Abstract

In general, Slovene clitics occur in the second, so-called Wackernagel position of the clause. However, Slovene is exceptional among Wackernagel languages in that the clitic cluster may also occupy the clause-initial position. Imperative sentences have been argued to form an exception to this exception, again allowing the clitic cluster only in the second position. In this paper, we present corpus data that speaks against this second-order exception. We categorize the imperative clauses containing initial clitic clusters found in the corpora into three classes: modally subordinated imperatives, imperatives containing the adversative or the concessive particle, and imperatives occuring as a step in an instruction. We argue that all three classes involve a covert anaphoric element residing in the clause-initial position, yielding an illusion of a clause-initial clitic cluster. In conclusion, initial clitic clusters in Slovene imperatives are not ungrammatical but merely uncommon, and their distribution is ultimately governed by the discourse. We also make a theoretical point, emphasizing that the presented analysis offers support to the view that all discursive information must be represented in syntax.

1. Introduction

Slovene is a Wackernagel language. Clitics normally form a cluster and appear in the second syntactic position of the clause, i.e., following the first syntactic constituent of the clause (1). However, Slovene has also been recognized as exceptional among Wackernagel languages because the clitic cluster (CC) can also be found clause-initially (2) (Marušič, 2008; Milojević Sheppard & Golden, 2002; Toporišič, 2000, i.a.). Imperative clauses have been recognized as forming an exception to this exception, again allowing the CC only in the second position (3) (Milojević Sheppard & Golden, 2000, 2002; Rus, 2005).1

| (1) | Posodi-l | mu | ga | je | včeraj. |

| lend-ptcp.m.sg | yesterday | ||||

| “He lent it to him yesterday.” | |||||

| (2) | Mu | ga | boš | posodi-l | jutri? |

| lend-ptcp.m.sg | tomorrow | ||||

| “Will you lend it to him tomorrow?” | |||||

| (3) | a. | * Mu ga posod-i! |

| lend-imp.2sg | ||

| “Lend it to him!” | ||

| b. | Posod-i mu ga! | |

| lend-imp.2sg | ||

| “Lend it to him!” |

In this paper, we present corpus data that speaks against the ban on initial clitic clusters (ICCs) in Slovene imperative clauses. We categorize ICC imperatives into three classes—modally subordinated imperatives, imperatives containing the adversative or the concessive particle, and imperatives occuring as a step in an instruction—thereby showing that the distribution of ICCs in Slovene imperatives is governed by discourse. We also make a theoretical point, emphasizing that the presented analysis offers support to the view that all discursive information must be represented in syntax (even if covertly).

2. Theoretical Background

The interpretation of the corpus study results in Section 4 and Section 5 requires a diverse theoretical background. Given that, prima facie, ICCs seem to be a syntactic phenomenon, it might come as a surprise that this background is mostly semantic and pragmatic. This is because ultimately, our analysis of ICC imperatives depends crucially on discourse-related factors. In Section 2.1 and Section 2.2, we briefly present modal subordination and narration, as well as the standard approaches to these phenomena. In Section 2.3, we present the Zero Interface view on the syntax–semantics interface held by Ludlow and Živanović (2022) and Živanović and Ludlow (2023), and render the above-mentioned approaches to modal subordination and narration in their framework.

2.1. Modal Subordination

Modal subordination is a phenomenon first discussed in detail by Roberts (1989), with the large body of literature succinctly summarized by Roberts (2021), who describes the phenomenon as involving two syntactically independent clauses containing a modal operator, with the content under the scope of the second modal operator in some sense subordinate to the semantic content under the scope of the first one. The prototypical examples involve overt modal operators: (4) asserts the necessity of a wolf eating the addressee first (the prejacent of the modal ‘would’ in the second sentence), restricted to situations where that wolf comes in (the prejacent of the modal ‘might’ in the first sentence). However, the modals do not need to be overt: (5) contains no overt modals, but (5b) is nevertheless restricted to the situations where a wolf comes in.

| (4) | A wolf might come in. It would eat you first! | (Roberts, 2021) | ||||

| (5) | a. A: What if a wolf gets in? | |||||

| b. B: (Then) we’re in trouble! | ||||||

Another important property of modal subordination is that it licenses anaphoric relations that would otherwise be unavailable. Example (6), which exhibits no modal subordination, is only interpretable if the indefinite noun phrase (and subsequently, the pronoun), refers to a specific wolf, but uninterpretable if the indefinite is interpreted non-specifically. Conversely, the pronoun in (4) can refer to the non-specific, hypothetical wolf introduced in the first sentence.

| (6) | A wolf might come in. I saw it prowling around outside earlier. |

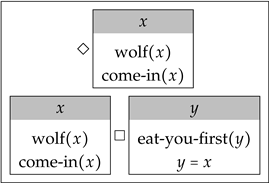

Roberts (1989) couches her analysis of modal subordination in the framework of Discourse Representation Theory (DRT) (Heim, 1988; Kamp, 1981).2 The main idea is that whenever a modal operator (implicit in the case of conditionals) does not have an overt restrictor, a restrictor is supplied via accommodation. The restrictor may be a verbatim copy of some preceding linguistic material, but this is not always the case; often, it is arrived at by some sort of inferential reasoning (Roberts, 2021). Crucially, for our purposes, the restrictor is explicitly introduced into the discourse representation, resulting in discourse representation for (4) as outlined in (7).3 Assuming the possible world interpretation of modality, this discourse representation should be read as follows: a possible world w exists such that a wolf x will come in in w; in every possible world w such that a wolf x comes in, y (which equals x) will eat you first in w.

| (7) |  | (Roberts, 2021) |

Anticipating the results of our corpus study on imperatives, we note that to the best of our knowledge, the literature on modal subordination does not mention modally subordinated imperative sentences. Imperatives are only noted as a possible source of the restriction, as in (8). However, as we will see in Section 4.2, modally subordinated imperative sentences nevertheless exist, and more than that, they allow for ICCs in Slovene.

| (8) | Get a cat. It would take care of the mouse problem in your basement. | (Roberts, 2021) |

2.2. Narration

We outline the research on narratives in two separate areas of pragmatic research, Coherence Theory and the work on the phenomenon known as telescoping.

Coherence Theory traces its beginnings to Hobbs (1978, 1979), and was later elaborated on by (among others) Kehler (2002); Knott (1996); Lascarides and Asher (1993); Webber et al. (2003); Wolf and Gibson (2006); Wolf et al. (2004). Proponents of Coherence Theory argue that a felicitous discourse must be coherent, i.e. that the utterances it is composed of must bear some relationships to each other. For example, (9a) is coherent, because the second sentence provides a reason for John’s trip, but (9b) is not, because normally, John’s liking of spinach has no bearing on his travels. A central claim of Coherence Theory is that “coherence in discourse can be characterized by means of a small number of coherence relations, [each of which] serves some communicative function” (Hobbs, 1978, p. 3), and a central task is to characterize the set of coherence relations.

| (9) | a. John took a train from Paris to Istanbul. He has family there. | (Kehler, 2002, p. 2) |

| b. ? John took a train from Paris to Istanbul. He likes spinach. |

One of the proposed coherence relations is Narration.4 When sentences and are related by Narration, the “event described in is a consequence of (but not strictly speaking caused by) the event described in ”; furthermore, “Narration encode[s] that textual order matches temporal order” (Lascarides & Asher, 1993).5 The mini-discourse in (10a) is an example of Narration; (10b) is not.

| (10) | a. Max stood up. John greeted him. | (Lascarides & Asher, 1993, p. 437; Narration) |

| b. Max fell. John pushed him. | (Explanation) |

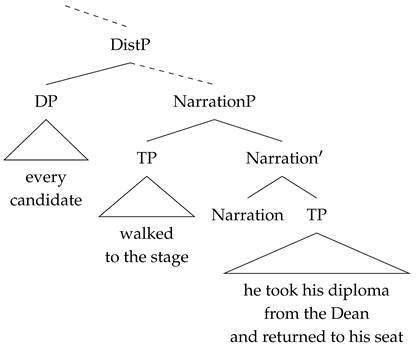

Moving on to the second body of work discussing narratives, it is recognized that they license a phenomenon known as telescoping, where “from a discussion of the general case, we zoom in to examine a particular instance” (Roberts, 1989, p. 717). Telescoping resembles modal subordination in that it licenses some unexpected anaphoric relations: in (11a), the universally quantified ‘degree candidate’ from the preceding sentence can serve as the antecedent for pronouns ‘he’ and ‘his’. However, the two phenomena are not strictly related and exhibit different constraints on accessibility of antecedents. First, unlike modal subordination, telescoping can only arise in the presence of a universal quantifier. Second, and crucially for our purposes, Roberts (1989, p. 717) notices that “the possibility of anaphoric relations in such telescoping cases depends in part on the plausibility of some sort of narrative continuity between the utterances in the discourse.” The lack of such narrative continuity is what makes (11b) inappropriate.

