Abstract

Reading comprehension in Chinese as a second language (L2 Chinese) presents unique challenges due to the language’s logographic writing system. Analysis of oral reading miscues reveals specific patterns in L2 learners’ reading processes and comprehension difficulties. Despite established theoretical frameworks for miscue analysis in alphabetic languages, empirical research on miscues in logographic systems such as Chinese remains limited, particularly regarding their relationship with reading comprehension. This study investigates the relationship between oral reading miscues and literal comprehension of Chinese texts among L2 Chinese learners. Sixty-six intermediate-level Chinese learners from U.S. universities participated in the study. Oral reading and sentence-level translation tasks were administered to examine miscues and assess comprehension. Through analyzing the oral reading data, we identified 14 types of oral reading miscues, and they were categorized into four categories: orthographic, syntactic, semantic, and word processing miscues. Results showed strong negative correlations between oral reading miscues and comprehension. Orthographic, syntactic, and semantic miscues were negatively correlated with reading comprehension performance, while word processing miscues showed no significant correlation with comprehension. The findings reveal the complex relationship between character recognition, word processing behaviors, and comprehension in L2 Chinese reading, and suggest a need for a nuanced approach to oral reading error correction in L2 Chinese reading instruction. Based on the findings, pedagogical implications for effective reading instruction and reading assessment in L2 Chinese classrooms are discussed.

1. Introduction

Reading in a second language (L2) is a complex cognitive process that involves the integration of various linguistic skills and knowledge sources. For L2 learners of Chinese whose first language (L1) is alphabetic, this process involves unique challenges due to the specific features of the Chinese writing system, including its logographic nature and the absence of word boundaries (Shen & Jiang, 2013; Sproat & Gutkin, 2021; Yang, 2021b; H. Zhang, 2018). These linguistic features necessitate specific reading processes and skills that may differ from those used in alphabetic language reading, such as character component analysis, radical-based meaning inference, and word segmentation strategies.

Research on L2 Chinese reading has grown significantly in recent years, exploring areas such as character recognition (T. Zhang & Ke, 2018), word segmentation (Shen & Jiang, 2013; Yang, 2021b), and reading strategies (Ke & Chan, 2017). While these studies have provided valuable insights into the cognitive processes underlying L2 Chinese reading, the application of oral reading miscue analysis to L2 Chinese reading offers a potentially fruitful avenue for further investigation, particularly in identifying miscue patterns, examining miscue–comprehension relationships, and informing L2 Chinese reading instruction. This approach, which has provided valuable insights into the relationship between oral reading behaviors and reading comprehension in alphabetic languages (Beatty & Care, 2009; Y. M. Goodman & Goodman, 2014; Latham Keh, 2017), will offer new perspectives on how L2 Chinese learners process and comprehend texts during oral reading.

This study aims to extend this line of inquiry by providing a qualitative and quantitative analysis of oral reading miscues in L2 Chinese and their relationship to reading comprehension at the literal comprehension level. The emphasis on literal-level comprehension is based on its foundational role in reading acquisition and its potential to clarify connections between oral reading performance and basic text processing. The motivation for investigating this relationship lies in its significant implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically, it can clarify how different aspects of linguistic knowledge function within logographic systems, which may differ from alphabetic languages. Pedagogically, understanding which miscues correlate with comprehension can help instructors focus on key aspects of reading instruction, develop targeted strategies, and enhance assessment practices for L2 Chinese learners. Through this analysis, the study aims to contribute to a better understanding of reading processes in L2 Chinese, and to offer insights for L2 Chinese reading instruction and reading assessment practices.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework of Oral Reading Miscue Analysis

Oral reading miscue analysis, pioneered by K. S. Goodman (1969), provides insights into the reading process by examining unexpected responses during oral reading. These departures from the original text, termed “miscues”, are viewed not as mere errors, but as indicators of the reader’s cognitive processes and strategies. This approach is grounded in the psycholinguistic theory of reading, which posits that reading is an active process involving the interaction between thought and language (Y. M. Goodman, 2014). This perspective shifted the focus from viewing reading errors as deficits to seeing them as indicators of the reader’s cognitive processes and reading strategies (Almazroui, 2007; Beatty & Care, 2009; Y. M. Goodman, 2015; Theurer, 2002). Since its inception, Goodman’s miscue analysis framework has been widely adopted and adapted in both first language (L1) and L2 reading research (Blair et al., 2022; Latham Keh, 2017; McKenna & Picard, 2006; Moore & Brantingham, 2003; Wang, 2020; Wilde, 2000; Wurr et al., 2008).

In alphabetic languages, researchers have identified several common types of miscues, including substitutions, insertions, omissions, repetitions, and self-corrections, in both L1 and L2 reading (Beatty & Care, 2009; Gillet et al., 1990; Y. M. Goodman & Goodman, 2014; Latham Keh, 2017). These miscues are often analyzed in terms of their graphophonic (visual and phonological), syntactic, and semantic characteristics, providing insights into how readers utilize various sources of linguistic information during reading (Beatty & Care, 2009). For instance, a miscue that maintains syntactic and semantic acceptability may indicate that the reader is prioritizing meaning construction over exact word recognition.

The relationship between oral reading miscues and reading comprehension is complex and multifaceted, with studies yielding varied results. Research on the relationship between miscues and comprehension in ESL learners has generally identified a negative correlation between the frequency of miscues and reading comprehension scores (Jeon, 2012; X. Jiang, 2016). However, the relationship is not always straightforward. Geva and Farnia (2012) observed that while oral reading accuracy was strongly correlated with reading comprehension for beginning L2 English readers, this relationship became less pronounced as learners advanced in their language proficiency. Y. M. Goodman and Goodman (2014) argued that miscues that preserve the semantic and syntactic acceptability of the text are less likely to interfere with comprehension than those that disrupt meaning. This perspective is further supported by Kucer’s research (Kucer, 2009), which found that substitutions maintaining grammatical function and meaning had a minimal impact on overall comprehension. While these studies provide valuable insights into the relationship between oral reading miscues and comprehension in alphabetic languages, the complexity of this relationship in different language contexts remains an area of ongoing investigation.

