1. Introduction

In the standard Japanese language, polite language forms are ornately structured and highly prescribed so that one cannot communicate without them, whereas in nonstandard dialects of Japanese, they tend to be simpler and have smaller repertories. On the other hand, the typical politeness system of Brazilian Portuguese is oriented towards the widely attested T–V distinction (tu–você in Portuguese). Thus, here I ask what sort of polite language forms are used by Brazilian-Japanese who have had access to Japanese nonstandard dialects, standard Japanese, and Brazilian Portuguese in their community history.

Brazil is home to some 1.4 million Japanese immigrants and their descendants. The term “Nikkei” is commonly used to refer to those people in Brazil, but definitions in the literature can vary. In this paper, “Nikkei-Brazilians” refers to the children of Japanese who immigrated to Brazil (i.e., second generation, nisei) and their descendents (i.e., third and fourth generations, sansei and yonsei). However, issei, the first generation, refers only to those who migrated to Brazil before the age of six; hence, adult immigrants are not included as Nikkei-Brazilians in this study, because they have already passed the critical period of language acquisition.

In this study, two distinct Japanese speech communities were identified on the basis of community history. The first type is called the

Colonia—the Japanese settlement villages organized by both the Japanese and Brazilian governments to accommodate Japanese immigrants, and which exist throughout Brazil but are particularly concentrated around São Paulo. In the

Colonia, traditional Japanese events, religion, language, and lifestyle are maintained, even today. They are exclusively Japanese communities in which there are extremely dense and multiplex social networks amongst members.

1 They have their own Buddhist temples and hospitals, where Japanese is used, and gathering places called

bunkyoo (e.g., Sociedade Brasileira de Cultura Japonesa e de Assistência Social, Brazilian Society of Japanese Culture and Social Welfare), where members can join numerous club activities (e.g., playing the board game

go, or the martial art

kendo, learning about

bonsai for male members, Japanese flower arrangement, learning/practicing the tea ceremony and traditional dancing for female members, as well as the Japanese poetry form of

haiku, and folk and karaoke song contests for all members) and where they receive legal advice in Japanese on complex matters of contemporary life such as insurance. In terms of language education, ample opportunities are provided not only by schools, where Japanese is the language of instruction, but also by the temples and local

bunkyoo, where Japanese is taught as an additional language. Importantly, through such organized communal life in the

Colonia, members acquire traditional verbal and nonverbal Japanese strategies of showing respect to elders.

The second type of community I will label “urban”. Here, the Colonia members left rural agricultural life, moving to urban areas in Brazil, especially after the Second World War, with the aim of assimilating into Brazilian society as Brazilians rather than as Japanese. They are mainly third-generation and were thoroughly educated in Brazilian schools but later went to Japanese language schools to learn their parents’ language when they became more aware of their ethnic heritage and when the Japanese economy was booming during the period of 1980s–2000s. Many Nikkei-Brazilians have undergone profound changes in ethnic self-identity and in their livelihood as a result of this urbanization.

A previous study (

Yamashita 1995) examined, from a macro-perspective, the extent to which Japanese is used in Brazil, revealing that in the

Colonia, half the population used Japanese exclusively, while in urban areas, half the population used Japanese only in the home. In this paper, I focus in more detail on the linguistic characteristics of their Japanese, particularly examining their use of both polite language forms and spousal address terms.

The approach taken in this paper is: (1) to provide the historical and linguistic context of the Japanese community in Brazil; (2) to describe the data collection instrument and methods used in this research; and (3) to familiarize the reader with the data analysis technique employed, before (4) presenting the results and discussing their implications. For the purpose of this paper, I only examined data extracted from my questionnaire (see

Yamashita 2007 for further details about the questionnaire-based research).

2. Background of the Japanese and Nikkei-Brazilians in Brazil

In this section, I first describe the history of the Nikkei-Brazilians during the periods both before and after the Second World War, particularly paying attention to the demographics of immigrants in each period (for details, see

The Consular and Emigration Affairs Department, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1971). I shall then briefly discuss Nikkei-Brazilian life in both the

Colonia and the urban areas, as well as the generational differences in the degree of assimilation into Brazilian society.

