Evaluation of Flight Training Quality for the Landing Flare Phase Using SD Card Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Phase Delineation, Data and Methods

2.1. Phase Delineation

2.2. Data

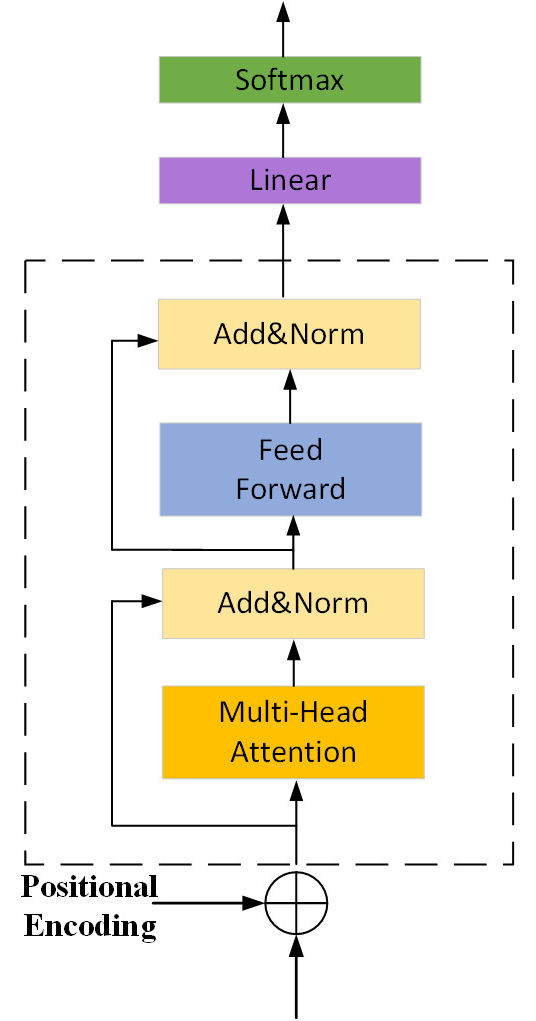

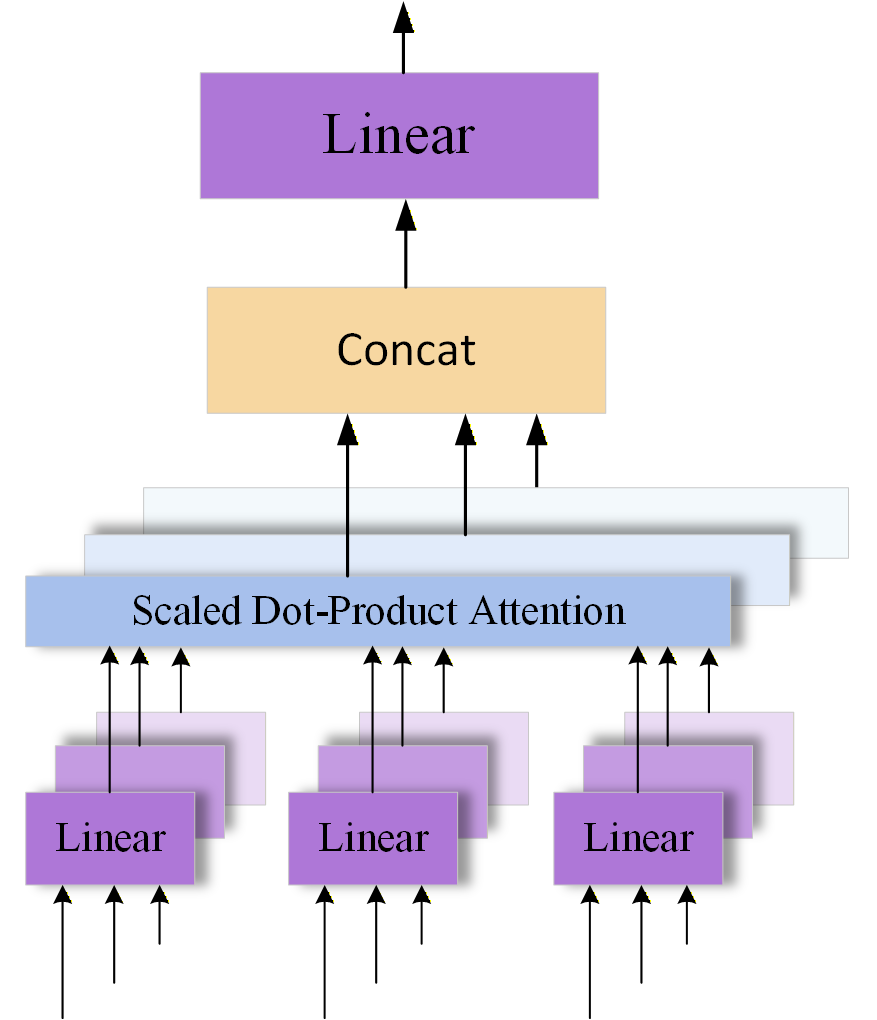

2.3. Standard Time Series Generation Based on Transformer Encoder

2.4. DTW Similarity Measurement Based on Mahalanobis Distance

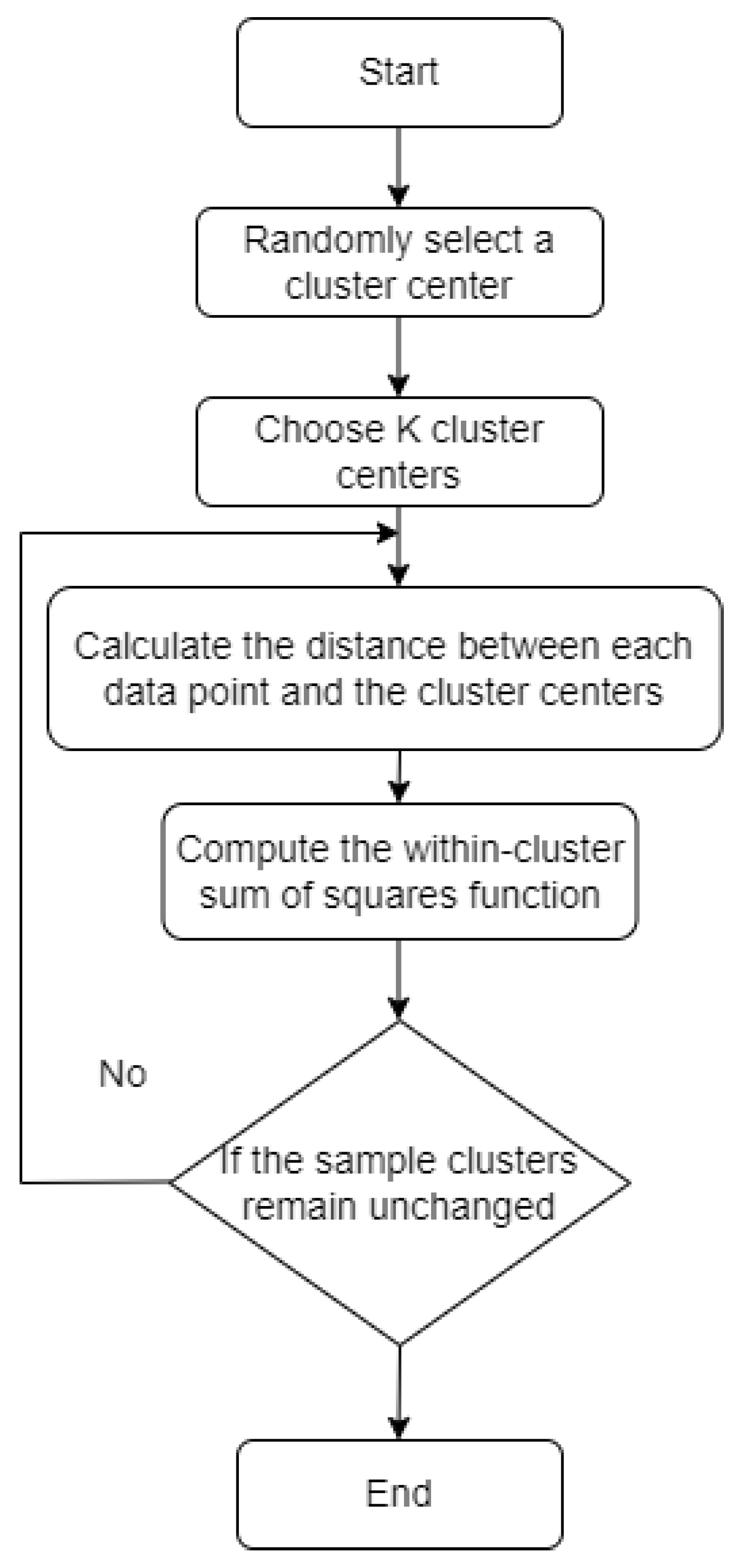

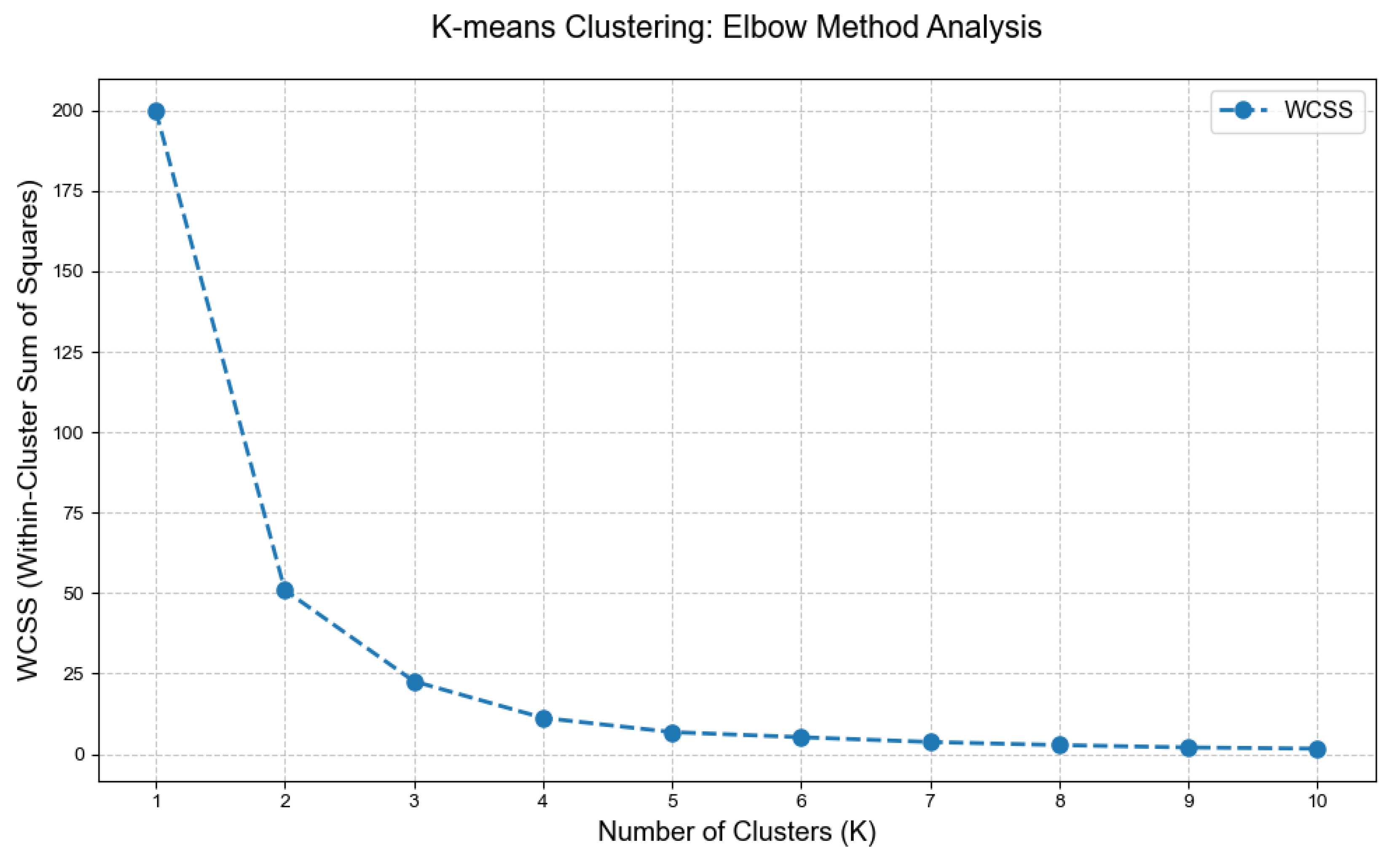

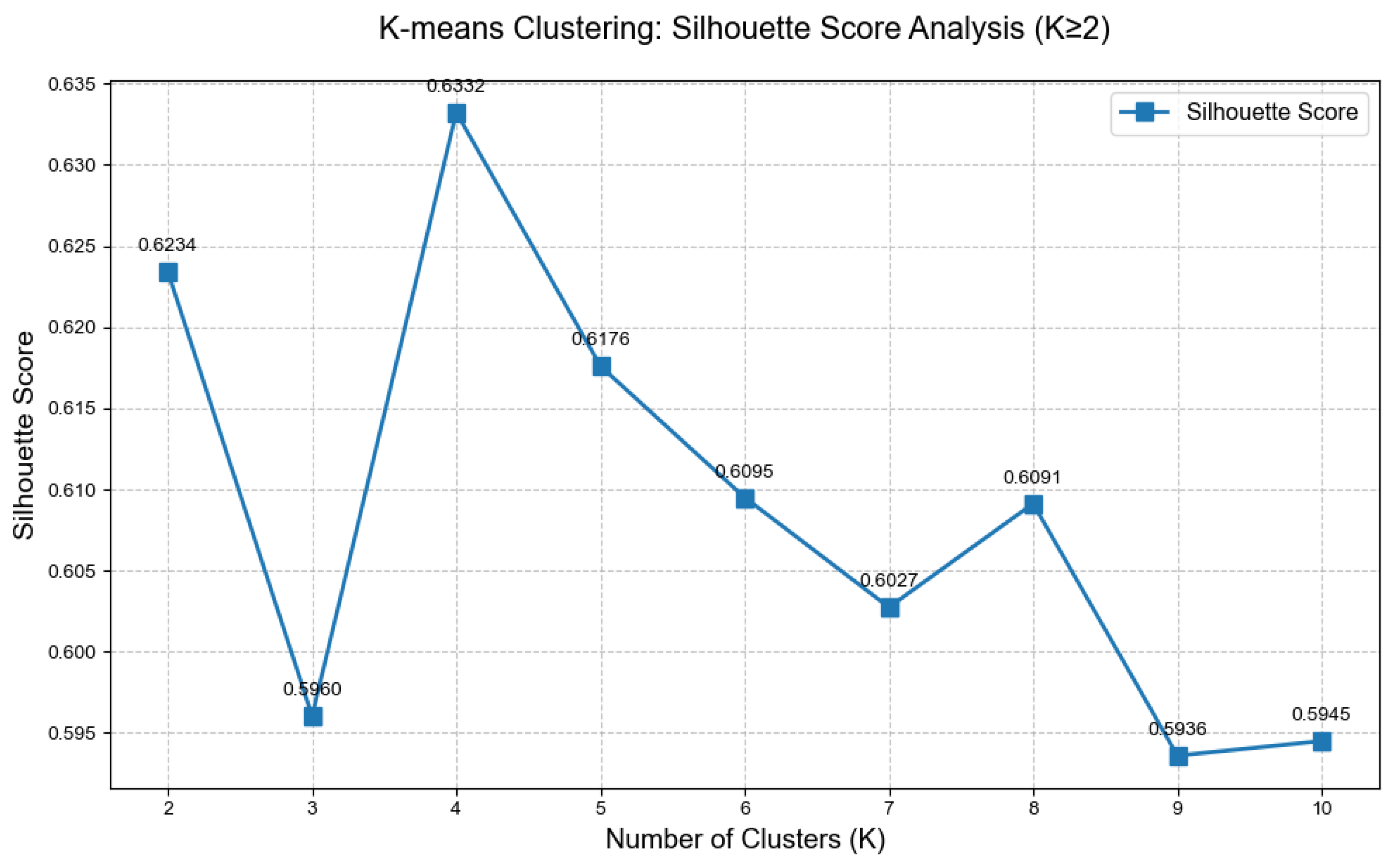

