The Formal Address Forms in Heritage Polish in Germany: The Dynamics of Transgenerational Language Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

“The synchronic slant has been so dominant in descriptive linguistics that students of interference have generally overlooked the possibility of studying contact-induced progressive changes in a language against the time dimension. Yet an attractive opportunity for short term diachronic observation is offered by languages freshly brought into contact, as through migration.”

2. Language Contact and Address Systems: Outline of the Problem’s Context

3. Polish Address System in Comparison with German

4. Address Forms in Heritage Polish: Stay of Research, Research Questions and Hypotheses

- (1)

- Intense language contact between the heritage language and the dominant societal language, as well as functional bilingualism in heritage speakers, leads to pragmatic shift, which is prepared by the corresponding language attitudes of the migrant or minority group (cf., for other languages, Borbély, 1995; Clarke & Erskine, 2010; Priestly et al., 2009). Language attitudes are among the most crucial factors in language maintenance vs. language shift in migrant communities (Thomason, 2001b). It can be therefore expected that language attitudes against both address systems emerge among Polish heritage speakers before material language transfer takes place (Hypothesis 1);

- (2)

- Multilingual speakers select from the available contact languages as parts of their individual linguistic repertoire (Ptashnyk, 2010, p. 289). Multilingual variation encompasses therefore both diverse varieties within a single language and two or more typologically distinct languages (Veith, 2002, p. 135; Franceschini, 1998, p. 12). Accordingly, it can be expected that bilingual heritage speakers will incorporate elements from both languages in their address system (potentially influenced by language attitudes but also for other reasons, such as language economy or language attrition) (Hypothesis 2).

