Wood and Wood-Based Materials in Space Applications—A Literature Review of Use Cases, Challenges and Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Application as a structural or construction material;

- Application as a vibration/shock-absorbing material;

- Application as a thermal protection material;

- Application as an ignition material.

2. Application as a Structural or Construction Material

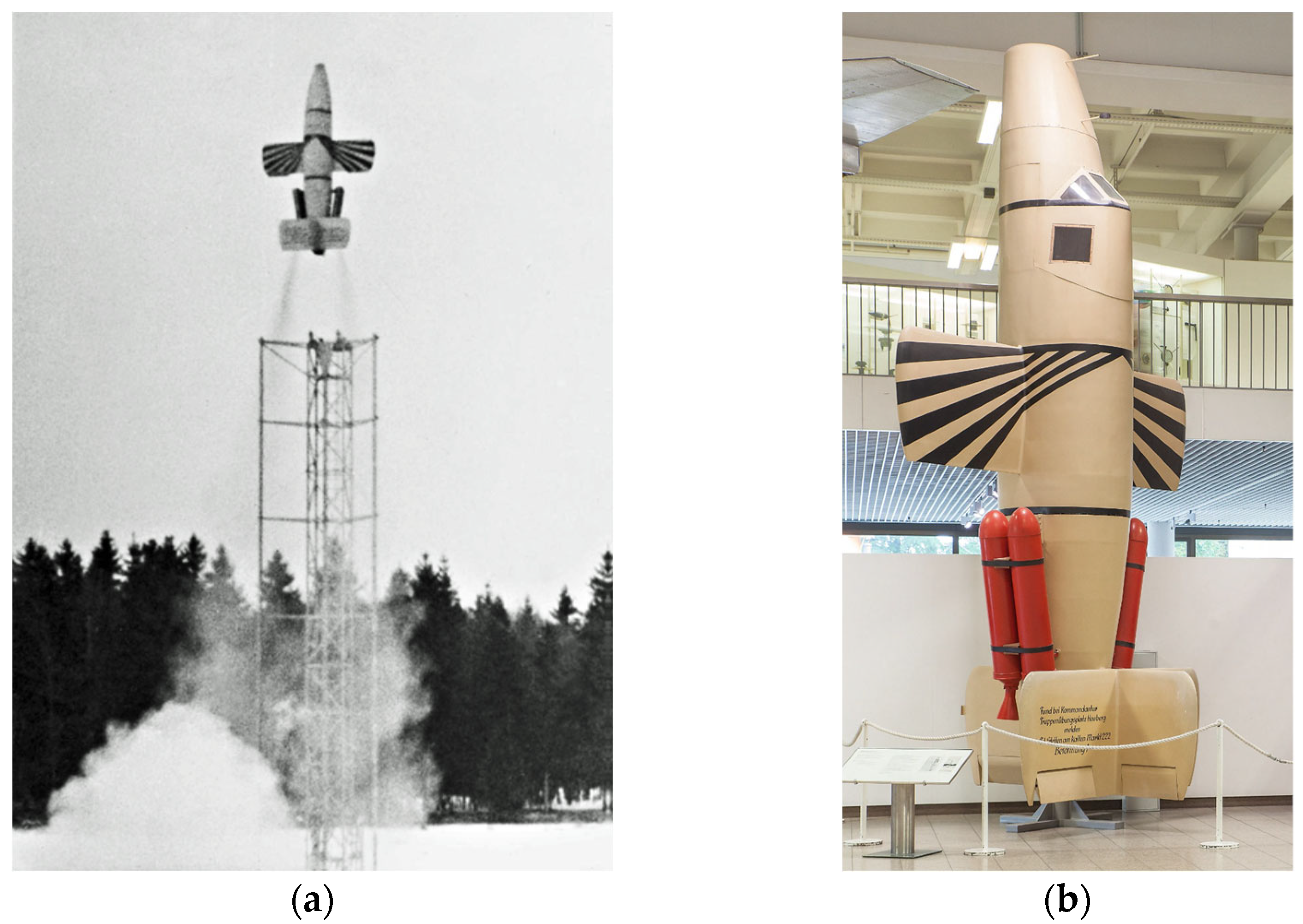

2.1. Plywood for the First Manned Rocket

2.2. Surface-to-Air Missile “Rheintochter”

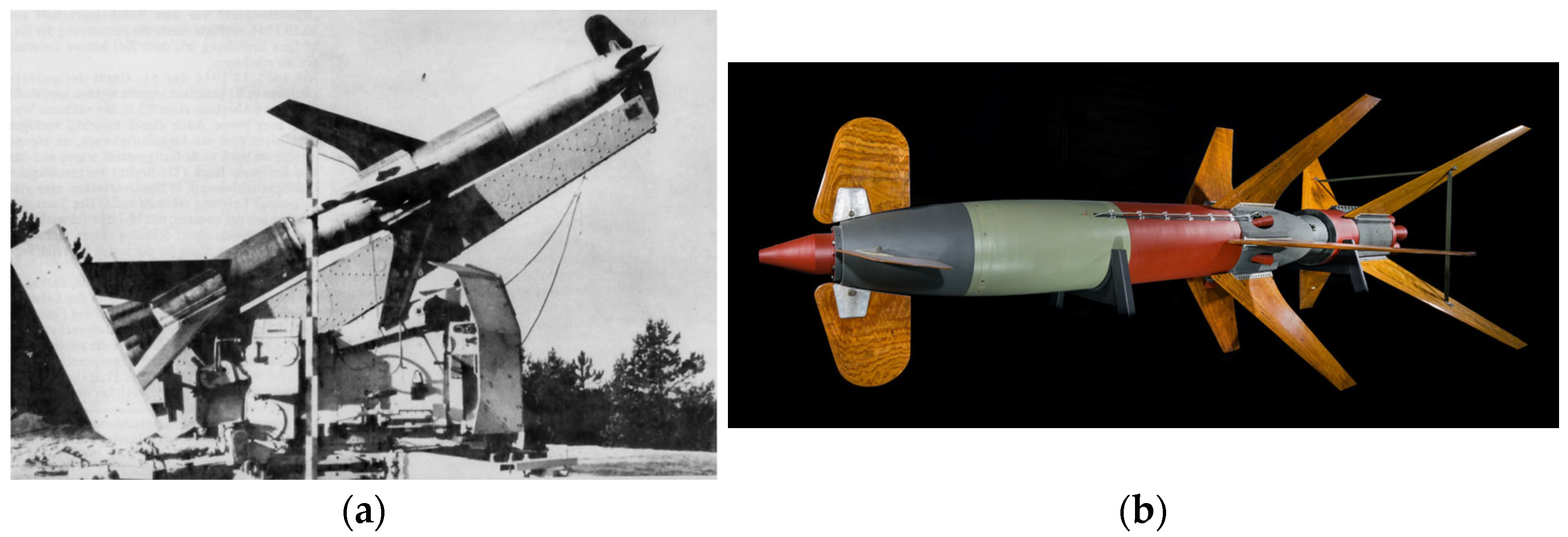

2.3. Rocket-Powered Interceptor “Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1”

2.4. Wooden Nose Cone of a Student Co-Developed Rocket

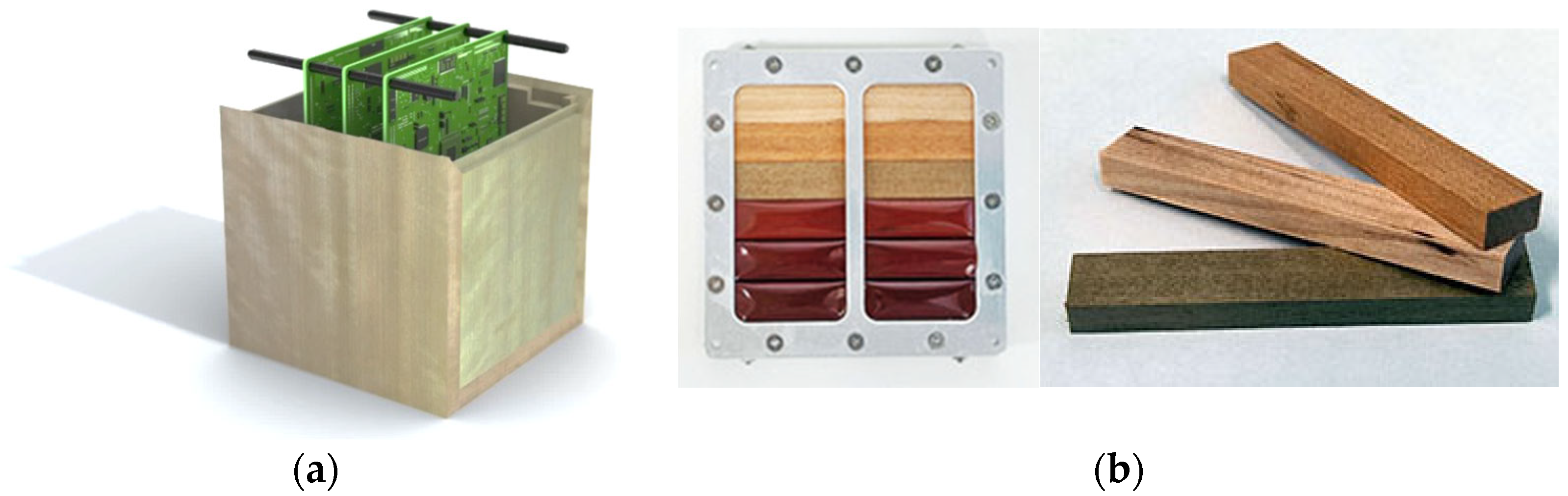

