1. Introduction

The diachronic study of the 20th century was consolidated as a research field ten years after the label was first proposed in Peninsular Spanish (henceforth, PS) (

Pons Bordería, 2014). This is supported by the recent publication of some works addressing language changes developed throughout the 20th century in different languages (see

Fedriani & Molinelli, 2024;

Ghezzi, 2024 for Italian;

Maldonado, 2024;

Mihatsch & Vazeilles, 2024 for Argentinian and Mexican Spanish;

Schneider, 2024 for French;

Soares da Silva, 2024 for Brazilian Portuguese, among others). Most of these works have shown that register and genre are two key variables for language change (

Biber & Gray, 2013) since they can trigger or even diffuse some developments (

Llopis-Cardona, 2022;

Llopis-Cardona & Pons Bordería, 2020).

Colloquialization is a language change process involving a shift towards a more spoken style of language in oral or written formal discourses where informality is not expected (

Biber & Finegan, 1989;

Farrelly & Seoane, 2012), such as in mass-media specialized discourses (

Hua-Kuo, 2007;

Brandimonte, 2021). Thus, register and genre are involved. Recent works have addressed mass-media colloquialization in PS on TV and radio interviews, magazines, or talk shows (

Cuenca, 2013;

Briz, 2013;

Martínez Costa & Herrera, 2021;

López Serena, 2014). Research in PS commonly assumes that colloquialization is a completed change, without focusing on the stages by which formal discourses have been transformed into less formal discourses, which results from the lack of oral recordings from the 20th century (

Enghels & Roels, 2024;

Pons Bordería, 2024). Thus, no systematic, diachronic approaches have been proposed yet, especially for oral mass-media genres (e.g., news, debates, or sports-announcing, among others).

This paper explores colloquialization as a language change process in one specific oral genre from PS mass-media: football-match broadcasts, which are part of sports-announcing (

Ferguson, 1983,

1985). As this is a specialized oral genre, a correlation between linguistic features and a high degree of formality would be expected over the decades. However, previous works suggest changes in prosodic, lexical, and pragmatic features, leading to a transformation into a more informal, immediate broadcasting model (

Salameh, 2024a). In particular, certain lexical uses (e.g., nouns, adverbs, adjectives, verbs, or discourse markers) reveal a reduction in technical jargon in the linguistic description, incorporating neutral and colloquial words at various stages of the match (i.e., the opening, closing, and even some moments of the narration) (

Salameh, 2024b). This lexical transformation does not make broadcasts equivalent to colloquial conversations, as they are constrained by the features of the specialized genre they belong to, but there is a significant difference compared to the first oral football match broadcasts, which were more linguistically formal and distant to the audience (

López Serena, 2014), suggesting a shift in their discourse tradition (

Kabatek, 2018).

The main purpose of the paper is to provide a more nuanced analysis of a specific class that reflects the trend of colloquialization in the latter half of the 20th century: discourse markers (henceforth, DMs). This approach to analyzing colloquialization processes has not been yet explored in PS, and only a limited number of studies have addressed this type of change in other languages (

Tottie, 2017). Around 1990, an increased use of new DMs was observed in football match broadcasts (

Salameh, 2024b). Broadcasters began to introduce DMs associated with spoken language (e.g.,

o sea,

bueno,

mira, etc.), replacing certain formal discourse markers used in earlier oral broadcasts, which were related to a higher degree of discourse planning (e.g.,

sin embargo,

no obstante). This shift in the use of DMs aligns with the lexical changes in conceptual words mentioned above.

Thus, the main hypothesis to be checked is that DMs serve as a parameter for measuring colloquialization. The type and frequency of DMs in PS football announcing will demonstrate how broadcasters adopted features of spoken language in a specialized oral genre that previously did not exhibit them. To explore this, a manually compiled dataset of football matches from 1980 to 2000 and from 2000 to 2024 was transcribed and analyzed. All recordings in this corpus were retrieved from YouTube, as well as from the main websites of national radio and TV channels in Spain. To focus on specific processes decade by decade, a selection of excerpts from transcribed matches has been made. The results show a clear consolidation of the use of spoken language DMs by sports announcers.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The 20th Century as a Novel Space for Language Change

From a diachronic perspective, the 20th century represents the stage where linguistic developments coming from the 19th century seem to have fully consolidated (e.g., the development of some discourse markers;

Traugott, 2022; the consolidation of new syntactic patterns,

Garachana, 2021; or the transformation of discourse genres;

Pérez Salazar, 2004). However, the study of this century also provides a novel space to analyze how language use in the 1960s, the 1970s, or even the 1990s differs from current uses. Thus, the 20th century should not only be considered “the end of the road” in historical terms but also the trigger of new linguistic changes that have evolved more rapidly than those of previous centuries. These changes can be intuitively observed in public mass media discourses and private interaction, through different linguistic features (syntax, constructions, vocabulary, pragmatic uses, prosodic features, etc.).

As previously pointed out by

Pons Bordería (

2024), the 20th century presents relevant features, making it a linguistically significant period. All these features can be classified as written- or spoken-related. Firstly, full literacy was achieved in Western societies during this century, leading to an increase in the number of writers and active readers, a process that reached its peak around the 1980s in combination with greater access to higher education, especially during the second half of the century. As a result, people were able to produce and comprehend more complex texts, which also contributed to the development of new textual genres. However, this led, in turn, to an excess of written data requiring a careful selection of materials and the implementation of new quantitative methods to analyze them.

Likewise, the arrival of tape recordings ca. 1970 involved a change in the way language was addressed, allowing for the analysis of orality from its main source: the speakers. The obtention of these recordings is not easy, but the existence of such oral data is key in developing new diachronic research: scholars are now trying ways to retrieve them. Together with real recordings, the role of mass media (radio, TV, movies) is relevant throughout the 20th century in different decades: they had a big impact on population and contributed to spreading language uses, speaking models, etc. They are a different type of oral material complementing real spoken recordings, so their recording and storage is needed for a complete view of the diachrony of this century. Since mass media are public discourses, they host processes such as colloquialization, mainly developed during the last thirty years of the 20th century.

Several research questions arise from these key developments of the 20th century, such as how new textual genres emerged and evolved over the decades from the theoretical framework of discourse traditions (henceforth, DT;

Kabatek, 2018). Additionally, some hypotheses on what private written texts reveal about individuals’ education levels or the degree of orality involved can be proposed (

Pardo Llibrer, 2025). Regarding spoken language, research can focus on the schemas people employed in everyday interactions, the features behind their colloquial language, and, thus, the differences they show compared to present-day colloquial interaction. Studies in mass media could examine the role of speakers in broadcasting, the extent to which they influence audiences, or whether they contribute to language change through diffusion processes. Lastly, mass-media oral recordings provide material to analyze how colloquialization has been produced in public discourses (

Morcillo, in press).

Further research questions and hypotheses to be pointed out still regarding the evolution of language throughout the 20th century, along with the development of additional programmatic proposals. This probably results from the difficulty obtaining certain types of data from this period, particularly from the early decades or from oral-related data. However, some recent studies have overcome these challenges, providing new insights into linguistic evolutions during the 20th century in different languages. Their findings focus on the development and use of discourse markers (e.g., the use of spoken discourse markers in written genres, such as journalistic writing;

Rühlemann & Hilpert, 2017), changes in lexical frequencies (e.g., the increase of more colloquial terms in formal contexts such as parliamentary discourses;

Hiltunen et al., 2020), new address terms (e.g., the change from bestial terms undergoing personal address terms in colloquial conversation;

Maldonado, 2024; and competition and diffusion of vocatives and discourse markers;

Pons Bordería, 2024), among other phenomena. All these works have either exploited new data sources previously unexplored or applied a new diachronic perspective to well-established data sources (see also

Section 3.1).

As observed, most studies examine language changes related to diaphasic variation (i.e., registers and genres), in line with the relevance of language variation as a topic in the 20th century (e.g., some research has focused on language diffusion and geographic factors;

Ito & Tagliamonte, 2003;

Nerbonne, 2009; other studies have examined sociolectal factors such as gender or age contributing to language change;

Enghels & Roels, 2024). This paper also explores language changes associated with registers and genres, particularly colloquialization processes.

2.2. Colloquialization and Language Change

The relationship between language change, register, and genres has been extensively explored in recent decades, with a particular focus on how formality and informality shape language use in spoken and written discourses (

Nevalainen & Traugott, 2012). A phenomenon associated with register transformations is

colloquialization, experienced by PS and other romance languages during the last twenty-five years of the 20th century (

Pons Bordería, 2014;

Fedriani & Molinelli, 2024;

Salameh, 2024a). Colloquialization involves an increased degree of informality in genres traditionally expected to be more formal. This change is achieved through the incorporation of everyday topics, proximity between speakers, a reduction of asymmetries, etc., in both public and private communication (

Biber & Finegan, 1989).

