Abstract

This paper investigates the acceptability of focused Objects with [+corrective, +exhaustive] features in Italian and French, considering the role of syntactic rigidity, Exhaustivity Markers (EMs), and argument structure. We conducted two parallel acceptability judgment experiments (one per language), testing focused Objects in three positions: (i) in situ, (ii) fronted (FF), and (iii) clefted (CC). Each sentence was also presented with and without an explicit EM, and the verb type was controlled across three categories: transitive, unergative, and unaccusative verbs. Results reveal key cross-linguistic differences: (i) FF is the least acceptable strategy in both languages, contradicting the assumption that Italian tolerates FF more than French; (ii) Italian speakers prefer in situ Focus with an explicit EM, whereas French speakers rate in situ and CC Focus equally acceptable, favoring implicit exhaustivity; (iii) verb type does not significantly impact Focus acceptability, except in French, where intervention effects may reduce FF acceptability in transitive/unergative contexts; (iv) CC remains a viable alternative to in situ Focus in French, possibly acting as a repair strategy. These findings suggest that, as far as [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus is concerned, Italian does not appear to be less syntactically rigid than French.

1. Introduction

The notion of Focus has been playing a central role in the linguistic research of recent decades, and several definitions have been provided to describe Focus in different frameworks and from different perspectives. One of the most prominent definitions has been presented in Jackendoff (1972), in which it is argued that Focus is the part of information that the speaker assumes the hearer does not share with him/her. On the other hand, the “not-focused” part of the sentence (the so-called presupposition) provides background information.

From a semantic viewpoint, two major frameworks have approached the analysis of Focus, namely, the Alternative Semantic approach and the Structured Meaning approach. The former considers Focus as an element introducing a set of alternative propositions, which are potential answers to the interrogative phrase in the question (Rooth, 1985, 1992), whereas the latter assumes that focusing operations lead to a partition of the sentence into a focused part and a background part (Krifka, 2001, 2007).

As is traditionally assumed, different types of Foci must be recognized based on different formal and discourse properties (cf., among others, Kiss, 1998; Aboh et al., 2007; Frascarelli, 2010; Bianchi & Bocci, 2012; Bianchi et al., 2015). Nonetheless, it is still unclear how many types of Focus exist as independent formal categories.

The present analysis will deal with two particular Focus types, namely, Corrective Focus (henceforth, CF) and Exhaustive Focus (henceforth, EF), which will be illustrated in detail in the following sections.

1.1. Corrective Focus

CF is regarded as an independent Focus category (cf., among others, Bianchi & Bocci, 2012; Bianchi, 2013; Bianchi et al., 2015, 2016). Specifically, CF expresses an incompatible description of one and the same event (cf. van Leusen, 2004). In other words, there exists a salient alternative proposition already introduced in the context, which is incompatible with the proposition expressed in the corrective reply. However, it should be noted that CF splits up a proposition into an incompatible part, namely, the correction (the Focus), and a validating part, “the background with respect to which incompatibility is calculated” (Bianchi & Bocci, 2012, p. 9), as shown in example (1b) below, which includes a [+corrective] post-verbal object Focus (i.e., in situ):1

| (1) | a. | L’ | altra | sera | a | teatro, | Maria | si | era | messa | |||||||

| The | other | evening | at | theatre | Maria | 3sg.cl | aux.3sg.pt | wear.pp | |||||||||

| uno | straccetto | di | H&M. | ||||||||||||||

| a | cheap dress | of | H&M | ||||||||||||||

| ‘Yesterday at the theatre, Maria wore a cheap dress from H&M.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | Si | era | messa | un | Armani, | ||||||||||||

| 3sg.cl | aux.3sg.pt | wear.pp | an | Armani | |||||||||||||

| non | uno | straccetto | di | H&M. | |||||||||||||

| neg | a | cheap dress | of | H&M | (Focus in situ) | ||||||||||||

| ‘(She) wore an Armani (dress), not a cheap dress from H&M’ | |||||||||||||||||

As reported in Bianchi and Bocci (2012), in the context given in (1a), the reply of speaker B (1b) can be considered a partial denial since both speakers agree on the background information (that “she wore something”) but disagree on the Focus (“what she wore”). Crucially, the focused constituent is interpreted as the only valid alternative among a set of contextually available options, with the denied alternative made explicit through negation.

In Italian, the corrective interpretation can be conveyed with the focused constituent remaining in situ (Carella, 2019; Frascarelli & Stortini, 2019, among others), as in (1b), or can be associated with Focus Fronting (henceforth, FF), where the focused constituent is moved to a left-peripheral position, even though this operation is only optional and not obligatory to convey a corrective import (cf., Bianchi & Bocci, 2012; Bianchi, 2013). As a matter of fact, another possible reply to the statement in (1a) above can be the one in (1b′) below, in which the focused constituent is moved to the left periphery of the sentence, thus undergoing FF:

| (1b′) | Un | Armani | si | era | messa, | |||||

| an | Armani | 3sg.cl | aux.3sg.im | wear.pp | ||||||

| non | uno | straccetto | di | H&M. | ||||||

| neg | a | cheap dress | of | H&M | (FF) | |||||

| ‘(She) wore an Armani (dress), not a cheap dress from H&M’ | ||||||||||

However, it should be noticed that several studies argue that Focus movement to the left periphery can be realized even in the absence of correction (cf. Brunetti, 2009; Cruschina, 2012; Bianchi et al., 2015, 2016; Belletti & Rizzi, 2017), suggesting that syntax alone is not a reliable diagnostic of CF.

While Italian allows for both FF and in situ strategies, FF in the left periphery is highly restricted in French and does not typically serve as a strategy for marking CF. Several authors have noted the rarity of FF in French (cf. Lambrecht, 1994; Zubizarreta, 2001), and more recent work by Authier and Haegeman (2019) argues that French does not permit CF-driven fronting (example 2d below), but rather only mirative fronting—used to mark speaker surprise or unexpectedness, not correction per se.

Instead, French predominantly expresses CF using in situ Focus or Cleft Constructions (henceforth, CC), with clefting being the canonical strategy for highlighting corrective contrasts (cf. Lambrecht, 1994; Zubizarreta, 2001; Authier & Haegeman, 2019). This is illustrated in (2a), which shows a focused subject in situ, and in (2b’), which presents a focused object realized through CC. By contrast, FF is infelicitous in the CF context, as indicated by the ungrammaticality of (2b″).2

| (2) | a. | Non, Lilou a | porté | le | gilet | hier. | (in situ) | |||||||||||||||

| neg, Lilou aux.3sg.pt | bring.pp | the | waistcoat | yesterday | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘No, Lilou wore the waistcoat yesterday.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Albert | a | appelé | son | fils. (Context for 2b’ and 2b’’) | |||||||||||||||||

| Albert | aux.3sg.pt | call.pp | 3sg.poss | son | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Albert called his son.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b′. | Non, c’ | est | sa | mère | qu’ | il | a | appelée (pas son fils). (CC) | ||||||||||||||

| neg, it | cop | 3sg.poss | mother | that | he aux.3sg.pt call.pp | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘No, it is his mother that-he has called (not his son)’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b″. | *Non, | sa | mère | il | a | appelé (pas son fils). | (FF) | |||||||||||||||

| neg, | 3sg.poss | mother | he | aux.3sg.pt | call.pp | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘No, his mother he has called (not his son)’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

To sum up, in French, CCs allow the speaker to encode the corrective component in a prominent syntactic structure, often accompanied by marked prosody (Lambrecht, 2001; Greif & Skopeteas, 2021). The in situ alternative is also available, especially in informal contexts, though it typically relies more heavily on prosodic cues and explicit negation for disambiguation (cf., Lambrecht, 2001).

1.2. Focus and Exhaustivity

In Kiss’ (1998) influential work, a main distinction is proposed between ‘Information Focus’ and ‘Identificational Focus’, based on data from English and Hungarian. Information Focus (IF) can be identified as the canonical type of Focus (in Kiss’s terms), from which all other types are distinguished and typically employed to introduce new information into the discourse. Identificational Focus, on the other hand, serves to select one alternative as the exclusively valid referent from a contextually salient set. This notion of exclusive selection corresponds to what more recent literature identifies as Exhaustive Focus (henceforth, EF) (cf., Kiss, 1999; Brunetti, 2004).

As a matter of fact, EF is described as a type of Focus that selects a unique referent from the set of alternatives. Thus, the focused constituent is the only one that leads to a true assertion (cf., Hedberg, 1990, 2000; Kiss, 1999; Lambrecht, 2001).

According to Kiss (1998), in a language like Hungarian, the exhaustive interpretation can be obtained through Move to the left periphery (i.e., FF). As a matter of fact, example (3) below (adapted from Brody & Szendröi, 2011, p. 2) is argued to have an exhaustive reading since it is incompatible with “and also some bread”:

| (3) | Context: “A: What did you bring to the party?” | ||||

| B: | Bort | ès | sajtot | hoztam. | |

| wine.acc | and | cheese.acc | bring.1sg.pst | ||

| ‘I brought wine and cheese’ (#and also some bread)3. | |||||

The sentence in (3) implies that only wine and cheese were brought, excluding additional items. This type of exclusionary reading is taken to be an inherent property of FF in Hungarian, supporting the idea that syntactic configuration can directly encode semantic exhaustivity.

Kiss (1998) argues that the same results can also be obtained using CC. In this line, recent works claim that CCs are characterized by an exhaustive interpretation (cf., among others, Kiss, 1999; Delin & Oberlander, 1995 for English; Brunetti, 2004; Frascarelli & Ramaglia, 2013 for Italian; and Lambrecht, 2001, 2004 for French).

