Abstract

This study investigated how the attitudes and expectations of heritage languages (HL) courses differ between Spanish and Korean. Spanish and Korean are two of the biggest heritage languages (HLs) taught across American universities, but represent different trends of HL in the US. Ninety-two adult heritage speakers (HSs) completed a 41-question online questionnaire on their perceived HL proficiency as well as on what aspects of HL courses should target and what activities would be more beneficial for them. The results showed that the two groups of HSs present different attitudes and expectations towards HL instruction. Spanish HSs value their HL classes as a way to prepare for professional success and expect to receive more explicit instruction in the classroom. On the other hand, Korean HSs favor cultural components and take HL courses as a tool for reconnection with their community and cultures.

1. Introduction

Spanish and Korean are two of the many widely spoken languages in the US (U.S. Census Bureau 2019). This is reflected in the high numbers of Korean and Spanish heritage speakers (HS), bilinguals who use a language at home that differs from the dominant language (Valdés 2001). According to the National Heritage Language Survey (Carreira and Kagan 2011), Spanish had the highest number of respondents, followed by Korean as the fourth highest number. This represents the growing number of HSs enrolling in heritage language (HL) courses offered at the academic level, specifically Spanish and Korean.

The study of both Spanish and Korean HSs is crucial, as both groups represent two different HL realities in the US. Spanish is a typologically similar language to English and has a significant demographic, social, and economic presence and proximity to the US. On the other hand, Korean is a typologically different language and has a lesser social influence and demographic presence in the US. Previous studies have shown that HSs across numerous heritage backgrounds in the US have positive attitudes towards their HL (Carreira and Kagan 2011; Cho 2000, 2015; Lee 2002) and the main motivation for HSs to enroll in HL courses is to learn more about their cultural and linguistic roots, followed by the need to communicate better with family and friends in the US (Carreira and Kagan 2011). Nonetheless, proficiency and experience in the HL were found to differ across languages.

2. Language Ideology, Motivation, and Attitudes towards the Heritage Language

HL learning is interconnected with socio-cultural dimensions, such as identities, attitudes, and motivations (Donitsa-Schmidt et al. 2004; He 2010; Lee and Suarez 2009; Mori and Calder 2015; Tse 2001). For instance, Tse (2001) analyzed retrospective data from 39 Asian-American HSs and found that HSs’ attitudes are a significant factor that affects the maintenance of their HL. According to Tse, language was a sign of group membership and the acceptance of the dominant culture relied on the fluency in the dominant language. Many participants expressed their desire to establish their American identity to themselves and others, since the association with the dominant language garners prestige. On the other hand, the use of the HL produced embarrassment and shame, which created negative attitudes towards their HL group. Furthermore, their negative feelings towards their HL affected their HL ability and motivation to maintain it. Similarly, Li (1994) conducted an ethnographic study on a Chinese community near Newcastle, UK. By examining 58 respondents from 10 participating families, Li notes that the respondents who established a greater understanding of the cultural values, ethics, and manners of the ethnic group were the ones who developed a higher level of proficiency in their HL. This is also noted by Lee (2002), who found that HSs who identified as bicultural (both from their heritage culture and the dominant culture) were the ones who showed the highest proficiency in their HL. On the same line, Lee and Suarez (2009) noted that ‘high bilingualism’ (as opposite to monolingualism) provides identity development, higher self-esteem, confidence, harmonious family relationships, and active participation in both cultures.

The motivation for HL learning and maintenance is also connected with the histories and life situations of individual learners. Although HLs are an invaluable resource for preservation and HL courses should reflect the cultural, linguistic and ideological understanding of the HSs, HL education as well as HL instructors’ development has not received enough attention (Beaudrie et al. 2014). There is still a lack of strict guidelines and standards for teacher development in regard to the role of reflection and meditation in teaching learners from diversity of languages, background and learning/teaching conditions (Lacorte 2016). This is crucial since language learning has been found to be connected with language ideology. Showstack (2010) introduces Pierce’s (1995) proposal arguing that language learners who believe that using the target language will bring them social return will make an impact in their attitude towards the language. Particularly, these language learners will invest more in the language and will be more likely to represent themselves as legitimate speakers by choosing to use the language in certain situations in which dominant power relations might not position them as legitimate. Nevertheless, if language learners perceive that the communities of speakers of the target language are disconnected in the ways the learners see themselves using the target language, it will affect their learning trajectories and investment in the language (Kanno and Bonny 2003; Norton 2001). For instance, Showstack discusses Helmer’s (2014) study, which found that students in an HL class resisted the ways instructors positioned them within imagined language communities (e.g., a professional community in which the learners will want to be integrated in the future), considering that the classroom interaction and pedagogical materials used in class did not seem to acknowledge students’ identities as HSs. Loza (2019) found as well how corrective feedback from instructors became an ideological act that expressed dominant beliefs and values about HSs and how they speak. Many of the HS respondents admitted being offended and not clearly understanding why certain variants were corrected in class.

