Abstract

Historically, the field of discourse marker research has moved from relying on intuition to more and more ecological data, with written, spoken, and now multimodal corpora available to study these pervasive pragmatic devices. For some topics, video is necessary to capture the complexity of interactive phenomena, such as feedback in dialogue. Feedback is the process of communicating engagement, alignment, and affiliation (or lack thereof) to the other speaker, and has attracted a lot of attention recently, from fields such as psycholinguistics, conversation analysis, or second language acquisition. Feedback can be expressed by a variety of verbal/vocal and visual/gestural devices, from questions to head nods and, crucially, discourse or pragmatic markers such as “okay, alright, yeah”. Verbal-vocal and visual-gestural forms often co-occur, which calls for more investigation of their combinations. In this study, we analyze multimodal pragmatic markers of feedback in a corpus of French dialogues, where all feedback devices have previously been categorized into either “alignment” (expression of mutual understanding) or “affiliation” (expression of shared stance). After describing the distribution and forms within each modality taken separately, we will focus on interesting multimodal combinations, such as [negative oui ‘yes’ + head tilt] or [mais oui ‘but yes’ + forward head move], thus showing how the visual modality can affect the semantics of verbal markers. In doing so, we will contribute to defining multimodal pragmatic markers, a status which has so far been restricted to verbal markers and manual gestures, at the expense of other devices in the visual modality.

1. Introduction

In the linguistic landscape, not all subfields make use of the same data. Interactional linguistics, for instance, made the multimodal transition a long time ago, following technological advances in Conversation Analysis, and now often relies on video data to analyze the dynamics of social interaction (e.g., Goodwin, 2010; Streeck, 2009; Mondada, 2016). These studies typically resort to qualitative methods applied to limited corpus resources, given the time and effort required to process this type of data, along with the fine granularity that such methods imply. With the relatively recent emergence of larger video corpora, as well as accessible tools and established frameworks for multimodal data analysis, we are now seeing a new type of study taking multidisciplinary inspiration from both Conversation Analysis and Corpus Linguistics. This allows for well-known interactive phenomena to be studied from a more quantitative perspective.

Feedback is one of these phenomena. A central function of dialogue, feedback corresponds to ‘listener responses’ (Bavelas et al., 2000) or ‘commentaries’ (Pickering & Garrod, 2021) addressed by one speaker to the other in order to help manage the interaction. More specifically, these interventions can indicate a temporary lack of understanding (I beg your pardon?), or, on the contrary, signal that both speakers are on the same track (mhm, I see) and/or in agreement (yes, alright). Feedback can also be used to display an affiliative stance through assessments (oh wow, amazing). As plenty of studies have shown, feedback is crucial in conversation as it helps both the listener (Schober & Clark, 1989) and the speaker (Healey et al., 2018). A related concept is that of alignment, which describes the (ideal) situation where both speakers share mental representations and are thus equipped to contribute efficiently and successfully to the interaction. Feedback markers thus help reach alignment between speakers by signaling that this shared knowledge is achieved—or not. Another concept in this constellation is affiliation, which is defined together with alignment as its affective counterpart (Stivers, 2008; Steensig, 2020), whereby listeners express their agreement, appreciation, and shared stance toward the speaker’s contributions. In this study, we consider feedback in relation to both alignment and affiliation.

Multimodality has always been central in the study of feedback, with early studies exploring the role of phenomena such as head nods (Dittmann & Llewellyn, 1968) or laughter (Sacks, 1974) in alignment and affiliation, thus going beyond mere verbal output. Listening and providing feedback indeed not only relies on verbal elements but also on facial expressions, gestures, and body language (Müller, 1996), making video corpora an invaluable resource in this endeavor.

Another relevant domain is that of pragmatic markers. Also called discourse markers (sometimes with a slightly different definition), pragmatic markers such as okay or you know have been studied in relation to feedback in studies such as Bangerter and Herbert (2003) or Fox Tree (1999), where they were posited to have an effect on alignment through flagging discourse structure and calling for the addressee’s attention. Pragmatic markers are indeed a functional category of linguistic elements that are used to facilitate the interpretation of the relations between utterances, between parts of discourse, and between speakers. As highly frequent and conventionalized expressions, they provide the ‘oil’ that makes conversation smoother and include discourse connectives (but, so, actually) together with hedging (sort of, like), turn-taking (well, I mean) and hesitation devices (uhm, you know), among many others (Hansen, 2006). From the perspective of feedback, they have mainly been analyzed in case studies or as small, pre-defined subsets of expressions, and currently lack a more comprehensive account.

The same observation goes for multimodal combinations of verbal-vocal and visual-gestural signals of feedback. The fact that the vocal and visual modalities often combine is not new and has given rise to the term multimodal gestalts (Mondada, 2014). These are patterns of linguistic and embodied resources that combine to jointly perform some communicative action, and they are typically studied with qualitative methods and/or in case studies (e.g., Inbar & Maschler, 2023). In what follows, we take a more quantitative and bottom-up approach to multimodal markers of feedback, starting from a recent previous study (Kosmala & Crible, in press) where we observed that most feedback sequences involve the visual modality and that verbal pragmatic markers are also prevalent in these sequences. In this paper, we, therefore, propose to further explore multimodal gestalts as pragmatic markers of feedback, describing their forms and functions. In doing so, we also want to contribute to the discussion of the boundaries of the category of pragmatic markers and whether or not multimodal elements can be included in it.

2. State of the Art

2.1. Feedback, Alignment, and Affiliation

Feedback is an umbrella term that covers the listener’s responses to the main speaker during an interaction, such as backchannelling (mhm, okay, nodding), evaluations (wow), or clarification requests (what?). There are several typologies of listener responses, such as Gardner’s (2001), who distinguishes between subfunctions of feedback (continuers, acknowledgments, newsmarkers, change-of-activity). Several models acknowledge the multimodal nature of feedback and include visual-gestural forms such as facial expressions and gestures, which often align with verbal-vocal markers (Müller, 1996; Ferré & Renaudier, 2017; Boudin, 2022; Rasenberg, 2023).

It has repeatedly been documented that feedback has multiple functions (see Deng, 2009 for a review); however, the connection with alignment and affiliation has not been systematic in previous research (exceptions are Stivers, 2008; Barth-Weingarten, 2011, or Müller, 1996). This could be due to a disciplinary divide, where affiliation is more studied in Conversation Analytical studies, while alignment is also a favored topic of psycholinguistic research. In this latter area, authors have explored how the mental representations of speakers tend to align over time and what impact this mutual understanding has on the unfolding of dialogue. For instance, Pickering and Garrod’s (2004) interactive alignment model suggests that speakers and listeners prime each other by re-using the same phonetic, syntactic, and semantic structures, which, in turn, facilitates communication (see Rasenberg et al., 2020 for a similar model of mental and behavior alignment that also includes the visual modality). Their model mentions the role of feedback sequences, which they call ‘commentaries’, as expressions of this adjustment of mental representations. Pickering and Garrod (2021) distinguish between positive and negative commentaries depending on whether alignment is achieved or not. In the latter case, expansion (clarification, reformulation) is needed before the interaction can continue.