In accordance with agreements between the Japanese and Brazilian governments, from 1908 until 1941 when indentured labor migration began, some 200,000 Japanese immigrated to Brazil. The demographics of these immigrants suggest a diverse but stable population. First, in terms of geographic origins, the majority came from Western Japan (such as Kumamoto, Fukuoka and Yamaguchi prefectures) and Okinawa (

The Consular and Emigration Affairs Department, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1971, pp. 52–53, 140–41). Consequently, a number of different dialects such as varieties of western and Ryûkyûan dialects of Japanese were introduced into the Japanese settlement areas. Second, few immigrants arrived as isolated individuals; only 6.1% entered as single individuals, while the vast majority 93.9% were part of family groups, since single entry was not allowed in Brazil (

Uchiyama 2001, p. 16). In terms of religion, only 15.5% of the Japanese immigrants were Christians. The majority, 70.6%, were Buddhists and the rest nonbelievers or believers of other religions (13.9%) (

Mizuki 1978, p. 17). Given that Christianity is the main religion in Brazil, this led somewhat to the cultural isolation of the Japanese population in Brazilian society. Thirdly, those who immigrated were relatively educated, with a 72.9% literacy rate (

Fujii and Smith 1959, p. 11).

2 Fourth, in terms of occupation, the majority of the immigrants had previously been farmers (98.8%) or had engaged in activities ancillary to agriculture in rural areas (

Higa 1982, p. 157;

Fujii and Smith 1959, p. 13). In Japan, it was common for farmers to organize mutually co-operative systems in order to increase productivity, engendering strong ties in their social networks. Therefore, for immigrants who started to work in coffee plantations, pre-existing co-operative systems were usefully adopted.

Due to the abolition of the agreement on indentured labor between the Japanese and Brazilian governments, during the post-war period, individual immigration took over from the family-based immigration that had been characteristic of the first period of immigration. From 1945 to the mid-1960s, another 50,000 mostly adult Japanese immigrants arrived. These immigrants tended to be from Western Japan, since individual immigrants often joined their relatives who had already migrated to Brazil (

The Consular and Emigration Affairs Department, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1971, pp. 7–30).

However, beginning in the mid-1980s when the Japanese economy was booming, a large-scale reverse migration occurred. As many as 310,000 Nikkei-Brazilians were working in Japan from 2006 to 2008 (

Mita 2011, p. 24). The term

dekasegi (which roughly means ‘working away from home’) became the popular term used to describe Nikkei-Brazilians both in Japan and Brazil. Currently, many

dekasegi in Japan are in immersion Japanese-language classes, and I would predict further changes to the Japanese language spoken in Brazil due to the growing influence of Standard Japanese (see

Nakamizu 1996,

1997,

1998;

Yamashita 1999a, for sociolinguistic work on dekasegi Nikkei-Brazilians in Japan).

Most Japanese immigrants were initially plantation contract laborers in the pre-War period and lived in the

Colonia. The rural location of the

Colonia meant that residents often experienced difficulties such as a lack of water and electricity, inadequate roads, and unsanitary housing. However, they understood that the cultivation of cash crops would be essential to their socioeconomic advancement and most aimed to become small, independent landowners. For most, the dream was to educate their children and to have a good social standing in their community. By introducing intensive agriculture, they met with some success. In 1923, a self-census showed that 53% of the Nikkei-Brazilians were independent farmers, and over one third of some 10,000 households owned their own land (

Reichl 1995, p. 40). Although the majority of Nikkei would remain in rural areas throughout the pre-War period, some 2000 resided in urban São Paulo, where ethnic restaurants, stores, health care, legal and immigration assistance, banking and loan services could be found.

The

Colonia brought together people from different places of origin (and therefore from different dialect areas) who had been employed in agriculture. Agricultural co-ops provided social and economic services, including education for children, Japanese-language newspapers, and meeting halls. Nihon imin 80nen-shi hensan iinkai (

Nihon imin 80nen-shi hensan iinkai [Committee for Compiling Eighty-Year History of Japanese Immigration to Brazil] 1991, pp. 245, 342, 385) recognizes that the

Colonia structure resulted in economic success, both through organizing cooperative associations and through mechanisms of internal social control which unified the population. Through the threat of social ostracism, membership in the associations was virtually compulsory.