Language learning can be also affected by learning situations, such as evaluative reactions towards the teacher, the language course, and the materials used in class (Gardner et al. 1985). Leeman (2012) and Leeman and Serafini (2016) point out that the educational system plays a role reproducing the “standard language” ideology by emphasizing a “proper” and “correct” usage of grammar, which transmits to students that there is a single acceptable way to speak and that nonstandard language is an obstacle to communication. This ideology can be transmitted through the course goals, teaching practices and materials used in class. In the case of HL programs, many courses and teaching practices have been found to fail to consider the different linguistic repertories of the HSs (Fairclough 1992) and put too much emphasis on “academic language”, reproducing the deficit ideologies of HSs living in the US (Leeman 2005). Materials used in class have also been found to reproduce ideologies. Spanish speakers in current L2 Spanish textbooks have been imagined as white, middle class monolinguals that the learner will be likely to meet on a trip (Herman 2007), whereas Spanish-speaking characters in textbooks have been found to be generic and failed to represent the ethnoracial diversity of the Spanish-speaking people living in the US (Leeman 2012). In the case of Spanish HL course textbooks, it has been found that the goals have shifted from a source of linguistic legitimacy and authority from the local community towards an imagined global standard, which is to communicate with monolinguals around the world, rather than with students, family and the local community (Leeman and Martínez 2007). This ideology can be transmitted also through the teaching practices of current instructors, in which they can assign novice positions to students by evaluating and correcting the language use or can also position students as experts by acknowledging the experience and knowledge the HSs bring into the classrooms (He 2004; Palmer et al. 2014; Showstack 2015). For instance, Lee (2002) notes in her study of Korean HSs attitudes towards their HL that they had negative feelings towards the instructors and felt that they were being forced to learn the language because it was their parent’s language. Many of the HSs doubted the effectiveness of the HL courses and mentioned the need to be informed of the benefits and usefulness of learning their HL. This suggests that instructional methods and program design might affect the HSs’ motivations to effectively learn their HL. This might be due to following a deficit-based approach, in which varieties that differ from the standardized norm are treated as needing correction (Martínez and Schwartz 2012). As a way to respond to this reality, critical approaches to Spanish HL curricula have suggested a new way of pedagogy, critical language awareness, which enhances linguistic empowerment by accepting each unique background knowledge of the heritage culture and linguistic varieties of the students as valuable assets in the HL classroom (Leeman 2005; Martínez and Schwartz 2012; Holguín Mendoza 2018; Parra 2016). At the same time, experts in the field suggest that HL programs need to invest in the development of current HL instructors and to achieve the seven goals of an HL course: maintenance of the HL, acquisition of prestige variety, expansion of bilingual range, transfers of literacy skills, acquisition of academic skills in the HL, cultivation of positive attitudes toward the HL and the acquisition or development of cultural awareness (Beaudrie et al. 2014; Valdés 2001). Lacorte (2016) lists several factors that should be considered as basic skills and knowledge for HL instructors: First, the understanding of the historical, cultural, sociolinguistic, and academic backgrounds of HSs as related to the teaching environment. Second, the awareness of the teacher’s own background (country of origin, HL proficiency, teaching experience, and professional identity). This is crucial, since ‘teachers’ ideologies’ connect with teachers’ values, goals and assumptions about the content and development of teaching and reflect their attitudes towards the HL and specific groups learning the HL. Third, instructors should understand the concept of linguistic variation in the country/community and identify their ideological positions towards the variability of dialects and registers. Thus, the ultimate goal of an HL classroom should become to achieve HL maintenance through thoughtfully selected materials, carefully designed courses and diverse training to current teachers and HL instructors. It is critical to rely on instructors that meet these criteria, as HL courses can be a source of motivation for HSs to acquire and maintain their HL as well as to develop their identity and attitudes as heritage bilinguals.

Spanish and Korean HSs Living in the US

Both Spanish and Korean HSs present their own history of immigration, language status, ethnic identity and schooling. The Latino community has had a long history of presence in the US. Starting from the XVI century, Spain established their first city in St. Augustine, Florida, as well as Mexico City and Texas, which were part of Mexico until 1936. Their residents were not immigrants but residents of the cities, even though they became US territory in 1845 (Montrul 2013). The recent wave of Latino immigration from the XX to the XXI century began due to the unstable economic and political status of their countries of origin. Many came to the US in search of work and a better life as farmers, workers or refugees. The Spanish status in the US is a complex one, since the Latino community comes from various backgrounds. The US Latino community is well aware of which varieties of Spanish are considered prestigious and which are not. For example, Puerto Rican community members in New York are well aware of the stigma associated with Puerto Rican Spanglish (Zentella 1997). Moreover, in a language attitude study of Spanish speakers in Miami where participants had to rank two criteria—pleasantness and correctness—all participants rated Peninsular Spanish most favorably and Mexican, Puerto Rican and Dominican varieties were ranked toward the bottom (Alfaraz 2002, 2014).

This is also reflected in the language ideologies presented by language instructors, societal discourses, academic assumptions and social beliefs (Showstack 2015). Although the Latino community in the US comes from varying backgrounds, the discrimination that this community has experienced in recent decades has led them to recognize their similarities and have come to accept the general label of Latino to identify them (Zentella 1997). Many Latino immigrant children and HSs of Spanish have the opportunity to learn Spanish starting from elementary or middle school level through bilingual education programs. However, whether these programs should focus on transitional objectives or prioritize HL maintenance is still under debate (Mar-Molinero 2000). Additionally, current public school language teachers lack understanding of their critical role in their students’ HL maintenance and development trajectory (Lee and Oxelson 2006). This leaves the unique necessities of HSs unmet, which may hinder their development and diminish their motivation to maintain their HL.

In comparison to the Latino community, the Korean community has had a relatively recent wave of immigration to the US starting from the 1970–80s after the passage of the US Immigration and Naturalization act of 1965. The majority of the immigrants who arrived in the 1970s were college-educated immigrants who came seeking economic advancement or political freedom from the military-controlled government. In the recent years, Korean immigrants come with the desire for a better education for their children and the primary focus at home is on English language education (Lee and Shin 2008) as well as their children’s status advancement in the future through education. This explains the diminishing effort from parents to their children’s HL maintenance (Lee 2002; Shin 2005). As opposed to the Latino community, the Korean community is not complex in the sense of language variety. However, Korean HSs struggle learning the honorific system, which is one of the most important sociolinguistic skills to master in their HL. The use of an incorrect honorific system poses trouble within the Korean community, since the community tends to be less forgiving to Korean Americans than non-Korean speakers. This is because the honorific system is an integral part of the Korean language and culture, and those who do not acquire it are regarded as non-genuinely Korean (Lee and Shin 2008). These attitudes can be expressed through elders from their community members or language instructors from Saturday Schools (Korean community language courses given generally at church) who are mostly untrained HS immigrant parents that lack the understanding of HL and the pedagogical practices necessary to HL instruction. The responsibility of the Korean language maintenance has been usually left for the family and the community and Korean language programs are typically offered for the first time at the university level (Lee and Shin 2008). The lack of HL proficiency and difficulty in learning and using the Korean language creates frustration among Korean HSs which is closely related to how they identify with their ethnological roots and are motivated to maintain their HL. However, the recent wave from Korean pop and dramas has created a new sense of desire to re-connect with their cultural backgrounds and acquire the sociopragmatics of their language (Yook et al. 2014).

