A Flexible Ultra-Thin Ultrasonic Transducer for Ice Detection on Curved Surfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

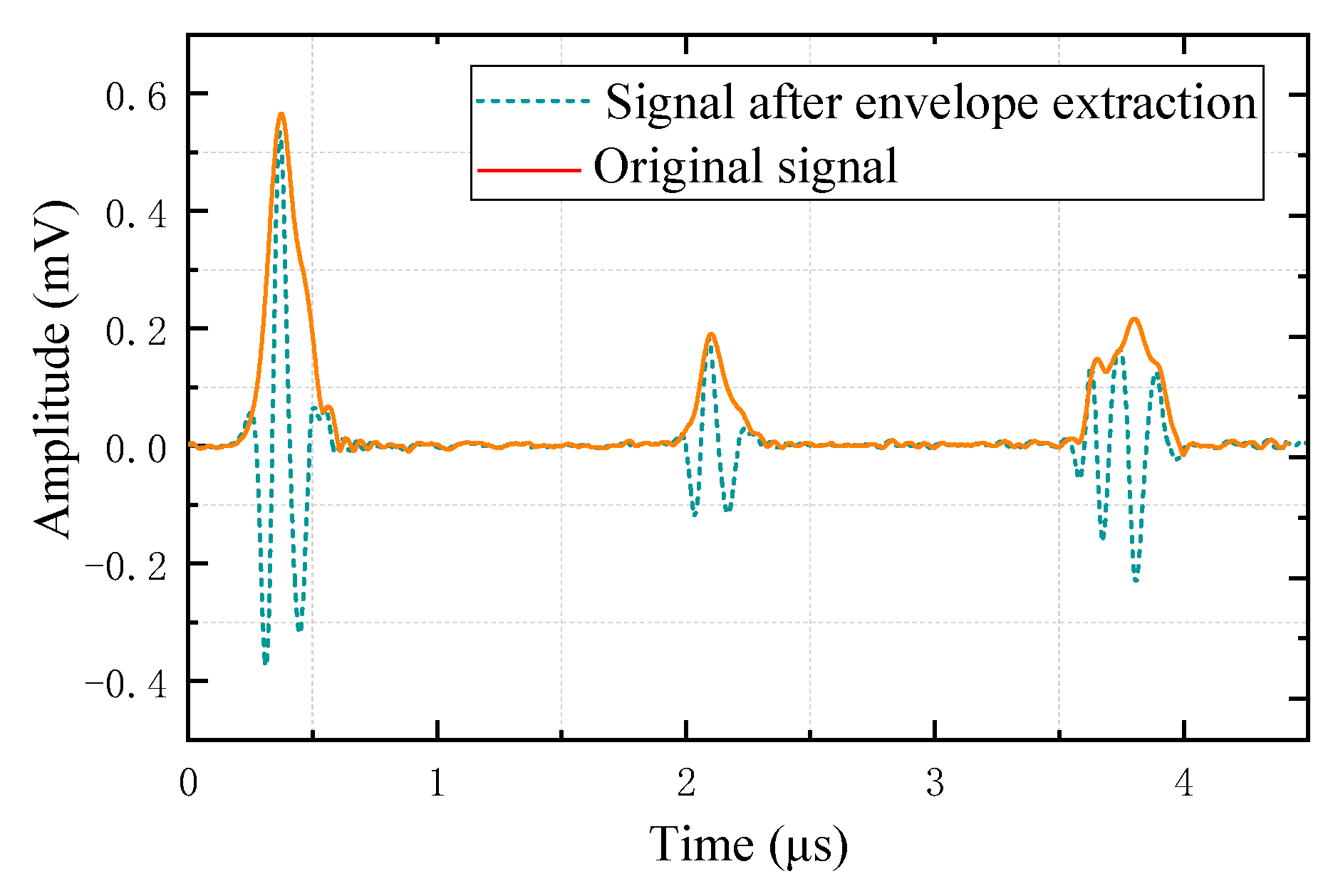

2.1. The Principle and Design of the FUTUT

2.2. Fabrication of the FUTUT

2.3. Performance Testing of the FUTUT

3. Ice Detection Experiments

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hutt, L. Aircraft Icing Handbook; Civil Aviation Authority: Wellington, New Zealand, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 1–4.

