Corrective and Exhaustive Foci: A Comparison Between Italian and French

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Corrective Focus

| (1) | a. | L’ | altra | sera | a | teatro, | Maria | si | era | messa | |||||||

| The | other | evening | at | theatre | Maria | 3sg.cl | aux.3sg.pt | wear.pp | |||||||||

| uno | straccetto | di | H&M. | ||||||||||||||

| a | cheap dress | of | H&M | ||||||||||||||

| ‘Yesterday at the theatre, Maria wore a cheap dress from H&M.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | Si | era | messa | un | Armani, | ||||||||||||

| 3sg.cl | aux.3sg.pt | wear.pp | an | Armani | |||||||||||||

| non | uno | straccetto | di | H&M. | |||||||||||||

| neg | a | cheap dress | of | H&M | (Focus in situ) | ||||||||||||

| ‘(She) wore an Armani (dress), not a cheap dress from H&M’ | |||||||||||||||||

| (1b′) | Un | Armani | si | era | messa, | |||||

| an | Armani | 3sg.cl | aux.3sg.im | wear.pp | ||||||

| non | uno | straccetto | di | H&M. | ||||||

| neg | a | cheap dress | of | H&M | (FF) | |||||

| ‘(She) wore an Armani (dress), not a cheap dress from H&M’ | ||||||||||

| (2) | a. | Non, Lilou a | porté | le | gilet | hier. | (in situ) | |||||||||||||||

| neg, Lilou aux.3sg.pt | bring.pp | the | waistcoat | yesterday | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘No, Lilou wore the waistcoat yesterday.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Albert | a | appelé | son | fils. (Context for 2b’ and 2b’’) | |||||||||||||||||

| Albert | aux.3sg.pt | call.pp | 3sg.poss | son | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Albert called his son.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b′. | Non, c’ | est | sa | mère | qu’ | il | a | appelée (pas son fils). (CC) | ||||||||||||||

| neg, it | cop | 3sg.poss | mother | that | he aux.3sg.pt call.pp | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘No, it is his mother that-he has called (not his son)’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b″. | *Non, | sa | mère | il | a | appelé (pas son fils). | (FF) | |||||||||||||||

| neg, | 3sg.poss | mother | he | aux.3sg.pt | call.pp | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘No, his mother he has called (not his son)’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

1.2. Focus and Exhaustivity

| (3) | Context: “A: What did you bring to the party?” | ||||

| B: | Bort | ès | sajtot | hoztam. | |

| wine.acc | and | cheese.acc | bring.1sg.pst | ||

| ‘I brought wine and cheese’ (#and also some bread)3. | |||||

| (4) | a. | It was a hat that Mary picked for herself. | |||||||||||||

| b. | Mary picked herself a hat. | ||||||||||||||

| (5) | a. | È | un | cappello | che | Maria | ha | comprato | |||||||

| be.3sg.prs | a | hat | that | Maria | aux.3sg.prs | buy.pp | |||||||||

| (#e | anche | un | ombrello) | ||||||||||||

| and | also | an | umbrella | ||||||||||||

| ‘It is a hat that Maria bought (#and also an umbrella)’ | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Maria | ha | comprato | un | cappello. | ||||||||||

| Maria | aux.3sg.prs | buy.pp | a | hat | |||||||||||

| ‘Maria bought a hat.’ | |||||||||||||||

| (6) | C’ | est | Batman | qui | a | pour | mission | d’attraper | ||

| It | cop | Batman | that | aux.3sg.prs | for | mission | to.catch | |||

| les | cambrioleurs | (# and aussi Robin) | ||||||||

| the | burglars | (# and also Robin) | ||||||||

| ‘It is Batman who has the mission of catching thieves (# and also Robin).’ | ||||||||||

| (Destruel, 2012, p. 95) | ||||||||||

| (7) | a. | Per la | cena | di | ieri | tutti | hanno | cucinato | ||||||||||||||||||

| for the | dinner | of | yesterday | everybody | aux.3pl.prs | cook.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||

| due | o | tre | cose. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| two | or | three | things | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Yesterday, for the dinner, everyone cooked two or three different things.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Leo | ha | cucinato | solo | la | lasagna. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Leo | aux.3sg.prs | cook.pp | only | the | lasagna | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Leo only cooked lasagna’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b′. | #Leo | ha | cucinato | solo | la | lasagna | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Leo | aux.3sg.prs | cook.pp | only | the | lasagna | |||||||||||||||||||||

| e | anche | un | arrosto. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| and | also | a | roastbeef | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘#Leo only cooked lasagna and also a roastbeef’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (8) | Jacques | n’ | aime | que | Marie / | Jacques | aime | |||||

| Jacques | neg | love.3sg.prs | that | Marie | Jacques | love.3sg.prs | ||||||

| seulement | Marie | (# et | aussi | Lulu) | ||||||||

| only | Marie | (# and | also | Lulu) | ||||||||

| ‘Jack loves only Mary (# and also Lulu)’ | (adapted from König, 1991, p. 37) | |||||||||||

1.3. Combination of Features

| (9) | Information Focus < Exhaustive Focus < Mirative Focus < Corrective Focus |

1.4. Focus Strategies

1.4.1. The In Situ Strategy

| (10) | Gli | ho | dato | un | libro. |

| cl.3sg.m | aux.3sg.prs | give.pp | a | book | |

| ‘I gave him a book.’ | (Frascarelli, 2000) | ||||

| (11) | a. | Arnim a | escaladé | la | montagne. |

| Arnim aux.3sg.prs | climbed.pp | the | mountain | ||

| ‘Arnim has climbed the mountain’ | |||||

| a’. | Arnim a | escaladé | la | montagne. | |

| Arnim aux.3sg.prs | climbed.pp | the | mountain. | ||

| ‘Arnim has climbed the mountain’ | (Féry, 2001, p. 162) | ||||

1.4.2. Focus Fronting

| (12) | a. | Gianni ha | invitato | Lucia. | |||||||||

| John | aux.3sg.prs | invite.pp | Lucy | ||||||||||

| ‘John invited Lucy.’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | Marina | ha | invitato. | ||||||||||

| Marina (he) | aux.3sg.prs | invite.pp | |||||||||||

| ‘Marina he invited.’ | (adapted from Bianchi, 2013, p. 193) | ||||||||||||

| (13) | ? Marina | il | a | invité. | |||||||||

| Marina | he | aux.3sg.prs | invite.pp | ||||||||||

| ‘Marina he invited’ | (Larrivée, 2022, p. 184) | ||||||||||||

1.4.3. Cleft Constructions

| (14) | a. | È | Gianni | che | i | ragazzi | hanno | salutato | |||||||||

| cop | Gianni | that | the | boys | aux.3pl.prs | greet.pp | |||||||||||

| “It is Gianni that the boys have greeted” | (Belletti, 2008, p. 191) | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | C’ | est | le | cheval | que | le | fermier | a | brossé. | ||||||||

| it | cop | the | horse | that | the | farmer | aux.3sg.prs | brush.pp | |||||||||

| ‘It’s the horse that the farmer brushed.’ | (Destruel, 2012, p. 101) | ||||||||||||||||

| (15) | It is a book that I gave John. |

| (15′) |  |

1.5. Research Question and Predictions

- (i)

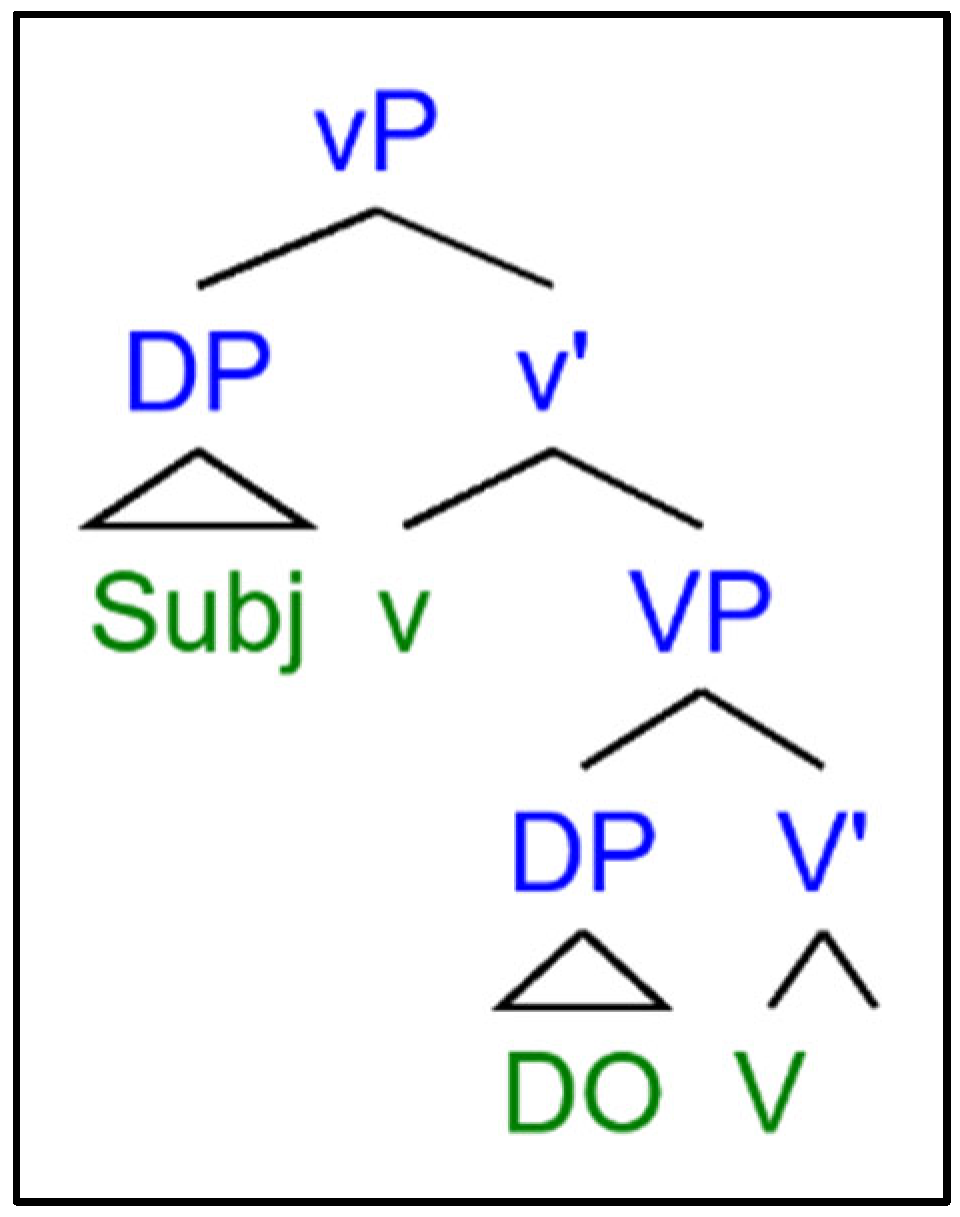

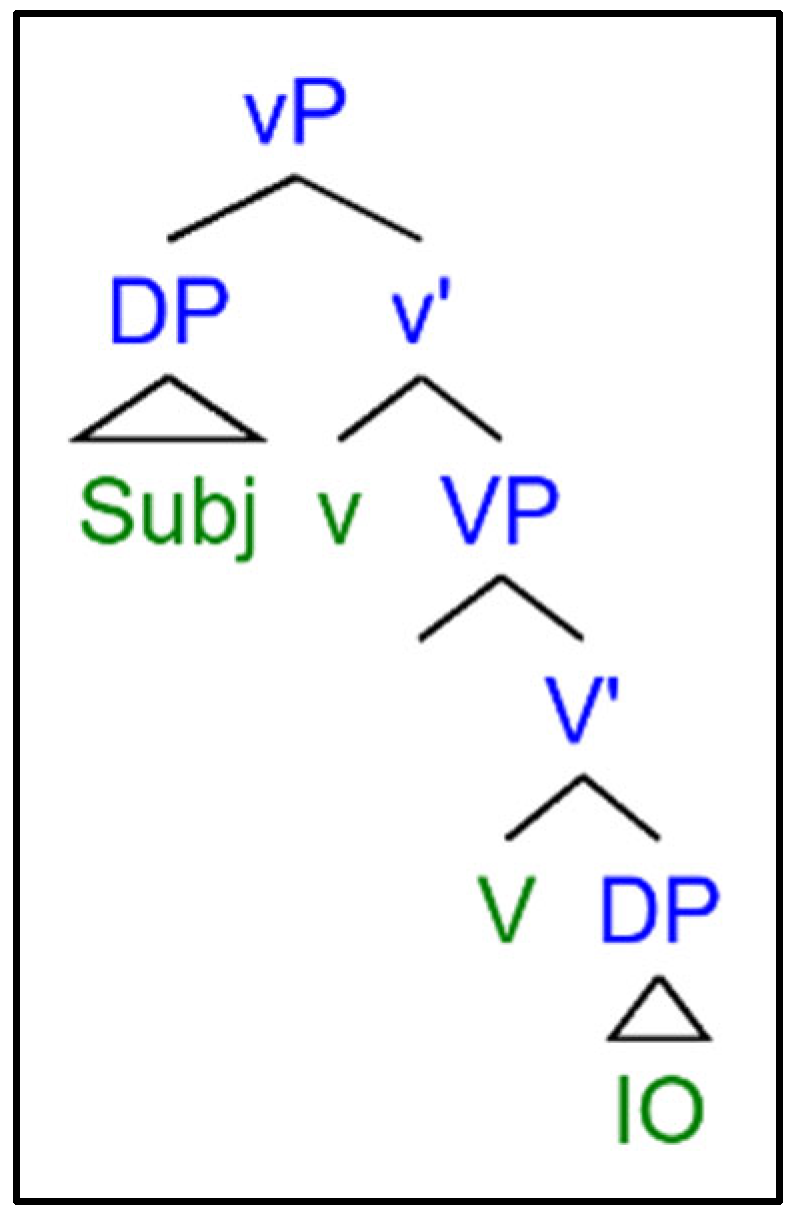

- Transitive verbs—the subject–argument is originally merged in Spec,vP, while the object–argument is merged in Spec,VP, as shown in Figure 1 below.