Definitions of colloquialization vary depending on the approach adopted (

Salameh, 2024a, p. 23): On the one hand, some scholars define it as “the incorporation of more speech-like habits in language production” (

Schützler, 2020, p. 2) within “written discourses,” including essays, prose, plays, etc. (

Farrelly & Seoane, 2012, p. 394). On the other hand, others describe colloquialization as a process in which informal features are included into formal, planned discourses, whether written or spoken, such as radio talk-shows, interviews, or public/political speeches (see

Reber, 2021;

Brandimonte, 2021;

Morcillo, in press). The first approach adopts a narrower focus, emphasizing the transformation of written texts through the integration of oral features. In contrast, the second approach offers a broader view, as colloquialization can occur across various registers and genres beyond the traditional written-spoken dichotomy.

Colloquialization can be tracked diachronically by examining changes in discourses over specific time spans (e.g., from 1920 to 1940, from 1960 to 1980, etc.) (

Hiltunen et al., 2020). Recent studies on Romance languages have approached colloquialization as an ongoing process rather than the final stage of a linguistic change. This perspective contrasts with earlier works that assumed colloquialization as an endpoint, without analyzing how originally formal discourses evolve toward greater informality or colloquiality (

Porroche, 2009): for instance, political TV-tertulia have included closer interactions between interviewers and guests, as evidenced by the presence of interruptions, hesitations, or new address terms (

Briz, 2013;

Cuenca, 2013). This change is a fact and can even be observed in other genres (e.g., parliamentary debates, news broadcasts, radio programs, interview podcasts, etc.). However, there are no conclusive data revealing how the transition to a more colloquial setting has occurred, probably due to the scarcity of oral data recordings from the 20th century (see

Section 3.1 for further details).

Despite the lack of data, some studies have described colloquialization processes in the 20th century through a set of linguistic parameters, primarily focusing on linguistic items specifically associated with the increasing colloquiality in formal discourses. Their data sources include various general corpora as well as particular, individually retrieved corpora, particularly for the study of orality. The following new findings open new ways for further research on colloquialization:

- -

The incorporation of speech like verbal forms/constructions in formal speeches (e.g., En. “I think,” “is going to,” “I believe,” etc. in parliamentary discourse;

Hiltunen et al., 2020; Sp. “yo creo,” “yo digo” in football broadcasts; Author, 2024; Fr. “J’imagine”;

Schneider, 2024).

- -

- -

The incorporation of informal-like nouns and adjectives in formal discourses in which their use was not expected (e.g., En. “fucking + noun” in humor texts;

Zhu & Deng, 2023).

- -

The employment of new nominal treatment forms/vocatives in colloquial, spoken interaction and formal speech discourses, such as interviews or debates (e.g., Sp. “churri,” “nene-na,” “perra”;

Sanmartín, 2024; Sp. “tío/a” and “macho/a”;

Llopis-Cardona & Pons Bordería, 2020;

Pons Bordería, 2024; Mex. Sp. “cabrón” and “buey”;

Maldonado, 2024; Sp. vocatives + diminutive;

Cuenca, 2013).

- -

Overlaps and interruptions between speakers in formal contexts, such as parliamentary discourses or debates (

Morcillo, in press).

Lastly, another parameter unveiling colloquialization is the presence of spoken, oral discourse markers in formal discourses, both written and oral. The relationship between discourse markers and colloquialization is developed in the following section, as it constitutes the basis of the analysis proposed in this paper.

2.3. Discourse Markers and Colloquialization Processes

Discourse markers (henceforth, DMs) are a functional word category related to other closer categories such as discourse particles (henceforth, DPs) or connectives, which constitute a consolidated research field in pragmatics and discourse analysis, as supported by the large amount of works published during the last forty years, especially since the 1990s (

Zwicky, 1985;

Bazzanella, 1986;

Schiffrin, 1987;

Fraser, 2009;

Portolés, 2001;

Loureda & Acín, 2010,

Borreguero & López Serena, 2010, to name but a few).

DMs are procedural items that give instructions on how speakers and hearers must process the discourses they produce and receive (

Hansen, 2006, p. 25). DMs are polyfunctional, as they operate through different discourse levels depending on the semantic-pragmatic context in which they appear (

Schiffrin, 2015, p. 62;

Bazzanella et al., 2007, p. 10) and show different functions, mainly textual, modal, or interactive, such as highlighting cohesion, coherence, and structuration of texts, the way speakers catch hearer’s attention, turn-giving work, or mitigation processes (

Pons Bordería, 2006, pp. 86–87;

Briz & Hidalgo Navarro, 1998, p. 123). Last, as a category, DMs are also related to more general categories, such as DPs (see

Briz et al., 2008;

Santos Río, 2003), but not every DP can be classified as a DM (e.g., particles; Sp. “como,” En. “like,” adverbs; Sp. “a lo mejor" En. “perhaps,” “maybe”; focus particles, Sp. “incluso,” En. “even” are not DMs but DPs).

Descriptions of DMs have also addressed their use depending on register and genres (see

Schourup, 1999;

Pons Bordería, 1998): recent quantitative studies confirm that spoken, colloquial interaction tends to cover textual, modal, and interactive functions (topic start, open and close marks, intensification, approximation, mitigation) in a very balanced way, which means a high frequency of some specific DMs (e.g., Sp. “pues,” “bueno,” “¿no?”; En. “well,” “I mean,” etc.). By contrast, formal register shows a prevalence of textual (addition, contrast) over modal and interactive functions (back-to-topic, formulation, etc.), usually expressed by written-like DMs (e.g., Sp. “es decir,” “no obstante”; En. “however,” “nevertheless,” “notwithstanding this,” etc.), both in spoken and especially written texts (

Pons Bordería et al., 2023;

Pons Bordería & Salameh, 2024, p. 301).

The study of trends of using DMs through different registers across genres allows for more nuanced analyses, especially when dealing with language change processes such as colloquialization: the type and functions of the DMs employed in spoken conversations works as a paradigm to be compared with so as to check whether other different genres present the same or similar uses of DMs as spoken conversations, in order to measure the development of spoken-like patterns in their structure (e.g., an increase in DMs commonly employed in colloquial conversations in interviews, debates, and broadcasts, which are formal-related discourses, could unveil a colloquialization process in progress etc.). Changes in DMs are not the only feature suggesting colloquialization, but their combination with other linguistic properties (i.e., new lexical uses, presence of discourse planning marks, such as hesitations or formulation marks, etc.) is a key indicator for language change.

The relationship between colloquialization and DMs has not been yet exhaustively explored, but some authors suggest that changes in their use are related to colloquialization processes. Specifically, the reduction of formal DMs in planned discourses so as to integrate spoken-like DMs leads to a loss of distance (e.g., the use of DMs such as “um” or “uh” in journalistic texts;

Tottie, 2017; inserts with “well” in journalistic writing;

Rühlemann & Hilpert, 2017; uses of Sp. “pues” or the discourse particle “pues eso” in journalistic texts or literature;

Salameh, 2023, to name but a few). This integration of spoken-like DMs may also serve as a strategy to imitate orality in written, planned discourses, making it appear more immediate to readers (

López Serena, 2014).

TV and radio broadcasts constitute a case of colloquialization, in line with other oral discursive genres also colloquialized (i.e., interviews, news, tertulia, debate, etc.). Their colloquialization can be related to the use of spoken DMs, specifically for football broadcasting. Football broadcasts have been colloquialized in PS and other languages (see different degrees of formality/informality in German;

Meier-Vieracker, 2021; in English,

Lewandowski, 2012). Initial broadcasts, more planned and formal throughout the whole match (starting part, first half, second half, and closing;

Salameh, 2024b), were transformed into closer, friendly discourses to catch more audience. This change, detected in TV since ca. the 1990s, seems to be related to external triggers, such as the incorporation of further speakers or new technological developments, namely more cameras in stadiums, as well as the influence of radio broadcasting models. Linguistically, the colloquialization of football broadcasts still belonging to specialized journalistic discourses can be measured through specific items and mechanisms (e.g., a change from technical lexical forms to neutral lexical words, the use of interactive mechanisms such as formulations or reformulations, changes in the speed, etc.;

Salameh, 2024a). DMs, thus, could also be another colloquialization parameter, specifically the use of spoken-like DMs commonly employed in spoken, colloquial interaction.

2.4. Football Broadcasts in Peninsular Spanish: An Overview

Football (specifically, soccer) holds significant relevance in mass media, as evidenced by current high audience ratings in TV and radio programs, as well as the strong representativity of this sport in newspapers (

García-del-Barrio & Pujol, 2007, p. 99). Understanding soccer’s major role in society requires some knowledge on how its presence in mass media progressively increased during the second half of the 20th century.

- -

First football programs and broadcasts emerged in Spain around the 1940s and gained popularity in the 1950s on national radio stations such as Cadena Ser, Radio television Española and Cadena Cope. TV broadcasts began in the late 1960s, but audiences commonly followed football matches by simultaneously watching TV coverage while listening to radio comments, a sort of tradition that has been preserved among older generations.

