Linguistic Diversity in German Youth Media—The Use of English in Professionally Produced Instagram Memes and Reels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characteristics of Language Used in Journalistically Produced Instagram Content

- (1)

- Wenn während deiner Präsi deineFriends in der letzten Reihe sitzen.(When during your presentation yourfriends are sitting in the back row.)

- (2)

- Flirten mit RizzFestival Edition(Flirting with rizzFestival edition)

- (3)

- Radio X FestivalCountdown(Radio X festivalCountdown)7

- (4)

- Kostüme an Fastnacht be like:Meine Friends: Aang aus Avatar, Geralt aus The WitcherIch: Badewanne(Costumes for carnival be like:My friends: Aang from Avatar, Geralt from The WitcherMe: Bathtub)

- (5)

- POV: Du suchst einen Therapieplatz und bekommst sogar einenIt’s been 84 years.(POV: You look for therapy treatment and you’re actually offered a placeIt’s been 84 years.)

- (6)

- Meine BFF und ich, wie wir mit jeweils 10 Fehlerpunkten9 und bodenlos viel Glück in der Prüfung durch die Gegend fahren:(My BFF and me, when we are driving around with 10 error points each and a lot of luck in the test:)

- (7)

- Ich, sobald meine Katze irgendwas Süßes macht:(Me, when my cat does something cute:)

- (8)

- Warum FOMO bei gutem Wetter besonders kickt(Why FOMO kicks particularly well in good weather)

- (9)

- POV: Du hast ein Date mit einem People Pleaser(POV: You have a date with a people pleaser)