5. The Survey: Design and Evaluation

5.1. Study Design: Participants and Methods

5.2. Evaluation of Empirical Data

5.2.1. Sociolinguistic Background of Respondents

5.2.2. Attitudes

5.2.3. Language Use

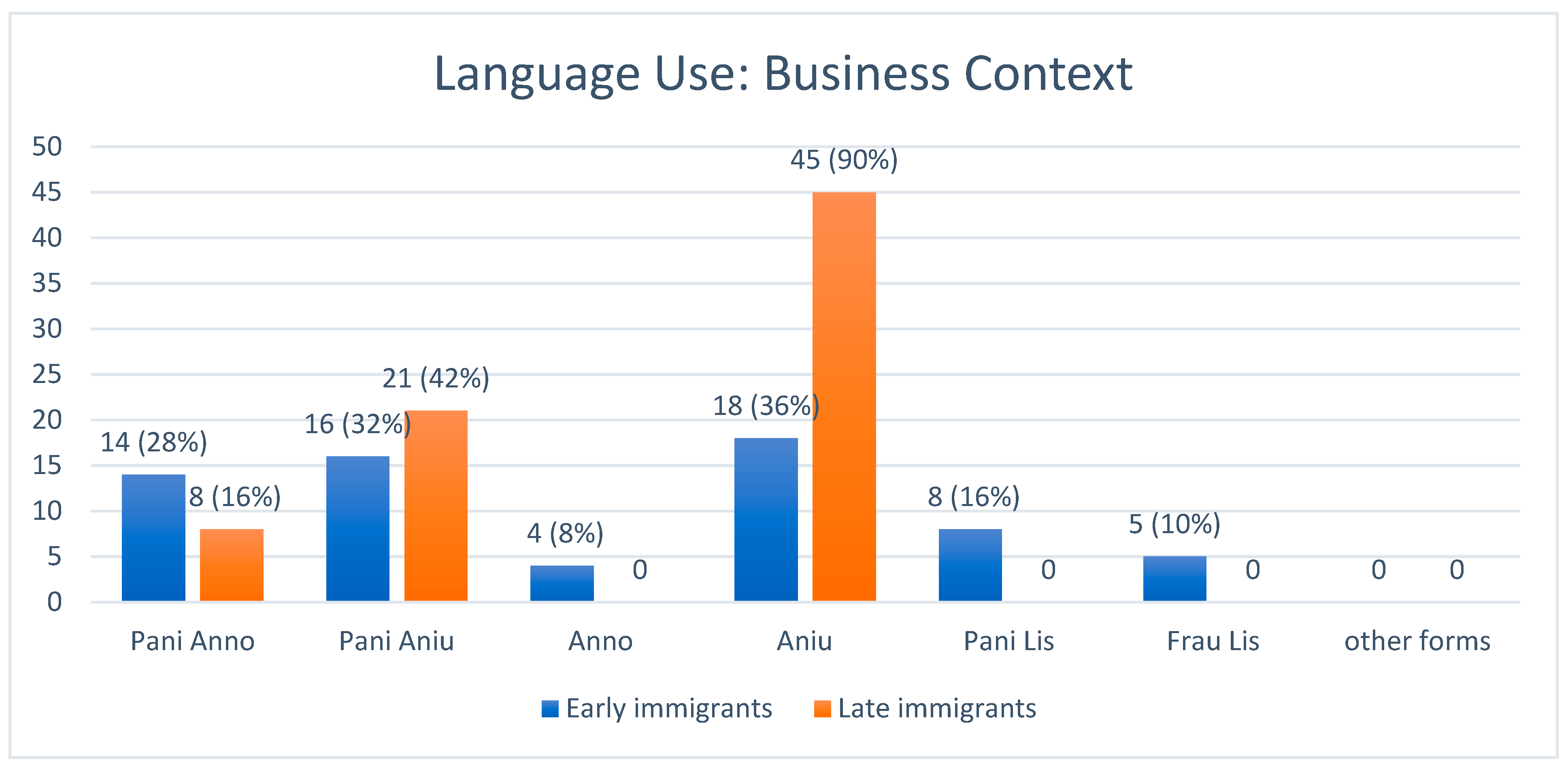

- Situation 1

- [Description:] W ramach praktyk pracuje Pan/Pani w polskiej organizacji, razem z inną praktykantką: Anną Lis. Jak poprosi ją Pan/Pani o pożyczenie czegoś do pisania?

- ‘As part of your internship, you work in a Polish organization, together with another intern, Anna Lis. How would you ask her to lend you a pen?’

- [Possible answers:]

- a. Pani Anno, czy mogłaby mi pani pożyczyć długopis?

- ‘Pani Anna [long form of the first name, vocative], could you lend me a pen?’

- b. Pani Aniu, czy mogłaby mi pani pożyczyć długopis?

- ‘Pani Anja [short form of the first name, vocative], could you lend me a pen?’

- c. Anno, czy mogłabyś mi pożyczyć długopis?

- ‘Anna [long form of the first name, vocative], could you lend me a pen?’

- d. Aniu, czy mogłabyś mi pożyczyć długopis?

- ‘Anja [short form of the first name, vocative], could you lend me a pen?’

- e. Pani Lis, czy mogłaby mi pani pożyczyć długopis?

- ‘Pani Lis, could you lend me a pen?’

- f. Frau Lis, czy mogłaby mi pani pożyczyć długopis?

- ‘Frau Lis, could you lend me a pen?’

- g. inaczej—jak?

- ‘in another way—how?’

- Situation 2

- [Description:] Studiuje Pan/Pani na uniwersytecie i ma zajęcia z Prof. Marią Kowalską. Jak zada jej Pan/Pani pytanie po zajęciach?

- ‘You study at the university and have a class with Professor Maria Kowalska. How would you ask her a question after the class?’

- [Possible answers:]

- a. Pani profesor, czy dostała pani mojego maila?

- ‘Pani Professor, have you received my email?’

- b. Proszę pani, czy dostała pani mojego maila?

- ‘[*Please], have you received my email?’

- c. Profesor Kowalska, czy dostała pani profesor mojego maila?

- ‘Professor Kowalska, have you received my email?’

- d. Pani Kowalska, czy dostała pani mojego maila?

- ‘Pani Kowalska, have you received my email?’

- e. Frau Kowalska, czy dostała pani mojego maila?

- ‘Frau Kowalska, have you received my email?’

- f. Pani profesor Kowalska, czy dostała pani mojego maila?

- ‘Pani Professor Kowalska, have you received my email?’

- g. Frau profesor Kowalska, czy dostała pani mojego maila?

- ‘Frau Professor Kowalska, have you received my email?’

- h. inaczej—jak?

- ‘in another way—how?’

