Abstract

Despite its demographic relevance, Spanish as an Immigrant Minority Language (IML) remains understudied in Europe. In Brussels, approximately 46,500 residents have Hispanic heritage, but their linguistic practices have largely remained unexplored in sociolinguistic research. This paper presents a pilot study on the language practices of the Hispanic communities in the city in order to assess language maintenance and vitality. Through an online survey among 125 adults with Hispanic heritage in Brussels, primarily first-generation immigrants, a highly multilingual sample was revealed, with most participants competent in at least four languages. While Spanish usage declines across generations, language competence remains high, with 60% of third-generation speakers still considering it one of their dominant languages. Findings challenge traditional minority–majority language maintenance perspectives, advocating for a multilingual approach to linguistic vitality. Patterns of language transmission, home language use, and integration highlight the communities’ adaptability while maintaining a connection to Spanish. Results point to unexplored sociolinguistic phenomena within the language minority, underscoring the need for further research on the Hispanic communities in Brussels.

1. Introduction

In late 2024, the Instituto Cervantes (2024) released its yearly publication of El español en el mundo, where it announced that, for the first time ever, they recorded over 600 million Spanish users in the world (including learners and users with limited proficiency). With nearly 500 million native speakers and an official status in over 20 countries and territories, it may be unusual to think of Spanish as a minority language, particularly from a European perspective: “since Spanish is so widely spoken, that creates a sense of stability in its maintenance; after all, what can happen to a language spoken by so many millions of people?” (Polinsky, 2023, p. 16). This may be seen through a different lens in countries like the United States, where the considerable number of hispanophones as a result of the language’s historical presence and migration from Hispanic countries has made Spanish as a heritage language a widespread and well-studied phenomenon. However, in Europe too Spanish stands out as a relevant immigrant minority language, with recent demolinguistic studies identifying nearly 5.5 million Spanish speakers with a migratory background living in the continent outside of Spain (Loureda Lamas et al., 2023). Nonetheless, this field of inquiry remains comparatively understudied in Europe (Instituto Cervantes, 2024; Loureda Lamas, 2023; Irizarri van Suchtelen, 2016),1 particularly regarding its use and status as a consequence of migration and minorization; a limitation that Extra (2011) identifies for immigrant minority languages in the entire continent more generally.

This paper presents the results of an exploratory pilot study on Spanish as an immigrant minority language in Brussels. While renowned for its diverse and multilingual population, there have been very few studies regarding the city’s language minorities as a result of migration. Research on the matter has receded into the background behind the already complex backdrop of Brussels’ Dutch–French societal bilingualism (Verlot & Delrue, 2004; although see Li et al., 2022; Forlot & Lucchini, 2019; Extra & Yağmur, 2004, 2008 for examples of rectifying efforts). Nevertheless, immigrant minority languages are certain to be prominent in a city where over 70% of the population has foreign roots (Statbel, 2024),2 including approximately 46,500 residents with Hispanic heritage whose language practices remain largely unaccounted for (IBSA, 2024).3

In order to address this gap, this exploratory investigation used online surveys to map out the linguistic repertoires of Brussels residents with Hispanic heritage, as well as their language use in different types of communicative settings. Additionally, the surveys aimed to allow inferences regarding the degree of language maintenance or shift across generations.

With this information, the investigation endeavored to paint a general canvas of language practices and transmission in Brussels’ Hispanic communities, allowing for a first estimate of the linguistic vitality of Spanish in the city, and laying the groundwork for future, more large-scale studies into the linguistic practices of the group. Furthermore, the paper seeks to highlight language maintenance research on multilingual contexts, where a competitive multilingual landscape like the one in Brussels might yield different results than what has been traditionally researched in environments with a single majority language.

Before delving into the study, Section 2 of the paper will provide a brief overview of previous research on minority languages (Section 2.1), language maintenance, shift, and vitality (Section 2.2), as well as the positioning of Spanish in Brussels (Section 2.3). Next, Section 3 will outline the methodology used for the study, while Section 4 will present and analyze the results. Finally, Section 5 provides a conclusion for the investigation by interpreting the collected results to assess Spanish vitality within the sample and by identifying the potential sociolinguistic phenomena that warrant further exploration within the communities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Key Definitions: Immigrant Minority Languages and Heritage Languages

An assortment of terms can be used to discuss languages in minority contexts such as Spanish in Brussels. As a general concept, they would be defined as minority languages, which, put simply, refer to languages spoken by less than half of the population in a community, usually benefiting from lower social status or generally associated with a potential risk in terms of group stability (Edwards, 2010). As the name suggests, Immigrant Minority Languages (IMLs) are those used by immigrant groups, as opposed to minority languages with a regional base or that have been historically minoritized in the community (Extra, 2011; Extra & Gorter, 2001). Additionally, the term Heritage Language (HL) is sometimes used synonymously with IML (Fishman, 2001; Aalberse et al., 2019), as it is also defined as a non-dominant language in a bi/multilingual territory with a connection to its speakers’ cultural roots. However, a key distinction comes from the definition of a heritage speaker, for which the manner of acquisition is usually naturalistic in the form of oral input at home, which may or may not be later reinforced in educational contexts (Rothman, 2009; Loureda Lamas et al., 2023; Aalberse et al., 2019). This generally produces circumstances of early bilingualism, which usually becomes unbalanced and favors the majority language of the territory (Polinsky, 2023; Jiménez-Jiménez et al., 2023; Aalberse et al., 2019).

