Abstract

This study dives into the interactive functions of the palm-up across four language ecologies drawing on comparable corpus data from American Sign Language (ASL)-American English and French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB)-Belgian French. While researchers have examined palm-up in many different spoken and signed language contexts, they have primarily focused on the canonical forms and its epistemic variants. Work that directly compares palm-up across modalities and language ecologies remains scarce. This study addresses such gaps by documenting all instances of the palm approaching supination in four language ecologies to analyze its interactive functions cross-linguistically and cross-modally. Capitalizing on an existing typology of interactive gestures, palm-up annotations were conducted using ELAN on a total sample of 48 participants interacting face-to-face in dyads. Findings highlight the multifunctional nature of palm-up in terms of conversational dynamics with cross-modal differences in the specific interactive use of palm-up between spoken and signed language contexts. These findings underscore the versatility of the palm-up and reinforce its role in conversational dynamics as not merely supplementary but integral to human interaction.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Multichanneled, Semiotic Nature of Our Face-to-Face Conversations

When engaging in face-to-face conversations, sighted people direct eye gaze, shift torsos, and configure a diverse range of manual forms while speaking or signing. These moves achieve different functions, some of which specifically regulate conversational dynamics. Speakers and signers have at their disposal numerous ways of synchronizing their articulators to indicate how their interlocutor should take the information they are offering, from describing and depicting ideas to indicating mutual understanding and ensuring the successful unfolding of the interaction itself. The hands constitute one expressive channel through which people interact and have received more attention than other body behaviors (e.g., facial expressions) by scholars interested in multimodal communication (Kendon, 2004). In the field of gesture studies, co-speech gestures—those manual moves that are tightly aligned with speech—have traditionally been divided into propositional and non-propositional types (McNeill, 1992). While propositional gestures are generally seen as enhancing the discourse content, directly tied to the topic at hand, non-propositional gestures are viewed as directed to “improve the development of speech fluidity (McClave, 1994), to manage the conversation from an interactive point of view (Bavelas et al., 1995), and to manage emotional states, such as tension or anxiety (Ekman & Friesen, 1969)” (Maricchiolo et al., 2014, sct 3.1, vol. II, chap. 109, para. 8). The visual–gestural affordances of face-to-face interaction trigger bodily actions that are semiotically complex (Kendon, 2004; Clark, 1996). In addition to articulating propositions, interlocutors track unfolding talk, sending cues of comprehension on-line. Speakers and signers leverage these resources from multiple articulatory channels to tackle the “two tracks” of discourse, which Clark (1996) characterizes as in constant operation when people communicate. The primary track is foregrounded and concerns commentary that is verbally (or gesturally) conveyed, while the secondary, backgrounded track concerns the meta-commentary about the unfolding interaction at hand. Though less noticed due to its backgrounded status, the bodily actions and utterances that operate on this secondary track are essential, in Clark’s view, to the success of conversation.

The field of gesture studies has developed a robust body of knowledge about co-speech gestures that are tightly aligned with speech. Those manual and non-manual forms that primarily signal interlocutors’ attunement to the interaction, while less frequently noticed by analysts or interactants, are central to communication. In their 1992 study, Bavelas and colleagues shed light on a particular set of hand gestures specifically designed for the regulation and coordination of dialogues, which they labeled “interactive”. Interactive gestures do not depict topical content but push forward emerging discourse as interlocutors adapt topical content to each other. Taking turns, marking shifting information states, and expressing stances were found to be expressed visually by manual gestures. Following these observations, Bavelas and colleagues determined that interactive gestures shared some common characteristics. First, at the level of their form, “some part of the hand (a finger, group of fingers, palm, or the whole hand) was, however briefly, directed at the addressee” (Bavelas, 2022, p. 114) and then, within their context of use, these interactive gestures made a direct reference to the addressee and to “what was happening in the dialogue at that moment” (Bavelas, 2022, p. 114). The ways those interactive forms involve the addressee in dialogue are multifaceted. For example, Bavelas et al. (1995) identified manual gestures that interactants used to regulate turn-taking dynamics, particularly signaling shifts between interlocutors and connecting ongoing talk with displaced contextual information. The authors demonstrated in subsequent experiments how such gestures enabled speakers to stay in close contact with their addressee without disrupting the topical flow (see Bavelas et al., 1992, 1995, 2008).

In contrast to the substantial body of work on interactive gestures in spoken language, equivalent studies on signed language interactions are comparatively sparse. Analyzing analogous underpinnings of signed interactions requires distinguishing between manually produced signs, taken to be lexical items, and those forms perceived to be gesture or gesture-like (Shaw, 2019). Deaf signers of signed languages (SLs) manage different interactional facets of their turns and monitor in situ the understanding of their addressees, but they do so exclusively in one modality, albeit multichanneled. While there has been an overall tendency to overlook the study of social interaction and its related mechanisms in SL contexts, an increasing enthusiasm for exploring this area of linguistics has emerged, particularly from a gesture-studies lens (see Lepeut & Shaw, 2024b for a review). To date, special attention in SL studies has been paid to specific interactional aspects of the turn-taking system of different SLs, such as how signers take, maintain and yield the floor via eye gaze, repetition and holding of signs, raising and lowering the hands (e.g., Baker, 1977; Coates & Sutton-Spence, 2001; Girard-Groeber, 2015; Manrique, 2016; McIlvenny, 1995). Studies have also explored how deaf people tend to orient to the one-at-a-time principle, avoiding gaps and overlaps (Beukeleers & Lepeut, 2022; de Vos et al., 2015; McCleary & Leite, 2013; Lepeut & Shaw, 2024a). SL researchers interested in the interactive functioning of SLs have also investigated how deaf signers ensure mutual understanding and initiate effective repair practices when things go awry (Dively, 1998; Lutzenberger et al., 2024). These studies laid the groundwork for exploring the semiotic viability of multiple channels in the visual-gestural modality for deaf signers.

While research on these different interactive components has mostly been conducted on individual SLs, there have been some exceptions of comparisons between SLs and with SpLs. Beukeleers and Lepeut (2022) compared Flemish Sign Language (VGT) and LSFB, and Lutzenberger et al. (2024) investigated continuers and repair initiators in British Sign Language (BSL) and English-speakers. To address the gap between two parallel lines of inquiry into interactive practices—one in SLs and the other in co-speech gesture—scholars are now reconsidering the semiotic complexity of embodied practices among deaf and hearing interactants. Our article sheds light on one recurring form, the palm-up (PU), in four comparable ecological contexts: two pairs of co-located languages in signed and spoken modalities. Exploring the PU across four languages allows us to tease apart actions that are endemic to local ecologies and those that pattern differently across modality. The article is structured in the following way: First, we briefly describe the relationship between SpL and SL research with respect to the field of linguistics, and more specifically, the comparative work between the two. Next, we present the interactional practice investigated here, PU, and focus on relevant literature for this study (for a more comprehensive account of PU, see Cooperrider et al., 2018). The methodology is described in Section 2. This includes an overview of the data as well as information regarding the annotation process. Our findings are presented in Section 3 followed by a qualitative account of concrete instantiations of PU’s interactive roles in French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB), Belgian French (BF), American Sign Language (ASL), and American English (AmEng). Lastly, the results are discussed in Section 4 and situated within broader issues of how we should approach language in a modality agnostic view shaped through the lens of its home habitat, namely, face-to-face interaction.

1.2. Comparative Work on SpL and SL Research

Comparative analyses of SpL and SL interactions have overarching benefits and challenges. Besides acknowledging the legitimacy of SLs in comparison to SpLs, cross-modal and cross-linguistic studies also expand the lens of linguistics in response to critiques that it has been “too short-sighted to the fundamentally heterogeneous nature of the systems and the semiotic resources through which speakers and signers convey meaning” (Gabarró-López & Meurant, 2022, p. 177). Traditionally, comparisons between SpL and SL have centered on a theoretical equivalence made between spoken words and manually produced signs. Some of the earliest linguistic work on ASL, for example, showcased the inherent tension between the depictive affordances of a visual-gestural modality and the conventionality and systematicity of the manual forms deaf signers exhibited. Klima and Bellugi (1979), acknowledging this dichotomy, stated “deaf ASL signers use a wide range of gestural devices, from conventionalized signs to mimetic elaboration on those signs, to mimetic depiction, to free pantomime. The core vocabulary of ASL is constituted of conventionalized lexical signs” (p. 13). We see in this analysis that signs, the core lexicon of ASL, as well as mimetic depiction are considered the central communicative activities conducted by the hands. While there is no doubt that the hands constitute the primary communicative channel in SLs, an unintentional side effect of this viewpoint is that scholars have downplayed the diverse interactive practices afforded by the hands and face when signers engage face-to-face. Additionally, those manual units that are not depictive nor descriptive (e.g., indexes and emblem-like units) have presented challenges to scholars when considering how to analyze their status as akin to co-speech gestures or spoken words (Liddell, 2003; Wilcox, 2009; Emmorey, 1999).

