The Online Effects of Processing Instruction on the Acquisition of the English Passive Structure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Input Processing Theory

2.2. Processing Instruction

- “It is predicated on what learners do (and don’t do) during input processing (i.e., sentence-level processing strategies);

- It is input-oriented (learners don’t produce targeted structures during the treatment);

- Input is manipulated in particular ways to alter processing strategies and increase better intake for acquisition (structured input);

- It includes explicit information for the learner on both grammatical structure and processing problems (although the research has shown this is not necessary for its success);

- It follows certain guidelines for the creation of structured input activities.”

- “Present one thing at a time.

- Keep meaning in focus.

- Move from sentences to connected discourse.

- Use both oral and written input.

- Have the learners do something with the input.

- Keep the learners’ processing strategies in mind.”

- (a)

- The donkey is hurt.

- (b)

- The horse is hurt.

- (a)

- Emily

- (b)

- John

| True | False |

| True | False |

2.3. The Processing and Instruction Perspectives of PI

2.4. Offline Studies on the Passive Structure

2.5. Online Studies on PI/SI

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Target Structure

| .شد | دنبال | پیتر | توسط | سارا |

| Was (became) | chased | Peter | by | Sara. |

| Sara by Peter chased was (became). | ||||

| “Sara was chased by Peter.” | ||||

3.3. Instructional Treatment

3.4. Tests and Scoring Procedures

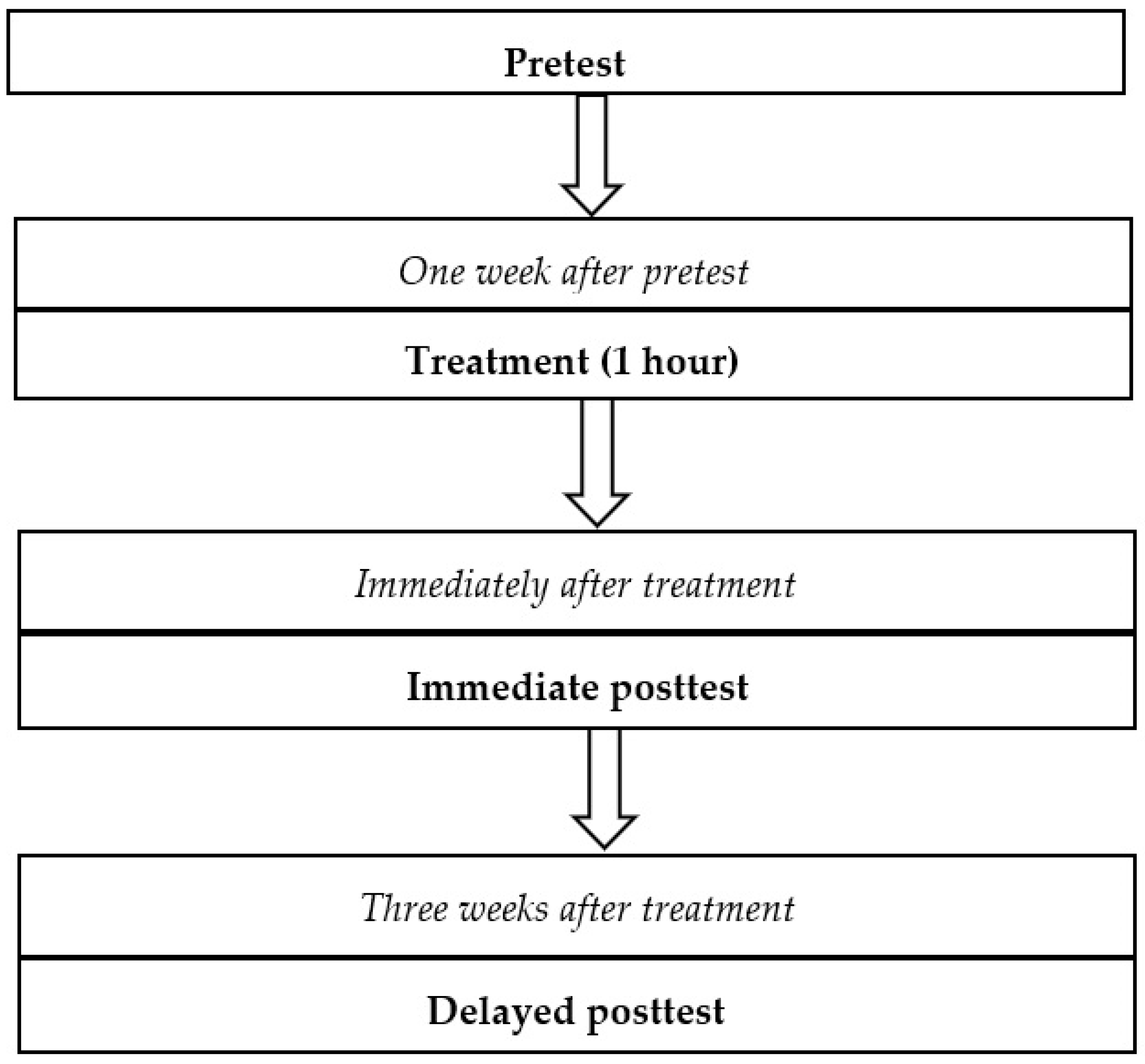

3.5. Procedure

3.6. Data Analysis

4. Results

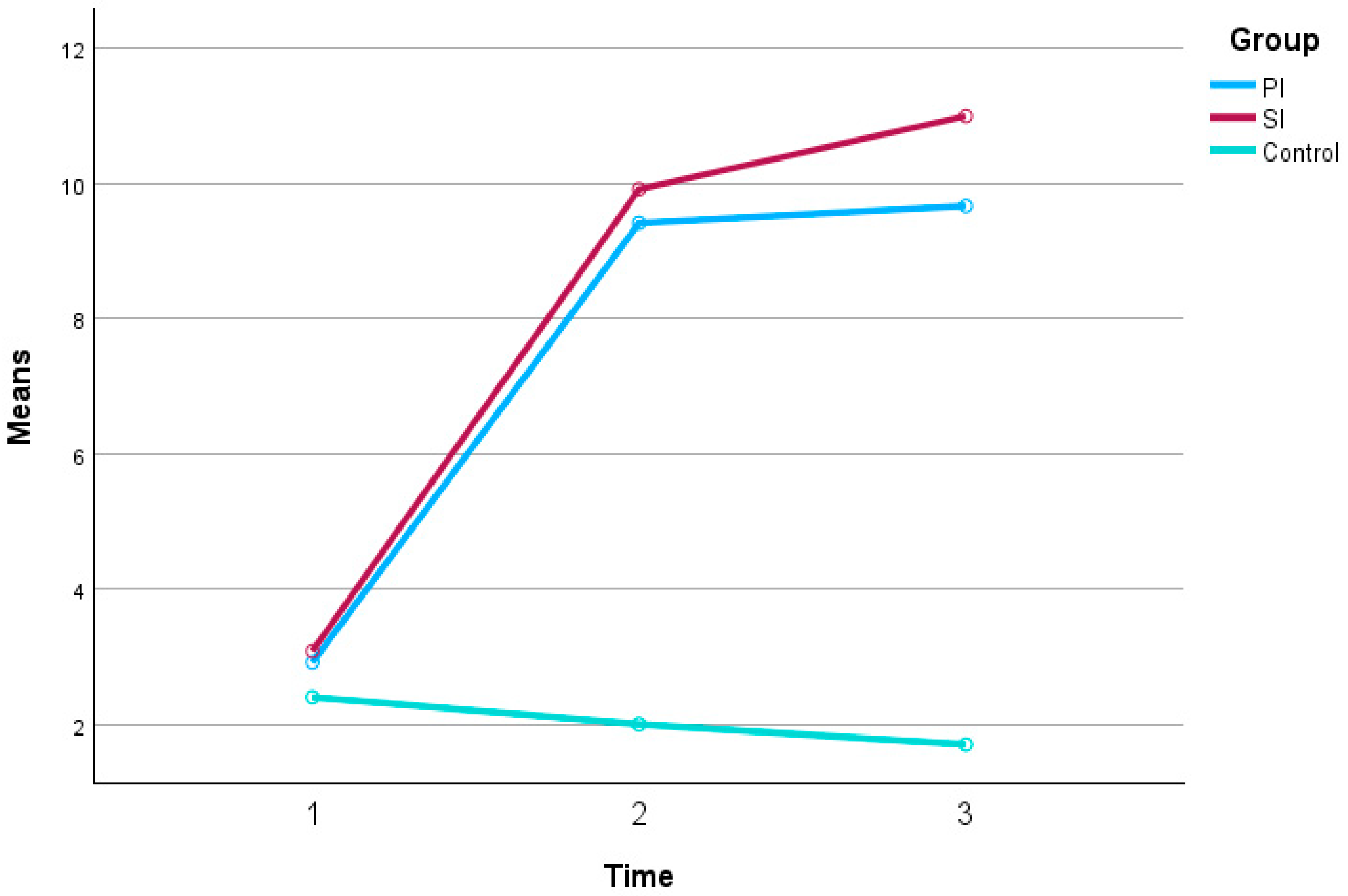

4.1. Accuracy

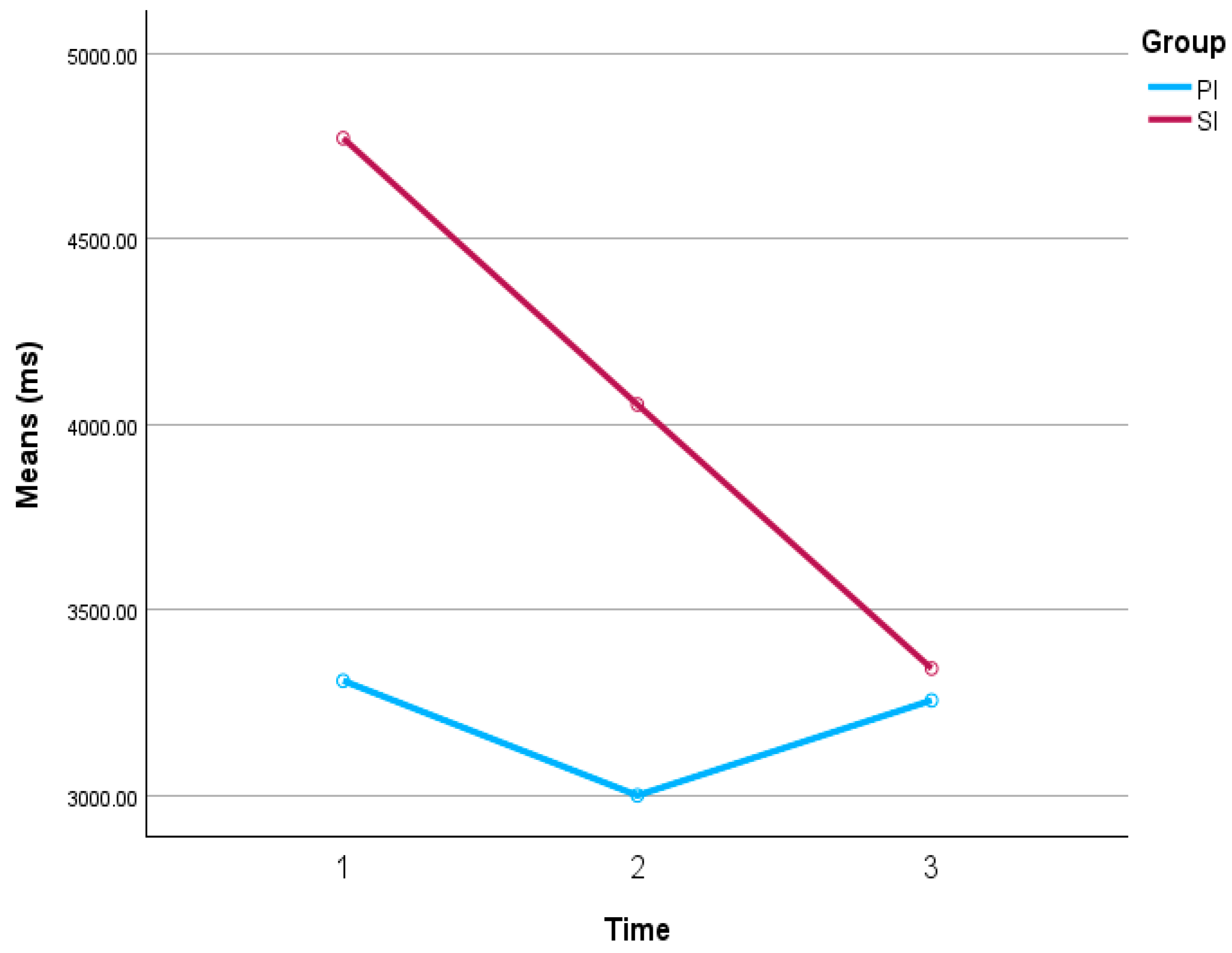

4.2. Response Time in Picture Selection

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Directions for Further Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | An anonymous reviewer asked for the rationale for not offering a corresponding amount of exposure to the target structure (but without instruction) to the control group. The concern was that, in the absence of an equal amount of exposure to the target structure for the control group, we cannot make sure that any potential differences between the treatment groups and the control group would be due to the instructional treatment and not simply exposure to the target structure. It should be noted that providing any instruction to the control group, even in the form of only exposure to the target structure, would actually count as a type of instructional treatment (input flood), which, therefore, would cause the group not to be controlled anymore. Therefore, following similar studies (e.g., Benati, 2023; Benati & Batziou, 2019; Benati & Chan, 2023; Cadierno, 1995; Cheng, 2004; VanPatten & Wong, 2004), the control group did not receive any instruction and only took the tests (pretest, immediate posttest, and delayed posttest). More importantly, previous research has indicated that only exposure to the target structure does not result in any significant achievements in sentence interpretation (e.g., Chiuchiù & Benati, 2020; Issa & Morgan-Short, 2019). Therefore, the observed effects for the treatment groups are not likely to be due to mere exposure to the target structure. |

