Whys and Wherefores: The Aetiology of the Left Periphery (With Reference to Vietnamese)

Abstract

- Pour l’enfant, amoureux de cartes et d’estampes,

- L’univers est égal à son vaste appétit.

- Ah! que le monde est grand à la clarté des lampes!

- Aux yeux du souvenir que le monde est petit! …

- To the child, enamoured of prints and maps

- The universe has the size of his vast appetite.

- How large the world seems by the light of a lamp!

- How small it is, now, in memory’s sight!

- Charles Baudelaire, Le Voyage [first stanza]

1. Introduction: Why Peripheral, Why?

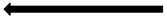

The Cartographic Turn

| (1) | a. | [ Force [ Top* [ Int [ Top* [ Foc [ Top* [ Mod [ Top* [ Qemb [ Fin [IP … ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] (From Rizzi & Bocci, 2017) |

| b. | (42) Criterial freezing: A phrase meeting a criterion is frozen in place |

| (2) | Moodspeech act > Mood evaluative > Moodevidential > Modepistemic > T (Past) > T (Future) > Mood (ir)realis > Modroot/Aspecthabitual/T (Anterior) > Aspectperfect > Aspectprogressive/ Aspectcompletive > Voice > V. |

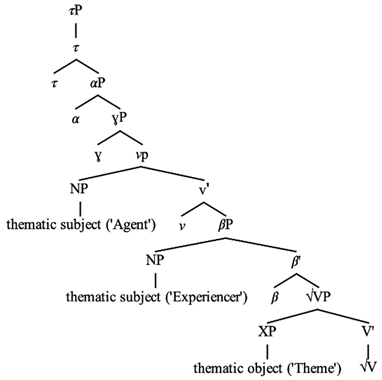

| (3) | |

| |

| (4) | |

| |

“Why is it that we typically find certain properties of ordering and cooccurrence restrictions, rather than others?…[…] Two broadly defined candidates come to mind:13

- i.

- Certain properties could derive from requirements of the interface systems. For instance, it could be that functional head B may necessarily occur under functional head A (thus giving the linear order AB in head-initial languages and BA in head-final languages) because the opposite hierarchical order would yield a structure not properly interpretable…[…]…A special [my emphasis: NGD] case of the impact of interface requirements may be the ordering properties that follow from selectional requirements, e.g., the fact that the Force head in embedded clauses must be high enough to be accessible to higher selectors, which want to know if their complement is a declarative or a question, for instance (Rizzi, 1997);

- ii.

- When the functional heads occurring in specific orders trigger movement, the ordering may be a consequence of locality requirements. For instance, Abels (2012) has argued that almost all the ordering effects observed in the Italian left periphery may follow from the theory of locality based on a version of featural Relativized Minimality, along the lines developed in Starke (2001), Rizzi (2004): if A is a stronger island-creating element than B, then B will not be extractable from the domain of A, neither long-distance, nor locally…”

2. Vietnamese Clause Structure

- i.

- Clause initial conjunctions—including various kinds of subordinating conjunction {complementizer, relativizers}, topic markers, and linking elements. These elements have a fixed distribution relative to one another, and are never found lower in the clausal hierarchy (to the right of the subject): {rằng, liệu, (mà),17 (là)}, {thì, (là)}.

- ii.

- Left peripheral phrasal constituents that are amenable either to a movement or to a co-indexation analysis (Move or Merge): {topicalized XPs, NPs heading relative clauses (see note 1)}.

- iii.

- Speaker/subject-oriented adverbial phrases (e.g., quả thật, ‘indeed’).

- iv.

- Weak indefinites interpreted as universally quantified XPs (which in all probability have been moved to a pre-subject position, given the distribution of the same constituents in the general case);

- v.

- The wh-phrase why (tại sao), which—uniquely in this wh-in situ language—only ever appears to the left of the subject.

2.1. Clause-Initial (Pre-Peripheral?) Conjunctions

| (5) | a. | Tôi | nói | rằng | [ tôi | là | [cán bộ | ngọai giao | [mà | cần | liên hệ | với | sứ quán.]]] | ||||||||||||

| PRN | say | ?? | I | COP | staff | foreign.affairs | REL | need | contact | with | embassy | ||||||||||||||

| ‘I said that I was a diplomatic staff member who needed to contact the embassy.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Cô | gái | hỏi | liệu | [ cô | có thể | đi | đến | bữa tiệc | được | không. ] | ||||||||||||||

| PRN | girl | ask | ?? | PRN | Q? poss. | go | arrive | party | CAN | NEGQ | |||||||||||||||

| ‘The girl asked if she could go to the party.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | [Quyển | sách | [ mà | [ anh | thích | nhất ] ] | thì | bán | chạy. | ||||||||||||||||

| CLF | book | REL | PRN | like | best | TOP | sell | run | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘The book that you like most, (it) is selling well.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

2.1.1. Conjunctions I: {rằng, liệu, là}

| (6) | a. | Ði | tìm | lời đàp: | Liệu rằng | tia UV | có | làm | filler | biến dạng? | ||||||||||||||||||||

| go | find | answer: | ray UV | ASR | make | filler | deform | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Finding the answer: do UV rays cause filler deformation?’19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Ði | tìm | lời đàp: | *Rằng liệu | tia UV | có | làm | filler | biến dạng? | |||||||||||||||||||||

| go | find | answer: | ray UV | ASR | make | filler | deform | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (as a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Liệu | rằng | khi | mất đi | em | có | còn | hối tiếc? [song lyric] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Q | COMP | when | lose | PRN | ASR | still | regret? | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Will I regret it when I lose you?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | *Rằng liệu | khi | mất đi | em | có | còn | hối tiếc? | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| COMP Q | when | lose | PRN | ASR | still | regret? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (as c) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (7) | a. | John | hỏi | rằng liệu | [tôi | có | muốn | hẹn hò | với | anh ấy | không] | |||||||||||||||||

| John | ask | I | Q | want | go.out | with | PRN.DEM | NEGQ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘John asked if I wanted to go on a date with him.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | *John | hỏi | liệu rằng | [tôi | có | muốn | hẹn hò | với | anh ấy | không] | ||||||||||||||||||

| John | ask | I | Q | want | go.out | with | PRN.DEM | NEGQ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (as a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | John | đã | hỏi mẹ | rằng liệu | [mẹ | có thể | đón | cậu bé | không] | |||||||||||||||||||

| John | ANT | ask mother | mother | mother | child | child | NEGQ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘John asked his mother if she could pick him up.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | *John | đã | hỏi mẹ | liệu rằng | mẹ | có | thể đón | cậu bé | không. | |||||||||||||||||||

| John | PAST | ask mother | mother | can | pick up | child | NEGQ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (as c) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

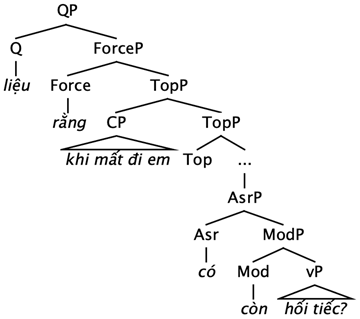

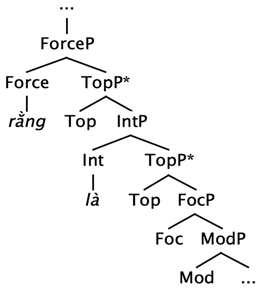

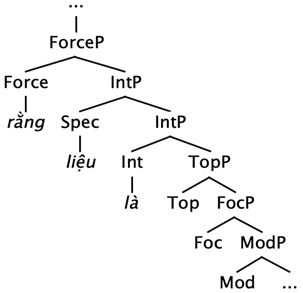

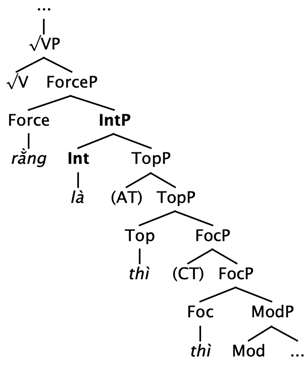

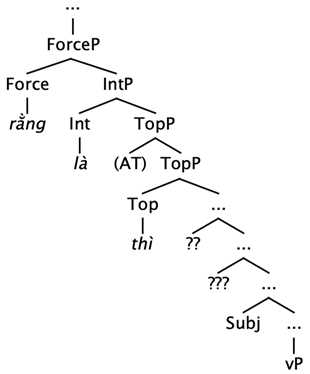

| (8) | |

| |

| (9) | a. | ‘Chẳng | nói, | chẳng rằng!’ | ||||||||||

| NEG | say, | NEG speak | ||||||||||||

| ‘Say nothing!’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | ‘…Phú | ông | xin | đổi | ba | bò, | chín | trâu…’ | ||||||

| …rich | man | ask | exchange | three | cows | nine | buffalo | |||||||

| ‘The rich man asked to exchange three cows and nine buffaloes…’ | ||||||||||||||

| …Bờm rằng: | Bờm | chẳng | lấy trâu… | |||||||||||

| …Bom say: | Bom | NEG | take buffalo | |||||||||||

| ‘..(and) Bom said: “I (Bom) will not take the buffaloes.”’ | ||||||||||||||

| (10) | a. | Murakami | Haruki | nói | rằng: | “Tôi | “Tôi | bạn | biết | tôi | thích bạn …..”20 | |||||||||

| Murakami | Haruku | say | ??: | “I | let | friend | know | I | like friend… | |||||||||||

| ‘Haruki Murakami said: “I’m telling you that I like you…”’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Tôi | thấy | lỗi | nói | rằng: | “Một | số | quy tắc | không | được | áp | dụng nhất” | ||||||||

| I | see | error | say | ??: | 1 | no. | rule | NEG | CAN | apply | correct most | |||||||||

| ‘I see an error saying “A number of rules are not most applicable”’21 | ||||||||||||||||||||