Another useful distinction is that by Bavelas et al. (2000), who analyzed the distribution of generic vs. specific listener responses during storytelling. The former can be re-used in different places and consists of interjections, pragmatic markers, laughter, or any element that is not lexically tied to the preceding context. Specific feedback, in turn, cannot be moved to a different place in the conversation as it contains propositional elements that are directly connected to the previous context. These different types of feedback (positive or negative, generic or specific) have been shown to be distributed differently throughout an interaction (Crible et al., 2024). In our recent study (Kosmala & Crible, in press), we further associated them with alignment and affiliation, showing, for instance, that affiliation tends to be more specific than alignment. Steensig (2020) also showed that alignment and affiliation can combine with opposite values. In doctor/patient interactions, for instance, one can align (nodding, showing understanding) without affiliating (not expressing empathy).

2.2. Verbal-Vocal Pragmatic Markers of Feedback

Within all verbal feedback devices, the present study focuses on pragmatic markers. We adopt this terminology (instead of discourse markers, for instance) to better match our multimodal scope and the nature of the phenomenon under scrutiny. In particular, the term pragmatic markers might be better suited to cover markers of agreement and interjections (e.g., ah oui ‘ah yes’), which are relevant to feedback and alignment. In doing so, we subscribe to Hansen’s (2006, p. 28) definition:

“Discourse marker should be considered a hyponym of pragmatic marker, the latter being a cover term for all those non-propositional functions which linguistic items may fulfil in discourse. Alongside discourse markers, whose main purpose is the maintenance of what I have called «transactional coherence», this overarching category of functions would include various forms of interactional markers, such as markers of politeness, turn-taking etc. whose aim is the maintenance of interactional coherence; performance markers, such as hesitation markers; and possibly others”.

With such a broad definition, pragmatic markers present the following characteristics: they are only loosely connected (or not connected at all) to a host unit, they have little or no propositional meaning, they are highly grammaticalized which implies a frequent use, fixed form, and conventional functions which often differ from the original semantics. These functions range from marking coherence relations and discourse structure to managing the interpersonal relationship between speakers (Crible, 2017). Typical examples in English include well, I mean, actually, okay or yeah, which are all polyfunctional and syntactically independent or optional.

A few studies have looked at pragmatic markers (or similar forms under different names) from the perspective of feedback and alignment. Chief among them, Bangerter and Herbert (2003) investigated a number of pragmatic markers (okay, all right, etc.) as “project navigators”, that is, devices that help manage transitions between joint activities (or “projects”) in dialogue. In their view, markers help speakers coordinate their understanding of where they are in a project. In the same line, Fox Tree (1999) conducted a production study where participants listened to monological and dialogical tangram descriptions. She found that the overhearer’s performance on matching tangrams was better in the dialogue condition, a finding which she relates to the higher frequency of pragmatic markers such as I mean and you know in dialogue than in monologue. These markers might make the structure of tangram descriptions clearer and thus help overhearers follow the recording. However, Branigan et al. (2011) later tested this hypothesis by manipulating the presence of pragmatic markers in recordings of a similar task and did not find that performance had improved.

In addition to these psycholinguistically oriented studies, pragmatic markers, primarily agreement markers within them, have also been related to feedback and alignment through the framework of Conversation Analysis. These are typically case studies that adopt a fine-grained view of the functions of a given marker, examining its prosody, position in the discourse, and relation to the context. For instance, Col et al. (2016) documented various syntactic and semantic uses of French voilà (‘right, that’s it’) and discussed in particular its confirmatory value, highlighting how voilà situates the utterance within a sequence of events or utterances by grouping information. Similarly, Kerbrat-Orecchioni (2016) focuses on oui (‘yes’) and its variants and distinguishes between different subtypes or degrees of agreement, such as “restricted” (e.g., yes but) or “pseudo” (ironic) agreement.

Beyond French, Couper-Kuhlen (2021) examined the combination oh okay in English conversation from a structural and prosodic viewpoint. She found that oh okay is used as a third-position token after a request for information and its answer, with a caesura between the two markers, thus forming two different turn-constructional units. By comparing isolated and combined uses of oh and okay, Couper-Kuhlen concludes that a prosodically “fused” version of the combination might indicate an ongoing process of grammaticalization whereby the two forms are morphing into a single “OOKAY” particle. Such subtleties in the specific uses of pragmatic markers are unlikely to transfer cross-linguistically. Delahaie and Solís García (2019), for instance, showed that French d’accord and Spanish vale have different values that do not exactly match those of okay, a finding which has an impact on learners’ pragmatic competence (Delahaie, 2009).

As is becoming apparent from the literature review above, many studies on alignment focus on individual agreement markers. Other authors have taken a more systemic approach to agreement markers, showing the division of labor within this group of expressions. Tobback and Lauwers (2016) worked on French- and Dutch-speaking political debates and showed that some markers of agreement (e.g., soit ‘right’, oui ‘yes’, en effet ‘indeed’, bien sûr ‘of course’, etc.) target the content of the speaker’s contribution, while others (mhm, d’accord ‘alright’, OK ‘okay’, voilà ‘right’) respond to the enunciation, that is, to the speech act itself and, thus, relate to what we presently call alignment. They further observed that agreement markers often combine with each other for intensification (e.g., oui oui oui bien sûr OK d’accord ‘yes yes yes of course okay alright’), a tendency that was more frequent in French than in Dutch. Verbal pragmatic markers are, thus, a prime device to express alignment and affiliation, with several functions and configurations that can vary across contexts and languages.

2.3. Visual-Gestural Forms of Feedback

Other studies have been dedicated to visible forms of feedback, pertaining to the visual-gestural modality. A distinction can be made between manual (e.g., gesture) and non-manual features. Non-manuals typically include head movements and facial expressions. Stivers (2008) work on head nods, for example, points to the differences between vocal backchannels (e.g., ‘mm mm’) and head nods. The latter are said to claim access to the teller’s stance, while vocal markers simply align with the activity in progress. Similarly, Whitehead (2011) showed that head nods can be used for a variety of interactional purposes by the interlocutor at different sequential positions. In another study conducted on head nods and their communicative functions more generally, Cerrato (2005) found that the most frequent function associated with head nods (along with other functions, such as turn-taking, emphasis, or giving affirmative response) was feedback, usually produced with repetitive nods. Facial expressions, such as smiling or frowning, also play a role as feedback displays. Smiles, for instance, serve different functions, such as (1) sympathy/understanding, (2) humorous response, (3) mitigation, and (4) avoidance. They also often accompany head nods or other verbal-vocal feedback markers (Nurjaleka, 2023). In addition, smiles have been shown to occur at specific points in the conversation, especially at topic transitions (Amoyal & Priego-Valverde, 2019). Eyebrow frowns or furrows, on the other hand, typically signal communicative problems, especially during repair initiations (Hömke et al., 2025).