- (ii)

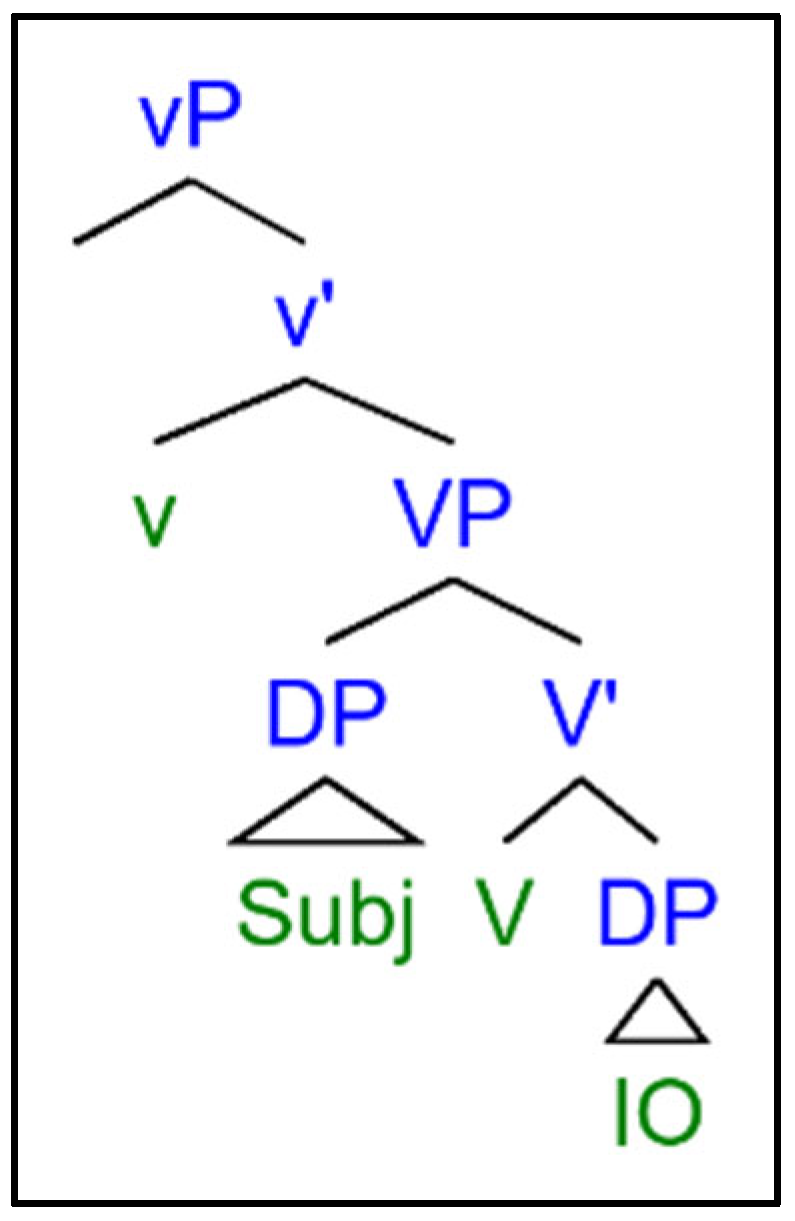

- Unergative verbs—the subject–argument is merged in Spec,vP, and the object–argument (i.e., a Locative Indirect Object) is merged in Compl,VP, as shown in Figure 2 below.

- (iii)

- Unaccusative verbs (motion or state)—the subject–argument is merged in Spec,VP, while the object–argument is merged in Compl,VP (cf., Kratzer, 1994; Chomsky, 1995; von Stechow, 1995, among others), as shown in Figure 3 below.9

- (i)

- Can different degrees of “rigid syntax” influence the acceptance of different Focus strategies in the two languages under analysis, particularly in relation to the complex Focus type [+corrective, +exhaustive]?

- (ii)

- Can the presence or absence of an explicit EM affect the acceptability of the relevant sentences in the two languages under investigation?

- (iii)

- Can different argument structures in the vP affect the movement of the focused constituent?

2. Materials and Methods

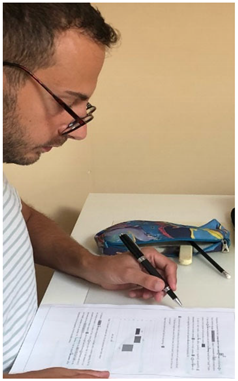

| (16) | Italian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Context: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A: | Che cosa | ha | preso | Marco | dall’ | astuccio? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| what | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | Marco | from-the | pencil case | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘What did Marco take from the pencil case?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B: | La | penna, | la | matita | e | la | gomma. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the | pen | the | pencil | and | the | eraser | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The pen, the pencil and the eraser.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (i) | In situ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Guarda | bene! | Ha | preso | la | penna! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | the | pen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! (He) took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Guarda | bene! | Ha | preso | solo | la | penna! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | only | the | pen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! (He) only took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (ii) | FF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Guarda | bene! | La | penna | ha | preso! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | the | pen | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look better! The pen (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Guarda | bene! | Solo | la | penna | ha | preso! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | only | the | pen | aux.3sg.pt | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look better! Only the pen (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (iii) | CC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Guarda | bene! | È | la | penna | che | ha | preso! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | cop | the | pen | that | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! It is the pen that (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Guarda | bene! | È | solo | la | penna | che | ha | preso! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | well | cop | only | the | pen | that | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look better! It is only the pen that (he) took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (17) | French | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Context: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A: | Qu’ | a | pris | Marc | de | la | trousse? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| what | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | Marco | from | the | pencil case | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘What did Marco take from the pencil case?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B: | Le | stylo, | le | crayon | et | la | gomme. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the | pen | the | pencil | and | the | eraser | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The pen, the pencil and the eraser.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (i) | In situ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Il | a | pris | le | stylo! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | the | pen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! He took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Il | n’ | a | pris | que | le | stylo. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | he | neg | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | that | the | pen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! He only took the pen!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (ii) | FF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Le | stylo | il | a | pris! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | the | pen | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look better! The pen he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | Seulement | le | stylo | il | a | pris! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | only | the | pen | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lit: ‘Look at the picture! Only the pen he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (iii) | CC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | C’ | est | le | stylo | que | il | a | pris! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | it | cop | the | pen | that | he | aux.3sg.prs | take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! It is the pen that he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | C: | Regarde | la | photo! | C’ | est | seulement | le | stylo | que | il | a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| look | the | picture | it | cop | only | the | pen | that | he | aux.3sg.prs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| pris! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| take.pp | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Look at the picture! It is only the pen that he took!’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

