Abstract

Background: Child Spanish-speakers appear to use more null subjects than do adults. Null subject use, like the use of tense marking, is sensitive to discourse-pragmatics. Because tense marking has been used to identify child Spanish-speakers with specific language impairment (SLI) with near good sensitivity and specificity (89%), null subject use may as well, following the predictions of the Interface Deficit Hypothesis. We investigate the possibility that null subject occurrence may form part of a useful discriminant function for the identification of monolingual child Spanish-speakers diagnosed with specific language impairment. Methods: We evaluate the rate of null subject expression from spontaneous production data, together with results from independent measures of another discourse-sensitive construction, verb finiteness, in child Spanish. We perform a discriminant function analysis, using null subject expression as a target variable, among others, to classify monolingual child Spanish-speakers (N = 40) as SLI or as typically-developing (TD). Results: The SLI group is shown to have significantly higher scores than the TD group on null subject expression. Multiple discriminant functions, including the null subject variable with tense measures, and in combination with mean length of utterance in words (MLUw), are shown to provide good sensitivity and specificity (<90%) in the classification of children as SLI vs. TD. Conclusion: Our findings support the contention that null subject occurrence is a plausible reflection of the Interface Deficit of SLI for Spanish-speaking children.

1. Introduction

Children acquiring overt subject languages such as English produce fewer overt subjects than adults do, with rates of overt subject use that vary from 30–100%, depending on age and mean length of utterance (MLU, see Hyams 2011 for review). Developmental linguistic studies of this phenomenon in overt subject languages have explored syntactic (e.g., Kramer 1993; Rizzi 2005), phonological (e.g., Gerken 1991, 1994) and language processing (Bloom 1991, 1993; Valian 1990) accounts of null subject utterances in these languages, including child English, French, Dutch and German (Hamann 1996; Hamann and Plunkett 1998). Researchers concerned with specific language impairment (SLI) have explored the possibility that this non-adult-like predisposition of English-speaking children to use overt subjects less than adults might distinguish children with SLI from those without it (Grela 2003a, 2003b; Grela and Leonard 1997).

In null subject languages, such as Spanish, Catalan and Italian, there is also evidence (though a debate persists) that typically-developing children use more null subjects than adults. Those arguing that null subject use in these languages is non-adult-like (Grinstead 1998, 2000, 2004; Grinstead and Spinner 2009) maintain that neither language processing nor developing syntax explain non-adult-like subject use in Spanish, but rather that the cross-linguistic predisposition of children to overuse definites, including phonetically null subject pronouns, is at work. For example, child English speakers say things like Have you seen her, Mommy? when Mommy does not know who her is, or Have you seen the dinosaur, Daddy? when the child is surrounded by 75 plastic dinosaurs and Daddy cannot possibly know which dinosaur is prominent in the child’s discourse representation, and should thus be referred to with definite the. Piaget (1929) famously referred to this phenomenon as characteristic of the “Egocentric” developmental stage. Grinstead (1998, 2004) and Grinstead et al. (2013, 2014) contend that this overuse of definites manifests itself in Spanish and Catalan as the overuse of null subjects, among other things. The idea is that null subjects are used in a language such as Spanish when the speaker assumes that the listener requires no clarification as to what antecedent to this pronoun the speaker believes to be prominent in discourse. Overt subjects may be used in adult Spanish when such clarification is required (e.g., topicalization—foregrounding of old information; focus—making prominent new information, etc.) or for other discourse-pragmatic reasons having nothing to do with grammar, as in variationist studies (see Otheguy and Zentella 2012 for review). From this perspective, children’s use of fewer overt subjects than adults in English would seem to be a different kind of phenomenon than in Spanish. Child English-speakers may lack the adult-like syntactic, phonological or language processing resources required to produce overt subjects. In contrast, child Spanish-speakers would appear to possess these resources, but fail to deploy them as a result of the general, cross-linguistic developmental tendency of children to assume that their interlocutors share their presuppositions about the salience of referents in the Conversational Common Ground, to use Stalnaker’s (1974) term. In the same way that this predisposition plays out as, for example, overuse of definite articles in English (see e.g., Maratsos 1974, 1976), it plays out as the overuse of null subjects in Spanish.

To date, no one has investigated the possibility that child Spanish-speakers with SLI use more null subjects than do typically-developing age-matched children. In what follows, we investigate this question, with a comparative eye towards overt subject child languages and with the overall objective of determining whether null subject occurrence, by itself, or in combination with other variables, can help us identify child Spanish-speakers with SLI, using a discriminant function analysis. Though the very interesting question of which discourse-pragmatics variables (e.g., joint attention, physical presence of antecedents and others) determine the use of overt subjects should also be investigated, we will limit the scope of this study to measuring proportions of use of null subjects, which is the elsewhere condition in most varieties of non-Caribbean Spanish. Doing this narrows our focus to grammatical contexts in which children allow the Spanish null pronominal subject to be used. This coheres with our previous work in that it is fundamentally about anaphora, which typically-developing children across languages struggle with (Interface Delay), and which children with SLI have severe problems with (Interface Deficit). In a more practical vein, it is also true that such easy-to-calculate rates of null subjects could be useful to speech-language pathologists in identifying children with SLI in Spanish. First, we turn to children’s subject use in an overt subject language, English, and to studies of subject use by child English speakers with SLI.

2. Subject Occurrence in an Overt Subject Language

Overt subject use in child English has been extensively studied since the 1960s (e.g., Antinucci and Parisi 1973; Bates 1976; Bloom et al. 1975a, 1975b; Brown and Fraser 1964; Guilfoyle 1984; Hyams 1986; Orfitelli and Hyams 2008; Valian 1991). As an illustration of the phenomenon, Valian (1991) shows that in a cross-sectional sample of US English-speaking children, the least grammatically developed, between MLU 1.5 and 2.0 (n = 6, age range 1;10–2;2), used overt subjects in roughly 70% of non-imperative sentences, while a sample of Italian-speaking children used overt subjects in roughly 30% of such utterances (n = 5, age range 2;0–2;5). Examples of such null subject sentences in child English include the following from Bloom et al. (1975a, 1975b) and Brown (1973).

| 1. | Want more apple. |

| 2. | Tickles me. |

| 3. | No play matches. |

| 4. | Show mommy that. |

Among accounts of the null subject phenomenon for child English that have been proposed is the prosodic account of Gerken (1991, 1994), which claims that sentences consisting of iambic metrical structures (two syllables, the first of which is weak), as in [she KISSED] + [the DOG], are most likely to have the weak syllables (critically, the she subject) deleted. While this account seems promising for child English, it seems less so for child Spanish and Catalan, in which subject pronouns are stressed (e.g., Ella besó al perro ‘She kissed the dog’) and would not be predicted to delete for prosodic reasons.

Language processing accounts of child English null subjects claim that overt subjects are dropped because language processing resources are less available at the beginning of sentences (Bloom 1991) and that the phonetically heavier the subject, the more likely it is to be deleted. Problems for this account of child English include the fact that children seem much better able to produce full lexical noun phrase (NP) subjects than they are pronominal subjects in elicited imitations studies (Gerken 1991; Valian et al. 1996). To our knowledge, such an explanation has not been pursued for child null subject languages.

A wide range of developmental syntactic accounts of this non-adult-like behavior have been proposed, many of which have in common an assumption of underdeveloped syntactic structure housing subjects in child grammars (Guilfoyle 1984; Guilfoyle and Noonan 1992; Hyams 1986; O’Grady et al. 1989; Radford 1990; Rizzi 1993). Radford (1990), for example, proposes that functional structure associated with inflection, assumed to house subjects on influential accounts (e.g., Baker 1985, 1996; Pollock 1989), is initially missing, accounting for documented contingencies between verbal nonfiniteness and null subjects (see Hyams and Wexler 1993; Sano and Hyams 1994). On this account, the null subject used in child English is PRO (Chomsky 1981), the null subject used in the subject position of nonfinite verbs, as in (5) and (6).

| 5. | [PRO to leave now] would be ill-advised. |

| 6. | Juan quiere [PRO salir del auto ya]. |

Similar proposals have been made for the gramatical nature of the null subjects used in other child overt subject languages, including Dutch (Kramer 1993); as well as for child Spanish and Catalan (Grinstead 1998), when they occur with nonfinite verbs, which are a fixture in child language cross-linguistically. On such proposals, nonfinite PRO is discourse-identified by the same principles that govern the discourse identification of the adult-like pro of null subject languages. Thus, whether they occur with nonfinite verbs and are PRO, or with finite verbs and are pro, null subjects in child Spanish would seem to require that interlocutors be able to recover the identity of the antecedent, which children appear to generally overassume. While there is a diverse array of child null subject accounts, to date, no comprehensive study has been done to determine empirically the degree to which each variable contributes to an explanatory account of the phenomenon. In what follows, we will assume that child Spanish-speakers are using some combination of pro and PRO null subjects, as a function of the finiteness of their verbs.