As we and others have pointed out (see Cienki, 2023; Kendon, 2008), interactions between hearing people include semiotic resources from various channels beyond the vocal tract and thus can be analogized to signed language as multimodal linguistic systems (Kendon, 2008). From this vantage point, “visible bodily actions” (Kendon, 2004) can be directly compared from the same channel across deaf and hearing populations. Expanding the perspective of all languages as embodied enterprises opens the door to direct comparative work, especially with respect to manual gestures. Gesturing has been shown to vary based on ecological contexts. Due to the way deafness manifests, deaf people live among and within larger hearing populations. It is no surprise, then, that gesturing is frequently a communicative channel that deaf and hearing people turn to when interacting with each other face to face (Kusters, 2017). Studies have shown that speakers and signers tend to employ similar practices within the same language ecology, like the recent study on repair initiators and continuers in BSL and British English (Lutzenberger et al., 2024; see also Kusters, 2017). Highly conventionalized gestures that tend to be shared within local language ecologies have been identified as crossing modality barriers (Haviland, 2015; Kendon, 2004; Shaw & Delaporte, 2015). Kendon’s (2004) early documentation of gesture families is a foundational work on cross-linguistic comparison of the PU (among other forms). Comparisons of interactional practices across geographically displaced contexts are less common (see Stivers et al., 2009) but are beginning to reveal patterns of diversity and universality among some forms.

Despite acknowledged benefits of cross-linguistic work, the concerted effort to conduct these comparisons between SpLs and SLs (cross-linguistically within the same ecology but also across different language ecologies) is scarce in part because of the lack of directly available corpus data. Creation of corpora is notoriously labor-intensive for multimodal datasets (Fenlon & Hochgesang, 2022). In recent years, we have seen projects devoted to studying ambient SpLs and SLs (see Hodge et al., 2019 for Auslan and Australian English; Lepeut et al., 2024 for LSFB and BF; Parisot et al., 2008 for Quebec Sign Language, French, ASL and English with the project Marqspat). In this study, we are taking the different incentives made by previous researchers to add our contribution by offering a direct cross-linguistic and cross-modal comparison of PU in hearing speakers of AmEng and BF and deaf signers of ASL and LSFB.

1.3. The Case of PU

The palm-up (PU) has been defined as a recurrent gesture in multiple languages that is “grounded in actions of giving, receiving, and showing objects on the open hand and involves a metaphorical operation of those objects” (Müller, 2018, p. 291). It has been documented by scholars of both modalities as having a wide range of functions but above all its role in interaction management is widely acknowledged. Even though PUs emerge “in all their ubiquity and multiplicity of meanings”, they are still “a critical case study for scholars of visual-bodily communication” (Cooperrider et al., 2018, p. 2).

In the field of ASL linguistics, the PU has appeared since Stokoe et al.’s (1965) groundbreaking dictionary where it is translated as a formal interrogative “what” (p. 38). Notably, and particularly relevant to our study, the authors point out that the form “can mean ‘Well?’, or ‘How should I know?’, ‘Who can tell?’” (p. 38). The polysemy of this unit appears in various SLs, where the PU is implicated in asking questions as well as expressing lack of knowledge in response to a question. In ASL two separate items—WHAT and WELL—appear in studies of social interaction (Baker, 1977; Wilbur & Petitto, 1983; Hoza, 2011). Baker (1977) documents one sequence of turns from a conversation between two deaf women in which two instances of PU are transcribed: the first glossed as WELL and the second as palma [the subscript “a” is a transcription convention describing palms in supinated orientation].

| Mary: | …NOT UNDERSTAND WELL? | <— |

| […You don’t understand?] | ||

| Lisa: | [no response] | |

| Mary: | (lowers hands, palmsa) [PU] | <— |

| Lisa: | (begins response) |

Baker characterizes the question “NOT UNDERSTAND WELL?” as “carried by a forward tilting of the head and a concomitant hunching of the shoulders on the sign WELL” (1977, p. 220). Based on the sequential position, it is likely that this instance of WELL functioned to transition the turn to the next signer. Baker continues, “As [Mary] first calls for Lisa to respond by switching the orientation of the palms to ‘a’ [PU] and then signs the end of her turn by lowering her hands, Lisa initiates her response” (1977, p. 220). Here, we surmise that the PU is signaling the close of Mary’s turn (without video of the co-occurring facial expressions, it is not possible to determine if the signer was also expressing a stance). Two important points from Baker’s example relate to our treatment of PU in this study. First, the item glossed WELL since as early as 1965 (Stokoe et al., 1965) is described as having the same form as the PU and in some cases (like the one cited above) the same interactive function. It is not possible to check whether the terminological distinction reflects actual differences in form because these data are solely written representations of signed interactions. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consider the ways in which lexicalized units (such as WHAT and WELL) might be distinguished from interactional ones. The second point is that it appears that these (and later works, such as Hoza, 2011) see the PU as serving additional interactive functions particular to turn-taking that extend beyond prototypical functions like question asking.

The SL literature contains inconsistencies in documentation of the PU form (see also Shaw, 2019 for a discussion). Additionally, the interrogative sign, glossed WHAT-PU (Figure 1) in the ASL Signbank (Hochgesang et al., 2025), has reached full conventional status and stands apart from interactive forms in two ways:

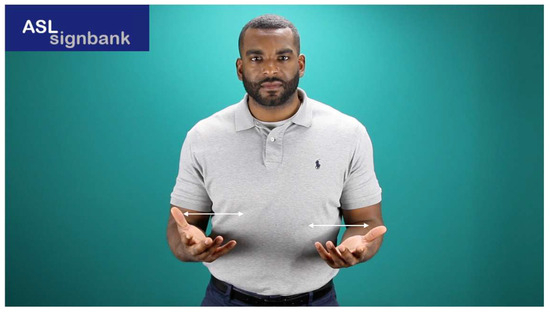

Figure 1.

ASL sign WHAT-PU (ASL Signbank, 2025).

(1) In ASL and LSFB, the hands move back-and-forth that indicates the asking of a question, and (2) the sign occurs as a semantic constituent in utterances (e.g., as an interrogative, determiner, or relative pronoun). Though undoubtedly linked to the PU historically, WHAT-PU is semantically and pragmatically distinct from the interactive instances of interest here.

Despite complexities in distinguishing between lexical units and interactive units, there seem to be similar interactive functions of PUs observed in SLs and SpLs which invites a closer look to cross-modal comparisons. Therefore, selecting PU as the main unit of analysis offers “one possible starting point for a systematic comparison […] from a gesture studies point of view” (Müller, 2018, p. 15), bridging the gap between gesture, sign, and language writ large. And yet, the bulk of research dedicated to the analysis of PU lacks substantial contrastive approaches, that is, not only comparisons of PUs between several SpLs and SLs, respectively, but also analyses of SpLs contrasted with SL data to obtain results across languages and modalities: “[PU analyses] have sometimes been made in mutual isolation from each other, often using different analytic frameworks and pursuing different ends. Work on palm-ups as used by speakers, for instance, has often been carried out independently from work on palm-ups as used by signers.” (Cooperrider et al., 2018, p. 2). Our study seeks to correct this gap by providing comparisons cross-linguistically and cross-modally.

While we know the PU is used in both deaf and hearing interactions, there remains a lack of understanding as to the specific interactive functions accomplished with it, and whether these functions are comparable across distinct languages. Previous research points to the fact that, unlike propositional gestures, PUs are “interactional in nature” (Cooperrider et al., 2018, p. 5) as they “perform interactional moves on the discourse structures of everyday conversations and are thus closely tied to it” (Teßendorf, 2014, p. 1544). Several accounts in gesture and SL research have shed light on multiple discourse functions including—but not limited to—expressing stance, creating cohesive and coherent relations, and regulating turns. While most studies have focused on the textual, structuring, and modal functions, interactional ones remain less documented by comparison. And because differences between ecological contexts have been overshadowed, there remains the possibility for diverse instantiations of its use that have thus far evaded description.

