1. Introduction

Aerodynamic and stealth performance are critical metrics for evaluating the overall capabilities of cooperative UAVs [

1]. Consequently, they typically employ low-observable designs characterized by smooth, flat, and compact configurations. As an important part of the power system, the inlet not only needs to ensure the recovery of total pressure and flow uniformity at the engine face to provide stable and high-quality air flow for the engine, but also needs to have better stealth performance [

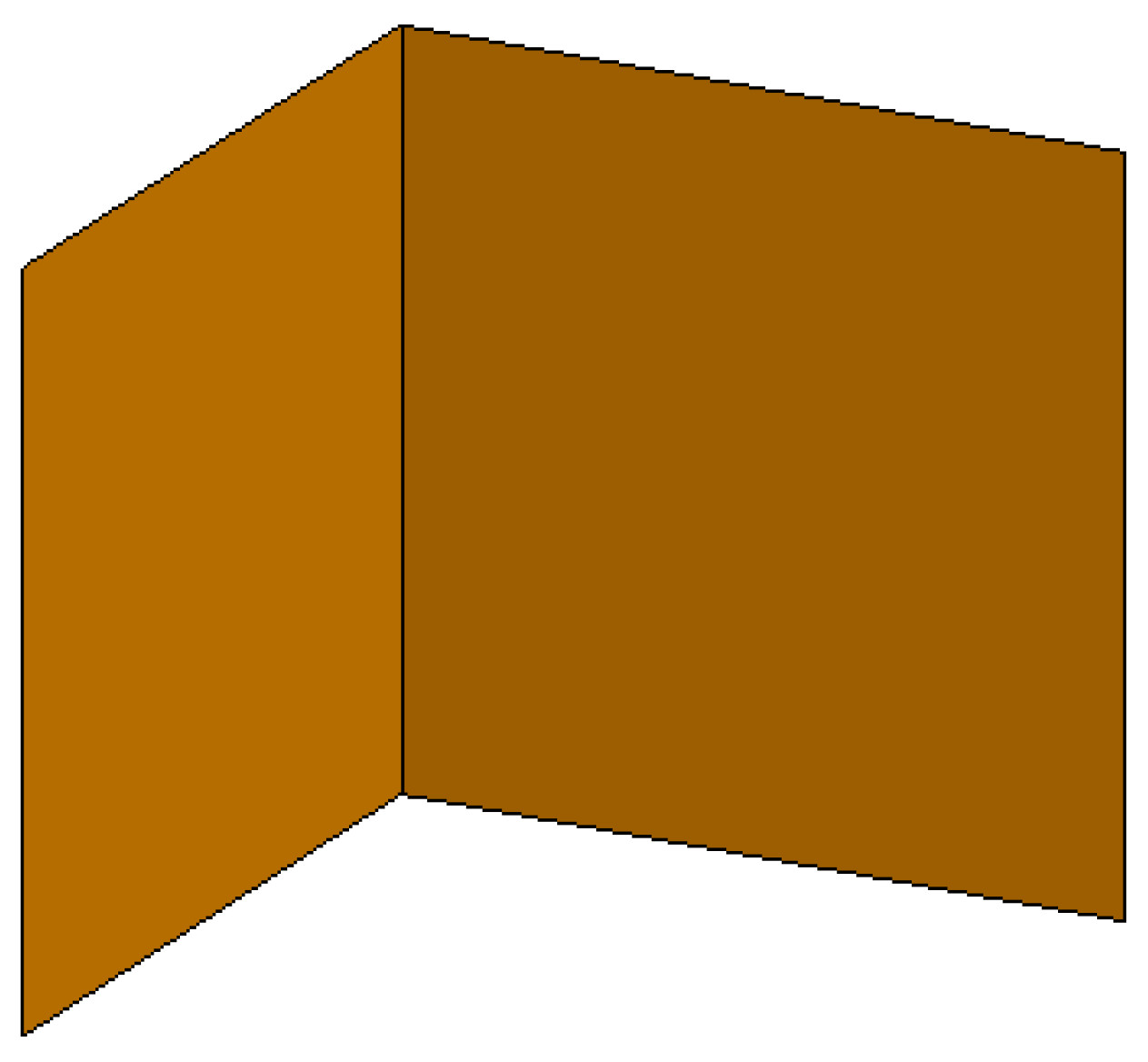

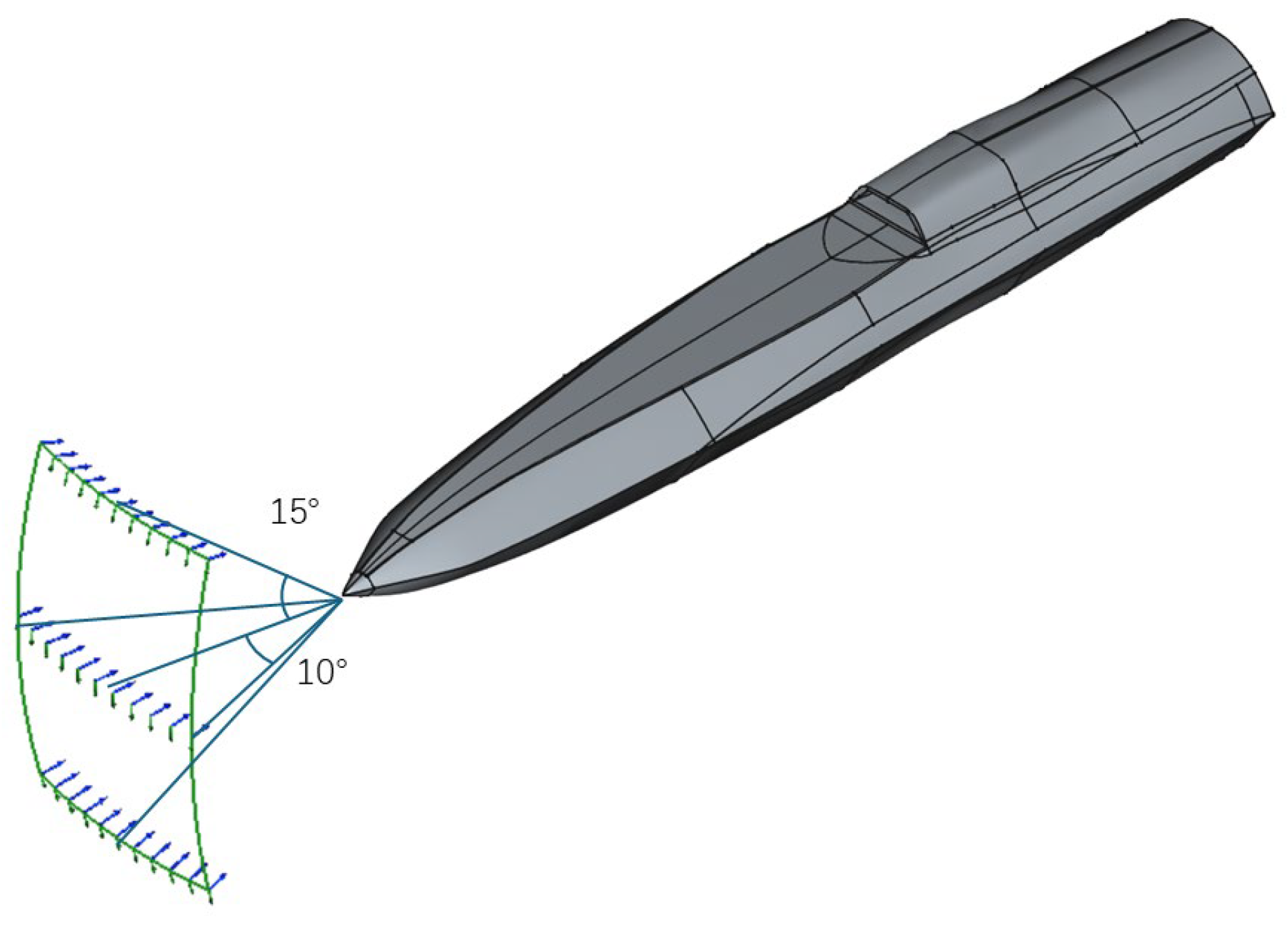

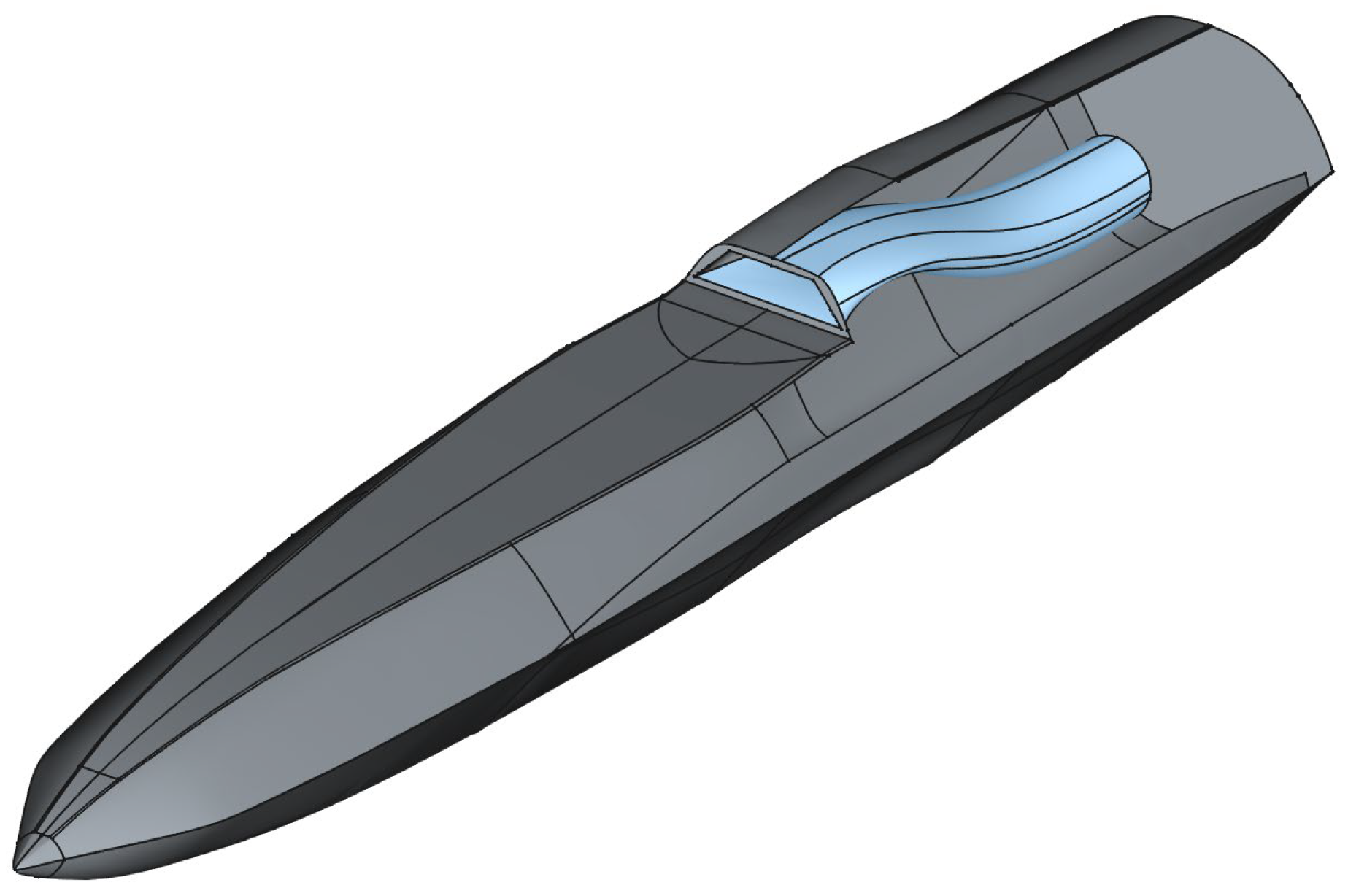

2]. The S-shaped inlet has become a typical design for UAV inlets because it effectively conceals the engine blades, a dominant source of radar scattering, and supports a compact integrated layout.