Immigrants still recognized the authority of the Imperial Japanese government, in effect treating the

Colonia as virtual overseas colonies. The

Colonia educational system drew heavily from these Imperial sources (

Amemiya 1998). By 1938, the Japanese Ministry of Education, propagandizing nationalism and Emperor worship, was giving financial support to 187 Japanese schools with some 10,000 students. Thus, the pre-War era closed with an immigrant and Nikkei population concentrated in isolated communities with strong emotional ties to the homeland, and with strong community-internal expectations of like-minded thought and behavior. Tellingly, most immigrants in the pre-War period had no interest in assimilation; a 1938 survey of 12,000 households showed that 85% wanted to return to Japan (

Amemiya 1998).

It was not until Japan’s defeat in 1945 that the Nikkei began to question the orthodoxy of the Colonia system and to think of establishing themselves permanently in Brazil. Even then, this occurred only partially and gradually, and only after a period of strong intergenerational conflict which fundamentally divided the population. The difficult transition is illustrated by the reluctance of many immigrants to acknowledge the surrender of the Japanese armed forces.

Thus, for several years after the end of the War, perhaps as many as 100,000 Japanese immigrants and Nikkei refused to accept the fact of Japan’s defeat. According to

Amemiya (

1998), this was a result of the population needing to confirm an ethnic identity amid conditions of cultural isolation in a hostile environment, of self-interested wishful thinking, and of fraudulent activities by demagogues supported by violent, secret societies which tolerated no dissent and intimidated and assassinated those who thought differently. Eventually, most of the population did, of course, accept the fact of defeat, but for many, that did not mean a rejection of the idealized Japanese ethos, and a large part of the population attempted to maintain the pre-War

Colonia ethos.

Amongst the Nikkei population, there was, though, a change in their dream of “returning to Japan” in favor of “becoming good Brazilians”. This was reflected in an urbanization of the Nikkei

Colonia population. Individual post-War first-generation immigrants also followed this trend and settled in urban areas.

Nagata (

1990, p. 61) for example, discussed developments in Assai in the state of Paraná, one of the four largest

Colonia settlements. The period from 1947 to 1957 saw rapid development, and the early 1960s were considered its heyday, with the introduction of agricultural mechanization and higher standards of living and education. However, between 1957 and 1981, the population of Assai decreased by more than half, as families left agriculture for the comforts of urban life, exemplifying what Nagata calls “the split of Nikkei society”.

By the 1990s, a greater ethnic awareness had begun to emerge amongst the

sansei—the third generation Nikkei—and consequently, their interest in Japan and Japanese was revived (

Reichl 1995, p. 45). Since new Japanese immigrants have continued to arrive in Brazil, the degree to which Nikkei-Brazilians have assimilated into Brazilian society has never been entirely homogeneous. The movements of the

dekasegi also render the nature of the community more complex. By 1990, more than one in eight Nikkei had engaged in work in Japan (

Nagata 1990, p. 56).

3. Sociolinguistic Studies on Brazilian Japanese

There are a limited number of sociolinguistic studies in relation to Nikkei-Brazilians. One sociolinguistic theme that is often foregrounded in work on Japanese is the linguistic expression of politeness, yet the work carried out on this topic among Nikkei-Brazilians has tended to be impressionistic and anecdotal, with

Yamashita (

2007), however, providing the first statistical analysis of the use of polite language forms.

Nomoto (

1969, p. 73) suggests that rural Nikkei-Brazilian is “impolite” and attributes this to sociological conditions, including growing up “without respect” for others and “without spiritual refinement”, ignorant of polite language forms and their use. The economic conditions, he argues, did not leave them time or energy for the “niceties” of politeness, and they abandoned many of the polite language forms that are based on unequal social status, behaving linguistically as if everyone was of equal social rank.

In his study on Japanese language change in Brazil,

Suzuki (

1982, p. 104) also described rural Nikkei-Japanese as “impolite”, featuring a heavy incorporation of dialect from Western Japan and with a distinctive grammar and word usage. He noted the influence of Portuguese on accent and core vocabulary, an influence especially prevalent among children. Both he and

Kuyama (

2000) pointed to many loan words from Portuguese. The influence of language contact was age-related: The younger the generation, the greater the influence from Portuguese.

Handa (

1980, p. 79) mentioned that Nikkei-Brazilians were becoming poor at conveying special and sensitive emotion in Japanese.

Higa (

1974, p. 29), and a number of scholars subsequently, have argued that the standardization of the Japanese language in Hawaii was based on dialects from the

Chugoku district of Western Japan. This is also the case in Brazil, where migrants from Western Japan represented the dominant group of settlers.

