1. Introduction

The return to the Moon under NASA’s Artemis program and other international initiatives marks the beginning of a new era in space exploration—one focused on sustained lunar presence rather than short-duration flag-and-footprint missions. Plans for extended lunar habitation, in-situ resource utilization (ISRU), and surface-based research operations require that astronauts live and work for weeks to months inside pressurized habitats on the Moon.

However, one of the most persistent and unsolved threats from the Apollo era remains: lunar dust. Known technically as regolith, this material is unlike anything on Earth. It is composed of sharp, jagged, and highly adhesive particles that cling to suits, tools, and surfaces. Once inside a habitat, it becomes nearly impossible to eliminate. Astronauts who flew on Apollo missions consistently reported how the dust permeated every surface, resisted removal, and caused irritation.

Gene Cernan, commander of Apollo 17, described the challenge clearly: “

I was covered with it. You couldn’t avoid it. It was in my eyes, in my nose, and in my mouth. It was like fine sandpaper, and it was a real problem… You had to be careful not to inhale it.” [

1], as shown in

Figure 1.

Harrison Schmitt, the only geologist to walk on the Moon, referred to the experience as “lunar hay fever,” citing sneezing, sore throat, and eye irritation [

2].

Despite modern improvements—such as airlocks, suit brushing systems, and HEPA filtration—lunar dust is still expected to infiltrate future habitats by clinging to EVA suits, tools, and equipment surfaces. Once inside, this dust can be dislodged from clothing, gear, and other surfaces through normal movement and airflow, leading to re-aerosolization. The Moon’s low gravity makes it easier for fine particles to become and remain airborne once disturbed, and the absence of weathering ensures that the dust remains sharp, mobile, and highly adhesive—partly due to its iron content and magnetic properties [

3].

The health risks posed by lunar dust are not merely theoretical. The most critical threat is inhalation, as illustrated conceptually in

Figure 2. While NASA and other space agencies have prioritized mitigation strategies such as dust-resistant coatings, electrodynamic shields, and advanced airlock systems, these efforts primarily focus on protecting equipment or reducing dust entry into habitats. In contrast, far less attention has been devoted to protecting astronauts once dust is already inside the habitat. This lack of targeted, point-of-inhalation protection represents a significant operational and biomedical gap that must be addressed before long-duration missions can be safely conducted.

This paper proposes a novel respiratory personal protective device specifically designed to mitigate inhalation of lunar dust within habitats.

2. Lunar Dust Characteristics and Environmental Behavior

Lunar dust, or regolith, presents a unique and persistent hazard that is fundamentally different from terrestrial dust. Unlike Earth-based particles, which are rounded over time by wind and water erosion, lunar dust has been formed and fractured by micrometeorite impacts in an airless environment. As a result, the particles retain sharp edges and highly irregular shapes, with spiculated and fractured geometries that persist over geologic timescales.

Lunar regolith is composed of fine, silica-rich grains, many of which are smaller than 50 μm, with a significant portion below 10 μm in diameter [

4,

5]. These respirable-sized particles are the most concerning from a health perspective, as they are capable of bypassing upper respiratory defenses and depositing themselves into the lower lungs [

4].

Figure 3 provides a conceptual illustration of lunar dust particle sizes compared against the cutoffs of common filtration systems. This schematic is anchored in published analyses showing that 50% or more of regolith particles are <10 µm [

5] and that submicron particles are abundant [

4]. These small fractions are precisely those most likely to bypass N95 and HEPA/PAPR filtration, underscoring the inadequacy of Earth-based respiratory protection for lunar environments.

A major complicating factor in lunar dust behavior is its electrostatic charge. On the lunar surface, particle charging is driven primarily by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation and the solar wind. During daytime at the lunar equator and other sunlit regions, UV radiation induces photoemission, which causes dust particles and surface materials to become positively charged. At night, or in regions shielded from the Sun, photoemission ceases, and solar wind electrons dominate, resulting in the accumulation of negative charge. This effect is especially pronounced in permanently shadowed regions such as polar craters, where solar wind electrons can accumulate without interruption, producing sustained negative surface charging. Additionally, triboelectric charging from friction—caused by astronaut movement, tool contact, or mechanical operations—may further alter dust charge inside habitats, particularly after regolith has been tracked indoors.

Once dust particles enter a habitat, they are no longer exposed to these environmental charging mechanisms. Over time, charges may dissipate or shift due to contact with internal surfaces, airflow, or environmental conditions such as humidity. As a result, it is hypothesized that dust within the habitat may exist as a mixed-charge population, including positively charged, negatively charged, and neutral particles. Although this internal charge distribution has not been directly measured, it presents a credible operational concern that complicates the design of mitigation systems, as no single electrostatic method can effectively repel all charge states.

In addition to its shape and charge, lunar dust contains significant iron content. Internally, typical lunar regolith includes approximately 5–15% total iron, primarily as iron oxide (FeO) [

5]. Externally, nanophase iron (Fe

0) is formed through micrometeorite impacts at the particle surface. The combination of embedded and surface iron gives lunar dust both magnetic properties and enhanced adhesion, especially when interacting with electrostatic or magnetic fields, as shown in

Figure 3. The motion and adhesion behavior of lunar dust particles is influenced by a range of physical forces, each arising from specific particle characteristics such as shape, charge, surface energy, and magnetic content. These include both dominant and secondary forces that contribute to dust mobility and surface interaction under lunar conditions, as summarized in

Table 1.

Understanding these unique environmental and material properties is essential to designing effective mitigation strategies. Any system intended to protect astronaut health must account for particle size, charge state, iron content, and aerodynamic persistence under low-gravity conditions. The combination of sharp geometry, variable electrostatic behavior, and magnetic adhesion makes lunar dust far more difficult to manage than Earth-based particulates.

3. Historical Evidence from Apollo Missions

The Apollo missions provided the first and only direct human experience with lunar dust. Despite the short duration of these missions—typically less than three days on the surface—dust quickly emerged as one of the most problematic environmental hazards. During Apollo 17, the longest surface mission, astronauts conducted three extravehicular activities (EVAs) totaling 22 h. In that time, dust infiltrated nearly every system [

1]. This is illustrated in

Figure 4.