However, the unique structure of S-shaped inlets creates a fundamental design conflict between aerodynamic and stealth performance: although greater curvature and more turns enhance stealth performance, they simultaneously worsen flow distortion and pressure loss at the engine face. Therefore, aerodynamic-stealth optimization design should be carried out to obtain an inlet with superior aerodynamic and stealth performance. High-fidelity evaluations of both aerodynamic and stealth performance are computationally expensive. Surrogate-based optimization methods address this by constructing approximate models to replace time-consuming simulations, thereby significantly enhancing optimization efficiency [

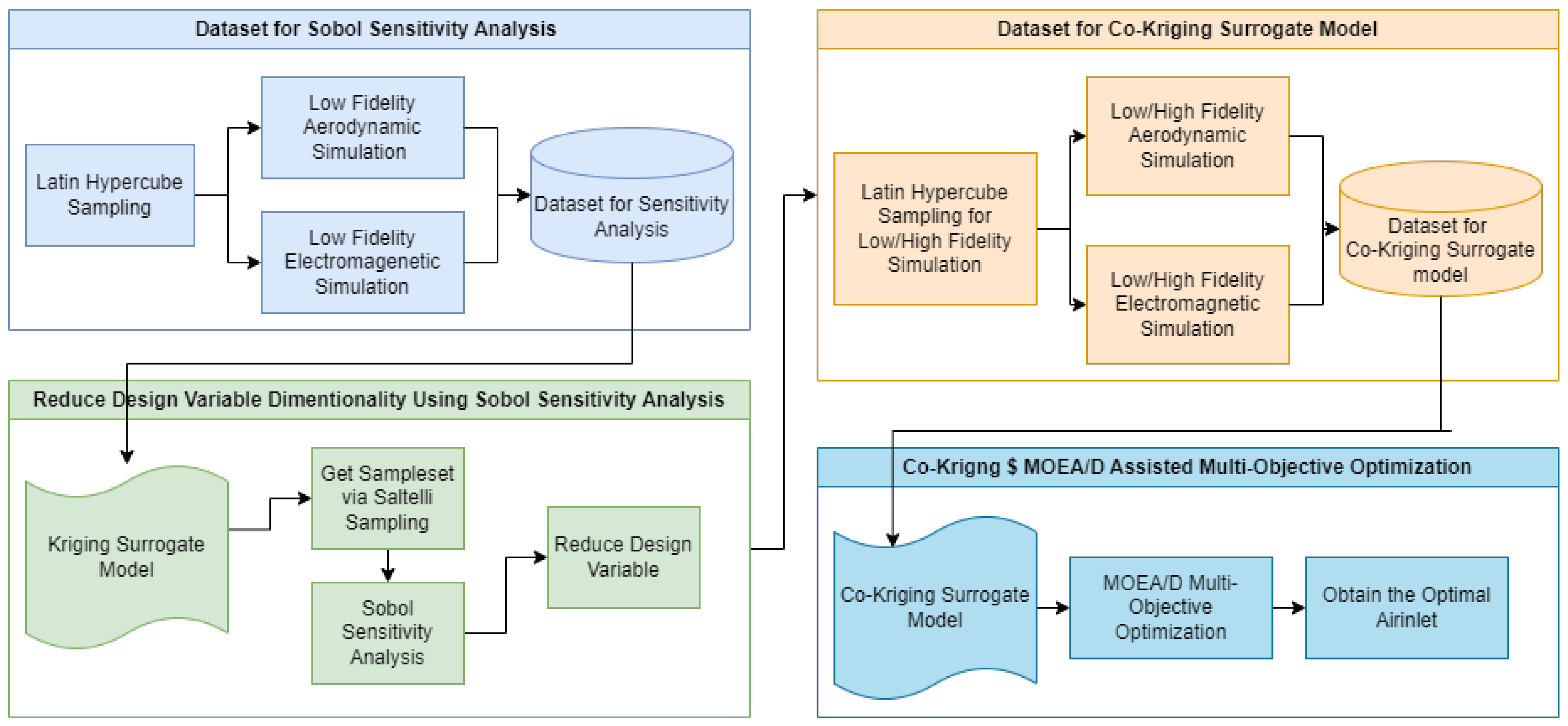

3]. As the dimensionality of design variables grows and performance requirements for UAVs become more demanding, a large number of high-fidelity samples are required to adequately cover the design space and ensure the accuracy of traditional surrogate models, thus imposing substantial computational demands [