Following these definitions, as this paper studies different generations of Spanish-speaking immigrants in Brussels, it will see Spanish through the lens of an immigrant minority language, naturally connected to its speakers’ heritage, and that includes in its sample second-, third-, or later generation descendants who would be considered as heritage speakers.

2.2. Language Maintenance and Shift and Language Vitality

One of the key characteristics of a minority language is the potential threat to its linguistic stability (Edwards, 2010). A key effort in sociolinguistic research has been to study linguistic minorities’ maintenance of their language, or lack thereof, and the factors that might affect it. This has been the case, at least, since the second half of the 20th century, when research on language maintenance and language shift emerged as a field of inquiry (Pauwels, 2016). In his seminal work, Language loyalty in the United States, Fishman (1966) predicted that language shift, that is, the replacement of a community’s language by another usually in the majority, generally prevails, ensuing within three generations. This three-generation model, while it holds true in some scenarios, has been deemed overly deterministic, as it ignores certain socioeconomic, political, and cultural factors that can affect its applicability across different contexts (Szpiech et al., 2020; Villa & Rivera-Mills, 2009; Loriato, 2019). As such, the field is still preoccupied with studying if, when, and why maintenance or shift takes place for specific minority communities.

One of the notions associated with the study of this phenomenon is language vitality, used to assess the communicative dynamics of a minority community and gauge its language prospects (Bourhis et al., 2019). Originally conceptualized as Ethnolinguistic Vitality (ELV) by Giles et al. (1977), it was defined as what “makes a group likely to behave as a distinctive and active collective entity in intergroup situations” (Giles et al., 1977, p. 308). Higher vitality, assessed through the community’s status, demography, and institutional support, was associated with a higher likelihood of the group remaining a collective entity and, therefore, of the community language surviving (Bourhis et al., 2019).

Since its conception, ELV has been adapted into several models (some examples of this are Fishman’s (1991) Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale and UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages’ (2003) Index). Additional indicators and subjective measures that may affect language vitality have also been considered to respond to limitations and expand the applicability of the original framework. Models have been put forward to study vitality as perceived by community members (Bourhis et al., 1981), while attention has also been drawn to the crucial fact that “[m]ost of the existing empirical studies in the ELV framework did not actually measure language use” (Olko, 2024, p. 119), urging scholars to include measures of language practices as part of the overall evaluation of vitality.

A refined concept of language vitality (see, for instance, Van der Avoird et al., 2001) builds on ELV and has been used to compare the status of immigrant minority languages across European contexts. Extra and Yağmur (2004) raise the point that previous study of linguistic vitality was focused on a list of non-exhaustive affecting factors rather than on the operationalization of the phenomenon itself, in line with Olko’s (2024) observation above. As such, they embark on the creation of a language vitality index based on four dimensions (Extra & Yağmur, 2004, p. 125):

- Language proficiency, particularly focused on comprehension;

- Language choice, especially at home with the mother;

- Language dominance over other languages they speak;

- Language preference.

This approach takes the construction of language profiles as the means to define and measure vitality, while also drawing attention to the multilingual repertoires that traditionally characterize minority communities in European contexts.

2.3. Spanish as an IML in Brussels

With a total of 186 different nationalities coexisting in the Brussels-Capital Region (IBSA, 2025), Belgium’s capital hosts a panoply of different languages that are used regularly for daily interaction. This makes the backdrop of the present investigation an incredibly multilingual one. Beyond official French and Dutch, spoken by 81% and 22.3% of the population in the capital region, respectively, English thrives as the most spoken foreign language, mastered to a conversational level by 46.9%, followed by Spanish (14.5%), Arabic (11.5%), Italian (6.1%), and German (6.1%) (Saeys, 2024). Furthermore, the Brussels context seems to foster a high degree of vitality for minority languages, as relatively strong patterns of transmission for various IMLs have been attested across generations (Janssens, 2018, p. 58; Extra & Yağmur, 2004, p. 358; Li et al., 2022).

The presence of Spanish in Brussels is related to migratory movements. It started with an influx of Spanish so-called guest laborers in the late 1950s, which was later joined by more recent migration of highly educated workers, largely due to the city’s development as an international administrative and political center (Verlot & Delrue, 2004). Migration waves from Hispanic countries in the Americas are more recent, starting only in the 1970s, with a mass influx in the 1990s, mainly as a result of economic and political migration (Sáenz & Salazar, 2007). Nowadays, Spaniards represent the 5th largest foreign group in the capital region with nearly 32,500 residents, while there are over 14,000 Hispanic Americans listed in Brussels’ registry (IBSA, 2024).

As a result of these migratory movements, Spanish is currently a widely spoken minority language in the population. Following Janssens’ (2018) language barometers, which gauge the number of residents in the Brussels-Capital Region with good-to-excellent knowledge in a language, Spanish has consistently remained on the city’s top five most spoken languages since 2007, with numbers going up to 8.9% of the population in 2013 (Janssens, 2018, p. 22), and no less than 14.5% of the population in the 2024 survey, currently making Spanish the 4th most spoken language in the city, only behind English and co-official French and Dutch (Saeys, 2024). Furthermore, 6.4% of the Brussels population has Spanish as a home language, although about 70% of these Spanish speakers use it alongside at least one other language in the home context (Saeys, personal communication, 4 February 2025, based on the forthcoming results of the latest language barometer survey). This means that nearly 80,000 inhabitants have a strong family connection to Spanish, highlighting its significant presence among other minorities in the area and the pressing need to overview the circumstances surrounding its use as an IML in the city.