References

- Allan, D. (2004). Oxford placement test. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benati, A. (2001). A comparative study of the effects of processing instruction and output-based instruction on the acquisition of the Italian future tense. Language Teaching Research, 5, 95–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2004a). The effects of processing instruction and its components on the acquisition of gender agreement in Italian. Language Awareness, 13, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2004b). The effects of structured input and explicit information on the acquisition of Italian future tense. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 207–255). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Benati, A. (2005). The effects of processing instruction, traditional instruction and meaning-output instruction on the acquisition of the English past simple tense. Language Teaching Research, 9, 67–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2015). The effects of re-exposure to instruction and the use of discourse-level interpretation tasks on processing instruction and the Japanese passive. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 53, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2016). Processing instruction and the acquisition of Japanese morphology and syntax. In A. Benati, & S. Yamashita (Eds.), Theory, research, and pedagogy in learning and teaching Japanese Grammar (pp. 73–98). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2020). An eye-tracking study on the effects of structured input and traditional instruction on the acquisition of English passive forms. Instructed Second Language Acquisition, 4, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2021). Structured input vs. meaning output-based instruction on the acquisition of Italian passive constructions. In A. Benati (Ed.), Input processing and processing instruction: The acquisition of Italian and modern standard Arabic (pp. 89–108). John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2022a). Structured input and structured output on the acquisition of English passive constructions: A self-paced reading study measuring accuracy, response and reading time. System, 110, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2022b). The effects of structured input and traditional instruction on the acquisition of the English passive causative forms: An eye-tracking study measuring accuracy in responses and processing patterns. Language Teaching Research, 26, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A. (2023). The effects of structured input and working memory on the acquisition of English causative forms. Ampersand, 10, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A., & Batziou, M. (2019). Discourse and long-term effects of isolated and combined structured input and structured output on the acquisition of the English causative form. Language Awareness, 28, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A., & Chan, M. (2023). Motivational factors and structured input effects on the acquisition of English causative passive forms. Ampersand, 10, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benati, A., & Lee, J. (2010). Exploring the effects of processing instruction on discourse-level interpretation tasks with English past tense. In A. Benati, & J. Lee (Eds.), Processing instruction and discourse (pp. 178–197). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Benati, A., & Lee, J. (2015). Introduction to the special issue. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 53, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadierno, T. (1995). Formal instruction from a processing perspective: An investigation into the Spanish past tense. The Modern Language Journal, 79, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A. C. (2004). Processing instruction and Spanish ser and estar: Forms with semantic-aspectual value. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 119–141). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Chiuchiù, G., & Benati, A. (2020). The effects of structured input and textual enhancement on the acquisition of Italian subjunctive: A self-paced reading study. Instructed Second Language Acquisition, 4, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. (2005). Measuring explicit and implicit knowledge of a second language: A psychometric study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, A. (2004a). Processing instruction and the Spanish subjunctive: Is explicit information needed? In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 227–239). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, A. (2004b). The relative effects of processing instruction and meaning-based output instruction. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 147–172). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, K. I., & Forster, J. C. (2003). DMDX: A Windows display program with millisecond accuracy. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, M., & Leow, R. (2010). Learning without awareness revisited: Extending Williams (2005). Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N. (2022). The offline and online effects of processing instruction. Applied Psycholinguistics, 43, 945–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, B., & Morgan-Short, K. (2019). Effects of external and internal attentional manipulations on second language grammar development: An eye-tracking study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K., & Wong, W. (2019). Processing instruction and the effects of input modality and voice familiarity on the acquisition of the French causative construction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41, 443–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegerski, J. (2014). Self-paced reading. In J. Jegerski, & B. VanPatten (Eds.), Research methods in second language psycholinguistics (pp. 20–49). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. (2015). The milestones in twenty years of processing instruction research. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 53, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Doherty, S. (2019). Native and nonnative processing of active and passive sentences: The effects of processing instruction on the allocation of visual attention. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41, 853–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Malovrh, P., Doherty, S., & Nichols, A. (2020). A self-paced reading (SPR) study of the effects of processing instruction on the L2 processing of active and passive sentences. Language Teaching Research, 26(6), 1133–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & VanPatten, B. (2003). Making communicative language teaching happen (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Leeser, M. J. (2014). On psycholinguistic methods. In J. Jegerski, & B. VanPatten (Eds.), Research methods in second language psycholinguistics (pp. 231–251). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Leow, R. (1995). Modality and intake in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., & Roshan, S. (2019). The associations between working memory and the effects of four different types of written corrective feedback. Journal of Second Language Writing, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malovrh, P., Lee, J., Doherty, S., & Nichols, A. (2020). A self-paced reading study of language processing and retention comparing guided induction and deductive instruction. Instructed Second Language Acquisition, 4, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, E. (2006). Exploring input processing in the classroom: An experimental comparison of processing instruction and enriched input. Language Learning, 56, 507–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. (2007). SPSS survival manual: A step-by-step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows (3rd ed.). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, G.-P. (2004). Comparison of L2 listening and reading comprehension by university students learning English in Korea. Foreign Language Annals, 37, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Stevens, J. (1996). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Y. (2017). Validity of new measures of implicit knowledge: Distinguishing implicit knowledge from automatized explicit knowledge. Applied Psycholinguistics, 38, 1229–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlin, R. S., & Villa, V. (1994). Attention in cognitive science and second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 16, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uludag, O., & VanPatten, B. (2012). The comparative effects of processing instruction and dictogloss on the acquisition of the English passive by speakers of Turkish. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 50, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B. (1996). Input processing and grammar instruction. Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, B. (2004). Input processing in second language acquisition. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 5–31). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, B. (2007). Input processing in adult second language acquisition. In B. VanPatten, & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition (pp. 115–135). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, B. (2015). Foundations of processing instruction. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 53, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B. (2018). Processing Instruction. In J. I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1–7). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B., & Cadierno, T. (1993). Explicit instruction and input processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B., & Fernández, C. (2004). The long-term effects of processing instruction. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 273–289). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- VanPatten, B., & Oikkenon, S. (1996). Explanation versus structured input in processing instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B., & Wong, W. (2004). Processing instruction and the French causative: A replication. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 97–117). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, W. (2001). Modality and attention to meaning and form in the input. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 23, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W. (2004). The nature of processing instruction. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary (pp. 33–65). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, W. (2010). Exploring the effects of discourse-level structured input activities with French causative. In A. Benati, & J. Lee (Eds.), Processing instruction and discourse (pp. 198–216). Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, W. (2015). Input, input processing, and output: A study with discourse-level input and the French causative. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 53, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W., & Ito, K. (2018). The effects of processing instruction and traditional instruction on L2 online processing of the causative construction in French: An eye-tracking study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Mean | Std. Deviation | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | PI | 2.92 | 1.92 | 12 |

