Abstract

This study investigates the effects of task-essential training on offline and online processing of verbal morphology and explores how working memory (WM) modulates the effects of training. We compare a no-training control group to two training groups who completed a multisession task-essential training focused on Spanish verbal inflections related to person–number agreement and tense. Effects of training were evaluated using an offline aural interpretation task and an online self-paced reading (SPR) assessment, administered as a pretest, posttest, and delayed posttest. Results showed that training led to more accurate interpretation of both person-number and tense information in the offline interpretation test. While higher WM was associated generally with greater accuracy, higher WM did not lead to greater gains from training. The SPR results showed that training did not increase sensitivity to subject–verb agreement or adverb–verb tense violations. However, among participants who underwent training, WM enhanced sensitivity under some conditions. These results demonstrate a role for individual differences in WM for offline and online processing, and they suggest that while task-essential training has been shown repeatedly to improve offline processing of target forms, its effects on online processing of redundant verbal morphology are more limited. Implications for L2 learning are discussed.

1. Introduction

Research on second language (L2) acquisition and sentence processing has established strong links between which forms are processed in the input and what is eventually acquired (Dekydtspotter and Renaud 2014; Fodor 1998; see VanPatten 2015a, 2015b). Therefore, numerous studies have addressed whether targeted interventions or training alter a learner’s processing and facilitate L2 acquisition. These studies have used a range of different interventions—most notably Structured Input activities (Wong 2004)—which aim to facilitate the establishment of form–meaning connections through systematic meaningful use of a target form. In these interventions, learners must use the target form to complete a meaningful task successfully. Training (or practice) of this type has therefore been referred to as “task essential”1. In this way, task-essential training is different from other types of focus-on-form instruction, such as input enhancement, which may call attention to a target form, but do not require learners to comprehend or produce the form meaningfully. Indeed, prior studies have shown that task-essential training pushes learners to link morphosyntactic forms with their meanings (e.g., Cadierno 1995; Ellis et al. 2014; Sanz and Morgan-Short 2004; VanPatten 2017) and increases accuracy in offline tasks. Researchers have therefore inferred that task-essential training alters learners’ processing strategies and promotes acquisition.

Yet, this inference raises two issues that merit further research. First, while prior studies have shown consistent benefits of task-essential training in offline assessments, recent scholarship has shown conflicting results regarding training’s effects on the development of morphosyntactic processing strategies in online processing (e.g., McManus and Marsden 2017, 2018; Wong and Ito 2018). Thus, it is not clear to what extent such treatments alter processing strategies in real time. Second, previous studies have not fully considered whether individual differences amongst L2 learners, particularly differences in working memory (WM), condition the effects of treatment on processing strategies. Consequently, studies that investigate the effects of training on morphosyntactic processing should take a more comprehensive approach, which includes both offline and online measures as well as an exploration of the extent to which WM modulates training outcomes.

In order to address this gap in the literature, the present study reports on the effects of a multisession task-essential training. It evaluates (a) whether training pushes learners to process Spanish person-number and tense inflections in both offline and online tasks, and (b) the degree to which offline and online processing is modulated by working memory capacity. In doing so, this study contributes to research on task-essential training, morphological processing, and the role of individual differences.

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Input Processing and Task-Essential Training

Models of L2 development have long posited a strong role for processing in the acquisition of grammar (e.g., Dekydtspotter and Renaud 2014; Fodor 1998; VanPatten 2015b), and it is now clear that acquisition minimally requires the processor to identify important linguistic cues and link these to their meanings. Therefore, the allocation of attentional resources and attention to various types of linguistic information play an outsized role in what is acquired. For instance, psycholinguistic studies show that beginning and intermediate L2 learners often attend to lexical information to determine tense, rather than using verbal morphology (Cameron 2011; Dracos and Henry 2018; Ellis and Sagarra 2010b; Sagarra 2007; VanPatten and Keating 2007). This finding has been codified within VanPatten’s Input Processing model (VanPatten 2015b) as the Lexical Preference Principle, which predicts that, for example, when beginning L2 learners comprehend Spanish sentences such as Yo visité a mi familia la semana pasada (‘I visited my family last week’), they will tend to rely on the phrase la semana pasada (‘last week’) to understand tense, rather than processing the first-person past-tense morpheme -é on the verb visité, ‘visited’. Although the underlying theoretical assumptions are different, models of learned attention and cue blocking make similar predictions given that salient lexical and discourse cues typically overshadow verbal morphology in natural learning contexts (see, e.g., Ellis and Sagarra 2010a, 2010b). These processing-based accounts explain, in part, why morphological difficulties often persist late into development (e.g., Lardiere 1998).

Research on focus-on-form instruction (see Norris and Ortega 2000) has shown that training pushes learners to attend to these forms and develop form–meaning connections when the form is task essential and must be processed in order to complete the given task correctly. Although many variations of task-essential training exist, the most well-defined and theoretically motivated of these, Structured Input (SI) activities, are subsumed within Processing Instruction (PI) (see VanPatten and Cadierno 1993; Wong 2004). SI activities are designed to help learners circumvent non-optimal processing strategies, such as those represented in VanPatten’s (2015b) Input Processing model (e.g, Lexical Preference Principle)2. In SI activities, input is manipulated so that learners must rely on target grammatical forms. For example, in training targeting tense information, learners see sentences such as Visité a mi familia, (‘Visited.1sg.past my family). They then determine whether the event is happening now or has already happened. Because a time adverbial (e.g., “yesterday”) is absent from the input, the learners must process the tense information encoded on the verb in order to understand the question properly. Correct answers demonstrate that they have understood the meaning encoded in the target form (Shintani 2015), and learners receive feedback as to whether they have answered the question correctly3. These features separate task-essential training from other types of instructional interventions, e.g., Enriched Input (Marsden 2006) or input enhancement (Russell 2012).

As stated previously, PI is not the only type of task-essential training. Yet, its theoretical motivation and application is the clearest and best defined in the psycholinguistic and pedagogical literatures, and research on PI lends the most evidence that task-essential training alters comprehension processes in multiple instructional contexts (see Lee 2015). PI research has targeted a variety of morphosyntactic forms, including verbal morphology in Spanish, the focus of the present study. Cadierno (1995) compared the effects of PI to traditional instruction (TI), testing learners’ comprehension and production of preterite verb forms in Spanish. Importantly, the PI group did not practice production of the target form, while the TI group only received productive drills and did not engage in task-essential comprehension. Cadierno found that one month after treatment, the PI group outperformed the TI group on comprehension and equaled their gains on production. Because PI led to gains in both comprehension and production, Cadierno concluded that PI had pushed the learners to process the target form, “which in turn had an effect on their developing system” and “provided learners with knowledge available for both comprehension and production” (p. 188). Many other studies on PI have found comparable results for both similar (e.g., Benati 2001, 2005) and different forms (Henry 2015; VanPatten and Cadierno 1993; VanPatten and Oikkenon 1996), attributing learner gains to changes in processing behavior.

2.2. Task-Essential Training and Processing Measures

Studies on PI and other forms of task-essential training (e.g., Filgueras-Gomez 2016) have traditionally used offline pretests/posttests as the primary assessment measures and inferred that changes in learners’ accuracy are directly relatable to changes in processing behavior. Yet, recent research suggests that these measures are not well suited to observing changes in learners’ processing behaviors, because traditional offline tasks often test the application of an explicit rule (Wong and Ito 2018; see VanPatten 2015a) or the eventual interpretation of an utterance. They, therefore, do not assess either the degree to which participants used individual redundant cues for meaning or how they processed cues in real time. Because processing measures track moment-by-moment processing behaviors, they provide more detailed information about how linguistic forms contribute to learners’ interpretation of the input and minimize the contribution of explicit knowledge. This makes them more appropriate for testing task-essential training’s contribution to the development of processing strategies and implicitly gained knowledge (see Keating and Jegerski 2015). Recent research has consequently begun to employ psycholinguistic methodologies to investigate the effects of task-essential training (Dracos and Henry 2018; Henry 2015; Issa and Morgan-Short 2019; Lee and Doherty 2018; McManus and Marsden 2017, 2018; Wong and Ito 2018).