2.2. Unique Features of Chinese Reading

The Chinese writing system presents distinct characteristics that influence the reading process, particularly for learners from alphabetic language backgrounds. Unlike alphabetic systems, Chinese uses a logographic script, where characters typically represent morphemes rather than phonemes (Perfetti & Harris, 2013). This fundamental difference has significant implications for how readers process and comprehend Chinese text.

One notable feature of Chinese characters is their visuo-orthographic complexity. Characters are composed of strokes and radicals arranged in various spatial configurations, with the number of strokes in a single character ranging from one to over thirty (Shen & Bear, 2000). This complexity imposes significant demands on visual processing skills, requiring readers to develop sophisticated strategies for character recognition and discrimination (Ehrich et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2013)

Another distinctive feature of Chinese text is the absence of word boundaries. Unlike in alphabetic scripts, there are no spaces between words in written Chinese. This characteristic necessitates an additional cognitive process of word segmentation, which can be particularly challenging for L2 learners (Shen & Jiang, 2013; Yang, 2021b). Readers must use their lexical knowledge and contextual cues to determine where one word ends and another begins, a process that is crucial for accessing the appropriate contextual meaning of words.

Finally, the tonal nature of the Chinese language adds another layer of complexity to the oral reading process. Tones are an integral part of Chinese syllables and play a crucial role in distinguishing meaning. While native speakers process tones automatically, L2 learners often struggle with tonal discrimination and production (H. Zhang, 2018; L. Zhang, 2019). In the context of oral reading, this can lead to difficulties in activating the correct phonological representations of characters, potentially impacting comprehension.

2.3. Oral Reading and Miscue Analysis in L2 Chinese

Oral reading in L2 Chinese involves a complex interplay of skills, including efficient character recognition, accurate pronunciation, and effective word segmentation. Shen and Jiang (2013) found that context-free character reading accuracy was a strong predictor of reading comprehension for beginning L2 learners of Chinese. This highlights the crucial role of character recognition in Chinese reading, a finding that aligns with the importance of word recognition in alphabetic language reading (Fuchs et al., 2001).

However, fluent oral reading in Chinese goes beyond mere character recognition. The absence of word boundaries in Chinese text means that readers must also engage in online word segmentation as they read aloud. Yang (2021b) demonstrated that word segmentation ability significantly contributes to both reading fluency and comprehension in L2 Chinese, even after controlling for context-free word recognition skills. This underscores the unique demands placed on L2 Chinese readers, who must simultaneously recognize characters, segment words, and construct meaning as they read aloud.

The challenges faced by L2 Chinese readers are further reflected in the types of miscues they produce during oral reading. Shen et al. (2020) conducted a study of oral reading miscues in L2 Chinese, identifying several types of miscues, including mispronouncing tones, misreading characters, substitution, insertion, omission, self-correction, reversal of word order, repetition, pauses between words, inappropriate pauses within a word, inappropriate word segmentation, and radical-related misreading. These miscues were categorized into groups based on linguistic features. The results showed that certain types of miscues were negatively correlated with silent reading comprehension. Although the study provides a framework for understanding the various challenges faced by L2 learners in Chinese reading, further studies are needed to explore many unanswered questions, such as the specific relationship between different types of miscues and literal-level comprehension in L2 Chinese reading.

3. The Current Study

The current study investigated the literal-level reading comprehension in L2 Chinese among intermediate-proficiency L2 Chinese leaners in the United States. Literal-level comprehension is defined as the reader’s ability to understand explicitly stated information in the text without making inferences or drawing conclusions beyond the given information (Basaraba et al., 2013; Kintsch, 1988). In the context of reading skills, literal-level comprehension is often considered a lower-level reading skill, as opposed to higher-level skills such as inferential or evaluative comprehension (Kintsch, 1998; Perfetti & Stafura, 2014).

The study focused on oral reading miscues and literal-level reading comprehension for several reasons. Firstly, literal comprehension forms the foundation for higher-level understanding in language learning. It is a crucial first step in the reading process, especially for L2 learners, who may struggle with basic text decoding. Secondly, oral reading miscues are likely to be closely associated with literal understanding. Misreading a character or word could directly affect a learner’s ability to grasp the basic meaning of a sentence or passage. Additionally, examining literal-level comprehension allows for a more direct assessment of the relationship between oral reading performance and basic text understanding, which can provide valuable insights into L2 Chinese learners’ cognitive processing in reading, the relationship between linguistic knowledge and comprehension, and reading instruction practices.

To examine the relationship between oral reading miscues and literal-level reading comprehension, we employed a sentence-by-sentence translation task. This method allows for a higher resolution of analysis compared to the comprehension tests used in previous studies, potentially offering new insights into the nuanced relationship between miscue types and text understanding. Specifically, this study answers the following research questions:

- What types of oral reading miscues do L2 Chinese learners produce when reading Chinese texts?

- What is the relationship between oral reading miscues and literal-level passage comprehension in L2 Chinese reading?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

A total of 66 L2 Chinese learners (21 males and 45 females, mean age 21) from eight U.S. universities participated in this study. The majority of participants (n = 57) were native English speakers, with the remaining participants being native speakers of other alphabetic languages (e.g., Spanish, Italian, Turkish). At the time of the study, all participants were using English as their primary language of academic instruction in their university programs.

At the time of data collection, 30 participants were enrolled in Second-Year and 36 in Third-Year Chinese classes, having completed 250–450 hours of college-level classroom instruction. Based on the institutional placement tests, they were classified as intermediate-proficiency learners.

