Abstract

This note presents a series of contrasts pertaining to Vietnamese polar questions: (i) The subject can be definite but not quantificational; (ii) the subject can be plain but not only-focused; (iii) the modal adverb chắc chắn (‘certainly’) can follow but not precede verum focus. I argue that a monoclausal analysis, advocated in several previous works, will have difficulties accounting for these contrasts and propose a bi-clausal analysis that explains them in a natural way. The explanation relies on the assumption of a general condition on questions, Partition by Exhaustification (PbE), in conjunction with some other independently motivated semantic and pragmatic constraints.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Syntactic Profile of Vietnamese Polar Questions

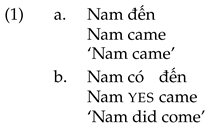

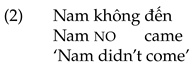

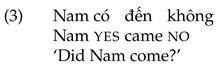

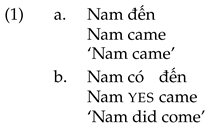

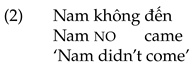

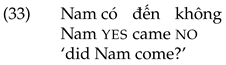

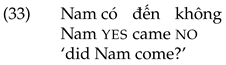

A polar question in Vietnamese appears as an affirmative sentence followed by the negation. An affirmative sentence is a declarative with (matrix) verum focus. In English, verum focus is expressed by inserting the light verb do in the auxiliary position: John came becomes John did come, for example. Vietnamese has a similar strategy, using the light verb có, whose lexical meaning is ‘have’ (Phan, 2024; Trinh, 2005). As có is also used as a positive response particle, i.e., as ‘yes,’ I will gloss it as yes.1 Negation in Vietnamese is expressed by the word không, which I will gloss as no, since it is also used as the negative response particle, i.e., as ‘no.’ It also occurs in the auxiliary position; hence, in complementary distribution with yes.2

Negation in Vietnamese is expressed by the word không, which I will gloss as no, since it is also used as the negative response particle, i.e., as ‘no.’ It also occurs in the auxiliary position; hence, in complementary distribution with yes.2 Here is how the polar question meaning ‘did Nam come?’ is expressed in Vietnamese.

Here is how the polar question meaning ‘did Nam come?’ is expressed in Vietnamese.

I will call the affirmative preceding no in a polar question the ‘prejacent’ of the question.

I will call the affirmative preceding no in a polar question the ‘prejacent’ of the question.

Negation in Vietnamese is expressed by the word không, which I will gloss as no, since it is also used as the negative response particle, i.e., as ‘no.’ It also occurs in the auxiliary position; hence, in complementary distribution with yes.2

Negation in Vietnamese is expressed by the word không, which I will gloss as no, since it is also used as the negative response particle, i.e., as ‘no.’ It also occurs in the auxiliary position; hence, in complementary distribution with yes.2 Here is how the polar question meaning ‘did Nam come?’ is expressed in Vietnamese.

Here is how the polar question meaning ‘did Nam come?’ is expressed in Vietnamese.

I will call the affirmative preceding no in a polar question the ‘prejacent’ of the question.

I will call the affirmative preceding no in a polar question the ‘prejacent’ of the question.1.2. Some Puzzles About Vietnamese Polar Questions

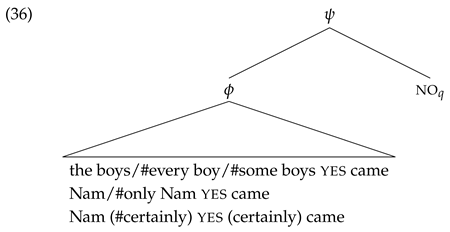

The puzzles about Vietnamese polar questions that this note aims to resolve are of the following form: Some affirmative sentences that are independently acceptable become deviant as prejacents of polar questions. Let me now discuss the specific cases one by one.3

1.2.1. Definite vs. Quantificational Subjects

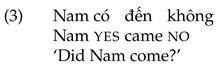

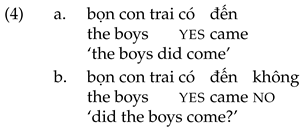

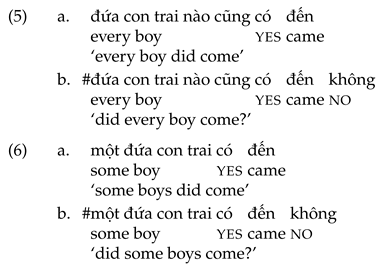

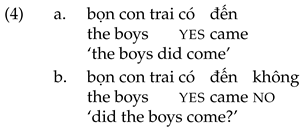

A natural expectation is that if an affirmative sentence is independently acceptable, the polar question không, expressing the meaning ‘whether ,’ should be acceptable as well. This expectation is met in (4), where the subject of the affirmative is a definite noun phrase: Both the affirmative (4a) and the polar question (4b) are acceptable.

However, such a pattern is disrupted when the subject is quantificational: Even though both (5a) and (6a) are acceptable affirmative sentences, the corresponding polar questions in (5b) and (6b), whose intended meanings are ‘whether every boy came’ and ‘whether some boys came,’ respectively, are both unacceptable.

However, such a pattern is disrupted when the subject is quantificational: Even though both (5a) and (6a) are acceptable affirmative sentences, the corresponding polar questions in (5b) and (6b), whose intended meanings are ‘whether every boy came’ and ‘whether some boys came,’ respectively, are both unacceptable.

However, such a pattern is disrupted when the subject is quantificational: Even though both (5a) and (6a) are acceptable affirmative sentences, the corresponding polar questions in (5b) and (6b), whose intended meanings are ‘whether every boy came’ and ‘whether some boys came,’ respectively, are both unacceptable.

However, such a pattern is disrupted when the subject is quantificational: Even though both (5a) and (6a) are acceptable affirmative sentences, the corresponding polar questions in (5b) and (6b), whose intended meanings are ‘whether every boy came’ and ‘whether some boys came,’ respectively, are both unacceptable.

1.2.2. Plain vs. Only-Focused Subjects

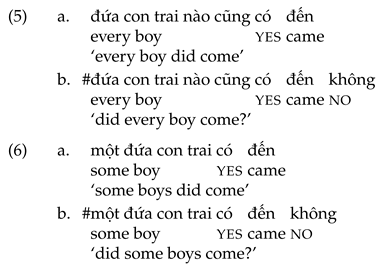

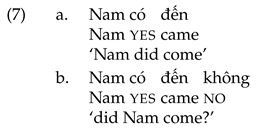

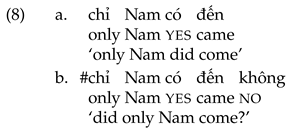

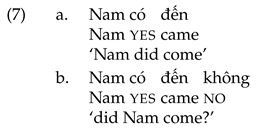

When the subject is a ‘plain’ noun phrase, e.g., Nam, things work as expected: The affirmative is acceptable in isolation and as the prejacent of a polar question. This is exemplified by (1b) and (3), reproduced below in (7a) and (7b), respectively.

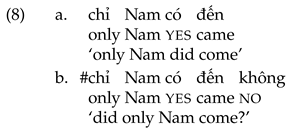

However, when the subject is focused by chỉ ‘only,’ the affirmative sentence is acceptable and means ‘only Nam did come,’ while the polar question, whose intended meaning is ‘whether only Nam came,’ is not.

However, when the subject is focused by chỉ ‘only,’ the affirmative sentence is acceptable and means ‘only Nam did come,’ while the polar question, whose intended meaning is ‘whether only Nam came,’ is not.

However, when the subject is focused by chỉ ‘only,’ the affirmative sentence is acceptable and means ‘only Nam did come,’ while the polar question, whose intended meaning is ‘whether only Nam came,’ is not.

However, when the subject is focused by chỉ ‘only,’ the affirmative sentence is acceptable and means ‘only Nam did come,’ while the polar question, whose intended meaning is ‘whether only Nam came,’ is not.

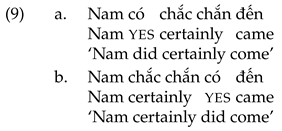

1.2.3. Adverb Following vs. Preceding yes

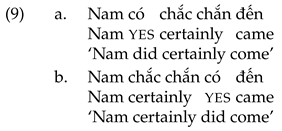

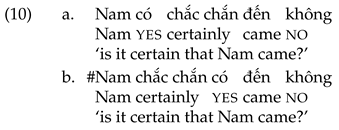

The sentential adverb chắc chắn ‘certainly’ in affirmative sentences can follow the verum focus có, as in (9a), or precede it, as in (9b), with no semantic consequence.4 The natural expectation, then, is that the two polar questions in (10) are both acceptable. The fact, however, is that only (10a) is acceptable.

The natural expectation, then, is that the two polar questions in (10) are both acceptable. The fact, however, is that only (10a) is acceptable.

The natural expectation, then, is that the two polar questions in (10) are both acceptable. The fact, however, is that only (10a) is acceptable.

The natural expectation, then, is that the two polar questions in (10) are both acceptable. The fact, however, is that only (10a) is acceptable.

1.3. The Explanation in Outline

My explanation of the puzzles above will relate the contrast in acceptability of sentences in Vietnamese to a contrast in availability of readings in English.