For instance, in a structurally rigid language like English, movement to the left periphery is restricted, and English speakers use CC as an alternative strategy to focus elements. This proposal is assumed in Brunetti (2004) and thereafter extended to Italian CCs. Consider the examples in (4–5) below4, followed by their relevant explanation:

| (4) | a. | It was a hat that Mary picked for herself. | |||||||||||||

| b. | Mary picked herself a hat. | ||||||||||||||

| (5) | a. | È | un | cappello | che | Maria | ha | comprato | |||||||

| be.3sg.prs | a | hat | that | Maria | aux.3sg.prs | buy.pp | |||||||||

| (#e | anche | un | ombrello) | ||||||||||||

| and | also | an | umbrella | ||||||||||||

| ‘It is a hat that Maria bought (#and also an umbrella)’ | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Maria | ha | comprato | un | cappello. | ||||||||||

| Maria | aux.3sg.prs | buy.pp | a | hat | |||||||||||

| ‘Maria bought a hat.’ | |||||||||||||||

According to Kiss (1998) and Brunetti (2004), sentences like (4a–5a) imply that Mary bought only one item (‘a hat’), suggesting a unique referent corresponding to the assertion picked up from a closed set of alternatives. Conversely, Kiss (1998) argues that this interpretation cannot be obtained with an in situ Focus like the one in example (4b). Furthermore, as previously mentioned, this proposal has been extended to Italian in Brunetti (2004). Specifically, the author claims that a sentence like (5a) entails an exhaustive reading, contrary to (5b).

In French, a similar contrast holds. However, while FF is syntactically limited and often restricted to mirative readings (cf., Authier & Haegeman, 2019), French employs CC to mark exhaustivity (Clech-Darbon et al., 1999; Destruel, 2012), as shown in example (6) below:

| (6) | C’ | est | Batman | qui | a | pour | mission | d’attraper | ||

| It | cop | Batman | that | aux.3sg.prs | for | mission | to.catch | |||

| les | cambrioleurs | (# and aussi Robin) | ||||||||

| the | burglars | (# and also Robin) | ||||||||

| ‘It is Batman who has the mission of catching thieves (# and also Robin).’ | ||||||||||

| (Destruel, 2012, p. 95) | ||||||||||

Moreover, according to Kiss (1998), in Romance varieties like Italian, French, Rumanian, and Catalan, it is possible for a focused constituent to get an exhaustive interpretation when it is associated with an exhaustive marker (EM). Even though it should be established whether a syntactic construction like FF or CC conveys exactly the same import in different languages (cf., Kiss, 1998; Brunetti, 2004), these specific particles/operators, such as solo in Italian and seulement in French (‘only’), function as semantic operators that encode exhaustivity overtly, as is shown for Italian in example (7) below:

| (7) | a. | Per la | cena | di | ieri | tutti | hanno | cucinato | ||||||||||||||||||

| for the | dinner | of | yesterday | everybody | aux.3pl.prs | cook.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||

| due | o | tre | cose. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| two | or | three | things | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Yesterday, for the dinner, everyone cooked two or three different things.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Leo | ha | cucinato | solo | la | lasagna. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Leo | aux.3sg.prs | cook.pp | only | the | lasagna | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Leo only cooked lasagna’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b′. | #Leo | ha | cucinato | solo | la | lasagna | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Leo | aux.3sg.prs | cook.pp | only | the | lasagna | |||||||||||||||||||||

| e | anche | un | arrosto. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| and | also | a | roastbeef | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘#Leo only cooked lasagna and also a roastbeef’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Specifically, (7b) can be a plausible reply to (7a) since the EM solo (‘only’) licenses a strong exhaustive inference. On the contrary, in (7b′), this reading clashes with the additive conjunction e anche (‘also’), leading to pragmatic infelicity.

The same pattern holds for French, as shown in (8):

| (8) | Jacques | n’ | aime | que | Marie / | Jacques | aime | |||||

| Jacques | neg | love.3sg.prs | that | Marie | Jacques | love.3sg.prs | ||||||

| seulement | Marie | (# et | aussi | Lulu) | ||||||||

| only | Marie | (# and | also | Lulu) | ||||||||

| ‘Jack loves only Mary (# and also Lulu)’ | (adapted from König, 1991, p. 37) | |||||||||||

Exhaustivity is thus assumed to be an inherent property of certain Focus strategies such as FF or CC (Kiss, 1998) or the result of a semantic functional Operator (Beaver & Clark, 2003)5, which can be phonologically null (i.e., silent) in languages like Hungarian, or it can be overt in other languages, like in the Italian solo or the French seulement (both translatable as ‘only’). These two languages will be investigated in the present analysis.

In this line, Pavlou (2015) argues that exhaustivity cannot be uniformly treated. As a matter of fact, the author has drawn a further distinction between different levels of exhaustivity in Focus. Specifically, exhaustivity has been divided into Implicit, when it is considered in terms of pragmatic properties (frequently associated with syntactic structures such as CC or FF), and Explicit, when it is realized with an EM such as ‘only’.

Crucially, Pavlou (2015) argues that exhaustivity does not appear to be either a necessary or an inherent feature of Focus structures. Thus, Focus and exhaustivity should be treated as two separate conditions, even though exhaustivity is typically observed in Focus constructions.

This conclusion aligns with Ylinärä et al. (2023), who claim that exhaustivity should not be viewed as a mandatory feature of Focus but rather as an additional property. Ylinärä’s study frames exhaustivity in terms of composite features, a view we support, as Pavlou’s findings show that Focus can occur without exhaustivity. This suggests that exhaustivity does not constitute an intrinsic property of Focus but instead functions as an optional operator that may or may not emerge, depending on contextual or structural factors.

1.3. Combination of Features

Although the combination of corrective and exhaustive features has not been systematically explored in the literature, one recent exception is Ylinärä et al. (2023), who explicitly investigate the potential role of [+corrective, +exhaustive] feature bundling as a trigger for FF in Italian and Finnish. Their study, however, focuses on a distinct cross-linguistic comparison and does not address the interaction of these features in Romance varieties beyond Italian. Furthermore, as will be discussed in Section 2, the present study adopts a refined statistical approach and explores the effect of this feature combination in a more controlled and balanced dataset. As such, this work provides novel empirical insight into the syntactic effects potentially induced by feature bundling in [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus.

In his work, Cruschina (2021) proposes a scalar model based on the degree of contrast with contextual alternatives. According to this view, the types of Focus can be ranked along a cline of contrastivity as follows:

| (9) | Information Focus < Exhaustive Focus < Mirative Focus < Corrective Focus |

Cruschina observes that languages tend to allow FF for Focus types that are higher on this contrastivity scale. In particular, Italian and Spanish admit FF with both mirative and CF, whereas French allows it mostly in mirative contexts (in line with Authier and Haegeman, 2019). Crucially, Cruschina (2021, p. 7) claims that “the greater the degree of contrast, the greater the potential is for focus to give rise to syntactic effects and, thus, to undergo FF.”

Based on this insight, we hypothesize that the combination of [+corrective] and [+exhaustive] features may give rise to a form of Focus with increased contrastive potential, which could, in turn, increase the acceptability of syntactic movements, such as FF. However, given that these two features are positioned at different points on the contrastivity scale proposed by Cruschina (2021), their combination may not necessarily lead to a cumulative effect. It is, therefore, also plausible that a mismatch or weakening effect occurs, which could decrease the acceptability of FF.

For this reason, our predictions are exploratory in nature. We aim to assess whether [+corrective, +exhaustive] foci exhibit a tendency to license FF more readily than foci bearing only one of the two features—as expected if the two features reinforce each other in terms of contrastivity. At the same time, we remain open to the possibility that this combination yields intermediate or even reduced acceptability of FF due to possible conflicts in feature interaction.

As for French, where CF alone does not usually trigger FF (cf., Authier & Haegeman, 2019; Cruschina, 2021), we hypothesize that the presence of both features may increase the degree of contrast enough to render FF more acceptable than in cases involving only one feature. This effect, however, may remain weaker than in Italian, where FF is already licensed by CF alone. Thus, we tentatively expect a gradient cross-linguistic effect, with Italian displaying generally higher acceptability ratings for FF than French under the same conditions—provided that the combination of features does not result in attenuation rather than reinforcement.

Furthermore, as noted by Brunetti (2009), the realization of FF may also depend on syntactic factors, including the internal structure of the Focus constituent. Specifically, FF tends to be more common when the focused expression is a quantifier or a quantified phrase and when it co-occurs with Focus particles. Since our [+corrective, +exhaustive] foci also include EMs—which are themselves quantificational—this syntactic configuration may further increase the likelihood of FF.

In light of these observations, we consider it essential to treat [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus as a composite, potentially marked category, which deserves dedicated attention in our experimental predictions.

1.4. Focus Strategies

This section examines the different morphosyntactic strategies available for Focus realization in Italian and French. Both languages allow Focus to be licensed in different ways, including in situ (cf., among many others, Frascarelli, 2000; Frascarelli & Stortini, 2019; Lambrecht, 1994, 2001, 2004), FF (cf., Belletti, 2001, 2005; Bianchi et al., 2015; Cruschina, 2012; but see Zubizarreta, 2001; Authier & Haegeman, 2019 for a contrasting view on French), and CC (Authier & Haegeman, 2019; Brunetti, 2004; Lambrecht, 2001, 2004).

1.4.1. The In Situ Strategy

With respect to Focus, the majority of Romance languages, including Italian and French, are often classified as Focus in situ languages (cf., among others, Cruschina, 2012; Samek-Lodovici, 2005, 2006, 2015), although constructions involving FF or CC are also attested (cf., among others, Belletti, 2001, 2005; Bianchi et al., 2015; Cruschina, 2012; Zubizarreta, 2001; Authier & Haegeman, 2019).

This classification aligns with the theoretical hypothesis that Focus functions as a syntactic operator whose scope is determined at the level of Logical Form (LF). As a result, movement of the focused constituent to the CP area does not occur overtly but is rather interpreted covertly at LF (cf., among others, Frascarelli, 2000).

