Abstract

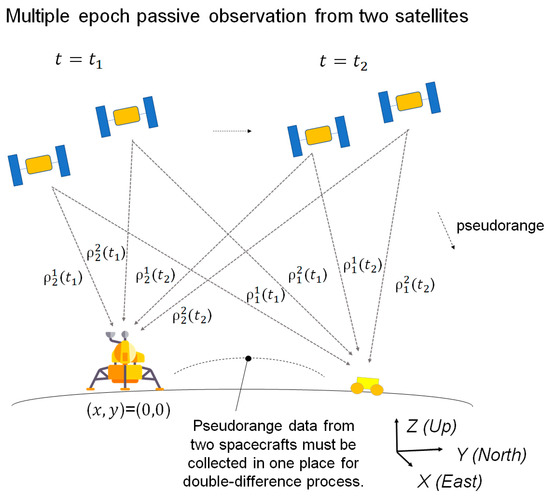

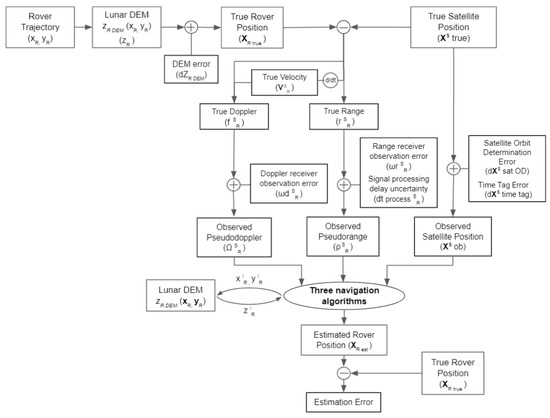

In this study, dual-satellite lunar global navigation systems that consist of a constellation of two navigation satellites providing geo-spatial positioning on the lunar surface were compared. In our previous work, we proposed a new dual-satellite relative-positioning navigation method called multi-epoch double-differenced pseudorange observation (MDPO). While the mathematical model of the MDPO and its behavior under specific conditions were studied, we did not compare its performance with other dual-satellite relative-positioning navigation systems. In this paper, we performed a comparative analysis between the MDPO and other two dual-satellite navigation methods. Based on the difference in their mathematical models, as well as numerical simulation results, we developed useful insights on the system design of dual-satellite lunar global navigation systems.

Keywords:

GNSS; lunar exploration; TOA; FOA; navigation; lunar rover; microsatellite; nanosatellite; interplanetary missions 1. Introduction

In recent years, communication and navigation architecture for lunar exploration programs has been of great interest [1]. In particular, the estimation of a rover vehicle’s position on the lunar surface is one of the key technologies for the successful operation of the rover, mapping resources, and making scientific observations on the lunar surface. It is well-known that cold-trapped volatiles, including water-ice, in lunar Permanently Shadowed Regions (PSRs) could be a high priority resource for future space exploration. As PSRs never receive direct sunlight, visual-odometry based navigation methods, such as simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), will be considerably constrained. Therefore, some alternative is needed to realize long and efficient exploration of the PSRs. Additionally, we aim to provide navigation information to multiple users on the lunar surface as the locations of various resources are not known precisely, and wide-range exploration by multiple small rovers is considered as promising approach [2]. With these two trends in mind, multiple-user navigation system that can be used in PSRs is of immediate demand.

As one feasible approach to establish the multiple-user navigation system for the lunar surface applications, several groups have studied the use of weak signals, i.e., the spill-over of the beams irradiated from global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) that serve Earth surface and proximity: the weak signals technology was investigated by [3] for the first time, and applications to the lunar navigation were extensively studied by a great deal of research [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. While they are capable of providing navigation signals at the middle latitude of the lunar surface, they are not available at the far side and polar regions of the Moon due to invisibility. As an alternative method, constellations of global navigation satellites around the Moon have been studied [11,12]. Additionally, a combination of the weak signals and a relatively small constellation of global navigation satellites around the Moon has been studied [13]. While they can provide geo-spatial positioning to the entire Moon and its proximity, the transportation cost to inject satellites into multiple lunar orbits, as well as the ground station cost to operate a large number of lunar satellites, is not affordable at the early stage of the lunar exploration programs.