1.3.1. Some Facts About English Polar Questions

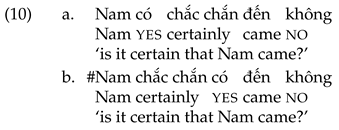

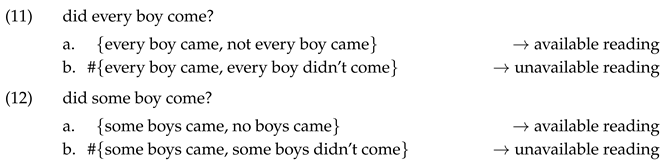

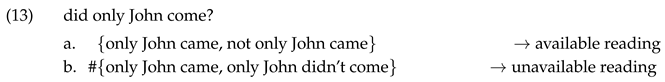

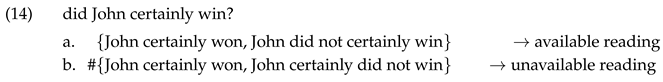

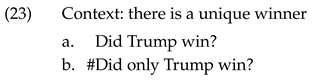

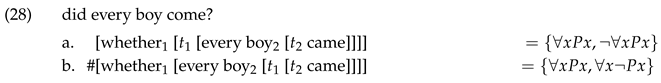

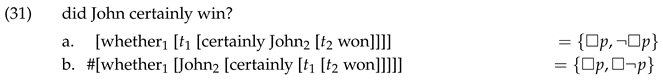

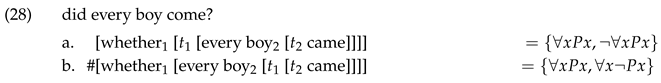

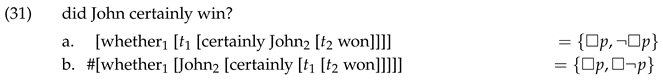

Let me be more specific. Consider the English polar questions in (11) and (12). Intuitively, (11) has to be read in such a way that its answer set is (11a), not (11b), and (12) has to be read in such a way that its answer set is (12a), not (12b).5 In other words, a ‘no’ answer to (11) has to mean ‘not every boy came’ () and cannot mean ‘every boy didn’t come’ (). Similarly, a ‘no’ answer to (12) has to mean ‘no boys came’ () and cannot mean ‘some boys didn’t come’ (). Next, consider (13).

In other words, a ‘no’ answer to (11) has to mean ‘not every boy came’ () and cannot mean ‘every boy didn’t come’ (). Similarly, a ‘no’ answer to (12) has to mean ‘no boys came’ () and cannot mean ‘some boys didn’t come’ (). Next, consider (13).

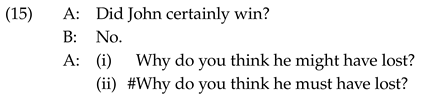

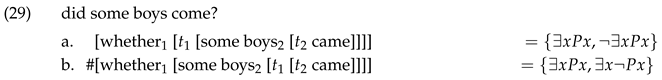

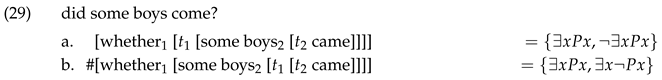

The question in (13) has to be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means ‘not only John came’ (), not ‘only John didn’t come’ (). Finally, consider (14).

The question in (13) has to be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means ‘not only John came’ (), not ‘only John didn’t come’ (). Finally, consider (14).

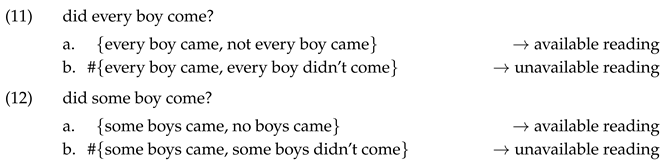

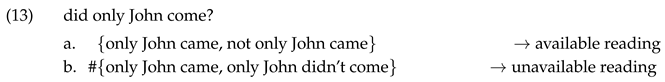

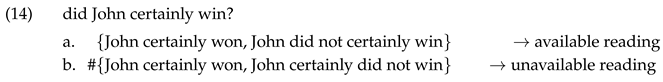

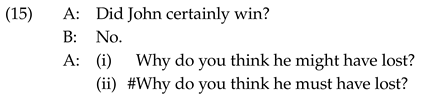

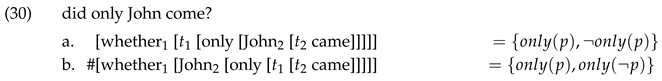

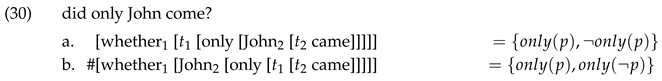

The question in (14) must be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means it is not certain that John won (), not ‘it is certain that John did not win,’ i.e., ‘it is certain that John lost’ (). Since this claim might not be as obvious as those regarding the missing readings of (11), (12), and (13), let me corroborate it with an example. Compare the two responses by A to B’s negative answer in (15).

The question in (14) must be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means it is not certain that John won (), not ‘it is certain that John did not win,’ i.e., ‘it is certain that John lost’ (). Since this claim might not be as obvious as those regarding the missing readings of (11), (12), and (13), let me corroborate it with an example. Compare the two responses by A to B’s negative answer in (15).

The contrast between (i) and (ii) shows that B’s answer is read as ‘John might have lost,’ i.e., ‘John did not certainly win’ (), not as ‘John must have lost,’ i.e., ‘John certainly did not win’ ().

The contrast between (i) and (ii) shows that B’s answer is read as ‘John might have lost,’ i.e., ‘John did not certainly win’ (), not as ‘John must have lost,’ i.e., ‘John certainly did not win’ ().

In other words, a ‘no’ answer to (11) has to mean ‘not every boy came’ () and cannot mean ‘every boy didn’t come’ (). Similarly, a ‘no’ answer to (12) has to mean ‘no boys came’ () and cannot mean ‘some boys didn’t come’ (). Next, consider (13).

In other words, a ‘no’ answer to (11) has to mean ‘not every boy came’ () and cannot mean ‘every boy didn’t come’ (). Similarly, a ‘no’ answer to (12) has to mean ‘no boys came’ () and cannot mean ‘some boys didn’t come’ (). Next, consider (13).

The question in (13) has to be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means ‘not only John came’ (), not ‘only John didn’t come’ (). Finally, consider (14).

The question in (13) has to be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means ‘not only John came’ (), not ‘only John didn’t come’ (). Finally, consider (14).

The question in (14) must be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means it is not certain that John won (), not ‘it is certain that John did not win,’ i.e., ‘it is certain that John lost’ (). Since this claim might not be as obvious as those regarding the missing readings of (11), (12), and (13), let me corroborate it with an example. Compare the two responses by A to B’s negative answer in (15).

The question in (14) must be read in such a way that its ‘no’ answer means it is not certain that John won (), not ‘it is certain that John did not win,’ i.e., ‘it is certain that John lost’ (). Since this claim might not be as obvious as those regarding the missing readings of (11), (12), and (13), let me corroborate it with an example. Compare the two responses by A to B’s negative answer in (15).

The contrast between (i) and (ii) shows that B’s answer is read as ‘John might have lost,’ i.e., ‘John did not certainly win’ (), not as ‘John must have lost,’ i.e., ‘John certainly did not win’ ().

The contrast between (i) and (ii) shows that B’s answer is read as ‘John might have lost,’ i.e., ‘John did not certainly win’ (), not as ‘John must have lost,’ i.e., ‘John certainly did not win’ ().1.3.2. Claims of the Account

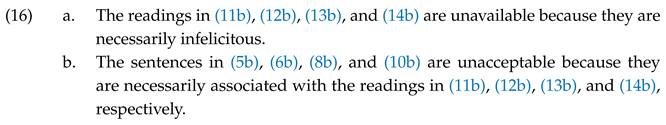

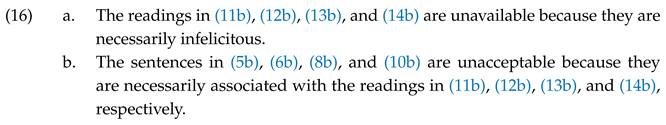

My account of the Vietnamese facts in Section 1.2 consists of the two claims in (16).

I will derive (16a) in Section 2 and derive (16b) in Section 3.

I will derive (16a) in Section 2 and derive (16b) in Section 3.

I will derive (16a) in Section 2 and derive (16b) in Section 3.

I will derive (16a) in Section 2 and derive (16b) in Section 3.2. Partition by Exhaustification

2.1. Presenting PbE

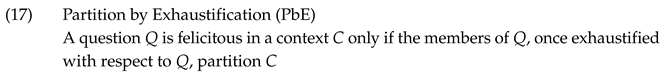

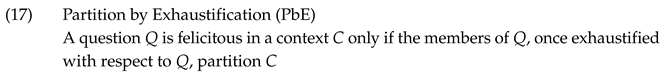

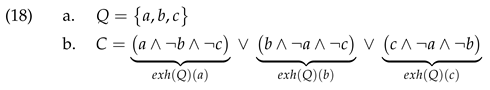

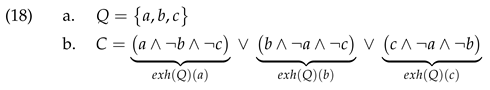

Fox (2019, 2020) proposed the following felicity condition on questions:

As is usually the case with theoretical statements, there is a simple and a sophisticated interpretation. For this discussion, it suffices to apply the simple intepretation of PbE, which I will now present. The reader is advised to consult the above-cited works for the unabridged version and empirical arguments in its favor.

As is usually the case with theoretical statements, there is a simple and a sophisticated interpretation. For this discussion, it suffices to apply the simple intepretation of PbE, which I will now present. The reader is advised to consult the above-cited works for the unabridged version and empirical arguments in its favor.

As is usually the case with theoretical statements, there is a simple and a sophisticated interpretation. For this discussion, it suffices to apply the simple intepretation of PbE, which I will now present. The reader is advised to consult the above-cited works for the unabridged version and empirical arguments in its favor.

As is usually the case with theoretical statements, there is a simple and a sophisticated interpretation. For this discussion, it suffices to apply the simple intepretation of PbE, which I will now present. The reader is advised to consult the above-cited works for the unabridged version and empirical arguments in its favor.The ‘context’ is the set of possible worlds in which all mutual assumptions of the discourse participants are true, i.e., worlds that are considered candidates for the actual world (Stalnaker, 1978, 1998). A question Q is a set of propositions, namely, those that count as its possible answers. A ‘proposition p exhaustified with respect to a question Q,’ written as , is true if p is true and every other proposition in Q is false. Finally, a set of propositions ‘partitions’ a set of possible worlds only if , i.e., only if every world in is such that at least one member of is true in it. Let us consider an example. Suppose which girl came? Alice came , Billie came , Clara came }. What PbE predicts is that Q is felicitous in C only if every world w of C is such that either only Alice came in w, or only Bille came in w, or only Clara came in w.

In other words, PbE predicts, correctly, that which girl came? requires a context in which exactly one girl came (Dayal, 1996).

In other words, PbE predicts, correctly, that which girl came? requires a context in which exactly one girl came (Dayal, 1996).

In other words, PbE predicts, correctly, that which girl came? requires a context in which exactly one girl came (Dayal, 1996).