3. Methodology

3.1. Linguistic Ethnography at the Youth Radio Station and Online Ethnography on the Station’s Instagram Profile

3.2. Qualitative Interviews

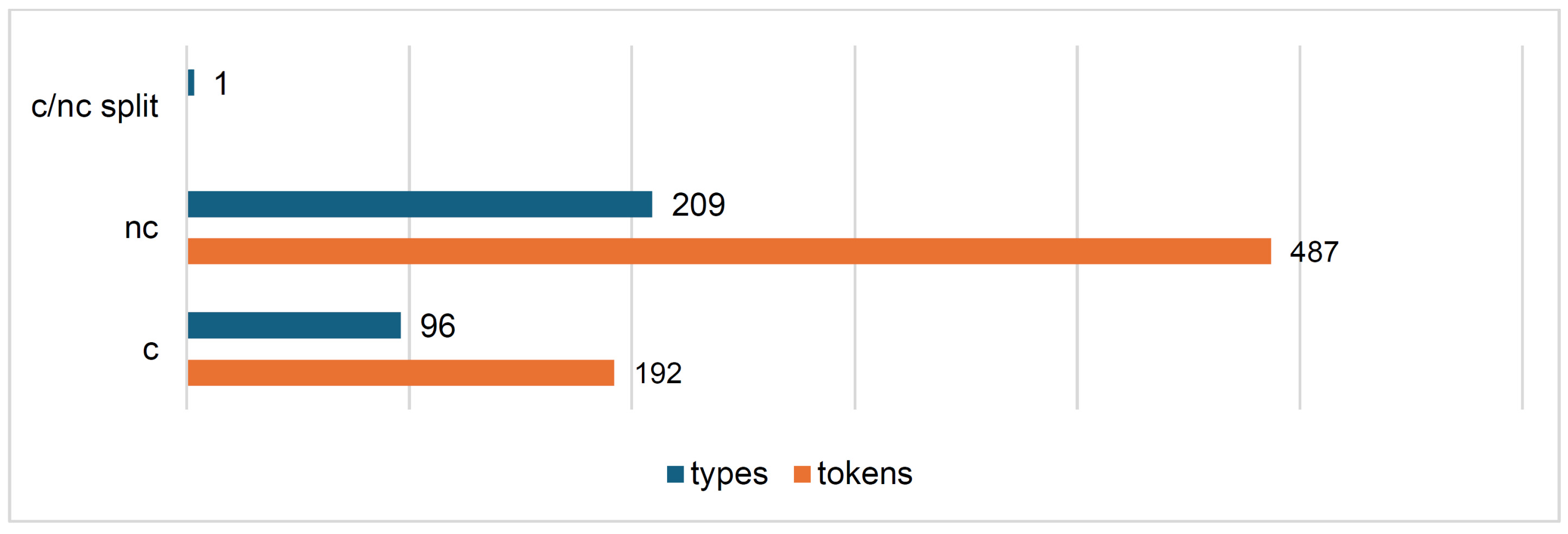

3.3. Identification and Quantitative Analysis of Anglicisms

4. Possible Facilitating Factors

4.1. Pragmatic Markedness and Diachronic Development of Anglicisms

4.2. Lexical Fields of Anglicisms

4.3. Brevity of Expression

4.4. Semantic Reasons for the Use of Anglicisms

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Pragmatic Markedness of Borrowings and Diachronic Development