| SI | 3.08 | 2.71 | 12 | |

| Control | 2.40 | 2.41 | 10 | |

| Immediate posttest | PI | 9.42 | 2.84 | 12 |

| SI | 9.92 | 2.50 | 12 | |

| Control | 2 | 2.49 | 10 | |

| Delayed posttest | PI | 9.67 | 3.05 | 12 |

| SI | 11 | 2.55 | 12 | |

| Control | 1.70 | 1.94 | 10 |

| Groups | Std. Error | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | PI vs. Control | 1.015 | 1.000 |

| SI vs. Control | 1.015 | 1.000 | |

| PI vs. SI | 0.968 | 1.000 | |

| Immediate posttest | PI vs. Control | 1.125 | <0.001 * |

| SI vs. Control | 1.125 | <0.001 * | |

| PI vs. SI | 1.072 | 1.000 | |

| Delayed posttest | PI vs. Control | 1.111 | <0.001 * |

| SI vs. Control | 1.111 | <0.001 * | |

| PI vs. SI | 1.059 | 0.653 |

| Group | Mean (ms) | Std. Deviation | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | PI | 3308.87 | 1344.01 | 12 |

| SI | 4771.08 | 2958.97 | 11 | |

| Immediate posttest | PI | 2999.88 | 1168.75 | 12 |

| SI | 4053.43 | 923.14 | 11 | |

| Delayed posttest | PI | 3255.96 | 1932.57 | 12 |

| SI | 3341.85 | 2184.08 | 11 |

| Groups | Std. Error | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | PI vs. SI | 944.105 | 0.136 |

| Immediate posttest | PI vs. SI | 422.020 | 0.027 * |

| Delayed posttest | PI vs. SI | 858.300 | 0.921 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pouresmaeil, A.; Wang, X.; Benati, A. The Online Effects of Processing Instruction on the Acquisition of the English Passive Structure. Languages 2025, 10, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070166

Pouresmaeil A, Wang X, Benati A. The Online Effects of Processing Instruction on the Acquisition of the English Passive Structure. Languages. 2025; 10(7):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070166

Chicago/Turabian StylePouresmaeil, Amin, Xin Wang, and Alessandro Benati. 2025. "The Online Effects of Processing Instruction on the Acquisition of the English Passive Structure" Languages 10, no. 7: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070166

APA StylePouresmaeil, A., Wang, X., & Benati, A. (2025). The Online Effects of Processing Instruction on the Acquisition of the English Passive Structure. Languages, 10(7), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070166