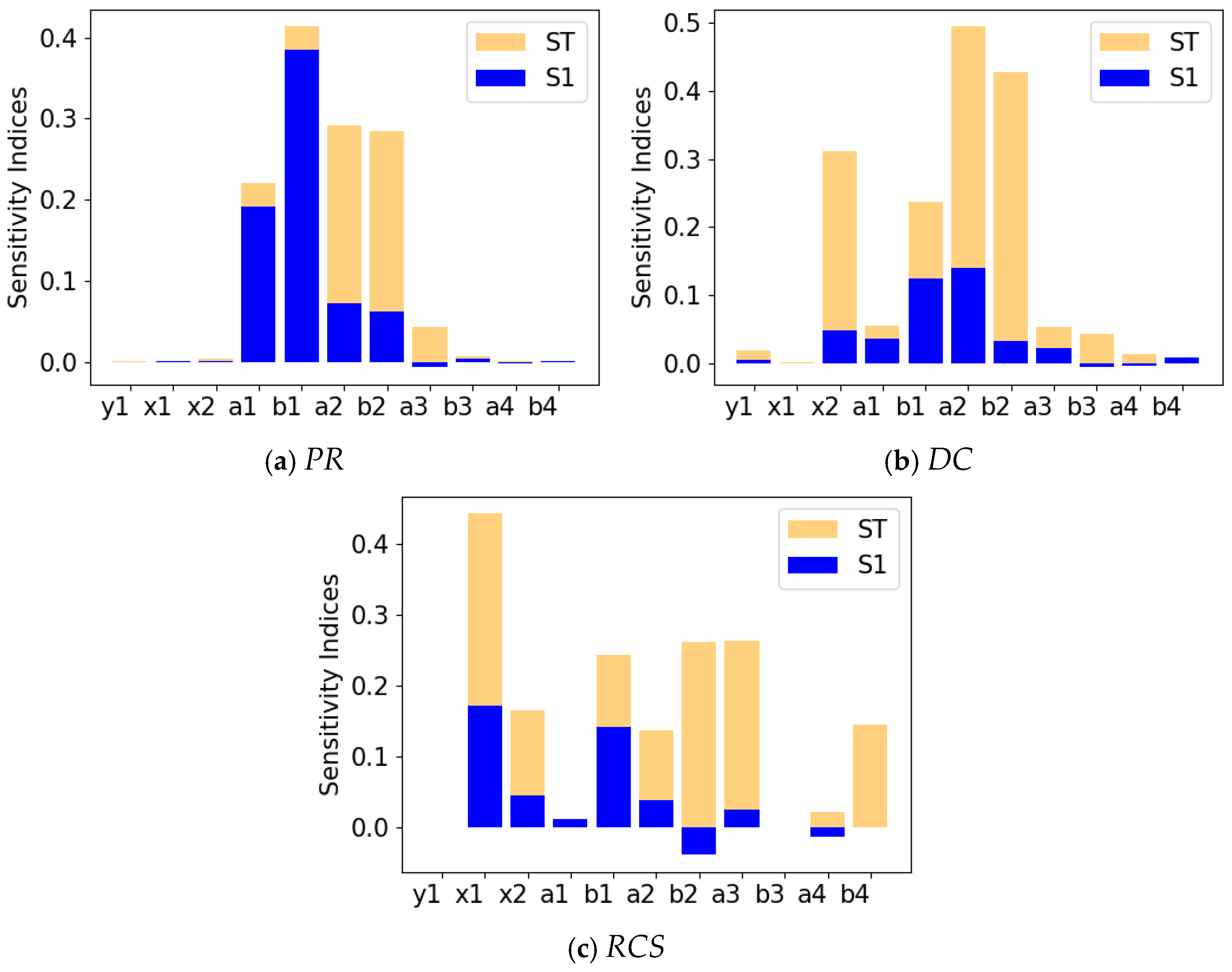

4]. In response to these issues, on the one hand, parameter sensitivity analysis can be used to examine the contribution of input parameters to output parameters of the model, and the design parameters with minor contribution can be eliminated to reduce the dimension of design parameters [

