Abstract

Two fundamental aspects of conceptual and linguistic structure are examined in relation to one another: organization into strata, each a baseline giving rise to the next by elaboration; and the conceptions of reality implicated at successive levels of English clause structure. A clause profiles an occurrence (event or state) and grounds it by assessing its epistemic status (location vis-à-vis reality). Three levels are distinguished in which different notions of reality correlate with particular structural features. In baseline clauses, grounded by “tense,” the profiled occurrence belongs to baseline reality (the established history of occurrences). Basic clauses incorporate perspective (passive, progressive, and perfect), and since grounding includes the grammaticized modals, as well as negation, basic reality is more elaborate. A basic clause expresses a proposition, comprising the grounded structure and the epistemic status specified by basic grounding. At higher strata, propositions are themselves subject to epistemic assessment, in which conceptualizers negotiate their validity; propositions accepted as valid constitute propositional reality. Propositions are assessed through interactive grounding, in the form of questioning and polarity focusing, and by complementation, in which the matrix clause indicates the status of the complement.

Keywords:

complementation; disjunction; finite verb; focusing; grounding; modal; negation; negotiation; proposition; speech act 1. Introduction

I will be examining two fundamental aspects of conceptual and linguistic structure in relation to one another: a general feature of cognition I refer to as B/E organization (Langacker 2016); and a cognitive model representing our conception of reality. Together they allow a cogent description of central features of English clause structure.

Linguistic structure tends to be organized in successive levels (or strata), each a baseline (B) giving rise to the next by elaboration (E). The higher stratum incorporates additional resources affording a wider array of structural options. For instance, from a baseline vowel system [i e a o u], representing one stratum (S0), the added resource of nasalization yields the elaborated system [[i e a o u] ĩ ẽ ã õ ũ] at a higher stratum (S1). A noun and its corresponding plural belong to different strata: conceptually and formally, dogs elaborates the baseline expression dog. The conception of one represents the default and the point of departure for conceiving of more than one.

What I mean by reality is not based on physics or philosophy, but on human experience as reflected in language structure. It is not limited to what we call the “real world,” nor to physical or observable entities. For example, all of the following count as being “real” for present linguistic purposes: fictive worlds (Santa Claus is fat); abstract entities (pi is an irrational number); social and cultural notions (religious freedom is guaranteed by the constitution); products of metaphor and blending (we’re drowning in red ink); generalizations (a tiger has stripes).

I suggest that relevant aspects of English clause structure are revealingly described in terms of a cognitive model reflecting fundamental aspects of pre-linguistic experience (Langacker 2013, p. 15): “According to the reality model, affairs in our world have unfolded in a particular way, out of all the ways conceivable. There has been a certain course of events, whereby certain events and situations have occurred, while countless others have not. Reality (R) is the history of occurrences, up through the present moment. This history cannot be changed; what has happened has happened. Reality is thus the established course of events. Future events are excluded from reality (so defined) because they have not yet occurred and thus have not been either established or fully determined. Moreover, our knowledge of reality is only partial and imperfect. Each of us has our own “take” on it, our own reality conception (RC). For a given conceptualizer (C), RC comprises what C accepts as real—i.e., as having occurred, or having been realized. This conception is always incomplete, and C is bound to be mistaken in many respects. But rightly or wrongly, RC is what C knows.”

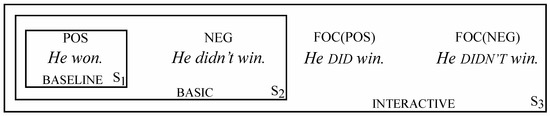

Specific linguistic properties motivate the assignment of clauses to three main strata involving different levels of reality: baseline clauses and reality (e.g., Alice resembles her mother, Sam broke a cup); basic clauses and reality (she may have been followed, he didn’t graduate on time); interactive clauses and propositional reality (he did graduate, have they left?). These will be considered in turn.

2. Baseline Level

The description is based on Cognitive Grammar (Langacker 2008), which holds that grammar is inherently meaningful, residing in assemblies of symbolic structures (form-meaning pairings). For basic universal categories, like noun and verb, the framework posits both a schematic meaning, valid for all members, and a prototype corresponding to central members (Langacker 2015a). The prototypes are experientially grounded conceptual archetypes: objects in the case of nouns, and events for verbs. The schemas reside in basic cognitive abilities inherent in the conception of objects and events: for nouns, the grouping of entities into one; for verbs, tracking a relationship through time. Conceptual archetypes—notions like object, event, substance, force, time, space, location—serve as a baseline for cognitive and linguistic development. The conceptual motivation of grammatical structure is thus most evident at this level.

2.1. Existence

We say that objects exist, whereas events occur, but I view these as manifestations of the same abstract notion: just as objects reside in the spatial existence of substance, events reside in the temporal existence of relationships. Also existing in space, and coded by nouns, are entities such as people, substances, and features of the spatial surroundings. Existing through time, and coded by verbs, are not only events but also states—stable relationships conceived as extending through time without inherent limit.

Just for the sake of discussion, we can identify baseline reality with entities that exist in space and time. What counts here as reality (R) is conceived reality as reflected in language. R is a structure: an immense assembly of entities connected via relationships. This structure is dynamic, continually evolving through time; notably, it “grows” as the passage of time brings new events. These events unfold within a relatively stable framework comprising those facets of R which endure through time. This includes both states and objects (for which endurance is the default expectation). An object’s persistence through time is itself a kind of state. Thus reality, characterized above as the established history of occurrences, can also be described as the totality of what has existed.

Objects are coded by nouns, events and states by verbs. An expression’s category depends on its profile: the entity it designates (or refers to), hence the focus of attention within the conceptual content invoked. A noun refers to a thing, prototypically an object (it is characterized schematically as a grouping conceived as a single entity). Its profile is the object per se, whose existence through time is merely presupposed. With verbs, on the other hand, evolution through time is an essential feature. A verb profiles an occurrence (or process), i.e., a relationship followed through time. Occurrences include both events and states. It is important in what follows that the existence of a relationship—its evolution through time—represents the schematic meaning of a verb.

2.2. Substrate and Structure

An expression’s meaning is never self-contained. It emerges from an elaborate conceptual substrate, including background knowledge, the object of discussion, the speech situation, and the ongoing discourse. We can recognize different strata (levels of organization) based on the complexity of expressions and the conceptual resources they demand. The initial stratum corresponds to baseline clauses, such as Alice resembles her mother or Sam broke a cup. Their structure reflects an implicit scenario for language use in its simplest, most canonical form.

In this scenario, there are two interlocutors, a speaker (S) and a hearer (H). The interlocutors and their immediate circumstances constitute the ground (G). In the baseline viewing arrangement, S and H are together in a fixed location, from which they observe and describe actual occurrences in the world around them. Their interaction consists of baseline speech acts: statements presumed to be valid. A baseline usage event is one such instance of language use; the expression produced is a single baseline clause, which describes some aspect of baseline reality.