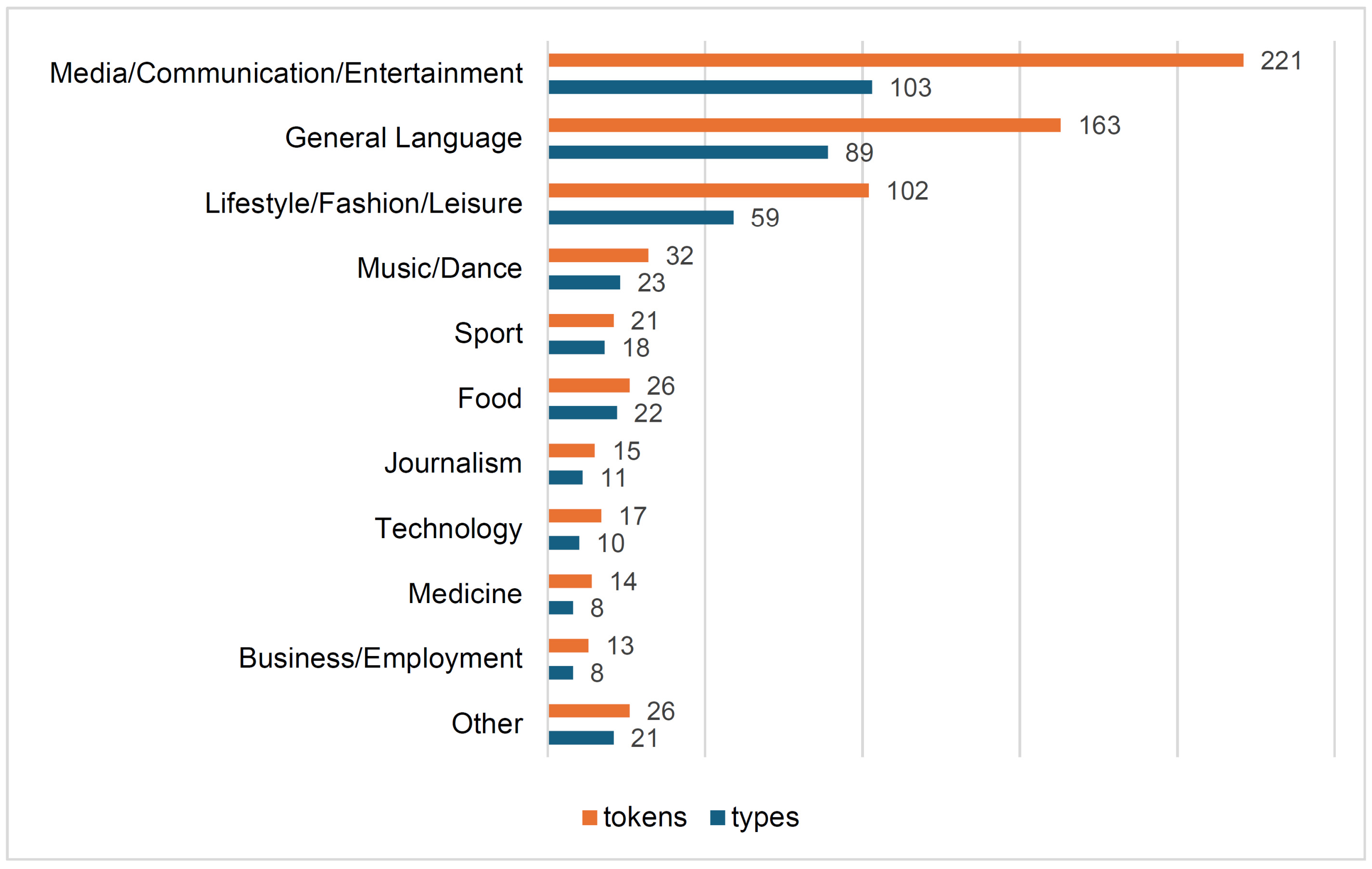

5.2. Lexical Fields of Anglicisms on Instagram

5.3. Brevity of Expression

Also ich glaub Millennial Leute, die sind sehr in diesem Denglisch drin und so … äm … und Gen Z ist schon wieder in so Kürzeln drin.

(Well, I think millennial people are very much into this Denglisch and so on … em … and Gen Z is already into such abbreviations again.)

5.4. Semantic Reasons for and Journalists’ Perspectives on the Use of English

Und dann wird es [die Verwendung von Anglizismen] aber halt unterstützt dadurch, dass wir das auch im Sender schon viel benutzen. Also ich benutze die auch einfach viel, ich hab mich jetzt auch schon drauf eingestellt. Man ist einfach auch in nem jungen Kosmos bei Radio X, und deswegen ist das jetzt nicht erzwungen. Auch wenn ich mich mit Kolleginnen und Kollegen unterhalte, dann benutze ich die Wörter.

And he continued:(And then it [the use of anglicisms] is also supported by the fact that we also use it a lot at the station. Well, I just use it a lot, I’ve already adapted to it. You’re simply in a young cosmos at Radio X, so it’s not forced. Even when I’m talking to colleagues, I use these words.)

Viele Kollegen gerade aus der Onlineredaktion benutzen noch 10-mal mehr Anglizismen, die ich dann auch nicht mehr benutze.

According to the researcher’s observations, journalists work very interactively in the online newsroom and most of the time develop their ideas collectively through conversations. This usually includes anglicisms from the latest social media trends, which they later apply in their memes. Using anglicisms for the purpose of expressing modernity and internationalism has been explored by many previous studies, particularly in the context of advertising (Gerritsen et al., 2007; Onysko, 2004; Piller, 2003; Hornikx & van Meurs, 2020; Kelly-Holmes, 2005). While the results for adult contemporary station imaging revealed that not all adult contemporary radio journalists agreed that they use anglicisms for reasons of expressing modernity (Schaefer, 2019), the qualitative interviews and linguistic ethnographic fieldwork at the youth radio station have shown that using English particularly beyond established loanwords is a phenomenon of German youth culture and of expressing modernity. A host explained:(Many colleagues in the online team use 10 times more anglicisms, which I wouldn’t be using.)

Ich würde sagen, dass viele Menschen jetzt auch viel besser Englisch sprechen als früher vielleicht noch und … ja, ich glaub einfach, […] man ist so weltoffener, man ist viel vernetzter weltweit. Also ist es ja auch wichtig die Begriffe zu benutzen und ich würde schon sagen, natürlich ist ja Sprache auch so n bisschen Ausdruck von der Jugendkultur. […] Der Jugend is [Englisch] schon wichtig auch so bisschen zur Identifikation. […] Ich glaube, man will halt da zeigen, dass man so ein bisschen weltoffen ist, international unterwegs ist, dass man weltweit gerne mit Menschen auch in Kontakt tritt … also man konsumiert nicht nur Dinge mehr aus dem eigenen Land oder aus dem eigenen Umkreis, sondern die Kreise sind viel weiter in denen man sich bewegt durch das Internet auch, würde ich sagen, und da braucht man ja auch Englisch.