Our decision to focus on intermediate L2 Chinese learners was based on several considerations. Firstly, beginner learners typically have limited character acquisition and are still in the process of developing word recognition abilities, which constrains their capacity for full-fledged meaningful reading comprehension. Secondly, intermediate learners have acquired a foundation of characters and words to facilitate reading comprehension, while their primary strategies for reading comprehension remain focused on decoding and constructing literal-level sentence meanings. Thus, focusing on intermediate L2 learners provides an optimal window for examining the relationship between lower-level linguistic skills and reading comprehension processes.

4.2. Instruments

4.2.1. Oral Reading Passages

Two instructional-level Oral Reading Passages were used to elicit L2 Chinese learners’ oral reading miscues (see Appendix A). The selection of instructional-level materials was based on Gillet et al.’s (1990) model of three reading levels: independent, instructional, and frustration. Instructional-level materials, which are level-appropriate, matching learners’ proficiency while providing a suitable challenge, offer an optimal balance for eliciting meaningful miscues without causing frustration. To ensure the passages were appropriate for intermediate-proficiency L2 Chinese learners, we applied the following four criteria.

The first criterion was novelty, ensuring that texts were new and unpracticed by participants in order to elicit authentic responses. To meet this criterion, passages were chosen from Intermediate course of experiencing Chinese (L. Jiang, 2012); a textbook was not used by the participants in this study.

The second criterion focused on topic familiarity to ensure reading engagement of participants. Two texts were selected: “理想职业” (Ideal Job) and “当代大学生与名牌消费” (College Students and Famous Brand Consumption). To verify the familiarity of these topics, five Chinese language instructors from three U.S. public universities rated them on a scale of 1–5, where 1 indicated “not at all familiar to intermediate learners” and 5 indicated “highly familiar to intermediate learners”. These instructors, all native Chinese speakers, each had more than five years of experience teaching Chinese at various proficiency levels in university settings. The mean scores were 4.0 for the first topic and 4.6 for the second. These relatively high scores confirmed that both topics were familiar and relevant to the target learners.

The third criterion addressed linguistic suitability, ensuring that the text type, vocabulary, and grammar were appropriate for intermediate L2 Chinese learners. The same five Chinese language instructors evaluated the overall linguistic appropriateness of the passages on a scale of 1–5, where 1 indicated “not at all appropriate for intermediate learners” and 5 indicated “highly appropriate for intermediate learners”. The average ratings were 4.3 for Passage 1 (Ideal Job) and 4.1 for Passage 2 (College Students and Famous Brand Consumption). These ratings suggested that the instructors viewed both texts as suitable for the target intermediate-proficiency group.

The final criterion addressed oral reading fluency (ORF), aiming for materials that would allow learners to achieve an ORF range of 83–88% based on Shen’s (2019) scale. ORF is defined as the accuracy rate of character reading in one minute. To validate this criterion, a pilot study was conducted with five Second-Year L2 Chinese learners, which confirmed mean ORFs of 86.8% and 84.6% for Passages 1 and 2, respectively.

4.2.2. Literal Comprehension Task

A Literal Comprehension Task was developed using the exact text from the two instructional-level reading passages that were used in the oral reading. This task was specifically designed to assess literal-level comprehension, which involves understanding the explicitly stated content without making inferences or gaining new insights while reading.

The task required participants to translate eight paragraphs from Chinese to English, four from each passage. The translation method was chosen over multiple-choice tests because it provides both word- and sentence-level understanding of reading materials. Unlike multiple-choice tests, where correct answers can sometimes be guessed, translation enables researchers to identify specific areas of difficulty in character recognition, lexical access, and syntactic parsing, which are directly related to oral reading performance.

4.3. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted remotely through individual Zoom meetings to facilitate participation across different geographical locations. The procedure began with an introduction and explanation of the study, during which participants were informed about the tasks and given the opportunity to ask questions.

Following this introduction, participants were provided with a Qualtrics link, through which they accessed the two Oral Reading Passages (see Appendix A). They were instructed to read the passages aloud immediately, without preparation time, following standardized instructions (see Appendix B). Participants’ oral reading was audio-recorded for later analysis.

Upon completion of the reading task, participants were directed to a second Qualtrics survey. This survey contained the Literal Comprehension Task and a brief background questionnaire. The background questionnaire collected basic demographic information, including age, gender, and native language, as well as participants’ current Chinese language learning status, such as their university and instructional level. For the Literal Comprehension Task, participants received standardized instructions for translation (see Appendix B).

The entire process was designed to take approximately one hour, striking a balance between comprehensive data collection and respect for participants’ time. As compensation for their participation and to ensure motivation, each participant received $20 upon completion of all tasks.

4.4. Data Coding and Scoring

The data coding and scoring process was conducted in two main parts: analysis of oral reading miscues and evaluation of the Literal Comprehension Task. For the oral reading miscues, the process began with the researcher meticulously transcribing and examining all 66 audio recordings. From these transcriptions, miscues were identified and subsequently classified into various types, which were then grouped into four overarching categories.

In categorizing miscues, particular attention was paid to distinguishing between misreading characters (MC) and radical-related or shape-similar misreading (RM). MC was coded in two scenarios: (1) when learners produced pronunciation inaccuracies despite recognizing the character; and (2) when learners produced arbitrary pronunciations due to complete non-recognition of characters, without showing influence from radical knowledge or visual similarity. In contrast, RM was coded specifically when there was clear evidence that the miscue was motivated by either radical knowledge or visual similarity between characters. For example, reading “虑” as “虎” due to the shared component “虍” would be coded as RM, while reading “选” (xuǎn) as “suǎn” would be coded as MC.

The inclusion of mispronouncing tones (MT) as a miscue category was based on several considerations. First, to provide a comprehensive analysis of L2 Chinese learners’ oral reading behaviors, we needed to document all types of deviations from standard pronunciation. Second, given the prevalent classroom practice of immediate tone correction during reading activities, we aimed to empirically examine whether tonal accuracy in oral reading relates to comprehension. This analysis could help to inform evidence-based decisions about error correction priorities during reading instruction.