A baseline clause has just a few essential elements: a verb, which profiles an occurrence; one or more nominals, describing its participants; and tense to indicate location in R. It is minimal because the substrate incorporates default values for numerous features. Among the things absent are modals, negation, indications of speech act, multiclause expressions, and connected discourse. Departures from the baseline, being conceptually more complex, come about through structural elaboration at higher strata.

A full clause represents the structural implementation of two basic semantic functions: description of the profiled occurrence; and grounding (how it relates to the ground). Description starts with a lexical verb (like see, resemble, run, or break), which specifies a basic type of occurrence—one schematic regarding its participants. Their specification by nominals produces an elaborated type, such as Alice resemble her mother or Sam break a cup. Grounding by tense then yields a clause: Alice resembles her mother; Sam broke a cup. Due to grounding, the profiled occurrence is conceived as an instance of the higher-order type, distinguished from other instances by its temporal location.

Grounding pertains to the epistemic status of the profiled thing or occurrence: how it relates to what the interlocutors purport to know. For nominals, the main epistemic concern is identification of the referent. For clauses, the main concern is existence, or the referent’s status vis-à-vis reality. Since the baseline scenario specifies that the interlocutors observe and describe actual occurrences in the world around them, their reality is presupposed.

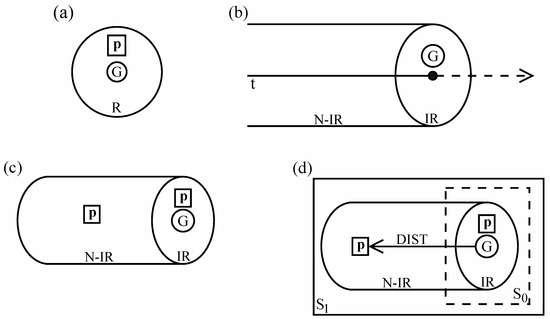

So as shown in Figure 1a, the baseline scenario locates p, the profiled occurrence, in reality (where G is also found). In Figure 1b, R is depicted as a cylinder that “grows” through time (t). The “face” of this cylinder, representing R’s manifestation at the current moment, is referred to as immediate reality (IR). The remainder of R is non-immediate reality (N-IR). Thus p can either be immediate to G (in IR) or non-immediate (in N-IR), as in Figure 1c. Since reality is taken for granted at this stratum, and the time of speaking is a facet of G, immediacy vs. non-immediacy to G translates into present vs. past in time—the prototypical value of the so-called “tense” markers (resembles vs. broke). This correlates with the experiential factor of whether the occurrence can be observed directly or only via memory. Accordingly, the arrow in Figure 1d indicates that prior occurrences lie at a certain distance (DIST) from G both temporally and experientially. And memory being an additional conceptual resource, they also represent a higher stratum. Thus grounding at the baseline level (a main stratum) can itself be differentiated into substrata, with S1 representing an elaboration vis-à-vis S0.

Figure 1.

Grounding in baseline reality.

3. Basic Level

Basic clauses elaborate the baseline in regard to both description and grounding: for description, by means of perspectival adjustments; and for grounding, in the form of grammaticized modals.

3.1. Perspective

The perspectival adjustments are effected by passive, progressive, and perfect constructions. The passive affects the choice of subject by conferring that status on the participant that would otherwise be the object: expect > be expected. The progressive restricts the profiled occurrence to an internal portion of the occurrence profiled by the verb: cry > be crying. The perfect describes a state in which the verbal occurrence is apprehended from a reference point later in time: finish > have finished. Each construction is complex, involving two levels of composition. At the first level, a verb is elaborated morphologically to derive a participle: a so-called “present participle” (crying) or a “past participle” (expected, finished). Though derived from a verb, a participle does not itself function as such; grammatically it is more like an adjective (cf. crying baby, expected outcome). At the higher level, the participle combines with a schematic verb, be or have. They function as heads in these constructions by imposing their verbal nature on the content supplied by the participle. The result in each case is a complex verb describing an occurrence apprehended from a certain perspective, as determined by the participial element.

Reflecting their common perspectival function, these constructions are parallel in formation and mutually exclusive, in that only one can be used with a given verb; they constitute a system of opposing elements. When they co-occur, it is only because the “output” of one construction—being a complex verb—can itself participate in another. The conventionally established combinations are listed in (1). Each construction elaborates a verbal expression to form a more complex verbal expression at a higher level of organization. The lower-level expression is either the lexical verb (like watch) or a complex verb resulting from prior elaboration (e.g., be watched). The higher-level expression comprises be or have followed by a simple or complex participle (e.g., watching, being watched) that incorporates perspective.

| 1. | a. | PASSIVE > PROGRESSIVE: | watch > be watched > be being watched |

| b. | PASSIVE > PERFECT: | watch > be watched > have been watched | |

| c. | PROGRESSIVE > PERFECT: | watch > be watching > have been watching | |

| d. | PASSIVE > PROGRESSIVE > PERFECT: | watch > be watched > be being watched | |

| > have been being watched |

As schematic verbs, be and have profile the existence of a relationship—its evolution through time—but do nothing to specify its nature. They serve to convert the participial expression into a complex, higher-order verb in which the relationship followed through time is the one coded by the participle. The profiled occurrence is thus distinct from that of the lexical verb. For example, watch and be watching have the same descriptive content but profile different occurrences: the full event vs. an internal portion of it. At each stratum, one verb functions as head in the sense that the occurrence it profiles is profiled by the full verbal expression. In (1), boldface indicates the head at each level: the lexical verb, be, or have. The occurrence profiled by the highest-level head is the one whose epistemic status is specified by grounding—the one labeled p in Figure 1. The highest-level head is thus the grounded verb, and the full verbal expression represents the grounded structure. In baseline clauses, the grounded verb is just the lexical verb: She watched him. But in basic clauses with perspectival adjustments, these functions are differentiated: She had been watching him.

Not every basic clause has a lexical verb. A frequent alternative is the combination of be with an adjective or a prepositional phrase: The cat is {ugly / on the mat}. Adjectives and prepositions profile relationships, but they are not verbs because they do not focus on its evolution through time; the situation they describe is fully manifested at a single instant (and can thus be observed in a photograph). Their combination with be reflects the conceptual characterization of a verb: that it profiles a relationship followed through time. It differs from a lexical verb only in that the relationship and its tracking through time are expressed by separate elements. It can also be recognized as a variant of the perspectival constructions. The difference is that it creates the functional equivalent of a lexical verb, whereas a perspectival construction starts with such a verb.

3.2. Modality

Perspectival constructions represent one dimension of elaboration leading from baseline clauses to basic clauses. Another dimension is the elaboration of grounding to include modality. This introduces a higher level of reality.

At issue are the grammaticized modals may, will, can, shall, must, might, would, could, and should. These function as grounding elements, occurring in lieu of tense (e.g., likes/liked vs. will like/would like). The modals exhibit B/E organization. In terms of both form and meaning, the basic forms may, will, can, and shall constitute the baseline, being elaborated by the distal forms might, would, could, and should. We will not be concerned with their many idiosyncrasies, focusing instead on what they have in common.