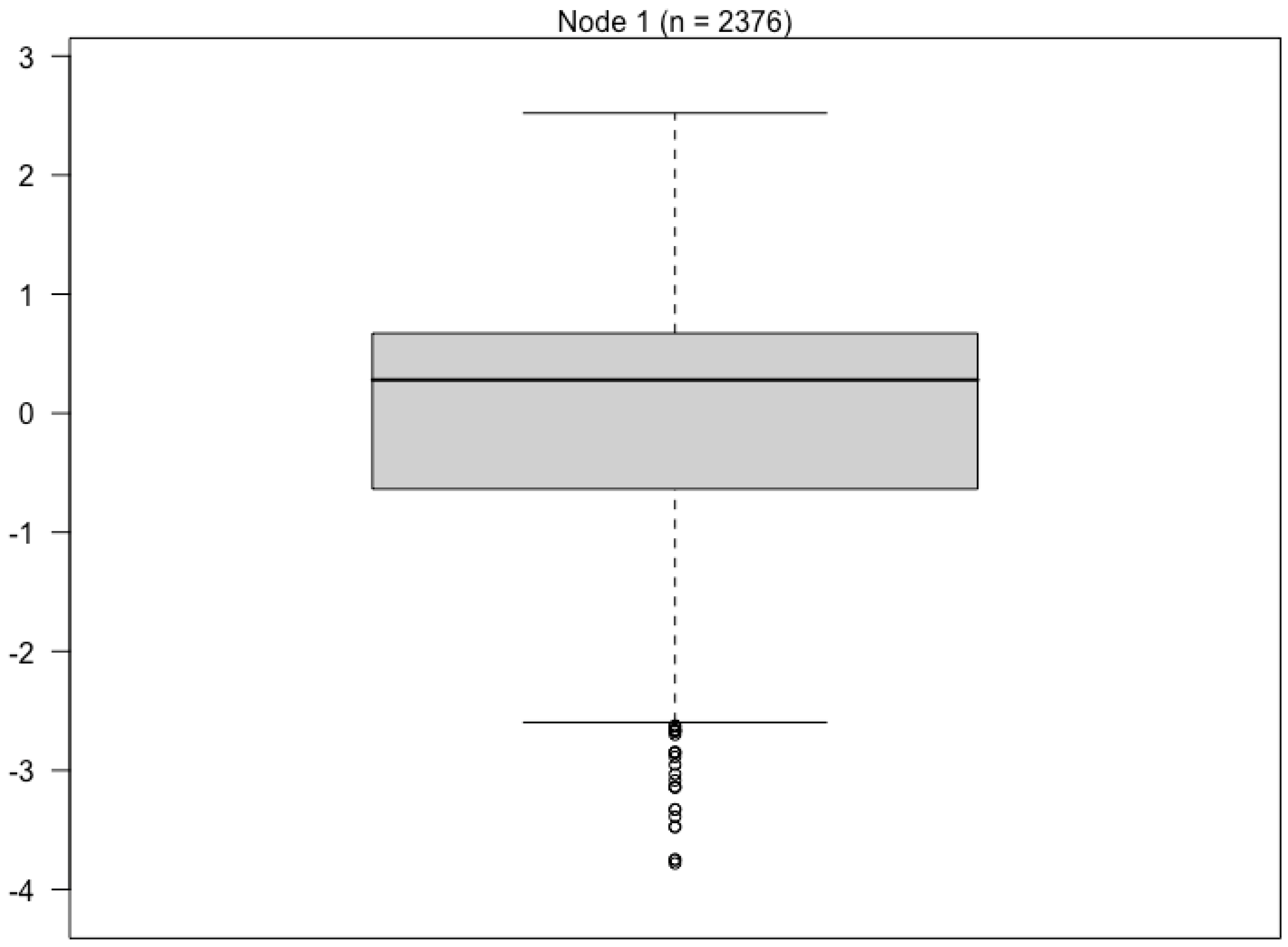

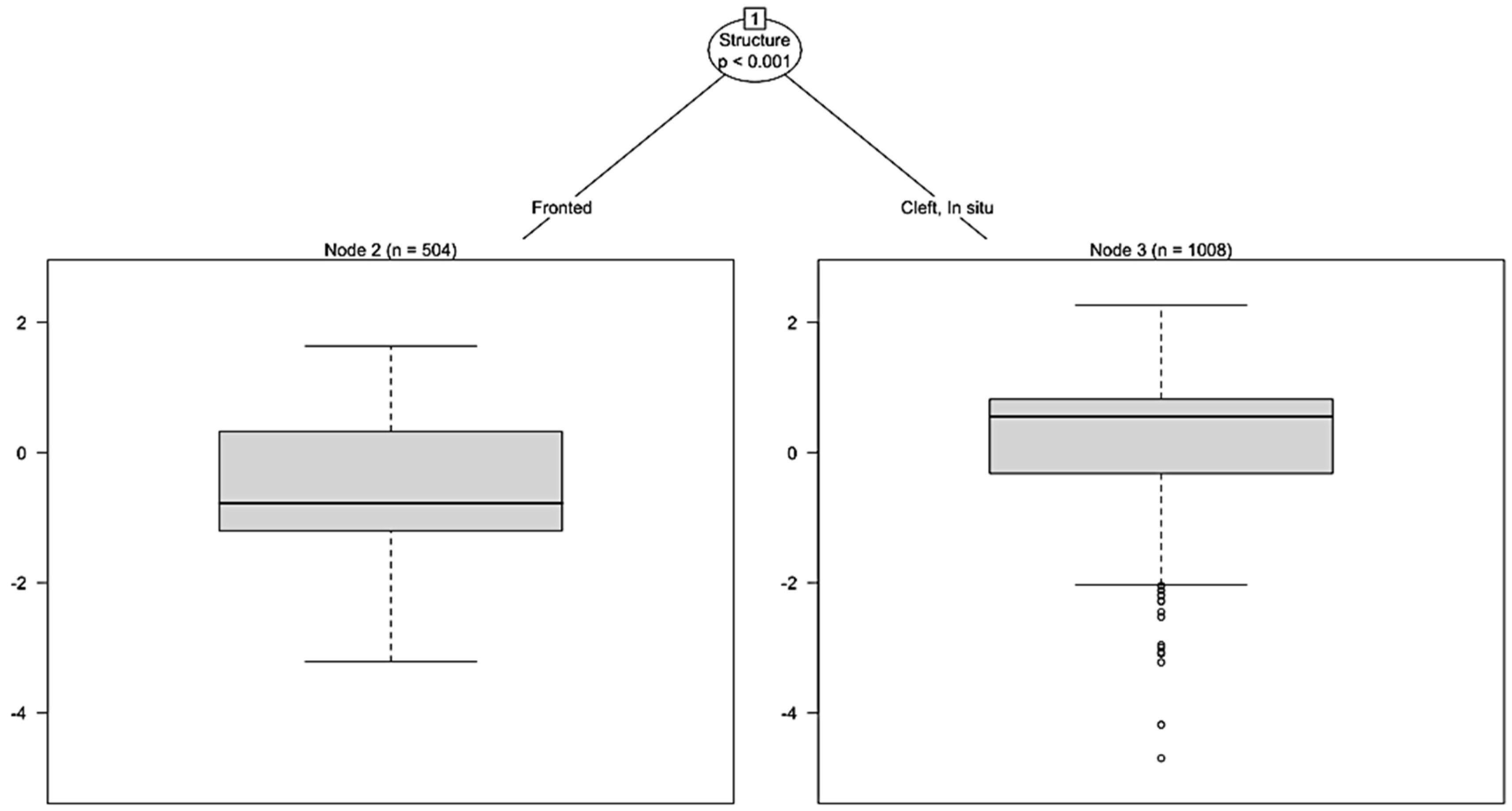

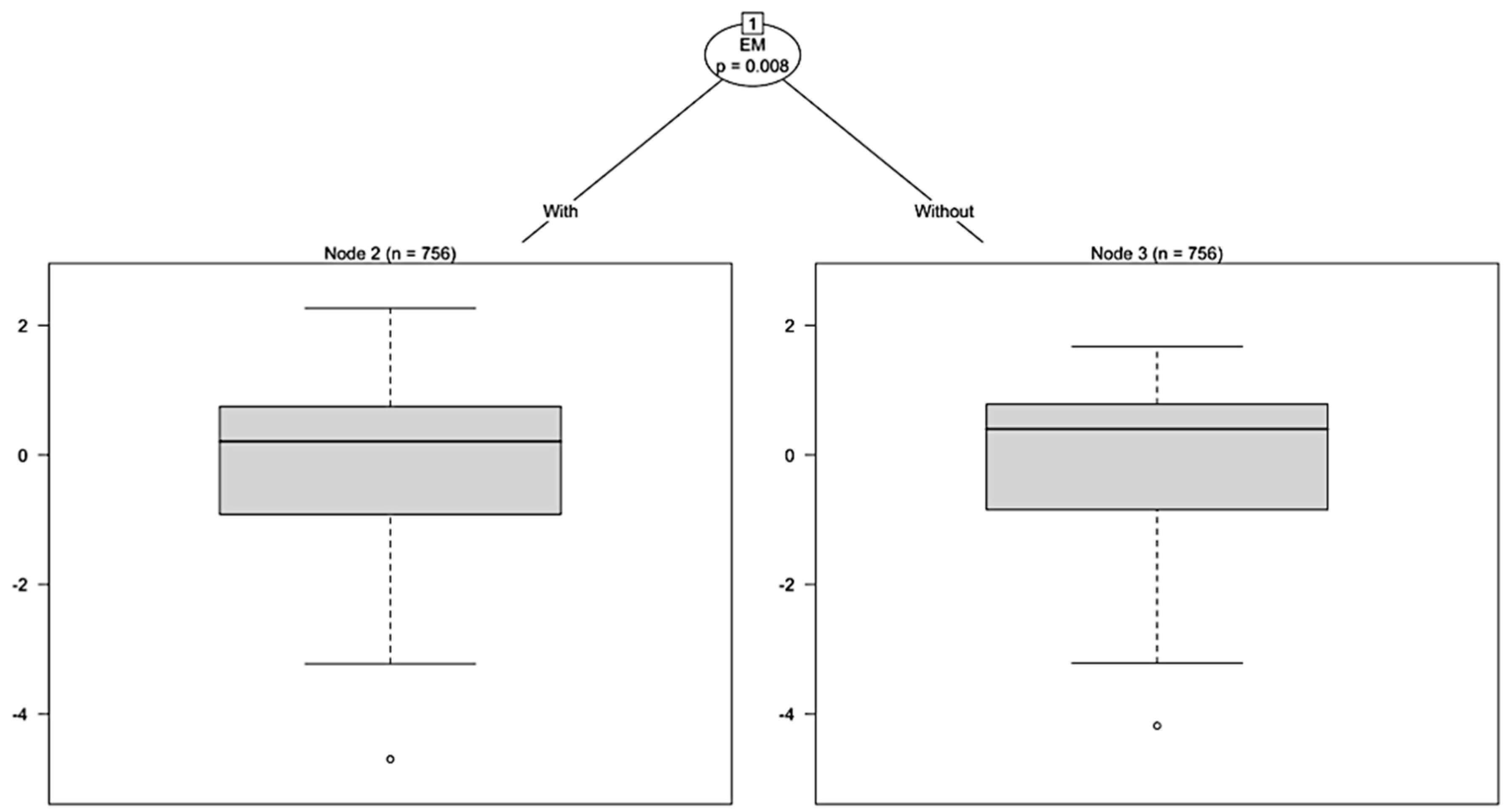

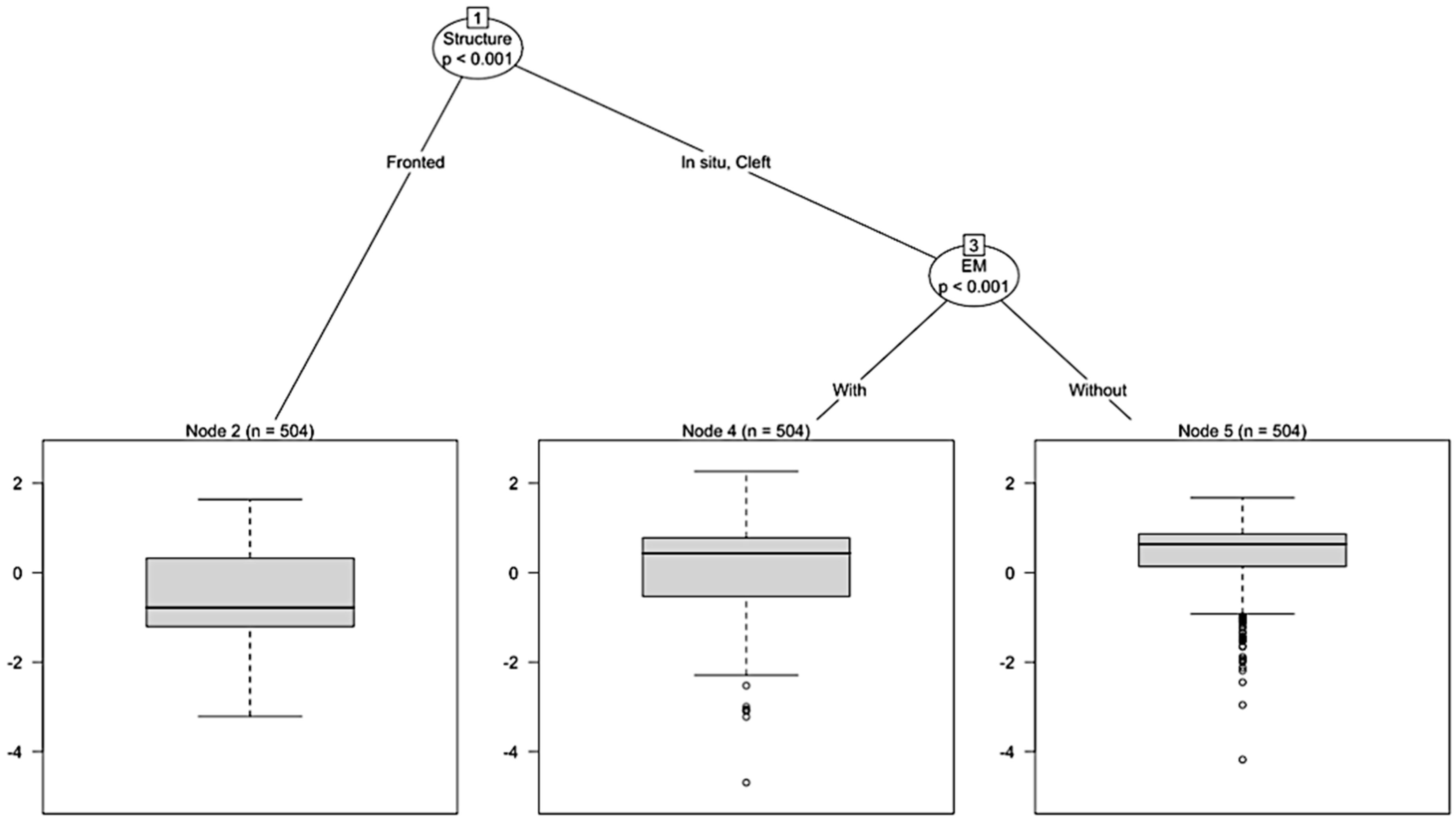

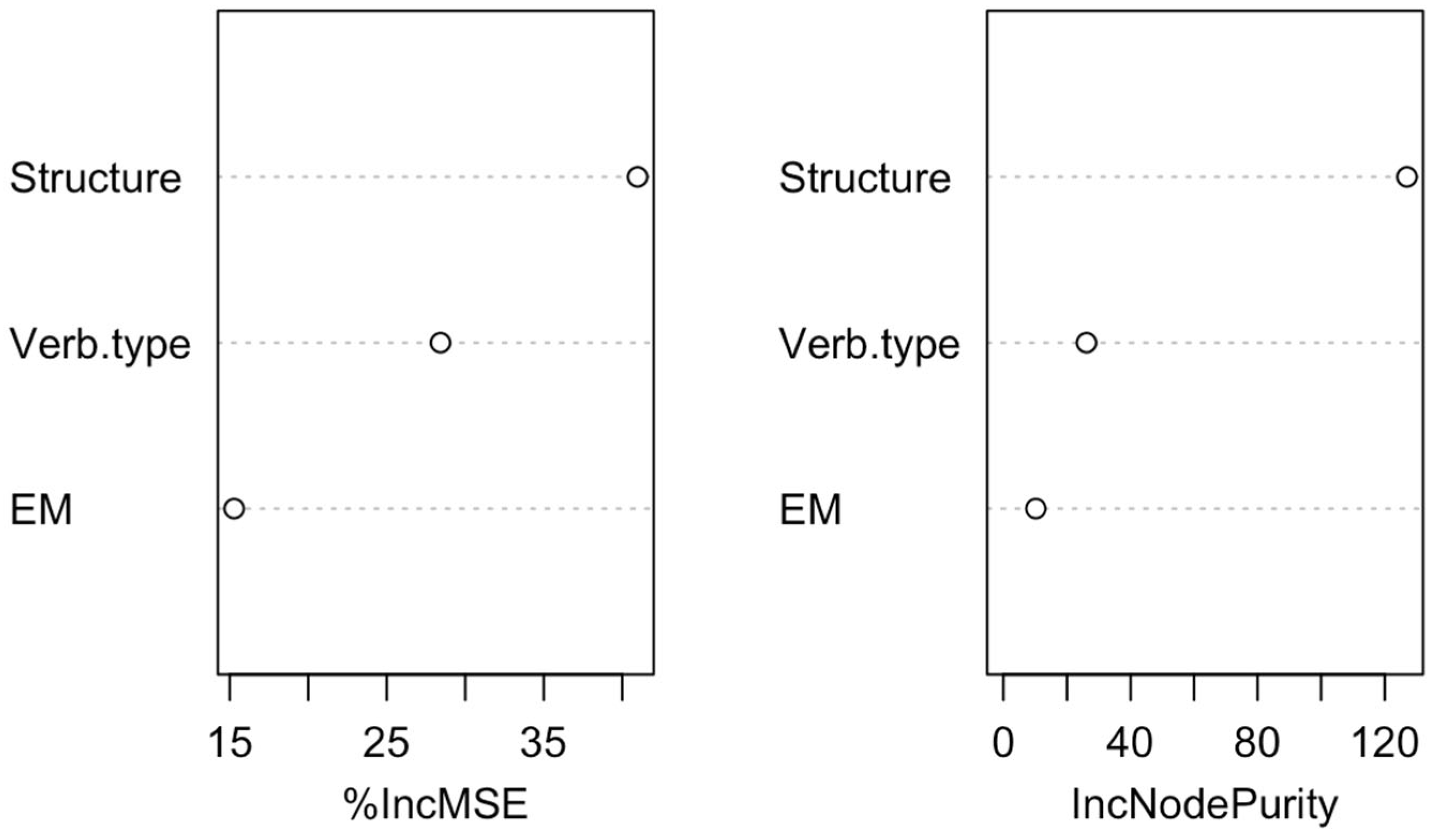

2.1. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

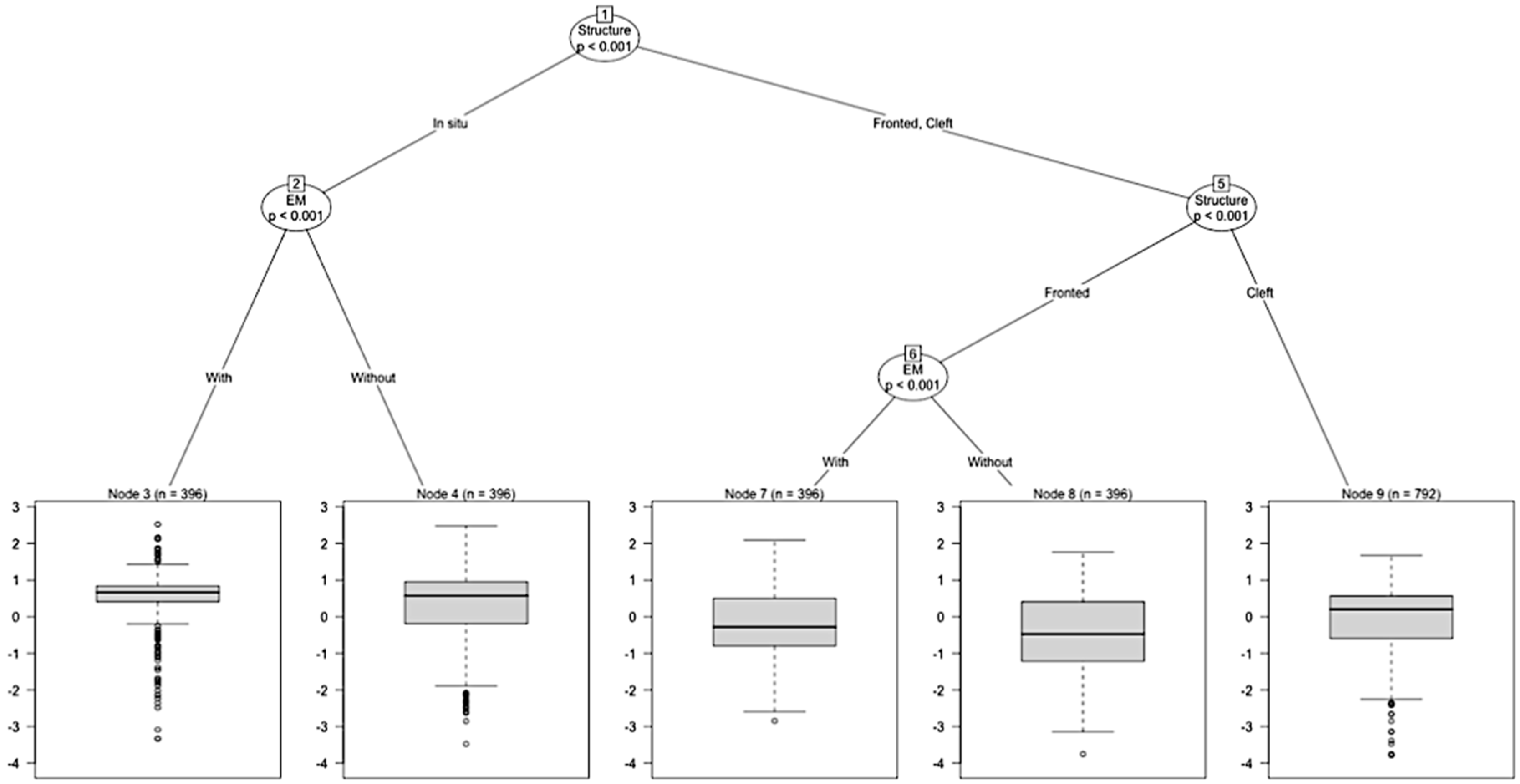

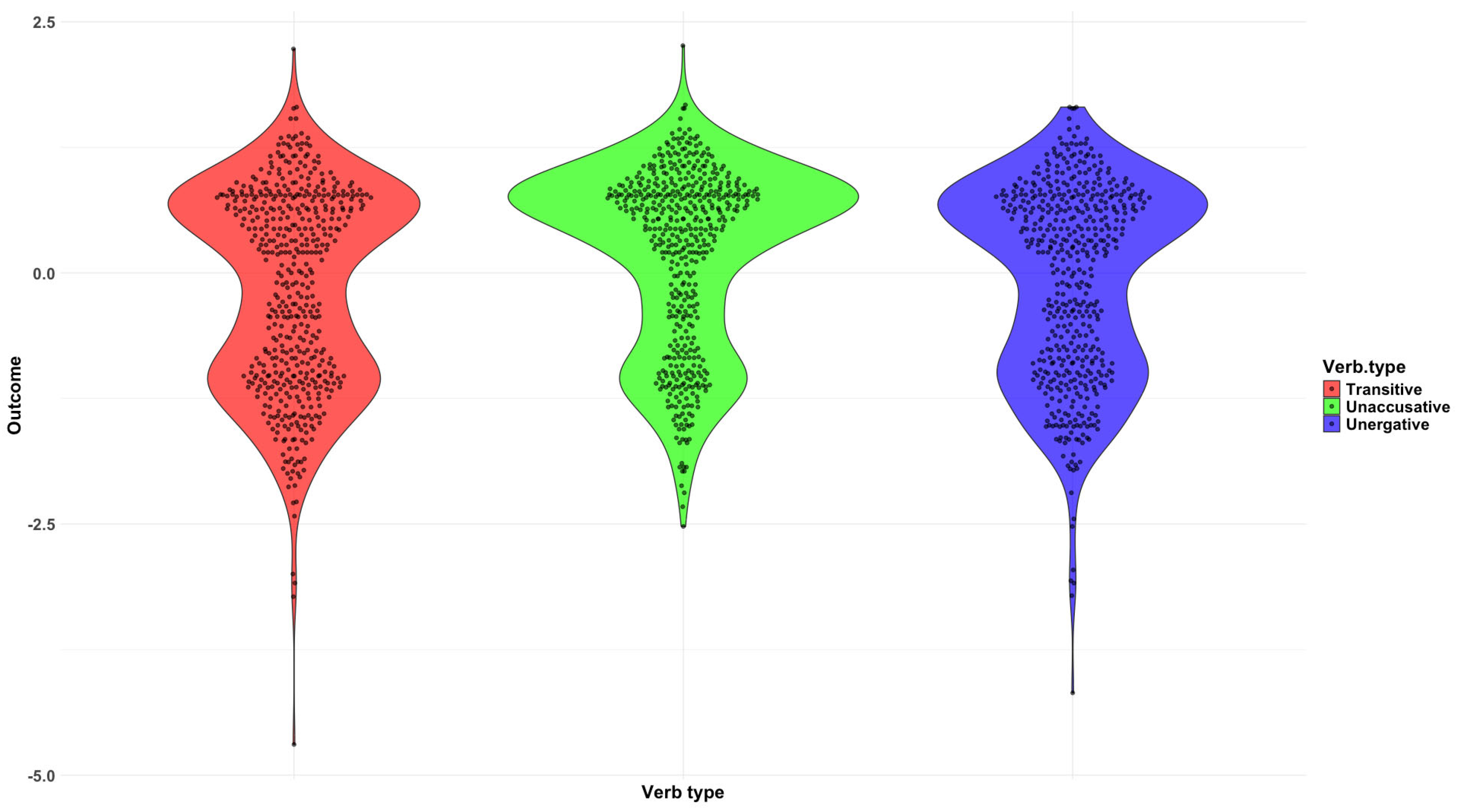

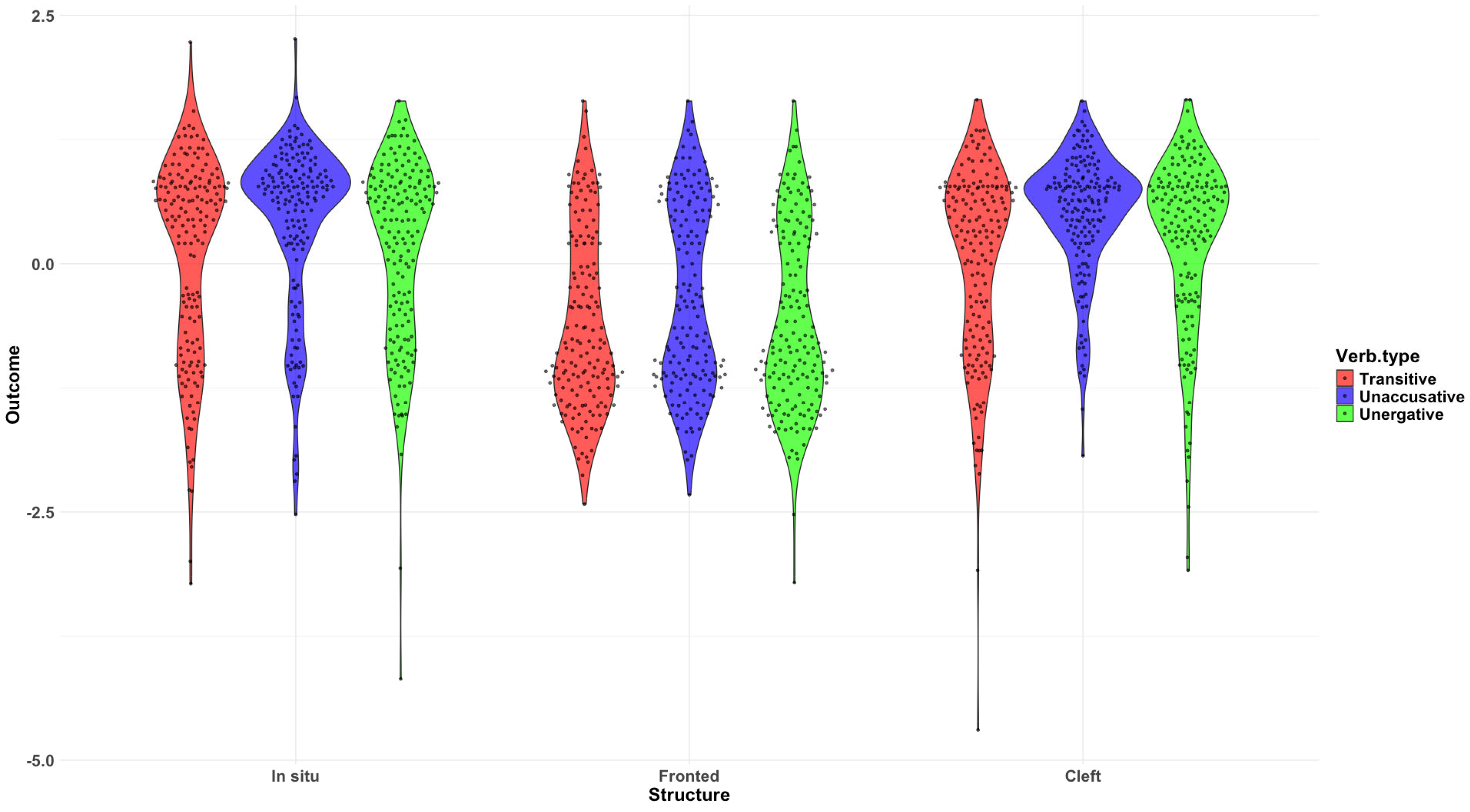

3.1. Data Analysis: Italian

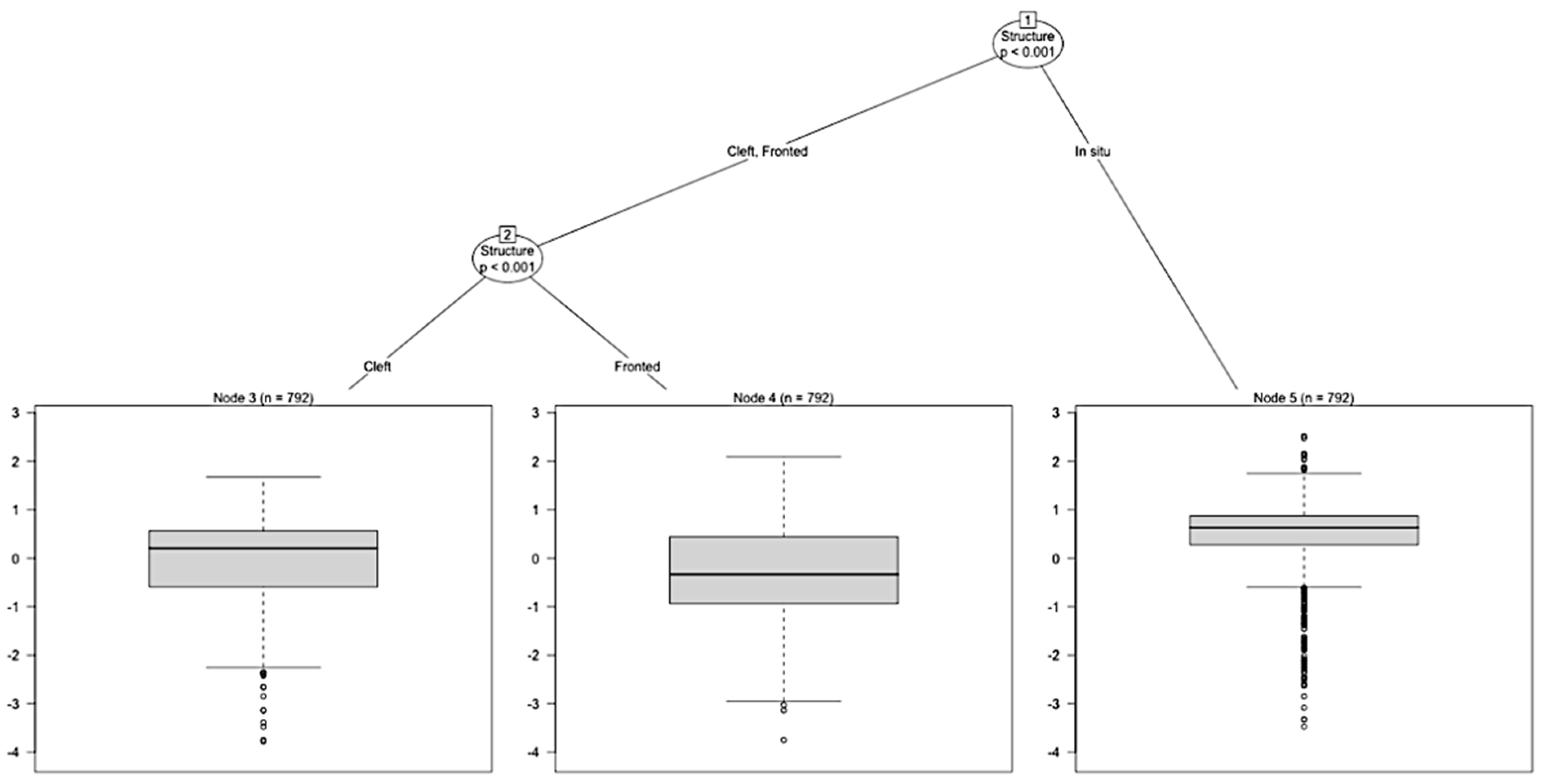

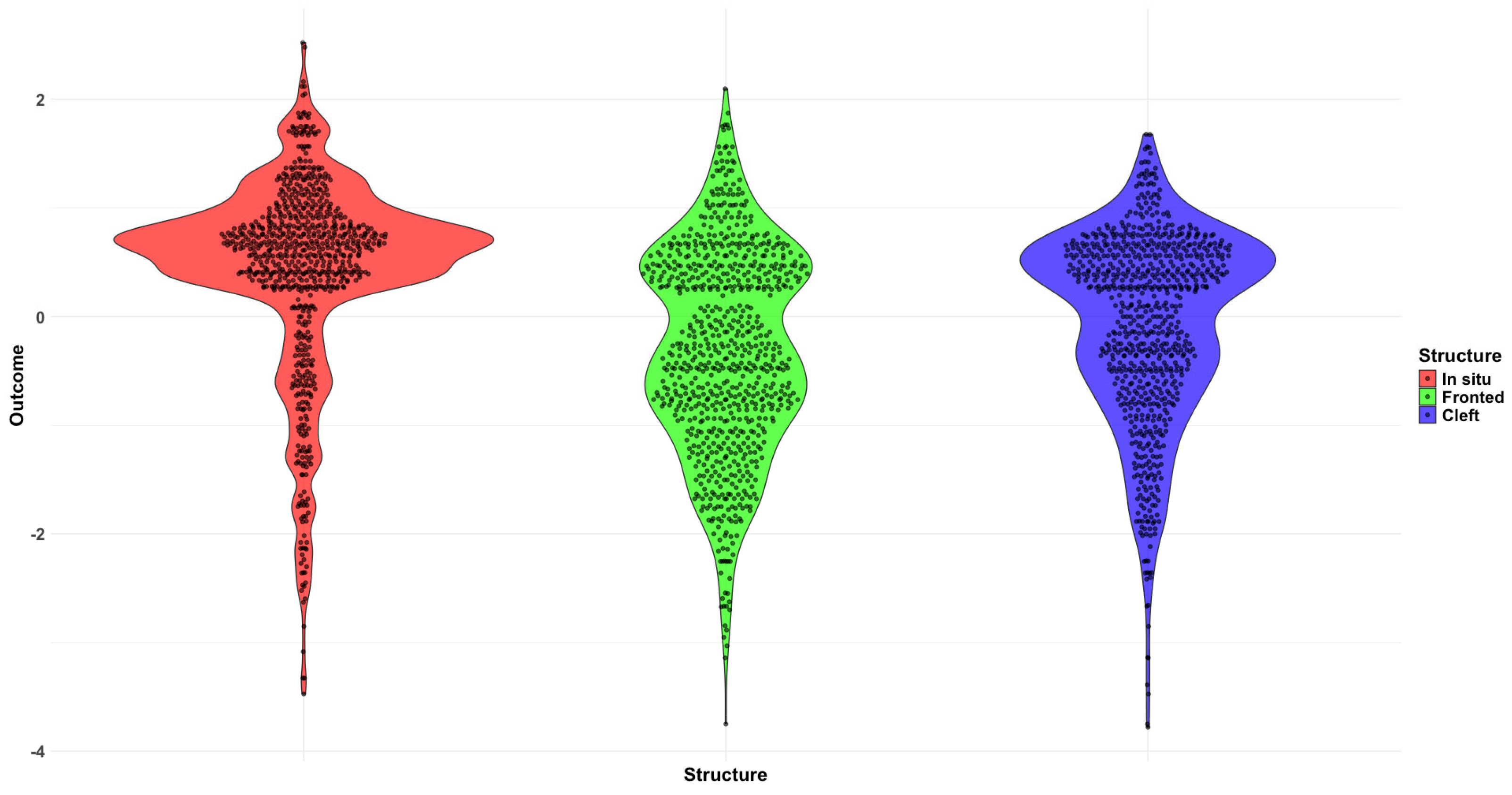

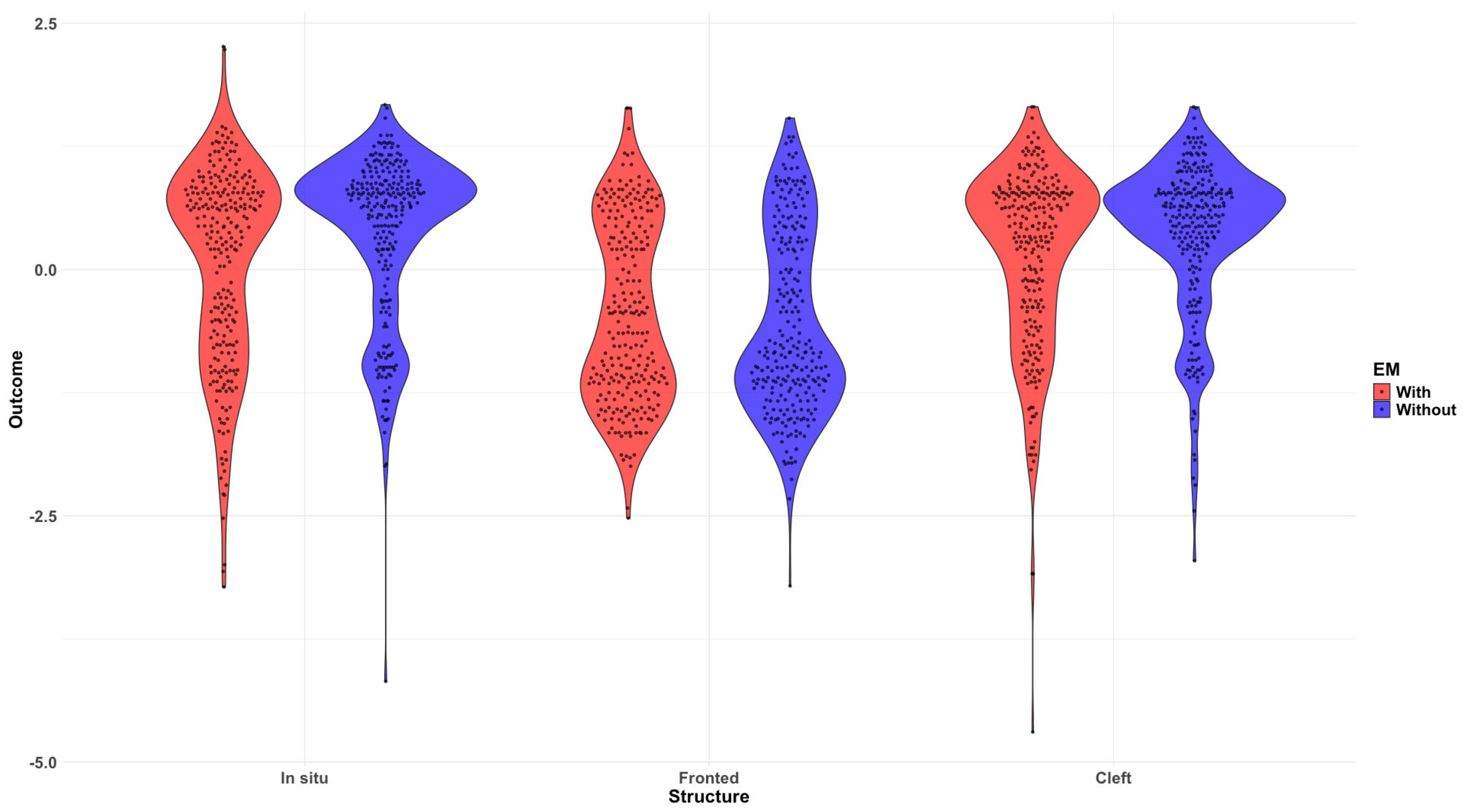

3.1.1. Structure: Italian

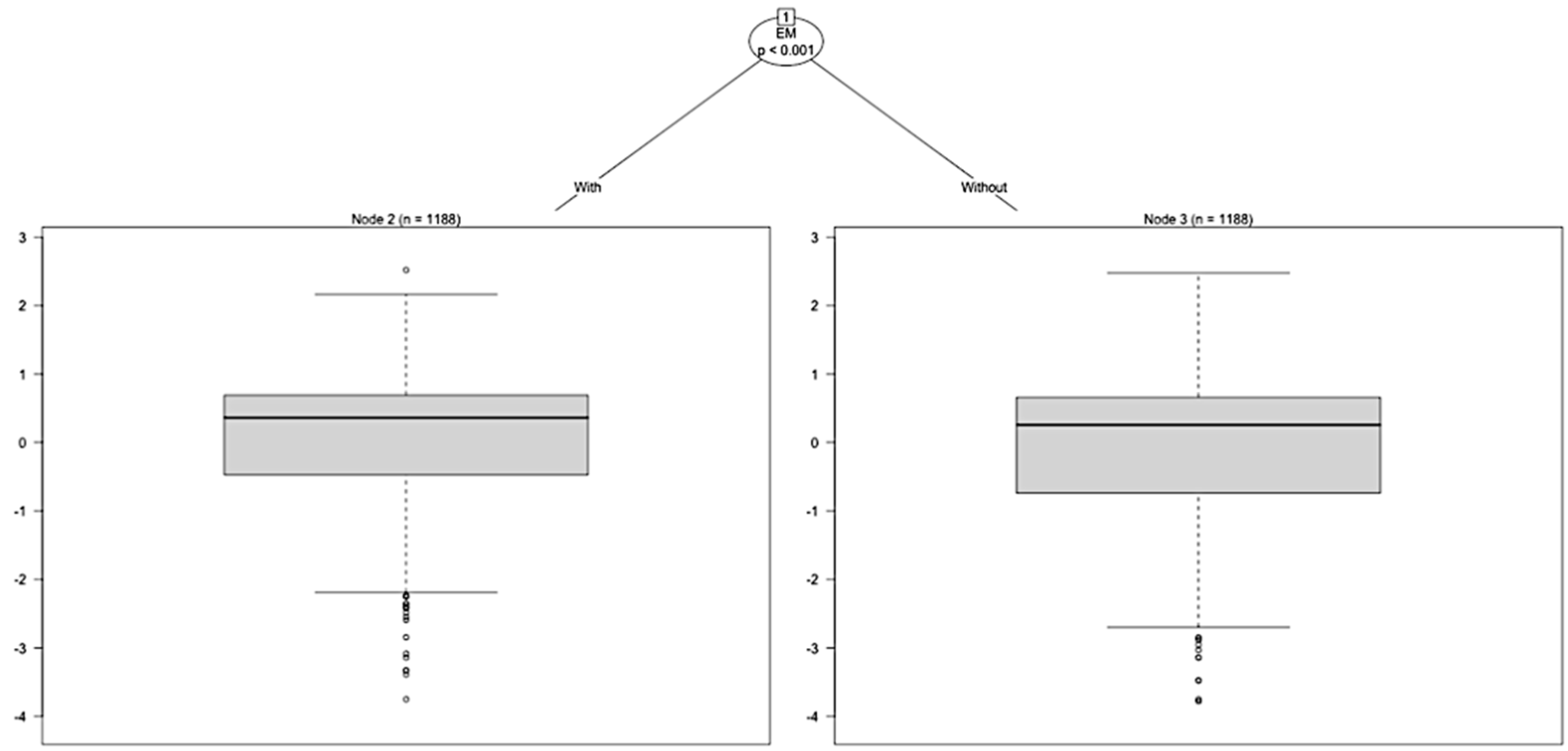

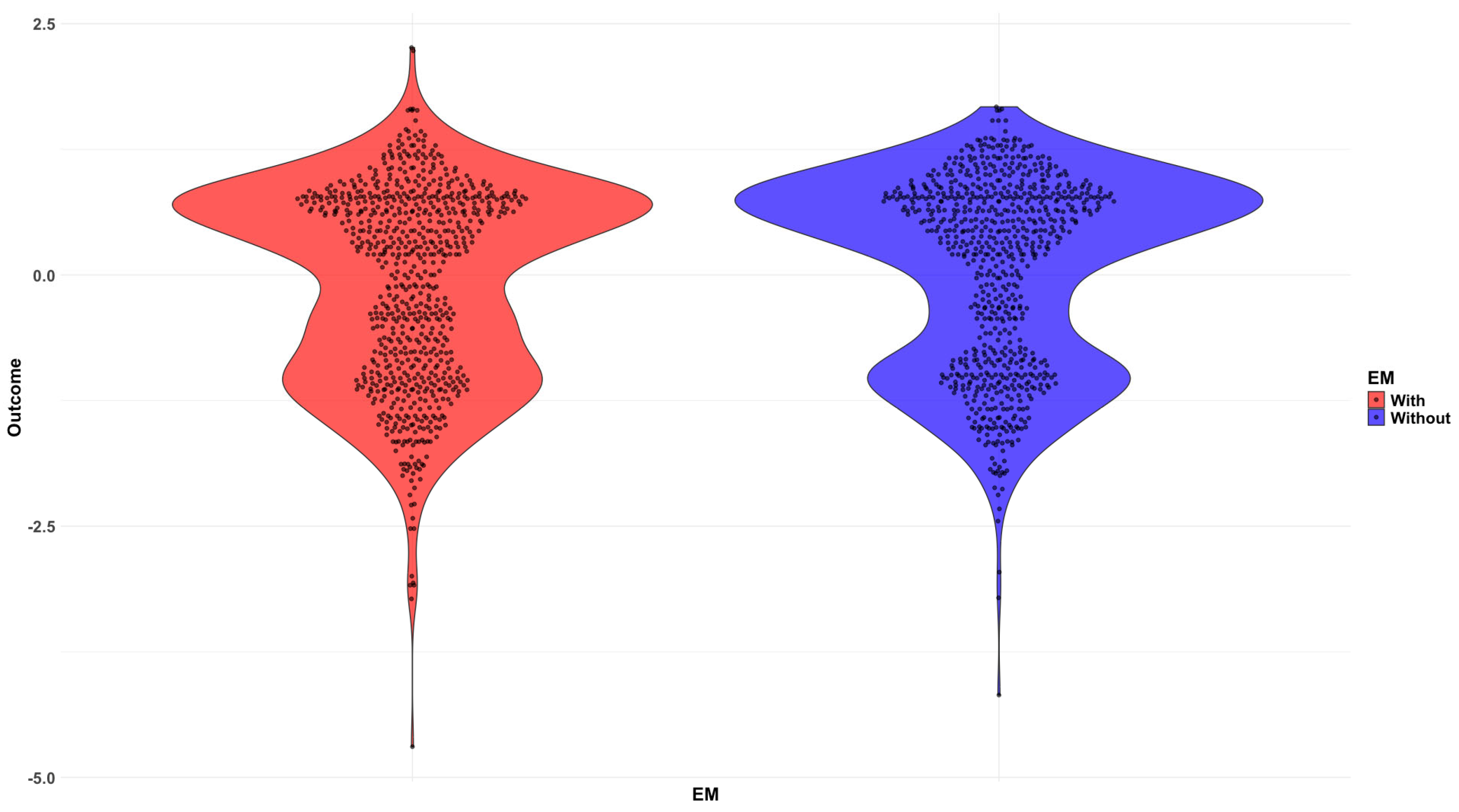

3.1.2. Exhaustivity Marker: Italian

3.1.3. Interim Discussion: Italian

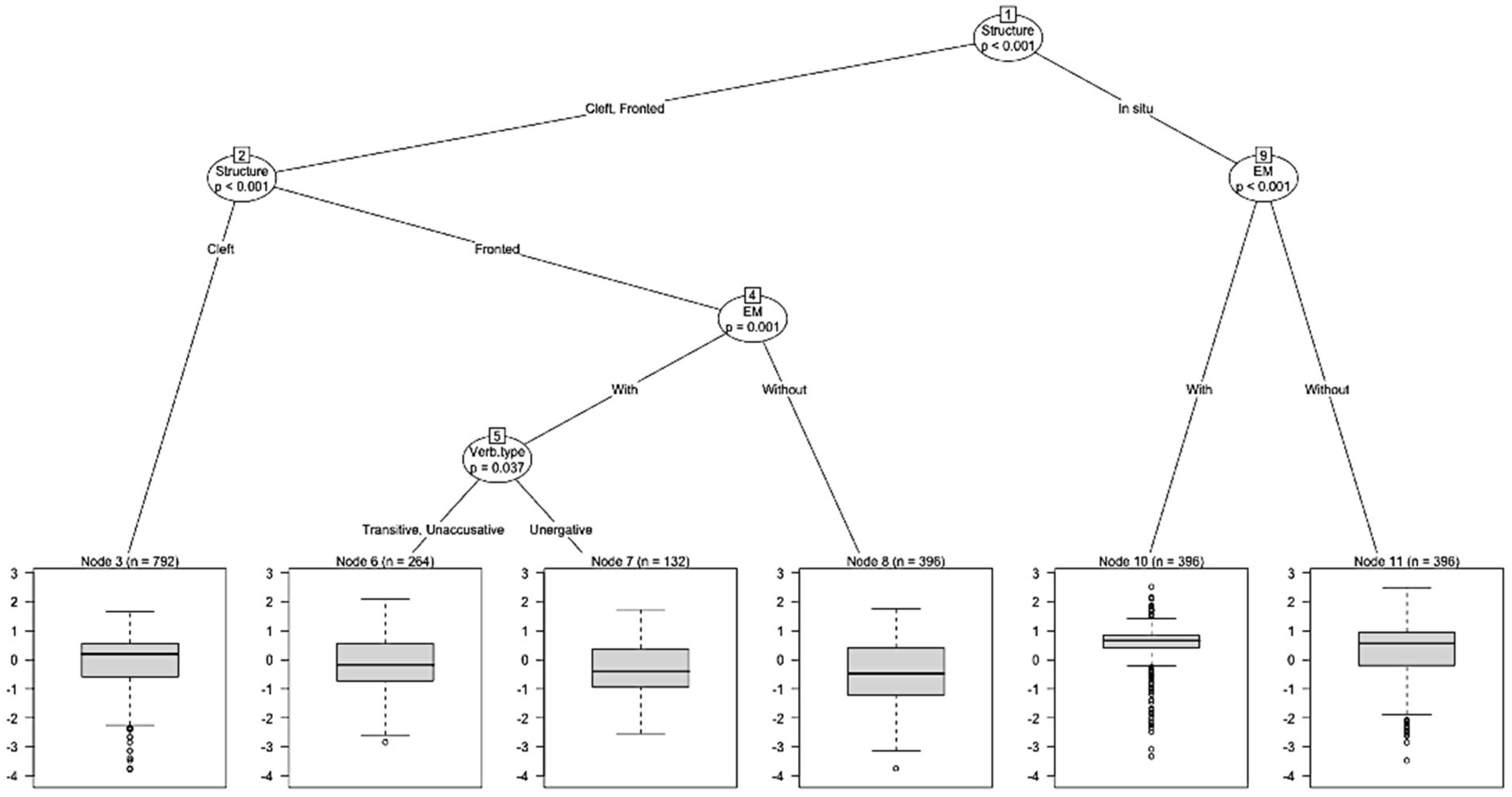

3.2. Data Analysis: French

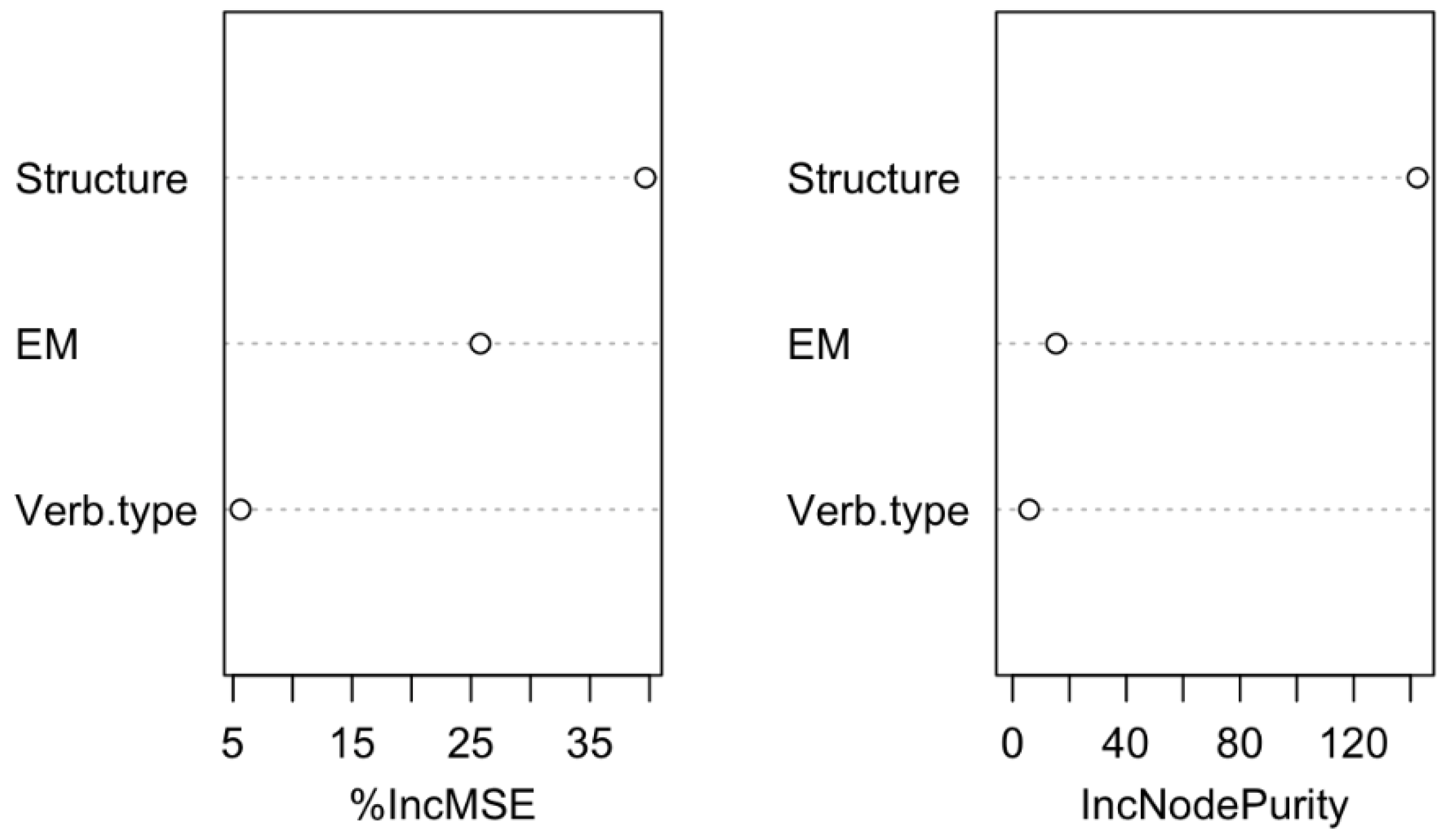

3.2.1. Verb Type and Structure: French

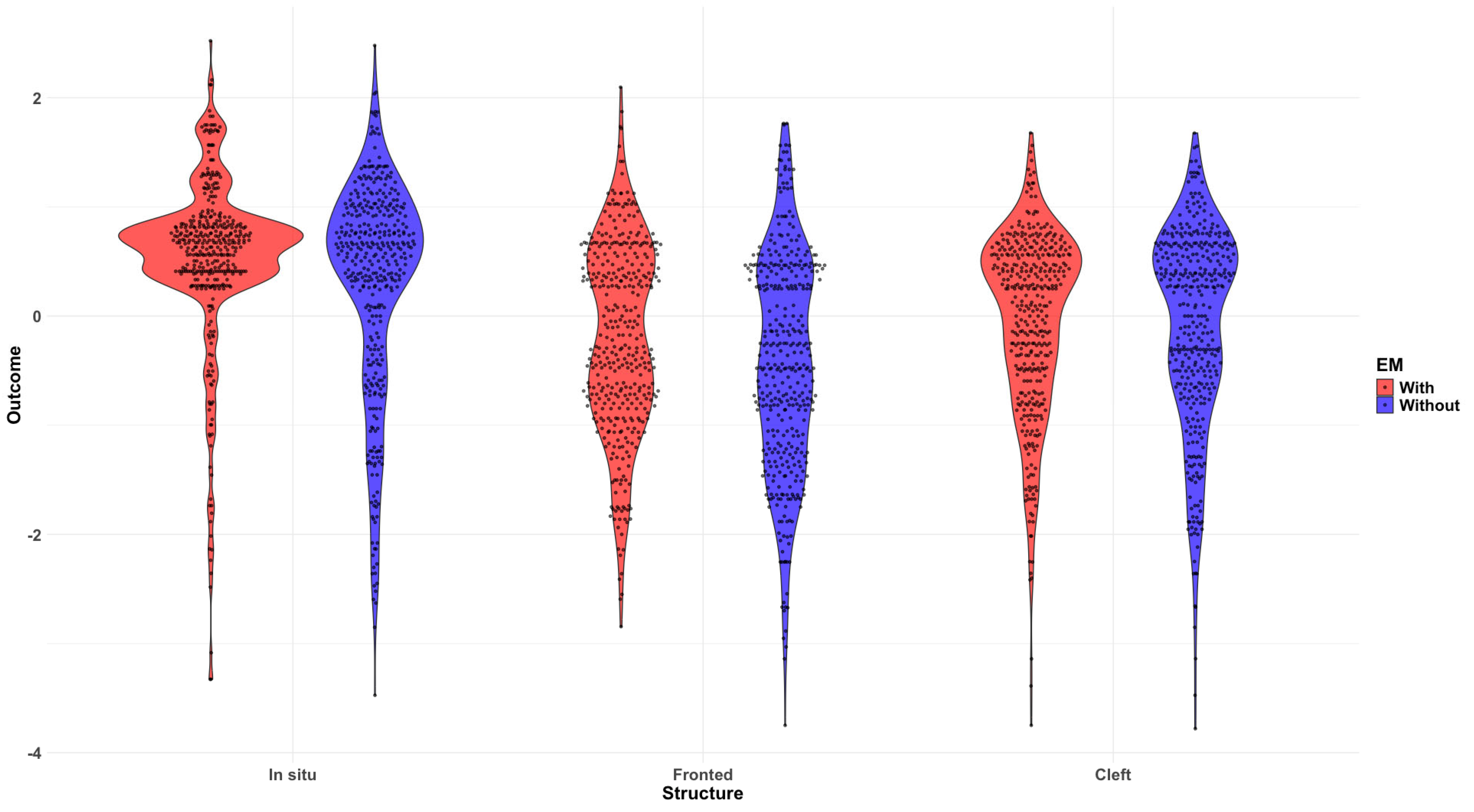

3.2.2. Exhaustivity Marker: French

3.2.3. Interim Discussion: French

| (18) | C’ | est | le | stylo | qu’ | il | a | pris | |

| it | COP | the | pen | that | he | AUX.3SG.PT | take.PP | ||

| ‘It is the pen that he took (and nothing else)’ | |||||||||

| (19) | [GP [TP c’i est [SC ti tk]] [FocP [DP le stilo]k [TopP [DP OPk qu’il a pris ek ]i tTP]]] | ||||||||

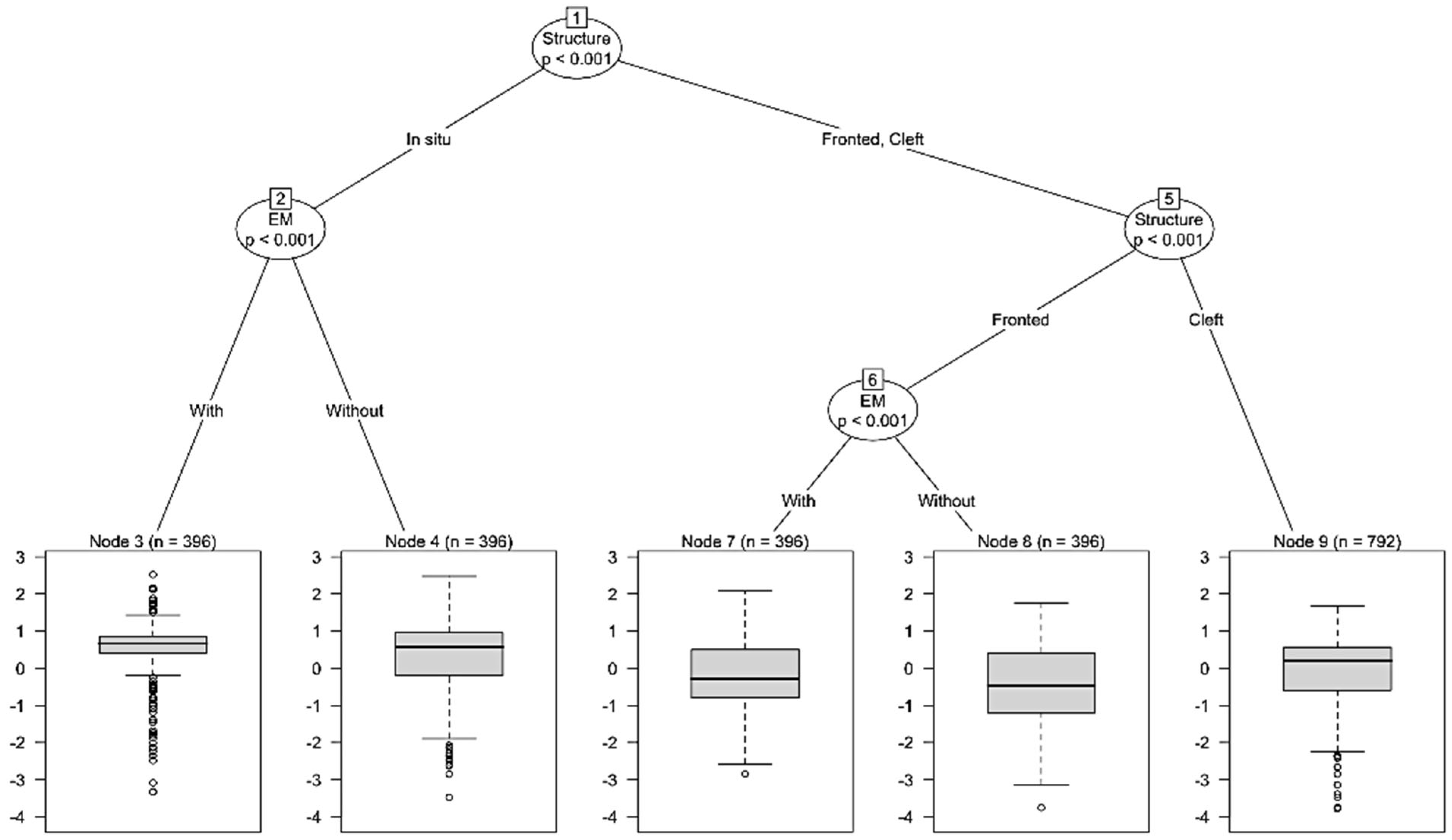

3.3. Comparison Between Italian and French

4. Conclusions

- (i)

- Can different degrees of “rigid syntax” influence the acceptance of different Focus strategies in the two languages under analysis, particularly in relation to the complex Focus type [+corrective, +exhaustive]?

- (ii)

- Can the presence or absence of an explicit EM affect the acceptability of the relevant sentences in the two languages under investigation?

- (iii)

- Can different argument structures in the vP affect the movement of the focused constituent?

- (a)

- Italian speakers prefer in situ Focus with an explicit EM;

- (b)

- French speakers rate in situ and cleft structures (CC) without an EM as equally acceptable.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| TRANS01 Context: A: Che cosa ha preso Marco dall’astuccio? ‘What did Marco take from the pencil case?’ B: La penna, la matita e la gomma. ‘The pen, the pencil and the eraser’ In situ a. C: Guarda bene! Ha preso la penna! ‘Look better! (He) took the pen!’ b. C: Guarda bene! Ha preso solo la penna! ‘Look better! (He) only took the pen! FF a. C: Guarda bene! La penna ha preso! Lit: ‘Look better! The pen (he) took!’ b. C: Guarda bene! Solo la penna ha preso! Lit: ‘Look better! Only the pen (he) took!’ CC a. C: Guarda bene! È la penna che ha preso! ‘Look better! It is the pen that (he) took!’ b. C: Guarda bene! È solo la penna che ha preso! ‘Look better! It is only the pen that (he) took!’ | Figure TRANS01 |

