Multi-Level Firing with Spiking Neural Network for Orbital Maneuver Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

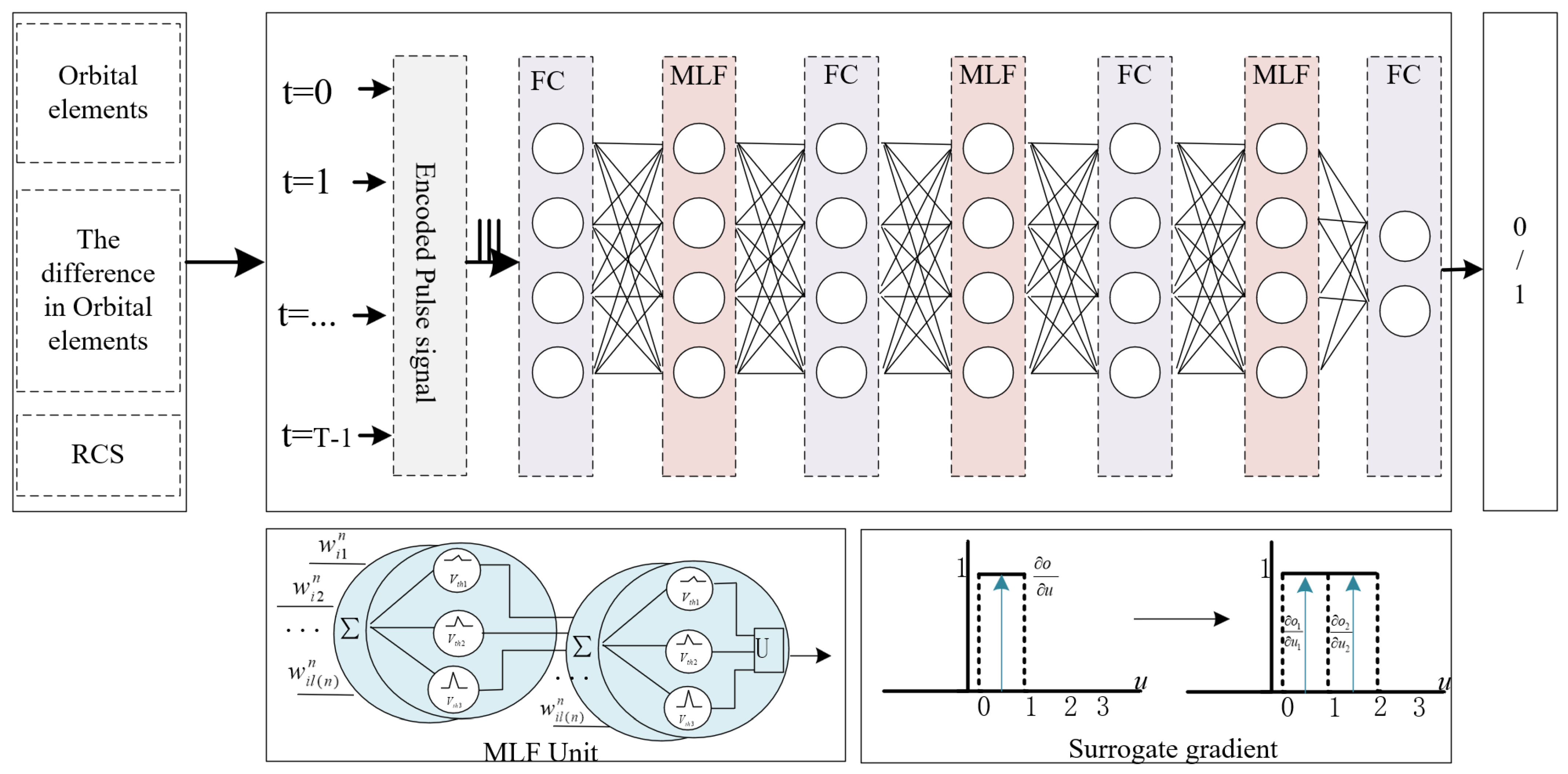

- We first proposed the first application of a SNN to the task of space object orbital maneuver detection, introducing an energy-efficient and temporally aware bio-inspired approach to a domain traditionally dominated by artificial neural networks.

- We propose a Multi-Level Firing MLF-SNN with LIF neurons at varying thresholds to mitigate gradient vanishing and improve feature expression in dynamic orbital modeling. Combined with surrogate gradients, this mechanism enables stable backpropagation and enhances capture of maneuver detection.

