCT); context-based collocation tasks (CBCT), where participants read a short context and then fill in the adjective provided in pre- and/or post-nominal position; and preferred gloss tasks (PGT), where participants read sentences containing a pre- or post-nominal adjective and choose between two potential glosses provided. These studies found attainment across the various language pairings, at least for the CBCT and the PGT. Judy et al. (2008) found advanced English-speaking learners of Spanish to be native-like in the CBCT, but unable to reject lexically pre-nominal adjectives (2) in post-nominal position in the GJCT. Guijarro-Fuentes et al. (2009) found similar results for Italian and English-speaking learners of Spanish in the CBCT and PGT, with L1 Italian speakers converging on the target grammar earlier. Rothman et al. (2009) compared performance of a group of Germanic (English, German) speaking and Italian-speaking intermediate and advanced learners of Spanish; neither the advanced Germanic group nor the intermediate and advanced Italian groups differed from native speaker controls on any of the tasks. Lastly, Rothman et al. (2010) report L2 convergence for the CBCT and PGT for a population of exclusively English-speaking learners of Spanish and a correlation between these tasks and GJCT performance. Taken together, these studies show success in adult learning of adjective distribution. However, a number of issues with these studies leave the question of interpretation open.

The first issue is that these studies assume a complementary approach even when the intuitions of their native speaker controls contradict this analysis. Native speakers placed adjectives significantly less pre-nominally in NR contexts than predicted by a complementary approach in the CBCT data reported in Judy et al. (2008), Rothman et al. (2009) and Guijarro-Fuentes et al. (2009). In Rothman et al. (2010) the data appears complementary, as native speakers overwhelmingly interpreted pre-nominal adjectives as NR and post-nominal adjectives as R. One concern is the absence of minimal pairs. Rothman et al. (2010) selected 20 lexical items for the two experiments, but used each adjective only once per task. So, for example, estudioso “studious” was used pre- but not post-nominally in the PGT, whereas in the CBCT it was provided in a R, but not a NR context. Given the primacy of the lexical factor in this domain, this is problematic. The pre-nominal use of an adjective like estudioso “studious” regardless of context is quite marked in comparison to an adjective such as valiente “brave”. The acceptability of individual lexical items in pre-nominal position is affected by syllabic weight (adjectives shorter than the nouns they modify are more felicitous in pre-nominal position) and register (written register facilitates pre-nominal use; File-Muriel 2006; Centeno-Pulido 2012; Hoff 2014). These factors may have combined to support complementary performance. For example, a participant who assigned a NR reading to los estudiosos estudiantes “the studious students” in the PGT, might have dispreferred the pre-nominal position in the CBCT regardless of interpretation.

These studies also claim there is an absence of explicit instruction. This assumption is somewhat problematic, because the relationship between adjective position and restrictivity is the target of explicit instruction in various standard textbooks (see King and Suñer 2008, p. 158; Salazar et al. 2013, p. 294; Zayas-Bazán et al. 2014, p. 17; Bleichmar and Cañón 2016, p. 16). A complementary approach is presupposed by most pedagogical treatments; intermediate and advanced Spanish textbooks standardly describe the subclass of adjectives that can be pre- or post-nominal in terms of known quality vs. contrast:

This kind of instructional material may be the source of L2 speakers’ categorical judgements.“When placed after a noun, adjectives serve to differentiate that particular noun. Adjectives can be placed before a noun to emphasize or intensify a particular characteristic, to suggest that it is inherent or to create a stylistic effect or tone. In some cases, placing an adjective before the noun indicates a value judgement on behalf of the speaker (Bleichmar and Cañón 2016, p. 16).”

Furthermore, the role of the English L1 merits additional consideration. Grammars contain rules that allow for the existence of sub-regularities or idiosyncratic constructions that are lexically triggered (i.e., subgrammars) (Amaral and Roeper 2014). For example, English participial adjectives and adjectives formed with the modal suffix –able/-ible can appear in both pre- and post-nominal positions, and this alternation also maps into the R–NR contrast (see Bolinger 1967; Larson and Marusic 2004; Cinque 2010, 2014) (5–8).

- 5.

- Every blessed person was healed

5a “Every person was healed; they were blessed” (NR) 5b “Every person that was blessed was healed” (R) - 6.

- Every person blessed was healed

6a #“Every person was healed; they were blessed” (NR) 6b “Every person that was blessed was healed” (R) - 7.

- Every unsuitable word was deleted

7a “Every word was deleted; they were unsuitable” (NR) 7b “Every word that was unsuitable was deleted” (R) - 8.

- Every word unsuitable was deleted

8a #“Every word was deleted; they were unsuitable” (NR) 8b “Every word that was unsuitable was deleted” (R)

Pre-nominal adjectives (5,7) are ambiguous between a NR reading (where the adjective applies to all the nouns in a given context) and a R reading (where it applies to only some of the nouns, i.e., the contrast set). The post-nominal adjective (6,8) on the other hand may only be interpreted restrictively. This is exactly what Rothman et al. (2010) find for some intermediate speakers in the PGT. The target-deviant group performed significantly worse when asked to provide preferred glosses for pre-nominal vs. post-nominal adjectives. Rothman et al. (2010) attributes this performance to the effect of repeated instruction presenting the post-nominal position as the default in Spanish. However, reliance on the L1 subgrammar can predict precisely these results.

The relationship between word order and restrictivity complementary approaches assume can be at least partially derived from the English subgrammar. To arrive at post-nominal ambiguity a learner referencing the English subgrammar only has to (1) recognize the parallels between the pre-nominal in English and post-nominal in Spanish, and (2) identify the pre-nominal as expressing subjective speaker judgements in Spanish. As soon as the subjective use of the pre-nominal is identified, non-restrictivity comes for free; cross-linguistically subjective adjectives are not used restrictively (see Martin 2014; Umbach 2006, 2016). The first acquisition step is straightforward considering (a) the cumulative effect of explicit instruction of the post-nominal (i.e., more classes of adjectives are either optionally obligatorily post-nominal than pre-nominal), as suggested by Rothman, and (b) the free use of lexically post-nominal adjectives with restrictive and non-restrictive interpretations (e.g., el cometa azul ‘the blue kite’). The second step is supported by pedagogical treatments of the Spanish pre-nominal as subjective (see Bleichmar and Cañón 2016; Finnemann and Carbón 2001). All of these factors can support learners’ mapping of the restrictivity contrast in Spanish, without appealing to underlying restructuring of the grammar. If this reasoning is correct, additional experimental evidence is needed. We propose that evidence on single adjective position be augmented with evidence on what learners know about the position of adjectives in two-adjective sequences.

Our approach is as follows: we first ask whether native speakers of Spanish show patterns of interpretation along the lines of the complementary approach or the post-nominal ambiguity approach. We then compare them to non-native speakers, arguing that the complementary pattern is compatible with an effect of explicit instruction. After categorizing native and non-native Spanish grammars with respect to single adjective placement, we evaluate non-native Spanish speakers’ capacity for structure building by examining how they perform with two-adjective sequences. These contexts can provide key information on how learners map the hierarchical structure of the Spanish noun phrase. To show how, we first need to explain how the pre-nominal position in Spanish relates to the orders observed in adjectival sequences.

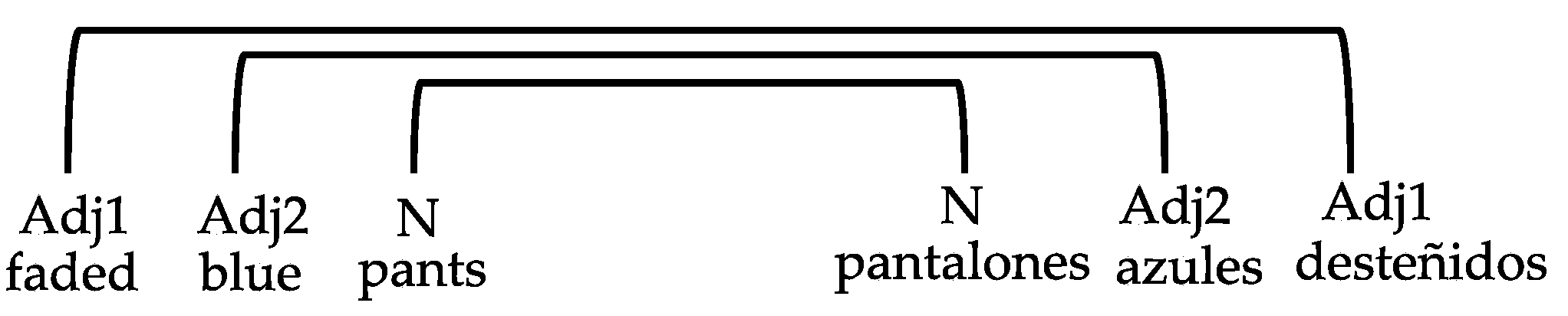

In Spanish, like in other languages, adjective sequences obey ordering restrictions (AORs), which have been described in various ways in the literature. The unified base hypothesis (Cinque 2010) holds that across languages, adjectives are ordered according to the same hierarchical structure, with certain classes of adjectives merged closer to the noun. According to this view, direct modifier adjectives—adjectives that directly attribute a characteristic to the noun—are strictly ordered amongst themselves via a notionally based hierarchy, where nationality adjectives appear closest to the noun followed by color, then shape, then size and, finally, value adjectives (for similar typologies see Tribushinina et al. 2014 and references therein). This proposal accounts for the seeming mirror image distribution of adjectives across languages (cf. English faded blue pants and Spanish pantalones azules desteñidos, where, in both cases, the size adjective is always closest to the noun).