| TRANS02 Context: A: Quali giochi ha fotografato Tania? ‘Which toy(s) did Tania photograph?’ B: Il peluche, la bambola e il sonaglio. ‘The soft toy, the doll and the rattle’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. Ha fotografato la bambola. ‘Look at the picture. (She) photographed the doll’ a. C: Guarda la foto. Ha fotografato solo la bambola. ‘Look at the picture. (She) only photographed the doll’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. La bambola ha fotografato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The doll (she) photographed’ a. C: Guarda la foto. Solo la bambola ha fotografato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the doll (she) photograph’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È la bambola che ha fotografato. ‘Look at the picture. It is the doll that (he) photographed!’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo la bambola ha fotografato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the doll that (he) photographed!’ | Figure TRANS02 |

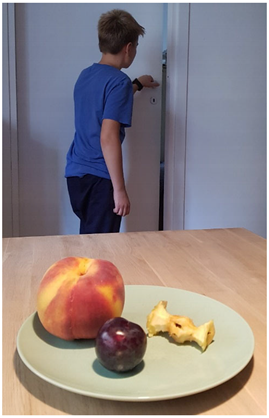

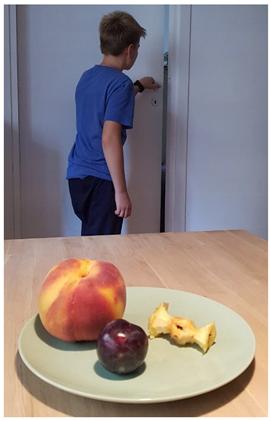

| TRANS03 Context: A: Quale frutta ha mangiato Leo per merenda? ‘Which fruit(s) did Leo eat as a snack?’ B: La pesca, la mela e la pera. ‘The peach, the apple and the pear’ In situ b. C: Guarda la foto. Ha mangiato la mela. ‘Look at the picture. (He) ate the apple’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Ha mangiato solo la mela. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only ate the apple’ FF b. C: Guarda la foto. La mela ha mangiato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The apple (he) ate’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo la mela ha mangiato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the apple (he) ate’ CC b. C: Guarda la foto. È la mela che ha mangiato. ‘Look at the picture. It is the apple that (he) ate’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È solo la mela che ha mangiato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the apple that (he) ate’ | Figure TRANS03 |

