Abstract

Recent studies have greatly furthered our understanding of the Southern Bantu languages, but questions about the internal relationships of the Southern Bantu language subgroups and the validity of the clade as a whole still remain. This study attempts to reconstruct the consonant inventory of one proposed genetic clade, that of Tsonga-Copi (S50–S60). Using published dictionaries and reference works for each language of the subgrouping, a corpus of cognate vocabulary was assembled. Each term was then matched, where possible, to a reconstruction in the Bantu Lexical Reconstructions 3 (BLR3) database. Sound correspondences were identified and used to reconstruct the consonant inventory of Proto-Tsonga-Copi. In addition to the discovery of several typologically unusual sound changes, the results of this study also lend support to existing and developing hypotheses about both the internal relationships of Southern Bantu clades, as well as the nature of language contact in (pre)historic Southern Africa, particularly the influence of Khoisan and other Bantu languages.

1. Introduction

The Southern Bantu language group consists of ~80 living languages (Maho, 2009) divided among six subgroups: Shona (S10), Venda (S20), Sotho-Tswana (S30), Nguni (S40), Tsonga (S50), and Copi (S60). It has long been a question of how these groups within Southern Bantu are related to one another, as well as whether Southern Bantu as a whole constitutes a valid genetic language family. Reconstructions of Proto-Bantu (PB) (Meinhof, 1899; Meeussen, 1967; Guthrie, 1971) based on lexical and phonological comparison generally noted the high degree of similarity shared by the six clades but did not reconstruct lower-order protolanguages such as Proto-Southern Bantu (PSB) itself. This task was attempted by Van der Spuy (1989), whose research unfortunately lacked any representation of the Copi clade. Van der Spuy’s study (summarized in Van der Spuy, 1990) yielded a Proto-Southern Bantu which could not clearly be distinguished from the earlier reconstructions of Proto-Bantu, a finding which was supported by later comparative work by Janson (1991–1992). This casts doubt on the validity of Southern Bantu as a sufficiently distinct unit from (late) Proto-Bantu, but of course does not discount the possibility that lower-order groupings indeed represent valid genetic clades.

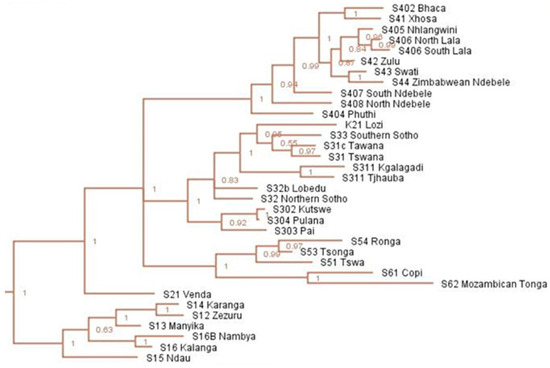

Bantu classification has also been attempted through lexicostatistic studies (Ehret, 1972; Borland, 1986; Bastin et al., 1999) which compare basic vocabulary that is supposed to be more resistant to borrowing. The former two studies only examined Southern Bantu, effectively presupposing it as a valid clade. However, Bastin et al. (1999) incorporated data from 450 Bantu languages, and its results did indeed point to Southern Bantu as a valid internal clade. More recent Bantu classification studies (Currie et al., 2013; Grollemund et al., 2015; Koile et al., 2022) use Bayesian phylogenetic models, which improve upon lexicostatistic models by focusing on shared innovations rather than overall similarity to establish genetic relationships. These studies were all conducted using over 400 Bantu languages, and each again pointed to the validity of Southern Bantu as a clade. When it comes to the internal classification of Southern Bantu, however, these studies suffer from a poverty of data. Currie et al. (2013) include 23 Southern Bantu languages, while Grollemund et al. (2015) and Koile et al. (2022) include only 11, and none of these studies include any Copi languages.

The newest phylogenetic study of Bantu, Gunnink et al. (2025), incorporates ~120 Bantu languages, 34 of these being Southern Bantu, including both languages of the Copi group. As in their prior studies (Sengupta et al., 2021; Gunnink et al., 2022), the authors employ Bayesian models with lists of approximately 100 semantically controlled lexemes to determine the overall phylogeny of the languages sampled. The result of this study both supports the existence of Southern Bantu as a clade and groups the Tsonga (S50) and Copi (S60) clusters together as a distinct subclade within Southern Bantu to a high degree of probability. This implies that the languages of these two groups share a single common ancestor, Proto-Tsonga-Copi (PTC). This ancestor should theoretically be reconstructable using comparative methodology.

This study investigates the phonological relationships between the Tsonga (or Tswa-Ronga) and Copi (or Copi-Tonga) clades, and attempts to reconstruct the consonant inventory of their nearest ancestor, Proto-Tsonga-Copi. First, an account of the synchronic phonological inventories is given with a comparison to Meeussen’s (1967) reconstruction of Proto-Bantu. Afterwards, the specific methodology of this particular study is elaborated on. Next, an account of the reflexes of each Proto-Bantu phoneme is given for the languages under consideration, along with discussion of the implications for the reconstruction of Proto-Tsonga-Copi. Finally, the reconstructed consonant inventory will be examined typologically, and notable findings and future avenues for research will be discussed.

It is important to note that the present study does not attempt to demonstrate the validity of Tsonga-Copi as a clade, though the implications of this study and the further research necessary to demonstrate the clade’s validity will be discussed later on. This work is principally a comparative phonological study much in the vein of Guthrie’s work, with a much narrower focus. While Guthrie’s (1971) comparative analysis is impressive, it is limited in usefulness for determining familial relationships and shared phonological innovations at a micro level. To illustrate, Guthrie’s phonological correspondences for S50 are based primarily on Tswa, for which he cites 152 lexemes. For Tsonga and Ronga, on the other hand, he cites 11 and 15 lexemes, respectively. From this data alone, it is hardly possible to identify any divergence within S50 languages. While S60 is comparatively better represented, with 100 Copi and 69 Tonga lexemes, there are only 31 reconstructed forms where Guthrie cites a lexeme in both S50 and S60. Van der Spuy’s comparative study also has its limits in usefulness, arbitrarily taking a single language from each Southern Bantu clade to be representative of the whole, in addition to the aforementioned omission of Copi data. The present study provides an abundance of data on all S50 and S60 languages, which allows lexemes in each language to be compared directly to their cognates in another, making it easier to tease apart dialectical divergence, loanwords, and other otherwise overlooked phenomena. Beyond that, this study integrates in its analysis of correspondences the results of decades of development in Bantu historical research which have occurred since Guthrie’s study. The result is an expanded understanding of the historical phonology of both S50 and S60, as well as a strong basis for which future comparative studies on the internal relationships of Southern Bantu languages can be conducted.

1.1. Tonga

The Tonga language (S62), also known as Gitonga or Guitonga, is spoken by approximately 327,000 speakers in the vicinity of Inhambane in Mozambique (Eberhard et al., 2022). The language should not be confused with the Tonga language of Zambia and Zimbabwe (M64) or the Tonga language of Malawi (N15), and so it is sometimes called Tonga of Inhambane or Mozambican Tonga to disambiguate. All sources consulted (Lanham, 1955; Amaral et al., 2007; Ngunga & Faquir, 2012) identify five dialects of Tonga: Gitonga gya Khogani/Khoga, Nyambe, Khumbana, Sewi, and Morrumbene/Rombe. All sources make use of the Khoga dialect, spoken on the coast surrounding Inhambane Bay, as a standard. Lanham (1955, p. v) also incorporates some words from Morrumbene, while noting that no great differences between the two occur. Lanham (1955, p. 109) further notes that Sewi, spoken within the city of Inhambane proper, has the largest number of Portuguese borrowings. Amaral et al. (2007, p. 109) suggest that Nyambe, spoken on the oceanic coast of the Jangamo district, is the most archaic dialect, but do not exemplify this. The consonant inventory given in Table 1 attempts to synthesize the consonant inventories reported by these three sources. In this and other inventories, labialization, palatalization, and prenasalization are not indicated, as they are assumed to reflect sequences of multiple phonemes. Phonemes given in parentheses are claimed to be loan phonemes, and clicks (which are loan phonemes in all S50 and S60 languages) are omitted entirely.

Table 1.

The consonant inventory of Tonga 1.

The Tonga consonant inventory shows four series of stops, those being voiceless, voiceless aspirated, voiced, and implosive. These series are largely paralleled in the affricates, with the exception of the implosives. Only the voiced stops and affricates can be prenasalized. A notable asymmetry is the lack of voiced and implosive velar stops. Lanham (1955) gives a phoneme /β/, which corresponds to both /β/ and /v’/ in Amaral et al. (2007). As will be discussed in Section 3.1 and Section 3.5, the distinction in Amaral et al. is etymological, and so Lanham’s description must reflect a dialectical merger of these phonemes.

1.2. Copi and Lenge

The Copi language (S61), often written Chopi or Cicopi, is spoken by around 1,100,000 speakers in Mozambique. These speakers primarily live in a strip along the coast of Gaza province (Eberhard et al., 2022). Both Dos Santos (1949) and Bailey (1976) divide Copi dialects into three groups: Southern, Central, and Northern. Dos Santos (1949, p. 9) claims that the Northern group shows the greatest number of dialectical differences relative to the Central group, which he takes to be the “pure” Copi. He further notes that the Southern dialects show the greatest amount of hybridism with Changana, due to the bilingualism of the people living there. This observation is echoed by Bailey (1976, p. 1), who adds that women in the southernmost regions, until recently, spoke the Lenge variety of Copi, which was highly divergent and influenced by Changana, while the men of the region principally spoke Changana. In addition to Changana, Bailey describes a high level of bilingualism in both Tswa and Tonga as well, and Eberhard et al. (2022) report that in modern times, approximately 50% of Copi speakers speak Tswa.