- -

TV broadcasts expanded in the 1980s, particularly when Spain hosted the FIFA soccer world cup. New broadcasting technologies were introduced, leading to substantial improvements in live commentary and a change in the descriptive dynamics adopted by speakers, showing some similarities to radio programs (

Salameh, 2024b).

- -

This transformation grew later and contributed to the success of football match broadcasts on TV since the 1990s, when new private and regional channels acquired broadcasting rights (e.g., Catalan Television, Valencian Television, and, notably, the private channel CANAL+).

Football broadcasts have been analyzed in various languages (e.g., English, German, etc.;

Naveed & Umar, 2021;

Meier-Vieracker, 2021, etc.). In Peninsular Spanish, contemporary football broadcasts adopt a less formal narrative style detected through contextual and linguistic properties:

- -

Sentences are simpler in their lexical structure, in contrast to early broadcasts, which predominantly featured highly formal, lexical structures to describe match events (

Reigosa et al., 1994, p. 22): for example, more complex verbal choices were progressively simplified (e.g., from Sp. “se asocia con” or “cede para” has been substituted by “pasa a”; even the mention of each player is enough to understand what is happening since images complete narration).

- -

The use of short lexical uses is also related to faster descriptions in relevant actions (e.g., a goal or a goalkeeper save, the development of a long play which can be crucial in the match vs. the beginning of a play) (

Rodero, 2005). Structures are substantive-based also to contribute to these fast descriptions (for further details, see

Hernández Alonso, 2012).

- -

The presence of three or more announcers per match creates a more conversational, friendly atmosphere, allowing for colloquial language use at different moments throughout the event. Announcers are not only specialized sports journalists but also former football players who offer their unique insights based on their firsthand playing experience, but by adopting a less technical narrative model. Radio explores this model in depth, showing even more overlaps because more people are broadcasting the match.

These changes towards a bigger immediacy do not involve broadcasts being equivalent to spontaneous conversation; however, the incorporation of features commonly found in spoken conversation seems to lead to a transformation in the DT linked to football broadcasting. This linguistic change may also be influenced by changes in an announcer’s style over time: for instance, early announcers such as Vicente Garrido, Joaquín Prat, and Bobby DeGlané followed more classical broadcasting models, which shifted with the emergence of new, younger announcers like José María García. In turn, current announcers such as Carlos Martínez, Miguel Ángel Román, and Paco González differ notably from José María García (

Salameh, 2024a). Their differences depend on their individual styles but may also be influenced by their age or the era in which they were broadcasting (e.g., 1960s, 1990s, 2020s). Together with linguistic features, technical developments in sports broadcasts must also be considered: the presence of additional cameras, microphones, and broadcast zones leads to a more complete experience in which each action in every match could be described in more detail compared to the first decades without repetitions and offline information (see

Salameh, 2024b).

As introduced in the paper, the use of spoken related DMs is one of the linguistic devices contributing to an increase of immediacy in broadcasts, as shown in the following example:

| (1) | Locutor 1: Ahí está el Valencia/con su capitán Gaizka Mendieta/un hombre quee/en el Valencia/Michael/está a las buenas y a las malas cuando todo va bien es porque Mendieta funciona y cuando se tropieza parece que también es porque Mendieta deja de funcionar/pero es quee/tampoco se puede estar al cien por cien siempre/¿no? |

| | Locutor 2: Mendieta jugando mal sigue jugando bien/hay ciertos futbolistas que no saben qué es jugar mal/pueden tener días no tan brillantes como otros/pero Gaizka Mendieta siendo indiferente en su juego sigue siendo muy buen jugador/desde luego prefiero tener- tenerlo en mi equipo en vez de en mi contra/¿eh? |

| | L1: pues ahí está Gaizka Mendieta saludando al trio arbitral/Undiano Mallenco/uno de los colegiados/con no demasiada experiencia/joven/en el- en la primera división del que qué podemos apuntar/Joaquín Ramo Marco/buenas tardes |

| | Locutor 3: Hola/Carlos/buenas tardes/saludos/bueno/decir/ya lo has dicho tú todo/es el árbitro más joven de esta categoría/veintinueve años/no está el horno para bollos/¿no?/pero decir que hoy tiene ante sí un partido (…) |

| | Valencia C.F. vs. Real Madrid (2000/2001, Canal+, Spain) |

| | Announcer 1: Here we have the Valencia Football Club, with their captain Gaizka Mendieta/a man whoo/at Valencia/Michael/is there through thick and thin. When things are going well, it is because Mendieta is on form, and when the team stumbles, it also seems like it is because Mendieta stops performing. But you know, you can’t always be at one hundred percent, right? |

| | Announcer 2: Even when Mendieta plays badly, he still plays well/There are some players who just do not know what it means to play badly/they might have fewer brilliant days than others/but Gaizka Mendieta, even when he seems indifferent on the pitch, is still a very good player. Honestly, I would rather have him on my team than against me, huh? |

| | Announcer 1: Well, there’s Gaizka Mendieta greeting the referee trio/Undiano Mallenco, one of the officials/without too much experience/young, in the-in the in the first division. What can we say about him, Joaquín Ramo Marco? Good afternoon. |

| | Announcer 3: Hi, Carlos, good afternoon, greetings. Well, you’ve pretty much said it all. He is the youngest referee in this league/twenty-nine years old. It is not exactly smooth sailing, is it? But today he has a big match ahead of him… |

| | Valencia C.F. vs. Real Madrid (2000/2001, Canal+, Spain) |

Example (1) introduces the use of some spoken-like DMs in Peninsular Spanish (e.g.,

¿no?,

¿eh?,

pues, or

bueno) during an interaction describing some basic information about the match and the players. This way of interacting shows one of the major transformations regarding the first TV football broadcasts, already triggered in the 1990s: the incorporation of multiple speakers rather than only one or two. Previously, there was only a main speaker commenting on the whole match or two speakers, one of them interviewing people related to the match at the beginning, during the break, or the end of the match (see

Salameh, 2024b). As a result of this change, speakers now tend to interact with each other during some parts of the program, which may lead to more colloquial interventions despite the formality expected in this specialized discourse genre.

Thus, interactivity triggers the use of spoken DMs not employed in earlier decades: colloquialization can be supported by the presence of this type of DMs and the reduction or even absence of written-like DMs. The use of one or another type of DMs is not the only feature of an ongoing colloquialization or a completed colloquialization process; rather, they are combined with other linguistic features revealing such a language change process (e.g., hesitations, interruptions, simultaneous talk, or their presence in relevant moments of match narrations). The analysis proposed in this paper focuses on examples like (1) distributed across decades so as to detect this transformation in the type of DMs employed by speakers in broadcasts. Before presenting results, some specifications about data and methods are required.

4. Results

Previous studies have explored the relationship between lexical categories and the existence of varying degrees of colloquialization (

Rühlemann & Hilpert, 2017), focusing on elements such as verbs, adjectives, nouns, or DMs. These studies rely on the idea that formal, specialized discourses are expected to display greater lexical complexity, whereas less specialized, informal discourses are typically associated with more immediate and familiar vocabulary (

Stefanowitsch & Gries, 2008). Specifically, in relation to DMs and the variables selected for our analysis, the following can be said:

- (a)

Formal or informal DMs are assumed to correspond to more and less specialized discourses, respectively. Formal DMs are part of a more complex lexicon, unlike informal DMs.

- (b)

Textual functions of DMs are expected to appear in more specialized discourses, where modality and interactivity are reduced. In contrast, modal and interactive functions are more likely to occur in less specialized, more informal discourses.

- (c)

Monologic DMs are expected to be used in more specialized discourses, while dialogic DMs are likely to emerge progressively with increasing colloquialization. This feature, in turn, will probably reflect an external change in football broadcasts, as the number of announcers has grown throughout the decades, especially since 1990.

In the context of broadcast media, some sports broadcasts seem to be more colloquialized compared to others (e.g., football in television and radio vs. horse riding, tennis, or cricket;

Popov, 2019). This suggests that although such texts retain features of specialized discourse, their primary aim is to entertain the audience. In football match broadcasts, this results in narrations that do not only describe actions of the game, but also include opinions about players, interactions between announcers, background information, etc. This creates a communicative space in which DMs contribute to greater immediacy, thereby transforming oral broadcasts into discourses that share several features with spoken conversation.

The analysis is presented below by distributing the results across different decades, following previous research that identifies key time spans in the colloquialization processes of the 20th century (

Salameh, 2024a): an initial stage (1960–1980); a transitional stage, considered a turning point (1980); a third, expansion stage (1990); and a final stage in which the colloquialization process appears to be fully established (2000-onwards). Consequently, only 32 matches from the database have been included in the analysis, and recordings from the 1930s to 1960s have been excluded.