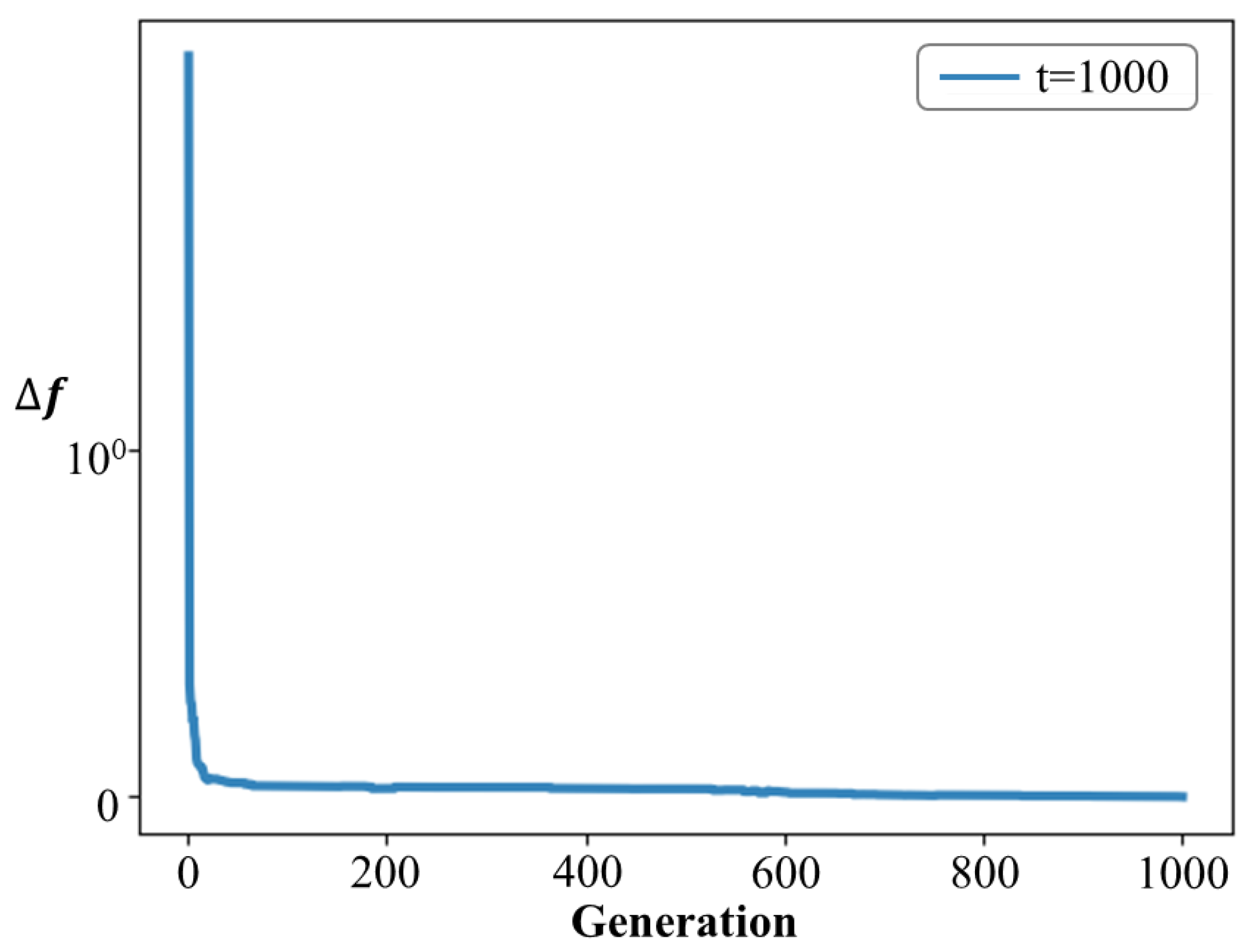

5]. On the other hand, a Multi-fidelity Surrogate Model method can be used to fuse a small number of high-fidelity samples and a large number of low-fidelity samples to build a surrogate model with comparable accuracy at a lower computational cost to support the optimization process effectively [

6].