| (11) | Each degree candidate walked to the stage. |

| a. He took his diploma from the Dean and returned to his seat. | |

| b. # He had overcome serious personal challenges to complete the degree. |

2.3. Zero Interface

Ludlow and Živanović (2022) provide an encoding of predicate logic, based on the well-established generalization that all quantification in natural language is conservative, which makes it possible to read the syntactic Logical Forms (LFs) as if they were semantic representations based on predicate logic. The isomorphism between LF and semantic representation makes any translation from syntax to semantics unnecessary, resulting in what they call Zero Interface. A famous semantic puzzle which their account allows them to approach in a new way is donkey anaphora, and in Živanović and Ludlow (2023), they extend the empirical coverage of their endeavor to discourse anaphora in general.

Their treatment of discourse anaphora rests on Stojnić (2021), who aims to show that the resolution of discourse anaphora is not contextual, as is usually assumed, but is governed by a grammatical mechanism. She argues that a fully linguistic account of discourse anaphora is possible once it is recognized that their resolution goes hand-in-hand with the establishment of coherence relations. In her revival of Coherence Theory, she argues that, rather than being a purely pragmatic concept, coherence relations belong to the grammar of language and, in particular, that they should be encoded in the logical form of discourse. Živanović and Ludlow (2023) subscribe to the philosophical aspects of her account, but offer a syntactic reimplementation of her anaphora resolution mechanism. In particular, they argue that the resolution can proceed with what they call discourse LF, an object similar to discourse representations of Discourse Representation Theory (DRT) (Heim, 1988; Kamp, 1981) obtained by a post-syntactic manipulation of sentential LFs on par with inferential reasoning. In their system, the function of the DRT accessibility relation is taken over by the central relation of their deductive system, p-scope, and it is this relation that powers anaphora resolution.

Inherent in Živanović and Ludlow (2023)’s syntactic reimplementation of Stojnić’s (2021) resolution mechanism is the assumption, necessitated by Zero Interface, that coherence relations do not only belong into the grammar, as claimed by Stojnić (2021), but are part and parcel of LF. In other words, they assume that each coherence relation is introduced by a dedicated functional projection. Indeed, upon a closer inspection, coherence relations seem intimately connected to the structure of a sentence. This is (explicitly or implicitly) acknowledged even in the pragmatic research. Kehler (2002) is an interdisciplinary work including both pragmatics and syntax, and even within purely pragmatics research, it is a typical strategy (see e.g., Knott, 1996; Wolf & Gibson, 2006) to identify a coherence relation based on which explicit connective (or, more generally, cue phrase) it overtly deploys; in the absence of an overt connective, the identification relies on the judgment whether the discourse retains its meaning when a particular connective is added. On the syntactic side, the claim that coherence relations can be found in LF should be rather unsurprising. The cartographic research has firmly located discourse-related functional heads in the CP layer of the clausal structure (Rizzi, 1997). Specifically, Haegeman’s (2012, p. 164) typology of adverbial clauses makes it quite clear that coherence relations play an important role in the syntax of natural language.

Following the Zero Interface approach, we render Roberts’s (2021) (7) as outlined in (12). We cannot go into the detail of how Živanović and Ludlow (2023) translate the structure of the DR boxes into LF. For our purposes, it only matters that the two boxes representing the meaning of the second sentence of (4) both correspond to LF constituents. In particular, the accommodated restrictor (the left box) is present in the syntactic structure, and as it needs to take scope over the entire proposition, it has to occur in the highest syntactic position, the specifier of CP. For concreteness, and congruent with the fact that the modal’s restriction may be provided by an overt conditional clause, we assume that the accommodated restrictor takes the form of a covert conditional, but nothing hinges crucially on the exact syntactic form of the restrictor, only its presence and location.

| (12) |  |

Turning to narration, Živanović and Ludlow (2023) explain the telescoping ability of narratives containing a universal by proposing that a sequence of two sentences related by Narration receives the discourse LF shown in (13). They make two critical assumptions. First, they assume that non-first items in a narrative are impoverished structures, in the spirit of the truncation approaches to various phenomena familiar from generative syntax.6 This allows them to embed the entire second LF into the first one. Second, they assume that the functional head hosting the coherence relation of Narration is located low in the CP layer, just above TP. Semantically, this makes sense because Narration is relating eventualities, whose LF reflex is a TP. Furthermore, this location makes it possible to relate the constraints imposed by the narration to those imposed by the tense system, and also place the novel utterance within the scope of the universal noun phrase. Following Beghelli and Stowell (1997), they assume that the universal DPs move into Dist(ributive)P, located above TP.

| (13) |  |

3. Searching the Corpora

We searched for ICC imperatives using NoSketch engine at clarin.si (accessed on 1 August 2024) in two written corpora: Gigafida 2.0, a reference corpus of written Standard Slovene,7 and Janes 1.0, a corpus of social media texts (Erjavec et al., 2018).8 The procedure involved two steps. We first constructed and deployed the CQL search string shown in (14). This yielded 1414 hits, with 410 in Gigafida and 1004 in Janes. The hits contained many false positives, however; narrowing down the result set further automatically turned out to be unfeasible. We proceeded with manual filtering, which led to 98 sentences with imperative ICC clauses, 37 in Gigafida and 61 in Janes. In what follows, we comment on the construction of the search string, before implementing manual filtering. The subsequent categorization of the final results into three distinct discourse environments is presented in Section 4.

The overall composition of the search string in (14) is as follows: We search for a string of tokens beginning with a sentence-initial clitic (lines 1–2) and ending with an imperative verb (line 4). The clitic and the verb may be adjacent, or separated by any number of non-verbal tokens except punctuation (line 3). The matched tokens should be found in a single sentence (line 5).

| (14) | 1 ( <s> [word="(?i)me|mi|ga|mu|ji|jo|ju|jima|jih|jim|se|si"] |

| 2 | [word="Me|Mi|Ga|Mu|Ji|Jo|Ju|Jima|Jih|Jim|Se|Si"] ) | |

| 3 [!(tag="G.*"|tag="U")]{0,} | |

| 4 [tag="Gg.v.*"] | |

| 5 within ( <s/> !containing [word="\?|: |

While we relied on corpus tags to recognize imperative verbs (line 4), it turned out to be more practical to recognize clitics by listing them explicitly (lines 1–2). Note that the list does not include verbal auxiliary clitics, which do not occur in imperatives. We also decided against searching for second person singular clitic personal pronouns ‘ti’2sg.dat and ‘te’2sg.acc, as they have non-clitic homographs ‘ti’ “you”1sg.nom and ‘te’ “this”fem.sg.nom/acc, which leads to too many false positives. However, the exclusion is innocuous: non-nominative, second person pronouns are not expected to occur in imperative clauses, as that would lead to the Principle B violation.9 In non-subject positions, the addressee is referred to using reflexive pronouns ‘si’2sg.dat.refl and ‘se’2sg.acc.refl, which were included in the list.

As corpus annotations of sentence boundaries are not perfect, we searched for ICCs using not only the <s> tag immediately preceding a case-insensitive regular expression catching the clitics (line 1), but also by searching for title-cased clitics (line 2). We have decided against searching only for the latter as there is no guarantee that the authors of the non-proof-read social media texts would use capitalization as required by the norm. The non-perfect annotation of sentence boundaries is also why we explicitly excluded matches containing emoticons (line 5). These are often used as final punctuation in social media texts, which is not reflected in corpus annotations.