| TRANS04 Context: A: Quali panni ha stirato Mara? ‘Which clothes did Mara iron?’ B: La maglietta, la camicia e la gonna. ‘The shirt, the blouse and the skirt’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. Ha stirato la camicia. ‘Look at the picture. (She) ironed the blouse’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Ha stirato solo la camicia. ‘Look at the picture. (She) only ironed the blouse’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. La camicia ha stirato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The blouse (she) ironed’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo la camicia ha stirato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the blouse (she) ironed’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È la camicia che ha stirato. ‘Look at the picture. It is the blouse that (she) ironed! b. C: Guarda la foto. È solo la camicia che ha stirato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the blouse that (she) ironed! | Figure TRANS04 |

| UNERG01 Context: A: Con quali giochi ha giocato Emilio? ‘What toys did Emilio play with?’ B: Con le costruzioni, con la palla e con le macchinine. ‘With (the) building blocks, with the ball and with (the) cars’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto! Ha giocato con la palla. ‘Look at the picture! (He) played with the ball’ b. C: Guarda la foto! Ha giocato solo con la palla. ‘Look at the picture! (He) only played with the ball’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto! Con la palla ha giocato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture! With the ball doll (he) played’ b. C: Guarda la foto! Solo con la palla ha giocato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture! Only with the ball doll (he) played’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto! È con la palla che ha giocato. ‘Look at the picture! It is with the ball that (he) played’ b. C: Guarda la foto! È solo con la palla che ha giocato. ‘Look at the picture! It is only with the ball that (he) played’ | Figure UNERG01 |

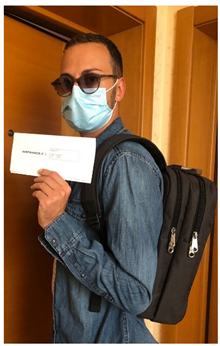

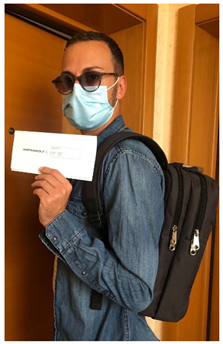

| UNERG02 Context: A: Con quali compagnie ha volato Marco? ‘Which (flying) companies did Marco fly with?’ B: Con Ryanair, con Alitalia e con AirFrance. With Ryanair, (with) Alitalia and (with) AirFrance. In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. Ha volato con Alitalia. ‘Look at the picture. (He) flew with Alitalia’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Ha volato solo con Alitalia. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only flew with Alitalia’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. Con Alitalia ha volato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. With Alitalia (he) flew’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo con Alitalia ha volato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only with Alitalia (he) flew’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È con Alitalia che ha volato. Look at the picture. It is with Alitalia that (he) flew (with)’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È solo con Alitalia che ha volato. Look at the picture. It is only with Alitalia that (he) flew (with)’ | Figure UNERG02 |

| UNERG03 Context: A: A quali oggetti ha sparato Marco? ‘What objects did Marco shoot at?’ B: Alla lattina, alla bottiglia e alla caraffa. ‘The can, the bottle and the jug’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. ha sparato alla bottiglia. ‘Look at the picture. (He) shot at the bottle’ b. C: Guarda la foto. ha sparato solo alla bottiglia. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only shot at the bottle’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. alla bottiglia ha sparato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The bottle (he) shot at’ b. C: Guarda la foto. solo alla bottiglia ha sparato Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the bottle (he) shot at’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. è alla bottiglia che ha sparato. ‘Look at the picture. It is the bottle that (he) shot at’ b. C: Guarda la foto. è solo alla bottiglia che ha sparato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the bottle that (he) shot at’ | Figure UNERG03 |

| UNERG04 Context: A: A quale dolce ha pensato Marco? ‘What sweet dessert did Marco think about?’ B: Al gelato, alla torta e alla mousse al cioccolato. ‘(about) Ice cream, cake and chocolate mousse’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. Ha pensato alla torta. ‘Look at the picture. (He) thought about the cake’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Ha pensato solo alla torta. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only thought about the cake’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. Alla torta ha pensato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The cake (he) thought about’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo alla torta ha pensato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the cake (he) thought about’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È alla torta che ha pensato. ‘Look at the picture. It is the cake that (he) thought about’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È solo alla torta che ha pensato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the cake that (he) thought about’ | Figure UNERG04 |