The connection of language attitudes, motivations, and identity with the HL has been found in previous research on HSs of Spanish and Korean. Spanish HSs identify their HL as a way to reconnect with their heritage culture. However, for Spanish HSs, the main reason for taking an HL course is to develop their Spanish for professionalization purposes, particularly when having a career plan (Carreira and Kagan 2011). Spanish HSs often rate their Spanish as bad due to their lack of literacy and formal schooling. Another factor that affects their self-ratings is their experience being corrected in the language classroom when producing linguistic features typical of US Spanish (Potowski 2002). For instance, HSs reported valuing Spanish in the academic context and being bilingual but also expressed negative attitudes towards using local varieties (Achugar and Pessoa 2009). These results are also connected with instruction practices in language classrooms: instructors failing to recognize the varieties of Spanish spoken by heritage students at home may affect the HSs’ self-esteem and academic achievement in the HL (Bartolome and Macedo 1999; Carreira 2007).

For Korean HSs, as for their Spanish-speaking counterparts, learning the HL is also a way to reconnect with their heritage background. Kang (2015) found that, for Korean HSs, language equals identity, since not knowing the language was considered as losing their ethnic identity. The main reason for taking Korean classes among the respondents of Kang’s study was to learn their native language and reconnect with their Korean roots. However, most students were found to evaluate themselves as unsuccessful in their goal of maintaining their HL because they used the ‘non-standard’ version of the language. Even though they were using a version of Korean in progress, still unable to appropriately use the sociopragmatic norms but as a resource for constructing their identities, the pressure to achieve the ‘standard’ language practices was high. This behavior among Korean HSs was different when learning other languages. For example, Jeon (2005) notes that Korean HSs were much more reserved in Korean classes than in Spanish classes, fearing to make mistakes. In other words, the ideology of Korean HSs that they should be able to speak monolingual-like Korean appears to diminish the perceptions of how well they can speak the language. This example clearly shows how the HSs’ ideologies can shape their attitudes towards their HL.

These two groups of HSs living in the US display similar practices in terms of home and HL exposure during childhood. Carreira and Kagan (2011) noted that Spanish HSs were more likely than others to have learned to read in their HL before English (50% vs. 36.8%). They were also more likely to be read to by a parent or a relative in their HL than the average survey respondents (78.5% vs. 71.0%). Similarly, studies found that most Korean HSs children are dominant in Korean before they enter school (Shin and Milroy 1999). This is consistent with Min’s study (Min 2000), which reported that 62% of the first-generation adults claim little or no proficiency in English, and 95% of the parents report speaking only Korean to their children. In addition, 80.3% of Korean HSs reported being read to by a parent or relative, and reported the highest rate of participation in their HL communities (72.3%) (Carreira and Kagan 2011). However, there were two sharp contrasts between these two groups of HSs. First, Spanish HSs take HL courses with a future career or job in mind (71.1%), being one of the few HS groups who prioritized professional goals over personal goals. Conversely, Korean HSs reported taking HL courses with the least ambitious goal, which was to fulfill their language requirement (72.9%). Second, the majority of Spanish HSs rated their literacy skills in Spanish in the range of intermediate to native-like (95.5% reading and 86.5% for writing) although 45.5% had no experience studying the HL in their community or religious schools in the US. Nonetheless, Korean HSs rated their literacy skills in the range of intermediate to low proficiency (84.8% reading and 89.9% writing). The results were not explainable by a lack of exposure to the HL, since Korean HSs had the highest rate of community and church participation (72.3%) and participation to community events (50.4%).

With just the analysis of two different HL, it is clear that there are many factors in play when investigating HSs motivation in taking an HL class and personal experiences in the language classroom. Specifically, these factors become more complex depending on the origin of the language. While Spanish and Korean HSs seem to share the amount of exposure during childhood, the motivations for taking an HL course and attitudes towards their HL and how they self-measure their proficiency seem to differ.

In this study, we investigate how attitudes and expectations of HL courses differ across Spanish and Korean HSs presenting different HL proficiency and HL experience. We pose the following questions:

- Do HSs show different attitudes and expectations towards HL instruction depending on their HL?

- Are their attitudes and expectations modulated by their HL proficiency?

- Was academic instruction in the HL the most important factor in maintaining their HL?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

Ninety-two HSs completed a survey (available under Supplementary Materials) on their attitudes toward their HL: 51 Korean HSs and 41 Spanish HSs. The Korean HS group (37 females, age range = 18–29; M = 21.75, SD = 3.08) included both simultaneous (n = 27) and sequential (n = 24) bilinguals, according to how they self-identified in their survey responses. While simultaneous bilinguals acquired both their HL and English before the age of 3;00, sequential bilinguals spoke only their HL before the age of 3;00 and acquired English later in their childhood (Montrul 2013, p. 9). Among the sequential bilinguals, most of them reported starting to learn English between the ages of 3 and 5 (n = 17). Six of them began acquiring English between 6 and 10, and only one started learning English between 11 and 13. The Spanish HS group (25 females, age range = 18–35; M = 21.53, SD = 3.19) also included simultaneous (n = 17) and sequential (n = 24) bilinguals. Eleven sequential bilinguals started learning English between the ages of 3 and 5, nine reported learning English between 6 and 10, and four sequential bilinguals learned English between the ages of 11 and 13. The Spanish HSs were exposed to different varieties of Spanish by their main caretakers: El Salvador (n = 6), Dominican Republic (n = 5), Puerto Rico (n = 5), Mexico (n = 5), Ecuador (n = 4), Peru (n = 4), Colombia (n = 3), Cuba (n = 3), Argentina (n = 2), Bolivia (n = 2), Guatemala (n = 2), Costa Rica (n = 1), Paraguay (n = 1), and Spain (n = 1). Some Spanish HSs were exposed to more than one variety of Spanish by their main caretakers. Participants were recruited from different heritage Spanish and Korean classes at three universities in the US: while HSs of Spanish studied at institutions in the Northeast, HSs of Korean were recruited also from a university in the Southeast. However, HSs of Korean presented similar linguistic profiles and HL learning experiences regardless of the institution they attended. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by an Institutional Review Board (study ID: Pro2020001110).