In sum, we are interested in how the unit of study contributes to the social management and coordination involved in signed and spoken face-to-face conversation. Zooming in on the social functions of PU, which will give us key insights into the ongoing interaction as well as the management of the interpersonal relationship between speakers/signers and addressees, will inform us about the dialogic exchange itself (Bavelas, 2022).

1.4. Current Study: Aims and Research Questions

In addition to approaching the PU from an interactive perspective, this paper responds to the call for more “systematic cross-linguistic research on the multimodal use of language in its signed and spoken forms” (Müller, 2018, p. 2). By approaching the data agnostic to modality, we foreground the interactive functions as the starting point of the analysis. In this study, we explore the PU across hearing and deaf interactions in four ecological contexts to describe interactive patterns and their association between co-located language pairs (BF and LSFB; ASL and AmEng) and between modalities (SpLs and SLs). Our research questions consider how the PU operates across deaf and hearing groups as well as across language ecologies to take a granular look at the functions of the form when used interactively. First, we ask what interactive functions does the PU exhibit across these four languages? Second, we ask what interactive functions are most salient across ecological contexts? In other words, at what level of the management and coordination of SL vs. SpL interactions does the PU operate?

The objectives of this article are the following: (i) to describe the frequencies of PU in the discourse of signers and speakers from different language ecologies, (ii) to zoom in on its interactive roles within and across the languages under study, (iii) and ultimately, to compare the results across spoken/signed interactions and languages (AmEng/ASL–BF/LSFB) to offer a more comprehensive understanding of PU in language use.

2. Materials and Methods

Face-to-face interaction is a complex area of language to study. From a purely methodological standpoint, even filming bodily actions produced by interactants when they position themselves in spaces to talk presents a challenge (Bavelas, 2022). Even so, it remains one of the richest instantiations of language use and arguably the quintessential place to study it (Schegloff, 1996). As video recording technology and analytical software has advanced considerably, we now have a growing interest in the multimodal as well as the interactional aspects of language use, whether in spoken as well as signed language ecologies.

Together with the field of gesture studies, SL linguists have developed methods for annotating and analyzing multi-channeled linguistic systems (see Fenlon & Hochgesang, 2022 for an overview) and are uniquely positioned to contribute a richer understanding of how humans—deaf and hearing alike—use their bodies to communicate in meaningful ways. In this study, prior insights gained from preliminary analyses conducted on the recurrent patterning of PU in Lepeut and Shaw (2022) have led us to conduct this analysis to underscore systematic patterns regarding its use and interactive roles. The data selected here are drawn from four existing datasets: (1) the LSFB Corpus (Meurant, 2015), the FRAPé Corpus (Lepeut et al., 2024), and the Deaf Stories Collection (2017) from CARD (Collections of ASL for Research and Documentation) (Hochgesang, 2020) as well as a newly collected dataset of dyadic conversations for AmEng. Each dataset is presented next followed by details regarding the annotation process and analyses.

2.1. Dataset Description

2.1.1. The LSFB—Belgian French Datasets

The LSFB Corpus (Meurant, 2015) is a machine-readable, publicly accessible database online (https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/, accessed on 1 September 2024). It contains approximately 88 h of LSFB recordings including 100 LSFB signers. To achieve a representative sample of the LSFB deaf community in the French-speaking part of Belgium, participants were balanced according to different sociolinguistic aspects (e.g., age, LSFB acquisition profiles, gender, and place of origin in the area of Brussels and Wallonia). The Corpus material comprises dyadic video recordings of the participants engaged in a series of tasks (19 in total) to elicit different discourse types such as narration, explanations, descriptions, argumentations, and spontaneous conversations. Detailed information about the sampling method and the metadata can be found on the Corpus website. For the purposes of this study, a total of 12 LSFB participants were selected. Out of the 19 tasks available in the Corpus, we chose conversational tasks that reflected the dialogic characteristic of spontaneous conversations along with the direct compatibility and comparability with the other three datasets. The topics discussed ranged from recounting childhood memories to discussing cultural differences between deaf and hearing individuals. The FRAPé Corpus (Lepeut et al., 2024, 2025) was built following the same sampling method as the LSFB Corpus. To date, it is made up of dyadic interactions between 30 hearing Belgian French speakers (7 men and 23 women), totaling roughly 24 h of data. All participants are native speakers of French (variety used in Belgium). The data collection process is currently ongoing. FRAPé is directly comparable to the LSFB Corpus in terms of discourse types, participants and recording environment, so that direct comparative work between both languages can be done. Only one minor adjustment was made regarding a task where BF speakers discussed cultural differences between Walloon and Flemish people in Belgium rather than cultural differences between deaf and hearing individuals. For this study, we sampled 12 participants discussing the same conversational topics as those in the LSFB dataset. For a more thorough description of the directly comparable nature of the LSFB and FRAPé Corpora, see Lepeut et al. (2024, 2025).

2.1.2. The ASL—American English Datasets

The ASL data were collected and recorded on Gallaudet University’s campus as part of a project conducted by the Deaf Studies Department during the university’s 150th anniversary event in 2014. A diverse group of deaf Gallaudet alumna were interviewed by deaf research assistants in dyads and in some cases triads. The semi-structured interviews focused largely on the participants’ experiences at Gallaudet, cultural differences between hearing and deaf spaces, and their early memories related to being deaf. Portions of these videos have been annotated as part of an ongoing ASL corpus development that is housed under CARD. For the purposes of this study, videos of 12 signers (7 men, 5 women) were selected from the larger collection of 87 interviews. Interviews lasted from approximately 10 to 32 min and covered topics related to memories at Gallaudet and cultural differences between deaf and hearing people. We analyzed the segments of the conversations that covered childhood memories and cultural differences. The AmEng dataset was created for the purpose of the current study to match the conversational nature of the other datasets. We collected the material in 2021 in Washington, D.C. A total of 12 hearing, non-signing, AmEng speakers (4 men, 8 women) in pairs were video recorded in their homes (due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were unable to record at the university). Participants discussed a similar range of topics as those in the other datasets such as childhood memories, cultural differences in Washington, D.C., hobbies, and historical moments. These interviews lasted from 32 min to just over an hour. All data were collected with permission of the Gallaudet University’s Institutional Review Board.

In total, we selected 12 participants per language totaling 48 individuals for this study. It is worth noting that all participants knew each other prior to the data collection process. They also gave written consent for their data to be used for research, in publications, as well as for teaching activities. For practical purposes in terms of comparability, 10 to 15-min data samples per pair of participants in each dataset were chosen for annotation and analyses. In addition, we balanced for age across each of the language groups—selecting two pairs of younger, middle-aged, and older adults.

2.2. Data Annotation and Coding

As Cooperrider et al. (2018) note, PU remains a puzzling form as its functions and meanings vary considerably across contexts. Furthermore, in prior research, focus has largely been on canonical instances and their epistemic variant linked to modal functions, leaving aside other, less conventional forms (e.g., the retracted PU with thumb and index extended) and interactional uses. Similarly, works on PU in SLs and SpLs have often been conducted independently from each other, “often using different analytic frameworks and pursuing different ends” (Cooperrider et al., 2018, p. 2). So, methodologically speaking, two main issues remain when comparing PU across different languages, namely, a lack of comparable datasets in a SL and a SpL, and variable descriptions of PU forms. To address these gaps, the comparable corpora across the four languages under study serve as a strong basis for direct analyses of PU across SpL and SL contexts (Hodge et al., 2019; Lepeut et al., 2024). For the current study, 4 h of face-to-face conversations consisting of 48 participants in total were analyzed. Once the data samples were selected, videos were imported into ELAN for annotation. The following section describes the annotation process and coding.