2.5. Wooden Outer Surfaces and Casing on CubeSats

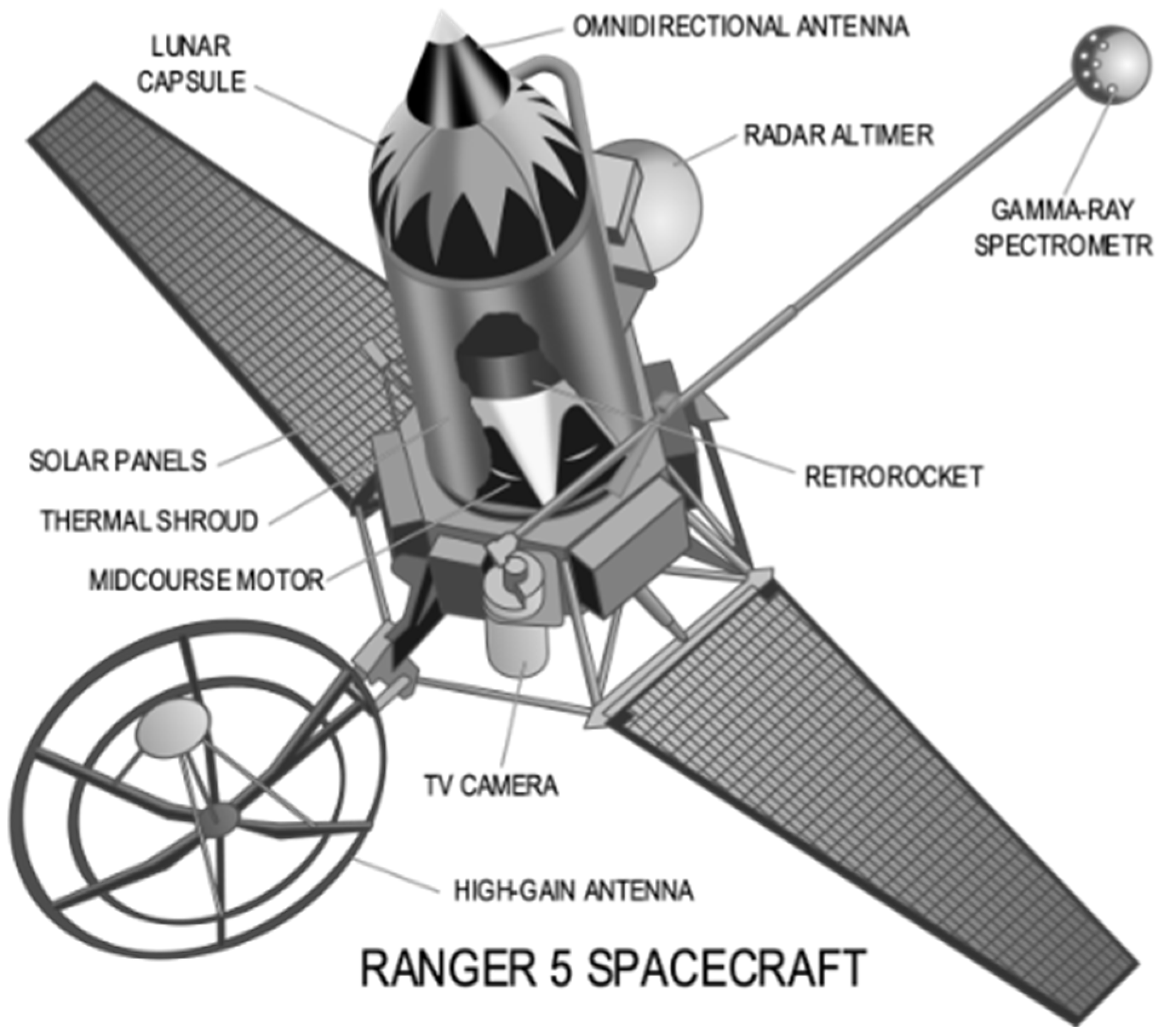

3. Application as a Vibration/Shock-Absorbing Material

4. Application as a Thermal Protection Material

4.1. Thermal Insulation: Balsa Wood Tank Insulation Concept for Saturn V Stages

4.2. Impregnated Oak Nose Cap for FSW (Fanhui Shi Weixing) Satellites

4.3. Wood-Based Material TPSea Developed at TUD

5. Application as Ignition Material

6. Discussion of Research Results

- Lack of uniformity in properties due to natural growth;

- Highly anisotropic mechanical properties;

- Defects in wood (knots, pitch pockets) that reduce strength;

- Hygroscopic properties allow swelling and shrinking;

- Changes in mechanical properties, and the susceptibility of wood to being attacked by insects, fungi or microorganisms.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mouritz, A.P. Introduction to Aerospace Materials; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-85709-515-2. [Google Scholar]

- Smithsonian Institution De Havilland DH-98 B/TT Mk. 35 Mosquito. Available online: https://www.si.edu/object/de-havilland-dh-98-btt-mk-35-mosquito%3Anasm_A19640023000 (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum The Spruce Goose—The Largest Wooden Airplane Ever Built. Available online: https://www.evergreenmuseum.org/exhibit/the-spruce-goose/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Aguilera, A.; Davim, J.P. Research Developments in Wood Engineering and Technology; Hershey: Derry Township, PA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4666-4554-7. [Google Scholar]

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). NASA—The M2-F1: “Look Ma! No Wings!”; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Reed, R.D.; Lister, D.; Yeager, C. (Eds.) Wingless Flight: The Lifting Body Story; University of Kentucky Press: Lexington, KY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-8131-9026-6. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations; World Commission on Environmental and Development. Our Common Future—Brundtland Report; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; p. 383. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. Guidelines for the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-92-1-002185-2. [Google Scholar]