I follow Talmy (1988) and Sweetser (1990) in viewing modals as force-dynamic in nature (Langacker 2013). With an effective (or “root”) modal use, the force (⟹) has a potential effect on the evolution of reality. It is often a matter of permission, obligation, or ability. Here we will consider only epistemic modal uses, which pertain to speaker knowledge. The force is internal to the conceptualizer (C): the mental effort involved in projecting the growth of R along a path that results in p’s incorporation. It reflects C’s assessment of the likelihood of p being realized. This ranges from mere potential (he may be angry) to virtual certainty (he must be angry).

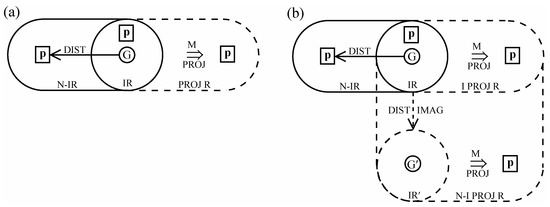

The basic modals (M) elaborate the baseline grounding system as shown in Figure 2a. They afford a wider range of options, allowing both real occurrences and those whose realization can be projected (with varying degrees of confidence). In contrast to baseline grounding, where p is limited to R, a modal specifically removes it from R. Reality is still at issue since the modal projection envisages p as part of an updated reality conception. We can therefore recognize a higher, more inclusive level of reality that encompasses not only baseline reality (R) but also projected reality (PROJ R). At this higher stratum reality comprises both the established course of events and the projected course of events.

Figure 2.

The grounding system with basic and elaborated modals.

In a finer-grained description, represented in Figure 2b, projected reality can be differentiated into substrata in just the same way that baseline reality is. The notion of distance (DIST) divides projected reality (PROJ R) into immediate projected reality (I PROJ R) and non-immediate projected reality (N-I PROJ R). This distinction reflects the semantic contrast between the basic modals may, will, can, and shall and their elaborated (distal) forms might, would, could, and should. Despite their semantic idiosyncrasies, the latter consistently specify a greater epistemic distance from G—a longer epistemic path—than their basic counterparts. Note the examples in (2): would and could contrast with will and can by being counterfactual; might contrasts with may by indicating a more tenuous possibility; and while shall represents a command, should just describes an obligation.

| 2. | a. | I will if I can vs. I would if I could. |

| b. | He may be home—the lights are on. vs. He might be home, but the lights aren’t on. | |

| c. | You shall do that. vs. You should do that. |

The distal modals invoke an additional conceptual resource: imagination (IMAG). The modal projection is not made from the actual ground (G) in immediate reality (IR). Rather, the speaker imagines a somewhat different situation, G′ (as part of IR′), from which the projection indicated by the basic modal form would be appropriate. There is thus a longer epistemic path from G to p. As seen in (3a), a basic modal locates p in a single step; starting from immediate reality (IR), where he is not poor, will directly places p in immediate projected reality (I PROJ R). By contrast, a distal modal proceeds indirectly by first invoking an imagined situation, IR′, distinct from IR in some respect. In (3b), the actual situation (in IR) is that he is poor. From there, the path to p proceeds in two steps reflecting the status of would as the distal form of will. First, imaginative distancing (--->) induces the fictive conception (IR′) of his not being poor. And from that situation, the modal projection of will leads to p, placing it in non-immediate projected reality (N-I PROJ R).

| 3. | a. | Since he is not poor, she will marry him. | |

| [he is not poor (G/IR)] ⇒ [she marry him (I PROJ R)] | |||

| b. | If he were not poor, she would marry him. | ||

| [he is poor (G/IR)] ---> [he is not poor (G’/IR′)] ⇒ [she marry him (N-I PROJ R)] | |||

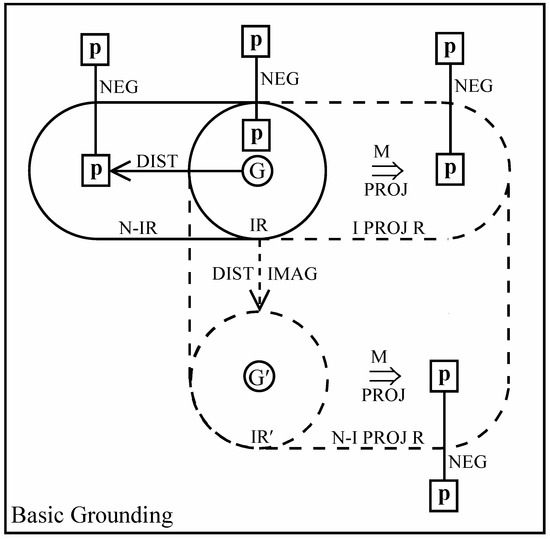

3.3. Finite Verb

Figure 3 summarizes the grounding options discussed so far. p is the profiled occurrence whose epistemic status is specified by tense and modality. We can take this to be the grounded structure as a whole, or more specifically its head, the verb which imposes its profile on that structure. Dashed arrows represent the epistemic path leading from G to p, each step residing in either distancing (DIST) or projection by a basic modal (M). Strata are labeled based on the length and nature of the path: at S0, immediacy to G amounts to a path of zero length; S1 and S2 involve alternate one-step paths; and in S3 we have the two-step path of a distal modal. The options in S1 constitute the baseline grounding system, and those in S3, the basic grounding system.

Figure 3.

Summary of the basic grounding system.

In baseline clauses, the lexical verb functions as head (p). It is therefore the grounded verb, the one on which epistemic status (immediacy) is registered (she watched him). In basic clauses, the functions of lexical verb and grounded verb are differentiated (she had been watching him), since the highest-level head is a schematic verb: have, be, or do. A key to the verbal organization of English clauses is a further, subtle distinction between the grounded verb and what is traditionally called the finite verb (Langacker 2015c). The finite verb is the one marked for “tense.” More specifically, it is the verb word which registers immediacy—whether the profiled occurrence is immediate or non-immediate to the ground. (Why a word? Because word order plays a role in grounding at higher strata.) When there is no modal, the finite verb is the tense-marked form of the grounded verb, e.g., had in the clause he had finished. In this case have is the grounded verb by virtue of being the highest-level head in the grounded structure (he have finished). Grounding is marked on this verb, resulting in had, which is the finite verb because it is a word specifying the non-immediacy of the occurrence it profiles.

A modal changes this picture because it qualifies simultaneously as a word, a grounding element, and a head. Forms like may, will, could, and should are clearly words. They belong to the grounding system because their function is not to describe an occurrence but to indicate its epistemic status. And they qualify as heads because they profile an occurrence that is also profiled by the clause as a whole.

As characterized in Cognitive Grammar, highly grammaticized grounding elements profile the grounded entity, rather than the ground or the grounding relation (Langacker 2002). The conceptual structure of a modal is thus as follows, where p is a fully schematic occurrence related to G by the modal projection: [G ⇒ p]. Because it profiles an occurrence, a modal is itself a verb. When it combines with a grounded structure, the schematic occurrence it profiles is identified with the specific occurrence profiled by the latter. So in the clause he may work, the modal and the lexical verb refer to the same event, providing schematic and specific descriptions of it. A modal is thus a head because it profiles the same occurrence as the clause. It is in fact the overall head, being introduced at the highest level of organization.