2.2.1. Identification of PU Forms

The canonical PU showcases one or two flat hand(s) with the fingers more or less extended, and the wrists rotating outward until the palms are oriented in upward position in front of the speaker’s/signer’s body. Next to this canonical form, other less conventional forms of PU can occur. In this study, following Cienki’s (2021) and adopting an inductive approach, we identified all instances of the palm approaching supination with respect to the onset of the stroke (Kita et al., 1998) including those candidates where only certain fingers extended (e.g., the thumb and index extended) as well as reduced forms of PU occurring on the person’s lap. Rotating, cyclic PU gestures were excluded as they perform a different pragmatic function and are known as a distinct category of recurrent gestures (Ladewig, 2011).

2.2.2. Identification of PU Functions

After identifying all instances of PU, the next stage consisted of attributing the interactive functions to them. To achieve this, we first conducted the functional annotation by classifying PU instances as either interactive or non-interactive. At this stage, we excluded all instances of WHAT-PU. Next, focusing specifically on the interactive units, we identified the type of interactive functions each PU token exhibited. We drew from pre-established typologies for interactive gestures (Bavelas et al., 1992, 1995) and adapted Bolly and Crible’s (2015) typology for the annotation of multimodal discourse markers, which is also based on Bavelas and colleagues’ work (see Appendix A). These typologies have been priorly successfully applied to both SpL and SL data, including PU, facilitating corpus-based contrastive analyses across modalities (see Ferrara, 2020; Lepeut, 2020; Lepeut & Shaw, 2022; and Gabarró-López, 2020 for an application of the functional protocol). In cases where more than one primary interactive function appeared equally salient, we allowed for the assignment of up to two functions. The interactive functions of PU are described in Table 1 (see Appendix A for the complete annotation guide).

Table 1.

Overview of the interactive functions assigned to PU in this study (adapted from Bavelas et al., 1995, p. 397).

The primary interactive functions we identified within each discursive context included turn-regulating, monitoring, delivery, common ground, and planning functions (see Appendix A for complete list of paraphrases used when identifying each function). Turn-regulating PU forms, unsurprisingly, occurred at turn transition boundaries and had to give, take, or yield (either by declining a turn allocation or by backchanneling) a turn at talk. Monitoring PU forms typically occurred at boundaries in intonation units when signers or speakers were clearly not finished with an extended turn of talk but used the PU to briefly check for understanding. Delivery of new information via PU was determined when the topic of talk had not been raised prior to that instance and there were no co-occurring signals (e.g., signs or spoken utterances) that indicated shared knowledge between interactants. According to Bavelas et al. (1995, p. 395), general delivery gestures can be paraphrased by “here is my point”, where the information delivered to the addressee is metaphorically handed over in relation to the main topic at hand. The common ground function was identified by applying Clark’s (1996) domains of common ground (also employed by Holler & Bavelas, 2017). Communal common ground is considered to be knowledge shared in cultural or sub-cultural communities (Clark, 1996). Personal common ground is the knowledge shared between interlocutors either prior to the conversation or during it (Clark, 1996). Incremental common ground accrues during the interaction between interlocutors (Clark, 1996). The final interactive function, Planning, was determined when the current signer or speaker briefly paused their turn to consider how to phrase their next utterance. These PUs typically co-occurred with a break in eye contact which signaled the current signer or speaker was planning their next thought.

To identify each interactive function, we had to consider the context in which each move occurred. This required taking a closer look at sequences of utterances leading up to and then following each PU to determine how the form operated at the local level of the interaction. Additionally, to determine whether new information was being delivered, we tracked the trajectory of topics across the entire conversation to monitor the unfolding information state. To mitigate researcher subjectivity during the coding process, we employed a two-step approach to the identification and assignment of PU form and function separately. First, each PU instance was coded independently by the authors: Lepeut annotated PU in BF and LSFB with the assistance of a deaf annotator for LSFB and a research assistant for BF, while Shaw coded PU instances in ASL and AmEng datasets, supported by a research assistant (a certified ASL/English interpreter) for both datasets. Following the initial coding, functional annotations were applied to each PU as described in Section 2. To ensure consistency across the datasets, all instances of PU were then reviewed collectively by both authors, with up to three rounds of revisions with unclear cases discussed and resolved collectively. Ultimately, the ELAN export function was used to extract all the data, and subsequent analyses were conducted in Excel, with further statistical processing performed in R version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2024). GenAI was used to generate some of the coding in R to find solutions in cases of repeated errors in R.

The next section reports the results for the frequency and distribution of PU in the four languages under study. All instances of PU are first reported quantitatively, before turning attention to the specific interactive functions. This section will be accompanied by an in-depth examination of PU’s interactional functions in context, providing specific instances of its key interactive roles in signed and spoken interaction.

3. Results

3.1. General Overview of PU in the Four Languages

A total of 1316 PU tokens were found, out of which 293 tokens were produced by LSFB signers (5.3 PU tokens/minute, 22%) and 415 by BF speakers (6.4 PU tokens/minute, 32%). The ASL and AmEng datasets yielded 313 (5 PU tokens/minute, 24%) and 295 (4 PU tokens/minute, 22%) instances of PU, respectively. In this general overview, and despite the slightly higher frequency of PU tokens found in BF, the distribution of PU does not indicate a strong difference in its production across the four datasets. In other words, the overall frequency of PU across hearing speakers and deaf signers from the four language ecologies seems to be similar.

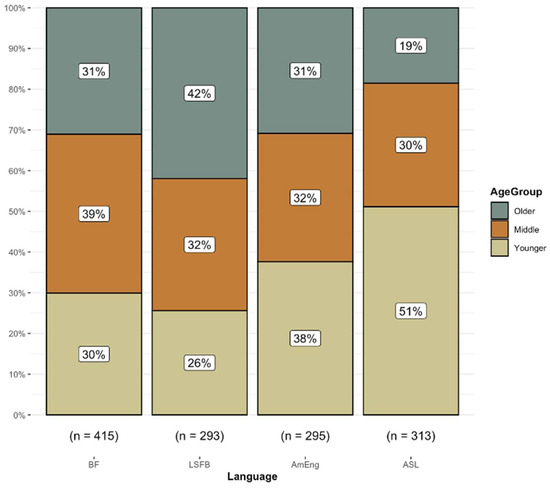

Since no vital differences were found in the distribution of PU across the four languages, we broke down the number of PU per age group following previous research that highlighted its potential age-sensitive nature. In particular, the work of McKee and Wallingford (2011) in New Zealand Sign Language and van Loon (2012) in Dutch Sign Language showed that older signers tended to produce more PU than younger signers while previous work by Gabarró-López (2020) in Catalan Sign Language and LSFB did not establish such a difference. We decided to explore the potential age-stratified usage of PU in the discourse of ASL and AmEng participants in comparison with LSFB and BF participants and asked the following question: Does a particular age group in the current data sample produce more PU than others? We found distinct patterns among some age groups. Figure 2 provides an overview of PU and its percentage in all four datasets according to three different age groups (Younger cohort, 26–45 years old; Middle-aged cohort 46–65 years old; Older cohort, 66–83 years old).

Figure 2.

Distribution of PU across the four languages/age group (description: The percentage of PU in each age group is shown within the bars, along with the total sample size of PU for each language at the bottom).

Here, we see the distribution of PU is markedly higher among younger ASL signers (51%) as compared to younger cohorts in the other language groups: 26% in LSFB, 30% in BF and 38% in AmEng. In contrast, the percentage of PU among the older cohorts is largest in LSFB signers (42%) and smallest in ASL signers (19%). More research into these age-related aspects is needed to confirm these results as well as to point to potential factors behind the difference. The Middle-aged group maintains relatively similar distributions across all four languages, varying between 30% and 39%. Comparing between the two spoken languages, BF and AmEng, the distributions of PU are relatively similar, indicating a relatively stable usage pattern for these age groups.

The descriptive results provided here highlight that the frequency with which deaf signers and hearing speakers produce PU is relatively similar, however there appears to be a particular preference by younger ASL and older LSFB signers to articulate more PUs in their discourse. In the next section, we take a closer look at the specific interactive functions of PU in signing and speaking contexts.