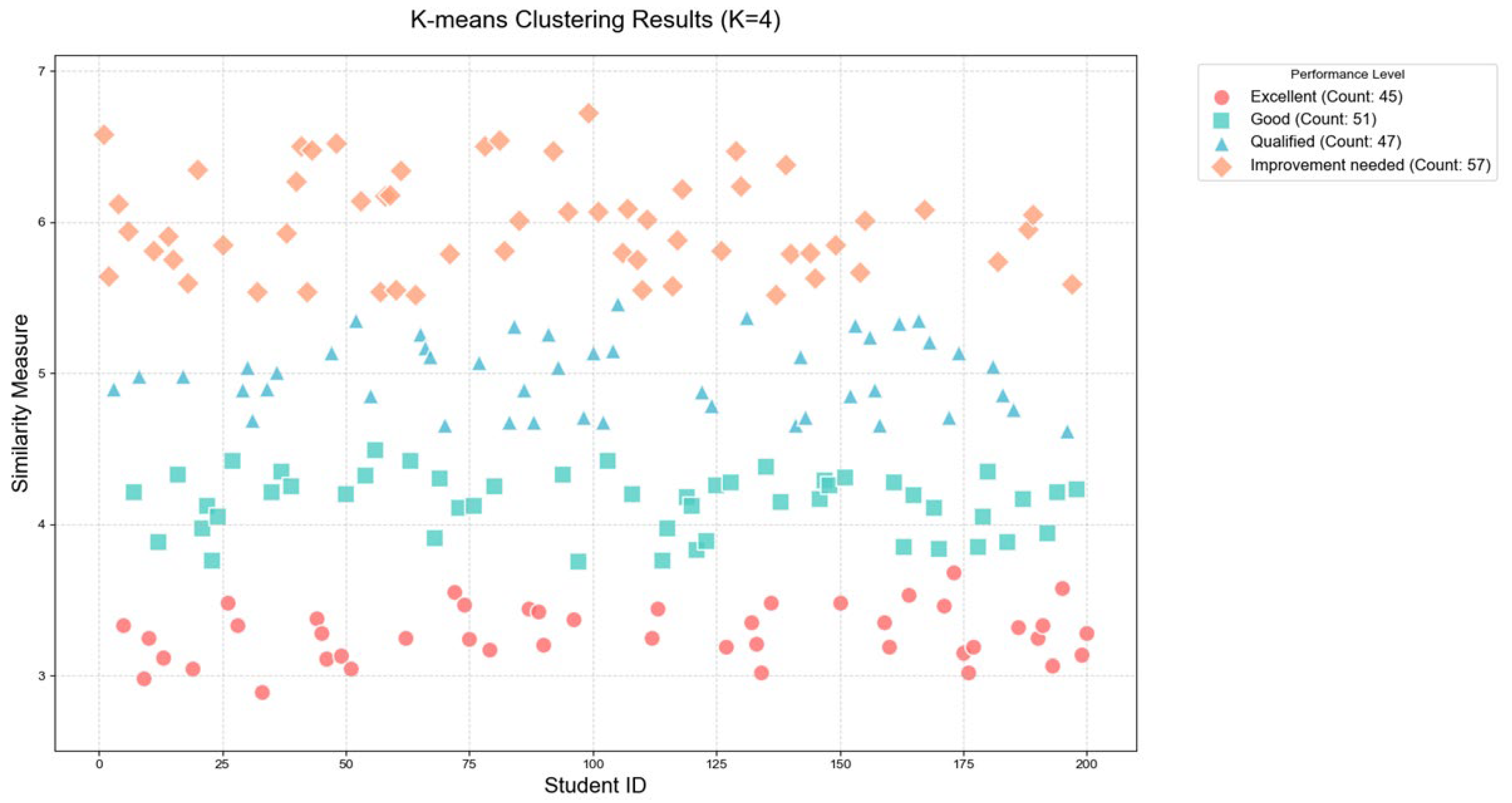

2.5. Landing Quality Evaluation Based on K-Means Clustering

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Quality Clustering and Weak Parameter Identification Results

3.2. Comparative Analysis and Discussion of Consistency with Instructor Ratings

- The primary disagreement centered on the algorithm’s “Improvement Needed” group. All trainees in this group received instructor ratings of 3 or 4, rather than the failing scores of 1 or 2. This stems from the differing evaluation logics: the algorithm identified them as the relatively weakest within the cohort, whereas the instructors deemed them to have met the absolute minimum requirements of the curriculum. While the operational techniques of these trainees likely satisfied all key qualification criteria in the Training Syllabus from an absolute pass/fail standpoint, the algorithm acutely revealed their relative disadvantage within the group. This provides precise targets for instructional intervention, preventing their technical shortcomings from being masked by a “pass” label.