The abrasive nature of lunar dust caused damage to hardware that was never intended to tolerate such conditions. Vacuum seals on sample containers failed, three layers of protective material on astronaut boots were worn through, and shoulder joints on EVA suits became stiff and difficult to maneuver due to accumulated grit. Virtually every surface exposed during an EVA became contaminated, and dust adhered tenaciously despite efforts to brush it off before reentry into the Lunar Module as seen in the left panel of

Figure 5. Notably, the Apollo Lunar Module did not include a true airlock. Astronauts entered directly into the main cabin through a single hatch, bringing dust in with them as observed in the right panel of

Figure 5. Once the hatch was sealed, the cabin was re-pressurized using the same internal atmosphere—which now included all the dust brought in on suits and gear.

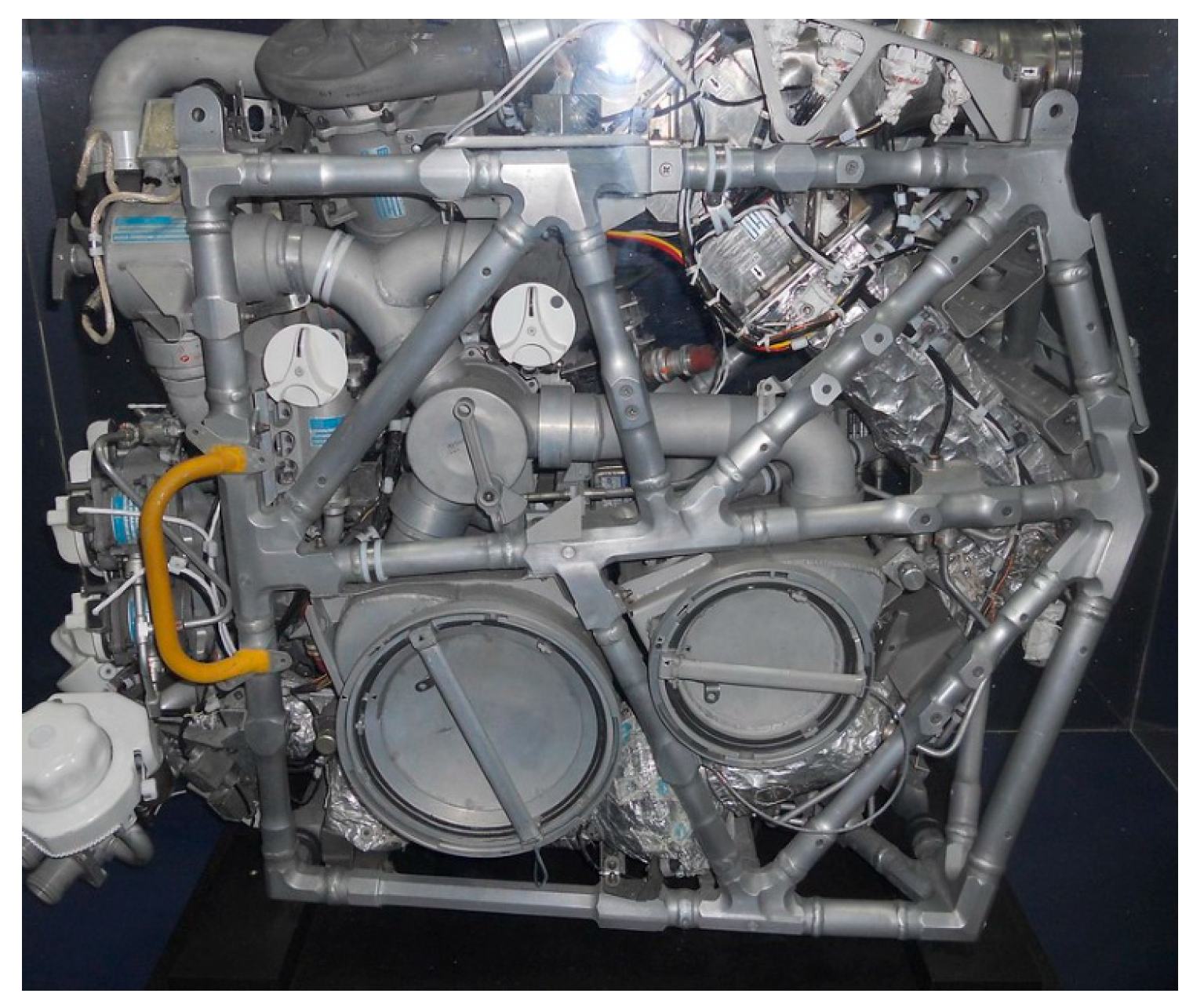

Inside the spacecraft, filtration systems struggled to contain the contamination. The Apollo Environmental Control System used basic filtration as shown in

Figure 6, but it was not designed for submicron dust particles. Highly abrasive and electrostatically charged grains bypassed filters and re-aerosolized, creating persistent airborne exposure. Brushing suits and wiping surfaces with cloths proved ineffective; dust simply moved around the cabin or became airborne again. Some astronauts even resorted to leaving their helmets on inside the spacecraft to avoid direct exposure.

Despite limited medical reporting protocols at the time, several astronauts described respiratory irritation. Harrison Schmitt experienced sneezing and watery eyes and referred to the symptoms as “lunar hay fever.” Pete Conrad of Apollo 12 noted that the crew opted to keep their helmets on due to visible dust in the cabin air as seen in

Figure 7. Post-mission analysis revealed that even flight surgeons who entered the command modules after splashdown reported allergic-type reactions.

These incidents underscore a critical point: while future Artemis missions may incorporate more advanced air handling and filtration systems, they will also involve dramatically longer durations, higher EVA frequency, and significantly more equipment interaction inside habitats. Apollo 17 astronauts were exposed to lunar dust for only about 22 h over three days, whereas Artemis crews—or future industrial miners—may live and work on the surface for up to six months, representing a 60-fold increase in exposure time. In addition, future crews are expected to bring rovers and other heavy equipment into pressurized environments for maintenance, introducing concealed dust burdens not present during Apollo. Apollo’s legacy clearly demonstrates that lunar dust is more than a nuisance—it is a systemic threat to both equipment and astronaut health. Given this dramatic increase in exposure risk, the need for targeted, personal-level mitigation inside future habitats is not just justified—it is urgent.