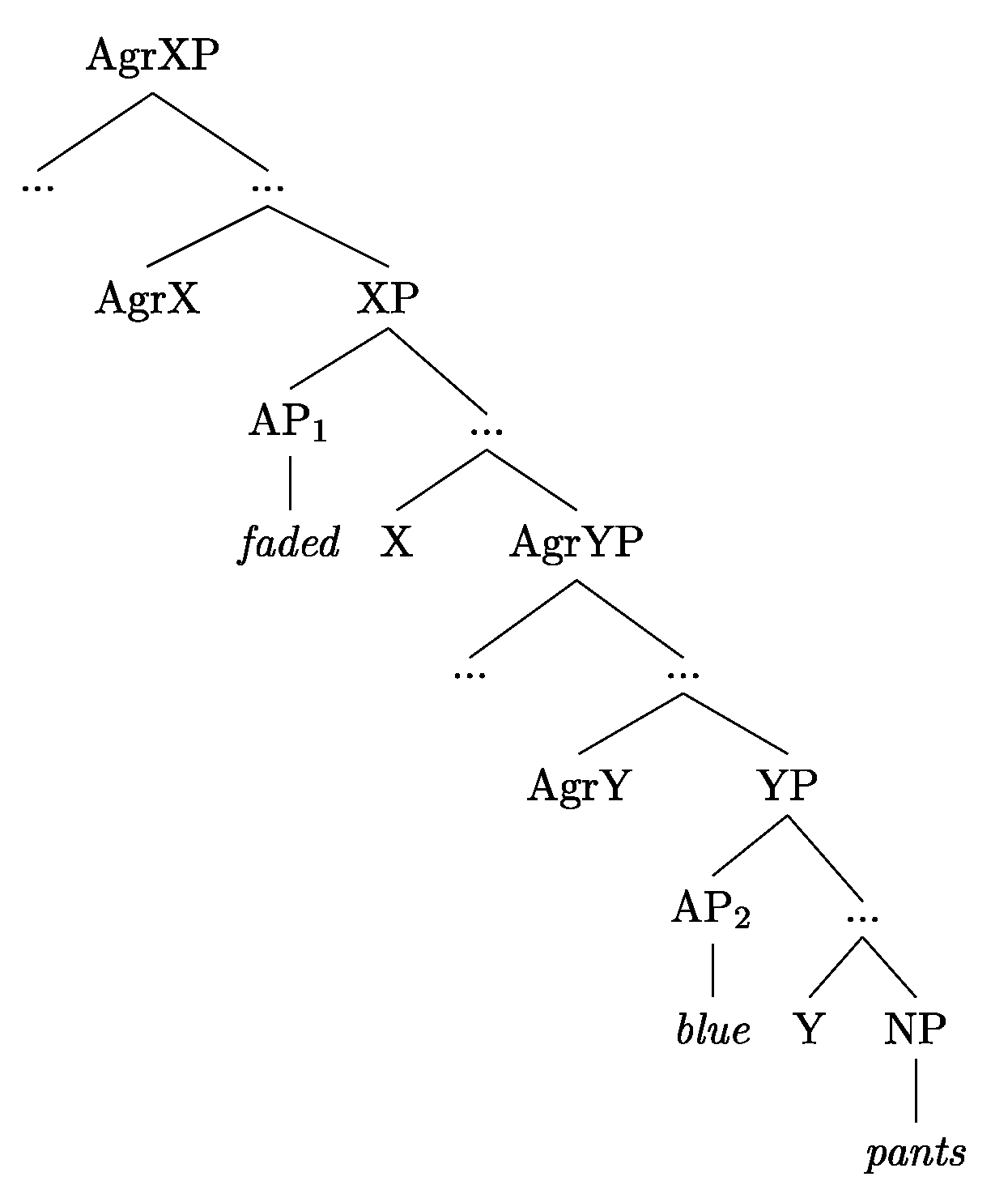

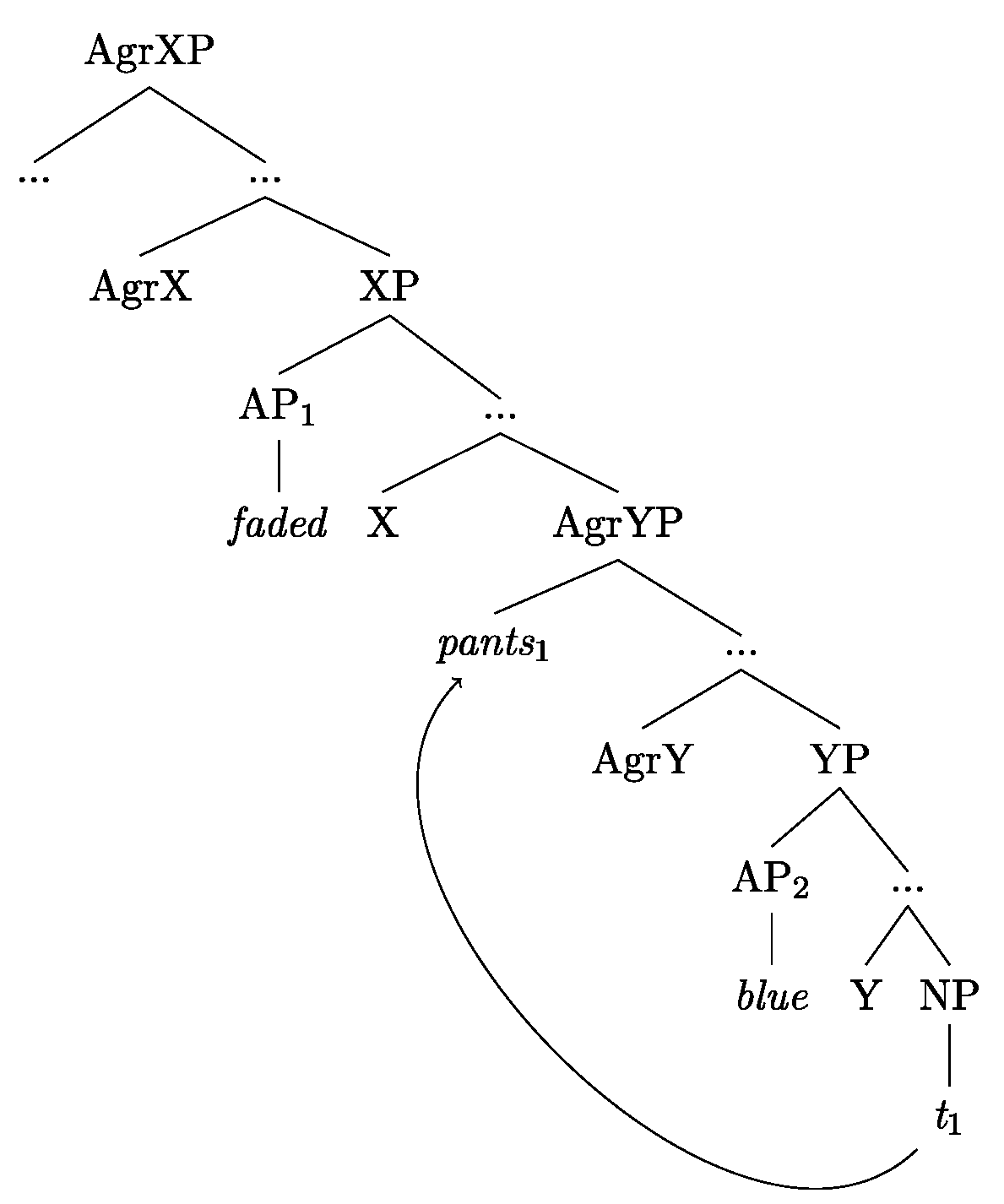

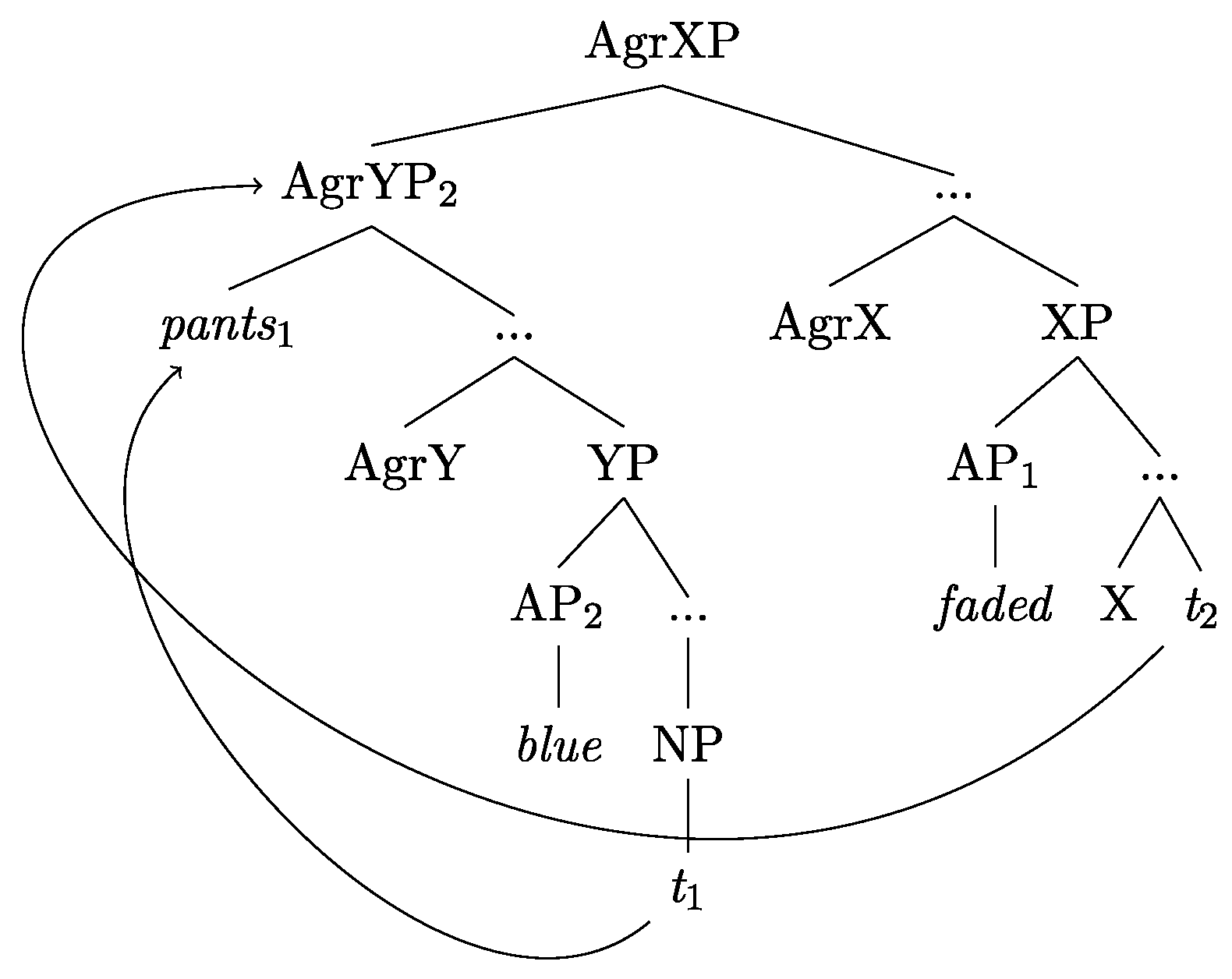

Cinque (2010) derives the Spanish order from an English linear base order via (9a) cyclic movement, where the noun moves and left adjoins to the closest adjective, i.e., blue (9b), and in a subsequent movement the noun (N) – adjective (Adj) sequence (i.e., N + Adj2) rolls up and left adjoins to the furthest adjective from the noun, i.e., faded (9c).

- 9.

- English Order: Adj1 Adj2 N “faded blue pants”

- Interpolated Sequence: Adj1 N Adj2 desteñidos pantalones azules “faded pants blue”

- Spanish Mirror Image Order: N Adj2 Adj1 pantalones desteñidos azules “pants blue faded”

AORs can be broken if one or both adjectives is an indirect modifier. These are adjectives whose modification relationship to the noun is mediated by an intervening (reduced) relative clause. They are further from the noun than direct modification adjectives, but freely ordered amongst themselves (see Sproat and Shih 1991 for a detailed account of the indirect-direct modifier distinction) (10).

- 10.

10 pantalones desteñidosdirect/indirect azulesindirect pants faded blue

Despite the possibility of alternative, marked orders, such as in (10), Spanish is supposed to adhere to AORs both within and across lexical semantic classes (i.e., N > intersective {nationality > color > shape} > non-intersective {size > value}). The picture is however, more complex. Counterarguments include the reduced number of possible pre-nominal adjectives in Spanish and the relative freedom of adjective order, both pre-nominal and post-nominal (Sánchez 1996, 2018; Demonte 1999a, 1999b). The intersective > non-intersective hypothesis claims that adjectives interpreted intersectively (e.g., color and shape) are closer to the noun than: (a) those with non-intersective interpretations (e.g., value) and (b) those whose interpretation is context dependent (e.g., size) (see Kamp and Partee 1995) (Demonte 1999a, 1999b). This hypothesis makes the same macro-level distinction that the unified base hypothesis does for direct modifiers (i.e., N > intersective > non-intersective), but predicts optionality at the micro-level (i.e., N > nationality/color/shape > size/value). For example, un niño pequeño lindo “a boy small sweet” and un niño lindo pequeño “a boy sweet small” should be equally possible. Finally, the free ordering hypothesis suggests that adjective ordering is (at least partially) free of lexical-semantic restrictions (Sánchez 2018). Adjectives of at least color, shape, and nationality are shown to be freely ordered in a manner comparable to indirect modifiers in the unified base hypothesis.

There is not much empirical work on adjective sequences. A recent corpus study by Pérez Leroux et al. (2020) suggest that some degree of ordering restrictions appear if one considers interpolated adjective–noun–adjective (Adj–N–Adj) sequences. These authors extracted post-nominal sequences of adjectives (N–Adj–Adj) and interpolated Adj–N–Adj sequences from the Google Ngram Corpus and the Corpus del Español, arguing that interpolated sequences can be used to enrich the data on AORs in Spanish. The unified base hypothesis analyzes the pre-nominal adjective in interpolated sequences, which is further from the nominal head in terms of scope, as corresponding to the second adjective in post-nominal sequences (9b,c). Their data show an ordering asymmetry between relational adjectives—denominal adjectives that attribute to the noun they modify a relationship with a class described by their nominal root (un mandato parlamentario “a parliamentary mandate” is a mandate by/for parliament) and qualifying adjectives—adjectives that denote qualities or properties of entities (el carro azul “the blue car”, la manzana podrida “the rotten apple”) (see Demonte 1999a; McNally 2016). Relational adjectives were hierarchically closer, relative to qualifying adjectives, and other classes. Value adjectives, a subset of qualifying adjectives appeared further from the noun than qualifying color adjectives (hermoso color negro “beautiful color black”), and other types. While the data was too sparse to assess key combinations (such as value and size) (9), it was sufficient to clearly support the intersective > non-intersective hypothesis.