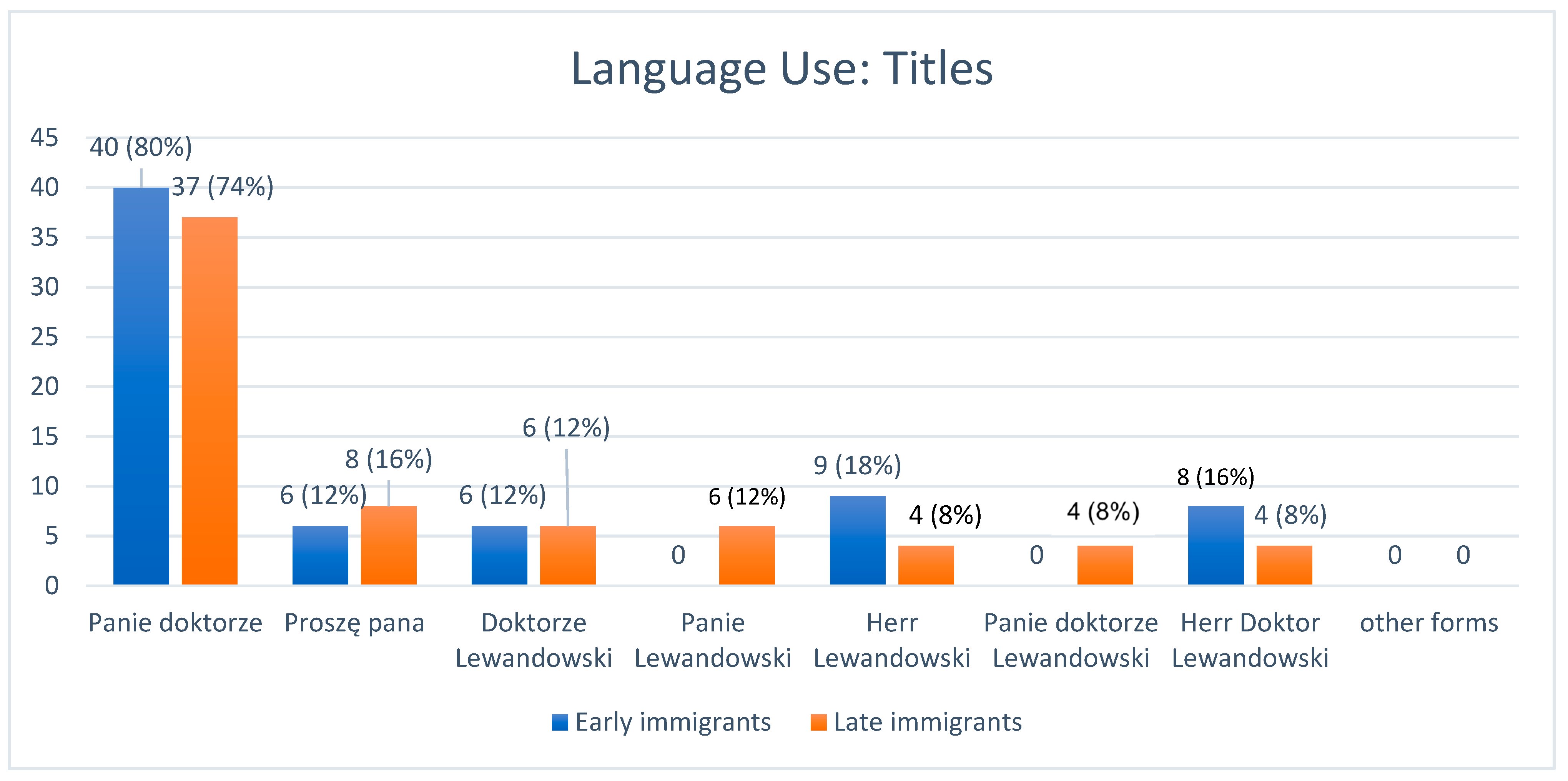

- Situation 3

- [Description:] Jest Pan/Pani u polskojęzycznego lekarza, Jana Lewandowskiego, który jutro zaczyna urlop. Jak zapyta go Pan/Pani o termin powrotu do pracy?

- ‘You are at a Polish-speaking doctor, Jan Lewandowski, who is starting his vacation tomorrow. How would you ask him when he will return to work?’

- [Possible Answers:]

- a. Panie doktorze, do kiedy jest pan na urlopie?

- ‘Herr Doktor [=Doctor], how long will you be on vacation?’

- b. Proszę pana, do kiedy jest pan na urlopie?

- ‘[Please], how long will you be on vacation?’

- c. Doktorze Lewandowski, do kiedy jest pan doktor na urlopie?

- ‘Doctor Lewandowski, how long will you be on vacation?’

- d. Panie Lewandowski, do kiedy jest pan na urlopie?

- ‘Mr. Lewandowski, how long will you be on vacation?’

- e. Herr Lewandowski, do kiedy jest pan na urlopie?

- ‘Mr. Lewandowski, how long will you be on vacation?’

- f. Panie doktorze Lewandowski, do kiedy jest pan na urlopie?

- ‘Dr. Lewandowski, how long will you be on vacation?’

- g. Herr Doktor Lewandowski, do kiedy jest pan na urlopie?

- ‘Dr. Lewandowski, how long will you be on vacation?’

- h. inaczej—jak?

- ‘in another way—how?’

6. Discussion and Outlook

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2 | Second person |

| 3 | Third person |

| FEM | Feminine |

| MASC | Masculine |

| PL | Plural |

| SING | Singular |

| 1 | All abbreviations used in the paper are explained in the Abbreviations. |

References

- Aalberse, S., Backus, A., & Muysken, P. (2019). Heritage languages: A language contact approach (=Studies in bilingualism 58). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg, J. (2005). Zur vitalität slavischer idiome in deutschland. Eine empirische studie zum sprachverhalten slavophoner immigranten. Otto Sagner. [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison, J. (2001). Language change: Progress or decay? (3rd ed.) Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Albarracin, D., & Shavitt, S. (2018). Attitudes and attitude change. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankenbrand, K. (2013). Höflichkeit im wandel: Entwicklungen und tendenzen in der höflichkeitspraxis und dem laienlinguistischen höflichkeitsverständnis der bundesdeutschen sprachgemeinschaft innerhalb der letzten fünfzig Jahre [Doctoral dissertation, Universität Heidelberg]. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, A. (2002). Das kulturelle gedächtnis: Schrift, erinnerung und politische identität in frühen hochkulturen (5th ed.). C.H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Avramenko, M., Warditz, V., & Meir, N. (2024). Heritage Russian in contact with Hebrew and German: Cross-linguistic study of requests. International Journal of Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. (1992). Attitudes and language. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, P., & Mous, M. (1994). Language contact and language change. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bartmiński, J. (2007). Polish cultural studies: Language, tradition, and identity. Wydawnictwo UMCS. [Google Scholar]