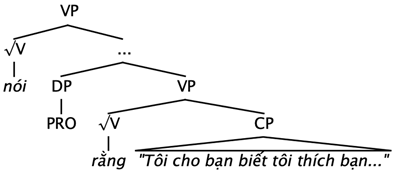

| (11) | a. |

| |

| b. | |

| |

| (12) | a. | “…and he spoke, saying: These are the horns which have scattered Juda every man apart, and none of them lifted up his head …(Zechariah 1:21 KJV)” |

| b. | But the king spoke, saying to Daniel, “Your God, whom you serve continually, He will deliver you…(Daniel 6:16 KJV)” |

| (13) | a. | Nó | không | nói | gì, | [ tuy rằng | [ nó | biết | rất rõ ]]. | ||||||||

| PRN | NEG | say | what, | [ although | PRN | know | very clear | ||||||||||

| ‘He didn’t say anything, even though he clearly knows (the answer).’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | [Tuy rằng | [nhớ | tên ]] [ | nhưng | lại | không | nhớ | ra | gương mặt ] | ||||||||

| although | recall | name | but | again | NEG | recall | out | face | |||||||||

| ‘I remember the name, but not the face.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| (14) | Positioning rằng and liệu (first pass)23 |

| |

| (15) | a. | John | là | người | đàn ông | đứng | ở | đằng | kia. | |||||||

| John | COP | person | gentleman | stand | LOC.COP | location | there | |||||||||

| ‘John is the person standing over there.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | Người | đàn ông | đứng | ở | đằng | kia | là | John. | ||||||||

| person | gentleman | stand | LOC | location | there | COP | John. | |||||||||

| ‘The person standing over there is John.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (16) | a. | Anh ấy | (*là) | cao/thông minh/tốt. | *[AP] | |||

| PRN.DEM | COP | tall/intelligent/nice | ||||||

| ‘He is tall/intelligent/nice.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Cô ấy | (*là) | bận/ | rất vội vàng/ | rất vui. | |||

| PRN.DEM | COP | busy/ | very hurry/ | very happy | ||||

| ‘She is busy/in a great hurry/very happy.’ | ||||||||

| (17) | a. | Anh ấy | ở/(*là) | trên | tàu. | *[PP] | ||||||||

| PRN.DEM | LOC.COP/COP | on | train | |||||||||||

| ‘He is on the train.’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | Tiền | hoàn | thuế | của tôi | ở/(*là) | đâu? | ||||||||

| money | complete | tax | POSS 1.SG | LOC.COP/COP | where | |||||||||

| ‘Where is my tax refund?’ | ||||||||||||||

| c. | Nhìn xem! | Anh ấy | ở/(*là) | kia kìa. | ||||||||||

| look see | PRN.DEM | LOC.COP/COP | DEM3.DEM3 | |||||||||||

| ‘Look! He’s over there.’ | ||||||||||||||

| (18) | a. | Yui | đã | nói | là | đi | đến | nhà | của | bạn.25 | ||||||||

| Yui | PAST | say | CONJ | go | to | house | POSS | friend | ||||||||||

| ‘Yui said (she was) going to her friend’s house.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Tôi | biết | là | chị | đang | yêu | một | ngừoi. | ||||||||||

| I | know | CONJ | she | PROG | love | 1 | person | |||||||||||

| ‘I know that she is in love with someone.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Lan nói | là | (chị ấy) | thích | học | tiếng | Anh. | |||||||||||

| Lan say | CONJ | PRN.DEM | like | study | lge. | English | ||||||||||||

| ‘Lan said she liked learning English.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| (19) | a. | Phải | nói [ | (*là) | [ rằng | [( là) | thế hệ | trẻ | của chúng.ta | rất tài năng.]]]26 | |||||||||||||||||

| must | say | ?? | COMP | ?? | generation | young | POSS PRN | very talented | |||||||||||||||||||

| ‘(I) have to say that our young generation is very talented.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Bạn | có thể | nói | [ (*là) | [ rằng | [ là | mình | ổn, | nhưng…]]]27 | ||||||||||||||||||

| friend | possible | say | ?? | COMP | ?? | self | fine, | but… | |||||||||||||||||||

| ‘You can say that you’re fine, but…’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Quyển | sách [ | (*là) | [ mà | [ (*là) | anh | thích | nhất ]]] | thì | bán | chạy. | ||||||||||||||||

| CLF | book | ?? | REL | ?? | PRN | like | best | TOP | sell | run | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘The book that you like most, (it’s) selling well.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (20) | a. | ‘She asked me, like, What was I doing there?’ | [direct reported] |

| b. | %She asked me what was I doing. [*in standard varieties] | [indirect] | |

| c. | She asked me: “What are you doing here?” | [direct] |

| (21) | a. | Người mẹ | không | biết | *rằng/liệu | bọn trẻ | đang | ngủ | hay thức. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | NEG | know | C/INT | children | PROG | sleep | or awake | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The mother doesn’t know whether the kids are sleeping or awake.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (= the mother is unsure about whether her kids are asleep.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Người mẹ | không | biết | [ rằng/*liệu | [ bọn trẻ | có | đang | ngủ.]] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | NEG | know | C/INT | children | ASR | PROG | sleep | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The mother doesn’t know that the kids are in fact sleeping.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (= the kids are in fact asleep: the mother doesn’t know that fact.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Cô ấy | không biết | [ *rằng/liệu | [ tôi | có | đang | vui vẻ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG know | C/INT | I | Q | PROG | happy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| tại | bữa tiệc | không ]] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| at | party | NEGQ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know whether I am having fun at the party.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (= it is unclear to her whether I am having fun.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Cô ấy không biết | [ rằng/*liệu | [ tôi | đang | vui vẻ | tại | bữa tiệc]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM NEG know | C/INT | I | PROG | happy | at | party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know that I am having fun at the party.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (= I am having fun, indeed, but she doesn’t know that fact.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (22) | a. | Người mẹ | không | biết | là | bọn trẻ | đang | ngủ | hay | thức. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | NEG | know | ?? | children | PROG | sleep | or | awake | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The mother doesn’t know whether the kids are sleeping or awake.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (= the mother is unsure about whether her kids are asleep.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Người mẹ | không | biết | là | bọn trẻ | có | đang | ngủ.] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mother | NEG | know | ?? | children | ASR | PROG | sleep | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘The mother doesn’t know that the kids are sleeping.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (i.e., the kids are in fact asleep: the mother doesn’t know that fact) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Cô ấy | không | biết | là | tôi | đang vui vẻ | tại | bữa tiệc | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN | NEG | know | ?? | I | PROG happy | at | party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| hay | không.29 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| or | NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know whether I am having fun at the party or not.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (= it is unclear to her whether I am having fun.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Cô ấy | không | biết | là | tôi | đang | vui vẻ | tại | bữa tiệc. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG | know | ?? | I | PROG | happy | at | party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know that I am having fun at the party’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (I am having fun, indeed, but she doesn’t know that fact.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (23) | a. | ?Có | nên | *rằng/là | đàn ông | là | trụ cột | gia đình?30 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASR | MOD | men | COP | pillar | family | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Should the man be the family breadwinner?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Có | phải | *rằng/là | cái | chết | là | chấm hết? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ASR | right | CLF | death | COP | end final | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Is Death really the end?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Chắc | *rằng/là | anh ấy | bḷ | tắc | đường | nȇn | đến mưộn. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Likely | PRN.DEM | AUX | delay | road | MOD | come late | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Maybe he was stuck in traffic, so he was late.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Nhà hàng | kia | đông | quá! | Chắc | *rằng/là | đồ ăn | ngon | lắm! | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| restaurant | DEM3 | full | very | likely | food | delicious | very | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘That restaurant is so crowded! The food must be very good.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (24) | a. | Đàn ông | có | nên | là | trụ cột | gia đình?31 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| man | ASR | MOD | COP | pillar | family | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Should men be the family breadwinners?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Cái | chết | ASR | phải | là | chấm | hết? | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CLF | die | ASR | MOD | COP | end | final | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Is death the end?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Anh ấy | chắc | là | bḷ | tắc | đường | nȇn | đến | mưộn. | ||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | likely | CONJ | AUX | delay | road | MOD | come | late | |||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Maybe he was stuck in traffic, so he was late.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Nhà hàng | kia | đông | quá! | Đồ ăn | chắc | là | ngon lắm! | |||||||||||||||||||

| restaurant | DEM3 | full | very | food | likely | CONJ | delicious very | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘That restaurant is so crowded! The food must be very good.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (25) | a. | ma (loro) sembrano | [ usare | la violenza | per altre cose ]. | ||||||||||||||||||

| but they seem-3.PL | use-INF | DET violence | for other things | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘…but they seem to use violence for other things.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | *ma (loro) sembrano | [di | usare | la violenza | per altre cose ]. | ||||||||||||||||||

| but they seem-3.PL | di | use-INF | DET violence | for other things | |||||||||||||||||||

| (as a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | ma sembra | [che | (loro) | usino | la violenza | per altre cose]. | |||||||||||||||||

| but seem-3.SG | that | they | use.SUBJNC.3.PL | DET violence | for other things | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘…but it seems that they use violence for other things.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | *ma (loro) | sembrano | [ che | la violenza | per altre cose]. | ||||||||||||||||||

| but | seem-3.PL | that | use.SUBJNC.3.PL | DET violence | for other things | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘…but they seem that (they) use violence for other things.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| e. | *ma sembra [ (*loro) | di (*loro) | usare | la violenza | per altre cose ]. | ||||||||||||||||||

| but seem-3.sg them | di them | use-INF | DET violence | for other things | |||||||||||||||||||

| ‘[intended]…but they seem to use violence for other things.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| f. | Mi | sembra | di impazzire. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| me.DAT. | seem-3SG | di go.crazy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘It seems like I am going crazy.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (26) | |

|

| (27) | a. | Ho deciso che, la macchina, la comprerò quest’anno. |

| ‘I decided that, the car, I will buy it this year.’ | ||

| b. | Ho deciso, la macchina, di comprarla quest’anno. | |

| ‘I decided, the car, of to buy it this year.’ |

| (28) | a. | John | hỏi | rằng | liệu | (là) | [tôi | có | muốn | hẹn hò | với | anh ấy | không] | |||||||||

| John | ask | COMP | INT | ?? | I | Q | want | go.out | with | PRN.DEM | NEGQ | |||||||||||

| ‘John asked if I wanted to go on a date with him.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | John | đã | hỏi | mẹ | rằng | liệu | (là) | mẹ | có thể | |||||||||||||

| John | PAST | ask | mother | COMP | INT | ?? | mother | Q can | ||||||||||||||

| đón | cậu bé | không] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| pick up | child | NEGQ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘John asked his mother if she could pick him up.’33 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