As mentioned above, most of the hits yielded by the automatic search were false positives and needed to be filtered out manually. The most common reason for false positives was that the clitic cluster was not actually sentence-initial. In some examples, the sentence-initial phrase occurs in the left context, so the false positive presumably occurs due to imperfections of the sentence segmentation algorithm. Most often, however, the corpus does not contain the initial word of a post at all, i.e., the initial word is missing and the corpus sentence starts with a lowercased word. Most commonly, the missing word is ‘Bog’ “God” (15a), but there are also examples with proper names (15b) and other words, mainly nouns (15c).

| (15) | a. | |

| | ||

| “God help her!” | ||

| b. | | |

| | ||

| “Kučan now wants to own the independence, as well.” | ||

| c. | | |

| | ||

| “Give me a kiss, I said!” |

The missing-proper-name situation typically occurred in social media posts (especially Twitter/X), presumably because the corpus parser misinterpreted the combination of a user handle (@username) and the real (and capitalized) initial word of the sentence as irrelevant, perhaps as a part of the general strategy for avoiding the inclusion of proper names in the corpus (although normally, these are replaced by [per], for “personal name”). Whereever possible, we verified that the sentence-initial word was indeed missing by locating the original sources. As virtually all of the problematic examples from the social media corpus we could access were confirmed to exhibit the missing-initial-word problem, we decided to disregard the problematic lowercase-initial social media posts whose sources could not be found. (On Twitter/X, the posts may be unavailable either because of the author’s privacy settings, or because the author has unsubscribed from the service.)

The second most common reason for false positives was that the intended ICC contained the non-clitic pronoun ‘mi’ “we”1pl.nom, homographic with the target clitic pronoun ‘mi’ “I”1sg.dat, as illustrated in (16). Note that strategy of removing ‘mi’ from the list of allowed clitics, deployed for ‘ti’ and ‘te’, could not have been applied here, as the clitic ‘mi’ can and does occur in imperative sentences.

| (16) | Mi | pa | se | podajmo | nekoliko | južneje | … |

| We | pa | refl | go | somewhat | more.south | … | |

| “As for us, let’s go somewhat more south …” | |||||||

We encountered several other common sources of easily recognizable false positives. Some intended ICCs contained ‘še’ spelled as ‘se’ (without the hacek, 17). Sometimes, a word was misannotated as an imperative verb due to homonymy—most commonly ‘spomnite’ “remember”, homonymous between imperative and indicative 2nd person plural (18), and ‘recimo’ “say”, an archaic first person plural imperative which functions as a particle used for (i.a.) introducing hypotheticals and exemplification (19). Several sentences exhibited poetic, metrum-oriented word order (20). We also found examples of foreign words and proper names homographic to Slovene clitics, and occasionally, the target clitic pronoun was capitalized as the beginning of a multi-word proper name, such as a book title or a product name.

| (17) | se→še | enkrat | preber-i | kaj | si | napisu |

| refl→additionally | once | read-imp | what | aux.2sg | write.ptcp.m.sg | |

| “Read what you wrote once again.” | ||||||

| (18) | Se | še | spomn-i-te | naših | bendov? |

| refl | still | remember-tv.prs-2pl | our | bands | |

| “Do you still remember our bands?” | |||||

| (19) | Si | recimo | predstavlj-a-te, | … ? |

| refl | for.example | imagine-tv.prs-2pl | ||

| “Can you for example imagine that … ?” | ||||

| (20) | Me | groba | noč | in | strah | obda-j | … |

| rough | night | and | fear | surround-imp | |||

| “Let the crude night and fear surround me …” | |||||||

Filtering out the easily recognizable false positives left us with 129 candidate ICC imperative sentences. We could assign most of these to one of the three categories, which are described in Section 4. There was, however, a residue of 31 sentences that fit into none of the developed categories, and which we at the same time judged to be, at most, marginally acceptable. Given that the categorization of the acceptable ICC imperatives turned out to be based on discourse, we investigated the linguistic context of these marginally acceptable examples in more detail.

Nine of the problematic sentences were preceded by ‘–’, indicating that they occur as an item in a list (21). Typically, other sentences beginning with ‘–’ occured in their vicinity in the corpus, reaffirming this conclusion. An inspection of the original source, when it could be located, showed that we are most often dealing with a list of advices in a magazine. Such lists typically begin with a list header that introduces the items, such as ‘vedno’ “always”, followed by several instructions. For a grammatical reading of the instructions, one needs to prefix the header to each instruction, which puts the CC in the usual second position behind the list header. (The inspection of the context of the list item candidates also filtered out several instances of indicative sentences containing verbs with homographic indicative and imperative forms, e.g., ‘reš-i-te’ “save-ind/imp-2pl”. These are not counted among the 31 problematic examples.)

| (21) | Vedno “Always”: |

| – … | |

| – Se pred vožnjo in pred težavnimi ali nevarnimi opravili prepričajte, da zdravila ne povzročajo zaspanosti ali kako drugače ne prizadenejo vaših sposobnosti. | |

| “Before driving and difficult or dangerous tasks, make sure that the medication does not cause sleepiness or harm your abilities in some other way.” | |

| – … |

The detailed investigation of the list items reinforced the lesson taught by the acceptable examples (which will be presented in Section 4): the linguistic context—sometimes even large chunks thereof—is of utmost importance for establishing the grammaticality of ICC imperatives. We have therefore decided to disregard 10 of the problematic cases for which neither the relevant context could be determined from the corpus itself, nor could the original source be located.10 Among these, there were five sentences beginning with ellipsis points, indicating that in the author’s mind, the clitic pronoun might not be clause-initial after all, but we could not find the preceding context which the ellipsis points refer to.

| (22) | ?… si | ogle-j-te | posnetek! | ☞ [URL] [URL] |

| … | look.at-imp-2pl | recording! | ||

| “Look at the recording!” | ||||

We were left with six sentences, among them (23), for which we could determine the relevant context (and which we, remember, judge to be at most marginally acceptable). One possibility is that their authors are speakers of one of the western, Romance-adjacent Slovene dialects. In these dialects, the position of clitics is less restricted than in the rest of Slovene, and ICCs appear more freely in general (Zuljan Kumar, 2022).11 However, as all six examples were found in social media posts, which are not proof-read, another possibility is that their authors would ultimately find them unacceptable as well. This hypothesis is corroborated by comparing the frequency of the problematic clitic-first order to the frequency of the clitic-second order, which reveals that the latter is always radically higher. For example, Janes contains 5 examples of a clitic-first ‘Se ne sekiraj’ “ not worry” and 460 examples of a clitic-second ‘Ne sekiraj se’ “not worry ”, and there are 2 hits for ‘Si preberite’ “ read”, as opposed to 1061 hits for ‘Preberite si’ “read ”.

| (23) | ? A: Danes se nisem spomnil še nič kaj neumnega, kaj šele pametnega, vredno objave. Se oproščam :-) | |||

| B: Se | ne | sekira-j | –za neumnosti skrbita vlada in malomarna. | |

| neg | worry-imp.2sg | |||

| “A: Today I haven’t yet thought of anything stupid, let alone smart, worthy of posting. I’m sorry :-) | ||||

| B: Don’t worry –the government and the [careless one](?) take care of stupidities.” | ||||

4. Results

The manual filtering of the corpus search results ultimately led to 98 imperative sentences containing an ICC. It turned out that they can be grouped into three discourse-based categories (note that all three categories are represented in both corpora):

- Imperative sentences containing certain discourse particles;

- Modally subordinated imperative sentences;

- Imperative sentences appearing within instructions.

In this section, we present a representative sample of the result set by category. The full dataset is available as Živanović and Štarkl (2025). It also contains the 31 examples of non-obvious (potential) false positives discussed at the end of the previous section. A quantitative overview of the dataset is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The quantitative overview of the ICC imperatives found in the corpora.