3.2. The Interactive World of PU Across Language Ecologies

We now turn to the analysis of the different interactive functions exhibited by the PU across the language ecologies. Delineating five different types of interactive functions allowed us to observe granular differences across the four language ecologies that were not evident when only looking at PU instances as a whole. The aim of this section is to observe whether there is functional overlap and/or a different use in the interactive roles of PU between LSFB and BF interactants, on the one hand, and how these results compare to what ASL and AmEng interactants do with PU to manage their conversation, on the other hand. To investigate this, we explored the effect of different predictors (namely, language and age group) that might contribute to the use of PU interactively (namely, the five different interactive functions) by using a Conditional Inference Tree (CIT) analysis with partykit (Hothorn & Zeileis, 2015) and plotted with ggparty (Borkovec & Madin, 2025). CITs have the advantage of revealing the effect of different predictors while also being appropriate for moderate and smaller datasets in linguistics (Levshina, 2021). CITs use p-values to determine splits in the data and predictors are only included in the CIT if they are significant (p ≤ 0.05).

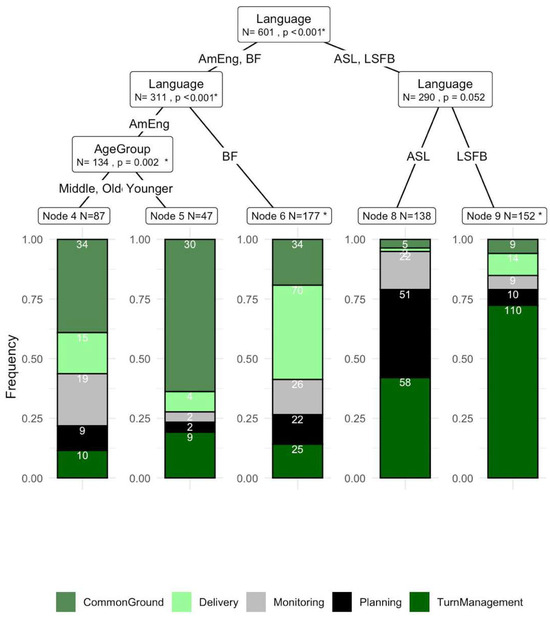

The CIT in Figure 3 shows that modality appears to be a significant predictor (p < 0.001) in determining the interactive roles of PU. Distinct patterns regarding the interactive roles of PU were observed among AmEng, BF, ASL, and LSFB participants, pointing to a distinctively sensitive use of PU between hearing and deaf individuals when it comes to managing the flow of interaction (i.e., turn management) and the interpersonal relationship between interlocutors (i.e., common ground). After the data were split into these two subsets (speaking and signing contexts), there is a further split by age-group for AmEng speakers. Younger AmEng speakers in our data produce more PU tokens when conveying shared knowledge (i.e., common ground) than the other two age groups.

Figure 3.

CIT of PU interactive functions between languages (description: The tree displays the major interactive functions (i.e., Common Ground, Delivery of New Information, Monitoring, Planning, and Turn Management) that were observed. Using a CIT, we were able to parse demographic factors that impact frequency of interactive functions). * Indicates significant results when the p-value is less than or equal to 0.05.

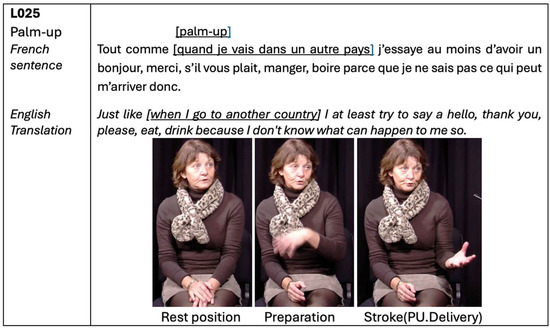

Turning attention to the content of the bar plot, each terminal node displays the frequency values (ranging from 0.00% to 1.00%) indicating the number of observations within each node that exhibits a particular function of PU. As we can see, for the SpL datasets, the delivery of new and shared information (i.e., common ground) through PU is higher for both BF and AmEng than for the SL datasets. This finding regarding the delivery of information is illustrated and discussed in the following example (Figure 4). The delivery function points to some topical element of the utterance being handed over metaphorically from speaker to addressee. In the following example in BF, the speaker L025 verbally introduces new information while rotating her left hand to supination. The context is the following: We are at the beginning of the task where speakers are asked to have an open discussion regarding the Flemish/Walloon linguistic situation in Belgium. Here, both participants decide to talk about learning Flemish and how important it is to have at least some notions of it in a country where the language is spoken. At the underlined words below, L025 flipped her left hand up, with the fingers slightly curved towards her addressee and presents this new information to L026.

Figure 4.

Example of a delivery PU in Belgian French (FRAPé Corpus, L025–L026, T04, 00:48.667–01:14.458).

In this example, the primary speaker directs the PU to the other participant, delivering the new content of the example she is proposing. Until this moment, the interlocutors are discussing the cultural differences between Flemish and Walloon-speaking regions of Belgium. When L025 compares the benefit of learning some Flemish to going to another country, she introduces this by delivering the accompanying message metaphorically to her addressee with PU. Following Bavelas et al.’s (1995) initial classification, this kind of interactional move from the speaker to the addressee can be paraphrased as “Here is my point” (p. 395). The palm of her left hand faces upward and is directed toward the addressee, which is consistent with Chu et al.’s (2014) “conduit gestures” or McNeill’s (1992) “conduit metaphor gestures”. Kendon (2004) and Müller (2004) have also recognized the use of the PU when delivering new information to make a point.

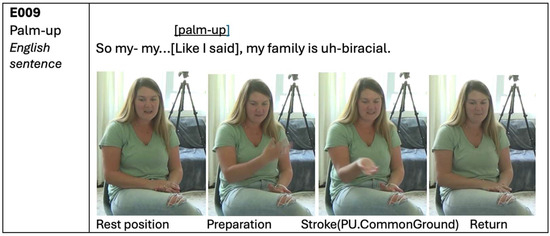

Besides delivering new information, the second most used functional category of PU among hearing speakers was to mark common ground. This category is a kind of delivery gesture that marks shared information that “the speaker assumes their addressee knows, believes or is able to infer” (Wilkin & Holler, 2011, p. 295). In the following example from the AmEng dataset (Figure 5), two friends are talking about where they grew up.

Figure 5.

Example of a common ground PU from the American English dataset (09:41.119–09:09:43.717).

The speaker begins to explain an experience she had interacting with different cultural groups during childhood. But before she launches into the story, she refers to prior knowledge that has been shared with her interlocutor. She begins with “So my- my” but quickly interrupts herself to signal that the addressee already knows her family is biracial: “Like I said, my family is biracial”. As she utters “Like I said” she fully expresses a PU in the direction of her addressee. Common ground, then, is referenced both verbally in her speech and manually via the PU. The addressee acknowledges the shared information with a quick nod and the speaker continues to relay the narrative.

While the same range of interactive functions are shared by signers and speakers, that is, both hearing and deaf groups used the PU to signal each of the interactive functions, these functions were not used at the same rate. In these datasets, hearing speakers across distinct geographical ecologies turn to the PU most frequently when relaying new information or marking common ground. By contrast, the SL datasets reveal a different picture. Deaf signers display a higher proportion of PU instances that are produced for the hierarchical organization of conversation, i.e., the turn-taking system and its related mechanisms such as feedback and planning for upcoming discourse while maintaining one’s turn. The instances from LSFB and ASL below illustrate this more prevalent use of PU in our signed datasets.

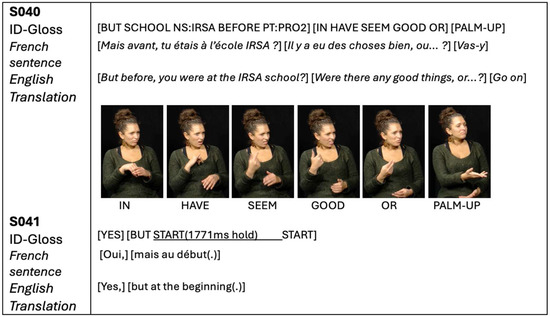

The following example in LSFB (Figure 6) takes place during a conversation on cultural deaf experiences. The signer (S040) poses a question to her addressee (S041) about whether he was at a school for the deaf in Belgium known as IRSA, ending the utterance with a finger pointing action (PT:PRO2). But as the addressee raised his hands from rest position to answer the question and take the floor, the signer continues signing a follow-up question: whether there were any good things about the IRSA school. The moment she sees her addressee has started his turn, she articulates a one-handed PU with her right hand to give the floor back to him.

Figure 6.