For each type of miscue, we calculated its frequency and percentage of occurrence in the total number of miscues identified. The categorization framework employed in this study, while based on a comprehensive literature review and theoretical considerations, is inherently exploratory. To ensure the reliability of this coding process, a second rater, a Ph.D. student specializing in L2 Chinese acquisition, independently coded 30% of the data (20 participants’ recordings). The inter-rater reliability was found to be high, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.95 (p < 0.01), indicating strong consistency between the two raters.

The scoring of the Literal Comprehension Task involved several steps to ensure accuracy and consistency. Initially, standard translations were developed through detailed discussions between the researcher and an advanced L2 Chinese learner who was a native English speaker. Based on these discussions, scoring criteria were established using a 0–5 point scale for each sentence.

Table 1 presents this rubric, which includes criteria and specific examples for each score level to illustrate how these criteria were applied in practice. The task, comprising 15 sentences from Passage 1 and 14 sentences from Passage 2, had a maximum possible score of 145 points.

Table 1.

Scoring criteria for the literal comprehension task, with examples.

As with the miscue coding, two raters were involved in the scoring process. The researcher scored all the translation data, while the second rater (the same Ph.D. student involved in miscue coding) graded 30% of the data. The inter-rater reliability for this process was also high, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.97 (p < 0.01). For both the miscue coding and comprehension task scoring, any discrepancies between the raters were carefully reviewed and resolved through thorough discussion, ensuring a consensus was reached. This approach to data coding and scoring, involving multiple raters and statistical checks for reliability, served to enhance the validity and reliability of the study’s findings.

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. RQ1: What Types of Oral Reading Miscues Do L2 Chinese Learners Produce When Reading Chinese Texts?

The qualitative analysis revealed that L2 Chinese readers made a total of 5392 miscues. These miscues were further classified into 14 types. Twelve of these types were consistent with those identified by Shen et al. (2020), while two new types were identified in this study: misreading polyphones (MP) and English translation (TR). To provide a clear overview, Table 2 summarizes these 14 types of miscues with examples.

Table 2.

Types of oral reading miscues with examples.

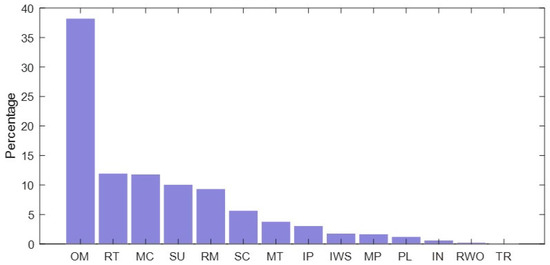

The distribution of these miscues varied, with some types occurring more frequently than others. Table 3 presents the frequency and percentage of each miscue type. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the miscue distribution data from Table 3, with the miscue types arranged in descending order based on their frequency.

Table 3.

Distribution of fourteen types of oral reading miscues.

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of oral reading miscue types.

To further understand the linguistic and cognitive nature of these miscues, they were classified into four categories: orthographic miscues (ORM), syntactic miscues (SYM), semantic miscues (SEM), and word processing miscues (WPM). Since readers immediately corrected themselves, SC miscues could not be considered a miscue that affected reading comprehension (Kucer, 2009; Shen et al., 2020); thus, they were removed from further categorization. The TR and RWO miscues were also removed from further categorization, due to their very low detection rate (<0.5%). Table 4 provides a summary of these categories.

Table 4.

Categories of oral reading miscues.

To clarify the distinction between the SYM and SEM categories, miscues that created grammatical violations were classified as SYM, while those that maintained grammatical acceptability but caused semantic changes were categorized as SEM. Any ambiguous cases were resolved through rater discussion.

5.2. RQ2: What Is the Relationship Between Oral Reading Miscues and Literal-Level Passage Comprehension in L2 Chinese Reading?

To answer the question about the relationship between oral reading miscues and literal-level passage comprehension in L2 Chinese reading, correlation analyses were performed. The results indicated a strong negative correlation (r = −0.869) between the total number of miscues and the translation scores. This finding suggests that fewer oral reading miscues are associated with better literal-level comprehension of Chinese passages, revealing a strong relationship between oral reading accuracy and literal-level comprehension in L2 Chinese reading.

To further understand the relationship between specific types of miscues and comprehension, Pearson correlation analysis was conducted for 10 types of miscues. Four types of miscues were excluded from this analysis: self-correction (SC) miscues were excluded as they represent immediate corrections that likely do not affect comprehension; additionally, insertion (IN), reversal of word order (RWO), and English translation (TR) were excluded due to their very low frequency of occurrence (<1% of total miscues: IN = 0.65%, RWO = 0.28%, TR = 0.06%). Table 5 presents the results of these tests.

Table 5.

Pearson correlations between 10 types of miscues and literal comprehension (n = 66).

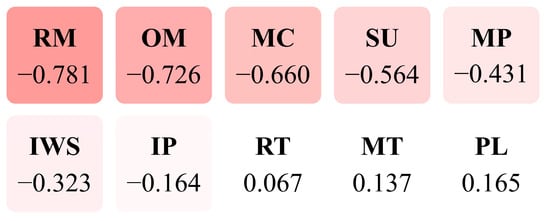

As shown in Table 5, several miscue types demonstrated significant negative correlations with literal comprehension scores, with radical-related or shape-similar misreading (RM) showing the strongest negative correlation (r = −0.781), followed by omission (OM) (r = −0.726) and misreading characters (MC) (r = −0.660). To provide a visual summary of these relationships, Figure 2 presents a heatmap visualization of the correlation coefficients.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of Pearson correlations between miscue types and literal comprehension.

In this heatmap, the color gradient from deep red to light pink represents the strength of negative correlations, with darker red indicating stronger negative relationships. White cells represent near-zero correlations. We further analyzed the relationship between miscue categories and comprehension. Table 6 presents these results.

Table 6.

Pearson correlation among the four categories of miscues and literal comprehension (n = 66).