3. Subject Occurrence in English-Speaking Children with Specific Language Impairment

While there does not appear to be a consensus account of this phenomenon in child overt subject languages, it seems to be uncontroversial that child English speakers are doing something with subjects that is not adult-like. In the domain of language disorders, Loeb and Leonard (1988) observe that child English speakers with SLI appear to use more null subjects than do typically-developing children. Exploring this observation further, Grela and Leonard (1997) report that in spontaneous production, child English speakers with SLI use more null subjects than do MLU controls. In a sentence completion task, Grela (2003a) shows that a sample of SLI children produces more null subjects than do age controls, but not more than do MLU controls. We see then in child English that null subject production may serve to differentiate children with SLI from typically developing age and MLU controls, depending on methodology. If, as some authors have argued, child Spanish speakers produce more null subjects than do adults, could we find that null subject production is a similarly useful grammatical characteristic of children with SLI, such that it could distinguish them from typically developing children? Before answering this question, we turn to the question of subject use in typically-developing child Spanish.

4. Subject Occurrence in Child Spanish and Catalan

There is evidence that typically-developing child Spanish-speakers also use more null subjects than do adults, though many generative child language researchers (e.g., Hyams 2011; Camacho 2013) appear committed to the position that null subject child languages are adult-like, in spite of this evidence. Grinstead (2000) shows that four longitudinally-studied child speakers of Catalan from the Serra and Solé (1986) Corpus, at the beginning of two-word speech, pass through an early period during which they use no overt subjects at all with verbs in non-imperative sentences. Grinstead (2004) shows that the same phenomenon holds of three longitudinally-studied Spanish-speaking children.

Attempts to dismiss the empirical claim that children learning null subject languages pass through a No Overt Subject Stage have presented putative counterevidence in the form of rates of overt subject occurrence averaged over developmentally large spans of time or have depended on children who have higher MLUs and higher levels of grammatical sophistication even in their first recording sessions than the children reported in Grinstead and Spinner (2009). For example, Bel (2003) presents data from six children aggregated over 8–12 months and also gives month-by-month breakdowns for two of them (Júlia and María). In the aggregate reports (Table 3, p. 7) she shows, for example, that a Catalan-speaking child, Pep, between 1;06 and 2;06 (12 months of language development) uses overt subjects 32% of the time; arguably adult-like proportions. Presenting data in this way, however, disguises the fact that before Pep begins using overt subjects at adult-like rates, or in fact any overt subjects at all, he produces 48 non-imperative verbal utterances without overt subjects (Grinstead 2000, Table 1, p. 125). The other six children reported in Grinstead (2000, 2004) have similar early No Overt Subject Stages.

The month-by-month data presented by Bel (2003), and Aguado-Orea and Pine (2002) to argue against the no-overt subject claim critically depends on the data of children such as María of the López-Ornat corpus. María’s MLU in words (MLUw) in her earliest file is already 1.93, substantially greater than the MLUw of the Catalan-speaking children (mean MLUw = 1.55) and the MLUw of the Spanish-speaking children (mean MLUw = 1.55) in Grinstead and Spinner (2009). More importantly, as pointed out in Grinstead and Spinner (2009), María appears to be using more grammatically sophisticated constructions than the children studied in Grinstead (2004) in that she uses verbs with past imperfect verb tense (e.g., Tenía pupa ‘I had an owie’, María, 1;7), wh- questions (e.g., ¿Dónde está el miau? ‘Where’s the kitty?’, María 1;7) and fronted objects (e.g., Este a pi ‘This, let’s paint’, María 1;7), none of which are present in the spontaneous speech of the seven children studied by Grinstead and colleagues.1

Other studies regularly cited as counterevidence to the No Overt Subject Stage claim, for example in Hyams (2011) and Camacho (2013), suffer from these same two shortcomings. Obviously, if one’s goal is to determine whether or not there is a no-overt subject stage in a child’s longitudinal data, one has to begin looking at data collected at the end of the 1-word stage. Serratrice (2005), for example, cited in both Hyams (2011) and Camacho (2013), is a study of the discourse-pragmatic influences on overt subject expression. Its child data begins when children are already at MLUw 1.5—the exact point at which the children studied in Grinstead (2004) begin to use overt subjects—making it irrelevant to the no overt subject claim, though it is a very interesting study of developmental discourse-pragmatics. Similarly uninformative for the question of whether there is a No Overt Subject Stage, but interesting in their own right, are the data in Lorusso et al. (2004), which was about unergative vs. unaccusative intransitive subjects, and Valian (1991), which is about the plausibility of any syntactic account of null subjects in child English, both cited in Hyams’ (2011) work.

In sum, studies that purport to contradict the claim of a No Overt Subject Stage either present or depend upon data that has been aggregated in a way that obscures the no overt subject observation or ignores the possibility that a child’s first recording session—even though the child may appear to be of a very young chronological age—may have occurred after overt subjects have begun being used. The stage is evident if researchers pay attention to aspects of children’s grammatical development, reflected in MLU values, which are the relevant measures of grammatical, and not chronological, development. See Liceras et al. (2006) and Grinstead and Spinner (2009) for a fuller discussion.2