- The proposed method demonstrates superior performance in terms of detection recall, effectively identifying both impulsive and low-thrust maneuvers while maintaining robustness against noisy and sparse orbital data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Physical Model-Based Orbital Maneuver Detection

2.2. Deep Learning Based Orbital Maneuver Detection

2.3. Brain-Inspired Based Detection Methods

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Overview

3.2. MLF Unit

3.3. MLF-SNN for Orbit Maneuver Detection

3.4. The Surrogate Gradient

3.5. Loss Function

| Algorithm 1: MLF-SNN Satellite Maneuver Detection with Multi-Level Firing. |

| Input: Orbital elements dataset: , Maneuver labels: , Time steps: T Output: Trained model weights: , Prediction results: , Performance metrics:

|

4. Experiments

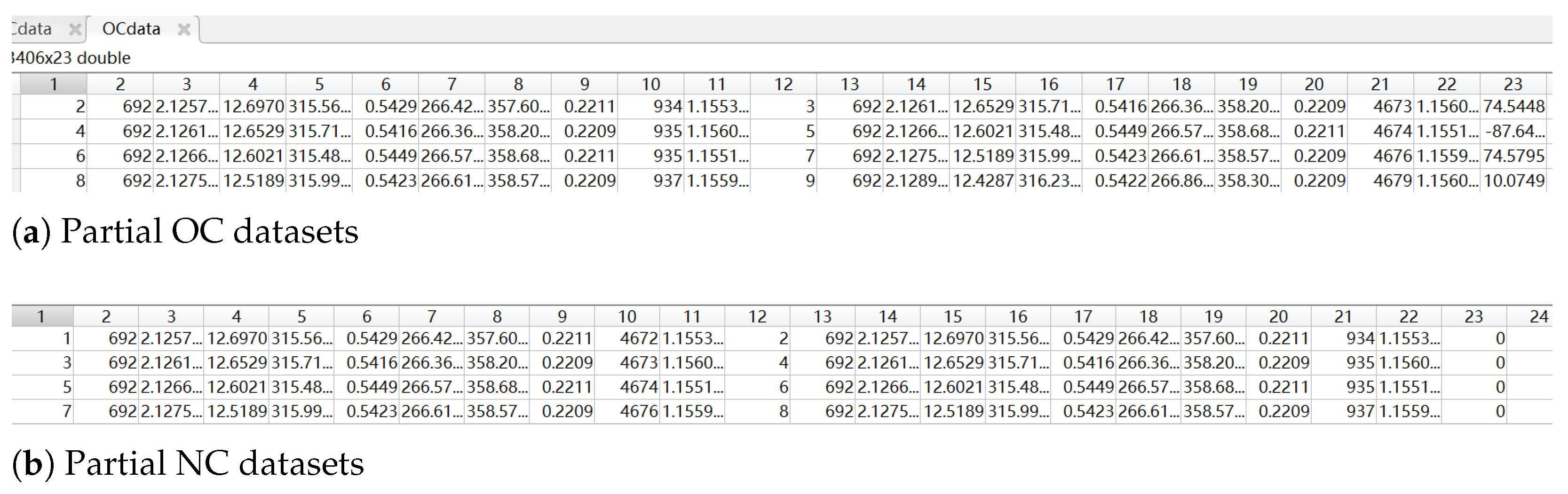

4.1. Dataset

- Pre-maneuver orbital elements:

- Target orbital elements number (pre-maneuver)

- Satellite ID (pre-maneuver)

- Epoch time (pre-maneuver)

- Orbital inclination (pre-maneuver)

- Right ascension of the ascending node - RAAN (pre-maneuver)

- Eccentricity (pre-maneuver)

- Argument of perigee (pre-maneuver)

- Mean anomaly (pre-maneuver)

- Mean motion (revolutions per day, pre-maneuver)

- Revolution number at epoch (pre-maneuver)

- Semi-major axis (pre-maneuver)

- Post-maneuver orbital elements:

- 12.

- Target orbital elements number (post-maneuver)

- 13.

- Satellite ID (post-maneuver)

- 14.

- Epoch time (post-maneuver)

- 15.

- Orbital inclination (post-maneuver)

- 16.

- RAAN (post-maneuver)

- 17.

- Eccentricity (post-maneuver)

- 18.

- Argument of perigee (post-maneuver)

- 19.

- Mean anomaly (post-maneuver)

- 20.

- Mean motion (revolutions per day, post-maneuver)

- 21.

- Revolution number at epoch (post-maneuver)

- 22.

- Semi-major axis (post-maneuver)

- Derived feature:

- 23.

- Change in semi-major axis (post-maneuver minus pre-maneuver)

