Climate Change and Health Systems: A Scoping Review of Health Professionals’ Perceptions and Readiness for Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do health professionals perceive the impacts of climate change on health and health systems?

- How do health professionals assess their role, as well as the preparedness, resilience, and sustainability of the health system to address climate change?

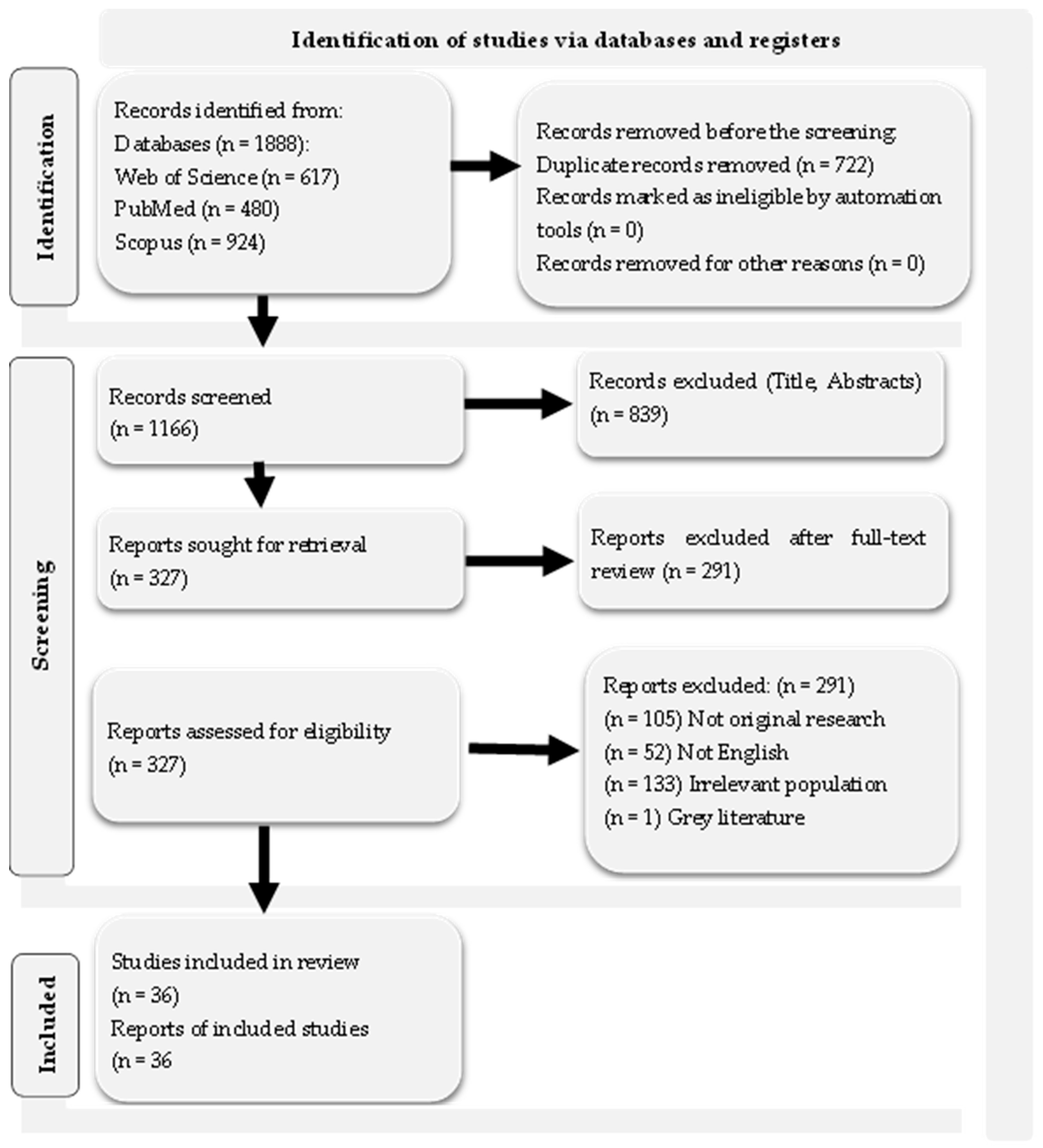

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Evaluation Process

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

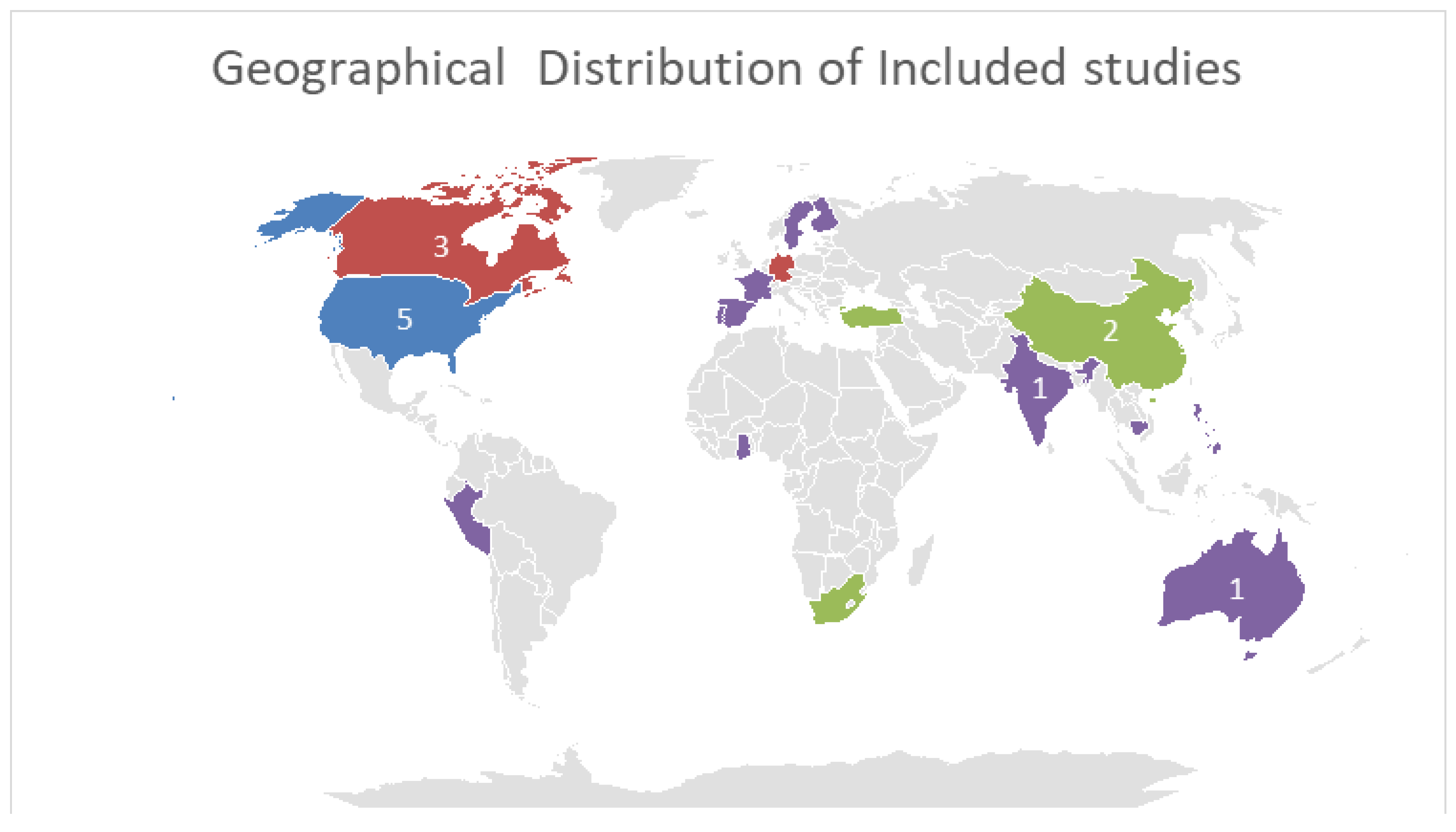

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Health Professionals’ Views on Climate Change and Its Public Health Implications

3.2.1. Awareness of Climate Change and Its Causes

3.2.2. Perceived Impact on Health and Health Systems