The in situ strategy is considered the unmarked and default realization of Focus in Romance languages, reflecting not only processing efficiency—in that it avoids syntactic displacement—but also typological prevalence, as most Romance languages, unlike Hungarian (Kiss, 1998) or Finnish (Ylinärä et al., 2023), do not require movement of Focus constituents for interpretation. See sentences in (10) for Italian and (11) for French:

| (10) | Gli | ho | dato | un | libro. |

| cl.3sg.m | aux.3sg.prs | give.pp | a | book | |

| ‘I gave him a book.’ | (Frascarelli, 2000) | ||||

In (10), the focused constituent (un libro) remain in situ and receive their focal interpretation from prosodic prominence and discourse structure.

| (11) | a. | Arnim a | escaladé | la | montagne. |

| Arnim aux.3sg.prs | climbed.pp | the | mountain | ||

| ‘Arnim has climbed the mountain’ | |||||

| a’. | Arnim a | escaladé | la | montagne. | |

| Arnim aux.3sg.prs | climbed.pp | the | mountain. | ||

| ‘Arnim has climbed the mountain’ | (Féry, 2001, p. 162) | ||||

Similar to Italian, the in situ realization is a viable strategy for encoding Focus in French. In (11), the subject is in its initial position (11a) and the direct object in the final position (11b). The focal reading is achieved without any syntactic reordering, presumably relying instead on intonation and the contrastive discourse frame, following Samek-Lodovici’s (2006, 2015) claim that the syntax of Romance languages allows for the satisfaction of Focus-related constraints without movement, provided that the prosodic structure aligns with the information structure of the sentence.

1.4.2. Focus Fronting

Focus can also be realized through syntactic movement to the left periphery, specifically to a dedicated position in the CP domain. This movement to a scope position is referred to as an ex situ strategy, as the focused constituent appears outside of its canonical argument position. A common implementation of this approach is FF, which involves moving a constituent to the left periphery of the sentence to give it formal prominence over other elements. Despite its availability, FF is often described as optional (cf., among others, Frascarelli et al., 2022).

FF is an operation that typically involves the constituents that follow the verb (i.e., the object); thus, it is widely recognized as a relevant object Focus strategy, with detailed descriptions provided in several studies (cf., Alboiu, 2004; Hartmann & Zimmermann, 2007; Bianchi & Bocci, 2012; Frascarelli & Stortini, 2019; Stortini, 2024). As previously mentioned, FF is widely attested in Italian, where it represents an optional but commonly used strategy for marking CF, as shown in example (12) for Italian. By contrast, in French, FF is highly restricted and does not typically serve as a strategy for marking CF, as illustrated in example (13):

| (12) | a. | Gianni ha | invitato | Lucia. | |||||||||

| John | aux.3sg.prs | invite.pp | Lucy | ||||||||||

| ‘John invited Lucy.’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | Marina | ha | invitato. | ||||||||||

| Marina (he) | aux.3sg.prs | invite.pp | |||||||||||

| ‘Marina he invited.’ | (adapted from Bianchi, 2013, p. 193) | ||||||||||||

| (13) | ? Marina | il | a | invité. | |||||||||

| Marina | he | aux.3sg.prs | invite.pp | ||||||||||

| ‘Marina he invited’ | (Larrivée, 2022, p. 184) | ||||||||||||

In summary, unlike Italian, FF is not a productive Focus-marking strategy in French. Although fronting constructions are attested in French, they are typically not associated with a CF interpretation or only marginally so (Larrivée, 2022).

1.4.3. Cleft Constructions

A noteworthy strategy for Focus involves the use of copular constructions combined with relative clauses, commonly referred to as the cleft structure (cf., among others, Delahunty, 1982; Declerck, 1988; Den Dickken et al., 2000; Belletti, 2005; Frascarelli, 2010; Frascarelli & Ramaglia, 2014). To illustrate, consider the examples in (14a) for Italian and (14b) for French:

| (14) | a. | È | Gianni | che | i | ragazzi | hanno | salutato | |||||||||

| cop | Gianni | that | the | boys | aux.3pl.prs | greet.pp | |||||||||||

| “It is Gianni that the boys have greeted” | (Belletti, 2008, p. 191) | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | C’ | est | le | cheval | que | le | fermier | a | brossé. | ||||||||

| it | cop | the | horse | that | the | farmer | aux.3sg.prs | brush.pp | |||||||||

| ‘It’s the horse that the farmer brushed.’ | (Destruel, 2012, p. 101) | ||||||||||||||||

In general terms, a CC can be described as a Focus–Presupposition structure (cf., among others, Krifka, 2007), in which the sentence consists of a copular element, a Focus constituent in an extra situm position, and a subordinate relative clause that conveys the presupposed information. This structure emphasizes the focused element while presenting the rest of the sentence as background information.

According to many scholars (cf., among others, Delahunty, 1982, 1984; Declerck, 1988; Heggie, 1988; Den Dickken et al., 2000), the derivation of CC has been analyzed as a copular sentence involving a Small Clause structure (henceforth, SC) in which one constituent specifies the value of the variable represented by the other constituent (cf., among others, Frascarelli, 2000; Belletti, 2005; Citko, 2011).

Thus, from a syntactic perspective, the relative clause is analyzed as a Topic merged in the lowest left peripheral Topic position6, while the (clefted) Focus constituent is the predicate of an SC, whose subject is the resumptive pronoun it (for English), of the low Topic in the structure (cf., Frascarelli & Ramaglia, 2014). We report in (15) the example proposed by Frascarelli and Ramaglia (2014, p. 65) and provide the corresponding structure in (15′), noting that their analysis specifically refers to English and German cleft constructions:

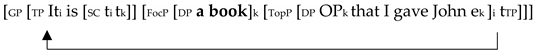

| (15) | It is a book that I gave John. |

| (15′) |  |

Focus is interpreted in the CP domain (Spec,FocP), where it assumes scope over the presupposition. This syntactic configuration allows for agreement between the Focus and the presupposed clause, allowing for correct matching of the [+foc] feature. (cf., Poletto & Pollock, 2004; Frascarelli & Hinterhölzl, 2007).

Despite their role in emphasizing specific elements, CCs are generally considered optional and context-sensitive in many languages. Their use depends on a range of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic factors, making the choice of Focus realization highly context-dependent. This variability reflects the complexity and flexibility of Focus strategies in natural language.

1.5. Research Question and Predictions

In the present paper, we will analyze whether Italian and French adopt different strategies (i.e., in situ, FF, or CC) when realizing a [+corrective, +exhaustive] Object Focus. Since it is traditionally assumed that French has a more rigid structure than Italian (cf., Lambrecht, 1994; Cruschina, 2011; Authier & Haegeman, 2019), the present analysis wants to investigate (i) whether different degrees of “rigid syntax” can lead to the use (and acceptance) of different Focus strategies in the two languages under analysis and (ii) whether the presence/absence of an explicit EM can affect the acceptability of the relevant sentence.

Given that CF alone has been shown to license FF in Italian (Cruschina, 2021), it is plausible that the combination of [+corrective] and [+exhaustive] may increase the acceptability of FF in this language. However, since these features occupy different positions on the contrastivity scale, a reinforcing effect is not guaranteed, and their interaction may also result in attenuation. In French, where CF alone typically does not license FF, we remain open to the possibility that the combination of features may marginally improve acceptability—but this effect may be limited. We thus tentatively expect a gradient cross-linguistic pattern unless feature interaction yields a weakening effect instead.

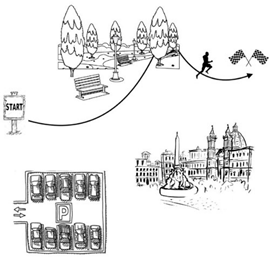

Furthermore, considering that different verbs have different argument structures in the vP shell (Larson, 1988) after External Merge,7 which may influence movement operations to the left periphery,8 we also included three verb types in our test, namely (i) transitives, (ii) unergatives, and (iii) unaccusatives. In this respect, the three different argument structures of the verbs under investigation are the following:

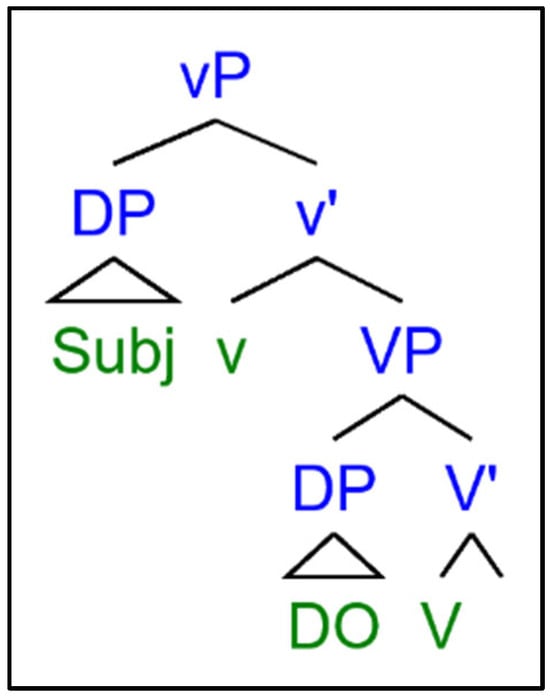

- (i)

- Transitive verbs—the subject–argument is originally merged in Spec,vP, while the object–argument is merged in Spec,VP, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Transitive verbs.

Figure 1. Transitive verbs. - (ii)

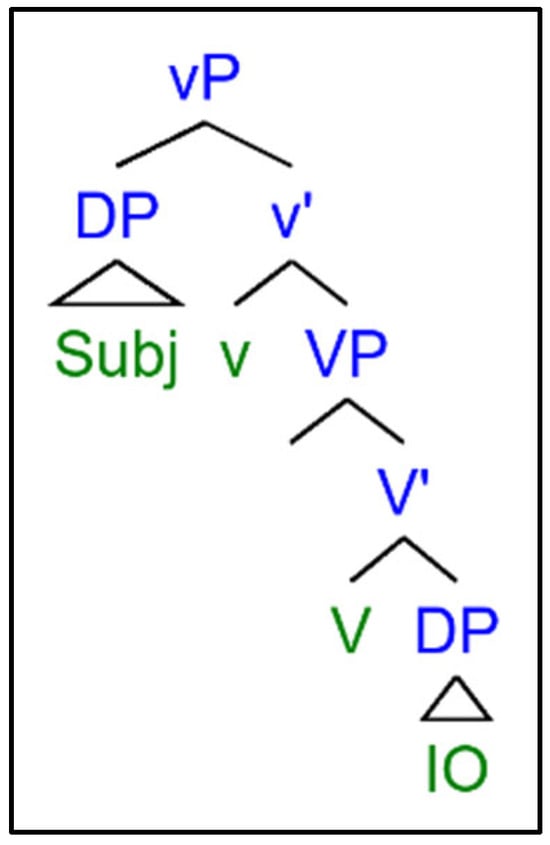

- Unergative verbs—the subject–argument is merged in Spec,vP, and the object–argument (i.e., a Locative Indirect Object) is merged in Compl,VP, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Unergative verbs.