The modern dialectical picture is not entirely clear. Ngunga and Faquir (2012) and Eberhard et al. (2022) cite six dialects: Ndonge/Ndonje, Lenge/Lengue, Tonga (distinct from the Tonga language detailed above), Lambwe, Khambani, and Copi. Ngunga and Faquir use the latter of these as their reference variant, while noting the need for in-depth dialectological studies to verify the existence and degree of divergence of these dialects. Maho (2009) treats Lenge as a distinct language in his classification of Bantu languages, also marking the variety as possibly extinct. Hammarström (2019) instead lists Lenge as a dialect of Copi.

Table 2 attempts to synthesize the consonant inventories proposed in the various reference sources into a single overview. The information is drawn principally from Dos Santos (1949) and Bailey (1976), of which neither attempts to represent a single variety of Copi. Smyth and Matthews (1902) do not include particularly detailed phonetic descriptions in their dictionary of Lenge, but the data is nevertheless worthy of particular note due to its treatment of a singular language variety and the unclear status of Lenge as a dialect or a separate language. For that reason, phonemes which appear in Lenge are given in bold, with the phoneme /rɦ/ only reported for Lenge further italicized. In any case, the inventory below should not be accepted without caution; Bailey (1995, p. 138) notes the “considerable” ideolectical and regional variation that still exists among Copi speakers, and the present study would benefit greatly from modern fieldwork data on Copi, as well as all of the languages under consideration. Nevertheless, the following paragraphs attempt to discuss and balance the various authors’ reports and their implications for the overall phonology of Copi.

Table 2.

The consonant inventory of Copi.

A clear difference between the consonant inventories of Copi and Tonga is in the number of affricates. Copi has both labiodental and alveolar affricates, as does Tonga, but also has a series of affricates described as “labioalveolar” (Bailey, 1976, p. 14) and a postalveolar series. The former of these is generally notated in complexes which use the symbols for the retroflex sibilants <ʂ> and <ʐ>. This is simply notational, and these sounds are not necessarily phonetically retroflex.

Copi shows the same four-way stop and affricate contrast as Tonga. Voiced stops and affricates can be prenasalized, and these prenasalized obstruents can also be aspirated. Bailey (1995, p. 146) states that most lexemes containing voiced aspirates are clear borrowings from Tsonga, but some appear to be native Copi words. In either case, he notes a large degree of dialectical variation in the realization of these words. Besides the voiced aspirates, Bailey also claims that aspirated nasals, an entire series of lateral affricates, and a postalveolar fricative /ʃ/ are present but exclusively confined to Tsonga borrowings.

When it comes to the phonetic nature of certain stops, the various sources consulted are not in agreement. Ngunga and Faquir (2012) include both a voiceless and voiced palatal stop in the consonant inventory, and cite [ca] ‘dawn’ and [ɟika] ‘diverge’ as examples. The former of these is given in Bailey (1995) as [tʃa] with an affricate, and the respective spellings tcha and djika in Dos Santos (1949) also suggest an affricate. As such, these phonemes will be spelled in this paper as affricates. The voiced aspirated affricate [tʃh] is not present in Ngunga and Faquir (2012), but is reported by Bailey (1976, 1995). Neither work cites many lexical examples, but the former gives [tʃhisa] ‘abort’, spelled in Dos Santos (1949) as tchisa, identical to the spelling of [tʃ]. It is therefore not possible to distinguish between [tʃ] and [tʃh] following Dos Santos, and so all instances will be cited as [tʃ].

Bailey (1976) does nevertheless report the existence of a palatal stop, which can optionally be implosive. The representation of this sound is not clear in Dos Santos (1949). Dos Santos’ dictionary contains two sections with ‘d’ sounds, the first being “palatal d” and the latter being “dental d”. Both of these are spelled <d>. This does not seem to overlap with the palatal stop distinction noted by Bailey. Bailey (1995) cites the lexemes [ɟa] ‘eat’ and [ɗuka] ‘try’, but these are both listed in Dos Santos (1949) under “palatal d”. Dos Santos spells these dia and duka, respectively, so it could be suggested that the sequence <di> indicates a palatal stop. Unfortunately, Bailey (1995) claims that the sequence [ɗj] exists and phonetically contrasts with [ɟ], and gives [ɗjanda] ‘egg’ as an example. This is listed in Dos Santos (1949) as a dialectical variant which is spelled dianda. Dos Santos is also not consistent in reflecting the phoneme Bailey identifies as [ɗ] as “palatal d”, with the lexeme [ɗaja] ‘kill’ given under “dental d” in Dos Santos (1949). Since it is unclear how to reflect the phoneme Dos Santos spells <d>, such entries will always be cited with [ɗ].

It is also worth noting that while Dos Santos’ orthography seems to consistently reflect the difference between [ɓ] and [b] (the former spelled <b> and the latter <bh>), the same cannot be said for [ɗ] and [d]. Ngunga and Faquir (2012) have the term [dula] ‘expensive’, which is spelled dula in Dos Santos (1949) and listed under “dental d”. Bailey (1976) has the term [dana] ‘call’, which Dos Santos spells dana and lists under “palatal d”. Dos Santos (1949) only spells two words with <dh>, both listed under “dental d”. These are dhani ‘species of tree from which bows are made’, and dhuti ‘hut’; neither of these are present in Ngunga and Faquir (2012) or Bailey (1976, 1995), so it cannot be made clear what contrast is spelled here.

One final bit of contention between sources has to do with the voiced labiodentals. Bailey (1976) lists both /bv/ and /v/ in the phonemic inventory, and gives /bvarula/ ‘tear’ and /va/ ‘be’ as examples. In Bailey (1995), /bv/ is no longer reported, but /ʋ/ is, with exemplary terms being /vuna/ ‘help’ and /ʋa/ ‘be’. Ngunga and Faquir (2012) again report a contrast of /v/ and /ʋ/, with /varula/ ‘tear’ and /ʋeka/ ‘put’ as examples. All of these words are spelled with initial <v> in Dos Santos (1949), with the exception of ‘tear’; this is cited with two spellings, bvarula and varula. All of this suggests two phonemes, /ʋ/ and /bv ~ v/, with the latter showing either free variation, dialectical variation, or a sound shift in progress. When Dos Santos spells <v>, this will be denoted as /ʋ/, but the potential for conflation with /v/ should be noted.

1.3. Tsonga and Changana

The Tsonga/Changana (S53) language is spoken natively by approximately 5,680,000 speakers in South Africa and Mozambique. Of these, 2,280,000 live in South Africa in the northeastern Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces, and 4,200,000 live in Mozambique in the northern parts of Gaza and Maputo provinces and the west of Inhambane province. The language is spoken by an additional 100,000 people living in Zimbabwe, where it is often called Shangani (Eberhard et al., 2022). The term Tsonga here refers to the South African standard of the language, which has a written form distinct from Changana, the Mozambican standard. Unsurprisingly, the Mozambican varieties have a large number of loans from Portuguese which are not found in South African Tsonga.

Teasing apart the picture of Tsonga/Changana and its dialects is difficult; to start, the term Tsonga is often used to refer not only to Changana but also to Ronga and Tswa as well. Descriptions of the various dialects therefore often appear to arbitrarily include or exclude certain varieties based on what is perceived to fall under the umbrella of a given language. Maho (2009) distinguishes eight dialects of Tsonga/Changana: Xiluleke, N’gwalungu, Hlave, Nkuna, Gwamba, Nhlanganu, Djonga/Jonga, and Bila. He lists Hlengwe as a distinct language, and incorporates Dzibi and Dzonga under Tswa and Konde, Ssonga, and Xonga under Ronga. Baumbach (1974, 1987) identifies four dialect clusters: the nucleus cluster, encompassing Changana, Nkuna, Gwambe, Hlave, and N’walungu; a peripheral dialect cluster with only Konde named, an intermediate cluster ‘A’ consisting of Luleke and Nhlanganu, and an intermediate cluster ‘B’ consisting of Xonga and Ssonga (with Ssonga omitted in his 1987 grammar). Both Sitoe (1996) and Ngunga and Faquir (2012) report five dialects of Changana: Hlanganu, Dzonga, N’walungu, Bila, and Hlengwe.

It is clear that there is substantial overlap between what is considered Tsonga, Ronga, or Tswa, and that within and between these groups there is a substantial degree of variation. As with the other languages under consideration in this study, this is compounded by the high levels of bilingualism among speakers. The consonant inventory for Tsonga in Table 3 draws primarily on the work of Baumbach (1987), whose data hails from the Nkuna and Gwamba dialects. Changana phonology and lexical forms come from the works of Sitoe (1996) and Ngunga and Faquir (2012), whose data derives mostly from the Dzonga dialect. For the most detailed account of the phonological differences between several of the Tsonga dialects, readers should consult Baumbach (1974).

Table 3.

The consonant inventory of Tsonga.

The consonant inventory of Tsonga has often been reported as massive, with Baumbach (1987) citing exactly 100 non-click consonantal phonemes. Part of this can be due to analysis; Baumbach (1987) and Cuénod (1967) both treat palatalization and labialization as phonemic, rather than as reflecting consonants followed by glides. These contrasts exist on top of the voicing, aspiration, and prenasalization contrasts which are also found. If these features are taken to all be mutually compatible, the number of permutations of these features becomes immense. This means that most gaps in the phonological system should be taken as coincidental rather than reflecting any theoretical impossibility.