Participants reported their HL use across different contexts by using a 1–10 Likert scale. Spanish HSs used their HL more than their Korean-speaking counterparts when communicating in their social circles: with their parents (M = 7.12, SD = 3.15 among Spanish HSs vs. M = 6.57, SD = 3.21 among Korean HSs), with their siblings (M = 3.53, SD = 2.88 among Spanish HSs vs. M = 2.57, SD = 2.28 among Korean HSs), with their friends (M = 3.73, SD = 2.55 among Spanish HSs vs. M = 2.92, SD = 2.24 among Korean HSs), with their partners (M = 2.46, SD = 2.74 among Spanish HSs vs. M = 1.88, SD = 2.01 among Korean HSs). This same trend occurs in other settings: at school (M = 4.07, SD = 2.32 among Spanish HSs vs. M = 2.04, SD = 1.57 among Korean HSs) and at work (M = 3.29, SD = 2.48 among Spanish HSs vs. M = 1.55, SD = 1.64 among Korean HSs).

A consistent pattern is observed in their self-reported dominant language: while 76.47% of the Korean HSs (n = 39) reported feeling more comfortable in English and 19.61% (n = 10) felt equally comfortable in English and in their HL, 53.66% of the Spanish HSs (n = 22) felt more comfortable in English and 43.90% (n = 18) felt equally comfortable in Spanish and English. In each group, only one HS reported feeling more comfortable in their HL.

As seen in Table 1 above, the two HS groups also present differences in the settings in which they started receiving formal instruction in their HL: while most Korean HSs started being formally instructed in their HL at church or at community schools, most Spanish HSs received their first formal HL instruction at elementary school.

Table 1.

First formal heritage language (HL) instruction settings among Korean and Spanish HSs.

3.2. Materials and Statistical Analyses

The participants completed a 41-question survey adapted from Carreira and Kagan (2011) and Lee (2002) where they reported their language background, their self-rated HL proficiency, and their experience with their HL at home and in their communities. Furthermore, the survey inquired about what aspects of HL and culture should be targeted in HL courses and what activities would be more beneficial for them. HL classroom materials and activities were grouped into two categories: activities for a professionalization purpose (APP) and activities for entertainment purposes (AEP). The former includes being exposed to books, newspapers, and poetry, as well as translation exercises, and community outreach programs, while the latter encompasses using materials such as dramas, movies, music, websites, and magazines in the classroom. Respondents usually took from 15 to 20 min to complete the survey.

We analyze the data using one-way and two-way ANOVAs when comparing the two groups of HSs by looking at either one or two variables. Effect sizes are reported with the use of eta squared (η2). Additionally, when exploring data including more variables, generalized mixed effects models (GLMMs) were used. Particularly, GLMMs were employed when analyzing the HSs’ responses to whether they considered a series of classroom activities beneficial form them. The model included their binary response (1 for ‘yes’ or 0 for ‘no’) as a dependent variable, and, as independent variables, HS group (Korean or Spanish HS), type of activity, and self-reported proficiency.

4. Results

Participants self-rated their HL proficiency across skills by (speaking, listening, writing, and reading) by using a 1 to 6 Likert scale (1—very low, 2—low, 3—intermediate, 4—advanced, 5—near-native, 6—native). A series of one-way ANOVAs found that, across all skills, Spanish HSs rated their proficiency higher than Korean HSs: speaking (F(1, 33.48) = 16.31, p < 0.01; η2 = 0.15), listening (F(1, 27.26) = 14.57, p < 0.01; η2 = 0.14), writing (F(1, 26.16) = 18.06, p < 0.01; η2 = 0.17), and reading (F(1, 36.98) = 19.61, p < 0.01; η2 = 0.18). Table 2 below shows the two HL groups’ self-rated proficiency across skills as well as an averaged self-rated proficiency for each HL group.

Table 2.

Self-rated proficiency in the HL across skills and heritage speaker (HS) groups.

Participants rated the importance of some aspects of HL courses using a 1 to 5 Likert scale (1—not important at all, 2—not important, 3—neither important nor not, 4—important, 5—very important). A series of two-way ANOVAs including their ratings as dependent variables and, as independent variables, HL and self-rated proficiency as well as an interaction between them found differences between the two HL groups in how important they consider three course objectives that HL classes may incorporate: improving writing skills (F(1, 7.98) = 6.72, p = 0.01; η2 = 0.02), grammatical accuracy (F(1, 15.00) = 13.54, p < 0.01; η2 = 0.10), and vocabulary size (F(1, 6.01) = 8.42, p < 0.01; η2 = 0.05) were deemed more important by Spanish HSs. However, the participants’ ratings for improving speaking skills (F(1, 1.56) = 2.34, p = 0.13), listening skills (F(1, 0.01) = 0.01, p = 0.93), reading skills (F(1, 2.45) = 1.63, p = 0.21), and cultural and formality awareness (F(1, 3.92) = 3.88, p = 0.05) did not differ across HL groups. Table 3 summarizes the participants’ improvement goals across HL groups.

Table 3.

Areas that participants desire to improve across HS groups.

The series of two-way ANOVAs found that self-rated proficiency only had an effect on the HSs’ goals to improve their writing skills (F(1, 7.45) = 6.27, p = 0.01; η2 = 0.06). This suggests that participants whose self-rated proficiency was higher reported that they considered improving their writing skills more important than those with lower self-rated proficiency. No interactions between HL group and self-rated proficiency were found in any ANOVA.

Participants also rated the importance of a series of purposes that their HL may contribute to accomplish using a 1 to 10 Likert scale. As for the HL course objectives, both HL groups rated some purposes similarly: to communicate better with my family (F(1, 1.91) = 0.35, p = 0.55), to communicate better with my community (F(1, 24.9) = 3.49, p = 0.06), and to travel to my country of heritage (F(1, 17.78) = 2.24, p = 0.14). The Spanish HSs, however, rated one purpose higher than their Korean-speaking counterparts: job purposes (F(1, 226.78) = 28.33, p < 0.01; η2 = 0.19). No self-rated proficiency effects or interactions were found in these ANOVAs. Table 4 below presents this between-group comparison.