In line with the journalist’s statement regarding a greater competence of English amongst German youth, a more extensive use of English is also evident in the Instagram corpus, which contained more complex syntactic structures of English and novel anglicisms than the adult contemporary station imaging corpus. The online corpus contained 45 novel anglicism types amounting to 114 tokens, including the anglicisms be like (18 tokens), Blind Ranking (23 tokens) and Hottake (10 tokens). In addition, amongst the 12 top lexemes in terms of frequency, 5 types in the online corpus constitute incipient borrowings such as Friends (12 tokens) and Crush (7 tokens). In contrast, novel anglicisms in the radio station imaging corpus only showed 2 types and 2 tokens. Furthermore, the online corpus also contained 53 types of multiword codeswitches resulting in 65 tokens of these occurrences as opposed to the station imaging corpus, which contained no multiword codeswitches at all. As can be taken from the corpus analysis, while many novel anglicisms and multiword codeswitches are often not explained or translated in meme and reel captions, such unestablished anglicisms—according to most interviewees—are nevertheless very much known to their Instagram community and would otherwise not be used by journalists without a translation. While multiword codeswitches require a certain degree of proficiency in English, all codeswitches found in the online corpus either, as outlined before, are related to popular movie scenes or are commonly known to the station’s audience from other memes or song lyrics, such as in the following example.(I would say that many people now speak English much better than they used to and … yes, I just think [...] people are much more cosmopolitan, much more networked worldwide. That’s why it’s important to use the terms, and I would say language is, of course, somehow an expression of youth culture. [...] It [English] is important for young people for their identity. […] I think one wants to show that one is a bit cosmopolitan and international, that one likes to get in touch with people around the world ... so one no longer only consumes things from one’s own country or locality, but the circles in which one moves are much wider thanks to the internet, I would say, and that’s where you need English.)

- (10)

- I just wanna be part of your symphony.

Heute wollte ich Prediction benutzen für die Bundesliga-Prediction und ich finde dieses Wort, das sage ich auch wirklich, weil Vorhersage finde ich ein blödes Wort, also passt überhaupt nicht zu dem, was es ist. […] Habe es nicht genommen, weil gibt halt schon viele, die mit Vorhersage mehr anfangen können als mit Prediction.

(Today I wanted to use Prediction for the Bundesliga prediction, and I find this word, which I really use because I find Vorhersage a stupid word, so it doesn’t fit at all with what it is. […] I didn’t use it because to many people Vorhersage says more than Prediction.)

Wir hatten gestern einen Call-in, der hieß „Was sind underrated Orte in X und X?“ und ich finde also ein deutsches Wort dafür ... also ich finde underrated drückt genau das aus, was ich gerne sagen will. Ich würde sagen, jeder in unserer Zielgruppe versteht, was ich mit underrated meine. Ich hab das natürlich nochmal erklärt, ich hab gesagt, „Orte an die wir unbedingt mal hin gehen müssen, die vielleicht nicht jeder kennt“ und so. Trotzdem wurde sich darüber aufgeregt, dass ich das gesagt hab … per WhatsApp. […] Ich würde aber sagen, vom Namen her war es wahrscheinlich auch eine eher ältere Person. […] Und ich würde behaupten, dass wir bei uns auch mehr Leute so [mit Englisch] erreichen.

(We had a call-in yesterday that went like “What are underrated places in X and X?”, and I find a German word for it ... I think that underrated expresses exactly what I want to say. I would say that everyone in our target group understands what I mean by underrated. Of course, I explained it again, I said “places we absolutely have to go to that perhaps not everyone knows about”. Nevertheless, someone got upset that I said that … via WhatsApp. […] I would say that according to the name it was more of an older person. […] And I would say that we also reach more people that way [using English].)

Na, wer sagt denn noch zu nem Song Hit? Also jeder Song, der auf TikTok viral geht, ist dann ein Hit und äh, das ist einfach nur ein Song. Wir nehmen viral. Song ist viral gegangen. Weil aus der Betrachtung dessen, dass die auf TikTok erfolgreich sind und dann ins Radio kommen. Die [Adult Contemporary Sender] nehmen ja Hit und sagen, „wir sagen euch, was die coolen Sachen sind“ und das passt auch zur Zielgruppe. Aber wir gucken halt ins Internet was cool ist.