In other words, PbE predicts, correctly, that which girl came? requires a context in which exactly one girl came (Dayal, 1996).2.2. Deriving the Facts in Section 1.3.1 from PbE

How does PbE help with the facts in Section 1.3.1? Let us look at the ‘good’ questions first: (11a), (12a), (13a), and (14a). All of these questions are sets containing a proposition and its logical negation. Now, if , then , and . This means, given PbE, that these questions require a context . Since is the set of all possible worlds, these questions presuppose nothing: They can be asked ‘out of the blue,’ i.e., without any preconceived ideas about how the actual world is.

So PbE predicts, correctly, that (11a), (12a), (13a), and (14a) are good questions. Does it predict the bad questions—(11b), (12b), (13b), and (14b)—to be bad? The answer is yes. Let us consider these one by one, starting with (11b).

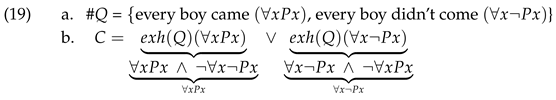

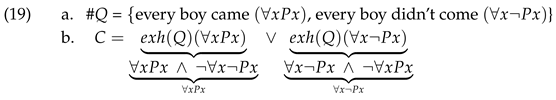

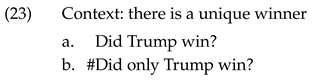

We see that given PbE, the question in (11b), which is reproduced in (19a), requires a ‘homogeneous’ context in which either every boy came or no boys came . The same holds for the question in (12b), reproduced in (20a).

We see that given PbE, the question in (11b), which is reproduced in (19a), requires a ‘homogeneous’ context in which either every boy came or no boys came . The same holds for the question in (12b), reproduced in (20a).

It is known that homogeneous contexts militate against quantifiers in favor of definites (Löbner, 1985; Heim, 1991; Magri, 2009, 2011). Thus, in the (realistic) context where it is presupposed that if the Argentinian team won the World Cup, then every Argentinian (on the team) won, and if they did not win, then no Argentinian (on the team) won. In this context, (21a) is acceptable, while (21b) and (21c) are infelicitous.

It is known that homogeneous contexts militate against quantifiers in favor of definites (Löbner, 1985; Heim, 1991; Magri, 2009, 2011). Thus, in the (realistic) context where it is presupposed that if the Argentinian team won the World Cup, then every Argentinian (on the team) won, and if they did not win, then no Argentinian (on the team) won. In this context, (21a) is acceptable, while (21b) and (21c) are infelicitous.

Thus, the questions in (11b)/(19a) and (12b)/(20a) violate either PbE or the constraint against using quantifiers in homogeneous contexts. In other words, they are necessarily infelicitous. Next, consider (13b), reproduced in (22a).

Thus, the questions in (11b)/(19a) and (12b)/(20a) violate either PbE or the constraint against using quantifiers in homogeneous contexts. In other words, they are necessarily infelicitous. Next, consider (13b), reproduced in (22a).

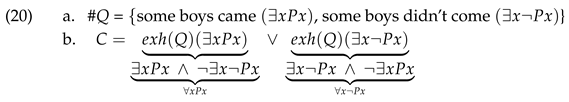

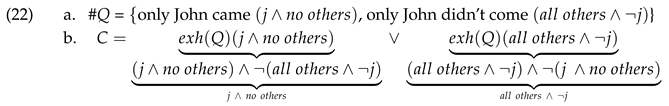

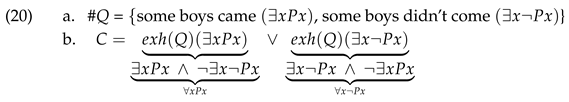

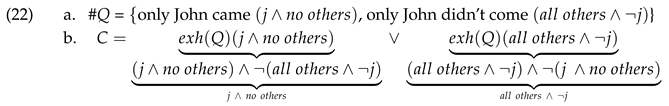

Given PbE, the question in (13b)/(22a) requires a context where either John came and no one else did, or John did not come but everyone else did.6 This is a context where John came is equivalent to only John came, i.e., where only is semantically vacuous. It is a fact that vacuous use of only is infelicitous (Alxatib, 2013, 2020): It is odd to ask the question in (23b), given the (realistic) context that the American presidential election has a unique winner.

Given PbE, the question in (13b)/(22a) requires a context where either John came and no one else did, or John did not come but everyone else did.6 This is a context where John came is equivalent to only John came, i.e., where only is semantically vacuous. It is a fact that vacuous use of only is infelicitous (Alxatib, 2013, 2020): It is odd to ask the question in (23b), given the (realistic) context that the American presidential election has a unique winner.

Thus, the question in (13b)/(22a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against vacuous use of only.

Thus, the question in (13b)/(22a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against vacuous use of only.

We see that given PbE, the question in (11b), which is reproduced in (19a), requires a ‘homogeneous’ context in which either every boy came or no boys came . The same holds for the question in (12b), reproduced in (20a).

We see that given PbE, the question in (11b), which is reproduced in (19a), requires a ‘homogeneous’ context in which either every boy came or no boys came . The same holds for the question in (12b), reproduced in (20a).

It is known that homogeneous contexts militate against quantifiers in favor of definites (Löbner, 1985; Heim, 1991; Magri, 2009, 2011). Thus, in the (realistic) context where it is presupposed that if the Argentinian team won the World Cup, then every Argentinian (on the team) won, and if they did not win, then no Argentinian (on the team) won. In this context, (21a) is acceptable, while (21b) and (21c) are infelicitous.

It is known that homogeneous contexts militate against quantifiers in favor of definites (Löbner, 1985; Heim, 1991; Magri, 2009, 2011). Thus, in the (realistic) context where it is presupposed that if the Argentinian team won the World Cup, then every Argentinian (on the team) won, and if they did not win, then no Argentinian (on the team) won. In this context, (21a) is acceptable, while (21b) and (21c) are infelicitous.

Thus, the questions in (11b)/(19a) and (12b)/(20a) violate either PbE or the constraint against using quantifiers in homogeneous contexts. In other words, they are necessarily infelicitous. Next, consider (13b), reproduced in (22a).

Thus, the questions in (11b)/(19a) and (12b)/(20a) violate either PbE or the constraint against using quantifiers in homogeneous contexts. In other words, they are necessarily infelicitous. Next, consider (13b), reproduced in (22a).

Given PbE, the question in (13b)/(22a) requires a context where either John came and no one else did, or John did not come but everyone else did.6 This is a context where John came is equivalent to only John came, i.e., where only is semantically vacuous. It is a fact that vacuous use of only is infelicitous (Alxatib, 2013, 2020): It is odd to ask the question in (23b), given the (realistic) context that the American presidential election has a unique winner.

Given PbE, the question in (13b)/(22a) requires a context where either John came and no one else did, or John did not come but everyone else did.6 This is a context where John came is equivalent to only John came, i.e., where only is semantically vacuous. It is a fact that vacuous use of only is infelicitous (Alxatib, 2013, 2020): It is odd to ask the question in (23b), given the (realistic) context that the American presidential election has a unique winner.

Thus, the question in (13b)/(22a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against vacuous use of only.

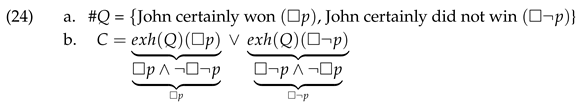

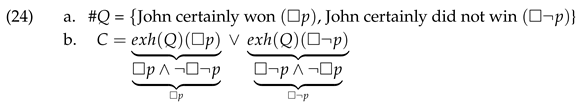

Thus, the question in (13b)/(22a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against vacuous use of only.Finally, we come to the case of (14b), reproduced in (24a).

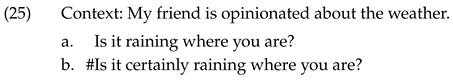

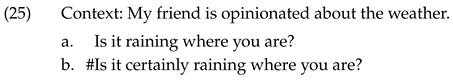

Given PbE, the question in (14b)/(24a) requires an ‘opinionated’ context where it is either certain that John won or certain that John did not win . It has been noted that the use of modal adverbs such as certainly is infelicitous in such contexts (von Fintel & Gillies, 2010). Suppose, for example, that I am on the phone with my friend and I know he is looking out the window. My friend, then, is opinionated about the weather: Either he is certain that it is raining or he is certain that it is not raining. In this context, it would be acceptable for me to ask him the question in (25a), but asking (25b) is odd.

Given PbE, the question in (14b)/(24a) requires an ‘opinionated’ context where it is either certain that John won or certain that John did not win . It has been noted that the use of modal adverbs such as certainly is infelicitous in such contexts (von Fintel & Gillies, 2010). Suppose, for example, that I am on the phone with my friend and I know he is looking out the window. My friend, then, is opinionated about the weather: Either he is certain that it is raining or he is certain that it is not raining. In this context, it would be acceptable for me to ask him the question in (25a), but asking (25b) is odd.

Thus, the question in (14b)/(24a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against using certainly in opinionated contexts.

Thus, the question in (14b)/(24a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against using certainly in opinionated contexts.

Given PbE, the question in (14b)/(24a) requires an ‘opinionated’ context where it is either certain that John won or certain that John did not win . It has been noted that the use of modal adverbs such as certainly is infelicitous in such contexts (von Fintel & Gillies, 2010). Suppose, for example, that I am on the phone with my friend and I know he is looking out the window. My friend, then, is opinionated about the weather: Either he is certain that it is raining or he is certain that it is not raining. In this context, it would be acceptable for me to ask him the question in (25a), but asking (25b) is odd.

Given PbE, the question in (14b)/(24a) requires an ‘opinionated’ context where it is either certain that John won or certain that John did not win . It has been noted that the use of modal adverbs such as certainly is infelicitous in such contexts (von Fintel & Gillies, 2010). Suppose, for example, that I am on the phone with my friend and I know he is looking out the window. My friend, then, is opinionated about the weather: Either he is certain that it is raining or he is certain that it is not raining. In this context, it would be acceptable for me to ask him the question in (25a), but asking (25b) is odd.

Thus, the question in (14b)/(24a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against using certainly in opinionated contexts.