That said, it is clear that not all features are mutually compatible. Bilabial consonants are never labialized. Lateral, postalveolar, velar, and glottal consonants are not palatalized. Labiodental, “whistled”, and palatal consonants show neither labialization nor palatalization. When it comes to prenasalization, Tsonga is distinct from Copi and Tonga in that voiceless consonants, including fricatives, can be prenasalized. Among the aspirates, it is exceptional that there is a series of prenasalized voiced aspirates which lack a non-prenasalized counterpart. The typological rarity of this is noted in Janson (2001), who suggests that phonetic aspiration here is not phonologically contrastive.

The phonetic character of certain consonants described varyingly as “aspirated” or “breathy” may be called into question, namely the nasals and the rhotic /rɦ/. The latter of these was also remarkable to Janson (2001, p. 27), who remarked that “rhotics cannot really be aspirated”. It seems that the primary phonological difference between these consonants and their unaspirated counterparts is their interaction with tone. Lee (2009) states that the aspirated nasals and rhotics are depressor consonants, which block the process of high tone spread; this is a property that these phonemes share with all the other voiceless and voiced aspirates, but not their unaspirated counterparts. Therefore, even if these consonants do not truly have phonetic aspiration, they still display properties which make them distinct phonemes, and they will continue to be marked with a symbol /ɦ/.

The other set of sounds which deserves attention is the series that Cuénod (1967) and Baumbach (1987) refer to as the “whistled” affricates and sibilants. These are phones which have a distinctive labial element that gives them their whistling sound. Such sounds are found in Tsonga and Tswa, as well as the Southern Bantu language group Shona (S10), but are virtually unheard of outside of the family, only perhaps being attested in certain Caucasian and South Arabian languages (Shosted, 2006). These phonemes seem to be the labialized counterparts of the alveolar affricates and fricatives, and, like the Copi labio-alveolar phonemes, they are often spelled with the retroflex symbols <ʂ> and <ʐ>. The matter of notation is further complicated by allophony within Tsonga; the alveolar affricates may be freely pronounced as retroflex affricates. To make it clear that these phonemes are effectively parallel series, they will all be spelled as retroflex, with the “whistled” affricates being denoted by additional labialization <w>, and the whistled sibilants simply being written <ʂ> and <ʐ>.

The consonant inventory of Changana is almost identical to that of Tsonga. The most significant difference between the two languages is that Changana shows two mergers (Janson, 2001). The first of these is a merger of the Tsonga palatalized bilabial stops and the whistled affricates, with both of these reflected in Changana as labio-alveolar affricates. The second merger is between the Tsonga palatalized alveolar stops and the postalveolar affricates, which are both reflected in Changana as postalveolar affricates. A schematic of this is given in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Phonological correspondences between Changana and Tsonga.

It is also worth mentioning that Changana has two additional implosive stops, /ɓ/ and /ɗ/. Noting that all the languages from Mozambique have such stops, but that South African Tsonga lacks them, it remains a question whether this represents a loss in South African Tsonga or a borrowing in Changana.

1.4. Tswa

Tswa (S51), also written as Tshwa or Xitswa, is spoken by 1,000,000 speakers in Mozambique, with an additional 20,000 speakers in Zimbabwe (Eberhard et al., 2022). Ngunga and Faquir (2012) list five varieties of Tswa: Khambani, Rhonga, Hlengwe, Mhandla, Dzhonge/Donge, and Dzivi. As mentioned in the previous section, the Hlengwe variety is treated as a distinct language by Maho (2009), though Ethnologue (Eberhard et al., 2022) and Hammarström (2019) both list Hlengwe as a dialect. The consonant inventory given in Table 5 and the lexical items cited from Persson (1928) throughout this paper are drawn principally from the Dzivi dialect.

Table 5.

The consonant inventory of Tswa.

Unlike the sources consulted for Tsonga, Ngunga and Faquir (2012) and Gundane (2015) do not provide a detailed account of the distribution of prenasalization, aspiration, and labialization in Tswa. In the absence of descriptive linguistic data, some observations about the spellings used in Persson (1928) may provide insights into the phonological system. Spellings <mp>, <nt>, and <nk> occur, suggesting that voiceless stops may be prenasalized. The spellings <ph>, <th>, and <kh> also occur, though never after <m> or <n>, suggesting the presence of voiceless aspirated stops which do not allow prenasalization. The spellings <bh> and <gh> only ever occur after <m> and <n>, suggesting that voiced aspirated stops only occur when prenasalized, as was the case in Tsonga and Changana. Interestingly, the spelling <dh> never occurs. Finally, the spellings <mh> and <nh> occur, indicating at least the presence of aspirated bilabial and alveolar nasals.

Tswa is distinct among the languages under consideration in having the greatest time gap between the dictionary used and the linguistic resources consulted, this being almost a century. Because of this, it is particularly useful to follow Persson’s descriptions of Tswa’s phonology when appropriate. Persson (1928) makes it clear, for example, that phoneme corresponding to /ʋ/ in Ngunga and Faquir (2012) and Gundane (2015) was, at the time, a voiced bilabial fricative [β]. Furthermore, the phoneme /bʐ/ is consistently spelled by Persson as <by>, suggesting a historic palatalized bilabial stop [bj]. Finally, the palatal stops /c/ and /ɟ/ are claimed to be pronounced like the English affricates [tʃ] and [dʒ]. All of these phonemes are used to transcribe Persson’s data throughout this paper.

1.5. Ronga

Ronga (S54), also written Rhonga or Xironga, is spoken by approximately 618,000 speakers. Almost all of these live in Mozambique, in the region immediately surrounding the capital Maputo, though there is a small group of approximately 1000 speakers living in South Africa, just below the border of KwaZulu-Natal province and Mozambique (Eberhard et al., 2022). As with other S50 languages, the dialectical picture is difficult to decipher. Ngunga and Faquir name four dialects of Ronga: Lwandle/Kalanga, Nondrwana, Zingili, and Hlanganu, with Nondrwana being used as their reference variety. Da Conceição (1999) presents a table from a newspaper article which lists three dialects: Kalanga, Ronga, and Putru. Eberhard also lists three dialects, Konde, Putru, and Kalanga, though it is unclear if this implies that Konde is equivalent to Da Conceição’s Ronga. Maho (2009) gives three Ronga varieties: Konde, Ssonga, and Xonga. While Baumbach (1974) works on what he calls Tsonga varieties, he includes separate entries and phonological inventories for varieties called Konde, Ssonga, and Ronga, among others. Based on the map he includes, his Ronga data comes from the immediate vicinity of Maputo, where Ngunga and Faquir claim Nondrwana is spoken. It is unfortunately unclear which variety Quintão references, if it is any one in particular.

Table 6 combines the speech sounds of Ronga listed in Baumbach (1969, 1974). These sources indicate that most non-labial obstruents can be labialized, but do not list any palatalized consonants. Both these and other sources which have been consulted for Ronga do not provide a detailed account of which phonemes can be prenasalized, and so spellings will again be taken into consideration. Quintão (1951) has spellings which suggest that both voiceless stops and voiceless aspirated stops can indeed be prenasalized. Quintão gives no spellings which indicate voiced aspirates, whether prenasalized or not. Baumbach’s example of /dɦ/, [ndɦawu] ‘place’, does at least point to the existence of prenasalized voice aspirates; Hargus and Da Conceição (1999) also offer the form [ngɦwendza] ‘bachelor’. These words are spelled ndawu and nkwendja in Quintão (1951), suggesting that the voiced aspirates are either innovations or restricted to particular dialects.

Table 6.

The consonant inventory of Ronga.

In addition to the phonemes listed above, Hargus and Da Conceição (1999) note the sparse existence of implosive stops /ɓ/ and /ɗ/, suggesting that such forms only come from Changana loans. Ngunga and Faquir (2012) also list implosives in the inventory of Ronga, and corroborate their rarity within the language.

Unlike most of the languages under consideration, Ronga seems to possess a genuine and contrastive series of retroflex affricates. Cross-referencing lexemes cited in Quintão (1951) and Baumbach (1969) shows that Quintão systematically distinguishes the spelling of the voiceless retroflex affricates from the voiceless postalveolar affricates, but spells both voiced retroflex and voiced postalveolar affricates as <dj>. In this paper, a Ronga form cited with /dʒ/ may therefore actually reflect a retroflex affricate.

It is also pertinent to discuss the representation of the labio-alveolar obstruents in Tswa. The phoneme given as /bʐ/ in Baumbach (1969) and Ngunga and Faquir (2012), and /bʐw/ in Hargus and Da Conceição (1999), is consistently spelled <by> by Quintão. This will be represented in this paper as a palatalized bilabial stop /bj/. The phoneme given as /pʂ/ in Baumbach (1969) and Ngunga and Faquir (2012), and /pʂw/ in Hargus and Da Conceição (1999) is consistently spelled <bs> by Quintão. This will be represented as /pʂ/, as it seems unlikely that the two components of the affricate would disagree in voicing. Baumbach (1969) only gives one lexeme attesting /pʂh/, which is [pʂha] ‘burn’. Quintão (1951) has two entries for this, spelled bsa and pya. The former will be transcribed as the phoneme /pʂ/, and the latter as a palatalized voiceless bilabial stop /pj/. As for the labio-alveolar sibilant /ʂ/, the form given as [ʂoʂi] ‘now’ in Baumbach (1969) is spelled bsobsi by Quintão. It is not clear whether this reflects a merger with /pʂ/ or is simply a deficient spelling. Nevertheless, it will be transcribed /pʂ/, and the potential ambiguity should be kept in mind. The voiced labio-alveolar sibilant /ʐ/ is only cited in a clan name, which is unattested in Quintão (1951).