Example of a turn-giving PU in LSFB (LSFB Corpus, S040–S041, T03, 03:25.203–03:30.212).

The signer, in this example, suspends her utterance and extends the PU toward her interlocutor, visibly handing over the turn. Thus, besides PU’s functions as both an agreeing and a monitoring device, it is also used to regulate the turn-taking system: to open, give, or end one’s turn. In the example, PU acts as a turn offering device, referred to by Goodwin (1986) as a “turn-yielding signal” and according to Bavelas et al.’s (1995) classification as turn-giving where the PU hands over the speakership role to the addressee (as if saying, “go ahead, it’s your turn”).

This finding echoes previous results regarding the interactional dimension of the relevance of addressing specific strategies in the regulation of the turn-taking system in SL (Groeber & Pochon-Berger, 2014). In Figure 5, the PU is a clear invitation for the addressee to take over the floor (cf. WELL in Baker, 1977, also Groeber & Pochon-Berger, 2014). It also serves as a key illustration of “the current speaker’s meticulous on-line analysis of the coparticipant’s conduct” (Groeber & Pochon-Berger, 2014, p. 9); the signer overlapped her signing as her addressee had begun to answer the initial question about IRSA, quickly noticed the overlap, and used the PU to accede his claim to the floor.

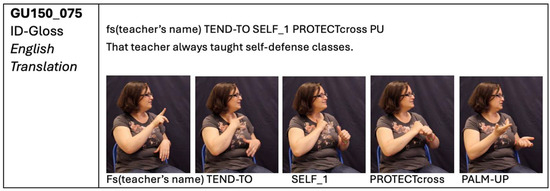

Next, we turn to an example of a monitoring PU in ASL (Figure 7) where the signer briefly pauses mid-sign stream to monitor her addressee’s uptake of what was just said.

Figure 7.

Example of a monitoring PU in ASL (GU150_070, 00:11:26.500–00:11:28.500).

Just before this utterance, the signer was asked to talk about her favorite classes and professors when she was in college at Gallaudet. After thinking for a moment, the signer settles on the Physical Education courses and professors she liked best, checking if the interviewer is familiar with each name. Here, in this example, she spells the professor’s name then gives the course topic that was taught. She ends the phrase with a PU which she holds for 0.3 ms while monitoring for a response of recognition of that particular professor. The interviewer nods, indicating familiarity, at which point the signer continues her turn. The PU, when held for a moment, coupled with eye contact with the addressee, signals that the signer seeks some kind of visual feedback that her discourse is making sense. Additionally, the form also signals that the floor is not yet relinquished to the addressee.

To summarize, the use of PU for interactional purposes varies across languages and modality. SpL contexts exhibited a marked preference to convey information (both new and shared) with the PU whereas SL contexts exhibited preferences for PU interactively to manage turn boundaries. In the same geographical context, only younger Americans (deaf and hearing alike) use PU more than other cohorts but beyond that, there were no salient patterns between Belgian and American groups indicating practices endemic to a local ecology.

4. Discussion

This study set out to investigate whether and how a shared manual form, palm-up (PU), fulfills comparable interactive functions—initially established by Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995)—across four distinct language groups. By directly comparing face-to-face conversations in LSFB, Belgian French, ASL, and AmEng, we examined the distribution and particular interactive roles that PU serves in signed and spoken conversations.

Our findings align with prior results on the use of PU in other signing and speaking contexts, exhibiting differences and similarities within and across languages, contexts, and individuals. All participants used PU across the same set of functions, but to different degrees depending on whether they were signing or speaking. In terms of similarities, our analysis revealed no significant differences in the number of PU produced across languages. All interactants, hearing and deaf, Belgian and American, used PU frequently—from 4 to 6 times per minute—in their discourses. However, when zooming into the specific interactional functions, the modality of expression (spoken or signed) seems to play a role in how speakers and signers engage in conversation through PU. Speakers in Belgium and the U.S. most frequently turn to the PU when navigating the shifting information state—to mark shared and new information. Signers across both geographical contexts exhibit a strong preference for managing the participation framework—taking turns and holding the floor—via the PU. The question to be explored next is why we see different distributions in interactive functions according to modality?

The fact that PU is more of a productive resource for turn management in signed conversations (i.e., for regulating the structure of the conversation—especially managing turn-taking and providing feedback), and less so in spoken contexts, may reflect the different affordances available to signers and speakers. Such a distinction could be shaped by the presence of the vocal channel in spoken interaction and the constraints of the manual channel in signed interaction. For example, the fact that the PU turn-taking function is less often recruited by hearing interactants might indicate that there are more productive resources speakers turn to when managing turns-at-talk (e.g., the addition of vocal intonation and in-breath or eye gaze shifts to signal turn boundaries). For signers, holding a supinated palm in space is an efficient way to maintain their addressee’s attention, check on comprehension, and indicate a desire to hold or transfer the floor; the PU serves as a quick visual pause in a rapidly unfolding sign stream. The fact that PU is a more productive resource to mark information sharing in spoken conversations points to the multimodality of SpL which allows speech and manual gestures to co-articulate simultaneously. Conversely, signers need to sequence these communicative moves or use one hand to express commentary (foregrounded track) while the other conveys metacommentary (backgrounded track). The shared use of the manual channel for expressing lexical content, then, could be a constraint for the specific interactive use of delivery PU in SLs.

Additionally, the role of PU in this set of functions for managing ongoing dialogue and the interpersonal relationship with fellow interactants align with broader principles underlying the building blocks of social interaction. One of the aims that participants pursue in conversation is to establish mutual understanding for a successful conversation and ensure that this is maintained throughout the exchange. This requires collaborative efforts between signer/speaker and their addressees (e.g., continuous checks and repairs, Dingemanse et al., 2015). We discussed that managing both primary and secondary tracks of communication involves intense effort and attention (Clark, 1996). As such, each person tends to follow a principle referred to as the least collaborative effort in conversation. That is, people tend to be effective in conversation while minimizing costs like avoiding gaps and overlaps, and providing highly effective means for repairing problems of understanding. Here, a similar point can be made about PU and its roles in the ongoing dialogue. PU serving interactive functions, as Bavelas (2022) highlights,

solves a particular problem for speakers, which is to include their addressee in the dialogue and let him or her know where things stand—without having to stop and do this verbally. If a speaker kept checking in verbally (e.g., “Here’s something new to you,” “As you just said,” “This is important,” “You fill in the rest,” “Are you following me?”), it would constantly interrupt the flow of topical information.(p. 117)

We argue that the functions of PU in managing turns, providing feedback, monitoring addressees as well as delivering information are used by deaf and hearing interactants because the form is an effective means to an end; it minimizes interaction costs and avoids potential disruptions. Our results indicate that speakers and signers frequently turn to the PU to solve different, modality-specific interactive problems.

This study on PU and its interactive functions alone complements prior work done on other types of manual and non-manual actions and their interactive functions, especially in SL discourse. PU is not the only ubiquitous manual strategy that speakers and signers articulate to regulate their talk-in-progress. A good case in point is to relate PU and pointing actions, which have been shown to express similar interactional meanings in SpL (e.g., Jokinen, 2010; Mondada, 2007) and SL use (e.g., in Norwegian Sign Language, Ferrara, 2020; LSFB and BF, Lepeut, 2020; LSFB, ASL, AmEng, and BF, Lepeut & Shaw, 2022). For example, Jokinen (2010) illustrated how index pointing actions also indicate common ground, acknowledgement, elicit shared understanding, and present new information to addressees. This raises an important question: what prompts interactants to select one form over another? Why do they choose PU over a pointing action to express interactive functions in conversation such as shared knowledge versus delivery of general information? Future studies should consider hand configuration of such actions. PU has been documented in various forms from the fully expressed, two-handed supinated one to the reduced flip of the hand(s) (Cienki, 2021). While some have even proposed that minute movements like the thumb lift are related, at least pragmatically, to the two-handed form. Interestingly, the palm supinated base form of the PU investigated in this paper has shed light on another variant, the “Gun Handshape Palm Up” (Shaw, 2019) characterized by an extended thumb and index finger supinated resembling a hybrid of PU and point, which seems to serve a complementary, function to PU in discourse: introduction of new topics occurred with a fully open PU whereas the Gun Handshape Palm Up occurred when participants indicated salient information, which had already been given. Further research should be conducted on the dialogue activity of such actions, especially in SLs and from a systematic perspective comparing the different configurations of PU variants. This kind of work will not only shed light on the versatility of manual actions but also highlight the dynamic ways in which they are transformed to fit online interactional contingencies and communicative needs.