It follows that a modal, when it occurs, functions as the finite verb in its clause. In addition to being the highest-level head, it is the word that registers immediacy or distance (e.g., may vs. might). When there is no modal, the grounded verb functions as the finite verb, e.g., had in he had been working. But a modal comes in at a higher level of organization, so when one occurs, it takes over this function: he might have been working. In this case the roles of grounded verb and finite verb are differentiated: whereas have is still the grounded verb (and work the lexical verb), the finite verb is now the grounding modal.

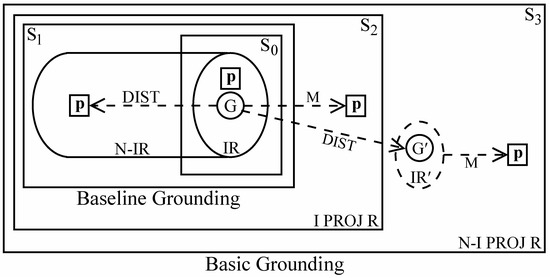

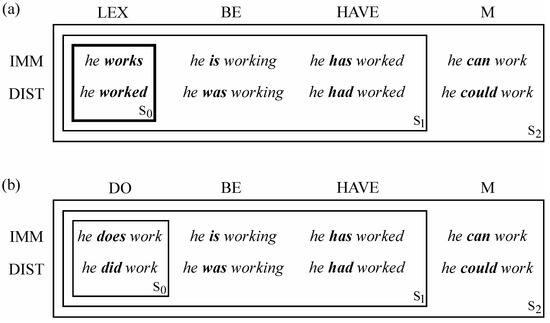

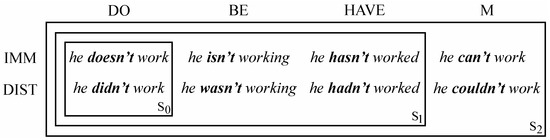

In Figure 4, I summarize the basic options for the finite verb in an English clause. The finite verb is given in bold, with he work as the type of occurrence, and can representing the modals. In 4(a), the simplest case, S0, is that of a baseline clause, where the finite verb is just the lexical verb (LEX). The other two strata correspond to basic clauses. At S1, involving perspectival constructions, the finite verb is be or have. At S2 a modal (M) serves in this capacity. Figure 4a,b are the same apart from S0, where do replaces work as the finite verb. This constitutes an elaboration, since do adds another level of formal and conceptual complexity (e.g., he does work instead of just he works). But it also simplifies matters in that Figure 4b represents a neat paradigm exhibiting a basic regularity: in each case the finite verb is highly schematic. Within Figure 4b, S0 is still the initial stratum, since do is conceptually simpler than be, have, or M, which incorporate aspectual, perspectival, or modal import.

Figure 4.

Summary of options for the finite verb.

The “auxiliary” verb do is maximally schematic: it merely profiles an occurrence (a relationship followed through time), making no specification concerning its nature. Its schematic meaning is inherent in every lexical verb, so when they combine, the composite meaning is equivalent to that of the lexeme (e.g., do + work = work). Equivalent but not identical. Since the two verbs profile the same occurrence, characterized in schematic and specific terms, do reinforces the notion of existence, making it more salient than when the lexical verb is used alone. Do is thus employed in just those cases where existence is not simply taken for granted but is considered in relation to other options (e.g., either he did work or he didn’t work).

4. Negation

Negation is an obvious case where existence is considered in relation to other options. So instead of the lexical verb, it is marked on a schematic finite verb whose function is to impose or reinforce the notion of existence. When present, be, have, or a modal serves this function. Otherwise, do is invoked. That negation combines with these verbs, usually in the form of contractions, attests to their basically existential import. Formally and conceptually, the examples in Figure 5 elaborate the expressions in Figure 4b. Negative clauses of this sort can thus be regarded as a higher-level substratum within the stratum of basic clauses.

Figure 5.

The finite verb elaborated by negation.

4.1. Dynamic Characterization

Negation nicely illustrates a basic notion of Cognitive Grammar: that language structure consists in activity, occurring at different levels and on different time scales. On the smallest time scale, it consists in patterns of neural activation. On a much larger time scale, it consists in the interactive activity of interlocutors. Structure thus has a time course, unfolding through time in a certain manner. Obvious at the phonological pole, this is no less true of the conceptual structures constituting linguistic meaning. Though complex and sometimes variable, the time course of conception always contributes to an expression’s meaning and is often essential to its value. It is essential to negation, which resides in the sequenced evocation of conceptions.

It is often observed that a negative expression presupposes its positive counterpart. Since it conveys the absence of some entity, it can only be apprehended in relation to a conception where it is present (which serves to indicate what is missing). Negation can thus be thought of as an operation which evokes one conception as the basis for arriving at another by suppressing one of its elements (Langacker 2016). Negation is thus a case of B/E organization (suppression being one kind of elaboration).

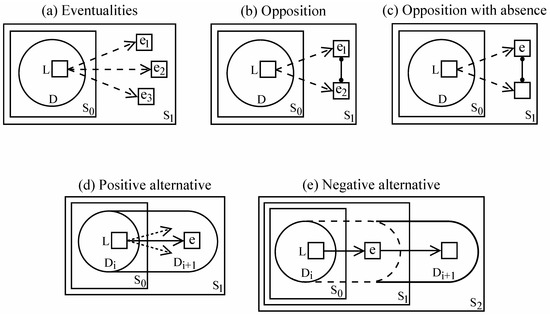

Negation has many possible targets, e.g., quantity (no water), property (uneven), type of thing (non-argument), and existence (lack, missing, empty). I start in Figure 6 with a general characterization based on fundamental aspects of cognition. Let us say that a particular conception, at a given moment, constitutes a domain (D). Any facet of D can be the locus (L) of processing activity serving to update it in some respect. This constitutes elaboration (L being the baseline). From this initial stratum (S0), alternate paths of elaboration—referred to here as eventualities (e)—define a higher stratum (S1) comprising a wider range of options. For instance, D might be the conception of a table, and L the specification of its shape. The eventualities are then an array of conceivable shapes (e.g., round, square, rectangular, octagonal). When alternatives are incompatible (e.g., round vs. square), their relation is one of opposition, indicated by the notation in Figure 6b. In processing terms, they consist in patterns of activity that inhibit one another. And as shown in Figure 6c, there is always an implicit opposition between a given eventuality and its absence (so that L is the same at S0 and S1).

Figure 6.

Negation as conceptual elaboration.

Viewed in dynamic terms, the elaboration of L serves to update D in some fashion. Updating consists in the transition (mental progression) from Di to Di+1. In Figure 6d, a solid (as opposed to a dashed) arrow represents the elaborative option actually chosen, e.g., table > round table. As shown in Figure 6e, a positive alternative is the basis for the corresponding negative alternative. This involves an additional elaborative operation resulting in a higher stratum (S2). Its effect is to override (or suppress) the positive alternative evoked at S1. L is thus the same at S0 and S2, but in Di it is accessed directly, whereas its apprehension in Di+1 includes an elaborative path invoking the positive alternative.