4. Biomedical Effects and Toxicology

While lunar dust was recognized as a respiratory irritant during the Apollo missions, the biomedical effects of exposure were never systematically studied in human subjects. For decades after Apollo, lunar dust toxicology remained a largely underexplored field. In recent years, a small number of studies using lunar regolith simulants have attempted to quantify the biological impact of inhalation-level exposure [

6,

7].

One of the key findings from these simulation studies is the size-dependent behavior of inhaled particles. Research has shown that particles smaller than 10 μm can penetrate deeply into the alveolar regions of the lungs, while particles smaller than 0.1 μm may translocate into the bloodstream and travel to secondary organs, including the brain. A 2024 study by Cui et al. used CT-based flow simulation to show that more than 50% of sub-4 µm particles deposited in the upper respiratory tract, while smaller particles migrated deeper into pulmonary airways and beyond [

4].

These ultrafine particles are especially dangerous because they evade capture by HEPA and N95 filters, remain suspended in low gravity, and are easily reintroduced into the habitat with each EVA or equipment transfer. Unlike Earth environments, where ventilation and gravity aid particle removal, lunar habitats lack any natural clearing mechanism—allowing these small particles to persist indefinitely.

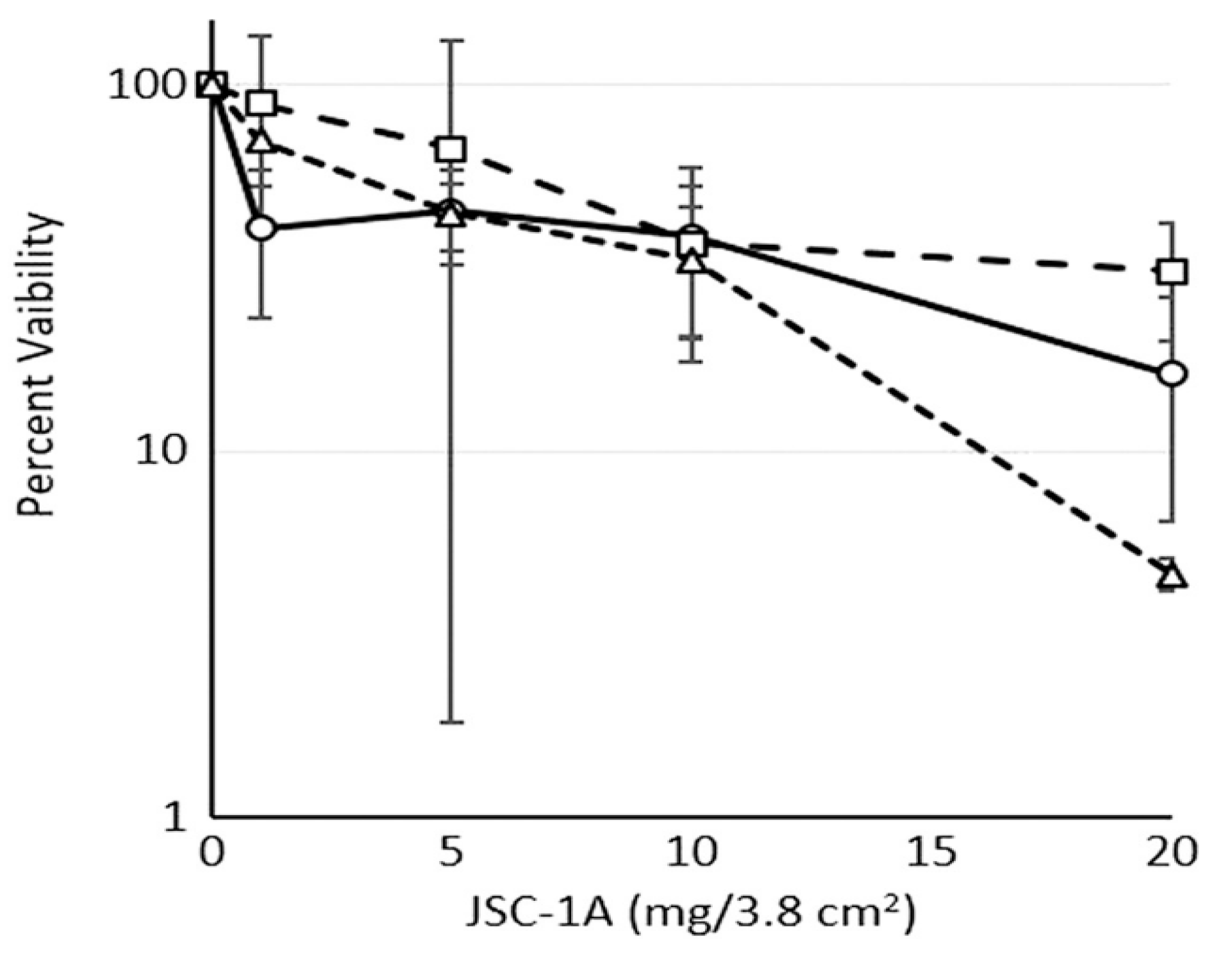

In vitro studies have further demonstrated the biological consequences of this exposure. Caston (2018) [

6] exposed mammalian lung epithelial and neuronal cell cultures to sorted fractions of simulated lunar dust. Particles less than 10 µm in diameter caused marked reductions in cell viability, with <10% survival at concentrations of 20 mg/3.8 cm

2 [

6]. Cellular damage included nuclear fragmentation, mitochondrial disruption, and evidence of oxidative stress and DNA damage [

6] as presented in

Figure 8.

Although the dose used in the Caston study was modest, it caused severe cytotoxicity—highlighting that small, localized burdens of lunar dust can produce dramatic biological effects. In a closed lunar habitat, even minimal daily accumulation of ultrafine particles may lead to chronic exposure levels that exceed these toxic thresholds over time.