Yamashita (

1999b, p. 11), using data from the dialect section of the questionnaire in the

Appendix A of this article, confirmed that Nikkei-Brazilian Japanese has its roots in the Western Japanese dialect, as well as confirming differences in dialect use between rural and urban Nikkei-Brazilians. The home language understandably greatly influenced the language of later generations. Many words adopted from the western district of Japan can be found in their common Japanese dialect, although the younger generations are not aware of this geographical origin.

Unsurprisingly, the language of the population mirrors its social upheavals. During the pre-War years, a diverse range of Japanese dialects could be heard in the community. However, some western dialects, such as Kumamoto, Fukuoka, and Yamaguchi, gradually emerged as the most influential (

Yamashita 2003). In line with

Mufwene’s (

1996, pp. 83–134)

founder principle, these dialects have the largest number of speakers and were the earliest to arrive

3—their emergence as dominant among Nikkei-Brazilians, then, not unexpected.

4. Defining Linguistic Variables: Types and Levels of Polite Language Forms and Spousal Address Terms

4.1. Types of Polite Language Forms

For the purposes of this study, it is important to understand what is meant by “polite language forms”, both culturally and structurally. In standard Japanese, the use of a polite or nonpolite language form is necessary in order to conform to social norms. The three major factors that control polite language usage are as follows: (1) the relative social position of the speakers; (2) in- or out-group membership; and (3) individual characteristics, the most important of which is gender but which also include age, family background, and other social variables (

Ono 1999, p. 153;

Minami 1974, p. 27)

Polite language forms are determined by the power relationship between the speaker, the listener and the topic person. The social level of the speaker is related to their role and status in the organization to which they belong. These factors are also related to age, gender, history of education, occupation, and so on.

Concerning in- or out-group membership, “in” refers to the speaker’s colleagues or family members. The target person who appears in a topic of a conversation is not always a companion in presence. When a speaker is talking, for example, about her own father (in-group) to unfamiliar guests (out-group), she uses the humble form (see below for the details). On the other hand, when the speaker is speaking about a guest (out-group) or a guest’s colleague (out-group) with an in- or out-group member, the polite language form is used. When talking directly to an in-group member, a speaker uses a casual speech style. In terms of gender, women tend to use polite language forms more than men. In practice, all of these factors combine and are processed simultaneously. Regarding the social rank of speakers, usually socially “lower-ranked” people use polite language forms when speaking to “higher-ranked” people, though the definitions of “higher” and “lower” are complex due to the interaction of the features described above.

Considering linguistic structures, the honorific system which linguistically encodes polite language forms has traditionally been divided into three categories. First, there is a standard polite form,

teineigo. The most important means of expressing politeness using

teineigo are (1) adding the polite copula -

desu to nouns and adjective, or (2) using the polite affirmative inflection-

masu, which is affixed to verb-stems derived from the plain (nonpolite) verb. For example, the

teineigo form of the verb ‘to say’, which has the plain form

hanasu, becomes

hanashi-

masu. Also included in the standard polite category are the noun-adjective-prefixes

o- and

go-.

4 Both prefixes can be used not only in

teineigo, but also in

sonkeigo and

kenjogo, which is explained in detail below.

Second, there is a humble form, applied to oneself,

kenjogo, which is realized through the use of either humble verbs or the so-called “productive honorifics”. For example, the humble form of the verb ‘to say’ may be expressed by means of a productive honorific (

o-

hanashi-

suru; that is,

o-

/go- is prefixed to the stem of the plain verb

hanasu further followed by the light verb

suru),

5 or the honorific humble verb,

mooshiageru, may be chosen.

Third, there is an exalting form, applied to others,

sonkeigo, which is also expressed through the use of either exalting verbs or, again, productive honorifics. For example, ‘to say’ may be produced as either

ohanashi-

ni-

naru (that is,

o-

/go- is prefixed to the plain verb stem

hanasu, further followed by

ni naru), or the exalting verb

ossharu may be chosen. However, the English words “exalting” and “humble” used here infer an extreme sense that does not, perhaps, accurately reflect Japanese usage.

Tsujimura (

1992, p. 446) highlights two concepts which interact across all categories of polite usage: first, addressee-related concerns, which differentiate speech on the basis of the familiarity of the speakers, and second, referent-related concerns, which require changes in speech according to the topic of the conversation. In practice, both addressee- and referent-related concerns operate together. These ideas are treated further in the Materials section, where they are applied to the questionnaire design.

