Reassessing the Learner Englishes–New Englishes Continuum: A Lexico-Grammatical Analysis of TAKE in Written and Spoken Englishes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. LEs-NEs Continuum and the EIF Model

3. Comparing NEs and LEs: Existing Corpus Research

- Does the positioning of the individual LEs and NEs along the continuum differ between written and spoken modes? Does this support the expected proximity cline to NativeE (BFE > MCE > HKE > SgE)?

- Does the positioning of the individual LEs and NEs along the continuum vary according to the valency patterns and senses of TAKE? Does this support the expected proximity cline to NativeE (BFE > MCE > HKE > SgE)?

- Are there shared non-standard features of valency patterns and senses of TAKE across LEs and NEs? What are the possible motivations for them?

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Corpus Data

4.2. Methods

- (1)

- B: I don’t know take care of him take take him out (NESSI-HK-025)

- (2)

- A: wha = what what are the differences between your . poly study experience and your university experienceB: I think . for one it was much easier to make friends in poly . because like my cohort in poly was really small . and we took like . my . basically I never changed classes the whole way the whole three years that we were there (NESSI-SIN-041)

- (3)

- They take television as an important part in daily life rather than a tool through which they can learn knowledge. (ICLE-CNUK-1122)

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Valency Patterns of TAKE Across Varieties and Modes

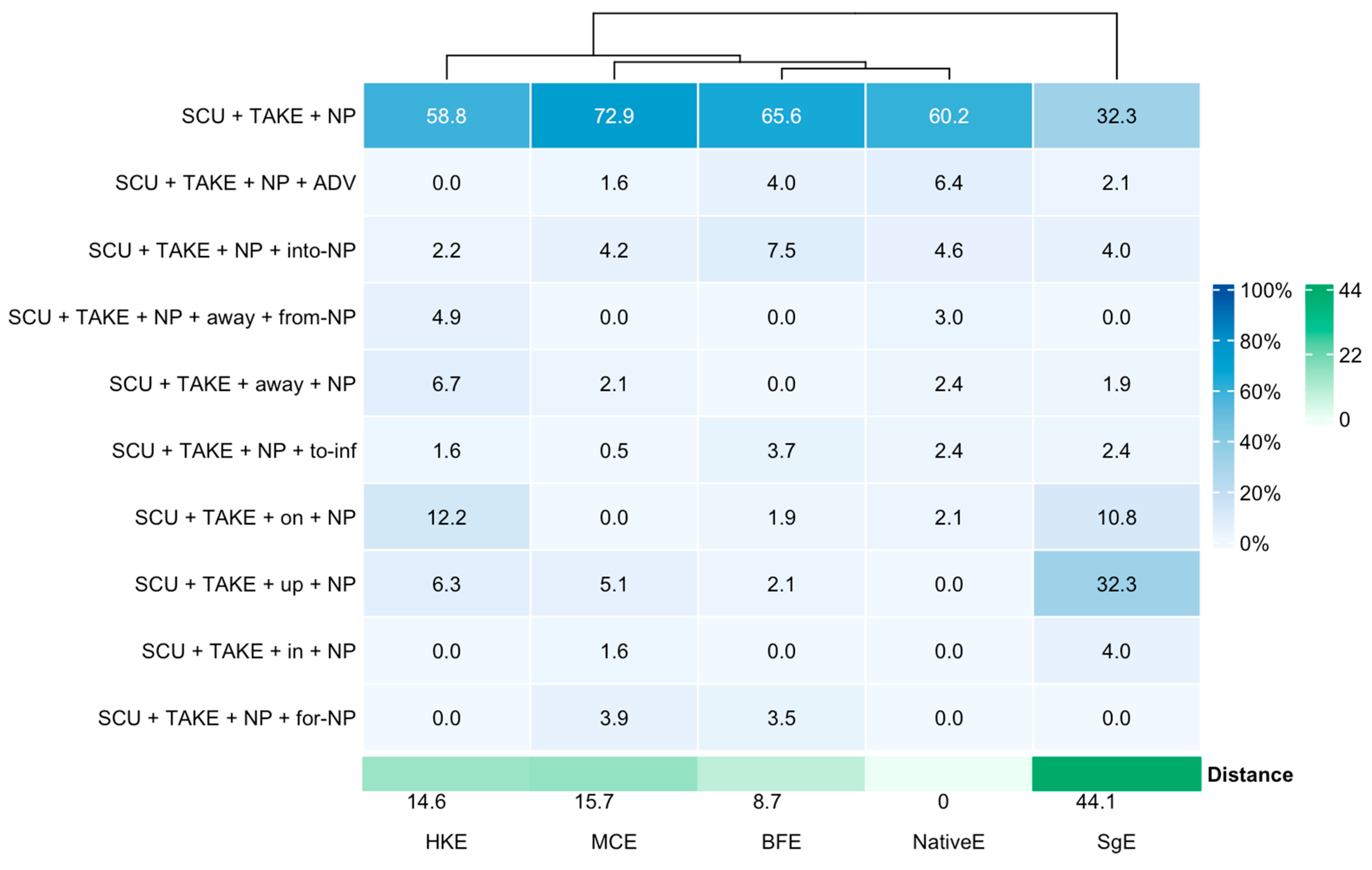

5.1.1. Valency Patterns of TAKE Across Varieties in Written Mode

- (4)

- We must now be able to take responsibility for this behavior. (LOCNESS-US-PRB-0035.2)

- (5)

- I think that when you have to take decisions, the support of people is needed. (ICLE-FRUL1008)

- (6)

- Therefore, it is good that college students take up a part-time job, but it is definitely not as important as the focus they should place on their studies. (ICNALE-SIN-WE_SIN_PTJ0_184_B1_2)

- (7)