- ESA. The ESA Green Agenda. Available online: https://www.esa.int/About_Us/Climate_and_Sustainability/The_ESA_Green_Agenda (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Hickey, M.; King, C. The Cambridge Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-521-79401-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dunky, M.; Niemz, P. Holzwerkstoffe und Leime; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; Marcelona, Spain; Hong Kong, 2002; ISBN 978-3-642-62754-5. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, O.; Hörschgen-Eggers, M.; Pinaud, G.; Podeur, M. Cork Based Thermal Protection System For Sounding Rocket Applications-Development And Flight Testing. In Proceedings of the 23rd ESA PAC Symposium, Barcelona, Spain, 11–15 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim. Cork Composites Thermal Protection Systems. Available online: https://www.amorimasia.com/uploads/4/8/0/0/48004771/tps_pp_04_07_2008ac.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Silva, J.; Devezas, T.; Silva, A.; Gil, L.; Nunes, C.; Franco, N. Exploring the Use of Cork Based Composites for Aerospace Applications. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 636, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasburger, E.; Sitte, P. Strasburger—Lehrbuch der Botanik für Hochschulen; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; ISBN 978-3-8274-1010-8. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, A.P.; Bordado, J.C. Cork—A renewable raw material: Forecast of industrial potential and development priorities. Front. Mater. 2015, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Easterling, K.E.; Ashby, M.F. The structure and mechanics of cork. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Math. Phys. Sci. 1997, 377, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArianeGroup Raumfahrt für eine Nachhaltigere Erde. Unser Engagement für Nachhaltigkeit; ArianeGroup Raumfahrt für eine Nachhaltigere Erde: Paris, France, 2021; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Caporicci, M. The Future of European Launchers: The ESA Perspective. Technology 2000, 104, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Castanié, B.; Peignon, A.; Marc, C.; Eyma, F.; Cantarel, A.; Serra, J.; Curti, R.; Hadiji, H.; Denaud, L.; Girardon, S.; et al. Wood and plywood as eco-materials for sustainable mobility: A review. Compos. Struct. 2024, 329, 117790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empey, D.; Gorbunov, S.; Skokova, K.; Agrawal, P.; Swanson, G.; Prabhu, D.; Mangimi, N.; Peterson, K.; Winter, M.; Venkatapathy, E. Small Probe Reentry Investigation for TPS Engineering (SPRITE). In Proceedings of the 50th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, Nashville, TN, USA, 9–12 January 2012; Aerospace Sciences Meetings. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, K. Bachem BP 20/Ba 349 Natter: Die bemannte Rakete aus Holz. Available online: https://www.flugrevue.de/klassiker/bachem-bp-20-ba-349-natter-die-bemannte-rakete-aus-holz/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Deutsches Museum; Mosch, K. Raketenflugzeug Bachem Ba 349 “Natter”. Available online: https://digital.deutsches-museum.de/de/digital-catalogue/collection-object/77672/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Wehrmann, J. Bachem Ba 349 Natter. Available online: https://luftfahrtmuseum-hannover.de/images/wehrmann/Bachem%20Ba%20349%20Natter.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- DPMA (Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt) “Natter”—Die erste bemannte Rakete. Available online: https://www.dpma.de/dpma/veroeffentlichungen/meilensteine/flugpioniere/natter/index.html (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Sharp, D. Unbemannter Start eines Bachem Ba 349-Prototyps, 1944; Spitfires over Berlin: The Air War in Europe 1945; Mortons Media Group Ltd.: Horncastle, UK, 2015; The Fatal mistake of Lothar Sieber; ISBN 978-1-909128-69-9. [Google Scholar]

- Putt, D.L. German Developments in the Field of Guided Missiles. SAE Trans. 1946, 54, 404–411. [Google Scholar]

- Avino, M. Rheintochter R I Missile. Available online: https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-media/NASM-NASM2022-02463 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Smithsonian Institution Rheintochter R I Missile. Available online: https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/missile-surface-air-rheinmetall-borsig-rheintochter-r-i/nasm_A19710756000 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Christopher, J. The Race for Hitler’s X-Planes—Britain’s 1945 Mission to Capture Secret Luftwaffe Technology; History Press: Charleston, SC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-80399-564-9. [Google Scholar]