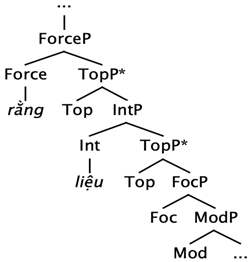

| (29) | |

|

‘In fact,…[…]…elements like che are typically versatile, and can occur in different positions in the clausal spine: in the dialects under consideration, they occur in the highest position as declarative force markers, also in a lower position, lower than the wh-element in indirect questions…

2.1.2. Conjunctions II: {thì, (mà), là}

| (30) | a. | Cô ấy | thì | gặp | anh ấy. | [subject topic] | ||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | TOP | meet | PRN.DEM | |||||||||||||

| ‘Speaking of her, she meets him.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | Anh ấy | thì | cô ấy | gặp. | [object topic] | |||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | TOP | PRN.DEM | meet | |||||||||||||

| ‘Him, she will meet.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| c. | Hồi | trước | thì | cô ấy | gặp | anh ấy. | [adjunct topic] | |||||||||

| time | before | TOP | PRN.DEM | meet | PRN.DEM | |||||||||||

| ‘In the old days, she would meet him.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (31) | a. | Ở | miền Bắc | có | bốn | mùa | nhưng … | [contrast topic] | ||||||||||

| LOC | North | EXIST | four | season | but… | |||||||||||||

| …ở | miền Nam | thì | chỉ | có | hai mùa. | |||||||||||||

| LOC | South | TOP | only | have | two season | |||||||||||||

| ‘In the North, there are four seasons, but in the South, only two.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Mày | thì | gầy, | nó | thì | béo. | (Clark, 1992: [5]) | |||||||||||

| you | TOP | slim, | PRN | TOP | fat | |||||||||||||

| ‘You are slim, and he is fat.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| (32) | a. | [Anh | mà | đến ] | thì | [chị ấy | rất | vui lòng.] [clausal linker] | ||||||||||||||

| PRN | CONJ | come | CONJ | PRN.DEM | very | happy | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘She’ll be very happy, (if) you come.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | [Anh | không | thấy | ai ] | thì | [không | cần | ở lại | một mình.] | |||||||||||||

| PRN | NEG | see | wh | CONJ | NEG | need | stay | oneself | ||||||||||||||

| ‘(If) you don’t see anyone, you don’t have to stay there by yourself.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | (Nếu) | trời | sập | thì | cô ấy | gặp | anh ấy. | |||||||||||||||

| if | sky | fall | CONJ | PRN.DEM | meet | PRN.DEM | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘If the sky falls, she will meet him.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (33) | A: | [Gia đình ấy | có | nhà | to] | [discourse linker] | |||

| family DEM2 | have | house | big | ||||||

| ‘That family has a big house.’ | |||||||||

| B: | Thì | [ cô | ghen tị | à?]. | |||||

| PTL | PRN | jealous | PTL | ||||||

| ‘Are you jealous of them?’ | |||||||||

| (34) | |

|

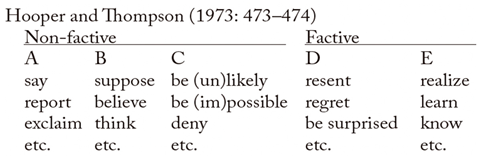

| (35) | a. | I exclaimed that this book, I will never read. (Class A) |

| b. | I think that this book, he read thoroughly. (Class B) | |

| c. | I found out that this book, no one is willing to read for the test (Class E) |

| (36) | a. | *It’s likely that this book, everyone will read for the test. (Class C) |

| b. | *He was surprised that this book, I had not read. (Class D) |

| (37) | a. | My friends said [TOP the more liberal candidates], they had always supported.] |

| b. | My friends tend to support [the more liberal candidates]. [Miyagawa, 2017: [24a]] | |

| c. | *My friends tend [TOP the more liberal candidates] to support. [Miyagawa, 2017: [24b]] |

| (38) |

| (39) | Topic Projection: The topic projection TopP is allowed for the complement of A, B, and E, but not for complement of classes C and D. |

| (40) | a. | Class A: | ||||||||||||||

| Hanako | wa | [ sono | hon | wa | kodomo ga | yonda | to ] | itta | ||||||||

| Hanako | TOP | that | book | TOP | child NOM | read | C | said | ||||||||

| ‘Hanako said that, as for that book, her child read it.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | Class B: | |||||||||||||||

| Hanako | wa | [ sono | hon | wa | kodomo ga | yonda | to ] | sinziteiru. | ||||||||

| Hanako | TOP | that | book | TOP | child NOM | read | C | believe | ||||||||

| ‘Hanako believes that, as for that book, her child read (it).’ | ||||||||||||||||

| c. | Class E: | |||||||||||||||

| Hanako | wa | [ Taroo | wa | kanozyo | ga | suki da | to ] | kizuita. | ||||||||

| Hanako | TOP | Taroo | TOP | she | NOM | like COP | C | realize | ||||||||

| ‘Hanako realized that. as for Taroo, he likes her.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (41) | a. | Class C: | ||||||||||||

| *Hanako | wa | [ sono hon wa | kodomo ga | yonda | koto ] | o | hiteishita. | |||||||

| Hanako | TOP | that book TOP | child NOM | read | C | ACC | denied | |||||||

| ‘Hanako denied that, as for that book, her child read (it).’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | Class D: | |||||||||||||

| *Hanako | wa | [ sono hon wa | zibun ga | yonda | koto ] | o | kookai shita. | |||||||

| Hanako | TOP | that book TOP | self NOM | read | C | ACC | regretted | |||||||

| ‘Hanako regretted that, as for that book, she herself read (it).’39 | ||||||||||||||

| (42) | a. | Hanako | wa | [ sono hon WA | kodomo ga | yonda | koto ] | o | hiteishita | |||||||

| Hanako | TOP | that book CONTR.TOP | child NOM | read | C | ACC | denied | |||||||||

| ‘Hanako denied that as for that book, her child read (it).’ (but not this book) | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | Hanako | wa | [ sono hon WA | zibun ga | yonda | koto ] | o | kookai shita. | ||||||||

| Hanako | TOP | that book CONTR.TOP | self NOM | read | C | ACC | regretted | |||||||||

| ‘Hanako regretted that as for that book, she read (it).’ (but not this one) | ||||||||||||||||

| (1) | [ Force [ Top* [ Int [ Top* [ Foc [ Top* [ Mod [Top* [Qemb [Fin [IP … ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] ] |

| (From Rizzi & Bocci, 2017) |

| (43) | a. | Class A: | |||||||||||||

| AT: Mary | nói | rằng | những cuốn sách đó | thì | cô ấy sẽ đọc trong hôm nay. | ||||||||||

| CT: Mary | nói | rằng | những cuốn sách đó | thì | cô ấy sẽ đọc, | ||||||||||

| không phải những cuốn này. (nói = ‘say’) | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Class B: | ||||||||||||||

| AT: Mary tin rằng | những cuốn sách đó | thì cô ấy có thể đọc | trong hôm | ||||||||||||

| nay. | |||||||||||||||

| CT: Mary tin rằng | những cuốn sách đó | thì cô ấy có thể đọc, | không | ||||||||||||

| phải | những cuốn này. (tin = ‘believe’) | ||||||||||||||

| c. | Class E: | ||||||||||||||

| AT: Mary nhận ra rằng những cuốn sách đó thì cô ấy có thể | |||||||||||||||

| đọc trong hôm nay. | |||||||||||||||

| CT: Mary nhận ra rằng những cuốn sách đó thì cô ấy có thể đọc, | |||||||||||||||

| không phải những cuốn này. (nhận ra = ‘realize’) | |||||||||||||||

| (44) | a. | Class C (1) | ||||

| AT: | ?Mary phủ nhận rằng những cuốn sách đó thì cô sẽ đọc trong hôm nay. | |||||

| Mary deny COMP PL CLS book DEM TOP PRI FUT read in today | ||||||

| *‘Mary denied that those books, she could read today.’ | ||||||

| CT: | ?Mary phủ nhận rằng những cuốn sách đó thì cô sẽ đọc, | |||||

| Mary deny COMP PL CLS book DEM2 TOP PRN FUT read, | ||||||

| không | phải | những cuốn này. | ||||

| not | correct | PL CLS DEM1 | ||||

| *‘Mary denied that those books, she could read today, but not these.’ | ||||||

| b. | Class C(2) | |||||

| AT: | *Không thể có chuyện những cuốn sách đó thì John sẽ đọc trước cuối tuần. | |||||

| NEG fact ASR story PL CLS book DEM2 TOP John FUT read before end week. | ||||||

| ‘*It’s impossible that those books, John will read by the end of the week.’ | ||||||

