Impact of Speaker Accent and Listener Background on FL Learners’ Perceptions of Regional Italian Varieties

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Measuring FL Learners’ Perceptions of Regionally Accented Speech

1.2. Listener Factors

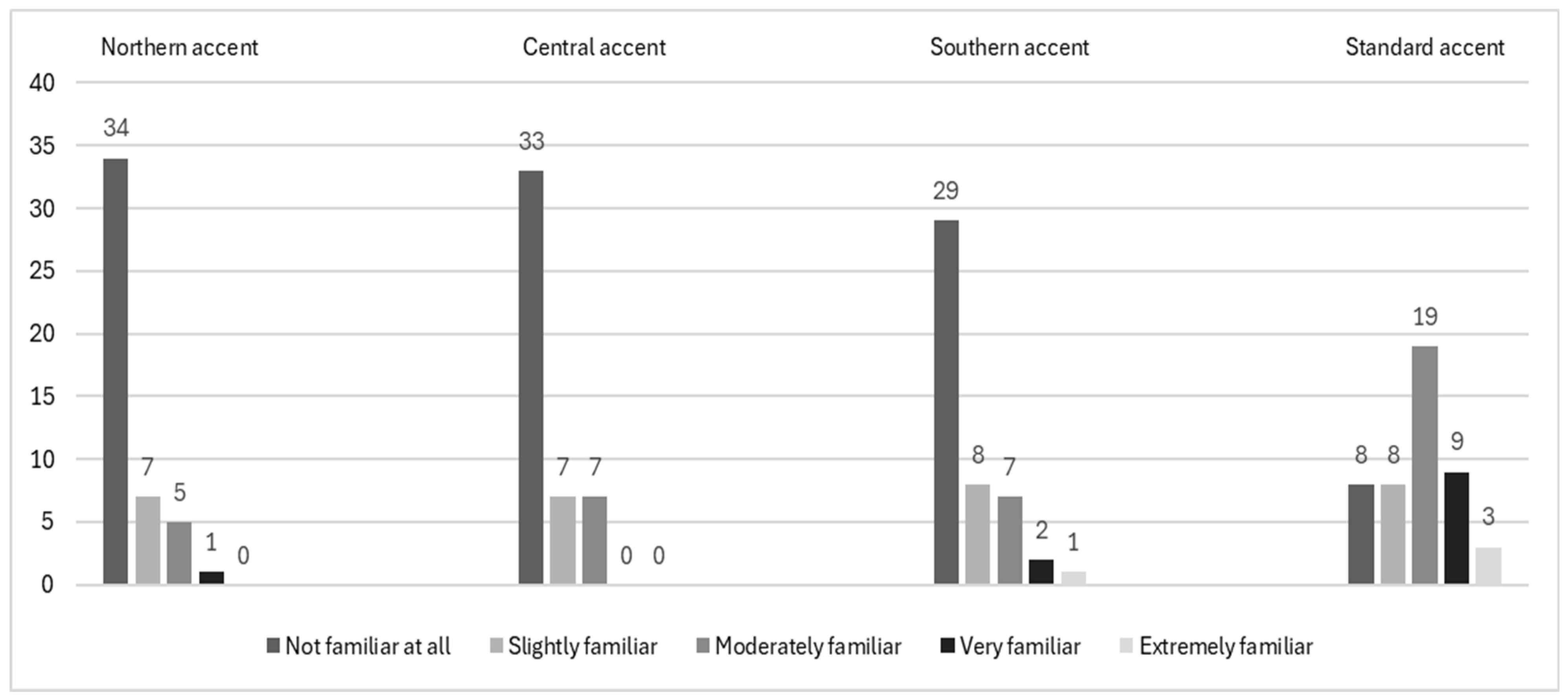

1.2.1. Accent Familiarity

1.2.2. Contact with Target Language Users

1.2.3. Heritage Language Learner Status

1.2.4. L1 Background and Transfer

1.3. Speaker Factors

1.4. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Preparation and Analysis