Manual feedback forms have received less attention in the literature, as they tend to be less frequent in spoken languages (Bauer et al., 2023). They have been studied more extensively in sign languages (e.g., Mesch, 2016; McKee & Wallingford, 2011, among others), where they include highly conventional forms, such as the palm-up sign or the YES sign. In addition, repeating each other’s gestures, also known as gesture alignment (Bergmann & Kopp, 2012; Rasenberg et al., 2020), gesture mimicry (Kimbara, 2006), or parallel gesturing (Graziano et al., 2011) have been shown to promote alignment and common ground, and can thus be considered forms of feedback.

It should be noted that, terminologically, we reserve the term marker for forms (both verbal and visual) that are conventionalized enough in both form and function, i.e., that are frequent, fixed in form, and associated with a stable meaning. This definition, inspired by the criteria for verbal pragmatic markers (see previous section), can only be applied to the visual-gestural modality with caution, following a detailed analysis of authentic data. Therefore, the identification of gestures or visual features that might qualify as pragmatic markers is a decision that we leave for the analysis (see Section 4.2). In the meantime, the elements from this modality will be more neutrally referred to as “forms” instead.

2.4. Previous Multimodal Studies

Although the field of multimodal discourse analysis is relatively recent, it would be a daunting task to conduct an exhaustive review. Instead, we focus on a selection of multimodal studies that pay particular attention to pragmatic markers. A recent example that also relates to alignment is the study by Inbar and Maschler (2023) on the combination of Hebrew ki ‘because’ with the palm-up gesture in disaffiliative moves (opposition, disagreement, rejection) in casual conversation. In these negative contexts, the palm-up gesture is used with an epistemic function, namely to signal shared knowledge between speakers, and prefaces a causal statement or argument introduced by ki in order to help convince the other speaker of the validity of that argument, thus creating a sense of intersubjectivity and reinstating affiliation.

In an earlier study on French general extenders et tout, et tout ça, tout ça and etcetera (all variants of ‘and so on’), Ferré (2009) questions the status of these phrases as discourse markers (as opposed to propositional elements within lists). She found that, when they are used with a pragmatic meaning, general extenders are more often combined with embodied resources (rotating hands or head movement) than when they simply conclude an enumeration. This study could suggest an affinity between discourse (or pragmatic) markers and visual-gestural forms.

Similarly, other studies conducted on French tu vois ‘you see’ (Skogmyr Marian, 2024) and je (ne) sais pas ‘I don’t know’ (Debras, 2021) have highlighted their visual-gestural features. Debras (2021), for instance, has identified multimodal profiles of the pragmatic marker je (ne) sais pas, looking at recurrent co-occurring gestures. In particular, the author found that full phonetic realizations of the marker (as opposed to reduced forms such as [ʃɛpɑ]) tended to be accompanied by headshakes and gestures which have epistemic/evidential meanings, like shrugs (a combination of shoulder lifts, mouth shrug, and palm-up). The reduced form, however, was less often accompanied by a gesture. In Skogmyr Marian’s (2024) study on tu vois conducted in L2 French, the pragmatic marker was found to be accompanied by rising intonation and mutual gaze, with a gesture oriented toward the interlocutor, to elicit a response. Other studies conducted on English you know (Chen & Adolphs, 2023; Kosmala, 2024), have also shown a tight relationship between you know and co-occurring gestures, especially pragmatic ones.

What these studies have in common is, methodologically, an interest in embodied resources and how they interact with the vocal channel. The concept of multimodal gestalts, as recently used by Mondada (2024) in the context of requests in commercial interactions, is particularly useful in this regard to stress how different devices regularly combine together across modalities in a systematic way, for different purposes in different contexts. Such analyses require a close investigation of the data, ideally mixing qualitative and quantitative methods to obtain both a fine-grained description of the many uses of the gestalts and frequency information to disentangle one-time co-occurrence from conventionalized combinations.

2.5. Aims of the Study

The present study takes a quantitative, bottom-up approach to multimodal markers of feedback. Our goal is threefold. Firstly, we will explore the verbal pragmatic markers that occur in feedback sequences from a mono-modal perspective, regardless of whether they co-occur with visual-gestural forms. Our main goal here is to identify markers that specialize in expressing alignment or affiliation. Secondly, we will replicate this mono-modal descriptive analysis on the visual-gestural forms that occur in feedback sequences (again, whether or not they co-occur with verbal/vocal elements). These first two analyses will provide a unique quantitative perspective to feedback signals, thus filling a gap in the Conversation Analytic literature and in research on pragmatic markers. In a third step, we focus on multimodal combinations (this time including only sequences where both modalities co-occur), with a view to identifying potential multimodal pragmatic markers, that is, frequent and fixed constructions with a stable function. To do so, we will not only use frequency information but also semantic-pragmatic analysis, targeting patterns (or gestalts) where the visual-gestural form seems to alter the semantics of the verbal pragmatic marker. This should inform the discussion regarding the limits of the pragmatic markers category and its application to the visual-gestural modality.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The analyses rely on a sample of the DisReg multimodal corpus (Kosmala, 2020). The data consists of 3- to 5-min random excerpts from 6 video recordings of French students having dyadic conversations about various topics suggested by the researcher (e.g., funny anecdotes, last movies they saw), for a total of 1 h 15 min. Although semi-elicited, the interactions are fairly spontaneous, and the speakers often diverged from the preset topics, as they mostly knew their conversational partner.

3.2. Categorization of Feedback Sequences

We used existing annotations based on the procedure reported in (Kosmala & Crible, in press), of which we give the main steps in what follows. First, any sequence (i.e., single element or combination thereof) was marked as feedback if its primary function was to react to the other speaker’s contribution or action to express mutual understanding (alignment) and/or agreement (affiliation). This reactive nature of feedback excludes de facto contributions that might develop, control, or re-orient the conversation. In terms of sequential organization (Stivers, 2013), this definition of feedback translates into sequences that can only occur after the first-pair part (i.e., when the prior speaker has initiated a turn). More specifically, they can occur during insert expansions or during post-expansions to close the sequence (Stivers, 2013). As soon as the speaker initiates a new sequence, it is no longer considered feedback.

Formally, any element is a potential feedback sequence, such as smiling, laughter, or visual-gestural parameters, even without accompanying speech. This procedure resulted in 431 feedback sequences, which were all double-coded and resolved through discussion in case of disagreement. These sequences were then categorized as expressing either alignment or affiliation, which can, in turn, be subdivided into a positive or a negative value.

- Positive alignment can be paraphrased as “I understand, I see what you mean, you can go on”.

- Negative alignment can be paraphrased as “I don’t understand, I don’t follow, can you reformulate or elaborate before moving on?”.

- Positive affiliation can be paraphrased as “I agree, I have a similar stance as you, I share your perspective”.

- Negative affiliation can be paraphrased as “I disagree, I have another stance or perspective”.

Affiliation presupposes alignment (since agreeing presupposes understanding), which is why we did not resort to double values but opted for affiliation when both dimensions were expressed in the same sequence. The positive vs. negative distinction is entirely contextual in the sense that the same form can be used with both values. For instance, a head shake is typically negative but can express positive affiliation if it aligns with the other speaker’s stance. These annotations were highly reliable, as indicated by an inter-annotator agreement score of κ = 0.78 (type of sequence) and κ = 0.91 (polarity) calculated on 25% of the data. The rest of the data were annotated separately. We further coded the modality of the sequence as either audible, visible, or multimodal, with an agreement score of κ = 0.82.