Table 4.

HL purposes across HS groups.

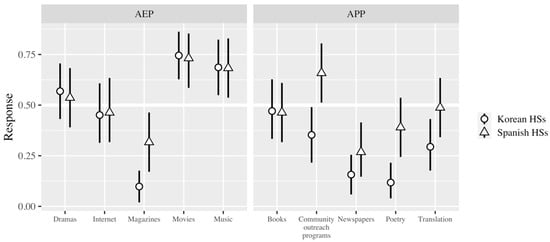

Additionally, the survey inquired HSs about what activities would be more beneficial for them. Potential HL classroom materials and activities were grouped into two categories: activities for professionalization purposes (APP) and activities for entertainment purposes (AEP). The former includes being exposed to books, newspapers, poetry as well as translation exercises, and community outreach programs, while the latter encompasses using materials such as dramas, movies, music, websites, and magazines in the classroom. While APP reflect traditional instructional practices that may have a clear impact on the professionalization of the students’ HL, AEP focus on providing HSs with opportunities to being exposed to their HL and culture. AEP are crucial for their cultural and sociopragmatic knowledge in their HL and attract, among others, Korean HSs looking to strengthen their connections with their heritage community in the times of the Korean culture wave. Both APP and AEP seek to invite HSs to acquire and maintain their HL by providing them with a variety of input and different situations in which to use their HL. Participants were asked to select which activities/materials they would consider beneficial. Figure 1 and Table 5 show the proportion of how many participants selected each activity/material within each HL group.

Figure 1.

Activities and materials considered beneficial by HSs across HL groups.

Table 5.

Activities and materials considered beneficial by HSs across HL groups.

In order to explore this data, we ran a generalized linear mixed model including the participants’ selection of each activity/material (0 ‘non-selection’, 1 ‘selection’) as dependent variable and, as fixed factors, HL group (‘Spanish’ or ‘Korean’) and type of activity/material (‘APP’ or ‘AEP’). The model also included an interaction between the two fixed factors and ‘participant’ as a random effect.

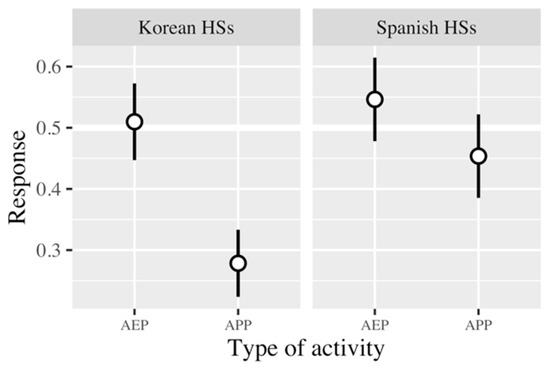

The model did not find HL group effects (β = 0.18, SE = 0.26, z = 0.67, p = 0.50), but type of activity/material was a significant predictor in the HSs’ selections (β = −1.13, SE = 0.20, z = −5.59, p < 0.01), which indicates that AEPs were preferred over APPs. Additionally, the interaction between activity/material type and HL group determined that Spanish HSs selected APPs as beneficial more than their Korean-speaking counterparts (β = 0.70, SE = 0.29, z = 2.39, p = 0.02). Figure 2 shows which category of activities/materials are favored by each group of HSs.

Figure 2.

Activity/material type preferences across HL groups.

Participants were also asked if they considered their HL an asset that could bring success to their careers. All Spanish HSs (n = 41) responded affirmatively while the Korean HSs’ responses were not as categorical: 67% (n = 34) considered that their HL would bring success to their career, 31% (n = 16) responded negatively, and one participant did not answer. A generalized linear mixed model including the Korean HSs’ responses to this question as dependent variable, their self-rated proficiency as fixed factor, and ‘participant’ as a random effect determined that their responses were modulated by proficiency (β = 0.83, SE = 0.43, z = 2.43, p = 0.02). This indicates that Korean HSs whose HL proficiency is higher believe their HL will bring success to their career while those who rated their proficiency as lower did not have such expectations for their HL in their future careers.

Finally, participants reported how important a series of factors were in helping maintain or improve their HL skills by using a 1 to 10 Likert scale. Korean HSs rated family and friends as the most important factor (8.20/10), followed by travel to a destination where the HL is spoken (6.69/10), TV and media (6.02/10), and HL classes (5.81/10). Reading was rated the lowest among the possible factors (4.21/10). The Spanish HSs also rated family and friends as the most decisive factor (8.63/10) closely followed by travel to a destination where the HL is spoken (8.42/10). Unlike the Korean HS group, Spanish HSs rated HL classes as the third most important factor (7.28/10) instead of TV and media (6.49/10) while reading was also deemed the least influential factor among Spanish HSs (6.26/10). Table 6 summarizes the HS groups’ perception of how influential HL courses are in HL maintenance in comparison with other factors.

Table 6.

Reported importance of factors contributing to HL maintenance across HS groups.

In summary, these results show that the Spanish HSs in this study self-rate their HL proficiency higher than the Korean HSs. However, self-rated proficiency does not seem to modulate the participant responses (only those Spanish HSs with higher self-rated proficiency rated improving their writing skills higher than their lower-proficient counterparts, and Korean HSs with higher self-rated proficiency gave more importance to their HL as a potential key for professional success). These HS groups also present differences in the expectations they have regarding HL courses: particularly, the Spanish HSs are interested in improving their writing skills, grammatical accuracy, and vocabulary size more than the Korean HSs. On the same line, the Spanish HSs differ from the Korean HSs in their willingness to improve their HL skills for job purposes. Indeed, while all Spanish HSs consider that their HL will help them in their future careers, only those Korean HSs whose self-rated proficiency was higher deemed their heritage Korean as a useful tool for professional success. This pattern is reflected in the type of activities and materials each HS group favors in the HL classroom: both groups enjoy using activities that may include some entertainment component (e.g., movies, dramas, music, etc.), but the Spanish HSs consider that other professionalizing activities and materials (e.g., books, translation, community outreach programs, poetry, etc.) are beneficial in the HL classroom, unlike the Korean HSs. Finally, both groups report that family and friends and travel to a destination where their HL is spoken are the main contributing factors in their HL acquisition and maintenance while HL classes are ranked third for the Spanish HSs and fourth for the Korean HSs, behind TV and media.