Finally, attention must be called to the phonemes /b/ and /v~β/. Both of these are spelled in Quintão (1951) with <b>. Interestingly, all the reflexes of /b/ cited by Baumbach (1969) occur before /u/, suggesting that these are not two distinct phonemes but rather conditioned allophones of a single phoneme. Nevertheless, both will be reflected as /b/ in this paper as Quintão’s spelling makes it impossible to differentiate.

1.6. Proto-Bantu

The reconstructed consonant inventory of Proto-Bantu, seen in Table 7, is exceptionally small in comparison to all of Tswa-Ronga and Copi-Tonga. In practice, these phonemes likely had a variety of allophonic variants, and Meeussen (1967, p. 83) suggests *d might as well have been transcribed as *l, *c as *s, and *j as *z or *y. As the language developed, allophony at this level would be vulnerable to sound changes which might phonemicize it. Yet another significant source of development in the daughter Bantu languages were nasal/stop combinations. These sequences often formed units with distinct phonological outcomes, as will be seen for Tsonga-Copi in the subsequent sections.

Table 7.

The reconstructed consonant inventory of Proto-Bantu from Meeussen (1967).

Proto-Bantu is reconstructed with a 7-vowel inventory as shown in Table 8. This includes the canonical five vowels *a, *e, *i, *o, *u, as well as two near-close vowels *ɪ, and *ʊ (Bastin et al., 2002).

Table 8.

The reconstructed vowel inventory of Proto-Bantu.

The PB close vowels, when following a stop, triggered a spirantization process which generally yielded affricates or fricatives in the daughter languages (Bostoen, 2008). The immediate result of this change would have been allophonic, but it was often phonemicized by a subsequent merger of the close and close-mid vowels, the 7-to-5 vowel merger (Bostoen, 2008). While not every language underwent spirantization or the 7-to-5 vowel merger, every language which underwent the merger also underwent spirantization (Schadeberg, 1994). The Tswa-Ronga and Copi-Tonga languages all underwent both changes, and all languages in each family have a 5-vowel system. As will be seen in Section 3, spirantization is a major source of innovation in the consonant inventory of PTC and its daughter languages.

2. Materials and Methods

The first step was to assemble an initial list of lexemes to search for in each language. These were compiled from a composite of the 200-word Swadesh list (Swadesh, 1952), the entries in the word list in Gunnink et al. (2022), and the glosses in Van der Spuy’s (1989) reconstruction of Proto-Southern Bantu.

Seven dictionaries were then consulted to identify corresponding lexemes in the daughter languages, these being Amaral et al. (2007), a bidirectional Portuguese-Tonga dictionary; Dos Santos (1949), a bidirectional Portuguese-Copi dictionary; Smyth and Matthews (1902), a unidirectional Lenge-English dictionary; Cuénod (1967), a unidirectional Tsonga-English dictionary; Sitoe (1996), a unidirectional Changana-Portuguese dictionary; Persson (1928), a unidirectional English-Tswa dictionary; and Quintão (1951), a bidirectional Portuguese-Ronga dictionary. Many of the dictionaries selected did not include sufficiently descriptive information about the phonology of the languages, so additional sources had to be sought out to convert the orthographic representations into phonological transcriptions. The lexemes were entered into the list according to the principles outlined in Section 1.1, Section 1.2, Section 1.3, Section 1.4 and Section 1.5. Tone information was not included, as only the Tsonga and Changana dictionaries (inconsistently) marked it.

Whenever a dictionary entry gave multiple translations for a given lexeme, all were entered into the list of results. For those dictionaries which were bidirectional, all English or Portuguese terms in the reverse direction were also copied and searched for, in order to control for slight semantic alterations. This ultimately created something of a word “web”, with one entry having multiple potential translations in English, Portuguese, and the various Bantu languages.

After this initial set of words had been obtained, additional words were added to the list; search items were chosen by going through each dictionary to find words containing rarer phonemes or sequences, such as different combinations of aspiration, palatalization, and labialization. Only those words which did not seem to have meanings too unclear or too abstract were chosen. Once these were added to the list, their correspondents in the other languages were filled in. The resulting list constituted the final search list.

Next, the data was pruned. For each lexeme, it was considered a valid cognate series if there was at least one correspondent from Tonga and Copi/Lenge, and two correspondents from Tswa, Ronga, and Tsonga/Changana1. If a lexeme had multiple translations, and these seemed to show multiple cognate sets, these were then separated into unique entries. Given the absence of prior research on phonological correspondences between the given languages, correspondence was determined in an impressionistic manner. The potential for error that such a process invites should be noted. With the resulting data, the Bantu Lexical Reconstructions 3 (BLR3) database (Bastin et al., 2002) was searched to find a reconstruction2 corresponding to each lexeme, if possible. The resulting cognate sets were then used to determine which sound changes took place in the languages under consideration and determine a Proto-Tsonga-Copi reconstruction, the results of which are given in the following section.

3. Results

The following section details the outcomes of each of the traditionally reconstructed Proto-Bantu phonemes. Prenasalized stops are treated in the same section as their oral counterpart. For each phoneme, an overview of the identified sound changes is given, followed by tables with illustrative cognate sets of the relevant phoneme present in a variety of conditioning environments. A proposed Proto-Tsonga-Copi reconstruction is provided for each set; a class prefix is present in nominal reconstructions when the daughter languages point to the same original noun class; otherwise, these reconstructions begin with a bare hyphen. Finally, an existing Bantu reconstruction from the BLR3 database is included with each entry where a likely match was identified. These forms are given directly as cited in BLR3; this means that final vowels are generally omitted from verbal forms, and nominal forms do not include a class prefix.

3.1. *p

| Tonga | Copi | Lenge | Tsonga | Chang. | Tswa | Ronga | PTC | |

| ph | ph | p | mɦ | mɦ | mɦ | mɦ | *mph | *N_ |

| s | s | s | f | f | f | f | *ps | *_i |

| tsh | tsh | tʃ | ns | ns | s | ns | *psh | *N_i |

| f | f | f | f | f | f | f | *f | *_u |

| ph | ph | p | ɦ | h | h | ɦ | *ph | *V(#)i_ in nouns |

| s | psw | sw | ʂ | ʂ | ʂ | ʂ | *phj | *V(#)i_ in verbs |

| βj | ɦj | hj | ʈʂhw | pʂh | ʂ | pʂ/pj | *bɦj | *_ɪV |

| phj | phj | phj | ɳʈʂhw | mpʂh | ʂ | mpʂ/ntʃ | *mphj | *N_ɪV |

| βw | phw | hw | phj | pʂh | pʂ | - | *bɦw | *_ʊV |

| p | p | p | p | p | p | p | *p | early borrowings? |

| β | ɦ | h | ɦ | h | h | ɦ | *bɦ | elsewhere |

As seen in Table 9, almost all the languages have glottal fricatives as reflexes of PB *p, but Tonga retains a bilabial sound. Furthermore, both Tonga and Copi reflexes are voiced, along with those of Tsonga and Ronga. The chain from PB into PTC would therefore likely be *p > *ph > *bɦ. The aspiration of the voiceless stop to *ph is well attested for Southern Bantu as a whole (Janson, 1991–1992), but the subsequent voicing development would represent an innovation within Tsonga-Copi. The intermediate voiced stop is lent support by synchronic pairs in Tsonga like m-bɦaɲi ‘living person’, a class 1 agentive derivation from ɦaɲa ‘live’, as well as the cognate set for ‘fruit’.

Table 9.

Reflexes of PB *p in Tsonga-Copi.

The complex *mp, which is typically attested as a combination of the class 9 prefix *N- with nominal roots beginning in *p, is reflected by /ph/ in Copi-Tonga and /mɦ/ in Tswa-Ronga as shown in Table 10. This shows a development of *mp > *mph, with no further shared development. In Copi-Tonga, the nasal component was then lost, whereas Tswa-Ronga lost the obstruent, with both retaining aspiration. In the latter, this yields an outcome partially overlapping with that of *mʊ-p seen above in the set for ‘fruit’, though Tsonga/Changana is still distinct.

Table 10.

Prenasalized reflexes of PB *p.

The reflexes of PB *p followed by the close vowels *i and *u trigger spirantization, as discussed in Section 1.6. As seen in Table 11, PB *pi seems to yield /s/ in Copi-Tonga and /f/ in Tswa-Ronga. Isolated examples seem to offer support, such as Tonga simbo ‘branch’ < PB *pímbò, and Tsonga fika ‘arrive’ < PB *pìk. This suggests a complex consonant or affricate at the PTC level, which had both a labial and an alveolar component; this phoneme in PTC will be represented as *ps. This phoneme appears to have further distinct reflexes after a nasal, such as the class 9 prefix in *m-pígò. The Tonga reflex of this lexeme suggests aspiration, which is paralleled by the outcomes and reconstructions of other nasal + voiceless consonant series. It will therefore be reconstructed as *m-psh. As for PB *pu, all languages show an outcome of /f/. This is identical to the situation for PB *ku sequences (see Section 3.4), though the reflexes of *ki are not the same as those of *pi. This means that an allophonic alternation inherited from PSB would have been phonemicized due to partial merger, and that the resulting phoneme should be reconstructed as *f.