Nevertheless, research that considers Spanish as an IML in Brussels is scarce. Only a limited number of existing studies consider the city’s Hispanic communities per se (e.g., Garzón, 2014), while most have a broader outlook that includes speakers with Hispanic heritage within their participants (e.g., Forlot & Lucchini, 2019; Hollebeke et al., 2022; Van Mensel, 2016). As such, the field remains significantly underexplored, highlighting the urgent need for research into the experiences of Brussels’ Spanish-speaking minority communities.

As an initial step to engage with these lacunae, this paper used online questionnaires to address the following research questions: What are the linguistic repertoires and language practices of people with Hispanic heritage in Brussels throughout different generations? And what can be inferred from these repertoires and practices about the degree of Spanish maintenance or shift in the city? Previous studies within the framework of language vitality and maintenance in Brussels have suggested relatively strong patterns of transmission for certain immigrant minority languages (Janssens, 2018, p. 58; Extra & Yağmur, 2004, p. 358; Li et al., 2022). Following this, we hypothesize that a certain degree of Spanish knowledge will be maintained by third-generation heritage speakers, accompanied by rising proficiencies in French, the city’s most spoken language. Similarly, as is common in heritage contexts, we expect Spanish use to decrease throughout the generations while Brussels’ majority languages become increasingly more used, with an emphasis on French from the second generation onwards and on English as a contact language for the first generation. Nevertheless, considering the relatively high levels of Spanish vitality among children in the city found by Extra and Yağmur (2004), we hypothesize that some degree of Spanish use will be maintained by the third generation, particularly in the family and friendship domain.

3. Methodology

The present investigation was designed as an exploratory study on speakers of Spanish as an IML in Brussels. Data were collected through an online Qualtrics questionnaire and diffused through targeted social media advertisement (Meta). Selection criteria included being at least 18 years old, living in the Brussels Metropolitan Area, and having Hispanic origins (i.e., coming from a Spanish-speaking country or having someone who does in their ancestry).

3.1. The Questionnaire

The questionnaire, available in Spanish, English, French, and Dutch, was adapted from previously used instruments from language maintenance research (Cohn et al., 2013; Li et al., 2022; Martín, 1996). It aimed to outline (1) participants’ demographic and sociolinguistic background, (2) their linguistic repertoires and self-assessed proficiency, and (3) their language practices throughout different domains.

Most sociodemographic data were collected through closed-ended questions with lists or dropdown menus. Data on language proficiency were gathered through self-reported measures using can-do statements for speaking, listening, reading, and writing adapted from the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR; Council of Europe, 2020). Three statements were used per language skill corresponding to the framework’s echelons of “basic user”, “independent user”, and “proficient user”, respectively. For the analysis, these statements were transformed into a numerical scale from 1 to 3, allowing for the creation of a general proficiency variable, averaging all four skills, where 1 indicates a basic level of proficiency, 2 an intermediate one, and 3 a proficient user.

Data on language practices were also gathered through self-reported measurements, this time for the frequency of use of each language in a participant’s repertoire. Participants were asked to fill out a matrix table ranking the rate with which they use each language (matrix columns) in a list with various interlocutors and situations (matrix rows; see Figure 1). This was assessed through a score from 0 to 10, where 0 meant that the language was never used in that specific situation and 10 meant that it was always used. If a situation did not apply to a participant (for example, if they did not have siblings), they were instructed to write NA in each language box. Despite these instructions, a small number of participants provided responses that diverged from the intended guidelines of the matrix table, highlighting a limitation that should be addressed in future assessments using this method. To deal with inconsistencies during the analysis, the answer of respondents who wrote 0 for all the languages in a situation was considered as if that situation did not apply to them (i.e., NA). Likewise, if a respondent left a blank cell, or wrote NA, in a row where other languages were given a score from 1 to 10, their response was interpreted as 0 for that specific cell. Answers that did not adhere to the instructions and could not be interpreted in any of the above-described ways were disregarded for the analysis.

Figure 1.

Example of the questionnaire’s language frequency matrix.

3.2. Participant Recruitment

The link to the questionnaire was distributed through targeted advertisement on the social media platforms of the Meta group, with a total of 908 link clicks and an average cost per click of EUR 0.25. Four different ads were created to target first-generation participants on the one hand and second-generation and above on the other. These were divided according to regional heritage into ads aimed at Spanish participants and ads aimed at participants from Hispanic America. The same visual was used per regional division across generations, but detailed targeting was different for all four ads.

For the first generation, the definition of the advertisement audience was straightforward, as the Meta platform allows the targeting of Brussels residents that had previously lived in specific countries. As such, the audience for the “First-generation Spanish” ad were Brussels residents that used to live in Spain, while the “First-generation Hispanic American” ad targeted Brussels residents that used to live in all the Hispanic American countries for which the platform allowed selection (detailed targeting was not available for expatriates from Panama, Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay, Costa Rica, and Ecuador, for which a general interest in the country was selected).