4.1. Discourse Particles

Most of the ICC sentences found in the corpora contained one of a small set of discourse particles. The most common of these particles, already noticed by Dvořák (2005), is ‘pa’ (24–25). Although highly multifunctional, ‘pa’ is most commonly an adversative particle: in (24b), it might be unexpected that we might have to stop planting before the end of the autumn, given that the preceding advice was to plant the entire autumn. (We discuss the difference between the two batches of ‘pa’-examples in Section 5.2). Additionally, ICCs are licensed by the particle ‘pač’, at least when it expresses resignation to the given facts or circumstances (26): in (26a), the high headwind speed is undesired, but as there is nothing we can do about it, we can at least keep the peace of mind by imagining that we’re cycling uphill. (Note that in absence of the respective particle, the examples below are ungrammatical.)

| (24) | a. | Da za tovrstne ceremonije nimate časa, boste rekli? | |||||||||

| Si | ga | pa | vzem-i-te! | ||||||||

| pa | take-imp-2pl | ||||||||||

| “That you don’t have time for such ceremonies, you say? Well, take the time!” | |||||||||||

| b. | Sadite lahko celo jesen, če so temperature dovolj visoke. | ||||||||||

| Se | pa | vseeno | ravna-j-te | po | tem, | ||||||

| pa | nevertheless | rule-imp-2pl | after | this, | |||||||

| da prenehate saditi vsaj šest tednov pred prvo zmrzaljo, … | |||||||||||

| “You may plant the entire autumn, if the temperatures are high enough. Do however pay attention to stop planting at least six weeks before the first frost, …” | |||||||||||

| c. | Tako naj vas trenutne izgube ne odvrnejo od vlaganja, ampak se še naprej držite svojega varčevalnega načrta ali v teh časih postopno namenite za borzo več denarja. Tako ne boste čez nekaj let znova objokovali zamujene priložnosti. | ||||||||||

| Se | pa | v | teh | negotovih | časih | izogiba-j-te | posojil | in | izvedenih | ||

| pa | in | these | uncertain | times | avoid-imp-2pl | loans | and | derived | |||

| finančnih instrumentov z visokimi vzvodi, … | |||||||||||

| financial instruments with high leverages | |||||||||||

| “So don’t let the current losses make you refrain from investing, but stick to your investment plan or gradually put even more money into the stock market. This way, you will not cry over a missed opportunity in a couple of years. However, in these uncertain times, do avoid loans and derived financial instruments with high leverage, …” | |||||||||||

| (25) | a. | Na peto mesto smo tokrat postavili juho, ki je na pogled najbolj simpatična: […]. | |||||

| Pripomba, ki je odnesla boljšo uvrstitev: […] | |||||||

| Si | pa | ta | recept | zapomn-i-te; | […] | ||

| refl.dat | pa | this | recipe | remember-imp-2pl | |||

| “The fifth place goes to the soup which looks the best […] The remark, which prevented it to be placed higher: […] Nevertheless, do remember this recipe; […]” | |||||||

| b. | To za zdaj še ni zame. | Me | pa vpraša-j-te | čez | 40 let, | … | |

| I.acc | pa ask-imp-2pl | after | 40 years.gen | ||||

| “This is not for me at the moment. However, do ask me in 40 years, …” | |||||||

| (26) | a. | Za kolesarjenje je moteče že, če piha (nasproti) tam od 20 do 30 kilometrov na uro, ampak to ne pomeni, da se ne da poganjati pedalov. | ||||

| Si | pač predstavlja-j-te, | predstavlja-j-te, | ||||

| pač | imagine-imp-2pl | |||||

| da od Murske Sobote do Beltinec grizete v klanec. | ||||||

| “For cycling, the (head)wind speeds of 20 to 30 kilometers per hour can already be disturbing, but this does not mean that one cannot pedal. Just imagine that you’re riding uphill from Murska Sobota to Beltinci.” | ||||||

| b. | Starši se moramo nadzorovati in si vzeti dovolj časa, da nismo nervozni in na primer zaradi pomanjkanja časa ne posegamo v samostojnost otrok. | |||||

| Si | pač | načrtuj-mo | čas | drugače. | ||

| pač | plan.imp-1pl | time | differently | |||

| “As parents, we should control ourselves and take enough time, so that we are not nervous and, for example, due to lack of time, intrude into the independence of the children. We should simply plan our time differently.” | ||||||

Two other candidates for particle licensing the ICC in an imperative clause are the encouraging particle ‘kar’ (27a), and the particle ‘raje’ that introduces an alternative that the speaker judges to be better (27b). However, we judge these sentences to be less acceptable than sentences involving ‘pa’ and ‘pač’, which is congruent with the small number of occurrences in the corpus. Additionally, a closer inspection of the context revealed that the example we found the most acceptable (it involves ‘kar’) actually belongs to the category of modally subordinated imperatives, which we discuss in the following section. Finally, searching for sentences with ‘kar’ and ‘raje’, and the CC in the usual second position revealed that those are much more common. We found 1718 examples of ‘kar’ + CC and 1620 examples of ‘raje’ + CC. They are illustrated in (28); note that ‘kar’ must be adjacent to the verb, so the sentence-initial position in contains ‘kar’ + verb. These numbers are in stark contrast to the same experiment with ‘pač’, where searching for ‘pač’ + CC results in merely two hits. Searching for ‘pa’ + CC yields 2325 results, but note that the ratio of CC + ‘pa’ vs. ‘pa’ + CC is still much higher than the ratio of CC + ‘kar/raje’ vs. ‘kar/raje’ + CC, and that the multifunctional ‘pa’ in the initial position has more functions than when it follows the ICC, among them a very common coordinative function. In conclusion, the status of ‘kar’ and ‘raje’ as ICC licencers is dubious, although not rejectable out of hand, and requires further research.

| (27) | a. | ? Janše ne damo! | Ga | kar | ime-j-te, | ga ne rabimo. | ||

| kar | have-imp-2pl | |||||||

| “We’re not giving away Janša! Go ahead, have him, we don’t need him.” | ||||||||

| b. | ? Ne bodi mulc! | Se | raje | fajn | v | postelji | povalja-j. | |

| rather | well | in | bed | roll-imp.2sg | ||||

| “Don’t be such a teenager! Better roll well in the bed.” | ||||||||

| (28) | a. | Šolska pravila so javna. | Kar | preber-i | si | jih! |

| kar | read-imp.2sg | refl | them.acc | |||

| “The school rules are public. Go ahead, read them!” | ||||||

| b. | Dobro vem, kako je z njim, nikar mi zdaj ne pripoveduj o tem. | |||||

| Raje | mi | pove-j, | kaj se s tabo dogaja. | |||

| rather | I.dat | tell-imp.2sg, | ||||

| “I know very well how he is doing, no need to tell me about this now. | ||||||

| Rather tell me what’s up with you.” | ||||||

4.2. Modally Subordinated Imperatives

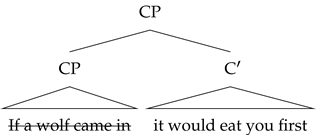

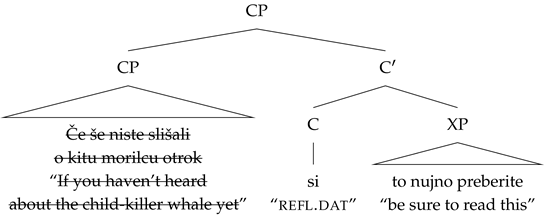

The set of imperative sentences with an ICC revealed by our search contains several examples that bear all the hallmarks of modal subordination (see Section 2.1).12 The crucial observation regarding the examples in (29) is that the addressee should not follow the given directive unconditionally, but only if some contextually determined condition is obtained. In (29a), the addressee does not need to read the linked web page if they already know about the child-killer whale; in (29b), A directs B to move away only if everybody is working; and so on.

| (29) | a. | Če še niste slišali o kitu morilcu otrok … | |||||||

| Si | to | nujno | preber-i-te. | [URL] | |||||

| this | necessarily | read-imp-2pl | |||||||

| “If you haven’t heard about the child-killer whale yet … | |||||||||

| Be sure to read this. [URL]” | |||||||||

| b. | A: Če vsi jočejo, joči z njimi. Če se vsi smejijo, se smej z njimi. | ||||||||

| B: Kaj pa, če vsi delajo? | |||||||||

| A: Se | umakn-i, | da | jih | ne | moti-š. | ||||

| move.away-imp.2sg, | that | neg | disturb.prs-2sg | ||||||

| “A: If everybody is crying, cry with them. If everybody is laughing, laugh with them. | |||||||||

| B: And what if everybody is working? | |||||||||

| A: Move away, so that you don’t disturb them.” | |||||||||

| c. | A: Uf, da me tko pričaka … [a photo of a woman in an appealing posture] | ||||||||

| B: … | jo | pol | še | k | meni | pošlj-i | … ;) | ||

| then | also | to | me | send-imp.2sg | |||||

| “A: Uff, to have her wait for me like that … | |||||||||

| B: … send her to me as well … ;)” | |||||||||

| d. | Kaj potrebujete za lastno solarno elektrarno? | ||||||||

| Si | preber-i-te | v | članku: | [URL] | |||||

| refl | read-imp-2pl | in | article | ||||||

| “What do you need for your own solar power plant? | |||||||||

| Read about it in the following paper: [URL]” | |||||||||

The other important characteristic property of modal subordination, licensing of additional anaphoric relations, is demonstrated by (29b): ‘jih’ “them” is anaphoric to ‘vsi’ “everybody” from the third question. Admittedly, (29b) is the only example which exhibits this property, but this is not very surprising, as the number of modally subordinated imperatives in our dataset is small. However, our examples also exhibit other signs indicative of modal subordination. For example, (29c) contains an overt ‘pol’ (in Standard Slovene, ‘potem’) “then”, which is usually analyzed as anaphoric to the reference time in the preceding sentence, which is also a feasible analysis of (29c).