As shown in Table 6, three categories—orthographic miscues (ORM), syntactic miscues (SYM), and semantic miscues (SEM)—showed statistically significant negative correlations with passage comprehension. In contrast, the word processing miscues (WPM) category showed no significant correlation with passage comprehension. These results suggest differential relationships between miscue categories and comprehension, providing initial empirical support for the proposed categorization framework. To understand the inter-relationships among these miscue categories, we conducted another correlation analysis. Table 7 presents these results.

Table 7.

The correlation matrix among the four categories of miscues (n = 66).

Table 7 shows that ORM, SYM, and SEM categories are intercorrelated, suggesting a complex relationship between different aspects of language knowledge and reading comprehension. The WPM category, however, is not significantly correlated with the other three categories.

6. Discussion

6.1. Miscue Types and Categories in L2 Chinese Reading

This study revealed 14 types of oral reading miscues produced by L2 Chinese learners, expanding upon the 12 types identified by Shen et al. (2020). The two additional miscue types discovered in this study were misreading polyphones (MP) and English translation (TR). This adds new findings to the existing taxonomy to provide a better understanding of the challenges faced by L2 Chinese learners in their reading for meaning.

Among the identified miscue types, omission (OM) was the most frequent, accounting for 38.27% of all miscues. This high frequency of omissions is primarily attributed to the unique nature of the Chinese writing system. Unlike alphabetic systems, Chinese characters cannot be accurately pronounced based solely on their visual form, even for phono-semantic compounds, where the phonetic component does not always reliably indicate the actual pronunciation (Shu et al., 2003). When students encounter unfamiliar characters, they often choose to skip them, rather than attempt pronunciation. This finding highlights the crucial role of character recognition in Chinese reading. In contrast, learners of alphabetic languages like English often have the option to attempt sounding out unfamiliar words based on letter–sound correspondences, a strategy not readily available to readers of Chinese characters.

Repetition (RT) and misreading characters (MC) were also notably frequent, at 11.99% and 11.84%, respectively. The high occurrence of repetitions could indicate a strategy employed by L2 learners to gain processing time or to self-monitor their comprehension. In our classification, repetition is categorized as a word processing miscue (WPM), reflecting the cognitive demands of reading in a non-native logographic system.

The prevalence of character misreading (MC) underscores the challenge of mastering the complex phonological system of Chinese, where subtle differences in initials, finals, or both can significantly alter meaning. This finding is consistent with previous research highlighting the difficulties that L2 learners face in Chinese character recognition and pronunciation (Shen, 2005; T. Zhang & Ke, 2018).

The categorization of miscues into four broad categories—orthographic miscues (ORM), syntactic miscues (SYM), semantic miscues (SEM), and word processing miscues (WPM)—provides valuable insights into the nature of reading difficulties in L2 Chinese learners.

The ORM category, including miscues like mispronouncing tones (MT), misreading characters (MC), and radical-related or shape-similar misreading (RM), reflects challenges in character recognition and pronunciation, highlighting the importance of orthographic knowledge in Chinese reading (Shen & Ke, 2007).

Among the ORM category, radical-related or shape-similar misreading (RM) deserves special attention, due to its unique relevance to the Chinese writing system. RM miscues, accounting for 9.37% of all miscues in this study, reflect the challenges that L2 learners face when encountering the complex structure of Chinese characters. Unlike alphabetic languages, Chinese characters are composed of various components, some of which function as radicals that often provide semantic or phonetic cues, while others may serve primarily as visual elements. However, these components can sometimes be misleading for L2 learners, especially when characters share similar visual elements, but have different meanings or pronunciations. For example, a learner might misread “虑” (lǜ, to consider) as “虎” (hǔ, tiger) due to the shared component “虍”. This type of miscue demonstrates that the learner recognizes the shared component, indicating some level of component awareness. However, it also highlights the challenges in accurately distinguishing between similar characters. Such confusion highlights the importance of developing accurate character recognition skills in Chinese reading. It also underscores the need for focused instruction on distinguishing between visually similar characters in L2 Chinese teaching (Shen & Ke, 2007; T. Zhang & Ke, 2018).

The SYM category, encompassing partial substitution (SU), insertion (IN), and omission (OM) miscues, may not necessarily indicate difficulties with Chinese syntax exclusively. Rather, it might reflect a combination of syntactic awareness and word recognition issues. For instance, omissions or substitutions could result from both syntactic uncertainty and unfamiliarity with specific characters or words.

The SEM category, including the remaining partial SU, IN, and OM miscues, seems to be more closely related to meaning-making processes. These miscues often reflect learners’ attempts to maintain text coherence despite gaps in vocabulary or contextual understanding. For instance, a learner might substitute a known word for an unknown one based on their interpretation of the overall passage meaning.

The WPM category, comprising repetition (RT), long pauses between words (PL), inappropriate pauses within a word (IP), inappropriate word segmentation (IWS), and misreading polyphones (MP), represents challenges in smooth oral reading. These miscues reflect the cognitive demands of reading Chinese text, and often indicate strategies used by learners to manage the processing load, such as repeating words to gain more processing time.

6.2. Relationships Between Oral Reading Miscues and Literal-Level Reading Comprehension

This study provides insights into the complex relationships between oral reading miscues and literal-level comprehension in L2 Chinese reading. A strong negative correlation (r = −0.869) was observed between the total number of miscues and the translation scores. This finding suggests that readers who make fewer oral reading miscues tend to have better literal-level comprehension of Chinese passages. This relationship suggests that oral reading miscue analysis could serve as a diagnostic tool for assessing L2 Chinese learners’ reading performance. This finding aligns with previous research in L2 reading, indicating a strong relationship between oral reading accuracy and reading comprehension in Chinese as a second language (Shen & Jiang, 2013).

