In this section we will first review

Snyder and Hyams’ (

2015) account of the acquisitional delay found in English

be-passives. Then we will show that their account, the UFH, can be extended in a simple way to account for the observed delay in FDs.

3.1. English Be-Passives and the Universal Freezing Hypothesis

Snyder and Hyams (

2015) propose that the lateness of English

be-passives is due to a freezing effect. For the syntax of the passive, they adopt the analysis of

Collins (

2005a), which is based on a strict interpretation of UTAH (i.e., the Uniformity of Theta-Assignment Hypothesis;

Baker 1988, p. 46;

1997, p. 74). Under

Collins’ (

2005a) interpretation, a verb’s external θ-role must be assigned in exactly the same way in active and passive sentences, namely to the specifier of

vP. In a passive the external argument is realized either as a PRO, in the case of a short passive; or as an overt DP (preceded by the overt voice-head

by), in the case of a long passive.

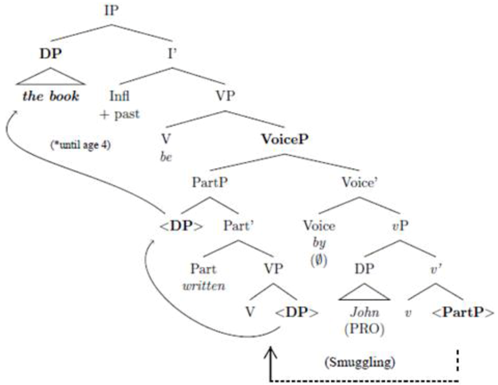

Consider the

be-passive in (15). Given the presence of the external argument

John in Spec-

vP, simple argument-movement of the object DP

the book into Spec-IP would violate relativized minimality (RM;

Rizzi 2001,

2004). The solution proposed by

Collins (

2005a) is that the object is “smuggled” past the external argument, via movement of a larger phrase, after which it raises to subject position without a minimality violation, as shown in (16).

| 15. | The book was written by John. |

| 16. | ![Languages 03 00018 i001]() | Cf. Collins 2005a, pp. 90, 95 |

In (16), the V

write raises to the head of PartP and forms the participle. Smuggling occurs when the entire PartP, including the object, raises past the external argument in Spec-

vP and lands in the specifier of the passive voice phrase. From here the object DP can undergo cyclic movement into the subject position in a fashion compatible with minimality.

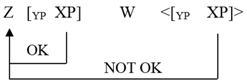

Collins (

2005b, p. 292) defines “smuggling” in terms of the illustration in (17): The constituent XP cannot be directly related to Z, due to an intervening element W. Yet, after movement of the larger constituent YP to a position from which it c-commands W, XP can be related to Z. In this case, YP “smuggles” XP past W.

6

In the cases of smuggling discussed by

Collins (

2005a,

2005b), the relation between XP and Z is always one of movement: the relation created by moving XP to position Z.

The entire concept of smuggling hinges on the idea that the Freezing Principle (which was proposed independently in

Ross (

1967,

1986) and

Wexler and Culicover (

1980)) allows for some exceptions. One formulation of the principle, based on

Müller (

1998), is given in (18).

| 18. | Freezing Principle: In the following configuration, no operation (such as Move) may relate X and Z: * Z … [Y … X …] … <Y> |

According to this principle, the direct object inside the PartP in (16), which corresponds to the X inside Y in (18), should be frozen to further syntactic operations, and therefore unable to undergo raising into subject position. Hence,

Collins (

2005a,

2005b) concludes that there must exist situations in which the Freezing Principle fails to apply, although he does not attempt to spell these out in a general theory.

Finally, the role of smuggling in the late acquisition of the

be-passive, according to

Snyder and Hyams (

2015), is connected to a difference in the capacity of adults and children under four to make the required exception to the Freezing Principle. In children that young, the Freezing Principle blocks smuggling, and thereby blocks the

be-passive: without smuggling, the underlying object cannot get past the intervener that separates it from subject position.

Snyder and Hyams (

2015) formulate this hypothesis as the UFH, as stated in (19).

| 19. | The Universal Freezing Hypothesis: For the immature child (until about age four), the Freezing Principle always applies. No subpart of a moved phrase can ever be extracted. |

The UFH thus accounts for the observed delay in children’s mastery of

be-passives, which depend on smuggling to circumvent a Minimality violation.