Thus, the question in (14b)/(24a) is necessarily infelicitous: It violates either PbE or the constraint against using certainly in opinionated contexts.2.3. The Scope of ‘Whether’

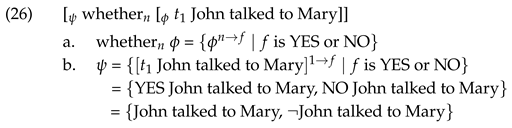

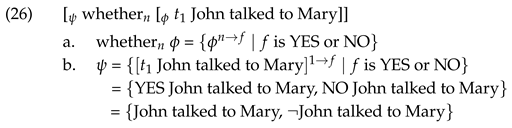

Invoking PbE and the other (semantic and/or pragmatic) constraints to rule out the unavailable readings in (11b), (12b), (13b), and (14b) presupposes that they are not ruled out by syntax. I assume, following many works, that English polar questions contain the operator whether, which is base-generated as sister to propositional constituents and moves to [Spec,C], leaving a trace, as illustrated in (26) (Bennett, 1977; Guerzoni, 2004; Higginbotham, 1993; Krifka, 2001; Larson, 1985). The trace of whether is of type , and the interpretation rule for whethern is provided in (26a), where is the result of replacing expressions bearing index n in with f, YES is the ‘affirmation’ function , which maps a proposition to itself, and NO is the ‘denial’ function , which maps a proposition to its negation. The meaning of (26) is provided in (26b).

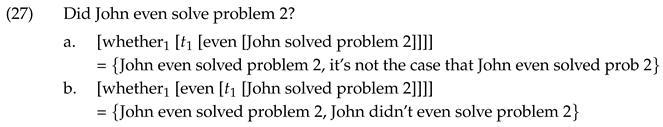

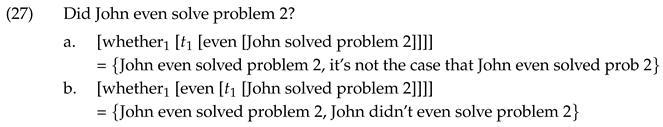

When the prejacent contains more than one propositional constituent, the question is ambiguous, as the trace of whether can be construed at different positions inside the prejacent. A case discussed in Guerzoni (2004) focuses on prejacents containing even, exemplified by (27).

When the prejacent contains more than one propositional constituent, the question is ambiguous, as the trace of whether can be construed at different positions inside the prejacent. A case discussed in Guerzoni (2004) focuses on prejacents containing even, exemplified by (27).

Guerzoni noted two things about (27): (i) It is ambiguous between a reading in which solving problem 2 is hard and a reading in which solving problem 2 is easy; (ii) the ‘easy’ reading comes with a ‘negative bias,’ i.e., the implication that John did not solve the problem. Assume the LFs in (27a) and (27b) provide a natural explanation, as the reader is invited to consult Guerzoni (2004) and see for herself.7

Guerzoni noted two things about (27): (i) It is ambiguous between a reading in which solving problem 2 is hard and a reading in which solving problem 2 is easy; (ii) the ‘easy’ reading comes with a ‘negative bias,’ i.e., the implication that John did not solve the problem. Assume the LFs in (27a) and (27b) provide a natural explanation, as the reader is invited to consult Guerzoni (2004) and see for herself.7

When the prejacent contains more than one propositional constituent, the question is ambiguous, as the trace of whether can be construed at different positions inside the prejacent. A case discussed in Guerzoni (2004) focuses on prejacents containing even, exemplified by (27).

When the prejacent contains more than one propositional constituent, the question is ambiguous, as the trace of whether can be construed at different positions inside the prejacent. A case discussed in Guerzoni (2004) focuses on prejacents containing even, exemplified by (27).

Guerzoni noted two things about (27): (i) It is ambiguous between a reading in which solving problem 2 is hard and a reading in which solving problem 2 is easy; (ii) the ‘easy’ reading comes with a ‘negative bias,’ i.e., the implication that John did not solve the problem. Assume the LFs in (27a) and (27b) provide a natural explanation, as the reader is invited to consult Guerzoni (2004) and see for herself.7

Guerzoni noted two things about (27): (i) It is ambiguous between a reading in which solving problem 2 is hard and a reading in which solving problem 2 is easy; (ii) the ‘easy’ reading comes with a ‘negative bias,’ i.e., the implication that John did not solve the problem. Assume the LFs in (27a) and (27b) provide a natural explanation, as the reader is invited to consult Guerzoni (2004) and see for herself.7For a question such as (11), reproduced in (28), two logical forms can be syntactically generated that correspond to two different base positions of whether.8 The first LF, (28a), represents the felicitous reading and the second LF the infelicitous one, as indicated by ‘#’. The question, (28), is perceived as acceptable because it has one LF that induces an acceptable reading.

The same holds for (12), (13), and (14), reproduced in (29), (30), and (31), respectively.

The same holds for (12), (13), and (14), reproduced in (29), (30), and (31), respectively.

The same holds for (12), (13), and (14), reproduced in (29), (30), and (31), respectively.

The same holds for (12), (13), and (14), reproduced in (29), (30), and (31), respectively.

2.4. Interim Summary

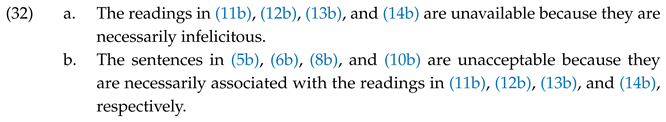

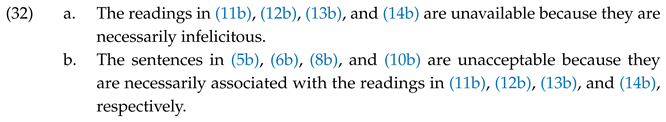

Recall that my account of the Vietnamese facts in Section 1.2 consists of the two claims in (16), reproduced in (32).

I have just explained (32a): The readings are necessarily infelicitous because they are questions that either violate PbE or some other constraints, specifically those against the use of quantifiers in homogeneous contexts, against the vacuous use of only, and against the use of certainly in opinionated contexts. In the next section, I will propose a theory of Vietnamese polar questions that derive (32b). The theory will say, essentially, that the unacceptable questions in Vietnamese, unlike their English counterparts, have only the LF that induces the infelicitous reading.

I have just explained (32a): The readings are necessarily infelicitous because they are questions that either violate PbE or some other constraints, specifically those against the use of quantifiers in homogeneous contexts, against the vacuous use of only, and against the use of certainly in opinionated contexts. In the next section, I will propose a theory of Vietnamese polar questions that derive (32b). The theory will say, essentially, that the unacceptable questions in Vietnamese, unlike their English counterparts, have only the LF that induces the infelicitous reading.

I have just explained (32a): The readings are necessarily infelicitous because they are questions that either violate PbE or some other constraints, specifically those against the use of quantifiers in homogeneous contexts, against the vacuous use of only, and against the use of certainly in opinionated contexts. In the next section, I will propose a theory of Vietnamese polar questions that derive (32b). The theory will say, essentially, that the unacceptable questions in Vietnamese, unlike their English counterparts, have only the LF that induces the infelicitous reading.

I have just explained (32a): The readings are necessarily infelicitous because they are questions that either violate PbE or some other constraints, specifically those against the use of quantifiers in homogeneous contexts, against the vacuous use of only, and against the use of certainly in opinionated contexts. In the next section, I will propose a theory of Vietnamese polar questions that derive (32b). The theory will say, essentially, that the unacceptable questions in Vietnamese, unlike their English counterparts, have only the LF that induces the infelicitous reading.3. An Analysis of Polar Questions in Vietnamese

3.1. Previous Works

Recall the surface profile of Vietnamese polar questions: an affirmative sentence followed by the negation.

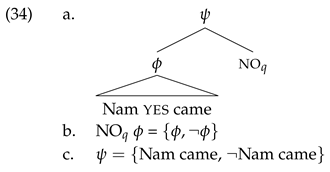

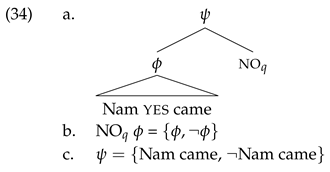

Analyses that have been proposed include Duffield (2007); Phan (2024); Trinh (2005). These accounts differ in details about the affirmative morpheme yes but have in common the idea that underlying this profile is a monoclausal structure where the clause–final negation no functions as a ‘question particle’ akin to whether in English. I will gloss no in this use as noq, where the subscript q is a mnemonic for ‘question.’

Analyses that have been proposed include Duffield (2007); Phan (2024); Trinh (2005). These accounts differ in details about the affirmative morpheme yes but have in common the idea that underlying this profile is a monoclausal structure where the clause–final negation no functions as a ‘question particle’ akin to whether in English. I will gloss no in this use as noq, where the subscript q is a mnemonic for ‘question.’

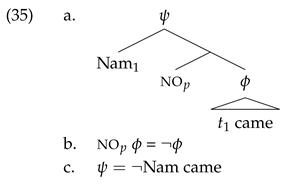

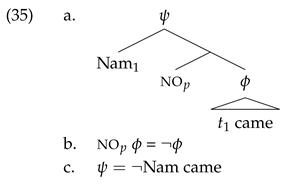

The advantage of this analysis is that it makes Vietnamese polar questions syntactically similar to their English counterparts. There are, however, two problems with this approach. One is that it has to postulate two different nos for Vietnamese: noq for questions, as exemplified in (34) above, and nop for propositional negations, as exemplified in (35) below.

The advantage of this analysis is that it makes Vietnamese polar questions syntactically similar to their English counterparts. There are, however, two problems with this approach. One is that it has to postulate two different nos for Vietnamese: noq for questions, as exemplified in (34) above, and nop for propositional negations, as exemplified in (35) below.

The morphological identity between the two nos would be essentially accidental. The second problem, which I think is more serious, is that this analysis would make it very difficult to state the selectional requirements of noq such that its complement, i.e., the prejacent of the question, can have a definite but not a quantificational subject, a plain but not an only-focused subject, and the modal adverb certainly following but not preceding the verum focus yes.

The morphological identity between the two nos would be essentially accidental. The second problem, which I think is more serious, is that this analysis would make it very difficult to state the selectional requirements of noq such that its complement, i.e., the prejacent of the question, can have a definite but not a quantificational subject, a plain but not an only-focused subject, and the modal adverb certainly following but not preceding the verum focus yes.