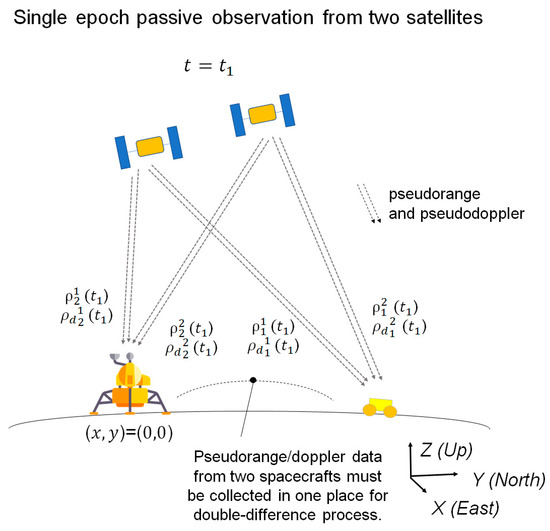

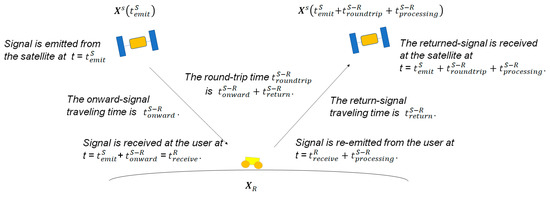

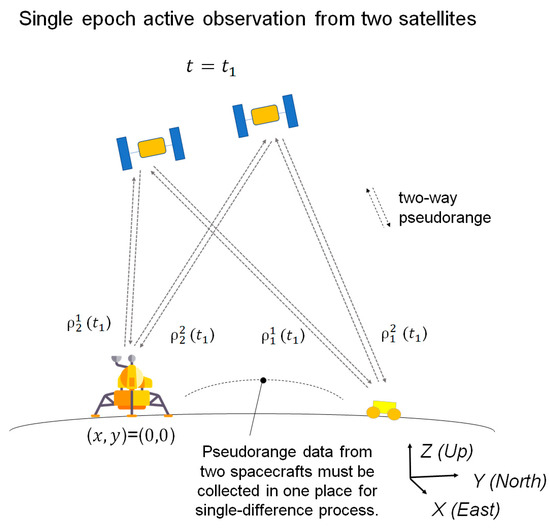

In an attempt to reduce the cost of global navigation satellite systems, dual-satellite lunar global navigation that consists of a constellation of two navigation satellites have been studied. Originally, dual-satellite global navigation methods have been studied for Earth GNSS in the literature [14,15] and applying them to lunar GNSS domain [16,17]. We also proposed a new dual-satellite relative-positioning navigation method called multi-epoch double-differenced pseudorange observation (MDPO) [18]. While the mathematical model of the MDPO and its behavior under specific conditions were studied, we did not sufficiently compare its performance with other dual-satellite global navigation systems. In this paper, we show a comparative analysis between the MDPO and other selected navigation methods. More specifically, we study and compare the following three navigation methods, (1) MDPO, (2) joint time difference of arrival and frequency difference of arrival (TDOA–FDOA) [15], and (3) two-way ranging [19], and discuss the pros and cons of each method.

These three dual-satellite navigation methods use different types of observations, namely passive ranging, passing ranging, and Doppler, or active ranging (two-way ranging), as shown in Table 1. As most dual-satellite navigation methods can be classified into one of these types of observations, a comparative analysis and evaluation of these methods will provide a benchmark of dual-satellite relative-positioning lunar GNSS. For instance, recent work in joint Doppler and ranging (JDR) [16], which converts a differenced Doppler shift into a pseudo-pseudorange using the Law of Cosines and integrates it with pseudorange observation, can be classified as evolved families of joint TDOA–FDOA: otherwise as evolved families of two-way ranging, if it employs two-way ranging observation instead of pseudorange observation.