| CT: | Không thể có chuyện những cuốn sách đó thì John đọc, | |||||

| NEG fact ASR story PL CLS book DEM2 TOP John FUT read, | ||||||

| không | phải | những cuốn này. | ||||

| NOT | correct | PL CLS DEM1 | ||||

| ‘It’s impossible that those books, John read, but not these.’ | ||||||

| (45) | a. | Class D (1) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| AT: | *Mary bực tức | rằng | những | cuốn sách đó | thì | John đọc | |||||||||||||||||

| Mary resent | COMP. | PL | CLF book DEM2 | TOP | John read | ||||||||||||||||||

| trong | kỳ nghỉ. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| in | vacation | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| *‘Mary resents that those books, John read while on vacation.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CT: | Mary bực tức | rằng | những | cuốn sách đó | thì | John đọc, | |||||||||||||||||

| Mary resent | COMP | PL | CLF book DEM2 | TOP | John read, | ||||||||||||||||||

| không | phải | những cuốn này. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| NEG | correct | PL CLS DEM1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| *‘Mary resents that those books, John read, but not these.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Class D (2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| AT: | ?Tôi | tiếc | rằng | những | cuốn sách đó | thì | John đọc | ||||||||||||||||

| I | regret | COMP | PL | CLS book DEM2 | TOP | John read, | |||||||||||||||||

| mà | không | tham.khảo | ý.kiến tôi. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CONJ | NEG | consult | opinion I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ?*‘I regret that those books, John read without consulting me.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CT: | Tôi | tiếc | rằng | những | cuốn sách đó | thì | John đọc, | ||||||||||||||||

| I | regret | COMP | PL | CLF book DEM2 | TOP | John read, | |||||||||||||||||

| không | phải | những cuốn này. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| NEG | correct | PL CLS DEM1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ?*‘I regret that those books, John read, but not these.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (46) | |

| |

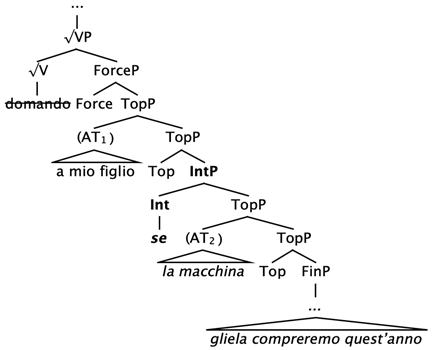

| (47) | a. | Mi domando, a mio figlio, se, la macchina, gliela compreremo quest’anno. |

| ‘I wonder, to my son, if, the car, we will buy it to him this year’ | ||

| (Rizzi & Bocci, 2017: [9]) | ||

| b. | ||

| ||

| (48) | a. | *Mary nói | [AT1 những cuốn sách đó ] | thì | là | cô ấy | sẽ | đọc | trong |

| Mary say | PL CLF book DEM2 | TOP | INT | PRN | FUT | read | in | ||

| hôm nay. | |||||||||

| today | |||||||||

| ‘Mary says that those books, she’ll read by the end of the day.’ | |||||||||

| b. | *Mary nói | rằng | [AT1 những cuốn sách đó ] | thì | là | cô ấy | sẽ | đọc… | |

| Mary say | C | PL CLF book DEM2 | TOP | INT | PRN | FUT | read… | ||

| (as a) | |||||||||

| c. | Mary nói | rằng | là | [AT2 những cuốn sách đó ] | thì | cô ấy | sẽ | đọc… | |

| Mary say | C | INT | PL CLF book DEM2 | TOP | PRN | FUT | read… | ||

| (as a) | |||||||||

| (49) | AT in lower TopP only (cf. 40a): |

| |

| (50) | a. | “không | phải | anh | thì.là | anh | khác…”48 | |||||

| NEG | right | PRN | CONJ-CONJ | you | different… | |||||||

| ‘If not you, then someone else…’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | “ừ, | thì.là | em | có nỗi | buồn | thật đẹp…” [song lyric]49 | ||||||

| well, | CONJ-CONJ | PRN | have | sadness | beautiful | |||||||

| ‘Well, then I (?you) have a beautiful sadness.’ | ||||||||||||

| (51) | a. | [Nó | không | học | toán] | thì | tốt. | |||||

| PRN | NEG | study | maths | ?? | nice | |||||||

| ‘It would be nice for him not to study mathematics.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | [Nó | không | học | toán] | là | tốt. | ||||||

| PRN | NEG | study | maths | ?? | nice | |||||||

| ‘It’s nice that he didn’t study mathematics.’ | ||||||||||||

| (52) | a. | [Nó | (*đã) | không | học | toán] | thì | tốt. | ||||||

| PRN | PAST | not | study | maths | TOP | nice | ||||||||

| ‘It’s (a) nice (thing) that he didn’t study mathematics.’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | [Nó | (đã) | không | học | toán] | là | tốt. | |||||||

| PRN | PAST | not | study | maths | CONJ | nice | ||||||||

| ‘It’s (a) nice (thing) that he didn’t study mathematics.’ | ||||||||||||||

| (53) | a. | (*rằng) họ | cười khúc khích] | làm | chúng em | thẹn. | ||||

| COMP PRN | laugh giggle | make | PL PRN | embarrassed | ||||||

| ‘[*(that) they giggled] embarrassed us.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | (*là) | cô ấy | rời đi sớm | làm | tôi | ngạc nhiên. | ||||

| CONJ | PRN.DEM | leave early | make | I | surprise | |||||

| ‘[*(that) she left early] surprised me.’ | ||||||||||

| (54) | |

|

2.2. Left Peripheral Adverbials

| (55) | a. | Cô ấy | quả thật | đã | nói | với | anh ấy. | |||||

| PRN.DEM | indeed | ANT | talk | with | PRN.DEM | |||||||

| ‘She indeed talked to him.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | ?Quả thật | cô ấy | đã | nói | với | anh ấy. | ||||||

| indeed | PRN.DEM | ANT | talk | with | PRN.DEM | |||||||

| ‘Indeed, she talked to him.’ | ||||||||||||

| (56) | a. | Cô ấy | thì | quả thật (pro) | đã | nói | với | anh ấy.] | ||||||

| PRN.DEM | TOP | indeed | ANT | talk | with | PRN.DEM | ||||||||

| ‘Speaking of her, she indeed talked to him.’ | ||||||||||||||

| b. | *Quả thật | [ cô.ấy | thì | [ (pro) | đã | nói | với | anh ấy ] ] | ||||||

| indeed | PRN | TOP | ANT | talk | with | PRN.DEM | ||||||||

| intended (a) | ||||||||||||||

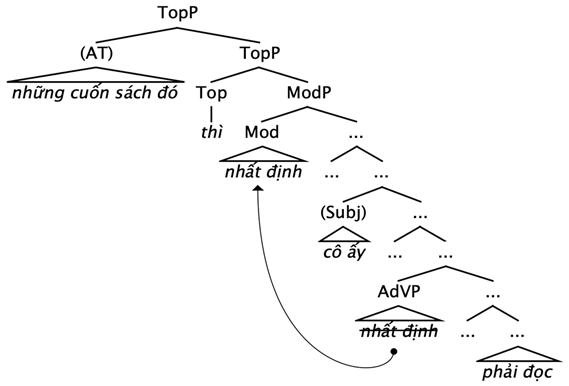

| (57) | a. | ?[Những | cuốn | sách | đó] | thì | nhất định | cô ấy | phẚi | đọc. | |||||||

| PL | CLF | book | DEM | TOP | absolutely | PRN.DEM | must | read | |||||||||

| ‘(?)That book absolutely she had to read.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | [Những | cuốn | sách | đó] | thì | cô ấy | nhất định | phẚi đọc. | |||||||||

| PL | CLF | book | DEM2 | TOP | PRN.DEM | absolutely | must read | ||||||||||

| ‘That book, she absolutely had to read.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| (58) | |

|

| (59) | a. | Rapidamente, Gianni trovò la soluzione. | |||||||||||

| ‘Rapidly, Gianni found the solution.’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | Giahái ha trovato rapidamente la soluzione. (Rizzi & Bocci, 2017: 15a) | ||||||||||||

| ‘Gianni found rapidly the solution.’ | |||||||||||||

| c. | *Cô ấy | đã | nói | quả thật | với | anh ấy. | |||||||

| PRN.DEM | ANT | talk | indeed | with | PRN.DEM | ||||||||

| ‘She indeed talked to him.’ | |||||||||||||

| d. | *Cô ấy | đã | nói | với | anh ấy | quả thật. | |||||||

| PRN.DEM | ANT | talk | with | PRN.DEM | indeed | ||||||||

| (as 58c). | |||||||||||||

2.3. “Quantifier-Raising”

| (60) | a. | Anh ấy | từ | nào | *(cũng) | nhớ. | [√S-OQP-cung-V order] | |||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | word | WH | OP | recall | ||||||||||||||

| ‘He remembers every word.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Cô ấy | ai | [*(cũng) | quen]. | ||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | WH | OP | know | |||||||||||||||

| ‘She knows everybody.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Anh ấy | bao giờ | [*(cũng) | đến | muộn].[√S-ADJNQP-cung-V order] | |||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | WH time | OP | come | late | ||||||||||||||

| ‘He is always late.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Tôi | ngày nào | [*(cũng) | tập thể thao] | ||||||||||||||

| I | day WH | OP | do exercise | |||||||||||||||

| ‘I do exercise every day.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| (61) | a. | Từ | nào | [anh.ấy | [cũng | nhớ].] | [√OQP-S-cung-V order] | |||||||||||||

| word | WH | PRN.DEM | OP | recall | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘He remembers every word.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Ai | [cô ấy | [cũng | quen]]. | ||||||||||||||||

| WH | PRN | OP | know | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘She knows everybody.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Bao | giờ | [anh ấy | [cũng | đến | muộn ]]. | [√ADJQP-S-cung-V order]] | |||||||||||||

| WH | time | PRN.DEM | OP | come | late | |||||||||||||||

| ‘He is always late.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Ngày | nào | [tôi | [cũng | tập thể thao ]]. | |||||||||||||||

| day | WH | I | OP | do exercises | ||||||||||||||||

| ‘I do exercises every day.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (62) | a. | *Anh ấy | [cũng | nhớ | từ | nào]. | [*S-cung-V OQP] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN DEM | OP | recall | word | WH | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘He remembers every word.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (ok: ‘Which word does he remember?’) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Anh ấy | [(cũng) | nhớ | mọi | từ]. | [√S-cung-V-OQP (mọi)] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN DEM | also | recall | each | word | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘He (also) remembers every word.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | *Anh ấy | mọi | từ | [(cũng) | nhớ]. | [*S-OQP-V: mọi] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN DEM | each | word | also | remember | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| *‘He every word remembers.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Tôi | [tập | thể thao | mỗi ngày]. | [√S-V-XQP: mỗi] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I | do | exercise | every day | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘I do my exercises every day.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| e. | ??Tôi | mỗi | ngày | [tập | thể thao]. | [??S-XQP-V: mỗi] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| I | every | day | do | exercise | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ??‘I every day do my exercises.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