3.2.3. Perceptions of Training and Education

3.3. Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Their Role and Preparedness, Sustainability and Resilience to Face the Challenges Posed by Climate Change

3.3.1. Factors Affecting Environmental Sustainability

3.3.2. Readiness of Health Systems and Health Workers

Health Professionals’ Views Health Systems’ on Weaknesses in Addressing the Impacts of Climate Change

Attitudes and Perceptions of Health Professionals Regarding Their Participation in Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies

3.3.3. Ways to Address Barriers to Adoption of Adaptation and Mitigation Measures

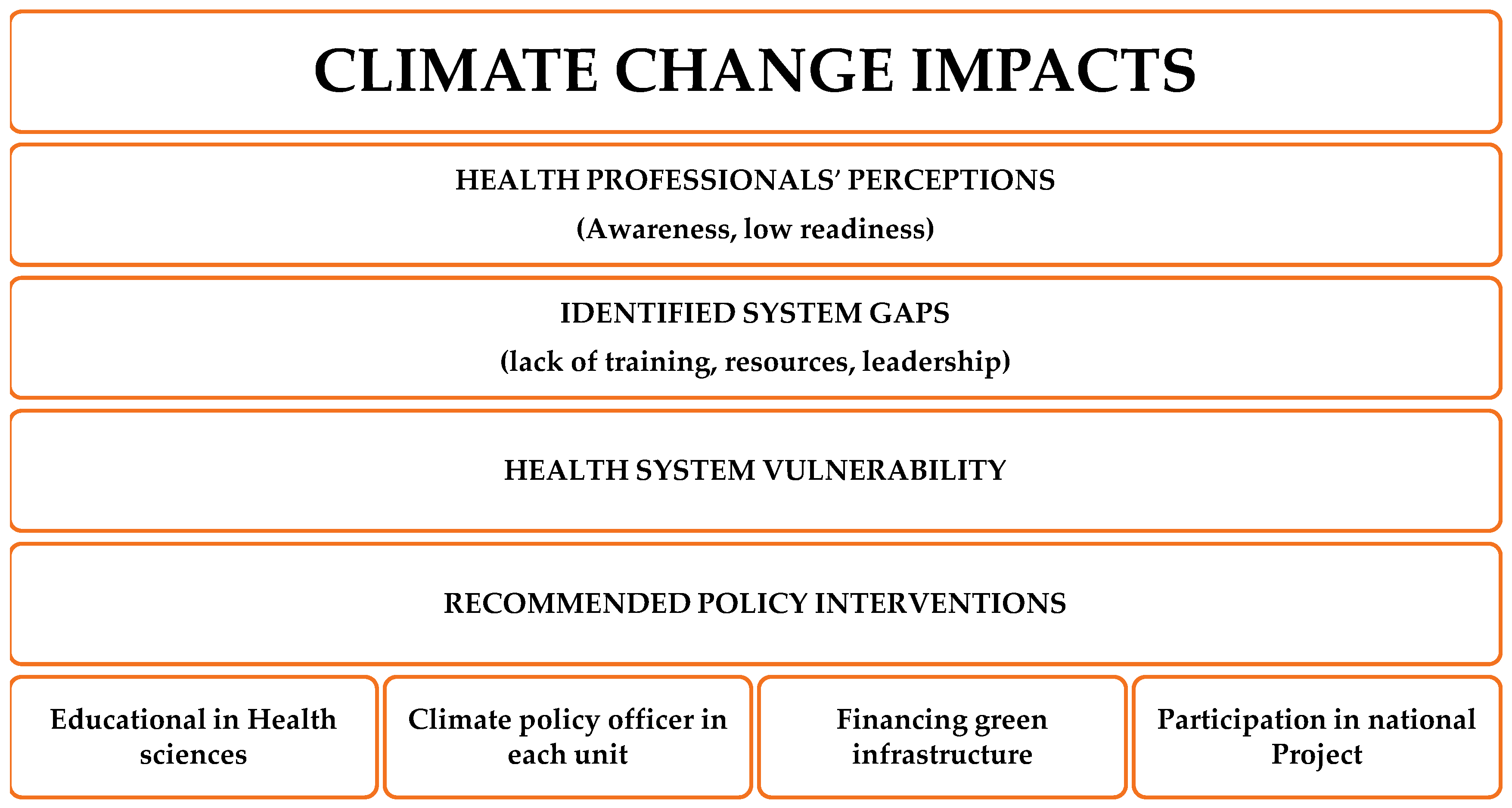

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution of Study Findings and Discussion with Findings from Other Studies

