The main general observation about the combination of spoken and visual expression in these examples is that, unlike in Spanish, where the primary spoken element is a negative phrase marked by a particle, “no hay” (“there is none”), here, we mainly see the use of the Kichwa verb illa- which means something like “to lack”. The original Quechuan phoneme written as <ll> was a palatal lateral approximant/ʎ/but in northern Kichwa dialects this phoneme is pronounced as a voiced postalveolar fricative/ʒ/; in these examples, the root transcribed as <illa> is actually pronounced/iʒa/.

3.1. Multimodal Existential Negation with Two Hands

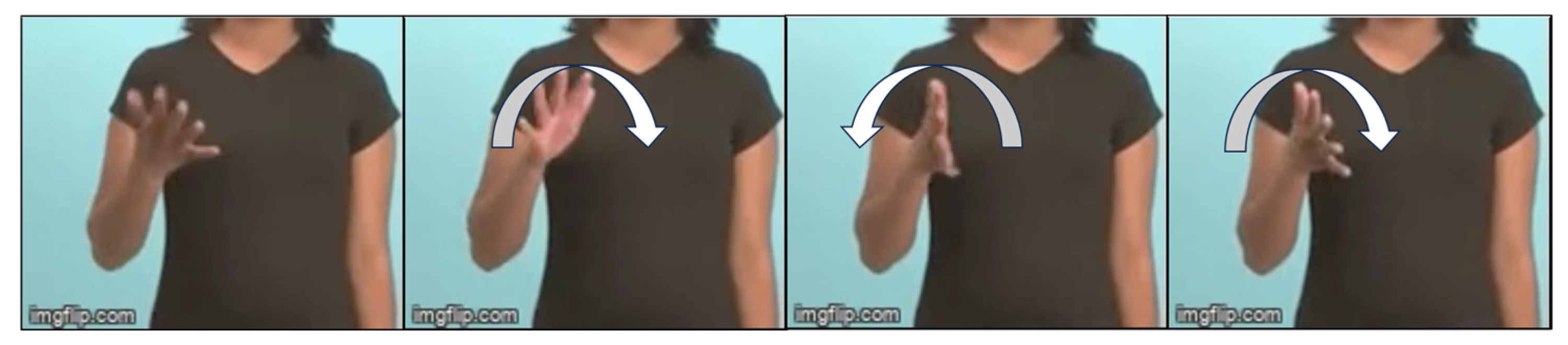

Example (2), from the same recording as (1) above, illustrates an instance of the two-handed variant of VEN, in which the speaker uses a simple form of a verb, without any additional grammatical elements aside from third person. In theory, two-handed VEN might be thought of as a “full” form versus a “reduced” one-handed form, but in practice, one hand is commonly occupied with some other activity, and the one-handed variant appears more frequently in this dataset (12 of the 16 examples located in the corpus). Unlike in (1), in (2), this speaker’s hands are completely free, allowing her to use both of them. Like in (1), the articulation of VEN in (2) is rapid and aligns closely with the verb

illa-.

3![Languages 10 00138 i002 Languages 10 00138 i002]()

| QUSF2016_05_18S2_1298429 |

| (2) | María Nicolasa: | veranu-pi-ka | jiwa-pash | illa-n |

| | | summer-LOC-FOC | grass-also | lack-3 |

| | | In summer there is no grass (for grazing). |

| | | | | ((NEG.EXIST)) |

Example (2) can be considered a typical, simple example of two-handed VEN. Example (3) illustrates another case of a fully articulated, two-handed version of VEN, but this time with a few additional linguistic elements to consider. The context of this conversation is a discussion of the different family names that are present in the local community of Morochos in the Cotacachi region of Imbabura; there used to be members of the Bayu family, but today “there are none” left. The first speaker uses the verb illa- twice without raising his hands, but when he says the phrase “Nothing, nothing, there are none”, ending with the verb illa-, he now raises his two hands and rotates them both simultaneously.