- Above all, I think it is important for college students to take a part-time job. (ICNALE-MC_CHN_PTJ0_170_B1_2)

- (8)

- …this way of fragmenting the sentence does not correspond to the way the human brain takes in information. (ICE-SIN-W1A-006)

5.1.2. Valency Patterns of TAKE Across Varieties in Spoken Mode

- (9)

- It takes quite a long time to get out (LOCNEC-EN020)

- (10)

- Amy took a great deal of time to try and express what she had seen on television. (LOCNESS-US-MRQ-0034.1)

5.2. Senses of TAKE Across Varieties and Modes

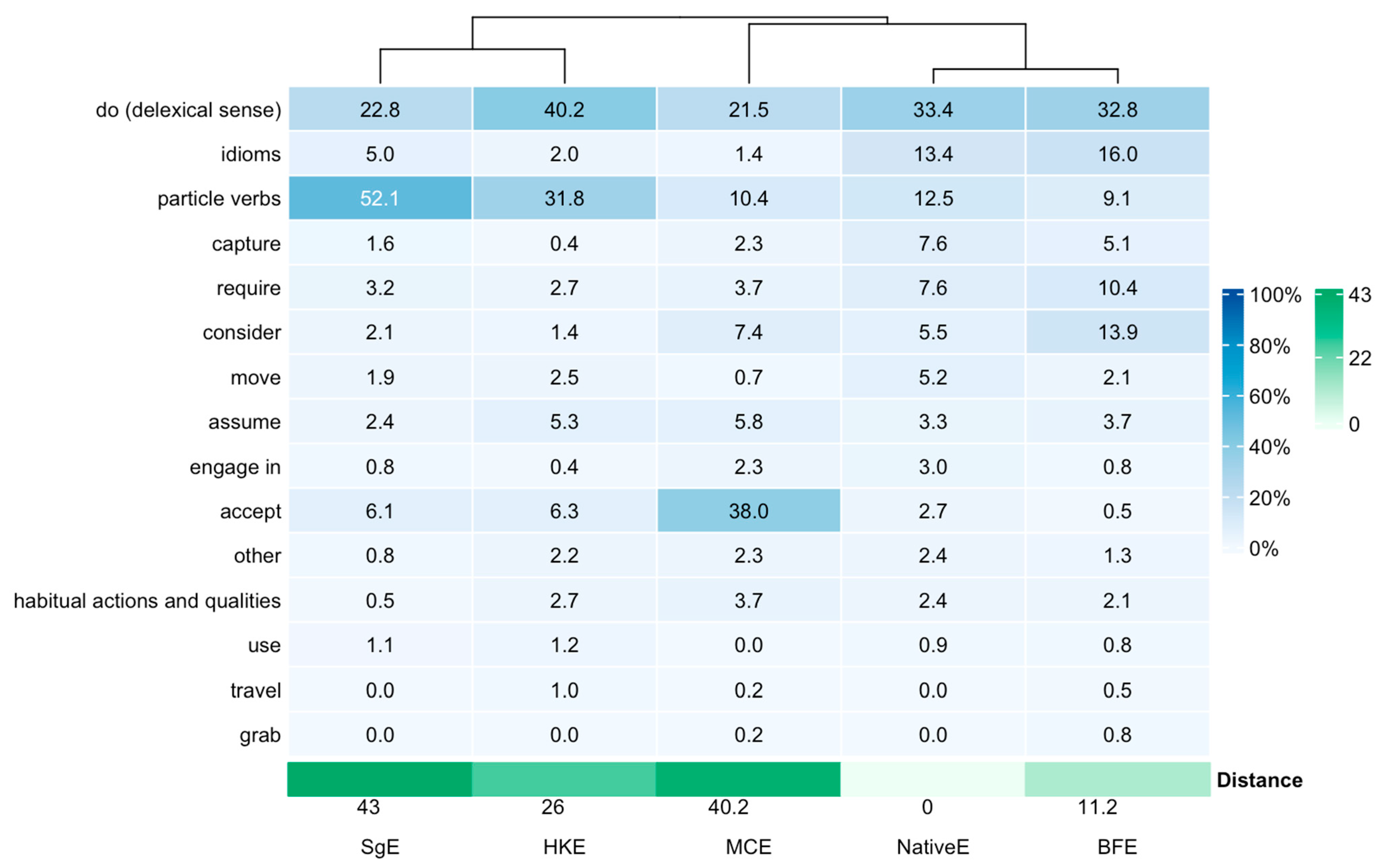

5.2.1. Senses of TAKE Across Varieties in Written Mode

- (11)

- He or she has taken the option of a non-marketplace, non-public and non-financially rewarded job. (LOCNESS-US-IND-0004.1)

- (12)

- However, having a co-curricular activity or taking up a leadership position in various groups can better enhance the students’ college life. (ICNALE-WE_SIN_PTJ0_004_B2_0)

- (13)

- Their struggles and hopes of forty years will not have been in vain—Without the “events of Berlin Wall” history probably would not have taken a very different course. (LOCNESS-US-MICH-0024.1) (sense: follow)

- (14)

- Here, I would like to recommend students to take a good habit to have a record for the use of credit card. (ICLE-CNHK1402) (sense: develop)