Our results demonstrate that not all miscues correlate equally with comprehension scores. Moderate-to-high negative correlations were observed for radical-related or shape-similar misreading (RM) (r = −0.781) and omission (OM) (r = −0.726). These strong correlations may be associated with the critical role of accurate character recognition in Chinese reading comprehension. RM miscues, in particular, highlight the importance of visual information processing in Chinese reading, as misreading visually similar characters can significantly alter the meaning of the text.

Moderate negative correlations were found for misreading characters (MC) (r = −0.660) and substitution (SU) (r = −0.564). The moderate nature of these correlations might be attributed to the varied impact of these miscues on comprehension. For instance, some MC miscues may relate to pronunciation problems that do not necessarily hinder comprehension, while others might stem from character misrecognition that does impede understanding. This variability in impact could explain why these correlations, while significant, are not as strong as those for RM and OM.

Lower negative correlations were observed for misreading polyphones (MP) (r = −0.431) and inappropriate word segmentation (IWS) (r = −0.323). These lower correlations suggest that these miscues do not always severely impact comprehension. For example, contextual clues might help readers to understand the meaning even when they mispronounce a polyphone or segment words incorrectly.

Interestingly, some miscue types showed no significant correlations with comprehension, including inappropriate pauses within a word (IP), repetition (RT), mispronouncing tones (MT), and long pauses between words (PL). The lack of correlation for mispronouncing tones (MT) is noteworthy. While tonal accuracy is crucial for spoken communication in Chinese (Orton, 2013), our results suggest it may not play as critical a role in reading comprehension for L2 learners. This can be explained by the nature of the Chinese writing system, where readers access meaning primarily through visual recognition of characters that represent morphemes directly through their orthographic form, rather than through phonological components (Perfetti & Harris, 2013; Shen, 2013). In Chinese reading, the orthographic–semantic pathway tends to dominate over phonological processing (Yang, 2021a), allowing learners to understand a character’s meaning through visual recognition even when they struggle with accurate tone production during oral reading.

When examining the relationships between miscue categories and comprehension, we found that orthographic miscues (ORM) showed a moderate-to-high negative correlation with comprehension (r = −0.735). This relationship underscores the importance of visual information processing in Chinese reading, aligning with previous research emphasizing radical awareness in Chinese character acquisition and reading (Shen & Ke, 2007). Similarly, syntactic miscues (SYM) demonstrated a strong negative correlation with comprehension (r = −0.755), indicating that syntactic awareness and word recognition issues are closely linked to reading comprehension in L2 Chinese. Semantic miscues (SEM) exhibited a moderate negative correlation with comprehension (r = −0.505), reflecting a clear connection between semantic processing and comprehension in L2 Chinese reading.

However, word processing miscues (WPM) showed no significant correlation with comprehension (r = −0.089). This suggests that disruptions in the flow of oral reading may not necessarily impede overall text understanding in L2 Chinese. While word processing miscues may affect reading speed, they do not necessarily hinder comprehension performance. This finding points to a complex relationship, where word knowledge may influence comprehension through multiple pathways.

Furthermore, our analysis of the correlation matrix among the four categories of miscues revealed an interesting pattern. The ORM, SYM, and SEM categories were found to be intercorrelated, while the WPM category did not show significant correlations with the other three categories. This pattern suggests a complex relationship between different aspects of language knowledge in L2 Chinese reading. The intercorrelations among the ORM, SYM, and SEM categories indicate that these aspects of learners’ linguistic knowledge together play a significant role in reading comprehension. These results indicate that L2 Chinese readers rely on multiple sources of information when constructing meaning from text (Huang, 2018). The strong negative correlations of the ORM, SYM, and SEM categories with comprehension highlight areas where targeted instruction might be beneficial. However, the lack of significant correlation between WPM and comprehension, as well as its lack of correlation with other miscue categories, is particularly intriguing. It suggests that L2 Chinese readers might employ compensatory strategies (Bernhardt, 2005, 2010; Lee-Thompson, 2008; McNeil, 2012) to maintain comprehension even when their word recognition is not fully automatic.

These findings point towards a more complex relationship, where word knowledge relates to comprehension through multiple pathways. While accurate and fluent word recognition may facilitate faster reading (Everson, 1998; Shen & Jiang, 2013), it does not guarantee better comprehension. Conversely, slower, more effortful reading due to word processing miscues does not necessarily relate to poorer comprehension. This suggests that L2 Chinese readers may allocate significant cognitive resources to word recognition and segmentation, potentially at the expense of reading speed, but not necessarily comprehension.

7. Pedagogical Implication

The findings of this study offer several pedagogical implications for teaching Chinese as a second language, particularly in the areas of reading education. This study underscores the critical importance of character recognition in L2 Chinese reading comprehension. Given the strong correlation between orthographic miscues (ORM) and comprehension, teachers should prioritize activities that enhance character recognition skills. This could involve integrating regular character component analysis exercises, and the use of digital flashcard apps for spaced repetition, into their curriculum. By strengthening students’ orthographic knowledge, teachers can help to reduce the occurrence of RM (radical-related misreading) and OM (omission) miscues, which our study found to be strongly correlated with comprehension difficulties.

This study indicated that learners made miscues during oral reading. How can we make reading instruction effective by analyzing students’ oral reading miscues? Rather than correcting every miscue, teachers should guide students to focus on those that showed stronger negative correlations with comprehension. Based on the finding that word processing miscues (WPM) showed no significant correlation with comprehension (r = −0.089), teachers might consider noting significant miscues and providing feedback after the oral reading session, rather than interrupting during reading. This approach maintains reading flow, while allowing teachers to address these more critical miscue types.

The finding that mispronouncing tones (MT) showed no significant correlation with comprehension suggests that excessive focus on tone correction during reading activities may not significantly benefit reading comprehension. Teachers might consider reserving detailed tone correction for speaking-focused activities instead, while prioritizing character recognition accuracy during reading instruction.

For learners, developing effective self-monitoring strategies is crucial. Encouraging students to keep a personal miscue journal, practice think-aloud protocols during reading, and engage in peer reading sessions for mutual feedback can increase metacognitive awareness and help them to identify and address their specific reading challenges.