From this journalist’s statement, it again becomes evident that whether an anglicism is chosen often does not depend on whether it bears additional pragmatic meaning but rather on whether it is regarded as used in the youth radio station’s online community. In this context, the newsroom observation at the station revealed that conveying modernity (see also Gerritsen et al., 2007; Piller, 2003), as stated above, is not necessarily achieved through the use of established pragmatically marked anglicisms but much more through the use of novel anglicisms and multiword codeswitches.(Well, who would still say Hit to a song? So, every song that goes viral on TikTok is then a Hit and em, that’s just a song. We say viral. The song has gone viral. Because from the point of view that they are successful on TikTok and then are played on radio. They [adult contemporary radio stations] use Hit and say “we tell you what the cool stuff is” and that fits the target group. But we look on the internet to see what’s cool.)

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The term meme was coined by Dawkins (1976) to compare the way cultural behaviours and artefacts are passed on with the biological transmission of genes. In its original sense, it relates to any form of cultural activity that is either taught or learned through observation and imitation (e.g., language, music or fashion). Internet memes are considered as “a piece of culture, typically a joke, which gains influence through online transmission” (Davison, 2012, p. 122). In this paper, however, the term meme will be used in its colloquial sense as referring to an individual (humorous or interesting) item of creative output combining image/video and text overlay that is widely spread online. |

| 2 | Reels are short videos posted on a social media website. |

| 3 | Adult contemporary stations mostly play contemporary pop music and target an audience between 25 and 49 years of age. Adult contemporary radio station imaging constitutes short radio elements sung and/or spoken to promote a station’s hosts and presenters, its music and events organised by a station. This includes radio jingles, openers, stingers, claims, a station’s ID and trailers. |

| 4 | As an alternative to distinguishing between necessary and luxury loans, Onysko and Winter-Froemel (2011) draw on Levinson’s (2000) theory of presumptive meanings to develop the classification of catachrestic and non-catachrestic innovations. See also Section 4.1. |

| 5 | The radio station’s Instagram profile page functions as a means of the station’s online self-advertisement contributing to the station’s image. Against this background, Instagram users are first drawn to the actual image of the memes and to the thumbnails of reels and the captions on them. In order to best compare results of the Instagram corpus with the radio station imaging corpus, spoken content of reels and meme reels was therefore not included in the analysis. |

| 6 | For anonymisation purposes of the station and its journalists, memes and reel thumbnails produced by the station cannot be included. |

| 7 | The name of the youth radio station (replaced with the pseudonym Radio X) as well as the names of journalists cannot be disclosed for anonymisation purposes. |

| 8 | Information about viral images used in memes were retrieved from the meme database KnowYourMeme. https://knowyourmeme.com/ (accessed on 26 January 2025). |

| 9 | The word Fehlerpunkte (error points) relates to the German driving test, in which the learner driver can have a maximum of 10 error points to pass the theory part of the test. |

| 10 | Ethical approval for ethnographic research including interviews was given by the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Nottingham and the University of Limerick. |

| 11 | Statements made by interviewees in this paper express their personal opinions only and do hence not necessarily represent the opinion of the station where they are employed. |

| 12 | Glosses are provided for English lexical items that have experienced orthographic assimilation beyond capitalisation of nouns or semantic change in their usage by German speakers. If no glosses are provided, the example terms given closely resemble the original English lexical items in form and meaning. |

| 13 | Based on the proposition that borrowings and single-word codeswitches are the extremes of a continuum of usage (Matras, 2009; Myers-Scotton, 1993), the term incipient borrowings is used in this paper to refer to an intermediate stage between established borrowings and single-word codeswitches. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Novel anglicisms are English words and phrases that are “not yet commonly accepted as neologisms by speakers of German. An anglicism is regarded as novel and therefore not yet commonly accepted in German … if it (a) is a distinctive combination of word form and meaning not detectable in a common dictionary or even in its more current online version and (b) can only scarcely be found in regularly updated online corpora. Novel anglicisms are therefore not yet part of general language usage by the broader population and include one-offs and ad hoc formations” (Schaefer, 2021, p. 572). |