Within visible and multimodal sequences, the presence of visual-gestural forms was coded, distinguishing between different body articulators, namely the head (“nod”, “shake”, “tilt”, etc.), the face (“smile”, “frown”, “raised eyebrows”, “pout”, etc.), and the hands (“hand gesture”). Whenever these articulators appeared together, they were coded as combinations (e.g., “nod + smile”). The different values are reported in Table 1 in the next section.

Table 1.

Visual-gestural forms by type of feedback sequence (in visible-only and multimodal sequences).

3.3. Identification of Pragmatic Markers

The last step of the analysis consisted of identifying verbal elements that qualify as pragmatic markers, following a broad definition à la Hansen (2006) or Crible (2017). The annotation, thus, included any verbal element that has little or no propositional meaning, is syntactically optional, highly grammaticalized, and functions as an instruction to interpret the coherence between utterances, the structure of the discourse, or the interpersonal relationship between speakers. This definition returned 61 (combinations of) pragmatic markers such as ouais ‘yeah’, mh, ah oui ‘oh right’, mhm, OK ‘okay’, or d’accord ‘alright’. The majority of these markers can be categorized as agreement markers, which some authors distinguish from “discourse markers” such as mais ‘but’ or donc ‘so’ and whose function is closer to relational coherence than to interactional dynamics. We adopted a more encompassing approach that covers both types of markers, since both are relevant to building alignment and affiliation. We only coded pragmatic markers that occurred within a previously identified feedback sequence and not in the other speaker interventions.

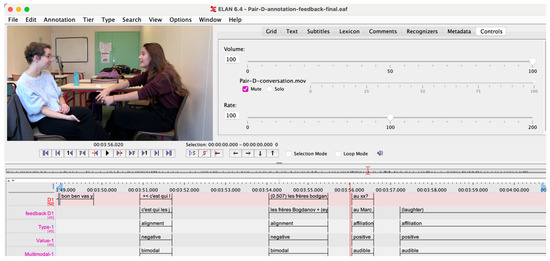

All analyses were conducted on ELAN (Sloetjes & Wittenburg, 2008), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ELAN interface.

4. Results

4.1. Verbal Pragmatic Markers in Feedback Sequences

Out of the 431 feedback sequences identified in the data, 231 (53.6%) include one or several verbal pragmatic markers. As a reminder, this figure also includes cases where the verbal markers co-occur with a visual-gestural form. The most frequent verbal markers are ouais ‘yeah’ (76 occurrences), mh (18), ah oui ‘ah yes’, mhm (11), d’accord ‘alright’, and OK ‘okay’ (10). In addition to these expressions that typically express agreement or alignment, pragmatic markers in feedback sequences also include more standard forms like mais ‘but’, bah ‘well’, alors ‘so/well’, or parce que ‘because’, but to a much smaller extent. Only mais stands out with 12 occurrences, which could be due to its affinity with the expression of (opposing) opinions (see qualitative analysis in Section 4.3 below).

If we break down these figures by feedback type, we can see that verbal markers are present in 58.62% of all sequences expressing alignment, and 43.26% of those expressing affiliation. These proportions go up to 75% and 54%, respectively, if we restrict to the 339 audible and multimodal sequences (that is, excluding visual-only feedback sequences). The difference between alignment and affiliation is statistically significant according to a z-score test for two population proportions (z = 4.116, p < 0.001). It shows that verbal pragmatic markers are very frequent in all types of feedback, but particularly prevalent in expressing alignment. Listeners communicate that they are understanding and following by using markers such as okay or mhm. The relatively smaller proportion in affiliation can be explained by the role of laughter (coded as audible or multimodal) in this type of feedback. Listeners often laugh to react to a joke or a funny anecdote, thereby affiliating with the speaker’s stance (“I agree that this is funny”), which restricts the opportunity for verbal pragmatic markers to occur. A second explanation relates to (Kosmala & Crible, in press) finding that affiliation resorts to specific (rather than generic) expressions more than alignment in order to evaluate or elaborate on some stance or opinion. Pragmatic markers, being generic by definition, will thus occur relatively less frequently in these specific sequences of affiliation.

Zooming in on the particular pragmatic markers that occur in the two sequence types, it appears that the same forms are often used for alignment or affiliation. Ouais is the most frequent marker overall and in both types, either in isolation or combined with other verbal markers (e.g., ah ouais, bah ouais, ouais voilà, ouais ouais OK, etc.). In total, it appears 82 times in alignment and 31 times in affiliation. Examples (1) and (2) illustrate its use in both sequence types.

| (1) | F2 j’ai vu le premier épisode |

| F1 ouais | |

| F2 avec Cécile de France | |

| F2 I saw the first episode | |

| F1 yeah | |

| F2 with Cécile de France | |

| (2) | C1 une seconde femme un peu parce que |

| C2 tu trouves ? ((frown)) | |

| C1 bah elle est très maternelle avec lui | |

| C2 ouais ((frown)) c’est vrai qu’elle le gronde en plus au début | |

| C1 a second wife a bit because | |

| C2 you think so? ((frown)) | |

| C1 well she’s very maternal with him | |

| C2 yeah ((frown)) it’s true that she scolds him also at the beginning |

Ouais is an informal variant of oui ‘yes’, which is less frequent and appears a total of 42 times in alignment and 19 in affiliation. The difference between the two sequence types is thus smaller for oui than for ouais, with relatively more oui in affiliation, which suggests that the former might be closer to its original affirmative semantics while the latter has developed more pragmatic uses, such as expressing mutual understanding.

The majority of the verbal pragmatic markers occur in both alignment and affiliation and tend to be more frequent in the former because alignment is more frequent overall. Exceptions are bah ‘well’ alone or with other verbal markers (bah ouais, bah oui, oui bah ouais du coup), which is much more frequent in affiliation (13 vs. 3 occurrences), mais ‘but’ which has 6 occurrences in both, and rare forms such as exactement ‘exactly’ or si ‘yes’ (after a negation) which are only used once, in affiliation. The affiliative preference of bah reflects its strong connection with ouais and oui, where it reinforces the original affirmative semantics of agreement. Bah seems to add an evidential dimension to agreement (something like “obviously yes”) and thus expresses the speaker’s stance in a more assertive way, which is particularly visible in Example (3) where it is also combined with the expression of strong agreement exactement ‘exactly’.