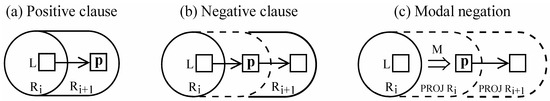

4.2. Clausal Negation

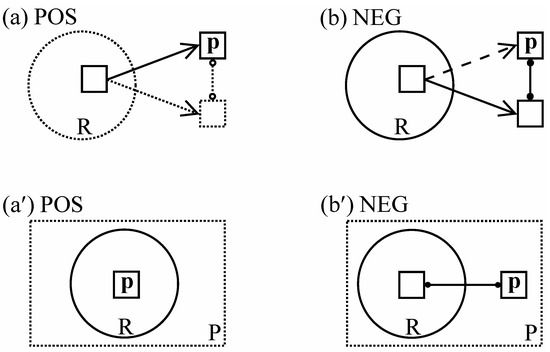

Clausal negation is a special case of the general characterization in Figure 6e. As seen in Figure 7a, the domain (D) is some level of reality (R), the positive eventuality (e) being the occurrence profiled by the finite verb (p). Because it pertains to p, negation is marked on that verb; as an indication of p’s epistemic status, it is an aspect of clausal grounding. A positive statement updates a conception of reality (Ri) in such a way that the updated version (Ri+1) includes the profiled occurrence (p).

Figure 7.

Clausal polarity options.

In Figure 7b, its negative counterpart, the reality of p (its location in R) is merely provisional (or virtual); it is invoked as a basis for arriving at the actual situation, where it is absent from Ri+1. In the case of modals, shown in Figure 7c, what counts as reality is PROJECTED REALITY (PROJ R). So the updated conception—where p is absent—pertains to PROJ Ri+1.

Negation expands the basic grounding system to include the negative counterparts of all the options in Figure 2. This elaborated system is shown in Figure 8. It indicates the possible locations of p in the epistemic landscape at this stratum. Each grounding option resides in an epistemic path from G to p. With negation, that path proceeds through the virtual situation where p has the epistemic status specified by tense or modality. So negation does not affect that status per se—e.g., she didn’t complain still pertains to past reality—but merely suppresses the conception of p at that location.

Figure 8.

The basic grounding system with negation.

5. Interactive Level

We turn now to a higher level of organization, where the proposition (P) expressed by a finite clause is subject to negotiation by the interlocutors. This negotiation is another kind of grounding pertaining to another level of reality. I refer to these as interactive grounding and propositional reality (PR). Two dimensions of interactive grounding will be considered: polarity and speech act.

5.1. Propositional Reality

A finite clause grounds the profiled occurrence (p) by placing it in some region of basic reality, e.g., non-immediate projected reality (N-I PROJ R) for it might rain. An essential point is that reality is always a reality conception, as entertained by some conceptualizer (C). But who is this conceptualizer? The default assumption is that C is the current speaker and that the clause reflects her actual view. This is not, however, an inherent or necessary feature of the clause itself, but depends on the conceptual substrate it presupposes. Instead of the baseline substrate, many uses invoke an alternative in which the clause does not reflect the speaker’s actual view. It might, for instance, be a lie (such as most any statement by Donald Trump). Or intended ironically (e.g., that was brilliant to describe a stupid mistake). It can represent a quotation or a paraphrase of someone else’s opinion, as in (4a). In a subordinate clause, the status of p depends on the structure it is embedded in, as in (4b–d).

| 4. | a. | Climate change is a hoax, according to Trump. |

| b. | It’s just not true that Trump is brilliant. | |

| c. | Pence believes that Trump is brilliant. | |

| d. | If Trump is brilliant, he hides it well. |

I will say that a finite clause expresses a proposition (P), defined as consisting in a profiled occurrence together with its basic grounding: P = [Basic Grounding + p]. The identity of C, who makes the grounding assessment, depends on the substrate. In and of itself, a proposition is independent of any particular conceptualizer. It can thus be apprehended by different conceptualizers, each with their own reality conception and their own assessment of p’s epistemic status. Their assessment need not conform to C’s (the one indicated by basic grounding).

For propositions we have to recognize a higher level of epistemic assessment involving a higher level of reality. The issue at this stratum is not the realization of p (whether an event occurs), but rather the validity of the proposition P: whether the assessment of p (as conveyed by basic grounding) is accepted as being accurate by the conceptualizer who entertains the proposition. For example, in (4b) the subordinated proposition (Trump is brilliant) is judged by the speaker to be invalid. On the other hand, in (4c) Pence is responsible for that proposition and thus accepts it as being valid.

For a given conceptualizer, the set of propositions accepted as valid constitute propositional reality (PR). One proposition we can all agree to is that PR is different for every individual. A proposition’s validity is thus negotiable, this higher level of assessment being a primary function of discourse. To the extent that P’s status is actively negotiated by the interlocutors (not just passively accepted), we can speak of interactive grounding, two dimensions of which are polarity and speech act.

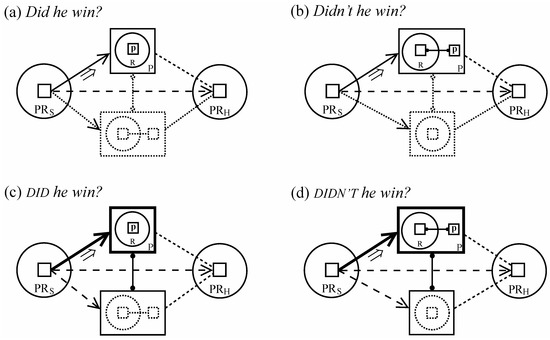

5.2. Polarity

Polarity (positive vs. negative) has so far been treated as part of basic grounding (Figure 8). There is of course an asymmetry, the baseline for clauses being a simple positive statement (e.g., he won). With respect to this, negative clauses (he didn’t win) represent a higher stratum affording a wider array of grounding options. Due to its fundamental nature, polarity is commonly treated as a routine feature of clausal description, hence discursively non-prominent (Boye and Harder 2012). In English this is marked accentually, so a negative form like didn’t remains unstressed: hĕ dĭdn’t wín. However, being both important and subject to disagreement, polarity can also be put in focus as something to be negotiated by the interlocutors. In that case it constitutes interactive grounding. Focused polarity, both positive and negative, is marked in English by a certain amount of accent on the finite verb, as indicated by the small caps in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Polarity organized in strata.