In vivo animal studies have also revealed the potential for lunar dust to initiate systemic inflammation. Rask (2009) and Oberdörster (2004) reported that ultrafine particles can bypass the alveolar–capillary barrier and enter the bloodstream or alternatively translocate directly into the central nervous system via the olfactory nerve pathway, with deposition observed in the olfactory bulb [

7,

8].

While no formal human inhalation studies have been conducted using true lunar dust, the consistency of findings across simulation platforms, cell cultures, and animal models suggests a credible and serious risk to astronaut health. Acute risks may include respiratory distress and airway inflammation, while chronic exposure may contribute to pulmonary fibrosis, emphysema, carcinogenic processes, and neurological impairment.

Given the extreme difficulty of replicating the charged, spiculated, and iron-rich properties of lunar dust in Earth-based test platforms, existing studies likely underestimate its true hazard. While airlocks and air handling systems are designed to limit dust entry into habitats, they cannot eliminate it entirely. Once inside, the toxic potential of respirable lunar dust becomes a critical concern. The current body of evidence, though limited, provides a clear warning: without targeted, personal-level respiratory protection, long-duration lunar missions may result in irreversible biological harm.

5. Bounding Estimates of Dust Concentration in Habitats

While no direct dataset exists for particle concentrations inside a pressurized lunar habitat, bounding estimates can be made from Apollo mission observations and toxicology thresholds. Apollo 17 astronauts reported visible airborne dust and respiratory irritation after only ~22 h of EVA exposure across three days [

2]. Post-flight reports noted re-aerosolization of dust whenever suits or equipment were disturbed inside the cabin, even with basic filtration in place.

If future Artemis missions involve six months of habitation with an assumed 3–4 EVAs per week, each EVA could introduce on the order of grams of fine regolith attached to suits, tools, and rover components. Even if 99.9% of this load is removed by airlocks and brushing, a residual of 0.1% would still correspond to milligram-scale ingress per EVA. Over weeks, these trace amounts would accumulate into a persistent airborne background. Unlike Earth environments, lunar gravity allows respirable dust (<10 µm, especially submicron fractions) to remain suspended for long periods, and particles are easily reintroduced into the air by normal crew activity [

5].

Although HEPA filtration is expected in future habitats, these systems are rated at 99.97% efficiency only for particles ≥ 0.3 µm. Their performance decreases sharply for the smallest ultrafine particles (<0.01 µm), which toxicology studies suggest are the most biologically active. These particles can evade filtration, remain airborne indefinitely, and deposit in the deepest regions of the lungs or translocate into the bloodstream.

Laboratory toxicology studies show that localized surface burdens of 10–20 mg/3.8 cm

2 of fine particles can cause severe cytotoxicity in mammalian cells [

6]. When scaled to an enclosed lunar habitat over months of exposure, background levels may approach or exceed these biologically significant thresholds, even without catastrophic dust intrusion. This supports the conclusion that in-habitat, point-of-inhalation protection is necessary to reduce the risk of both acute irritation and chronic harm [

7,

8].

6. Terrestrial Analogs and Dust-Associated Diseases

Because true lunar dust cannot be ethically tested in humans and only limited samples exist on Earth, researchers have turned to terrestrial analogs to study inhalation risks. While it would be unethical to deliberately expose people to harmful dust like crystalline silica or volcanic ash, large-scale unintentional exposures in occupational and environmental settings provide valuable data. The two most widely studied analogs are crystalline silica dust—commonly encountered in mining and construction—and volcanic ash, which has been analyzed extensively following major eruptions. These analogs offer important proxies for understanding chronic respiratory outcomes, particularly in real-world exposure scenarios [

9].

While these materials are not chemically identical to lunar dust, they serve as useful biological references—showing that fine, sharp-edged, and persistent particles can cause serious long-term damage to the respiratory system, even at moderate or intermittent exposure levels.

Crystalline silica is one of the most studied airborne particulate hazards. Long-term inhalation of silica particles has been strongly linked to silicosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, and kidney disease. An estimated 23 million workers globally are exposed to silica dust each year, with 46,000 deaths attributed to silicosis in 2016 alone. Similarly, volcanic ash has been shown to cause acute respiratory symptoms such as coughing, bronchitis, and airway inflammation, with possible long-term effects including fibrosis and chronic bronchitis. These real-world epidemiologic outcomes provide important biological validation of dust-related respiratory disease pathways [

10].

These data help validate the biological plausibility that respirable lunar dust—particularly its ultrafine and spiculated fractions—may induce similar chronic outcomes, despite differences in source material and environment.

However, while these analogs are chemically informative, they diverge from lunar dust into several critical physical and environmental dimensions. As summarized in

Table 2, lunar dust is markedly more hazardous due to its spiculated geometry, persistent airborne behavior, and ability to retain electrostatic charge. Unlike terrestrial dust, which becomes rounded through erosion, lunar dust remains sharp-edged due to the absence of weathering. Lunar particles acquire charge from solar wind and ultraviolet exposure, and this charge can persist or fluctuate in habitat environments. In contrast, Earth-based dust is typically neutral and less adherent.

Lunar dust also contains both internal iron (e.g., FeO) and surface-bound nano-phase iron (Fe

0), which form during micrometeorite impact events. These iron phases enhance the dust’s magnetic and oxidative properties—features do not present in most terrestrial analogs. Furthermore, under the Moon’s 1/6 gravity, dust remains suspended longer and is more prone to re-aerosolization with minimal disturbance, whereas terrestrial dust settles rapidly under stronger gravity [

5].

While terrestrial analogs like silica and volcanic ash provide useful insights into the biological effects of fine particulate exposure, they cannot replicate the physical and environmental extremes of the lunar surface. Lunar dust behaves differently due to its sharp-edged morphology, persistent electrostatic charge, high iron content, and mobility in low gravity. These distinct properties limit the relevance of Earth-based analogs for designing effective mitigation strategies. As a result, future protective solutions must integrate lessons from terrestrial toxicology with the unique environmental challenges of the lunar surface.