| 16 | While the lexical field Media/Communication/Entertainment appears rather broad, combining these three categories proved to be useful in the context of radio language in previous studies by the researcher since many anglicisms fit into all three categories simultaneously. Examples from the Instagram corpus of the youth radio station include the anglicisms Influencer and Streaming-Dienst (streaming service). |

| 17 | The anglicism lexemes identified included 258 borrowings, 102 hybrids, 7 pseudo-anglicisms and 5 single-word codeswitches. |

| 18 | A top 100 list of anglicism bases can be found in the Supplementary Materials Table S1. |

| 19 | For non-catachrestic anglicisms that are longer than their near-equivalents, it must be noted that the results of the Instagram and the radio station imaging corpus are largely determined by the repetitive use of one lexical item. In the case of the Instagram data, be like amounted to 18 out of 36 tokens. For adult contemporary radio station imaging, the loanword Service amounted to 50 out of 63 tokens that were longer. |

| 20 | Previous research into loanwords has also shown that loanwords are frequently used to convey in-group identity (see Zenner et al., 2019; Leppänen, 2007). |

References

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. (n.d.) DWDS—Digitales Wörterbuch der Deutschen Sprache. Available online: https://www.dwds.de/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, U. (1993). Anglizismen im Duden: Eine Untersuchung zur Darstellung englischen Wortguts in den Ausgaben des Rechtschreibdudens von 1880–1986. Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coats, S. (2019). Lexicon geupdated: New German anglicisms in a social media corpus. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, P. (2012). The language of internet memes. In M. Mandiberg (Ed.), The social media reader (pp. 120–134). New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dudenverlag. (n.d.) Duden online. Available online: http://www.duden.de (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Feierabend, S., Rathgeb, T., Gerigk, Y., & Glöckler, S. (2024). JIM-Studie 2024: Jugend, Information, Medien. Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest (mpfs). Available online: https://mpfs.de/app/uploads/2024/11/JIM_2024_PDF_barrierearm.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Fiedler, S. (2022). “Mit dem Topping bin ich auch fein”—Anglicisms in a German TV cooking show. Espaces Linguistiques, 4, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, M., Nickerson, C., van Hooft, A., van Meurs, F., Nederstigt, U., Starren, M., & Crijns, R. (2007). English in product advertisements in Belgium, France, Germany, The Netherlands and Spain. World Englishes, 26(3), 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, H. (2015). Danish pseudo-Anglicisms: A corpus-based analysis. In C. Furiassi, & H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Pseudo-English: Studies on false Anglicisms in Europe (pp. 61–98). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J. H., & Schmid, H. (2024). POV: Me, an empath, sensing the linguistic urge ... to study the forms and functions of text-memes. English Today, 40(2), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornikx, J., & van Meurs, F. (2020). Foreign languages in advertising: Linguistic and marketing perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Holmes, H. (2005). Advertising as multilingual communication. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kluge, F., & Seebold, E. (2011). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (25th ed.). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Knospe, S. (2015). Pseudo-Anglicisms in the language of the contemporary German press. In C. Furiassi, & H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Pseudo-English: Studies on false Anglicisms in Europe (pp. 99–122). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache. (2006ff). Neologismenwörterbuch. OWID—Online Wortschatz-Informationssystem Deutsch. Available online: http://www.owid.de/wb/neo/start.html (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Leppänen, S. (2007). Youth language in media contexts: Insights into the functions of English in Finland. World Englishes, 26(2), 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, S. C. (2000). Presumptive meanings: The theory of generalized conversational implicature. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, A. (2017). Multimodal simile: The “when” meme in social media discourse. English Text Construction, 10(1), 106–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C. (2024). English in Germany as a foreign language and as a lingua franca. World Englishes, 43(2), 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matras, Y. (2009). Language contact. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Duelling languages: Grammatical structure in codeswitching. Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, G., Zappavigna, M., Drysdale, K., & Newman, C. E. (2022). More than humor: Memes as bonding icons for belonging in donor-conceived people. Social Media + Society, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onysko, A. (2004). Anglicisms in German: From iniquitous to ubiquitous? English Today, 20(1), 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onysko, A. (2007). Anglicisms in German: Borrowing, lexical productivity, and written codeswitching. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Onysko, A., & Winter-Froemel, E. (2011). Necessary loans—luxury loans? Exploring the pragmatic dimension of borrowing. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(6), 1550–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, A. (2003). Global Englishes, Rip Slyme, and performativity. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(4), 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, A. (2020). Translingual entanglements of English. World Englishes, 39(2), 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, J. (1978). Der Anglizismus im Deutschen: Ein Beitrag zur Bestimmung seiner stilistischen Funktion in der heutigen Presse. Metzler. [Google Scholar]