From a theoretical perspective, the current results have important implications for the ongoing gesture-sign discussion. Rather than emphasizing the discrepancies between co-speech gesture and sign, our study advocates for a semiotic, modality agnostic view that treats language as situated, embodied, and interactionally organized. Rather than seeing PU as a relic of a historical gestural past, we see it as a form that deaf and hearing people conventionally employ to solve local, interactive problems. The flexible, multifunctional use of PU across different samples of languages offers support for this view, suggesting that interactional forms like PU are integral to language rather than peripheral to it, and should therefore fit into theories of language inclusive of SLs. By examining the forms side by side, we were able to identify differences and uncover similarities across modalities that might help narrow the focus for theoretical and applied work (e.g., SL interpreters might benefit from knowing pragmatically distinct preferences among hearing and deaf interactants). Methodologically, our study also makes an important contribution by showing the feasibility and benefits of a direct cross-modal and cross-linguistic comparison grounded in face-to-face conversational data.

Finally, our current findings challenge traditional linguistic typologies that foreground referential content while sidelining interactional ones. These data add to a growing body of work that calls for typologies which integrate interactional functions as core components of language (see Lopez-Ozieblo, 2020). Additionally, as Bavelas (2022, p. 117) underlines, “we are describing a function (…) not categorizing or classifying it. Categories are static and isolated from a dialogue.” It is thus essential to emphasize that these interactional meanings describe a function of the PU in a particular sequential environment between interactants. PU in its interactive functions therefore come to complement other instances of PU in its epistemic and modal functions of use (Cooperrider et al., 2018). The interactive aspect of PU comes to the fore when the data under scrutiny are from spontaneous, conversational contexts, which have been sidelined, particularly in SL linguistics. As Ferrara (2020, p. 18) notes, the high presence of various interactional meanings conveyed through bodily practices in interaction such as PU “underscores the importance of studying a wide range of text types. It also calls for caution in drawing generalizations about {signed} language use from limited genres such as narrative retellings.” Although the relationship between SpL and SL remains complex, the increasing availability of multimodal corpora now enables more grounded, data-driven comparisons than the field has seen before. At this stage in the development of both SpL and SL linguistics, such efforts are crucial for building a more integrated and comprehensive account of how language works across modalities.

Our analysis is not without limitations. Due to the labor-intensive nature of annotation, this study focused only on the manual articulation of PU, leaving aside the important role of non-manual features, for example. Prior work (e.g., Debras & Cienki, 2012) has shown that manual actions like PU are often accompanied by shrugs, eyebrow movements, or facial expressions, which contribute to and are integral part of the composite nature of the message. Future research should examine these multichanneled ensembles more closely in speaking and signing conversational contexts to determine how combinations of manual and non-manual features correlate with particular interactive functions and whether such combinations differ between language ecologies.

Looking ahead, several directions emerge for future work. One pressing need is to extend this kind of research beyond Western contexts to include more diverse languages and communities. Our current corpora are limited both in geographic scope and in terms of generational diversity—many of our so-called “young” signers are now middle-aged, for example. Further studies might also explore the development of PU use across the lifespan and in different communicative environments. In addition, greater methodological convergence between gesture and sign researchers will help build shared frameworks for comparative analysis, allowing more nuanced insights into the semiotic and interactional infrastructure of human communication.

Finally, our findings highlight the value of studying form-function relationships in detail. Even when a manual form like PU is broadly shared, the ways it is mobilized within interactions differ meaningfully depending on the interactional context and the communicative goals of the participants engaged in the ongoing exchange. This functional flexibility reinforces the idea that interactional aspects of language use are not add-ons but central to how language is practiced and experienced. We encourage researchers studying PU in SpL to consider these findings from SL contexts, not as exceptions but as data that enrich and expand our understanding of language-in-interaction.

5. Conclusions

In this paper we provided a systematic, corpus-based comparison of one single element—palm-up—as used in the discourse of signing and hearing individuals from four distinct language ecologies, focusing on its interactive roles. In this way, our current study offers novel theoretical and methodological insights and reveals how PU highlights many different sides of interaction management. While all deaf and hearing interactants across all languages share a set of common uses of PU (in terms of interactive functions), our results point in the direction of certain specific patterns of use of PU in signed and spoken conversations. Based on these results, it appears that deaf signers orient more systematically to PU for turn-taking management purposes (e.g., opening, giving, closing one’s turn), including the expression of feedback. By contrast, hearing speakers tended to turn to PU for interactive functions that delivered the message and marked it as new or shared between interlocutors. This main distinction can be framed in relation to different contingencies of signed versus spoken conversation. The interactional work conducted by signers to manage turn-taking through PU can be achieved sequentially, without competing with the signing flow whereas speakers can rely on a different set of articulators, namely their vocal tract to deliver the new message while accompanying this information via PU. Such results warrant further work.

Although the palm-up has been widely studied around the globe, we believe it is safe to say that it will keep fascinating many for the foreseeable future, leaving room for exploring more systematic cross-modal and cross-linguistic analysis of different spoken and signed languages in the hope of finding out more about our deeply social and inherently human ability for interacting. Such an approach paves the way to new possibilities for understanding the various ways in which language activity is embodied according to the channels, articulators, and senses that are available to the interactants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L. and E.S.; methodology, A.L. and E.S.; software, A.L.; validation, A.L. and E.S.; formal analysis, A.L. and E.S.; data curation, A.L. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, A.L. and E.S.; visualization, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Gallaudet University (Approval Code: PJID #2827; Approval Date: 8 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The LSFB data presented in this study are openly available in https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/ (LSFB Corpus). The ASL data presented in this study are openly available in https://media.gallaudet.edu/channel/DSC+-+Deaf+Stories+Corpus/121808791 (accessed on 3 September 2024). The Belgian, French and American English data are not currenty available. The complete annotation of Belgian French and American English data is currently in progress.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participants for their contributions to this study. Additionally, we wish to thank the research assistants (Hadrien Cousin and Sarah Biello) for their support of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SpL | Spoken Language |

| SL | Signed Language |

| ASL | American Sign Language |

| LSFB | Belgian French Sign Language |

| AmEng | American English |

| BF | Belgian French |

| PU | Palm-up |

| VGT | Flemish Sign Language |

Appendix A

| Interactive Function | Definition | Paraphrases | References | |

| Interactive Functions | Backchannelling [AGR] | It expresses understanding or indicates approval of what has previously been said. It is used to show agreement/following (the role of feedback in interaction). | ‘I agree’, ‘indeed’, ‘okay’, ‘I understand’; “yeah” | Ferrara (2020) |

| Common Ground [COGR] | It expresses the participant’s understanding that the information being conveyed is shared by the addressee. It includes Bavelas’ “shared information” gestures, which mark information that the addressee probably already knows. It also includes “general citing” gestures revealing that the point the speaker is now making had been contributed earlier by the addressee. Pointing actions serving this function can also be used “by an addressee “to respond to another signer ‘right, as was just mentioned (earlier)’” (Ferrara, 2020, p. 8). | “as you know” or “as you/I said earlier” | Holler and Bavelas (2017) | |

| Delivery [DELIV] | It consists of the presentation of a topic as new or salient to the addressee. For instance, the palm presentation PU with the giving/offering function of an idea, a concept, … | “Here’s my point” | Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995), Kendon (2004), Müller (2004) | |

| Digression [DIG] | It marks information that should be treated by the addressee as an aside from the main point, as part of a parenthesis. | “by the way”, “back to the main point” | Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995) | |

| Elliptical [ELL] | It marks information that the addressee should imagine for himself/herself; the speaker will not provide further details. | “And things like that”, “or whatever” | Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995) | |

| Monitoring [MONI] | It expresses cooperation or checks the addressee’s reaction for understanding and attention by an explicit address. It includes Bavelas’: (1) “acknowledgement” of the addressee’s response (viz., the speaker saw or heard that the addressee understood what had been said; (2) “seeking agreement” asks whether the addressee agrees/disagrees with the point made; and (3) “seeking following” asks whether the addressee understands what is said. | “I see that you understood me”, “do you agree?”, “you know?”, “eh?” | Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995) | |

| Planning [PLAN] | It indicates that the participant is making a cognitive effort in editing a term or in the processing of speech (e.g., hesitation, word searching, and pause fillers). Planning can be interactively designed as the participant can request help from the addressee during word search activities (corresponding to seeking help gestures, Bavelas et al., 1992, 1995) | “euh” | Goodwin (1986) | |

| Turn Opening [TURN-OPEN] | The item opens a new turn, in which case it indicates floor-taking, or a new sequence within the same topic, namely an introduction to an enumeration or a narrative sequence. | “Well, …”, “So, …”, “First, … | Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995) | |

| Turn Giving [TURN-GIVE] | Turn yielding includes Bavelas’ “giving turn” and “leaving turn open”. It is used to hand over the turn. | “your turn” | Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995) | |

| Turn Closing [TURN-CLOSE] | It indicates the intention to close a list, a thematic unit, or a turn. It must be in final or autonomous position. | “This topic is now closed” | Bavelas et al. (1992, 1995) |