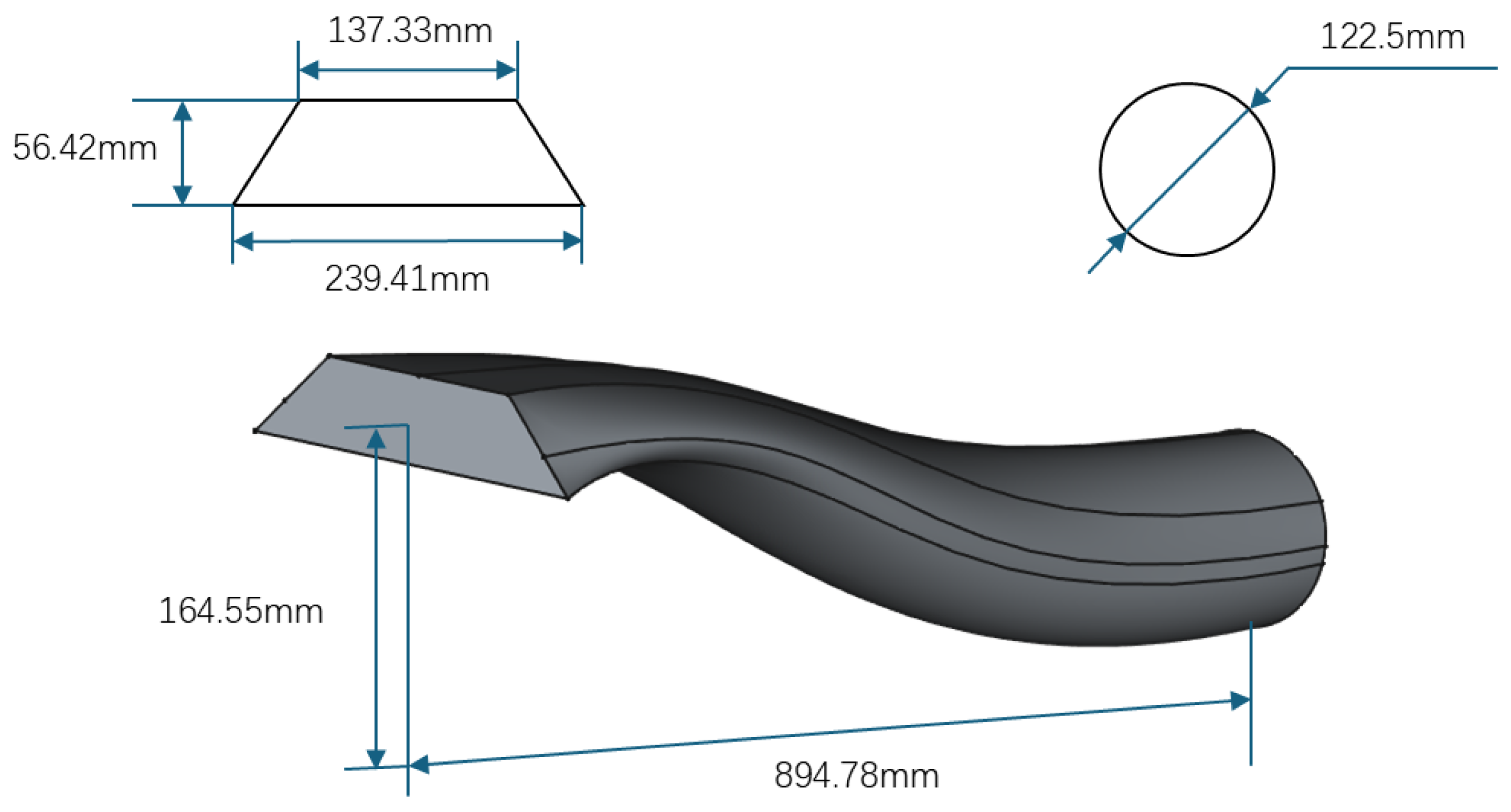

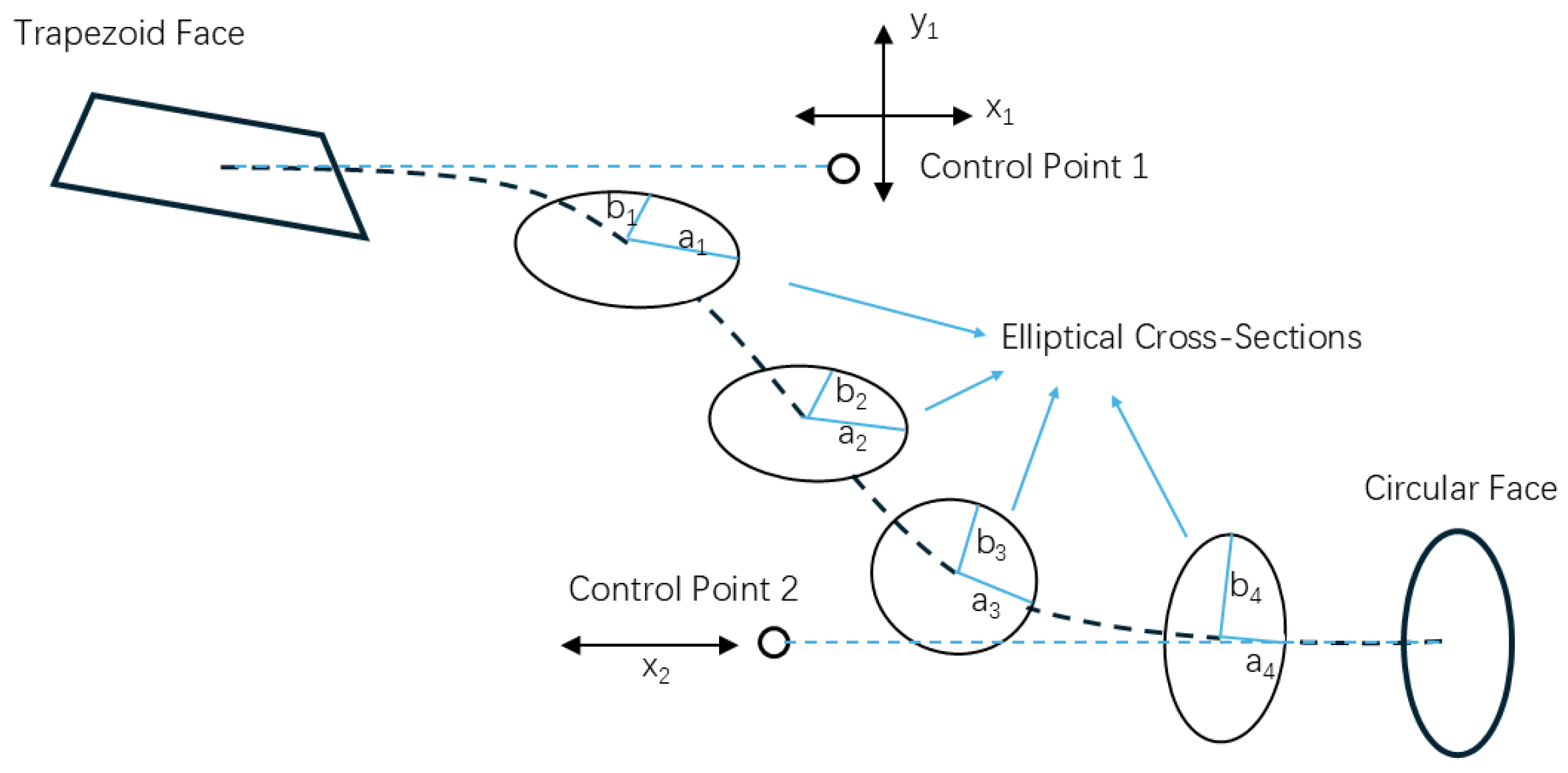

From the aspect of inlet optimization, A considerable amount of research has focused on aerodynamic performance. Aniket et al. [

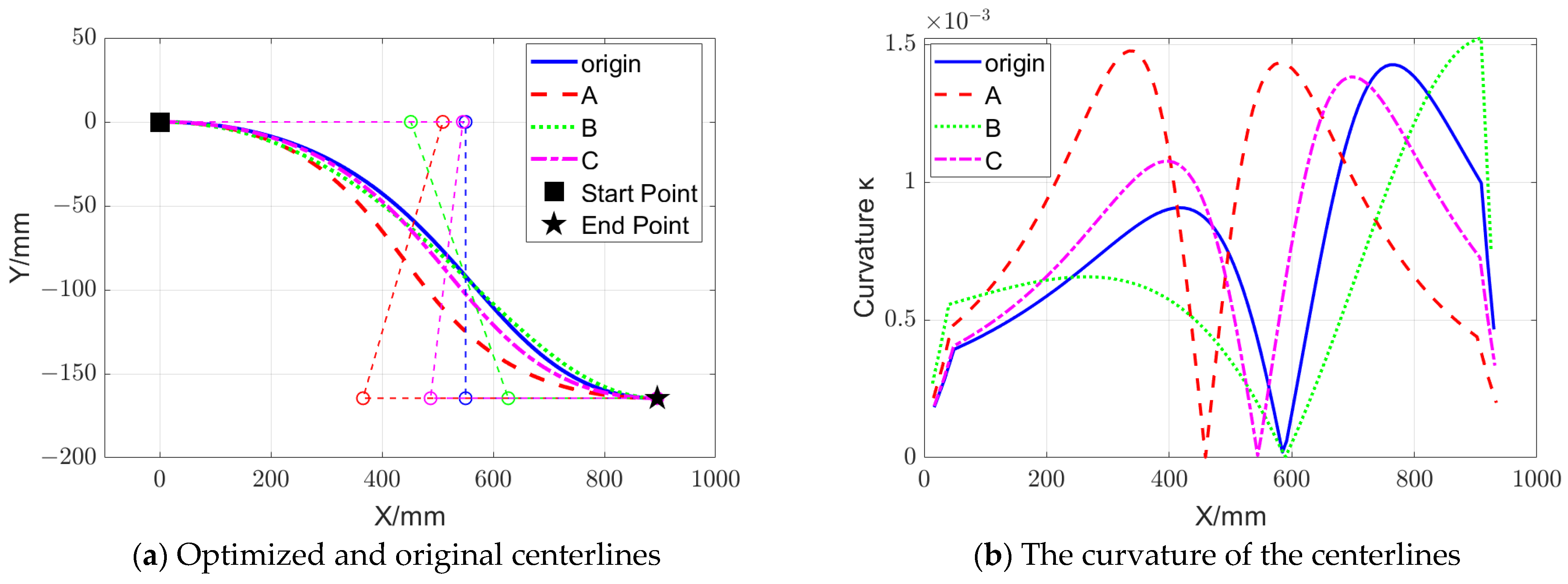

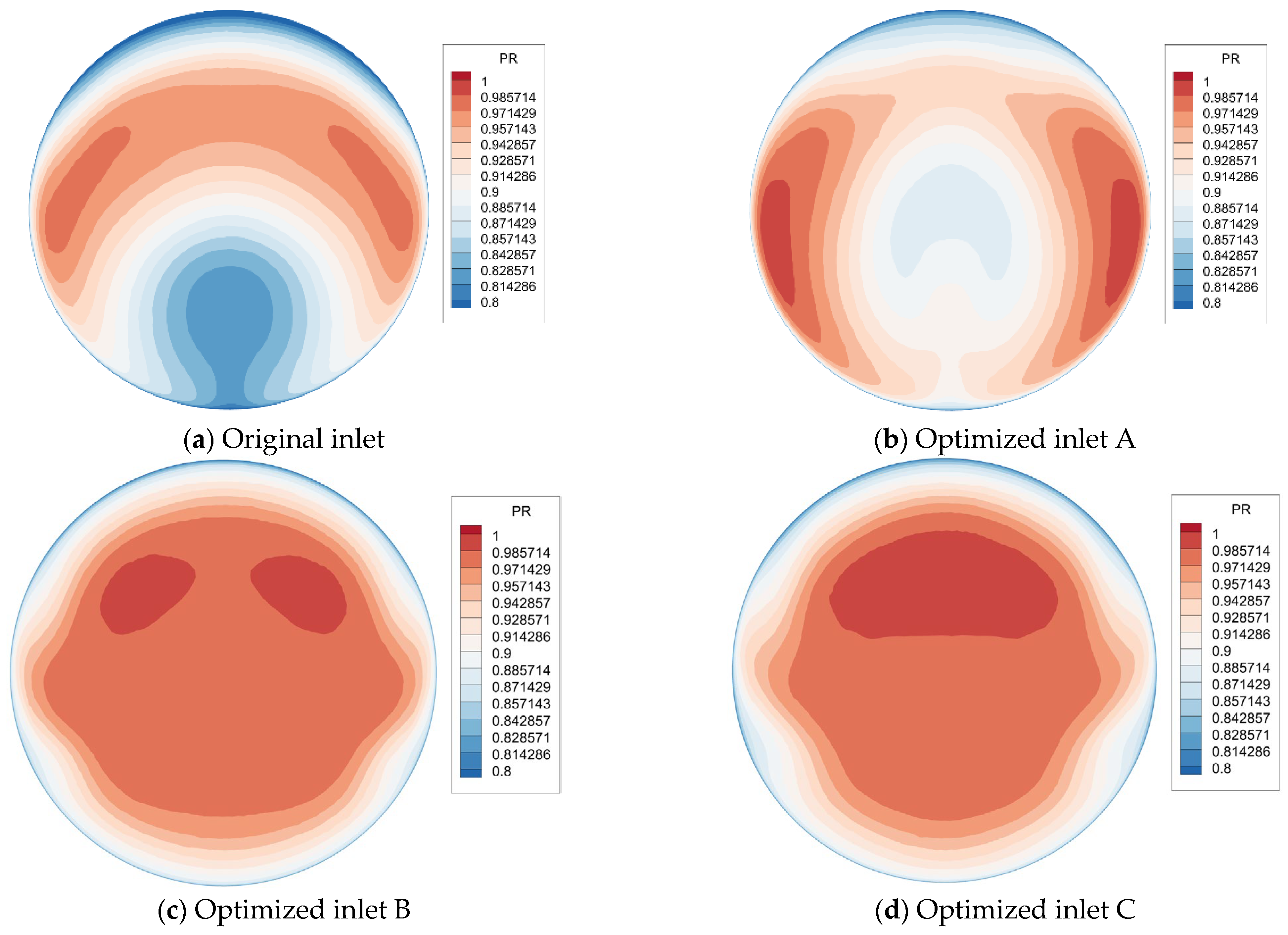

7] conducted optimization design of a 915 mm S-shaped inlet at Ma = 0.3. They combined the MOGA-II algorithm with CFD simulations, optimizing the total pressure recovery coefficient (