Several studies that investigate cue use among L2 learners have utilized forced-choice comprehension tasks that indicate which cue the learners used to interpret an utterance. In such tasks, learners process sentences with conflicting tense cues (e.g., an adverbial phrase pointing to the past and a verb marked for future tense). They then have to decide when the action occurred. Because the adverbial phrase and verbal morphology point to different tenses, answers indicate which cue the learners used most frequently. Studies have shown that learners rely on cues differently depending on their learning experience. Ellis and Sagarra (2010a, 2010b) and Ellis et al. (2014), for example, showed that attention to one cue (e.g., an adverb) during training subsequently blocks attention to other cues (e.g., morphology). Using a pretest–posttest design, Dracos and Henry (2018) found that task-essential training targeting dispreferred cues (verbal morphology) promotes the use of those cues for interpretation after training.

Several recent studies have used online processing measures, such as SPR and eye tracking, which provide detailed moment-by-moment accounts of sentence processing. Much of this research has investigated forms related to the word order and subject-first biases in L2 processing (see VanPatten 2015b). In general, these studies have shown that PI increases learners’ attention to the target forms and helps learners allocate attention more efficiently (Henry 2015; Issa and Morgan-Short 2019; Lee and Doherty 2018; Wong and Ito 2018), and that this attention is linked to learning gains. However, the extent of PI’s influence varies somewhat within and across these studies. In particular, this research has not yet shown strong links between training and sensitivity to target forms after training.

We are aware of only two studies that used online measures to investigate how task-essential training affects the development of verbal morphology, as the current study does. McManus and Marsden (2017, 2018) used SPR to investigate whether task-essential instruction influenced the processing of the French imparfait. Taken together, these experiments found that task-essential training only had a significant, lasting effect on online processing when it was accompanied by both explicit information about a related form in the learners’ L1 and task-essential practice with both L1 and L2 forms. Yet, when task-essential training focuses only on the L2, no research to date has shown that training pushes learners to process verbal morphology online, despite ample evidence that it influences the learners’ final interpretation of an utterance (e.g., Cadierno 1995; Dracos and Henry 2018; Lee and Benati 2007; Marsden and Chen 2011).

2.3. Working Memory in L2 Learning and Processing

Working memory (WM) involves the temporary maintenance of task-relevant information while performing cognitive tasks (Williams 2012). Contemporary views refer to WM as the cognitive system(s) dedicated to controlling, regulating, and actively maintaining pertinent information in the face of distracting information (e.g., Conway et al. 2008). Models of WM differ in their organization and some underlying assumptions about how the system operates, such as whether or not WM is divided into separable systems such as short-term storage systems and an executive, attentional system that controls information as in Baddeley’s seminal multicomponent model (Baddeley and Hitch 1974; Baddeley 2000). Importantly, though, the function of WM remains similar across different models: “it orders, stores, and manages immediate sensory details until they can be properly incorporated into the cognitive process that must integrate that data” (Linck et al. 2014, p. 862).

Within L2 acquisition research, differences between models of WM are often deemphasized, and experimental research does not generally adjudicate between them. Most important for this research is that individuals vary considerably in their ability to temporarily store and process task-relevant information, leading to individual differences in WM capacity, or the efficacy with which the WM system functions (Linck et al. 2014), which should have implications for language processing. Indeed, influential models of SLA propose a fundamental role for memory and attentional resources. For example, both VanPatten’s (2015a, 2015b) Input Processing model (i.e., the Availability of Resources Principle) and usage-based models (e.g., Ellis et al. 2014; Wulff and Ellis 2018) assume that cognitive resources are limited and that learners therefore filter or select which parts of the input to process.

Although WM has been widely investigated in L2 research, and studies have often produced conflicting results, a growing number of studies have found that WM facilitates learning in immersion settings (e.g., Faretta-Stutenberg and Morgan-Short 2018) and the classroom context (e.g., Linck and Weiss 2015). WM has been implicated in various domains of L2 acquisition including reading comprehension (e.g., Harrington and Sawyer 1992), (morpho)syntactic processing (e.g., Miyake and Friedman 1998) and grammar learning (e.g., Brooks et al. 2006; French and O’Brien 2008; Sagarra 2017). Recent meta-analyses have also supported this link between WM and L2 development (Linck et al. 2014). It is beyond the scope of the present study to discuss this research in detail. We therefore discuss two strands of research relevant to the present study, namely research on the role of WM in input-based grammar training and in online morphological processing.

Several studies have investigated the role of WM on L2 grammatical development following task-essential training. Three such studies focused on learning gains as measured by pretests and posttests. In a study on Latin case markers, Sanz et al. (2016) found that WM explained variation for complete beginners in comprehension when task-essential training involved metalinguistic feedback. WM did not, however, play a role for learners who received a more traditional, explicit grammar explanation prior to training. Villegas and Morgan-Short (2019), in contrast, found a positive relationship between WM and second-semester learners’ development of the Spanish subjunctive when grammatical explanation preceded training; yet they found no effect of WM when learners received no grammar explanation at all. Finally, Santamaria and Sunderman (2015) investigated whether PI for French direct object pronouns differentially affected second- and third-semester learners of varying WM capacity. They found an association between WM and beginners’ performance on an explicit production task (fill-in-the-blank test), but not on an implicit interpretation task (picture selection). These conflicting results suggest that WM effects are highly susceptible to the target structure and task parameters, such as the explicitness of the tasks, the length of training, and the presence and timing of explicit grammar information.

Two studies have used online tasks to investigate the role of WM in learning and processing. In a study on text enhancement, Indrarathne and Kormos (2018) investigated learning and processing of the causative had structure in English. Although they found that WM enhanced receptive and productive learning gains for each of their groups, for the production task, the contribution of WM was greater in the two highly explicit learning conditions as compared to the more implicit ones. Using eye tracking, they also determined that learners with high WM allocated more attention towards the target construction in the more explicit learning conditions, but not in the implicit learning condition (unenhanced text). In contrast, Issa (2019) study on SI found that the lower WM group allocated more attention to the target structure (D.O. pronouns in Spanish). Issa suggested that these conflicting results could be due to high task demands in SI, as opposed to input enhancement. Interestingly, Issa found no differences in learning outcomes for the high and low WM groups, which he suggested could be because they compensated for lower WM with deeper processing during the SI treatment.

Whereas Indrarathne and Kormos (2018) and Issa (2019) focused on how WM affects attention during training—that is, while learners are engaged in creating form–meaning connections—most research on WM in L2 sentence processing has focused on how it affects the real-time use of already-established syntactic and morphosyntactic knowledge. Early research on WM in sentence processing focused on syntactic constructions, with some studies finding that WM did (e.g., Dussias and Pinar 2010; Miyake and Friedman 1998), and other studies finding that WM did not relate to online processing behaviors (e.g., Juffs 2004; but see Juffs and Harrington 2011). Similarly, research focusing on morphosyntactic processing has found effects for WM in some studies (Faretta-Stutenberg 2014; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2010), but not in others (Foote 2011; Grey et al. 2015). Sagarra (2017) accounts for these discrepancies in terms of differences in task demands (see also Havik et al. 2009), the cognitive load of the WM test, and variability in L2 proficiency, where WM effects are found more consistently for low-proficiency learners such as those in the present study.

Taken together, the research suggests that individual differences in WM influences the ability to process forms online, to create form–meaning connections, and to attend to target forms during training. While effects of WM are often mediated by other factors including proficiency, learning context, task demands, explicitness of training, or L1 influence, WM seems to be an important factor in L2 development. The literature, however, has often produced conflicting results and has not adequately addressed whether WM affects the extent of learning gains from training and the ability to use targeted grammatical forms in both offline and online tasks after training.

2.4. The Processing of Verbal Morphology in L2 Spanish, and the Role of Working Memory

The present study focuses on the acquisition and processing of verbal morphology in Spanish. Spanish verbs are inflected for person-number, tense, mood, and aspect. All three verb classes in Spanish (–ar, –er, and –ir) have distinct morphological forms for person-number in the present, preterite, and future tenses (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Verbal Paradigm for Spanish Verb Classes in Present, Preterite, and Future Tenses.