4.2. Levels of Polite Forms

I adopted the National Language Institutes’ ranking system (

National Language Institute 1983, pp. 62–64) for the use of polite language forms. According to the Institute, there are 5 levels of polite language forms, where Level 5 indicates the politest, while Level 1 indicates the least polite. Level 5 concerns the maximally exalting (

sonkei-

go) and humble (

kenjo-

go) forms. As explained in

Section 4.1, both

sonkei-

go and

kenjo-

go have two ways either to show respect to the addressees or to express the speaker’s modesty (i.e., the use of either exalting/humble verbs or productive honorifics). At Level 5, where a speaker expresses maximum respect to the addressee’s or speaker’s modesty, however, each form is further followed by the polite affirmative inflection

masu. For instance, the verb

hanasu (meaning ‘say’) becomes either

osshai-

masu (i.e., the exalting verb,

ossharu ‘say’ followed by

masu) or

o-

hanashi-

ni-

nari-

masu (i.e., the productive honorifics,

o hanashi ni naru followed by

masu). However, it should be noted that not all verbs have exalting or humble forms; hence, for some verbs, there may be only one choice to show respect to the addressees or to be maximally humble oneself.

Level 4, the second highest level of politeness, concerns the use of passive forms as honorifics (i.e.,

re or

rare, the conjunctive forms of

reru or

rareru), which are followed by either the polite copula

desu or the polite affirmative inflection -

masu. The plain verb

ik-

u ‘go’, for instance, becomes

ika-

re-

masu. The verb

tabe-

ru ‘eat’ becomes

tabe-

rare-

masu. Interestingly, those

re and

rare forms are used more commonly in Western Japan than in other areas (

Inoue 2004, p. 158;

Sanada 1993, pp. 62–75). Sanada describes it is an ironic phenomenon; -

reru/-

rareru are not popular in Tokyo and are used rather in regional common languages, even though this form is simply regularly attached to all the verbs. Another example is introduced by the fact that “

kora-

reru” (exalting form of ‘come’) is more frequently used than “

irassharu” (exalting form of ‘go’, ‘come’ and ‘to be’ in common language) in western dialects. Such an influence of the Western Japanese dialect in Nikkei-Brazilian Japanese is evident.

Level 3, the middle level of polite language form, has two strategies. An example of the first usage is that the word ‘forget’ is expressed with the polite prefix o- followed by the plain verb wasureru ‘forget’ and further by the polite copula desu (i.e., o-wasure-desu). An example of the second usage is that the word ‘borrow’ is expressed as the polite prefix o- followed by the plain verb kas-u further followed by -kudasai, which is the imperative form of kudasaru, the honorific exalting verb kudasai ‘give’ (i.e., o-kashi-kudasai).

Level 2, the second lowest level of politeness, concerns the simple use of either the polite affirmative inflection -masu affixed to the plain verb or the polite copula -desu affixed to nouns or adjectives. The verb ik-u ‘go’ becomes iki-masu, while the verb taber-u ‘eat’ becomes tabe-masu.

Level 1, the least polite form, concerns the use of plain verbs without any polite suffixes or prefixes. When talking about yourself or your own family members to a friend, plain verbs are used. Plain verbs can be used when talking about others’ families when you do not have to show respect, but this is rather unusual. At Level 1, the verb taberu ‘eat’ is used as taberu (dictionary form of the verb ‘to eat’). This is in-group conversation, and a speaker uses a casual speech style.

The following are some examples from the questionnaire (Question 2.2); as shown below, each question does not always provide all five levels of politeness, since there are cases where some words simply cannot be used at a certain level of politeness:

You enter a restaurant with the president of your firm. How do you ask him or her what they want to eat?

- (1)

shachoo nani o meshiagari-masu-ka? (Level 5)

- (2)

shachoo nani o o-tabe-ni-nari-masu-ka? (Level 5)

- (3)

shachoo nani o tabe-rare-masu-ka? (Level 4)

- (4)

shachoo nani o o-tabe-desuka? (Level 3)

- (5)

shachoo nani o tabe-masu-ka? (Level 2)

- (6)

shachoo nani o taberu? (Level 1)

- (7)

If you wouldn’t use any of the answers in (1) to (5), then please write how you would say it.