PR) and total pressure distortion coefficient (

DC) by adjusting the major and minor axes of elliptical cross-sections. Hyo et al. [

8] performed centerline shape optimization for an approximately 1070 mm subsonic S-shaped inlet under conditions of Ma = 0.6 and Re = 2.6 × 10

6. They constructed a stochastic Kriging model to replace complex simulations, ultimately achieving significant improvements in both

PR and

DC. Liu Lei et al. [

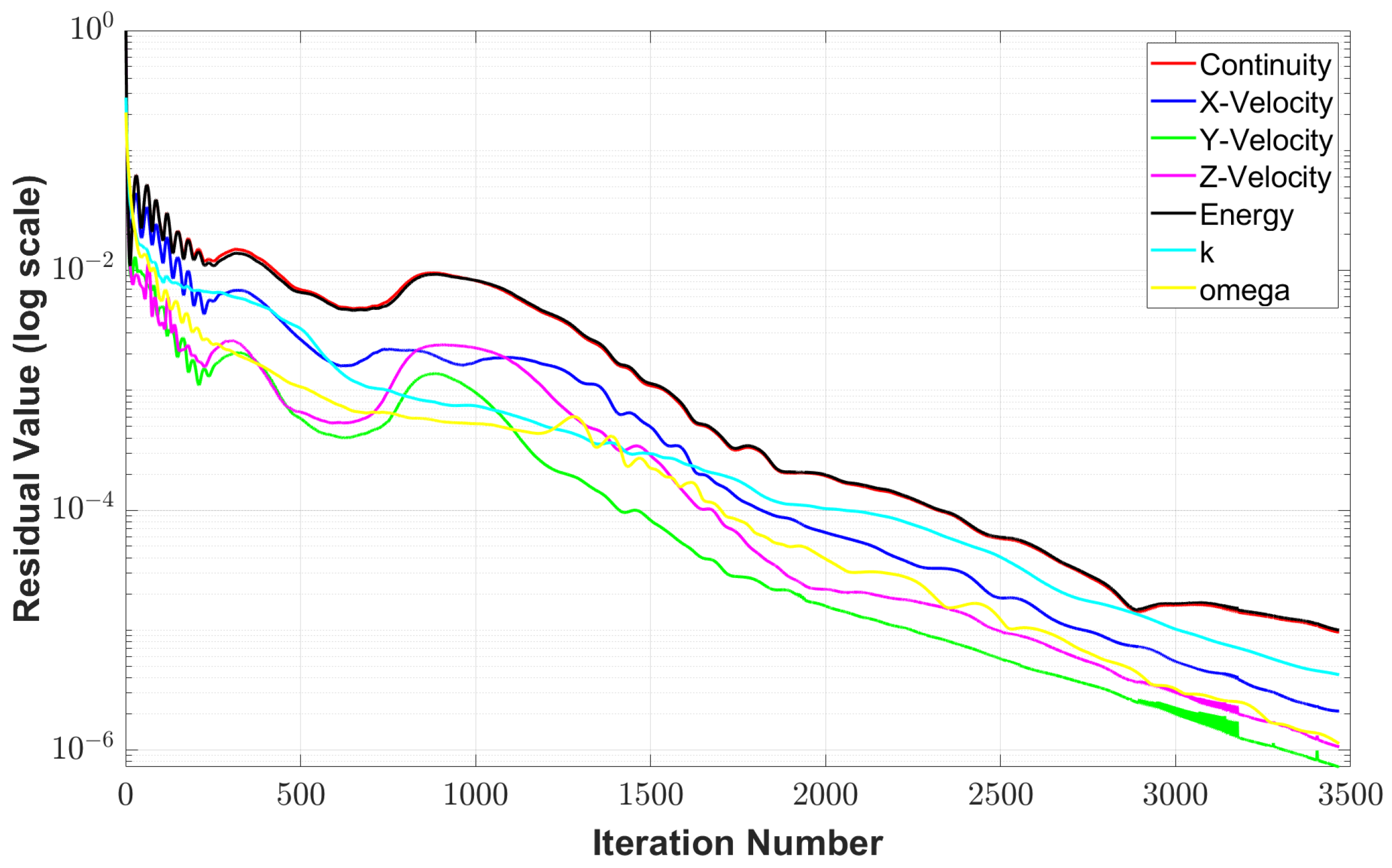

9] carried out design optimization for a 900 mm S-shaped inlet at Ma = 0.53. Through the NSGA algorithm, the optimized inlet showed marked improvement in swirl distortion. Gan [

10] employed a modified k-ω SST turbulence model and constructed an RBF surrogate model to optimize an S-shaped inlet at Ma = 0.6. The optimization resulted in a 16.3% reduction in the

DC and a 1.1% increase in

PR. Zeng Lifang et al. [

11] conducted multi-point and multi-objective optimization for a 195 mm S-shaped inlet at Ma = 0.25 and Ma = 0.7. By combining the NSGA-II algorithm with high-fidelity simulations, the performance of the inlet was effectively enhanced.