Figure 2. Unergative verbs. - (iii)

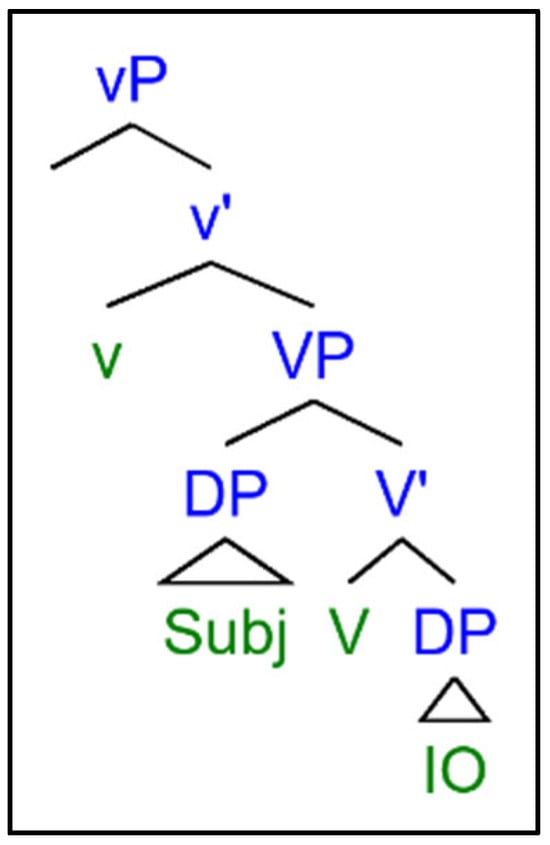

- Unaccusative verbs (motion or state)—the subject–argument is merged in Spec,VP, while the object–argument is merged in Compl,VP (cf., Kratzer, 1994; Chomsky, 1995; von Stechow, 1995, among others), as shown in Figure 3 below.9

Figure 3. Unaccusative verbs.

Figure 3. Unaccusative verbs.

Thus, our research questions are as follows:

- (i)

- Can different degrees of “rigid syntax” influence the acceptance of different Focus strategies in the two languages under analysis, particularly in relation to the complex Focus type [+corrective, +exhaustive]?

- (ii)

- Can the presence or absence of an explicit EM affect the acceptability of the relevant sentences in the two languages under investigation?

- (iii)

- Can different argument structures in the vP affect the movement of the focused constituent?

Based on the discussion above, the following predictions are made:

(i) Given that Italian generally allows FF with CF (Cruschina, 2021), we tentatively expect that the addition of the [+exhaustive] feature may lead to a configuration with increased contrastive potential, which could favor the acceptability of FF. However, since [+corrective] and [+exhaustive] are located at different points on the contrastivity scale proposed by Cruschina (2021), their interaction may not necessarily result in reinforcement. A weakening or mismatching effect is, therefore, also possible.

As for French, although CF alone does not typically license FF (Authier & Haegeman, 2019; Cruschina, 2021), we hypothesize that the co-occurrence of these two features may raise the degree of contrast enough to improve the acceptability of FF—albeit to a lesser extent.

Since our study does not include a direct comparison with simpler configurations, these predictions are exploratory in nature and aim to assess whether feature bundling favors or disfavors syntactic movement in each language.

(ii) With respect to EMs, following Kiss (1998), we tentatively expect that sentences with an explicit EM may be rated as more acceptable in both languages insofar as the EM overtly contributes to encoding the [+exhaustive] feature. Moreover, since EMs are typically associated with quantificational expressions—and FF has been shown to favor quantified phrases (Brunetti, 2009)—their presence may further facilitate the licensing of FF, particularly in Italian. However, given that EMs occur within a broader [+corrective, +exhaustive] configuration in our data, it remains an open question whether their contribution strengthens or interacts differently with other features. Our predictions regarding EMs are, therefore, to be interpreted with caution.

(iii) Concerning verb class, since all three verb types under investigation involve objects that originate in a lower position than the subject, movement to the left periphery is structurally possible in all cases. However, we hypothesize that either (a) transitive and unergative verbs will pattern together—since both involve a subject in Spec,vP—or (b) unergative and unaccusative verbs will align, as both have their internal argument in Compl,VP. No specific interaction is predicted between verb type and the [+corrective, +exhaustive] feature bundle, but this variable is controlled to account for possible structural effects.

In order to check the syntactic properties of [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus in Italian and French, two parallel acceptability tests have been designed in which informants were asked to rate the acceptability of a number of sentences, including Object Foci with [+corrective, +exhaustive] features, with or without an EM, across three different verb contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is based on the results collected through two parallel acceptability tests administered online to 132 Italian and 84 French informants, whose socio-demographic data are provided in the following Table 1:

Table 1.

Socio-demographic data.

It should be noted that the data for Italian informants were drawn from the same experiment conducted by Ylinärä et al. (2023), which compared Italian and Finnish participants. However, our study improves upon their dataset by including a larger sample, as the test remained open for a longer period.

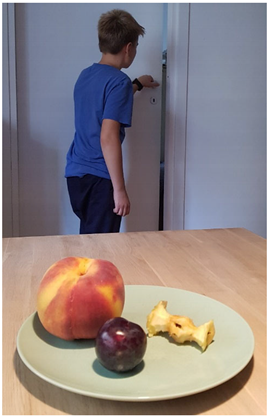

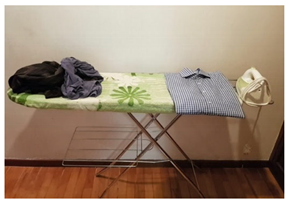

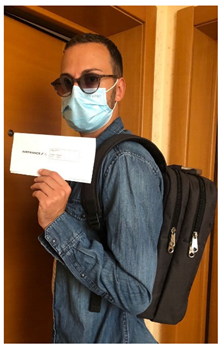

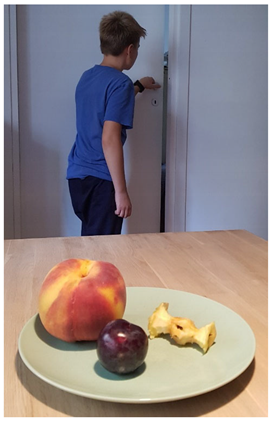

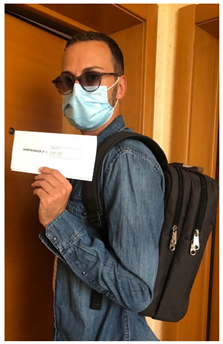

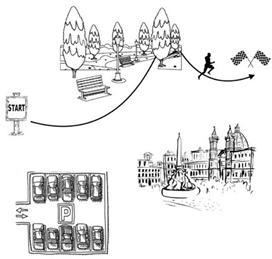

In order to check the syntactic properties of [+corrective, +exhaustive] CF, informants were asked to judge the acceptability of sentences with a focused [-animate] and [-human] Object on a 7-point Likert scale (from 0 = not acceptable to 6 = acceptable). Specifically, the focused Object was tested in three different structures, namely, in situ, fronted or in a CC. Each experimental condition has been set to be the last turn of a short dialogue (between three speakers, i.e., A, B, and C), which was associated with a picture showing the context clearly, with the purpose of accurately conveying the [+corrective, +exhaustive] features. Furthermore, each target sentence was repeated twice, with or without an EM (underlined in the examples below), in order to check whether the presence of an EM could affect informants’ ratings.

Consider the following sentences (16–17) and Figure 4 for reference:

| (16) | Italian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Context: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A: | Che cosa | ha | preso | Marco | dall’ | astuccio? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| what | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | Marco | from-the | pencil case | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘What did Marco take from the pencil case?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B: | La | penna, | la | matita | e | la | gomma. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the | pen | the | pencil | and | the | eraser | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The pen, the pencil and the eraser.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (i) | In situ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Guarda | bene! | Ha | preso | la | penna! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | the | pen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! (He) took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Guarda | bene! | Ha | preso | solo | la | penna! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | only | the | pen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! (He) only took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (ii) | FF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Guarda | bene! | La | penna | ha | preso! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | the | pen | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look better! The pen (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Guarda | bene! | Solo | la | penna | ha | preso! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | only | the | pen | aux.3sg.pt | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look better! Only the pen (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (iii) | CC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Guarda | bene! | È | la | penna | che | ha | preso! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | cop | the | pen | that | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! It is the pen that (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Guarda | bene! | È | solo | la | penna | che | ha | preso! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | cop | only | the | pen | that | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! It is only the pen that (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (17) | French | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Context: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A: | Qu’ | a | pris | Marc | de | la | trousse? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| what | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | Marco | from | the | pencil case | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘What did Marco take from the pencil case?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B: | Le | stylo, | le | crayon | et | la | gomme. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the | pen | the | pencil | and | the | eraser | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The pen, the pencil and the eraser.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (i) | In situ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Il | a | pris | le | stylo! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | the | pen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! He took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Il | n’ | a | pris | que | le | stylo. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | he | neg | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | that | the | pen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! He only took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (ii) | FF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Le | stylo | il | a | pris! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | the | pen | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look better! The pen he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Seulement | le | stylo | il | a | pris! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | only | the | pen | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look at the picture! Only the pen he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (iii) | CC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | C’ | est | le | stylo | que | il | a | pris! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | it | cop | the | pen | that | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! It is the pen that he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | C’ | est | seulement | le | stylo | que | il | a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | it | cop | only | the | pen | that | he | aux.3sg.prs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| pris! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! It is only the pen that he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 4.

Picture for examples (8) and (9)11.