Several studies have examined how L2 learners process Spanish subject and tense morphology online. For example, VanPatten et al. (2012) investigated person–number agreement for present-tense 1st-, 2nd-, and 3rd-person singular forms. Using an SPR task, they found that L1 speakers were sensitive to morphological agreement errors, but third-semester L2 speakers were not. Several studies investigating L2 processing of adverb–verb mismatches (Cameron 2011; Ellis and Sagarra 2010a; Sagarra 2007; VanPatten and Keating 2007) have found that learners tend to rely on lexical information (i.e., adverbial expressions). One such study by VanPatten and Keating (2007) employed an eye-tracking task to measure reading times for participants with varying proficiency. They found that, although L1 Spanish speakers and advanced L2 speakers had longer reading times on verbs when the adverb did not match the tense of the adverb, neither intermediate nor beginning learners showed consistent sensitivity to the mismatch. Together, these studies show that lower proficiency L2 speakers have difficulty processing verbal morphology online. These difficulties seem particularly acute among L1 speakers of morphologically poor languages, who have more difficulty overcoming their bias towards lexical cues (see Sagarra and Ellis 2013).

Several studies have shown that WM affects the degree to which low-proficiency Spanish learners can process verbal morphology online. Sagarra (2007) investigated whether WM modulates sensitivity to adverb–verb tense conflicts among third-semester learners. Using an SPR task, she found that only high WM learners were sensitive to these conflicts. Thus, she concluded that third-semester Spanish learners do not process redundant verbal morphology when focused on meaning unless they have high WM. LaBrozzi (2009) and Sagarra and LaBrozzi (2018) found that classroom learners relied predominately on temporal adverbs to resolve tense conflicts, but that attention to verbal morphology was modulated by WM (though this was only found among the group of immersion learners).

3. The Present Study

Despite growing research on morphological processing, relatively few studies have examined the effects of task-essential training on learners’ online processing behaviors as the input unfolds in real time. Those that do either do not focus on forms related to lexical preference, or else focus on training that involves practice in the L1 (i.e., McManus and Marsden 2017, 2018). Further, though both Input Processing (i.e., the Availability of Resources Principle) and usage-based accounts of language learning predict that cognitive resources affect language processing, few studies have investigated whether individual differences in WM modulate the effects of processing-based training, such as PI. Indeed, those that have used multiple methodological approaches and different types of training, which have led to conflicting results. Moreover, these studies have focused on either learning outcomes (measured using offline tasks), or on attentional allocation (measured with eye tracking) within the training itself (Indrarathne and Kormos 2018; Issa 2019). Thus, the research to date has not addressed whether task-essential training pushes learners to create form–meaning connections that are later used to process sentences in real time, including an investigation of whether WM modulates these effects.

The present study addresses this gap through an experiment that investigates the online and offline effects of a multisession task-essential training among learners with varying WM capacity. Before and after training, participants completed an offline aural interpretation measure and a self-paced reading (SPR) task to measure learning gains. These results were also analyzed in relation to the learners’ performance on a WM task. The research questions for this study were:

RQ1: To what extent does task-essential training influence the degree to which learners accurately interpret verbal morphology for temporal and subject reference, as measured by an offline aural interpretation task?

RQ2: To what extent does task-essential training promote the use of verbal morphology for interpretation of temporal and subject reference, as measured by an online self-paced reading (SPR) task?

RQ3: To what extent does the accurate interpretation and online use of verbal morphology for temporal and subject reference vary with respect to learners’ working memory capacity?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

The initial participant pool consisted of 122 second-semester Spanish students at a large university in the US. Participants were recruited from a computer-enhanced Spanish course, where each student used the same textbook and curriculum.

Data were analyzed only from learners who completed all of the tasks in this study. In addition, participants had to be native speakers of English who began learning Spanish post-puberty, had never spent time in a Spanish-speaking country, and had 2 years or fewer of formal instruction in another language. All participants demonstrated that they (a) had sufficient knowledge of the target vocabulary (i.e., scored above 80% on a pretraining vocabulary test), (b) had minimal knowledge of the future tense (i.e., scored below 40% for this form on a written production task used for screening purposes), and (c) were sufficiently able to complete the SPR task (i.e., scored above 70% on comprehension questions for the experimental items in this task). Several participants were excluded from analyses due to technological error, failure to complete a task, or failure to follow instructions. After all exclusions, 91 participants were included in the final analyses.

Prior to completing any part of this study, participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups. After exclusions, there were 40 participants in the control group, 24 in the yes–no feedback group, and the 27 in the metalinguistic feedback group. Two tests of grammatical knowledge (see below) confirmed comparable proficiency between groups. One-way ANOVAs revealed no significant between-group differences (all p > 0.100).

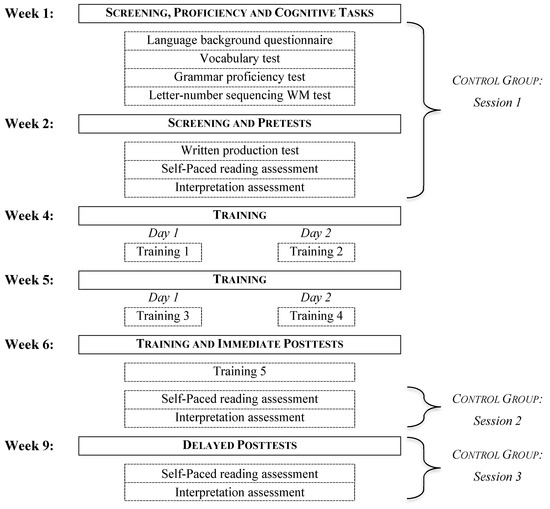

4.2. Experimental Design

This study was administered in computer laboratories over nine weeks. As seen in Figure 1, in the first two weeks of this study, all participants completed the language background questionnaire, vocabulary test, grammar proficiency test, written production task, and WM test (a letter-number sequencing test), followed by the pretest SPR and interpretation assessments. The training groups then completed five 20 min training sessions over the next 2.5 weeks (with 48–72 h between sessions). Following the training sessions, all participants completed the posttest SPR and interpretation assessments. Three weeks later, they completed the delayed posttest SPR and interpretation assessments.

Figure 1.

Experimental Design.

All participants continued normal instruction between pre- and posttests. While they received no explicit instruction on the target forms in their classes during the course of this study, the target forms are frequent in Spanish and participants would have been exposed to them in their classes.

4.3. Materials

4.3.1. Background Screening and Proficiency Measures

The language background questionnaire contained multiple-choice and open-ended questions addressing the participants’ previous Spanish instruction, their experience with Spanish outside the classroom, and their exposure to other languages. This information was used to make exclusions as described in the Participants section.

The vocabulary test was administered via computer. Participants matched the 18 target Spanish verbs and nine adverbial expressions used in the experimental tasks with their English equivalents. While the vocabulary was selected from the textbook chapters used in the participants’ classes, this ensured that participants knew the target vocabulary and decreased the likelihood that unfamiliarity with the stimuli influenced the results.

Two tests of grammatical knowledge were administered prior to training: (1) a multiple-choice grammar proficiency test, and (2) a written production test of verb forms. These tests were used in addition to strict enrollment criteria to ensure homogeneity within and between the learner groups. The grammar proficiency test was adapted from proficiency tests offered by Transparent Language and Spanish Steps, two reputable companies that provide language-learning software and resources. The test involved 24 multiple-choice questions covering many grammatical forms and structures of varying difficulty.

The written production test was a 12-sentence fill-in-the-blank test (4 sentences per tense: present, preterite, future) eliciting production of the verbs used in the training (described below). Participants typed the correct verb form for a given infinitive verb according to the subject provided.

Table 2 presents the group means for the background screening and proficiency measures. One-way ANOVAs confirmed that there were no significant differences between the groups on any of these measures (all p > 0.10).

Table 2.

Means (SDs in Parentheses) for the Background Screening and Proficiency Measures, and the WM Test.