Table 11.

Reflexes of PB *p showing spirantization.

The vowel *i also causes unique outcomes in certain cases when immediately preceding a consonant. As Wills (2025) extensively details, this occurs when *i would be expected to occur in hiatus. As Proto-Bantu allowed only open syllables, this would mean any word-initial *i would be a trigger. This generally arises as a result of the noun class 5 prefix *i-, or in certain lexical items where initial *ji is traditionally reconstructed (Wills instead reconstructs *i).

The tendency for class 5 words to show initial mutation was already noticed by Lanham (1955). Van der Spuy (1989, p. 136) observed a similar phenomenon in the Southern Bantu languages Northern Sotho, Venda, and Zezuru. He describes the effects in these languages as “to insert an offglide after a following stop consonant,” although that does not seem to describe the situation for Tonga nouns, where the mutation creates an outcome that often resembles what would be expected of an initial nasal. The class 5 prefix seems to stop the chain of PB *p > *ph > *bɦ before the voicing step, as did the nasal prefix.

Table 12 shows that the effects of class 5 do not apply equally across Tsonga-Copi. They are rarely seen in Tsonga, and only occasionally seen in Copi/Lenge. They are most frequently encountered in Tonga, where class 5 alternation appears to have at one point been relatively robust morphophonological process. However, Lanham (1955, p. 71) notes that such forms were already starting to disappear, which he attributes to the disruptive absorption of class 11 words with no alternation into class 5. Analogy seems to be the major culprit for the lack of expected mutation in many forms; their class 6 plural forms would not show any changes, and analogy with these forms would inevitably lead to some amount of leveling. This would be most apparent in words like *pácà ‘twin’ which appear much more frequently in the plural. Nevertheless, it is clear that at the level of PTC these outcomes were distinct, and they will be reconstructed as *ph.

Table 12.

Reflexes of PB *p following *i.

While initial *i in nouns has been accounted for, the verbs still pose a problem. Two outcomes are seen, one that generally yields a voiced bilabial stop /b/ and another that yields a labiodental affricate or labialized sibilant. One reviewer suggested that bika ‘cook’ is instead a loanword from Shona, making the reflexes with /(p)ʂ/ the inherited forms. While it may seem dubious for such a basic term to be replaced, Guthrie (1971, p. 188) notes that the meaning of *jìpɪk may have been more specific, something akin to ‘stew’. It is notable that the reflexes of *jip strongly resemble the reflexes of *pɪa seen in Table 13 below, suggesting the presence of a glide, as has been posited by Van der Spuy (1989, p. 136) and Wills (2025, p. 11). In parallel with the nouns, as well as the outcomes of PB *t and *k in similar environments, it seems that PB *p was first aspirated in this environment, at which point the consonant underwent metathesis with the preceding vowel, which then became a glide. This can be schematized as PB *ip > PTC *phj. In the daughter languages, the labial consonant underwent further palatalization in a process described in detail by Ohala (1978). As seen below and in Section 3.5, glides do not generally palatalize labials in Copi-Tonga. The lack of voicing does not seem to be a factor, as the PB class 8 prefix *bi- yields Copi-Tonga si-, Tsonga/Changana ʂi-, Ronga pʂi, and Tswa ʐi-. More data is necessary to determine whether there is another conditioning factor present, or if perhaps there were two separate historical palatalizations. Finally, as for the apparent reflexes of *jípʊd, more terms are needed to determine whether there is a unique outcome of PTC *phj before *u, or if the entries here are instead loanwords in one or both language groups.

Table 13.

Reflexes of PB *p followed by a semivowel.

In PB syllables of type *CɪV and *CʊV, the near-close vowels *ɪ and *ʊ became the glides *j and *w, respectively. While the reflexes across Tswa-Ronga show significant further development of the sequences *pj and *pw, the expected development of *p into /β/ in Tonga and /h/ in Lenge make it clear that at the level of PTC, these stop-glide sequences behaved as two distinct phonemes. Therefore, the development of PB *p described earlier should be applied, and these sequences should be reconstructed as *bɦj and *bɦw, respectively.

There remains a group of words reflecting PB *p which always yield unaspirated /p/ in the daughter languages with no apparent conditioning element. It is possible that these words, which are listed in Table 14, reflect late PTC borrowings from other Bantu languages, and there is a typological argument for why they may have been integrated; the unconditioned change from *p to *bɦ would give the language a series of voiced and voiced aspirate stops, but only prenasalized voiceless stops. This seems like an implausible system, but the issue is remedied by positing the existence of a voiceless stop series unexplainable through direct inheritance. The identity of the potential donor language is discussed in Section 4.3.

Table 14.

Reflexes of PB *p with aberrant synchronic /p/.

3.2. *t

| Tonga | Copi | Lenge | Tsonga | Chang. | Tswa | Ronga | PTC | |

| th | th | t | nɦ | nɦ | nɦ | nɦ | *nth | *N_ |

| tsh | s | s | s | s | s | s | *ts | *_i |

| pfh/f | pʂh/tsh/f | prh/tsh/f | f | f | f | f | *f | *_u (tentative) |

| th | th | t | rɦ | rɦ | r | ʐ | *th | *V(#)i_ in nouns |

| tsh | tsh | ts | s | s | s | s | *tsh | *Vi_i, |

| th | th | t | tʃh | tʃh | tʃ | tʃ | *thj | *V#i_ in verbs, *_ɪV |

| rw | rw | hw | rɦw | rɦw | rw | ʐw | *dɦw | *_ʊV |

| t | t | t | ʈʂ | ts | ts | ʈʂ | *t | early borrowings? |

| r | r | h | rɦ | rɦ | r | ʐ | *dɦ | elsewhere |

Unconditioned outcomes of PB *t are given in Table 15. In most environments, PB *t is reflected by a rhotic in all the daughter languages except Ronga (where it is spelled <r>, suggesting a recent change from *r > /ʐ/) and Lenge. Interestingly, Tsonga and Changana have a breathy trill /rɦ/. This contrasts with /r/, which appears in reflexes of PB *dɪ (see Section 3.6). Tsonga and Changana thus show a retention of aspiration from PTC rather than an internal innovation. If we assume that the voiceless stops underwent changes relatively in parallel, then an unconditioned change of PB *t > pre-PTC *th along the lines of *p > *ph would be expected, with *th subsequently developing into *rɦ. If one expects total parallelism with *p, then it makes sense to also assume an intermediate voicing step, making the full sequence PB *t > *th > *dɦ > *rɦ. As with PB *p, synchronic support for such a step can be found in the Changana preposition ndzɦaku ‘behind’3, which appears to reflect the PB root *tákò ‘buttock’ with a class 18 prefix4. Additionally, the Tsonga and Tswa class 3 words for ‘shadow’, ɳ-ɖʐɦuti and n-zɦuti, exist alongside non-class 3 counterparts mi-rɦuti (Tsonga) and ʃi-ruti (Tswa). This suggests allophonic variation between *dɦ and *rɦ in PTC, which was continued into Tswa-Ronga. Additional support from Copi-Tonga is found in Lenge, where the regular outcome is /h/5. Considering this, as well as the likely parallelism between *p and *t as voiceless stops, the reflex of PB *t will be reconstructed as *dɦ in PTC, though it was already likely realized as [rɦ] in most positions.

Table 15.

Reflexes of PB *t in Tsonga-Copi.

When following a nasal, PB *t yields /th/ in Copi-Tonga and /nɦ/ in Tswa-Ronga, as shown in Table 16. This directly parallels the outcome of *mp, and its phonological history should be reconstructed accordingly. The resultant change was thus PB *nt > PTC *nth.

Table 16.

Prenasalized reflexes of PB *t.

There are also clear spirantized reflexes of *t. PB *t followed by *i,yielded /tsh/ in Tonga and /s/ in all the other languages. In Tonga, /tsh/ and /s/ are separate phonemes, the latter being a reflex of PB *p before *i (cf. Section 3.1), and, in some instances, *c (cf. Section 3.3). The Tonga reflex thus cannot be explained as an internal development of /s/ to /tsh/, and should therefore form the basis of the reconstruction for PTC. The phoneme *ts will be reconstructed, which was ultimately simplified to /s/ in Copi and Tswa-Ronga. The reflex of *tu in PTC is more ambiguous; PB *tu in Tswa-Ronga consistently yields /f/, but the situation is less clear for Copi and Tonga. The reflexes of PB *tù ‘cloud’, the fifth entry in Table 17 below, point to a labial affricate of some sort, but the final vowel /i/ is difficult to explain; it is possible that these words are then derived from a different root. It is also possible that the Copi-Tonga forms have been mutated by the class 5 prefix *i-. The reflexes of PB *túd somewhat parallel *tù, but again the Copi-Tonga data is unclear. The Tonga form may reflect pure inheritance, but it may also show influence of an original preceding reflexive pronoun *i, if /pfh/ is assumed to result from mutation like in *tù. The Copi and Lenge variants are harder to explain, but are perhaps a case of dialectical variation; Bailey (1995, p. 142) mentions that the phoneme that his consultant pronounces as /pʂ/ is pronounced in most other dialects as /tsw/. It is not hard to imagine a parallel situation for the aspirated counterpart of /pʂ/, with the lack of a corresponding glide in tshula due to coalescence with the following /u/. It is also possible that the Copi and Lenge forms are due to morphological complexity, with the Copi form only attested in a single verb angatshula ‘he can forge’ in Bailey (1976, p. 70) and the Lenge form being a class 5 noun meaning ‘hearthstone’, again with potential influence from the class 5 prefix. PB *túg consistently shows /f/, though, given the overall unclear data in Copi-Tonga, it is difficult to say whether their terms could be loanwords. For now, PTC *f will be taken as the very tentative reflex of PB *tu, merging with *pu and *ku, as most of the aberrant Copi-Tonga reflexes have plausible alternative morphophonological explanations.