Finally, four out of the seven corpus examples we have categorized as involving a modally subordinated imperative consist of a conditional and an imperative clause connected by ellipsis points, as seen from (29a) above. This might imply that these examples do not consist of two syntactically independent sentences and thus do not count as instances of modal subordination. However, in all these examples, the imperative clause starts with a capital letter, indicating that might be an independent sentence after all. Furthermore, even if these turn out to be mono-sentential (in the age of auto-correct, the initial capital might not be a very realiable indicator of a start of a sentence), the remaining three examples cannot be analyzed as a single sentence. For example, the condition in (29b) is embedded, and in (29c) the condition-to-be is not introduced by ‘če’ “if” but by complementizer ‘da’ “that” in the function of expressing a wish. In the latter example, the bi-sentential nature of the example is also indicated by the fact that the interlocutors switch roles between the clauses. We conclude that even if not very numerous (in written discourse), modally subordinated imperatives are a class of imperative sentences allowing for initial clitic clusters.

4.3. Instructions

The final discourse environment in which we found imperative clauses with an ICC is what we dub instructions (30). A common example of such texts are cooking recipes (our dataset includes one such example):

| (30) | a. | Stvari na mizo. Pisala v roke. Slovarje pred nos. Razgrnite tekst. Poiščite slovnične strukture. | |||||||

| Jih | podčrta-j-te | in | izpiš-i-te. | ||||||

| underline-imp-2pl | and | write out-imp-2pl | |||||||

| “Things on the desk. Pens in hand. The dictionaries under your noses. Open the text. Find grammatical structures. Underline them, and write them out.” | |||||||||

| b. | Meditacija s spominjanjem: vzemite si nekaj trenutkov zase. Zamižite in v mislih zajadrajte v najljubši kraj s potovanja. | ||||||||

| Si | priklič-i-te | tamkajšnje | vonjave, | zvok, | barve | in | občutja. | ||

| recall-imp-2pl | thereby | smells | sound | colors | and | feelings. | |||

| “Meditation with remembering: take a couple of moments for yourself. Close your eyes and in your mind sail into your favourite place from the trip. Recall the smells, sound, colors and feelings you had there.” | |||||||||

We argue that instructions belong to a wider category of narratives, i.e., we take instructions to be narratives composed of sentences in the imperative mood. Instructions clearly fulfill the criteria for narration (see Section 2.2); in fact, they are used as examples of narrative discourse in Hobbs (1978). In particular, note that the textual order matches the temporal order. Furthermore, if instructions are indeed a subspecies of narratives, we expect them to license telescoping (see Section 2.2). This indeed turns out to be the case. However, as the small set of ICC-containing instructions we found in the corpora contains no examples of universal quantification, we can only provide a constructed example:

| (31) | Negovanje konjev ni zelo pomembno le za njihov izgled, temveč pripomore tudi h gradnji čustvene vezi med konjem in jezdecem. Zato se posvetite vsakemu konju posebej. Očistite mu kopita. Preglejte njegovo dlako. | ||

| Ga | skrtač-i-te. | … | |

| brush-imp-2pl | |||

| “Grooming horses is not only important for their appearance, but also contributes toward building an emotional bond between the horse and the rider. Therefore, take the time for each and every horse. Pick its hooves. Inspect its coat. Brush it. …” | |||

Returning to the corpus examples, note that none of the ICC sentences we found in the corpus was the first step of the instruction. Indeed, we judge that beginning an instruction with an ICC sentence is ungrammatical. For example, one cannot rework (30b) into (32).

| (32) | Meditacija s spominjanjem: | *si | vzem-i-te | nekaj | trenutkov | zase. |

| take-imp-2.pl | several | moments | for yourself | |||

| “Meditation with remembering: take a couple of moments for yourself.” | ||||||

Finally, note that the temporal sequence of instruction steps can be interrupted by an elaboration of a step. (Elaboration is one of the coherence relations recognized by Coherence Theory). Our corpus data contains one example of an ICC elaboration of the previous imperative sentence. In (33), the directive to magnify the photo elaborates on the preceding imperative by telling the addressee how they could observe it better.

| (33) | Poglej bolje. | ||

| Si | slik-ico | poveča-j. | |

| photo-dim | magnify-imp.2sg | ||

| “Observe better. Magnify the photo.” | |||

Summing up, our corpus study shows that ICCs are not ungrammatical in Slovene imperative sentences. Additionally, the categories of ICC sentences established in this section—discourse particles, modal subordination and instructions—indicate that, at least in imperatives, the distribution of ICCs is governed by discourse-related factors.

5. Discussion

ICCs in Slovene imperatives have been discussed by Milojević Sheppard and Golden (2000, 2002) and Rus (2005). However, these analyses were based on the erroneous assumption that ICCs in (matrix) imperatives are always ungrammatical. It is therefore not surprising that Milojević Sheppard and Golden (2002), after attempting to apply the theories of Rivero and Terzi (1995) and Han (1998) to Slovene, conclude by stating that “the question of what makes the sentence-initial Clitic—Imperative Verb order unacceptable remains unsolved and merits further research.”13 More generally, given the conclusion from Section 4 that the distribution of ICCs in Slovene imperatives is governed by discourse-related factors, any analysis that attempts to explain the placement of the clitic clusters based only on morphosyntactic properties of the verbal system is destined to fail.

In broad strokes, the main idea behind our analysis is that while ICCs seem to be licensed in a heterogeneous set of discourse environments, these environments have a common denominator: they all require reference to some preceding discourse material. We assume that this discourse material, or perhaps an anaphoric reference to this material, is covertly integrated into the LF of an ICC sentence as a specifier of the topmost functional head—typically CP or, assuming a split CP, some high, discourse-related functional projection. Under the standard assumption that the clitic cluster is adjoined to C° (Golden & Sheppard, 2000) and obligatorily preceded by a specifier, the clitic cluster, which occupies the sentence-second position in the usual situation of the overt specifier of CP, will then occupy the sentence-initial position when the specifier is covert. Note, however, that the analysis of instructions will suggest that the topmost head is not always C°, i.e., that instructions may be composed of impoverished clauses and that the clitic cluster appears in the highest head of the clause, whether this is C° or some other head.

We emphasize that we do not aim to explain why ICCs may arise in Slovene, as opposed to almost all other Wackernagel languages. For concreteness, we subscribe to the standard view that this is so because “Slovene clitics have the option of being proclitic” (Golden, 2003, p. 214).14 The idea is that proclitics, which lean on the following phonological material, impose no requirements on the preceding phonological context, thereby allowing the preceding syntactic constituent to be covert.15 However, nothing in our analysis hinges on this assumption. Our analysis is compatible with any mechanism, syntactic or phonological, which allows the clitic cluster, standardly assumed to be adjoined to C° (Golden & Sheppard, 2000), to overtly occur sentence-initially. Our goal is more modest and limited to accounting for the corpus data presented in Section 4. We only attempt to explain the distribution of ICCs in Slovene imperatives rather than what makes Slovene have ICCs at all.

That said, our analysis does have a goal above and beyond accounting for the corpus data. We wish to emphasize that it supports the view on the syntax–semantics interface held by Ludlow and Živanović (2022) and Živanović and Ludlow (2023), presented in Section 2.3. Zero Interface and its extension into the realm of discourse predict an even tighter correlation between syntactic and semantic/pragmatic phenomena as is usually envisioned. Crucially for our discussion, in mainstream semantic theories discourse, information is accessed by semantics through the model-theoretic representation of the context, carrying no repercussions for syntax. In Zero Interface, however, any discourse material contributing to the meaning of a linguistic expression must be integrated into the LF. Of course, whether the integration of certain discourse material into the LF carries visible consequences for overt syntax is a matter resolved by a conspiracy of various phenomena. In this paper, we claim that ICCs in Slovene imperatives indeed arise via such a conspiracy. On the one hand, Slovene allows the clitic cluster to occur clause-initially (for reasons that are not investigated in this paper, though we have hinted that the culprit might be the proclitic nature of Slovene Wackernagel clitics). On the other hand, certain discursive situations compatible with the directive force emanating from imperative sentences require reference to the preceding discourse material. In case this reference is covert, it results in a clitic cluster following a covert initial phrase, yielding a clause-initial clitic cluster in overt syntax.