As can be seen from the examples above, one EM was employed in Italian (i.e., solo ‘only’) independently of the structure under analysis, as shown in (16ib, 16iib, and 16iiib). As for French, two strategies were adopted in order to render the relevant sentences as natural as possible, namely, (a) the construction n’a … que in the case of in situ foci (17ib) and the EM seulement (‘only’) in the case of FF or CC (17iib and 17iiib). The choice of n’a … que for in situ Focus follows its natural role as the most commonly used equivalent of ‘only’ in French (Hawkins & Towell, 2015, p. 373). Additionally, O’Neill (2011) highlights that n’a … que functions as an exhaustive identifier within a domain of alternatives, akin to ‘only’ in Hungarian and English. Furthermore, as noted by Dekydtspotter (1993), n’a … que is subject to syntactic constraints that require the que-phrase to remain post-verbal. As a result, this construction naturally aligns with in situ Focus structures, while it is disfavored in fronted configurations such as FF or CC. In these contexts, seulement provides a well-formed alternative. Thus, rather than being fully interchangeable, the two strategies reflect distributional preferences also shaped by syntactic compatibility.

Finally, each sentence included a [+animate] and [+human] Subject. In order to test sentences that would sound as natural as possible to the native speakers who participated in our experiment, the relevant subject was always null (i.e., silent) in the Italian test. On the contrary, the relevant subject was always a full pronoun in the French test (French being a non-pro-drop language).

To sum up, the test included three types of Focus structures, either with or without an EM, and three types of verbs for a total of 18 experimental conditions. In addition, 4 verbs for each type of verb were included in the test to strengthen the results and for statistical purposes12, for a total of 72 experimental items. Furthermore, the test also included one filler for each experimental item, summing up to a total of 144 sentences. Finally, all experimental items were divided into 4 lists using a Latin Square design so that each informant saw and rated one item for each experimental condition. The acceptability test was administered via the LimeSurvey platform and lasted approximately 20–30 min.13 To ensure the privacy of the informants, the test was conducted anonymously, and the settings were configured to avoid collecting IP addresses. Informants viewed one item per page, and once they submitted their judgment and proceeded to the next item, they could not return to previously judged items. All items were randomized to prevent similar constructions from appearing consecutively, and experimental items were alternated with fillers.14

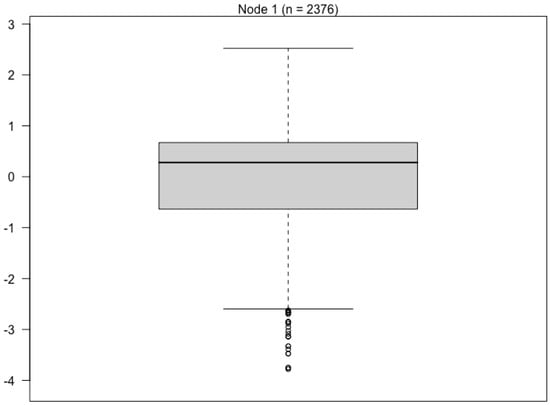

2.1. Statistical Analysis

One of the main problems when adopting acceptability tests is the way informants use Likert scales. While some people might tend to always use the highest part of the scale (i.e., 4–6), others might give lower ratings in general. Data were thus normalized to z-scores15, in order to align different distributions to a normal one and to make the two experiments comparable (Gomez, 2013). In this respect, z-score expresses how far a score is from the mean. Thus, conditions with positive z-scores (i.e., above zero) have to be interpreted as above average, while conditions whose z-scores are below zero have to be considered below average (Gomez, 2013). In other words, when comparing two conditions with statistically significant difference, the one with positive z-score can be considered to be “preferred” with respect to the condition with negative z-score.

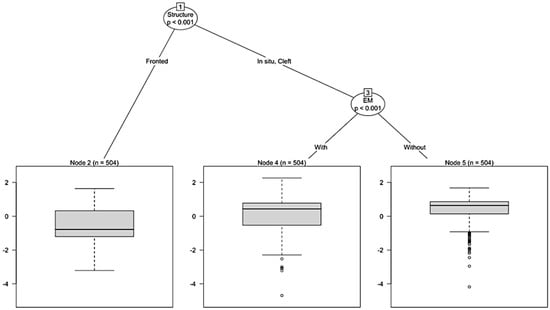

Normalized data were then organized on a long sheet format in which each row corresponds to a single experimental item rated by a single informant. Each occurrence was labeled, including information such as (a) the type of verb (i.e., transitive, unaccusative, or unergative), (b) the type of structure (in situ, FF or CC), (c) the presence/absence of an EM, and (d) language (i.e., Italian or French). Data were eventually analyzed using non-parametric statistical methods in order to identify any possible significant difference. Specifically, we conducted a Mixed-Effects Tree (MET) analysis using the lmertree function from the glmertree library in R Studio (Version 2024.04.2+764), a test suitable for continuous outcomes that allow for the inclusion of both random effects (i.e., Informant) and fixed effects (i.e., Structure, verb type, and EM) (Fokkema et al., 2018). Specifically, our MET analysis accounts for between-subject variability by including the Informant as a random effect. This ensures that the reported effects (Structure, verb type, EM) are robust, as they are estimated while controlling for individual differences. The significance of these effects is, therefore, not dependent on the variance of the random effect but rather on the overall model structure and the data distribution.16

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Data Analysis: Italian

In order to answer our research questions mentioned above, let us first start with the statistical analysis of Italian data.

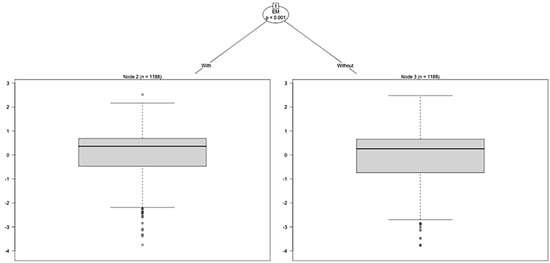

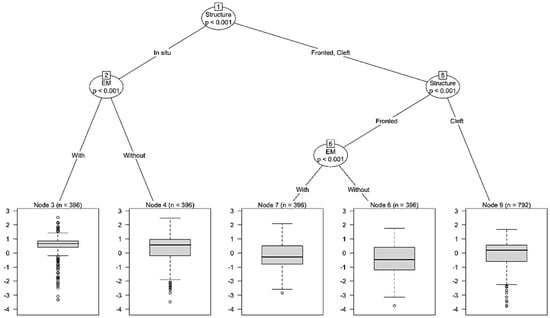

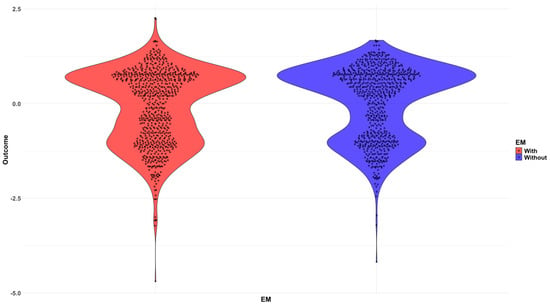

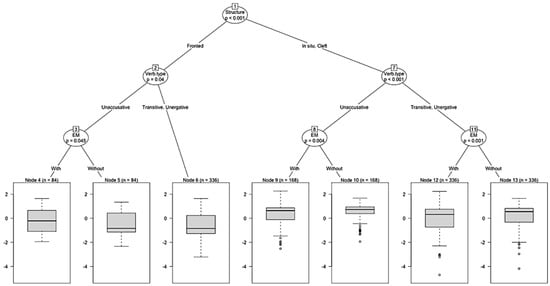

The results of the MET analysis performed on the data collected in our experiment show that the type of verb (i.e., transitive, unergative, and unaccusative) does not significantly affect the (mean of the) score, as no branching occurred (Figure 5). To clarify, METs split into different branches only when statistical differences are detected. This means that an object externally merged in Spec,VP does not show any difference with respect to an Object merged in Compl,VP (with a Subject always merged higher in the vP–shell).

Figure 5.

MET output for verb type—Italian.

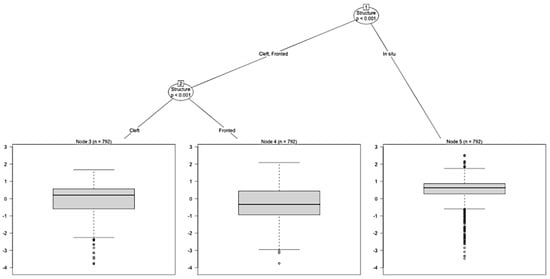

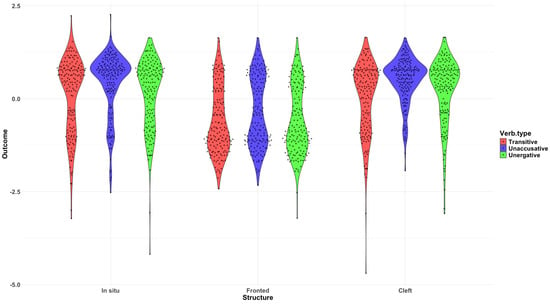

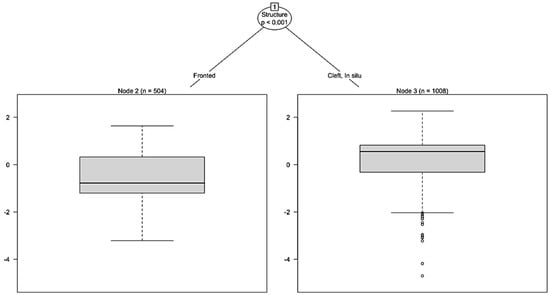

On the contrary, the effect of structure (i.e., in situ, FF, or CF) is significant (p < 0.001; Figure 617), as well as the effect of the EM solo (‘only’) (p ≤ 0.001; Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 6.

MET output for Structure—Italian.

Figure 7.

Distribution for Structure—Italian.

Figure 8.

MET output fot With/out solo—Italian.

A detailed analysis will be given in the following sections.