4.2. Policy Implications and Recommendations

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

Appendix A

| Research Database | Search String-(Run: 20 January 2025) |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“climate change”[MeSH Terms] OR “global warming”[MeSH Terms] OR “climate crisis” OR “extreme weather” OR “environmental change”) AND (“health personnel”[MeSH Terms] OR “health professionals” OR “healthcare workers” OR nurses OR physicians OR “public health staff”) AND (percept * OR attitude * OR belief * OR knowledge OR awareness OR experience OR practice * OR readiness OR prepare * OR opinion OR response OR competency) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( (“climate change” OR “climate crisis” OR “global warming” OR “extreme weather”) AND (“health professionals” OR “healthcare personnel” OR “health workers” OR nurses OR physicians OR “public health staff”) AND (percept * OR awareness OR knowledge OR belief * OR attitude * OR preparedness OR readiness OR prepare * OR experience OR opinion OR response OR practice *)) |

| Web of Science | TS = ( (“climate change” OR “global warming” OR “climate crisis” OR “extreme weather”) AND (“health professionals” OR “health personnel” OR nurses OR physicians OR “public health workers”) AND (percept * OR awareness OR knowledge OR attitude * OR belief * OR opinion OR readiness OR preparedness OR response OR experience OR practice *)) |

| Research Database | Fields Searched | MeSH Explosion/Notes | Filters/Limits | Years | Search Date | Hits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Title/Abstract | MeSH explosion: Enabled | Language: English; Humans; Article type: Peer-reviewed journal articles | 2016–2025 | 20 March 2025 | 375 |

| Scopus | Title/Abstract | Language: English; Document type: Article | 2016–2025 | 20 March 2025 | 924 | |

| Web of Science | Title/Abstract | Language: English; Document type: Article | 2016–2025 | 20 March 2025 | 617 |

Appendix B

| A/A | Title | Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Factors affecting environmental sustainability attitudes among nurses–Focusing on climate change cognition and behaviors: A cross-sectional study” | Chung et al. [67] | 2024 | Korea | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 352 Nurses | The key factors influencing nurses’ attitudes toward environmental sustainability are: (1) environmental attitudes at work (2) interest in climate issues and, (3) motivation to adopt sustainable practices. |

| 2. | “Knowledge, attitudes and practices related to climate change and its health aspects among the healthcare workforce in India—A cross-sectional study” | Sambath et al. [57] | 2022 | India | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 3185 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 3. | “Climate Change and Health Preparedness in Africa: Analysing Trends in Six African Countries” | Opoku et al. [41] | 2021 | Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Namibia, Ethiopia, Ethiopia and Kenya | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 122 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 4. | “Environmental health practitioners potentially play a key role in helping communities adapt to climate change” | Shezi et al. [49] | 2019 | South Africa | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 66 Environmental health professionals |

|

| 5. | “Climate-specific health literacy in health professionals: an exploratory study” | Albrecht et al. [58] | 2023 | Germany | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 142 Health professionals |

|

| 6. | “Nurses’ Perceptions and Behaviors Regarding Climate Change and Health: A Quantile Regression Analysis” | Park et al. [50] | 2024 | Korea | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 499 Nurses |

|

| 7. | “Climate and health concerns of Montana’s public and environmental health professionals: a cross-sectional study” | Byron & Akerlof [51] | 2021 | USA, Montana | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 479 Environmental and Public Health Professionals |

|

| 8. | “Interventional pain physician beliefs on climate change: A Spine Intervention Society (SIS) survey” | Fogarty et al. [14] | 2023 | USA | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 175 members of Spine Intervention Society |

|

| 9. | “Comparisons of healthcare personnel relating to awareness, concern, motivation, and behaviors of climate and health: A cross-sectional study” | Rangel et al. [64] | 2024 | Western USA | Exploratory-observational-contemporary study | n = 1363 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 10. | “Perception of environmental issues in the head-and-neck surgery room: A preliminary study” | Carsuzaa et al. [65] | 2024 | France | Observational pilot study | n = 267 Healthcare professionals working in head and neck surgery |

|

| 11. | “Keeping Sane in a Changing Climate: Assessing Psychologists’ Preparedness, Exposure to Climate-Health Impacts, Willingness to Act on Climate Change, and Barriers to Effective Action” | Stilita & Charlson [52] | 2024 | Australia | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 59 Psychologists |

|

| 12. | “Nurses’ Environmental Practices in Northern Peruvian Hospitals” | Rojas-Perez et al. [68] | 2024 | Peru | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 106 Nurses |

|

| 13. | “Green radiography: Exploring perceptions, practices, and barriers to sustainability” | Rawashdeh et al. [53] | 2024 | 14 countries | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 104 Radiographers |

|

| 14. | “Perceptions of capacity for infectious disease control and prevention to meet the challenges of dengue fever in the face of climate change: A survey among CDC staff in Guangdong Province, China” | Tong et al. [59] | 2016 | China | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 260 CDC professionals |

|

| 15. | ‘Awareness, worry, and hope regarding climate change among nurses: A cross-sectional study” | Fertelli et al. [66] | 2023 | Turkey | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 511 Nurses |

|

| 16. | “Assessing the role of education level on climate change belief, concern and action: a multinational survey of healthcare professionals in nephrology” | Sandal et al. [54] | 2025 | 107 Countries | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 849 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 17. | “Pharmacists’ perception of climate change and its impact on health” | Speck et al. [55] | 2023 | USA, Ohio | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 70 Registered pharmacists |

|

| 18. | “Public health professionals’ views on climate change, advocacy, and health” | Kish-Doto & Francavillo [56] | 2024 | USA | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 173 Public health professionals |

|

| 19. | “Climate change, climate disasters and oncology care: a descriptive global survey of oncology healthcare professionals” | Elia et al. [42] | 2024 | Participation of a sample of 26 countries | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 154 Healthcare professionals for oncology patients |