4.3. Terms of Spousal Address

Address terms for spouses were included in this study, since they differ between Japanese and Brazilian Portuguese, as we will see. The address terms reflect respect or courteousness within a family. When you address your partner with ‘oi(hey)’, you may not ask your partner ‘oi, hon o totte kudasaimasen-ka?’ (Hey, would you mind taking that book?). There is a grammatical opposition of ‘você’ and ‘o (a) senhor (a)’ in Brazilian Portuguese, which corresponds to the verb usage of the second and the third person. ‘Você’ is used among friends or to address an intimate person, and ‘o (a) senhor (a)’ is used to address a person with higher social status or an older person. This parallels Japanese polite language forms. Nikkei-Brazilians basically speak Portuguese. It is important to analyze how people use address terms in Japanese when language contact between Japanese and Portuguese has occurred. Address terms are not only related to the usage of different levels of polite verb (i.e., polite or rude), but also to democratization and equality among family members.

In my questionnaire, the terms of spousal address were asked about as follows: “What does your wife (or husband) call you? If you are not married, how does your father (or mother) call your mother (or father)?” A number of possibilities were found. The first type involves such address terms as (o)kaasan ‘mother’ and (o)toosan ‘father’. These are the traditional terms when addressing one’s spouse in Japan, whereas the use of his or her name or a term of endearment such as “dear” is not common in Japan. Therefore, the first type is regarded as the most traditional and polite. The second type is the use of the first name, which is regarded as relatively less polite than the first type. The third type includes the terms Mama and Papa, which signal the modernization of the family after World War II and which were adopted into Japanese from English in both Japan and Brazil. The fourth type is the term bem ‘dear’—a loanword from Portuguese meaning ‘my dear’ or ‘my darling’. The fifth type includes Japanese vocative terms such as oi (a rather direct and rude ‘hey!’ often used by men socially more powerful than their addressees), and nee (a more egalitarian and friendly ‘hey!’ often used by women). The sixth type involves the terms (o)baa-san, (o)baa-chan (both meaning ‘grandmother’) and (o)jii-san, (o)jii-chan (both meaning ‘grandfather’). Since these forms of address are used when people criticize their spouses, such as pointing out their shortcomings, they are regarded as very impolite address terms. The seventh type refers to the use of Portuguese address terms, such as mamai, mãe (both meaning ‘mother’), and papai, pai (both meaning ‘father’). Although the third-generation are not accustomed to speaking in Japanese to their families, the use of these Portuguese words, nevertheless, reflects the way their parents address each other in Japanese—(o)kaasan ‘mother’ and (o)toosan ‘father’.