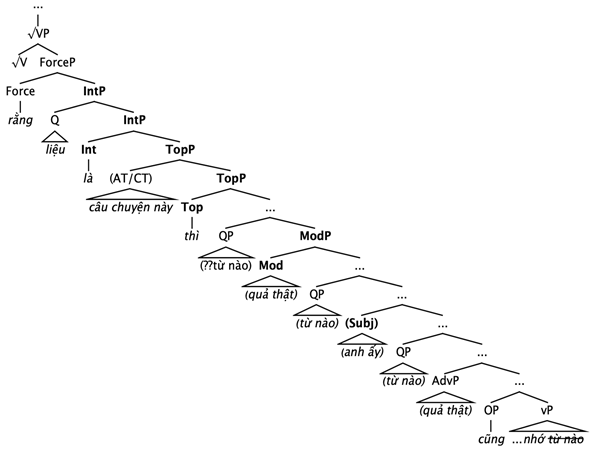

| (63) |  ∀ ∀ |

| (64) | a. | Câu chuyện | này | thì | từ | nào | anh ấy | cũng | nhớ. | |||||||||

| CLS story | DEM1 | TOP | word | WH | PRN.DEM2 | ALSO | remember | |||||||||||

| ‘As for this story, he remembers every word (of it).’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| b. | *Từ | nào | [câu chuyện | này | thì | anh ấy | cũng | nhớ.] | ||||||||||

| word | WH | CLS story | DEM1 | TOP | PRN.DEM2 | ALSO | remember | |||||||||||

| ‘As for this story, he remembers every word (of it).’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| c. | “Câu chuyện này? | Anh ấy | thì | từ | nào | cũng | nhớ.” | |||||||||||

| CLS story DEM1 | PRN.DEM2 | TOP | word | WH | ALSO | remember | ||||||||||||

| ‘This story? He’s the one that remembers every word (of it).’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Câu chuyện | này | thì | anh ấy | từ | nào | cũng | nhớ. | ||||||||||

| CLS story | DEM1 | TOP | PRN.DEM2 | word | WH | ALSO | recall | |||||||||||

| ‘As for this story, he remembers every word (of it).’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| (65) | a. | ??[AT | Câu chuyện này] | thì | từ | nào | quả thật | anh ấy | cũng | nhớ. | |||||||

| CLF story DEM1 | TOP | word | WH | indeed | PRN.DEM | ALSO | recall | ||||||||||

| ‘As for this story, he remembers every word (of it).’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | [AT | Câu chuyện này] | thì | quả thật | từ | nào | anh ấy | cũng | nhớ. | ||||||||

| CLF story DEM1 | TOP | indeed | word | WH | PRN.DEM2 | ALSO | recall | ||||||||||

| ‘As for this story, he remembers every word (of it).’ | |||||||||||||||||

2.4. Where(fore) Why?

2.4.1. English Why

| (66) | a. | Why (not) [risk it]? |

| b. | Why (not) [talk to a therapist]? | |

| c. | Why [ fix the car]? | |

| d. | Why [ him]? Why [ not her]? | |

| e. | Why [only yesterday]? Why not [ two weeks ago]? | |

| f. | Why [with his brother]? Why not [with his partner]?59 |

| (67) | a. | *Why (not) he/him go there? |

| b. | *Why she/her take the money? | |

| c. | *Why (not) they/them came? |

| (68) | a. | *When/*who (not) [risk it]? |

| b. | *When (not) talk to a therapist? | |

| c. | *How fix the car? | |

| d. | *Where him? Where not her? | |

| e. | *Who only yesterday? *Who not two weeks ago? | |

| f. | *Where with his brother? *How not with his partner? |

| (69) | a. | *She wondered [why her]. cf. (“Why her?,” she wondered) |

| b. | *She knew [why with his brother]. | |

| c. | She said: “Why not risk it?” |

| (70) | a. | She knew what/when/how/*why to tell him. |

| b. | She wondered who to talk to/how best to talk to him/*why to stay any longer. |

| (71) | a. | She knew what/when/how/why she should tell him. |

| b. | She wondered who to talk to/how best she should talk to him/why she should stay any longer. |

| (72) | a. | He was told where [ to meet Jane], and when…*but not why [ |

| b. | He was told where [ he should meet Jane], and when… but not why [ |

| (73) | a. | She knew [ what/why [ it was best/tough [ to tell him ]]] |

| b. | He wondered [ who [ it might be easier [ to live with: Jane or Amy? ]]] | |

| c. | He wondered [ why [ it might be easier [ to live with Jane. ]]] |

| (74) | a. | When/How did Justin say (that) he had finished the painting? |

| b. | Why did Justin say he had finished the painting early? | |

| c. | ??Why did Justin say that he had finished the painting early? | |

| d. | Where did Justin say that he had put the painting? |

| (75) | a. | She told you [ why *(not) to write about this problem] |

| b. | She told you [ why *(on no account) to write about this problem]. |

| (76) | a. | Lee forgot which dishes Leslie had said that *(under normal circumstances) should be put on the table. |

| b. | Which kinds of drugs did you say that *(without proper testing) had been released on the market? |

| (77) | a. | *She wondered [who to tell Mary the news]. |

| b. | She wondered [who had told Mary the news]. | |

| c. | She wondered [who (PRO) to tell the news to]. |

| (78) | Infinitival clauses are spliced at WhP: | (Shlonsky & Soare, 2011: [11]) |

| (79) | a. | *She asked me why to resign. | |

| b. | Why did you ask her to resign? | (Shlonsky & Soare 2011: [12]) | |

| |||

| (11) | Italian | |

| A Gianni, perché, la macchina, gliela volete regalare? | ||

| ‘To Gianni, why, the car, you want to give it to him? |

| (12) | Perché LA MACCHINA/∗LA MACCHINA perché gli volete regalare, | |||

| e non la moto? | ||||

| ‘Why THE CAR/∗THE CAR why you want to give to him, | ||||

| and not the motorbike?’ | ||||

| (13) | Perché, a Gianni, LA MACCHINA gli volete regalare, e non la moto? | |

| ‘Why, to Gianni THE CAR you want to give to him, and not the motorbike?’ |

| (14) | [Force [Top∗ [Int [Top∗ [Foc [Top∗ [Fin [IP …]]]]]]]] ‘ |

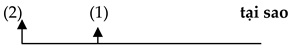

2.4.2. Vietnamese Why

| (80) | |

|

| (81) | a. | Tại sao | người ta | không | trồng | nấm | trên | đất…?62 | |||||||||||

| why | people | NEG | grow | mushrooms | in | soil | |||||||||||||

| ‘Why do people not grow mushrooms in soil…?’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| b. | *Người ta | tại sao | không | trồng | nấm | trên | đất…? | ||||||||||||

| people | why | NEG | grow | mushrooms | in | soil | |||||||||||||

| ‘Why do people not grow mushrooms in soil…?’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| c. | *Người ta | không | trồng | nấm | trên | đất | tại sao? | ||||||||||||

| people | NEG | grow | mushrooms | in | soil | why | |||||||||||||

| ‘Why do people not grow mushrooms in soil…?’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| (82) | a. | Anh | đã | nhiều lần | hỏi em | [rằng | [tại sao … ]] | [song lyric] | |||||||||||

| PRN | ANT | many times | ask PRN | C | why | ||||||||||||||

| ‘I have asked you why, so many times.’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Có nhiều | bạn hỏi | [ rằng | [tại sao | thầy | lại quay | được | các | Video TiếngHàn]]63 | ||||||||||

| ASR many | friends ask | C | why | teacher | upload | CAN | CLF | video lge. Korean | |||||||||||

| ‘I have many friends ask why my teacher can make Korean videos…’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| c. | [DP | câu hỏi | [rằng | [tại sao | bỗng nhiên | thế giới | lại | có thang máy]]]64 | |||||||||||

| CLF ask | C | why | suddenly | world | again | have elevator | |||||||||||||

| ‘…the question as to why the world suddenly has elevators…’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| (83) | ForceP … IntP > TopP > WhP > ReasonP > … FinP (Shlonsky & Soare, 2011: [35]) |

| |

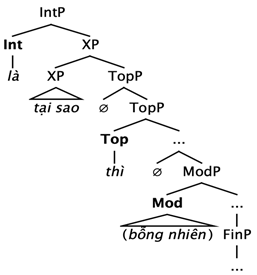

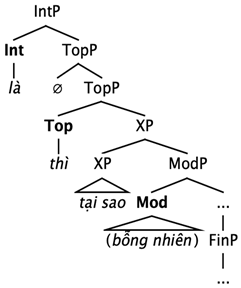

| (84) | a. | Cô ấy | không biết | (rằng) | là | [tại sao [ | anh ấy | nhớ | mọi | từ ]] | ||||||||||||||||