| (3) | F1 du coup y’a plein de références comme ça euh (0.299) ‘fin du coup j’ai l’impression d’être euh tu sais décalée dans le temps euh |

| F2 bah oui exactement j’avais la même impression quand je regardais en différé | |

| F1 so there are a lot of references like that uh (0.200) I mean so I feel like I’m not in sync in time euh | |

| F2 well yes exactly I had the same feeling when I watched recorded shows |

On the other hand, some (combinations of) markers of two or more instances occur exclusively in alignment sequences. This is primarily the case of d’accord ‘alright’, which, despite what its original semantics of accord ‘agreement’ suggests, has 13 occurrences in alignment and none in affiliation. This shows its high degree of grammaticalization and specialization in the expression of mutual understanding. Other markers exclusive to alignment are the reduplicated ouais ouais (4 occ.) and oui oui (5 occ.), with one notable exception where oui is repeated four times in the same sequence to express affiliation:

| (4) | C1 bon après sur scène je pense que c’est plus abordable que |

| C2 oui vachement plus oui oui oui | |

| C1 well but on stage I think it’s more accessible than | |

| C2 yes much more yes yes yes |

Apart from this exception, reduplicated or repeated ouais and oui express alignment in the data, which is also somewhat counter-intuitive, as was the result for d’accord. One possible explanation is that listeners will rush to signal their understanding with multiple generic markers so that the conversation can continue as soon as possible (i.e., “no need to keep speaking about this, I understand”), whereas affiliation tends to resort to more specific forms of feedback or to combinations of one generic form (e.g., oui) followed by more specific elaborations of stance (cf. “oui vachement plus” in Example 4). These tentative interpretations are only based on our small dataset and should be further substantiated.

All in all, verbal pragmatic markers are highly present in feedback sequences, and relatively more so in alignment than in affiliation, with a few notable exceptions. They mainly consist of markers of agreement that are either used in their original meaning or more abstractly to signal understanding rather than agreement. It appears from this first analysis of the verbal modality that these pragmatic markers very often tend to combine with each other, and that they are very versatile in their meaning-in-context—observations that will also apply to our multimodal analysis in Section 4.3.

4.2. VisualGestural Forms in Feedback Sequences

We now turn to the visual-gestural forms that are used in feedback sequences, following a similar objective of identifying the most frequent forms and those that are favored to express alignment or affiliation. Again, as a reminder, these data also include forms that co-occur with a verbal-vocal element. In our data, two-thirds (283) of the 431 sequences involve visible feedback markers, mostly non-manual signals. This strikingly high rate is similar within alignment (68.25%) and affiliation (60.28%) (not significant: z = 1.6394, p = 0.101). Table 1 shows all visual markers and combinations thereof across sequence types (in both visible-only and multimodal sequences).

In aligning sequences, head nods take up over half of all visual forms, while all others are much less frequent. Nodding is a highly conventionalized form to signal alignment without interrupting the speaker, thus maximizing conversational efficiency (Stivers, 2008). It is also often found in affiliative sequences, where it is the third most frequent device. Nodding often combines with smiling, which is another silent, non-interrupting feedback device.

In affiliative sequences, there is a more balanced use of four main non-manual forms, namely raised eyebrows (28 occurrences in total), smile (18), nod (17), and head tilt (9). This greater variety reflects the wider panel of stance and emotions that can be communicated in feedback, agreement and disagreement, but also surprise, humor, disapproval, concern, etc. These would be expressed through different types of eye or head movements, while alignment is more binary (“I understand” or “I don’t”) and primarily positive, which explains the prevalence of nods in these sequences. Nevertheless, all visual-gestural forms are polyvalent between alignment and affiliation, with at least one occurrence in each type, except for single-occurrence combinations. The variety of visual-gestural forms of feedback, especially in affiliation sequences, attests to the richness of the visual modality and all the embodied resources it offers to express meaning.

Because of this formal variety in our small sample, it is difficult to identify visual/gestural forms that might qualify as conventionalized pragmatic markers. Two exceptions stand out. The first is nodding, which we already described as highly frequent and specialized in the expression of alignment. The combination of high frequency and stable meaning (also observed by Cerrato, 2005) indeed supports its classification as a pragmatic marker, along with its verbal equivalents mhm or ouais.

The second pragmatic marker candidate in the visualgestural modality is raised eyebrows. This is the second most frequent form in feedback sequences and, although it is evenly spread across alignment and affiliation, it seems to display a constant core meaning of (inter-)subjective distance, which can then take on the particular values of surprise or sarcasm. Debras (2025) recently reached a similar conclusion and considered raised eyebrows as a visual pragmatic marker on the basis of its intersubjective core function of expressing a “differential in expectations”. This is illustrated in (5) and (6):

| (5) | C2 par exemple enfin tu te dis que même si le titre c’est les fourberies de Scapin donc on parle de Scapin majoritairement | |

| C1 | ((nods)) | |

| C2 mais en fait il apparaît pas énormément qu’à chaque fois il faut une tierce personne | ||

| C1 | ((head tilt+ raised eyebrows)) | |

| C2 for instance well you realize that even if the title is “Scapin’s tricks” so we talk mostly about Scapin | ||

| C1 | ((nods)) | |

| C2but actually he doesn’t appear so much every time there has to be another person | ||

| ((head tilt+raised eyebrows)) | ||

| (6) | C2 c’est mes rappels de CM2 | |

| C1 ((laughter)) ((raised eyebrows)) ah tu l’as vu en CM2? | ||

| C2 ouais | ||

| C2 it’s my memories from 5th grade | ||

| C1 ((laughter)) ((raised eyebrows)) ah you saw it in 5th grade? | ||

| C2 yeah | ||

In (5), C1 expresses that she slightly disagrees with C2, or at least is not entirely convinced yet by his argument that Scapin never appears on his own in the play, through the co-occurrence of a head tilt and raised eyebrows. She, thus, visually displays some distance from the other speaker’s stance. Alignment and understanding are not at play here since both speakers are quite familiar with the topic discussed. Similarly, in (6), C1 expresses her surprise that C2 studied the play they are talking about at such a young age, again based on her knowledge of the difficulty of this play. The core meaning of (inter-) subjective distancing is thus shared by both examples, which argues in favor of a treatment of raised eyebrows as a visual pragmatic marker.

The combined criteria of high frequency and stable pragmatic meaning thus suggest that nods and raised eyebrows might be potential visual pragmatic markers, on a par with verbal markers such as OK or mhm. However, from a mono-modal perspective alone, visual forms still exhibit a wide formal and functional diversity that can hinder the comparison with verbal pragmatic markers. Let us not forget that our study only targets occurrences within feedback sequences, and it is highly likely that nods or raised eyebrows would display many more configurations in other contexts (cf. Cerrato, 2005 on the other values of nodding). This issue of categorization is, therefore, best tackled from a multimodal perspective, as in the next section, where the combination with verbal-vocal markers further narrows the selection of potential multimodal gestalts to more restricted—and therefore more consistent—contexts of use.

4.3. Multimodal Gestalts

We now focus on the multimodal sequences, and particularly those that combine a visual-gestural element with a verbal form classified as a pragmatic marker. This concerns 153 sequences (66.2%) out of the 231 sequences that contain one or more verbal pragmatic markers, a high figure that already attests to the prevalence of these combinations. Our goal here is to explore whether some patterns are conventionalized enough to be considered as multimodal pragmatic markers or multimodal gestalts.