Under the assumption that Spanish interpolated Adj–N–Adj sequences are derived via movement of the N past direct modification adjectives (whose order is at least color/shape>size/value), and that two post-nominal adjectives are derived by an additional application of roll-up movement, the evidence supports that (at least) the macro structure for direct modifiers is the result of a unified base. Despite the flexibility in adjective ordering, native Spanish speakers are likely to judge the mirror pattern (11a) as the acceptable, unmarked option, and should prefer it to the order shown in (11b), which is the marked order. Note that this order is surface-equivalent to a post-nominal version of the English linear pattern.

- 11.

- Mirror pattern

- English linear pattern

Now, for non-native learners, the question is, do they pattern similarly? If we assume that when they learn that Spanish adjectives are post-nominal, they also employ a cyclic derivation to derive such post-nominal orders, we predict that they too should prefer the mirror pattern to the English linear pattern. As the structure in English corresponds to the base structure before roll-up movement, English-speaking learners of Spanish would have to access this structural operation in order to converge on the target grammar (11a). Alternatively, if learners are limited to surface level learning, they should prefer the English linear pattern (11b).

Importantly, if we find convergence for two-adjective sequences, explicit learning cannot explain why learners have acquired it.1 Two-adjective sequences are fairly rare, and most of the two-adjective sequences attested in the corpus study discussed above were sequences of relational adjectives, the most frequent category. Most of the remainder involved at least one relational adjective. Only interpolated sequences offer evidence of other combinations. For this input to be informative, learners would need to recognize these alternative sequences as arising from a roll-up derivation. Because adjective sequences are both infrequent and nearly absent in explicit instruction, we hypothesize that sensitivity to word order is indicative of learner’s underlying syntactic derivations. Conversely, lack of sensitivity suggests a lack of underlying structural reanalysis.

The present study has two overarching goals. The first goal is to evaluate whether native and non-native speakers evidence complementarity or post-nominal ambiguity when the noun is modified by a single adjective. The second is to evaluate whether L2 speaker’s post-nominal adjectives result from underlying structural reanalysis. Given the limited use of pre-nominal adjectives in Spanish (Scarano 2005; Rizzi et al. 2013; Pettibone 2021), we hypothesize that native speaker results will support post-nominal ambiguity, but we remain neutral as to whether learners evidence complementarity as predicted by explicit instruction or post-nominal ambiguity. To evaluate Spanish learner’s structure-building abilities we turn to comparing two-adjective sequences in learners and native speakers. Our research questions are:

Question 1: Single adjective modification in context

- (a)

- Do native Spanish-speaker intuitions point to complementarity or post-nominal ambiguity?