Options to target the second-or-above generation were less apparent, as previous residence in a Spanish-speaking country does not universally apply to the sub-sample. After considering the available alternatives, the audience was refined through localized interests for both regions in areas such as music, cuisine, media, sports, and travel. We recognize that the difference in targeting options across generations is not ideal for obtaining a balanced sample across generations, as it indeed generated a larger sub-sample of first-generation participants and may have selected more second-or-above generation participants that maintain some level of cultural connection with their roots. While the effects of these considerations were deemed affordable for the present study of an exploratory design, they should be taken into account for further research on the matter.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents and discusses the results gathered from the study. First, we will outline an overview of the participants, delineating some key demographic characteristics including the specific Spanish varieties represented in the sample (Section 4.1). Next, we will dive into participants’ linguistic repertoires (Section 4.2) and language practices (Section 4.3) in order to make inferences about the degree of language maintenance and language vitality within the communities more generally.

4.1. Overview of Participants

A total of 125 responses were collected. Participants were classified into first generation (1G), second generation (2G), or third generation or above (3G+) according to their answers regarding their and their family’s migration history, defined from the moment a respondent’s family left their Spanish-speaking country. Of 125 responses, 99 (79%) were from 1G participants, 16 (13%) from 2G, and 10 (8%) from 3G+. In terms of gender distribution, 55% of the sample identified as women, 44% as men, and 1% selected the “Other/Prefer not to disclose” option.

To gauge the dialectal richness of the language in the city, participants were also asked to identify their Spanish variety on the basis of self-identification, the distribution of which is overviewed in Table 1. Overall, there is a balance between Spanish and Hispanic American participants (48% and 52%, respectively). If we compare this with the figures of Spanish-speaking immigrants registered in Brussels (70% and 30%, respectively, see Section 2.3), we note how the participant recruitment method yielded an overrepresentation of Hispanic Americans compared with their proportional numbers in the city. This is probably related to the generational division of participants in the sample: Hispanic Americans represented 61% of 1G, yet only 12.5% of 2G, and 30% of 3G+. These lower numbers of Hispanic Americans for later generations are consistent with migration patterns in Brussels, since significant migration waves from across the Atlantic began roughly 20 years later than those from Spain. Intraregionally, most Spanish participants come from central and northern Spain and the Balearic Islands (36% of the whole sample), while the most represented Hispanic American varieties are those from Mexico and Guatemala (16%), followed by the Caribbean (8%). The presentation of such a rich dialectal landscape within our sample highlights the immense diversity of Spanish in the city and calls for future studies to acknowledge and further investigate this variation.

Table 1.

Distribution of Spanish varieties spoken by participants in the sample.

4.2. Language Repertoires

The data from this section and Section 4.3 come from participants’ self-reported measures. Potential biases inherent to this way of data collection should be considered while reading these sections as they may lead to a possible over- or underestimation of language use and proficiency. Nevertheless, self-reported measures are commonly used in language maintenance research, and they often show significant correlations with other level assessment methods (Marian et al., 2007; Kang & Kim, 2016; Ross, 1998).

As can be inferred from Table 1, everyone who completed the survey speaks Spanish, including all respondents from 2G and 3G+. This might attest to the high vitality of the Spanish language in the city, although considerations must be made for the size and balance of the sample, as well as for the possibility of selection bias involved, particularly for 2G and 3G+, as discussed in Section 3.2.

Nevertheless, further pointers of the language’s vitality come from the extent to which participants selected Spanish as their most dominant language. Table 2 reveals a decline in this respect throughout the generations, going from 87% for 1G, to 25% for 2G, and ultimately reaching 0% for 3G+. A less drastic drop is seen, however, when looking at participants who selected Spanish as either their most or second-to-most dominant language, a critical consideration given the high levels of multilingualism in the sample (see infra). These figures go up to 99% for 1G, 81% for 2G, and 60% for 3G+, averaging 94% for the entire sample. Such results are in line with the high levels of intergenerational transmission for other immigrant minority languages in the city (Janssens, 2018, p. 58; Extra & Yağmur, 2004, p. 358; Li et al., 2022).

Table 2.

Dominance ranking of Spanish in participants’ repertoires.

Looking at 1G, a small percentage of participants did not have Spanish as their most dominant language, but rather a co-official or regional minority language from Spain, such as Catalan (5 out 99 participants in 1G). A similarly small number of participants considered French (3 out of 99) or English (5 out of 99) as their most dominant language. Nonetheless, all participants selected Spanish as their first acquired language.

Particularly interesting is the sample’s high degree of multilingualism. All 125 participants speak at least two languages, and 60% of the sample speaks at least four, including 56% of 1G, 69% of 2G, and 80% of 3G+. Table 3 shows the number of speakers of French, Dutch, and English as the city’s main and most widely spoken languages, while Table 4 displays their mean self-reported level in each language.

Table 3.

Number of speakers per language.

Table 4.

Mean level of participants’ spoken languages per generation (from basic user score 1 to proficient user score 3).

As is expected in language maintenance scenarios, proficiency levels in Spanish decrease with each generation. Nevertheless, the difference is relatively small, and levels only drop from 3 in 1G to 2.73 in 3G+, reaching a score quite close to the highest self-reported proficiency level for the third-or-above generation. This relatively strong maintenance in proficiency is accompanied by a swift integration of the city’s majority languages. Levels in French, already above 2.5 for the 92% of 1G who speaks it, increase considerably for 2G (2.9 for 94%). Furthermore, apart from one 2G participant born abroad, the entirety of 2G and 3G+ speaks the language.