Table 1.

Benchmark of dual-satellite lunar navigation systems.

Apart from these three types, dual-satellite navigation can be established only with Doppler observation. For example, in [17], it was successfully shown that Doppler Based Autonomous Navigation (DBAN) can operate with as few as one lunar orbiter and a reference station and enable autonomous positioning of crewed missions. However, we will rule out Doppler-only navigation from this comparative analysis, as it requires a long observation period and is not able to provide position estimates as quickly as the other methods do.

In this research, the target of our study comprises a micro-sized satellite and rover systems. In that case, power generation capability is limited by size and, consequently, not compatible with a high-standard clock source, such as the deep space atomic clock (DSAC) [20]. When the clock bias of space/user segment is not ignorable, or when satellite orbit determination error is not ignorable, the existing joint TDOA–FDOA method must be updated to a double-differenced form [21], the so-called double-differenced Time Of Arrival (TOA)–Frequency Of Arrival (FOA), to cope with the clock bias and orbit determination errors. Likewise, the two-way ranging method must be updated to a single-differenced form, the so-called single-differenced two-way ranging, to cope with the orbit determination errors. These updates have been taken into account to give a fair comparison.

The selected three navigation methods have different characteristics in terms of navigation accuracy and system complexity. The comparative study of these three navigation methods is shown in Table 1, which could assist designers to choose an appropriate method for their own purposes. For example, MDPO can provide navigation information to multiple users at a time through passive ranging but requires observations from multiple epochs. Double-differenced TOA–FOA can provide navigation information to multiple users at a time with observation from a single epoch but requires Doppler observation and pseudorange observation. Single-differenced two-way ranging can provide relatively high-accuracy navigation information with observation from a single epoch but only to a single user per one set of radio signals at a time, and also requires an active ranging, i.e., radio signal power emission at the user segment. We also compared the navigation accuracy of these three methods by numerical simulations under the selected conditions.

This paper consists of the following sections. In Section 2, we discuss the assumptions for our study. In Section 3, the mathematical models of the three navigation methods are presented. In Section 4, the achievable user position accuracies of three navigation methods are analyzed by numerical simulation and comparative studies are discussed. In Section 5, we summarize the key insights by analyzing the simulation results, and provide suggestions from a system design point of view.

2. Assumptions

In recent years, NASA and private sectors have extensively studied and developed unmanned micro mobile robots for lunar surface exploration [22,23]. The target of our study comprises a micro-sized satellite and rover system whose power generation capability is limited by size and, consequently, not compatible with the deep space atomic clock (DSAC). In this case, the best current clock technology that is compatible with the micro-sized satellite is the Chip Scale Atomic Clock (CSAC).

As reported in [24], while CSAC can suppress the frequency instability of the clock down to about 1 part per billion (ppb) for 24 h, CSAC incurs several tens to hundreds of meters of error in pseudorange observations after 24 h, which further increases over time. As a result, using CSAC inevitably requires pseudorange-based navigation systems to conduct frequent estimations of the satellite and/or user clock bias using Earth ground stations, which is very challenging in lunar GNSS due to the limitation of the availability and number of earth ground stations that are capable of Earth–Moon distance communication. In summary, the following assumptions were used:

- ●

- The bias of the satellite clock is not ignorable due to the limited capacity of micro-satellites;

- ●

- The bias of the rover clock is not ignorable due to the limited capacity of micro-rovers;

- ●

- The satellite orbit determination error is not ignorable due to the limitation of the availability and number of Earth ground stations.