While negotiation (broadly conceived) is always a factor in language use, it is minimal in a simple positive statement (like he won) whose validity is not at issue. In Figure 10a, dotted lines indicate features of the substrate—reality and the negative alternative to p—that are taken for granted and left implicit (cf. Figure 6c). On the other hand, a negative statement necessarily invokes the positive alternative, for without it there is no indication of what is being negated (cf. Figure 6e). Accordingly, the notation in Figure 10b indicates that both alternatives are active, with a solid (rather than a dashed) arrow indicating the option actually chosen. Although a negative statement chooses the option of p being absent from R, its absence is conceived in relation to its presence. This evocation of alternatives (raising the issue of choosing between them) correlates with do—instead of the lexical verb—assuming the role of finite verb: he didn’t win (rather than *he won not).

Figure 10.

Polarity at the basic level.

Diagrams (a′) and (b′) are adopted as notational variants of Figure 10a,b. They further indicate that the status of the clause as a proposition (P) is not exploited at this level (dotted line box). Status as a proposition is however relevant when we turn to focused polarity. Polarity focusing represents a transition between clause structure and the organization of connected discourse. It belongs to the interactive level, being an overt manifestation of the negotiation through which interlocutors seek to align their reality conceptions.

The prominence of polarity focusing depends on awareness of alternatives, engagement with an actual interlocutor, and the degree of force required to overcome the divergence of views. Its force-dynamic nature is reflected iconically by accentual prominence: he’ll win vs. he will win. At the extreme, heavy (“contrastive”) stress marks the strong contradiction of a prior statement, as in (5a). Polarity is focused to a lesser degree for a variety of reasons. This is natural in the context of answering a “yes-no” question, or in simply negating what has just been said, as in (5b,c). It is often just a matter of bringing the proposition to mind, making sure it is known and not overlooked, or overcoming a suspected inclination toward the polar opposite, as in (6).

| 5. | a. | You’re just wrong—he WILL win. | |

| b. | A:Should I reject the offer? | B:Yes, you should reject it. | |

| c. | A:He has finished the report. | B:No, he hasn’t finished it. | |

| 6. | a. | He might win, after all. |

| b. | Bear in mind that he didn’t win the popular vote. | |

| c. | Even so, you can’t deny that he did win. | |

| d. | He may be winning the election, but he is making a fool of himself. |

We need to consider in more specific terms how negotiation enters the picture. Polarity focusing indicates that—in some way, to some degree—the potential for negotiation is realized: the negotiable proposition expressed by P is being negotiated. To the extent that the interlocutors are actively engaged in negotiation, we can speak of interactive grounding. This is a kind of grounding because it pertains to the status vis-à-vis reality of the profiled occurrence (p). But only indirectly. Though related to basic grounding (Figure 8), it constitutes a second level of epistemic assessment serving to elaborate it. Basic grounding conveys the epistemic status of the profiled occurrence (p) as assessed by a single conceptualizer. By contrast, interactive grounding involves the view of another conceptualizer and concerns the validity of the clausal proposition (P). The proposition comprises both p and its basic grounding (which is thus included in the scope of assessment).

These levels of assessment correspond to different levels of reality. Basic grounding locates p with respect to basic reality (R). It includes polarity, which represents the choice between two options, positive vs. negative. On the other hand, interactive grounding locates P with respect to propositional reality (PR). It includes polarity focusing, which indicates that the option chosen is the correct one, i.e., it specifies the validity of the resulting proposition. So in negotiating the status of P, the interlocutors are also negotiating the status of p.

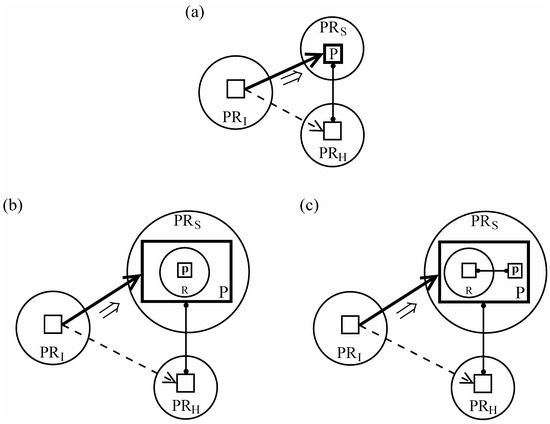

Propositions are subject to negotiation because they are apprehended by different conceptualizers with different versions of PR. With polarity focus, the issue being negotiated is whether to accept as valid the overtly expressed proposition, P, or else the one with opposite polarity. Three versions of PR are thus involved: that of the speaker (PRS), that of the hearer (PRH), and an intersubjective version (PRI) comprising what they presumably share. As shown in Figure 11a, P is accepted by the speaker (hence included in PRS), but may not be by the hearer (and is then excluded from PRH). Their interaction is aimed at determining which of two eventualities—P or its absence—should be adopted in the updated version of PRI. At this higher level of assessment, the negotiation is one-sided: the speaker is always advocating her own position (heavy-line box and arrow). A double arrow represents the force of her advocacy.

Figure 11.

Propositional reality and polarity focusing.

It bears repeating, however, that there are two levels of epistemic assessment with different semantic functions: polarity—positive or negative—is a matter of existence (whether p is realized); its focusing is a matter of affirming, and thereby reinforcing, the chosen polarity option (the one reflected in P). Figure 11a is neutral as to whether the proposition (P) is positive (he did win) or negative (he didn’t win). The difference is made explicit in Figure 11b,c. The proposition (P) is positive when the occurrence (p) is part of basic reality (R). It is negative when the occurrence is excluded from R. Whether positive or negative, P belongs to PRS, the speaker’s conception of propositional reality. In either case, by affirming the polarity option overtly expressed, the speaker indicates that P is to be included in PRI. This is done based on the supposition that the hearer might be inclined toward its exclusion.

5.3. Questions

Along with statements and commands, questions are a basic speech act (Austin 1962; Searle 1969) representing a fundamental kind of human interaction. Questions qualify as interactive grounding because the interlocutors are actively negotiating the epistemic status of propositions. (I will ignore commands, which are also a kind of interactive grounding. They are effective rather than epistemic, pertaining to the realization of occurrences rather than the validity of propositions.) They perform this speech act by enacting the question scenario, which is part of the conceptual substrate, hence included in a question’s meaning even when implicit.

In English, questioning correlates (albeit imperfectly) with the subject following the finite verb rather than preceding it: did he?, was she?, should I? (cf. Figure 4b). The details of this so-called “inversion” do not concern us (see Langacker 2015c). What matters here is that this characteristic feature of questions involves the finite verb, which registers the epistemic status of the profiled occurrence. Since coming first is a kind of focusing, preposing the finite verb highlights the role of epistemic assessment, focusing on the very existence of p. (I will only be considering polarity (“yes-no”) questions. Content questions—with who?, what?, etc.—focus instead on the information needed for P to be valid.)