![Languages 10 00138 i003 Languages 10 00138 i003]()

| QUSF2016_04_22S4_1664551 |

| (3) | José: | Bayu | chay, | mayjan-da | Bayu |

| | | Bayu | that | which-ACC | Bayu |

| | | Bayu, that, which Bayu |

| | Miguel: | Illa-n-ma | Bayu-ka, | illa-n-ma |

| | | not.exist-3-EV.DIR | Bayu-FOC | no.exist-3-EV.DIR |

| | | There are no Bayu; there are none |

| | José: | Pay-kuna | ña | illa-n | |

| | | 3-PL | already | not.exist-3 | |

| | | They no longer exist |

| | Miguel: | nima | nima | illa-n-mi | Bayu, Jose Manuel |

| | | nothing | nothing | not.exist-3-EV.DIR | Bayu Jose Manuel |

| | | Nothing, nothing, they don’t exist, Bayu, José Manuel |

| | | ((NEG.EXIST------------)) |

In (3), VEN begins at the word “nothing” and continues throughout its repetition and the verb. There are two elements of spoken language that indicate that the speaker is making his statement somewhat strongly: the repetition of “nothing” and the usage of the grammatical suffix -

mi (sometimes variant -

ma), an affirmative declarative evidential based on information from direct personal experience or other strong “best possible grounds” evidence (

Faller, 2002 on Cuzco Quechua; Quechuan languages feature different variations of the basic Quechuan evidential system; see also

R. Floyd, 1993;

S. Floyd, 2005;

Hintz & Hintz, 2017;

Jimenez Nina, 2022). We can analyze the very prominent and extended two-handed visual expression aligning with these two emphatic spoken elements, as this is the most prominently and lengthily articulated form of the visual practice seen in this data set.

In (4), the visual negative existential is also articulated with two hands, but compared to (3), it is much quicker and not as prominently articulated. The context for this example is an explanation of the medicinal properties of the

chawar mishki (“agave sweet/sugar”) liquid that the speaker and her daughter are extracting from agave plants during the recording. The rapid articulation seen here is most likely related to the way in which the practice occurs, interspersed with a series of iconic gestures that are self- or body-directed in that they use the speaker’s body to talk about others’ selves and bodies (

Cooperrider, 2014;

S. Floyd, 2019), in this case using gestures around the stomach of the speaker in the context of reference to stomach sickness.

![Languages 10 00138 i004 Languages 10 00138 i004]()

| QUSF2016_04_29S1_4631616 |

| (4) Rosa María: | tia-ka | chay | mandado-ta | rura-shpa-ka |

| | woman-FOC | that | order-ACC | do-SR-FOC |

| | The woman, following that order (to drink medicinal liquid) |

| | ña | biksa | junda-y-ka | tuku-ri-shkia |

| | already | stomach | full-N-FOC | happen-REFL-PTCP |

| | when the stomach has already become swollen, |

| | ((gesturing at stomach---------------)) |

| | ña | illa-n | biksa-ka | semana-wan-ga |

| | already | lack-3 | stomach-FOC | week-with-FOC |

| | already (the swelling) was gone within a week. |

| | ((NEG.EXIST---------)) ((gesturing at stomach--)) |

In (4), two-handed iconic gestures occur both before and after the visual negative existential, and so the latter occurs quickly within this sequence, with a rapid articulation that allows the other gestures to continue as the speaker continues describing the medicinal properties of chawar mishki for stomach sickness. Even so, since the speaker’s hands are not otherwise busy, it is possible to use both hands in her expression in this case. As in other examples, the visual practice occurs aligned with the verb illa- but, compared to (3), in (4) the verb does not occur with any evidential morphology, which also may correlate with the more reduced articulation, more like that seen in (2).

As a general rule, the two-handed version of VEN is used by speakers who have both hands free while speaking, which is the case in (2), (3), and (4). This practice appears to interact to some extent with spoken language, since in (3), it has a longer duration that overlaps with emphatic spoken elements like repetition and direct evidential marking. It also can interact with other visual-gestural practices, such as in (4), where it occurs interspersed in a series of iconic, body-directed gestures. So, while these three examples are all instances of a similar practice of VEN, they show slight variation according to discourse context. The next section illustrates further variation by considering one-handed examples of VEN.

3.2. Multimodal Existential Negation with One Hand

For comparison to examples (2) to (4) of two-hand VEN, examples (5) to (9) show cases of the one-handed version of the VEN. For example, in (5), the speaker is discussing her practices as a midwife compared to the practices of Western-style medical doctors in hospitals where there is no medicine or water and where the environment is cold, compared to her warm and cozy birthing room. Before the VEN, her hands are clasped and at rest, and she raises her right hand to precisely coincide with the occurrence of the verb illa- in her spoken discourse, then returns to the clasped position.