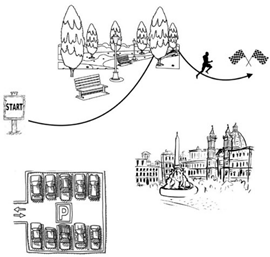

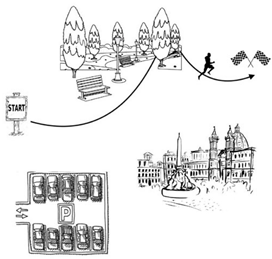

| INACC01 Context: A: Dove è andato Marco? ‘Where did Marco go?’ B: A Roma, a Venezia e a Napoli. ‘To Rome, (to) Venice and (to) Naples. In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. È andato a Venezia. ‘Look at the picture. (He) went to Venice’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È andato solo a Venezia. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only went to Venice’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. A Venezia è andato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. To Venice (he) went (to)’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo a Venezia è andato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only to Venice (he) went (to)’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È a Venezia che è andato. ‘Look at the picture. It is to Venice that (he) went (to)’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È solo a Venezia che è andato. Look at the picture. It is only to Venice that (he) went (to)’ | Figure INACC01 |

| INACC02 Context: A: Per dove è passato Marco? ‘Where did Marco pass through?’ B: Per la piazza, per il parco e per il parcheggio. ‘Through the square, (through) the park and (through) the city parking’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. È passato per il parco. ‘Look at the picture! (He) passed through the park’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È passato solo per il parco. ‘Look at the picture! (He) only passed through the park’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. Per il parco è passato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Through the park (he) passed (through)’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo per il parco è passato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only through the park (he) passed (through)’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È per il parco che è passato. ‘Look at the picture. It is through the park that he passed (through)’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È solo per il parco che è passato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only through the park that he passed (through)’ | Figure INACC02 |

| INACC03 Context: A: In che cosa è inciampato Marco? ‘What did Marco stumble in?’ B: Nella buca, nel sasso e nella radice. ‘In the hole, in the stone and in the root’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto. È inciampato nel sasso. ‘Look at the picture. (He) stumbled in the stone’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È inciampato solo nel sasso. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only stumbled in the stone’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto. Nel sasso è inciampato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. In the stone (he) stumbled (in)’ b. C: Guarda la foto. Solo nel sasso è inciampato. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only in the stone (he) stumbled (in)’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto. È nel sasso che è inciampato. ‘Look at the picture. It is in the stone that (he) stumbled (in)’ b. C: Guarda la foto. È solo nel sasso che è inciampato. ‘Look at the picture. It is only in the stone that (he) stumbled (in)’ | Figure INACC03 |

| INACC 04 Context: A: Su quale mobile è salito Marco? ‘Which pieces of furniture did Carlo climb on? B: Sul divano, sulla sedia e sul tavolo. ‘On the sofa, (on) the chair and (on) the table’ In situ a. C: Guarda la foto! È salito sulla sedia. ‘Look at the picture! (He) climbed on the chair’ b. C: Guarda la foto! È salito solo sulla sedia. ‘Look at the picture! (He) only climbed on the chair’ FF a. C: Guarda la foto! Sulla sedia è salito. Lit: ‘‘Look at the picture! On the chair (he) climbed’ b. C: Guarda la foto! Solo sulla sedia è salito. Lit: ‘‘Look at the picture! Only on the chair (he) climbed’ CC a. C: Guarda la foto! È sulla sedia che è salito. ‘Look at the picture! It is on the chair that (he) climbed’ b. C: Guarda la foto! È solo sulla sedia che è salito. ‘Look at the picture! It is only on the chair that (he) climbed’ | Figure INACC04 |

Appendix B

| TRANS03 Context: A: Quel fruit Leo a—t—il mangé pour l’heure du goûter? ‘Which fruit(s) did Leo eat as a snack?’ B: La pêche, la pomme et la poire. ‘The peach, the apple and the pear’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il a mangé la pomme. ‘Look at the picture. (He) ate the apple’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’a mangé que la pomme ‘Look at the picture. (He) only ate the apple’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! La pomme il a mangée. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The apple (he) ate’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement la pomme il a mangée. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the apple (he) ate’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est la pomme qu’il a mangée. ‘Look at the picture. It is the apple that (he) ate’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement la pomme qu’il a mangée. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the apple that (he) ate’ | Figure TRANS03 |

| TRANS04 Context: A: Quels vêtements Mara a- t- il repassés? ‘Which clothes did Mara iron?’ B: Le t-shirt, la chemise et la jupe. ‘The shirt, the blouse and the skirt’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Elle a repassé la chemise. ‘Look at the picture. (She) ironed the blouse’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Elle n’a repassé que la chemise. ‘Look at the picture. (She) only ironed the blouse’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! La chemise elle a repassée. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The blouse (she) ironed’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement la chemise elle a repassée. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the blouse (she) ironed’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est la chemise qu’elle a repassée. ‘Look at the picture. It is the blouse that (she) ironed! b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement la chemise qu’elle a repassée. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the blouse that (she) ironed! | Figure TRANS04 |

| UNERG01 Context: A: Avec quels jeux Emil a- t- il joué? ‘What toys did Emilio play with?’ B: Avec les constructions, le ballon et les petites voitures. ‘With (the) building blocks, with the ball and with (the) cars’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il a joué avec le ballon. ‘Look at the picture! (He) played with the ball’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’a joué qu’avec le ballon. ‘Look at the picture! (He) only played with the ball’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! Avec le ballon il a joué. Lit: ‘Look at the picture! With the ball doll (he) played’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement avec le ballon il a joué. Lit: ‘Look at the picture! Only with the ball doll (he) played’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est avec le ballon qu’il a joué. ‘Look at the picture! It is with the ball that (he) played’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement avec le ballon qu’il a joué. ‘Look at the picture! It is only with the ball that (he) played’ | Figure UNERG01 |

| UNERG02 Context: A: Avec quelles compagnies aériennes Marc a- t- il volé? ‘Which (flying) companies did Marco fly with?’ B: Avec Ryanair, Alitalia et Air-France. With Ryanair, (with) Air France and (with) Alitalia. In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il a volé avec Air-France. ‘Look at the picture. (He) flew with Air France’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’a volé qu’avec Air-France. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only flew with Air France’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! Avec Air-France il a volé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. With Air France (he) flew’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement avec Air-France il a volé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only with Air France (he) flew’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est avec Air-France qu’il a volé. Look at the picture. It is with Air France that (he) flew (with)’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement avec Air-France qu’il a volé. Look at the picture. It is only with Air France that (he) flew (with)’ | Figure UNERG02 |

| UNERG03 Context: A: Sur quels objets Marc a—t—tiré? ‘Which objects did Marco shoot at?’ B: Sur la canette, la bouteille et la carafe. ‘The can, the bottle and the jug’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il a tiré sur la bouteille. ‘Look at the picture. (He) shot at the bottle’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’a tiré que sur la bouteille. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only shot at the bottle’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! Sur la bouteille il a tiré. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The bottle (he) shot at’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement sur la bouteille il a tiré. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the bottle (he) shot at’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est sur la bouteille qu’il a tiré. ‘Look at the picture. It is the bottle that (he) shot at’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement sur la bouteille qu’il a tiré. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the bottle that (he) shot at’ | Figure UNERG03 |

| UNERG04 Context: A: À quel dessert Marc a- t—il pensé? ‘What sweet dessert did Marco think about?’ B: À la glace, au gâteau et à la mousse au chocolat. ‘(about) Ice cream, cake and chocolate mousse’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il a pensé au gâteau. ‘Look at the picture. (He) thought about the cake’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’a pensé qu’au gâteau. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only thought about the cake’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! Au gâteau il a pensé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. The cake (he) thought about’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement au gâteau il a pensé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only the cake (he) thought about’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est au gâteau qu’il a pensé. ‘Look at the picture. It is the cake that (he) thought about’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement au gâteau qu’il a pensé. ‘Look at the picture. It is only the cake that (he) thought about’ | Figure UNERG04 |

| UNACC01 Context: A: Où Marc est-il allé? ‘Where did Marco go?’ B: À Rome, à Venise et à Naples. ‘To Rome, (to) Venice and (to) Naples. In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il est allé à Venise. ‘Look at the picture. (He) went to Venice’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’est allé qu’à Venise. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only went to Venice’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! À Venise il est allé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. To Venice (he) went (to)’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement à Venise il est allé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only to Venice (he) went (to)’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est à Venise qu’il est allé. ‘Look at the picture. It is to Venice that (he) went (to)’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement à Venise qu’il est allé. Look at the picture. It is only to Venice that (he) went (to)’ | Figure UNACC01 |

| UNACC02 Context: A: Par où Marc est—il passé? ‘Where did Marco pass through?’ B: Par la place, le parc et le parking. Through the square, (through) the park and (through) the city parking’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il est passé par le parc. ‘Look at the picture! (He) passed through the park’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’est passé que par le parc. ‘Look at the picture! (He) only passed through the park’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! Par le parc il est passé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Through the park (he) passed (through)’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement par le parc il est passé. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only through the park (he) passed (through)’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est par le parc qu’il est passé. ‘Look at the picture. It is through the park that he passed (through)’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement par le parc qu’il est passé. ‘Look at the picture. It is only through the park that he passed (through)’ | Figure UNACC02 |

| UNACC03 Context: A: Sur quoi Marc a—t—il trébuché? ‘What did Marco stumble in?’ B: Sur un trou, une pierre et une racine. ‘In the hole, in the stone and in the root’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il a trébuché sur une pierre. ‘Look at the picture. (He) stumbled in the stone’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’a trébuché que sur une pierre. ‘Look at the picture. (He) only stumbled in the stone’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! Sur une pierre il a trébuché. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. In the stone (he) stumbled (in)’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement sur une pierre il a trébuché. Lit: ‘Look at the picture. Only in the stone (he) stumbled (in) CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est sur une pierre qu’il a trébuché. ‘Look at the picture. It is in the stone that (he) stumbled (in)’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement sur une pierre qu’il a trébuché. ‘Look at the picture. It is only in the stone that (he) stumbled (in)’ | Figure UNACC03 |

| UNACC04 Context: A: Sur quel meuble Marc est- il monté? ‘Which pieces of furniture did Carlo climb on? B: Sur le canapé, la chaise et la table. ‘On the sofa, (on) the chair and (on) the table’ In situ a. C: Regarde la photo! Il est monté sur la chaise. ‘Look at the picture! (He) climbed on the chair’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Il n’est monté que sur la chaise. ‘Look at the picture! (He) only climbed on the chair’ FF a. C: Regarde la photo! Sur la chaise il est monté. Lit: ‘‘Look at the picture! On the chair (he) climbed’ b. C: Regarde la photo! Seulement sur la chaise il est monté. Lit: ‘‘Look at the picture! Only on the chair (he) climbed’ CC a. C: Regarde la photo! C’est sur la chaise qu’il est monté. ‘Look at the picture! It is on the chair that (he) climbed’ b. C: Regarde la photo! C’est seulement sur la chaise qu’il est monté. ‘Look at the picture! It is only on the chair that (he) climbed’ | Figure UNACC04 |

| 1 | In this and the following examples, the focused constituents are signaled in bold. |

| 2 | Example (2a) is adapted from Greif and Skopeteas (2021, p. 4), and examples (2b), (2b′), and (2b″) are adapted from Authier and Haegeman (2019, p. 41). |

| 3 | As is common use, the symbol “#” conventionally indicates (pragmatically) unacceptable sentences. |

| 4 | Examples (4a–b) and (5a–b) are extracted and adapted from Brunetti (2004, p. 70). |

| 5 | From a syntactic viewpoint, Horvath (2007, 2013) argues for the existence of a separate Exhaustive Identification Operator (henceforth, EI-Op) located in a dedicated functional Phrase (i.e., EiP), which interacts with Focus only indirectly. According to Horvath (2007), Focus is not encoded as a formal syntactic feature; hence, a FocP projection cannot serve as an attractor for Focus movement. The author argues that Focus itself does not trigger movement. Instead, movement is driven by the presence of the EI-Op, at least in Hungarian. Thus, when a focused constituent is associated with an EI-Op, it receives an Exhaustive interpretation. |

| 6 | According to Frascarelli and Ramaglia (2014), the relative clause can be considered as a Topic associated with [+background, +given] features and, as such, it is assumed to be in the lowest TopP below FocP. For further discussion on given Topics see also Frascarelli and Hinterhölzl (2007). |

| 7 | External Merge refers to the operation through which two distinct rooted structures are joined into one (i.e., the building of argument structures; Chomsky, 2001). |

| 8 | Internal arguments generated in low vP positions, such as the subjects of unaccusative verbs, may give rise to intervention effects, impacting the accessibility of higher movement targets (Rizzi, 1990, 2001, 2004, 2018; Chomsky, 1995, 2000, 2001; Belletti, 2001). Intervention effects are also discussed in Frascarelli et al. (2022) for Italian, where Focus Fronting (FF) of objects is shown to be favored when the object occupies Spec,VP, as in psych-verbs, where the experiencer object is merged higher than the theme subject (Compl,VP). Moreover, Frascarelli et al. show that FF is less likely with transitive verbs than with unergative and unaccusative verbs: although in all these cases, the object is merged below the subject, objects in transitive occupy a higher structural position (Spec,VP), while in unergatives and unaccusatives they are merged in a lower complement position (Comp,VP). Conversely, Stortini (2024) shows that in Italian, Spanish, and English, the FF of the subject is disfavored when the subject is structurally lower than the object, as in psych-verbs, where the theme subject is merged below the experiencer object. |

| 9 | In this study, we adopt the perspective that adjunct indirect objects (IOs) in unergative and unaccusative verbs can be realized as arguments, as suggested by Manning et al. (1999) and Bouma et al. (2001). This analysis is supported by evidence from scope ambiguity, case marking, word order, and cliticization. In line with this approach, we assume that the IOs associated with these verbs are, at least syntactically, comparable to arguments merged in Compl,VP. |

| 10 | The EQF (European Qualification Framework) is an 8-level learning outcomes-based framework developed by the EU to make (inter)national qualifications more comparable. The EQF provides descriptors for the three cycles of higher education. Descriptors for the first cycle correspond to EQF levels 3–4. Descriptors for the second cycle correspond to EQF levels 5–6. Descriptors for the third cycle correspond to EQF levels 7–8 (Council of the European Union, 2017). |

| 11 | See Appendix A and Appendix B for all the conditions in the Italian and French versions of the test. |

| 12 | No statistical differences were attested when comparing the four verbs used for each condition. |

| 13 | The test link was shared on social networks to collect as much data as possible. To prevent the same person from answering multiple surveys, we specified that only individuals whose surname started with a specific letter should complete the test, changing the letter for each list link. |

| 14 | Fillers followed a format similar to the experimental questions, including an image, Speaker A asking a wh-question, and Speaker B providing a correct answer. Informants were asked to judge the acceptability of Speaker B’s response. |

| 15 | Fillers were not included in the dataset that was normalized to z-scores. |

| 16 | As already mentioned, our test is the same as that of Ylinärä et al. (2023) for Italian but with a larger dataset. However, it should be noted that Ylinärä et al. (2023) used a repeated-measures ANOVA, a parametric test, whereas we employed a non-parametric test. Therefore, we re-conducted the analysis on the Italian dataset also to check for potential discrepancies (false positives or false negatives) that may have arisen from the use of an unsuitable statistical method. |

| 17 | In all METs, the number above the circle showing the p-value represents the node number and is not relevant to the analysis. |

| 18 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: In situ = 5.02; FF = 4.13; CC = 4.52. |

| 19 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: without EM = 4.48; with EM: 4.75. |

| 20 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: Without EM/In situ = 5.04; Without EM/FF = 3.97; Without EM/CC = 4.44; With EM/In situ = 5.36; With EM/FF = 4.29; Without EM/CC = 4.60. |

| 21 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: Transitive = 3.91; Unergative = 4.13; Unaccusative = 4.47. |

| 22 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: Transitive/In situ = 4.50; Transitive/FF = 2.84; Transitive/CC = 4.34; Unergative/In situ = 4.57; Unergative/FF = 3.04; Unergative/CC = 4.77; Unaccusative/In situ = 5.04; Unaccusative/FF = 3.47; Unaccusative/CC = 4.86. |

| 23 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: In situ = 4.7; FF = 3.12; CC 4.66. |

| 24 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: Without EM = 4.26; With EM = 4.08. |

| 25 | Raw scores (before normalization) are the following: Without EM/In situ = 4.97; Without EM/FF = 3.03; Without EM/CC = 4.98; With EM/In situ = 4.49; With EM/FF = 3.22; Without EM/CC = 4.38. |

| 26 | Considering that in situ and CC are grouped together in the relevant MET, no statistical differences are observed between the two EMs (n’a … que and seulement), which are used respectively for the two structures. |

| 27 | Verb type was not included, as it is not predictive for Italian. Moreover, the (general) model excluding verb type has a lower RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) than the one including it, indicating more accurate predictions. Since RMSE measures the average difference between predicted and actual values, a lower RMSE reflects better model performance. |