7. Limitations of Current Mitigation Strategies

The challenge of mitigating lunar dust has long been acknowledged by NASA and the broader aerospace community. However, despite awareness of its risks since the Apollo era, little meaningful progress was made in the decades that followed. Attention shifted to low-Earth orbit operations, including the International Space Station, and to early Mars concepts, leaving lunar dust as a recognized but largely unaddressed hazard. Most current strategies focus on protecting surface equipment and suits from contamination and on minimizing dust entry into habitats through improved airlocks and air handling systems. These efforts are built on two incomplete assumptions: that dust can be completely excluded from the habitat, and that any dust that does enter poses minimal health risk. In reality, dust infiltration is inevitable, and its toxicological impact—particularly through inhalation—remains poorly mitigated. The absence of targeted, in-habitat respiratory protection represents a critical gap in current mission planning.

Modern lunar habitat concepts incorporate mitigation systems such as airlocks, HEPA filtration, and environmental control protocols to limit dust ingress. NASA’s Artemis program has advanced this approach through designs including multi-stage airlocks, suitlocks, and hybrid suitport-airlock architectures. These systems aim to reduce contamination by using improved seals, dust-resistant surfaces, and electrostatic or mechanical cleaning technologies applied at the ingress interface. HEPA filters are also planned for use within the Artemis Environmental Control and Life Support Systems (ECLSS) to remove airborne particles, although their efficiency declines below 0.01 µm. Despite these advancements, none of these systems can fully eliminate dust, particularly particles that are electrostatically adhered to, embedded in suits, tools, equipment, or research samples. Even under optimal conditions, respirable particles can evade removal, become dislodged during ingress, and persist in the habitat atmosphere [

11,

12].

The 2021 NASA Lunar Dust Challenge was a competitive effort to spur innovation in this domain [

13]. NASA awarded funding to seven university teams that proposed a range of external mitigation solutions, including:

Electrostatic fiber-based coatings for suits

Modular electrodynamic shields for habitat surfaces

Cryogenic liquid droplet systems for dust removal

Brushes and ultrasonic vibration systems for suit and panel cleaning

Bio-inspired coatings to reduce dust adhesion

While these projects contributed valuable insights into surface-level and wearable dust mitigation (see

Figure 9), none addressed the challenge of airborne dust exposure inside habitats at the point of inhalation. The 2021 Lunar Dust Challenge was also conducted too late to influence the design or deployment of early Artemis hardware. The first Artemis lunar missions are already committed to configurations that include airlocks and HEPA filtration but lack any personal, in-habitat respiratory protection. As a result, astronauts may still face prolonged exposure to respirable dust despite systemic containment efforts.

The Apollo Program, more than 50 years ago, revealed how easily dust could infiltrate pressurized spaces, contaminate surfaces, and provoke respiratory symptoms (

Figure 1 and

Figure 7). Yet current Artemis-era planning largely continues the same assumptions: that airlocks and filtration will be sufficient. Despite growing evidence of lunar dust toxicity and known limitations of air handling systems, no personal-level respiratory protection has been proposed or prototyped for in-habitat use.

With dust infiltration inevitable and airborne exposure likely, long-duration missions require targeted protection at the point of inhalation. Addressing this operational gap demands wearable systems specifically engineered for the lunar environment.

8. Inadequacy of Earth-Based Respiratory Protection

Earth-based respiratory protection systems have played a central role in industrial safety, healthcare, and hazardous materials response. However, these systems were never designed for the unique physical, environmental, and operational constraints of lunar habitation. The three most common forms of Earth-based personal protective equipment (PPE)—cloth masks, N95 respirators, and powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs)—each have substantial limitations that render them ineffective or impractical for use in lunar habitats.

Cloth or fabric masks provide negligible protection against airborne particulates and are entirely unsuitable for lunar dust. They lack a face seal, allow air bypass, and are ineffective for particles smaller than 3–10 µm—well above the size range of most lunar dust. Such masks would be considered unsafe for any meaningful use in a lunar environment.

N95 respirators, while far more capable, also fall short. They are rated to filter 95% of particles ≥0.3 µm, but lunar dust includes a significant fraction of particles below this range. Even under ideal conditions, submicron particles may penetrate N95 filters or enter via face seal leakage [

14]. More importantly, N95s are designed for short-duration, task-specific use—not continuous wear in a living environment. They are difficult to tolerate for extended periods, restrict facial communication, prevent eating and drinking, and can cause discomfort, skin irritation, and headaches during prolonged use. In a confined lunar habitat, where astronauts must breathe freely and interact fluidly over hours or days, N95s are functionally unworkable.

Powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) provide better filtration and face seal performance than N95s, using HEPA filters and positive-pressure airflow. HEPA filters remove 99.97% of particles ≥0.3 µm, but efficiency declines for particles smaller than 0.01 µm—a size range that includes a significant portion of lunar dust. These ultrafine particles can diffuse through filter media and bypass filtration mechanisms. Over time, filter performance degrades as sharp lunar dust clogs the system. PAPRs include full hoods and are widely used in industrial and hospital settings, but they are bulky, battery-powered, and can be hot, noisy, and isolating (see

Figure 10). While effective on Earth, they are impractical for long-duration lunar use where comfort, communication, and access to food and water are critical. Routine maintenance and battery demand further limit their suitability for space [

14].

These limitations—across cloth masks, N95s, and PAPRs—highlight a fundamental challenge: Earth-based respiratory systems are not designed for the unique hazards of lunar dust. No existing option offers continuous, comfortable protection against ultrafine, abrasive particles while allowing astronauts to eat, sleep, communicate, and function normally inside a habitat. This gap underscores the need for a purpose-built, wearable system designed specifically for in-habitat use on the Moon.