4.1. First Stage (1960–1980)

The first stage covers the earliest matches aired on television. As previously noted, football broadcasts were already well established on radio programs such as

Carrusel Deportivo. However, it is currently not possible to retrieve complete recordings of football radio programs or additional early television broadcasts, which limits the total number of recordings available for the analysis.

Table 3 summarizes some main information about the matches analyzed and their precedence in our audiovisual database for these two decades:

There are 10 complete matches ranging from 1966 to 1978, which allow for a general overview of how football broadcasts were produced during this period. All these matches were aired by RTVE, the national public television channel. The communicative style of this time was notably distant: announcers used a highly formal vocabulary and concentrated on describing each play in the match, along with the emotions derived from the events taking place in the game field. The fact that there was only one announcer covering the match also contributed to this broadcast style.

Regarding the use of DMs, the number seems to be low in the transcriptions analyzed. In addition, this stage is clearly oriented to the use of formal, monological, textual DMs. Observe the following examples:

| (2) | El partido ha empezado hace tres minutos [pausa] aproximadamente en la primera jugada el Barcelona creó una situación de peligro delante del marco que defiende Iríbar [pausa] Seminario estuvo a punto de marcar puesto que Seminario es el extremo izquierda y como consecuencia de esa jugada se lesionó/se produjo daño en una pierna (…) |

| | The match started three minutes ago [pause] approximately in the first play, Barcelona created a dangerous situation in front of the goal defended by Iríbar [pause] Seminario was close to scoring, since Seminario is the left winger, and as a result of that play, he was injured/suffered a leg injury (…) |

| | (Athletic—Barcelona F.C., 1966, min. 0:13) |

| (3) | (…) dentro de unos minutos, mejor dicho, en estos precisos instantes están saliendo ya al terreno de juego los jugadores del Atlético de Madrid/ahí los tienen ustedes (…) |

| | (…) in a few minutes—rather, at this very moment—the Atlético de Madrid players are already coming out onto the pitch/there they are for you to see (…) |

| | (Atlético de Madrid—Deportivo de la Coruña, 1968, 0:05) |

| (4) | (…) y cuyo salto será siempre muy difícil de igualar por el hombre que le marca/por Gaztelu/quien, sin embargo, ha luchado de una manera admirable, constante, cerca del que ha sido el más efectivo mejor hombre (…) |

| | (…) and whose leap will always be very difficult to match by the man marking him—by Gaztelu—who, nevertheless, has fought in an admirable and consistent manner, staying close to the man who has been the most effective, the best player (…) |

| | (Athletic de Bilbao—Real Sociedad, 1969, min. 35:19) |

| (5) | (…) y la jugada ha terminado en corner (pausa) ha vuelto al terreno el balón con el que se estaba jugando antes pero ahora ha sido de nuevo retirado (pausa) el Sr. Sullenmurg quiso, no obstante, comprobar en qué estado estaba la pelota (…) |

| | (…) and the play ended in a corner [pause]; the ball that was being used before has returned to the pitch, but it has now been removed again [pause] Mr. Sullenmurg wanted, nevertheless, to check the condition of the ball (…) |

| | (Atlético de Madrid—Ajax, 1970, min. 56:13) |

| (6) | (…) sigue mandando, pues, el resultado de 2 a 1 del Ámsterdam (…) |

| | (…) the 2–1 scoreline in favor of Amsterdam still stands, then (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—Ajax, 1972, min. 45:48) |

| (7) | (…) número 10 Popivoda/número 7 Kudic/número 9 Kustudic y Susic el número 11/es decir, juegan los dos hermanos (…) |

| | (…) number 10 Popivoda, number 7 Kudic, number 9 Kustudic, and Susic, number 11—in other words, both brothers are playing (…) |

| | (Yugoslavia—España, 1977, min. 1:01) |

Examples (2)–(7) represent a selection from matches aired between the 1960s and 1980s. The type and category of the DMs used by announcers during these decades are limited: almost all of them are formal, textual DMs. Additionally, these DMs are employed in monologal contexts. These features help in establishing the degree of colloquialization experimented by football match broadcasts during this stage, which seems to be minimal or nonexistent, very close to written sports chronicles in newspapers.

In terms of frequency, it should be noted that the number of markers employed in these early broadcasts is significantly reduced compared to those aired in later decades: less than 30 DMs have been found in our database. Announcers seem not to require additional time to formulate their utterances, allowing for easily linked ideas without the need for several DMs in the construction of discourse. This feature combines with an absence of hesitations and repetitions associated with low discourse planning. Contrarily, precise descriptions of match actions were preferred, involving the choice of very specific verbs or nouns, or even medial positions for DMs unexpected in oral contexts, as observed in examples (4), (5), and (6).

Specifically, the category of the DMs used reveals such a highly planned nature in broadcasts, even in live matches: descriptions are lexically rich, which also results from the slow pace of broadcasts. Thus, most of the textual DMs employed belong to the particular categories of consecutive markers (e.g., “puesto que,” “pues,” “por tanto”), contrastive markers (e.g., “sin embargo,” “no obstante”), and reformulation markers (e.g., “mejor dicho,” “es decir”), which suggests a general broadcasting pattern: announcers highlight consequences of previous actions, unexpected developments, and the need for rephrase statements for greater specificity so as to guide the audience throughout comments during the whole match.

Finally, the DMs employed are related to monologal contexts, as all matches are narrated by a single announcer: television broadcasts in the 1960s and 1970s still did not import broadcasting models from the radio based on a real interactivity shared by announcers (e.g., José María García, José Ramón de la Morena in Cadena SER and Cadena COPE), so simulations of dialogicity in addressing the audience were not required. This is an external feature affecting the linguistic uses found in this discourse genre: television channels keeping their football match broadcasts as highly monologal discourses contributed to the overall communicative distance defining this period.

To conclude, alongside textual DMs, a few modal markers are introduced to reinforce opinions or subjective comments, such as “en efecto” in (8):

| (8) | El árbitro ha señalado falta/parecía que no la iba a pitar, pero, en efecto, la ha señalado/falta a Arieta (…) |

| | The referee has called a foul/it looked like he was not going to blow the whistle, but in fact, he did/foul on Arieta (…) |

| | (Athletic—Barcelona F.C., 1966, min. 56:44) |

Nevertheless, the presence of modal DMs during 1960 and 1970 is minimal in comparison to textual DMs: this is particularly the case because modality seems to be mostly conveyed through adjectival structures or adverbs (

Salameh, 2024b). Their use will be increased later, especially since the 1990s.

4.2. The Trigger for a Change: 1980

This second stage represents a transitional period. Previous research supports that the decade of 1980 involved the beginning of some external and internal changes that would eventually lead to the colloquialization process being fully accomplished later (

Salameh, 2024a,

2024b). Particularly, this includes the incorporation of additional announcers and new technical developments, such as the use of more cameras and microphones (

Roger Monzó, 2015, p. 133). The analysis of this decade is based on six audiovisual recordings

4 aired by RTVE.

Table 4 summarizes the main information about the six matches included in this part of the analysis:

First, the number of DMs used in the matches appears to increase significantly during this period: a simple manual search reveals more than 15 instances per match. This rise in the use of DMs may be linked to the external changes mentioned earlier: the addition of more cameras enabled replays and, consequently, more commentary. Furthermore, the presence of two or more announcers encouraged the creation of a more spontaneous communicative space, allowing for a broader use of DMs, even though football broadcasts still belong to the domain of specialized discourse, and the narration continued to exhibit communicative distance (i.e., little or no dialogicity, no emotional discourse, a predominance of monologic descriptions of the match, and only occasional formal references to the audience).