In other words, the monoclausal analysis offers no clear solution to the puzzles presented in Section 1.2. While I am not ruling out the possibility of revising this analysis so that it does account for these puzzles, I will explore a different approach, according to which Vietnamese polar questions have a bi-clausal structure.

In other words, the monoclausal analysis offers no clear solution to the puzzles presented in Section 1.2. While I am not ruling out the possibility of revising this analysis so that it does account for these puzzles, I will explore a different approach, according to which Vietnamese polar questions have a bi-clausal structure.

Analyses that have been proposed include Duffield (2007); Phan (2024); Trinh (2005). These accounts differ in details about the affirmative morpheme yes but have in common the idea that underlying this profile is a monoclausal structure where the clause–final negation no functions as a ‘question particle’ akin to whether in English. I will gloss no in this use as noq, where the subscript q is a mnemonic for ‘question.’

Analyses that have been proposed include Duffield (2007); Phan (2024); Trinh (2005). These accounts differ in details about the affirmative morpheme yes but have in common the idea that underlying this profile is a monoclausal structure where the clause–final negation no functions as a ‘question particle’ akin to whether in English. I will gloss no in this use as noq, where the subscript q is a mnemonic for ‘question.’

The advantage of this analysis is that it makes Vietnamese polar questions syntactically similar to their English counterparts. There are, however, two problems with this approach. One is that it has to postulate two different nos for Vietnamese: noq for questions, as exemplified in (34) above, and nop for propositional negations, as exemplified in (35) below.

The advantage of this analysis is that it makes Vietnamese polar questions syntactically similar to their English counterparts. There are, however, two problems with this approach. One is that it has to postulate two different nos for Vietnamese: noq for questions, as exemplified in (34) above, and nop for propositional negations, as exemplified in (35) below.

The morphological identity between the two nos would be essentially accidental. The second problem, which I think is more serious, is that this analysis would make it very difficult to state the selectional requirements of noq such that its complement, i.e., the prejacent of the question, can have a definite but not a quantificational subject, a plain but not an only-focused subject, and the modal adverb certainly following but not preceding the verum focus yes.

The morphological identity between the two nos would be essentially accidental. The second problem, which I think is more serious, is that this analysis would make it very difficult to state the selectional requirements of noq such that its complement, i.e., the prejacent of the question, can have a definite but not a quantificational subject, a plain but not an only-focused subject, and the modal adverb certainly following but not preceding the verum focus yes.

In other words, the monoclausal analysis offers no clear solution to the puzzles presented in Section 1.2. While I am not ruling out the possibility of revising this analysis so that it does account for these puzzles, I will explore a different approach, according to which Vietnamese polar questions have a bi-clausal structure.

In other words, the monoclausal analysis offers no clear solution to the puzzles presented in Section 1.2. While I am not ruling out the possibility of revising this analysis so that it does account for these puzzles, I will explore a different approach, according to which Vietnamese polar questions have a bi-clausal structure.3.2. Proposal: A Bi-Clausal Analysis

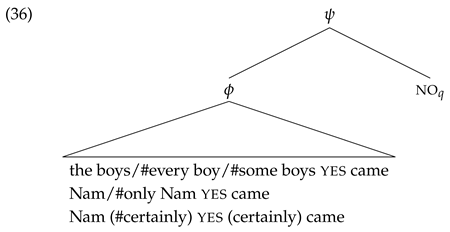

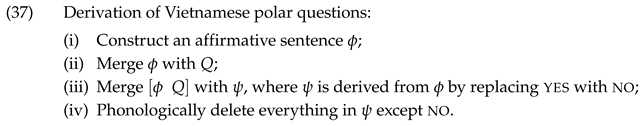

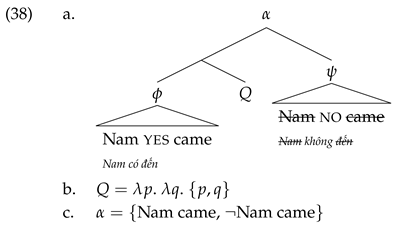

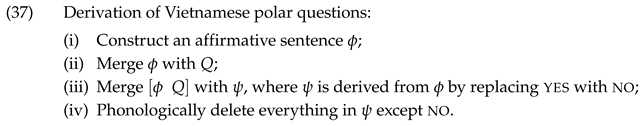

I propose that a polar question in Vietnamese is derived in the following steps.9 The question in (33), then, has the structure in (38a), where strikethrough represents phonological deletion. The meanings of Q and (38a) are provided in (38b) and (38c), respectively.

The question in (33), then, has the structure in (38a), where strikethrough represents phonological deletion. The meanings of Q and (38a) are provided in (38b) and (38c), respectively.

This analysis assigns Vietnamese polar questions a bi-clausal structure that is very different from that of their English counterparts. In English, there is a question operator, whether, which, in similar fashion to other question words in this language, moves from its base position, leaving a trace. Since the trace is silent, the English question is ambiguous if the trace can be construed at different scope sites, as illustrated by (27). In Vietnamese, there is no operator that moves and leaves a silent trace. The position of yes in the affirmative sentence indicates, unambiguously, the position of no in the negated sentence. This means that the pronunciation of a Vietnamese polar question leaves no doubt as to what the positive and negative answers to that question are. This fact plays a crucial role in my resolution of the puzzles in Section 1.2, to which I now turn.

This analysis assigns Vietnamese polar questions a bi-clausal structure that is very different from that of their English counterparts. In English, there is a question operator, whether, which, in similar fashion to other question words in this language, moves from its base position, leaving a trace. Since the trace is silent, the English question is ambiguous if the trace can be construed at different scope sites, as illustrated by (27). In Vietnamese, there is no operator that moves and leaves a silent trace. The position of yes in the affirmative sentence indicates, unambiguously, the position of no in the negated sentence. This means that the pronunciation of a Vietnamese polar question leaves no doubt as to what the positive and negative answers to that question are. This fact plays a crucial role in my resolution of the puzzles in Section 1.2, to which I now turn.

The question in (33), then, has the structure in (38a), where strikethrough represents phonological deletion. The meanings of Q and (38a) are provided in (38b) and (38c), respectively.

The question in (33), then, has the structure in (38a), where strikethrough represents phonological deletion. The meanings of Q and (38a) are provided in (38b) and (38c), respectively.

This analysis assigns Vietnamese polar questions a bi-clausal structure that is very different from that of their English counterparts. In English, there is a question operator, whether, which, in similar fashion to other question words in this language, moves from its base position, leaving a trace. Since the trace is silent, the English question is ambiguous if the trace can be construed at different scope sites, as illustrated by (27). In Vietnamese, there is no operator that moves and leaves a silent trace. The position of yes in the affirmative sentence indicates, unambiguously, the position of no in the negated sentence. This means that the pronunciation of a Vietnamese polar question leaves no doubt as to what the positive and negative answers to that question are. This fact plays a crucial role in my resolution of the puzzles in Section 1.2, to which I now turn.

This analysis assigns Vietnamese polar questions a bi-clausal structure that is very different from that of their English counterparts. In English, there is a question operator, whether, which, in similar fashion to other question words in this language, moves from its base position, leaving a trace. Since the trace is silent, the English question is ambiguous if the trace can be construed at different scope sites, as illustrated by (27). In Vietnamese, there is no operator that moves and leaves a silent trace. The position of yes in the affirmative sentence indicates, unambiguously, the position of no in the negated sentence. This means that the pronunciation of a Vietnamese polar question leaves no doubt as to what the positive and negative answers to that question are. This fact plays a crucial role in my resolution of the puzzles in Section 1.2, to which I now turn.3.3. Resolving the Puzzles in Section 1.2

3.3.1. Explaining the Facts in Section 1.2.1: Definite vs. Quantificational Subjects

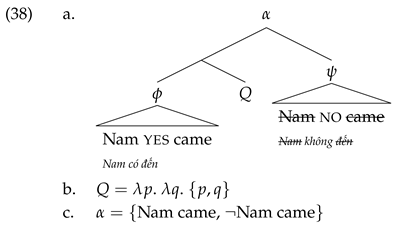

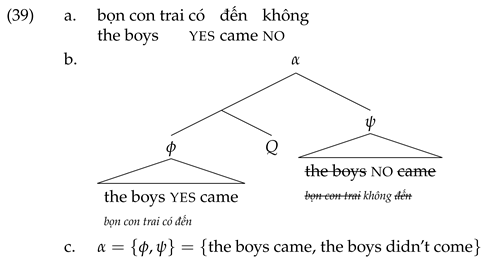

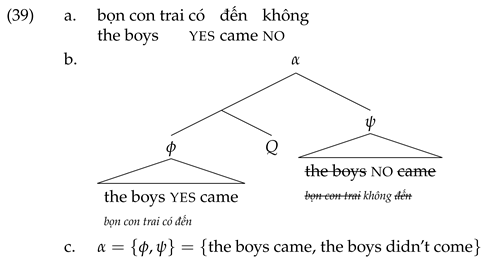

Polar questions with definite subjects are exemplified by (4b), reproduced in (39a). The structure of this question is (39b). Its meaning is (39c).

It is a fact of Vietnamese that bọn con trai có đến means ‘the boys came’ and bọn con trai không đến means ‘the boys did not come.’ Thus, (39a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did the boys come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that bọn con trai có đến means ‘the boys came’ and bọn con trai không đến means ‘the boys did not come.’ Thus, (39a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did the boys come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that bọn con trai có đến means ‘the boys came’ and bọn con trai không đến means ‘the boys did not come.’ Thus, (39a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did the boys come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.

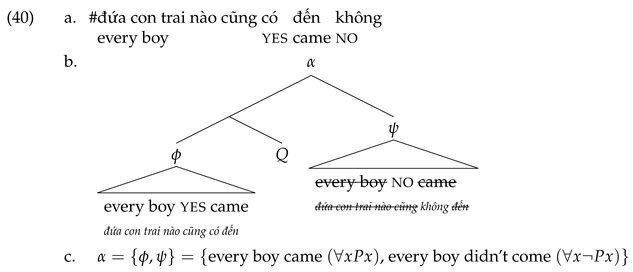

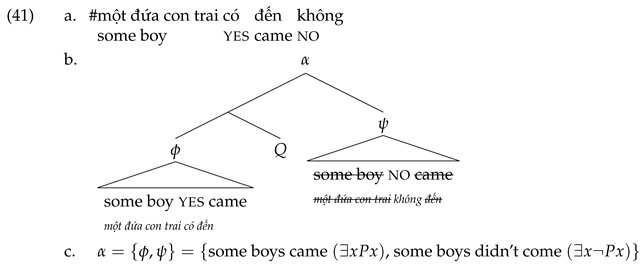

It is a fact of Vietnamese that bọn con trai có đến means ‘the boys came’ and bọn con trai không đến means ‘the boys did not come.’ Thus, (39a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did the boys come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.Let us now deal with the observation that Vietnamese polar questions do not tolerate quantificational subjects. Consider first the case of universal quantifiers, exemplified by (5b), reproduced in (40a). The structure of this question is (40b).