4.2. Parameter Configuration

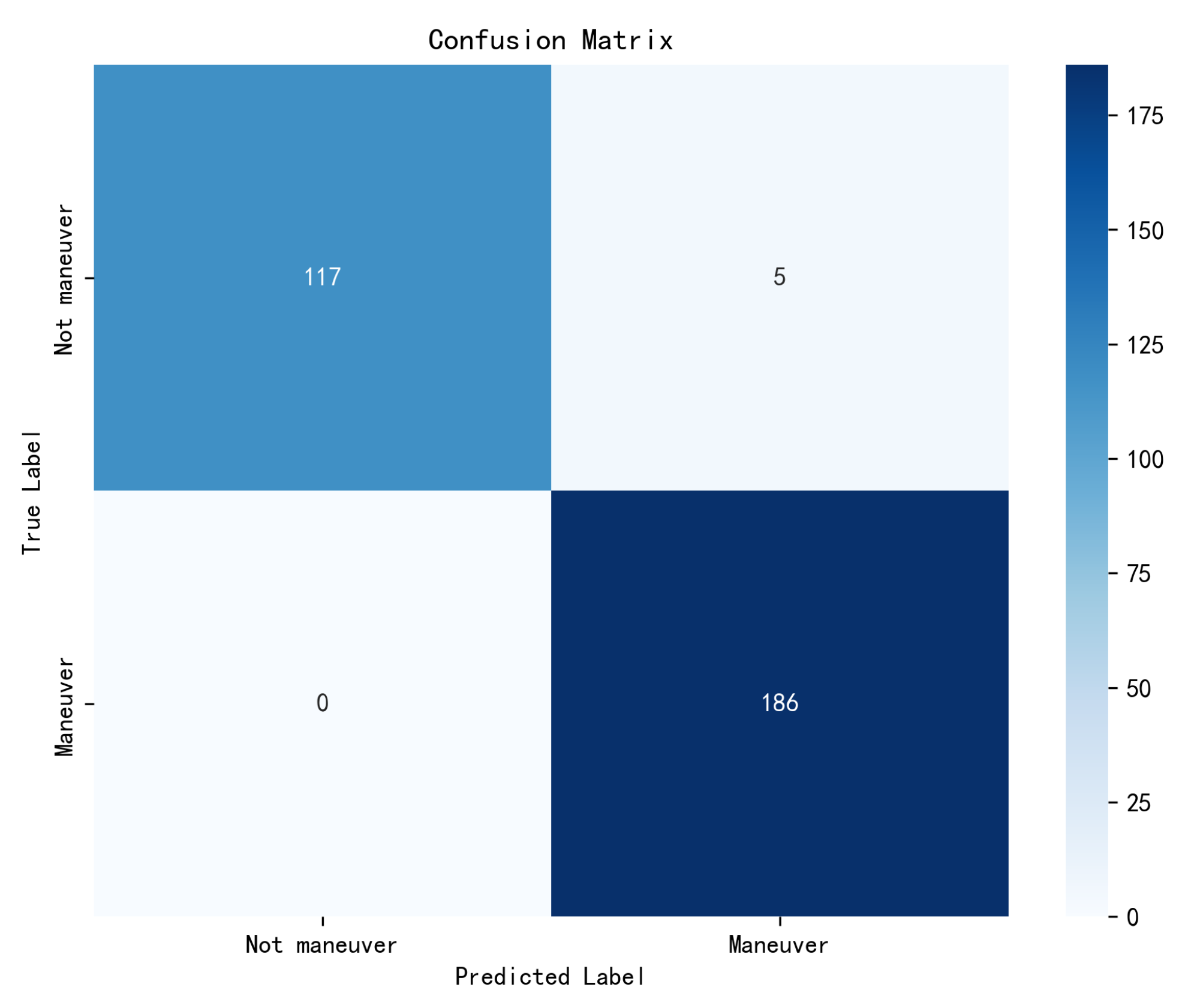

4.3. Quantitative Result

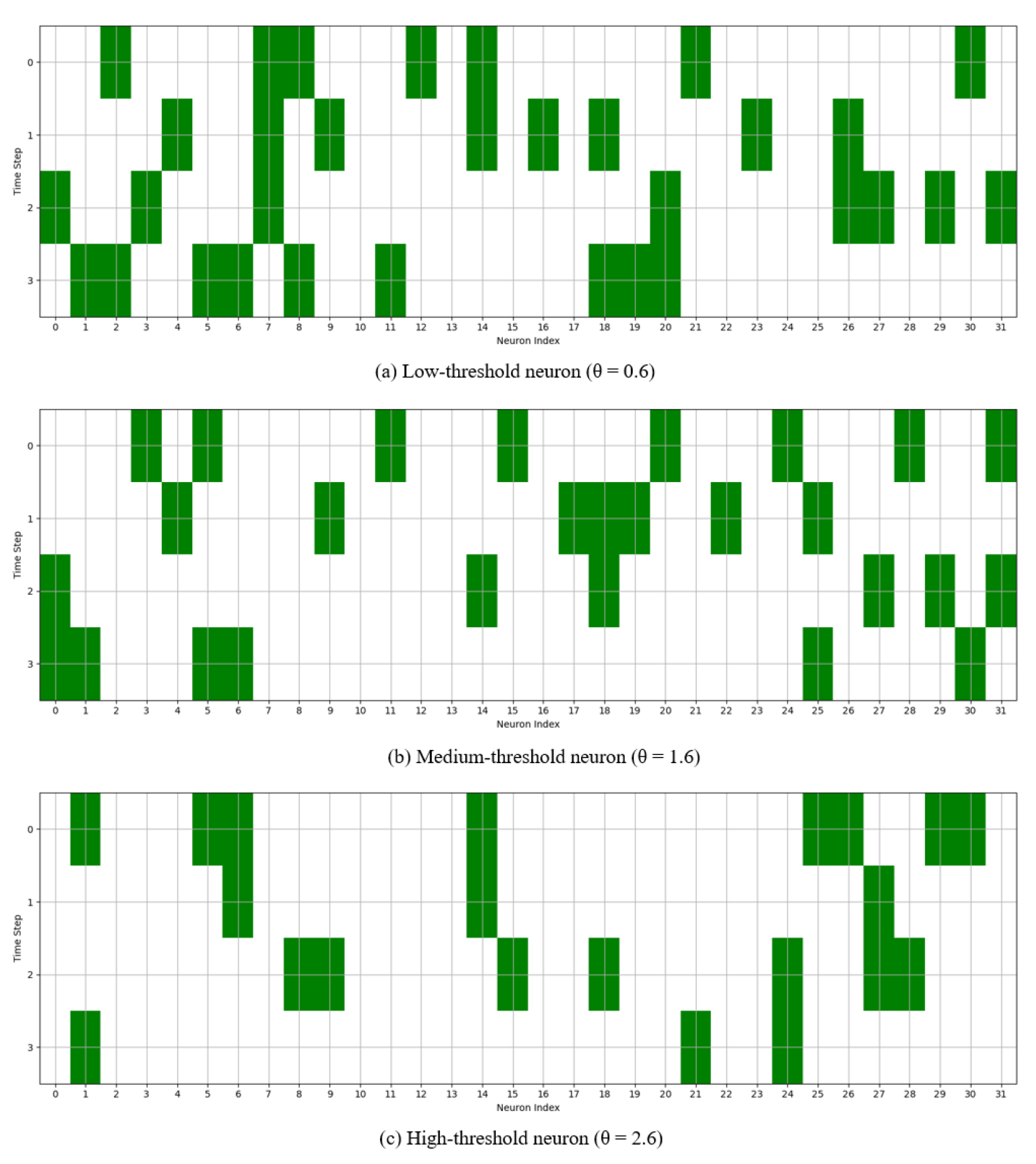

4.4. Multi-Level LIF Neuron Spiking Activity

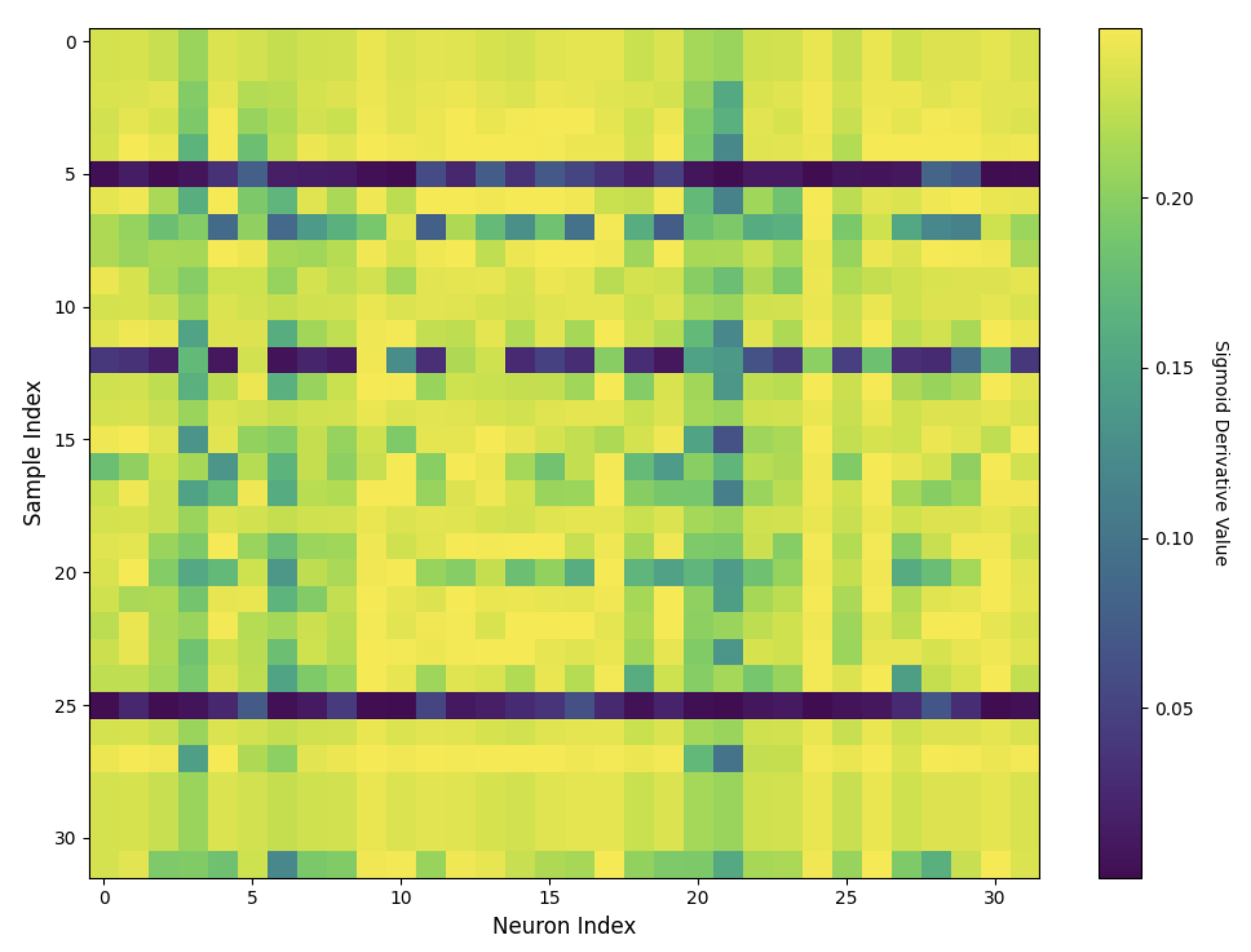

4.5. Analysis of Surrogate Gradient Dynamics

5. Ablation Experiment

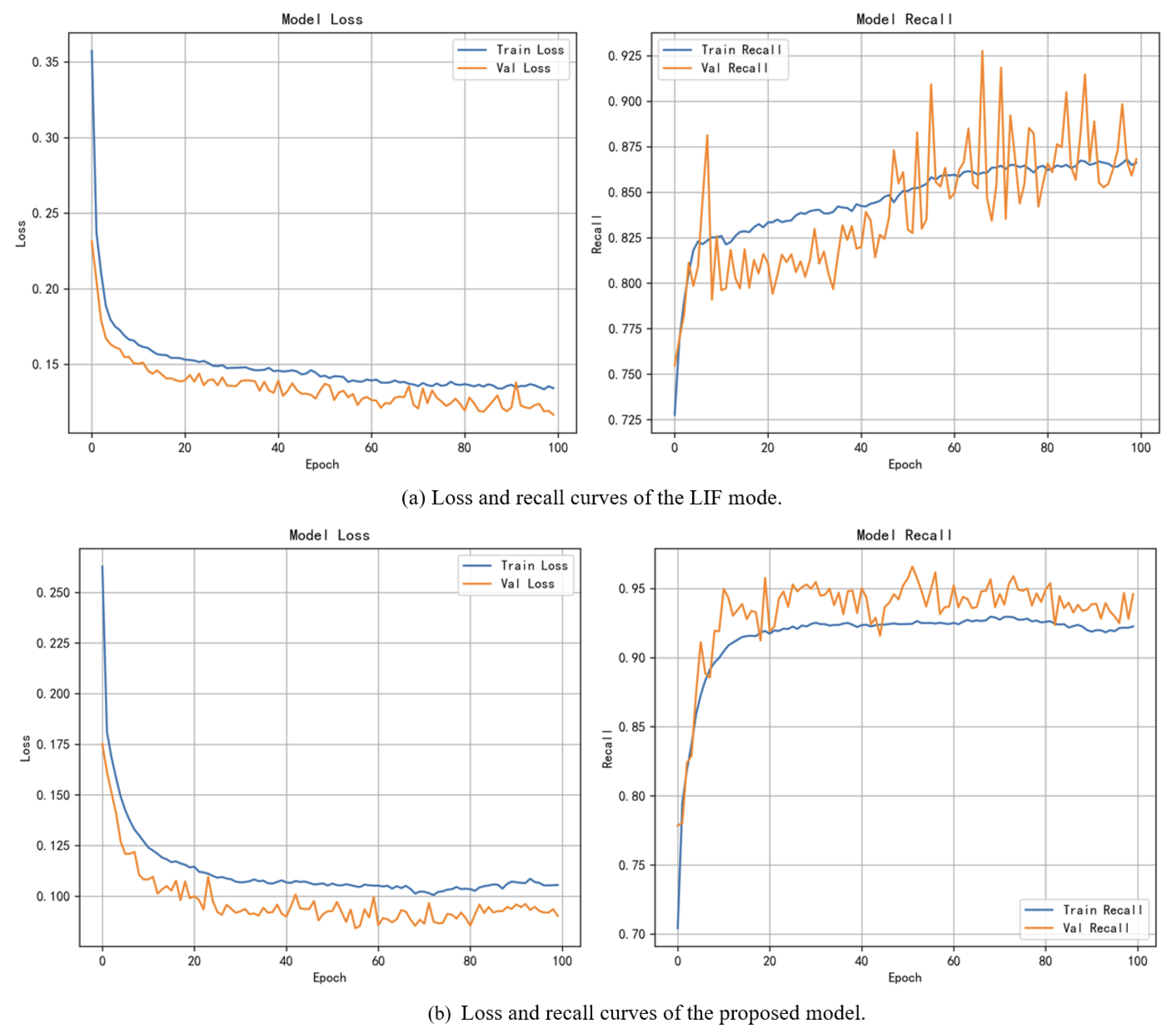

5.1. Analysis of Multi-Level Firing Spiking

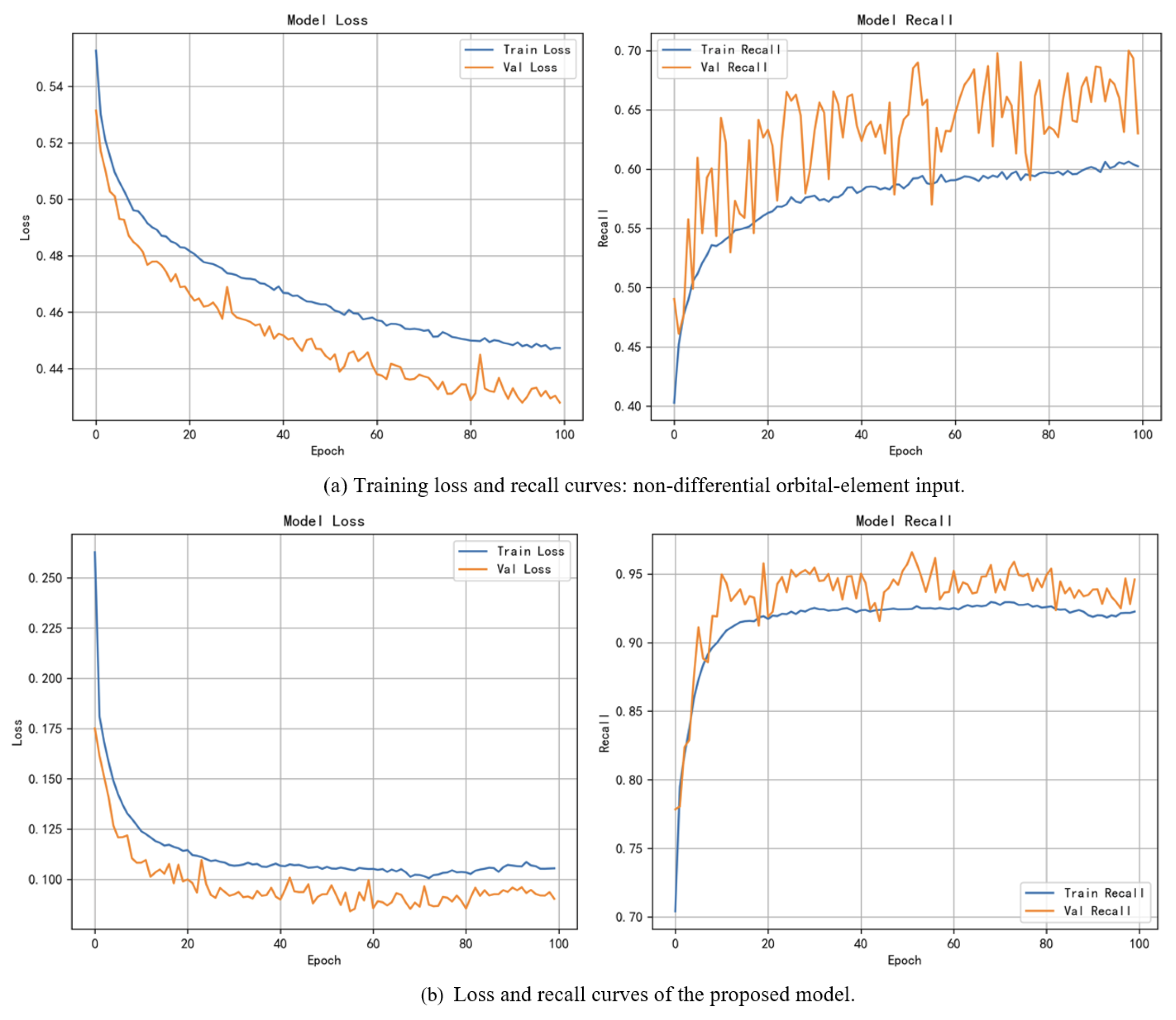

5.2. Effect Analysis of Taking the Differential Characteristics of Orbital Elements as Input

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Y.; Shao, Q.; Lv, L.; Fang, G.; Yue, H. Nonlinear dynamics of a space tensioned membrane antenna during orbital maneuvering. Aerospace 2022, 9, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jin, X.; Gong, B.; Han, F. Space-Based Passive Orbital Maneuver Detection Algorithm for High-Altitude Situational Awareness. Aerospace 2024, 11, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Yang, L.; Cai, W.; Liu, J. GEO spacecraft maneuver detection based on causal inference. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 72, 3756–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patera, R.P. Space event detection method. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2008, 45, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, L. Historical-orbital-data-based method for monitoring the operational status of satellites in low Earth orbit. Acta Astronaut. 2018, 151, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, K.; Chen, L. Maneuver detection method based on probability distribution fitting of the prediction error. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2019, 56, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Liao, C.; Pan, X.; Xu, M. Mining two-line element data to detect orbital maneuver for satellite. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 129537–129550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, A.; Escribano, G.; Escobar, D. Satellite maneuver detection with optical survey observations. In Proceedings of the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference (AMOS), Maui, HI, USA, 15–18 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.; Xiong, W.; Han, J. Research on the Method of GEO Satellite Maneuver Detection Based on TLE Data. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Aviation Safety and Information Technology, Weihai, China, 14–16 October 2020; pp. 705–709. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Du, J.; Sang, J. TLE outlier detection based on expectation maximization algorithm. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 2695–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, G.M.; Black, J.T.; Beck, J.A. Tracking maneuvering spacecraft with filter-through approaches using interacting multiple models. Acta Astronaut. 2015, 114, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zou, J.; Wu, W.; Chen, J. Orbital maneuver detection method of space target based on Neyman-Pearson criterion. Chin. Space Sci. Technol. 2021, 41, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Huang, H.X.; Li, J.S.; Luo, Y.Z. Spacecraft Maneuver Detection Based on Nonlinear Uncertainty Propagation Along Decussated Orbital Arc. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 76, 2472–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovich, N.; Folcik, Z.; Jaimes, R. Applications of artificial intelligence methods for satellite maneuver detection and maneuver time estimation. In Proceedings of the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference (AMOS), Maui, HI, USA, 27–30 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cipollone, R.; Leonzio, I.; Calabrò, G.; Di Lizia, P. An LSTM-based Maneuver Detection Algorithm from Satellites Pattern of Life. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 10th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace (MetroAeroSpace), Milan, Italy, 19–22 June 2023; pp. 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cipollone, R.; Frueh, C.; Di Lizia, P. LSTM-based maneuver detection for resident space object catalog maintenance. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 17341–17362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, R.; Gehly, S.; Balage, S.; Brown, M.; Boyce, R. Maneuver detection of space objects using generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference, Maui, HI, USA, 11–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Y.; Ziyu, Z.; Qingrui, Z.; Rong, M.; Pei, C. Maneuver Detection of Cataloged Space Object Based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 43rd Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Kunming, China, 28–31 July 2024; pp. 6038–6043. [Google Scholar]