|

| 20. | “Survey of International Members of the American Thoracic Society on Climate Change and Health” | Sarfaty et al. [43] | 2016 | Participant sample from 68 countries | Quantitative, Synchronic study | n = 489 International Members of the American Thoracic Society |

|

| 21. | “South African Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Environmental Sustainability in Healthcare: A Mixed-Methods Study” | Lister et al. [44] | 2022 | South Africa | Mixed method (Quantitative and Qualitative Study) | n = 100 Health professionals (questionnaire) N = 18 Health professionals (semi-structured interviews) |

|

| 22. | “The environmental awareness of nurses as environmentally sustainable health care leaders: a mixed method analysis” | Luque-Alcaraz et al. [75] | 2024 | Spain, Andalusia | Mixed method (Quantitative and Qualitative Study) | n = 314 Nurses (questionnaire) N = 10 Nurses (semi-structured interviews) |

|

| 23. | “Are we ready for it? Health systems preparedness and capacity towards climate change-induced health risks: perspectives of health professionals in Ghana” | Hussey & Arku [45] | 2020 | Ghana | Mixed method (Quantitative and Qualitative Study) | n = 99 Health professionals (questionnaire) N = 20 Health professionals (interviews) |

|

| 24. | “We are not ready for this”: physicians’ perceptions on climate change information and adaptation strategies qualitative study in Portugal” | Ponte et al. [69] | 2024 | Portugal | Qualitative Study (case study) | n = 13 Doctors |

|

| 25. | “Nurses’ perceptions of climate and environmental issues: a qualitative study” | Anåker et al. [46] | 2015 | Sweden | Descriptive, exploratory qualitative study | n = 18 Nurses |

|

| 26. | “A qualitative study of what motivates and enables climate-engaged physicians in Canada to engage in health-care sustainability, advocacy, and action” | Luo et al. [60] | 2023 | Canada | Descriptive, exploratory qualitative study | n = 19 Doctors dealing with climate |

|

| 27. | “Finnish nurses’ perceptions of the health impacts of climate change and their preparation to address those impacts” | Iira et al. [61] | 2021 | Finland | Qualitative descriptive study | n = 6 Nurses |

|

| 28. | “Filipino nurses’ experiences and perceptions of the impact of climate change on healthcare delivery and cancer care in the Philippines: a qualitative exploratory survey” | Tanay et al. [76] | 2023 | Philippines | Descriptive qualitative exploratory study | n = 46 Nurses |

|

| 29. | “There’s Not Really Much Consideration Given to the Effect of the Climate on NCDs”—Exploration of Knowledge and Attitudes of Health Professionals on a Climate Change-NCD Connection in Barbados” | Springer & Elliott [47] | 2019 | Barbados, Caribbean | Qualitative Study Case Study | n = 10 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 30. | “The perspectives of nurses, as prominent advocates in sustainability, on the global climate crises and its impact on mental health” | Ediz & Uzun [70] | 2024 | Turkey | Qualitative study | n = 35 Nurses |

|

| 31. | “Climate-conscious pharmacy practice: An exploratory study of community pharmacists in Ontario” | Zhao et al. [48] | 2024 | Canada, Ontario | Exploratory qualitative study | n = 24 Community pharmacists |

|

| 32. | “General Practitioners’ Perceptions of Heat Health Impacts on the Elderly in the Face of Climate Change—A Qualitative Study in Baden-Württemberg, Germany” | Herrmann & Sauerborn [71] | 2018 | Germany, Baden-Württemberg | Qualitative study | n = 24 General Practitioners |

|

| 33. | “Building resilience in German primary care practices: a qualitative study” | Litke et al. [72] | 2022 | Germany | Qualitative Observation Study | n = 40 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 34. | “Heatwaves, hospitals and health system resilience in England: a qualitative assessment of frontline perspectives from the hot summer of 2019” | Brooks et al. [62] | 2023 | UK | Qualitative study | n = 14 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 35. | ‘”We have a plan for that’: a qualitative study of health system resilience through the perspective of health workers managing antenatal and childbirth services during floods in Cambodia” | Saulnier et al. [73] | 2022 | Cambodia | Qualitative study | n = 34 Healthcare professionals |

|

| 36. | “Experts’ Perceptions on China’s Capacity to Manage Emerging and Re-emerging Zoonotic Diseases in an Era of Climate Change” | Hansen et al. [74] | 2017 | China | Qualitative study | n = 30 specialists in infectious diseases |