One criterion to determine that an expression or, in our case, a multimodal pattern, is a pragmatic marker is its high degree of grammaticalization, which requires widespread use in the linguistic community and, therefore, a high frequency. In our limited dataset, following this quantitative criterion alone, only combinations of [ouais + nod] would qualify as multimodal gestalts with at least 19 occurrences, more if we include combinations with additional markers such as [ah ouais + nod] or [ouais + nod + smile]. In the previous section, we observed that nodding is pervasive and a prime device to silently communicate alignment. These multimodal sequences also attest to a non-silent version of nodding where it is combined with the most frequent agreement marker ouais. Preference for the visual or multimodal configuration might be idiosyncratic or depend on factors beyond our scope here. In either case, the two components have a similar semantic charge of agreement.

Given the small size of our data and the variety of forms used in the feedback sequences, it seems relevant to take into account not only frequency but also non-literal meaning as a cue that a particular form is used as a pragmatic marker. As we noted repeatedly above, many verbal and visual-gestural forms are polyvalent and not restricted to their encoded semantics, even displaying an opposite meaning at times. This polysemy and distance from the original literal meaning is another feature of grammaticalization that characterizes many pragmatic markers (e.g., well, actually, etc.). In feedback sequences, non-literal meaning can often be observed with the marker oui ‘yes’, which, combined with some visual-gestural marker, obtains a negative value of disaffiliation. There are two interesting examples of this phenomenon in our data (7)–(8).

| (7) | C1 c’est elle qui a eu l’idée de d’ouvrir les yeux de d’Argan sur euh Béline en faisant tu sais le mort |

| C2 ah oui oui avec ce jeu-là oui c’est vrai c’est vrai | |

| C1 voilà mais euh | |

| C2 ((head tilt)) oui (0.150) mais mm ((wince + gaze away)) mais ça c’est plus pour ((brings her hand to her chin)) | |

| C1 it’s her who had the idea to open Argan’s eyes about Béline by you know playing dead | |

| C2 ah yes yes with this game yes it’s true it’s true | |

| C1 right but uh | |

| C2 ((head tilt)) yes (0.150) but mm ((wince + gazes away)) but that is more to ((brings her hand to her chin)) |

In (7), speaker C2 reluctantly or hesitantly agrees with C1 about the role of a character in one of Molière’s plays. The negative value of the affiliation is conveyed by the head tilt, which slightly precedes the verbal marker. The sequence is immediately followed by the marker of opposition mais ‘but’ (twice) with other visual/gestural forms that indicate interpersonal distance and disapproval, as C2 complements her answer and provides a counter-argument. The visual modality thus clearly indicates from the start of the turn that this is at best a partial, temporary agreement, thereby transforming the meaning of oui. This somewhat differs from the sequence in (8), where another attitudinal or evidential dimension is at play.

| (8) | D1 le type de Les Choristes Jean-Baptiste Meunier au *restaurant* | ||

| D2 | ((nod)) | oui oui oui | |

| D2 | ((eyes wide open)) ah il était au *restaurant*? | ||

| D1 ((head move forward)) mais oui mais mais t’étais là quand non t’étais pas là ? | |||

| D2 | non | ||

| D2 non j’étais pas là | |||

| D1 the guy from Les Choristes Jean-Baptiste Meunier at the *restaurant* | |||

| D2 | ((nod)) | yes yes yes | |

| D2 ((eyes wide open)) ah he was at the *restaurant* ? | |||

| D1 ((head move forward)) well yes but but you were there when no you weren’t there ? | |||

| D2 | no | ||

| D2 no I wasn’t there | |||

In (8), D2 is telling an anecdote that happened at a restaurant (the name has been anonymized), where she saw an actor. D2 believes that D1 was there that time. She first helps D2 identify that actor, which is successful (cf. «oui oui oui»). However, D2 does not believe that she was there during that anecdote and further asks for confirmation that this actor was indeed seen at that restaurant. D1 then replies with mais oui (literally ‘but yes’), a very common answer in conversational French which can take multiple argumentative values. In this case, the head moving forward indicates that mais oui reacts to the relevance of D2’s question. It should be obvious to D2 that the actor was there because, according to D1, D2 was also there that time and saw him, too (a claim that D2 denies in her next turn). The supposedly obvious character of the answer, as well as some attitude of judgment or disbelief (‘you should know this, how come you don’t’) is conveyed by the visual modality. It is thus the combination of mais and the head move that gives oui its negative value, while the visual-gestural marker alone is responsible for this additional attitude of interpersonal distance.

Both (7) and (8) thus illustrate the pragmatic versatility of oui in conversation, with clear negative values conveyed by head movements. In fact, these examples are two of the only three instances of oui which were coded as negative in our data, and all of them are multimodal (the third one is combined with a pout), which confirms that it is the visual modality that enables this shift of semantic value. Therefore, we would argue that multimodal combinations such as (7) or (8) are full-fledged multimodal pragmatic markers, considering that the meaning of the combination is not the same as the meaning of its individual components. This is the criterion that Cuenca and Crible (2019) used to define “compound discourse markers”. Originally proposed for verbal markers only, this notion covers discourse (or pragmatic) markers “that can occur independently but, when combined, they jointly act as a single marker and their individual meaning cannot be disentangled” (p. 172). The authors identify and then, but I mean, or now then as examples of compound discourse markers. We would, therefore, propose that [oui + head movement] is a multimodal compound pragmatic marker since the visual modality alters the meaning of the verbal marker.

Cuenca and Crible (2019) further argue that some co-occurring markers, primarily and then, can either act as a compound discourse marker or simply as single markers that happen to co-occur while retaining their individual meaning, depending on context. This could also be a possibility for multimodal sequences, although in our data, the three [oui + head movement] sequences are all coded as negative and do not display this contextual variation. By contrast, it should be noted that the multimodal gestalt [oui + nod] discussed above does not qualify as a compound pragmatic marker, since the individual meanings are retained. In these sequences, both the verbal and the visual marker express a similar meaning of positive alignment or affiliation, one modality reinforcing the other. They would thus qualify as two co-occurring (but relatively independent) pragmatic markers, one from each modality.

The same can be said of another recurrent combination of semantically aligned forms, namely [voilà + pointing gesture]. Manual gestures are strikingly rare in feedback sequences, with only 11 cases; 5 of them correspond to pointing, of which 3 co-occur with the pragmatic marker voilà ‘that’s it’. Both the verbal and gestural forms share an indexical semantic meaning, which is put to use in feedback sequences to express alignment. The three examples from our dataset are given below. In (9), the two participants are talking about their assignment and realize that they study a similar topic but about different genders. In (10), A1 is describing a board game that involves archeologists, but cannot remember the word for it, while in (11), the two participants are talking about a place where D1 saw celebrities but also cannot remember their names.

| (9) | C2 j’ai le même sujet mais moi c’e:est suivantes et maîtresses | |

| C1 ((raised eyebrows)) a:ah d’accord ah oui | ||

| C2 ouais c’e[:est le personnage féminin] | ||

| ((points back and forth towards herself and C2)) | ||

| C1 | [c’est c’est le:e oui voilà Figure 2] alors que moi c’est le personnage masculin | |

| ((points towards C1 with index finger)) | ||

| C2 I have the same topic but for me it’s maids and mistresses | ||

| C1 ((raised eyebrows)) a:ah okay ah yes | ||

| C2 yeah it’s the[:e female character | ||

| ((points back and forth towards herself and C2)) | ||

| C1 | [it’s it’s the yes that’s it whereas for me it’s the male character | |

| ((points towards C1 with index finger)) | ||

Figure 2.