4.3.2. Working Memory Task

The WM task was a letter-number sequencing (LNS) test adapted from the WM test in the Wechsler (1997, 2008) Adult Intelligence Scale and administered in E-Prime. A similar computerized version of LNS has been used in other recent L2 acquisition studies assessing WM (Grant et al. 2015; Legault et al. 2019). Strings of alternating letters and numbers were presented aurally at a rate of approximately one item per second. After listening to each string, the participants were instructed to place the numbers in ascending numerical order and then place the letters in alphabetical order. Given the need to both store and reorder the alphanumeric characters (processing) this task is considered a complex span task (e.g., Mielicki et al. 2018; Shelton et al. 2009)4. Participants could take as much time as they needed for recall. The task began with a series of two-item strings (e.g., C-6) and increased to eight items (e.g., 5-X-9-N-3-R-6-C). Participants heard three letter-number strings at each of the seven series lengths; thus, their overall accuracy was scored out of 21 maximum possible points. The Mean score for each group is presented in Table 2. One-way ANOVAs confirmed no significant between-group differences [F(2, 88) = 1.23, p = 0.298].

4.3.3. Task-Essential Training

The task-essential training in this experiment was a modified form of SI designed to help learners overcome lexical-preference and improve processing of verbal morphology in sentential context. The target forms were verbal inflections for tense and person-number. In the training (and the assessments), 18 target verbs (9 regular –ar verbs and 9 regular –er/–ir verbs) were used in all three tenses, and in four of the six person/number combinations: first-singular (1sg), first-plural (1pl), third-singular (3sg), and third-plural (3pl). When this study began, participants had been taught both present and past (preterite) tenses in their Spanish classes. The future tense was a novel tense that had not yet been taught.

Training was administered over 5 sessions (2.5 weeks) and consisted of computer-guided activities that participants completed individually using E-Prime 2.0 (Schneider et al. 2012). Each training session consisted of 102 sentences and took 17–20 minutes to complete. The sentences consisted of a prepositional phrase (either in sentence-initial or sentence-final position), a verb, and a direct object. Importantly, the sentences omitted adverbial expressions and explicit subject (pro)nouns, thus pushing learners to process verbal inflections for temporal and subject reference. See the examples in (1) and (2).

| (1) | Escucho | las | instrucciones | de | la | profesora. |

| listen.prs.1sg | the | instructions | from | the | professor. | |

| I listen to the instructions from the professor. | ||||||

| (2) | Antes | del | partido | comerán | espaguetis. | |

| Before | the | game | eat.fut.3pl | spaghetti. | ||

| Before the game they will eat spaghetti.’ | ||||||

During each training, the first half of the stimuli (51 sentences including practice) was presented in writing so that learners could first visualize the forms. The second half of the stimuli was then presented aurally using sentences recorded by a native Spanish-speaking female and edited for sound quality.

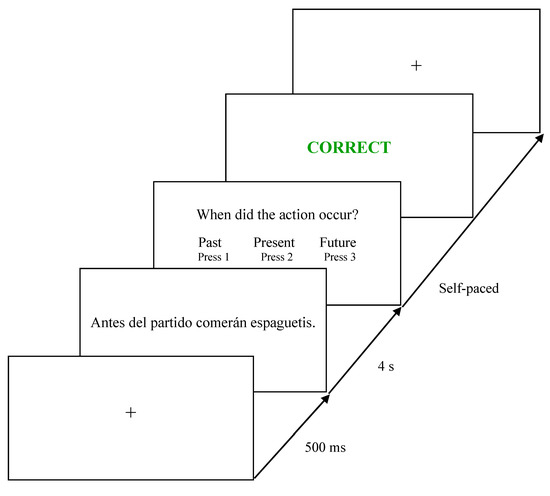

After hearing or reading the sentence, the participants were asked to determine either the tense or the subject and pressed a key to log their answer5. Sentences were randomized within each block (visual or aural), and participants did not know which question they would be asked. Visual sentences remained on screen for four seconds before participants saw the tense or subject question. Pilot testing determined this duration was sufficient for beginning learners to read each sentence only one time (see Bialystok and Miller 1999). Figure 2 illustrates an example visual trial.

Figure 2.

Example of a Training Visual Trial with a Tense Question.

While the training followed the theoretical framework for PI, and the above procedure adheres to guidelines for developing SI activities (see Wong 2004), it also deviated from SI activities as traditionally implemented. First, training progressively exposed the participants to the target forms across the five sessions. In training 1, participants only saw the 3sg form of the present, preterite, and future tenses. Trainings 2 and 3 contained both the 1sg and 3sg forms of all three tenses. The two plural forms (1pl and 3pl) were added in trainings 4 and 5. The sentences were balanced for tense, person, and number (only tense in training 1). This progressive exposure allowed learners to practice the known tenses (present and preterite), while limiting the number of new forms (future tense) that they were exposed to in each session. While this departs from Wong (2004) prescription that training should present one thing (i.e., one form-function mapping) at a time, it follows recent speculation within the PI literature that progressive exposure would help learners build up paradigms over time (see Culman et al. 2009; Henry et al. 2017).

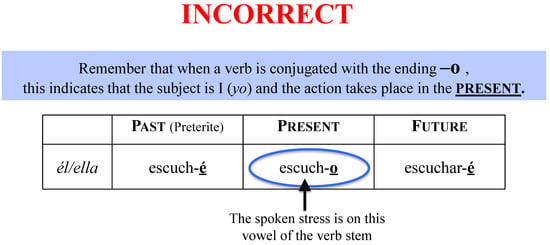

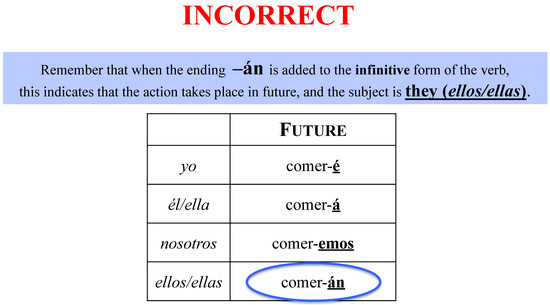

Secondly, none of the participants received explicit metalinguistic information prior to training, and they did not receive explicit information about the processing problem (the Lexical Preference Principle). Instead, participants received two different types of feedback6: the yes–no feedback group saw either correct or incorrect after each response as is typical for SI activities; the metalinguistic feedback group saw correct or incorrect and—after an incorrect answer—also received a metalinguistic explanation of the form (Figure 3 and Figure 4), including phonological information (e.g., stress). This type of metalinguisitc feedback has been used in some PI studies (e.g., Sanz 2004; Sanz and Morgan-Short 2004), but is more common in other studies on task-essential training (e.g., Filgueras-Gomez 2016). The primary goal of this study is not to investigate the role of feedback in training differences, but these groups were included as part of a larger project, part of which does investigate the role of feedback (Dracos and Henry 2018). Given the potential differences between groups on the tasks examined in the present study, it was not appropriate to collapse these groups into a single “training group” prior to analyses showing that they behaved similarly before and after training. The input practice was the same across all participants who underwent training.

Figure 3.

Example of Metalinguistic Feedback Following a Tense Question during Aural Training Practice.

Figure 4.

Example of Metalinguistic Feedback Following a Subject Question during Visual Training Practice.

4.3.4. Interpretation Assessment

Like the aural training, the interpretation assessment (also administered via E-Prime) included sentences without lexical cues, and participants indicated the subject and temporal reference of the sentence. The only procedural differences with the aural training were that participants indicated both the subject and tense of every sentence, and no feedback was provided. Participants heard three practice items followed by 12 sentences, using each target tense (preterite, future) and distractor tense (present) four times, and each subject (1SG, 1PL, 3SG, 3PL) three times. Each of the four subjects was presented once in each tense. Participants did not hear any of the same sentences in the interpretation assessment and training.

To avoid practice effects, three versions (A, B, C) of this assessment were created. The target verbs, conditions, and overall procedure were identical in all versions of each assessment, but the sentence stimuli were unique. Participants were randomly assigned one of six possible test orderings (ABC, BCA, etc.).

4.3.5. Self-Paced Reading Assessment

The SPR assessment was administered via E-prime 2.0 using word-by-word presentation in a non-centered, noncumulative moving-window format. Before the start of each trial, a cue symbol “+” appeared at the location of the start of the next sentence. The words of the trial sentence were initially masked with dashes, but spaces and punctuation were visible. After reading the entire sentence, participants saw two pictures on a separate display screen and chose which accurately depicted the meaning of the sentence.