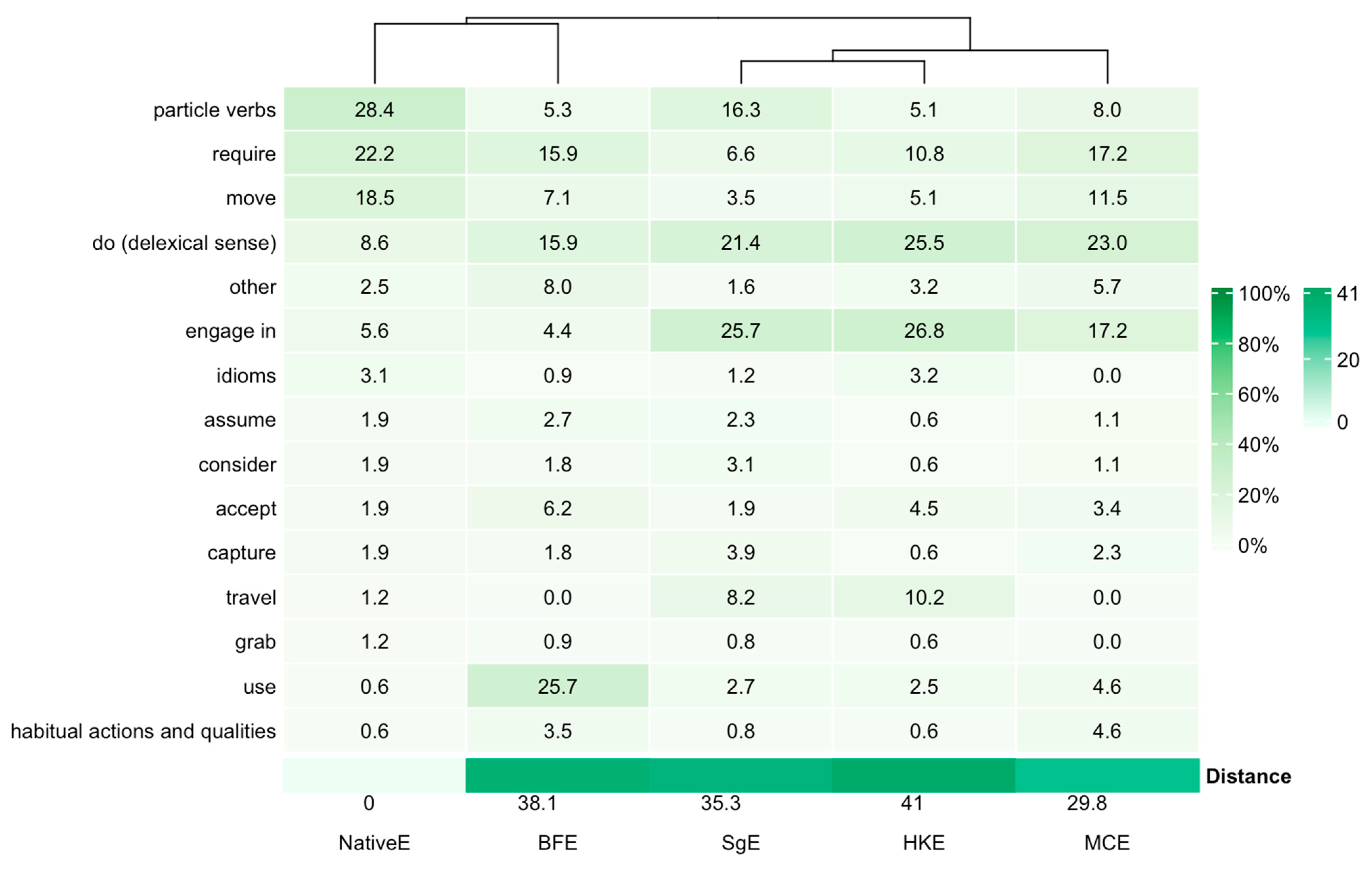

5.2.2. Senses of TAKE Across Varieties in Spoken Mode

5.3. Non-Standard Features of Valency Patterns and Senses of TAKE Across LEs and NEs

5.3.1. Non-Standard Features of Valency Patterns of TAKE Across LEs and NEs

Lexical Non-Standard Features

- (15)

- Laws should not be of a majoritarian model but take into consideration of the minority as well. (ICNALE-SIN-WE_SIN_SMK0_071_B2_0)

- (16)

- Taking into account of all these factors, we can safely draw a conclusion that university degrees are theoretical but necessary, nowadays. (ICLE-MC-CNUK1158)

- (17)

- In the following essay, the pros and cons of abortion will be discussed and the adoption of abortion will be taken in consideration. (ICLE-HK-CNHK1772)

- (18)

- However, when taken in account the effects of peer pressure, honor codes are weakened. (LOCNESS-US-MRQ-0044.1)

- (19)

- They: used to take me: away t= (er) to restaurants or: to parties and . (em) but the first time I went was when I was sixteen (LINDSEI-FR004)

- (20)

- In other words, college is the best time for them to fully live out their lives, before adult responsibilities set in and other priorities take precedent over their personal desires and needs. (ICNALE-SIN-WE_SIN_PTJ0_044_B2_0)

- (21)

- They can’t neglect the right of the babies. If they don’t want to have a baby parents should take careful of their behaviours. Abortion is not a way to solve the problem. (ICLE-HK-CNHK1322)

- (22)

- Some of the criminals are not mean to kill other people and they do want to have an opportunity to confess while take responsible of hurting others. (ICLE-MCE-CNUK1150)

Syntactic Non-Standard Features

- (23)

- We have a system where we each take turns cook. (LOCNESS-US-MICH-0043.1)

- (24)

- I was like this is what we’re going to talk about let’s try to be civil about everybody take turns hear each other out. (NESSI-SIN-033)

- (25)

- (mm) .. cos I know in Germany like you d = you can take years getting a degree because you can just keep going (LOCNEC-EN039)

- (26)

- To make Europe a nation is like to reassemble each piece of a jigsaw: it takes time doing it. (ICLE-FRUC1067)

- (27)

- It takes us much time working thus reduces our time for studying. (ICNALE-MC-W_CHN_PTJ0_295_B1_2)

5.3.2. Non-Standard Features of Senses of TAKE Across LEs and NEs

Metaphorical Extension

- (28)