It is a fact of Vietnamese that đứa con trai nào cũng có đến means ‘every boy came’ and đứa con trai nào cũng không đến means ‘every boy did not come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (40a) unambiguously denotes this question, (40a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that đứa con trai nào cũng có đến means ‘every boy came’ and đứa con trai nào cũng không đến means ‘every boy did not come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (40a) unambiguously denotes this question, (40a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that đứa con trai nào cũng có đến means ‘every boy came’ and đứa con trai nào cũng không đến means ‘every boy did not come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (40a) unambiguously denotes this question, (40a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

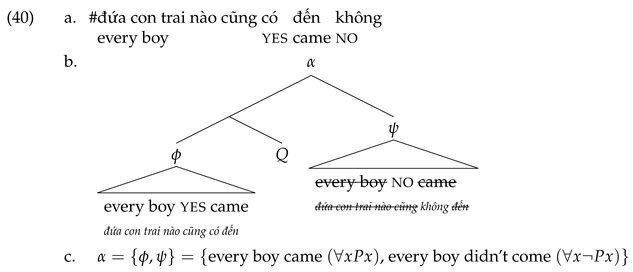

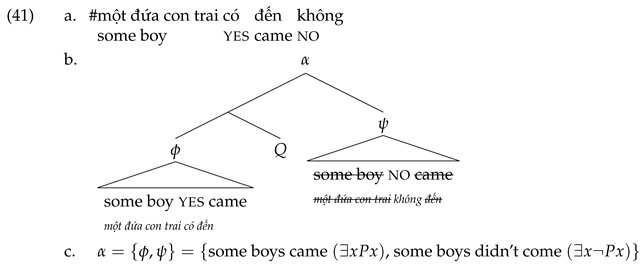

It is a fact of Vietnamese that đứa con trai nào cũng có đến means ‘every boy came’ and đứa con trai nào cũng không đến means ‘every boy did not come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (40a) unambiguously denotes this question, (40a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.Consider next the case of existential subjects, exemplified in (6b), reproduced in (41a). The structure of this question is (41b).

It is a fact of Vietnamese that một đứa con trai có đến means ‘some boys came’ and một đứa con trai không đến means ‘some boys didn’t come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (41a) unambiguously denotes this question, (41a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that một đứa con trai có đến means ‘some boys came’ and một đứa con trai không đến means ‘some boys didn’t come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (41a) unambiguously denotes this question, (41a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that một đứa con trai có đến means ‘some boys came’ and một đứa con trai không đến means ‘some boys didn’t come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (41a) unambiguously denotes this question, (41a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that một đứa con trai có đến means ‘some boys came’ and một đứa con trai không đến means ‘some boys didn’t come’ . However, as shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (41a) unambiguously denotes this question, (41a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.I have thus accounted for the contrast, discussed in Section 1.2.1, between polar questions with definite subjects and polar questions with quantificational subjects.

3.3.2. Explaining the Facts in Section 1.2.2: Plain vs. Only-Focused Subjects

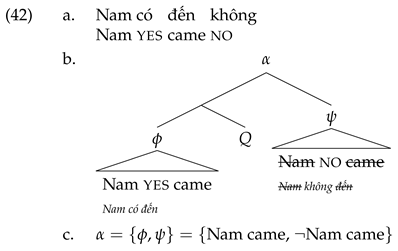

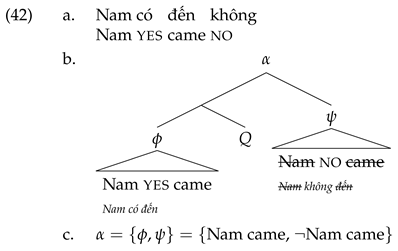

Polar questions with plain subjects are exemplified by (33), reproduced in (42a). The structure of this question is (38a), reproduced in (42b), and its meaning is (38c), reproduced in (42c).

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có đến means ‘Nam came’ and Nam không đến means ‘Nam did not come.’ Thus, (42a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did Nam come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có đến means ‘Nam came’ and Nam không đến means ‘Nam did not come.’ Thus, (42a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did Nam come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có đến means ‘Nam came’ and Nam không đến means ‘Nam did not come.’ Thus, (42a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did Nam come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.

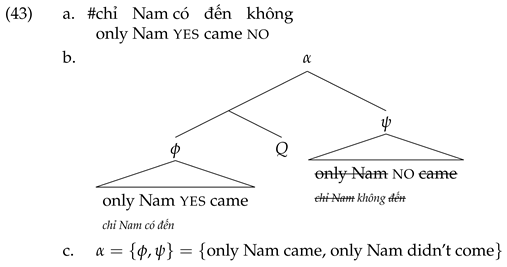

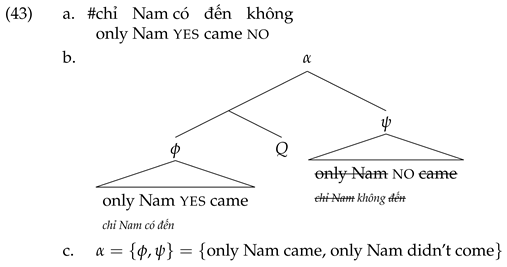

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có đến means ‘Nam came’ and Nam không đến means ‘Nam did not come.’ Thus, (42a) has the exact same meaning as the English question did Nam come? and is predicted to be acceptable, as observed.Polar questions with only-focused subjects are exemplified by (8b), reproduced in (43a). The structure of this question is (43b). Its meaning is (43c).

It is a fact of Vietnamese that chỉ Nam có đến means ‘only Nam came’ , i.e., ‘Nam came but no one else did’ and chỉ Nam không đến means ‘only Nam didn’t come’ , i.e., ‘Nam didn’t come but everyone else did.’ As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (43a) unambiguously denotes this question, (43a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that chỉ Nam có đến means ‘only Nam came’ , i.e., ‘Nam came but no one else did’ and chỉ Nam không đến means ‘only Nam didn’t come’ , i.e., ‘Nam didn’t come but everyone else did.’ As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (43a) unambiguously denotes this question, (43a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that chỉ Nam có đến means ‘only Nam came’ , i.e., ‘Nam came but no one else did’ and chỉ Nam không đến means ‘only Nam didn’t come’ , i.e., ‘Nam didn’t come but everyone else did.’ As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (43a) unambiguously denotes this question, (43a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that chỉ Nam có đến means ‘only Nam came’ , i.e., ‘Nam came but no one else did’ and chỉ Nam không đến means ‘only Nam didn’t come’ , i.e., ‘Nam didn’t come but everyone else did.’ As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (43a) unambiguously denotes this question, (43a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.I have thus accounted for the contrast, discussed in Section 1.2.2, between polar questions with plain subjects and polar questions with only-focused subjects.

3.3.3. Explaining the Facts in Section 1.2.3: Adverb Following vs. Preceding yes

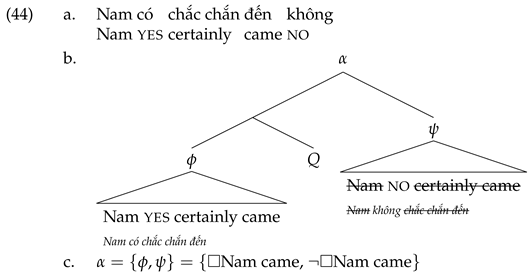

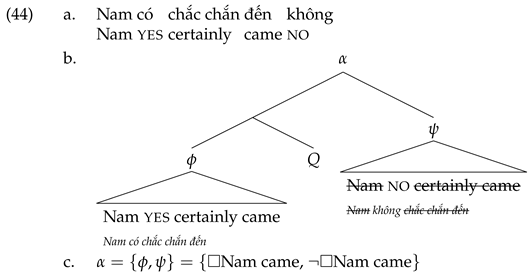

Polar questions in which the modal adverb chắc chắn ‘certainly’ follows yes are exemplified by (10a), reproduced in (44a). The structure of this question is (44b) and its meaning is (44c).

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có chắc chắn đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam không chắc chắn đến means ‘it is not certain that Nam came’ . The two answers to this question, then, are a proposition and its negation. The question is predicted to be without any problem, and it is.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có chắc chắn đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam không chắc chắn đến means ‘it is not certain that Nam came’ . The two answers to this question, then, are a proposition and its negation. The question is predicted to be without any problem, and it is.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có chắc chắn đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam không chắc chắn đến means ‘it is not certain that Nam came’ . The two answers to this question, then, are a proposition and its negation. The question is predicted to be without any problem, and it is.

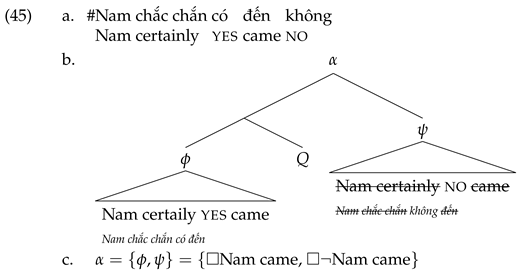

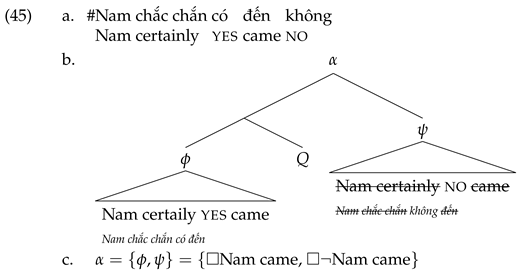

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam có chắc chắn đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam không chắc chắn đến means ‘it is not certain that Nam came’ . The two answers to this question, then, are a proposition and its negation. The question is predicted to be without any problem, and it is.Now let us consider polar questions where the adverb precedes yes. These are exemplified by (10b), reproduced in (45a). The structure of this question is (45b) and its meaning is (45c).