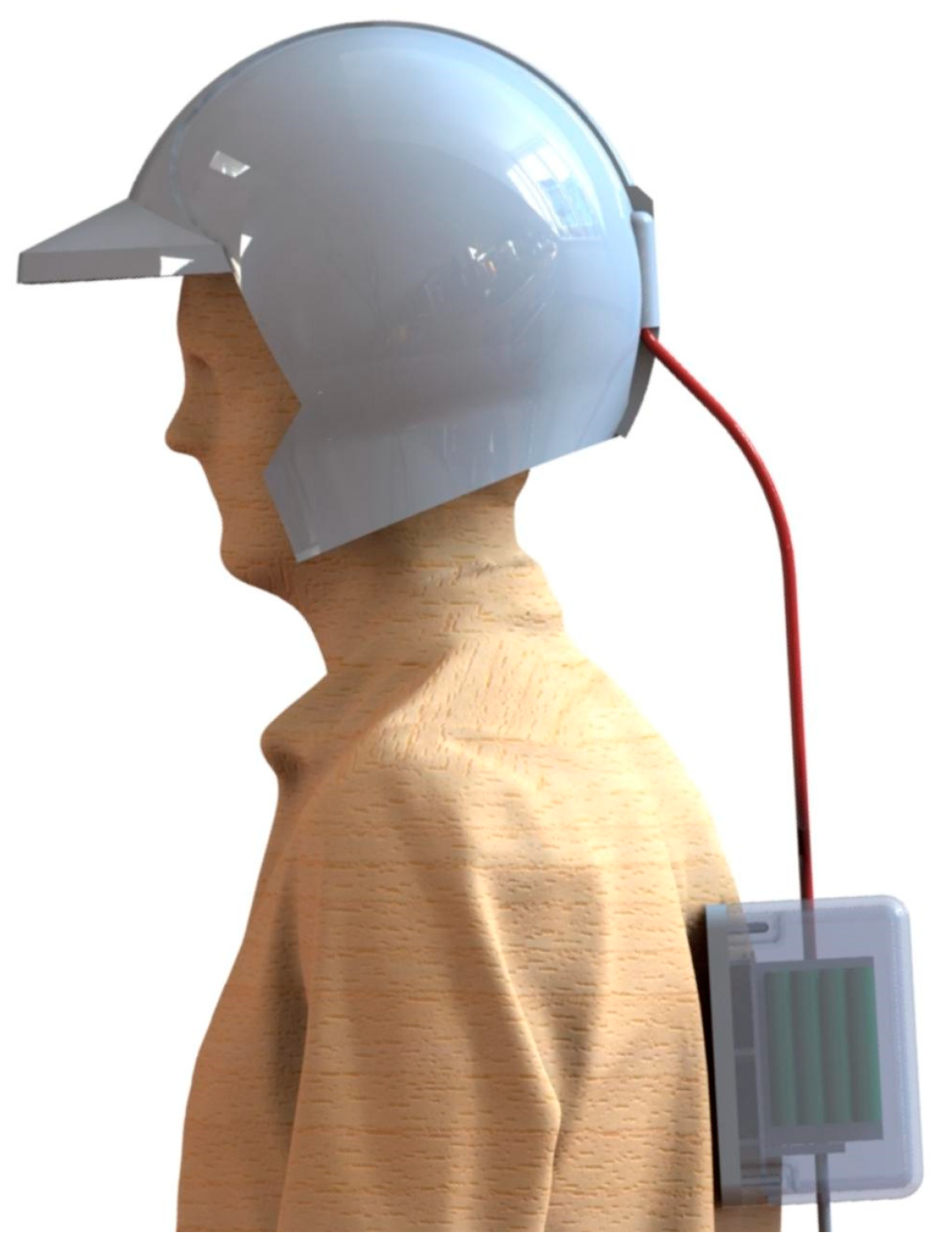

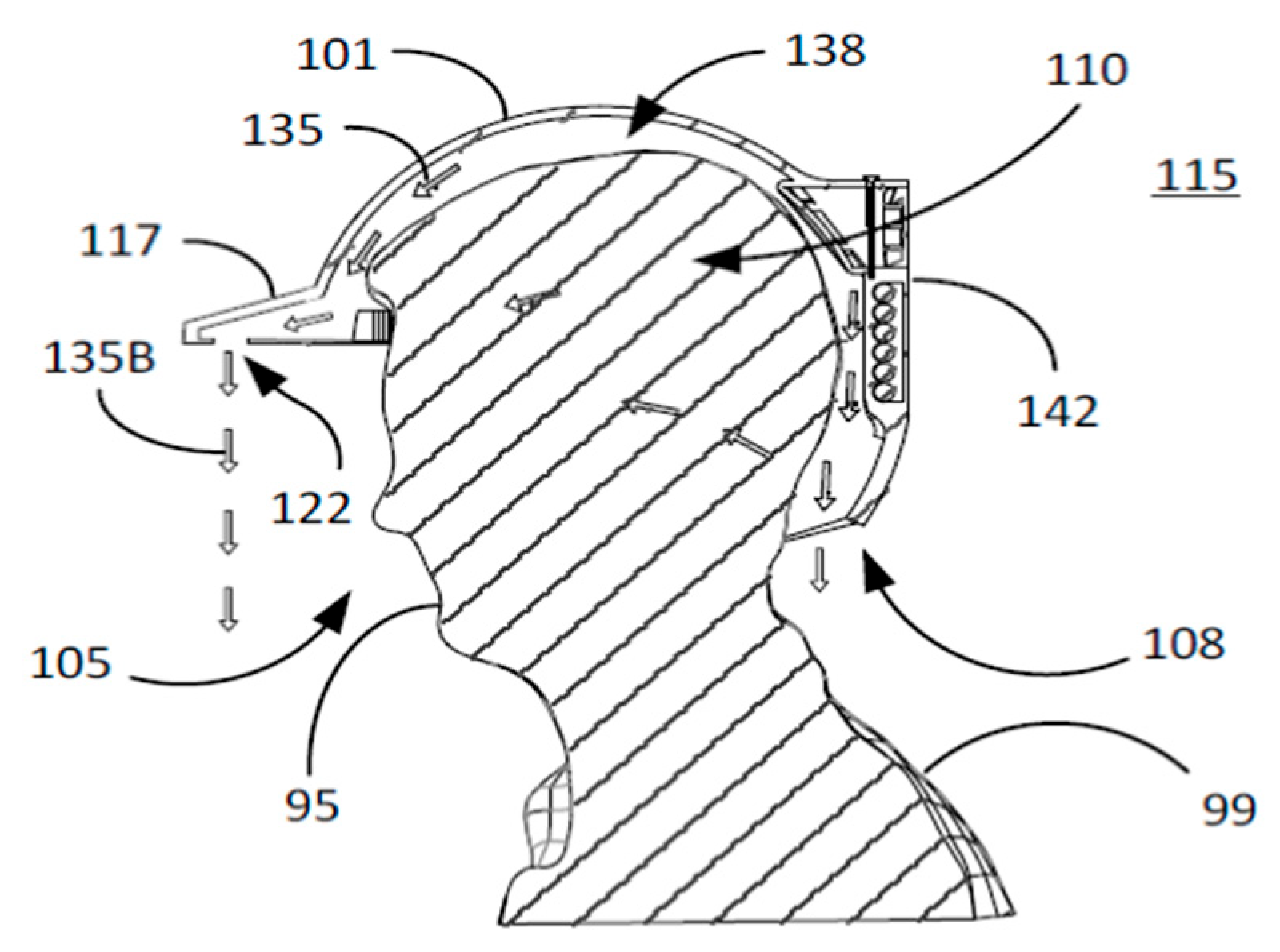

9. Lunar Baseball Hat—System Design and Mechanism

To address the persistent and hazardous risk of inhaling lunar dust—an issue expected to remain despite airlocks and filtration in future lunar habitats—our team developed a novel personal protective system: the Lunar Baseball Hat (see

Figure 11) [

15,

16]. This wearable device allows astronauts to eat, speak, rest, and interact while minimizing exposure to airborne particles. Unlike traditional respiratory equipment that relies on facial sealing or full enclosures, the system employs a multi-layered approach to protect the user’s breathing zone.

The patented device compromises a structured but wearable headpiece featuring an open face vent, integrated fan, HEPA filtration, ionization, and electrostatic dust repulsion. The external structure and form factor are shown in

Figure 12. The system is designed for minimal intrusion, offering high functionality without requiring a sealed helmet or facial covering.

The protective function of the device relies on two integrated mechanisms that work in concert: (1) a mechanical system that filters, charges, and redirects clean air away from the face, and (2) an electrical system that generates an alternating