- Piller, I. (2003). Advertising as a site of language contact. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 23, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plümer, N. (2000). Anglizismus, Purismus, sprachliche Identität: Eine Untersuchung zu den Anglizismen in der deutschen und französischen Mediensprache. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, S. J. (2019). Anglicisms in German media: Exploring catachrestic and non-catachrestic innovations in radio station imaging. Lingua, 221, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S. J. (2021). English on air: Novel anglicisms in German radio language. Open Linguistics, 7, 569–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S. J. (2024). New perspectives on language mobility: English on German radio. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spilioti, T. (2020). The weirding of English, trans-scripting, and humour in digital communication. World Englishes, 39(1), 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter-Froemel, E., Onysko, A., & Calude, A. (2014). Why some non-catachrestic borrowings are more successful than others: A case study of English loans in German. In A. Koll-Stobbe, & S. Knospe (Eds.), Language contact around the globe: Proceedings of the LCTG3 conference (pp. 119–144). Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Zappavigna, M. (2012). Discourse of Twitter and social media: How we use language to create affiliation on the web. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Zenner, E., & Geeraerts, D. (2018). One does not simply process memes: Image macros as multimodal constructions. In E. Winter-Froemel, & V. Thaler (Eds.), Cultures and traditions of wordplay and wordplay research (pp. 167–193). de Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Zenner, E., Hilte, L., Backus, A., & Vandekerckhove, R. (2023). On sisters and zussen: Integrating semasiological and onomasiological perspectives on the use of English person-reference nouns in Belgian-Dutch teenage chat messages. Folia Linguistica, 57(2), 449–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenner, E., Rosseel, L., & Calude, A. S. (2019). The social meaning potential of loanwords: Empirical explorations of lexical borrowing as expression of (social) identity. Ampersand, 6, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| nc | c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | Tokens | Types | Tokens | |

| Med./Com./Ent. | 54 | 109 | 56 | 123 |

| General Language | 79 | 151 | 11 | 13 |

| Lifestyle/Fashion/Leisure | 49 | 90 | 13 | 15 |

| Music/Dance | 19 | 28 | 4 | 4 |

| Food | 15 | 18 | 8 | 9 |

| Sport | 12 | 15 | 6 | 6 |

| Journalism | 8 | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| Business/Employment | 7 | 11 | 1 | 2 |

| Medicine | 6 | 10 | 3 | 5 |

| Technology | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8 |

| Other | 15 | 20 | 6 | 6 |

| Types | Tokens | |

|---|---|---|

| Shorter | 130 | 267 |

| Equal | 57 | 184 |

| Longer | 16 | 36 |

| Split S/E/L | 7 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schaefer, S.J. Linguistic Diversity in German Youth Media—The Use of English in Professionally Produced Instagram Memes and Reels. Languages 2025, 10, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050096

Schaefer SJ. Linguistic Diversity in German Youth Media—The Use of English in Professionally Produced Instagram Memes and Reels. Languages. 2025; 10(5):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050096

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchaefer, Sarah Josefine. 2025. "Linguistic Diversity in German Youth Media—The Use of English in Professionally Produced Instagram Memes and Reels" Languages 10, no. 5: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050096

APA StyleSchaefer, S. J. (2025). Linguistic Diversity in German Youth Media—The Use of English in Professionally Produced Instagram Memes and Reels. Languages, 10(5), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10050096