| PRN | NEG know | C | INT | why | PRN | recall | every | word | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know why he remembers every word.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | *Cô ấy | không biết | (rằng) | tại sao | [ là | [ anh ấy | nhớ | mọi | từ ]] | |||||||||||||||||

| PRN | NEG know | C | why | INT. | PRN | recall | every | word | ||||||||||||||||||

| (as a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | *Cô ấy | không | biết | (rằng) | là | [anh ấy | tại sao | nhớ | mọi | từ] | ||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG | know | C | INT | PRN.DEM | why | recall | every | word | |||||||||||||||||

| (as a)67 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | *Cô ấy | không biết | (rằng) | là | [ anh ấy | nhớ | mọi | từ ] | tại sao. | |||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG know | C | INT | PRN.DEM | recall | every | word | why | ||||||||||||||||||

| (as a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

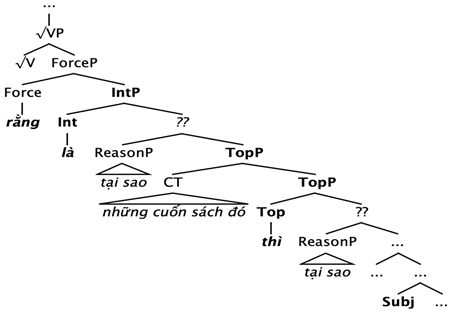

| (85) | a. |

| |

| b. | |

| |

| (86) | Cô ấy không biết… | |||||||||

| a. | …tại sao | [những | cuốn sách đó] | thì cô ấy có thể đọc, | ||||||

| why | PL | CLF book DEM2 | TOP PRN possible read, | |||||||

| không | phải | những cuốn này. | ||||||||

| NEG | correct | CLF DEM1 | ||||||||

| ‘I don’t know why he was able to read those books, but not these ones.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | …?[những cuốn sách đó] | thì tại sao cô ấy có thể đọc, | ||||||||

| PL CLF book DEM2 | TOP why PRN.DEM possible read, | |||||||||

| hông | phải | những cuốn này. | ||||||||

| EG | correct | CLF DEM1 | ||||||||

| (as a.) | ||||||||||

| (87) | |

|

| (88) | ForceP … IntP > TopP > ModP > WhP > ReasonP > … FinP (Shlonsky & Soare, 2011: [35]) |

| |

| (89) | *Mary hỏi rằng… | |||||||||||||||||||

| a. | …*[những | cuốn sách đó] | thì | nhất định | tại sao | [cô ấy | phẚi | đọc] | ||||||||||||

| PL | CLF book DEM2 | TOP | absolutely | why | PRN | must | read | |||||||||||||

| ‘Mary asked why that book she absolutely had to read.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | …?[những | cuốn sách đó] | thì | tại sao | nhất định | [cô ấy | phẚi | đọc] | ||||||||||||

| PL | CLF book DEM2 | TOP | why | absolutely | PRN | must | read | |||||||||||||

| (as a) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | …[những | cuốn sách đó] | thì | (tại sao) | [cô ấy nhất định phẚi đọc.] | |||||||||||||||

| PL | CLF book DEM2 | TOP | why | PRN absolutely must read | ||||||||||||||||

| (as a) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (90) | a. | *Cô ấy | không biết | [từ | nào | [ tại sao | [anh ấy | [ cũng | nhớ ]]] | |||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG know | word | WH | why | PRN.DEM | OP | recall | |||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know why he remembers every word.’. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | ?Cô ấy | không biết | [ tại sao | [ từ | nào | [anh ấy | [cũng | nhớ ]]] | ||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG know | why | word | WH | PRN.DEM | OP | recall | |||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know why he remembers every word.’. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Cô ấy | không biết | [ tại sao | [ anh ấy | từ | nào | [cũng | nhớ ]]] | ||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG know | why | PRN.DEM | word | WH | OP | recall | |||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know why he remembers every word.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (91) | ForceP > IntP > TopP > ReasonP > ModP > WhP > … FinP |

| (cf. Shlonsky & Soare, 2011: [35]) |

| (92) | a. | |

| b. |

| (93) | a. | Chị ấy | biết | chị | nên | nói | cái | gì. | |||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | know | PRN | should | say | CLF | what | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She knew what she should say.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Chị ấy | biết | chị | nên | đi đâu. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | know | PRN | should | go where | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She knew where she should go.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Chị ấy | không | biết | chị | nên | giải thích vấn đề | như thế nào. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG | know | PRN | should | explain problem | as how | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know how she should explain the problem.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | Chị ấy | tự hỏi | chị | nên | rời đi | khi nào. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | wonder | PRN | should | leave | when | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She wonders when she should leave.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| e. | Chị ấy | tự hỏi | tại sao | chị | nên | rời đi. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | wonder | why | PRN | should | leave | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘She wonders why she should leave.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (94) | a. | Chị ấy | biết | nói | cái | gì. | |||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | know | say | CLF | what | |||||||||||||

| ‘She knew what to say.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| b. | ?Chị ấy | biết | chị | nên | đi đâu. | ||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | know | PRN | should | go where | |||||||||||||

| ‘She knew where to go.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| c. | Chị ấy | không | biết | giải thích | vấn đề | như thế nào. | |||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | NEG | know | explain | problem | as how | ||||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know how to explain the problem.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| d. | ?Chị ấy | tự hỏi | rời đi | khi nào. | |||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | wonder | leave | when | ||||||||||||||

| ‘She wonders when to leave.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| e. | ?Chị ấy | tự hỏi | tại sao | rời đi. | |||||||||||||

| PRN.DEM | wonder | why | leave | ||||||||||||||

| ‘*She wonders why to leave.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| (95) | a. | Cậu Abdullah | đồng ý | dẫn tôi đi….và | chỉ cho tôi biết | đi đâu. | |||||||||

| PRN Abdullah | agree | take me go and | just let me know | go where | |||||||||||

| ‘Abdullah agreed to take me…and to let me to know where to go.’ | |||||||||||||||

| b. | Chị | không | biết | [ rời đi | lúc | nào ] | |||||||||

| PRN | NEG | know | leave | time | WH | ||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know when to leave.’ | |||||||||||||||

| c. | Chị | không | biết | [ khi | nào | [ rời đi ]] | |||||||||

| PRN | NEG | know | time | WH | leave | ||||||||||

| ‘She doesn’t know when to leave.’ | |||||||||||||||

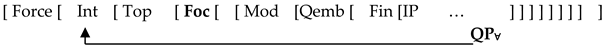

2.5. Summary

| (96) | ForceP > IntP > |

| (97) | ForceP > IntP > TopP > |

| (98) | ForceP > IntP > TopP > (ReasonP) > |

|

| (99) | ForceP > IntP > TopP > (ReasonP) > ModP > (WhP) > … Fin |

3. Conclusions (Nusquam Sunt Dracones)

- If, as seems to be the case for Vietnamese, the availability of constituent orders within the left periphery is determined more by semantic considerations—scope and scope evasion—than by the featural properties of dedicated positions, is this also true of other languages such as Italian, or are we dealing with a formal typological contrast? (Consider, for example, the difference between Contrastive and Aboutness Topics, the variable positioning”of a’verbs and weak indefinite (universal) QPs, the pre-/post-Topic positioning of tại sao: in each case, observed alternations are more consistent with functional-interpretive demands than with a fixed cartography);

- Vietnamese also challenges the idea of a sharp delineation between main and subordinate clauses. At least in some contexts what would be unambiguous subordinators in English and Italian have a much looser linking function; other constructions—passives, causatives, other serial verb structures—exhibit similar main~subordinate indeterminacies. Once again, this raises the question of whether such differences imply a typological contrast between hypotactic and paratactic languages (as suggested in Clark, 1992), or whether they simply urge a more flexible and nuanced view of functional categories;

- There also remain unanswered questions concerning the position of (non-topicalized) subjects. One specific issue is whether canonical subjects occupy a position within ‘IP’ or in the intermediate zone of the low left periphery; alternatively, whether the region conventionally labelled ‘IP’ may be more highly articulated, to include a lower FocP (cf. Belletti, 2004);

- More narrowly, a conceptual puzzle remains about the “*Why-to” constraint. Splicing of non-finite clauses (Shlonsky & Soare, 2011), Truncation (Hooper & Thompson, 1973), Exfoliation (Pesetsky, 2019/2021) typically operates to facilitate extraction and binding, thus increasing effability: in the case of why questions, however, splicing reduces effability. Whether considered from a formal or functional standpoint, this is a theoretical mystery. Why should this be, even in as permeable a language as Vietnamese?

- …Mais les vrais voyageurs sont ceux-là seuls qui partent

- Pour partir; coeurs légers, semblables aux ballons,

- De leur fatalité jamais ils ne s’écartent,

- Et, sans savoir pourquoi, disent toujours: Allons!

- …But real travellers are just those for whom departure

- Is its own reward; [who leave], hearts light as air

- Not to evade their fate/[but] always declaring

- – without knowing why—‘Let’s go!’