Polarity questions are closely related to disjunction: coordinate structures marked by (either) or in English. When the conjuncts happen to be clauses, one possibility is for the second clause to be the polar opposite of the first. In that case the negative clause is subject to ellipsis, repeated elements being left unexpressed. The parallelism between (7) and (8) suggests that polarity questions be analyzed as disjunctive questions in which the negative alternative is wholly implicit. The conceptual characterization of disjunction is thus a point of departure for their analysis.

| 7. | a. | Either he won, or the election was rigged. |

| b. | Either he won, or he didn’t (win). | |

| c. | Either he won, or not. |

| 8. | a. | Did he win, or was the election rigged? |

| b. | Did he win, or didn’t he (win)? | |

| c. | Did he win, or not? | |

| d. | Did he win? |

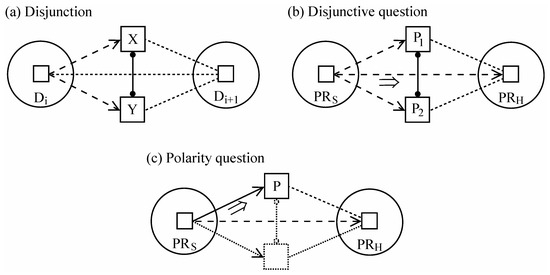

As a general characterization, sketched in Figure 12a, disjunction consists in an unresolved choice among alternatives, labeled X and Y (cf. Figure 6a). X and Y are competing candidates for the privilege of elaborating a conceptual domain (D) at some locus (small box). While the diagram shows just two, there can be any number of candidates, of any sort. Normally X and Y are taken as being inconsistent, hence mutually exclusive. By its very nature, disjunction incorporates a fictive element (Talmy 1996; Langacker 2005): an imagined situation in which the choice has been made. In this updated structure (Di+1), one eventuality (X or Y) serves as the locus. However, since its identity is not actually known, X and Y both correspond to the locus. So given that X and Y are mutually exclusive, a single, consistent conception fails to emerge. Having two incompatible versions, the updated structure is inherently unstable; the imagined situation can only be apprehended by flipping back and forth between the alternatives, as in the perception of an ambiguous figure. This is nonetheless a coherent conception perfectly capable of being invoked as a linguistic meaning. It is unproblematic granted the dynamicity of conceptual structure.

Figure 12.

Polarity questions as a kind of disjunction.

As seen in Figure 12b, disjunctive questions represent a special case of disjunction. First, the alternatives are propositions (P1 and P2); for (8a), these propositions are he won and the election was rigged. So the relevant conceptual domain is propositional reality (PR). A question is a request for information, so two versions of PR come into play: that of the speaker (PRS) and that of the hearer (PRH). At least canonically, the requested information is absent from PRS, whereas PRH is thought to contain it. (A more complete diagram would also show PRI—the intersubjective version—as well as the anticipated updating of PRS and PRI.) A double arrow represents the interactive force of questioning. It is aimed at eliciting an appropriate response: a proposition representing the correct alternative, to be incorporated in an updated version of PRS. Because it concerns the epistemic status of propositions, this negotiation constitutes interactive grounding. If successful, it results in the negotiated proposition being shared by PRS and PRH, hence included in PRI.

Simple polarity questions (e.g., did he win?) are like disjunctive questions except that only one option is made explicit, as indicated by the solid-line box and arrow in Figure 12c. One is enough because the two eventualities are polar opposites: just P vs. its absence, rather than distinct propositions requiring separate specification. The explicit alternative presents the proposition (P) whose validity is being queried, calling on the hearer to either confirm or deny its presence in PRH. Usually P is positive (did he win?), that being the baseline. Negative questions (didn’t he win?) are not uncommon, but they often invoke a more elaborate interactive substrate (beyond the scope of this discussion).

Figure 13a,b show explicitly that there are two levels of assessment. One level pertains to the internal structure of P. P itself is positive or negative depending on whether the profiled occurrence (p) is realized; at issue, then, is whether p is included in R. The higher level of assessment pertains to the status of P. One outcome, for either (a) or (b), is acceptance: P is judged to be valid (part of PRH), and is thus included in the updating of PRS and PRI. Another possibility is rejection: being judged invalid (not part of PRH), P is excluded from the updating of PRS and PRI. More elaborate diagrams would indicate the response and the updating that results.

Figure 13.

Polarity questions and polarity focusing.

Both positive and negative questions are subject to elaboration by means of polarity focusing, as in Figure 13c,d. In both cases this is marked by accentuation of the finite verb in the overtly specified alternative (Did he win? vs. Didn’t he win?). Polarity focusing has the same basic effect in statements and in questions: it reinforces the idea that the chosen alternative is the one whose status is being negotiated. In so doing, it renders the other alternative a bit more salient by underscoring the fact that a choice is involved.

At the same time, its effect is slightly different because statements and questions differ in the arrangement of their key elements: PRS, PRH, P, and its implicit alternative. In a statement, polarity focusing implies the arrangement in Figure 11, where P belongs to PRS, and the opposing alternative to PRH. What this amounts to is that P represents the speaker’s view, in contrast to that of the hearer. In questions, on the other hand, focusing underscores the role of P as the queried proposition, the one whose status the speaker is trying to ascertain. Pending the hearer’s response, it is not ascribed to either PRS or PRH.

6. Conclusions

Based on specific structural considerations, I have outlined an account of clause structure involving conceptual layering. The key notions—grounding and reality—are characterized in terms of strata, in which the elaboration of a baseline gives rise to higher levels of organization. A finite clause profiles an occurrence (p) and specifies its epistemic status by means of grammaticized grounding elements. Included (at successive strata) are basic grounding by “tense”, modals, and negation as well as interactive grounding in the form of polarity focusing and speech act. Basic grounding situates p with respect to basic reality (Figure 8), resulting in a proposition (P), while interactive grounding situates P with respect to propositional reality (Figure 11 and Figure 13). Because p and its grounding are part of P, interlocutors who negotiate the status of P are ultimately concerned with that of p.

Being confined to one-clause expressions in English, the account does not—in its specifics—have any claim to universality. It does, however, reflect schematic characterizations which do have that status, e.g., the abstract notion of clausal grounding. If broadly defined as indicating the epistemic status of occurrences, clausal grounding represents a fundamental semantic function whose structural implementation varies greatly from language to language. The system just described represents a particular strategy of implementation, one involving highly grammaticized grounding elements manifested on the finite verb; from the standpoint of English, this constitutes clausal grounding in the narrow sense. But with a broader definition, numerous other phenomena fall under this rubric. Just a few will be mentioned here by way of conclusion.

The modals discussed above comprise the core of a system that also includes more peripheral members, notably need, dare, and ought. Semantically, these verbs convey a kind of effective modality (note that need is similar to must, and ought is quite comparable to should). Grammatically, they function like the core modals in some respects, e.g., negation: {need / dare / ought} not (cf. {must / would / should} not).

Various kinds of adverbial expressions serve the function of grounding in the broad sense of indicating epistemic status. For instance, the adverbs perhaps and possibly specify potentiality, making them similar to modals, whereas certainly and undoubtedly specify reality, as does the absence of a modal. But unlike basic grounding, these specifications pertain to propositions (rather than occurrences) and their status in regard to propositional reality. Thus a clause like perhaps he lied involves two levels of epistemic assessment: at the lower level, basic grounding (past tense) marks the occurrence he lie is as being real (included in R); while at the higher level, perhaps qualifies that assessment by indicating that the validity of the resulting proposition, he lied, is merely potential (it is not yet included in PR). The speaker thereby indicates, indirectly, that the inclusion of p in R is also just potential.