In addition to French as the dominant language of the city, co-official Dutch is also incorporated by the group relatively quickly, although to a lesser extent. Of all participants, 35% report having some proficiency in the language, including 29% of 1G (with a mean level of 1.91), 63% of 2G (with a mean level of 1.9), and 50% of 3G+ (with a mean level of 2.2). As was discussed in Section 2.3, the percentage of the Brussels population with a good-to-excellent knowledge of Dutch represents 22.3%. In our sample, the percentage of participants with a mean level of 2 or above is 19%. While recognizing the potential differences in terms of proficiency scales, these figures suggest that Hispanic communities do not fall far behind the general Brussels population in terms of Dutch proficiency.

Regional comparisons between Spaniards and Hispanic Americans for 1G, however, do point to a notable difference. While the results showed that a higher percentage of French speakers came from Spain than from Hispanic America (with a difference of 9 percentage points), more Hispanic Americans reported speaking Dutch compared to their Spanish counterparts (with a difference of 14.5 percentage points). This difference for Dutch is remarkable and merits further investigation, although we can hypothesize that it is linked to the widespread perception of Dutch-medium education as a pathway for upward social mobility (Verlot & Delrue, 2004). In any case, it does present a contrast from previous studies indicating an occasional reluctance to learn Dutch from Latin American immigrants in Brussels (Garzón, 2014).

Finally, further attesting the sample’s degree of multilingualism, all but three participants (98%) reported speaking English with a mean level of 2.87, the highest after Spanish. Moreover, 45% of the participants indicated they speak a language other than the ones discussed so far. Relevant among these are Italian (21 participants; 17%), Portuguese (19 participants; 15%), Catalan (14 participants; 11%), and German (9 participants; 7%).

Most language maintenance studies have been conducted on heritage contexts where there is a single majority language. As such, very little is known about the implications of individual and societal multilingualism for heritage language maintenance and vitality. In their study of Chinese heritage maintenance, Li et al. (2022) suggest that conflicts between majority languages in a competitive multilingual ecology such as Brussels may mitigate the pressure on language minorities, subtly fostering heritage language maintenance. The results above support this theory in the case of Spanish in Brussels, advocating for broader research on the matter.

4.3. Language Practices

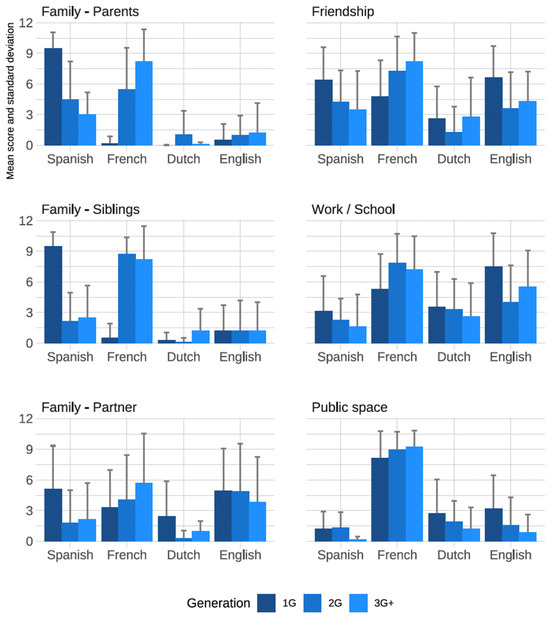

To achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the vitality of Spanish as an IML in Brussels, participants were also queried about their language practices in the family, friendship, work/school, and public space domains. Figure 2 presents a summary of their language use scores in Spanish, French, Dutch, and English on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means that the language is never used and 10 means that it is always used.

Figure 2.

Mean frequency rates for language use across domains.

In the family domain, different values were gathered per interlocutor. With parents, while Spanish use decreases gradually throughout the generations, the use of French increases: mean frequency rates for Spanish go from 9.48 in 1G to 3.05 in 3G+, while French goes from 0.2 to 8.2. A starker generational change is seen in language practices with siblings, where Spanish use drops from 9.51 in 1G to 2.17 in 2G, while French use grows from 0.51 to 8.73, respectively. Finally, with partners, unlike with other interlocutors in the domain, Spanish is limited to moderate use already from 1G, with a value of 5.1. Examining the makeup of couples in the sample, we observed an overwhelming presence of exogamy: 77% of participants overall had non-Hispanic partners, ranging from 75% in 1G to 86% in 3G+. This explains the lower frequencies of Spanish with partners and the further usage of other languages: French use rises gradually from 3.29 in 1G to 5.71 in 3G+, while English maintains a relatively steady frequency around 5 for 1G and 2G with a small drop to 3.86 for 3G+. Nevertheless, out of the 44 participants with children of speaking age in the sample, 39 (89%) have passed on the Spanish language to their offspring, including the entirety of first-generation parents (100%). Yet, the overall pattern in the family domain is that of Spanish use decreasing across generations, while use of French increases. Dutch is spoken comparatively little in this domain, as is English, except for communication with partners.