- Perovich, N.; Folcik, Z.; Jaimes, R. Satellite maneuver detection using machine learning and neural network methodsbehaviors. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Aerospace Conference (AERO), Big Sky, MT, USA, 5–12 March 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, R.; Sakaue, T.; Mori, D.; Tanaka, M.; Sano, T.; Taya, K.; Ebara, M.; Nakazawa, R.; Yoshida, J.; Togawa, R. Validity evaluation of anomaly detection using lstm autoencoder for maneuver detection. In Proceedings of the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance (AMOS) Technologies Conference, Maui, HI, USA, 19–22 September 2023; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhu, T. Maneuver detection methods for space objects based on dynamical model. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D. A station-keeping maneuver detection method of non-cooperative geosynchronous satellites. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Xia, Q.; Qian, H.; Qiao, B.; Xu, J.; Xiao, B. An intelligent hierarchical recognition method for long-term orbital maneuvering intention of non-cooperative satellites. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 75, 5037–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bu, T.; Hu, L. A Dynamic Dual-Processing Object Detection Framework Inspired by the Brain’s Recognition Mechanism. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 6264–6274. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Shi, J.; Liu, M.; Han, W.; Bi, L.; Fei, W. Brain-inspired deep learning model for EEG-based low-quality video target detection with phased encoding and aligned fusion. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 288, 128189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wu, L.; Rong, J.; Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Luo, M. Synergistic Optimization Mechanism of Brain-Inspired Intelligence and Generative Models in Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Conference on Generative Artificial Intelligence and Information Security, Hangzhou, China, 21–23 February 2025; pp. 242–246. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, S.; Shen, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yan, R.; Tang, H. Learnable Surrogate Gradient for Direct Training Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Macao, China, 19–25 August 2023; pp. 3002–3010. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.M.; Shekhawat, H.S.; Pidanic, J.; Trivedi, G. FPGA-Based Adaptive LIF Neuron for High-Speed, Energy-Efficient Spiking Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Artif. Intell. 2025, 2, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yao, F.; Kang, Y. Design and Application of Spiking Neural Networks Based on LIF Neurons. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Data Analytics, Computing and Artificial Intelligence (ICDACAI), Zakopane, Poland, 18–20 October 2024; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

| Comparison | Deep Learning (DL) | LIF Neuron | Multi-Level Firing Neurons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computing Unit | Artificial neurons (ReLU/Sigmoid) | Spiking neurons (Leaky Integrate-and-Fire) | Multi-threshold LIF neurons |