5. Discussion

In general, the three navigation methods have different characteristics in terms of navigation accuracy and system complexity. Therefore, the system designer must understand the difference and representative performance of these three navigation methods to choose an appropriate method based on the desired specifications.

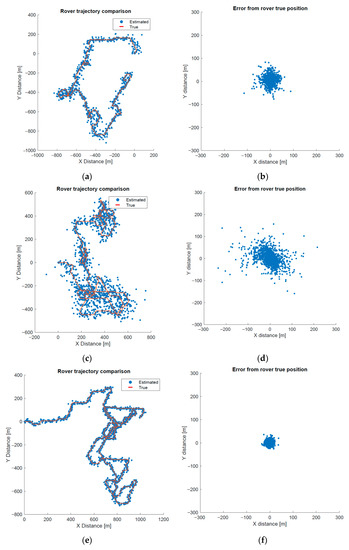

Through the numerical simulation, we quantitatively confirmed an achievable position accuracy for the three navigation methods under the selected orbital condition. From a user position accuracy point of view, single-differenced two-way ranging outperformed the other two navigation methods. The drawback of the single-differenced two-way ranging is power efficiency, which requires transmitting power at the rover side to reply each receiving radio signal from two satellites. Additionally, the method requires transmitting power at the satellite side to send radio signals to multiple users respectively, i.e., radio signals to multiple rovers and at least one lander.

Based on the simulation results in Section 4.3, if the mission requires a navigation accuracy as high as 30 m, but only for a single rover, and allows a radio signal emission at a rover, then single-differenced two-way ranging is the best choice. On the other hand, if the mission requires the provision of navigation information to multiple users, the MDPO or double-differenced TOA–FOA could be a more efficient option depending on the required accuracy, total traveling distance, and the desired system complexity, i.e., either requiring range sensors or range and Doppler sensors. For instance, the MDPO is the best choice from power efficiency point of view when the mission requires a multi-user navigation system, and the required user position accuracy is about 50 m.

A combination of two navigation methods could be considered to compensate their weaknesses. For example, having the MDPO and single-difference two-way ranging on the same satellite can change the configuration between providing several tens of meters of navigation accuracy to multiple users, or providing higher than thirty meters of navigation accuracy to a single user, depending on the mission needs, without launching another set of satellites.

Single-differenced two-way ranging can also be achieved with a single satellite using multi-epoch observation at the expense of availability. We will study that in our future work.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we studied and compared three dual-satellite lunar navigation systems that consist of a constellation of two navigation satellites. Dual-satellite navigation systems play key roles in establishing a low-cost navigation platform around the Moon. While several dual-satellite navigation methods have been studied, we focused on the comparison of three navigation methods, MDPO, double-differenced TOA–FOA, and single-differenced two-way ranging, as these three methods represent three different types in terms of observation data, i.e., passive ranging, passive ranging and doppler, and active ranging, into which most dual-satellite navigation methods can be classified.

First, we derived the mathematical models of these three methods step by step, to clarify the differences among the three navigation methods. Next, we confirmed the achievable user position accuracy of the three navigation methods by numerical simulation under the selected orbital conditions. Based on the numerical simulation results, we discussed the advantages and disadvantages of the three navigation methods and provided a guideline to select one or a combination of these three navigation methods depending on the mission requirements: From a user position accuracy point of view, single-differenced two-way ranging outperformed the other two navigation methods, while single-differenced two-way ranging requires larger power consumption at the rover side as well as at the satellite side. If the mission requires the provision of navigation information to multiple users, the MDPO or double-differenced TOA–FOA could be a more efficient option, depending on the desired specifications such as required accuracy, total traveling distance, and the desired system complexity, i.e., either requiring range sensors or range and Doppler sensors.