The SPR stimuli consisted of three 76-item sets, one of which was randomly presented to each participant. As in the interpretation assessment, three versions of the task were administered to participants at different test times to minimize practice effects. Each stimulus set included 4 practice trials, 36 experimental sentences, and 36 filler sentences. Half of all the sentences were grammatical, and the other half was ungrammatical. Table 3 presents examples of sentences from the three experimental conditions. The full list of experimental sentences used in the three versions of the task are provided in the Supplementary materials (S1).

Table 3.

Examples of Experimental Sentences for the Self-Paced Reading Assessment.

Each experimental sentence followed the same syntactic structure and contained exactly 10 words. Verb tense (preterite vs. future) was matched across conditions, and each of the 18 target verbs was used once in each tense. The filler sentences also included familiar, non-target vocabulary from the textbook and were similar in length (7 to 11 words). The fillers involved processing of distinct syntactic structures (subject and object relative clauses, long-distance gender agreement, and clitic pronouns). Sentences were presented randomly to avoid order effects.

A comprehension measure was included following every sentence to increase the likelihood that participants focused on meaning (Keating and Jegerski 2015). Pictures were used instead of comprehension questions to avoid drawing learners’ attention to temporal reference and S–V agreement. Pictures were professional clip-art drawings that were matched in size and style. To force participants to attend to all aspects of the sentences, the pictures assessed comprehension of the prepositional phrase (location), the verb (action), and the direct object in equal proportion. Figure 5 illustrates the choice between two pictures for the experimental sentence El año pasado ella recibió el diploma en la ceremonia. ‘Last year she received the diploma at the ceremony.’

Figure 5.

Example of the Picture-Based Comprehension Measure in the Self-Paced Reading Task.

5. Results for Interpretation Assessment

5.1. Data Scoring and Statistical Analyses

Accuracy scores on the interpretation assessment were broken down by verb tense and task (i.e., whether participants interpreted the verbal inflection for tense or subject reference), resulting in four conditions: Tense-Preterite, Tense-Future, Subject-Preterite, Subject-Future. Statistical analyses for each of the four conditions were carried out using generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) with a logit-link and binomial error distribution using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (with graphs outputted by Stata/SE version 15.1). These analyses were selected because, unlike analyses of variance, mixed-effects analyses model relationships between observations and avoid violating the assumption of independence. This is particularly important given that participants contributed multiple samples in the data set (i.e., repeated testing over time). The models additionally avoid violations of normality, and include robustness against homoscedasticity and sphericity (see McManus and Marsden 2019). These advantages render mixed-effects analyses ideal for our analyses.

Analyses for each condition in the interpretation assessment began with models including the fixed effects of Time, Group, WM, and interactions for Time × Group, Group × WM, and Time × WM. Predictors were subsequently dropped from the model based on improvements in Akaike’s and Schwarz’s Bayesian information criteria (AIC/BIC) estimations7. For each condition, we report only the best-fit model; factors not included in the best-fit model were non-significant at p > 0.100 in other models. Participants was included as the random factor in all models. For the purposes of interpretation, WM was centered at its mean (M = 12.8) for all models.

5.2. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics for each condition are presented by group and test time (pretest, posttest, delayed posttest) in Table 4.

Table 4.

Means (SDs in Parentheses) for Interpretation Assessment.

5.3. Model Results

The fixed coefficients for the best-fit model for each condition are reported in Table 5. Main effects and pairwise comparisons for each condition are reported in Table 6 and Table 7 respectively. The results of the logit mixed-effects analyses are summarized by condition in the following sections.

Table 5.

Fixed Coefficients from Logit Mixed-Effects Models—Accuracy on the Interpretation Assessment.

Table 6.

Summary of Significant Main Effects in Interpretation Assessment Models.

Table 7.

Pairwise Comparisons for Time × Group Interactions in Interpretation Assessment Models.

5.3.1. Tense-Preterite Condition

The best-fit model for the Tense-Preterite condition contained the fixed-effect predictors of Group, Time, and WM and the random factor Participants (Table 5)8 but the control group was less accurate than the metalinguistic and the yes–no feedback groups (Table 5). The main effect of WM was significant, with higher WM related to higher accuracy overall. Across all the groups and at all test times, the odds of interpreting the preterite tense correctly increased by 6% for every one unit increase in WM score.

5.3.2. Tense-Future Condition

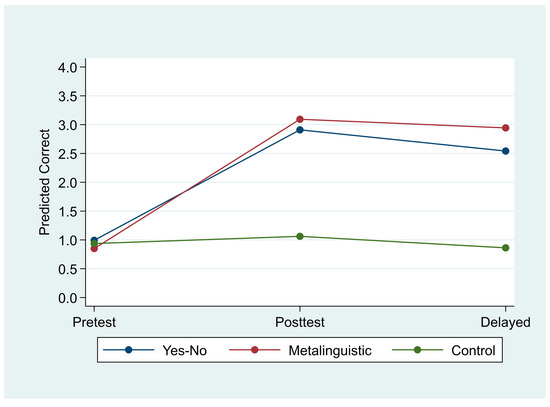

The best-fit model for the Tense-Future condition contained the fixed-effect predictors of Group, Time, WM, and Group × Time and Group × WM interactions and the random factor Participants (Table 5). The main effects of Group and Time were significant, as was the Time × Group interaction (Table 6). Pairwise comparisons for the Group × Time interaction revealed no differences between the groups on the pretest and no differences between the two training groups on either posttest. On the immediate posttest and delayed posttest, both the metalinguistic feedback and the yes–no feedback groups were more accurate than the control group (see Table 7 and Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Predicted Probability of Accurate Interpretation in the Tense-Future Condition by Group and Time.

The main effect of WM was also significant, as was the Group × WM interaction (Table 6). These effects arose because higher WM was associated with higher accuracy regardless of test time, but there were differences between the groups overall. For the control group, as WM increased by 1 unit, the odds of interpreting future tense correctly increased by 36%. For the yes–no feedback group, the odds increased by 7%, while the odds decreased by 3% for the Metalinguistic group (see Table 5 for the odds-ratios and other estimated parameters). Thus, WM ability had a greater impact for the control group than it did for the two training groups in the Tense-Future condition.

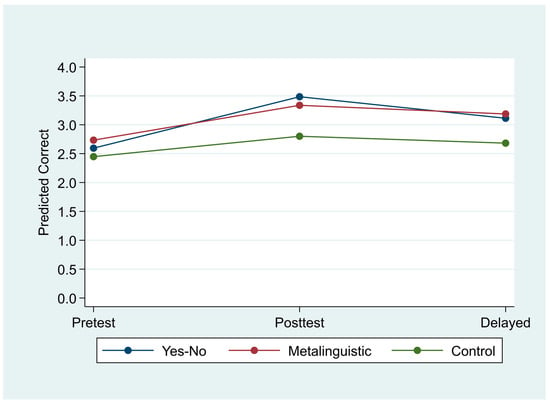

5.3.3. Subject-Preterite Condition

The best-fit model for the Subject-Preterite condition contained the fixed-effect predictors of Group, Time, and WM as well as Group × WM and Time × WM interactions and the random factor Participants (Table 5). There was a significant main effect for Group and Time and a marginally significant Group × Time interaction (Table 6). Pairwise comparisons for the Group × Time interaction showed no differences between the two training groups, but the control group was less accurate than both the metalinguistic and the yes–no feedback groups on the posttest and delayed posttest (see Table 7 and Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Predicted Probability of Accurate Interpretation in the Subject-Preterite Condition by Group and Time.

There was a main effect of WM, as well as a Time × WM interaction (Table 6). One unit increase in WM showed an increase in the odds of correctly interpreting the subject at all three test times. The interaction arose because the odds increased from 2% on the pretest to 10% on the posttest and 26% on the delayed posttest (see Table 5). However, this effect was only significant on the delayed posttest. Thus, for the Subject-Preterite condition, WM had the greatest impact, regardless of group, on the delayed posttest.