- (b)

- Are Spanish learners sensitive to the interactions between position and interpretation? If so, do their intuitions align with complementarity or post-nominal ambiguity?

Question 2: Two-adjective sequences and structural reanalysis

- (a)

- Do native Spanish speakers judge the mirror pattern as more acceptable than the English linear pattern?

- (b)

- Do Spanish learners show sensitivity to lexical classes and their preferred placement?; and

- (c)

- Do Spanish learners have intuitions about preferred orderings of two-adjective sequences? If so, do they favor the mirror image pattern, or do they prefer English-linear sequences as predicted by surface level learning accounts?

To answer the first set of questions, we designed a preference task inviting speakers to choose between pre-nominal and post-nominal adjectives in restrictive and non-restrictive contexts. To address the second set of questions, we developed an acceptability judgement task to probe which adjective orders were rated as more acceptable.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants completed two tasks run using SuperLab© software. A Preference Task (PT) (Appendix A) modeled on previous work by Rothman et al. (2010), asked participants to choose between minimal pairs of sentences (8 items total, 4 per context) that differed as to the position of the adjective with respect to the noun (i.e., pre- or post-nominal) given a NR (12) or R context (13). For all tasks, a short context was presented on an initial screen. Participants pressed a button on the keypad to continue to the test item. For the PT, a colored button appeared next to each sentence that corresponded to a button on the keypad. For the Acceptability Judgement Task (AJT), an illustration of the keypad along with its corresponding scale (in words) appeared concurrently with the target sentence to be judged.

- 12.

- No hay torero que no sea conocido por su coraje; es decir ser torero es enfrentar peligro a diario. “There is not a bullfighter who is not known for their courage, it is to say that to be a bullfighter is to face danger every day.”

| 12a | Los | valientes | toreros | no | tienen | miedo | de |

| the | brave | bullfighters | NEG | have | fear | of | |

| arriesgar | la | vida | |||||

| risk-INF | the | life | |||||

| 12b | Los | toreros | valientes | no | tienen | miedo | de |

| the | bullfighters | brave | NEG | have | fear | of | |

| arriesgar | la | vida | |||||

| risk-INF | the | life | |||||

| “The brave bullfighters are not afraid to risk their lives” | |||||||

- 13.

- Algunos soldados son valientes; otros son cobardes. “Some soldiers are brave and others are cowards”

| 13a | #Los | valientes | soldados | arriesgan | la | vida |

| the | brave | soldiers | risk | the | life | |

| con | frecuencia | |||||

| with | frequency | |||||

| 13b | Los | soldados | valientes | arriesgan | la | vida |

| the | soldiers | brave | risk | the | life | |

| con | frecuencia | |||||

| with | frequency | |||||

| “The brave soldiers risk their lives frequently” | ||||||

Prior to the PT, participants saw three training items–two where they had to choose between grammatical and ungrammatical sentences with either ser and estar “to be”, and one that manipulated the subjunctive/indicative mood following no es una sorpresa que “it is not a surprise that”. The PT contained eight fillers where participants had to choose between two sentences containing either a noun modified by a bare prepositional phrase (PP) or a relative clause (RC). The following adjectives appeared in the experimental items: poderosos “powerful”, altos “tall”, bellas “beautiful”, valientes “brave”, inteligentes “intelligent”, fuertes “strong”, rápidos “fast”, saludables “healthy”, corresponding to the following notionally based semantic classes: behavioral property (poderosos “powerful”, fuertes “strong”), size (altos “tall”), value (bellas “beautiful”, saludables “healthy”), internal state (valientes “brave”, inteligentes “intelligent”) and physical property (rápidos “fast”). As a group, these adjectives are uniformly non-intersective and qualifying. Additionally, all adjectives were of equal or lesser syllabic weight than the nouns they modified with the exception of inteligentes “intelligent” and saludables “healthy”, However, these two exceptions can be used evaluatively (despite only saludables “healthy” having the lexical classification of value), increasing their acceptability in pre-nominal position.

In addition, participants completed an Acceptability Judgement Task (AJT) (Appendix B) where, after reading a short context, they were asked to provide scalar judgements (i.e., completely unacceptable, a bit odd, almost fine, completely acceptable) of sentences that manipulated the placement of single, obligatorily post-nominal relational adjectives (14) (8 items total, 4 per order), or of multiple adjectives (15) (8 items total, 4 per order):

- 14.

14a El contrato legal the contract legal 14b *El legal contrato the legal contract “the legal contract” - 15.

15a Mirror pattern Las cortinas amarillas horribles the curtains yellow horrible 15b English linear pattern Las cortinas horribles amarillas the curtains horrible yellow “the horrible yellow curtains”

Prior to the AJT participants saw three training items consisting of a short context followed by a sentence that either followed naturally from the context (n = 1) or did not (n = 2). Fillers in the AJT (n = 15) manipulated the inalienability of a noun and a PP modifier headed by con “with” or sin “without” (n = 8); and the acceptability of lexical PP modifiers to establish a locative relationship between two nouns (n = 7). Multiple adjective items consisted of adjective pairs that included one relational and one qualifying adjective (n = 4) or two qualifying post-nominal adjectives (n = 4) presented in mirror image or English linear pattern. For single adjectives, the following lexical items appeared in the AJT: legal “legal”, política “political”, mensual “monthly”, industrial “industrial”, metálica “metallic”, solar “solar”, plástico “plastic”, and personal “personal”. Two-qualifying- adjective sequences corresponded to color > extreme degree (cortinas amarillas horribles “horrible yellow curtains”), color > physical property (saco negro desteñido “faded black sweatshirt”), shape > value (mesa redonda cara “expensive round table”), and color > physical property (melón verde podrido “rotten green melon”). Two – relational and qualifying – adjective sequences corresponded to relational > size (el puerto marítimo grande “the big maritime port”), relational > value (un manual escolar confuso “a confusing school manual”), relational > manner (el paseo campestre largo “the long country outing”), and relational > size (una vaca lechera grande “a big milking cow”).2

3. Participants

Participants in the study were a native Spanish speaker control group (henceforth Native) (n = 15) from Cali, Colombia and two Spanish learner groups: L1 English learners of Spanish (n = 33) and a second group (n = 17) combining native speakers of an L1 other than English (n = 5), simultaneous bilinguals speakers of English and other language (n = 4) and those who reported languages other than English spoken in the home (n = 8) (i.e., Multilingual learners of Spanish, henceforth Multilingual). We removed from analysis the data of two native speakers who did not attend to the position of single ungrammatical pre-nominal relational adjectives in the testing materials. Two L2 speakers (one L1 English, one Multilingual) only completed the AJT. Table 1 provides a summary of participants by tasks.

Table 1.

L1 and L2 Participants in the Preference Task (PT) and Acceptability Judgement Task (AJT).

All learners of Spanish completed the cloze test included in Montrul’s (2004) adapted version of the Diplomas of Spanish as a Foreign Language (DELE) as a measure of L2 proficiency and a language history questionnaire, results of which are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3 for the PT and AJT, respectively. The cloze test had participants choose from three multiple choice answers to complete a written passage with 20 missing words (max score: 20 points). The Language History Questionnaire had participants evaluate their level of English and Spanish on a scale of 1 (basic/limited) to 4 (excellent/near native) for reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Dominance scores were calculated as the difference between the sum of these scores for English and Spanish (sum of English – sum of Spanish); positive scores reflect English dominance, whereas negative scores reflect Spanish dominance. Participants also rated their exposure to Spanish compared to English on a scale of −3 (only English) to +3 (only Spanish).

Table 2.

Learner cloze test, language dominance, and language contact scores for PT.

Table 3.

Learner cloze test, language dominance, and language contact scores for the AJT.

We used independent two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction to compare the groups. For the PT, there were no significant between group differences in performance on the cloze test (t(32.27) = −1.12, p = 0.27), or with respect to the dominance score (t(41.55) = 0.56, p = 0.58). However, average language contact score differed significantly for the two groups (t(43.99) = −3.52, p = 0.001). Similarly, for the AJT, there were no significant between group differences in performance on the cloze test (t(35.45) = −1.04, p = 0.30), or with respect to the dominance score (t(43.611) = 0.63, p = 0.53), but average language contact score differed significantly for the two groups (t(47.14) = −3.29, p = 0.002).