- Maio, L.; Memmolo, V.; Christophel, N.; Kohl, S.; Moll, J. Electromechanical admittance method to monitor ice accretion on a composite plate. Measurement 2023, 220, 113290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Soares, L.; Pei, J.Z.; Ge, J. Development and verification of integrated photoelectric system for noncontact detection of pavement ponding and freezing. Struct. Control. Health Monit. 2021, 28, e2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieman, L.; Guk, E.; Kim, T.; Son, C.; Kim, J.S. Development of a novel multi-channel thermocouple array sensor for in-situ monitoring of ice accretion. Sensors 2020, 20, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.C.; Wang, J.H.; Li, W.T.; Li, Z.H. The ice thickness system design based on PCap01 with high accuracy. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 602–605, 2482–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichman, L.; Fuleki, D.; Song, N.H.; Benmeddour, A.; Wolde, M.; Orchard, D. Airborne platform for ice-accretion and coatings tests with ultrasonic readings (PICTUR). SAE Tech. Pap. 2023, 1, 1431. [Google Scholar]

- Fuleki, D.; Sun, Z.; Wu, J.; Miller, G. Development of a non-intrusive ultrasound ice accretion sensor to detect and quantify ice accretion severity. In Proceedings of the 9th AIAA Atmospheric and Space Environments Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 5–9 June 2017; p. 4247. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, K.P.; Kuhn, D.C.; Bibeau, E.L. Capacitive probe for ice detection and accretion rate measurement: Proof of concept. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibilia, S.; Tari, L.; Bertocchi, F.; Chiodini, S.; Maffucci, A. A Capacitive ice-sensor based on graphene nano-platelets strips. Sensors 2023, 23, 9877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellekoop, N.J.; Jakoby, B.; Bastemeijer, J. A Love-wave ice detector. In 1999 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Proceedings of the International Symposium (Cat. No. 99CH37027), Tahoe, NV, USA, 17–20 October 1999; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 453–456. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C.; Ni, S.H.; Li, H.L.; He, S.T.; Zhang, Z.L. Study of love wave aircraft ice sensor. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2009, 30, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Cheng, L.; Liang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xiao, H. Development of love wave-based ice sensor incorporating a PDMS micro-tank. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 4740–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yin, Y.; Hu, A.; Wang, W.; Liang, Y. The U-net-based ice pore parameter extraction method for establishing the SAW icing sensing mechanism. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 373, 115394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ong, H.; Haworth, L.; Lu, Y.; Yang, D.; Rahmati, M.; Wu, Q.; Torun, H.; Martin, J.; Hou, X.; et al. Fundamentals of monitoring condensation and frost/ice formation in cold environments using thin-film surface-acoustic-wave technology. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 35648–35663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansman, J.R.; Kirby, M.S. Measurement of ice accretion using ultrasonic pulse-echo techniques. J. Aircr. 1985, 22, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansman, J.R.; Kirby, M.S.; Lichtenfelts, F. Ultrasonic techniques for aircraft ice accretion measurement. Sens. Meas. Tech. Aeronaut. Appl. 1988, 9, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.L.; Bond, L.J.; Hu, H. Development of an ultrasonic pulse-echo (UPE) technique for aircraft icing studies. AIP Conf. Proc. 2014, 1581, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Bond, L.J.; Hu, H. Ultrasonic-attenuation-based technique for ice characterization pertinent to aircraft icing phenomena. AIAA J. 2017, 55, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Bond, L.J.; Hu, H. A feasibility study to identify ice types by measuring attenuation of ultrasonic waves for aircraft icing detection. In Proceedings of the Asme Joint US-European Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–7 August 2014; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 46223, p. V01BT22A003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, D.Y.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, C.L. Quantitative measurement method for ice roughness on an aircraft surface. Aerospace 2022, 9, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, D.W.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, C.L. Study on freezing characteristics of the surface water film over glaze ice by using an ultrasonic pulse-echo technique. Ultrasonics 2022, 126, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, K.T.; Kobayashi, M.; Jen, C.K.; Mrad, N. In situ ice and structure thickness monitoring using integrated and flexible ultrasonic transducers. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17, 045023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løw-Hansen, B.; Hann, R.; Stovner, B.N.; Johansen, T.A. UAV icing: A survey of recent developments in ice detection methods. IFAC-Pap. 2023, 56, 10727–10739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, J.L.; Smith, E.; Rose, J. Investigation of an ultrasonic ice protection system for helicopter rotor blades. In Proceedings of the Annual Forum Proceedings-American Helicopter Society, Montreal, QC, Canada, 29 April–1 May 2008; American Helicopter Society, Inc.: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2008; Volume 64, p. 609. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, M.; Chatterton, S.; Toscani, N.; Mauri, M.; Carmeli, M.S.; Castelli-Dezza, F. Wireless power transfer with temperature monitoring interface for helicopter rotor blade ice protection. In Proceedings of the 2020 AIAA/IEEE Electric Aircraft Technologies Symposium (EATS), New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–28 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.; Yang, Y.; Zuo, H.; Zhong, D. A review on ice detection technology and ice elimination technology for wind turbine. Wind. Energy 2020, 23, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.Y.; Karlsson, T.; Virk, M.S. Wind turbine ice detection using AEP loss method: A case study. Wind. Eng. 2022, 46, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ED-103; Minimum Operational Performance Specification for in-Flight Icing Detection Systems. AC-9C Aircraft Icing Technology Committee: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022.