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam chắc chắn có đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam chắc chắn không đến means ‘it is certain that Nam didn’t come’ . As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (45a) unambiguously denotes this question, (45a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam chắc chắn có đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam chắc chắn không đến means ‘it is certain that Nam didn’t come’ . As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (45a) unambiguously denotes this question, (45a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam chắc chắn có đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam chắc chắn không đến means ‘it is certain that Nam didn’t come’ . As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (45a) unambiguously denotes this question, (45a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.

It is a fact of Vietnamese that Nam chắc chắn có đến means ‘it is certain that Nam came’ and Nam chắc chắn không đến means ‘it is certain that Nam didn’t come’ . As shown in Section 2.2, is necessarily an infelicitous question. Since (45a) unambiguously denotes this question, (45a) is predicted to be unacceptable, as observed.I have thus accounted for the contrast, discussed in Section 1.2.3, between polar questions where the modal adverb chắc chắn follows yes and polar questions where this adverb precedes yes.

3.4. Wide-Scope Polarity and Discourse Particles

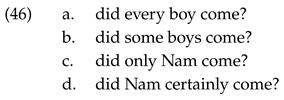

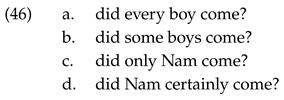

At this point, the reader may be asking how the felicitous readings of the English polar questions in (28)–(31), reproduced here with minimal modification in (46a)–(46d), are expressed in Vietnamese.

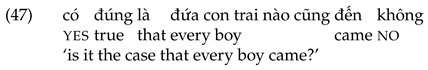

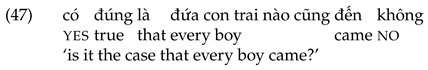

There are several options. One is to place a declarative inside a larger yes … no structure to effect a meaning akin to is it true that ϕ?. Take (46a), for example. One can say (47) to ask this question in Vietnamese.

There are several options. One is to place a declarative inside a larger yes … no structure to effect a meaning akin to is it true that ϕ?. Take (46a), for example. One can say (47) to ask this question in Vietnamese.

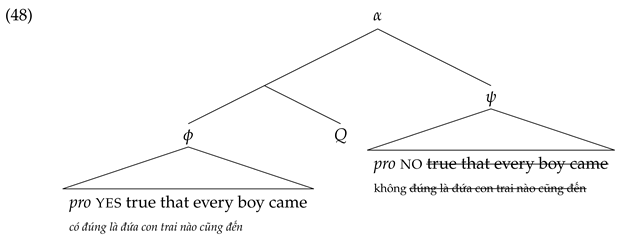

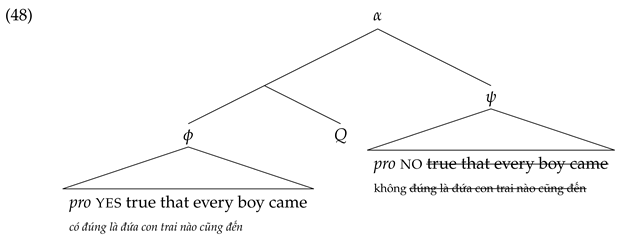

I assume that (47) has the structure in (48), where pro is a silent expletive subject.

I assume that (47) has the structure in (48), where pro is a silent expletive subject.

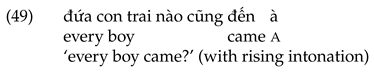

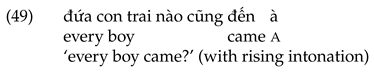

Another strategy is to resort to the discourse particle à, which is appended to a declarative to ask whether the addressee agrees that is true. The meaning that is effected is similar to that of an English ‘declarative’ question, i.e., a yes/no question that has declarative word order and rising intonation (Gunlogson, 2003; Trinh & Crnic, 2011). In most situations, this meaning is, for all practical purposes, close enough to that of a canonical polar question.

Another strategy is to resort to the discourse particle à, which is appended to a declarative to ask whether the addressee agrees that is true. The meaning that is effected is similar to that of an English ‘declarative’ question, i.e., a yes/no question that has declarative word order and rising intonation (Gunlogson, 2003; Trinh & Crnic, 2011). In most situations, this meaning is, for all practical purposes, close enough to that of a canonical polar question.

There are several options. One is to place a declarative inside a larger yes … no structure to effect a meaning akin to is it true that ϕ?. Take (46a), for example. One can say (47) to ask this question in Vietnamese.

There are several options. One is to place a declarative inside a larger yes … no structure to effect a meaning akin to is it true that ϕ?. Take (46a), for example. One can say (47) to ask this question in Vietnamese.

I assume that (47) has the structure in (48), where pro is a silent expletive subject.

I assume that (47) has the structure in (48), where pro is a silent expletive subject.

Another strategy is to resort to the discourse particle à, which is appended to a declarative to ask whether the addressee agrees that is true. The meaning that is effected is similar to that of an English ‘declarative’ question, i.e., a yes/no question that has declarative word order and rising intonation (Gunlogson, 2003; Trinh & Crnic, 2011). In most situations, this meaning is, for all practical purposes, close enough to that of a canonical polar question.

Another strategy is to resort to the discourse particle à, which is appended to a declarative to ask whether the addressee agrees that is true. The meaning that is effected is similar to that of an English ‘declarative’ question, i.e., a yes/no question that has declarative word order and rising intonation (Gunlogson, 2003; Trinh & Crnic, 2011). In most situations, this meaning is, for all practical purposes, close enough to that of a canonical polar question.

4. Loose Ends and Conclusions

Before concluding, I will discuss two loose ends to which attention was drawn in the recent round of reviews of this note.

4.1. Other Focus Particles

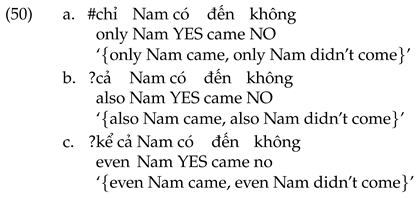

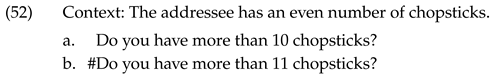

One issue concerns focus particles other than ‘only,’ specifically ‘also’ and ‘even.’ To my ear, there is definitely a contrast between (8b)/(43a), reproduced in (50a), which is severely degraded, and (50b) and (50c), which are slightly degraded.

The theory proposed here predicts the contrast. The context for (50b) would consist of worlds where Nam came and someone else came (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come and someone else did not come (‘no’). The context for (50c) would consist of worlds where Nam came even though him having come was unlikely (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come even though him not having come was unlikely (‘no’).10 These contexts correspond to my intuition about what the answers mean and, as far as I can see, do not conflict with other grammatical aspects of the questions. However, I admit that (50b) and (50c) are not perfectly acceptable. At this time, I will have to leave this fact, and other facts, about ‘also’ and ‘even,’ as well as other focus particles, to future work.11

The theory proposed here predicts the contrast. The context for (50b) would consist of worlds where Nam came and someone else came (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come and someone else did not come (‘no’). The context for (50c) would consist of worlds where Nam came even though him having come was unlikely (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come even though him not having come was unlikely (‘no’).10 These contexts correspond to my intuition about what the answers mean and, as far as I can see, do not conflict with other grammatical aspects of the questions. However, I admit that (50b) and (50c) are not perfectly acceptable. At this time, I will have to leave this fact, and other facts, about ‘also’ and ‘even,’ as well as other focus particles, to future work.11

The theory proposed here predicts the contrast. The context for (50b) would consist of worlds where Nam came and someone else came (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come and someone else did not come (‘no’). The context for (50c) would consist of worlds where Nam came even though him having come was unlikely (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come even though him not having come was unlikely (‘no’).10 These contexts correspond to my intuition about what the answers mean and, as far as I can see, do not conflict with other grammatical aspects of the questions. However, I admit that (50b) and (50c) are not perfectly acceptable. At this time, I will have to leave this fact, and other facts, about ‘also’ and ‘even,’ as well as other focus particles, to future work.11

The theory proposed here predicts the contrast. The context for (50b) would consist of worlds where Nam came and someone else came (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come and someone else did not come (‘no’). The context for (50c) would consist of worlds where Nam came even though him having come was unlikely (‘yes’) and ones where Nam did not come even though him not having come was unlikely (‘no’).10 These contexts correspond to my intuition about what the answers mean and, as far as I can see, do not conflict with other grammatical aspects of the questions. However, I admit that (50b) and (50c) are not perfectly acceptable. At this time, I will have to leave this fact, and other facts, about ‘also’ and ‘even,’ as well as other focus particles, to future work.114.2. Other Quantifiers

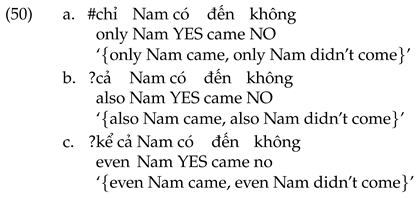

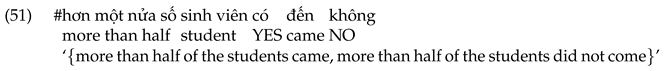

Questions were also raised in the reviews about determiners such as ‘more than half.’ It turns out that (51) is unacceptable.

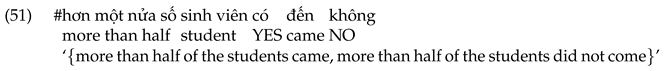

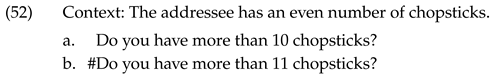

The context, given our account, would consist of worlds where more than half of the students came (‘yes’) and worlds where more than half of the students did not come, i.e., where less than half of the students came (‘no’). Crucially, worlds where half of the students came are excluded. I tentatively propose that this is the reason for the oddness of (51). It seems that the expression more than X is generally odd if X is excluded as a possibility. Thus, if we know that Nam is a fastidious person who never loses any of his beautiful handcrafted wooden chopsticks, it would definitely be weirder to ask him (52b) than to ask him (52a).12

The context, given our account, would consist of worlds where more than half of the students came (‘yes’) and worlds where more than half of the students did not come, i.e., where less than half of the students came (‘no’). Crucially, worlds where half of the students came are excluded. I tentatively propose that this is the reason for the oddness of (51). It seems that the expression more than X is generally odd if X is excluded as a possibility. Thus, if we know that Nam is a fastidious person who never loses any of his beautiful handcrafted wooden chopsticks, it would definitely be weirder to ask him (52b) than to ask him (52a).12 The reader is invited to verify for herself that this argument applies generally to more than X and less than X.13 A comprehensive survey of all subject quantifiers in polar questions in Vietnamese will have to await further research.