Furthermore, a combination of two navigation methods could be considered to compensate their weaknesses. For instance, having the MDPO and single-difference two-way ranging on the same satellite enables the users to choose between two configurations, providing several tens of meters of navigation accuracy to multiple users, or providing higher than thirty meters of navigation accuracy to a single user, without launching another set of satellites.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T., T.E. and S.N.; methodology, T.T.; software, T.T.; validation, T.T., T.E. and S.N.; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, T.T., T.E. and S.N.; resources, T.T.; data curation, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, T.T., T.E., S.N. and H.M.; visualization, T.T.; supervision, T.T., T.E., S.N. and H.M.; project administration, T.T., T.E., S.N. and H.M.; and funding acquisition, N/A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Yosuke Kawabata (Intelligent Space Systems Laboratory, The University of Tokyo) and Keidai Iiyama (same) are kindly acknowledged for their technical supports and advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Flanegan, M.; Gal-Edd, J.; Anderson, L.; Warner, J.; Ely, T.A.; Lee, C.; Shah, B.; Vaisnys, A.; Schier, J. NASA’s Lunar Communication and Navigation Architecture. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps 2008 Conference, Heidelberg, Germany, 12–16 May 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laîné, M.; Yoshida, K. Multi-Rover Exploration Strategies: Coverage Path Planning with Myopic Sensing. Ph.D. Thesis, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.C.; Davis, E.P.; Carpenter, J.R.; Kelbel, D.; Davis, G.W.; Axelrad, P. Results from the GPS Flight Experiment on the High Earth Orbit AMSAT OSCAR-40 Spacecraft. In Proceedings of the 15th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GPS 2002), Portland, OR, USA, 24–27 September 2002; pp. 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Palmerini, G.B.; Sabatini, M.; Perrotta, G. En route to the Moon using GNSS signals. Acta Astronaut. 2009, 64, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witternigg, N.; Obertaxer, G.; Schönhuber, M.; Palmerini, G.B.; Rodriguez, F.; Capponi, L.; Soualle, F.; Floch, J. Weak GNSS Signal Navigation for Lunar Exploration Missions. In Proceedings of the 28th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS + 2015), Tampa, FL, USA, 14–18 September 2015; pp. 3928–3944. [Google Scholar]