3. Results

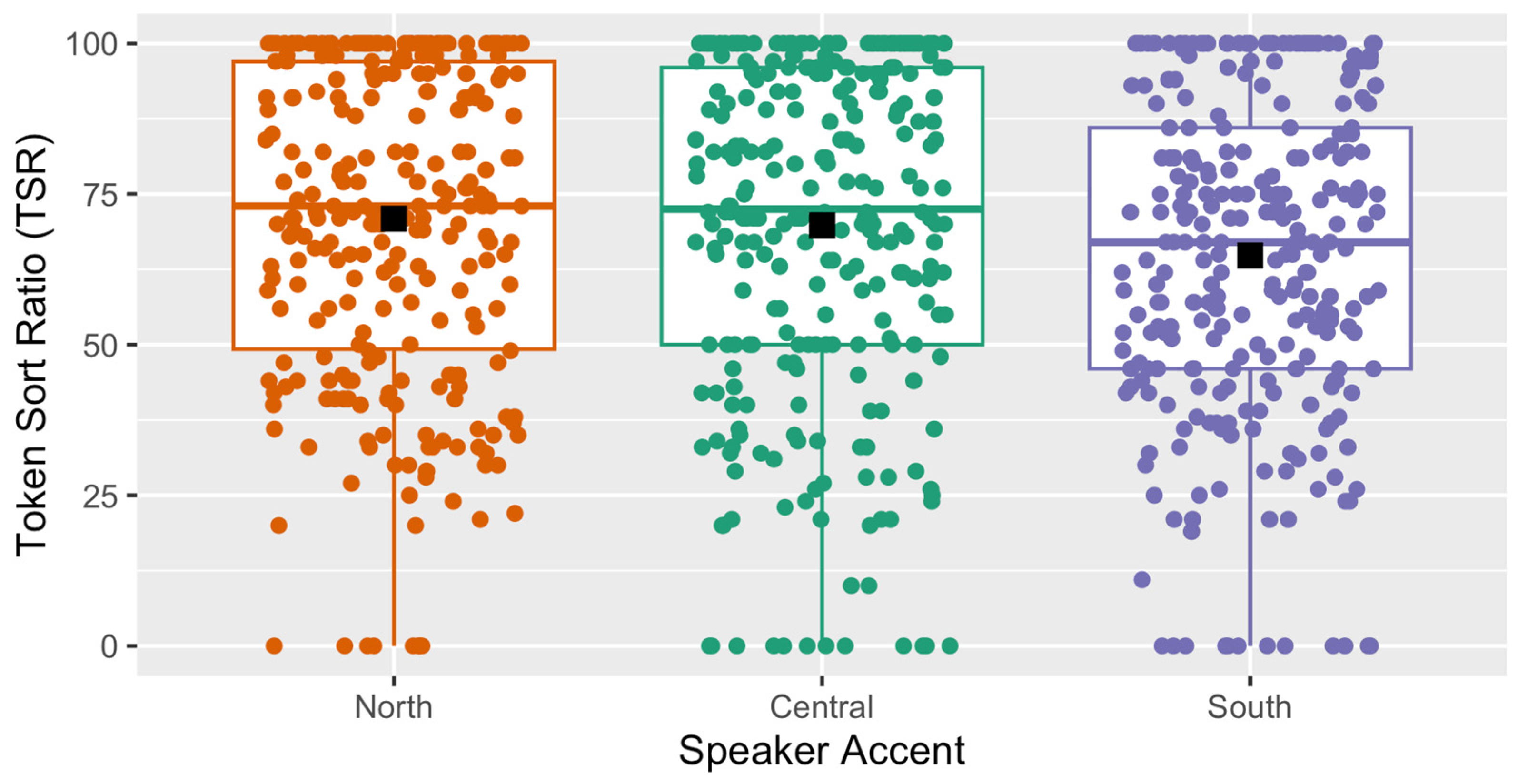

3.1. Intelligibility

3.2. Comprehensibility

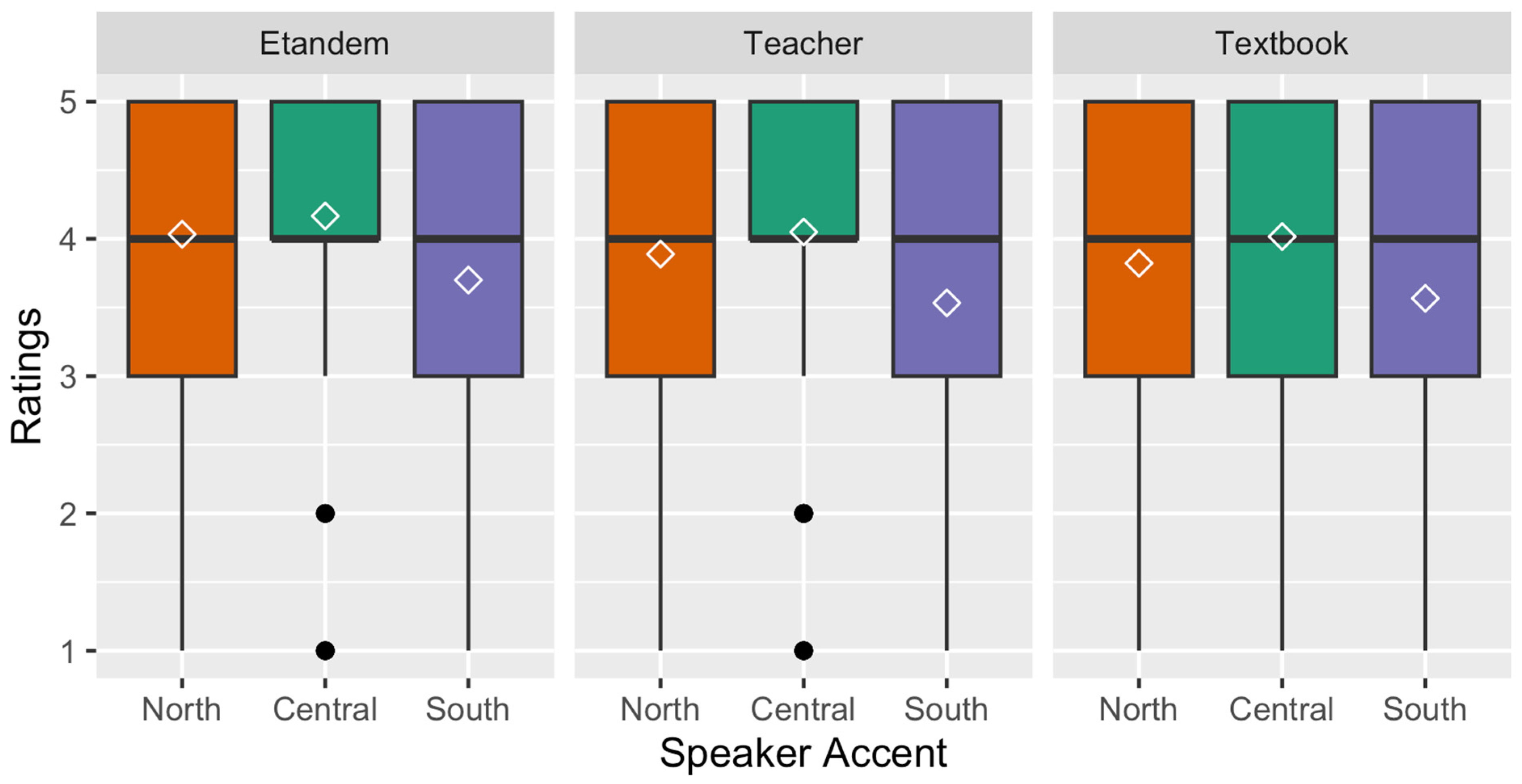

3.3. Acceptability

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | While the majority of HLLs have a lower proficiency level in their heritage language compared to the majority language, there is evidence of HLLs with native-like proficiency levels in both languages (Montrul, 2006). |

| 2 | This list of segmental features is not exhaustive but rather aimed at exemplifying some instances of regional variations in Italian language. For a complete list of phonological and phonetic features of Italian regional variations and a deeper understanding of the degree of linguistic variation in both vowels and consonants, we refer readers to Crocco (2017). |

| 3 | We are thankful to the anonymous reviewer who noted the importance of the generation of family connection for heritage learners. Although we can report anecdotally that the majority of heritage learners that we have encountered in IFL classes have been third-generation Italian learners, we did not ask participants in this study about their generational relationship to Italian as a heritage language and therefore cannot report more details on these family connections. We acknowledge this as a limitation to the present study. |