electrostatic field to repel charged particles. The combined effect creates a reinforced protective zone in front of the user’s face, where conditioned airflow and active electrostatic repulsion operate simultaneously to prevent dust intrusion.

For the mechanical system, air from the surrounding habitat is drawn into the device through an integrated fan positioned at the back of the hat. The air first passes through a HEPA filter, which removes 99.97% of particles ≥0.3 µm. It then moves through an ionization stage, where negative ions attach to ultrafine particles that passed through the filter. Already-negative particles remain negatively charged, while neutral particles are converted to negative. Positively charged become negative after passing through the high-density ion field. The result is a stream of filtered air containing primarily negatively charged particles, routed through an internal channel and exiting through vent ports embedded in the brim as illustrated in

Figure 13. This forms a low-velocity air curtain that flows downward and outward across the user’s face, physically displacing dust and delivering a shield of preconditioned air.

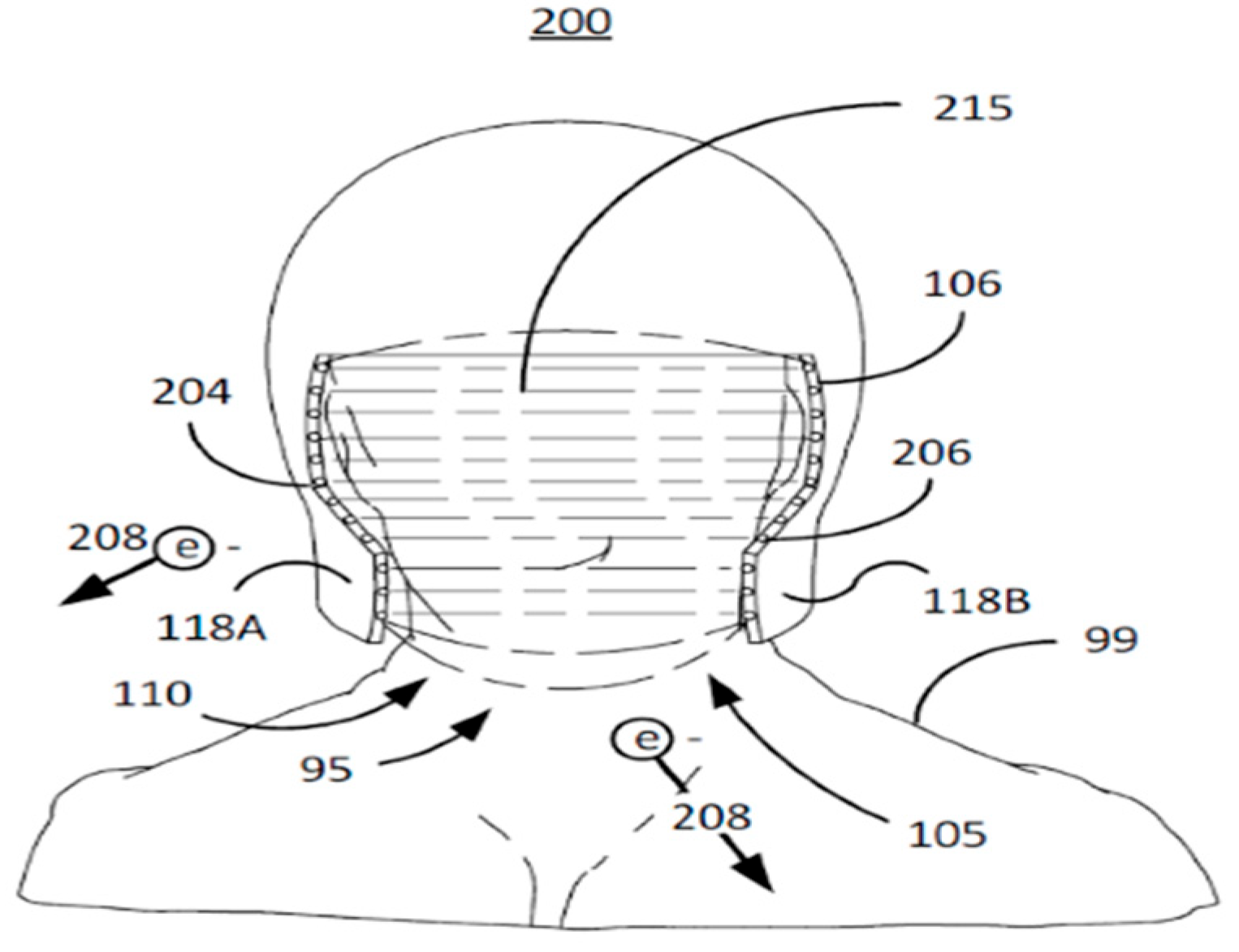

The electrical system compromises a series of electrodes embedded along the perimeter of the face vent (see