- Griehl, M. Deutsche Flakraketen bis 1945; Waffen-Arsenal—Waffen und Fahrzeuge der Heere und Luftstreitkräfte; Podzun-Pallas-Verlag: Wölfersheim-Berstadt, Germany, 2002; Volume S-67, ISBN 3-7909-0768-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chertok, B.E. Rockets and People. In NASA History Office; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.N. Soviet Fighters of the Second World War; Fonthill Media: Stroud, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-78155-825-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, G.P. History of Liquid-Propellant Rocket Engines in Russia, Formerly the Soviet Union. J. Propuls. Power 2003, 19, 1008–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslov, M. Raketenkämpfer “Bi”. Available online: https://de.topwar.ru/26554-raketnyy-istrebitel-bi.html (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Bach, C.; Sieder, J.; Weig, F.; Tajmar, M. Design-boundaries-of-a-liquid-fuelled-propulsion-system-for-a-500-N-sounding-rocket.pdf. In Proceedings of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF), Guadalajara, Mexico, 26–30 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grasselt-Gille, S. Mitwirkung der Holz-und Faserwerkstofftechnik. In Proceedings of the SMART Rockets Projekt, Dresden, Germany, 20 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sumitomo Forestry Co. Ltd.; National University Corporation Kyoto Press Release. Sumitomo Forestry. Available online: https://sfc.jp/information/news/2020/2020-12-23.html (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Sumitomo Forestry Co., Ltd. Completed World’s First 10-Month Wood Exposure Experiment in Space—Expanding Use of Wood and Aiming to Launch a Wooden Artificial Satellite (LignoSat), 10. Available online: https://sfc.jp/information/news/pdf/2023-05-12.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Harper, J. Japan Developing Wooden Satellites to Cut Space Junk. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-55463366 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- SIC Human Spaceology Center LignoSat Project. Available online: https://space.innovationkyoto.org/lignosat-project/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Doi, T. Returning from Space, the Dream Continues READYFOR. Available online: https://readyfor.jp/projects/115388 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- The Kyoto University Space Wood Project. [@spaceKUwood]. X Twitter. 2023. Available online: https://x.com/spaceKUwood/status/1659051873272483841 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- SIC Human Spaceology Center LignoSat COMM—LignoSat Introduction COMM Group. Available online: https://space.innovationkyoto.org/2023/08/08/lignosat_comm/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- ESA (European Space Agency). ESA Flying Payloads on Wooden Satellite. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Engineering_Technology/ESA_flying_payloads_on_wooden_satellite (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- WISA. Plywood The Launch of WISA Woodsat is Delayed due to Frequency Licensing WISA PLYWOOD. Available online: https://www.wisaplywood.com/news-and-stories/news/2021/10/the-launch-of-wisa-woodsat-is-delayed-due-to-frequency-licensing/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Jari One Year After Making Our Project Public: Now Ready and Waiting Arctic Astronautics Kitsat. Available online: https://kitsat.fi/2022-04_one-year-after-making-our-project-public-now-ready-and-waiting (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Höyhtyä, M.; Boumard, S.; Yastrebova, A.; Järvensivu, P.; Kiviranta, M.; Anttonen, A. Sustainable Satellite Communications in the 6G Era: A European View for Multilayer Systems and Space Safety. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99973–100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huld. World’s First Wooden Satellite Prepares for Launch. Available online: https://huld.io/news/worlds-first-wooden-satellite-prepares-for-launch/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Arctic Astronautics. Arctic Astronautics Fotostream. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/arcticastronautics/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Ranger 5—NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1962-055A. Available online: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1962-055A (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Cooper, J. Ranger Impact Limiter. Available online: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/blog/2013/11/ranger-impact-limiter (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Cundall, D. Balsa-Wood Impact Limiters for Hard Landing on the Surface of Mars. In Proceedings of the Stepping Stones to Mars Meeting; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Baltimore, MD, USA, 28–30 March 1966. [Google Scholar]

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Ranger 4—NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1962-012A. Available online: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1962-012A (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Ranger 3—NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1962-001A. Available online: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1962-001A (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Zajączkowski, K. Ranger 5 Spacecraft Diagram. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55899197 (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- The Henry Ford; Orr, J. A Spacecraft Made of Wood? Ford’s Lunar Capsule—The Henry Ford Blog—Blog—The Henry Ford. Available online: https://www.thehenryford.org/explore/blog/a-spacecraft-made-of-wood-ford-s-lunar-capsule (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Bilstein, R.E. Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles; The NASA History Series; Scientific and Technocal Information Branch NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1980.

- Bauer, H.E. Operational Experiences on the Saturn V S-IVB Stage; Society of Automotive Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1968; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Saturn Apollo Program. Available online: https://images.nasa.gov/details-0100983 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Harvey, B. China in Space: The Great Leap Forward; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-19588-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, M. FSW. Available online: http://www.astronautix.com/f/fsw.html (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Wood Cloud. What Are the Benefits of Using Wood for Satellite Casings? Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1748282125301212178&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Teitel, A.S. Can a Wood Heat Shield Really Work? Available online: https://vintagespace.wordpress.com/2016/12/05/can-a-wood-heat-shield-really-work/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Big Tech Magazine—Going up and Coming Back—The Birth of China’s First Recoverable Satellite. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1720551144331848609&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Deutsches Zentrum für Luft-und Raumfahrt (DLR). Institut für Aerodynamik und Strömungstechnik. In Proceedings of the Lichtbogenbeheizter Windkanal 2 (L2K), Köln, Germany, 1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