Regarding functions, the DMs employed during this transitional stage introduced new categories that do not present in earlier decades. As noted, from an overall perspective, the broadcasting style of these matches still maintains the communicative distance expected for this genre: play-by-play descriptions remain lexically rich. However, the inclusion of additional speakers in the broadcast appears to facilitate the use of interactive strategies, including DMs, a change that impacts not only the frequency but also the types of DMs used. As a result, our database reveals new modal and interactive uses of DMs, alongside the textual ones. Dialogicity increases naturally in monologal segments of the match, but it becomes particularly evident in new dialogal contexts, such as interviews of football players. The following examples illustrate these developments:

| (9) | (…) se le escapaba con esa característica suya de parar al capitán de la Real Sociedad el balón/y así fue pero sin embargo sobre su lado izquierdo (…) |

| | (…) the ball was getting away from the Real Sociedad captain, with that characteristic way he has of stopping it/and that is what happened, but nevertheless, on his left side (…) |

| | (Real Sociedad—Athletic Club, 1982, min. 21:48) |

| (10) | (…) el Hércules acaba de lograr el empate/Hércules 2 Valencia 2/se juega el Hércules el descenso/aunque/claro/se depende también de otros resultados (…) |

| | (…) Hércules has just equalized/Hércules 2; Valencia 2/Hércules is fighting to avoid relegation/although/of course/it also depends on other results (…) |

| | (Real Sociedad—Athletic Club, 1982, min. 1:40:41) |

| (11) | (…) Locutor 1: atención al balón/Sarabia/GOL/gol de Sarabia/gol número once de Sarabia/gol número once/qué piensas, Miguel, se nos ha ido el campo |

| | Locutor 2: bueno/pues pienso que se está mereciendo/vamos a ver si podemos conseguir los que hacen falta (…) |

| | Announcer 1: Watch the ball/Sarabia/GOAL/goal by Sarabia/Sarabia’s eleventh goal/eleventh goal/what do you think, Miguel, have we lost control of the match? |

| | Announcer 2: Well/I think it is deserved/let us see if we can get the ones we still need (…) |

| | (España—Malta, 1983, min. 1:22:01) |

| (12) | (…) el juez de línea había indicado saque de puerta/pero Ramos Marco ha indicado córner (pausa) así pues, segundo córner a favor del Real Madrid en este segundo tiempo (…) |

| | (…) the linesman had indicated a goal kick, but Ramos Marco has given a corner [pause] so then, it is the second corner for Real Madrid in this second half (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—Barcelona, 1984, min. 27:49) |

Examples (9)–(12) are drawn from matches aired between 1982 and 1984. As illustrated by the transcriptions, announcers make use of textual DMs (e.g., “sin embargo,” “así pues”), strongly influenced by the DT of written, specialized texts. However, these markers are combined with modal and interactive DMs (e.g., ‘claro’, ‘bueno’), as well as textual markers employed in formulative processes (e.g., “pues pienso que”…). Notably, the use of the DM “no obstante,” which is closely associated with written and formal registers, is significantly reduced. These discourse patterns tend to emerge in dialogic contexts where two announcers interact with each other. Interestingly, however, modal DMs expressing opinion and subjectivity are also introduced in monologic interventions, as seen in example (10). Additional instances show this same functional behavior in the remaining transcribed matches, as can be observed in examples (13)–(17):

| (13) | (…) Juanito envía para Butragueño/ha cortado Könerbag/recupera Solana para el Real Madrid/Martín Vázquez/está buscando apoyos/pero la verdad es que no lo había encontrado (…) |

| | (…) Juanito passes to Butragueño/Könerbag intercepts/Solana recovers it for Real Madrid/Martín Vázquez/he’s looking for support/but the truth is he had not found any (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—FC Köln, 1986, min. 42:51) |

| (14) | (…) bueno/yo creo que es la culminación de la temporada porque pienso que al conquistar este trofeo vamos a ser el mejor equipo de Europa y merecidamente puesto que hemos sido campeones de liga campeones de la UEFA y hemos llegado a semifinal (…) |

| | (…) Well/I think this is the culmination of the season because I believe that by winning this trophy, we’ll be the best team in Europe—and deservedly so, since we’ve won the league, the UEFA Cup, and reached the semifinals (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—FC Köln, 1986, min. 1:31:41, contexto de entrevista) |

| (15) | Locutor 1: (…) 0 a 0 en el marcador/en estos primeros minutos eh/qué nos puede apuntar Miguel Muñoz de lo que estamos viendo en el terreno de juego |

| | Locutor 2: bueno/pues en el aspecto táctico parece ser que (carraspea) el Oporto (…) |

| | Announcer 1: (…) 0–0 on the scoreboard/in these opening minutes, eh/what can you tell us, Miguel Muñoz, about what we’re seeing on the pitch? |

| | Announcer 2: well/tactically, it seems that (clears throat) Porto (…) |

| | (Oporto—Real Madrid, 1987, min. 5:31) |

| (16) | Locutor 1: Martín Vázquez cambia para Míchel/ante él está Semedo/Míchel el que ha disparado/fuera (pausa) parece que es la banda izquierda el camino más por el que el Madrid llega más fácil |

| | Locutor 2: (habla a la vez) sí/por eso te digo/que desde el principio deben deben cerrarle el camino se están abriendo camino por ahí/debe tratar de explotar eso/hasta que se den cuenta y intenten cerrarnos/si es que pueden/claro (…) |

| | Commentator 1: Martín Vázquez switches the ball to Míchel/Semedo is in front of him/Míchel takes the shot/wide [pause] it seems the left flank is the easiest route for Madrid to break through |

| | Commentator 2: (speaking simultaneously) yes/that’s why I’m saying/from the start they have had to shut that down, they are breaking through there/they should try to exploit it/until the other team realizes and tries to close it off—if they can, of course (…) |

| | (Oporto—Real Madrid, 1987, min. 30:37) |

| (17) | (…) una toma más de la repetición de esa acción/no obstante ya está Paolo Maldini/el joven y gran lateral izquierdo recuperado/tan solo tiene veinte años y ya en esta Eurocopa fue considerado como uno de los mejores (…) |

| | another replay shot of that action/nevertheless, here is Paolo Maldini/the young and outstanding left-back, now recovered/he is only twenty years old and was already considered one of the best in this Euro Cup (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—AC Milan, 1988, min. 46:44) |

The use of textual DMs is still productive during this decade, which means that announcers needed to organize their discourses through markers highlighting the way actions occurred during matches. Probably, the fact that announcers were able to describe plays recorded by various cameras involved a faster narration or, at least, a more dynamic one compared to earlier decades: as a result, they required further DMs in producing their discourses as their planning was a bit more reduced. Again, cause-consequence and opposition were the more frequent specific textual functions (e.g., “sin embargo,” “por tanto”), as well as some cases of reformulation textual markers (e.g., “es decir”), but these formal-like, written markers started to be combined with other formulative, more informal-like markers, linked to orality and a lower discourse planning, especially in the last years of the decade, as observed in examples like the following (18):

| (18) | (…) y podía hacer mucho más-más daño/se ha adelantado también Martín Vázquez por la parte izquierda/y ahora está jugando (pausa) más definido/con tres puntas digamos/eh (…) |

| | (…) and he could have caused much more—more damage/Martín Vázquez has also pushed forward down the left side/and now they are playing [pause] in a more defined way/with three forwards, let us say/eh (…) |

| | (Oporto—Real Madrid 1987, min. 41:15) |

Interactive DMs also became frequent in the decade of 1980, with a special preference for forms such as “bueno,” “claro,” or “la verdad (es que)” in an initial position of responses, as shown in examples (11) and (13)–(15). These interactive DMs are highly linked to prototypical spoken conversation (

Pons Bordería et al., 2023), which suggests that some specific parts of broadcasts were opened to incorporate particular features of this genre. Finally, modal DMs were also allowed in these broadcasts, but the expansion in their use would happen later, since the 1990s.

4.3. Colloquialization Growing: 1990

The changes observed in the use of DMs during the two previous stages appear to intensify from the 1990s onward. Once again, several external factors contributed to this shift toward more direct, closer communication between announcers and even with the audience: (a) the introduction of three commentators, who not only narrated the match but also conducted interviews with club presidents, coaches, and players before and after the games; (b) the distribution of communicative roles among announcers, which promoted dialogicity and genuine interactive cooperation (for example, a main commentator covering most of the match’s key actions, former players providing expert analysis, especially on technical plays, and on-field or grandstand interviewers; and (c) the technical developments completed during the 1990s, including major investments by private and some regional channels in equipment such as additional cameras, high-quality microphones, and small cameras behind the goals. These advances enhanced production quality for instant replays as well as for quicker and more dynamic commentary. These developments would fully explode throughout the 2000s and beyond.

The analysis for this decade is based on six audiovisual recordings aired by CANAL+, a pay-per-view channel. Private broadcasters transformed the nature of television football commentary, partly by incorporating features from earlier radio broadcasts. As a result, the matches examined in this stage display notable differences when compared to those aired on the national public television RTVE

5, even during the same period.

Table 5 summarizes key information about the matches analyzed:

The overall number of DMs used in football broadcasts during this decade has increased notably compared to the previous two stages. A manual search in the transcriptions reveals approximately 20–25 instances per match, a figure that can be attributed to the more natural dialogicity observed in these broadcasts, derived from the well-established presence of multiple announcers.

This increase in the use of DMs reflects a shift in the DT behind football broadcasts: from discourse specifically focused on describing the core actions of the match for the audience (e.g., plays, referee decisions, the score, and occasionally updates from other matches or external background information, particularly at the beginning or during the halftime break), to discourse that encompasses both narration and a broader range of on-field and off-field information (e.g., pre-match context, team standings in league competitions, specific player data, detailed recreations of key actions, etc.). In other words, from the 1990s onwards, the central focus of football broadcasts seems to shift toward entertainment and fast, comprehensive information, a development that may be associated with broader processes such as colloquialization and spectacularization (

Fairclough, 1992) (see also

Section 5).