- Charles Baudelaire, Le Voyage [final stanza]

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANT | Anterior marker |

| ASR | Assertion Marker |

| C(OMP) | Complementizer |

| CLF | Noun Classifier |

| CONJ | Conjunction |

| COP | Copular/Linker |

| DEM | Demonstrative Marker |

| INF | Infinitive |

| LOC.COP | Locative copula |

| NEG | Negation Morpheme |

| NEGQ | Final Negation (interrogative brace) |

| OP | Scopal Operator |

| PAST | Past Tense |

| PL | Plural morpheme |

| PRN | Pronoun (Vietnamese equivalent) |

| PROG | Progressive |

| QP | Quantified Expression |

| QP∀ | Universal Quantifier |

| REL | Relativizer |

| SUBJNC | Subjunctive |

| TOP | Topic Marker |

| WH | Wh-expression |

| 1 | Beyond this footnote, I will largely ignore apparently ‘head-final’/left-branching languages, such as Japanese or Korean. For convenience, I will assume, following Kayne (1994), Sheehan et al. (2017), Roberts (2019), and others, that these are not simply the mirror-image of their right-branching counterparts (though cf. Saito (2015): rather, that SOV-I-C languages are underlyingly head-initial varieties, where ‘generalized roll-up’ has taken place (i.e., iterated phrasal movement to higher specifier positions). On that—very probably erroneous—view, the left periphery is a universal domain, appearances to the contrary notwithstanding. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Clearly, this phrase-structural notion of peripheral is at least partially separate from the “core” vs. “periphery” distinction, in discussions of the shape of internally represented grammars (“I-language”, “narrow syntax” etc.); see Chomsky (1981, 1985, 2000); cf. Hyams (1986), Deprez and Pierce (1993); Culicover (1999), Moltmann (2020). And CP is obviously crucial to Phase Theory: see Citko (2014). However, the CP of Phase Theory is usually treated as an undifferentiated single layer of structure, an escape hatch for movement: almost all the theoretical action takes place further down, in TP or below. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Lasnik and Uriagareka (2022, p. 66) observe that Chomsky (1973) reverses the standard order of S and S’ (S’ → Comp S, Bresnan, 1970) such that the initial symbol S dominates Comp (“S → Comp S’”); in other words, root clauses start at (what would now be labelled) CP. However, this revision was quickly abandoned in Chomsky (1977): from Chomsky (1981) onwards, CP re-assumes its ‘no-man’s land’ status. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Emonds (1969, p. 6) offers a more qualified definition of root that permits nodes above S: “A root will mean either the highest S in a tree, an S immediately dominated by the highest S or the reported S in indirect discourse…” This definition is further elaborated in Emonds (2004). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | The non-peripheral treatment of NegP is likely due to its clause-medial position in the surface syntax of English. If the original object language of generative theory had been Modern Irish, or Chamorro, rather than English (though cf. McCawley, 1970; Emonds, 1980), Negation might well have been treated as peripheral. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | An additional analytic question is whether external Merger is ‘integrated’–extending the clausal spine–or appended, creating an adjunction structure (cf. ‘Chomsky-adjunction’), within analyses where this distinction is a theoretical option. With respect to child language acquisition (see de Villiers, 1991, below), for example, the evidence suggests that why is initially adjoined to bare propositions, and only later integrated into the clausal spine. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | On one hand, high level, meta-questions (‘Beyond explanatory adequacy’) are answered by “because Merge” or “because Strong Uniformity” or even “just because innateness…”, answers that are unsatisfactory when it comes to capturing micro-parametric, or typological variation. At the other extreme, low level, mini questions as to why a particular element is moved to a particular node in a given context are typically answered with reference to some attracting, proprietary formal feature (though cf. Roberts’s (2019) “^” feature), Rizzi’s (2014) Subject Criterion: see below. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Until recently, no ‘mainstream’, Merge-based approach attempted to explain why a language could not start the derivation with T or C, rather than merging these functional categories later, as invariably happens. To be sure, there are consistently left-branching languages where the CP-domain is realized on the right periphery, but there are, to my knowledge, none where lexical categories dominate the corresponding non-propositional functional nodes. In principle, this should be possible: it merely involves reversal of items bearing probe and goal features. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Additional questions arise concerning the ordering of adjunct modifiers both relative to lexical heads—where they typically display similar cross-categorial harmony effects to those found with arguments, but where head-complement parameter explanations cannot apply (Travis, 1984; cf. Hawkins, 2001)—also relative to one another, where semantic factors evidently play a role (Cinque, 1994, 1999; Sproat & Shih, 1991; Teodorescu, 2006; Endo et al., 2016). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | It is telling, I think, that there are no departments of cartography in research universities: geographers, historians, archaeologists, economists, social scientists of all types rely on cartography furnished by government workers (UK Ordnance Survey, US Geological Survey, for instance). Cartography is only ever the beginning of the story: no matter how accurate or detailed it may be, a good map offers no deeper explanation in the absence of a prior physical, social, or economic theory. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Increasingly, Rizzi has become concerned with why questions: indeed, he devotes a full section of his 2017 paper to the issue. However, the proposal given there is explicitly circular: “A functional sequence may be taken as an explanans;…[…] Reciprocally, a functional sequences should be looked at as an explanandum, a complex set of properties which in and of itself is in need of a further and deeper explanation.” In his discussion of functional sequences as explananda, Rizzi then reiterates the two kinds of principles listed above. Such argumentation may be satisfactory to some readers. This is not to say that cartography has no explanatory value. On the contrary, it has tremendous value as a heuristic, within a deductive theory of grammar. However, this does not mean that “the functional sequence” is an explanans since, absent a deeper explanation, we are no closer to removal of “puzzlement” (the criterion of explanation proposed by Bach, 1974, p. 154). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Rizzi (2017) implies that Cinque and Rizzi (2015) is the original source of these speculations (“As pointed out in Cinque and Rizzi (2010 [sic]…”): however, from my reading, that position paper is exclusively concerned with where, what and how questions: the question why does not feature in that article at any point. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | There is, of course, a way to make selection ‘non-special’, namely, by assuming that even root clauses contain illocutionary features within an expanded left periphery. This move, which could be correct, does no more to solve the broader why question; since there is no reason in principle why Force features could not be merged early (in an autonomous syntactic theory). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Related to these questions, it should be asked whether conventional labels used to categorize elements SAE languages {conjunction, complementizer, relative pronoun, topicalizer…} are useful or distracting when it comes to describing pre-subject functional categories (see, for example, Clark, 1992)? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | A reviewer points out that Vietnamese is probably not unique in this regard: they point to evidence of complementizer variation, and embedded topicalization in other MSEA varieties such as Thai, Lao and Burmese, also to clause-initial interrogative particles in main clauses in Khmer. It seems plausible, therefore, that further research will uncover left periphery structures in other varieties as intricate as those documented here. Time and space constraints preclude consideration of mà in this article. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Time and space constraints preclude consideration of mà in this article. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | In both cases, I will adopt a base-generation (with co-indexation) analysis here, though nothing hangs on this: here, I am simply concerned to establish surface positions within the functional sequence. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Elle magazine (VN edition, 17 February 2024). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | The full citation reads: “Murakami Haruki nói rằng: “Tôi cho bạn biết tôi thích bạn không hẳn là muốn ở cạnh bạn, chỉ là mong rằng sau này khi bạn gặp thăng trầm của cuộc đời thì đừng nản chí, bởi ít nhất đã có một người từng bị sức hút của bạn hấp dẫn. Trước đây như thế, về sau cũng vậy.” (“Murakami Haruki said: “I tell you that I like you, not necessarily because I want to be with you, but because I hope that when you encounter ups and downs in life, you will not be discouraged, because at least one person has been attracted to you. It was like that before, and it will be like that in the future.”) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | See the examples in (35)–(36) below, discussed in relation to embedded topicalization (ET). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | We shall see directly that this is untenable: in contrast to what appears to be in Italian, Vietnamese does not allow the recursive higher topic position between Force and Int. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | As we shall see directly, là can appear adjacent to adjectival predicates, just not in its copular function. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | https://vn.wa-tera.com/to-iimasu/. In non-reporting contexts, nói là typically has a less quotative meaning than nói rằng: that is to say, nói là is ‘say’ in the sense of “mean, imply, suggest” compare English: “What does it say when he turns up especially early?” By contrast, rằng is more typically associated with mental states and embedded propositions. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | “Bạn có thể nói rằng là mình ổn, nhưng ánh mắt bạn lại không biết nói dối..” (‘You can say that you are fine, but your eyes don’t know how to lie’). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | Another clear difference between liệu and conjunction là is that liệu can appear in utterance-initial position, as in (7) above: this is impossible for là, which never occurs sentence-initially. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | Notice that the contrast between (21c) and (22c) is not quite minimal: whereas liệu introduces a standard Y-N question having the same form as a matrix question [ tôi có đang vui vẻ tại bữa tiệc không] ‘Am I having fun at the party?’, with interrogative embraciation, là prefers to express the same idea using alternative statements, i.e. without interrogative có, followed by hay không. This is consistent with the idea that là, like English like, lies intermediate between direct and indirect subordination—”direct-reported” see (20a) above. This clearly requires closer investigation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | Notice that in the unraised cases, the copular form of là is required before nominal predicates (23a), (23b). This copula must be deleted in the raised alternants (24a), (24b). Though this might be explained as a case of haplology, there seems to be something more going on, since other multifunctional items—aspectual vs. preterite đã, for example—are also only able to appear once per clause. Also, even when a constituent intervenes, as in (23a)/(23b), there is a preference to drop one of the two làs; in such cases, though, it is the conjunction, rather than the copula, that must be dropped: Có phải (?là) cái chết là chấm hết? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31 | (19c) https://tatoeba-org.translate.goog/en/sentences/show/9013946?_x_tr_sl=vi&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc (20a) https://spiderum.com/bai-dang/Dan-ong-co-nen-la-tru-cot-gia-dinh-hteaGrzfEuOL; (20d) https://hanoilanguage.vn/how-to-use-hinh-nhu-chac-la-seem-in-vietnamese/, all accessed on 30 September 2024. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | I am very grateful to Guglielmo Cinque for correcting my errors concerning sembrare in an earlier draft. Ironically, the Vietnamese translation equivalent of Italian sembrare~seem—namely, hình như—does not allow raising. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | Matters are further complicated by the fact that {rằng…là..liệu} sequences are also acceptable if there is a prosodic break between {rằng…là} and {liệu}: I will assume that this anomaly can be explained in terms of performance: cf. English “that..that” restarts. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | The tree in (29) anticipates the discussion of embedded topicalization in the next section, where it will be shown that Vietnamese differs from Italian in not allowing topicalization above Int. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35 | I am grateful to Trang Phan for drawing my attention to Nguyen’s (2021) dissertation. Using the pragmatic-functional framework proposed in Fraser (2009), Nguyen treats all these instances as discourse-markers of various kinds (Elaborative, Logical, Contrastive DMs). Her conclusions are broadly in line with Clark (1992): “The claim is made here that thì has a general discourse-related topicalizing function, explicitly marking background for the main proposition which the speaker wishes to communicate, and that it is this explicit marking allowing for 'immediate' communication that makes this conjunction so popular. A subsidiary claim is that such a function is an inchoative one, that conjunctions such as thì introduce inchoative predications: Given X, then predicate Y as coming about (Clark, 1992: abstract).” It is not clear how either of these approaches should capture the constraints on clause-internal interactions detailed below. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36 | As presented here, this is a pure stipulation. However, Miyagawa offers a semantic explanation of the restriction: “the complement of C and D predicates is “subjunctive” and contains a Focus Operator that induces a semantics of alternatives, the predicates…must select the focus operator directly to function properly. If TopP is projected […] this blocks selection…(Miyagawa, 2017, p. 25)”. In this way, the restriction is explained by selection, as Rizzi suggests (see earlier discussion). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37 | In fact, Miyagawa proposes four language types, predicted by Strong Uniformity, according to which one of two sets of features {δ = topic, focus; ϕ = agreement} located in C may be inherited by T (or both, or neither). In an Agreement-based language (such as English), only phi features are inherited by T: in a discourse-configurational language (such as Japanese), it is the δ features that are inherited, triggering obligatory topic movement in the narrow syntax. Strong Uniformity predicts two further language types: Class III, where both features are inherited by T (Spanish is the discussed example); and Class IV, where both features remain in C (e.g., Dinka). Only the first two types are relevant to the present discussion. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38 | In (40–42), I directly copy the glosses given by Miyagawa, which imply more structural parallelism than may be warranted. It is hard to ignore [the fact (!)] that koto functions like a nominalizing head—hence, the following ACC marker, which otherwise only attaches to nominal arguments. If this were the correct gloss, the impossibility of ET in D/E classes would be due to a simpler explanation, viz., that Topicalization is impossible inside complex noun phrases. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39 | It is noteworthy that Miyagawa translates the Japanese sentences in (40) and (41)—even the grammatically acceptable cases—as Left Dislocation (LD) structures, rather than ET. No reason is provided for this shift. It is also unclear why the subject is changed in examples (41a) and (41b) (Miyagawa’s examples [44] and [45]). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | Japanese also allows object scrambling without a topic marker, what Miyagawa terms ‘familiar topics’ (FT); these display a different judgment pattern. This seems to be possible in Vietnamese also; however, space constraints preclude further discussion here. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 41 | Notice that in the examples Miyagawa gives the contrast argument is not made explicit. Rather the claim seems to be that the string is only acceptable if the -WA argument, with contrastive focus, is interpreted as a Contrastive Topic. (In our Vietnamese examples, explicit alternatives are presented). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 42 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43 | There are two other points to observe here. First—which will be important later when we consider embedded why-questions—is the fact that the negative ellipsis in the CT examples seems to require more structure than in English: the direct translation of “not these” → “*không cuốn này” is unacceptable—nominal ellipsis “cuốn sách này” is possible, but NEG cannot attach to a bare DP). Second, note the use of the ‘relative pronoun’ mà as a simple conjunction, in (37b): this illustrates the fact that mà, like thì, can lexicalize several different positions. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44 | At least on first inspection: when we come to tai sao, we shall see that although Vietnamese patterns with Japanese with respect to the availability of ATs vs. CTs with [C, D] predicates, the data do not support the idea that CTs are projected to a distinct, lower, Foc position (contra Rizzi & Bocci): on the contrary Contrastive Topics occupy the same unique position as ATs; see below. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | There is indirect evidence that the opposite may be true of Japanese: i.e., only the topmost Top position is available in this language. This is suggested by contrasts between Vietnamese and Japanese L2 learners of English, faced with instances of embedded Foc movement in English wh-questions “Who under no circumstances should you talk to” vs. “*Under no circumstances who should you talk to”—Vietnamese speakers replicated NS judgments, whereas Japanese learners strongly preferred the grammatically unacceptable option). See Duffield and Matsuo (2019). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46 | One question left unaddressed in this investigation is whether there is a difference between ‘moved’ vs. ‘non-moved’ topics, where the former are directly linked to lower argument positions. A reviewer points to work by Liao and Kao (2023), which compares topicalization structures in Italian, English and Chinese, and which finds just such a difference, ‘moved’ topics being unique in their clause. Whilst further tests are required for a conclusive answer about the Vietnamese, the data collected so far indicate that non-moved topics are no less restricted than their moved counterparts. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 47 | Data searches are further complicated by the fact that the string thì…là is homographic with the compound noun (cây) thì là (= the herb known as dill, in English). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 48 | The whole citation is interesting and relevant. “không phải anh thì là anh khác, tình là rác cớ sao phải buồn….| #shorts” | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 49 | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-A9PW_X7kJs (accessed 5 October 2024). At least, this example distinguishes là from rằng: the latter element would not be possible in this context. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | A way around this would be to suppose that (51b) involves a nominal predicate with a covert nominal head (perhaps điều: [điều tốt]), as in (i); the objection is that the overt version does not seem entirely natural:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 51 | This structure also reveals a contrast between pre-verbal tense/aspect morphemes, which are restricted to finite clauses, vs. post-verbal functional categories such as VP-final abilitative được, which may appear in topic position:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 52 | This tree only indicates possible movement of the adverb: I deliberately ignore all other likely displacements, especially of the subject, and—possibly—of the object topic as well as the issue of possible co-indexation. With respect to the subject position, a reviewer suggests examining the distribution of “Scope Bearing” subjects, such as ‘nobody’, ‘few people’ ‘at most two people’: at least in Chinese, these elements cannot undergo topicalization, in contrast to regular thematic subjects; see Ko (2005). Whilst closer examination of the Vietnamese equivalents of such items is obviously worthy of investigation, it is unclear how this would change the picture here, given the contrast between the marginal (57a) and the acceptable example (57b), which crucially does not involve subject topicalization. That said, such an inquiry might well shed some light on the architecture of the lowest levels of the left periphery. Unfortunately, time and space constraints prevent elaboration here. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 53 | The scare quotes around the section title indicates that we are not dealing here with true universal quantifiers here, but rather with underspecified, ‘multifunctional’ items that vary in their interpretation according to their scopal relationship to particular semantic operators: these elements might be better, if less felicitously, translated as (free choice) ‘any’, rather than ‘every’. I am grateful to Nikolas Gisborne for drawing my attention to this point. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 54 | Alternatively, as negative polarity items (NPI), whenever they appear in the scope of negation. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 55 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 56 | A reviewer suggests a semantic explanation for the marginality of (64b): “…where a larger whole is introduced as an Aboutness Topic (AT), followed by a reference to a smaller part of that whole. If reversed, such an order may violate the expected part-whole discourse relation, leading to an unnatural interpretation”. If this explanation were correct, then we might expect such orders would be acceptable if the AT were unrelated to the moved QP, that is, if the AT were the subject, as in (i) below. To the best of my knowledge, however, that sentence is, if anything, even less acceptable than (64b) above (cf. 64c):