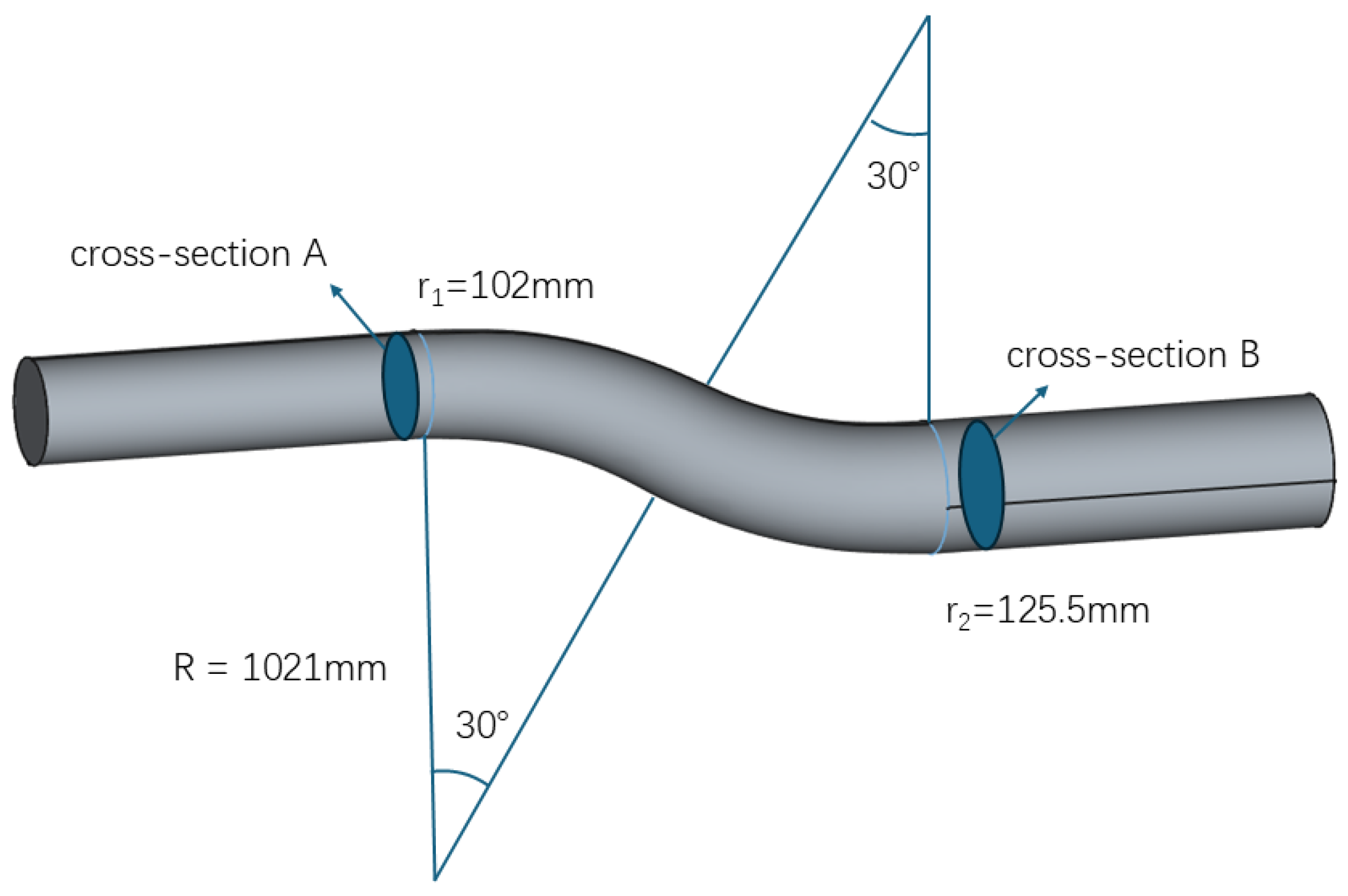

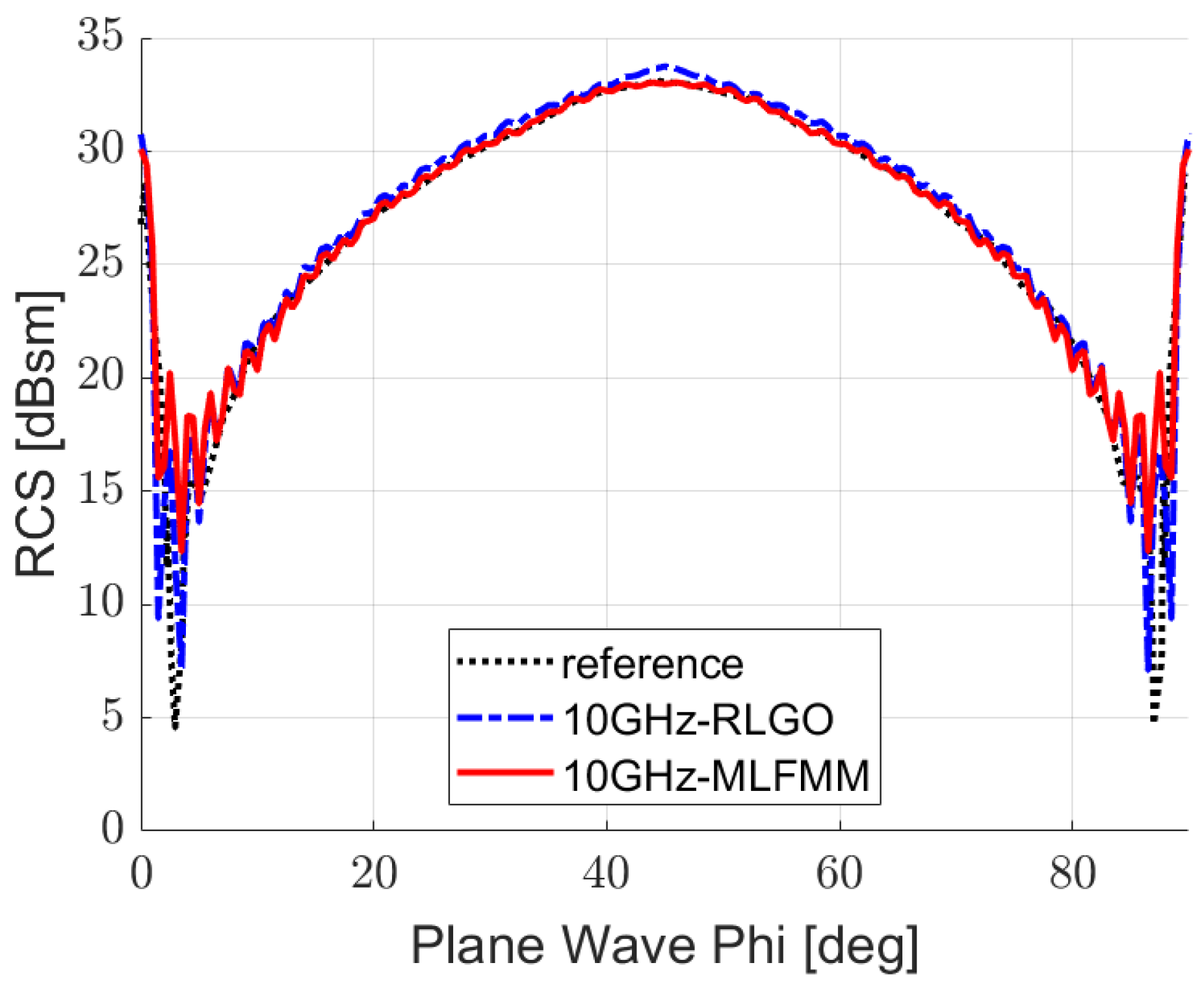

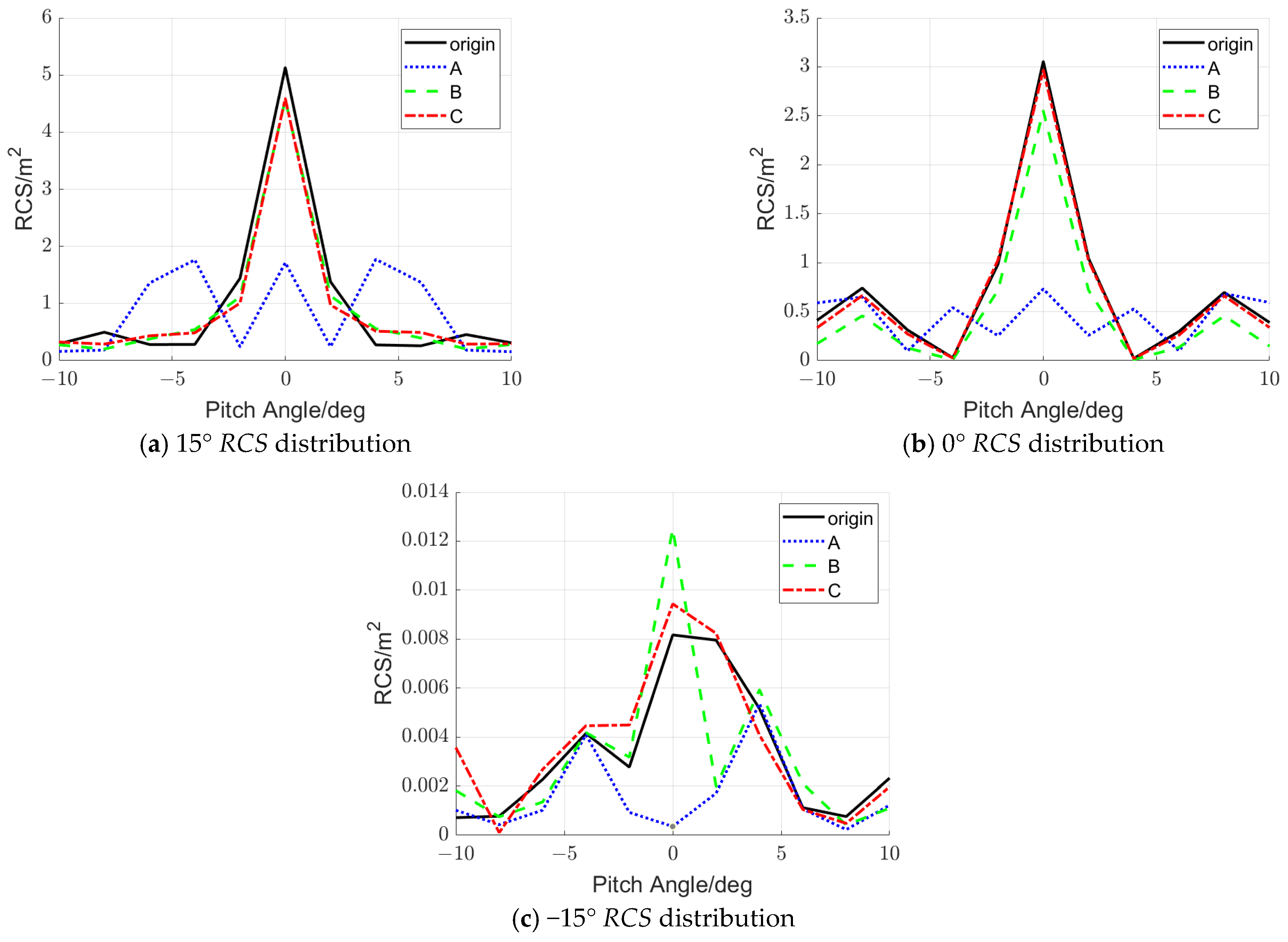

Comparatively, research on the stealth performance of S-shaped inlets is limited. Ji Jinzu et al. [

12] tested a series of 850 mm S-shaped inlets with varying curvature and bending configurations at an incident wave frequency of 10 GHz. Based on the dimensional requirements of a conformal inlet for a flying-wing UAV, Zhang Le et al. [

13] designed multiple 600 mm S-shaped inlets. The Multi-Level Fast Multipole Method (MLFMM) was employed to calculate their

RCS at incident wave frequencies of 1 GHz and 3 GHz. This study revealed favorable cross-sectional area and centerline distribution patterns for the S-shaped inlet that achieve balanced aerodynamic and stealth performance. Deng et al. [

14], recognizing that modern aircraft S-shaped inlets must balance both aerodynamic and stealth performance, employed a gradient-based optimization system named NOPT for the design process. The optimization was performed on a 2732 mm S-shaped inlet under the condition of Ma = 0.8 and an incident wave frequency of 600 MHz. The results demonstrated marked improvements:

PR increased from 0.8265 to 0.9772, while the

DC was significantly reduced from 0.6988 to 0.0235. Furthermore, the average