4. Results

4.1. Preference Task

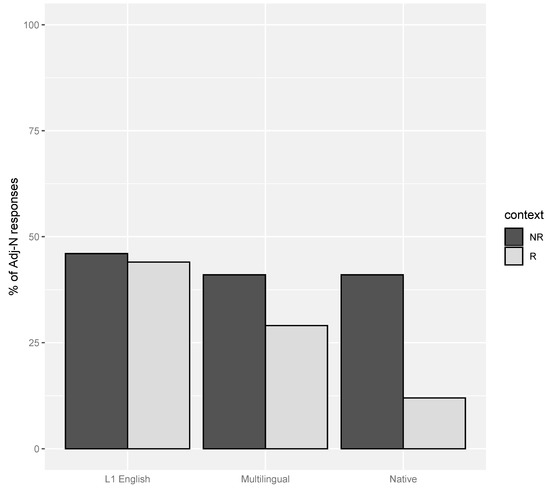

We analyzed the differences in the distribution of pre- and post-nominal responses among speaker groups (L1 English, Multilingual, Native), across conditions (R, NR) (Figure 1). To compare overall frequencies of pre-nominal adjectives in L1 English, Multilingual, and Native Spanish speakers, we fitted a generalized linear-mixed effect model by the maximum likelihood method in R (Laplace Approximation), using the binomial distribution, with native speaker group as the reference level. The model included participants and items as random effects and the interaction of the fixed effects language group and context (Table 4). The fit of this model was significantly better than a model with no interaction between the fixed effects language group and context (Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) = 509.2 vs. 517.1), χ2(2) = 11.9, p < 0.01.

Figure 1.

Percentage of adjective–noun (Adj–N) response given for NR and R contexts by speaker group (L1 English, Multilingual, Native).

Table 4.

Generalized linear model testing the effect of language group by context on the preference for Adj–N responses (formula: Adj–N ~ Group × Context + (1|Participant) + (1|Item)).

The model indicated a significant effect of context, as R context significantly decreases the odds of choosing pre-nominal adjectives, but as shown by the significant interactions, this is driven by Spanish native speakers. The odds of choosing pre-nominal adjectives in R contexts significantly increases for both L1 English and Multilingual learners of Spanish.

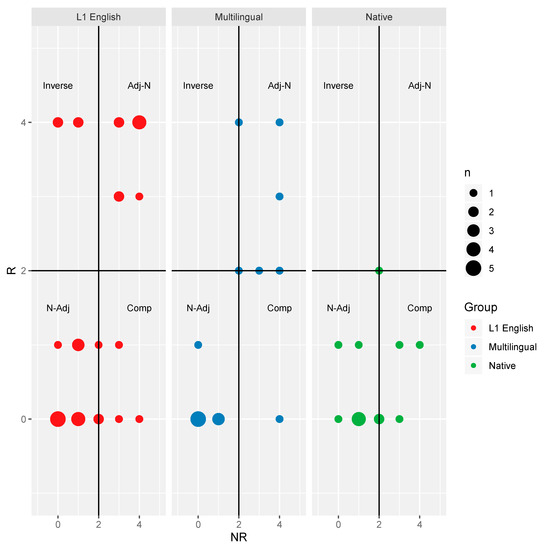

We classify individual participants as to their selection pattern of pre-nominal adjectives. Figure 2, is divided into three subplots corresponding to speaker group (L1 English, Multilingual, Native). The size of the points on the plot are scaled to represent counts of individual participants. The position of the points on the x-axis represents the number of pre-nominal adjective choices in the NR context, whereas the position of the points on the y-axis represents the number of pre-nominal adjective choices in the R context.

Figure 2.

Counts of individual speakers plotted by number of Adj–N choices given the R condition and the NR condition (Inverse, Adj–N dominant, N–Adj dominant, Comp(lementary)).

The far-right subplot shows that Native speakers either follow a complementary pattern, choosing more pre-nominal adjectives in the NR context than the R context, or are noun–adjective (N–Adj) dominant, dispreferring adjective-noun (Adj–N) order regardless of context. Three native speakers allude the fine-grained classification that division of the subplots into quadrants attempts to achieve. Two chose pre-nominal adjectives in 2/4 NR contexts, and, thus, were neither clearly complementary nor N–Adj dominant. Another showed no clear pattern regardless of context, a surprising, but not entirely unexpected result, given the possibility of focus fronting (see Demonte 2008). Unlike native speakers, who overall are either complementary or N–Adj dominant, L1 English and Multilingual learners of Spanish cluster in the Adj–N or N–Adj dominant regions, showing preferences for one word order, but not clear sensitivity.

Finally, we examined whether preferring more pre-nominal adjectives in the NR condition than in the R condition correlated with the external performance measures for learners of Spanish. We entered the cloze test, dominance score and average contact score against a difference score (Adj–N choices in NR contexts – Adj–N choices in R contexts). We also asked whether preferring more post-nominal adjectives overall correlated with speaker level. We ran two-tailed correlations between external measures and difference scores. For L1 English learners of Spanish, we found moderate negative correlation between dominance score and cloze test (r(27) = −0.65, p < 0.01); between dominance score and contact (r(27) = −0.60, p < 0.01); and a moderate positive correlation between cloze test score and contact (r(30) = 0.39, p < 0.05), but no effects of these measures on adjective scores. For Multilingual learners of Spanish only the correlation between cloze test score and number of N–Adj responses was marginally significant (r(14) = 0.49, p = 0.06); the higher the cloze test score, the more N–Adj responses the participant chose overall.

4.2. Acceptability Judgement Task

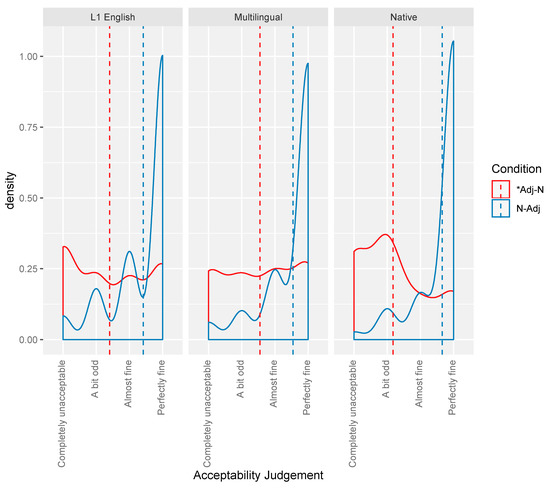

We first analyzed the distribution of acceptability judgements by speaker group for single-relational adjectives. This condition evaluated whether (a) native speakers attended to the task and (b) whether non-native speakers had basic knowledge of the distribution of adjectives in Spanish. To compare acceptability judgements of single-relational adjectives by native Spanish speakers, L1 English and Multilingual learners of Spanish, we converted scalar judgements to a 4-point numeric scale (1 = completely unacceptable, 2 = a bit odd, 3 = almost fine, 4 = completely acceptable). Figure 3, is divided into three subplots that depict the smoothed distribution of responses to ungrammatical Adj–N order compared to grammatical N–Adj order for each speaker group (L1 English, Multilingual, Native); peaks display where responses are concentrated. The dotted lines represent the mean response for each condition. The distributions and mean lines indicate that all groups rate grammatical N–Adj order as more acceptable than ungrammatical Adj–N order. However, the distribution of responses to ungrammatical Adj–N order is less concentrated at the lower end of the scale. This is true overall, and for both non-native speaker groups compared to the native speakers.

Figure 3.

Density plot of acceptability judgements for pre- and post-nominal relational adjectives (*Adj–N/ N–Adj) given speaker group (L1 English, Multilingual, Native).

To further compare acceptability judgements of single-relational adjectives by speaker group, we fitted a linear-mixed effect model using the restricted maximum likelihood method in R. We obtained p-values for regression coefficients using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al. 2017). The model included participants and items as random effects and the interaction of the fixed effects language group and adjective order (Table 5). The fit of this model was significantly better than a model with no interaction between the fixed effects language group and context (AIC = 1419.7 vs. 1421.6), χ2(2) = 5.9, p = 0.05.

Table 5.

Linear model testing the effect of language group and adjective order (*Adj–N/N–Adj) on acceptability judgements (formula: Acceptability Judgement~Group * Adjective Order + (1|Participant) + (1|Item)).

The single adjective model indicated a significant effect of adjective order; native Spanish speakers judged N–Adj order as significantly better than Adj–N order. The model also indicated a significant interaction of Spanish learner groups by adjective order. L1 English and Multilingual learners of Spanish judged N–Adj order as significantly less acceptable than native Spanish speakers.

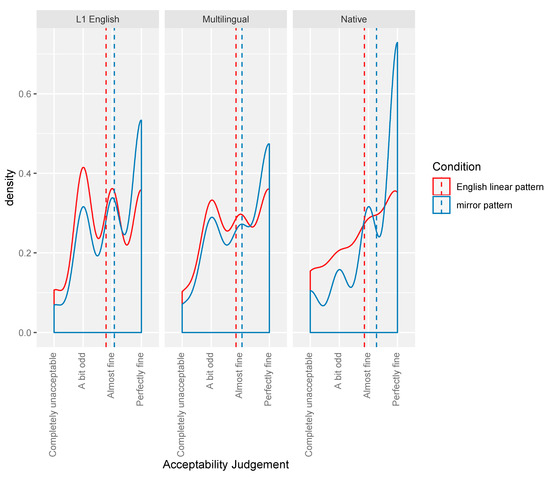

We perform the same analysis for two-adjective sequences. Figure 4 is divided into 3 subplots that depict the smoothed distribution of responses to the mirror pattern compared to the English linear pattern for each speaker group (L1 English, Multilingual, Native). Again, peaks display where responses are concentrated and dotted lines represent the mean response for each condition. The distributions and mean lines indicate that all groups rate the mirror pattern as more acceptable than the English linear pattern.