Among friends, 1G’s language use potentially reflects the international composition of their social circles. Spanish is used fairly often, with a mean rate of 6.39, while English emerges as the first generation’s most used language in the domain, with a rate of 6.64, and French remains not far behind with a rate of 4.79. The relatively similar frequencies between Spanish and English suggest that friendships are maintained both within the Hispanic communities and outside it for this generation, most likely using English as a contact language. Starting from 2G onwards, the use of French with friends goes up while the use of Spanish and English goes down, reaching a rate in 3G+ of 8.2, 3.5, and 4.3 in each language, respectively. The use of Dutch is also limited in the friendship domain, averaging a rate of 2.34 across generations.

For work and school, all generations rely mainly on English or French, with an emphasis on French for 2G and 3G+, with rates of 7.87 and 7.2, respectively, and on English for 1G, with a rate of 7.49 (although French is also used by this generation with moderate regularity, with a rate of 5.28). The overall use of Spanish in this domain is low, starting only at 3.16 for 1G and decreasing gradually to 1.6 for 3G+. Dutch, while still used fairly infrequently, exhibits its highest rates of use within the sample in the work and school domain, scoring higher than Spanish throughout the generations: 3.55 for 1G, 3.3 for 2G, and 2.6 for 3G+. While, overall, the use of the Dutch language across domains does not explain its relatively high numbers of speakers within the sample, the fact that work and school are the contexts in which the language is used the most can evoke a link between its acquisition and a search for further professional and educational opportunities.

Finally, the public space domain comprises rates given for language use at the market, in a shop, and at the doctor or in other health situations. Here, most of the sample relies mainly on French, averaging a frequency rate of 8.33 for all generations. Spanish is seldom used in these contexts, averaging only 1.13 across the sample. English and Dutch are also used infrequently (mean rate of 2.79 and 2.35, respectively), and their rates decrease throughout the generations as French usage goes up.

Overall, the pattern across domains is one of quick integration of French and a steady decline in Spanish use throughout the generations. The first generation maintains a close connection to Spanish, particularly in the family and friendship domain, using French, or occasionally English, for more formal or public contexts. By the second generation, Spanish in the family is reduced to occasional use, mainly with parents. Outside the family circle, participants from 2G seem to use Spanish with friends from time to time and only use it in very few occasions for other situations. Finally, the third-or-above generation rarely uses Spanish outside personal relationships yet still maintains a sporadic use with friends and family. While this use is low in comparison to the first and second generation, seen through the lens of Fishman’s three-generation model, it still shows a degree of language maintenance in this sample of the community. In other words, while our participants’ use of other languages exhibits a swift assimilation into Brussels’ society, this has not meant a complete loss of their heritage, and, contrary to theoretical predictions, they have been able to maintain the use of Spanish beyond the second generation. While the present study did not collect data to explore the reasons behind this maintenance, further research should investigate potential influencing factors, such as personal motivations, frequent travel to hispanophone destinations, regular influx of first-generation immigrants in the community, frequent interaction with other Spanish speakers, among others.

5. Conclusions

The present study was designed as a pilot to explore the circumstances around Spanish as an immigrant minority language in Brussels. Among the region’s diverse minorities, the city is home to sizable Hispanic communities, which have been growing since the second half of the 20th century, and which now represent approximately 6.4% of the population in terms of home language use. Nevertheless, Brussels’ already intricate linguistic landscape, where French and Dutch serve as co-official languages and English is increasingly used as a contact language, has meant that research on linguistic minorities has fallen behind, leaving the communicative patterns of communities, such as the Spanish-speaking one, largely unexamined (Verlot & Delrue, 2004).

In order to obtain a first overview of the language practices of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the city, an online survey was distributed via targeted social media advertisement, and a sample of 125 adult individuals with Hispanic heritage, living in the Brussels Metropolitan Area, was gathered. This method of participant recruitment was effective in terms of the gathering pace of respondents. Nevertheless, it proved to be significantly more efficient at targeting first-generation participants than generations beyond it, resulting in an unbalanced sample across migration generations. Future research should consider this disparity when investigating this or similar speech communities, either by refining advertisement targeting prompts or by mixing this approach with other means of participant engagement.

Despite this imbalance, the collected responses were deemed sufficient to provide general insights into the communities’ language practices and transmission, allowing for some careful and preliminary inferences regarding Spanish’s linguistic vitality in Brussels. The results unveil a highly multilingual and dialectally rich group with knowledge of at least four languages for most of the sample, including competence in Spanish for all 125 participants, regardless of their generation. This outcome challenges traditional language maintenance perspectives that focus solely on minority versus majority language dynamics and advocates for the study of minorities through a multilingual lens. Both linguistic repertoires and language use demonstrate a swift integration of the sampled group into Brussels society. Participants are quick to use French and/or English, the city’s most spoken languages, as needed. They are also relatively prompt to learn Dutch, more or less on par with the rest of Brussels’ population. Furthermore, their linguistic repertoires go beyond this immediate need for integration, with nearly half of the sample speaking a language other than the four mentioned above. These results meet the hypothesized outcomes for Spanish maintenance and use in the sample and surpass our expectations for proficiency in the city’s majority languages.