3.2. The Universal Freezing Hypothesis and the Locus of Maturational Change

As formulated above, the UFH describes a change in the availability of exceptions to the Freezing Principle, but it does not address why such a change would occur. The answer presumably depends on the precise nature of the maturational change that the UFH describes. For example, one possibility is that there are essentially two Freezing Principles provided by Universal Grammar (UG). Under this view, a “maximally restrictive” version of the Freezing Principle, which is active in the grammar of very young children, is replaced by a “selective” version sometime around the age of four.

Yet, this is not the approach that we advocate. For one thing, there are reasons to doubt that the Freezing Principle itself (whether selective or restrictive) is actually a primitive element of UG. For example,

Uriagereka (

1999) argues that freezing effects can be made to follow as a deductive consequence from mechanisms that are independently needed for cyclic spell-out. Alternatively,

Keine (

2016) argues that they can be derived from limitations on the search space of probes.

Furthermore, in

Borga and Snyder (

forthcoming) we review recent experimental evidence suggesting that an absolutely restrictive version of the Freezing Principle would be too strong, even for children younger than four. As an alternative, we propose that the syntactic structures resulting from a smuggling-based derivation impose excessive demands on the child’s computational resources for language processing. This proposal accommodates recent evidence suggesting that children’s ability to produce and comprehend

be-passives improves in experiments that either (i) eliminate the need for the use of a smuggling derivation in the first place, for example by adding a feature like [+

wh] or [+Topic] to the derived subject (cf.

Rizzi 2004); or (ii) take steps to reduce the processing load that a smuggling-based structure creates, for example by providing a structural prime for the

be-passive (e.g.,

Messenger 2010). In the case of (i), information structure is manipulated via context provided in the experimental task, resulting in a derived subject which is either discourse old ([+Topic]) or which undergoes

wh-movement, avoiding Minimality violations and the need for smuggling in either case (cf. footnote 8). As regards (ii), one analysis of syntactic priming studies is that the comprehension of a sentence can aid in activating its underlying syntactic representation, which can then be re-used in further production and comprehension, at a reduced processing cost (

Guasti 2016, p. 203). The point which follows from both observations is that the change taking place around the age of four is not a change in the grammar itself, but rather in the level of computational complexity (and, hence, grammatical complexity) that the child’s language processing system can handle.

7 3.3. Extending the Universal Freezing Hypothesis to Faire Datives

Despite the existence of parallels between English passives and Romance causatives, it is not immediately clear that

Snyder and Hyams’ (

2015) freezing-based approach to passives can account for the acquisitional timing of causatives. The maturational delay described in the UFH appears to be tied to DP movement, which does not play any role in standard analyses of

faire-causatives (e.g.,

Kayne 1975;

Rouveret and Vergnaud 1980;

Burzio 1986). Yet, there is reason to think a form of smuggling might also be needed in certain causatives.

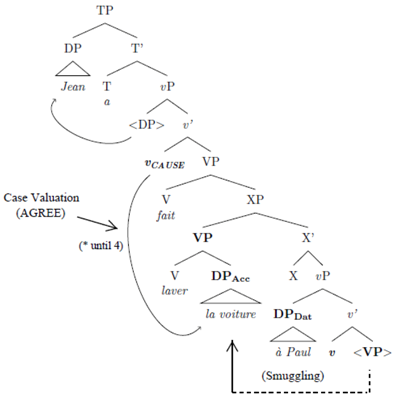

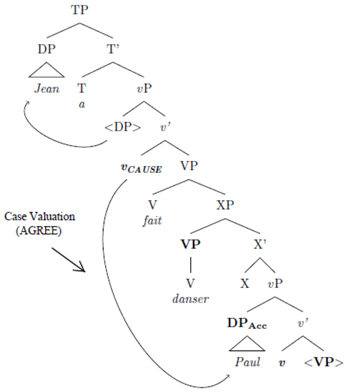

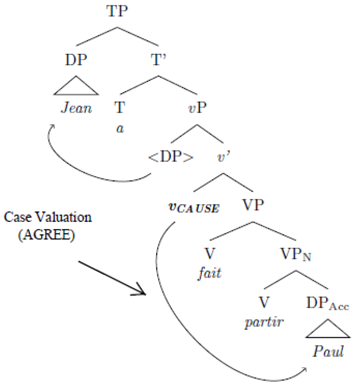

A number of authors, going back to

Kayne (

1975), have proposed that a derivation along the general lines of (20) (which is based on a discussion in (

Belletti and Rizzi 2012)) is found in French and Italian FDs.