References

- Algethami, G., Ingram, J., & Nguyen, T. (2011). The interlanguage speech intelligibility benefit: The case of Arabic-accented English. In J. Levis, & K. LeVelle (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd pronunciation in second language learning and teaching conference (pp. 30–42). Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinhoff, B. (2014). What is “acceptable”? The role of acceptability in English non-native speech. In M. Solly, & E. Esch (Eds.), Language education and the challenges of globalisation: Sociolinguistic issues (pp. 155–174). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, T., & Bradlow, A. R. (2003). The interlanguage speech intelligibility benefit. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 114(3), 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfatti-Sabbioni, M. T. (2023). Auxiliary selection in heritage speakers of Italian. In F. B. Romano (Ed.), Studies in Italian as a heritage language (pp. 127–154). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosker, H. R. (2021). Using fuzzy string matching for automated assessment of listener transcripts in speech intelligibility studies. Behavior Research Methods, 53, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, K., & Fulcher, G. (2017). Pronunciation and intelligibility in assessing spoken fluency. In T. Isaacs, & P. Trofimovich (Eds.), Second language pronunciation assessment: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 37–53). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Carneglutti, E., Tomasino, B., & Fabbro, F. (2022). Effects of linguistic distance on second language brain activations in bilinguals: An exploratory coordinate-based meta-analysis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 744489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A. C.-S. (2009). Gains to L2 listeners from reading while listening versus listening only in comprehending short stories. System, 37(4), 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C. M., & Garrett, M. F. (2004). Rapid adaptation to foreign-accented English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 116(6), 3647–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocco, C. (2017). Everyone has an accent. Standard Italian and regional pronunciation. In M. Cerruti, C. Crocco, & S. Marzo (Eds.), Towards a new standard: Theoretical and empirical studies on the restandardization of Italian (pp. 89–117). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, D., Isbell, D. R., & Nishizawa, H. (2023). Second language speech comprehensibility and acceptability in academic settings: Listener perceptions and speech stream influences. Applied Psycholinguistics, 44(5), 858–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrì, A. (2016). Le varietà dell’italiano in alcuni manuali per stranieri diffusi all’estero. Italiano LinguaDue, 8(1), 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalman, M., & Kang, O. (2023). Validity evidence: Undergraduate students’ perceptions of TOEFL iBT high score spoken responses. International Journal of Listening, 37(2), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fina, A. (2014). Language and identities in US communities of Italian origin. Forum Italicum, 48(2), 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iacovo, V., & Mairano, P. (2024). The effects of regional Italian prosodic variation on modality identification by L1 English learners. Proceedings of Speech Prosody, 2024, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazzi, G., & Hajek, J. (2021). Italian language learning and student motivation at Australian universities. Italian Studies, 76(4), 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, T. (in preparation). Motivation and L2 selves of university students of Italian in the United States [Manuscript in preparation]. Department of World Languages, University of South Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Floccia, C., Butler, J., Goslin, J., & Ellis, L. (2009). Regional and foreign accent processing in English: Can listeners adapt? Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 38(4), 379–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gili Fivela, B., Avesani, C., Barone, M., Bocci, G., Crocco, C., D’Imperio, M., & Sorianello, P. (2015). Intonational phonology of the regional varieties of Italian. In S. Frota, & P. Prieto (Eds.), Intonation in romance (pp. 140–197). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen Edwards, J. G., Zampini, M. L., & Cunningham, C. (2018). The accentedness, comprehensibility, and intelligibility of Asian Englishes. World Englishes, 37(4), 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes-Harb, R., Smith, B. L., Bent, T., & Bradlow, A. R. (2008). The interlanguage speech intelligibility benefit for native speakers of Mandarin: Production and perception of English word-final voicing contrasts. Journal of Phonetics, 36(4), 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B., Alegre, A., & Eisenberg, A. (2016). A cross-linguistic investigation of the effect of raters’ accent familiarity on speaking assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 13(1), 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O. (2010). Relative salience of suprasegmental features on judgments of L2 comprehensibility and accentedness. System, 38, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O., Ahn, H., Yaw, K., & Chung, S.-Y. (2021). Investigation of relationships among learner background, linguistic progression, and score gain on IELTS. IELTS Research Reports Online Series, No. 1. British Council, Cambridge Assessment English and IDP: IELTS Australia. Available online: https://ielts.org/researchers/our-research/research-reports/investigation-of-relationships-between-learner-background-linguistic-progression-and-score-gain-on-ielts (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Kang, O., Rubin, D., & Kermad, A. (2019a). The effect of training and rater differences on oral proficiency assessment. Language Testing, 36(4), 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O., Rubin, D., & Pickering, L. (2010). Suprasegmental measures of accentedness and judgments of language learner proficiency in oral English. The Modern Language Journal, 94(4), 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, O., Thomson, R., & Moran, M. (2019b). The effects of international accents and shared first language on listening comprehension tests. TESOL Quarterly, 53(1), 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, R. E., & Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H., & O’Brien, M. G. (2014). Perceptual dialectology in second language learners of German. System, 46, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiden, M. (1995). A linguistic history of Italian. Longman. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, R. C., Fitzmaurice, S. M., Bunta, F., & Balasubramanian, C. (2005). Testing the effects of regional, ethnic, and international dialects of English on listening comprehension. Language Learning, 55(1), 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, C. (2023). Migration, language, and variation: The challenge of foreign speakers to detect Italian linguistic varieties. Quaderns d’Italià, 28, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y., & Kang, O. (2023). An empirical approach to measuring accent familiarity: Phonological and correlational analyses. System, 116, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2006). On the bilingual competence of Spanish heritage speakers: Syntax, lexical-semantics and processing. International Journal of Bilingualism, 10(1), 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2010). Current issues in heritage language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, M. J. (2008). Foreign accent and speech intelligibility. In J. G. Hansen Edwards, & M. L. Zampini (Eds.), Phonology and second language acquisition (pp. 193–218). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning, 45(1), 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C., Krzyski, I., Lewandowska, H., & Wrembel, M. (2021). Multilingual learners’ perceptions of cross-linguistic distances: A proposal for a visual pscyhotopological measure. Language Awareness, 30(2), 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockey, G., & French, R. (2016). From one to multiple accents on a test of L2 listening comprehension. Applied Linguistics, 37(5), 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L. (2020). The study of heritage language development from a bilingualism and social justice perspective. Language Learning, 70, 15–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2011). Reanalysis in adult heritage language: New evidence in support of attrition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 33(2), 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, D. R. (2013). Linguistic insecurity forty years later. Journal of English Linguistics, 41(4), 304–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Reynolds, R. R., Howard, K. M., & Deák, J. (2009). Heritage language learners in first-year foreign language courses: A report of general data across learner subtypes. Foreign Language Annals, 42(2), 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbioni, M. T. B. (2018). Italian as heritage language spoken in the US [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/italian-as-heritage-language-spoken-us/docview/2108648178/se-2 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Saito, K., Tran, M., Suzukida, Y., Sun, H., Magne, V., & Ilkan, M. (2019). How do L2 listeners perceive the comprehensibility of foreign-accented speech? Roles of L1 profiles, L2 proficiency, age, experience, familiarity and metacognition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41(5), 1133–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, M. (2012). The intonation of polar questions in Italian: Where is the rise? Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 42(1), 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L. B., & Geeslin, K. L. (2022). Developing language attitudes in a second language: Learner perceptions of regional varieties of Spanish. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics, 35(1), 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonmaker-Gates, E. (2017). Regional variation in the language classroom and beyond: Mapping learners’ developing dialectal competence. Foreign Language Annals, 50(1), 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonmaker-Gates, E. (2018). Dialect comprehension and identification in L2 Spanish: Familiarity and type of exposure. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics, 11(1), 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staggs, C., Baese-Berk, M., & Nagle, C. (2022). The influence of social information on speech intelligibility within the Spanish heritage community. Languages, 7(3), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollhans, S. (2020). Linguistic variation in language learning classrooms: Considering the role of regional variation and ‘non-standard’ varieties. In Languages, Society and Policy. MEITS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R. I. (2018). High variability [pronunciation] training (HVPT): A proven technique about which every language teacher and learner ought to know. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 4(2), 208–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, H., & Kang, O. (2022). Impact of L2 learners’ background factors on the perception of L1 Spanish speech. Foreign Language Annals, 55, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winke, P., & Gass, S. (2013). The influence of second language experience and accent familiarity on oral proficiency rating: A qualitative investigation. TESOL Quarterly, 47(4), 762–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winke, P., Gass, S., & Myford, C. (2013). Raters’ L2 background as a potential source of bias in rating oral performance. Language Testing, 30(2), 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteman, M. J., Bardhan, N. P., Weber, A., & McQueen, J. M. (2015). Automaticity and stability of adaptation to a foreign-accented speaker. Language and Speech, 58(2), 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteman, M. J., Weber, A., & McQueen, J. M. (2014). Tolerance for inconsistency in foreign-accented speech. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21(2), 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuensch, J., & Bolter, D. (2020). Is a Schtoan a Stein? How and why to teach dialects and regional variations in the German language classroom. German as a Foreign Language, 2020(2), 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yaw, K., & Ferronato, T. (2024, September 27–29). Pragmatic impact of Italian intonation on FL learners’ perceptions of statements and polar questions. 6th International Conference of the American Pragmatics Association, St. Petersburg, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Utterance | Prompt | Expected Response |