3.1.1. Structure: Italian

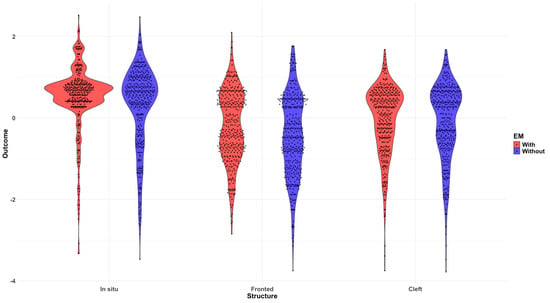

As for the different types of structure under investigation, Italian informants seem to express higher acceptability judgments for in situ rather than fronted or clefted Foci (independently of the verb type and/or the presence/absence of EM), as Figure 6 shows:

Specifically, the MET in Figure 6 shows that the in situ position is significantly more acceptable (M = 0.412) than both FF (M = −0.325) and CC (M = −0.007), as also shown in Figure 7. Furthermore, it should be noted that CC is significantly more acceptable than FF (p < 0.001). While Ylinärä et al. (2023) also found a significant difference between FF and CC, they classified CC as marginal (−0.2), whereas in our model, CC falls within the range of acceptability. This discrepancy may stem from differences in statistical approaches and dataset composition, as our study includes additional informants collected at a later stage and employs a non-parametric method:18

3.1.2. Exhaustivity Marker: Italian

As mentioned above, the presence/absence of the EM solo (‘only’) significantly affects the score. Specifically, sentences with solo are judged significantly more acceptable (M = 0.0904) than those without it (M = 0.0832) (p < 0.001), as is shown in Figure 819:

Further evidence is provided by Figure 920, in which it is shown that acceptability ratings increase for all three structures under investigation (i.e., in situ, FF and CF):

Figure 9.

With/without solo grouped by Structure—Italian.

In order to check whether these differences are significant, we conducted an MET including both Structure and EM as fixed independent variables, thus allowing us to check for possible interactions between the two variables. The presence of the adverb solo (‘only’) increases informants’ acceptability judgments for both in situ (p < 0.001) and FF (p < 0.001). However, FF remains the least preferred option. Finally, CCs are always less acceptable than in situ, and the presence of solo does not significantly increase their acceptability. Importantly, while Ylinärä et al. (2023) also found that solo improves the acceptability of FF, they report that this increase is sufficient to make FF comparable to CCs, with no significant differences between them. In contrast, our results indicate that, even with solo, FF remains significantly less acceptable than CCs (Figure 10). Once again, this discrepancy may stem from methodological differences, as our study includes a larger dataset and employs a non-parametric approach, whereas Ylinärä et al. (2023) used a repeated-measures ANOVA. Thus, our MET analysis suggests that the contrast between FF and CC persists even in the presence of solo (contrary to Ylinärä et al. (2023)):

Figure 10.

MET output for with/without solo and Structure—Italian.

3.1.3. Interim Discussion: Italian

The results of our analysis show that FF and CC are not optimal strategies for marking a focused Object with [+corrective, +exhaustive] features in Italian, as the acceptability ratings for both structures fall below zero, regardless of the presence/absence of an explicit EM. Conversely, the mean z-scores for in situ structures are above zero (see the diamonds in the violin plots for reference), although the presence of an explicit EM significantly increases informants’ acceptability judgments.

The statistical analyses conducted confirm that informants express higher acceptability judgments for sentences with in situ [+corrective, +exhaustive] Foci with an explicit EM, independently of the type of verb under analysis (i.e., transitive, unergative, or unaccusative), as also shown in Figure 10 in Section 3.1.2.

These findings align with recent studies (cf., among others, Carella, 2019; Frascarelli & Stortini, 2019; Ylinärä et al., 2023), which analyzed data from original experiments and showed that in situ structure is the most commonly used strategy for informative, corrective, and mirative Focus. Thus, the higher ratings expressed for in situ [+corrective, +exhaustive] Foci are not entirely unexpected.

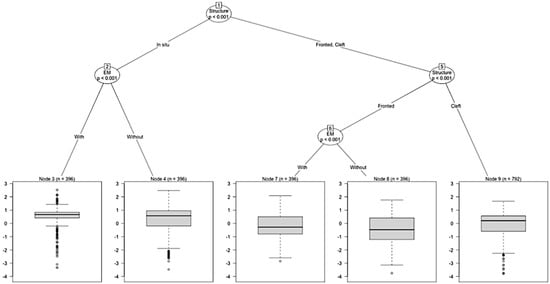

However, when we perform a MET including all variables together in the model (Figure 11), the results observed individually in the previous sections appear to be only partially confirmed. Specifically, the finding that the most acceptable strategy for marking a [+corrective, +exhaustive] focused object is the in situ structure with an EM remains valid. Additionally, the presence of an EM continues to improve acceptability judgments for both in situ and FF structures, while it has no effect on the judgments expressed for CC.

Figure 11.

MET including all variables for Italian.

However, the new MET reveals that in the case of FF with an EM, sentences with unergative verbs are judged less acceptable than those with unaccusative or transitive verbs:

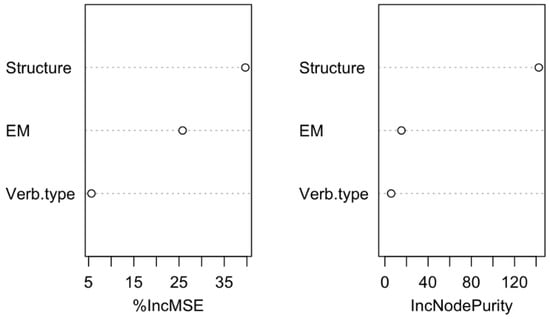

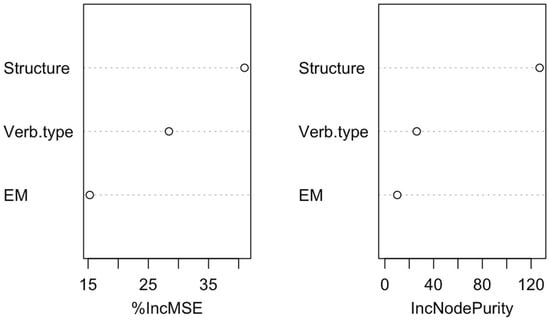

To assess the validity of this model, we conducted a Random Forest analysis, the results of which are shown in Figure 12:

Figure 12.

Random Forest for Italian.

The plot in Figure 12 displays two metrics: (i) %IncMSE (Percentage Increase in Mean Squared Error), shown on the left side, which measures how much the model’s predictive error increases when a variable is permuted. Higher values indicate that the variable is more important for accurate predictions; (ii) IncNodePurity (Increase in Node Purity), which reflects the variable’s contribution to reducing impurity in decision tree nodes. Larger values signify greater importance for splitting the data.

As shown in the plot, the variable Structure is the most influential predictor across both metrics. EM has a moderate contribution to the model, while verb type shows minimal importance for both %IncMSE and IncNodePurity, suggesting that it is less relevant for the model’s predictions.

To evaluate whether the variable verb type improves the model, we performed two models, both including informants’ ID as a random effect. Model 1 (Figure 11) includes Structure, EM, and verb type as fixed effects, while Model 2 (Figure 13) includes only Structure and EM as fixed effects, excluding verb type. We then compared their Mean Squared Error (MSE), with the model having the lower MSE considered better in terms of prediction.

Figure 13.

MET for Model 2 (Italian).

Specifically, Model 1 has an MSE of 0.8466109, while Model 2 has an MSE of 0.8432196. We calculated whether the difference between the two models is significant, and the results show no significant difference.

Given that there is no significant difference between the two models and that Model 2 has a slightly lower MSE, we can conclude that the variable verb type does not add significant value to the model and can be excluded. This suggests that the observed differences for FF with EM concerning verb type can be disregarded, as they do not contribute meaningful predictive importance to the model:

Considering all the above, we can conclude that the general model (Model 2) replicates the results presented in the previous section, with the in situ structure with EM emerging as the most acceptable strategy to mark [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus in Italian.

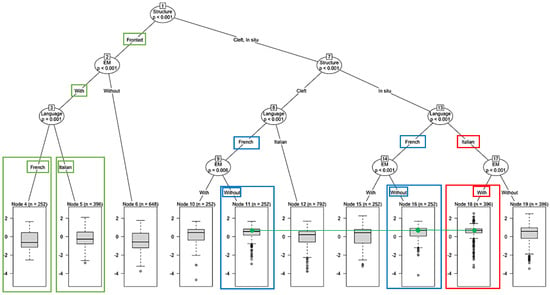

3.2. Data Analysis: French

In order to check for possible similarities and/or differences between the two languages under investigation, the same statistical analyses conducted for Italian were also performed on the data collected from French informants.