| Connection Structure | Fully connected/convolutional/recurrent | Fixed or trainable synaptic connections | Shared weights across multi-level neurons |

| Dynamic Characteristics | Static or recurrent activations | Temporal dynamics with spike reset mechanism | Multi-level firing with expanded gradient region |

| Training Mechanism | Backpropagation (BP) | Spatio-Temporal Backpropagation (STBP) | STBP with multi-level gradient propagation |

| Temporal Processing | Requires RNN/LSTM modules | Inherent temporal coding capability | Enhanced temporal representation with multiple thresholds |

| Biological Plausibility | Low | High | Medium (multi-threshold approximation) |

| Key Implementation | Standard PyTorch1.7 modules | STBP with surrogate gradients | Multi-level LIF units with weight sharing |

| Parameter Category | Parameter Name | Value | Functional Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| TimeStep | 4 | Number of time steps, controlling the temporal dimension | |

| Network Architecture | hidden_sizes | [128, 64, 32] | Configuration of neuron counts in SNN hidden layers |

| dropout_rate | 0.3 | Dropout rate for regularization to prevent overfitting | |

| Vth | 0.6 | Threshold voltage for the first LIF neuron layer | |

| Vth2 | 1.6 | Threshold voltage for the second LIF neuron layer | |

| Neuron Parameters | Vth3 | 2.6 | Threshold voltage for the third LIF neuron layer |

| a | 1.0 | Width parameter for the trapezoidal surrogate gradient function | |

| tau | 0.75 | Membrane potential leakage decay factor | |

| batch_size | 256 | Batch size for training | |

| Training Parameters | epochs | 100 | Total number of training epochs |

| class_weights | [1.0, 3.0] | Class weights for cross-entropy loss, with higher weight for positive class | |

| learning_rate | 0.001 | Initial learning rate for Adam optimizer | |

| Optimizer Parameters | weight_decay | Weight decay coefficient for Adam optimizer | |

| reduce_lr_patience | 10 | Patience value for ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler | |

| Scheduler Parameters | reduce_lr_factor | 0.5 | Learning rate reduction factor for ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler |

| Satellite ID | CNN | The Proposed Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM | MD | FD | PM | RM | MD | FD | PM | |

| 50414 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 50423 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 50424 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 50425 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 50429 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| 50432 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 50433 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 50434 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 50435 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 50436 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 50437 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 50438 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 50439 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 50440 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 50441 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| 50442 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 50445 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| 50446 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 50447 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| 50448 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 50449 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 50450 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| EN | EN | Pred. Label | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6843.8369 | 2 | 6842.6169 | −1.2200 | 1 |

| 2 | 6842.6169 | 3 | 6842.4245 | −0.1924 | 1 |

| 3 | 6842.4245 | 4 | 6841.6918 | −0.7327 | 1 |

| 4 | 6841.6918 | 5 | 6841.6918 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 5 | 6841.6918 | 6 | 6840.4492 | −1.2426 | 1 |

| 6 | 6840.4492 | 7 | 6840.4492 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 7 | 6840.4492 | 8 | 6839.2828 | −1.1664 | 1 |

| 8 | 6839.2828 | 9 | 6838.6289 | −0.6539 | 1 |

| 9 | 6838.6289 | 10 | 6838.6289 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 10 | 6838.6289 | 11 | 6838.0199 | −0.6091 | 1 |

| 11 | 6838.0199 | 12 | 6837.3109 | −0.7089 | 1 |

| 12 | 6837.3109 | 13 | 6837.3109 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| 13 | 6837.3109 | 14 | 6836.5326 | −0.7783 | 1 |

| 14 | 6836.5326 | 15 | 6836.0669 | −0.4657 | 1 |

| 15 | 6836.0669 | 16 | 6835.3282 | −0.7387 | 1 |

| LIF | The Proposed Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Average Recall | 0.841 | 0.940 |

| Non-Differential Input | The Proposed Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Average Recall | 0.624 | 0.940 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Pei, Z.; Wen, X.; Zhang, L.; Qiao, K.; Zhu, Z. Multi-Level Firing with Spiking Neural Network for Orbital Maneuver Detection. Aerospace 2025, 12, 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110991

Chen H, Pei Z, Wen X, Zhang L, Qiao K, Zhu Z. Multi-Level Firing with Spiking Neural Network for Orbital Maneuver Detection. Aerospace. 2025; 12(11):991. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110991

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hui, Zhongmin Pei, Xiang Wen, Lei Zhang, Kai Qiao, and Ziwen Zhu. 2025. "Multi-Level Firing with Spiking Neural Network for Orbital Maneuver Detection" Aerospace 12, no. 11: 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110991

APA StyleChen, H., Pei, Z., Wen, X., Zhang, L., Qiao, K., & Zhu, Z. (2025). Multi-Level Firing with Spiking Neural Network for Orbital Maneuver Detection. Aerospace, 12(11), 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12110991