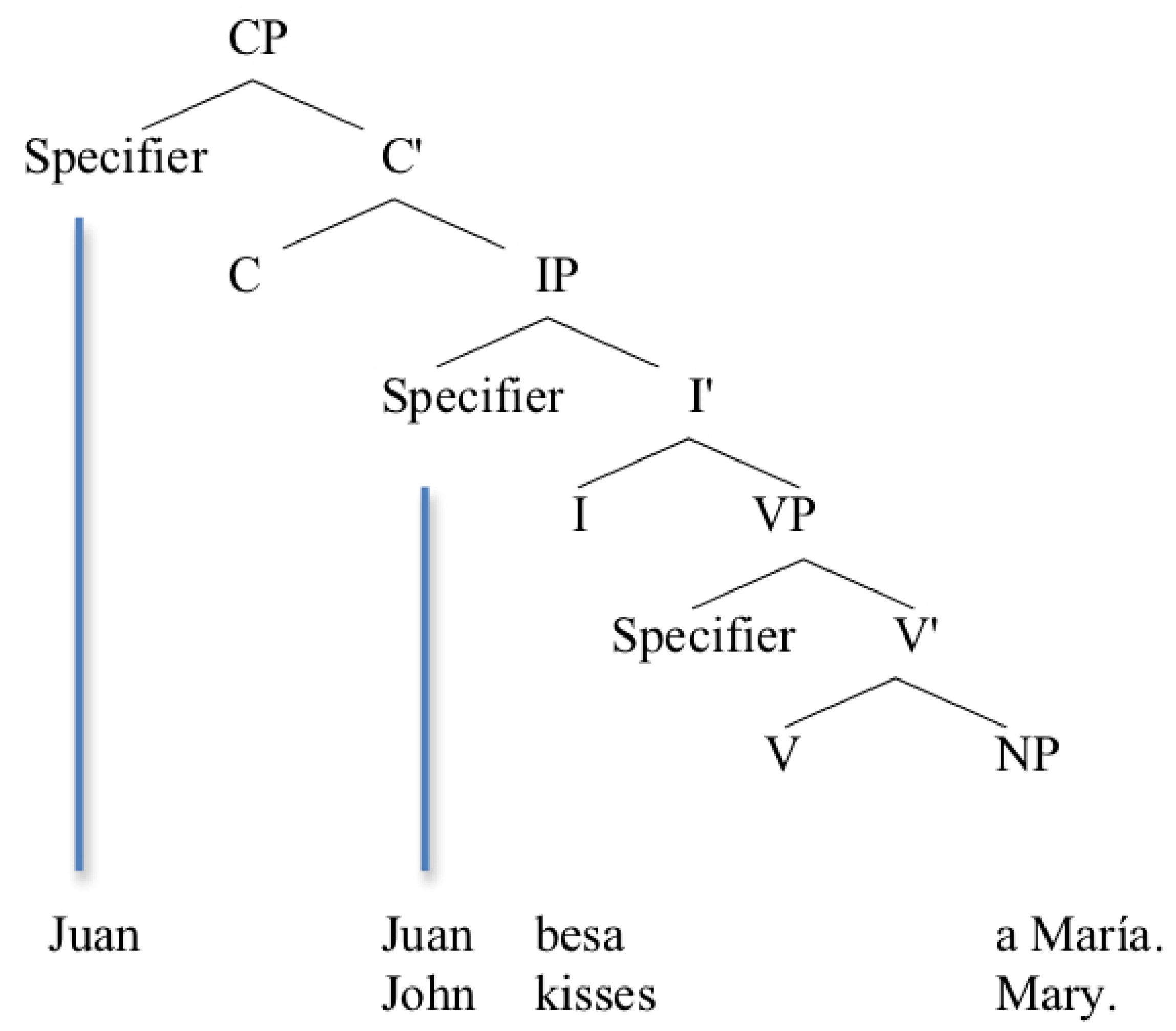

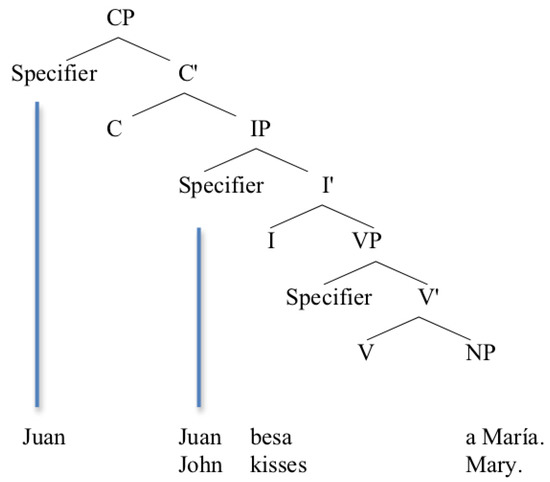

Besides the obvious null vs. overt subject distinction between Spanish and English, there also appears to be a difference in the syntactic nature of their overt subjects. The account of the No Overt Subject Stage presented in Grinstead (2004) and Grinstead and Spinner (2009) claims, following Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou (1998) and Ordóñez and Treviño (1999), that overt subjects in Spanish may be housed in the part of the clause that is closely associated with verb finiteness, as in English, but that they primarily occur with other syntactically optional constituents, higher up in the structure, in the “left periphery” in Rizzi’s (1997) terms. This region of the clause is argued to house other discourse-sensitive constituents including wh- elements in wh- questions and fronted objects in focus and topicalization structures. To illustrate the relevant differences, in Figure 1 the English subject John occurs only in the specifier of the Inflection Phrase (IP), while the Spanish subject Juan occurs in the either the specifier of IP or in specifier of the Complementizer Phrase (CP) (e.g., Ordóñez 1997; Zubizarreta 1998). This syntactic distinction between the two language types is relevant to our claim that overt subjects in Spanish are initially missing for the same reason that children fail to use other syntactically optional, left-peripheral constituents early on.

Figure 1.

Left-Peripheral subjects in Spanish; IP-internal subjects in English.

To show that subjects, wh- questions and fronted objects3 begin to be used at the same time, Grinstead and Spinner (2009), following Snyder and Stromswold (1997) and Snyder (2001), used the binomial test to demonstrate that there was no significant difference between the moment at which subjects began to be used and the moment when the other constructions began to be used. Table 1 reports the ages of onset of overt subjects, wh- question and fronted objects in the longitudinal study of four Catalan-speaking children and three Spanish-speaking children (compiled from (Grinstead and Spinner 2009, Tables 3 and 4, pp. 66–67)). The third column gives the ages of the children in the recording session in which the first overt subject was used. The fourth and fifth columns give the children’s ages when wh- questions and fronted objects were first used. Critically, the fourth and fifth columns also either gives a p value, if there was a significant difference between the onset of overt subjects and the onset of the non-subject construction, or it gives nothing, if there was no significant difference between the onset of overt subjects and the non-subject construction.

Table 1.

Ages of onset and binomial test result of overt subjects, wh- questions and fronted objects in 4 Catalan-speakers and 3 Spanish-speakers, compiled from Grinstead and Spinner (2009, Tables 3 and 4, pp. 66–67).

The evidence in Table 1 shows that each of the seven children had either a correlated emergence of overt subjects and fronted objects or between overt subjects and wh- questions and that 4 of the 7 children had both. Confirmation from another research group is presented in Villa-García and Snyder (2009), summarized in Table 2 (compiled from Villa-García and Snyder 2009, Tables 2 and 3, pp. 6–8). Table 2 presents evidence from four more Spanish-speaking children that there is a contingency between the onset of overt subjects and other left-peripheral constituents. In this case, the evidence is strongest for fronted objects, for which the binomial test shows no difference between their onset and the onset of overt subjects. For wh-questions, this same contingency held only for one of the four children. Summarizing over all 11 children from both research groups, six out of 11 showed a significant contingency between the onset of overt subjects and wh-questions and 10 out of 11 showed a contingency between the onset of overt subjects and the onset of fronted objects. We take this to be strong confirmation of the hypothesis that left peripheral constructions in Spanish, including overt subjects, begin to be used at the same time. It is worth noting that, as pointed out above, the earliest transcripts of María, presented in Bel (2003) and Aguado-Orea and Pine (2002), include all three of these constructions, as Grinstead and Spinner’s (2009) claim would predict.

Table 2.

Ages of onset and binomial test result of overt subjects, wh- questions and fronted objects in 4 Spanish-speakers, compiled From Villa-García and Snyder (2009, Tables 2 and 3, pp. 6–8).

In contrast to Spanish and Catalan, Grinstead and Spinner (2009) show that in child German, an overt subject language in which subject position, but not subject overtness, is discourse-sensitive, children begin using overt subjects significantly earlier, again by the binomial test, than they do wh- questions or fronted objects, as illustrated in Table 3. This comparison makes it clearer that the contingencies found between the occurrence of overt subjects and other left peripheral syntactic constituents in child Spanish and Catalan reflect stark differences in the syntactic nature of the subjects in the two language types and are not simply a function of all syntactic constructions emerging at the same time in all child languages.

Table 3.

Ages of onset and binomial test result of overt Subjects, wh- questions and fronted objects in 2 German-speakers, compiled from Grinstead and Spinner (2009, Table 6, p. 73).

In sum, child English-speakers use more null subjects than do adult English speakers and child Spanish speakers also use more null subjects than do adult Spanish-speakers. Studies that are offered as evidence that child Spanish-speakers use overt subjects in proportions similar to adult proportions either aggregate data in a way that obscures the No-Overt Subject Stage or ignore the possibility that chronologically early recording sessions may not be grammatically early with respect to overt subject occurrence. Presumably earlier data collection would have shown subject occurrence patterns in these studies similar to the patterns attested in the children referred to here. More importantly, null subject use in Spanish is discourse-sensitive and 11 longitudinally studied child Spanish-speakers and child Catalan-speakers, in contrast to child German speakers, begin to use overt subjects at the statistically equivalent developmental moment at which other discourse-sensitive, left-edge constructions (wh-questions and fronted objects) begin to be used. A theory of why null subjects are overused, Interface Delay (Grinstead 1998, 2004), and of why this overuse is particularly severe in children with SLI, Interface Deficit (Grinstead et al. 2009, 2013), may shed some light on the patterns observed so far, and make predictions for what we expect to find with respect to null subject use in child Spanish-speakers with SLI. Before moving on the Interface Deficit, let us review what is known about SLI in Spanish.

5. Interface Delay and Interface Deficit

Jackendoff (1987, 1997) proposes a model of cognitive architecture he refers to as Representational Modularity. On this view, mental faculties have representations that are specific to their domains and the computations that are performed upon them are similarly faculty-specific. In particular, he takes evidence from primate auditory and visual perception (Bradley et al. 1996; Rauschecker et al. 1995; Weinberger 1995) to argue that informational encapsulation (originally suggested by Fodor (1983)) is a natural product of the fact that the mental representations of particular types of sense data are specific to the kind of data that they represent. Following this view, Grinstead (1998) proposes that the domain of discourse-pragmatics and the domain of syntax are fundamentally constituted of different kinds of representations and that the delay in children’s use of discourse-sensitive constructions follows from the faculty-specific nature of each domain’s representations. Interface Delay occurs because the intermediate links that must exist between faculty-specific representations appear to take longer to develop than faculty-internal representations do. A specific consequence of this phenomenon is that any cognitive process that requires an interface among multiple domains will develop more slowly than processes that do not require this type of interaction.4

In the domain of language disorders, Grinstead et al. (2013) claim that this failure to communicate between syntax and discourse-pragmatics is responsible not only for the prolonged delay in tense marking in children with SLI, reported by Rice and Wexler (1996) among others, but also for the more general pattern of all discourse-sensitive constructions being slow to develop in the language of children with SLI, while discourse-insensitive constructions are acquired with relatively little difficulty. Specifically, they review evidence that discourse-sensitive constructions including definite articles (e.g., Anderson and Souto 2005), direct object clitics (e.g., De la Mora et al. 2003) and verb tense (Grinstead et al. 2013) are problematic for child Spanish-speakers, diagnosed with SLI, while discourse-insensitive constructions, such as nominal plural marking and noun-adjective agreement (Grinstead et al. 2008), are not problematic. This special difficulty in the development of discourse-sensitive constructions for children with SLI is referred to as Interface Deficit.