We now turn to individual ICC categories, with the aim of showing that each of them, in fact, requires reference to some preceding discourse material. We start with modally subordinated imperatives in Section 5.1, because the discussion of discourse particles in Section 5.2 relies on the analysis of modally subordinated imperatives, and conclude with Section 5.3 on instructions.

5.1. Modally Subordinated Imperatives

We arrive at the LF of modally subordinated ICC imperatives by using the basic structure of modal subordination exemplified by (12) in Section 2.3 and adding the standard assumption that the clitic (cluster) is located in C° (Golden & Sheppard, 2000). C° immediately follows the covert conditional, which gives rise to the overt clause-initial position of the cluster.

| (34) |  |

In (34), we used a corpus example where the ICC and preceding sentence were linked by ellipsis points. In such a case, the accommodated restrictor is most likely a verbatim copy of the preceding sentence. However, as mentioned in Section 2.1, the restrictor may be arrived at by various kinds of inferential reasoning—indeed, this is one of the hallmarks of modal subordination. The exact form of the restrictor is thus uncertain, so (35) shows merely one possibility for each of the modally subordinated imperatives from (29); note especially (35d), which requires the most reasoning. (We only provide the English translations, as the exact form of the original is irrelevant here.)

| (35) | a. | |

| b. | ||

| c. | ||

| d. |

5.2. Discourse Particles

Our analysis of ICC sentences involving a discourse particle is essentially the same as the analysis of modally subordinated imperatives: covert discourse material in the specifier of CP gives rise to the overtly clause-initial clitic cluster. Actually, most of the ICC sentences involving a discourse particle found in the corpus are modally subordinated. Remember that the crucial evidence for the modal subordination is that the given directives should not be taken as unconditional, but pertaining to a specific restriction on the domain of possible worlds. This turns out to be the case for the sentences with ‘pa’ illustrated in (24) and for all sentences containing particle ‘pač’. In (36) and (37), we show possible covert conditionals in the function of the accomodated modal restrictor for the corpus examples in (24) and (26) containing ‘pa’ and ‘pač’, respectively (as with the example at the end of the previous section, the final subexample of each batch seems to require the most reasoning for arriving at the restrictor). For example, in (36b), we are not directed to stop planting six weeks before the first frost, generally, but only if we followed the advice to plant in autumn. In fact, if the directive was general, the discourse would not make logical sense due to a failed presupposition: we cannot stop planting if we are not planting. (Notice the similarity of this exceptionally licensed presupposition to the exceptional discourse anaphoric relations, the hallmark of modal subordination.)

| (36) | a. | That you don’t have time for such ceremonies, you say? |

| b. | You may plant the entire autumn, if the temperatures are high enough. | |

| c. | So don’t let the current losses

make you refrain from investing, but stick to your investment plan or

gradually put even more money into the stock market. This way, you will

not cry over a missed opportunity in a couple of years. | |

| (37) | a. | For cycling, the (head)wind speeds of 20 to 30 kilometers per

hour can already be disturbing, but this does not mean that one cannot

pedal. |

| b. | As parents, we should control ourselves and take enough time, so that we

are not nervous and, for example, due to lack of time, intrude into the

independence of the children. |

Unlike the examples with ‘pa’ discussed above, ICC sentences containing the particle ‘pa’ shown in (25) do not involve modal subordination. The directives expressed in (25) are not conditional, but merely adverse to some proposition expressed (or implied) by the preceding linguistic context. These sentences thus cannot receive the same semantic analysis. However, the syntactic analysis, and thus the reason for the appearance of an ICC, remains essentially the same: we assume that these sentences contain a covert embedded clause (38). That this is a sensible analysis is confirmed by the fact that the sentences can be paraphrased using an overt embedded clause introduced by connective ‘čeprav’ “although”. Note that the content of ‘čeprav’-clause might need to be inferred, same as with the restrictor in the modally subordinated imperatives above. Another interesting detail (which we leave to further research) is that when ‘čeprav’-clause is overt, the sentences are only grammatical without ‘pa’.

| (38) | a. | |

| “ | ||

| b. | ||

| “ |

Summing up, our (syntactic) analysis of ICCs involving discourse particles is the same as the analysis of modally subordinated ICC sentences: the overtly initial clitic cluster is, in fact, preceded by a silent embedded clause. Finally, note that our analysis is not unique in assuming that sentences may contain covert discourse material. For example, Giorgi (2016) in her analysis of Italian surprise questions introduces a (dis)course head containing ‘ma’ “but” connecting two parts of the discourse. In particular, the specifier of this head hosts “the expected, but silent, portion of the construction” (Giorgi, 2016, p. 8).16 Giorgi (2023) furthermore argues for a distributed pragmatics, demonstrating “that the syntactic explanation of complex phenomena can now start to include units beyond a single sentence” (Giorgi, 2023, p. 124)—precisely what we do in our analysis to account for the distribution of ICCs in Slovene imperatives.

5.3. Instructions

The core idea behind our analysis of ICC sentences appearing in instructions is the same as for modally subordinated imperatives and for imperatives containing discourse particles: the overtly clause-initial clitic cluster is preceded by covert discourse material. The details, however, are different. In Section 4.3, we have shown that instructions belong into a wider class of narratives. We therefore apply the account of narratives presented in Section 2.3 to instructions.

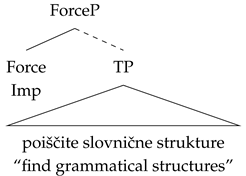

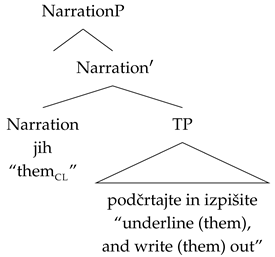

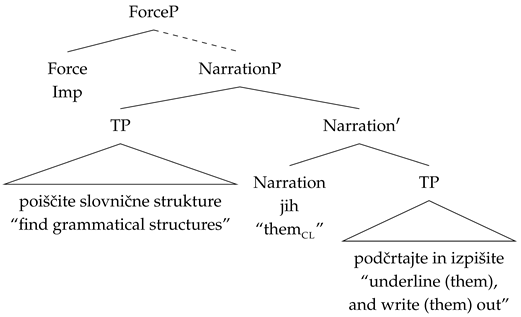

Below, we provide a discourse LF for the sequence of instruction steps in (39); the sentences belong to the corpus example (30a), but for simplicity, we are pretending that they are starting the instruction. Individually, the two sentences receive the LFs shown in (40). Although the sentences seem rather similar at first sight, their LFs differ in important respects. First, only (40a) carries a marker of imperative force.17 This is so because we assume that the directive force applies to the instruction as a whole, not to separate imperative sentences—it is not practical or logical to only follow some selected steps of an instruction. Second, only (40b) contains the Narration head (and so would all further imperative sentences in the instruction); the first sentence does not contain it as it is starting the instruction and therefore is not a narrative continuation of the preceding discourse. The two LFs are eventually integrated (post-syntactically, by mechanisms used for inferential reasoning) into the discourse LF shown in (41) (cf. 13), but for our analysis, the crucial aspect of the LFs shown below is the location of NarrationP.

| (39) | Poiščite slovnične strukture. Jih podčrtajte in izpišite. |

| “Find grammatical structures. Underline them, and write them out.” |

| (40) | a. |  | b. |  |

| (41) |  |

As shown by (40b), Narration heads the entire LF of a non-initial instruction clause. The covert discourse material (or a some marker triggering the integration of this material) is located in the specifier of Narration in (40b) (shown as an empty branch), which leaves the clitics residing in the Narration head in overtly clause-initial position. Given this location of the clitic cluster, we have to of course relax our initial assumption that the clitic cluster is located in C° and replace it with the assumption that it resides in whatever syntactic head turns out to be the highest; such an analysis supports the idea that clitics move as far as they can (Bošković, 2001; Franks, 2010; Marušič, 2008), rather than having a fixed (displaced) location in C°. Finally, note that as we place the ICC in the Narration head, and this head only occurs in the LF of the non-first sentences, we correctly predict the observation from Section 4.3 that only non-first sentences of an instruction may contain an ICC.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented corpus data showing that, contrary to what is claimed in most of the previous literature, initial clitic clusters (ICCs) in Slovene imperatives are not ungrammatical. Our data thus speaks against a syntactic uniqueness of Slovene imperatives, contrary to what is claimed by Milojević Sheppard and Golden (2002). We have categorized ICC imperatives into three classes: modally subordinated imperatives, imperatives containing the adversative or the concessive particle, and imperatives occuring as a step in an instruction. The categorization shows that the distribution of ICCs in Slovene imperatives is ultimately governed by discourse. We speculate that ICCs in imperatives are uncommon in comparison to other sentence types because less discourse situations allowing for ICCs are compatible with imperatives than with assertions and questions.