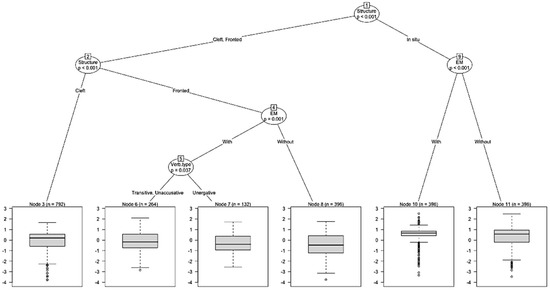

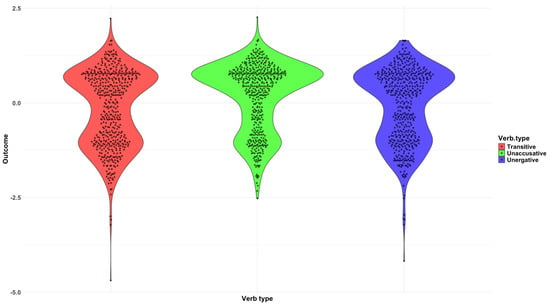

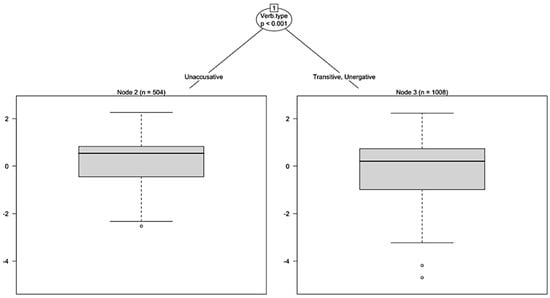

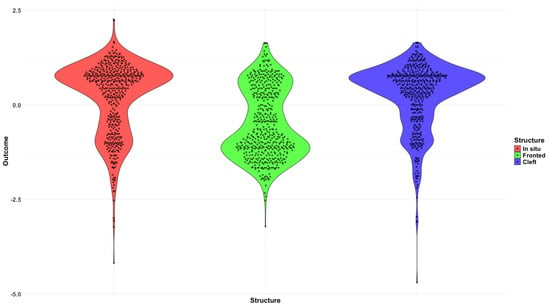

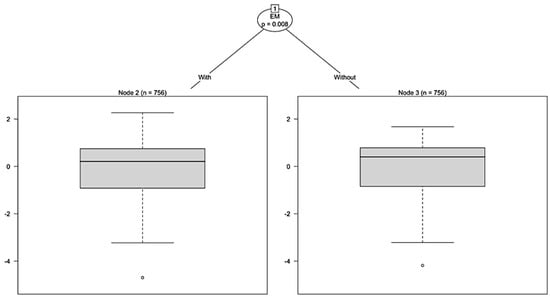

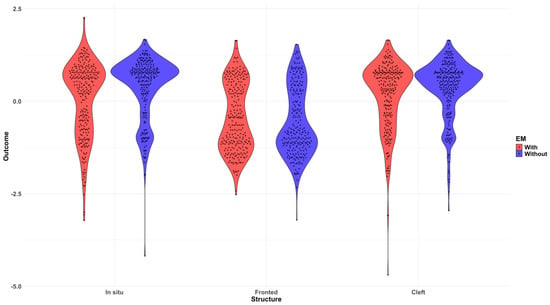

Different from data regarding Italian, the result of the MET performed shows that for French, the score is affected not only by the type of structure under investigation (p < 0.001) and the presence/absence of an EM (p = 0.008) but also by the type of verb (p ≤ 0.001).

3.2.1. Verb Type and Structure: French

Let us first concentrate on the verb type. As Figure 1421 below shows, sentences including transitive and unergative verbs do not seem acceptable since their mean values are below zero. On the contrary, structures with unaccusative verbs are considered acceptable:

Figure 14.

Verb type—French.

These observations are also confirmed by MET performed (Figure 15), which shows significant differences between unaccusative verbs on one side and transitive and unergative verbs on the other (p < 0.001). On the other hand, the difference in the (mean) score for sentences with transitive and unergative verbs is not significant, as the MET does not produce further branching.

Figure 15.

MET output for verb type—French.

Such results appear to be puzzling since they indicate that sentences with a transitive or an unergative verb are generally not acceptable in French. However, by grouping data by Focus structures (i.e., in situ, FF, and CC), a possible explanation can be offered. In this regard, let us now consider the data illustrated in Figure 1622 (followed by its description):

Figure 16.

Verb grouped by Structure—French.

As shown in Figure 16 above, the acceptability judgments expressed for sentences with transitive and unergative verbs are above zero for in situ Foci and CC. On the other hand, FF is always judged as not acceptable, independently of the verb type used. Thus, the negative scores (i.e., below zero) regarding FF seem to affect the general results.

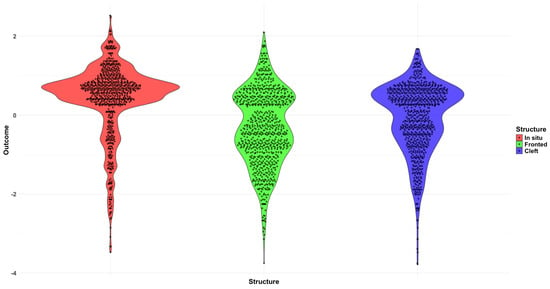

Furthermore, these data are in line with the MET performed in order to investigate the significant differences between structures. Specifically, FF is significantly less acceptable than in situ structures and CC (p ≤ 0.001). On the other hand, no statistical differences are attested, confronting the mean values for in situ (focused) constituents and CC, as the MET does not produce further branching (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

MET output for Structure—French.23

Data in Figure 18 can be explained in light of intervention effects. Specifically, in Frascarelli et al. (2022), it has been shown that fronting of objects externally merged below the subject in the VP–shell is less acceptable than fronting of an object externally merged above the subject (i.e., piacere-like verbs in Italian). However, our data seem to show that this type of intervention effect is gradual and that it also depends on the (external) merging position of the subject. As a matter of fact, the objects are always merged below the subject for all the verbs we selected. However, while the subject is merged in Spec,vP for transitive and unergative verbs, the subject is merged in Spec,VP in the case of unaccusative verbs. Thus, it can be assumed that the movement of an object–argument across a subject–argument internally merged in Spec,VP is perceived as less intervening than the movement of an object–argument across a subject–argument externally merged in Spec,vP, at least in a language like French. However, this question deserves a more in-depth investigation, and it is thus left open to further research.

Figure 18.

Structure—French.

3.2.2. Exhaustivity Marker: French

As for the variable EM (i.e., n’a … que or ‘seulement’), data seems to suggest that marked sentences are less acceptable (p = 0.008), as shown in Figure 19 and Figure 2024 below. That is to say, when no specific EM is at stake, informants express higher acceptability judgments.

Figure 19.

MET output for Exhaustivity marker—French.

Figure 20.

Exhaustivity marker—French.

Nevertheless, the data in Figure 2125 below seem to challenge the proposal put forth above. As is shown, the presence of an EM improves the acceptability of FF, contrary to in situ Foci and CC:

Figure 21.

Exhaustivity marker grouped by structure—French.

The results of the statistical analysis show that the difference between FF with and without seulement is not significant since the MET does not further branch for FF (Figure 22). On the other hand, the presence of the EM in CC and in situ structures significantly worsens the acceptability ratings (p < 0.001).26

Figure 22.

MET output for Exhaustivity marker and Structure—French.

Hence, it can be argued that Focus with [+corrective, +exhaustive] features that is not marked by any type of marker (i.e., an Operator like seulament or a structure like n’a … que) is more acceptable (than those marked by EMs) in French. Furthermore, FF is always excluded, while CC or in situ Foci are both judged as acceptable with no significant differences.

3.2.3. Interim Discussion: French

The data examined show that FF is the least acceptable Focus strategy used by French informants to mark a focused Object with [+corrective, +exhaustive] features, as the acceptability ratings expressed for this construction are consistently below zero, independently of either the realization of an explicit EM or the verb type used in the sentences. This is in line with the previous literature in which it is shown that French is a language with a rigid word order, and the use of FF leads to ungrammatical sentences (cf., among others, Lambrecht, 1994, 2001). On the other hand, the results of the data analysis reported in Figure 18 above show that the acceptability ratings given by informants for in situ Foci and CC are always above zero and that no statistical differences are attested between their mean values (Figure 17). This means that both in situ structures and CC are considered feasible strategies to focalize a [+corrective, +exhaustive] Object (cf., among others, Destruel, 2012; Destruel & De Veaugh-Geiss, 2018).

As for Italian, we also performed a general model for French, including all variables in the same model. First, however, we conducted a Random Forest analysis (Figure 23), which indicates that Structure is the most important variable, verb type has a moderate influence, and EM has only a marginal impact:

Figure 23.

Random Forest for French.

As a consequence, we performed four models, all of which included Informants’ ID as a random effect: Model 1 included Structure, EM, and verb type as fixed effects; Model 2 included only Structure and verb type as fixed effects; Model 3 included only Structure and EM as fixed effects; and Model 4 included only Structure as a fixed effect. The MSE values for the four models are 0.7783366, 0.7928361, 0.8043832, and 0.8164526, respectively, with no statistically significant differences between them.

Thus, considering that there are no significant differences but that Model 1 has the lowest MSE, we report the results for Model 1 in Figure 24 below:

Figure 24.

MET for Model 1 (French).

The results of the general model align with those obtained for the individual variables presented in Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.2.2.

Furthermore, the data regarding CCs and FF align with recent studies arguing that French has a rigid syntactic structure, where CCs have consistently been considered a syntactic device for marking a focused constituent (cf., among others, Lambrecht, 2001; Cruschina, 2012, 2015; Belletti, 2012, 2015).

From a prosodic perspective, the focused constituent should be the most prominent element in the sentence (Truckenbrodt, 1995), while post-focal given elements should be destressed or unaccented (Féry & Samek-Lodovici, 2006). However, since Romance languages (e.g., French and Italian) fail to destress given information in situ (Swerts et al., 2002, among others), FF is excluded because it does not represent the most prominent constituent in the sentence. Conversely, in situ Object Foci are acceptable due to RIGHMOSTNESS, as they bear the most prominent prosodic accent (Bocci & Avesani, 2015).

In this respect, CCs allow the focused constituent to be the most prominent element in the sentence, as the relative clause is realized as a (given) Topic and is thus destressed, following Frascarelli and Hinterhölzl (2007). This is in line with Lambrecht (2001, 2004) (among others), which states that French c’est-CCs are used to mark focused elements that occur in positions in which French disallows prosodic marking.

Thus, according to the analysis conducted by Frascarelli and Ramaglia (2014), a sentence like (18) should have a structure like (19), where the relative clause is realized as a (given) Topic (and thus destressed), allowing the [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus to be the most prominent element from a prosodic standpoint:

| (18) | C’ | est | le | stylo | qu’ | il | a | pris | |

| it | COP | the | pen | that | he | AUX.3SG.PT | take.PP | ||

| ‘It is the pen that he took (and nothing else)’ | |||||||||

| (19) | [GP [TP c’i est [SC ti tk]] [FocP [DP le stilo]k [TopP [DP OPk qu’il a pris ek ]i tTP]]] | ||||||||

Our data also confirm that CCs can be used for corrective and exhaustive effects in French (cf., Belletti, 2005, 2008, 2015).

As for the variable EM, results in Figure 19 and Figure 24 show that informants express higher acceptability judgments when no specific EM is realized in the sentence. Thus, French informants seem to consider implicit exhaustivity significantly more acceptable than the explicit one.