- In other words, their identity will change a bit and take a European colour, but a loss of it is hardly conceivable. (ICLE-FRUC1075)

- (29)

- More graduate men also took brides of equal qualifications. (ICE-SIN-W1A-003)

- (30)

- I like comedies sometimes romantic movies (er) sometimes animations but one thing that I definitely do not like is horror or like bloody all the splatter (eh) I just c= I just can’t take it (NESSI-HK-046)

L1 Transfer

- (31)

- The mistakes in taking evidence, disproportionate treatment on the poor and minorities, corruptions in government and many other reasons will lead to the result of taking an innocent person’s life. (ICLE-CNUK1150)

- (32)

- Taking high score is the must important of all for a student in China because this is the warranty that others judge whether you are good or not. (ICLE-CNUK1183)

- (33)

- yes . but now I’m I can really (er) . enjoy my living here and I can (er) take a goo= I can have a good time in Louvain-la-Neuve and (er) (LINDSEI-FR-050)

Overgeneralization

- (34)

- Here, I would like to recommend students to take a good habit to have a record for the use of credit card. (→ develop) (ICLE-CNHK1402)

- (35)

- They also take the bills by their credit cards. (→ pay) (ICLE-CNHK1572)

- (36)

- Having a part-time job can take us more advantages than disadvantages. (→ bring) (ICLE-MC-W_CHN_PTJ0_234_B1_2)

- (37)

- I’ll take it into practice in my college years. (→ put) (ICNALE-MC-W_CHN_PTJ0_180_B1_2)

- (38)

- It may take a longterm effect to customers. (→ have) (ICLE-CNHK1380)

- (39)

- An illustration may take this point clear. (→ make) (ICLE-CNUK1143)

- (40)

- They have to take a new lease of life. (→ give) (ICLE-FRUC3087)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| NativeE | BFE | MCE | HKE | SgE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCU + TAKE + NP | 198 (#1) (60.2%) | 246 (#1) (65.6%) | 315 (#1) (72.9%) | 300 (#1) (58.8%) | 122 (#1) (32.3%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + ADV | 21 (#2) (6.4%) | 15 (#3) (4.0%) | 5 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.1%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + into-NP | 15 (#3) (4.6%) | 28 (#2) (7.5%) | 18 (#3) (4.2%) | 11 (2.2%) | 15 (#4) (4.0%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + away + from-NP | 10 (#4) (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (#5) (4.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| SCU + TAKE + away + NP | 8 (#5) (2.4%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (#5) (2.1%) | 34 (#3) (6.7%) | 7 (1.9%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + to-inf | 8 (2.4%) | 14 (#4) (3.7%) | 2 (0.5%) | 8 (1.6%) | 9 (2.4%) |

| SCU + TAKE + on + NP | 7 (2.1%) | 7 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | 62 (#2) (12.2%) | 41(#3) (10.8%) |

| SCU + TAKE + up + NP | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.1%) | 22 (#2) (5.1%) | 32 (#4) (6.3%) | 122 (#1) (32.3%) |

| SCU + TAKE + in + NP | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (#4) (4.0%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + for-NP | 0 (0%) | 13 (#5) (3.5%) | 17 (#4) (3.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cumulative % (top 5) | 76.6% | 84.3% | 88.2% | 88.9% | 83.4% |

| NativeE | BFE | MCE | HKE | SgE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCU + TAKE + NP | 77 (#1) (47.5%) | 89 (#1) (78.8%) | 64 (#1) (73.6%) | 129 (#1) (82.2%) | 184 (#1) (71.6%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + ADV | 13 (#2) (8.0%) | 3 (#3) (2.7%) | 3 (#3) (3.45%) | 7 (#2) (4.5%) | 12 (#3) (4.7%) |

| [it] + TAKE + NP + to-inf | 10 (#3) (6.2%) | 2 (#5) (1.8%) | 2 (#5) (2.3%) | 3 (#4) (1.9%) | 4 (1.6%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + out | 9 (#4) (5.6%) | 4 (#2) (3.5%) | 2 (2.3%) | 2 (1.3%) | 4 (1.6%) |

| SCU + TAKE + on + NP | 5 (#5) (3.1%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (#2) (5.8%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + to-inf | 4 (2.5%) | 4 (#2) (3.5%) | 3 (#3) (2.3%) | 2 (1.3%) | 4 (1.6%) |

| SCU + TAKE + NP + as-NP | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (#4) (2.7%) |

| SCU + TAKE + up + NP | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (#4) (1.9%) | 5 (#5) (2.0%) |

| [it] + TAKE + NP + for-NP + to-inf | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (#3) (3.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| [it] + TAKE + NP + NP + to-inf | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) | 4 (#2) (4.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cumulative % (top 5) | 69.5% | 90.3% | 87.4% | 93.6% | 86.8% |

| NativeE | BFE | MCE | HKE | SgE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| do (delexical sense) | 110 (#1) | 123 (#1) | 93 (#2) | 205 (#1) | 86 (#2) |