5. Discussion

Spanish and Korean HSs represent two of the highest growing HLs in the US as well as two of the most frequently offered HL courses at the academic level across the country. The study of these two different HL groups, who represent two diverging realities of HLs in the US, provides insight into how the motivations and expectations of HSs are shaped by their HL and their communities. While Spanish is typologically similar to English and features a significant demographic, social, and economic presence and proximity to the US, Korean is typologically dissimilar to the dominant language and has lesser presence in the country. Specifically, some factors that affect the decision of taking HL courses among HSs include: socio-cultural dimensions, such as cultural identity and attitudes towards their HL group, the histories and life situations of the individual learners, and their learning situations, such as evaluative reactions towards the teacher, the language course, and the materials used in class. In this study, in order to explore how these factors are influenced by differences in the HL and their communities, we investigate how attitudes and expectations towards HL courses differ across two specific groups: Spanish and Korean HSs.

For our first research question, which inquired about the different attitudes and expectations towards HL courses among Spanish and Korean HSs, our results found that Spanish HSs have higher expectations to improve their writing skills, grammatical accuracy, and vocabulary size than their Korean-speaking counterparts. Additionally, Spanish HSs point out their desire to receive more explicit instruction than Korean HSs. Both groups seem interested in taking their HL acquisition and maintenance outside the classroom, either at community outreach programs or study abroad experiences, which are deemed as crucial for some of them. Additionally, while both groups consider activities with entertainment components (e.g., dramas, movies, music, etc.) beneficial in HL classes, activities and materials for professionalizing purposes (e.g., translation, newspapers, community outreach programs, etc.) are clearly favored by Spanish HSs.

Our second research question explored the role of proficiency in their attitudes and expectations towards HL instruction. We found that those Spanish HSs who self-rated their proficiency higher were more likely to be willing to improve their writing skills in HL courses, suggesting that those Spanish HSs whose proficiency was not as high might have other goals for their HL courses. Although not strictly related to HL instruction, Korean HSs seem to display different attitudes towards their HL depending on their proficiency: low-proficient Korean HSs regret not being fluent in their HL as it prevents them from connecting to their community while those Korean HSs whose proficiency is higher value their HL as a tool to establish a bond with their community. Similarly, proficient Korean HSs view their HL as an asset for professional success.

Our third research question investigated whether HSs considered HL instruction as the main factor for their HL acquisition and maintenance. Both Korean and Spanish HSs consider their families and friends as the most important factor for maintaining their HL, followed by the opportunity to travel to countries where their HL is spoken. Additionally, Korean HSs also consider being exposed to TV and media as being more important than HL courses for acquiring and maintaining their HL.

The results of our study provide invaluable insight into how attitudes and expectations of an HL course can differ among different HL groups. While both Spanish and Korean HSs express their interest in participating in community outreach programs and study abroad experiences as well as in working with in-class activities that feature cultural and entertainment components in their HL, only the Spanish HSs expressed their high expectation to improve their writing skills, grammatical accuracy, and vocabulary size through activities and materials for professionalizing purposes. Similar results were found in Carreira and Kagan (2011), who found Spanish HSs to be the most numerous HS group to take an HL course with a particular profession in mind. For Korean HSs, professionalizing their HL skills was not their top priority, which is consistent with previous studies in which Korean HSs were found to have the least ambitious goal for taking an HL course, which was to fulfill their language requirement (Carreira and Kagan 2011). Many of the Spanish HS participants mentioned the desire for explicit instruction or correction during class as a way to professionalize their HL skills. These results support previous research that suggests that HSs can benefit from explicit instruction or correction during HL classes (Montrul and Bowles 2010; Potowski et al. 2009; Torres 2018). However, Korean HSs expressed their desire for more opportunities to reconnect with their heritage culture and gain knowledge of the sociopragmatics of their HL, which are needed in their everyday interactions with the community. Many of the Korean HSs responded to the importance of study abroad programs as a means to expand their HL skills. Similarly, they also favored having more opportunities to being exposed to Korean language input through dramas, movies and music. We suggest that this particular difference rises from the complexities of the Korean honorific system, which requires a more extended knowledge of the language and culture. Jo (2001) argues that the Korean honorific system is the most challenging area of the Korean language since it requires not only the choice of expected terms of address and different verbal suffixes or enclitics, but also the decision about the social relationship between the speaker and the addressee, such as age, social status, intimacy and kinship levels. The motivations for Korean HSs clearly contrast with the Spanish HSs’ motivations, and support previous studies that claim that the motivations for Korean HSs to take an HL course are more integrative than instrumental (Kim 2002; Carreira and Kagan 2011). Our results show that the type of activities and materials preferred by Spanish and Korean HSs reflects their expectations and attitudes towards HL instruction: the Spanish HSs’ priority in professionalizing their HL skills is what motivates their preference for explicit grammatical instruction and activities for professionalization purposes. Korean HSs, on the other hand, prefer activities and materials with cultural and entertainment components and favor study abroad programs due to their desire to fully be exposed to their HL and culture and understand the sociopragmatics of their HL.

There are several implications in our findings for HL classrooms. First, we suggest Spanish HL classes to select materials that focus on professionalizing activities such as translation and activities that develop presentational and writing skills. Second, Spanish HL instructors need to be aware of the expectations of Spanish HSs that express their desire for more explicit instruction or corrective feedback such as detailed grammatical feedback or instruction. Third, Korean HL classes require more speaking opportunities that can sufficiently expose speakers to different speaker and addressee relationships so that HSs can practice the vast system of Korean honorific expressions. Nonetheless, instructors should build up from the linguistic and cultural background that the Korean HSs bring to class and acknowledge the still developing Korean versions of the students as a way to identify and communicate in class. Lastly, specifically in Korean HL classes, we suggest the use of TV and media materials that target the different interactions of speaker and addressee depending on the age, social status, and level of intimacy. However, these implications might not be extended to all HSs, particularly among receptive HSs.