At first sight, the positioning of the clitic cluster seems to be a syntactic affair, perhaps with phonology playing a minor role as well, but given the classification of ICC imperatives presented in the paper, the conclusion that there is a discourse component to the ICC phenomenon is inescapable. Interestingly, however, despite being licensed by a heterogeneous set of discourse situations, it seems that the ultimate source of ICCs (at least in imperatives) is one and only one: ICCs arise when the second-position clitic cluster is preceded by the covert discourse material required by coherence relations—a conclusion that arguably vindicates the view that all discursive information must be represented in syntax, even if covertly.

Our paper raises additional questions about the status of clitics in Slovene and Slavic in general. One question is whether the analysis can be broadened to all Slovene sentence types. Specifically, do all of the discourse situations our categorization relies on allow for ICCs in assertions and questions as well? Are there any additional discourse situations that allow them in other moods? Moreover, the tentative idea that the availability of ICCs is due to the proclitic nature of Slovene Wackernagel clitics should be further explored. According to Lenertová (2004), informal spoken Czech allows for ICCs. Further research can look into whether our analysis can be extended to Czech as well. Lastly, we note that our analysis is viable for the Slovene dialects that exhibit stable Wackernagel clitic position. This excludes the western Romance-adjacent dialects that allow first-position clitics more freely (Zuljan Kumar, 2022). Additional syntactic discussions of Slovene dialects are desirable to detect possible fine-grained differences between the dialects.

The future research will undoubtedly reshape our analysis of Slovene ICC imperatives. However, the novel data will remain: initial clitic clusters may occur in Slovene imperatives, and their distribution is crucially governed by discourse.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Ž. and E.Š.; methodology, S.Ž. and E.Š.; software, S.Ž.; validation S.Ž. and E.Š.; formal analysis, S.Ž. and E.Š.; investigation, S.Ž.; resources, S.Ž. and E.Š.; data curation S.Ž. and E.Š.; writing—original draft preparation S.Ž. and E.Š.; writing—review and editing S.Ž. and E.Š.; visualization S.Ž.; supervision S.Ž. and E.Š.; project administration S.Ž. and E.Š.; funding acquisition E.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Slovenian Research and Inovation Agency (ARIS, grants P6-0382, N6-0314).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Zenodo at DOI 10.5281/zenodo.16421059.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers and the audience of SinFonIJA 17 for their insightful comments. All remaining errors are ours.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Abbreviations

| 1 | first person | CC | clitic cluster | pl | plural |

| 1P | first position | dat | dative | prs | present tense |

| 2 | second person | dim | diminutive | ptcp | participle |

| 3 | third person | ICC | initial clitic cluster | refl | reflexive |

| acc | accusative | imp | imperative | sg | singular |

| aux | auxiliary verb | m | masculine | tv | theme vowel |

| cl | clitic | neg | negation |

Notes

| 1 | We use the term ‘clitic cluster’ to refer to a single clitic in the Wackernagel position, as well. To the best of our knowledge, the number of clitics in a cluster has no effect on its position, even if that number is one. |

| 2 | Modern incarnations of this analysis usually deploy dynamic semantics. |

| 3 | Symbols ◊ and □ stand for the possibility and necessity operators, respectively. |

| 4 | We follow Lascarides and Asher (1993) in using the term “Narration”, as we find it more transparent than (the somewhat wider) “Occasion”, used by Hobbs (1978) and Kehler (2002). |

| 5 | Temporal progression is not the only hallmark of narratives, which seem to also require that the events “typically co-occur in a relatively predictable order” (Kehler, 2002, p. 22), enabling the hearer to fill in the gaps between the events mentioned in the narrative; this is why narratives are sometimes also called scripts; see also Roberts (1989). |

| 6 | Truncated structures were originally proposed to account for certain features of child language (Rizzi, 1993) and abbreviated registers (Haegeman, 1997), but were later adopted for analysis of regular adult language as well, see Haegeman (2012, p. 186) and the references therein. Note that imperatives have also received truncation analyses (e.g., Cardinaletti, 2009; Jensen, 2007). However, we do not subscribe to these, as they seem to primarily rest on the assumption that imperatives cannot be embedded, which has been since shown to be incorrect, see Stegovec and Kaufmann (2015, p. 641) for a list of literature reporting embedded imperatives in various languages. We discuss embeddability of imperatives in Štarkl and Živanović (2025). |

| 7 | Gigafida 2.0: Korpus pisne standardne slovenščine, viri.cjvt.si/gigafida, accessed on 16 May 2025. |

| 8 | We included the corpus Janes, which features mostly non-proof-read, colloquial texts, because we suspected that such texts, being presumably more closely related to the spoken language than proof-read texts prevalent in Gigafida, might present a greater diversity of environments licensing ICCs. However, as we will see in Section 4, it turned out that both corpora contained instances of ICC sentences from every category, and in similar proportions, which is why we treat the results as a single homogeneous group of data. We have decided against using the only available spoken corpus for Slovene, Gos (Zwitter Vitez et al., 2021), because of its small size relative to the used corpora. The Slovene meta corpus metaFida (Erjavec, 2023) combining all these and further corpora was not yet available when we carried out the research. |

| 9 | Indeed, searching for [word="Ti|Te"] … yields 3082 hits, and an inspection of a random sample of 100 sentences confirmed that the imperative clauses contain only non-clitic pronouns (and thus present no counter-examples to Principle B). |

| 10 | In principle, the context should be available in the corpus itself. However, it turns out this is not always the case. For example, the relevant context in social media posts can be owned by an author whose posts are inaccessible. The list header is typically absent from the corpus, either because it is an isolated word ignored by the parser, or because it is provided in the form of an image inaccessible to the parser. |

| 11 | Slovene is remarkably dialectally diverse for its size and number of speakers (see Škofic et al., 2016, Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji). However, syntactic studies are rare within Slovene dialectology. Zuljan Kumar (2022) starts her discussion of dialectal syntax with the western, Romance-adjacent varieties precisely because they exhibit substantial deviations from the rest of Slovene dialects (and standard Slovene). These deviations include clitic position and word-order. |

| 12 | We do not claim that CCs in modally subordinated imperatives (and other ICC categories described in this section) must always be clause-initial. In fact, they most often appear in the usual 2nd position. Yet, ICCs are not ruled out, unlike in sentences which fall into none of the categories described in this section. |

| 13 | According to Rivero and Terzi (1995), languages differ with respect to whether imperative verbs have (Class I) or lack (Class II) a distinctive syntax. They propose that in Class I (which includes Romance languages), the root C has a strong V-feature encoding logical mood, which attracts the imperative verbs to C. The proposal explains the unique position of imperative verbs with respect to pronominal clitics and the unavailability of negated imperatives in Class I languages. In Class II (which includes Wackernagel languages), the root C has no strong-V feature. Therefore, imperative verbs distribute like other verbs and may be negated. Slovene belongs to Class II because it is a Wackernagel language and allows negative imperatives. However, then its imperative verbs should also exhibit the same position with respect to pronominal clitics as other verbs. Erroneously assuming that this is not the case, the previous accounts of Slovene imperatives (Milojević Sheppard & Golden, 2000, 2002; Rus, 2005) arrive at a paradoxical situation they are unable to explain. The data presented in this paper thus immediately alleviates the exceptionality of Slovene in regards to Rivero and Terzi’s (1995) classification, with Slovene now neatly falling into Class II. |