- Beetz, H. (1990). Höflichkeit im gesellschaftlichen wandel. In H. Beetz, & M. Kiefer (Eds.), Sprachwandel und gesellschaft (pp. 235–250). Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, T. (1995). Versuch einer historischen typologie ausgewählter slavischer anredesysteme. In R. Rathmayr (Ed.), Slavistische linguistik 1994 (pp. 15–64). Sagner. [Google Scholar]

- Bogusławski, A. (1996). Deutsch und Polnisch als beispiele eines «egalitären» und eines «antiegalitären» anredesystems. In S. Gajda, & J. Laskowski (Eds.), Slawische und Deutsche sprachwelt. Typologische spezifika der slawischen Sprachen im vergleich mit dem Deutschen (pp. 78–86). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacchi, S. (2013). (Un)Höflichkeit. Eine kulturologische analyse Deutsch-Italienisch-Polnisch. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Borbély, A. (1995). Attitudes as a factor of language choice: A sociolinguistic investigation in a bilingual community of romanian-hungarians. Acta Linguistica Hungarica, 43(3/4), 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, D. (2013). Language attitudes: The key factor in language maintenance. In D. Bradley, & M. Bradley (Eds.), Language endangerment and language maintenance: An active approach (pp. 1–10). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R., & Ford, M. (1961). Address in American English. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(2), 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R., & Gilman, A. (1960). The pronouns of power and solidarity. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Style in language (pp. 253–276). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, A. (1916). Ty—Wy—Pan. Kartka z dziejów próżności ludzkiej. Drukarnia Literacka. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S., & Erskine, A. (2010). Language attitudes and language change. In S. Clarke (Ed.), Newfoundland and labrador English (pp. 1–10). Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, M. (2003). Dynamics of language contact. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Czachur, W. (2004). Die gebundenen anredeformen als mittel der grammatikalisierten honorifikation im Deutschen und Polnischen. Studia Niemcoznawcze—Studien zur Deutschkunde, 27, 741–752. [Google Scholar]

- Czachur, W. (2005). Zu entschuldigungsformeln im Deutschen und Polnischen. Studia Niemcoznawcze—Studien zur Deutschkunde, 29, 753–769. [Google Scholar]

- Czochralski, J. (1994). Różnice w zakresie językowych zachowań Polaków i Niemców. In F. Grucza (Ed.), Uprzedzenia między Polakami i Niemcami. Materiały polsko-niemieckiego sympozjum naukowego 9–11 grudnia 1992 Görlitz—Zgorzelec (pp. 140–146). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Dauzat, A. (1927). Les patois. Librairie Delagrave. [Google Scholar]