| (33.4%) | (32.8%) | (21.5%) | (40.2%) | (22.8%) | |

| idioms | 44 (#2) | 60 (#2) | 6 | 10 | 19 (#4) |

| (13.4%) | (16.0%) | (1.4%) | (2.0%) | (5.0%) | |

| particle verbs | 41 (#3) | 34 (#5) | 45 (#3) | 162 (#2) | 197 (#1) |

| (12.5%) | (9.1%) | (10.4%) | (31.8%) | (52.1%) | |

| capture | 25 (#4) | 19 | 10 | 2 | 6 |

| (7.6%) | (5.1%) | (2.3%) | (1.6%) | (0.4%) | |

| require | 25 (#4) | 39 (#4) | 16 | 14 (#5) | 12 (#5) |

| (7.6%) | (10.4%) | (3.7%) | (2.7%) | (3.2%) | |

| consider | 18 | 52 (#3) | 32 (#4) | 7 | 8 |

| (5.5%) | (13.9%) | (7.4%) | (1.4%) | (2.1%) | |

| move | 17 | 8 | 3 | 13 | 7 |

| (5.2%) | (2.1%) | (0.7%) | (2.5%) | (1.9%) | |

| assume | 11 | 14 | 25 (#5) | 27 (#4) | 9 |

| (3.3%) | (3.7%) | (5.8%) | (5.3%) | (2.4%) | |

| engage in | 10 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 3 |

| (3.0%) | (0.8%) | (2.3%) | (0.4%) | (0.8%) | |

| accept | 9 | 2 | 164 (#1) | 32 (#3) | 23 (#3) |

| (2.7%) | (0.5%) | (38.0%) | (6.3%) | (6.1%) | |

| habitual actions and qualities | 8 | 8 | 16 | 14 | 2 |

| (2.4%) | (2.1%) | (3.7%) | (2.7%) | (0.5%) | |

| use | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| (0.9%) | (0.8%) | (0.0%) | (1.2%) | (1.1%) | |

| travel | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| (0.0%) | (0.5%) | (0.2%) | (1.0%) | (0.0%) | |

| grab | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.0%) | (0.8%) | (0.2%) | (0.0%) | (0.0%) | |

| other | 8 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 3 |

| (2.4%) | (1.3%) | (2.3%) | (2.2%) | (0.8%) | |

| Cumulative % (top 5) | 74.5% | 82.2% | 83.1% | 86.3% | 89.2% |

| Total | 329 | 375 | 432 | 510 | 378 |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| NativeE | BFE | MCE | HKE | SgE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| particle verbs | 46 (#1) | 6 | 7 (#5) | 8 (#5) | 42 (#3) |

| (28.4%) | (5.3%) | (8.0%) | (5.1%) | (16.3%) | |

| require | 36 (#2) | 18 (#2) | 15 (#2) | 17 (#3) | 17 (#4) |

| (22.2%) | (15.9%) | (17.2%) | (10.8%) | (6.6%) | |

| move | 30 (#3) | 8 (#5) | 10 (#4) | 8 (#5) | 9 |

| (18.5%) | (7.1%) | (11.5%) | (5.1%) | (3.5%) | |

| do (delexical sense) | 14 (#4) | 18 (#2) | 20 (#1) | 40 (#2) | 55 (#2) |

| (8.6%) | (15.9%) | (23.0%) | (25.5%) | (21.4%) | |

| engage in | 9 (#5) | 5 | 15 (#2) | 42 (#1) | 66 (#1) |

| (5.6%) | (4.4%) | (17.2%) | (26.8%) | (25.7%) | |

| idioms | 5 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| (3.1%) | (0.9%) | (0.0%) | (3.2%) | (1.2%) | |

| assume | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| (1.9%) | (2.7%) | (1.1%) | (0.6%) | (2.3%) | |

| consider | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| (1.9%) | (1.8%) | (1.1%) | (0.6%) | (3.1%) | |

| accept | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| (1.9%) | (6.2%) | (3.4%) | (4.5%) | (1.9%) | |

| capture | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| (1.9%) | (1.8%) | (2.3%) | (0.6%) | (3.9%) | |

| travel | 2 | 0 | 0 | 16 (#4) | 21 (#4) |

| (1.2%) | (0.0%) | (0.0%) | (10.2%) | (8.2%) | |

| grab | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| (1.2%) | (0.9%) | (0.0%) | (0.6%) | (0.8%) | |

| use | 1 | 29 (#1) | 4 | 4 | 7 |

| (0.6%) | (25.7%) | (4.6%) | (2.5%) | (2.7%) | |

| habitual actions and qualities | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| (0.6%) | (3.5%) | (4.6%) | (0.6%) | (0.8%) | |

| other | 4 | 9 (#4) | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| (2.5%) | (8.0%) | (5.7%) | (3.2%) | (1.6%) | |

| Cumulative % (top 5) | 83.3% | 72.6% | 76.9% | 78.4% | 78.2% |

| Total | 162 | 113 | 87 | 157 | 257 |

| (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) | (100%) |

| 1 | In the literature, alternative terms like English as a second language (e.g., Gilquin & Granger, 2011), postcolonial Englishes (e.g., Schneider, 2007), indigenized varieties of English (e.g., Sridhar & Sridhar, 1986), to name a few, are used to refer to NEs, while English as a foreign language (e.g., Gilquin & Granger, 2011), performance varieties (e.g., Kachru, 1982), and non-postcolonial Englishes (e.g., Buschfeld et al., 2018) are used to refer to LEs. In this article, LEs and NEs are chosen because the parallel terminology enables systematic comparison while plural forms reflect the diversity of English varieties. |

| 2 | While English mass media and new communication technologies have created unprecedented opportunities for English exposure beyond classroom settings in LEs contexts, there might be a gap between availability and actual use of these resources. For instance, in mainland China, despite the availability of English mass media (e.g., China Daily) and English materials (e.g., English films and books), learners of English rarely exploit these resources (Wei & Su, 2012; Zheng, 2014). |

| 3 | This includes “Second-Language Varieties and Learner Englishes” at the First Conference of the International Society for the Linguistics of English in 2008 (Mukherjee & Hundt, 2011), “Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Innovations in Non-native Englishes” at the ICAME 36 conference in 2015 (Deshors et al., 2018), and “Global Englishes and SLA: Establishing a Dialogue and Common Research Agenda” at the American Association for Applied Linguistics conference in 2016 (Bolton & De Costa, 2018). |