|

References

- Wu, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Xu, B. Impact of Climate Change on Human Infectious Diseases: Empirical Evidence and Human Adaptation. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marwani, S. Climate Change Impact on the Healthcare Provided to Patients. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2023, 47, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covert, H.H.; Abdoel Wahid, F.; Wenzel, S.E.; Lichtveld, M.Y. Climate Change Impacts on Respiratory Health: Exposure, Vulnerability, and Risk. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 2507–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agache, I.; Sampath, V.; Aguilera, J.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Barry, M.; Bouagnon, A.; Chinthrajah, S.; Collins, W.; Dulitzki, C.; et al. Climate Change and Global Health: A Call to More Research and More Action. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 1389–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, L.; Conlon, K.C.; Sorensen, C.; McEachin, S.; Nadeau, K.; Kakkad, K.; Kizer, K.W. Climate Change and Extreme Heat Events: How Health Systems Should Prepare. NEJM Catal. 2022, 3, CAT-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C.; Ebi, K.L. Climate Change Impact on Migration, Travel, Travel Destinations and the Tourism Industry. J. Travel Med. 2019, 26, taz026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, M.; Erguler, K.; Ahmady-Birgani, H.; DaifAllah AL-Hmoud, N.; Fears, R.; Gogos, C.; Hobbhahn, N.; Koliou, M.; Kostrikis, L.G.; Lelieveld, J.; et al. Climate Change and Human Health in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: Literature Review, Research Priorities and Policy Suggestions. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baal, K.; Stiel, S.; Schulte, P. Public Perceptions of Climate Change and Health—A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokmic-Tomkins, Z.; Block, L.J.; Davies, S.; Reid, L.; Ronquillo, C.E.; von Gerich, H.; Peltonen, L.M. Evaluating the Representation of Disaster Hazards in SNOMED CT: Gaps and Opportunities. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2023, 30, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Spinthiropoulos, K. Integration of Remote Sensing and GIS for Urban Sprawl Monitoring in European Cities. Eur. J. Geogr. 2025, 16, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gkouliaveras, V.; Kalogiannidis, S.; Kalfas, D.; Kontsas, S. Effects of Climate Change on Health and Health Systems: A Systematic Review of Preparedness, Resilience, and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Hess, J.J. Health Risks Due to Climate Change: Inequity in Causes and Consequences. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2056–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosadeghrad, A.M.; Isfahani, P.; Eslambolchi, L.; Zahmatkesh, M.; Afshari, M. Strategies to Strengthen a Climate-Resilient Health System: A Scoping Review. Global Health 2023, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, A.E.; Godambe, M.; Duszynski, B.; McCormick, Z.L.; Steensma, J.; Decker, G. Interventional Pain Physician Beliefs on Climate Change: A Spine Intervention Society (SIS) Survey. Interv. Pain Med. 2023, 2, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuyet Hanh, T.T.; Huong, L.T.T.; Huong, N.T.L.; Linh, T.N.Q.; Quyen, N.H.; Nhung, N.T.T.; Ebi, K.; Cuong, N.D.; Van Nhu, H.; Kien, T.M.; et al. Vietnam Climate Change and Health Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment, 2018. Environ. Health Insights 2020, 14, 1178630220924658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani Hosseini, M.; Zargoush, M.; Ghazalbash, S. Climate Crisis Risks to Elderly Health: Strategies for Effective Promotion and Response. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Hess, J.; Luber, G.; Malilay, J.; McGeehin, M. Climate Change: The Public Health Response. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrikhande, S.; Merten, S.; Cambaco, O.; Lee, T.T.; Lakshmanasamy, R.; Röösli, M.; Dalvie, M.A.; Utzinger, J.; Cissé, G. Barriers to Climate Change and Health Research in India: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e073381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Vanos, J.; Baldwin, J.W.; Bell, J.E.; Hondula, D.M.; Errett, N.A.; Hayes, K.; Reid, C.E.; Saha, S.; Spector, J.; et al. Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population Health and Health System Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2020, 42, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, E.; Bills, C.B.; Calvello Hynes, E.J.; Stassen, W.; Rublee, C. Climate Change and Emergency Care in Africa: A Scoping Review. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 12, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreslake, J.M.; Sarfaty, M.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Leiserowitz, A.A.; Maibach, E.W. The Critical Roles of Health Professionals in Climate Change Prevention and Preparedness. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, S68–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Generoso, S.V.; Viana, M.L.; Santos, R.G.; Arantes, R.M.E.; Martins, F.S.; Nicoli, J.R.; Machado, J.A.N.; Correia, M.I.T.D.; Cardoso, V.N. Protection against Increased Intestinal Permeability and Bacterial Translocation Induced by Intestinal Obstruction in Mice Treated with Viable and Heat-Killed Saccharomyces Boulardii. Eur. J. Nutr. 2011, 50, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares-Espinós, E.; Hernández, V.; Domínguez-Escrig, J.L.; Fernández-Pello, S.; Hevia, V.; Mayor, J.; Padilla-Fernández, B.; Ribal, M.J. Metodología de Una Revisión Sistemática. Actas Urológicas Españolas 2018, 42, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The Private Sector and the SDGs: The Need to Move Beyond ‘Business as Usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidt, S.; Vavken, P.; Jacobs, C.; Koob, S.; Cucchi, D.; Kaup, E.; Wirtz, D.C.; Wimmer, M.D. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Z. Orthop. Unfall. 2019, 157, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, J.; Maibach, E.W. Health Implications of Climate Change: A Review of the Literature About the Perception of the Public and Health Professionals. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, J.; Burnand, B. Role of Health Professionals Regarding the Impact of Climate Change on Health—An Exploratory Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, K.; DeBono, R.; Berry, P.; Leiserowitz, A.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Clarke, K.-L.; Rogaeva, A.; Nisbet, M.C.; Weathers, M.R.; Maibach, E.W. Public Perceptions of Climate Change as a Human Health Risk: Surveys of the United States, Canada and Malta. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 2559–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Operational Framework for Building Climate Resilient Health Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, R.N.; Friend, T.H.; Bernstein, A.; Jha, A.K. Adding A Climate Lens To Health Policy In The United States. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarfaty, M. How Physicians Should Respond to Climate Change. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2024, 37, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffling, K. Nurses Drawdown: Building a Nurse-Led, Solutions-Based Quality Improvement Project to Address Climate Change. Creat. Nurs. 2021, 27, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, C.; Hess, J.; Phung, D.; Huang, C. Health Professionals in a Changing Climate: Protocol for a Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediz, Ç.; Uzun, S. Exploring Nursing Students’ Metaphorical Perceptions and Cognitive Structures Related to the Global Climate Crisis’s Impact on Nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2025, 42, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olde Rikkert, M.; Jambroes, M.; Opstelten, W. Health professionals for the climate. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2021, 165, D6317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanner, A.; Perdrix, J. Changement Climatique et Santé: Le Point de Vue Des Professionnels de Santé Aux Quatre Coins Du Monde. Rev. Med. Suisse 2021, 17, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Lancaster University: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Opoku, S.K.; Filho, W.L.; Hubert, F.; Adejumo, O. Climate Change and Health Preparedness in Africa: Analysing Trends in Six African Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elia, M.R.; Toygar, I.; Tomlins, E.; Bagcivan, G.; Parsa, S.; Ginex, P.K. Climate Change, Climate Disasters and Oncology Care: A Descriptive Global Survey of Oncology Healthcare Professionals. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfaty, M.; Kreslake, J.; Ewart, G.; Guidotti, T.L.; Thurston, G.D.; Balmes, J.R.; Maibach, E.W. Survey of International Members of the American Thoracic Society on Climate Change and Health. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1808–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, H.E.; Mostert, K.; Botha, T.; van der Linde, S.; van Wyk, E.; Rocher, S.