- De Bot, K., & Clyne, M. (1994). A 16-year longitudinal study of language attrition in Dutch immigrants in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 15(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, A. (2023). The danger of bilingual–monolingual comparisons in applied psycholinguistic research. Applied Psycholinguistics, 44(3), 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragojevic, M., Fasoli, F., Cramer, J., & Rakić, T. (2021). Toward a century of language attitudes research: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 40, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinina, I., Polinsky, M., & Montrul, S. (2021). Pragmatics in Heritage Languages. In S. Montrul, & M. Polinsky (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of heritage languages and linguistics (pp. 728–758). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dubisz, S. (2001). Język polski poza granicami kraju. In S. Gajda (Ed.), Język polski (pp. 492–514). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Duszak, A. (1998). Politeness in east-west communication. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlich, K. (2005). Politeness and ideology in historical perspective. In R. Watts, S. Ide, & K. Ehlich (Eds.), Politeness in language: Studies in its history, theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 71–107). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Fasold, R. W. (1987). The sociolinguistics of society. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J. A. (1966). Language maintenance and language shift: A theoretical framework. Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J. A. (1991). Reversing language shift: Theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened languages. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J. A. (2001). 300-Plus years of heritage language education in the United States. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Heritage languages in America: Preserving a national resource (pp. 81–89). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Fought, C. (2006). Language and ethnicity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini, R. (1998). Varianz innerhalb zweier sprachsysteme: Eine handlungswahl? In B. Henn-Memmesheimer (Ed.), Sprachvarianz als ergebnis von handlungswahl (pp. 11–26). Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Gajda, R., & Kwiatkowska, E. (2017). Polish politeness forms: A sociolinguistic perspective. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 25(2), 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- García, O. (2003). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism, and education. Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gardani, F., Arkadiev, P., & Amiridze, N. (Eds.). (2005). Borrowed morphology (=Language contact and bilingualism, 8). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimova, A., & Lyutikova, E. (2020). Intralingual variation in acceptability judgments and production: Three case studies in Russian grammar. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(348), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzelak, J. (2012). Language and politeness in institutional contexts. Scholar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gries, S. T. (2013). Quantitative corpus linguistics with R: A practical introduction. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ferreira, M. (Ed.). (2010). Multilingual norms. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Gumperz, J. (1982). Discourse strategies. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heine, B., & Kuteva, T. (2005). Language contact and grammatical change. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, B., van Meurs, F., & Kakisina, B. (2023). The effects of L1 and L2 writers’ varying politeness modification in English emails on L1 and L2 readers. Journal of Pragmatics, 204, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. (1995). Women, men and politeness. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby, M. (2011). The impact of language attitudes on address forms in the Scottish Gaelic community. Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- House, J. (2005). Politeness in Germany: Politeness in culture and discourse. In L. Hickey, & M. Stewart (Eds.), Politeness in Europe (pp. 13–28). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Huszcza, R. (2005). Politeness in Poland: From ‘titlemania’ to grammaticalised honorifics. In L. Hickey, & M. Stewart (Eds.), Politeness in Europe (pp. 218–233). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskuła, M. (2011). The vocative case in modern Polish: Functions and usage. Studia Linguistica, 59(3), 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B. B. (1983). The indianization of English: The English language in India. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kroskrity, P. V. (2004). Language ideologies and the politics of language shift. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W. (2001). Principles of linguistic change: Social factors. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Léglise, I., & Moreano, S. (2017). From varieties in contact to the selection of linguistic resources in multilingual settings. In R. Bassiouney (Ed.), Identity and dialect performance: A study of communities and dialects (pp. 143–159). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lerchner, G. (1995). Sprachwandel und sprachverfall: Beobachtungen zum gegenwärtigen Deutsch. In E. Wiegand (Ed.), Sprachkultur in der Alltagskommunikation (pp. 107–122). Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C. (2004). Language attitudes and language shift in Hong Kong. University of Hong Kong Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., & Wei, L. (2022). Language attitudes: Construct, measurement, and associations with language achievements. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 43(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, A. (2006). Sprachliche angleichung an das Amerikanische—Modernisierung durch Amerikanisierung? In A. Linke, R. Möhlig, & P. Schlobinski (Eds.), Sprachkultur in der wissensgesellschaft (pp. 103–121). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- López, M. L. (2010). The loss of traditional address forms among indigenous Spanish speakers in the U.S. University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Łaziński, M. (2006). O panach i paniach: Polskie rzeczowniki tytularne i ich asymetria rodzajowo-płciowa. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2007). Disinventing and reconstituting languages. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Mesthrie, R. (2006). Language in South Africa. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mesthrie, R., & Bhatt, R. (2008). World Englishes: The study of new linguistic varieties. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.-B. (2013). Diasporas et développement. Hommes et migrations, 1303(3), 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, M. B. (2005). Von Pan zu Pan: Zur Geschichte der polnischen Anrede besonders im 18. Jahrhundert. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Mleczko, E. (2020). Formal and informal address in Polish healthcare communication. Journal of Pragmatics, 160, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. (2017). Politeness and the Greek diaspora: Emic perceptions, situated experience, and a role for communicative context in shaping behaviors and beliefs. Intercultural Pragmatics, 14(2), 165–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühleisen, S. (2002). Creole discourse: Exploring prestige and style in caribbean English creole. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J. (2009). Syntactic judgment experiments. Language and Linguistics Compass, 3(1), 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagórko, A. (1992). Wie Menschen sich in verschiedenen Sprachen anreden–ein Beitrag zur Höflichkeitsgrammatik. In G. Falkenberg, N. Fries, & J. Puzynina (Eds.), Wartościowanie w języku i tekście na materiale polskim i niemieckim (pp. 87–297). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Nagórko, A. (2005). Grzeczność wasza i nasza. In M. Marcjanik (Ed.), Grzeczność nasza i obca (pp. 69–86). Warszawa. [Google Scholar]

- Neuland, E. (2010). Sprachwandel in der Gesellschaft: Aspekte soziolinguistischer Veränderung. Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch, K. (2006). Polish grammar. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- On, S. B., & Meir, N. (2022). Requests and apologies in two languages among bilingual speakers: A comparison of heritage English speakers and English-and Hebrew-dominant bilinguals. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1017715. [Google Scholar]