Example 9, interactive pointing gesture (index finger) co-occurring with voilà.

| (10) | A1 comment ça s’appelle euh qui font des fouilles là? |

| A2 (0.561) un archéologue | |

| A1 un archéologue voilà | |

| ((smiles and points towards A2 with palm oriented side ways, Figure 3)) | |

| A2 ((nods)) | |

| A1 how do you call those who do excavations? | |

| A2 an archeologist | |

| A1 an archeologist that’s it | |

| ((smiles and points towards A2 with palm oriented side ways, Figure 3)) | |

Figure 3.

Example 10, interactive pointing gesture (side palm) co-occurring with voilà.

| (11) | D1 c’est qui les jumeaux ? ((frowns)) |

| D2 tu sais les jumeaux horribles là pleins de chirurgie esthétique ((brings her hands to her face)) | |

| D1 les frères Bogdanoff? | |

| D2 oui voilà et eux ils étaient au *restaurant* | |

| ((points towards D1, Figure 4)) | |

| ((nods and points towards D2 with her little finger)) | |

| D1 who are the twins? ((frowns)) | |

| D2 you know the horrible twins full of plastic surgery ((brings her hands to her face)) | |

| D1 the Bogdanoff brothers? | |

| D2 yes that’s it and they were at the *restaurant* | |

| ((points towards D1, Figure 4)) | |

Figure 4.

Example 11, interactive pointing gesture (little finger) co-occurring with voilà.

In each example, an interactive hand gesture used for pointing (in various forms, using the index finger, the little finger, or the palm) is used in the context of feedback and co-occurs with the marker voilà. All three examples share a similar context, with the multimodal combination signaling the achievement of common ground after a brief period of uncertainty or misalignment. As for [oui + nod], the semantic charge of the two modalities in [voilà + pointing gesture] patterns is similar and the two forms reinforce each other, thus qualifying as a multimodal gestalt (functioning together with a stable pragmatic meaning) but not as a compound pragmatic marker in the sense of Cuenca and Crible (2019), since their individual meaning is retained. The difference between these two multimodal combinations is that the latter is infrequent and thus does not meet either criterion (high frequency and/or non-literal meaning) for pragmatic marker status. We would therefore safely refer to [voilà + pointing gesture] as a multimodal gestalt until more data can confirm whether this pattern is frequent and widespread enough.

In sum, not all multimodal gestalts are the same. Some can be semantically co-oriented and either highly frequent [oui + nod] or infrequent but consistent [voilà + pointing gesture], while others (less frequent) have opposed individual meanings that are blended into a single new function in context [oui + head movement]. As already noted above, an important caveat to this conclusion is that we only analyzed these forms in the context of feedback sequences, which means that patterns that express a stable function in our limited dataset may very well display a more varied spectrum of uses in other contexts or conversation settings. It is, therefore, an obvious avenue of research to further explore these multimodal combinations outside feedback sequences and in different genres in order to draw more robust conclusions about potential multimodal pragmatic markers.

5. Conclusions

This study explores verbal and visual-gestural pragmatic markers of feedback in French conversation, showing how various multimodal resources can be used to express alignment (mutual understanding) and affiliation (shared stance). Quantitative analyses revealed some preferred devices for one function or the other, although polyvalence seems to prevail. Some forms, such as ouais ‘yeah’ and nodding, stand out as highly frequent. As for multimodal combinations or gestalts, we draw a distinction between frequent and co-oriented sequences [ouais + nod] and compound markers that are fused into a new function [oui + head movement], showing a higher degree of grammaticalization. In particular, we showed that the visual-gestural element in these multimodal compound markers alters the semantics of the verbal element, often bringing a disaffiliating value while the verbal modality maintains the illusion of agreement.

While our finding on compound markers strongly relates to Couper-Kuhlen’s (2021) study on oh okay in English, it lacks a prosodic analysis to further describe these multimodal patterns. However, our study stands out from previous accounts by offering a quantitative and bottom-up portrait of feedback markers in a field dominated by qualitative case studies. Replicating these analyses on a larger corpus, across more languages and, ideally, with prosodic analyses, would refine our understanding of the processes of alignment and affiliation in interaction and how they vary across contexts and languages. Future research might also address sociolinguistic variables such as gender, which our study could not robustly account for due to the limited and unbalanced participant sample. Prior research has shown that women tend to provide more feedback than men, reflecting idiosyncratic communicative styles (Maltz & Borker, 2018). Similarly, expanding this inquiry to cross-cultural contexts will require careful consideration of the culturally embedded practices of alignment and affiliation, as demonstrated in comparative studies of backchannels (e.g., White, 1989).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and L.K.; methodology, L.C. and L.K.; software L.C. and L.K.; validation, L.C. and L.K.; formal analysis, L.C. (especially for the pragmatic markers analyses) and L.K. (especially for the visual-gestural analyses); investigation, L.C. and L.K.; resources, L.C. and L.K.; data curation, L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, L.K.; visualization, L.C. and L.K.; supervision, L.C. and L.K.; project administration, L.C. and L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

While this study does involve humans, the data was not submitted to ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is availaible on: https://www.ortolang.fr/market/corpora/corpus-disreg, accssed date 24 April 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amoyal, M., & Priego-Valverde, B. (2019, September 11–13). Smiling for negotiating topic transitions in French conversation. GESPIN—Gesture and Speech in Interaction, Paderborn, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Bangerter, A., & Herbert, C. H. (2003). Navigating joint projects with dialogue. Cognitive Science, 27, 195–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth-Weingarten, D. (2011, June 17–21). The participant perspective: Interactional-linguistic work on the phonetics of talk-in-interaction. Archive of the 2nd International Conference of the Society for the Linguistics of English 2011, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A., Gipper, S., Herrmann, T. A., & Hosemann, J. (2023, April 26–28). Multimodal feedback signals: Comparing response tokens in co-speech gesture and sign languages. MMSYM Conference, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(§6), 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, K., & Kopp, S. (2012, August 1–4). Gestural alignment in natural dialogue. Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 34, ), Sapporo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Boudin, A. (2022, November 7–11). Interdisciplinary corpus-based approach for exploring multimodal conversational feedback. 2022 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (pp. 705–710), Bengaluru, India. [Google Scholar]