What all of the discourse-sensitive constructions referred to here have in common is a reliance on speakers accessing a representation of the Conversational Common Ground (Stalnaker 1974). Noun phrases are referred to with a definite article if the speaker presupposes that interlocutors are familiar with the referent, i.e., that the referent is salient in the Conversational Common Ground. Direct object (clitic) pronouns, similarly, can only be produced under the presupposition that interlocutors are familiar with the antecedent. Verb tense, in an analogous way, expresses a kind of anaphora from the perspective of the speaker between the speech time-event time relationship prominent in the discourse representation shared with interlocutors. To illustrate the discourse-dependent property of tense interpretation, and its similarity to nominal anaphora, consider the following examples. In these felicitous adult English root infinitives, the grammatical aspect of the verbs in (13b), (14b) and (15b) is morphologically expressed, but the absolute temporal interpretation of the expressions in b. are only interpretable by virtue of temporal anaphora with the expressions in (13a), (14a) and (15a).

| 13. | a. | What is/was Wallace doing, Gromit? |

| b. | Eating cheese. |

| 14. | a. | What does/will Wallace want to do, Gromit? |

| b. | Eat cheese. |

| 15. | a. | What has/had Wallace done, Gromit? |

| b. | Eaten cheese. |

Discourse-sensitive constructions, such as tense marking, contrast with discourse-insensitive constructions, including nominal plural marking and noun-adjective agreement. In order for nouns to be marked plural, no access to Conversational Common Ground is required. Similarly, in order for nouns and adjectives in Spanish and other languages to agree in their markings for number and gender, grammar appears to use strictly “local” morphosyntactic relationships that do not depend on the larger discourse. Oetting (1993) and Oetting and Rice (1993) show that child English speakers with SLI do not have problems with plural marking on nouns and Grinstead et al. (2008) show that child Spanish-speakers with SLI do not have problems with either plural marking on nouns or noun-adjective agreement.

If the Interface Deficit account of SLI is correct, discourse-sensitive constructions including tense marking and null subject use should be particularly problematic for children with SLI, and might be helpful in identifying them.

6. Discriminant Function Analysis

The objective of analyzing the language systems of children with language disorders with a discriminant function analysis is to determine whether particular linguistic properties or collections of properties can be useful for identifying children with the disorders. Bedore and Leonard (1998) show that discriminant functions derived from a verbal morpheme composite, a nominal morpheme composite and MLU in morphemes (MLUm), generated from spontaneous production data, can identify 4 year-old English-speaking children with SLI with fair (<80% accuracy) to good (<90% accuracy) levels of sensitivity (identification of the SLI children) and specificity (identification of the typically-developing age control children). In particular, their Verb Morpheme + MLUm function yielded good and relatively balanced sensitivity (94.7%) and specificity (94.7%). In contrast, Moyle et al. (2011) showed that the same measures, when applied to a sample of older children (mean age = 7;9), produced less effective classification in the fair accuracy range, e.g., their Verb Morpheme + MLUm function produced 74% sensitivity and 84% specificity (79% overall). This is consistent with findings suggesting that tense marking in child English SLI reaches near-typically-developing levels at 8;0 (Rice et al. 1998, 1999).

Discriminant function analysis is particularly important for research on SLI, which is unfortunately a condition diagnosed using primarily exclusionary, as opposed to inclusionary, criteria (Tager-Flusberg and Cooper 1999). Following our Interface Deficit theory of SLI, using the discourse-sensitive construction of tense marking in child Spanish, Grinstead et al. (2013) demonstrate 89% sensitivity and 89% specificity in the identification of children with SLI, approaching the “good” level of precision specified by Plante and Vance (1994), using an elicited production measure of tense in a sample of monolingual Spanish-speaking children in Mexico City. Given that this discourse-sensitive grammatical construction was useful for the identification of Spanish-speaking children with SLI, we ask whether another discourse-sensitive construction, overt subject use, might also prove useful as a clinical marker of SLI in Spanish. Further, we ask whether the addition of a “mixed” discourse-sensitive/discourse-insensitive measure, such as MLUw, might improve accuracy, as it appeared to in both Bedore and Leonard (1998) and Moyle et al. (2011).5

7. Research Questions

- Do monolingual child Spanish-speakers diagnosed with SLI use more null subjects than do typically-developing age controls, as Interface Deficit predicts?

- If so, can null subject rates play a role in the formation of a discriminant function for the selective identification of children with SLI?

- Will the addition of MLUw to more strictly discourse-sensitive measures improve discriminant accuracy, as in previous research?

8. Methods

8.1. Participants

Forty monolingual Spanish-speaking children participated in this study. Each child produced a spontaneous speech sample, interacting with adult native speakers of the Spanish of Mexico City, trained as speech-language pathologists, neuropsychologists or as pediatric neuropsychologists. The children in the study came from a daycare center/preschool and a speech and hearing clinic that service a broad socioeconomic spectrum of children in Mexico City. Twenty of the children were diagnosed with SLI (age range = 58–76 months, mean age = 66 months, SD = 5.8 months), using conventional criteria (following Leonard 2014) and 20 of them were typically-developing (age range = 58–79 months, mean age = 67 months, SD = 5.3 months). The ages of the two groups were not significantly different (t(38) = 0.695, p = 0.491).

Following Leonard (2014), our inclusive criterion for the SLI group was a score on a standardized language test of 1.25 SD below the mean. To that end, children took four subtests of the Batería de Evaluación de Lengua Española or BELE (Rangel et al. 1988), which was normed in Mexico City. Children were given the BELE receptive grammar and vocabulary tests (“Comprensión Gramatical” and “Adivinanzas”) as well as its expressive grammar and vocabulary tests (“Producción Dirigida” and “Definiciones”). Though there are no published validity studies of the BELE, earlier work (Grinstead et al. 2013) reports significant correlations between children’s (n = 29) BELE scores and spontaneous speech measures, including the Subordination Index (r = 0.570, p = 0.001), MLUm (r = 0.717, p < 0.001) and Number of Different Words (r = 0.702, p < 0.001). Children had to score 1.25 standard deviations below the mean on at least one receptive and one expressive subtest to be included in our SLI sample. All TD children were within 1 standard deviation of the mean for their ages. Mean BELE scores for children in each group with p values resulting from independent samples t-tests are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean BELE scores, with standard deviations, comparison results and partial Eta squared values.

For exclusive criteria, children were given a Spanish translation of the WPPSI (Weschler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence) to measure non-verbal intelligence and had to receive a score of 85 or above to be included in the study. Children were also given a phonological screen in which they were asked to repeat 24 two-syllable nonce words that included the segments used in Spanish to represent tense in word-final position, with appropriate stress. In order to be included in the study, children had to produce at least four out of five correctly from each category. Children were given thorough hearing tests and had to pass them at conventional levels. In addition, parental report and medical history had to suggest no recent episodes of otitis media with effusion in order for a child to be included. Similarly, neurological tests determined that the children had no frank neurological damage. With respect to oral structure and oral motor function, initial examination ruled out structural anomalies and assured normal function. Parental report and family history interviews ruled out concerns pertaining to social and physical interactions.

8.2. Procedures

A parent of each child signed U.S. and Mexican institutional review board-approved informed consent documents in order to participate. Children were video-recorded interacting with researchers for 20–30 min, until roughly 100 utterances had been produced. The interaction was unstructured and consisted of conversations about friends in preschool, siblings, favorite movies, etc. and answers were largely narrative in character.