The implications of this study extend to reading assessment practices as well. Miscue analysis can serve as a valuable diagnostic tool, allowing teachers to identify specific areas of difficulty for individual learners and track progress over time in different aspects of reading proficiency. When assessing reading skills, teachers should place greater emphasis on comprehension, rather than perfect pronunciation, and consider the use of retelling or summarization tasks alongside oral reading to gauge understanding. A balanced assessment approach that incorporates measures of both accuracy (through miscue analysis) and fluency (reading speed), combined with comprehension questions, can provide a more holistic evaluation of a learner’s reading abilities.

While this study provides valuable insights into understanding the relationship between oral reading miscues and reading comprehension, we acknowledge its focus on examining only literal-level comprehension among intermediate-proficiency Chinese learners. Future studies investigating how the relationship between miscues and comprehension varies across different proficiency levels, as well as longitudinal research tracking learners’ progress in miscue and reading comprehension behaviors, are needed to further our knowledge of the L2 Chinese reading process and acquisition.

8. Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between oral reading miscues and literal-level comprehension in L2 Chinese reading. Our analysis identified 14 types of miscues by adding two more miscue types, which further extend the existing framework for analyzing L2 Chinese reading behaviors. The findings revealed a strong negative correlation between the total number of miscues and the translation scores, indicating that fewer oral reading miscues are associated with better literal-level comprehension of Chinese passages. Specifically, orthographic, syntactic, and semantic miscues showed significant negative correlations with comprehension scores, highlighting the importance of these aspects in L2 Chinese reading. Word processing miscues did not show a significant correlation with comprehension scores, suggesting a complex relationship between word processing behaviors and overall text understanding in L2 Chinese. These findings contribute to our understanding of L2 Chinese reading processes and inform approaches to L2 Chinese reading education.

Funding

Partial financial support was received from The Center for Asian and Pacific Studies (CAPS) at the University of Iowa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Iowa (IRB ID: 202012397; date of approval: 11 March 2021) as an exempt study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Helen H. Shen for her valuable suggestions during this research.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| L2 | Second language |

| ORF | Oral reading fluency |

| MT | Mispronouncing tones |

| MC | Misreading characters |

| SU | Substitution |

| IN | Insertion |

| OM | Omission |

| SC | Self-correction |

| RWO | Reversal of word order |

| RT | Repetition |

| PL | Long pauses between words |

| IP | Inappropriate pauses within a word |

| IWS | Inappropriate word segmentation |

| RM | Radical-related or shape-similar misreading |

| MP | Misreading polyphones |

| TR | English translation |

| ORM | Orthographic miscues |

| SYM | Syntactic miscues |

| SEM | Semantic miscues |

| WPM | Word processing miscues |

Appendix A

Oral Reading Passages

| Passage 1 理想职业 | 有的人想当医生,有的人想当警察,你呢?你有自己的理想职业吗?如果没有,请你先问问自己几个问题。我的兴趣是什么?我喜欢做什么?我适合做什么? 一个人要是能根据自己的爱好去选择职业,他就会更爱自己的工作、更想去工作。比如,科学家爱迪生,他差不多每天都工作十几个小时,但是他一点儿也不觉得辛苦,反而觉得每天都非常快乐。 很多人总是很难了解自己的兴趣是什么、自己适合什么。我们可以在生活中发现自己、认识自己,了解自己能做什么、不能做什么。比如作家斯贝克一开始也没有想到自己会成为作家。开始的时候,因为他有一米九高,所以爱上了篮球,当了一名运动员。后来,因为打球打得不是很好,而且年龄也越来越大了,又改行当了画家。最后他终于发现原来自己有写文章的才能,于是成为了一个有名的作家。 发现自己的兴趣,根据兴趣选择自己的职业,你的生活才会更快乐,才更容易把工作做好。 |

| Passage 2 当代大学生与名牌消费 | 最近中国经济快速发展。中国作为世界上最大的市场,吸引了来自世界各地的商品。很多品牌成为中国人心中的“世界名牌”。大家追求生活品质的标准越来越高,人人都开始赶时髦、要面子、买名牌。 顾客喜欢名牌可能有几个原因。第一,虽然名牌商品的价格比较高,但是质量有保证。第二,在各个大城市的商场一般都有名牌的专卖店,所以退换商品都很方便。第三,用名牌不但能体现自己的生活方式,而且还会受到别人的尊重。 选择名牌商品有很多好处,但是非名牌不买就一定好吗?名牌商品价格很高,有的大学生为了买到名牌,用各种办法省钱,连正常生活水平都不能保证。有的人想显示身份却又没有那么多钱,于是开始买假名牌。名牌热也给学生们带来了不好的影响。有的大学生买东西上瘾,甚至忘记了学习。 大学生应该建立正确的购物观,在选择名牌商品以前应该先考虑自己的经济能力。 |

Appendix B

Task Instructions

- a.

- Oral Reading Task Instructions:

“Please read aloud the following two passages at your natural and comfortable pace. Your reading will be audio-recorded. If you encounter any unfamiliar Chinese characters or words, you may make your best guess or skip them. This is not a test, so don’t worry about your performance. Please do not use any external resources during this task.”

- b.

- Literal Comprehension Task Instructions:

“Please translate all eight paragraphs from the two passages you just read into English. Provide the most accurate translation you can, focusing on conveying the literal meaning of the Chinese text. If you are unsure about any part, you may leave it blank or provide your best guess.”