| 4 | Despite the high comparability of these three corpora, one caveat to bear in mind is that they were collected at different times (see Gilquin, 2024, p. 5). For instance, LINDSEI-MC was compiled in 2001, while NESSI-HK was collected between 2016 and 2017. |

| 5 | For the full list of complement types, please refer to the VDE (Herbst et al., 2004). |

| 6 | SCU stands for subject complement unit. In the VDE, subjects are not specified in the valency patterns to maintain descriptive simplicity. For instance, the pattern of TAKE in (3) is described as + TAKE + NP + as-NP in the VDE. However, the subject will be represented to provide a more complete account of valency patterns in this study. Given the difficulty of identifying SCU in an unparsed corpus, valency patterns are usually presented in a reduced form (e.g., SCU + TAKE + NP) (see also Faulhaber, 2011). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | It shall be noted that this classification is not purely semantic, as categories such as particle verbs and other do not represent specific senses of TAKE. |

| 9 | The ComplexHeatmap package in R was used to generate these plots https://jokergoo.github.io/ComplexHeatmap-reference/book/index.html (accessed on 1 March 2025). |

| 10 |

References

- Algeo, J. (2006). British or American English? A handbook of word and grammar patterns. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P. (2017). American and British English: Divided by a common language? Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaisch, T., & Götz, S. (2021). Across three Kachruvian circles with two parts-of-speech: Nouns and verbs in ENL, ESL, and EFL varieties. In P. Peters, & K. Burridge (Eds.), Exploring the ecology of world Englishes in the twenty-first century: Language, society and culture (pp. 215–237). Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, D. (1991). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biewer, C. (2011). Modal auxiliaries in second language varieties of English: A learner’s perspective. In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 7–33). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, K. (2003). Chinese Englishes: A sociolinguistic history. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, K., & De Costa, P. I. (2018). World Englishes and second language acquisition: Introduction. World Englishes, 37(1), 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezina, V., Weill-Tessier, P., & McEnery, A. (2021). LancsBox v. 6. x. [software package]. Lancaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Buschfeld, S. (2013). English in Cyprus or Cyprus English: An empirical investigation of variety status. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Buschfeld, S., & Kautzsch, A. (2014). English in Namibia. English World-Wide, 35(2), 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S., & Kautzsch, A. (2017). Towards an integrated approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes. World Englishes, 36(1), 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschfeld, S., & Kautzsch, A. (Eds.). (2020). Modelling world Englishes: A joint approach to postcolonial and non-postcolonial varieties. Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buschfeld, S., Kautzsch, A., & Schneider, E. (2018). From colonial dynamism to current transnationalism: A unified view on postcolonial and non-postcolonial Englishes. In S. Deshors (Ed.), Modeling world Englishes: Assessing the interplay of emancipation and globalization of ESL varieties (pp. 15–44). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Callies, M. (2016). Towards a process-oriented approach to comparing EFL and ESL varieties: A corpus study of lexical innovations. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research, 2(2), 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, W. (2000). Explaining language change: An evolutionary approach. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Davydova, J. (2012). Englishes in the outer and expanding circles: A comparative study. World Englishes, 31(3), 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, J. (2019). Quotation in indigenised and learner English: A sociolinguistic account of variation. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- De Cock, S. (2004). Preferred sequences of words in NS and NNS speech. Belgian Journal of English Language and Literatures (BELL), New Series, 2, 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Deshors, S. C. (2014). A case for a unified treatment of EFL and ESL. English World-Wide. A Journal of Varieties of English, 35(3), 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshors, S. C., Götz, S., & Laporte, S. (Eds.). (2018). Rethinking linguistic creativity in non-native Englishes. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Deshors, S. C., & Gries, S. T. (2016). Profiling verb complementation constructions across new Englishes: A two-step random forests analysis of ing vs. to complements. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 21(2), 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessel, H. (2014). Usage-based linguistics. In M. Aronoff (Ed.), Oxford bibliographies in linguistics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2005). A semantic approach to English grammar. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, A. (2014). English in the Netherlands: Functions, forms and attitudes [Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Cambridge]. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, A., & Lange, R. J. (2016). In case of innovation: Academic phraseology in the three circles. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research, 2(2), 252–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A., & Laporte, S. (2015). Outer and expanding circle Englishes: The competing roles of norm orientation and proficiency levels. English World-Wide, 36(2), 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskildsen, S. W. (2009). Constructing another language—Usage-based linguistics in second language acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 30(3), 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulhaber, S. (2011). Verb valency patterns: A challenge for semantics-based accounts. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G. (2008). What you think ain’t what you get: Highly polysemous verbs in mind and language. In J.-R. Lapaire, G. Desagulier, & J.-B. Guignard (Eds.), Du fait grammatical au fait cognitif. From gram to mind: Grammar as cognition (Vol. 2, pp. 235–255). Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G. (2011). Corpus linguistics to bridge the gap between world Englishes and learner Englishes. In L. R. Miyares, & M. R. Á. Silva (Eds.), Comunicación Social en el siglo XXI (Vol. II, pp. 638–642). Centro de Lingüística Aplicada. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G. (2015a). At the interface of contact linguistics and second language acquisition research: New Englishes and Learner Englishes compared. English World-Wide, 36(1), 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilquin, G. (2015b). The use of phrasal verbs by French-speaking EFL learners. A constructional and collostructional corpus-based approach. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 11(1), 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilquin, G. (2016a). Input-dependent L2 acquisition: Causative constructions in English as a foreign and second language. In S. De Knop, & G. Gilquin (Eds.), Applied construction grammar (pp. 115–148). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G. (2016b). Discourse markers in L2 English: From classroom to naturalistic input. In O. Timofeeva, A.-C. Gardner, A. Honkapohja, & S. Chevalier (Eds.), New approaches to English linguistics: Building bridges (pp. 213–249). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G. (2024). Lexical use in spoken new Englishes and learner Englishes: The effects of shared and distinct communicative constraints. In B. Van Rooy, & H. Kotze (Eds.), Constraints on language variation and change in complex multilingual contact settings (pp. 120–152). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G. (2025). Second and foreign language learners: The effect of language exposure on the use of English phrasal verbs. International Journal of Bilingualism, 29(2), 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilquin, G., De Cock, S., & Granger, S. (2010). Louvain international database of spoken English interlanguage. Handbook and CD-ROM. Presses Universitaires de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G., & Granger, S. (2011). From EFL to ESL: Evidence from the international corpus of learner English. In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 55–78). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G., & Granger, S. (2021). The passive and the lexis-grammar interface: An inter-varietal perspective. In S. Granger (Ed.), Perspectives on the L2 phrasicon: The view from learner corpora (pp. 72–98). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Gilquin, G., & Meriläinen, L. (2024). Constrained communication in EFL and ESL: The case of embedded inversion. English World-Wide, 45(2), 196–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giparaitė, J. (2016). Complementation of light verb constructions in world Englishness: A corpus-based study. Žmogus ir Žodis, 18(3), 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlach, M. (2002). Still more Englishes. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Götz, S. (2015, August 8–9). Fluency in ENL, ESL and EFL: A corpus-based pilot study. Proceedings of Disfluency in Spontaneous Speech, DISS 2015, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Götz, S., & Schilk, M. (2011). Formulaic sequences in spoken ENL, ESL and EFL: Focus on British English, Indian English and learner English of advanced German learners. In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 79–100). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, S. (1998). The computer learner corpus: A versatile new source of data for SLA research. In S. Granger (Ed.), Learner English on computer (pp. 3–18). Addison Wesley Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, S., Dupont, M., Meunier, F., Naets, H., & Paquot, M. (2020). The international corpus of learner English (Version 3). Presses Universitaires de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum, S. (1988). A proposal for an international computerized corpus of English. World Englishes, 7(3), 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, S. T., & Deshors, S. C. (2015). EFL and/vs. ESL? A multi-level regression modeling perspective on bridging the paradigm gap. International Journal of Learner Corpus Research, 1(1), 130–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, P. (2013). Lexical analysis: Norms and exploitations. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselgren, A. (1994). Lexical teddy bears and advanced learners: A study into the ways Norwegian students cope with English vocabulary. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D., & Li, D. C. S. (2009). Language attitudes and linguistic features in the “China English” debate. World Englishes, 28(1), 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, T., Heath, D., Roe, I., & Götz, D. (2004). A valency dictionary of English: A corpus-based analysis of the complementation patterns of English verbs, nouns and adjectives. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, M. (2011). Interrogative inversion as a learner phenomenon in English contact varieties: A case of Angloverbals? In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and Learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 125–143). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, S. (2023). The ICNALE guide: An introduction to a learner corpus study on Asian learners’ L2 English. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B. B. (Ed.). (1982). Models for Non-Native Englishes. In The Other Tongue: English across Cultures (pp. 31–57). Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R. Quirk, & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures (pp. 11–30). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, S. (2012). Mind the gap! Bridge between world Englishes and learner Englishes in the making. English Text Construction, 5(2), 264–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, S. (2021). Corpora, constructions, new Englishes: A constructional and variationist approach to verb patterning. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, G. (2000). Grammars of spoken English: New outcomes of corpus-oriented research. Language Learning, 50(4), 675–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levshina, N. (2015). How to do linguistics with R. Data exploration and statistical analysis. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, E. T. K., & Shaw, P. M. (2001). Investigating learner vocabulary: A possible approach to looking at EFL/ESL learners’ qualitative knowledge of the word. IRAL—International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 39(3), 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenberg, P. H. (1986). Non-native varieties of English: Nativization, norms, and implications. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 8(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q., & Xu, Z. (2017). The nativization of English in China. In Z. Xu, D. He, & D. Deterding (Eds.), Researching Chinese English: The state of the art (pp. 189–201). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, L. (2017). The progressive form in learner Englishes: Examining variation across corpora. World Englishes, 36(4), 760–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, F. (2020). Status of English in Belgium. In S. Granger, M. Dupont, F. Meunier, H. Naets, & M. Paquot (Eds.), International corpus of learner English version 3 (pp. 180–185). Presses Universitaires de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Mežek, Š. (2024). English in Sweden: Functions, features and debates. World Englishes, 43(2), 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J., & Weinert, R. (1998). Spontaneous spoken language: Syntax and discourse. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, J., & Gries, S. T. (2009). Collostructional nativisation in new Englishes: Verb-construction associations in the international corpus of English. English World-Wide, 30(1), 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J., & Hoffmann, S. (2006). Describing verb-complementational profiles of new Englishes: A pilot study of IndE. English World-Wide, 27(2), 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J., & Hundt, M. (Eds.). (2011). Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselhauf, N. (2009). Co-selection phenomena across new Englishes: Parallels (and differences) to foreign learner varieties. English World-Wide, 30(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulasto, H., & Meriläinen, L. (2023). The processes of preposition omission across English variety types. In P. Rautionaho, H. Parviainen, M. Kaunisto, & A. Nurmi (Eds.), Social and regional variation in world Englishes: Local and global perspectives (pp. 91–122). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Percillier, M. (2016). World Englishes and second Language acquisition: Insights from southeast Asian Englishes. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2025). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Romasanta, R. P. (2020). Variation in the clausal complementation system in world Englishes: A corpus-based study of regret [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Universidade de Vigo]. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, E. W. (2004). How to trace structural nativization: Particle verbs in world Englishes. World Englishes, 23(2), 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E. W. (2007). Postcolonial English: Varieties around the world. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, E. W. (2012). Exploring the interface between world Englishes and second language acquisition—And implications for English as a lingua franca. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 1(1), 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E. W. (2014). New reflections on the evolutionary dynamics of world Englishes. World Englishes, 33(1), 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, K. K., & Sridhar, S. N. (1986). Bridging the paradigm gap: Second language acquisition theory and indigenized varieties of English. World Englishes, 5(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmrecsanyi, B., & Kortmann, B. (2011). Typological profiling: Learner Englishes versus indigenized L2 varieties of English. In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 167–207). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooy, B. (2011). A principled distinction between error and conventionalized innovation in African Englishes. In J. Mukherjee, & M. Hundt (Eds.), Exploring second-language varieties of English and learner Englishes: Bridging a paradigm gap (pp. 189–208). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. (2016). The idiom principle and L1 influence: A contrastive learner-corpus study of delexical verb + noun collocations. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, R., & Su, J. (2012). The statistics of English in China. English Today, 28(3), 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J., & Mukherjee, J. (2012). Highly polysemous verbs in new Englishes: A corpus-based study of Sri Lankan and Indian English. In S. Hoffmann, P. Rayson, & G. Leech (Eds.), Corpus linguistics: Looking back—Moving forward (pp. 249–266). Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. (1987). Non-native varieties of English: A special case of language acquisition. English World-Wide, 8(2), 161–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. (2010). Chinese English: Features and implications. Open University of Hong Kong Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q., & Jiang, J. (2020). Verb valency in interlanguage: An extension to valency theory and new perspective on L2 learning. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 56(2), 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. (2014). A phantom to kill: The challenges for Chinese learners to use English as a global language. English Today, 30(4), 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipp, L., & Bernaisch, T. (2012). Particle verbs across first and second language varieties of English. In M. Hundt, & U. Gut (Eds.), Mapping unity and diversity worldwide: Corpus-based studies of new Englishes (pp. 167–196). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