- The average instructor rating for the “Improvement Needed” group (3.59) was higher than that for the “Qualified” group (3.26), further illustrating the difference in assessment logic. Although algorithmically classified as relatively weaker performers, the majority of trainees in the “Improvement Needed” group (33 individuals) were rated by instructors as having met the absolute standard for “Good” (score of 4), thereby elevating the group’s average score. This discrepancy is further accentuated by the differing evaluation scopes: instructors’ comprehensive assessments include the ground roll phase, while the algorithmic analysis is confined solely to the landing flare phase. This clearly demonstrates the algorithm’s capability to reveal relative technical deficiencies during the landing flare phase that remain concealed under the absolute evaluation framework. Even when instructors assign a “Good” rating to trainees in the “Improvement Needed” group, the algorithm accurately identifies them as requiring prioritized assistance within the cohort.

- Cases where trainees received favorable algorithmic ratings but lower instructor evaluations are also noteworthy. Specifically, we identified 10 trainees algorithmically rated as “Good” but instructor-rated as 3 (“Qualified”)—the most typical “algorithm-high, instructor-low” cases. From the algorithm’s perspective, their landing operations showed moderate deviation from the standard sequence (similarity metric ~3.75–4.49), placing them in the upper-middle tier of the cohort. However, instructors judged their performance as merely “Qualified”. Furthermore, 16 trainees were rated “Excellent” by the algorithm but only “Good” (rating 4) by the instructors. These algorithmically top-tier trainees (similarity metric ~2.89–3.68) did not receive the highest instructor rating. A key reason is that instructor evaluations encompass the entire landing phase, including the ground roll, and incorporate assessment criteria beyond technical manipulation, such as Crew Resource Management skills (e.g., communication, workload management). The algorithmic clustering, in contrast, is based solely on flight parameters, excludes non-technical skills, and does not include the ground roll phase. Therefore, for these algorithmically “Excellent” trainees, the lower instructor rating might be due to deficiencies in non-technical factors like passive communication, less satisfactory performance during the ground roll, or potentially higher standards and expectations held by the instructors, who thus refrain from awarding the top score.