Speech acts are an aspect of linguistic meaning, inhering in the conceptual substrate even when left implicit. The basic speech acts of statement, ordering, and questioning represent grounding (in the broad sense) in that epistemic status is central to their import. The statement scenario reflects the canonical situation in which the speaker accepts and presents the profiled occurrence (p) as having the reality status indicated by basic grounding (Figure 8): He {lied / didn’t lie / might lie}. The reality status of p is also at issue in the case of ordering, which is aimed at effecting its realization (or non-realization): Lie!; don’t lie!. Resembling a main use of modals in this respect, it is an interactive alternative to basic grounding. Questioning represents interactive grounding at a higher level of organization, where the validity of a proposition is being negotiated. Whether marked by intonation alone (he lied?) or by word order (did he lie?), a polarity question evokes the proposition—comprising p and its basic grounding—expressed by the corresponding statement (he lied). In the former case, the speaker indicates her tentative acceptance of P (its inclusion in her own version of PR) and is seeking confirmation from the hearer. In the latter case, she is considering alternatives (hence the use of do) but frames the query in terms of P (Figure 13). Either way, determining the validity of P is a means of assessing the status of p.

The above grounding options are all observed in expressions comprising just a single clause. More elaborate expressions provide a much wider array of possibilities. Certain constructions with grounding import are intermediate between single- and multi-clause expressions. These consist of a full, finite clause which in isolation would be interpreted as stating a proposition, together with an adjunct (or “satellite”) that in some way pertains to its validity. Thus they offer a complex, multi-level assessment more varied and more nuanced than grounding in the narrow sense. For example, clause-external adverbs qualify the assessment that P is valid, indicating that it is merely a candidate for inclusion in PR: {possibly / conceivably / certainly / undoubtedly}, he is lying. Another option is a tag question, which weakens the assessment by requesting confirmation: He lied, didn’t he?.

Lastly, complementation makes available an open-ended array of propositional assessments. In a large proportion of cases where the complement clause is finite (e.g., she believes he lied), the matrix grounds the complement proposition (P) by indicating its status with respect to PR. Though more substantive and far more varied than grammaticized grounding elements, the matrix predicates in question (commonly referred to as “predicates of propositional attitude”) are directly concerned with epistemic assessment. They focus on different facets of it: validity as such (true, false, evident, inaccurate); inclination toward acceptance in PR (likely, possible, appear, doubtful); stages in the assessment process (suspect, believe, learn, know); negotiation through communicative interaction (claim, argue, inform, deny); speech acts involving propositions (say, tell, ask, promise).

The grounding of the complement by the matrix differs from its basic (clause-internal) grounding in several ways: it pertains to P rather than p; the assessment is put onstage as an overt object of description (the occurrence profiled by the matrix); the responsible conceptualizer, instead of its default identification as the speaker, can be anyone evident from the context (often being specified by the matrix subject); and its more elaborate conceptual content provides an open-ended array of grounding options. Of course, the matrix may itself be a finite clause that profiles an occurrence (p′) whose grounding results in a higher-level proposition (P′). In that case, the full expression describes a complex situation where one propositional assessment figures in another. Hence the matrix has a dual function: it grounds the complement proposition (P) by indicating its status vis-à-vis PR; and it treats that assessment as a grounded occurrence (p′) in its own right, yielding a higher-level proposition (P′) whose validity can in turn be negotiated (e.g., Does she believe that he lied?). Complex situations of this sort comprise much of the mental world we think and talk about.

The grounding function of the matrix underlies the recognition that, instead of being the “main clause,” it is often better characterized as a formulaic stance marker with epistemic import (Thompson 2002; Diessel and Tomasello 2005; Boye and Harder 2007; Langacker 2015b). Even when it clearly is a clause, its relation to the complement proposition (P) resembles the clause-internal relation between a grounding element and the profiled occurrence (p). The roles of P and p are analogous, in that each—at its level of organization—is the focus of attention: p by virtue of being the intended clausal referent, and P because its content is the main point of interest. Usually, one’s primary concern in making the statement she believes he lied is whether he lied (not that she believes it). Even in a much longer expression, e.g., I know Kim believes that it’s possible that he’s lying, the ultimate concern is still whether he is lying.

A chain of complements can be of any length. Typically, at least, the main point of interest is the occurrence profiled at the lowest level of organization, in that it corresponds most closely to the objective reality being negotiated through linguistic interaction. Each successive clause involves two kinds of epistemic assessment: one situating the profiled occurrence (p) with respect to basic reality, and the other assessing the resulting proposition (P) with respect to propositional reality. However many clauses there may be, collectively they effect the grounding of the lowest-level occurrence, in the broad sense of indicating its epistemic status.

That brings us to the main point of interest for this paper: linguistic structure is revealingly characterized in terms of a notion of reality comprising multiple dimensions and levels of organization; and since a complement chain can have any number of clauses, what counts as reality for this purpose can have any number of levels.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Austin, John Langshaw. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boye, Kasper, and Peter Harder. 2007. Complement-taking predicates: Usage and linguistic structure. Studies in Language 31: 569–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, Kasper, and Peter Harder. 2012. A usage-based theory of grammatical status and grammaticalization. Language 88: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessel, Holger, and Michael Tomasello. 2005. A new look at the acquisition of relative clauses. Language 81: 882–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2002. Deixis and subjectivity. In Grounding: The Epistemic Footing of Deixis and Reference. Edited by Frank Brisard. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2005. Dynamicity, fictivity, and scanning: The imaginative basis of logic and linguistic meaning. In Grounding Cognition: The Role of Perception and Action in Memory, Language and Thinking. Edited by Diane Pecher and Rolf A. Zwaan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 164–97. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2008. Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2013. Modals: Striving for control. In English Modality: Core, Periphery and Evidentiality. Edited by Juana I. Marín-Arrese, Marta Carretero, Jorge Arús Hita and Johan van der Auwera. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2015a. On grammatical categories. Journal of Cognitive Linguistics 1: 44–79. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2015b. Descriptive and discursive organization in Cognitive Grammar. In Change of Paradigms—New Paradoxes: Recontextualizing Language and Linguistics. Edited by Jocelyne Daems, Eline Zenner, Kris Heylen, Dirk Speelman and Hubert Cuyckens. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 205–18. [Google Scholar]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2015c. How to build an English clause. Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics 2: 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, Ronald W. 2016. Baseline and elaboration. Cognitive Linguistics 27: 405–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, John R. 1969. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser, Eve E. 1990. From Etymology to Pragmatics: Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy, Leonard. 1988. Force dynamics in language and cognition. Cognitive Science 12: 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmy, Leonard. 1996. Fictive motion in language and “ception”. In Language and Space. Edited by Paul Bloom, Mary A. Peterson, Lynn Nadel and Merrill F. Garrett. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 211–76. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Sandra A. 2002. “Object complements” and conversation: Towards a realistic account. Studies in Language 26: 125–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).