Such eagerness to accommodate to a context’s most fitting language does mean that Spanish becomes less used across generations. However, this has not resulted in a complete abandonment of the language by the third generation. While, for this group, Spanish seems to be relegated only to sporadic use among friends and family, the high levels of language competence reported (2.73 out of 3), as well as the fact that 60% consider Spanish one of their two most dominant languages, suggest that proficiency in the language has been preserved despite its reduced usage. Although we must take care not to overgeneralize our findings based on the limited sample, this linguistic retention makes sense for a group that embraces multilingualism as strongly as the studied sample seems to do.

Considering that language proficiency and language dominance represent two of the dimensions used by Extra and Yağmur (2004) to gauge language vitality, the results presented above can be taken as indicators of the group’s linguistic cohesion through its maintained connection to the language. Furthermore, the authors emphasize IMLs’ use at home, particularly with the mother, as an additional vitality dimension regarding language choice. Looking at our entire sample, Spanish use with parents had the highest mean frequency rate across situations and interlocutors (8.22), including an almost invariable use for the first generation and a moderately regular one for the second. A further, more large-scale investigation of these tendencies can provide more insight into the extent of Spanish’s vitality within Hispanic communities and its prevalence as a home language.

The combination of factors described above points to a group inclined toward language maintenance, with a potential for intergroup distinctiveness, but with a tendency for linguistic integration as well, at least within the sample studied. While the present study does not pretend to provide generalizable conclusions, it does intend to inform further research on Spanish as an IML in Brussels. By pointing to potential sociolinguistic phenomena that remain unexplored within the language group, such as its proclivity to multilingual adaptation, its rich dialectal makeup, and its likelihood to deviate from the three-generation model of language shift, the paper aims to highlight directions for further research on the language minority. Additional avenues for exploration include a focus on multilingual perspectives, both individual and societal. Such studies are particularly vital in Europe, where the absence of research in the area constitutes a significant gap in research on Spanish as minority language, and where the lack of academic attention to immigrant minority languages overlooks a crucial factor in understanding the linguistic makeup of multilingual cities in the continent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P.R., A.V.C. and R.V.; methodology, S.P.R., A.V.C. and R.V.; software, R.V.; validation, R.V.; formal analysis, S.P.R.; investigation, S.P.R.; resources, S.P.R.; data curation, S.P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.R.; writing—review and editing, S.P.R., A.V.C. and R.V.; visualization, R.V.; supervision, A.V.C. and R.V.; project administration, A.V.C. and R.V.; funding acquisition, S.P.R., A.V.C. and R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO), grant number 1111825N.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol of this study was submitted to the Ethical Committee for the Human Sciences (ECHW) of Vrije Universiteit Brussel on 6 November 2024. They reviewed the proposal and, on 22 November 2024, the Committee gave a positive recommendation for the study to be carried out.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated data presented in the study, as well as the R code used to generate the graph in Figure 2, are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14907379.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | For recent efforts to fill this research gap, see, for example, the series El español en Europa by Instituto Cervantes and the Center for Ibero-American Studies at Heidelberg University and the University of Zurich and the research projects on Spanish-speaking migration in Europe by the Observatorio Nebrija del Español. |

| 2 | This figure has as a point of reference the population of the Brussels-Capital Region. |

| 3 | See note 2. |

References

- Aalberse, S., Backus, A., & Muysken, P. (2019). Heritage languages: A language contact approach (Vol. 58). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, R. Y., Giles, H., & Rosenthal, D. (1981). Notes on the construction of a ‘subjective vitality questionnaire’ for ethnolinguistic groups. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 2(2), 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, R. Y., Sachdev, I., Ehala, M., & Giles, H. (2019). Assessing 40 years of group vitality research and future directions. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 38(4), 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, A., Bowden, J., McKinnon, T., Ravindranath, M., Simanjuntak, R., Taylor, B., & Yanti. (2013). Multilingual language use questionnaire. Available online: https://conf.ling.cornell.edu/pdfs/LangUseQuesF_copy.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Council of Europe. (2020). Common European framework of reference for languages: Companion volume. Council of Europe. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for-languages-learning-teaching/16809ea0d4 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Edwards, J. (2010). Minority languages and group identity: Cases and categories. John Benjamins Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Extra, G. (2011). 25 The immigrant minority languages of Europe. In B. Kortmann, & J. V. D. Auwera (Eds.), The languages and linguistics of Europe (pp. 467–482). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extra, G., & Gorter, D. (Eds.). (2001). The other languages of Europe: Demographic, sociolinguistic and educational perspectives. Multilingual Matters [u.a.]. [Google Scholar]