- Branigan, H., Catchpole, C., & Pickering, M. J. (2011). What makes dialogue easy to understand? Language and Cognitive Processes, 26(10), 1667–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, L. (2005, August 6–8). Linguistic functions of head nods. Multi-Modal Communication (pp. 137–152), Göteborg, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., & Adolphs, S. (2023). Towards a speech–gesture profile of pragmatic markers: The case of “you know”. Journal of Pragmatics, 210, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Col, G., Danino, C., Knutsen, D., & Rault, J. (2016). Rôle de voilà dans l’affirmation: Valeur confirmative et marque d’intégration d’informations. Testi e Linguaggi, 10, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2021). OH + OKAY in informing sequences: On fuzzy boundaries in a particle combination. Open Linguistics, 7(1), 816–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crible, L. (2017). Discourse markers and (dis)fluency in English and French. Variation and combination in the DisFrEn corpus. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 22(2), 242–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crible, L., Gandolfi, G., & Pickering, M. J. (2024). Feedback quality and divided attention: Exploring commentaries on alignment in task-oriented dialogue. Language and Cognition, 16(4), 895–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, M. J., & Crible, L. (2019). Co-occurrence of discourse markers in English: From juxtaposition to composition. Journal of Pragmatics, 140, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debras, C. (2021). Multimodal profiles of je (ne) sais pas in spoken French. Journal of Pragmatics, 182, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debras, C. (2025). An evidential function of raised eyebrows in interaction: Marking a differential in expectations. In Multimodal communication from a construction grammar perspective (pp. 190–219). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Delahaie, J. (2009). Oui, voilà ou d’accord? Enseigner les marqueurs d’accord en classe de FLE. [Oui, voilà or d’accord? Teaching markers of agreement in the FFL classroom]. Synergies Pays Scandinaves, 4, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Delahaie, J., & Solís García, I. (2019). Ok /d’accord/ vale: Étude contrastive des marqueurs du français de France et de l’espagnol d’Espagne. [OK /d’accord/ vale: A contrastive study of markers from France French and peninsular Spanish]. Lexique, 25, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X. (2009). Listener response. The Pragmatics of Interaction, 4, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmann, A., & Llewellyn, L. (1968). Relationship between vocalizations and head nods as listener responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, G. (2009, September 9–11). Analyse multimodale des particules d’extension «et tout ça, etc.» en français. Interface Discours Prosodie (IDP09) (pp. 157–171), Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Ferré, G., & Renaudier, S. (2017). Unimodal and bimodal backchannels in conversational English. SEMDIAL, 2017, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fox Tree, J. E. (1999). Listening in on monologues and dialogues. Discourse Processes, 27(1), 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R. (2001). When listeners talk. In Pbns.92. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Available online: https://benjamins.com/catalog/pbns.92 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Goodwin, C. (2010). Multimodality in human interaction. Calidoscopio, 8(2), 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, M., Kendon, A., & Cristilli, C. (2011). Parallel gesturing in adult-child conversations. In Integrating gestures (pp. 89–102). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.-J. M. (2006). A dynamic polysemy approach to the lexical semantics of discourse markers (with an exemplary analysis of French toujours). In K. Fischer (Ed.), Approaches to discourse particles (pp. 21–42). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P., Mills, G. T., Gregory, J., Eshghi, A., & Howes, C. (2018). Running repairs: Coordinating meaning in dialogue. Topics in Cognitive Science, 10, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hömke, P., Levinson, S. C., Emmendorfer, A. K., & Holler, J. (2025). Eyebrow movements as signals of communicative problems in human face-to-face interaction. Royal Society Open Science, 12(3), 241632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, A., & Maschler, Y. (2023). Shared knowledge as an account for disaffiliative moves: Hebrew ki ‘because’-clauses accompanied by the palm-up open-hand gesture. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 56(2), 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbrat-Orecchioni, C. (2016). Oui et ses variantes en français: L’expression de l’accord dans les débats présidentiels. Testi e Linguaggi, 10, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbara, I. (2006). On gestural mimicry. Gesture, 6(1), 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmala, L. (2020, July 6–10). Euh le saviez-vous? le rôle des (dis)fluences en contexte interactionnel: Étude exploratoire et qualitative. Congrès Mondial de Linguistique Française, CMLF 2020, Montpellier, France. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmala, L. (2024, November 18–19). Pragmatic functions of ‘You Know’ in tandem interactions: Insights from the visualgestural modality. Paper presented at Les marqueurs discursifs (dé)verbaux, Amiens, France. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmala, L., & Crible, L. (in press). (Mis)alignment and (dis)affiliation within feedback sequences in face-to-face interactions. Journal of Pragmatics. [Google Scholar]

- Maltz, D. N., & Borker, R. A. (2018). A cultural approach to male-female miscommunication. In The matrix of language (pp. 81–98). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, R. L., & Wallingford, S. (2011). ‘So, well, whatever’: Discourse functions of palm-up in New Zealand Sign Language. Sign Language & Linguistics, 14(2), 213–247. [Google Scholar]

- Mesch, J. (2016). Manual backchannel responses in signers’ conversations in Swedish Sign Language. Language & Communication, 50, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mondada, L. (2014). Pointing, talk and the bodies: Reference and joint attention as embodied interactional achievements. In M. Seyfeddinipur, & M. Gullberg (Eds.), From gesture in conversation to visible utterance in action (pp. 95–124). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(3), 336–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, L. (2024). Requesting in shop encounters. Multimodal gestalts and their interactional and institutional accountability. In M. Selting, & D. Barth-Weingarten (Eds.), New perspectives in interactional linguistics research (pp. 278–309). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F. E. (1996). Affiliating and disaffiliating with continuers: Prosodic aspects of recipiency. In E. Couper-Kuhlen, & M. Selting (Eds.), Prosody in conversation: Interactional studies (pp. 131–176). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nurjaleka, L. (2023). Backchannels responses as conversational strategies in the interaction of Indonesian speakers in interview setting. REiLA: Journal of Research and Innovation in Language, 5(2), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(02), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2021). Understanding dialogue: Language use and social interaction. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rasenberg, M. (2023). Mutual understanding from a multimodal and interactional perspective [Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud University Nijmegen]. [Google Scholar]

- Rasenberg, M., Özyürek, A., & Dingemanse, M. (2020). Alignment in multimodal interaction: An integrative framework. Cognitive Science, 44(11), e12911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, H. (1974). An analysis of the course of a joke’s telling in conversation. In R. Bauman, & J. Sherzer (Eds.), Explorations in the ethnography of speaking (pp. 337–353). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, M. F., & Clark, H. H. (1989). Understanding by addressees and overhearers. Cognitive Psychology, 21(2), 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogmyr Marian, K. (2024). Longitudinal change in linguistic resources for interaction: The case of tu vois (‘you see’) in L2 French. Interactional Linguistics, 4(1), 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloetjes, H., & Wittenburg, P. (2008, May). Annotation by category-ELAN and ISO DCR. 6th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2008), Marrakech, Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- Steensig, J. (2020). Conversation analysis and affiliation and alignment. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), The concise encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 248–253). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(1), 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stivers, T. (2013). Sequence Organization. In J. Sidnell, & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Streeck, J. (2009). Gesturecraft: The manu-facture of meaning (Vol. 2). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Tobback, E., & Lauwers, P. (2016). L’emploi des marqueurs d’accord dans les débats télévisés néerlandophones et francophones: À la recherche d’un éthos communicatif “belge” perdu? Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, 117(2), 371–397. [Google Scholar]

- White, S. (1989). Backchannels across cultures: A study of Americans and Japanese. Language in Society, 18(1), 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, K. A. (2011). Some uses of head nods in “third position” in talk-in-interaction. Gesture, 11(2), 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).