More specifically, these increasingly conversational settings also facilitate the use of DMs related to modality and interactivity, rather than being restricted only to textuality, as illustrated by the following examples:

| (19) | Pues el partido que ya tiene un gol/vamos a ver si en los minutos que le queda mantienen la intensidad/y la samba de Míchel (…) |

| | Well, the match already has a goal/let us see if in the remaining minutes they keep up the intensity/and Míchel’s samba (…) |

| | (Atlético de Madrid—Real Madrid, 1991, min. 1:12:43) |

| (20) | Locutor 1: forman un tándem bastante unido/y coinciden mucho sus vidas futbolísticas/yo no sé si Ángel Capa y Jorge Valdano hoy tienen algún sistema para ponerse en contacto/Pedro González |

| | Locutor 2: pues/la verdad es que antes de comenzar el encuentro durante todo el calentamiento que hizo el Real Madrid (…) |

| | Announcer 1: They make a pretty close duo/their football careers have a lot in common/I do not know if Ángel Capa and Jorge Valdano have any system to stay in touch today/Pedro González |

| | Announcer 2: Well/the truth is that before the match began, throughout the whole warm-up that Real Madrid did (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—Deportivo de la Coruña, 1995, min. 4:17) |

Most parts of the commentary include elements of subjectivity introduced by the announcers, such as opinions about the match, the players, and other related aspects, which in turn triggers the use of modal DMs typically found in dialogic contexts (e.g., “pues,” “la verdad es que,” etc.). Announcers also interact with one another, which facilitates the use of interactive DMs and other similar strategies (e.g., “pues” introducing responses, “bueno” indicating disagreement, etc.). With regard to textual DMs, both their frequency and functional variety are considerably reduced during this period in comparison to the increasing presence of modal and interactive markers used by the announcers. Nevertheless, textual markers continue to appear in the 1990s, as observed in examples (21)–(24):

| (21) | (…) y esta es la quinta cartulina de Stoickov y, por tanto, se perderá el próximo partido del FC Barcelona contra el Zaragoza (…) |

| | (…) and this is Stoichkov’s fifth booking, and therefore he will miss FC Barcelona’s next match against Zaragoza (…) |

| | (Athletic Club—Barcelona, 1993, min. 39:25) |

| (22) | (…) recuperó, sin embargo, Goikoetxea, que retrasó el balón para Kouman (…) |

| | (…) Goikoetxea recovered the ball, however, and played it back to Koeman (…) |

| | (Athletic Club—Barcelona, 1993, min. 47:05) |

| (23) | (…) el Deportivo de la Coruña más reservón/bien quizá es cómo juega 3-3-3-1/o sea, que está jugando como toda la pretemporada (…) |

| | (…) Deportivo de La Coruña looking more defensive/well, maybe it is because they’re playing 3-3-3-1/in other words, the same way they have been playing all preseason (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—Deportivo de la Coruña, 1995, min. 59:46) |

| (24) | (…) no había logrado nada positivo en este estado el Santiago Bernabéu/hoy, sin embargo, ante el Real Madrid si en la vuelta de la Supercopa logra empatar (…) |

| | (…) they had not achieved anything positive at this venue, the Santiago Bernabéu/today, however, against Real Madrid, if they manage a draw in the second leg of the Supercopa (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—Deportivo de la Coruña, 1995, min. 1:26:40) |

In these examples, specific functions such as cause-consequence, opposition, and reformulation continued to be expressed through textual DMs (e.g., “sin embargo,” “o sea” or “es decir,” “por tanto,” “entonces”). These functions were already used by announcers in the two previous stages, but their presence during the 1990s is considerably reduced. This shift is also associated with a semasiological trend: consequences and conclusions are mainly introduced with “por tanto”; oppositions with “pero” and “sin embargo” (the latter to a lesser extent); and reformulation with “o sea,” the most polyfunctional reformulation marker in Peninsular Spanish.

Additionally, it must be pointed out that the use of textual markers such as “no obstante,” which were highly frequent in the 1960s and 1970s, was drastically reduced during this period, probably because such markers are too strongly linked to written language to be employed in oral broadcasts. This reflects a clear transformation toward greater orality and informality, moving away from the high degree of discourse planning characteristic of written contexts. This trend coincides with the appearance of formulative textual DMs associated with spontaneous speech and lower levels of discourse planning (e.g., “digamos,” “pues,” “eh,” etc.).

The reduction and specialization in the use of textual DMs in football match broadcasts contrasts with the increase in modal and interactive DMs. As noted earlier, modality and interactivity seem to be driven by changes in the overall structure of broadcasts. Specifically, the emergence of a new communicative scenario derived from the introduction of multiple speakers, technical innovations, and live interviews encourages the use of interactional strategies typical of real, spoken conversation, marked by closer communicative proximity between participants. This feature, in turn, is well received by the audience. See examples (25)–(28):

| (25) | (la retransmisión comienza con una imagen de salida de vestuarios, con los jugadores dándose ánimos para el enfrentamiento). |

| | Locutor 1 (responde a lo anterior): pues claro que sí/que tienen que ver este espectáculo que, esperemos, vaya a ser este partido entre el Athletic Club de Bilbao y el Barcelona (…) |

| | (The broadcast begins with footage of the players leaving the locker room, encouraging each other before the match). |

| | Announcer 1 (responding to the previous scene): Of course/they have to witness this spectacle, which, we hope, this match between Athletic Club de Bilbao and Barcelona is going to be (…) |

| | (Athletic Club—Barcelona, 1993, min. 0:12) |

| (26) | (…) hay que destacar siempre el trabajo del portugués/hoy, sin embargo, no hemos podido disfrutar con Rivaldo/aunque, claro, aquellos de ustedes que sean hinchas del Real Madrid pensarán algo totalmente diferente (…) |

| | (…) the work of the Portuguese player should always be highlighted/today, however, we have not been able to enjoy Rivaldo’s performance/although, of course, those of you who are Real Madrid fans will probably think quite differently (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—Barcelona, 1999, min. 1:40:47) |

| (27) | Locutor 1: (…) y con Emilio Butragueño, Juan Carlos Nieto |

| | Locutor 2: sí/bueno/Emilio/habéis devuelto al Atlético de Madrid el resultado de la primera vuelta y/Butragueño es Pichichi con diecinueve goles |

| | Butragueño: hombre/la verdad es que he tenido bastante suerte en los dos goles porquee el primero era una jugada de (…) |

| | Announcer 1: (…) and with Emilio Butragueño, Juan Carlos Nieto |

| | Announcer 2: Yes/well/Emilio/you have returned the favor to Atlético de Madrid with the same result as in the first leg, and/Butragueño is now the Pichichi with nineteen goals. |

| | Butragueño: Well/to be honest, I was pretty lucky with both goals because the first one was a play that… |

| | (Atlético de Madrid—Real Madrid, 1991, min. 1:31: 54, contexto de entrevista) |

| (28) | (…) Vicente del Bosque tiene a un jugador menos/yyy el que se marcha es Roberto Carlos quee/tras las idas y venidas de un continente/de un país a otro/Tailandia/Madrid/Europa/Asia/pues- se tiene más que merecido el descanso (…) |

| | (…) Vicente del Bosque is one player short/aaand the one coming off is Roberto Carlos, who—after all the back and forth between continents, from one country to another—Thailand, Madrid, Europe, Asia—well, he more than deserves the rest (…) |

| | (Real Madrid—Barcelona, 1999, min. 1:36:51) |

As illustrated by examples (24)–(27), the original monologic style of broadcasting was gradually abandoned in favor of dialogal and dialogical dynamics. Individual interventions by announcers begin to simulate dialogicity directed at the audience, as if viewers at home were part of the interaction. This shift once again facilitates the use of DMs typical of spoken, colloquial contexts (e.g., “pues claro”), often marked by a high degree of modality.

Dialogicity is also explicitly reproduced in broadcasts when announcers interact with one another to conduct interviews with players (as in example 26), prompting the use of DMs that introduce responses (e.g., “bueno,” “pues”). The use of interactive DMs by football players themselves is also significant, as they are not consciously controlling the degree of formality in their speech (e.g., “hombre” as used by Butragueño so in response to the announcer’s question)

6.

This period thus marks the beginning of a transformation from monologal > dialogal > dialogicity in football broadcasts, in relation to the use of DMs, a shift that would become fully consolidated from the 2000s onward.

4.4. Colloquialization Completed: 2000–Onwards

This final period marks the consolidation of the colloquialization process in football match broadcasts. The 2000s reflect a fully accomplished transformation in the DT of oral broadcasting, particularly evident in the use of DMs

7: all the tendencies identified in the previous decade become standardized, with written-like markers being replaced by oral, speech-like ones. A total of ten recordings have been analyzed, all retrieved from both CANAL+ and La Liga TV, private, pay-per-view channels. The following table (

Table 6) summarizes key information regarding their source and year of broadcast:

The frequency of DMs increases significantly during the 2000s. A manual analysis confirms an average of 30–40 markers per match, with a clear predominance of modal and interactive DMs and a noticeable reduction in textual markers, particularly those associated with the high degree of discourse planning typical of written registers. Overall, the DMs found in this period are informal and closely aligned with spoken, colloquial uses.