8.3. Subject Occurrence Coding

As alluded to above, our dependent variable is the proportion of non-imperative verbal utterances that occurred with a null subject. Our assumption is that where a child does not use an overt subject, they have chosen to instead use a null subject pronoun, which is a definite. As we have claimed above, this is of theoretical interest inasmuch as children with SLI have been shown to struggle with definites, including definite articles (Restrepo and Gutiérrez-Clellen 2001; Anderson and Souto 2005), direct object clitics (Merino 1983; De la Mora 2004) and verb tense (Grinstead et al. 2013). While the ways in which discourse-pragmatic considerations predict the expression of an overt subject in particular dialects is very interesting,6 they were not the focus of our inquiry. Our goal was instead to determine whether a more rapidly calculable rate of overt subject occurrence might be clinically useful, in contrast with the complexity of identifying discourse-pragmatic determinants of subject occurrence, which is substantially more laborious and consequently less likely to be of clinical utility.7 A noun phrase was counted as an overt subject of a verbal predicate if it occurred in a discourse context that was semantically compatible with its association with that predicate. Subject–verb agreement was taken to be a sufficient, but not a necessary, condition for this association, given children’s potential to produce utterances that do not follow subject–verb agreement, such as the following from Grinstead (1998).

| 16. | Eduardo—3;0.28 | ||

| Yo | quiere | hacerlo | |

| I | want (root + e theme vowel) | do-INF CL-ACC-SG-MASC | |

| ‘I wants to do it.’ | |||

| 17. | Carlos—3;3.28 | ||||

| Yo | va | a | buscar | ||

| I-NOM | go | STEM | to look for-INF | ||

| ‘I goes to look for.’ | |||||

| 18. | Graciela—2;6.5 | ||

| Hace | esto | yo | |

| do (root + e theme vowel) | this | I-NOM | |

| ‘I does this.’ |

Utterances including verbal predicates that appeared nonfinite, such as 16–18, were included in our counts.

8.4. Reliability

Spontaneous speech samples were transcribed by native speakers of the Spanish of Mexico City, the same dialect spoken by the children in the sample. Transcribers were initially normed on a series of common transcriptions. Then, each recording session was transcribed by a single transcriber and checked by a second transcriber. Finally, half of all transcripts were randomly selected to have 10% of their utterances re-transcribed by a second transcriber to ensure accuracy. Agreement between transcribers as to each word transcribed ranged from 90–99%, with a mean agreement percentage of 95.4%. A Krippendorf’s Alpha Interrater Reliability Coefficient (Hayes and Krippendorf 2007) was then calculated for the interval data represented by each transcriber’s number of words per utterance, for each transcript. Alpha values ranged between 0.904 and 0.998, with a mean Krippendorf’s alpha value of 0.974.

Each non-imperative verb was also coded for person, number, and tense, as well as for whether or not it was accompanied by an overt subject. Imperative verbs were not examined because of their cross-linguistic tendency to lack overt subjects (see Rivero and Terzi 1995). Fleiss’ (1971) Kappa was used to determine the inter-rater reliability among the three Spanish-speaking coders. The calculated Kappa of 0.68 was in the category of substantial agreement per the standard set forth by Landis and Koch (1977). Transcripts were further analyzed for MLUw, using the CLAN programs from the CHILDES Project (MacWhinney 2000).

8.5. Previous Experimental Measures

To construct our discriminant functions, we included two independent tests of tense marking, a discourse-sensitive construction, reported in earlier work. Each child had a score from the Grammaticality Choice Task of tense (n = 35), reported in Grinstead et al. (2009), and a score from an elicited production task measuring tense (n = 29), reported in Grinstead et al. (2009). The Grammaticality Choice Task presents children with two sentences, each uttered by a different puppet. One sentence is the adult-like version (e.g., Yo abro la boca ‘I open my mouth’), while the other is the putative child-particular version (e.g., Yo abre la boca ‘I opens my mouth’). The elicited production task has children correct a sentence such as El gato está rompiendo los platos (‘The cat is breaking the dishes’) with a sentence that matches the image presented, such as El gato está lavando los platos (‘The cat is washing the dishes’).

9. Results

9.1. Comparisons

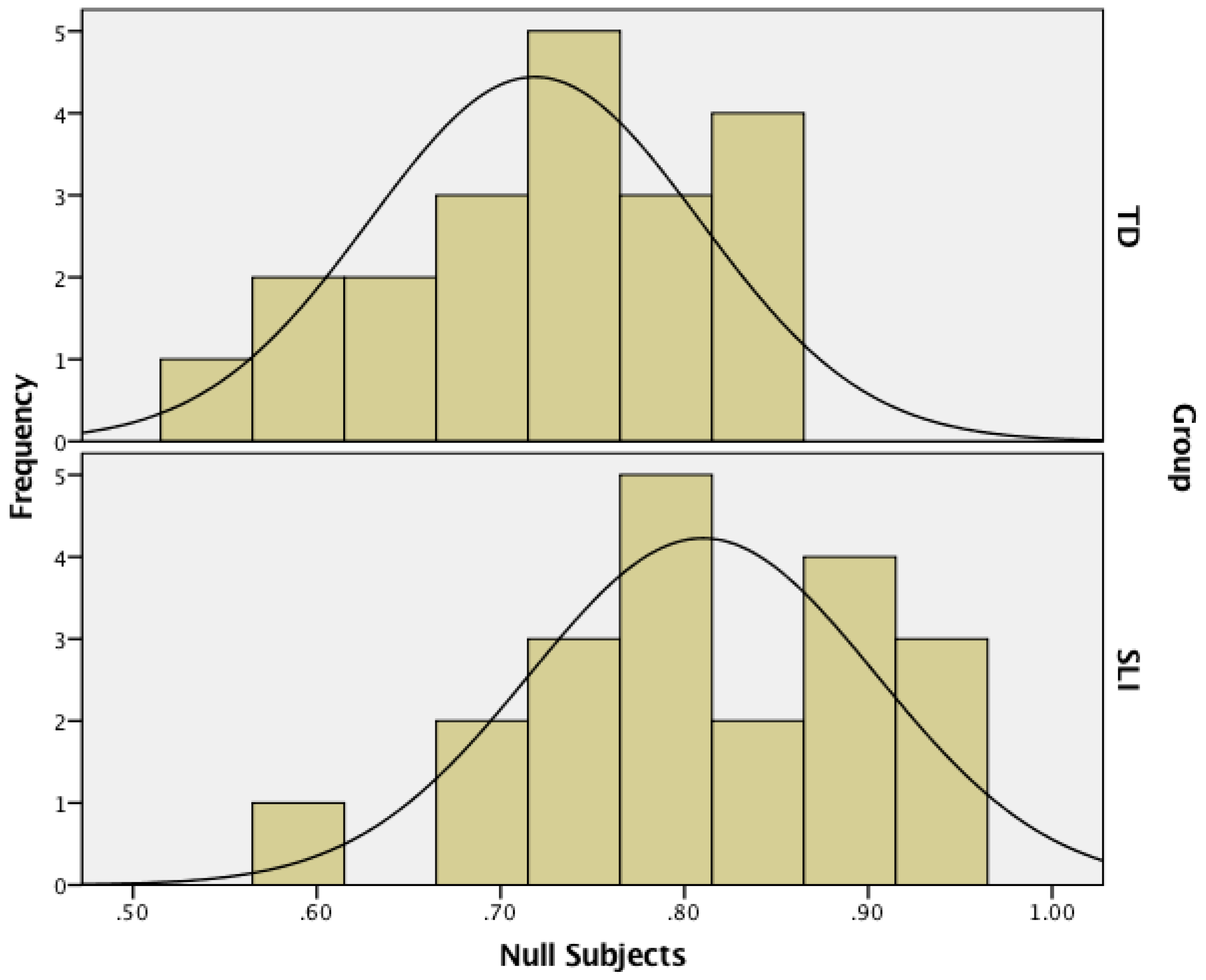

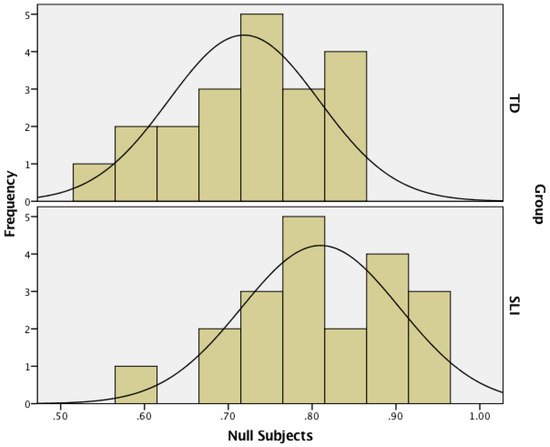

An independent samples t-test was performed to compare the rates of null subject use of the SLI and typically-developing age control groups, which are given in Table 5.8 The SLI rate was significantly higher than was the TD rate (t(38) = 3.141, p = 0.003). Notice in the accompanying histogram that the distributions are normal for both groups and shifted towards one (100% null subjects) in the SLI group. Measures of tense by Elicited Production and Grammaticality Choice are also given in Table 5, together with MLUw values. We report p values in the last column, which corresponds to a t-test for MLUw and subject use, which was normally distributed, but to Mann-Whitney tests for the tense measures, which were not and for which the Z scores are reported. Note that the Quadratic Discriminant Function analysis reported below is robust to non-normality as long as it results from skewness and not outliers, which is the case in our data.