Figure 4.

Density plot of acceptability judgements for two-adjective sequences given speaker group (L1 English, Multilingual, Native).

As before, we fitted a linear-mixed effect model using the restricted maximum likelihood method in R to compare acceptability judgements of multiple adjectives by native Spanish speakers, L1 English and Multilingual learners of Spanish. The model included participants and items as random effects and the fixed effects language group and adjective order (mirror pattern vs. English linear pattern) (Table 6). The fixed effect adjective type (qualifying + qualifying, relational + qualifying) was excluded as it did not improve the fit of the model according to the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) (1386.9 vs. 1388.8), χ2(1) = 0.09, p = 0.76. The fit of the model was significantly better than a minimal model containing only the random effects (participants and items) (AIC = 1386.9 vs. 1393), χ2(3) = 12.2, p < 0.01. A third model was generated to test for the interaction between language group and adjective order. The interaction was not significant and failed to improve the fit of the model (AIC = 1386.9 vs. 1390.2), χ2(2) = 0.74, p = 0.69.

Table 6.

Linear model testing the effect of language group and adjective order (mirror pattern, English linear pattern) on acceptability judgements (formula: Acceptability Judgement~Group + Adjective Order + (1|Participant) + (1|Item)).

The multiple adjective model indicated a significant effect of adjective order; the mirror pattern significantly increases acceptability judgement ratings for all groups. There were no significant differences among the Native Spanish speakers, the L1 English, and Multilingual learners of Spanish.

We also examined individual performance by classifying the individual speaker as to whether they rated the mirror pattern on average as more acceptable than the English linear pattern (average mirror image rating–average post-posed English rating (Table 7).

Table 7.

Individual speakers classified as to their preferred word order pattern with respect to multiple adjectives (mirror image, English linear, or not distinguishing).

The majority of speakers in each group rated the mirror pattern as on average more acceptable than English linear pattern. Interestingly, some variability is also evident amongst L1 speakers, four of whom rated English linear pattern as on average more acceptable than mirror image order. However, recall, that the contrast is one of markedness; marked orders are possible particularly with respect to sequences of two-qualifying adjectives. Of those native speakers who rated the English linear pattern as more acceptable, three out of four did so on the basis of two-qualifying adjectives.

Finally, we examined whether performance on the task correlated with the external measures of performance for L1 English and Multilingual learners of Spanish. Specifically, we asked whether rating the mirror pattern as more acceptable than English linear pattern (average mirror pattern rating–average English linear pattern rating, henceforth two-adjective sequence score) correlated with speaker level as measured by the cloze test, dominance score or average contact score. We also asked whether rating single-relational adjectives as more acceptable in post-nominal position correlated with speaker level (avg. N–Adj rating–avg. Adj–N rating, henceforth single-relational score). We ran a series of two-tailed correlations between external measures and difference scores. For L1 English learners of Spanish, there were moderately strong negative correlations between dominance score and the two-adjective sequence score, r(27) = −0.52, p < 0.01; and the single-relational score, r(27) = −0.58, p < 0.001. Recall that positive dominance scores reflect greater English dominance, so as participants English dominance decreased, cloze test score, Spanish contact, and performance on the single and multiple AJTs increased. There were moderately strong positive correlations between cloze test score and two-adjective sequence score, r(31) = 0.34, p < 0.05; and the single-relational score, r(31) = 0.54, p < 0.01. Participants with higher cloze test scores reported greater Spanish contact and performed better on the single and multiple AJTs. Finally, there was a moderately strong positive correlation between the two-adjective sequence score and the single-relational score, r(31) = 0.49, p < 0.01. Unsurprisingly, better performance on the single AJT equated to better performance on the multiple AJT.

For Multilingual learners of Spanish, there were moderately strong positive correlations between the cloze test score and the two-adjective sequence score, r(15) = 0.68, p < 0.01; and the single-relational score, r(15) = 0.58, p < 0.05. Participants with higher cloze test scores preferred mirror pattern and obligatorily post-nominal relational adjectives. Finally, the correlation between dominance score and the difference score (average N–Adj rating – average. Adj–N rating) was negative, moderately strong and statistically significant, r(15) = 0.64, p < 0.01; as English dominance decreased participants preferred obligatorily post-nominal relational adjectives.

5. Discussion

We began by examining the underlying analysis of single post-nominal adjectives in context, a problem that has not been explicitly treated in the experimental literature. We asked:

- Do native Spanish speakers prefer pre-nominal adjectives in nonrestrictive contexts and post-nominal adjectives in restrictive contexts as complementarity predicts? Or do they prefer the post-nominal regardless of context as predicted by post-nominal ambiguity?

- Do Spanish learners evidence complementarity as predicted by explicit instruction or post-nominal ambiguity?

Overall, native speaker results from the PT are consistent with post-nominal ambiguity. Even in nonrestrictive contexts, native speakers preferred Adj–N order less than 50% of the time. Individual analysis further supports this finding; despite a select few preferring the context dependent complementary distribution of adjectives predicted by the complementary approach, the majority of native speakers preferred N–Adj order regardless of context. As a group non-native speakers differed from native speakers in the restrictive context where they failed to disprefer Adj–N order. However, individual analysis revealed two main groups of speakers: the majority of non-native speakers were N–Adj dominant, but Adj–N-dominant speakers followed closely behind. These results are noteworthy given that pedagogical materials teach complementarity. When non-native speakers converge on one of the two patterns evidenced by native speakers, they converge on the dominant native speaker pattern, not the dispreferred pattern highlighted by explicit instruction. Finally, while the correlations between proficiency measures in the L1 English group point to their consistency, a lack of correlation between these measures and task performance (i.e., a preference for more pre-nominal adjectives in the nonrestrictive condition than the restrictive condition, or a preference for more post-nominal adjectives overall) is unsurprising. Interestingly, we do not find the same correlations between proficiency measures for the Multilingual group. The heterogeneity of language experience in this group might explain this discrepancy. The moderately significant correlation between an overall preference for post-nominal adjectives and the cloze test may also relate to such language experience and multilinguals’ need for increased proficiency to converge on post-nominal ambiguity.

Next, we examined two-adjective sequences and structural reanalysis. We asked:

- Do native Spanish speakers judge the mirror image pattern as more acceptable than the English linear pattern?

Native Spanish speakers’ preferred mirror image ordering reflects the predictions of both the intersective > non-intersective and the unified base hypotheses; they tend to reject the order that corresponds to English linear order (albeit post-nominal). We next sought to determine whether Spanish learners showed sensitivity to lexical classes and their preferred placement. The results of an AJT that manipulated the position of obligatorily post-nominal relational adjectives confirmed that both non-native and native speakers successfully identified certain lexical classes of adjectives as restricted to a specific position in the noun phrase. While the difference between acceptable and unacceptable orders was smaller for Spanish learners compared to native speakers, all groups clearly distinguished between the acceptability of these adjectives in pre- and post-position. Having thus established that these Spanish learners possessed basic distributional competence, we turned to two-adjective sequences. We asked:

- Do Spanish learners have intuitions about preferred orderings of two-adjective sequences? Specifically, do they favor the mirror image pattern predicted by structural reanalysis or do they prefer the English-linear pattern as predicted by surface level learning accounts?

We find crucial evidence for non-native structure building; Spanish learners judged the mirror pattern as more acceptable than the English linear pattern, and did so to the same degree as native speakers. Finally, performance on the AJT for both single and two-adjective sequences correlated with other measures of language ability.

6. Conclusions

Do adult non-native Spanish speakers restructure the determiner phrase (DP) to reflect the target grammar? We argued that previous studies overestimated complementarity in native speakers, and likewise, in learners. For learners, furthermore, we argue that a combination of explicit instruction and access to the first language (L1) could explain these results. The present study assessed native and non-native speaker’s underlying grammars via (a) adjective ordering preference in context, and (b) acceptability judgements of adjective ordering based on lexical class (i.e., relational, qualifying, etc.). At the individual level, our work is consistent with previous work pointing to ultimate attainment of the relationship between word order and restrictivity. We go a step further, in finding non-native convergence in a domain that is not explicitly taught, and where the input is scarce, and ambiguous, unless underpinned by underlying knowledge of hierarchical structure. Here, non-native speakers pattern with native speakers who prefer the mirror pattern for two-adjective sequences. Overall, contra approaches that attribute limited surface level learning (Meisel 2011) to adult learners, our data shows non-native speakers disprefer surface-level, lineal representations in this domain. While lower proficiency non-native speakers may resort to surface level learning, as their proficiency increases, they can, and do, project new structures, and map them to the correct semantics.