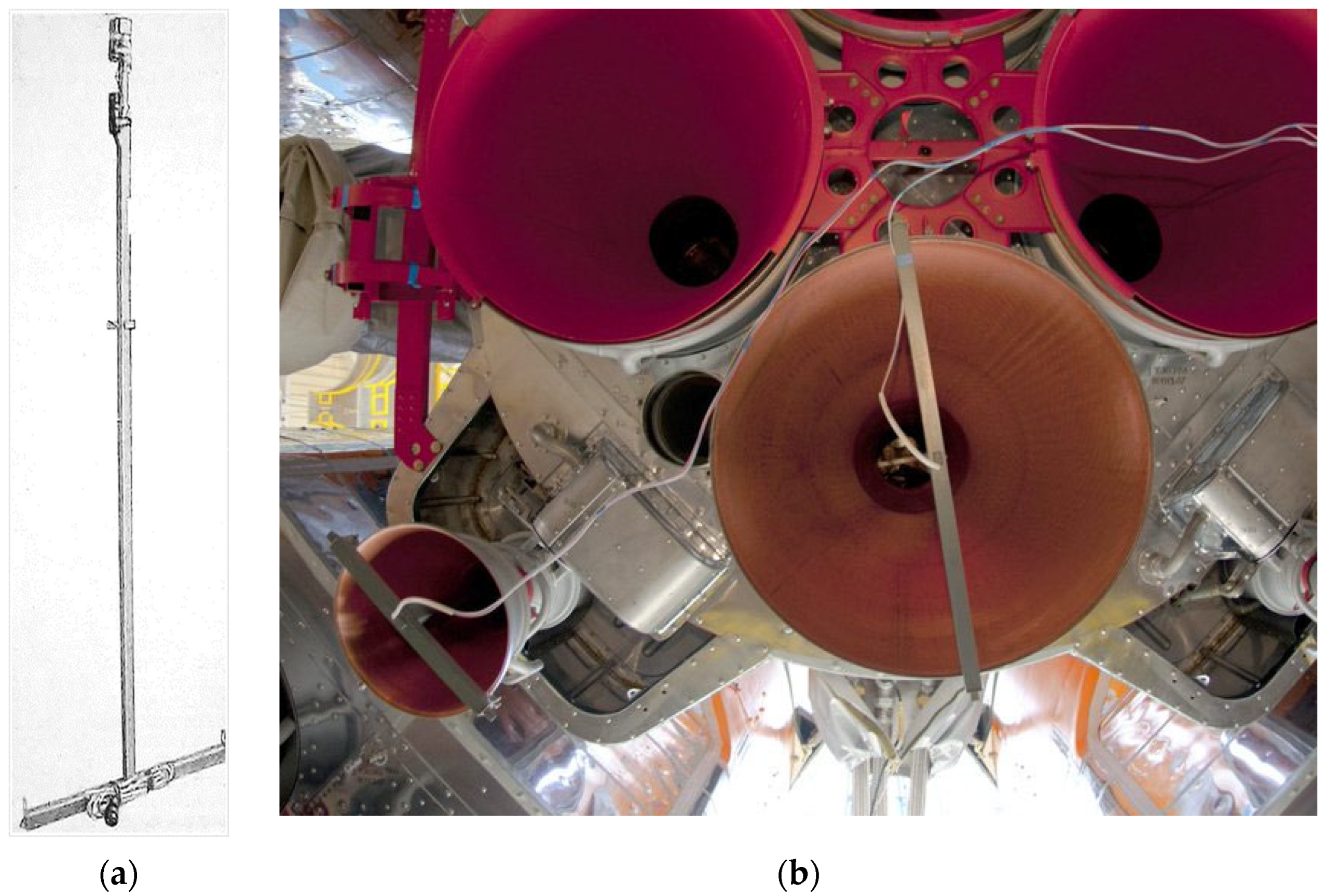

- Zak, A. Russia Lights It’s Rockets with a Giant Match. Available online: https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/rockets/a19966/russia-actually-lights-it-rockets-with-a-giant-match/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Fatuev, I.Y.; Ganin, A.A. New Propellants Ignition System in LV Soyuz Rocket Engine Chambers. In Proceedings of the 55th International Astronautical Congress of the International Astronautical Federation, the International Academy of Astronautics, and the International Institute of Space Law, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4–8 October 2004; International Astronautical Congress (IAF): Paris, France; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zak, A. Soyuz Delivers Resurs-P3. Available online: https://www.russianspaceweb.com/resurs-p3.html (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- DutchSpace. Had a Look for the #Soyuz PZU (Ignition Device) in Kourou, Here It Is During a Test Install in 2011. Twitter. 2016. Available online: https://x.com/DutchSpace/status/710468701166948354 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- ECSS-E-HB-11A; Technology Readiness Level (TRL) Guidelines. ECSS Secretariat, ESA-ESTEC Requirements and Standards Division, European Cooperation for Space Standardization: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2017.

- Wagenführ, R. Anatomie des Holzes; DRW-Verlag Weinbrenner GmbH & Co. KG: Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany, 1999; ISBN 3-87181-351-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R. The “File Drawer Problem” and Tolerance for Null Results. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | |

|---|---|

| TRL 1 | Basic principles observed and reported |

| TRL 2 | Technology concept and/or application formulated |

| TRL 3 | Analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof-of-concept |

| TRL 4 | Component and/or breadboard functional verification in laboratory environment |

| TRL 5 | Component and/or breadboard critical function verification in a relevant environment |

| TRL 6 | Model demonstrating the critical functions of the element in a relevant environment |

| TRL 7 | Model demonstrating the element performance for the operational environment |

| TRL 8 | Actual system completed and accepted for flight (“flight qualified”) |

| TRL 9 | Actual system “flight proven” through successful mission operations |