References

- Almazroui, K. M. (2007). Learning together through retrospective miscue analysis: Salem’s case study. Reading Improvement, 44(3), 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Basaraba, D., Yovanoff, P., Alonzo, J., & Tindal, G. (2013). Examining the structure of reading comprehension: Do literal, inferential, and evaluative comprehension truly exist? Reading and Writing, 26, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, L., & Care, E. (2009). Learning from their miscues: Differences across reading ability and text difficulty. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 32(3), 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, E. (2005). Progress and procrastination in second language reading. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 25, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, E. (2010). Understanding advanced second-language reading. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H., Filipek, J., Fu, H., Lin, X., & Sun, M. (2022). When learners read in two languages: Understanding Chinese-English bilingual readers through miscue analysis. Language and Literacy, 24(2), 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, J. F., Zhang, L. J., Mu, J. C., & Ehrich, L. C. (2013). Are alphabetic language-derived models of L2 reading relevant to L1 logographic background readers? Language Awareness, 22(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everson, M. E. (1998). Word recognition among learners of Chinese as a foreign language: Investigating the relationship between naming and knowing. The Modern Language Journal, 82(2), 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, E., & Farnia, F. (2012). Developmental changes in the nature of language proficiency and reading fluency paint a more complex view of reading comprehension in ELL and EL1. Reading and Writing, 25, 1819–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, J. W., Temple, C. A., Crawford, A. N., & Cooney, B. (1990). Understanding reading problems: Assessment and instruction. Scott Foresman/Little, Brown Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, K. S. (1969). Analysis of oral reading miscues: Applied psycholinguistics. Reading Research Quarterly, 5, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, Y. M. (2014). Retrospective miscue analysis: Illuminating the voice of the reader. In Making sense of learners making sense of written language (pp. 205–221). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Y. M. (2015). Miscue analysis: A transformative tool for researchers, teachers, and readers. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 64(1), 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, Y. M., & Goodman, K. S. (2014). To err is human: Learning about language processes by analyzing miscues. In Making sense of learners making sense of written language (pp. 115–134). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. (2018). Effective strategy groups used by readers of Chinese as a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 30(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, E. H. (2012). Oral reading fluency in second language reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 24(2), 186–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L. (2012). 体验汉语中级教程 (Intermediate course of experiencing Chinese). 高等教育出版社 (Higher Education Press). Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=_ybjsgEACAAJ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Jiang, X. (2016). The role of oral reading fluency in ESL reading comprehension among learners of different first language backgrounds. Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 16(2), 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, S., & Chan, S.-D. (2017). Strategy use in L2 Chinese reading: The effect of L1 background and L2 proficiency. System, 66, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W. (1988). The role of knowledge in discourse comprehension: A construction-integration model. Psychological Review, 95(2), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kucer, S. B. (2009). Examining the relationship between text processing and text comprehension in fourth grade readers. Reading Psychology, 30(4), 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham Keh, M. (2017). Understanding and evaluating English learners’ oral reading with miscue analysis. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 60(6), 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Thompson, L. C. (2008). An investigation of reading strategies applied by American learners of Chinese as a foreign language. Foreign Language Annals, 41(4), 702–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. C., Chen, X., Deacon, S. H., Zhang, J., & Yin, L. (2013). The role of visual processing in learning to read Chinese characters. Scientific Studies of Reading, 17(1), 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M. C., & Picard, M. C. (2006). Revisiting the role of miscue analysis in effective teaching. The Reading Teacher, 60(4), 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, L. (2012). Extending the compensatory model of second language reading. System, 40(1), 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R. A., & Brantingham, K. L. (2003). Nathan: A case study in reader response and retrospective miscue analysis. The Reading Teacher, 56(5), 466–474. [Google Scholar]

- Orton, J. (2013). Developing Chinese oral skills: A research base for practice. Research in Chinese as a Second Language, 9, 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti, C., & Harris, L. N. (2013). Universal reading processes are modulated by language and writing system. Language Learning and Development, 9(4), 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfetti, C., & Stafura, J. (2014). Word knowledge in a theory of reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. H. (2005). An investigation of Chinese-character learning strategies among non-native speakers of Chinese. System, 33(1), 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. H. (2013). Chinese L2 literacy development: Cognitive characteristics, learning strategies, and pedagogical interventions. Language and Linguistics Compass, 7(7), 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. H. (2019). An investigation on instructional-level reading among Chinese L2 learners. Journal of Second Language Teaching and Research, 7, 184–211. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H. H., & Bear, D. R. (2000). Development of orthographic skills in Chinese children. Reading and Writing, 13, 197–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. H., & Jiang, X. (2013). Character reading fluency, word segmentation accuracy, and reading comprehension in L2 Chinese. Reading in a Foreign Language, 25(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H. H., & Ke, C. (2007). Radical awareness and word acquisition among nonnative learners of Chinese. The Modern Language Journal, 91(1), 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H. H., Zhou, Y., & Gao, G. (2020). Oral reading miscues and reading comprehension by Chinese L2 learners. Reading in a Foreign Language, 32(2), 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, H., Chen, X., Anderson, R. C., Wu, N., & Xuan, Y. (2003). Properties of school Chinese: Implications for learning to read. Child Development, 74(1), 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sproat, R., & Gutkin, A. (2021). The taxonomy of writing systems: How to measure how logographic a system is. Computational Linguistics, 47(3), 477–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurer, J. L. (2002). The power of retrospective miscue analysis: One preservice teacher’s journey as she reconsiders the reading process. Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal, 2(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. (2020). Adult English learners and the bilingual reading process: Retrospective miscue analysis. Bilingual Research Journal, 43(4), 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, S. (2000). Miscue analysis made easy: Building on student strengths. ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Wurr, A. J., Theurer, J. L., & Kim, K. J. (2008). Retrospective miscue analysis with proficient adult ESL readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(4), 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. (2021a). Diagnosing reading problems for low-level Chinese as second language learners. System, 97, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. (2021b). Investigating word segmentation of Chinese second language learners. Reading and Writing, 34(5), 1273–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. (2018). Current trends in research of Chinese sound acquisition. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese second language acquisition (pp. 217–233). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. (2019). Tone features of Chinese and teaching methods for second language learners. International Journal of Chinese Language Education, 5, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T., & Ke, C. (2018). Research on L2 Chinese character acquisition. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese second language acquisition (pp. 103–133). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).