Beyond the contribution to our understanding of the possibilities of second language acquisition, the present study offers an empirical evaluation of competing theoretical characterizations of (a) the association between adjectival placement and interpretation and (b) the unmarked order of two-adjective sequences in Spanish. These results can and ought to inform pedagogy, which ideally captures both the dominant native speaker grammar as well as points of variation. We find support for post-nominal ambiguity approaches, which argue that the post-nominal position is unmarked regardless of context, as well as the unified base and the intersective>non-intersective hypotheses, which coincide in the unmarked Spanish adjective order is the mirror pattern of unmarked English adjective order. Regardless of subfield or theoretical framework, experimental work invites the opportunity to re-evaluate our assumptions about the organization of language in the mind across speaker populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology was shared between the three authors. Data collection was carried out by E.P. and G.K. Writing was done by E.P., review and editing by A.T.P.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to A. T. Pérez Leroux (SSHRC 435-2014-2000, “Development of NP complexity in children” and a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council to E. Pettibone (SSHRC 767-2016-1158).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO (protocol code 31161 and 26 January 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to Petra Shultz, Merle Weicker, Yves Roberge and members of the Complexity and Recursion Project for their valuable insights at various stages of this project. We are most indebted to the adults who participated in this study. Above all, this work would not have been possible without the support of Beatriz Calero Quintero.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Preference Task.

Table A1.

Preference Task.

| Item | Set | Condition | Stimuli | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | NR | Los poderosos super-héroes/super-héroes poderosos nunca tienen miedo de nada. “The powerful superheroes/superheroes powerful are never afraid of anything” | Para ser súper-héroe, hay que tener mucha fuerza y poderes especiales. “To be a superhero, you have to be very strong and have special powers.” |

| 2 | B | R | Los empleados poderosos/#poderosos empleados reciben buenos beneficios.$“The employees powerful/#powerful employees receive good benefits” | En esa organización hay algunos individuos muy poderosos, y otros que no cuentan a pesar de que han trabajado allí por años. “In that organization, there are some very powerful individuals and others that don’t count for anything even though they’ve worked there for years” |

| 3 | B | NR | Mis amigas siempre quieren ir a los juegos del NBA porque les encantan los altos jugadores/jugadores altos de básquetbol. “My friends always want to go to NBA games because they love the tall basketball players/basketball players tall.” | Los jugadores de básquetbol profesional son todos altisímos. “Professional basketball players are all very tall.” |

| 4 | A | R | Las primas altas/#altas primas no usan tacones. “The cousins tall/#tall cousins don’t wear heels.” | Algunas primas mías son altas. Otras no, porque salieron a la abuela, que es bajita. “Some of my cousins are tall. Others aren’t because they come from Grandma who is short” |

| 5 | A | NR | En las portadas de las revistas principales sólo figuran fotos de las bellas supermodelos/supermodelos bellas “Only photos of beautiful supermodels/supermodels beautiful appear on the cover of big magazines” | Para ser supermodelo hay que ser de espectacular hermosura. “To be a supermodel you have to be spectacularly beautiful.” |

| 6 | B | R | En el periódico salieron fotos de las modelos bellas./ #las bellas modelos. “Photos of models beautiful/#beautiful models appeared in the newspaper” | En los desfiles de moda de hoy, algunas modelos son bellísimas; otras son horribles, parecen monstruos. “In today’s fashion shows, some models are beautiful; others are horrible, they look like monsters.” |

| 7 | B | NR | Los valientes toreros/Los toreros valientes no tienen miedo de arriesgar la vida. “The brave bullfighters/bullfighters brave are not afraid to risk their lives” | No hay torero que no sea conocido por su coraje; es decir ser torero es enfrentar peligro a diario.$“There isn’t a bullfighter who is not known for their courage, it is to say that to be a bullfighter is to face danger every day” |

| 8 | A | R | Los soldados valientes arriesgan la vida con frecuencia./#Los valientes soldados arriesgan la vida con frecuencia. “The soldiers brave/#brave soldiers risk their lives frequently.” | Algunos soldados son valientes; otros son cobardes. “Some soldiers are brave; others are cowards.” |

| 9 | A | NR | Sus inteligentes empleados ganan buen dinero./Sus empleados inteligentes ganan buen dinero. “Their intelligent employees/employees intelligent earn good money.” | La empresa Google sólo contrata genios. “Google only hires geniuses.” |

| 10 | B | R | Los estudiantes inteligentes /#inteligentes estudiantes recibirán mención honorífica. “The students intelligent/#intelligent students will receive honorable mention.” | Siempre hay unos estudiantes más inteligentes que otros. “There are always some students that are more intelligent than others.” |

| 11 | B | NR | Las fuertes mujeres/mujeres fuertes sabían utilizar armas. “The strong women/women strong knew how to use weapons.” | En la época medieval, a las mujeres les tocaba defender los castillos. “In the middle ages women had to defend the castles.” |

| 12 | A | R | Las mujeres fuertes/#fuertes mujeres siempre hacen un esfuerzo. “The woman strong/#strong women always do a lot of exercise.” | En el gimnasio, unas mujeres se dedican mucho al ejercicio mientras que otras son más flojas. “At the gym, some women dedicated themselves to exercise while others are weaker.” |

| 13 | A | NR | Los rápidos caballos/caballos rápidos esperan impacientes la señal de empezar. “The fast horses/horses fast impatiently await the start signal.” | Hoy es día de carreras de caballos. No sé por cual apostar. ¡Son todos excelentes! “Today is horse racing day. I don’t know which to bet on. They are all excellent!” |

| 14 | B | R | Los corredores rápidos/#rápidos corredores van a llegar a la meta antes que los demás. “The runners fast/#fast runners are going to arrive at the finish line before the others.” | En el maratón, hay unos corredores más rápidos que otros. “In the marathon, there are some runners that are faster than others.” |

| 15 | B | NR | Nuestros saludables platos/platos saludables contienen poca grasa. “Our healthy dishes/dishes healthy contain little fat.” | En este restaurante vegetariano sólo servimos comida sana, orgánica y bien preparada. “In this vegetarian restaurant we only serve healthy, organic, well prepared food.” |

| 16 | A | R | Los platos saludables/#saludables platos no contienen mucha grasa. “The dishes healthy/#healthy dishes don’t contain much fat.” | En este restaurante, hay platos que son más saludables y engordan menos que otros. “At this restaurant, there are dishes that are healthier and less fattening than others.” |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Acceptability Judgement Task.

Table A2.

Acceptability Judgement Task.

| Item | Set | Position | Stimuli | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | NA | Por eso, el abogado firmó el contrato legal en nombre de su cliente. “That’s why the lawyer signed the contract legal in the name of his client.” | El juez quería que se presentaran los documentos inmediatamente. “The judge wanted the documents to be filed immediately.” |

| 1 | B | *AN | Por eso, el abogado firmó *el legal contrato en nombre de su cliente. “That’s why the lawyer signed *the legal contract in the name of his client.” | *El juez quería que se presentaran los documentos inmediatamente. “The judge wanted the documents to be filed immediately.” |

| 2 | A | NA | En este país hace falta realizar una reforma política. “In this country, reform political is necessary.” | Los problemas en México siguen empeorando. “The problems in Mexico keep getting worse.” |

| 2 | B | *AN | En este país hace falta realizar *una política reforma. “In this country, *political reform is necessary.” | Los problemas en México siguen empeorando. “The problems in Mexico keep getting worse.” |

| 3 | A | NA | Ella es la jefa de la revista mensual de la universidad. “She is the head of the university’s magazine monthly.” | Luisa López ha tenido éxito en su carrera.$“Luisa López has had success in her career.” |

| 3 | B | *AN | Ella es la jefa de la mensual revista de la universidad. “She is the head of the university’s *monthly magazine.” | Luisa López ha tenido éxito en su carrera.$“Luisa López has had success in her career.” |

| 4 | A | NA | Por eso, vivo lejos del centro, en la zona industrial.$“That’s why I live far from the center, in the area industrial.” | Los apartamentos en el centro de la ciudad son demasiado caros. “The apartments in the city center are too expensive.” |

| 4 | B | *AN | Por eso, vivo lejos del centro, en *la industrial zona. “That’s why I live far from the center, in *the industrial area.” | Los apartamentos en el centro de la ciudad son demasiado caros. “The apartments in the city center are too expensive.” |

| 5 | B | NA | Rompieron la mesa metálica de Sara. “They broke Sara’s table metallic.” | La fiesta de anoche se descontroló. “The party last night got out of control.” |

| 5 | A | *AN | Rompieron *la metálica mesa de Sara. “They broke Sara’s *metallic table.” | La fiesta de anoche se descontroló. “The party last night got out of control.” |

| 6 | B | NA | Aprendimos sobre la energía solar. “We learned about energy solar.” | El curso de estudios del medio ambiente tocó varios temas. “The course on the environment touched on various topics.” |

| 6 | A | *AN | Aprendimos sobre *la solar energía. “We learned about *solar energy.” | El curso de estudios del medio ambiente tocó varios temas. “The course on the environment touched on various topics.” |

| 7 | B | NA | Encontré un juguete plástico debajo de la mesa. “I found a toy plastic under the table.” | Estuve limpiando la casa después de que se fueron los niños. “I was cleaning the house after the kids left.” |