|---|---|---|

| Statement | Ti chiedono quale materia è facile. Guarda l’immagine e rispondi. | Una materia facile è l’inglese. |

| [They ask you what an easy subject is. Look at the picture and reply] | [An easy subject is English.] | |

| Polar question | Sei al telefono con tua mamma e state organizzando una cena con i parenti. Non hai ancora avuto conferma che i tuoi nipoti verranno. Chiedi a tua mamma se hanno detto di si. | Hanno detto di si? |

| [You are on the phone with your mum and planning a dinner with some relatives. Your nephews haven’t confirmed their presence yet. Ask your mum if they said yes.] | [Did they say yes?] |

| Prompts |

|---|

| Cosa ti piace fare nel tempo libero? [What do you like to do in your free time?] |

| Descrivimi la tua vacanza ideale. Dove andresti e perchè? [Describe your dream vacation. Where would you go and why?] |

| Qual è stata la più grande avventura della tua vita finora? Raccontami cosa è successo e perché è stata un’avventura. [What has been your greatest life adventure so far? Tell me what happened, and why this was such an adventure.] |

| Quali consigli daresti ad una persona che visita l’Italia per la prima volta? [What advice would you have for someone who is visiting Italy for the first time?] |

| Category | Variable | Operationalization |

|---|---|---|

| Speaker | Accent | Regional accent (Northern, Central, Southern) |

| Listener | Familiarity | Reported degree of familiarity with regional accent of speaker, scale of 1 (not familiar) to 5 (extremely familiar) |

| Contact | Mean reported percentage of time in contact with Italian speakers in home and community, scale of 0–100% | |

| Heritage status | Reported heritage learner of Italian, binary (0 = no, 1 = yes) | |

| L1 | Reported L1, categorized into two groups—Romance (e.g., Spanish) and non-Romance (e.g., English) |

| Model | Code |

|---|---|

| Intelligibility | LMEM_intel <- lmer(Intel_TSR_score ~ Spkr_Accent + Familiarity + Contact + Heritage + L1 + (1|Listener), data = df) |

| Comprehensibility | LMEM_comp <- lmer(Comp ~ Spkr_Accent + Familiarity + Contact + Heritage + L1 + (1|Listener), data = df) |