In (20) we have labeled as ‘smuggling’ the step of the derivation in which the VP headed by

laver ‘wash’ is moved past the external argument,

à Paul ‘to Paul’. (In the version of this analysis sketched by

Belletti and Rizzi (

2012, p. 135), the VP undergoes feature-driven movement to the specifier of a functional head, X, which the authors, suggest is the head of a “(small) clausal complement” to the causative verb).

As emphasized by

Belletti and Rizzi (

2012), this is an instance of smuggling, even though nothing moves out of the moved constituent. The VP containing the lower verb’s direct object moves past the intervening dative causee, into a position where the direct object can be case-valued by v

cause.

8 To repeat the definition from

Section 3.1, stated in terms of the diagram in (17) (repeated as (21), with the elements from the FD inserted), smuggling is the movement of a constituent YP (here the VP containing the lower object) into a position where XP (the lower object) can be “related to” Z (the higher functional

vCAUSE head).

| 21. | Smuggling in the faire dative: |

| | ![Languages 03 00018 i004]() |

In the cases of smuggling discussed in

Collins (

2005a,

2005b), the relation between XP and Z was always one of movement, but if we take movement to require the establishment of an AGREE relation, then the crucial relation between XP and Z can be seen as one of AGREE. Correspondingly, in (20) the crucial relation is an instance of AGREE that simply values a case feature of XP, with no resulting movement.

Hence, to extend the UFH to FDs we really only need to make one change: freezing effects are not fundamentally about movement, but rather about AGREE. As a first approximation we can state this view in the form of a “Modified Freezing Principle”, as in (22):

| 22. | Modified Freezing Principle: In the following configuration, an AGREE relation (usually) cannot be established between X and Z: * Z … [Y … X …] … <Y> |

The formulation in (22) includes the qualification “(usually)” as an explicit indication that certain exceptions will be possible for adults, but—precisely as before—the UFH will mean that these exceptions are unavailable to children younger than four. Hence, the UFH now works well for FDs: children will have substantial difficulties until the age of about four, because the lower verb’s direct object cannot be case-valued without making an exception to the Modified Freezing Principle.

Indeed, potential support for an interaction between freezing and AGREE can be found in recent work by

Keine (

2016,

2018), who notes a type of freezing effect on long distance agreement in Hindi.

9 Agreement between a matrix verb and the object of a nonfinite embedded clause is usually optional in Hindi, as in (23), but is substantially degraded in instances where the lower clause has undergone extraposition, as in (24):

| 23. | shiksakõ-ne | [ raam-ko | kitaab | parhne] | d-ii | |

| | teachers-ERG | Ram-DAT | book.F | read.INF | let.PFV.F.SG | |

| | ‘The teachers let Ram read a book.’ | | |

| 24. | ?? shiksakõ-ne | ti | d-ii | [ raam-ko | kitaab | parhne ]i |

| | teachers-ERG | | let.PFV.F.SG | Ram-DAT | book.F | read.INF |

| | ‘The teachers let Ram read a book.’ | | |

Thus, it appears that Hindi may provide support for the idea that freezing effects can be found in the domain of AGREE, per se, even when extraction from the moved constituent is not at issue.

In order to interpret the UFH in terms of the computational demands of language processing, as described in

Section 3.2, and in terms of a maturationally-timed change in children’s computational abilities, we will need one more adjustment to our assumptions. In terms of movement operations, a smuggling-based derivation requires the language processing systems to represent a chain whose “tail” is properly contained within the “head” of another chain (for example:

The book was [

written <

the book>] by John <

written the book>.) This configuration is plausibly responsible for a substantial increase in computational complexity. Yet, in order to subsume FDs under this account, we will need to assume that this configuration is a special case of a more general source of computational complexity: structures involving AGREE into a moved constituent. In other words, regardless of whether any phrase moves out of the moved constituent, simple AGREE into a moved constituent is something that is both necessary to represent, and difficult to represent, during the computations that subserve language production and comprehension.

Finally, note that our account crucially relies on the idea (shared with

Snyder and Hyams (

2015)) that

get-passives can, at least in some cases, be derived without recourse to smuggling. We will discuss this point in detail in

Section 5. First, however, we will derive and test a novel prediction of the proposals that we have made in the current section.