The fact that announcers now incorporate a large number of DMs as a natural resource in their broadcasts indicates the consolidation of the transformation in the DT described above. Early broadcasts featured an average of only 10–15 DMs per match, suggesting that announcers initially relied on other strategies for structuring discourse and, more importantly, that there was little need to express modality or interactivity through discourse markers. As a specialized discourse, football match broadcasts keep formal lexical choices in their narration (e.g., specific, concrete verbs, nouns, or adjectives), but they tend to be combined with opinions and subjective comments conveyed through less distant noun or adjective structures. This balance between information and entertainment is reinforced by the use of DMs typically found in spoken conversation, closely tied to the global trend of colloquialization in football broadcasting. The following examples illustrate this development:

| (29) | Locutor 1: (…) en la primera división del que qué podemos apuntar, Joaquín Ramo Marco/buenas tardes |

| | Locutor 2: hola, Carlos, buenas tardes/bueno/decir ya lo has dicho tú todo/es el árbitro más joven de esta categoría (…) |

| | Announcer 1: (…) in the first division, what can we say about it, Joaquín Ramo Marco/good afternoon |

| | Announcer 2: Hello, Carlos, good afternoon/well/you have already said it all/he is the youngest referee in this category (…) |

| | (Valencia—Real Madrid, 2000, min. 2:08) |

| (30) | Locutor 1: (…) es dentro |

| | Locutor 2: es dentro/y la verdad es que toca en el pie de Caerw/¿eh? |

| | Announcer 1: It is inside |

| | Announcer 2: It is inside/and the truth is it hits Caerw’s foot, right? |

| | (Valencia—Real Madrid, 2000, min. 1:37:50) |

| (31) | Locutor 1: (…) el balón rechazado que sale hacia Makelelé/primera falta/agarrón de Albelda |

| | Locutor 2: ya/agarrón de Albelda/sí |

| | Locutor 3: bueno/muy notable el agarrón/¿no? |

| | Locutor 1: amonestó verbalmente Undiano Mallenco y la jugada también ha quedado tendido/ahí está/por ese golpe de Fabio Aurelio/ahí está el agarrón/casi estrangulamiento de Albelda/Joaquín |

| | Locutor 2: sí/pero claro/decíamos/¿eso tiene que ser amonestado? Pues sí/pero fíjate a qué nivel (…) |

| | Announcer 1: (…) The cleared ball that goes to Makelelé/first foul/Albelda’s grab |

| | Announcer 2: Yes/Albelda’s grab/yeah |

| | Announcer 3: Well/quite a noticeable grab, right? |

| | Announcer 1: Undiano Mallenco gave him a verbal warning, and the player is still down/there he is/from that hit by Fabio Aurelio/there’s the grab/almost a strangulation by Albelda/Joaquín |

| | Announcer 2: Yeah/but of course/we were saying/should that be a yellow card? Well, yes/but look at the level of it… |

| | (Valencia—Real Madrid, 2000, min. 4:28) |

Examples (29)–(31) confirm this trend: there is an announcer commenting on the main parts of the match, but all the announcers interact constantly, prompting the use of both modal and interactive strategies. The use of interactive DMs in these contexts facilitates a dynamic flow of turn-taking and helps avoid overlapping interruptions (e.g., “ya,” “¿no?,” “¿eh?”). Modal DMs are used to reinforce or mitigate opinions about the match or the players (e.g., “claro,” “fíjate,” “bueno,” “la verdad es que”). Finally, textual DMs appear to be clearly influenced by the conversational style incorporated into broadcasts (e.g., “pero,” “pues,” etc.). The use of written-like, textual markers, common in earlier stages, has either diminished significantly or disappeared entirely in the 200s. Nevertheless, some announcers may still use them sporadically (e.g., “por tanto,” “sin embargo”), as shown by the next example:

| (32) | (…) ataca el Real Madrid/ha despejado la defensa blaugrana/ya ven que ha marcado el Mallorca/Víctor Luque/empata, por tanto, en Riazor/Deportivo de la Coruña 1—Mallorca 1 (…) |

| | (…) Real Madrid attacks/the Barcelona defense clears it/as you can see, Mallorca has scored/Víctor Luque/so it is a draw, then, at Riazor/Deportivo de La Coruña 1—Mallorca 1 (…) |

| | (Barcelona—Real Madrid, 2001, 1:14:56) |

However, cases like (32) are relatively infrequent in the 2000s. A specific quantification of the matches analyzed reveals that forms such as “por tanto,” “sin embargo,” and “no obstante,” typically used to express cause-consequence and opposition, have almost disappeared, with fewer than two instances per match. This semasiological observation reflects an onomasiological shift: announcers have redirected textual marking toward other functions, such as formulation (e.g., “pues” and “eh,” with more than 35 and 20 instances per match, respectively). Reformulation markers like “o sea” and “es decir” are still used, but “o sea” in particular exhibits functional specialization, frequently appearing in modal contexts as well. Additionally, the marker “pero,” which holds both connective and discursive functions, seems to have taken over the role of earlier textual, written-like markers used in the 1960s and 1970s, with over 70 instances per match, either alone or combined with other markers, such as “claro” or “bueno”).

Another functional change is the sharp increase in the frequency of modal and interactive DMs. Forms such as “bueno” (more than 30–40 instances per match), “claro” (around 20), and some modal values of “pues” are predominant in broadcasts, reflecting a reduction in discourse planning and a broader transformation in the structure of football commentary, from a pure informative discourse to one that is both informative and entertaining. This change has been evident since the early 2000s, with a clear consolidation from 2010 onwards. New markers such as “mira” or “fijate” also begin to appear during this period. Additionally, particularly relevant is the positional behavior of modal markers, also placed at final position of interventions and combined with other markers. All these observations can be checked in examples (33)–(36):

| (33) | (…) porque lucha por un balón/que no ha hecho nada más que luchar por un balón reciba una tarjeta a mi modo de ver bastante injusta/pero bueno |

| | (…) because he is fighting for a ball/and for doing nothing but fight for a ball, he gets a card, which in my view is quite unfair/but well |

| | (Barcelona—Real Madrid, 2001, min. 1:25:58) |

| (34) | (…) igual que Iniesta, o Rakitic, no hablemos de Messi/cuando cogen un balón mejoran la jugada/André Gomes/la verdad es queee/no es lo mismo/¿eh?/o sea/yoo/me parece que hay una diferencia abismal (…) |

| | (…) just like Iniesta, or Rakitic, let us not even talk about Messi/when they get the ball, they improve the play/André Gomes/the truth is thaaat/it is not the same/right?/I mean/I think there is a huge difference (…) |

| | (Atlético de Madrid—Barcelona, 2017, min. 39:40) |

| (35) | Locutor 1: (…) el FC Barcelona |

| | Locutor 2: era consciente de eso/perdona/Ernesto Valverde ayer en la rueda de prensa cuando le preguntaban/bueno/pues ehh qué partido esperaba y queee sí que reflejaba es que si el Atlético se adelantaba ellos iban a tener muchas dificultades |

| | Commentator 1: (…) FC Barcelona |

| | Commentator 2: They were aware of that/sorry/Ernesto Valverde yesterday in the press conference when they asked him/well/uhm what kind of match he was expecting, and what he did reflect was that if Atlético got ahead, they were going to face a lot of difficulties |

| | (Atlético de Madrid—Barcelona, 2017, min. 37:02) |

| (36) | (…) el factor sorpresa/y después/claro/Christensen ha tenido que que emplearsee muy rápido/y el- y de ahí el error/bueno/pues tres puntos de oro paraaa el Real Valladolid ahora mismo/el Barça que va a intentar ponerse las pilas (…) |

| | The element of surprise/and then/of course/Christensen had to react very quickly/and that is where the mistake comes from/well/three golden points for Real Valladolid right now/Barça is going to try to pull themselves together (…) |

| | (Real Valladolid—Barcelona, 2023, min. 7:28) |

All the examples analyzed for this final stage demonstrate how dialogal contexts and dialogicity have become fully established in football match broadcasts, without excluding formal, lexical usage in the description of technical plays. The audience is considered a kind of participant in the interaction shared among the announcers and mediated by the main announcer narrating the match. This dynamic facilitates the use of discourse markers typically found in colloquial, spoken conversation.