To sum up, data analyses show that French informants express higher acceptability judgments for CC and in situ [+corrective, +exhaustive] focused Objects (with no significant difference). Furthermore, contrary to Italian, French native speakers rate covert EM as more acceptable than overt EM, independently of the verb type.

In conclusion, the results of our analysis show that French speakers tend to convey both [+corrective, +exhaustive] features when using both the in situ strategy and the CC, typically without relying on syntactic markers (i.e., EMs). Thus, in French, implicit exhaustivity (i.e., without an EM) is considered to be more acceptable than the explicit one, differently from Italian.

Thus, it seems plausible to argue that suprasegmental properties might contribute to the realization of [+corrective, +exhaustive] features associated with Foci. In particular, in the absence of explicit syntactic markers, features such as prosodic prominence may facilitate the expression of exhaustivity. However, the data collected through our experiment do not provide us with comprehensive information in these regards; thus, this question is left open for further research.

3.3. Comparison Between Italian and French

The data presented so far show that Italian informants express higher acceptability judgments for in situ foci with an EM, while French speakers rate in situ and CC Focus without an EM as more acceptable. To further validate these results, we conducted an MET on the entire dataset to determine whether the variable Language (i.e., Italian or French) interacts with Structure and EM.27 The output of the MET analysis, which included Language as an independent variable (Figure 25), confirms the findings reported in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2. Specifically, the results indicate that Language interacts with both Structure and EM. The MET results once again show that the preferred strategies are in situ with EM for Italian (in red) and in situ without EM and CC without EM for French (in blue). To further verify this claim, we performed a Kruskal–Wallis test, which confirmed that there are no significant differences between these three strategies (p = 0.06).

Figure 25.

MET output for Language, Structure, and EM.

Thus, the results indicate that the three structures under examination (i.e., in situ with EM for Italian, and in situ and CC without EM for French) are used in both Italian and French to mark [+corrective, +exhaustive] foci:

Finally, the results shown in Figure 25 are in line with our predictions, according to which the presence of both [+corrective] and [+exhaustive] features, especially in combination with an EM, could make FF more acceptable in Italian than in French (p = 0.001) (in green). However, it is important to note that FF remains significantly less accepted than in situ and CC (for both languages) and should, therefore, still be considered a dispreferred strategy overall.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the acceptability of different Focus strategies in Italian and French, considering the influence of syntactic rigidity, the presence of an explicit EM, and argument structure. Our research was guided by the following questions:

- (i)

- Can different degrees of “rigid syntax” influence the acceptance of different Focus strategies in the two languages under analysis, particularly in relation to the complex Focus type [+corrective, +exhaustive]?

- (ii)

- Can the presence or absence of an explicit EM affect the acceptability of the relevant sentences in the two languages under investigation?

- (iii)

- Can different argument structures in the vP affect the movement of the focused constituent?

The results show that FF is the least acceptable strategy in both languages, contradicting our expectation that Italian, being syntactically less rigid than French, would more readily accept FF. Instead, FF consistently receives negative acceptability ratings, reinforcing previous findings that French has a strict SVO order (Lambrecht, 1994, 2001), while Italian predominantly favors in situ Focus for informative, corrective, and mirative functions (Carella, 2019; Frascarelli & Stortini, 2019). Thus, while syntactic rigidity does influence the distribution of Focus strategies, Italian does not exhibit a higher tolerance for FF than French, contrary to our initial hypothesis.

Regarding the effect of an explicit EM, the results reveal a strong cross-linguistic asymmetry. In Italian, an EM significantly increases acceptability, particularly for in situ Focus, confirming the idea that explicit marking of exhaustivity enhances acceptability (Kiss, 1998). In contrast, in French, sentences without an EM are rated as more acceptable than those with an EM, suggesting a preference for implicit exhaustivity. This challenges our expectation that EMs would improve acceptability in both languages and indicates that French relies on different mechanisms to convey [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus, possibly prosodic cues.

As for the role of argument structure, the MET and Random Forest analyses indicate that verb type does not significantly affect the acceptability of Focus strategies in Italian. However, in French, verb type has a moderate influence on acceptability ratings. Specifically, the presence of an intervening subject in transitive and unergative constructions could create intervention effects that make movement-based strategies less acceptable. This aligns with Relativized Minimality (Rizzi, 1990, 2004), which predicts that intervention effects arise when an element of the same featural class structurally intervenes between a moved constituent and its base position. In the case of FF in French, the subject may act as an intervener, reducing the acceptability of movement-based Focus strategies.

Crucially, the fact that CC remains an acceptable alternative to in situ Focus in French suggests that CCs might serve as a repair strategy, circumventing intervention effects by allowing Focus movement to occur within a dedicated syntactic domain. This aligns with analyses arguing that c’est-clefts provide an alternative pathway for Focus realization when movement is otherwise blocked (Belletti, 2008; Frascarelli & Ramaglia, 2014).

However, an open question remains regarding why verb type has an effect in French but not in Italian. Future research should explore whether prosodic, morphological, or syntactic factors contribute to the observed difference.

The comparison between Italian and French further highlights their distinct preferences in Focus realization. The data show the following:

- (a)

- Italian speakers prefer in situ Focus with an explicit EM;

- (b)

- French speakers rate in situ and cleft structures (CC) without an EM as equally acceptable.

Importantly, these strategies serve equivalent functions in the two languages.

Interestingly, although FF was globally dispreferred in both languages, the data suggest that FF with an EM may be judged slightly more acceptable in Italian than in French. This aligns with our theoretical prediction that the co-occurrence of [+corrective] and [+exhaustive] features—particularly when overtly marked—could increase the acceptability of marked Focus configurations. However, it must be emphasized that FF remains among the least accepted strategies overall and cannot be considered a preferred option in either language. The lack of a clear cross-linguistic asymmetry in FF acceptability prompts further reflection.

A possible explanation for why the expected greater tolerance for FF in Italian was not confirmed and why French showed no increase in FF acceptability under [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus may lie in the particular interpretive demands imposed by this feature combination. The simultaneous encoding of strong correction and exhaustivity may restrict the range of syntactic realizations available, favoring structurally stable and semantically transparent options such as in situ Focus or CCs. While Italian is generally considered to have a more flexible word order than French, this flexibility may be neutralized by the need for clarity in expressing complex discourse functions. In French, moreover, the combination of [+corrective, +exhaustive] features does not seem sufficient to license FF, possibly due to stricter syntactic constraints and a stronger reliance on clefting as the canonical form for CF.

Additionally, in both languages, prosodic cues likely play a key role in signaling fine-grained Focus distinctions. Since the present study used written stimuli without controlled intonation, the low acceptability of FF may partly reflect the absence of a marked prosodic contour, which is often crucial in Focus interpretation. Future research should further investigate the interplay between syntax, semantics, and prosody in the realization of complex Focus types across languages.

In this respect, one crucial limitation of our study is that it does not allow us to determine whether the unacceptability of FF in Italian is influenced by the prosodic contour assigned to Focus. Future research could address this issue by incorporating prosodic analysis into acceptability judgment tasks or by testing spoken stimuli with controlled intonation patterns.

Furthermore, while EMs enhance acceptability in Italian, they are disfavored in French, where implicit exhaustivity is preferred. This cross-linguistic difference suggests that suprasegmental features, such as prosody, may play a more central role in the realization and interpretation of [+corrective, +exhaustive] Focus in French. However, since the present dataset does not include prosodic information, further investigation is needed to clarify how prosody interacts with different Focus strategies across Romance languages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and T.S.; methodology, M.C. and T.S.; software, M.C.; validation, M.C. and T.S.; formal analysis, M.C. and T.S.; investigation, M.C. and T.S.; resources, M.C. and T.S.; data curation, M.C. and T.S.; writing—Section 1.3, Section 1.4, Section 1.4.1, Section 2.1, Section 3.1, Section 3.1.1, Section 3.1.2, Section 3.1.3, and Section 3.3, M.C.; writing—Section 1, Section 1.1, Section 1.2, Section 1.4.2, Section 1.4.3, Section 3.2, Section 3.2.1, Section 3.2.2, and Section 3.2.3, T.S.; writing—Section 1.5, Section 2, and Section 4, M.C. and T.S.; review and editing, M.C. and T.S.; visualization, M.C. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable (ethical approval is not required for an anonymous judgment test).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable (informed consent is not required for an anonymous judgment test).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in OSF at [https://osf.io/ku27q/?view_only=c60f88bcff14435bbb534ca4b1003aff, accessed on 11 August 2024].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and constructive suggestions, which greatly contributed to enhancing the clarity and rigor of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| TRANS01 Context: A: Che cosa ha preso Marco dall’astuccio? ‘What did Marco take from the pencil case?’ B: La penna, la matita e la gomma. ‘The pen, the pencil and the eraser’ In situ a. C: Guarda bene! Ha preso la penna! ‘Look better! (He) took the pen!’ b. C: Guarda bene! Ha preso solo la penna! ‘Look better! (He) only took the pen! FF a. C: Guarda bene! La penna ha preso! Lit: ‘Look better! The pen (he) took!’ b. C: Guarda bene! Solo la penna ha preso! Lit: ‘Look better! Only the pen (he) took!’ CC a. C: Guarda bene! È la penna che ha preso! ‘Look better! It is the pen that (he) took!’ b. C: Guarda bene! È solo la penna che ha preso! ‘Look better! It is only the pen that (he) took!’ | Figure TRANS01 |

| TRANS02 Context: A: Quali giochi ha fotografato Tania? ‘Which toy(s) did Tania photograph?’ B: Il peluche, la bambola e il sonaglio. ‘The soft toy, the doll and the rattle’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. Ha fotografato la bambola. ‘Look at the picture. (She) photographed the doll’ a. C: Guarda la foto. Ha fotografato solo la bambola. ‘Look at the picture. (She) only photographed the doll’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. La bambola ha fotografato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The doll (she) photographed’ a. C: Guarda la foto. Solo la bambola ha fotografato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the doll (she) photograph’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È la bambola che ha fotografato. ‘Look at the picture. It is the doll that (he) photographed!’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo la bambola ha fotografato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the doll that (he) photographed!’ | Figure TRANS02 |