| Variety | Mode | Corpus | No. of Words | No. of TAKE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEs | MCE | Written | ICLE-MC + ICNALE-MC-stw | 150,130 | 432 |

| Spoken | LINDSEI-MC | 63,493 | 87 | ||

| BFE | Written | ICLE-FR | 194,025 | 375 | |

| Spoken | LINDSEI-FR | 90,999 | 113 | ||

| NEs | SgE | Written | ICE-SIN-stw + ICNALE-SIN-stw | 143,446 | 378 |

| Spoken | NESSI-SIN | 136,527 | 257 | ||

| HKE | Written | ICLE-HK | 384,016 | 510 | |

| Spoken | NESSI-HK | 113,912 | 157 | ||

| NativeE | AmE | Written | LOCNESS | 167,385 | 329 |

| BrE | Spoken | LOCNEC | 122,132 | 162 | |

| Total | 1,566,065 | 2800 |

| Senses | Examples |

|---|---|

| 1 Grab | So the artist (er) you know took his paintbrush… (NESSI-HK-009) |

| 2 Move | He was taken to the Tower of London… (LOCNEC-EN043) |

| 3 Habitual actions and qualities | But they are more likely to take a drug… (ICLE-CNHK1361) |

| 4 Require | It takes quite a long time to reach it. (ICLE-FRUC2009) |

| 5 Travel | Do you wanna take a taxi there. (NESSI-SIN-040) |

| 6 Engage in | The manager had an opportunity to take a computer class (ICLE-US-MICH-0002.1) |

| 7 Do (delexical sense) | They should not have to take part in a religion that… (LOCNESS-USMRQ0015.1) |

| 8 Capture | it started with the Romans trying to take Scotland… (LOCNEC- EN043) |

| 9 Consider | I took it as seriously as a film… (NESSI-SIN-021) |

| 10 Assume | I tend to take more leadership roles… (NESSI-SIN-028) |

| 11 Particle verbs | In conclusion, taking up part-time job… (ICNALE-WE_SIN_PTJ0_003_B1_2) |

| 12 Idioms | This action takes place in a number of different countries. (LOCNESS-US-PRB-0023.1) |

| 13 Accept | Another benefit to taking these jobs… (ICNALE-WE_SIN_PTJ0_046_B2_0) |

| 14 Use | The wealthy countries will take an opportunity to help… (ICLE- FRUC1076) |

| 15 Other | More graduate men also took brides of equal qualifications. (ICE-SIN-W1A-003) |

| Written | Spoken | |

|---|---|---|

| Expected | {BFE > MCE} > {HKE > SgE} | |

| Valency patterns | {HKE-MCE-BFE-NativeE}-{SgE} BFE > HKE > MCE > SgE | {NativeE}-{HKE-BFE-SgE-MCE} SgE > MCE > BFE > HKE |

| Senses | {SgE-HKE}-{MCE-NativeE-BFE} BFE > HKE > MCE > SgE | {NativeE-BFE}-{SgE-HKE-MCE} MCE > SgE > BFE > HKE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, Y.; Gilquin, G. Reassessing the Learner Englishes–New Englishes Continuum: A Lexico-Grammatical Analysis of TAKE in Written and Spoken Englishes. Languages 2025, 10, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110285

Tao Y, Gilquin G. Reassessing the Learner Englishes–New Englishes Continuum: A Lexico-Grammatical Analysis of TAKE in Written and Spoken Englishes. Languages. 2025; 10(11):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110285

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Yating, and Gaëtanelle Gilquin. 2025. "Reassessing the Learner Englishes–New Englishes Continuum: A Lexico-Grammatical Analysis of TAKE in Written and Spoken Englishes" Languages 10, no. 11: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110285

APA StyleTao, Y., & Gilquin, G. (2025). Reassessing the Learner Englishes–New Englishes Continuum: A Lexico-Grammatical Analysis of TAKE in Written and Spoken Englishes. Languages, 10(11), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10110285