6. Results and Discussion

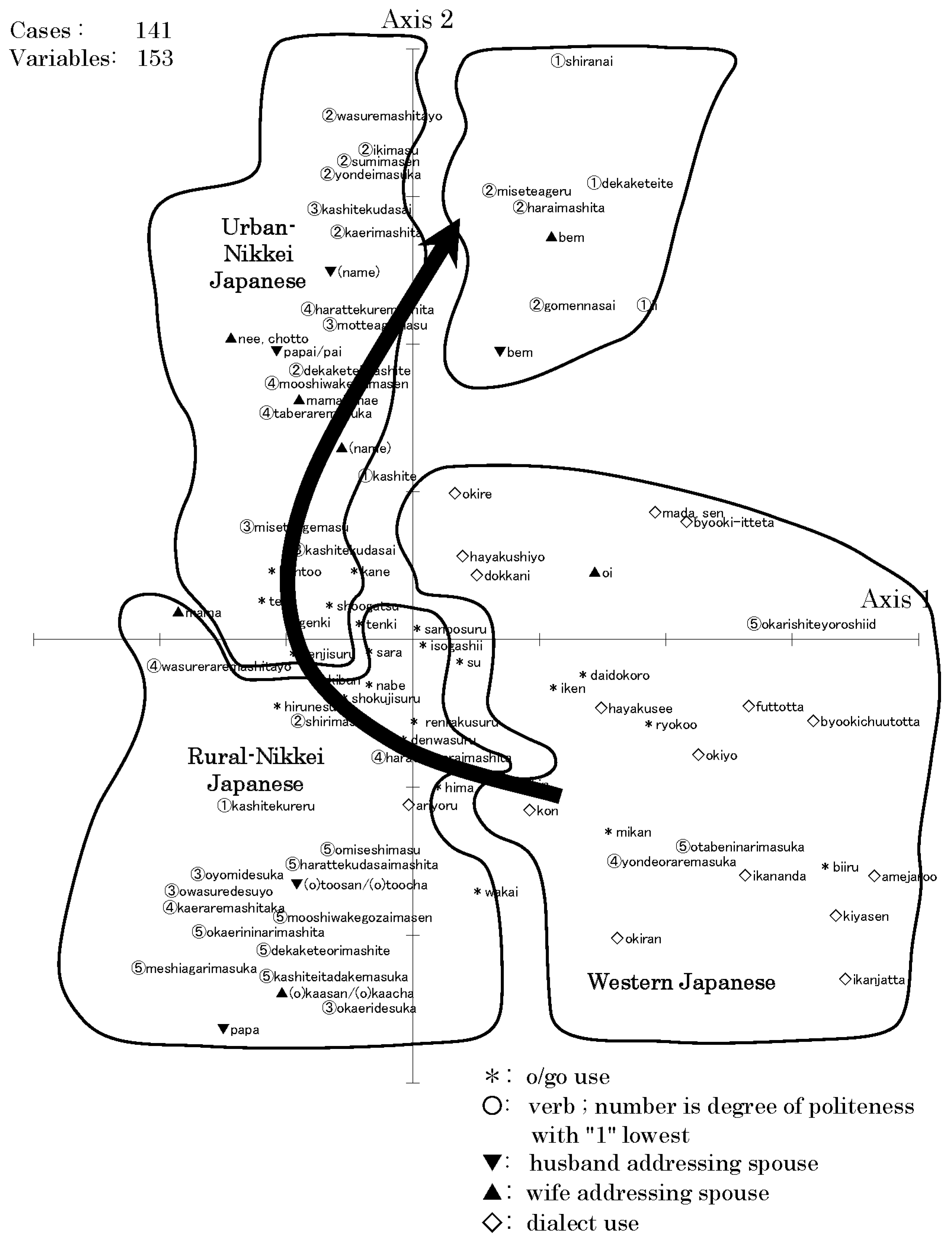

Figure 1 shows an overview of the changes in the Japanese language of Nikkei Brazilian society. The arrow drawn with a large curve in the figure indicates the direction of the big stream of change in Nikkei-Brazilian Japanese.

Importantly, four groups were identifiable in different positions on the plot.

8 WJ (Western Japanese), in the lower right, is the immigrant’s settlement point. As the majority of the first generation come from Western Japan, many western dialects (◇ indicate dialects use) are used in their Japanese. The group located in the lower right quadrant are native Japanese speakers from the western dialect-speaking area of Japan. Address terms include

oi (▼▲ indicate addressing), which can be said to be a rude expression from a husband to his wife. Many dialect forms were found in this area (see

Yamashita 2007), along with some polite expressions.

Second, the lower left is RNJ (rural Nikkei Japanese), which is spoken by mainly the second generation, living in a Nikkei society and using Level 5 and Level 4. The lower left group contains responses by second generation Nikkei-Brazilians who reside or had resided in the

Colonia.

9 Their specific linguistic characteristics include the use of spousal address terms, (

o)too-

san/

(o)kaa-

san ‘father’/’mother’ and

papa and

mama—both traditional and modern Japanese terms of address adopted from English to Japanese both in Japan and Brazil after World War II. In terms of politeness levels (○ verb; number indicates degree of politeness), they claimed to use levels as high as 5 and 4, including dialectal Western Japanese politeness forms -

reru and ˗

rareru, though their level of politeness as a whole spans the full range from 5 to 1.

The third group, UNJ (urban Nikkei Japanese), can be found in the upper left quadrant—responses by third-generation Nikkei-Brazilians residing in urban areas. Their common terms of address to their spouses included: (a) by name, which is common in Portuguese, but which would be odd in Japanese; (b) mamai, mãe/papai, pai, Portuguese words meaning ‘mommy’/‘daddy’ which are usually used by children when addressing their father and mother in Brazil but which would be odd between spouses. As the third generation is not accustomed to speaking in Japanese to their families, they have used these words from Portuguese in order to reflect the ways their parents addressed each other as in (o)kaasan ‘mother’ and (o)toosan ‘father’. Regarding the level of politeness, their use was restricted to Levels 2 and 1, where -desu and -masu forms are mainly used. They do not use exalting nor humbling forms but the polite language forms -desu, -masu and the final particle -ne. Using the final particle -ne compensates somewhat for the lack of exalting/humbling verb use, even though -ne is not polite enough to express consideration to others. The greater use of standard polite -desu, -masu forms is based on the relative distance between the speaker and the listener, rather than hierarchical relationships.