- Priestly, T., McKinnie, M., & Hunter, K. (2009). The contribution of language use, language attitudes, and language competence to minority language maintenance: A report from Austrian Carinthia. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 17, 275–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptashnyk, S. (2010). Variation und historische Sprachkontaktforschung am beispiel der multilingualen Stadt Lemberg. In P. Gilles, J. Scharloth, & E. Ziegler (Eds.), Variatio delectat. Empirische evidenzen und theoretische passungen sprachlicher variation (pp. 287–308). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Puzynina, T. (2015). Politeness and address forms in Polish. Linguistica Silesiana, 36, 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Rampton, B. (2006). Language in late modernity: Interaction in an urban school. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Romanowski, P., & Seretny, A. (Eds.). (2024). Polish as a heritage language around the world selected diaspora communities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, J., Bayram, F., DeLuca, V., Di Pisa, G., Dunabeitia Landaburu, J. A., Gharibi, K., Hao, J., Kolb, N., Kubota, M., Kupisch, T., Laméris, T., Luque, A., van Osch, B., Pereira Soares, S. M., Prystauka, Y., Tat, D., Tomic, A., Voits, T., & Wulff, S. (2022). Monolingual comparative normativity in bilingualism research is out of “control”: Arguments and alternatives. Applied Psycholinguistics, 44(3), 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E. B., Giles, H., & Sebastian, R. C. (1982). Language attitudes and social identity. Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salmons, J. C. (2004). Language maintenance and shift in germanic minorities in Europe: Address forms and social change. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Seliščev, A. M. (1928). Jazyk revoljucionnoj ėpochi. Rabotnik Prosveščenija. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, G. (1981). W sprawie charakterystyki gramatycznej wyrazów pan, pani, państwo. Studia z Filologii Polskiej i Słowianskiej, 20, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco, M. M., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2005). The new immigration: An interdisciplinary reader. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, S. A. (2016). Sociolinguistic variation: Theories, methods, and applications (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, N. (Ed.). (2019). The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and pragmatics. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga, M. (2020). Methodological challenges in heritage language research: Sample size and representativeness. Heritage Language Journal, 17(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, R. (2008). Language, identity, and politeness: Address forms in welsh in contact with English. University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, S. G. (2001a). Contact-induced language change and pidgin/creole genesis. In N. Smith, & T. Veenstra (Eds.), Creolization and contact (pp. 249–262). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, S. G. (2001b). Language contact: An introduction. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, S. G. (2017). Contact as a source of language change. In B. D. Joseph, & R. D. Janda (Eds.), The handbook of historical linguistics (pp. 687–712). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, S. G., & Kaufman, T. (1988). Language contact, creolization and genetic linguistics. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tomiczek, E. (1983). System adresatywny wspólczesnego jezyka polskiego i niemieckiego: Socjolingwistyczne studium konfrontatywne. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaliki, L. (2004). Language shift in the Greek diaspora: Attitudes toward language maintenance and shift. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Press. [Google Scholar]

- Veith, W. (2002). Soziolinguistik. Ein arbeitsbuch. Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Veltman, C. (1983). Language shift in the United States. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Warditz, V. (2012). Formy obraščenija v russkom jazyke diaspory kak markery “svoego” i „čužogo“. In N. Rozanova (Ed.), Russkij jazyk segodnja, 5. Problemy rečevogo obščenija (pp. 75–81). Flinta. [Google Scholar]

- Warditz, V. (2016). Slavische Migrationssprachen in Deutschland: Zur Erklärungskraft von Sprachwandelfaktoren in Kontaktsituationen. In S. Ptashnyk, R. Beckert, P. Wolf-Farré, & M. Wolny (Eds.), Gegenwärtige Sprachkontakte im Kontext der Migration (pp. 99–118). Universitätsverlag Winter. [Google Scholar]

- Warditz, V. (2017). Brückners Höflichkeitskonzept (1916): Linguistik oder Ideologie? Linguistische Untersuchung des sprachpolitischen Manifests eines Universalgelehrten. Zeitschrift für Slawistik, 62(2), 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warditz, V. (2019). Varianz im Russischen: Von funktionalstilistischer zur soziolinguistischen Perspektive. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Warditz, V. (2023). Sprachkontakt und Anredesystem: Eine experimentelle Studie zum Migrationspolnischen in Deutschland. Schnittstelle Germanistik, 3(1), 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warditz, V. (2025). Bi-aspectual verbs in heritage Russian against the background of baseline language dynamics. Russian Linguistics, 49, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R. J. (2005). Linguistic politeness and politic verbal behaviour: Reconsidering claims for universality. In R. Watts, S. Ide, & K. Ehlich (Eds.), Politeness in language: Studies in its history, theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 43–69). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, R. J., Ide, S., & Ehlich, K. (Eds.). (2005). Politeness in language: Studies in its history, theory and practice (2nd ed.). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreich, U. (1953). Languages in contact: Findings and problems. Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Weskott, T., & Fanselow, G. (2011). On the informativity of different measures of linguistic acceptability. Language, 87(2), 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, A. (1991). Cross-cultural pragmatics: The semantics of human interaction. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, H., & Bracke, Y. (2021). Registerdifferenzierung im Namdeutschen: Informeller und formeller Sprachgebrauch in einer vitalen Sprechergemeinschaft. In C. Földes (Ed.), Kontaktvarietäten des Deutschen im Ausland (pp. 273–293). Beiträge zur interkulturellen Germanistik 14. Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Winford, D. (2003). An introduction to contact linguistics. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski-Moskoff, I. (2018). Knowledge of forms of address in Polish heritage speakers. Heritage Language Journal, 15(1), 116–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagmur, K. (1997). First language attrition among Turkish speakers in Sydney. Tilburg University Press. [Google Scholar]

| First Generation | Second Generation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Responses | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| L1 German | 8 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 8 | 8% |

| L1 Polish | 77 | 77% | 45 | 45% | 24 | 24% |

| L1 Polish and L1 German | 23 | 23% | 45 | 45% | 18 | 18% |

| Total | 100 | 100% | 50 | 50% | 50 | 50% |

| First Generation | Second Generation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Responses | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| German in the family (as a first home language) | 34 | 34% | 12 | 12% | 22 | 22% |

| Polish in the family (as a first home language) | 66 | 66% | 38 | 38% | 28 | 28% |

| Polish in the workplace | 22 | 22% | 16 | 16% | 6 | 6% |

| Total Responses | Age of Immigration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Immigrants (=Second Generation) | Late Immigrants (=First Generation) | |||||