![Languages 10 00138 i005 Languages 10 00138 i005]()

| QUSF2016_05_05S1_1660290. |

| (5) Carmen: | jambi-kuna | falta-ju-n, | yaku-kuna | falta-ju-n |

| | medicine-PL | SP:lack-PROG-3 | water-PL | SP:lack-PROG-3 |

| | There is no medicine; there is no water |

| | kunu-chi-na | falta-ju-n |

| | heat-CAUS-N | SP:lack-PROG-3 |

| | There is no heating. |

| | uu | kay-pi-ka | chay-kuna-ka | illa-n |

| | oh | here-LOC-FOC | that-PL-FOC | lack-3 |

| | Oh, here we don’t have those here. | ((NEG.EXIST--)) |

Interestingly, the Spanish borrowing falta, “to lack”, roughly equivalent to Kichwa illa-, occurs twice with Kichwa morphology just before the verb illa-, but this Spanish near-synonym does not co-occur with VEN in either case. It may be the case that the pairing of illa- with this visual practice is not as conventionalized as with Spanish-origin falta-, a Spanish borrowing that may not be part of a common conventional multimodal combination for Kichwa speakers compared to their native verb. In this case, like in (3) and (4), the verb illa- does not take any additional suffixes (e.g., evidential), and the articulation is rapid and synchronized to the verb, as was also seen in those cases. It is unclear what factor may influence the choice of a one-handed articulation; the fact that the speaker’s hands move out of and then quickly back into a stable, resting, clasped position in the speaker’s lap may be relevant.

In (6), we see another one-handed variant of VEN. While here, the verb illa- takes an affirmative evidential suffix -ma, which we saw associated with the emphatic multimodal expression in (2). However, while here, the left hand is raised and articulated prominently; the right hand is being used to sustain the speaker’s weight since she is leaning on an object as they converse. This provides a likely explanation in this case for why the right hand was not employed (the speaker is not left-handed). This is also the only example in this data set of one-handed VEN in which the left hand was used; the right hand appears to be dominant in most cases.

![Languages 10 00138 i006 Languages 10 00138 i006]()

| QUSF2015_12_03S7_2496086 |

| (6) | Luzmila: | ña-kuti | chay-shuk | col | seda | ni-shka-ka |

| | | already-again | that-one | cabbage | silk | say-PTCP-FOC |

| | | Again, that other cabbage, “silk” it is called, |

| | | yanga, | seda-pa-lla-ta | illa-n-ma |

| | | common | silk-POSS-LIM-ACC | lack-N-EV.DIR |

| | | so, there is no “silk” (cabbage). | ((NEG.EXIST--)) |

Has she used her right hand, or both hands, the speaker in (6) would have had to change her entire posture, so the simultaneous usage of one hand appears to explain to some extent the usage of the other. However, opting for the non-dominant hand and raising it up to mid-torso level suggests that the expression is part of the “foregrounded” communication and not just “background” processing (

Cooperrider, 2017). A related analysis can be provided for example (7) because in that case, the speaker is holding a thermos of tea in his left hand, so he uses his right hand only in order to articulate VEN. In this case, the verb

illa- is used with a habitual marker that appears to be unique to the Imbabura variety of Kichwa (although many other varieties remain largely unstudied, so it may occur elsewhere).

![Languages 10 00138 i007 Languages 10 00138 i007]()

| QUSF2016_05_18S2_1844053 |

| (7) | Antonio: | chay | tiempo-ka |

| | | that | time-FOC |

| | In those times |

| | | kay | ciencia | cientifico-ka |

| | | this | science | scientist-FOC |

| | these sciences, scientists |

| | illa-kariyan | na-chu |

| | lack-HAB | no-Q |

| | did not exist, right? |

| | ((NEG.EXIST--)) |

The final two examples of one-handed VEN in this section are from interviews dealing with meaningful cultural topics involving ethnic identity and local spirituality. Like in (5), the speakers in (8) and (9) could potentially have used both hands, as they are not holding onto any objects as in (6) and (7). This fact shows that the choice of one-handed versus two-handed VEN, while influenced by the usage of a hand for a simultaneous practical purpose, is not entirely determined by this factor and instead is sensitive to several other factors, including individual expressive choices and issues of discourse context. This does not mean that the choice is random but reflects the fact that the hands are multi-functional and may be enlisted for many different activities simultaneously in addition to visual/gestural expression, so many that it is impossible to predict or exhaustively describe all the possible combinations of activities.