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 57 | Were it not for the facts in (65), we could account for (64d), by supposing that even non-topicalized subjects raise to a higher SUBJ position, outside of FinP. This would be consistent with ideas presented in Rizzi (2017). It should be clear, though, that any such claim, which could be independently true, requires much more extensive empirical investigation, beyond the scope of this paper. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 58 | These cases should be distinguished from cases of Aux-deletion in informal speech, which are only acceptable where an inverted auxiliary would appear in a formal register (√”What you doing?” “Where you going?” “Why you telling me this”, vs. *Where you go”, “*What you did?”, “Who you talk/*talked to?”) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 59 | How come diverges not just from why in these contexts, but also from other wh-expressions, in requiring a full and finite complement, though it does marginally allow embedding. Space constraints preclude further discussion. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60 | Notice that whereas the object arguments must be construed with the lowest clause—given the selectional properties of best, easy, etc.—why, like other adjuncts, can only be construed with the immediately adjacent predicate: i.e., why-best/tough, not *why-tell; why-easier, not *why-live with. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 61 | Shlonsky and Soare (2011) refer to discussion in Cattell (1978) and Ko (2005, pp. 898–899.n31), citing David Pesetsky, pers. comm.). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 62 | https://vietjack.com/khoa-hoc-tu-nhien-6-ct/tai-sao-nguoi-ta-khong-trong-nam-tren-dat-ma-phai.jsp, accessed on 5 October 2024. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 63 | https://www.instagram.com/ha_manh_trung/p/C9lzXkDyD7o/?img_index=1, accessed on 5 October 2024. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 64 | https://tapchithangmay.vn/tai-sao-thang-may-ra-doi/, accessed on 5 October 2024. Note that this sentence provides additional evidence of the availability of {C-tại sao-ADVP-subject} order. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65 | In fact, this question can be expanded further, applying to all constituent order. In Duffield (2022, 2024), I propose a semantically-driven theory of word-order involving the principle of Supervenience: constituents—including functional categories and adjunct modifiers—are invariably placed in the minimal syntactic domain to allow unique scope over the elements with which they are interpreted. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||