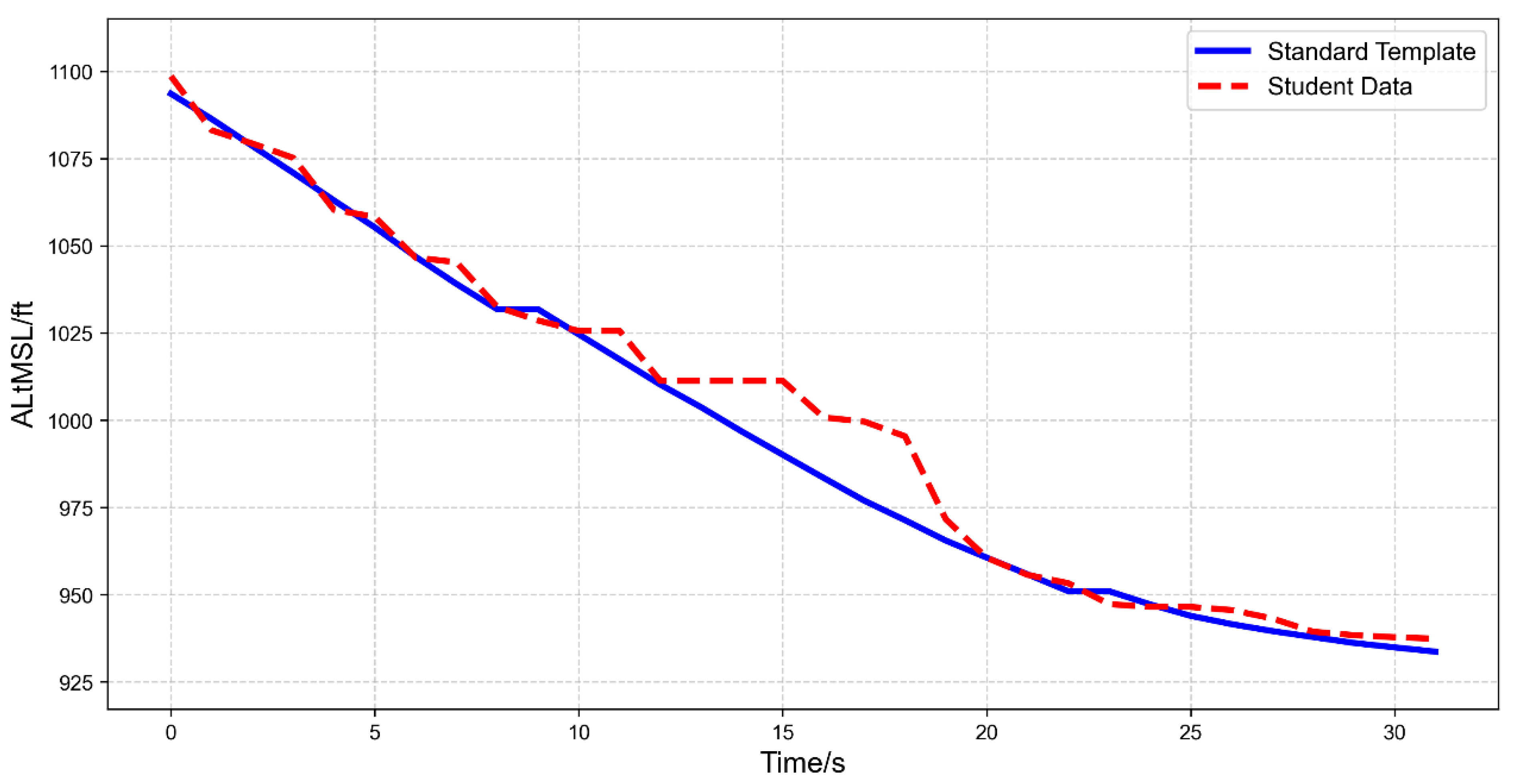

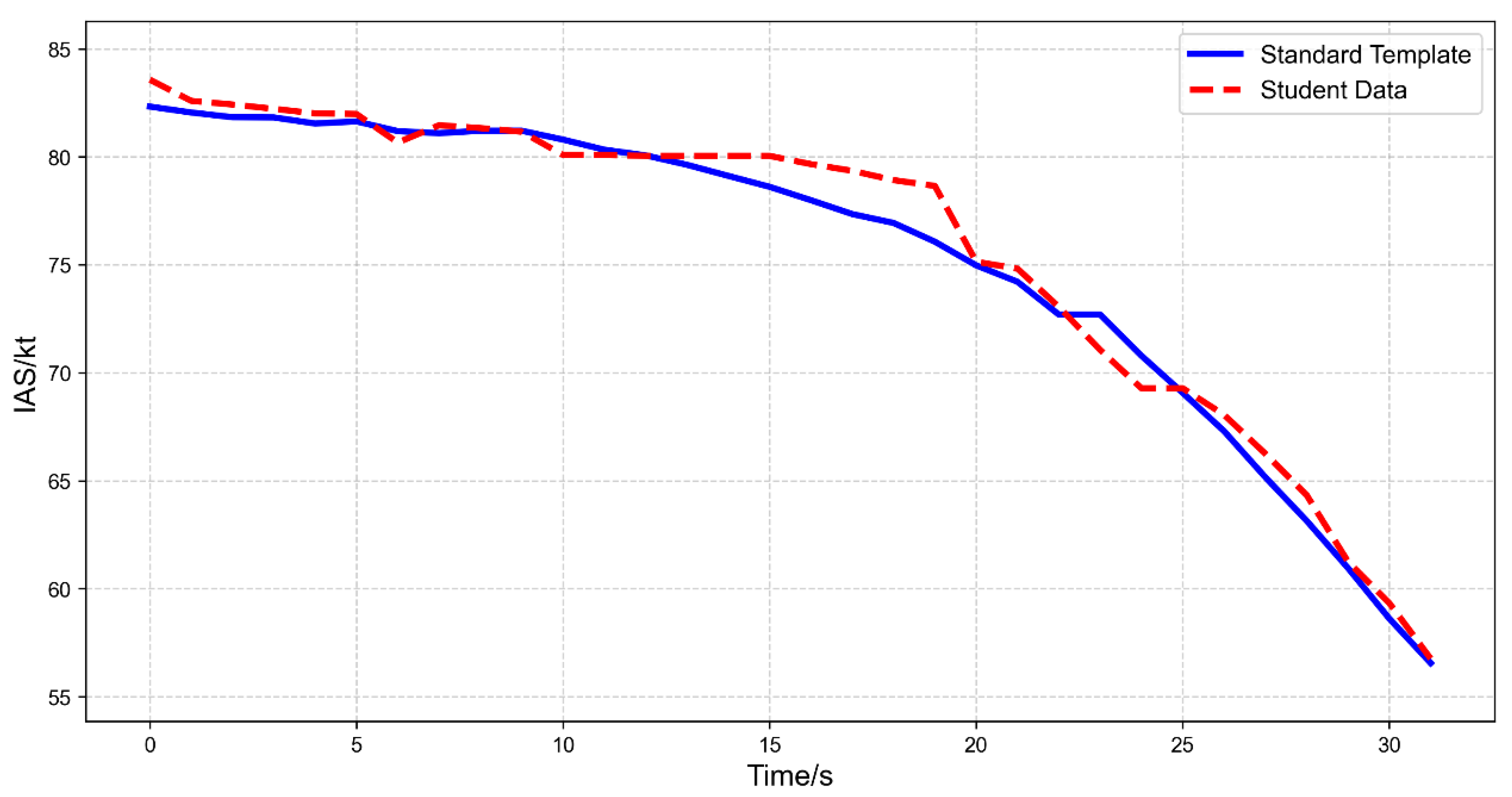

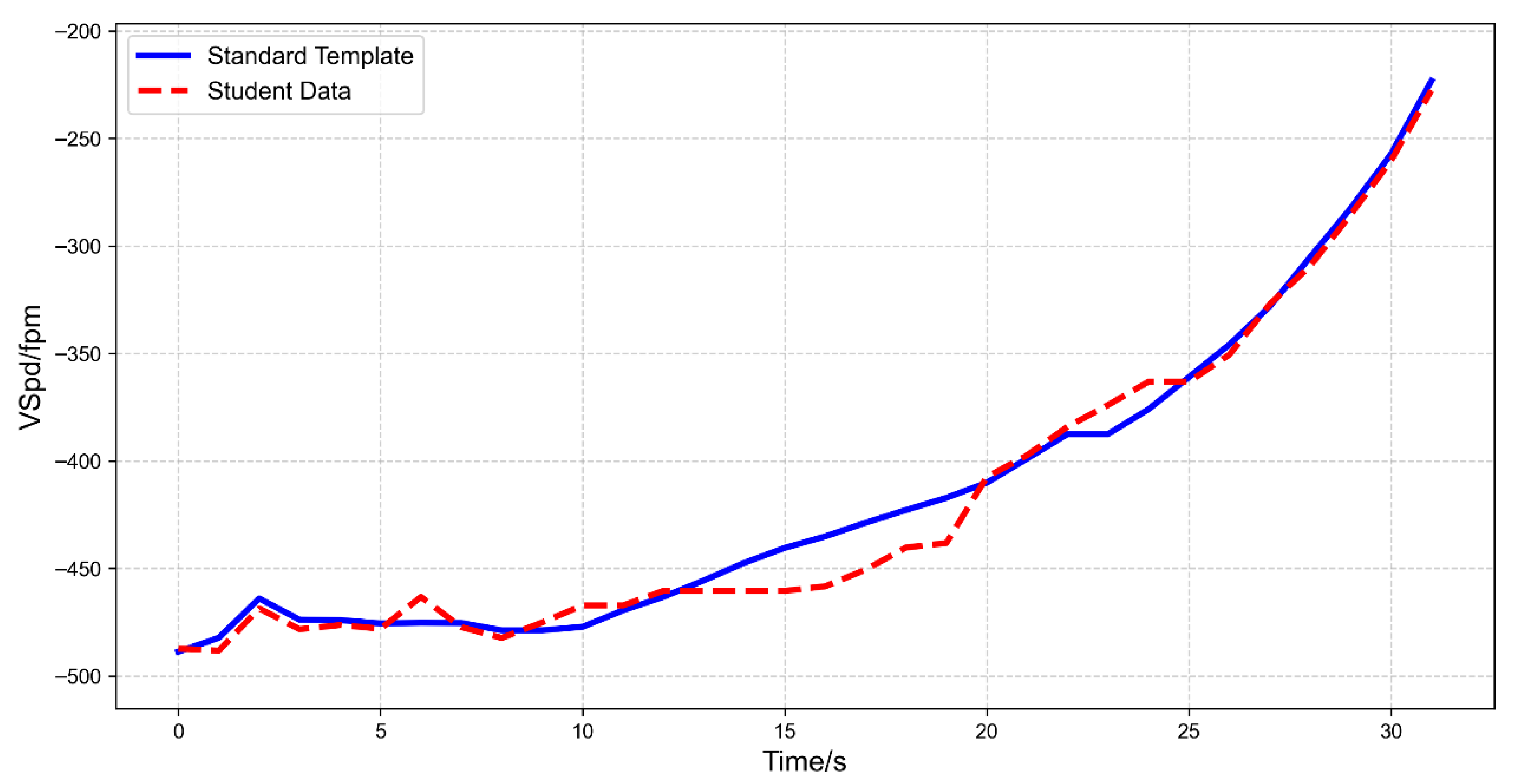

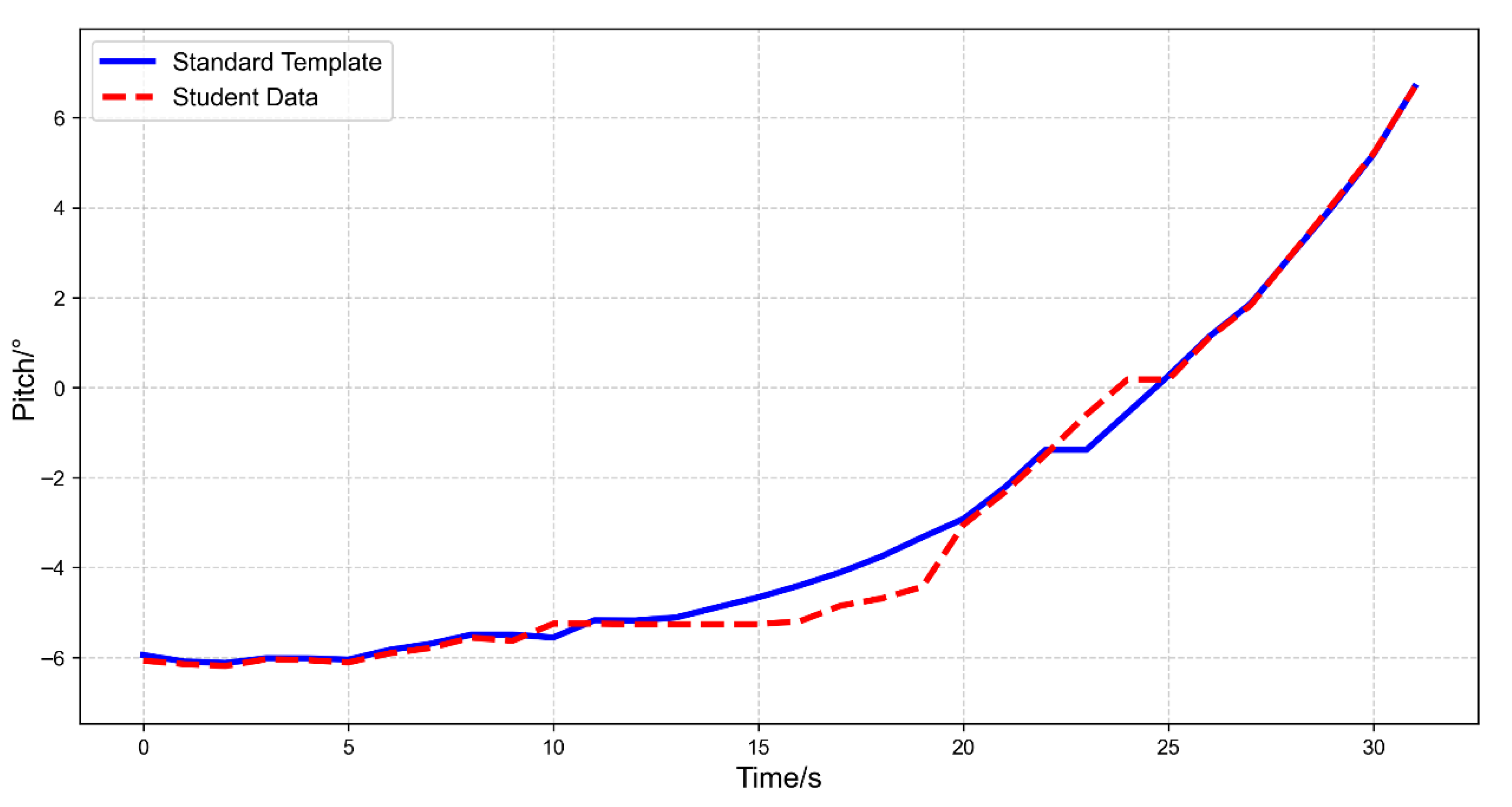

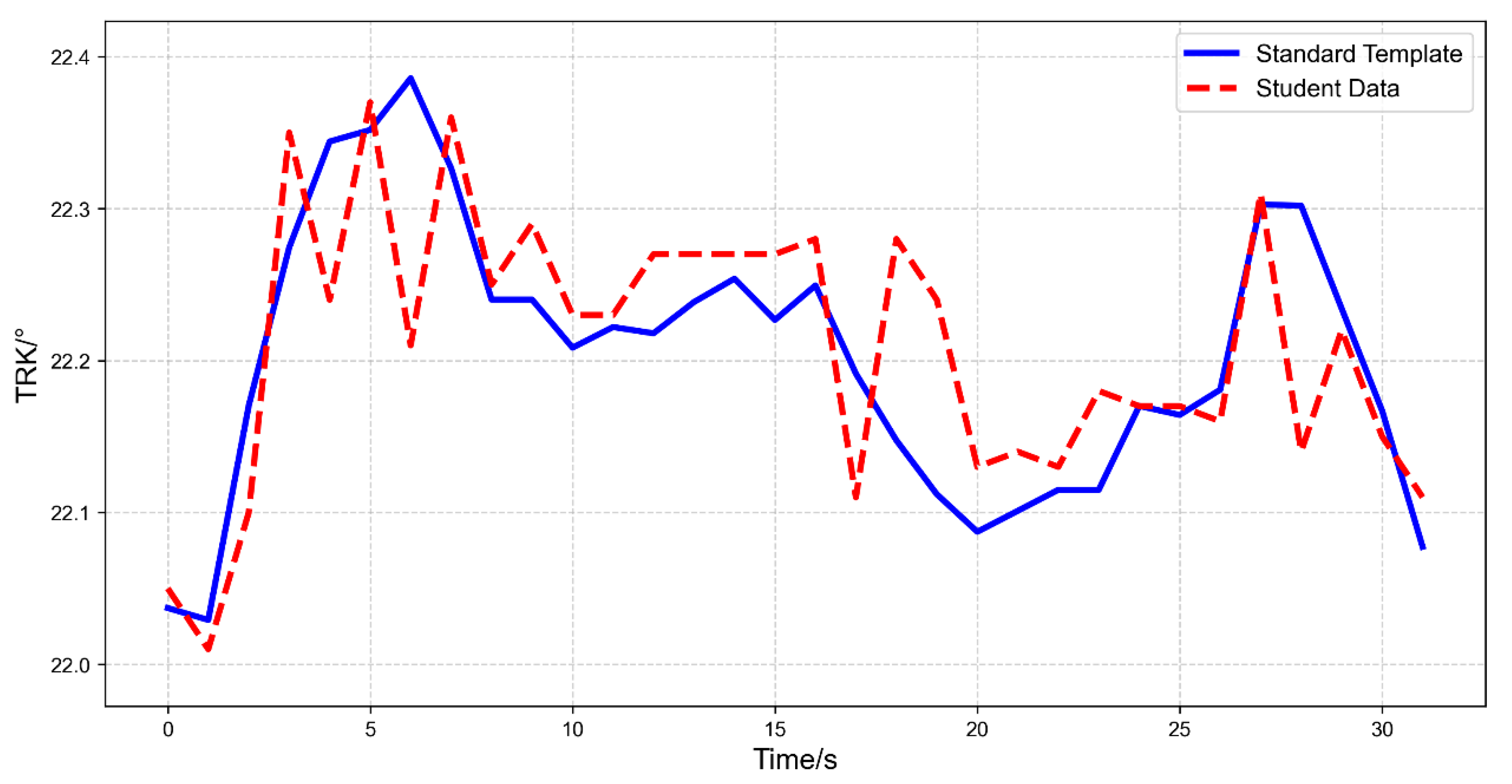

3.3. Individual Case Analysis Using Parameter Curves

4. Conclusions and Future Work

- (1)

- Scope Limitations: Data collection for this study was confined to a single aircraft type and a single airport, with meteorological conditions filtered to control for external variables. While this design facilitates focused analysis of trainees’ fundamental maneuvering skills during the initial research phase, the generalizability and broader applicability of the conclusions require further validation. Future work will aim to expand the scope by incorporating multiple aircraft types, diverse airport characteristics (e.g., runway length), and varied meteorological conditions (e.g., crosswind conditions) to build a more robust evaluation system that meets the complex demands of actual flight training.

- (2)

- Relativity of Evaluation Criteria: It is important to note that the primary contribution of this study lies in providing an objective, quantifiable, data-driven evaluation framework. This framework can precisely identify a trainee’s relative position within the cohort and their individual weaknesses, which is highly valuable for personalized training guidance. However, this study essentially constitutes a relative assessment method based on a specific trainee population. The evaluation results reflect a trainee’s relative standing within the group rather than an absolute benchmark of skill. Therefore, the current assessment outcomes should be integrated with the qualitative evaluations of flight instructors to form a more comprehensive and fair judgment. This method is more suitable for the horizontal comparison and stratification of trainees within the same training batch, enabling the precise allocation of training resources, rather than for the absolute measurement of trainee capability across different training cycles. To enhance long-term repeatability and comparability of assessments, future work will focus on accumulating large-scale data to establish standardized benchmark norms.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boeing. Pilot & Technician Outlook 2023–2042; Boeing Commercial Market Outlook: Seattle, WA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.boeing.com/commercial/market/pilot-technician-outlook/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Li, J.; Sun, H.; Li, F.; Cao, W.; Hu, H. Non-technical Competency Assessment for the Initial Flight Training Based on Instructor Measurement Data. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Big Data Engineering and Education (BDEE 2022), Shanghai, China, 5–7 August 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Meng, G.L.; Wu, H.; Zhou, M. Flight Training Evaluation Based on Dynamic Bayesian Network and Fuzzy Grey Theory. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 42, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Du, D.; Cao, W.; Qian, J. A Quality Evaluation Model for Approach in Initial Flight Training Utilizing Flight Training Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computer Applications Technology, CCAT, Guiyang, China, 15–17 September 2023; pp. 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; You, L. Research on the Evaluation of Flight Manipulation Quality in Cloud Penetration Procedure Training. Flight Mech. 2023, 41, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, T.; Ru, B. Establishment of a Flight Quality Evaluation Model Based on Multi-parameter Fusion. Comput. Eng. Sci. 2016, 38, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, C. A Flight Training Quality Evaluation Model Based on Over-limit Events. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 5074–5080. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Dong, C.; Sun, H.; Ren, Y. A Method of Applying Flight Data to Evaluate Landing Operation Performance. Ergonomics 2019, 62, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Hu, H.; Zhao, M.; Sun, H. Wind Shear Operation-Based Competency Assessment Model for Civil Aviation Pilots. Aerospace 2024, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Research on Quantitative Evaluation Methods for Flight Technology Combining Artificial Intelligence and Data. Aviat. Eng. Prog. 2025, 16, 171–182. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/61.1479.V.20240823.0908.002.html (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Lu, F.; Wei, X.; Chen, H. Research on the Comprehensive Evaluation System of Civil Aviation Pilot Landing Operation Quality. J. Saf. Environ. 2025, 25, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrz, V.; Boril, J.; Vudarcik, I.; Bauer, M. Utilization of recorded flight simulator data to evaluate piloting accuracy and quality. In Proceedings of the NTinAD 2019-New Trends in Aviation Development 2019-14th International Scientific Conference, Chlumec nad Cidlinou, Czech Republic, 26–27 September 2019; pp. 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Shi, Z.; Pan, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, F. Aircraft Flight Quality Evaluation Based on Grey Relational Analysis and XGBoost. Aviat. Eng. Prog. 2025, 16, 74–81. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/61.1479.V.20240701.1402.004.html (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Yuan, W.L.; Lu, C.Y.; Lu, W.; He, S. Flight Quality Evaluation Based on Machine Learning. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 8262–8269. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, L.; Wang, H.; Si, H.; Wang, Y.; Pan, T.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Flight Trainee Performance Evaluation Using Gradient Boosting Decision Tree, Particle Swarm Optimization, and Convolutional Neural Network (GBDT-PSO-CNN) in Simulated Flights. Aerospace 2024, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, H.; Si, H.; Pan, T.; Liu, H. Research on the construction of flight skill evaluation model for flight students based on T-S fuzzy neural network. Manned Spacefl. 2023, 29, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Xiong, Y. Flight maneuver intelligent recognition based on deep variational autoencoder network. Eurasip J. Adv. Signal Process. 2022, 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-C.; Jung, K.-W.; Kim, Y.-W.; Lee, C.-H. Anomaly Detection Method for Missile Flight Data by Attention-CNN Architecture. J. Inst. Control Robot. Syst. 2022, 28, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Jia, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhi, G.; Wang, X. Fault Detection for UAVs With Spatial-Temporal Learning on Multivariate Flight Data. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 2529517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knignitskaya, T.V. Estimate of time series similarity based on models. J. Autom. Inf. Sci. 2019, 51, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.W.; Herrmann, M.; Salehi, M.; Webb, G.I. Proximity forest 2.0: A new effective and scalable similarity-based classifier for time series. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 39, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, R.; Zheng, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, M. A New Time Series Similarity Measurement Method Based on the Morphological Pattern and Symbolic Aggregate Approximation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 109751–109762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Shi, X.; Xiao, Z. Fault diagnosability evaluation method based on DTW timing distance. Acta Armamentarii 2024, 45, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Yang, F.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, M.; Yin, H. Matching method of track dynamic and static inspection data based on DTW. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, W.; Si, X.; Li, X. Research on the Extraction and Recognition of Complex Flight Actions of Military Aircraft. Aviat. Weapons 2023, 30, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Yang, P.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, R.; Liu, Z. A taxi detour trajectory detection model based on iBAT and DTW algorithm. Electron. Res. Arch. 2022, 30, 4507–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Liu, Y.; Tao, H. A similarity metric algorithm for multivariate time series based on information entropy and DTW. Zhongshan Daxue Xuebao/Acta Sci. Natralium Univ. Sunyatseni 2019, 58, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.-F.; Gao, H. Learning a Mahalanobis Distance-Based Dynamic Time Warping Measure for Multivariate Time Series Classification. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 46, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, M. A hybrid machine learning-based model for predicting flight delay through aviation big data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Huang, H.; Song, W. Competency-based assessment of pilots’ manual flight performance during instrument flight training. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2023, 25, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chang, W.; Cheng, Y. The landing safety prediction model by integrating pattern recognition and Markov chain with flight data. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31 (Suppl. S1), 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, H.; Pan, T.; Liu, H.; Si, H. Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation of Pilot Cadets’ Flight Performance Based on G1 Method. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, P.A.; Pashilkar, A.A. Pilot performance evaluation of simulated flight approach and landing maneuvers using quantitative assessment tools. Sadhana 2017, 42, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Statistical Summary of Commercial jet Airplane Accidents: 2015–2024; Boeing: Seattle, WA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.boeing.com/content/dam/boeing/boeingdotcom/company/about_bca/pdf/statsum.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Accident Incident Data Reporting (ADREP) Taxonomy, 2020 Edition; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://www.icao.int/safety/AIG/taxonomy (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Guo, C.; Sun, Y.; Xu, T.; Hu, Y.; Yu, R. An Improved Transformer Method for Prediction of Aircraft Hard Landing Based on QAR Data. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2025, 26, 2043–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, B.; Vargo, E.P.; Tang, H. On the Exploration of Temporal Fusion Transformers for Anomaly Detection with Multivariate Aviation Time-Series Data. Aerospace 2024, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017), La Jolla, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; 2017; pp. 5999–6009. [Google Scholar]