| Name | Type | Component | Type of Wooden Material | Date of Design/ First Application | Type of Application | TRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachem Ba 349 | Launch vehicle | Stubby wings, parts of fuselage and cockpit | Plywood | 1944 (testing), 01.03.1945 (launch) | Structural | 7 |

| Rheintochter | Missile | Fins | Plywood | November 1942 | Structural | 7 |

| Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1 | Rocket- powered aircraft | Almost entire aircraft (wings, fuselage, cockpit) | Plywood | 1941(testing), 15.05.1942 (first flight) | Structural | 8 |

| SMART Rockets | Launch vehicle | Nose cone | Red beech veneer | 2013 | Structural | 3 |

| LignoSat | Satellite (Cubesat) | Outer surfaces | Wild cherry, Japanese magnolia (preferred) | Launch planned for 2024 * | Structural | 7 |

| WISA Woodsat | Satellite (Cubesat) | Outer surfaces | Dried birch plywood coated with thin aluminum layer | Launch planned for 2024 | Structural | 7 |

| Ranger 3, 4 and 5 | Spacecraft | Impact limiter | End grain of balsa wood | 1962 | Damping | 7 |

| Saturn V | Launch vehicle | S-IV and S-IVB tank insulation | Balsa wood | 1960s | Thermal | 3 |

| FSW (Fanhui Shi Weixing) | Satellite | Heat shield | Impregnated white oak | 1974–2016 | Thermal | 9 |

| TPSea | Launch vehicle, (satellite) | Leading edge | Wood-fiber based material | Since 2022 | Thermal/ structural | 4 |

| PZU (Pyrotechnic ignitiondevice) | Engine ignition | Ignition structure | Birch wood | Since 1950s | Ignition structure | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guenther, R.; Tajmar, M.; Bach, C. Wood and Wood-Based Materials in Space Applications—A Literature Review of Use Cases, Challenges and Potential. Aerospace 2024, 11, 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110910

Guenther R, Tajmar M, Bach C. Wood and Wood-Based Materials in Space Applications—A Literature Review of Use Cases, Challenges and Potential. Aerospace. 2024; 11(11):910. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110910

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuenther, Raphaela, Martin Tajmar, and Christian Bach. 2024. "Wood and Wood-Based Materials in Space Applications—A Literature Review of Use Cases, Challenges and Potential" Aerospace 11, no. 11: 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110910

APA StyleGuenther, R., Tajmar, M., & Bach, C. (2024). Wood and Wood-Based Materials in Space Applications—A Literature Review of Use Cases, Challenges and Potential. Aerospace, 11(11), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace11110910