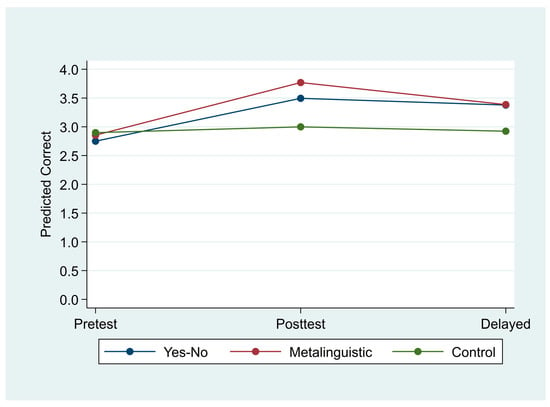

5.3.4. Subject-Future Condition

Descriptive statistics are presented by group in Figure 9. The best-fit model for the Subject-Future condition contained the fixed-effect predictors of Group, Time, WM, and the Group × Time and Group × WM interactions and the random factor Participants (Table 5). The main effect of Group was statistically significant, as was the main effect of Time, and the Group × Time interaction (Table 6). Pairwise comparisons for the Group × Time interaction (Table 7) revealed no significant differences between any of the groups on the pretest. There were also no differences between the two training groups on either posttest; however, both the metalinguistic and yes–no feedback groups were more accurate than the control group on the immediate and delayed posttests (see Table 7 and Figure 8). In addition, there was a main effect of WM (Table 6), indicating that higher WM was associated with higher accuracy overall, regardless of test time and group. Across all the groups and at all test times, for every one unit increase in WM, the odds of interpreting the subject correctly in the future tense increased by 18%.

Figure 8.

Predicted Probability of Accurate Interpretation in the Subject-Future Condition by Group and Time.

6. Results for Self-Paced Reading Assessment

6.1. Data Scoring and Statistical Analyses

6.1.1. Accuracy

Accuracy scores on the picture comprehension measure were computed for each participant as the percentage of accurate responses on experimental trials (36 items) during the SPR task at each test time. One-way ANOVAs for group were conducted at each test time.

6.1.2. Reading Times (RTs)

Prior to statistical analysis, all data were trimmed to remove outlier RTs that were either physically impossible (i.e., too short) or indicated that learners were not reading the sentence for meaning. These trimming procedures were consistent with guidelines laid out by Keating and Jegerski (2015) and began by excluding RTs that were less than 150 milliseconds or exceeded 4000 milliseconds. In addition, we conducted a within-subject trim, which excluded reading times exceeding +/–2 standard deviations from the participant’s mean RT for each region in each condition. These trimming procedures resulted in a loss of 6.1% of the data. After trimming, the raw RTs for each condition were transformed into difference scores by subtracting the RTs for the agree sentences from RTs for the violation sentences, resulting in four difference score outcomes referred to as follows: (1) AdvV-Preterite, (2) AdvV-Future, (3) SV-Preterite, and (4) SV-Future. For example, the AdvV-Preterite difference score was computed by subtracting the RT for Agreement-Preterite sentences from the RT for AdvV-Preterite Violation sentences. A positive difference score therefore represents higher RTs for violation sentences. These data were analyzed using mixed-effects linear regression analyses (using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25, graphs outputted by Stata/SE version 15.1), with the outcome as the difference scores at the critical region (the verb). WM was centered at its mean (M = 12.8) for all models run. As with the logit mixed-effects models for the interpretation assessment, these mixed-effects linear analyses account for non-normal data distributions and guard against violations of homoscedasticity and sphericity.

6.2. Accuracy

Mean accuracy scores for all three groups on the comprehension measure at all three test times were between 85% and 91%. The one-way ANOVAs revealed that there were no between-group differences on the comprehension measure at any test time (pretest: F2,88 = 1.23, p = 0.297; posttest: F2,88 = 0.329, p = 0.721; delayed: F2,88 = 0.941, p = 0.394).

6.3. Reading Times

6.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 8 presents mean RTs by group and condition for the verb (critical Region 5), which determined whether there was a subject–verb (SV) agreement violation or an adverb–verb (AdvV) tense violation. RTs for the pre-critical Region 4 and the two post-critical Regions 6 and 7 can be found in Tables S1–S3 in Supplemental Materials. Since there were no significant differences in RTs for the pre- and post-critical regions, they will not be discussed.

Table 8.

Trimmed Mean Reading Times (RTs) (SDs) for Critical Region (Verb).

6.3.2. Model Results

For each of the four difference score outcomes, the mixed-effects linear regression analyses addressing the effects of training included participants as the random factor and had the fixed effects of Time, Group, and the Time × Group interaction (as well as all possible simplified models including two or one of these predictors). There were no significant main effects or interactions (all p > 0.10) for any of the models run.

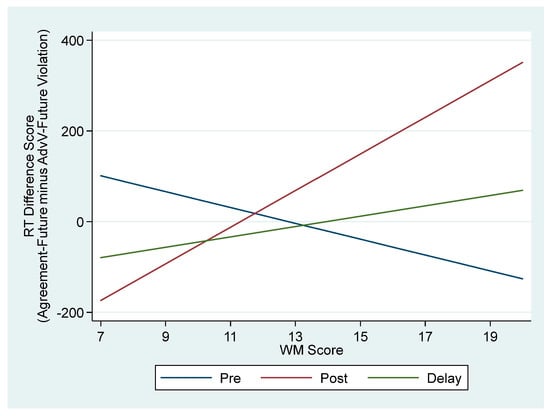

Given that both the SPR analyses and the Interpretation task analyses revealed no significant differences between the two training groups, these two groups were combined for the mixed-effects linear models addressing the effects of WM. These models included participants as the random factor and had the fixed effects of Time, Group (Training vs. Control), WM (LNS scores as a continuous variable), and their interactions for each of the four difference score outcomes. The best-fit models included only the fixed effects of Time and WM (and not Group or its interactions). There was a main effect of WM that approached significance for two outcomes: AdvV-Preterite (F1,273 = 2.97, p = 0.086) and SV-Preterite (F1,273 = 3.10, p = 0.079). In both cases, the model revealed a positive association between WM and difference scores, indicating that participants with higher WM spent more time on violation conditions regardless of training or test time.

Research question 3 specifically addressed how WM influences the effects of training. Given that results from the control group could limit the interpretability of the results with reference to this question—particularly because the control group had consistently lower scores on the interpretation task and did not demonstrate development of form–meaning connections—we conducted additional analyses excluding the control group. For each of the four difference score outcomes, we ran linear mixed models that included training participants as the random factor and had the fixed effects of Time, WM, and the Time × WM interaction. Results revealed significant effects only for the AdvV-Future difference score outcome. There were no main effects for Time or WM, but there was a significant Time × WM interaction (F2,102 = 4.06, p = 0.020). As seen in Figure 9, the association between WM score and RT difference scores is slightly negative on the pretest, but positive for the posttest and delayed posttest, indicating that higher WM led to increased RTs when there was a tense violation. Indeed, there was a significant difference between the association at pretest and posttest (p = 0.005). On the delayed posttest, the association is reduced, and the slope is neither significantly different from the slope at pretest nor posttest. The estimated parameters for this model (AdvV-Future outcome), as well as the one for SV-Future, are presented in Table 9.

Figure 9.

Time × Working Memory Interaction (AdvV-Future Outcome) for Training Participants, Indicating the Predicted Reading Time Difference Scores at Each Test Time Based on WM Score.

Table 9.

Output for SV-Future and AdvV-Future Reading Time Difference Score Outcomes from Linear Mixed-Effects Models Including Only Training Participants and Fixed Effects of Time, WM, and Time × WM Interaction.

For the other three outcomes (AdvV-Preterite, SV-Preterite, and SV-Future), none of the predictors reached significance. However, the best-fit model for the SV-Future outcome (including only the fixed effects of Time and WM, but not the interaction) revealed a marginally significant difference between the pretest and the posttest (p = 0.074). Specifically, with WM centered at its mean of 12.8 (i.e., for someone with average WM who underwent training), participants tended to spend more time on the future-tensed verb when there was an SV agreement violation on the posttest (but not on the pretest).

7. Discussion

The primary goal of the present study was to determine the effects of training and the role of WM in the interpretation and processing of verbal morphology for temporal and subject reference. The following sections discuss the results in relation to the research questions.