Table 5.

Mean rates of null subject use, mean length of utterance in words (MLUw), grammaticality choice measures of tense and elicited oroduction measures of tense across SLI and TD age control groups.

9.2. Discriminant Functions

A discriminant function analysis was performed to classify participants into groups on the basis of the variables tested by producing a discriminant criterion that maximizes the differences between the groups. Figure 2 illustrates the normal distribution of null subjects in the two populations, which is shifted rightwards in the SLI population, towards 100%. In addition to our subject expression measure, we also have MLUw measures for the same children and verb finiteness measures (grammaticality choice and elicited production) for a subset of these children (grammaticality choice n = 35; elicited production n = 29, all four measures n = 26). Linear discriminant function analysis assumes equal within group variance-covariance matrices, which our data do not have. For this reason, we instead used a quadratic discriminant function analysis, which does not depend upon this assumption (Klecka 1980). Further, discriminant function analysis assumes normally distributed data. Two of our variables are normally distributed (subjects and MLUw) and two are not, resulting from skewness. Because quadratic discriminant function analysis is robust to non-normality caused by skewness and not the presence of outliers (which are absent from our data), we proceeded with the analysis. Various combinations of these four measures (null subject use, MLUw, elicited production tense and grammaticality choice tense) produced the five quadratic discriminant functions given in Table 6.

Figure 2.

Histogram of rates of null subject use in the specific language impairment (SLI) and age-matched typically-developing control group, in normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov with Lilliefors significance correction and Shapiro–Wilk p values are >0.05 for both groups). TD: typically developing.

Table 6.

Five discriminant functions including subject expression, MLUw, grammaticality choice and elicited production tense results.

In Table 6, the classification statistics of five distinct discriminant functions computed from our variables are reported. In the second row, we see that null subject use by itself has an accuracy of 67.5%. Thus, this discourse-sensitive measure, by itself, does not identify children with high levels of accuracy. In the third row, we see that MLUw by itself, which is a hybrid measure of both discourse-sensitive and discourse-insensitive morphemes, produces 87.5% correct identification of children, with the SLI identification (sensitivity) being very high (95%, 19/20) and with correct identification of TD children (specificity) substantially lower (80%, 16/20). In the fourth row, we see that two tense measures produce fair accuracy (80.8%), which, in contrast to MLUw, is more accurate in identifying the TD children (specificity—92.9%, 13/14) than the SLI children (sensitivity—66.7%, 8/12). In the fifth row, we see discourse-sensitive constructions only (subjects and the two tense measures) produce 84.6% accuracy, which is relatively balanced between sensitivity (83.3%, 10/12) and specificity (85.7%, 12/14). In the last row, we see that a function consisting of our three discourse-sensitive measures as well as our hybrid discourse-sensitive/discourse-insensitive measure, MLUw, produces a highly accurate 92.3% classification that is balanced between sensitivity (91.7%, 11/12) and specificity (92.9%, 13/14).

This fifth discriminant function yields discrimination above the 90% level, which Plante and Vance (1994) characterize as a “good” level of sensitivity and specificity. For this function, the overall Chi-square test was significant (Wilks λ = 0.296, Chi-square = 26.790, df = 4, Canonical correlation = 0.839, p < 0.001) and the function accounted for 70% of the variance in diagnosis. The standardized canonical discriminant function coefficients, illustrated in Table 7, were, in descending order, subjects (−0.603), elicited production of tense (0.597), MLUw (0.529) and grammaticality choice test of tense (0.159). The structure matrix values, given in the third column of Table 7 are roughly consistent with the standardized coefficients in the sense that subjects, MLUw and the elicited production measure of tense were the most effective variables at distinguishing children in the two diagnostic categories.

Table 7.

Standardized canonical discriminant function coefficient and structure matrix for the discourse sensitive function.

10. Discussion

In this study, we have reviewed evidence for the claim that typically-developing child Spanish-speakers pass through a no-overt subject stage. Two different research groups looking at the question from before children get to MLUw levels of 1.5, or so, indeed find in 11 children’s spontaneous production data that such a stage exists. Perhaps of more interest to understanding the differences between the syntax of overt subjects in the two language types, the same two groups show that these 11 children begin using overt subjects at the same time that they begin using other plausibly left-peripheral constructions, including wh- questions and fronted objects. To make it clear that not all syntactic constructions arise at the same time in all languages, Grinstead and Spinner (2009) show that overt subjects in child German, an overt subject language, begin to be used significantly earlier than do wh- questions or fronted objects. We take this to be strong confirmation that the Interface Delay Hypothesis is correct in its predictions that definite NPs, including null subjects, should be overused in child language, as has been documented at least since Piaget’s observation of “egocentric” linguistic behavior (Piaget 1929).

Note that this situation is starkly different from child English. Child Spanish-speakers are presented with input that overwhelmingly uses null subjects–pronominal definites. Child English-speakers are overwhelmingly presented with overt subject utterances. What unifies the two phenomena is that child English speakers probably use a nonfinite PRO, driven by non-adultlike tense marking. They cannot license overt subjects because they lack the means to assign structural nominative Case to subject position. The tense deficit, on our account, stems from their overuse of a kind of definite tense form, to wit, the Eat cheese type we referred to in examples (13b), (14b), and (15b). This kind of production from children has highly visible, noticeable syntactic consequences in child English because adult listeners expect an overt subject every time. Something similar is highly likely to occur in Spanish, but it is much less noticeable because it is impossible to phonetically distinguish between PRO and pro. Further, the syntax of null subjects in spanish is different and far from settled science, though it may involve incorporation of tense and a pronominal subject into the verb, if Ordóñez (1997) is correct, which could have dramatic consequences for acquisition. We do not ultimately know if occurring in a specifier position is harder to learn or easier to learn than is pronominal incorporation. Our ability to make this determination empirically seems limited. As to why child English speakers do not choose overuse of null subjects as an instance of overuse of definites, it would be because they are not exposed to them. They are not in the input, at least not of the same quality or in the same quantity that exists in Spanish.

Turning to our research questions, we can say that (1) yes, monolingual child Spanish-speakers with SLI use significantly more null subjects than do typically-developing age controls; (2) yes, null subject use appears able to play a role in forming a discriminant function capable of identifying Spanish-speaking children with SLI and (3) yes, adding MLUw to a discriminant function that consists of discourse-sensitive grammatical morphemes increases its accuracy, as in Bedore and Leonard (1998) and Moyle et al. (2011).

The fact that monolingual child Spanish-speakers with SLI use more null subjects than do age-matched controls is very reminiscent of the results presented in Grinstead et al. (2013) showing that child Spanish-speakers with SLI use more root nonfinite verbs than do typically-developing age-matched controls. In both cases, there is a linguistic phenomenon of delayed development relative to other dimensions of language (e.g., nominal plural marking and noun-adjective agreement) that is characteristic of typically developing child Spanish-speakers, which is more severe and prolonged in child Spanish-speakers with SLI. As we have attempted to make clear, we believe that both phenomena stem from the same root cause, namely, Interface Deficit. On that note, it is interesting to observe that the discriminant function in Table 6 consisting of Subjects and the two tense measures achieved relatively balanced, “fair” sensitivity (83.3%) and specificity (85.7%) of 84.6%. Crucially, the function created by the sum of these three measures is superior to the two tense measures by themselves (80.8%) or subjects by themselves (67.5%). This is theoretically interesting because though null subject use is a function of the nominal domain and tense is a function of the verbal domain, they share anaphoric reference as a common trait for determining use of a morpheme. As alluded to above, null subjects are used in Spanish, among other reasons, when the speaker’s model of the interlocutor’s representation of the Conversational Common Ground presupposes shared knowledge of the identity of the antecedent. Similarly, verb tense seeks to express the relationship between speech time and event time, to maintain discourse coherence with conversational participants. Once a speech time-event time relationship is fixed for a stretch of discourse, verb tense refers back to that event time anaphorically (e.g., Reichenbach 1947; Bittner 2011). Perhaps the difference in nominal vs. verbal anaphora is such that the variance in children’s use of each construction is somewhat unique, which allows for greater precision of identification in a combined discriminant function. Though SLI likely has more than one locus and more than one subtype, we nonetheless aspire to add additional discourse-sensitive constructions to future discriminant functions in hopes of improving accuracy to see how far this dimension of SLI can take us on the road to improved diagnosis.