- El Amouri, H.; Lampert, T.; Gançarski, P.; Mallet, C. Constrained DTW preserving shapelets for explainable time-series clustering. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 143, 109804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ding, T.; Liu, Y. An N400 identification method based on the combination of Soft-DTW and transformer. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1120566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, K.P.; Yang, M.-S. Unsupervised K-Means Clustering Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 80716–80727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NO. | IAS (kt) | AltMSL (ft) | VSpd (fpm) | Pitch (°) | TRK (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67.58 | 1070.9 | −252.6 | 6.43 | 21.8 |

| 2 | 86.31 | 1044.5 | −341.5 | 4.05 | 22.4 |

| 3 | 54.73 | 1135.6 | −433.2 | −3.42 | 20.7 |

| 4 | 63.29 | 998.2 | −298.4 | 2.86 | 21.3 |

| 5 | 74.35 | 974.7 | −114.8 | 5.18 | 22.9 |

| IAS (kt) | AltMSL (ft) | VSpd (fpm) | Pitch (°) | TRK (°) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 75.13 | 998.21 | −372.14 | −2.86 | 22.16 |

| Minimum | 57.31 | 937.21 | −492.35 | −6.17 | 22.01 |

| Maximum | 84.47 | 1096.98 | −230.37 | 6.38 | 22.37 |

| Standard Deviation | 18.51 | 92.97 | 141.36 | 8.93 | 0.67 |

| IAS (kt) | AltMSL (ft) | VSpd (fpm) | Pitch (°) | TRK (°) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 77.42 | 1003.52 | −374.35 | −2.79 | 22.19 |

| Minimum | 55.25 | 934.73 | −497.72 | −6.33 | 21.94 |

| Maximum | 86.62 | 1094.33 | −236.18 | 6.44 | 22.41 |

| Standard Deviation | 21.26 | 98.46 | 149.89 | 9.62 | 0.85 |

| Trainee ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | …… | 198 | 199 | 200 |

| Similarity Metric Value | 4.95 | 6.36 | 3.38 | …… | 5.54 | 5.81 | 5.21 |

| Trainee ID | Similarity Measure Value | Evaluation Level | Weak Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.52 | Improvement Needed | VSpd |

| 2 | 5.64 | Improvement Needed | AltMSL |

| 3 | 4.13 | Good | AltMSL |

| 4 | 5.09 | Qualified | IAS |

| 5 | 4.28 | Good | TRK |

| 6 | 5.85 | Improvement Needed | Pitch |

| 7 | 6.13 | Improvement Needed | IAS |

| 8 | 4.87 | Qualified | IAS |

| 9 | 4.65 | Qualified | AltMSL |

| 10 | 3.92 | Good | VSpd |

| Instructor Rating | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Average Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clustering Result | |||||||

| Excellent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 29 | 4.64 | |

| Good | 0 | 0 | 10 | 37 | 4 | 3.88 | |

| Qualified | 0 | 0 | 35 | 12 | 0 | 3.26 | |

| Improvement Needed | 0 | 0 | 24 | 33 | 0 | 3.58 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, X.; Xu, G.; Yang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chen, B. Evaluation of Flight Training Quality for the Landing Flare Phase Using SD Card Data. Aerospace 2025, 12, 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111012

Du X, Xu G, Yang Q, Xu Y, Chen B. Evaluation of Flight Training Quality for the Landing Flare Phase Using SD Card Data. Aerospace. 2025; 12(11):1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111012

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Xing, Gang Xu, Qingkui Yang, Yihe Xu, and Bin Chen. 2025. "Evaluation of Flight Training Quality for the Landing Flare Phase Using SD Card Data" Aerospace 12, no. 11: 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111012

APA StyleDu, X., Xu, G., Yang, Q., Xu, Y., & Chen, B. (2025). Evaluation of Flight Training Quality for the Landing Flare Phase Using SD Card Data. Aerospace, 12(11), 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111012