| 14 | Toporišič (2000, p. 112) states that Slovene clitics may be both proclitic and enclitic because a clitic cluster may both begin and end a sentence (or, more generally, a prosodic phrase). However, Orešnik (1984) argues that Slovene clitics are primarily proclitics. For example, Slovene allows for fragment answers consisting solely of a clitic cluster. In such a case, Slovene deploys a phonological repair strategy which stresses the final syllable of the cluster. This implies that the non-stressed clitics function as proclitics. Orešnik’s (1984) view has been recently supported by a psycholinguistic experiment carried out by Tabachnick et al. (in press). The experiment shows that in a phonological environment which could in principle feature both a proclitic and an enclitic, clitics behave as proclitics. |

| 15 | One can also imagine a language allowing for a covert initial syntactic constituent preceding a clitic cluster consisting of enclitics. This would be the case if the language featured a phonological repair strategy similar to the Slovene strategy mentioned in Note 14 but stressing the initial syllable of the cluster. Colloquial Czech, which exhibits ICCs (Lenertová, 2004), seems to be such a language. We thank Martin Březina for collecting the judgments of 8 Czech speakers on the placement of stress in Czech ICCs, but emphasize that the issue requires further research. One interesting question is whether the repair strategy is related to the default stress placement. |

| 16 | In the interest of full disclosure, (Giorgi, 2016, p. 9) then goes on to claim that when the discourse head is “silent, the adversative meaning must be uniquely supplied by the context.” However, following the Zero Interface idea of Živanović and Ludlow (2023), we would rather assume that even the silent discourse head (presumably encoding a coherence relation) occurs in the syntactic structure, alongside its silent specifier. |

| 17 | The details of how the imperative force is encoded in LF are irrelevant for the present discussion. We only assume that it is explicitly encoded on a Force head for simplicity. For an exposition of our view on the structure of imperative clauses, see Štarkl and Živanović (2025). |

References

- Beghelli, F., & Stowell, T. (1997). Distributivity and negation: The syntax of each and every. In A. Szabolcsi (Ed.), Ways of scope taking (Vol. 65, pp. 71–107). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bošković, Ž. (2001). On the nature on the syntax–phonology interface: Cliticization and related phenomena. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, A. (2009). On a (wh-)moved topic in Italian, compared to Germanic. In Advances in comparative germanic syntax (pp. 3–40). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dvořák, B. (2005). Sloweniche Imperative un ihre Einbettung. Philologie im Netz, 33, 36–73. [Google Scholar]

- Erjavec, T. (2023). Corpus of combined Slovenian corpora metaFida 1.0 (Slovenian language resource repository CLARIN.SI). CLARIN.SI. [Google Scholar]

- Erjavec, T., Ljubešić, N., & Fišer, D. (2018). Korpus slovenskih spletnih uporabniških vsebin Janes. In D. Fišer (Ed.), Viri, orodja in metode za analizo spletne slovenščine (pp. 16–43). Ljubljana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, S. (2010). Clitics in Slavic. Glossos, 10. Available online: https://slaviccenters.duke.edu/sites/slaviccenters.duke.edu/files/media_items_files/10franks.original.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Giorgi, A. (2016). On the temporal interpretation of certain surprise questions. SpringerPlus, 5, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi, A. (2023). Pragmatics in the Minimalist framework. Evolutionary Linguistic Theory, 5(2), 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, M. (2003). Clitic placement and clitic climbing in Slovenian. STUF-Language Typology and Universals, 56(3), 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, M., & Sheppard, M. M. (2000). Slovene pronominal clitics. In F. Beukema, & M. den Dikken (Eds.), The clitic phenomena in European languages (Vol. 30, pp. 191–207). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Haegeman, L. (1997). Register variation, truncation, and subject omission in English and in French. English Language and Linguistics, 1(2), 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegeman, L. (2012). Adverbial clauses, main clause phenomena, and the composition of the left periphery. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.-H. (1998). The structure and interpretation of imperatives: Mood and force in universal grammar [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, I. (1988). The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. Garland Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, J. R. (1978). Why is discourse coherent? (Technical Note No. 176). SRI International. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, J. R. (1979). Coherence and coreference. Cognitive Science, 3, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B. (2007). In favour of a truncated imperative clause structure: Evidence from adverbs. Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax, 80, 163–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, H. (1981). A theory of truth and semantic representation. In J. Groenendijk, T. Janssen, & M. Stokhof (Eds.), Formal methods in the study of language: Part 1 (pp. 277–322). Mathematisch Centrum. [Google Scholar]

- Kehler, A. (2002). Coherence, reference, and the theory of grammar. CLSI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, A. (1996). A data-driven methodology for motivating a set of coherence relations [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Edinburgh.

- Lascarides, A., & Asher, N. (1993). Temporal interpretation, discourse relations, and commonsense entailment. Linguistics and Philosophy, 16, 437–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenertová, D. (2004). Czech pronominal clitics. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 12(1/2), 135–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, P., & Živanović, S. (2022). Language, form, and logic. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marušič, F. (2008). Slovenian clitics have no unique syntactic position. Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics, 16, 266–281. [Google Scholar]

- Milojević Sheppard, M., & Golden, M. (2000). Imperatives, negation and clitics in Slovene. SAZU. [Google Scholar]

- Milojević Sheppard, M., & Golden, M. (2002). (Negative) imperatives in Slovene. In S. Barbiers, F. Beukema, & W. van der Wurff (Eds.), Modality and its interaction with the verbal system. Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today 47. [Google Scholar]

- Orešnik, J. (1984). Slovenske breznaglasnice se vedejo predvsem kot proklitike. Jezik in slovstvo, 29(4), 129. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, M. L., & Terzi, A. (1995). Imperatives, V-movement and logical mood. Journal of Linguistics, 31(2), 301–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, L. (1993). Some notes on linguistic theory and language development: The case of root infinitives. Language Acquisition, 3(4), 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In L. Haegeman (Ed.), Elements of grammar (pp. 281–337). Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C. (1989). Modal subordination and pronominal anaphora in discourse. Linguistics and Philosophy, 12(6), 683–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C. (2021). Modal Subordination: It would eat you first! In D. Gutzmann (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to semantics. Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rus, D. (2005). Slovenian embedded imperatives. In C. Brandstetter, & D. Rus (Eds.), Georgetown working papers in theoretical linguistics (Vol. 4, pp. 153–183). Georgetown University. [Google Scholar]

- Stegovec, A., & Kaufmann, M. (2015). Slovenian imperatives. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 19, 641–658. [Google Scholar]

- Stojnić, U. (2021). Context and coherence: The logic and grammar of prominence. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Škofic, J., Gostenčnik, J., Hazler, V., Horvat, M., Jakop, T., Ježovnik, J., Kenda-Jež, K., Nartnik, V., Smole, V., Šekli, M., & Kumar, D. Z. (2016). Slovenski lingvistični atlas 2. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Available online: https://fran.si/204/sla-slovenski-lingvisticni-atlas (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Štarkl, E., & Živanović, S. (2025). Revisiting Slovene embedded imperatives: Insights from the particle daj. In FDSL 2024. Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, G., Marušič, F., & Žaucer, R. (in press). Slovenian clitics prefer to cliticize to the right. Journal of Slavic Linguistics.

- Toporišič, J. (2000). Slovenska slovnica. Obzorja. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, B. L., Stone, M., Joshi, A. K., & Knott, A. (2003). Anaphora and discourse structure. Computational Linguistics, 29, 545–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F., & Gibson, E. (2006). Coherence in natural language. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, F., Gibson, E., & Desmet, T. (2004). Discourse coherence and pronoun resolution. Language and Cognitive Processes, 19(6), 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuljan Kumar, D. (2022). Skladnja nadiškega in briškega narečja. Založba ZRC SAZU. [Google Scholar]

- Zwitter Vitez, A., Zemljarič Miklavčič, J., Krek, S., Stabej, M., & Erjavec, T. (2021). Spoken corpus Gos 1.1. (Slovenian language resource repository CLARIN.SI). CLARIN.SI. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11356/1438 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Živanović, S., & Ludlow, P. (2023). The syntax of prominence. Croatian Journal of Philosophy, 23(69), 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živanović, S., & Štarkl, E. (2025). Initial clitic clusters in Slovene imperative clauses: Dataset. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/16421059 (accessed on 25 August 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).