RCS was decreased from 2.2245 m

2 to 1.2620 m

2.

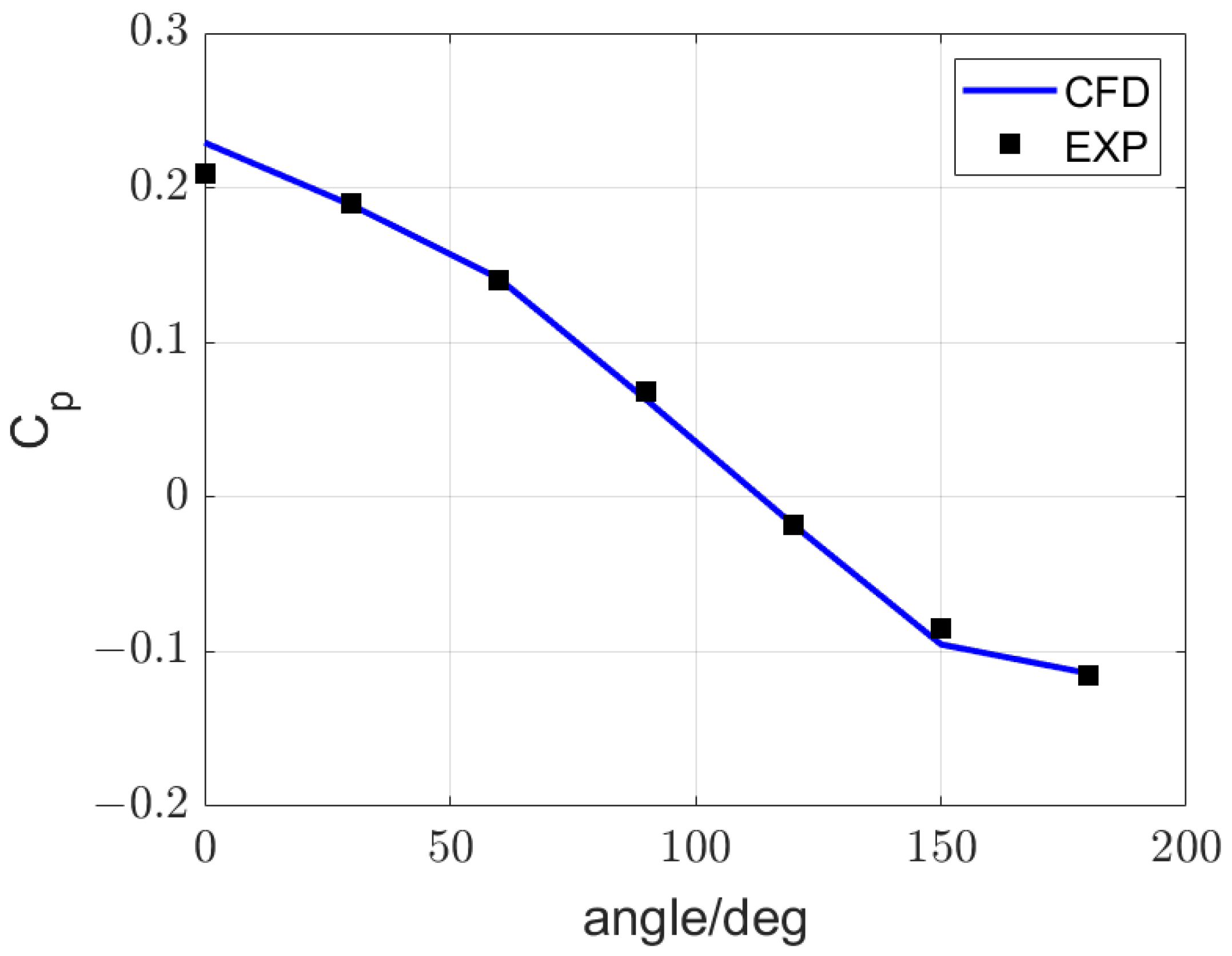

To sum up, most of the existing research focuses on aerodynamics or stealth single discipline and lacks systematic work for aerodynamics and stealth joint optimization. In the evaluation of stealth performance, there is a significant disparity in computational resource consumption between high-fidelity and high-efficiency simulations. On the other hand, stealth characteristics are highly sensitive to geometrical variations. Consequently, blindly employing low-fidelity methods for the sake of efficiency may lead to a substantial discrepancy between the optimized design and its actual performance. The application of variable-fidelity surrogate models to the aerodynamic–stealth coupled optimization of inlets can enhance optimization efficiency while maintaining considerable accuracy. This paper presents a joint optimization of aerodynamics and stealth of the S-shaped inlet. Firstly, a parametric geometric model of the S-shaped inlet is established. The dimensionality of the design space is then reduced through parameter sensitivity analysis. Subsequently, a multi-fidelity surrogate model is constructed and utilized for multi-objective optimization, which efficiently yields an S-shaped inlet with both good aerodynamic and stealth performance.