- Extra, G., & Yağmur, K. (2008). Mapping immigrant minority languages in multicultural cities. In M. Barni, & G. Extra (Eds.), Mapping linguistic diversity in multicultural contexts (pp. 139–162). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Extra, G., & Yağmur, K. (Eds.). (2004). Urban multilingualism in Europe: Immigrant minority languages at home and school. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J. (1966). Language loyalty in the United States: The maintenance and perpetuation of non-English mother tongues by American ethnic and religious groups. Mouton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J. (2001). 300-plus years of heritage language education in the United States. In J. K. Peyton, D. Ranard, & S. McGinnis (Eds.), Heritage languages in America: Preserving a national resource (pp. 81–98). National Conference on Heritage Languages in America, McHenry, Ill. Center for Applied Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, J. (1991). Reversing language shift. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlot, G., & Lucchini, S. (2019). Heritage & family languages in French-speaking Belgium: Issues of legitimacy and integration. Language Education and Multilingualism—The Langscape Journal, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, L. (2014, June 17). Latin American migrants in bilingual cities: A comparison between Barcelona and Brussels [Paper presentation]. XVIII World Congress of Sociology: Research Committee RC25 Language and Society, Yokohama, Japan. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264231614_Latin_American_migrants_in_bilingual_cities_a_comparison_between_Barcelona_and_Brussels (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Giles, H., Bourhis, R. Y., & Taylor, D. M. (1977). Towards a theory of language in ethnic group relations. In H. Giles (Ed.), Language, ethnicity and intergroup relations (pp. 307–348). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeke, I., Dekeyser, G. N. M., Caira, T., Agirdag, O., & Struys, E. (2022). Cherishing the heritage language: Predictors of parental heritage language maintenance efforts. International Journal of Bilingualism, 27(6), 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBSA (Institut Bruxellois de Statistique et d’Analyse). (2024). Population: Nationalités. Available online: https://ibsa.brussels/themes/population/nationalites (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- IBSA (Institut Bruxellois de Statistique et d’Analyse). (2025). Mini-Bru: La région de Bruxelles-Capitale en chiffres. Available online: https://ibsa.brussels/publications/mini-bru (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Instituto Cervantes (Ed.). (2024). El español en el mundo: Anuario del instituto cervantes, 2024. Instituto Cervantes. [Google Scholar]

- Irizarri van Suchtelen, P. (2016). Spanish as a heritage language in the Netherlands: A cognitive linguistic exploration. LOT, Netherlands Graduate School. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, R. (2018). Meertaligheid als opdracht: Een analyse van de Brusselse taalsituatie op basis van taalbarometer 4. Uitgeverij VUBPRESS. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, M. Á., Segura-Robles, A., & Rico-Martín, A. M. (2023). Heritage and minority languages, and their learning: A general bibliometric approach and content analysis. Training, Language and Culture, 7(1), 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-S., & Kim, I. (2016). Heritage language self-assessment: The role of cultural identity and language domain. Korean Journal of Applied Linguistics, 32(3), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Vosters, R., & Xu, J. (2022). Language maintenance and shift in highly multilingual ecologies: A case study of the Chinese communities in Brussels. Journal of Chinese Overseas, 18(1), 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriato, S. (2019). Language use and intergenerational transmission of heritage Veneto in the rural area of Santa Teresa, Brazil. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2019(260), 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureda Lamas, Ó. (2023). El español de Europa hoy: Dinámicas sociales, espacios lingüísticos y bases para la actuación política. In C. Román, & J. J. González (Eds.), Informe sobre el estado de la cultura en España 2023: La presencia cultural de España en Europa (pp. 17–36). Fundación Alternativas. [Google Scholar]

- Loureda Lamas, Ó., Moreno-Fernández, F., & Álvarez Mella, H. (2023). Spanish as a heritage language in Europe: A demolinguistic perspective. Journal of World Languages, 9(1), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, V., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). The language experience and proficiency questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50(4), 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, M. D. (1996). Spanish language maintenance and shift in Australia. The Australian National University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olko, J. (2024). Ethnolinguistic vitality, multilingual communication and speakers of contested languages. In E. Nshom, & S. Croucher (Eds.), Research handbook on communication and prejudice (pp. 104–138). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, A. (2016). Language maintenance and shift (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, M. (2023). Some remarks on Spanish in the bilingual world. Journal of World Languages, 9(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. (1998). Self-assessment in second language testing: A meta-analysis and analysis of experiential factors. Language Testing, 15(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J. (2009). Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeys, M. (2024). Taalbarometer 5: Factsheet. VUB-BRIO. Available online: https://www.briobrussel.be/node/19094 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Sáenz, R., & Salazar, I. (2007). Realidad y sueño latinoamericano en Bélgica. In I. Yépez del Castillo, & G. Herrera (Eds.), Nuevas migraciones latinoamericanas a Europa: Balances y desafíos (pp. 167–188). FLACSO-Ecuador [u.a.]. [Google Scholar]

- Statbel. (2024). Diversity according to origin in Belgium. Federal Public Service Economy. Available online: https://statbel.fgov.be/en/news/diversity-according-origin-belgium-2 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Szpiech, R., Shapero, J., Coetzee, A. W., García-Amaya, L., Alberto, P., Langland, V., Johandes, E., & Henriksen, N. (2020). Afrikaans in Patagonia: Language shift and cultural integration in a rural immigrant community. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2020(266), 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages. (2003, March 10–12). Language vitality and endangerment. International Expert Meeting on UNESCO Programme Safeguarding of Endangered Languages, Paris, France. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183699 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Van der Avoird, T., Broeder, P., & Extra, G. (2001). Immigrant Minority Languages in the Netherlands. In G. Extra (Ed.), The other languages of Europe: Demographic, sociolinguistic and educational perspectives (pp. 215–242). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mensel, L. (2016). Children and choices: The effect of macro language policy on the individual agency of transnational parents in Brussels. Language Policy, 15(4), 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlot, M., & Delrue, K. (2004). 10. Multilingualism in Brussels. In G. Extra, & K. Yagmur (Eds.), Urban multilingualism in Europe (pp. 221–250). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, D. J., & Rivera-Mills, S. (2009). An integrated multi-generational model for language maintenance and shift: The case of Spanish in the Southwest. Spanish in Context, 6(1), 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).