On another note, the fact that child Spanish-speakers with SLI showed differences from typically-developing children even in unstructured discourse may mean that this is a particularly sensitive construction for them. That is, structured spontaneous production techniques, including story retell, tend to produce high rates of errors per t-unit in Spanish, as in Restrepo (1998), which were high enough to produce significant differences between TD and SLI groups. In Grinstead et al. (2013), however, we showed that errors per t-unit in transcripts resulting from our unstructured spontaneous production technique did not produce significant differences between TD and SLI groups. Thus, children with SLI appear to produce fewer errors in unstructured discourse than they do in structured discourse. That being the case, if they produce more null subjects than do TD controls, even in unstructured discourse, it suggests that the use of the construction may not be something that can be easily compensated for.

In future studies of subject use, we hope to look more in detail at the discourse-pragmatic functions of overt subjects. While we have shown that raw proportions do vary across SLI and TD groups, it remains to be seen whether the distributions of these subjects are similar or different across the same groups.

Author Contributions

B.F.-Á, M.C.-S., M.V.-M. and J.D.l.M. collected the data. P.L., A.P., M.C.-S., M.V.-M. and J.D.l.M. analyzed certain parts of the data. J.G. conceived of the project, did the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript, in conjunction with the rest of the team.

Funding

This study was supported by an Arts and Sciences Innovation Grant from The Ohio State University to the first author, as well as by an Undergraduate Research Fellowship to the third author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Silvia Romero for her discussion of the BELE and to Laida Restrepo for discussions of our errors per t-unit results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results’.

References

- Aguado Alonso, Gerardo. 2000. El desarrollo de la morfosintaxis en el niño. Madrid: Ciencias de la Educación Preescolar y Especial. [Google Scholar]

- Aguado-Orea, Javier, and Julian M. Pine. 2002. There is no evidence for a ‘no overt subject’ stage in early child Spanish: A note on Grinstead (2000). Journal of Child Language 29: 865–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1998. Parameterizing AGR: Word order, v-movement and EPP checking. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 16: 491–539. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Shanley E. M. 2000. A discourse-pragmatic explanation for argument representation in child Inuktitut. Linguistics 38: 483–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Raquel T., and Sofía M. Souto. 2005. The use of articles by monolingual Puerto Rican Spanish-speaking children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics 26: 621–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinucci, Francesco, and Domenico Parisi. 1973. Early Language Acquisition: A Model and Some Data. In Studies in Child Language Development. Edited by Charles A. Ferguson and Dan I. Slobin. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, pp. 607–19. [Google Scholar]

- Avram, Larisa, and Martine Coene. 2009. Early subjects in a null subject language. In New Directions in Language Acquisition: Romance Languages in the Generative. Edited by Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes and Laura Domínguez. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 189–217. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark. 1985. The mirror principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 373–415. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark. 1996. The Polysynthesis Parameter. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Elizabeth. 1976. Language and Context: The Acquisition of Pragmatics. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bedore, Lisa M., and Laurence B. Leonard. 1998. Specific Language Impairment and Grammatical Morphology: A Discriminant Function Analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 41: 1185–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bel, Aurora. 2003. The syntax of subjects in the acquisition of Spanish and Catalan. Probus 15: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, Maria. 2011. Time and Modality Without Tense or Modals. In Tense Across Languages. Edited by Renate Musan and Monika Rathert. Tübingen: Niemeyer, pp. 147–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Lois, Peggy J. Miller, and Lois Hood. 1975a. Variation and reduction as aspects of competence in language development. In Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology. Edited by Anne D. Pick. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, vol. 9, pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Lois, Patsy M. Lightbown, and Lois Hood. 1975b. Structure and variation in child language. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 40: 1–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Paul. 1991. Subjectless sentences in child language. Linguistic Inquiry 21: 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Paul. 1993. Grammatical continuity in language development: The case of subjectless sentences. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 721–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, David C., Marsha Maxwell, Richard A. Andersen, Martin S. Banks, and Krishna V. Shenoy. 1996. Mechanisms of heading perception in primate visual cortex. Science 273: 1544–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Roger W. 1973. A First Language: The Early Stages. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Roger W., and Colin Fraser. 1964. The acquisition of syntax. In The Acquisition of Language. Edited by Ursula Bellugi and Roger W. Brown. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 43–78. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, José A. 2013. Null Subjects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas, Lourdes. 1999. El sujeto en el Catalán coloquial. Revista Española de Lingüística 29: 105–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures On Government And Binding: The Pisa Lectures. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, Patricia. 1997. Discourse motivations of referential choice in Korean acquisition. In Japanese/Korean Linguistics. Edited by Ho-min Sohn and John Haig. Stanford: CSLI, vol. 6, pp. 639–59. [Google Scholar]

- De la Mora, Juliana, Johanne Paradis, John Grinstead, Blanca Flores, and Myriam Cantú-Sánchez. 2003. Object Clitics in Spanish Speaking Children with and without SLI. Presented at the Symposium for Research on Child Language Disorders, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- De la Mora, Juliana. 2004. Direct Object Clitics and Determiners in Spanish Specific Language Impairment. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss, Joseph L. 1971. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin 76: 378–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, Jerry A. 1983. Modularity of Mind. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerken, LouAnn. 1991. The metrical basis for children’s subjectless sentences. Journal of Memory and Language 30: 431–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, LouAnn. 1994. Young children’s representations of prosodic phonology: Evidence from English speakers’ weak syllable productions. Journal of Memory and Language 33: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, Bernard. 2003a. Production-Based Theories May Account for Subject Omission in Both Normal Children and Children with SLI: A Case Study. Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology 27: 221–28. [Google Scholar]

- Grela, Bernard. 2003b. The omission of subject arguments in children with specific language impairment. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 17: 153–69. [Google Scholar]

- Grela, Bernard, and Laurence B. Leonard. 1997. The Use of Subject Arguments by Children with Specific Language Impairment. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 11: 443–53. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead, John. 1998. Subjects, Sentential Negation and Imperatives in Child Spanish and Catalan. Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead, John. 2000. Case, Inflection and Subject Licensing in Child Catalan and Spanish. Journal of Child Language 27: 119–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinstead, John. 2004. Subjects and Interface Delay in Child Spanish and Catalan. Language 80: 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John, Myriam Cantú-Sánchez, and Blanca Flores-Avalos. 2008. Canonical and Epenthetic Plural Marking in Spanish-Speaking Children with Specific Language Impairment. Language Acquisition 15: 329–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John, Juliana De la Mora, Mariana Vega-Mendoza, and Blanca Flores-Avalos. 2009. An Elicited Production Test of the Optional Infinitive Stage in Child Spanish. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference of Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition—North America. Edited by Jean Crawford, Koichi Otaki and Masahiko Takahashi. Storrs: Cascadilla Press, pp. 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead, John, Alisa Baron, Mariana Vega-Mendoza, Juliana De la Mora, Myriam Cantú-Sánchez, and Blanca Flores. 2013. Tense marking and spontaneous speech measures in Spanish specific language impairment: A discriminant function analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 56: 352–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John, Paij Lintz, Mariana Vega-Mendoza, Juliana De la Mora, Myriam Cantú-Sánchez, and Blanca Flores-Avalos. 2014. Evidence of optional infinitive verbs in the spontaneous speech of Spanish-speaking children with SLI. Lingua 140: 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, J., Jeff MacSwan, Susan Curtiss, and Rochel Gelman. 1998. The Independence of Language and Number. In BUCLD 22: Proceedings of the 22nd annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Annabel Greenhill, Mary Hughes, Heather Littlefield and Hugh Walsh. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 303–13. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead, John, and Patti Spinner. 2009. The Clausal Left Periphery in Child Spanish and German. Probus 21: 51–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilfoyle, Eithne. 1984. The Acquisition of Tense and the Emergence of Lexical Subjects. Montreal: McGill University. [Google Scholar]