These findings support current research and instructional proposals in the field of HL. A critical language awareness approach to HL teaching, which is centered around the students’ HL varieties and from which instructors invite students to acquire prestige varieties of their HL (Beaudrie et al. 2014; Leeman 2005; Martínez and Schwartz 2012; Holguín Mendoza 2018; Parra 2016), could have an impact on the Korean HSs, who only see their HL as an asset for professional success if they consider themselves proficient in it, in contrast with Spanish HSs. We argue that Korean HL instructors, particularly in settings as cultural centers and churches, could benefit from adopting a critical language awareness approach. Following this approach, instructors should embrace varieties of heritage Korean and see them as valuable assets instead of following a deficit-based approach (Martínez and Schwartz 2012), in which heritage Korean is treated as non-standard varieties needing correction, mostly in their sociopragmatics.

On the other hand, the Spanish HSs appear to value their HL skills and the impact they can have on their professional success and on the Latino community. Spanish HSs believed they could benefit from professionalization opportunities in their HL courses, as opposed to HSs of Korean. This contrast is particularly noticeable in their perception of community outreach programs, which were clearly favored by Spanish HSs. The benefits of this type of programs have been investigated in Spanish HS students. Lowther Pereira (2015) and Martínez and Schwartz (2012), who examined the development of HL skills in Spanish HSs participating in service-learning programs within their local Latino community and found that students took on the commitment to maintaining their HL, felt more connected with the local Latino community, developed their HL skills in high-stakes contexts, and learned to understand and appreciate language variation in Spanish.

The advances in HL pedagogy for Spanish HSs in the US, particularly the adoption of a critical language awareness approach, has allowed HSs and their instructors to embrace their HL varieties and use it to make an impact on their local Latino communities while expanding their bilingual range and acquiring the prestige variety of their HL. These advances could contribute to Korean HL instruction, particularly in high-impact settings such as churches and cultural centers.

The study of two diverging HLs in the US, one that is typologically similar and one that is typologically dissimilar to the dominant language, points out the impact of HSs’ attitudes and expectations towards the courses that teach the HL. In addition, it provides insights into the need for a critical language awareness approach both from the side of the instructors as well as the course curricula in order to enhance the linguistic as well as cultural identity of the speakers.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2226-471X/6/1/14/s1, Survey S1: Language Attitudes towards Heritage Language.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H. and J.C.L.O.; Formal analysis, E.H. and J.C.L.O.; Investigation, E.H. and J.C.L.O.; Methodology, E.H. and J.C.L.O.; Project administration, E.H.; Resources, E.H., J.C.L.O., and E.L.; Supervision, E.H.; Validation, E.H. and J.C.L.O.; Visualization, J.C.L.O.; Writing—original draft, E.H., J.C.L.O. and E.L.; Writing—review & editing, E.H. and J.C.L.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by an Institutional Review Board (study ID: Pro2020001110).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to participant confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the subjects who took part in this study and the audience at the 2020 LASSO Conference.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Achugar, Mariana, and Silvia Pessoa. 2009. Power and place Language attitudes towards Spanish in a bilingual academic community in Southwest Texas. Spanish in Context 6: 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela. 2002. Miami Cuban perceptions of varieties of Spanish. In Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology. Edited by Daniel Long and Dennis Preston. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 2, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela. 2014. Dialect perceptions in real time: A restudy of Miami Cuban perceptions. Journal of Linguistic Geography 2: 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolome, Lilia I., and Donaldo Macedo. 1999. (Mis)educating’ Mexican Americans through language. In Sociopolitical Perspectives on Language Policy and Planning in the USA. Edited by Thom Huebner and Kathryn A. Davis. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 223–41. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudrie, Sara M., Cynthia Ducar, and Kim Potowski. 2014. Heritage Language Teaching: Research and Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill Education Create. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, Maria. 2007. Spanish-for-Native-Speaker matters: Narrowing the Latino achievement gap through Spanish language instruction. Heritage Language Journal 5: 147–71. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, Maria, and Olga Kagan. 2011. The results of the national heritage language survey: Implications for teaching, curriculum design, and professional development. Foreign Language Annals 44: 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Grace. 2000. The role of heritage language in social interactions and relationships: Reflections from a language minority group. Bilingual Research Journal 24: 369–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Grace. 2015. Perspectives vs. reality of heritage language development voices from second-generation Korean-American high school students. Multicultural Education 22: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Donitsa-Schmidt, Smadar, Ofra Inbar, and Elana Shohamy. 2004. The effects of teaching spoken Arabic on students’ attitudes and motivation in Israel. The Modern Language Journal 88: 217–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 1992. The appropriacy of ‘appropriateness’. In Critical Language Awareness. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Robert C., Richard N. Lalonde, and Regina Moorcroft. 1985. The role of attitudes and motivation in second language learning: Correlational and experimental considerations. Language Learning 35: 207–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Agnes Weiyun. 2004. Identity construction in Chinese heritage language classes. Pragmatics 14: 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- He, Agnes Weiyun. 2010. The hearth of heritage: Sociocultural dimensions of heritage language learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 30: 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, Kimberly Adilia. 2014. It’s not real, it’s just a story to learn Spanish: Understanding Spanish heritage-language student resistance in a Southwest charter high school. Heritage Language Journal 11: 186–206. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Deborah M. 2007. It’s a small world after all: From stereotypes to invented worlds in secondary school Spanish textbooks. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 4: 117–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín Mendoza, Claudia. 2018. Critical language awareness (CLA) for Spanish heritage language programs: Implementing a complete curriculum. International Multilingual Research Journal 12: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Mihyon. 2005. Language Ideology, Ethnicity, and Biliteracy Development: A Korean-American Perspective. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Hye-Young. 2001. ‘Heritage’ Language Learning and Ethnic Identity: Korean Americans’ Struggle with Language Authorities. Language, Culture, and Curriculum 14: 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M. Agnes. 2015. Social aspects of Korean as a heritage language. In The Handbook of Korean Linguistics. Edited by Lucien Brown and Jaehoon Yeon. Malden: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 405–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kanno, Yasuko, and Norton Bonny. 2003. Imagined communities and educational possibilities: Introduction. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education 2: 241–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hi-Sun Helen. 2002. The language backgrounds, motivations, and attitudes of heritage learners in KFL classes at University of Hawaii at Manoa. The Korean Language in America 7: 205–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lacorte, Manel. 2016. Teacher development in heritage language instruction. In Innovative Strategies for Heritage Language Teaching: A Practical Guide for the Classroom. Edited by Marta Fairclough and Sara M. Beaudrie. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jin Sook. 2002. The Korean language in American: The role of cultural identity in heritage language learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum 15: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jin Sook, and Eva Oxelson. 2006. “It’s not my job”: K–12 teacher attitudes toward students’ heritage language maintenance. Bilingual Research Journal 30: 453–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jin Sook, and Sarah J. Shin. 2008. Korean heritage language education in the United States: The current state, opportunities, and possibilities. Heritage Language Journal 6: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jin Sook, and Debra Suarez. 2009. A synthesis of the roles of heritage languages in the lives of immigrant children. In The Education of Linguistic Minority Students in the United States. Edited by Terrence G. Wiley, Lee Jin Sook and Russel W. Rumberger. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 136–71. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2005. Engaging critical pedagogy: Spanish for native speakers. Foreign Language Annals 38: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Jennifer. 2012. Investigating language ideologies in Spanish as a heritage language. Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: The State of the Field 43: 59. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, Jennifer, and Glenn Martínez. 2007. From identity to commodity: Ideologies of Spanish in heritage language textbooks. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 4: 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, Jennifer, and Ellen J. Serafini. 2016. Sociolinguistics for heritage language educators and students. In Innovative Strategies for Heritage Language Teaching: A Practical Guide for the Classroom. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wei. 1994. Three Generations, Two Languages, One Family: Language Choice and Language Shift in a Chinese Community in Britain. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Lowther, Kelly. 2015. Developing Critical Language Awareness Via Service-Learning for Spanish Heritage Speakers. Heritage Language Journal 12: 159–85. [Google Scholar]