| 7 | A | *AN | Encontré un plástico juguete debajo de la mesa. “I found a *plastic toy under the table.” | Estuve limpiando la casa después de que se fueron los niños. “I was cleaning the house after the kids left.” |

| 8 | B | NA | Él merece el respeto personal de todos. “He deserves everyone’s respect personal.” | José es un hombre honrado y competente. “José is an honorable and competent man.” |

| 8 | A | *AN | Él merece *el personal respeto de todos. “He deserves everyone’s *personal respect.” | José es un hombre honrado y competente. “José is an honorable and competent man.” |

| 1 | A | NA2A1 | Acaba de comprar unas cortinas amarillas horribles para la sala. “She just bought some curtains yellow horrible for the living room.” | Mi hermana está redecorando la sala. “My sister is redecorating the living room.” |

| 1 | B | #NA1A2 | Acaba de comprar #unas cortinas horribles amarillas para la sala.$“She just bought #some curtains horrible yellow for the living room.” | Mi hermana está redecorando la sala. “My sister is redecorating the living room.” |

| 2 | A | NA2A1 | Sé que le va a parecer feo, pero me voy a poner el saco negro desteñido. “I know she is going to think it is ugly, but I am going to wear the jacket black faded.” | A mi mamá no le gusta cómo visto. “My mother doesn’t like how I dress.” |

| 2 | B | #NA1A2 | Sé que le va a parecer feo, pero me voy a poner #el saco desteñido negro. “I know she is going to think it is ugly, but I am going to wear #the jacket faded black.” | A mi mamá no le gusta cómo visto. “My mother doesn’t like how I dress.” |

| 3 | B | NA2A1 | Compró una mesa redonda cara para la sala. “She bought a table round expensive for the living room.” | Mi mamá se fue de compras. Le fascinan los muebles. “My mom went shopping. She loves furniture.” |

| 3 | A | #NA1A2 | Compró #una mesa cara redonda para la sala. “She bought #a table expensive round for the living room.” | Mi mamá se fue de compras. Le fascinan los muebles. “My mom went shopping. She loves furniture.” |

| 4 | B | NA2A1 | Entonces, se comió un melón verde podrido. “So, he ate a melon green rotten.” | Cuando llegó de la escuela, el niño tenía hambre. “When he got home from school, the boy was hungry.” |

| 4 | A | #NA1A2 | Entonces, se comió #un melón podrido verde. “So, he ate #a melon rotten green.” | Cuando llegó de la escuela, el niño tenía hambre. “When he got home from school, the boy was hungry.” |

| 5 | A | NA2A1 | Tienen que usar un manual escolar confuso. “They have to use a manual school confusing.” | Los estudiantes no van a aprender mucho en esta clase. “The students aren’t going to learn a lot in this class.” |

| 5 | B | #NA1A2 | Tiene que usar #un manual confuso escolar. “They have to use #a manual confusing school.” | Los estudiantes no van a aprender mucho en esta clase. “The students aren’t going to learn a lot in this class.” |

| 6 | A | NA2A1 | Al fin, el barco logró llegar al puerto marítimo grande. “At last the boat managed to reach the port maritime large.” | Anunciaron un huracán. El crucero Queen Eilzabeth no podía detenerse en las islitas. “They announced a hurricane. The Queen Elizabeth cruise ship couldn’t stop at the small islands.” |

| 6 | B | #NA1A2 | Al fin, el barco logró llegar #al puerto grande marítimo. “At last the boat managed to reach #the port large maritime.” | Anunciaron un huracán. El crucero Queen Eilzabeth no podía detenerse en las islitas. “They announced a hurricane. The Queen Elizabeth cruise ship couldn’t stop at the small islands.” |

| 7 | B | NA2A1 | El paseo campestre largo fue la mejor actividad. “The walk country long was the best activity.” | Fuimos de vacaciones a un hotel y había muchas actividades en la naturaleza. ‘We went on vacation to a hotel and there were lots of activities in nature.’ |

| 7 | A | #NA1A2 | #El paseo largo campestre fue la mejor actividad. “#The walk long country was the best activity.” | Fuimos de vacaciones a un hotel y había muchas actividades en la naturaleza. “We went on vacation to a hotel and there were lots of activities in nature.” |

| 8 | B | NA2A1 | En la finca había una vaca lechera grande. “On the farm, there was a cow milking big.” | Mi abuelo tenía una finca en el campo. “My grandfather had a farm in the countryside.” |

| 8 | A | #NA1A2 | En la finca había #una vaca grande lechera. “On the farm, there was #a cow big milking.” | Mi abuelo tenía una finca en el campo. “My grandfather had a farm in the countryside.” |

References

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2001. Adjective syntax and noun raising: Word order asymmetries in the DP as the result of adjective distribution. Studia Linguistica 55: 217–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, Luiz, and Tom Roeper. 2014. Multiple grammars and second language representation. Second Language Research 30: 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Bruce. 2001. Adjective position and interpretation in L2 French. In Romance Syntax, Semantics and L2 Acquisition. Edited by Joaquim Camps and Caroline R. Wiltshire. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Bruce. 2007a. Learnability and parametric change in the nominal system of L2 French. Language Acquisition 14: 165–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Bruce. 2007b. Pedagogical rules and their relationship to frequency in the input: Observational and empirical data from L2 French. Applied Linguistics 28: 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Bruce. 2008. Forms of evidence and grammatical development in the acquisition of adjective position in L2 French. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 30: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulou, Antonia, Manuel Español–Echevarría, and Philippe Prévost. 2008. On the acquisition of the pre-nominal placement of evaluative adjectives in L2 Spanish. Paper presented at 10th Hispanic Linguisitics Symposium, London, Ontario Canada, 19–22 October 2006; Edited by Joyce Bruhn de Garavito and Elena Valenzuela. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Judy B. 1993. Topics in the Syntax of Nominal Structure across Romance. Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bleichmar, Guillermo, and Paula Cañón. 2016. Taller de Escritores, Grammar and Composition for Advanced Spanish, 2nd ed. Boston: Vista Higher Learning, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bolinger, Dwight. 1967. Adjectives in English: Attribution and predication. Lingua 18: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, José. 2018. The interpretation of Adjective-N Sequences in Spanish Heritage. Languages 3: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno-Pulido, Alberto. 2012. Variability in Spanish adjectival position: A corpus analysis. Sintagma 24: 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Jacee, and Roumyana Slabakova. 2014. Interpreting definiteness in a second language without articles: The case of L2 Russian. Second Language Research 30: 159–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2010. The Syntax of Adjectives: A Comparative Study. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2014. The semantic classification of adjectives. A view from syntax. Studies in Chinese Linguistics 35: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen, Harald, and Claudia Felser. 2006. Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics 27: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, Harald, and Claudia Felser. 2018. Some notes on the shallow structure hypothesis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40: 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Vivian. 2006. The poverty-of-the-stimulus argument and structure-dependency in L2 users of English. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 41: 201–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Garavito, Joyce Bruhn. 2019. The prosodic transfer hypothesis: Possible application to Spanish clitics. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 9: 816–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Garavito, Joyce Bruhn, and Lydia White. 2002. The second language acquisition of Spanish DPs: The status of grammatical features. In The Acquisition of Spanish Morphosyntax: The L1/L2 Connection. Edited by Ana Teresa, Pérez-Leroux and Juana Liceras. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 153–78. [Google Scholar]

- Demonte, Violeta. 1999a. El adjetivo: Clases y usos. La posición del adjetivo en el sintagma nominal. In Gramática descriptiva de la Lengua Española: Sintaxis Básica de las Clases de Palabras. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa Calpe, pp. 129–216. [Google Scholar]

- Demonte, Violeta. 1999b. A minimal account of Spanish adjective position and interpretation. In Grammatical Analyses in Basque and Romance Linguistics. Edited by Jon A. Franco, Alazne Landa and Juan Martín. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Demonte, Violeta. 2008. Meaning-form correlations and adjective position in Spanish. In Adjectives and Adverbs: Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse. Edited by Louise McNally and Christopher Kennedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2017. The syntax and semantics of nominal modifiers in Spanish: Interpretation, types and ordering facts. Borealis 6: 1–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- File-Muriel, Richard J. 2006. Spanish adjective position: Differences between written and spoken discourse. In Functional Approaches to Spanish Syntax. Edited by J. Clancy Clements and Jiyoung Yoon. New York: Springer, pp. 203–18. [Google Scholar]

- Finnemann, Michael D., and Lynn Carbón. 2001. De Lector a Escritor: El Desarrollo de la Comunicación Escrita, 2nd ed. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [Google Scholar]

- Gess, Randall, and Julia Herschensohn. 2001. Shifting the DP parameter: A study of Anglophone French L2ers. In Romance Syntax, Semantics and L2 Acquisition. Edited by Joaquim Camps and Caroline R. Wiltshire. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro-Fuentes, Pedro. 2012. The acquisition of interpretable features in L2 Spanish: Personal a. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 701–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]