- Gururaja, T.R.; Schulze, W.A.; Cross, L.E.; Newnham, R.E.; Auld, B.A.; Wang, Y.J. Piezoelectric composite materials for ultrasonic transducer applications. part I: Resonant modes of vibration of PZT rod-polymer composites. IEEE Trans. Sonics Ultrason. 1985, 32, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.A.; Auld, B.A. Modeling 1–3 composite piezoelectrics: Thickness-mode oscillations. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1991, 38, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.A. Modeling 1–3 composite piezoelectrics: Hydrostatic response. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1993, 40, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Cui, Z.; Chang, W.Y.; Kim, H.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, X. Flexible 1–3 composite ultrasound transducers with silver-nanowire-based stretchable electrodes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 6955–6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Zhu, C.X.; Wu, D.W.; Zhu, C.L.; Lu, X.Y. Focused ultrasonic transducer for aircraft icing detection. Ultrasonics 2024, 147, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Swanevelder, J. Resolution in ultrasound imaging. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Crit. Care Pain 2011, 11, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, C.X.; Zhao, N.; Zhu, C.L. Early warning and thickness measurement of aircraft icing using ultrasonic pulse echoes. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2025, 239, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PZT 5H | Epoxy | Piezocomposite | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1010 N/m2) | 13.7 | 0.53 | - |

| (1010 N/m2) | 8.8 | 0.31 | - |

| (1010 N/m2) | 9.23 | - | - |

| (1010 N/m2) | 12.6 | - | 3.75 |

| (C/m2) | −9.4 | - | - |

| (C/m2) | 22.5 | - | 17.73 |

| / | 1200.2 | - | - |

| (103 kg/m3) | 7.84 | 1.1 | 5.14 |

| kt (%) | 55 | - | 62.4 |

| t (μm) | Ve (%) | fc (MHz) | Z (MRayl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory | 170 | 60 | 10.4 | 18 |

| Experiment | 171 | 64 | 9.82 | 20.72 |

| Temperature (°C) | FUTUT (mm) | Tracing (mm) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −6.7 | 2.23 | 2.1 | 6.19 |

| −10 | 3.71 | 3.65 | 1.64 |

| −11 | 2.71 | 2.62 | 3.44 |

| −12 | 3.09 | 3.01 | 2.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Zhu, C.; Wu, D.; Zhu, C.; Wu, Y. A Flexible Ultra-Thin Ultrasonic Transducer for Ice Detection on Curved Surfaces. Aerospace 2025, 12, 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110997

Wang Y, Wang Y, Lu Q, Zhu C, Wu D, Zhu C, Wu Y. A Flexible Ultra-Thin Ultrasonic Transducer for Ice Detection on Curved Surfaces. Aerospace. 2025; 12(11):997. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110997

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yan, Yuan Wang, Qingwen Lu, Chengxiang Zhu, Dawei Wu, Chunling Zhu, and Yuan Wu. 2025. "A Flexible Ultra-Thin Ultrasonic Transducer for Ice Detection on Curved Surfaces" Aerospace 12, no. 11: 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110997

APA StyleWang, Y., Wang, Y., Lu, Q., Zhu, C., Wu, D., Zhu, C., & Wu, Y. (2025). A Flexible Ultra-Thin Ultrasonic Transducer for Ice Detection on Curved Surfaces. Aerospace, 12(11), 997. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110997