Table 17.

Reflexes of PB *t showing spirantization.

As with other stops, class 5 mutations are found and given in Table 18. These yield /tsh/ in Tonga and Copi before *i, and /th/ before *a or perhaps elsewhere. These will be projected directly back as *tsh and *th, with the lack of parallel in Tswa-Ronga attributed to analogy or later developments. The Tswa-Ronga reflexes of *jìtɪd support the presence of an off-glide, as was seen for *p. This glide must have been lost in Copi-Tonga.

Table 18.

Reflexes of PB *t after *i.

Unfortunately, there are not many clear examples of *t before glides. PB *t does not appear to have a unique outcome before a labial glide, with the daughter languages pointing simply to *dɦw in PTC. The reflexes of *tíab in Table 19 are identical to those of *jìtɪd above, indicating that before a palatal glide PB *t merged with *it into PTC *thj. This merger aligns with Wills’ (2025) claims of *ɪ conditioning similar changes to *i.

Table 19.

Reflexes of PB *t followed by a semivowel.

Table 20 gives three PB lexemes for which the Tsonga-Copi reflexes are aberrant but corresponding. In these sets, PB *t is reflected by Copi-Tonga /t/ and Tswa-Ronga /ts~ʈʂ/, regardless of the presence of a nasal. One of these items, *pèt, also shows diachronically unexplainable /p/ (see Section 3.1). These words appear to represent a class of loanwords which entered Tsonga-Copi after the reflexes of original PB *p and *t had been aspirated or voiced. Critically, the phoneme that these sounds represent, at whatever stage of Copi-Tonga they were borrowed into, was distinct from the phoneme *z yielded by PB *j and *g (see Section 3.7 and Section 3.8), or else one would expect identical reflexes of these sounds in Tswa-Ronga.

Table 20.

Reflexes of PB *t with aberrant synchronic /t/ and /ts/.

3.3. *c

| Tonga | Copi | Lenge | Tsonga | Chang. | Tswa | Ronga | PTC | |

| ndz? | tsh | ts | nɬ | nɬ | ɬ | nɬ | *nɬ | *N_ |

| tsh | tsh | ts | ns | ns | s | ns | *nɬ | *N_i, *N_ɪ |

| tsh | tsh | ts | ɬ | ɬ | ɬ | ɬ | *iɬ | *i_ |

| tsh | tsh | ts | s | s | s | s | *iɬ | *i_i, *i_ɪ |

| ɦw | ʃw | ? | ɬw | ɬw | ɬw | ɬw | *ɬw | *_ʊV, *_oV |

| h | s | s | s | s | s | s | *ɬ | *_i, *_ɪ |

| s | s | s | ɬ | ɬ | ɬ | ɬ | *ziɬ | *iji_ |

| h | s | s | ɬ | ɬ | ɬ | ɬ | *ɬ | elsewhere |

Table 21 shows that all the daughter languages have voiceless fricatives as unconditioned reflexes of PB *c. Interestingly, the fricatives in Tswa-Ronga are all laterals, which are typologically quite rare sounds (Maddieson, 2013; Van der Vlugt & Gunnink, 2025). The question then remains, which of these situations (if either) is most like the original? To solve this, one must do a bit of bottom-up reconstruction. The reflexes in Tswa-Ronga unambiguously point to *ɬ. For Copi-Tonga, it seems instinctive to posit that Tonga /h/ results from debuccalization of an original *s, reflected directly in Copi. This debuccalization did not seem to occur before Tonga /i/, in which context the reflex of *c effectively merged with that of *p and *k.

Table 21.

Reflexes of PB *c in Tsonga-Copi.

The question is now whether *s or *ɬ is original, if either. Kümmel (2007, p. 248) states that lateralization of fricatives is quite rare, and he lists no examples of the unconditioned change of /s/ into /ɬ/. On the other hand, there are numerous attested examples of the opposite change, /ɬ/ becoming /s/ without condition. This would mean that a situation with an *ɬ in PTC is most supported cross-linguistically. At this point, it is important to take into consideration that PB *c has different reflexes when it occurs before *i and *ɪ, given in Table 22 below. These reflexes have /s/ in all languages except Tonga, which shows subsequent debuccalization. The two scenarios are that an original *s became /ɬ/ in Tswa-Ronga when not before synchronic *i, or that an original *ɬ became /s/ unconditionally in Copi-Tonga and only before synchronic *i in Tswa-Ronga. Given the high typological probability of the change *ɬ > /s/, the latter will be assumed to be correct, and it seems equally likely that the change took place independently in Tswa-Ronga and Copi-Tonga or that it had already begun in PTC, progressing further in Copi-Tonga after it had split from Tswa-Ronga6.

Table 22.

Reflexes of PB *c before *i and *ɪ.

When following a nasal, Tonga and Copi show an aspirated affricate /tsh/, whereas Tswa-Ronga have an alternation of /s/ and /ɬ/, as seen in Table 23. As in other environments, this appears to be conditioned by the following vowel. For now, it does not seem necessary to reconstruct this sequence as anything besides *nɬ, with the Copi-Tonga reflexes showing development of a cluster *n(t)s < PTC *nɬ.

Table 23.

Prenasalized reflexes of PB *c.

Reflexes of *c followed by *ʊ are problematic. While the Copi-Tonga cognates generally behave, Tswa-Ronga seems to alternate between /ɬ/ and /s/ or /ʃ/. This happens both when comparing different lexemes, with *cʊ̀ʊj in Table 24 yielding /ɬ/ and *cʊ́ndʊ̀è yielding /s/, but also when comparing a single lexeme between different languages, such as with *cʊ́ngʊ́. In light of these facts, it seems that whatever development is occurring here is secondary, perhaps reflecting a still ongoing process of replacing original *ɬ.

Table 24.

The reflexes of PB *c before ʊ.

The reflexes of *ic in Table 25 are generally the same as *nc. An exception is *jícò, where Copi-Tonga has /s/ instead of /tshi/. Comparing the Tonga singular li-so to its plural ma-ho with regular /h/ makes it clear that the class 5 prefix *i is the cause. The preservative effect of *i on *c is noted by Wills (2025, p. 16), but it remains to be explained why the outcomes are inconsistent. At the moment, it seems that the easiest way out is to posit that /s/ is the reflex of the phonological complex *i-jic (or *i-zic), though alternative suggestions are welcome. As for the reconstruction of *ic, an aspirated *ɬʰ would parallel other series, but itself does not seem to be phonetically possible. For this reason, I will use *iɬ with a preceding superscript for this variant of *ɬ as a notational convention.

Table 25.

Reflexes of PB *c after *i.

It is possible that Copi shows a unique development of PB *c followed by a rounded vowel. In these environments, Copi has /ʃ/ with additional labialization if followed by another vowel. It seems that this is a development internal to Copi that is subject to dialectical variation. The Copi verb for ‘set (of the sun)’ is given by Dos Santos (1949) as pʂwa and Bailey (1995) as ʂa, with a Lenge equivalent ʃʷa (< PB *cò-a, c.f. Tonga ɦʷa, Tswa ɬʷa). Applicative forms of this verb meaning ‘delay’ are found in most languages and given in Table 26. Dos Santos also gives the alternative form swela for ‘delay’. Clearly there is substantial synchronic variation within Copi, and at present there is no reason to require this to carry back into PTC or Proto-Copi-Tonga.

Table 26.

Labialized reflexes of PB *c, showing palatalization in Copi.

A few forms still defy explanation. Table 27 gives two forms for which at least some of Tswa-Ronga have lateral affricates for PB *c, and Copi has an alveolar affricate. There does not appear to be any obvious conditioning feature here that would make these reflexes different than that of, e.g., *cándú ‘branch’ (see Table 25 earlier). The most likely case is that they are loans. A reviewer pointed out that Lenge li-handi ‘five’ is cognate to Tonga li-βandre, with the Copi term being a loan from Tswa-Ronga. This suggests that the affricates seen in Copi-Tonga are simply a manner of adapting the lateral obstruents from Tswa-Ronga into the native phonology.

Table 27.

Aberrant reflexes of PB *c, with sporadic lateral affricates in Tswa-Ronga.