7.1. RQ1: Offline Interpretation

The first research question asked how training affects the ability to interpret verbal morphology for temporal and subject reference in an offline aural interpretation task. There were robust effects of training for both tense and subject interpretation in the future tense, showing that the metalinguistic and yes–no feedback groups were significantly more accurate than the control group on both the posttest and the delayed posttest. The increase in accuracy was particularly dramatic for tense information. Descriptive results point to similar effects of training for sentences in the preterite tense, though statistical analyses did not yield significant Group × Time interactions for either tense or subject interpretation. However, this does not necessarily mean that the training groups did not improve. Rather, the lack of a statistical advantage for the training groups in the preterite tense appears to stem from slightly higher pretest scores for the training groups and moderate gains for the control group. This is expected given that all learners were exposed to the preterite in their classwork prior to, and during, the course of the experiment.

Taken together, these results support previous research showing that task-essential training leads learners to interpret verbal morphology accurately in controlled, offline tasks, (Benati 2001; Cadierno 1995; Filgueras-Gomez 2016; Lee and Benati 2007; Marsden and Chen 2011). In line with this research, we interpret these results to mean that training promoted the development of form–meaning connections, which could potentially be deployed in less controlled tasks. Further, while it is evident that participants made the greatest gains in the novel future tense, the apparent improvement in the preterite tense may suggest that training could both aid the learning of new form–meaning mappings, and also help create more robust form–meaning mappings for familiar forms. Crucially, the results for RQ1 suggest that learners who underwent training were able to process these forms offline.

7.2. RQ2: Online Processing

The second research question asked whether training promoted the processing of verbal morphology in an online SPR assessment. Responses to the SPR comprehension questions indicated that participants comprehended the sentences accurately. However, the analyses of RTs showed that neither the training groups nor the control group had higher RTs on violation sentences, as would be expected if they had processed verbal morphology during reading. Thus, although task-essential training promoted the development of form–meaning connections (RQ1), it did not appear to affect online processing of redundant verbal inflections. This dichotomy could indicate that, although training facilitated the initial linking of form and meaning, it was not strong enough to help the learners develop automaticity and overcome online processing challenges that could stem from lower proficiency (e.g., Sagarra and Herschensohn 2010, 2011), lack of cognitive resources (e.g., McDonald 2006), insufficient experience processing these grammatical cues (e.g., Ellis 2015), or the complex nature of the SPR task (e.g., Keating and Jegerski 2015). Additionally, it could indicate that learners were able to deploy additional resources during the offline, but not the online, tasks, for example consciously utilizing explicit information (see, e.g., Ellis 2015; Keating and Jegerski 2015). We note, however, that the metalinguistic group did not outperform the yes–no group in the offline task, suggesting that the use of explicit information did not play a significant role in the results of the offline task. In addition, it is important to reiterate that the offline interpretation assessment was aural and each sentence only played once. Therefore, in order to use explicit information, learners would have had to access it while simultaneously processing the sentence or else maintain the target form in WM long enough to use explicit information after hearing the stimulus. Thus, it is perhaps more likely that the difference in focus/task goals between the offline Interpretation task and the online SPR task could have contributed to some degree to the different behavior from participants. While the interpretation assessment asked participants to determine the tense and subject and therefore pushed attention to the verbal inflections (the only cue available), the SPR comprehension questions assessed whether learners understood other elements of the sentence (the verb meaning, a direct object, or locative phrase). Task-essential training therefore seems to have pushed these learners to enter an intermediate stage, wherein they can accurately process verbal morphology (make form–meaning connections) when they are explicitly pushed to do so, but their implicit linguistic system cannot yet make use of these form–meaning connections online.

While the results of the present study differ from those of a few recent studies that have investigated the effects of training on online processing (e.g., Issa and Morgan-Short 2019; Lee and Doherty 2018; Wong and Ito 2018), they are in line with others (e.g., McManus and Marsden 2017, 2018). Aside from the issues raised in the last paragraph, we speculate that the lack of training effects in our study could stem from a combination of three factors: the target form, the training, and the methodology. First, the target form, verbal morphology, is especially difficult to acquire, particularly for L1 speakers of English, which has weaker morphology than many other languages (see Sagarra and Ellis 2013). While previous research has shown that task-essential training increases attention to verbal morphology under controlled circumstances (e.g., Benati 2005; Cadierno 1995; Dracos and Henry 2018), learners may be more likely to use lexically-based processing strategies when focused on processing for meaning. Further, most other studies on the effects of training on online processing have used forms related to grammatical role assignment and the first noun principle. Only McManus and Marsden (2017, 2018) have demonstrated positive effects of training with verbal morphology. Yet, it is noteworthy that the training used in these studies was quite different from that of the present study. While the present study utilized multisession training that focused on multiple forms, McManus and Marsden focused on only one form. Further, the positive effects of training that McManus and Marsden report were limited to groups who received explicit information about and practice with a similar L1 form. The participants in their studies who received task-essential training only in the L2 (similarly to the present study) also showed no effects of training. Finally, we note that no study employing an SPR task has found robust effects of training. This lack of effect could stem from (a) less sensitivity in SPR tasks (i.e., SPR tasks cannot measure second-pass reading times or regressions), or (b) the fact that SPR tasks tend to be quite different from the training tasks, whereas eye-tracking assessments largely mirror training (e.g., Wong and Ito 2018). To this latter point, we add that studies with eye-tracking tasks often evaluate online processing during training, while those using SPR tasks test sensitivity to forms after training, and thus focus on different aspects of language processing. These differences may be important factors to consider in future research.

7.3. RQ 3: The Role of WM

The third research question asked how WM affected the use of verbal morphology for temporal and subject reference. In the offline aural interpretation assessments, results showed that higher WM was associated with higher accuracy. While the effects of WM differed across groups in one condition (the Tense-Future condition) and across test times in another condition (the Subject-Preterite condition), there was no Group × Time × WM interaction for any of the four conditions. That is, higher WM did not lead to greater gains from training, nor did training erase effects of WM. This finding indicates that high and low WM learners benefit equally from training and contrasts with studies which show that WM affects the outcome of training under some conditions (Indrarathne and Kormos 2018; Santamaria and Sunderman 2015; Sanz et al. 2016; Villegas and Morgan-Short 2019). However, there were substantial differences between these studies and the present study that may account for the disparity in findings, such as the proficiency of the participants tested (low-intermediate vs. absolute beginners), timing of explicit information (as feedback vs. prior to training), type of instruction (implicit vs. explicit), length of training, differences in task demands, target structures, working memory measures, and statistical analyses. This makes comparison between studies difficult and highlights the need for a more systematic approach to understanding the involvement of WM in training. Nonetheless, our results do reveal a general role for WM in L2 morphological processing and thus support accounts of L2 processing that assume a limited-resource processor (e.g., Ellis and Sagarra 2010a, 2010b; VanPatten 2015a) and emphasize the lack of computational resources among L2 learners (e.g., McDonald 2006).

The SPR analyses also revealed some effects for WM, which varied between the four conditions. When all of the participants were included in analyses, higher WM was marginally associated with higher RTs on both SV and tense violations in the preterite, but there were no differences between groups. Thus, WM played a role in online processing, but only in the preterite condition, which was the only form which all of the participants—including the control group—were familiar with and would have been able to process. As noted previously, learners had some exposure to the preterite forms during their language classes (i.e., between training sessions), and so it is difficult to know whether this may have influenced these results.

When the training groups were isolated in the SPR analyses, WM did relate to RTs on tense violations in the future tense. Critically, after training, those with high WM scores were more sensitive to violations in this condition. Note also that, in the immediate posttests, participants with at least average WM scores were marginally more sensitive to SV violations in the future tense. It seems, therefore, that training had an effect on online processing, but only among learners with a certain level of WM. These findings are consistent with Indrarathne and Kormos (2018), who found that high WM learners process forms more deeply during training, but comparisons must be made with extreme caution because (a) the effects of WM were not consistent across training groups or conditions in either study, (b) the trainings were different, and (c) the present study focused on online processing post-training, whereas Indrarathne and Kormos focused on attentional allocation during training. We suggest future research examine the role of WM in attentional allocation during training, and on online processing following treatment.