- Loza, Sergio. 2019. Exploring Language Ideologies in Action: An Analysis of Spanish Heritage Language Oral Corrective Feedback in the Mixed Classroom Setting. Ph.D. dissertation, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mar-Molinero, Clare. 2000. The Politics of Language in the Spanish-Speaking World: From Colonisation to Globalisation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Glenn, and Adam Schwartz. 2012. Elevating “Low” Language for High Stakes: A Case for Critical, Community-Based Learning in a Medical Spanish for Heritage Learners Program. Heritage Language Journal 9: 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Pyong Gap. 2000. Korean Americans’ language use. In New Immigration in the United States: Readings for Second Language Educators. Edited by Sandra Lee McKay and Sau-ling Cynthia Wong. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 306–32. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2013. El Bilingüismo en el Mundo Hispanohablante. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina, and Melissa Bowles. 2010. Is grammar instruction beneficial for heritage language learners? Dative case marking in Spanish. Heritage Language Journal 7: 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Yoshiko, and Toshiko M. Calder. 2015. The role of motivation and learner variables in L1 and L2 vocabulary development in Japanese heritage language speakers in the United States. Foreign Language Annals 48: 730–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, Bonny. 2001. Non-participation, imagined communities and the language classroom. In Learner Contributions to the Language Learning: New Directions in Research. Edited by Breen Michael P. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, pp. 159–71. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Deborah K., Ramón Antontio Martínez, Suzanne G. Mateus, and Kathryn Henderson. 2014. Reframing the Debate on Language Separation: Toward a Vision for Translanguaging Pedagogies in the Dual Language Classroom. The Modern Language Journal 98: 757–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, María Luisa. 2016. Critical approaches to heritage language instruction: How to foster students’ critical consciousness. In Innovative Strategies for Heritage Language Teaching: A Practical Guide for the Classroom. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 166–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, Bonny Norton. 1995. Social identity, investment, and language learning. TESOL Quarterly 29: 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim. 2002. Experiences of Spanish heritage speakers in university foreign language courses and implications for teacher training. ADFL Bulletin 33: 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim, Jill Jegerski, and Kara Morgan-Short. 2009. The effects of instruction on linguistic development in Spanish heritage language speakers. Language Learning 59: 537–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Sarah J. 2005. Developing in Two Languages: Korean Children in America. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Sarah J., and Lesley Milroy. 1999. Conversational codeswitching among Korean-English bilingual children. International Journal of Bilingualism 4: 351–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showstack, Rachel E. 2010. Going beyond “appropriateness”: Foreign and heritage language students explore language use in society. In The Proceedings of Intercultural Competence Conference. Edited by Beatrice Dupuy and Linda Waugh. Tucson: University of Arizona, pp. 358–77. [Google Scholar]

- Showstack, Rachel E. 2015. Institutional representations of ‘Spanish’ and ‘Spanglish’: Managing competing discourses in heritage language instruction. Language and Intercultural Communication 15: 341–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Julio Rubén. 2018. The effects of task complexity on heritage and L2 Spanish development. Canadian Modern Language Review 74: 128–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Lucy. 2001. Heritage language literacy: A study of US biliterates. Language, Culture, and Curriculum 14: 256–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. Table B16001: Language Spoken at Home by Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and over. American Community Survey 8. Available online: https://data.census.gov (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2001. Heritage language students: Profiles and possibilities. In Heritage Languages in America: Preserving a National Resource. Edited by Joy Kreeft Peyton, Donald A. Ranard and Scott McGinnis. McHenry: Center for Applied Linguistics, pp. 37–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yook, Eunkyong Lee, Young-ok Yum, and Sunny Jung Kim. 2014. The effects of Hallyu (Korean wave) on Korean transnationals in the US. Asian Communication Research 11: 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zentella, Ana Celia. 1997. Growing up Bilingual: Puerto Rican Children in New York. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).