In example (8), the speaker is describing cultural differences between the two major ethnic groups that speak Imbabura Kichwa: the Otavaleños, including Otavalo, southern San Pablo Lake, Cotacachi, and adjacent areas, and the Cayambis, including southern San Pablo Lake, Caranqui, Zuleta, and adjacent areas, as well as northern Pichincha province around the city of Cayambe. While the linguistic distinctions between these two areas are not abrupt but rather constitute a dialect continuum, there are several cultural signifiers that are more binary, including forms of traditional dress. Each town has its own specific variant of traditional dress, but in general, Otavaleño and Cayambi clothing can be distinguished by several distinctive features; for example, Otavaleña women use anaco skirts (bolts of cloth sustained by chumbi woven belts) and cloth headdresses while Cayambi women use pleated skirts and hats, and so on. Men’s dress also patterns distinctly between these two regions, notably in terms of hairstyle. Otavaleño men generally wear their hair long in a braid, while Cayambi men tend to cut their hair short. This is the topic of discussion in example (8), where the speaker, from the Cayambi ethnic group, mentions that although both groups are indigenous, one difference is that Otavaleños wear their hair long, while Cayambis wear their hair short.

![Languages 10 00138 i008 Languages 10 00138 i008]()

| QUSF2016_05_13S2_2328663 |

| (8) | Juan: | pero | tukuy-pi | iguala-ri-n-lla | iguala-ri-ta-ka |

| | | but | all-LOC | equal-REFL-3-LIM | equal-RFL-ACC-FOC |

| | | but in all things we resemble each other, resembling each other, |

| | | unico | akcha |

illa-y-manda |

| | | only | hair | lack-N-from |

| | | (we are) only (different) due to lack of hair |

| | | | ((NEG.EXIST--)) |

| | María: | muchu |

| | | cut.off |

| | | cut off |

| | Juan: | pero | tukuy-lla-ta | runa | pura | karin |

| | | but | all-LIM-ACC | indigenous | among | at.least |

| | | but in everything at least we are all indigenous people |

The VEN in example (8) is articulated with one hand in a notable orientation upwards toward the head, which may also have an indexical dimension, since the topic of speech is hair. This may be part of the motivation for the usage of just one hand, and it is also relevant that in the discourse before and after this example, the speaker is articulating many other types of gestures only with the right hand, with the left hand continuously resting and inactive on his leg. Linguistically, the spoken element of this example is a nominalized instance of the verb illa-, illustrating how VEN can combine with both finite and non-finite verbs.

Another one-handed example of VEN, example (9) features a culturally meaningful explanation of an important element of Andean spirituality: the perspective that mountains are powerful deities that are similar to humans in that they have personalities and gender. Andean peoples have long been known for attributing qualities of personhood to prominent mountain peaks, documented as far back as the early colonial Quechua manuscript from Huarochirí, which tells of the mountain deity Para Caca (

Taylor, 2006). In Andean Kichwa-speaking society, mountain deities are often considered to be part of dualistic pairs of male and female mountains (e.g.,

Lyons, 1999), and in the Province of Imbabura, the two main mountain deities are the male Taita Imbabura (Father Imbabura) and the female Mana Cotacachi (Mother Cotacachi) (

Chávez, 1989;

McDowell, 2019); sometimes this pair is also known as

Jari Rasu, “male snow”, and

Warmi Rasu, “female snow”. In example (9), the speaker performs VEN with his right hand elevated in an indexical indication of the Imbabura Volcano in front of him.

![Languages 10 00138 i009 Languages 10 00138 i009]()