3.4. *k

| Tonga | Copi | Lenge | Tsonga | Chang. | Tswa | Ronga | PTC | |

| kh | kh | k | ɦ~gɦ | h~gɦ | h | ɦ | *ŋkh | *#N_ |

| tsh | tsh | ts | s | s | s | s | *ns | *N_i |

| pfh? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | *N_u |

| ŋg | ŋg | ŋg | ŋg~ ɦ | ŋg~ h | ŋg~ h | ŋg~ ɦ | *ŋk | *VN_ |

| tsh | tsh | ts | s | s | s | s | *is | *Vi_ |

| kh | kh | k | kh | kh | kh | kh | *kh | *V#i_ in nouns |

| kh | kh | k | s | s | s | s | *khj | *V#i_ in verbs |

| s | s | s | s | s | s | s | *s | *_i |

| s | s | s | ʃ | ʃ | ʃ | ʃ | *s | *ʊ_i, *o_i |

| f | f | f | f | f | f | f | *f | *_u |

| ɣj | tʃ | kj~tʃ | ʃ | ʃ | tʃ | ʃ | *kj | *_ɪV,*_eV |

| f | f | f | f | f | f | f | *f | *_u |

| g | g | g | k | k | k | k | *k | *mʊ_ |

| ɣ | k | k | k | k | k | k | *k | elsewhere |

When it comes to the reflexes of PB *k, the spirantized reflexes shown in Table 28 are the most straightforward. PB *k before *u consistently yields /f/ in all daughter languages, and can directly be reconstructed as *f in PTC. The situation is a bit more complicated before PB *i. In Tswa-Ronga, the reflex is generally /s/, which was sometimes palatalized to /ʃ/. The Copi-Tonga forms point to /s/, with the class 9 reflexes of *kígè ‘eyelash’ yielding /tsh/. The former can be taken to be the default, and the latter a reflex of the *PB sequence *nki. Unsurprisingly, the reflexes of *i-ki are identical, as shown by *jíkì ‘smoke’. The outcome of *nku, has yet to be found, although the Tonga class 9 word pfhumu ‘chief’ < *N-kúm suggests that it is /pfh/ within Copi-Tonga.

Table 28.

Reflexes of PB *k showing spirantization.

Before settling on a spirantized PTC reflex of *k, it is worth looking a bit further into palatalization. Table 29 lists roots which have clear causative pairs7; the sequence *ki mostly yields /s/, though in Tswa-Ronga, it occasionally yields /ʃ/. It seems that when preceded by a rounded vowel, /s/ palatalizes further to /ʃ/ in Tswa-Ronga, as is also seen in the reflexes of ‘bee’ above8. The reflexes of *tíg-ʊk-i ‘remove’ are an exception to this, possibly blocked by the spirant in the preceding syllable. Regardless, it seems that *s should be reconstructed as the regular outcome of PB *ki in PTC, with corresponding PTC *ns < PB *nki. As for *ik, this will be represented as *is for similar phonetic reasons as *iɬ.

Table 29.

Non-causative and causative verb pairs with stems ending in PB *k.

For reflexes of *k in other environments, most of the languages have /k/, as shown in Table 30. Tonga is unique in reflecting *k with the voiced velar fricative /ɣ/. If the same series of changes are posited for PB *k as the other voiceless stops, then the chain would be *k > *kh > *gɦ. This would leave an easy explanation for the voicing in Tonga, but would require independent devoicing and deaspiration of the same phoneme in Proto-Tswa-Ronga and Proto-Copi. This seems far more complicated than simply hypothesizing a Tonga internal development of *k > ɣ, and no changes whatsoever in all the other languages. An alternative hypothesis would suggest free variation between a PTC *k~g; since PB *g was typically lost or became *w in PTC, a phonological gap would have existed in the velar series, making voicing noncontrastive if it occurred. Following this, a single phoneme *k will be reconstructed.

Table 30.

Reflexes of PB *k in Tsonga-Copi.

The reflexes of *k in initial position in nominal roots show great diversity, but a clear picture can be obtained when these roots are divided up by noun class. The roots in Table 31 belong to class 9 (prefix *N-) and take plurals in class 10 (prefix *tiN-). The reflexes here are greatly varied, but a narrative can still be constructed. In class 9 and 10 forms, the initial PB sequence *nk became aspirated, just like *mp and *nt. At least in Tswa-Ronga, the resultant sequence *ŋkh was subsequently voiced to *ŋgɦ, and then usually simplified to *ɦ. This was maintained in Tsonga and Ronga, but devoiced in Tswa and Ronga. In Copi-Tonga, it seems most likely that the only development from *ŋkh was the loss of *ŋ, yielding *kh and phonologizing an aspiration contrast for velars.

Table 31.

Reflexes of initial PB *k in class 9 roots.

This series of changes in PB *k functions almost as a spectrum, with different languages showing different degrees of adherence. Tonga most consistently reflects simple aspiration, while Copi shows roughly equal amounts of /kh/ and /ɦ/. Perhaps the former is inherited and the latter is a loan, but the synchronic situation is nevertheless quite mixed. Tswa-Ronga generally has /ɦ/ or /h/, reflecting the full series of sound changes. When it comes to the root *kópè, multiple words reflecting this root appear to exist synchronically in Tsonga: there is n-gɦoɦe ‘forehead’, but also ri-koɦe ‘eyebrow’ and ri-ɦoɦe ‘eyelash’. This suggests that as the changes progressed, competing forms which existed simultaneously could be lexicalized and retained in parallel.

The class 11 prefix *dʊ- did not generally trigger any phonological changes, but since its plural counterpart is also class 10, such words were frequently subjected to analogical alteration. Table 32 shows both the class 11 and class 10 reflexes of the PB root *kʊ́nì. Tsonga and Ronga have a singular with no sound changes existing alongside a plural with the full shift to /ɦ/. The singular in Changana has been reformed analogically by the plural. In Copi-Tonga, the singular has also been reformed analogically from the plural, carrying over the aspiration derived from the sequence *nk. Within Tonga, there also exists a class 7 reflex of *kʊ́nì, ɣi-ɣuni, which shows the typical unconditioned development of *k into /ɣ/.

Table 32.

Class 11 and 10 reflexes of PB *kʊ́nì ‘firewood’.

In class 3 roots beginning with *k, given in Table 33, the usual unconditioned reflex /k/ is found along with /g/ (with the Tsonga and Changana reflexes of *kídà showing subsequent palatalization). The class 3 prefix in PB was *mʊ-, which often simplified to a homorganic nasal across Tsonga-Copi. This change did not take place early enough for the prefix to merge with that of class 9, and so these roots do not show a merger with the PB sequence *nk. In Tonga, this prefix either fortified the fricative /ɣ/ into /g/, or prevented the lenition of an original Proto-Tonga *g (< PTC *k) into /ɣ/.

Table 33.

Reflexes of initial PB *k in class 3 roots.

Similarly to the situation before *t, class 5 roots beginning with initial PB *k generally have aspirated /kh/ as an outcome, though the reflexes in Table 34 are not consistent. Lanham (1955) and Van der Spuy (1989) both contend that this rule seems to have been applied sporadically; to me, it seems like most instances of the rule not applying can be ascribed to analogical influence from their class 6 counterparts. In many languages, this alternation has not been fully leveled; the plurals for ‘ten’ in Tonga and Tsonga are ma-ɣumi and ma-kume, respectively, showing unaffected reflexes of PB *k. Tswa and Ronga have both kele and khele as reflexes of *kédé, showing synchronic competition between the inherited and the analogically leveled forms. The single term ɗi-gume in Copi has /g/, but the word ɗi-khele for ‘frog’ suggests that this is irregular due to Tonga influence. In the plural, Dos Santos (1949) gives the form ma-kume, which would be the expected inherited form, but Junod (1933) instead gives ma-gume, which would be expected if a paradigm was borrowed from Tonga. The overall picture points to *ik yielding *kh in PTT, which was largely retained in the daughter languages (remarkably even in Tswa-Ronga, where effects of preceding *i are rarely seen).

Table 34.

Reflexes of PB *k after *i.

In the verbal roots with *ik, the Copi-Tonga reflexes have /kh/, while Tswa-Ronga has /s~ʃ/. As was the case for PB *ip and *it, these forms seem to reflect aspiration followed by insertion of an off-glide via metathesis. The Copi-Tonga forms lost this glide, as was seen for *it, whereas in Tswa-Ronga, it caused palatalization. The forms with /ʃ/ could be attributed to a secondary palatalization caused by the following *ʊ, though in other such instances, it was a preceding *ʊ, which triggered palatalization.

Certain instances of PB *k before front vowels yield palatalization to /(t)ʃ/ in Tswa-Ronga and Copi. The Tonga reflex of *ké ‘dawn’ in Table 35 shows no evidence of palatalization, meaning that this palatalization is a post-PTC development. This fact is supported by the occasional lack of palatalization in Tswa and Ronga, and the typological regularity of /k/ palatalizing before front vowels (Kümmel, 2007, p. 252). The outcomes of the PB class 7 prefix *kɪ- are Tonga ɣi-, Copi tʃi-, and Tswa-Ronga ʃi-, identical to the outcome of *ké. This suggests that these are the regular outcomes of PB *k followed by a non-high front vowel. Perhaps roots like *kín ‘dance’, which show only sporadic palatalization, should be taken as loans, especially given the different forms in Copi and Lenge.

Table 35.

Reflexes of PB *k showing palatalization.

Interestingly, those roots which have PB *nk root-internally show a different outcome compared to initial *nk, as seen in Table 36. In Copi-Tonga, the outcome of such a sequence is /ŋg/. Following this, it appears that the outcome of PB *nk in Copi-Tonga was simply conditioned by the position of the sequence in the word. As for Tswa-Ronga, the three different attestations show three different outcomes: /k/, /ɦ ~ h/, and /ŋg/. It is possible that these were conditioned by the vowels which occurred around them, with the former two reflexes being associated with the PB close vowels. It is also possible that these forms simply reflect various stages of lexicalization of the reflex of PTC *ŋkh as the sound underwent further development in Tswa-Ronga.

Table 36.

Reflexes of root-internal PB *nk.