-A.; Laing, R.; Wu, L.; Müller, S.; des Tombe, A.; et al. South African Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Environmental Sustainability in Healthcare: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussey, L.K.; Arku, G. Are We Ready for It? Health Systems Preparedness and Capacity towards Climate Change-Induced Health Risks: Perspectives of Health Professionals in Ghana. Clim. Dev. 2020, 12, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anåker, A.; Nilsson, M.; Holmner, Å.; Elf, M. Nurses’ Perceptions of Climate and Environmental Issues: A Qualitative Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, R.A.; Elliott, S.J. “There’s Not Really Much Consideration Given to the Effect of the Climate on NCDs”—Exploration of Knowledge and Attitudes of Health Professionals on a Climate Change-NCD Connection in Barbados. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Gregory, P.A.M.; Austin, Z. Climate-Conscious Pharmacy Practice: An Exploratory Study of Community Pharmacists in Ontario. Can. Pharm. J. Rev. Pharm. Can. 2024, 157, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shezi, B.; Mathee, A.; Siziba, W.; Street, R.A.; Naicker, N.; Kunene, Z.; Wright, C.Y. Environmental Health Practitioners Potentially Play a Key Role in Helping Communities Adapt to Climate Change. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.K.; Baek, S.; Jeong, D.W.; Kim, G.S. Nurses’ Perceptions and Behaviours Regarding Climate Change and Health: A Quantile Regression Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 81, 8218–8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byron, L.; Akerlof, K.L. Climate and Health Concerns of Montana’s Public and Environmental Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilita, G.; Charlson, F. Keeping Sane in a Changing Climate: Assessing Psychologists’ Preparedness, Exposure to Climate-Health Impacts, Willingness to Act on Climate Change, and Barriers to Effective Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, M.; Ali, M.A.; McEntee, M.; El-Sayed, M.; Saade, C.; Kashabash, D.; England, A. Green Radiography: Exploring Perceptions, Practices, and Barriers to Sustainability. Radiography 2024, 30, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandal, S.; Onu, U.; Fung, W.; Pippias, M.; Smyth, B.; De Chiara, L.; Bajpai, D.; Bilchut, W.H.; Hafiz, E.; Kelly, D.M.; et al. Assessing the Role of Education Level on Climate Change Belief, Concern and Action: A Multinational Survey of Healthcare Professionals in Nephrology. J. Nephrol. 2025, 38, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, C.L.; Mager, N.A.D.; Mager, J.N. Pharmacists’ Perception of Climate Change and Its Impact on Health. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Doto, J.; Francavillo, G.R. Public Health Professionals’ Views on Climate Change, Advocacy, and Health. J. Commun. Healthc. 2024, 18, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambath, V.; Narayan, S.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, P.; Pradyumna, A. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Related to Climate Change and Its Health Aspects among the Healthcare Workforce in India–A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2022, 6, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, L.; Reismann, L.; Leitzmann, M.; Bernardi, C.; von Sommoggy, J.; Weber, A.; Jochem, C. Climate-Specific Health Literacy in Health Professionals: An Exploratory Study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1236319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, M.X.; Hansen, A.; Hanson-Easey, S.; Xiang, J.; Cameron, S.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Weinstein, P.; Han, G.-S.; et al. Perceptions of Capacity for Infectious Disease Control and Prevention to Meet the Challenges of Dengue Fever in the Face of Climate Change: A Survey among CDC Staff in Guangdong Province, China. Environ. Res. 2016, 148, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, O.D.; Razvi, Y.; Kaur, G.; Lim, M.; Smith, K.; Carson, J.J.K.; Petrin-Desrosiers, C.; Haldane, V.; Simms, N.; Miller, F.A. A Qualitative Study of What Motivates and Enables Climate-Engaged Physicians in Canada to Engage in Health-Care Sustainability, Advocacy, and Action. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e164–e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iira, T.; Ruth, M.-L.; Hannele, T.; Jouni, J.; Lauri, K. Finnish Nurses’ Perceptions of the Health Impacts of Climate Change and Their Preparation to Address Those Impacts. Nurs. Forum 2021, 56, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, K.; Landeg, O.; Kovats, S.; Sewell, M.; OConnell, E. Heatwaves, Hospitals and Health System Resilience in England: A Qualitative Assessment of Frontline Perspectives from the Hot Summer of 2019. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, N.; Légaré, A.-G.; Diallo, T.; Sasseville, M.; Gadio, S.; Lessard, L. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Quebec Nurses Relating to Climate Change in the Context of Their Practice with Children Aged 0 to 5 Years: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 57, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, T.; Johnson, S.E.; Joubert, P.; Timmerman, R.; Smith, S.; Springer, G.; Schenk, E. Comparisons of Healthcare Personnel Relating to Awareness, Concern, Motivation, and Behaviours of Climate and Health: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 81, 8191–8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carsuzaa, F.; Fieux, M.; Bartier, S.; Fath, L.; Alexandru, M.; Legré, M.; Favier, V. Perception of Environmental Issues in the Head-and-Neck Surgery Room: A Preliminary Study. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2024, 141, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertelli, T.K. Awareness, Worry, and Hope Regarding Climate Change among Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2023, 78, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Lee, H.; Jang, S.J. Factors Affecting Environmental Sustainability Attitudes among Nurses–Focusing on Climate Change Cognition and Behaviours: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Perez, H.L.; Díaz-Vásquez, M.A.; Díaz-Manchay, R.J.; Zeña-Ñañez, S.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Smith, D. Nurses’ Environmental Practices in Northern Peruvian Hospitals. Workplace Health Saf. 2024, 72, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, N.; Alves, F.; Vidal, D.G. “We Are Not Ready for This”: Physicians’ Perceptions on Climate Change Information and Adaptation Strategies-Qualitative Study in Portugal. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1506120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediz, Ç.; Uzun, S. The Perspectives of Nurses, as Prominent Advocates in Sustainability, on the Global Climate Crises and Its Impact on Mental Health. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 81, 8266–8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.; Sauerborn, R. General Practitioners’ Perceptions of Heat Health Impacts on the Elderly in the Face of Climate Change—A Qualitative Study in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litke, N.; Weis, A.; Koetsenruijter, J.; Fehrer, V.; Koeppen, M.; Kuemmel, S.; Szecsenyi, J.; Wensing, M. Building Resilience in German Primary Care Practices: A Qualitative Study. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulnier, D.D.; Thol, D.; Por, I.; Hanson, C.; von Schreeb, J.; Alvesson, H.M. ‘We Have a Plan for That’: A Qualitative Study of Health System Resilience through the Perspective of Health Workers Managing Antenatal and Childbirth Services during Floods in Cambodia. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.; Xiang, J.; Liu, Q.; Tong, M.X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, K.; Cameron, S.; Hanson-Easey, S.; Han, G.-S.; et al. Experts’ Perceptions on China’s Capacity to Manage Emerging and Re-emerging Zoonotic Diseases in an Era of Climate Change. Zoonoses Public Health 2017, 64, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Alcaraz, O.M.; Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Gomera, A.; Vaquero-Abellán, M. The Environmental Awareness of Nurses as Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Leaders: A Mixed Method Analysis. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanay, M.A.; Quiambao-Udan, J.; Soriano, O.; Aquino, G.; Valera, P.M. Filipino Nurses’ Experiences and Perceptions of the Impact of Climate Change on Healthcare Delivery and Cancer Care in the Philippines: A Qualitative Exploratory Survey. Ecancermedicalscience 2023, 17, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlong, W.; Dietsch, E. Nursing and Climate Change: An Emerging Connection. Collegian 2015, 22, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, A.; Martin, S.; Richards, C.; Ward, I.; Tulleners, T.; Hills, D.; Wapau, H.; Levett-Jones, T.; Best, O. Enhancing Primary Healthcare Nurses’ Preparedness for Climate-Induced Extreme Weather Events. Nurs. Outlook 2024, 72, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulu, M.M.; Kivuva, M.M. Climate Change Education for Environmental Sustainability among Health Professionals: An Integrative Review. SAGE Open Nurs. 2025, 11, 23779608251351116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Operational Framework for Building Climate Resilient and Low Carbon Health Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsan, F.R.; Bloomfield, J.G.; Monrouxe, L.V. Triple Planetary Crisis: Why Healthcare Professionals Should Care. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1465662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turzáková, J.; Kohanová, D.; Solgajová, A.; Sollár, T. Association between Climate Change and Patient Health Outcomes: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, A.; Diallo, T.; Roberge, M.; Audate, P.-P.; Leblanc, N.; Jobin, É.; Moubarak, N.; Guillaumie, L.; Dupéré, S.; Guichard, A.; et al. Practicing Nurses’ and Nursing Students’ Perceptions of Climate Change: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e70043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, T.; Bérubé, A.; Roberge, M.; Audate, P.-P.; Larente-Marcotte, S.; Jobin, É.; Moubarak, N.; Guillaumie, L.; Dupéré, S.; Guichard, A.; et al. Nurses’ Perceptions of Climate Change: Protocol for a Scoping Review. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e42516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, S.Y.; Chircop, A.; Sedgwick, M.; Scott, D. Nurses’ Perceptions of Climate Sensitive Vector-borne Diseases: A Scoping Review. Public Health Nurs. 2023, 40, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela Dos Santos, O.; Perruchoud, É.; Pereira, F.; Alves, P.; Verloo, H. Measuring Nurses’ Knowledge and Awareness of Climate Change and Climate-Associated Diseases: Systematic Review of Existing Instruments. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2850–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chersich, M.F.; Wright, C.Y. Climate Change Adaptation in South Africa: A Case Study on the Role of the Health Sector. Global Health 2019, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvero, R. Climate Change and Human Health: A Primer on What Women’s Health Physicians Can Do on Behalf of Their Patients and Communities. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 36, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SteelFisher, G.K.; Blendon, R.J.; Brulé, A.S.; Lubell, K.M.; Brown, L.J.; Batts, D.; Ben-Porath, E. Physician Emergency Preparedness: A National Poll of Physicians. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2015, 9, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.; Philippe, C.; Hospedales, J.; Dresser, C.; Colebrooke, B.; Hamacher, N.; Humphrey, K.; Sorensen, C. Building Capacity of Healthcare Professionals and Community Members to Address Climate and Health Threats in The Bahamas: Analysis of a Green Climate Fund Pilot Workshop. Dialogues Health 2023, 3, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, B.X.; Hoang, M.T.; Pham, H.Q.; Hoang, C.L.; Le, H.T.; Latkin, C.A.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. The Operational Readiness Capacities of the Grassroots Health System in Responses to Epidemics: Implications for COVID-19 Control in Vietnam. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 011006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykara Mat, S. The Role of Nurses in Addressing Health Effects of Climate Change and Wildfires. Health Probl. Civiliz. 2022, 16, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akore Yeboah, E.; Adegboye, A.R.A.; Kneafsey, R. Nurses’ Perceptions, Attitudes, and Perspectives in Relation to Climate Change and Sustainable Healthcare Practices: A Systematic Review. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2024, 16, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, C.J.; Salas, R.N.; Rublee, C.; Hill, K.; Bartlett, E.S.; Charlton, P.; Dyamond, C.; Fockele, C.; Harper, R.; Barot, S.; et al. Clinical Implications of Climate Change on US Emergency Medicine: Challenges and Opportunities. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 76, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Silliman, B.R. Climate Change, Human Impacts, and Coastal Ecosystems in the Anthropocene. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R1021–R1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; D’ambrosio, M.; Cuscianna, E.; Riformato, G.; Migliore, G.; Tafuri, S.; Bianchi, F.P. Waste Management and the Perspective of a Green Hospital—A Systematic Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepetis, A.; Rizos, F.; Parlavantzas, I.; Zaza, P.N.; Nikolaou, I.E. Environmental Costs in Healthcare System: The Case Studies of Greece Health Care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.; Knowlton, K.; Shaman, J. Assessment of Climate-Health Curricula at International Health Professions Schools. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e206609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Service Executive. Climate Action Strategy 2023–2050; Health Service Executive: Dublin, Ireland, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Communicating on Climate Change and Health: Toolkit for Health Professionals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kotcher, J.; Maibach, E.; Montoro, M.; Hassol, S.J. How Americans Respond to Information About Global Warming’s Health Impacts: Evidence From a National Survey Experiment. GeoHealth 2018, 2, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrovski, V.; Schmoll, O. Priorities for Protecting Health from Climate Change in the WHO European Region: Recent Regional Activities. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforsch. Gesundheitsschutz 2019, 62, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karstila, H.; Ruuhela, R.; Rajala, R.; Roivainen, P. Recognition of Climate-Related Risks for Prehospital Emergency Medical Service and Emergency Department in Finland–A Delphi Study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 73, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, D.; Varangu, L.; Webster, R.J. A Climate Resilience Maturity Matrix for Canadian Health Systems. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2023, 36, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakonas, K.; Badyal, S.; Takaro, T.; Buse, C.G. Rapid Review of the Impacts of Climate Change on the Health System Workforce and Implications for Action. J. Clim. Change Health 2024, 19, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, F.H.; Greibe Andersen, J.; Karekezi, C.; Yonga, G.; Furu, P.; Kallestrup, P.; Kraef, C. Climate Change and Health in Urban Informal Settlements in Low- and Middle-Income Countries–a Scoping Review of Health Impacts and Adaptation Strategies. Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1908064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkaris, C.; Saeed, H.; Laubscher, L.; Eleftheriades, A.; Stavros, S.; Drakaki, E.; Potiris, A.; Panagiotopoulos, D.; Sioutis, D.; Panagopoulos, P.; et al. Eco-Friendly and COVID-19 Friendly? Decreasing the Carbon Footprint of the Operating Room in the COVID-19 Era. Diseases 2023, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmner, Å.; Rocklöv, J.; Ng, N.; Nilsson, M. Climate Change and EHealth: A Promising Strategy for Health Sector Mitigation and Adaptation. Glob. Health Action 2012, 5, 18428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yellowlees, P.M.; Chorba, K.; Burke Parish, M.; Wynn-Jones, H.; Nafiz, N. Telemedicine Can Make Healthcare Greener. Telemed. E-Health 2010, 16, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvalan, C.; Villalobos Prats, E.; Sena, A.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Karliner, J.; Risso, A.; Wilburn, S.; Slotterback, S.; Rathi, M.; Stringer, R.; et al. Towards Climate Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, M.; McGain, F. Health Care Sustainability Metrics: Building A Safer, Low-Carbon Health System. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 2080–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Berry, H.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; et al. The 2018 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Shaping the Health of Nations for Centuries to Come. Lancet 2018, 392, 2479–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. SWD(2024) 223 Final–Commission Staff Working Document: EU4Health Programme–Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework 2024; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Research Database | Information Retrieval Strategy | Search Period |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“climate change” [MeSH Terms] OR “global warming” [MeSH Terms] OR “climate crisis” OR “extreme weather” OR “environmental change”) AND (“health personnel” [MeSH Terms] OR “health professionals” OR “healthcare workers” OR “nurses” OR “physicians” OR “public health staff”) AND (percept * OR attitude * OR belief * OR knowledge OR awareness OR experience OR practice * OR readiness OR prepare * OR opinion OR response OR competency) | 20 December 2024, 20 January 2025, and 20 March 2025 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“climate change” OR “climate crisis” OR “global warming” OR “extreme weather”) AND (“health professionals” OR “healthcare personnel” OR “health workers” OR “nurses” OR “physicians” OR “public health staff”) AND (percept * OR awareness OR knowledge OR belief * OR attitude * OR preparedness OR readiness OR prepare * OR experience OR opinion OR response OR practice *) | |