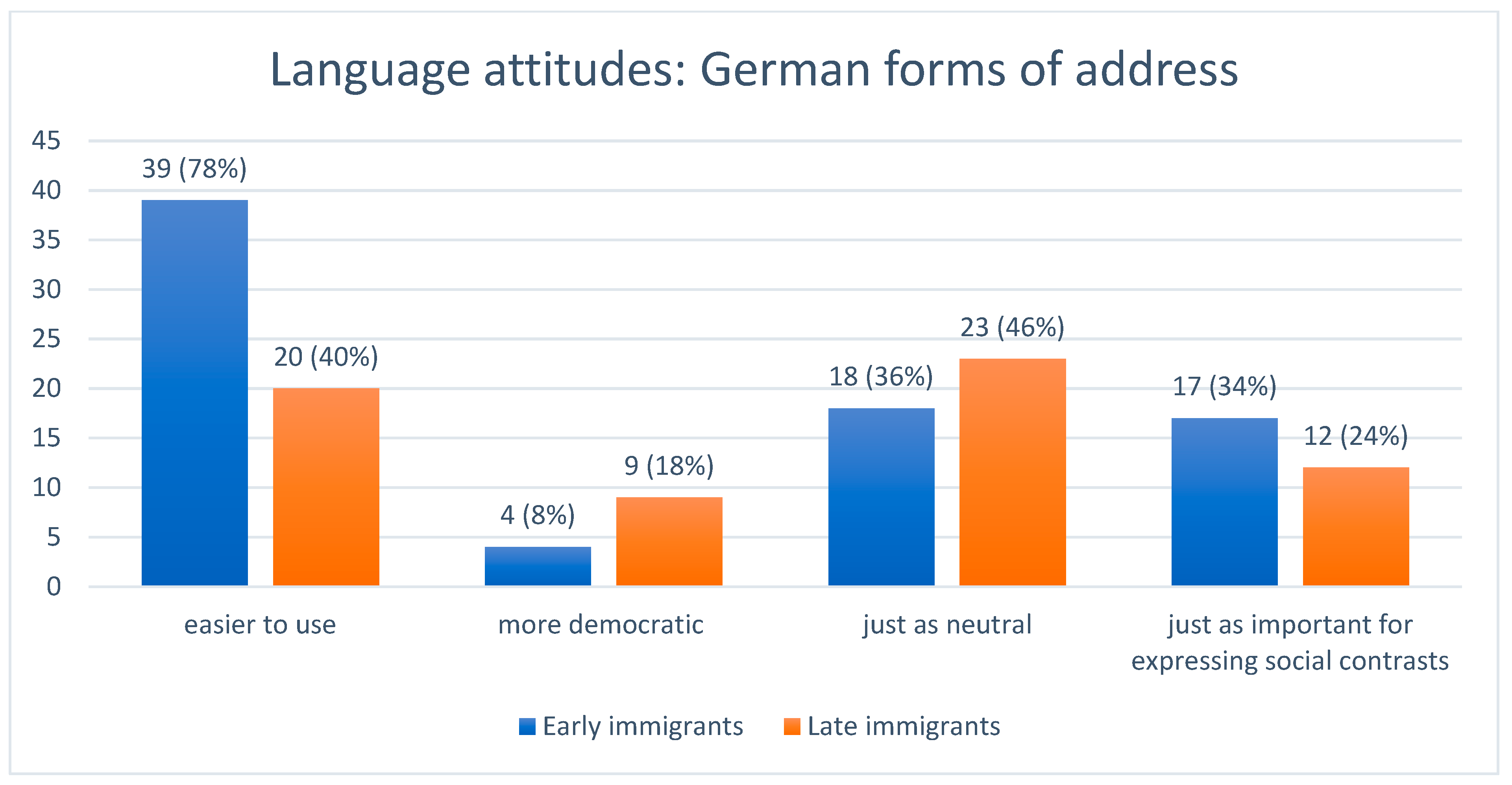

| 1. Question: The German forms of address are… | ||||||

| … easier to use than Polish ones | 59 | 59% | 39 | 78% | 20 | 40% |

| … more democratic than Polish ones | 13 | 13% | 4 | 8% | 9 | 18% |

| … just as neutral | 41 | 41% | 18 | 36% | 23 | 46% |

| … just as important for expressing social contrasts | 29 | 29% | 17 | 34% | 12 | 24% |