- Ashman, B.W.; Parker, J.K.; Bauer, F.H.; Esswein, M. Exploring the Limits of High Altitude GPS for Future Lunar Missions. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual AAS Guidance Control Conference (AAS/GNC), Breckenridge, CO, USA, 1–7 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Delépaut, A.; Giordano, P.; Ventura-Traveset, J.; Blonski, D.; Schönfeldt, M.; Schoonejans, P.; Aziz, S.; Walker, R. Use of GNSS for Lunar Missions and Plans for Lunar In-Orbit Development. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 2739–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, V.; Botteron, C.; Leclère, J.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Farine, P. Feasibility study of GNSS as navigation system to reach the Moon. Acta Astronaut. 2015, 116, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, V.; Blunt, P.; Botteron, C.; Tian, J.; Leclère, J.; Wang, Y.; Basile, F.; Farine, P.-A. Standalone GPS L1 C/A Receiver for Lunar Missions. Sensors 2016, 16, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manzano-Jurado, M.; Alegre-Rubio, J.; Pellacani, A.; Seco-Granados, G.; López-Salcedo, J.A.; Guerrero, E.; García-Rodríguez, A. Use of weak GNSS signals in a mission to the moon. In Proceedings of the 2014 7th ESA Workshop on Satellite Navigation Technologies and European Workshop on GNSS Signals and Signal Processing (NAVITEC), Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 3–5 December 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Long, L.; Xu, Z.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, H. Lunar far side positioning enabled by a CubeSat system deployed in an Earth-Moon halo orbit. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 64, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iiyama, K. Optimization of Navigation Satellite Constellation and Lunar Monitoring Station Arrangement for Lunar Global Navigation Satellite System (LGNSS). In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on Space Technology and Science (ISTS), Fukui, Japan, 15–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schonfeldt, M.; Grenier, A.; Delépaut, A.; Giordano, P.; Swinden, R.; Ventura-Traveset, J.; Blonski, D.; Hahn, J. A System Study about a Lunar Navigation Satellite Transmitter System. In Proceedings of the 2020 European Navigation Conference (ENC), Dresden, Germany, 23–24 November 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xhou, C.; Li, Q. Space Electronic Reconnaissance: Localization Theories and Methods; WILEY: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shilong, W.; Jingqing, L.; Liangliang, G. Joint FDOA and TDOA location algorithm and performance analysis of dual-satellite formations. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing Systems (ICSPS), Dalian, China, 5–7 July 2010; pp. V2-339–V2-342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.W.; Cheung, K.; Lightsey, E.G.; Lee, C. Localizing in Urban Canyons using Joint Doppler and Ranging and the Law of Cosines Method. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of the Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2019), Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019; pp. 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Cheung, K.-M.; Milton, J.; Lee, C.; Lightsey, G. Autonomous Navigation for Crewed Lunar Missions with DBAN. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Ebinuma, T.; Nakasuka, S. Dual-Satellite Lunar Global Navigation System Using Multi-Epoch Double-Differenced Pseudorange Observations. Aerospace 2020, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Music, M.; Newberry, L.; Peters, D.; Quetin, G.; Stickle, A.; Trescott, R.; Ackerman, K.; Bruun, E.; Cleveland, T.; Culver, T. Luna POLARIS A Lunar Positioning and Communications System. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268005025_Luna_POLARIS_A_Lunar_Positioning_and_Communications_System (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Ely, T.A.; Burt, E.A.; Prestage, J.D.; Seubert, J.M.; Tjoelker, R.L. Using the Deep Space Atomic Clock for Navigation and Science. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2018, 65, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, K.; Lee, C. Differencing Methods for 3D Positioning of Spacecraft. In Proceedings of the 2019 Integrated Communications, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Herndon, VA, USA, 9–11 April 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Article: Commercial CubeRover Test Shows How NASA Investments Mature Space Tech. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/commercial-cuberover-test-shows-how-nasa-investments-mature-space-tech (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Walker, J. Flight System Architecture of the Sorato Lunar Rover. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and Automation in Space (i-SAIRAS 2018), Madrid, Spain, 4–6 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rybak, M.M.; Axelrad, P.; Seubert, J.; Ely, T. Chip Scale Atomic Clock–Driven One-Way Radiometric Tracking for Low-Earth-Orbit CubeSat Navigation. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2021, 58, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The LROC Team Computed the Coordinates of China’s Chang’e 5 Lander. Available online: http://lroc.sese.asu.edu/posts/1172?fbclid=IwAR3fNoQuFQEmT6vSGh24yGPyRJAmpIfOln64IJCJg0bxC_A_dV6DNaCLJz0 (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Hennawy, J.; Adams, N.; Sanchez, E.; Srinivasan, D.; Hamkins, J.; Vilnrotter, V.; Xie, H.; Kinman, P. Telemetry ranging using software-defined radios. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.K.; Mazarico, E.; Neumann, G.A.; Zuber, M.T.; Haruyama, J.; Smith, D.E. A new lunar digital elevation model from the Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter and SELENE Terrain Camera. Icarus 2016, 273, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, D.E.; Zuber, M.T.; Neumann, G.A.; Mazarico, E.; Lemoine, F.G.; Head, J.W., III; Lucey, P.G.; Aharonson, O.; Robinson, M.S.; Sun, X.; et al. Summary of the results from the lunar orbiter laser altimeter after seven years in lunar orbit. Icarus 2017, 283, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/tskTNK/DualSatLunarNav (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- LRO Data Products. Available online: https://lunar.gsfc.nasa.gov/dataproducts.html (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Mazarico, E.; Neumann, G.A.; Barker, M.K.; Goossens, S.; Smith, D.E.; Zuber, M.T. Orbit determination of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. J. Geod. 2012, 86, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).