Figure 14). These electrodes generate a time-varying electric field using both direct and alternating current to repel charged particles near the user’s face. The field is configured to deflect both negatively and positively charged dust, whether carried in the filtered airflow or suspended in the ambient cabin environment. By alternating polarity, the system continuously repels particles of either charge away from the respiratory zone.

The mechanical and electrical systems are designed to operate in tandem. The airflow forms a barrier of clean, negatively charged air that flows across and outward from the user’s face, displacing airborne particles away from the breathing zone, while the electrostatic field reinforces this barrier by actively repelling charged particles. This continuously operating system mitigates dust exposure without requiring facial sealing or restricting the wearer, enabling astronauts to function normally inside the habitat. At this TRL 2 stage, several design trade-offs have already been considered. Airflow must be sufficient to displace dust but remain quiet and comfortable for long-duration use. Electrode fields must effectively repel both positively and negatively charged particles while staying within safe exposure thresholds for eyes and skin. The device must also remain lightweight and minimally bulky to preserve wearability, communication, and comfort during daily activities inside a lunar habitat.

10. A Preliminary Design Requirements Trade-Offs

Although the Lunar Baseball Hat remains at TRL-2, several preliminary design requirements have been identified together with their associated trade-offs, as shown in

Table 3. These considerations are not final specifications, but they highlight the engineering balances that will need to be optimized as the system advances.

These requirements illustrate how performance goals are inherently coupled. For example, achieving higher airflow rates improves particle clearance but also generates more noise and consumes more power, which in turn increases mass if larger batteries are required. Similarly, reducing system weight favors astronaut comfort but constrains available battery capacity and airflow hardware. At this TRL-2 stage, the precise optimization of these trade-offs remains future work, but the framework demonstrates that the design is being developed within realistic engineering boundaries rather than in isolation.

11. Development Status and Path Forward

The Lunar Baseball Hat system is currently in early development, at Technology Readiness Level 2 (TRL 2). Preliminary schematics and component functions have been defined, and integration of subsystems—including HEPA filtration, ionization, airflow management, and electrostatic repulsion—has been conceptually validated. The system is envisioned for operational use inside lunar habitats, complementing existing dust mitigation strategies such as airlocks and central HEPA filtration. It is designed for continuous wear during normal daily activities—including work, communication, eating, and sleeping—so that astronauts remain protected at all times, even when airborne dust persists within the habitat. While astronauts could remove the system when desired, the device is intended to provide uninterrupted respiratory protection throughout routine living and working inside the habitat. Representative design elements are shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

The next phase will begin with computational simulations and modeling to refine key parameters, including airflow behavior, ionization efficiency, electrostatic field strength, and dust charge-state distributions. These early studies will guide subsequent benchtop evaluations of individual subsystems, such as airflow stability and ionization performance, using lunar dust simulants. Results from these tests will inform iterative improvements and eventually support integration of subsystems for combined performance assessments. As development advances, usability factors such as long-duration wear, comfort, and communication will be evaluated in Earth-based analog environments. At every stage, safety considerations—including electric field thresholds for the face and eyes—will be incorporated. This progression maintains the TRL 2 status of the current work while outlining the pathway toward higher readiness levels in a logical and structured manner.

Early publication of this concept may also help spark broader interest and collaboration, accelerating progress toward a fully developed, wearable dust mitigation system.

12. Earth-Based Applications

While the Lunar Baseball Hat was developed specifically for lunar habitats, it may have future applications in high-dust Earth environments such as underground mining or public exposure during volcanic events. However, it was not designed for terrestrial conditions, which involve higher gravity, predominant neutral particles, and dynamic air movement from wind and convection. Adapting the system for Earth would require further study and likely modifications to airflow, filtration, and charge management. These applications remain speculative and are outside the current development scope.

13. Conclusions

Lunar dust is not comparable to typical Earth-based particulate hazards. It is sharp, biologically active, and electrostatically charged, and includes a high proportion of ultrafine particles capable of penetrating deep into the lungs and crossing into the bloodstream. Even limited inhalation may result in long-term or irreversible damage to the respiratory system, and animal studies suggest the potential for neurological involvement via olfactory or circulatory pathways. This is not a nuisance-level risk, it is a serious biomedical hazard. Despite being known since Apollo, it remains largely unaddressed. Future lunar habitats must assume that some level of airborne dust contamination is inevitable, and in-habitat inhalation must be considered a mission-critical health issue.

The Lunar Baseball Hat represents a new class of in-habitat protective technology. It combines HEPA filtration, ionization, mechanical airflow, and electrostatic repulsion into a wearable system designed to actively prevent the inhalation of lunar dust without requiring a facial seal or enclosure. The system’s open-face design enables continuous use during normal astronaut activities, such as eating, speaking, and sleeping—factors critical for long-duration missions.

While development is still at an early stage, this concept addresses a key operational and biomedical gap in current lunar mission planning. Continued prototyping, validation, and environmental simulation will be necessary to refine performance. If successfully implemented, this system could play a vital role in enabling safe, sustained human habitation on the Moon.

This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled “Defying Lunar Dust: A Revolutionary Helmet Design to Safeguard Astronauts’ Health in Long-Term Lunar Habitats,” which was presented at the AIAA ASCEND Conference, Las Vegas, Nevada, 22–24 July 2025 [

17].