The reader is invited to verify for herself that this argument applies generally to more than X and less than X.13 A comprehensive survey of all subject quantifiers in polar questions in Vietnamese will have to await further research.

The context, given our account, would consist of worlds where more than half of the students came (‘yes’) and worlds where more than half of the students did not come, i.e., where less than half of the students came (‘no’). Crucially, worlds where half of the students came are excluded. I tentatively propose that this is the reason for the oddness of (51). It seems that the expression more than X is generally odd if X is excluded as a possibility. Thus, if we know that Nam is a fastidious person who never loses any of his beautiful handcrafted wooden chopsticks, it would definitely be weirder to ask him (52b) than to ask him (52a).12

The context, given our account, would consist of worlds where more than half of the students came (‘yes’) and worlds where more than half of the students did not come, i.e., where less than half of the students came (‘no’). Crucially, worlds where half of the students came are excluded. I tentatively propose that this is the reason for the oddness of (51). It seems that the expression more than X is generally odd if X is excluded as a possibility. Thus, if we know that Nam is a fastidious person who never loses any of his beautiful handcrafted wooden chopsticks, it would definitely be weirder to ask him (52b) than to ask him (52a).12 The reader is invited to verify for herself that this argument applies generally to more than X and less than X.13 A comprehensive survey of all subject quantifiers in polar questions in Vietnamese will have to await further research.

The reader is invited to verify for herself that this argument applies generally to more than X and less than X.13 A comprehensive survey of all subject quantifiers in polar questions in Vietnamese will have to await further research.4.3. Conclusions

I propose a bi-clausal analysis of polar questions in Vietnamese to explain a set of data pertaining to such questions. The explanation relies crucially on Partition by Exhaustification (PbE), a felicity condition on questions in general. To the extent that my account is correct, an interesting picture emerges of the difference between English and Vietnamese with respect to which polar questions are ‘feasible’ in which language. The descriptive statement ‘question Q can be asked in English but not Vietnamese’ turns out to mean ‘the syntax of Q in English allows a felicitous meaning, but the syntax of Q in Vietnamese does not.’ In other words, the two languages differ with respect to the syntactic strategies they employ to formulate a question, but not with respect to the semantic/pragmatic constraints on the use of linguistic expressions in general.

Funding

This work is financially supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARIS) project no. J6-4615.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I thank Itai Bassi, Nigel Duffield, Dan Goodhue, Manfred Krifka, Trang Phan and the audience at ISVL-5 for valuable input and discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Auxiliary có and main verb có can co-occur: Nam có có sách (Nam YES have book) means ‘Nam does have books.’ Note that what I call ‘polar question’ in this note might be considered a subkind of polar question by other scholars who would also include so-called ‘đã-chưa questions’ as polar. A đã-chưa question has the same profile as the polar questions I am describing here, with đã in place of có and chưa in place of không. I will not discuss đã-chưa questions in this paper. |

| 2 | I am describing the standard dialect (Hanoi) of Vietnamese, where Nam có không đến and Nam không có đến are unacceptable. In some southern dialects, Nam không có đến is acceptable (Duffield, 2007). I have nothing to say about these in this note. |

| 3 | The reader may wonder how the intended meaning of the unacceptable questions—(5b), (6b), (8b)—is expressed. I will answer this question in Section 3.4. |

| 4 | Which means that each can be used in the same discourse contexts as the other. |

| 5 | I take the meaning of a question to be the set containing its possible answers (Hamblin, 1958). I will discuss this view in more detail presently. |

| 6 | The reader will have noticed that the presupposition of only is here locally accommodated as part of the assertion. Do we still predict the question to be infelicitous if the presupposition is not locally accommodated? The answer is yes. In that case, the positive answer presupposes no others came and the negative answer presupposes all others came, which means the question ends up with a contradictory, hence unsatisfiable, presupposition. Thus, the account I am presenting here can be considered as the argument that, given PbE, even if the presuppositions of the answers can be locally accommodated, which they can be, the question is still predicted to be infelicitous. |

| 7 | A reviewer asks whether the questions in (27) satisfy PbE. The answer is yes: In each case, the positive and negative answers carve out two different regions in logical space, and the union of these regions is accommodated as the context. PbE, as it is formulated in this note, can always be ‘satisfied’ in isolation since context accommodation is available. The question is whether satisfaction of PbE, i.e., accommodation of a certain context, leads to violation of some other principles. As far as I can see, that is not the case for the questions in (27) (assuming that the presuppositions of the answers can be locally accommodated (see note 6)). |

| 8 | Note that the quantifier every boy itself moves, leaving a trace of type e. |

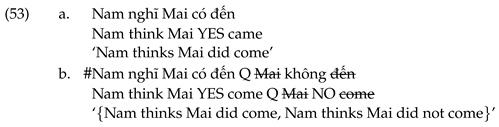

| 9 | Note that an ‘affirmative sentence’ is one containing matrix verum focus, i.e., one where YES occupies the highest auxiliary position. Thus, (53a) is not an affirmative sentence, and (53b) is predicted, correctly, to be unacceptable as a polar question.

More generally, polar questions cannot scope out of embedded positions (modulo parentheticals, which I will not discuss here). The fact that the derivation of polar questions starts from an affirmative sentence, not from a sentence containing an affirmative sentence, or a negative sentence, does not follow from other claims in my account and will have to be taken as a primitive for now. I hope to investigate this point further in future work.

More generally, polar questions cannot scope out of embedded positions (modulo parentheticals, which I will not discuss here). The fact that the derivation of polar questions starts from an affirmative sentence, not from a sentence containing an affirmative sentence, or a negative sentence, does not follow from other claims in my account and will have to be taken as a primitive for now. I hope to investigate this point further in future work. |

| 10 | Again, I assume that it is possible to locally accommodate the presuppositions of ‘also’ and ‘even’ in polar questions (see note 6). |

| 11 | One observation should perhaps be mentioned here: (50c) does not seem to have the ‘negative bias’ reading available for English (27). My hunch is that this is because there is no Vietnamese counterpart of (27a). Note that Guerzoni’s (2004) explanation of the ‘negative bias’ reading of (27) depends crucially on both (27a) and (27b) being possible parses of (27). |

| 12 | A question then arises with respect to the general acceptability of the English question did more than half of the students come?, which, hypothetically, partitions the context into worlds where more than half came and worlds where half or less than half came. Suppose the number of students is even, then there is no problem. However, what if the number is odd? Do we not then predict that the question should be unacceptable, since the possibility that half came is excluded? My very tentative answer is that at the level of grammatical analysis where judgments of acceptability are generated, the scale underlying measurement is dense, even for students, and hence, the possibility that half came is always existent (Fox & Hackl, 2006). Note that given density, (51) is predicted to be infelicitous independently of the parity of the number of students, as ‘half’ is always available as a possibility. Note, also, that this line of reasoning might present a conceptual problem: PbE relates questions to contexts, but density is context-independent. I thank a reviewer for drawing my attention to this important point and will leave an appropriate calibration of context and grammar regarding this issue to future work. |

| 13 | Additionally, to the extent that ‘many’ and ‘few’ can be analyzed as ‘more than half’ and ‘less than half,’ I predict that replacing hơn một nửa số ‘more than half’ in (51) with nhiều ‘many’ or ít ‘few’ will not improve the sentence. This prediction is borne out of facts. |

References

- Alxatib, S. (2013). ‘Only’ and association with negative antonyms [Ph. D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. [Google Scholar]

- Alxatib, S. (2020). Focus, evaluativity, and antonymy: A study in the semantics of ‘only’ and its interaction with gradable antonyms. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M. (1977). A response to Karttunen. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, V. (1996). Locality in wh-quantification: Questions and relative clauses in Hindi. Kluwer Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, N. (2007). Aspects of Vietnamese clausal structure: Separating tense from assertion. Linguistics, 45, 765–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D. (2019). Partition by exhaustification: Comments on Dayal 1996. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 22, 403–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D. (2020). Partition by exhaustification: Towards a solution to Gentile and Scharwarz’s puzzle. Manuscript. MIT. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, D., & Hackl, M. (2006). The universal density of measurement. Linguistics and Philosophy, 29, 537–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerzoni, E. (2004). Even-NPIs in yes/no questions. Natural Language Semantics, 12(4), 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunlogson, C. (2003). True to form: Rising and falling declaratives as questions in English. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin, C. L. (1958). Questions. The Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 36, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, I. (1991). Artikel und Definitheit. In A. von Stechow, & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantik: Ein internationales handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung (pp. 487–535). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham, J. (1993). Interrogatives. In K. Hale, & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20 (pp. 195–228). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, M. (2001). For a structured account of questions and answers. In C. Fery, & W. Sternefeld (Eds.), Audiatur vox sapientiae. A festschrift for arnim von stechow (pp. 287–319). Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. (1985). On the syntax of disjunction scope. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 3, 217–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbner, S. (1985). Definites. Journal of Semantics, 4, 279–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, G. (2009). A theory of individual-level predicates based on blind mandatory scalar implicatures. Natural Language Semantics, 17(3), 245–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, G. (2011,Another argument for embedded scalar implicatures based on oddness in downward entailing environments. Semantics and Pragmatics, 4(6), 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T. (2024). The syntax of vietnamese tense, aspect, and negation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker, R. (1978). Assertion. Syntax and Semantics, 9, 315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker, R. (1998). On the representation of context. Journal of Logic, Language and Information, 7(1), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T. (2005). Aspects of clause structure in Vietnamese [Master’s thesis, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin]. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, T., & Crnic, L. (2011). The rise and fall of declaratives. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 15, 645–660. [Google Scholar]

- von Fintel, K., & Gillies, A. S. (2010). Must … stay … strong! Natural Language Semantics, 18, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).