| QUSF2016_05_06S1_1643280 |

| (9) | José Carlos: | Imbabura | Tayta-ka |

| | Imbabura | father-FOC |

| | Father Imbabura |

| | Simeon: | Ari |

| | | yes |

| | José Carlos: | Mm, | ima-shna-ka, | ñukachik-pa-ka, | ah |

| | | mm | what-like-FOC | 1PL-POSS | ah |

| | | Mm, what is it like? For us, ah |

| | pay-ka | asha | killa-gu | ka-pa-n |

| | 3-FOC | a.little | lazy-DIM | be-HON-3 |

| | He is a little lazy. |

| | Simeon: | Ari |

| | | yes |

| | José Carlos: | puñu-y | siki | ka-pa-n |

| | | sleep-N | ass | be-HON-3 |

| | | He is very sleepy. |

| | Simeon: | Ah cierto? |

| | Ah really? |

| | José Carlos: | chay-manda-mi | pay-ka | pay-pa-ka | illa-n, |

| | | that-from-EV.DIR | 3-FOC | 3-POSS-FOC | lack-3 |

| | | That is why he, for him, there is no (water). | ((NEG.EXIST--)) |

| | | casi | na | yapa | tiya-n, | ima-pash |

| | | almost | NEG | extra | exist-3 | what-also |

| | | there is not much additional (water) of any kind. |

In example (9), the speaker contrasts Mother Cotacachi, who provides a lot of water to surrounding communities, with Father Imbabura, who provides fewer sources of water, thus being “lazy” and “sleepy”. Even more clearly than in (8), in (9) VEN is articulated together with an indexical pointing gesture, the speaker indicating the Imbabura Volcano that he is referring to both with the angle of his hand and the direction of his gaze while he uses this same hand to articulate the VEN. In this case, this indexical element of the multimodal expression provides some motivation for a one-handed articulation of VEN.

Considering the one-handed cases of VEN in examples (5) to (9), there are a number of different factors that interact with this practice. These include the following: right-handed dominance; speakers using their other hand for practical activities; and the other types of gesture that occur before, after, and simultaneously with VEN, including indexical pointing in which existential negation is oriented towards a specific referent in space (

see Kita, 2003). Rice also finds that VEN is more frequent with one hand than with two in Amazonian Kichwa and also discusses several factors that may influence the usage of one or two hands, including cases where speakers are holding an object in the other hand (

Rice, 2022, p. 43). In all the Imbabura Kichwa examples shown up to this point, both two-handed and one-handed VEN are closely aligned to the verb

illa- in several different kinds of morphosyntactic configurations. In contrast, the next section looks at a couple of cases where VEN occurs with other linguistic forms or with no spoken material.