| Web of Science | TS = ((“climate change” OR “global warming” OR “climate crisis” OR “extreme weather”) AND (“health professionals” OR “health personnel” OR “nurses” OR “physicians” OR “public health workers”) AND (percept * OR awareness OR knowledge OR attitude * OR belief * OR opinion OR readiness OR preparedness OR response OR experience OR practice *)) |

| PCC Element | Definition in This Review |

|---|---|

| Population | Health professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, public health staff) |

| Concept | Perceptions, awareness, preparedness, experiences, engagement, knowledge, attitudes regarding climate change |

| Context | Health systems, service delivery, and policy challenges related to climate change (e.g., resilience, adaptation, readiness) |

| Criteria | Justification |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Authors | Study | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| [33] | American Thoracic Society member survey on climate change and health. | Published before 2016 |

| [34] | Nurses Drawdown: Building a Nurse-Led, Solutions-Based Quality Improvement Project to Address Climate Change. | Not relevant to the research questions |

| [35] | Health professionals in a changing climate: protocol for a scoping review | This is not a primary study. |

| [36] | Exploring Nursing Students’ Metaphorical Perceptions and Cognitive Structures Related to the Global Climate Crisis’s Impact on Nursing | Related to students |

| [37] | Zorgprofessionals voor het klimaat [Health professionals for the climate]. | It is not in English and is not directly related to the research questions. |

| [38] | Changement climatique et santé: le point de vue des professionnels de santé aux quatre coins du monde. | Not in English |

| Perceptions | Studies |

|---|---|

| Recognizing Climate Change and linking it to human activities | [14,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Understanding the impact of climate change on human health | [14,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,51,52,53,54,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] |

| Stressing awareness raising, training and education | [44,45,48,49,50,53,54,56,57,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66] |

| Perceptions | Studies |

|---|---|

| Factors Affecting Environmental Sustainability | [67] |

| Readiness of health systems and health workers | [41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,59,60,61,64,65,68,69,70,71,72,73,74] |

| Barriers to Adoption of Adaptation and Mitigation Measures | [44,46,48,54,55,58,69,75] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gkouliaveras, V.; Kalogiannidis, S.; Kalfas, D.; Papaklonari, A.; Kontsas, S. Climate Change and Health Systems: A Scoping Review of Health Professionals’ Perceptions and Readiness for Action. Climate 2026, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010012

Gkouliaveras V, Kalogiannidis S, Kalfas D, Papaklonari A, Kontsas S. Climate Change and Health Systems: A Scoping Review of Health Professionals’ Perceptions and Readiness for Action. Climate. 2026; 14(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkouliaveras, Vasileios, Stavros Kalogiannidis, Dimitrios Kalfas, Apostolia Papaklonari, and Stamatis Kontsas. 2026. "Climate Change and Health Systems: A Scoping Review of Health Professionals’ Perceptions and Readiness for Action" Climate 14, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010012

APA StyleGkouliaveras, V., Kalogiannidis, S., Kalfas, D., Papaklonari, A., & Kontsas, S. (2026). Climate Change and Health Systems: A Scoping Review of Health Professionals’ Perceptions and Readiness for Action. Climate, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli14010012