References

- Baker, C. (1977). Regulators and turn-taking in American Sign Language discourse. In L. A. Friedman (Ed.), On the other hand (pp. 215–236). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bavelas, J. B. (2022). Face-to-face dialogue: Theory, research, and applications. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bavelas, J. B., Chovil, N., Coates, L., & Roe, L. (1995). Gestures specialized for dialogue. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavelas, J. B., Chovil, N., Lawrie, D., & Wade, A. (1992). Interactive gestures. Discourse Processes, 15, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavelas, J. B., Gerwing, J., Sutton, C., & Prevost, D. (2008). Gesturing on the telephone: Independent effects of dialogue and visibility. Journal of Memory and Language, 58, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukeleers, I., & Lepeut, A. (2022). Who’s got the upper hand? A cross-linguistic study on overlap in VGT and LSFB. In A. Lepeut, & I. Beukeleers (Eds.), On the semiotic diversity of language: The case of signed languages (pp. 212–246). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bolly, C. T., & Crible, L. (2015, July 26–31). From context to functions and back again: Disambiguating pragmatic uses of discourse markers [Conference paper]. 14th International Pragmatics Conference (IPra): Anchoring Utterances in Co(n)text, Argumentation, Common Ground, Antwerp, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec, M., & Madin, N. (2025). ggparty: ‘ggplot’ visualizations for the ‘partykit’ package_. R package version 1.0.0.1. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggparty (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Chu, M., Meyer, A., Foulkes, L., & Kita, S. (2014). Individual differences in frequency and saliency of speech-accompanying gestures: The role of cognitive abilities and empathy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(2), 694–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cienki, A. (2021). From the finger lift to the palm-up open hand when presenting a point: A methodological exploration of forms and functions. Languages and Modalities, 1, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienki, A. (2023). Channels, modalities, and semiotic modes and systems: Multi- and poly. In T. I. Davidjuk, I. I. Isaev, J. V. Mazurova, S. G. Tatevosov, & O. V. Fedorova (Eds.), Язык кaк oн ecть: Cбopник cтaтeй к 60-лeтию Aндpeя Aлeкcaндpoвичa Kибpикa (pp. 288–292). Buki Vedi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J., & Sutton-Spence, R. (2001). Turn-taking patterns in deaf conversation. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 5, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperrider, K., Abner, N., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2018). The palm-up puzzle: Meanings and origins of a widespread form in gesture and sign. Frontiers in Communication, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaf Stories Collection. (2017). Home [Kaltura channel]. Available online: https://media.gallaudet.edu/channel/DSC+-+Deaf+Stories+Corpus/121808791 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Debras, C., & Cienki, A. (2012, September 3–5). Some uses of head tilts and shoulder shrugs during human interaction, and their relation to stancetaking [Conference paper]. 2012 International Conference on Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and 2012 International Conference on Social Computing, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, C., Torreira, F., & Levinson, S. C. (2015). Turn-timing in signed conversations: Coordinating stroke-to-stroke boundaries. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingemanse, M., Roberts, S. G., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., Drew, P., Floyd, S., Gisladottir, R. S., Kendrick, K. H., Levinson, S. C., Manrique, E., Rossi, G., & Enfield, N. J. (2015). Universal principles in the repair of communication problems. PLoS ONE, 10(9), e0136100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dively, V. L. (1998). Conversational repairs in ASL. In C. Lucas (Ed.), Pinky extension and eye gaze: Language use in deaf communities (pp. 137–169). Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. Semiotica, 1(1), 49–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmorey, K. (1999). Do signers gesture? In L. Messing, & R. Campbell (Eds.), Gesture, speech, and sign (pp. 133–159). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fenlon, J., & Hochgesang, J. A. (2022). Signed language corpora. Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, L. (2020). Some interactional functions of finger pointing in signed language conversations. Glossa: Journal of General Linguistics, 5(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarró-López, S. (2020). Are discourse markers related to age and educational background? A comparative account between two sign languages. Journal of Pragmatics, 156, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarró-López, S., & Meurant, L. (2022). Contrasting signed and spoken languages: Towards a renewed perspective on language. Languages in Contrast, 22(2), 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard-Groeber, S. (2015). The management of turn transition in signed interaction through the lens of overlaps. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C. (1986). Gestures as a resource for the organization of mutual orientation. Semiotica, 62(1–2), 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeber, S., & Pochon-Berger, E. (2014). Turns and turn-taking in sign language interaction: A study of turn-final holds. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 121–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, J. B. (2015). Hey! Topics in Cognitive Science, 7(1), 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochgesang, J. A. (2020). Collections of ASL for research and documentation (CARD). Figshare. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochgesang, J. A., Crasborn, O., & Lillo-Martin, D. (2025). ASL signbank. Available online: https://aslsignbank.com (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Hodge, G., Sekine, K., Schembri, A., & Johnston, T. (2019). Comparing signers and speakers: Building a directly comparable corpus of Auslan and Australian English. Corpora, 14, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holler, J., & Bavelas, J. (2017). Multi-modal communication of common ground: A review of social functions. In R. B. Church, M. W. Alibali, & S. D. Kelly (Eds.), Why gesture? How the hands function in speaking, thinking and communicating (pp. 213–240). Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T., & Zeileis, A. (2015). partykit: A modular toolkit for recursive partytioning in R. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 16, 3905–3909. Available online: https://jmlr.org/papers/v16/hothorn15a.html (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Hoza, J. (2011). The discourse and politeness functions of HEY and WELL in American Sign Language. In C. B. Roy (Ed.), Discourse in signed languages (pp. 69–95). Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, K. (2010, May 19–21). Non-verbal signals for turn-taking and feedback. Seventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’10), Valletta, Malta. [Google Scholar]

- Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible actions as utterances. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kendon, A. (2008). Some Reflections on the relationship between ‘gesture’ and ‘sign’. Gesture, 8, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, S., van Gijn, I., & van der Hulst, H. (1998). Movement phases in signs and co-speech gestures, and their transcription by human coders. In I. Wachsmuth, & M. Fröhlich (Eds.), Gesture and sign language in human-computer interaction (Vol. 1371). GW 1997. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, E. S., & Bellugi, U. (1979). The signs of language. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kusters, A. (2017). Gesture-based customer interactions: Deaf and hearing Mumbaikars’ multimodal and metrolingual practices. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(3), 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladewig, S. H. (2011). Putting the cyclic gesture on a cognitive basis. CogniTextes, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepeut, A. (2020). Framing language through gesture: Palm-up, index finger-extended gestures, and holds in spoken and signed interactions in French-speaking and signing Belgium [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Namur]. [Google Scholar]

- Lepeut, A., Lombart, C., Vandenitte, S., & Meurant, L. (2024). Spoken and signed languages hand in hand: Parallel and directly comparable corpora of French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) and French. Corpora, 19(2), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepeut, A., Lombart, C., Vandenitte, S., & Meurant, L. (2025). Make it a double: The building and use of the LSFB and FRAPé corpora to study and compare French Belgian Sign Language and Belgian French. In T. Leuschner, A. Vajnovszki, G. Delaby, & J. Barðdal (Eds.), How to do things with corpora. Linguistik in Empirie und Theorie/Empirical and Theoretical Linguistics. J.B. Metzler. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]