3.5. *b

| Tonga | Copi | Lenge | Tsonga | Chang. | Tswa | Ronga | PTC | |

| mb | mb | mb | mb | mb | mb | mb | *mb | *N |

| ndz | ndz | nz | mpf | mpf | ? | mpf | *mbz | *N_i |

| ndz | ndz | nz | ɳʈʂhw | mpʂ | ʐ | mpʂ | *mbzj | *N_iV |

| ɓ | p | p | β | β | β | b | *b | *V(#)i_ |

| s | s | s | pf | pf | v | pf | *bz | *_i |

| pf | pf | pf | pf | pf | v | pf | *bv | *_u |

| j? | j~ɓ? | j? | bj | bʐ | bj | bj | *βj | *_ɪV |

| bw | gw~bjw | gw~bjw | bj | bʐ | bj | bj | *βw | *_ʊV |

| Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | *Ø | *mʊ_ |

| w | w | v | β | β | w | b 1 | *β | *_ʊ, *_o |

| v’ | ʋ | v | β | β | β | b | *β | elsewhere |

| 1 Transcriptions from Baumbach (1969) suggest that Ronga /b/ may be realized as [v~β] in this environment, but there are not enough forms cited to make this claim definitively. | ||||||||

Among the reflexes of PB *b before non-close vowels, two series can clearly be spotted. The first is found in reflexes with PB *b followed by the vowels *a, *e, and *ɪ (shown by the first six examples in Table 37), and the second is found in reflexes of *b followed by the rounded vowels *o and *ʊ (shown by the last four examples in Table 37). Tsonga, Changana, and Ronga show the same reflex of *b in these environments, but Tonga, Copi, and Tswa have labial glides instead of their normal reflexes. The question then is whether this distinction existed at the level of PTC, and whether it was phonemic.

Table 37.

Reflexes of PB *b in Tsonga-Copi.

A phoneme *w often arises from the PB vowel *ʊ when followed by a vowel (such as after *g in Section 3.8). In Copi, Tonga, and Tswa, the [w] which results from PB *b has merged with this *w into a single phoneme /w/, as seen in the final three entries in Table 37 above. The clear distinction of the reflexes of these phonemes in Lenge, Tsonga, Changana, and Ronga indicates that such a merger cannot have happened at the level of PTC. Therefore, if there was a separate reflex of *b before rounded vowels at the PTC level, it must have been phonetically distinct from *w. Such a sound would have a complimentary distribution with other reflexes of PB *b, and they therefore need only represent a single phoneme. While it is not possible to conclusively determine if this sound had allophony in PTC, the fact that /β/ and /v/ > /w/ around rounded vowels is a well-attested sound change (Kümmel, 2007) means that it could have easily happened independently (or as an areal change) in Copi, Tonga, and Tswa.

Before assigning a representation for the regular PTC reflex of PB *b, it is worth having a look at the forms in Table 38 where PB *b follows *i. Tonga has /ɓ/ for PB *b, regardless of the following vowel (additional evidence of a lack of allophony in PTC), and Copi and Lenge have occasional /p/. As with other cases of class 5 influence, there are words which do not seem to show any change, such as the reflex of PB *bádà ‘color’. However, as discussed in other sections (see Section 3.2 and Section 3.4), this could simply be due to analogical replacement from a corresponding class 6 term. I will represent the outcome of PB *ib as PTC *b and PB *b as PTC *β based on these sounds being the closest to the modern reflexes, though *ib and *b or *B and *b could be used just as well.

Table 38.

Reflexes of PB *b after *i.

Words in Table 39 seem to show either deletion of PB *b or fusion with a class prefix. In the reflexes of the class 3 words *bòmbó and *bìdì, it seems that the initial sequence *mʊ-b- yielded /m/ in the daughter languages. The Tonga reflex of *bòmbó is class 7, and therefore shows the expected reflex of *b before *o. The Copi and Tswa class 7 reflexes of *bòmbó still have /m/, but this could potentially reflect either a later formation from an already affected class 3 term, or analogical replacement from an unattested class 3 term. The class 6 reflexes of *bícì suggest derivation from a bare root *cì instead, and it is unclear how the initial *bɪ may have been lost. Guthrie (1971) cites no class 3 examples of this root in Bantu; perhaps the class 6 prefix *ma- occasionally showed similar influence, with other forms lost to analogy, or perhaps there was conflation with the class 11 prefix *lʊ-.

Table 39.

Reflexes showing elision of PB *b.

When followed by glides, Tswa-Ronga shows palatalization regardless of the nature of the glide. In Copi-Tonga, there at least seems to have been a distinction maintained between labialization and palatalization, though its ultimate outcome in the daughter languages is unclear. The Copi reflex of *bʊ̀è in Table 40 suggests velarization of the stop, but there is no Tonga cognate to say whether this goes back to PTC. It seems that the regular outcome of a sequence *bj may have been /j/ in Copi-Tonga, though a following front vowel seems to have caused the glide to be lost before it could influence the *b (a development apparently also shared with Tswa and Ronga). The lack of sufficient examples of these sequences makes it impossible to make definitive claims about outcomes in the daughter languages, but what has been identified seems to reflect sequences with two distinct phonemes at the level of PTC, *b followed by either *j or *w, with subsequent developments happening after the PTC period.

Table 40.

Reflexes of PB *b before glides.

As demonstrated in Table 41, the spirantized outcome of PB *b in most of Tswa-Ronga is a voiceless labiodental affricate regardless of whether the following glide is *i or *u, with Tswa having a fricative instead. Copi-Tonga is less clear, with the one reflex of *bi having /s/, and the reflexes of *bu having either /v/ or /pf/. If one assumes that the sequences here show parallel development to the spirantized outcomes of PB *p, it would point to *bz < *bi and *v < *bu. However, the Copi reflexes pfuna < *bún and ʋuna < *gún suggest an affricate outcome *bv < *bu and *v < *gu instead9. PTC *bz was then merged with *bv in Tswa-Ronga, but in Copi-Tonga, it was devoiced and deaffricated to /s/. PTC *bv was devoiced in Copi as well as Tsonga, Changana, and Ronga, but in Tswa, it was only deaffricated. It is possible that the normal outcome of PB *bu in Tonga is /pf/, with the voicing in dzim-bvi being conditioned by the preceding nasal, but a lack of clear reflexes precludes anything more than speculation10.

Table 41.

Reflexes of PB *b showing spirantization.

Both root-internally and in class 9 terms with initial PB *b, the daughter languages have /mb/ in most environments; examples are given in Table 42. For PTC, this can simply be reconstructed as *mb.

Table 42.

Prenasalized reflexes of PB *b.

The sequence *mb also shows unique outcomes when subject to spirantization, though they are not consistent. The relevant roots in Table 43 are *càmb and *dámb with a following causative suffix *i, and *càmb again followed by an agentive suffix *i. Copi-Tonga consistently shows /n(d)z/, but some words in Tswa-Ronga show labiodental affrication and others labioalveolar affrication. The most likely explanation for this is the presence of final *a in the verbal forms, which caused additional glide formation.

Table 43.

Prenasalized reflexes of PB *b showing spirantization.

3.6. *d

Before most PB vowels (*a, *e, *o, *ʊ), PB *d is reflected in all languages as /l/, shown in Table 44 below.

| Tonga | Copi | Lenge | Tsonga | Chang. | Tswa | Ronga | PTC | |

| ndr | nd | nd | ɳɖʐ | ndz | nz | ndʒ | *nd | *N_ |

| ? | ndz | ? | mpf | mpf | v | mpf | *ndzi | *N_i |

| ɗ | ɗ | d | ɖʐ | dz | z | dʒ | *d | *V(#)i_ |

| dz | t | ts | t | t | t | t | *dz | *_i |

| dz | t | ts | pf | pf | v | pf | *dz | *_u |

| l | ɗ | d | r | r | r | dʒ | *l | *V_ɪ |

| l | ɗ | d | r | r | r | ʐ | *l | *V_ɪ |

| dz? | ɟ | g(j) | dj | dʒ | g | d | *dj | *_ɪV |

| dw | lw | dw~lw | lw | lw | lw | lw | *lw | *_ʊV |

| l | l | l | l | l | l | l | *l | elsewhere |

Table 44.

Reflexes of PB *d in Tsonga-Copi.

Table 45 shows that before *ɪ, the situation is quite different. Tonga still yields /l/, but Copi instead yields /ɗ/; Tsonga, Changana, and Tswa yield /r/; and Ronga yields /ʐ/ root-internally and /dʒ/ root-initially. The Tswa-Ronga reflexes are quite similar to those reflexes of PB *t (perhaps not surprising if PB *d is the voiced counterpart of *t), but critically, the Tsonga and Changana reflexes do not have aspiration. The most that can be projected back into PTC is allophony, which was then eliminated or phonologized independently in the daughter languages, either through merger with other phonemes or introduction of loanwords with the conditioned allophones outside of predictable environments. The singular encompassing phoneme at the level of PTC will be reconstructed as *l, which would have been realized as /d/ in certain environments, such as before front high vowels.

Table 45.

Reflexes of PB *d before *ɪ.

In addition to the reflexes above, a series of correspondences for the sequence *di is quite robustly attested and given in Table 46. While it is reflected as /ti/ in most the languages under consideration, it is reflected as /dzi/ in Tonga and /tsi/ in most Lenge forms. Given that *d is voiced, it makes sense to reconstruct a voiced affricate *dz here. This sound would have been the voiced counterpart of the affricate yielded by PB *ti. Tonga and Lenge then show a retention, whereas in the other languages, it has been deaffricated.

Table 46.

Reflexes of PB *d showing spirantization before *i.