References

- Aboh, E. O., Hartmann, K., & Zimmerman, M. (Eds.). (2007). Focus strategies in African languages. The interaction of focus and grammar in Niger-Congo and Afro-Asiatic. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Alboiu, G. (2004). Optionality at the interface: Triggering focus in Romanian. In H. van Riemsdijk, & A. Breitbath (Eds.), Triggers (pp. 49–75). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Authier, J. M., & Haegeman, L. (2019). The syntax of mirative focus fronting: Evidence from French. In Studies in natural language and linguistic theory (pp. 39–63). Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, D., & Clark, B. (2003). Always and only: Why not all focus sensitive operators are alike. Natural Language Semantics, 11(4), 323–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, A. (2001). Inversion as focalization. In A. Hulk, & J. Y. Pollock (Eds.), Subject inversion in romance and the theory of universal grammar (pp. 60–90). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A. (2005). Answering with a “cleft”: The role of the null subject parameter and the VP periphery. In L. Brugè, G. Giusti, N. Munaro, W. Schweikert, & G. Turano (Eds.), Proceedings of the XXX incontro di grammatica generativa (pp. 63–82). Cafoscarina. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A. (2008). The CP of clefts. RGG. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa, 33, 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A. (2012). Revisiting the CP of clefts. In Discourse and grammar. From sentence types to lexical categories (pp. 91–114). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A. (2015). The focus map of clefts: Extraposition and predication. In U. Shlonsky (Ed.), Beyond functional sequence: The cartography of syntactic structures (Vol. 10, pp. 42–59). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A., & Rizzi, L. (2017). On the syntax and pragmatics of some clause-peripheral positions. In J. Blochowiak, C. Grisot, S. Durrleman, & C. Laenzlinger (Eds.), Formal models in the study of language. Applications in interdisciplinary contexts (pp. 33–48). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, V. (2013). On ‘focus movement’ in Italian. In V. Camacho-Taboada, Á. L. Jiménez-Fernández, J. Martín-González, & M. Reyes-Tejedor (Eds.), Information Structure and Agreement (pp. 193–216). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, V., & Bocci, G. (2012). Should I stay or should I go? Optional focus movement in Italian. Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, V., Bocci, G., & Cruschina, S. (2015). Focus fronting and its implicatures. In E. O. Aboh, J. C. Schaeffer, & P. Sleeman (Eds.), Romance languages and linguistic theory 2013. Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’ Amsterdam 2013 (pp. 1–20). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, V., Bocci, G., & Cruschina, S. (2016). Focus fronting, unexpectedness, and evaluative implicatures. Semantics and Pragmatics, 9(3), 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, G., & Avesani, C. (2015). Can the metrical structure of Italian motivate focus fronting? In U. Shlonsky (Ed.), Beyond functional sequence: The cartography of syntactic structures (Vol. 10, pp. 23–41). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, G., Malouf, R., & Sag, I. A. (2001). Satisfying constraints on extraction and adjunction. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 19, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, M., & Szendröi, K. (2011). A kimerítő felsorolás értemezésű fókusz válasz. [Exhaustive focus is an answer]. In H. Bartos (Ed.), Új irányok és eredmények a mondattani kutatásban—Kiefer Ferenc 80. szuletesnapja alkalmabol [New directions and results in syntactic research—In honour of Ferenc Kiefer’s 80th birthday] (Vol. 23). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, L. (2004). A unification of focus. Unipress. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, L. (2009). Discourse functions of fronted foci in Italian and Spanish. In A. Dufter, & D. Jacob (Eds.), Focus and background in romance languages (pp. 43–81). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Carella, G. (2019). Discourse categories, conversational dynamics and the root/embedded distinction [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Roma Tre]. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (1995). The minimalist program. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2000). Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In R. Martin, D. Michaels, & J. Uriagereka (Eds.), Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik (pp. 89–155). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2001). Beyond explanatory adequacy. MIT Occasional Papers in Linguistics 20. MIT, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, MITWPL. [Google Scholar]

- Citko, B. (2011). Small clauses. Language and Linguistics Compass, 5, 748–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clech-Darbon, A., Rebuschi, G., & Rialland, A. (1999). Are There Cleft Sentences in French? In G. Rebuschi, & L. Tuller (Eds.), The grammar of focus (pp. 83–118). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. (2017). Council recommendation of 22 May 2017 on the European qualifications framework for lifelong learning and repealing the recommendations of the European parliament and of the council of 23 April 2008 on the establishment of the European qualifications framework for lifelong learning. Official Journal, C 189, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cruschina, S. (2011). Focalization and word order in Old Italo-Romance. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 10, 95–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruschina, S. (2012). Discourse-related features and functional projections. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cruschina, S. (2015). Some notes on fronting and clefting. In E. Di Domenico, C. Hamann, & S. Matteini (Eds.), Structures, strategies and beyond. Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti (pp. 181–208). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Cruschina, S. (2021). The greater the contrast, the greater the potential: On the effects of focus in syntax. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 6(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, R. (1988). Studies on copular sentences, clefts and pseudo-clefts. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Dekydtspotter, L. (1993). The Syntax and Semantics of the French Ne Que Construction. In U. Lahiri, & A. Z. Wyner (Eds.), Proceedings from SALT III (pp. 38–58). Cornell University. [Google Scholar]

- Delahunty, G. P. (1982). Topics in the syntax and semantics of English cleft sentences. Indiana Univesity Linguistics Club. [Google Scholar]

- Delahunty, G. P. (1984). The analysis of English cleft sentences. Linguistic Analysis, 13(1), 63–113. [Google Scholar]

- Delin, J., & Oberlander, J. (1995). Syntactic constraints on discourse structure: The case of it-clefts. Linguistics, 33(3), 465–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Dickken, M., Meinunger, A., & Wilder, C. (2000). Pseudoclefts and ellipsis. Studia Linguistica, 54(1), 41–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destruel, E. (2012). The french c’est clefts: An empirical study on its meaning and use. Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics, 9, 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Destruel, E., & De Veaugh-Geiss, J. P. (2018). On the interpretation and processing of exhaustivity: Evidence of variation in English and French clefts. Journal of Pragmatics, 138, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Féry, C. (2001). Focus and phrasing in French. In C. Féry, & W. Sternefeld (Eds.), Audiatur vox sapientiae: A festschrift for arnim von stechow (pp. 153–181). Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Féry, C., & Samek-Lodovici, V. (2006). Focus projection and prosodic prominence in nested foci. Language, 82(1), 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkema, M., Smits, N., Zeileis, A., Hothorn, T., & Kelderman, H. (2018). Detecting treatment-subgroup interactions in clustered data with generalized linear mixed-effects model trees. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 2016–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frascarelli, M. (2000). The syntax-phonology interface in focus and topic constructions in Italian. Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, M. (2010). Narrow focus, clefting and predicate inversion. Lingua, 120(9), 2121–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascarelli, M., Carella, G., & Casentini, M. (2022). Superiority in fronting. A syntax-semantics interface approach to optionality. Quaderni di lavoro ASIt, 24, 179–235. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, M., & Hinterhölzl, R. (2007). Types of topics in German and Italian. In S. Winkler, & K. Schwabe (Eds.), On information structure, meaning and form (pp. 87–116). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, M., & Ramaglia, F. (2013). (Pseudo)clefts at the syntax-prosody-discourse interface. In K. Hartmann, & T. Veenstra (Eds.), The structure of clefts (pp. 97–137). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, M., & Ramaglia, F. (2014). The interpretation of clefting (a)symmetries between Italian and German. In K. Lahousse, & S. Marzo (Eds.), Romance languages and linguistic theory 2012. Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’ Leuven 2012 (pp. 67–91). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, M., & Stortini, T. (2019). Focus constructions, verb types and the SV/VS order in Italian: An acquisitional study from a syntax-prosody perspective. Lingua, 227, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, P. C. (2013). Statistical methods in language and linguistic research. Equinox Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, M., & Skopeteas, S. (2021). Correction by focus: Cleft constructions and the cross-linguistic variation in phonological form. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K., & Zimmermann, M. (2007). In place—Out of place: Focus in Hausa. In K. Schwabe, & S. Winkler (Eds.), On information structure, meaning and form: Generalizatons across languages (pp. 365–403). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, R., & Towell, R. (2015). French grammar and usage (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg, N. (1990). Discourse pragmatics and cleft sentences in English [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota]. [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg, N. (2000). The referential status of clefts. Language, 76, 891–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggie, L. (1988). The syntax of copular constructions [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California]. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, J. (2007). Separating “focus movement” from focus. In S. Karimi, V. Samiian, & W. K. Wilkins (Eds.), Phrasal and clausal architecture: Syntactic derivation and interpretation (pp. 108–145). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, J. (2013). On focus, exhaustivity and Wh-interrogatives: The case of Hungarian. In J. Brandtler, V. Molnar, & C. Platzak (Eds.), Approaches to Hungarian (Vol. 13, pp. 97–132). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, R. (1972). Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, K. É. (1998). Identificational focus versus information focus. Language, 74, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, K. É. (1999). The English cleft construction as a focus phrase. In L. Mereu (Ed.), Boundaries of morphology and syntax (pp. 217–229). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- König, E. (1991). The meaning of focus particles: A comparative perspective (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer, A. (1994). On external arguments. In E. Benedicto, & J. Runner (Eds.), Functional projections (pp. 103–130). GLSA, UMass Amherst. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, M. (2001). For a structured meaning account of questions and answers. In C. Féry, & W. Sternefeld (Eds.), Audiatur vox sapientia: A festschrift for Arnim von Stechow (pp. 287–319). Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, M. (2007). Basic notions of information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica, 55, 243–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, K. (1994). Information structure and sentence form: Topic, focus and the mental representation of discourse elements. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, K. (2001). A framework for the analysis of cleft constructions. Linguistics, 39, 463–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, K. (2004). On the interaction of information structure and formal structure in constructions: The case of French right-detached comme-N. In M. Fried, & J. Ostman (Eds.), Construction grammar in a cross-language perspective (pp. 157–199). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Larrivée, P. (2022). The curious case of the rare focus movement in French. In D. Garassino, & D. Jacob (Eds.), When data challenges theory (pp. 184–202). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. K. (1988). On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry, 19(3), 335–391. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, C. D., Sag, I. A., & Masayo, I. (1999). The lexical integrity of Japanese causatives. In R. D. Levine, & G. M. Green (Eds.), Readings in HPSG (pp. 39–79). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, T. (2011). The Syntax of ne...que Exceptives in French. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 17(1), 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou, N. (2015, October 24–26). Explicit and implicit exhaustivity in focus. 15th Texas Linguistic Society Conference, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto, C., & Pollock, J.-Y. (2004). On the left periphery of some Romance wh-questions. In L. Rizzi (Ed.), The cartography of syntactic structures. vol. 2, The structure of CP and IP (pp. 251–296). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L. (1990). Relativized minimality. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L. (2001). Relativized minimality effects. In M. Baltin, & C. Collins (Eds.), The handbook of contemporary syntactic theory (pp. 89–110). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L. (2004). Locality and the left periphery. In A. Belletti (Ed.), Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures (Vol. 3, pp. 223–251). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L. (2018). Intervention effects in grammar and acquisition. In E. Di Domenico, C. Hamann, & S. Matteini (Eds.), Structures, strategies and beyond: Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti (pp. 103–118). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Rooth, M. (1985). Association with focus [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts]. [Google Scholar]

- Rooth, M. (1992). A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics, 1, 75–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek-Lodovici, V. (2005). Prosody-syntax interaction in the expression of focus. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 23, 687–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek-Lodovici, V. (2006). When right dislocation meets the left-periphery. A unified analysis of Italian non-final focus. Lingua, 116, 836–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek-Lodovici, V. (2015). The interaction of focus, givenness, and prosody. A study of Italian clause structure. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Stechow, A. (1995). Lexical decomposition in syntax. In U. Egli, P. E. Pause, C. Schwarze, A. von Stechow, & G. Wienod (Eds.), Lexical knowledge in the organization of language (pp. 81–95). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Stortini, T. (2024). Information and corrective focus in Italian, Spanish, and English. An experimental comparative study from an interface perspective [Doctoral dissertation, Università Ca’ Foscari]. [Google Scholar]

- Swerts, M., Emiel, K., & Cinzia, A. (2002). Prosodic marking of information status in Dutch and Italian: A comparative analysis. Journal of Phonetics, 30(4), 629–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truckenbrodt, H. (1995). Phonological phrases: Their relation to syntax, focus, and prominence [Ph.D. dissertation, MIT]. [Google Scholar]

- van Leusen, N. (2004). Incompatibility in context: A diagnosis of correction. Journal of Semantics, 21, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylinärä, E., Carella, G., & Frascarelli, M. (2023). Confronting focus strategies in Finnish and in Italian: An experimental study on object focusing. Languages, 8(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubizarreta, M. L. (2001). The Constraint on Preverbal Subjects in Romance Interrogatives: A Minimality Effect. In A. Hulk, & J.-Y. Pollock (Eds.), Subject inversion in romance and the theory of universal grammar (pp. 183–204). Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar]

| Language | Participants | Age | Sex | Education (EQF)10 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Dev. | F | M | Other | Level 3–4 | Level 5–6 | Level 7–8 | Other | |||

| Italian | n. | 132 | 28.3 | 12.3 | 103 | 27 | 2 | 91 | 34 | 4 | 3 |

| % | 78% | 21% | 1% | 69% | 26% | 3% | 2% | ||||

| French | n. | 84 | 37.0 | 16.2 | 51 | 31 | 2 | 15 | 27 | 40 | 2 |

| % | 61% | 37% | 2% | 18% | 32% | 47% | 3% | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casentini, M.; Stortini, T. Corrective and Exhaustive Foci: A Comparison Between Italian and French. Languages 2025, 10, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070157

Casentini M, Stortini T. Corrective and Exhaustive Foci: A Comparison Between Italian and French. Languages. 2025; 10(7):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070157

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasentini, Marco, and Tania Stortini. 2025. "Corrective and Exhaustive Foci: A Comparison Between Italian and French" Languages 10, no. 7: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070157

APA StyleCasentini, M., & Stortini, T. (2025). Corrective and Exhaustive Foci: A Comparison Between Italian and French. Languages, 10(7), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070157