- Guilfoyle, Eithne, and Máire Noonan. 1992. Functional categories and language acquisition. Canadian Journal of Linguistics/Revue canadienne de Linguistique 37: 241–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, Cornelia. 1996. Null arguments in German child language. Language Acquisition 5: 155–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, Cornelia, and Kim Plunkett. 1998. Subjectless sentences in child Danish. Cognition 69: 35–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Klaus Krippendorf. 2007. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures 1: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, Nina. 1986. Language Acquisition and the Theory of Parameters. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, Nina. 2011. Missing subjects in early child language. In Handbook of Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition. Edited by Jill G. De Villiers and Thomas Roeper. New York: Springer, vol. 41, pp. 13–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, Nina, and Kenneth Wexler. 1993. On the Grammatical Basis of Null Subjects in Child Language. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 421–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, Ray S. 1987. Consciouness and the Computational Mind. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, Ray S. 1997. The Architecture of the Language Faculty. Cambridge: Massachusetts Instit Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klecka, William R. 1980. Discriminant Analysis. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences Series; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Irene. 1993. The licensing of subjects in early child languages. In Papers on Case and Agreement II. Edited by Colin Phillips. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, vol. 19, pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J. Richard, and Gary G. Koch. 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33: 159–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, Laurence. 2014. Children With Specific Language Impairment. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M., Aurora Bel, and Susana Perales. 2006. ‘Living with Optionality’: Root Infinitives, Bare Forms and Inflected Forms in Child Null Subject Languages. In Selected Proceedings of the 9th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Nuria Sagarra and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 203–16. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, Diane F., and Laurence B. Leonard. 1988. Specific Language Impairment and Parameter Theory. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 2: 317–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, Paolo, Claudia Caprin, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2004. Overt Subject Distribution in Early Italian Children. In A Supplement to the Proceedings of Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Alejna Brugos, Manuella R. Clark-Cotton and Seungwan Ha. Somerville: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Maratsos, Michael P. 1974. Preschool children’s use of definite and indefinite articles. Child Development 45: 446–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maratsos, M.P. 1976. The Use of Definite and Indefinite Reference in Young Children: An Experimental Study of Semantic Acquisition. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, Barbara J. 1983. Language development in normal and language handicapped Spanish-speaking children. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 5: 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, Maura J., Courtney Karasinski, Susan Ellis Weismer, and Brenda K. Gorman. 2011. Grammatical morphology in school-age children with and without language impairment: A discriminant function analysis. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 42: 550–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, William, Ann M. Peters, and Deborah Materson. 1989. The transition from optional to required subjects. Journal of Child Language 16: 513–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oetting, Janna B. 1993. Language-Impaired and Normally Developing Children’s Acquisition of English Plural. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting, Janna B., and Mabel L. Rice. 1993. Plural Acquisition in Children with Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 36: 1236–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordóñez, Francisco. 1997. Word Order and Clause Structure in Spanish and Other Romance Languages. Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez, Francisco, and Esthela Treviño. 1999. Left Dislocated Subjects and the Pro-Drop Parameter: A Case Study of Spanish. Lingua 107: 39–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfitelli, Robyn, and Nina Hyams. 2008. An Experimental Study of children’s comprehension of null subjects: Implications for grammatical/performance accounts. In BUCLD 32: Proceedings of the 32nd annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Harvey Chan, Heather Jacob and Enkeleida Kapia. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 335–46. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ana C. Zentella, and David Livert. 2007. Language and Dialect Contact in Spanish in New York: Toward the Formation of a Speech Community. Language 83: 770–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, and Ana C. Zentella. 2012. Spanish in New York: Language Contact, Dialectal Leveling and Structural Continuity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, Jean. 1929. The Child’s Conception of the World. London: Kegan Paul Trench Trubner. [Google Scholar]

- Plante, Elena, and Rebecca Vance. 1994. Selection of preschool language tests: A data-based approach. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 4: 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb Movement, Universal Grammar and the Structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 365–424. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, Andrew. 1990. Syntactic Theory and the Acquisition of English Syntax. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel, Elena, Silvia Romero, and Margarita Gómez. 1988. Batería de evaluación de la lengua española para niños de 3 a 11 años: Manual de aplicación, calificación e interpretación. Mexico City: Secretaría de Educación Pública, Dirección General de Educación Especial. [Google Scholar]

- Rauschecker, Josef P., Biao Tian, and Marc Hauser. 1995. Processing complex sounds in the macaque nonprimary auditory cortex. Science 268: 111–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichenbach, Hans. 1947. Elements of Symbolic Logic. New York: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, María A. 1998. Identifiers of Predominantly Spanish-Speaking Children with Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 41: 1398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restrepo, María A., and Vera F. Gutiérrez-Clellen. 2001. Article Use in Spanish-Speaking Children with Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Child Language 28: 433–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, Mabel L., and Kenneth Wexler. 1996. Toward Tense as a Clinical Marker of Specific Language Impairment in English-Speaking Children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 39: 1239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, Mabel L., Kenneth Wexler, and Scott Hershberger. 1998. Tense over Time: The Longitudinal Course of Tense Acquisition in Children with Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 41: 1412–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, Mabel L., Kenneth Wexler, and Sean M. Redmond. 1999. Grammaticality Judgments of an Extended Optional Infinitive Grammar: Evidence from English-Speaking Children with Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 42: 943–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero, Maria Luisa, and Arhonto Terzi. 1995. Imperatives, V-movement and Logical Mood. Journal of Linguistics 31: 301–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1993. Some Notes on Linguistic Theory and Language Development: The Case of Root Infinitives. Language Acquisition 3: 371–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The Fine Structure of the Left Periphery. In Elements of Grammar: Handbook in Generative Syntax. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 281–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 2005. On the grammatical basis of language development: A case study. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 70–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Tetsuya, and Nina Hyams. 1994. Agreement, Finiteness and the Development of Null Arguments. In NELS 24: Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society. Edited by Mercè González. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, pp. 544–58. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, Miquel, and Rosa Solé. 1986. Language Acquisition in Catalan and Spanish Children. Unpublished Research Project Manuscript. Universitat de Barcelona; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Serratrice, Ludovica. 2005. The role of discourse pragmatics in the acquisition of subjects in Italian. Applied Psycholinguistics 26: 437–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi L., and Helen S. Cairns. 2012. The development of NP selection in school-age children: Reference and Spanish subject pronouns. Language Acquisition: A Journal of Developmental Linguistics 19: 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, William. 2001. On the Nature of Syntactic Variation: Evidence from Complex Predicates and Complex Word-Formation. Language 77: 324–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, William, and Karin Stromswold. 1997. The Structure and Acquisition of English Dative Constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 28: 281–317. [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker, Robert. 1974. Pragmatic Presuppositions. In Semantics and Philosophy. Edited by Milton K. Munitz and Peter K. Unger. New York: New York University Press, pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg, Helen, and Judith Cooper. 1999. Present and Future Possibilities for Defining a Phenotype for Specific Language Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 42: 1275–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valian, Virginia. 1990. A problem for parameter-setting models of language acquisition. Cognition 35: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valian, Virginia. 1991. Syntactic subjects in the early speech of American and Italian children. Cognition 40: 21–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valian, Virginia, James Hoeffner, and Stephanie Aubry. 1996. Young children’s imitation of sentence subjects: Evidence of processing limitations. Developmental Psychology 32: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-García, Julio, and William Snyder. 2009. On the Acquisition of Overt Subjects, Topics and Wh-Questions in Spanish. In Language Acquisition and Development: Proceedings of GALA 2009. Edited by Ana Castro, João Costa, Maria Lobo and Fernanda Pratas. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 493–504. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, Norman M. 1995. Dynamic regulation of receptive fields and maps in the adult sensory cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience 18: 129–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubizarreta, María Luisa. 1998. Prosody, Focus and Word Order. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Bel’s (2003) month-by-month presentation of the Catalan data of Júlia, in which she uses 7.2% overt subjects in her earliest recording, at MLUw 1.5, is much more consistent with the no-overt subject stage claim than with the claim that she is using overt subjects in adult-like proportions (38% according to Casanovas 1999). |

| 2 | A similar early No Overt Subject Stage is reported for Italian in Grinstead (1998) and for Romanian in Avram and Coene (2009). |

| 3 | The generic term “fronted objects” is used instead of the more specific focused objects (ESTO quiero yo ‘This I want’) or topicalized object (Esto, lo quiero ‘This I want’) because the two constructions are distinguished in adult Spanish by the presence of an accusative clitic in topicalization constructions, and children in the 2 year-old range are not consistent with their production of such clitics. In the available spontaneous production transcripts, in the absence of a clitic, the two constructions are indistinguishable. |

| 4 | See Grinstead et al. (1998) for an argument that Interface Delay occurs between language and number in the development of the counting process. |

| 5 | Note that MLU measured in words and MLU measured in morphemes correlate at 0.9 in previous studies of Spanish language development (e.g., Aguado Alonso 2000) and are taken to be roughly equivalent measures here. |

| 6 | It appears that there are no absolute predictors of subject occurrence (see Otheguy et al. 2007 on predictors of subject pronoun expression) and children may be substantially older than our participants before they attain adult-like command of these variables (see Shin and Cairns 2012, for example). |

| 7 | See Clancy (1997); Allen (2000) and Serratrice (2005) for discourse-pragmatic analyses of some factors influencing overt subject occurrence in null subject child languages. |

| 8 | These rates are roughly consistent with the 81% null subject expression rate reported for subject pronouns in a small sample of Mexican immigrants to New York in Otheguy et al. (2007), though note that our rate corresponds to all subject noun phrases and not just pronouns, which is plausibly a consequential difference. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).