The fourth group in the upper right quadrant indicates the language use of fourth- and fifth-generation Nikkei-Japanese. Language use among this group differs dramatically from the urban and rural Colonia Nikkei-Japanese. Commonly used expressions such as gomenasai ‘I am sorry’ (Level 2), shiranai ‘I don’t know’ (Level 1), and bem ‘my dear’ as a term of address can be found.

I now turn to recap the characteristics of both rural Nikkei-Japanese and urban Nikkei- Japanese (see

Table 1). The honorific passive forms -

reru and -

rareru, preferred by the

Colonia Nikkei-Brazilians, are forms of respect used for addressees, and especially elders; hence, it can be said that the users still maintain traditional Japanese language order. On the other hand, the use of combinations of -

desu or -

masu with the final particle -

ne by urban Nikkei-Japanese can be interpreted as a preference for distance-reducing expressions or emphasizing closeness, common in Brazilian society. The results reiterate, then, that those who live in exclusively Japanese communities maintain more traditional Japanese politeness forms (including Western Japanese dialectal forms) and terms of address, while those who left the

Colonia seeking a more liberal urban lifestyle show some influence from Portuguese in the use of

papai,

pai ‘father’ and

mamae,

mãe ‘mother’, while displaying limited linguistic repertoires in politeness forms.

There seem to be four factors contributing to the emergence of two different varieties among Nikkei-Brazilians. The first factor is the availability of Japanese language education. Teaching in schools exclusively through the medium of Japanese was banned in 1938, as were Japanese-language media. From 1972 to 1995, however, there was a large increase in the number of

nisei and

sansei learning Japanese, due both to new educational policies, which lifted the ban on Japanese language education, and the influx of investment from Japanese companies. Although standard Japanese was taught in schools both in the rural Colonia and urban areas, students could also “acquire” Japanese through socializing in the community where the older generations still use western dialects of Japanese. It therefore makes sense that the variety of Japanese used by the second generation in rural areas shows some influence from the western dialect; by contrast, in urban areas, the mother tongue for the third generation has become Portuguese—the dominant ambient language. These urbanites learn Japanese either through their parents or Japanese classes, but not through community or social life. Hence, the variety of Japanese used by the third generation in urban areas shows the incorporation of Portuguese as well as standard final particle -

ne, but little influence from Western Japanese dialects.

10The second factor is the effect of contact with Portuguese.

11 Firstly, the use of Portuguese forms of spousal address provides evidence of the incorporation of Portuguese words into urban Nikkei-Japanese, likely hastened by the adoption of Portuguese as a mother tongue. Second, given that the final particle -

ne compensates somewhat for the lack of exalting/humbling verb use, it can be speculated that distance-reducing expressions, common in Brazilian society, are preferred rather than respectful and courteous/polite expressions. That is, there was a shift from showing deference to demonstrating solidarity. Thus, this has strong influence on the formation of their variety of Japanese.

The third factor is related to the process of social levelling in an isolated pioneer or rapidly changing society.

12 In this light, the pressure to conform to Japanese social norms was weaker, particularly in urban areas, and consequently, Portuguese words and Brazilian politeness strategies (i.e., using -

ne to show friendliness and distance reducing) were more readily incorporated than traditional Japanese politeness strategies (i.e., using respectful and courteous/polite expressions).

Finally, the effects of socioeconomic shifts from a rural to an urban environment are another possible cause for the changes described above, since through this relocation, nisei and sansei typically gained social status, engaged in the operation of small businesses, thus requiring extensive contact with the public, joined Japanese international companies, and worked abroad.

Historical sociolinguists would hope to be able to trace the language development of urban Nikkei-Japanese chronologically, for example, from the Western Japanese dialect, to rural Nikkei and then to urban Nikkei. To do so reliably would, however, require a comparative analysis of language studies regarding Western Japan 100 years ago, the Japanese living in the Colonia more than 50 years ago, and modern urban Nikkei. Regretfully, such historical studies are beyond the scope of this present study. However, further comparisons of rural Nikkei-Japanese and urban Nikkei show many differences, adding weight to the idea that a new language order is emerging.