5. Discussion: Results, Colloquialization, and Conversationalization

The study of colloquialization in football match broadcasting through the analysis of discourse markers used by announcers can be summarized through the following main findings:

- -

First stage (1960s–1970s). Football broadcasts during this initial stage display a clear preference for textual DMs (e.g., “puesto que,” “no obstante,” “sin embargo,” “por tanto,” “en primer lugar,” etc.). Modal and interactive DMs are entirely absent, as the overall structure of broadcasts does not facilitate dialogicity or the inclusion of announcers’ personal evaluations. The number of DMs is notably lower compared to later stages, suggesting that announcers did not rely on DMs for discourse planning, but rather employed other strategies such as lexical structures or adverbs (

Salameh, 2024b). The textual markers used can be classified as formal-like markers, a feature linked to the high degree of discourse planning behind first football broadcasts, reflecting a minimal or nonexistent degree of colloquialization.

- -

Trigger stage (1980s). This transitional period marks the beginning of the shift toward more colloquial football broadcasting. A general restructuring of discourse is observed, accompanied by subtle linguistic changes, particularly in the use of DMs. Their frequency begins to rise, and new modal and interactive markers are introduced (e.g., “bueno,” “claro,” or “pues”), although their presence remains limited. Textual DMs decline in number and begin to shift functionally: forms such as ”no obstante” and “puesto que” are gradually replaced by markers more closely associated with reduced discourse planning and orality (e.g., “pues” or “digamos”). However, this transformation was not yet consolidated in the 1980s. A shift from formal to informal discourse is also evident, as formal textual markers give way to informal modal and interactive ones, marking the onset of a change in the discourse tradition.

- -

Consolidation stage (1990s). In the 1990s, the trends identified in the previous decade become firmly established. Textual DMs from earlier broadcasts are now used only occasionally and with lower frequency (e.g., “por tanto,” “sin embargo,” “es decir,” “o sea”), while formal, written-like markers effectively disappear (e.g., “no obstante,” “ya que,” “puesto que”). This reduction is largely due to the inclusion of three announcers per match, which encourages real-time interaction and the expression of personal commentary. As a result, modal DMs for reinforcement and mitigation become increasingly common (e.g., “bueno,” “claro,” ”o sea”), along with interactive DMs used to introduce responses (e.g., “pues,” “bueno”). The overall frequency of DMs increases noticeably across transcriptions.

- -

Colloquialization stage (200s onward). During this final period, colloquialization in football match broadcasting appears to be fully realized. This is particularly evident in the use of DMs:

- (1)

Their frequency is high, especially for modal and interactive discourse markers (over 30 per match).

- (2)

Their functional specialization shifts toward more conversational, oral-like dynamics, with new markers commonly used in spoken interaction (e.g., “pero,” “pues,” “mira,” “¿no?,” “¿eh?,” “ya,” “fíjate”).

- (3)

Textual markers are redefined, increasingly linked to low-planning discourse strategies (e.g., “eh,” “digamos,” etc.) and frequently co-occurring with features of spontaneous speech (i.e., hesitations, vowel lengthening

8, interruptions, etc.).

These findings reveal a scenario in which football match broadcasts, despite remaining a specialized journalistic discourse with formal lexical elements for describing actions, now reflect structural elements of spoken conversations.

These results, in turn, present a combined semasiological and onomasiological transformation with implications consistent with previous research on colloquialization in football broadcasts. There is a general shift, in which early broadcasts, modeled on the structure of highly planned texts such as sports chronicles, evolve to partially replicate the structure of spoken conversation, with the aim of entertaining the audience. The shift is supported not only by comparative lexical analyses of chronicles and broadcasts, but also by the specific study of the DMs used in both genres.

In Koch & Oesterreicher’s terms, early oral broadcasts were characterized by a high degree of communicative distance, linguistically expressed through the use of discourse markers, among other features. The main function was to inform the audience through visual content, unlike radio broadcasts, such as Carrusel Deportivo programs, which were more interactive from the outset. The rise of private television channels brought new strategies to engage the audience and persuade them to subscribe to pay-per-view services. Alongside the external transformations initiated in the 1980s, these new channels promoted a more informal and communicative broadcasting style, which encouraged a lexical shift toward colloquiality, including the use of DMs.

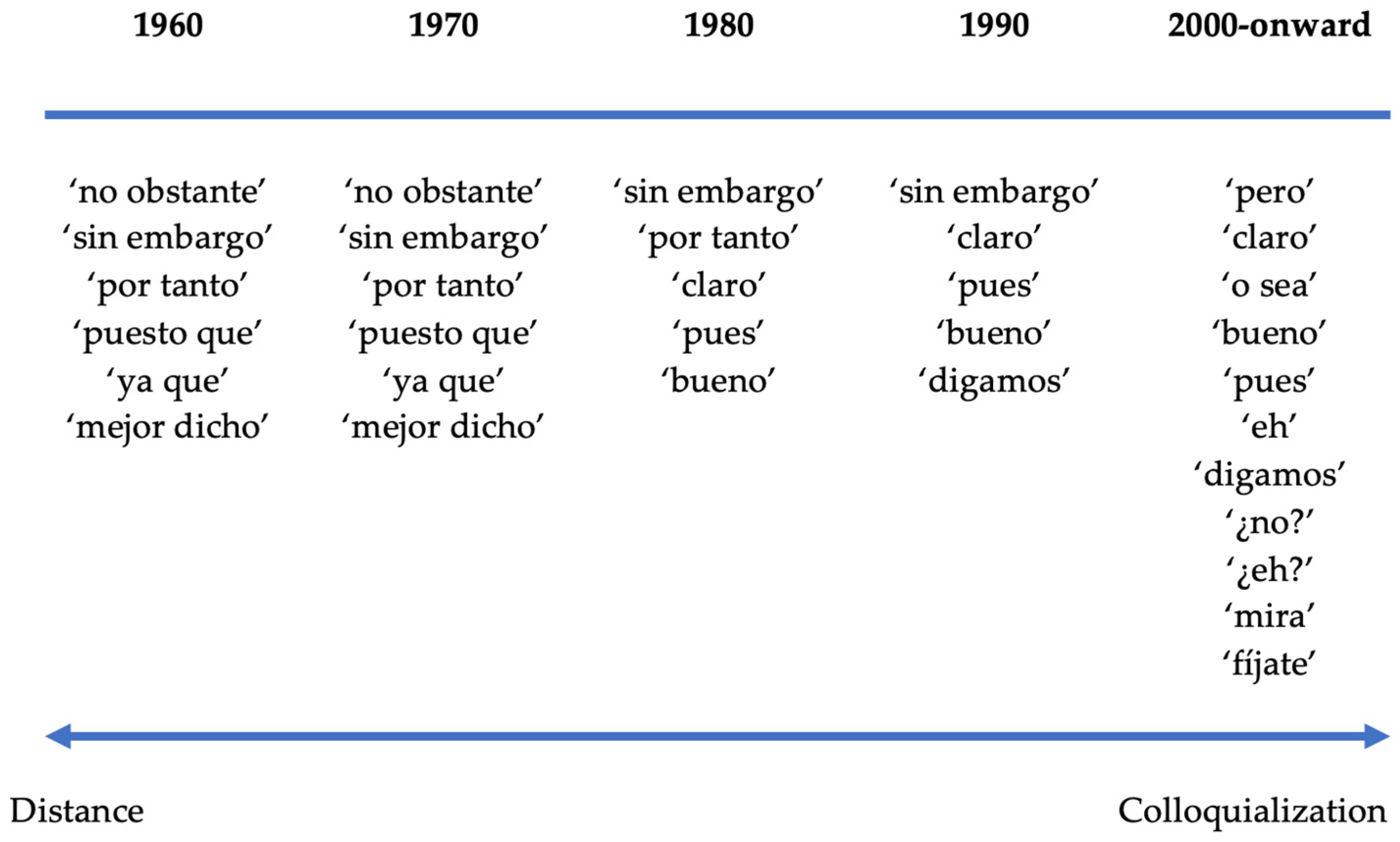

The semasiological analysis of DMs in football match broadcasts thus allows us to outline a broader trajectory of progressive colloquialization across four decades (

Figure 1).

As observed, the earlier decades of football broadcasting are characterized by communicative distance, while broadcasts from approximately the 1990s onward display dynamics much closer to colloquial interaction. Furthermore, the discourse markers used by announcers appear to align closely with those typically associated with formal and colloquial register in Peninsular Spanish. DMs such as “o sea,” “bueno,” “pues,” “eh,” or “mira” are commonly found in spoken interaction, whereas “sin embargo,” “no obstante,” and “puesto que” are typical of written, formal discourses. This contrast becomes especially evident in broadcasts from the 1990s onward.

From a theoretical perspective, the findings of this study contribute to ongoing discussions about the nature of colloquialization in broadcasts. The phenomenon of colloquialization has been approached from two main perspectives: a narrow view, largely adopted in Anglo-Saxon linguistic studies (

Farrelly & Seoane, 2012;

Smith, 2020), and a broader view, proposed within the framework of Romance linguistics (

Koch & Oesterreicher, 1990/2007;

López Serena, 2014;

Briz, 2010;

Salameh, 2024a). The narrow view defines colloquialization as “the adoption of spoken language in written discourses” (