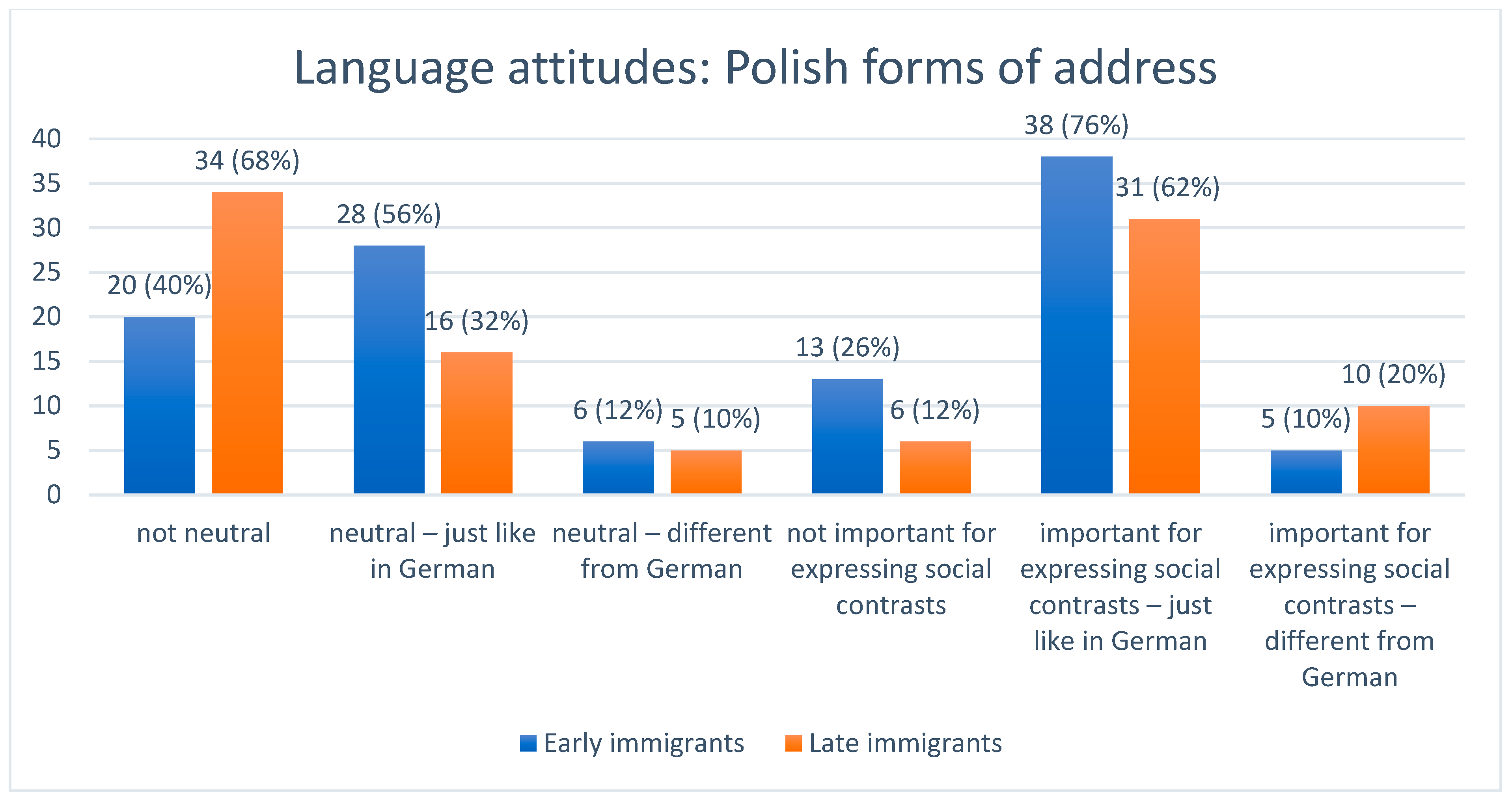

| 2. Question: The Polish forms of address with titles are… | ||||||

| … not neutral | 54 | 54% | 20 | 40% | 34 | 68% |

| … neutral—just like in German | 44 | 44% | 28 | 56% | 16 | 32% |

| … neutral—different from German | 11 | 11% | 6 | 12% | 5 | 10% |

| … not important for expressing social contrasts | 19 | 19% | 13 | 26% | 6 | 12% |

| … important for expressing social contrasts—just like in German | 69 | 69% | 38 | 76% | 31 | 62% |

| … important for expressing social contrasts—different from German | 15 | 15% | 5 | 10% | 10 | 20% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warditz, V. The Formal Address Forms in Heritage Polish in Germany: The Dynamics of Transgenerational Language Change. Languages 2025, 10, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070154

Warditz V. The Formal Address Forms in Heritage Polish in Germany: The Dynamics of Transgenerational Language Change. Languages. 2025; 10(7):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070154

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarditz, Vladislava. 2025. "The Formal Address Forms in Heritage Polish in Germany: The Dynamics of Transgenerational Language Change" Languages 10, no. 7: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070154

APA StyleWarditz, V. (2025). The Formal Address Forms in Heritage Polish in Germany: The Dynamics of Transgenerational Language Change. Languages, 10(7), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070154