The overall results suggest a general role for WM in creating form–meaning connections and processing forms online and also point to a role for task-essential training, which helps learners build familiarity and experience with a form. Specifically, regardless of learners’ WM capacities, the results show that training can provide learners with an opportunity to process forms regularly and build robust form–meaning connections. In other words, training helps learners overcome some of the challenges posed by limitations on the processor by increasing the salience of redundant grammatical forms and promoting purposeful processing of these forms (see, e.g., Ellis 2015; Henry et al. 2017). Knowledge gained during training may later be used to process verbal morphology online when the learner has the cognitive resources to do so. As more exposure and practice with a form should reduce the cognitive resources needed to process it, this sort of training may be even more important for forms that are cognitively taxing, such as verbal morphology (see also Sagarra and LaBrozzi 2018).

Taken together, the present study contributes to the small body of research showing that WM plays an important role in the processing of online verbal morphology (e.g., Sagarra 2007; Sagarra and LaBrozzi 2018), but that other factors, such as experience processing a linguistic form may modulate its effects. More broadly, these findings corroborate the recent studies demonstrating effects of WM for online morphosyntactic processing among low proficiency learners (e.g., Faretta-Stutenberg 2014; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2010), as well as online research suggesting WM may be predictive of how much attention L2 learners allocate to target forms during training (Indrarathne and Kormos 2018; cf. Issa 2019). Given that this is the first study to explore how WM affects the outcome of task-essential training using online measures, we suggest that future research explore this issue further.

8. Conclusions

The offline task in the present study demonstrated that the multisession task-essential training promoted the development of form–meaning connections for verbal morphology in L2 Spanish. While participants did not appear to process verbal morphology online after training, having established form–meaning connections is likely a pre-requisite to doing so; thus, results suggest that training is valuable, even if it does not result in immediately observable effects in online processing among lower-proficiency learners. Further, although WM was positively associated with both offline interpretation and online processing, it did not affect learning outcomes or modulate the effects of training. Taken together, then, the present study suggests that task-essential training provides valuable practice with these forms, which can benefit all learners, and thus task-essential training could be a valuable addition to L2 classrooms.

Methodologically, this study also highlights the need for more systematic investigations into task-essential training and its effects for online processing, particularly for verbal morphology, which has been understudied. This is especially important given that previous research on sentence processing, task-essential training, and WM has shown that the linguistic forms under investigation and the methodologies used significantly impact results. Future research should therefore work to detail both aspects of task-essential training (e.g., targeted form, length, type of explicit information) and individual differences, such as WM, that impact online processing and sensitivity to targeted forms post-training.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2226-471X/6/1/24/s1, Table S1: Trimmed mean Reading Rimes (RTs) for the precritical region (word 4), Table S2: Trimmed mean Reading Times (RTs) for the postcritical region (word 6), Table S3: Trimmed mean Reading Times (RTs) for the second spillover region (word 7), and Appendix S1: Stimuli from Training and Assessment measures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and N.H.; methodology, M.D.; data collection, M.D.; formal analysis, M.D. and N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D. and N.H.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and N.H. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by a Baylor University Research Committee (URC) small-range grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Pennsylvania State University (IRB#: 36083).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be made available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available in accordance with the informed consent guidelines provided to the participants.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our participants for their time, Michele DeMuth for her help with data collection, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback. Any remaining errors are ours alone.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baddeley, Alan. 2000. The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4: 417–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, Alan, and Graham Hitch. 1974. Working memory. In Recent Advances in Learning and Motivation. Edited by Graham Bower. New York: Academic Press, Vol. 8, pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Benati, Alessandro. 2001. A comparative study of the effects of processing instruction and output-based instruction on the acquisition of the Italian future tense. Language Teaching Research 5: 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, Alessandro. 2005. The effects of processing instruction, traditional instruction and meaning-output instruction on the acquisition of the English past simple tense. Language Teaching Research 9: 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen, and Barry Miller. 1999. The problem of age in second-language acquisition: Influences from language, structure, and task. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 2: 127–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brooks, Patricia J., Vera Kempe, and Ariel Sionov. 2006. The role of learner and input variables in learning inflectional morphology. Applied Psycholinguistics 27: 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadierno, Teresa. 1995. Formal instruction from a processing perspective: An investigation into the Spanish past tense. The Modern Language Journal 79: 179–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Robert D. 2011. Native and Nonnative Processing of Modality and Mood in Spanish. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida State University, Talahassee, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, Andrew, Chris Jarrold, Michael Kane, Akira Miyake, and John Towse, eds. 2008. Variation in Working Memory. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Culman, Hillah, Nick Henry, and Bill VanPatten. 2009. The role of explicit information in instructed SLA: An on-line study with Processing Instruction and German accusative case inflections. Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German 42: 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekydtspotter, Laurent, and Claire Renaud. 2014. On second language processing and grammatical development: The parser in second language acquisition. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 4: 131–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dracos, Melisa, and Nick Henry. 2018. The effects of task-essential training on L2 processing strategies and the development of Spanish verbal morphology. Foreign Language Annals 51: 344–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussias, Paola E., and Pilar Pinar. 2010. Effects of reading span and plausibility in the reanalysis of wh-gaps by Chinese-English second language speakers. Second Language Research 26: 443–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick C. 2015. Implicit and explicit learning: Their dynamic interface and complexity. In Implicit and Explicit Learning of Languages. Edited by Patrick Rebuschat. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Nick C., and Nuria Sagarra. 2010a. Learned attention effects in L2 temporal reference: The first hour and the next eight semesters. Language Learning 60: 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick C., and Nuria Sagarra. 2010b. The bounds of adult language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 32: 553–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Nick C., Kausar Hafeez, Katherine Martin, Lillian Chen, Julia Boland, and Nuria Sagarra. 2014. An eye-tracking study of learned attention in second language acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics 34: 547–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faretta-Stutenberg, Mandy. 2014. Individual Differences in Context: A Neurolinguistic Investigation of Working Memory and L2 Development. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Faretta-Stutenberg, Mandy, and Kara Morgan-Short. 2018. The interplay of individual differences and context of learning in behavioral and neurocognitive second language development. Second Language Research 34: 67–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueras-Gomez, Marisa. 2016. The effects of type of feedback, amount of feedback and task-essentialness in a L2 computer-assisted study. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fodor, Janet Dean. 1998. Parsing to learn. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 27: 339–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, Rebecca. 2011. Integrated knowledge of agreement in early and late English–Spanish bilinguals. Applied Psycholinguistics 32: 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, Leif M., and Irena O’Brien. 2008. Phonological memory and children’s second language grammar learning. Applied Psycholinguistics 29: 463–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Angela M., Shin Yi Fang, and Ping Li. 2015. Second language lexical development and cognitive control: A longitudinal fMRI study. Brain and Language 144: 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, Sara, Jessica G. Cox, Ellen J. Serafini, and Christina Sanz. 2015. The role of individual differences in the study Abroad context: Cognitive capacity and language development during short-term intensive language exposure. Modern Language Journal 99: 137–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, Michael, and Mark Sawyer. 1992. L2 working memory capacity and L2 reading skill. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 14: 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havik, Else, Leah Roberts, Roeland van Hout, Robert Schreuder, and Marco Haverkort. 2009. Processing Subject-Object Ambiguities in the L2: A Self-Paced Reading Study With German L2 Learners of Dutch. Language Learning 59: 73–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Nick. 2015. Morphosyntactic Processing, Cue Interaction, and the Effects of Instruction: An Investigation of Processing Instruction and the Acquisition of Case Markings in L2 German. Ph.D. Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Nick, Carrie N. Jackson, and Jack DiMidio. 2017. The role of prosody and explicit instruction in Processing Instruction. Modern Language Journal 101: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrarathne, Bimali, and Judit Kormos. 2018. The role of working memory in processing L2 input: Insights from eye-tracking. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 21: 355–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, Bernard I. 2019. Examining the relationships among attentional allocation, working memory, and second language development: An eye-tracking study. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Research in Classroom Learning. Edited by Ronald P. Leow. New York: Routledge, pp. 464–79. [Google Scholar]

- Issa, Bernard I., and Kara Morgan-Short. 2019. Effects of external and internal attentional manipulations on second language grammar development: An eye-tracking study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41: 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]