| Acceptability—e-tandem | LMEM_accept_etandem <- lmer(Accept_etandem ~ Spkr_Accent + Familiarity + Contact + Heritage + L1 + (1|Listener), data = df) |

| Acceptability—FL teacher | LMEM_accept_FLteacher <- lmer(Accept_FLteacher ~ Spkr_Accent + Familiarity + Contact + Heritage + L1 + (1|Listener), data = df) |

| Acceptability—Textbook | LMEM_accept_textbook <- lmer(Accept_textbook ~ Spkr_Accent + Familiarity + Contact + Heritage + L1 + (1|Listener), data = df) |

| Dependent Variable | No Interaction | Partial Interaction | Full Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligibility | 7838.0 | 7851.3 | 7888.8 |

| Comprehensibility | 1600.2 | 1622.7 | 1646.1 |

| Acceptability—e-tandem | 1587.1 | 1599.1 | 1630.7 |

| Acceptability—FL teacher | 1634.6 | 1646.8 | 1678.9 |

| Acceptability—textbook | 1662.4 | 1674.6 | 1704.2 |

| Fixed Effect | Estimate | SE | df | t | p | Mar. R2 | Cond. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 65.606 | 3.940 | 81 | 16.652 | <0.001 *** | 0.086 | 0.321 |

| Speaker accent—Northern | 1.118 | 1.921 | 796 | 0.582 | 0.561 | ||

| Speaker accent—Southern | −4.956 | 1.952 | 804 | −2.539 | 0.011 * | ||

| Familiarity | −0.114 | 1.493 | 683 | −0.076 | 0.939 | ||

| Contact | 0.237 | 0.163 | 49 | 1.450 | 0.153 | ||

| Heritage | −2.096 | 4.434 | 43 | −0.473 | 0.639 | ||

| L1—Romance | 18.577 | 5.707 | 43 | 3.255 | 0.002 ** |

| Speaker Accent | Non-Romance L1 | Romance L1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emmean | SE | 95% CI | Emmean | SE | 95% CI | |

| Northern | 67.6 | 2.57 | [62.5, 72.8] | 86.2 | 5.35 | [75.4, 97] |

| Central | 66.5 | 2.57 | [61.4, 71.6] | 85.1 | 5.35 | [74.3, 95.8] |

| Southern | 61.6 | 2.58 | [56.4, 66.7] | 80.1 | 5.34 | [69.4, 90.9] |

| Fixed Effect | Estimate | SE | df | t | p | Mar. R2 | Cond. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 3.585 | 0.155 | 101 | 23.172 | <0.001 *** | 0.112 | 0.236 |

| Speaker accent—Northern | −0.268 | 0.103 | 492 | −2.617 | 0.009 ** | ||

| Speaker accent—Southern | −0.575 | 0.104 | 502 | −5.514 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Familiarity | −0.074 | 0.071 | 290 | −1.033 | 0.302 | ||

| Contact | 0.017 | 0.006 | 50 | 3.030 | 0.004 ** | ||

| Heritage | −0.062 | 0.152 | 41 | −0.406 | 0.687 | ||

| L1—Romance | 0.496 | 0.191 | 41 | 2.592 | 0.013 * |

| Speaker Accent | Non-Romance L1 | Romance L1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emmean | SE | 95% CI | Emmean | SE | 95% CI | |

| Northern | 3.33 | 0.099 | [3.13, 3.53] | 3.83 | 0.185 | [3.46, 4.2] |

| Central | 3.6 | 0.099 | [3.4, 3.8] | 4.09 | 0.185 | [3.72, 4.47] |

| Southern | 3.02 | 0.100 | [2.83, 3.22] | 3.52 | 0.184 | [3.15, 3.89] |

| Fixed Effect | Estimate | SE | df | t | p | Mar. R2 | Cond. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-tandem | 0.099 | 0.395 | |||||

| (Intercept) | 4.458 | 0.196 | 77 | 22.723 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Speaker accent—Northern | −0.134 | 0.098 | 492 | −1.373 | 0.170 | ||