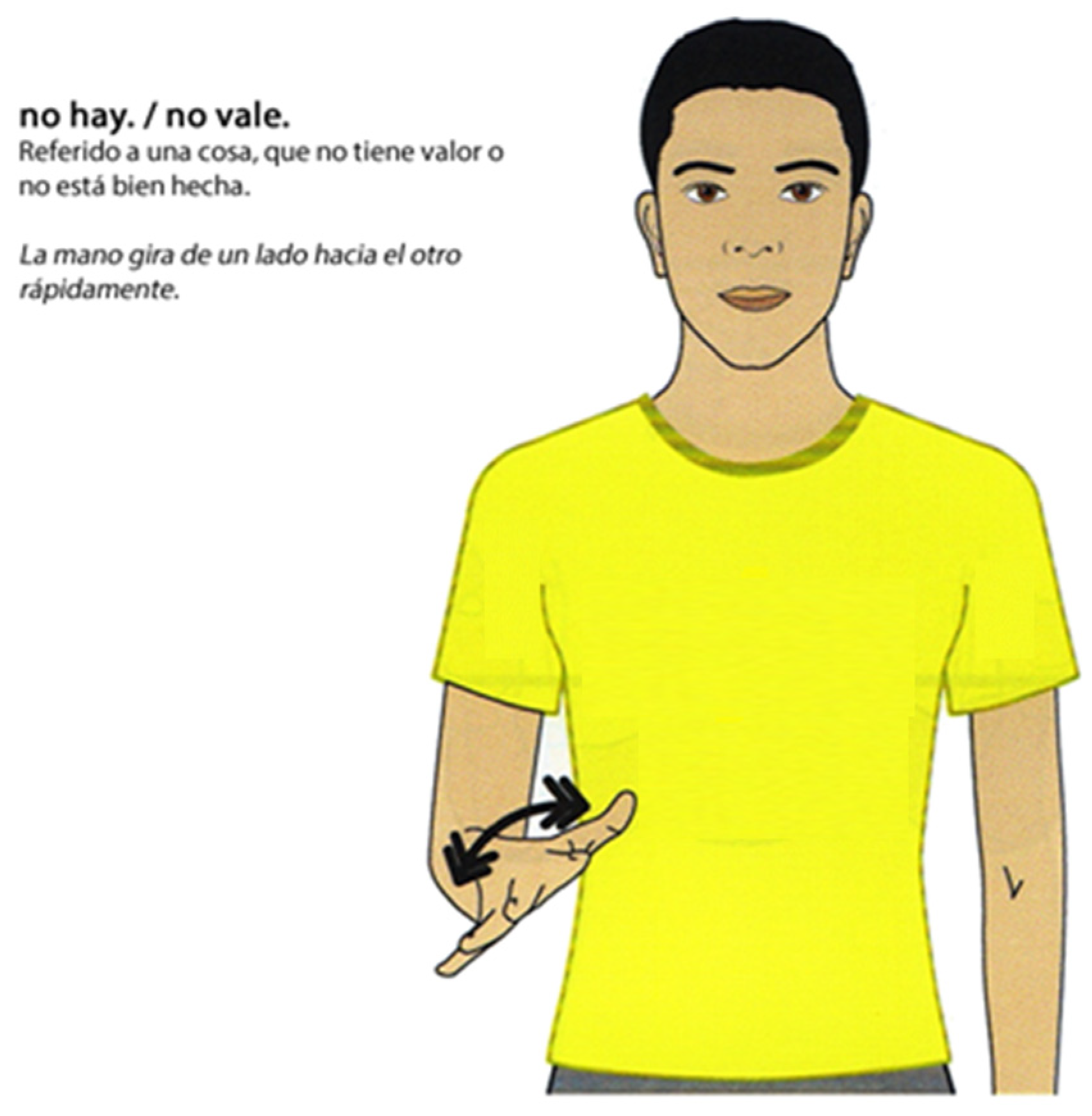

3.3. Visual Existential Negation Without the Verb Illa-

In two cases in the data set, VEN occurs without the verb illa-, once with a different verb and once without any spoken elements at all. While this phenomenon may sometimes go undetected in transcribed video data because examples cannot be easily located by looking at the video where the verb illa-occurs, a careful review of data samples suggests that it is very rare in Imbabura Kichwa discourse for VEN to occur without this verb, as these were the only two examples attested in the data set. In example (11), a two-handed articulation of VEN occurs together with the phrase “nothing, nobody” in a narrative about a man running from what appeared to be a ghost.

![Languages 10 00138 i010 Languages 10 00138 i010]()

| QUSF2016_05_13S1_2508779 |

| (10) | María: | chay-kuna | ishtanku-kuna-pi | wagta-ju-shka | nin | pungu-ta |

| | | that-PL | cantina-PL-LOC | hit-PROG-PTCP | EV.REP | door-ACC |

| | | There in the cantinas he was knocking on the doors |

| | ashta | tarak | tarak, | nima | nadie |

| | hasta | IDEO | IDEO | nothing | nobody |

| | until it sounded “tarak tarak” (but there was) nothing, nobody. |

| | | ((NEG.EXIST-------)) |

Example (10) shows that it is indeed possible for Imbabura Kichwa speakers to express VEN in combination with spoken material other than the verb illa-, here with the word nima or “nothing”. However, a review of the data set checking other cases of “nothing” and phrases like “there are none” (mana tiyanchu) and similar could not locate many other examples with these types of elements. There are probably a few more such cases to be found in the data, but they appear to be rare, and some are not as clear-cut instances as those seen in this study, where examples were chosen based on their clarity.

Finally, there are a few cases in which VEN can occur with no accompanying spoken material at all. In example (11), a woman is eating a snack, and her mouth is full just as the researcher asks her a question, inquiring whether a species of bird, present in the cattle pastures where the recording was made, has a name in Kichwa; it turned out to be easier to answer that there was no name with only visual expression, since the speaker was still chewing at the moment.

![Languages 10 00138 i011 Languages 10 00138 i011]()

| QUSF2018_06_11S1_464000 |

| (11) | Simeon: | shuti-ta | chari-n kichwa | shimi-pi |

| | name-ACC | have-3 kichwa | language-LOC |

| | Do they have a name in Kichwa, |

| | chay | yurak | pishku-kuna |

| | that | white | bird-PL |

| | those white birds? |

| | Ursula: | ((NEG.EXIST---)) |

The form of example (11) can be analyzed as being motivated by a number of factors, including the fact that the speaker is chewing with her mouth and holding onto a bag of food with her left hand, resulting in a one-handed articulation with no spoken material at all. Typical of emblematic or symbolic visual expressions, the conventionalization of the meaning of VEN allows it to stand as a full conversational turn on its own under these circumstances.