| Speaker accent—Southern | −0.456 | 0.100 | 499 | −4.566 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Familiarity | −0.042 | 0.075 | 478 | −0.553 | 0.581 | ||

| Contact | 0.010 | 0.008 | 47 | 1.309 | 0.197 | ||

| Heritage | −0.665 | 0.221 | 41 | −3.008 | 0.004 ** | ||

| L1—Romance | −0.172 | 0.279 | 41 | −0.619 | 0.540 | ||

| Teacher | 0.078 | 0.391 | |||||

| (Intercept) | 4.311 | 0.208 | 76 | 20.752 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Speaker accent—Northern | −0.163 | 0.102 | 492 | −1.600 | 0.110 | ||

| Speaker accent—Southern | −0.492 | 0.104 | 498 | −4.722 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Familiarity | −0.094 | 0.079 | 484 | −1.194 | 0.233 | ||

| Contact | 0.010 | 0.008 | 47 | 1.195 | 0.238 | ||

| Heritage | −0.529 | 0.236 | 41 | −2.248 | 0.030 * | ||

| L1—Romance | 0.101 | 0.297 | 41 | 0.342 | 0.734 | ||

| Textbook | 0.065 | 0.368 | |||||

| (Intercept) | 4.249 | 0.209 | 77 | 20.322 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Speaker accent—Northern | −0.197 | 0.105 | 492 | −1.874 | 0.062 | ||

| Speaker accent—Southern | −0.424 | 0.107 | 499 | −3.965 | <0.001 *** | ||

| Familiarity | −0.096 | 0.081 | 475 | −1.187 | 0.236 | ||

| Contact | 0.009 | 0.008 | 47 | 1.100 | 0.277 | ||

| Heritage | −0.479 | 0.235 | 41 | −2.036 | 0.048 * | ||

| L1—Romance | 0.189 | 0.296 | 41 | 0.637 | 0.527 |

| Context Speaker Accent | Non-Heritage | Heritage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emmean | SE | 95% CI | Emmean | SE | 95% CI | |

| E-tandem | ||||||

| Northern | 4.27 | 0.17 | [3.93, 4.61] | 3.6 | 0.203 | [3.2, 4.01] |

| Central | 4.4 | 0.17 | [4.06, 4.74] | 3.74 | 0.203 | [3.33, 4.15] |

| Southern | 3.95 | 0.171 | [3.61, 4.29] | 3.28 | 0.203 | [2.87, 3.69] |

| Teacher | ||||||

| Northern | 4.15 | 0.18 | [3.78, 4.51] | 3.62 | 0.216 | [3.18, 4.05] |

| Central | 4.31 | 0.18 | [3.95, 4.67] | 3.78 | 0.216 | [3.35, 4.22] |

| Southern | 3.82 | 0.181 | [3.45, 4.18] | 3.29 | 0.215 | [2.86, 3.72] |

| Textbook | ||||||

| Northern | 4.09 | 0.181 | [3.72, 4.45] | 3.61 | 0.216 | [3.17, 4.04] |

| Central | 4.28 | 0.181 | [3.92, 4.65] | 3.8 | 0.216 | [3.37, 4.24] |

| Southern | 3.86 | 0.182 | [3.49, 4.22] | 3.38 | 0.216 | [2.95, 3.81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yaw, K.; Ferronato, T. Impact of Speaker Accent and Listener Background on FL Learners’ Perceptions of Regional Italian Varieties. Languages 2025, 10, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040083

Yaw K, Ferronato T. Impact of Speaker Accent and Listener Background on FL Learners’ Perceptions of Regional Italian Varieties. Languages. 2025; 10(4):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040083

Chicago/Turabian StyleYaw, Katherine, and Tania Ferronato. 2025. "Impact of Speaker Accent and Listener Background on FL Learners’ Perceptions of Regional Italian Varieties" Languages 10, no. 4: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040083

APA StyleYaw, K., & Ferronato, T. (2025). Impact of Speaker Accent and Listener Background on FL Learners’ Perceptions of Regional Italian Varieties. Languages, 10(4), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10040083