Assessing the Impact of Natural and Anthropogenic Pollution on Air Quality in the Russian Far East

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. WRF-Chem

2.2. Spatial Distribution of Gas and Aerosol Sources

3. Results and Discussion

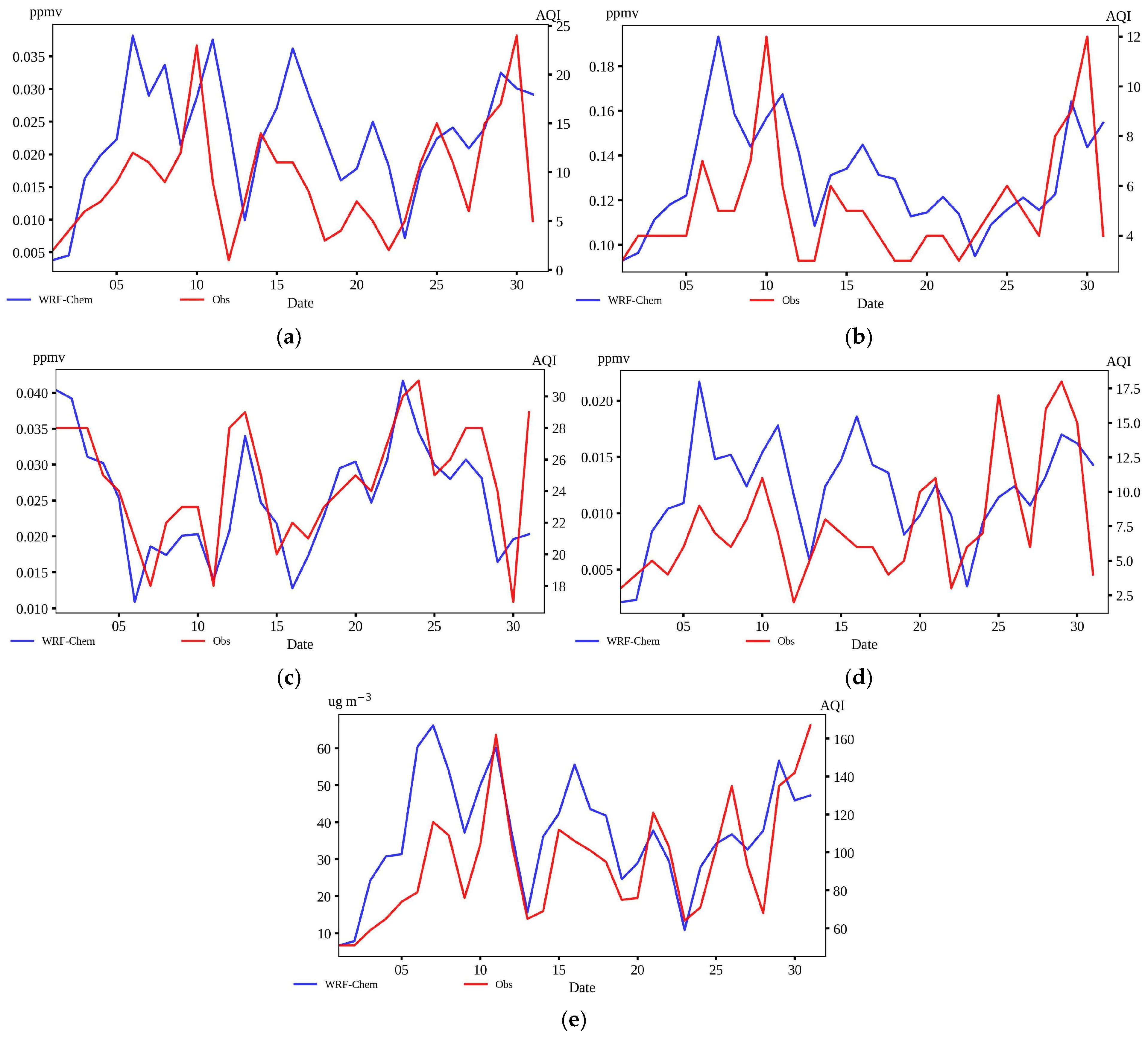

3.1. Evaluation of Model Results

Comparison with ERA5

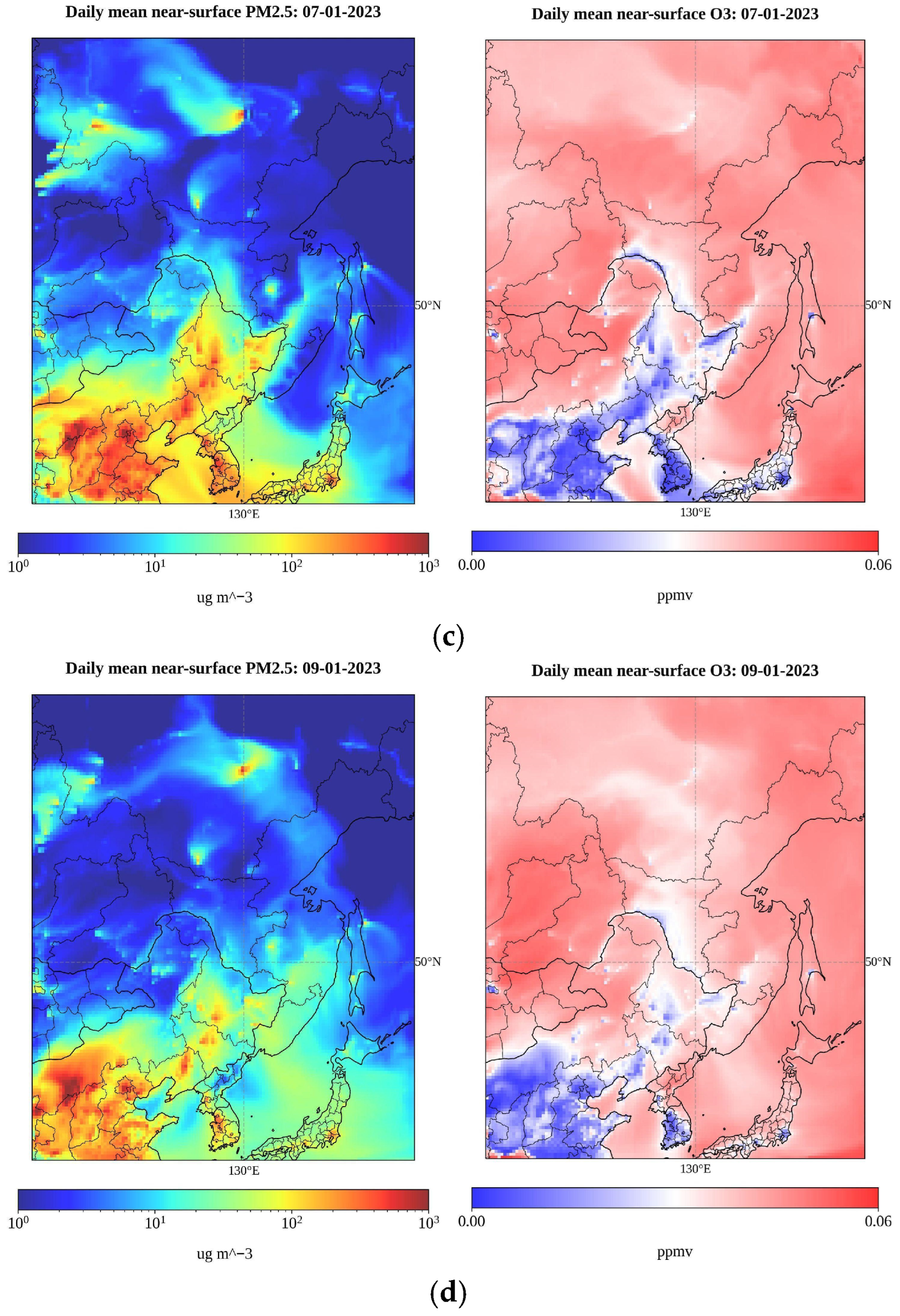

3.2. Numerical Simulation of Lower-Atmosphere Composition

- July 2015

- January 2023

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Selection of the Study Period

- Satellite data analysis

- Results of long-term analysis

- Analysis of ground-based measurements in China (Heihe station)

Appendix A.2. Synoptic Analysis

- July 2015

- January 2023

References

- Tikhonova, I.V.; Sivolapov, A.; Semerikova, S.; Semerikov, V.L.; Mashkina, O.; Isakov, I. Forest Genetic Resources of Russia: Study, Conservation, Use, Management; VNIILM: Pushkino, Russia, 2024; (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharuk, V.I.; Ponomarev, E.I.; Ivanova, G.A.; Dvinskaya, M.L.; Coogan, S.C.P.; Flannigan, M.D. Wildfires in the Siberian taiga. Ambio 2021, 50, 1953–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Pommier, A.; Héraud, A.; Chevallier, F.; Ciais, P.; Christoudias, T.; Kushta, J.; Sciare, J. Global gridded NOx emissions using TROPOMI observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 3329–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHINA: Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan. 2013. Available online: https://policy.asiapacificenergy.org/node/2875 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, L. Improving Air Quality in the People’s Republic of China: Lessons from the Greater Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. In East Asia Working Papers; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 2025; p. 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ning, M.; Lei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, J. Defending blue sky in China: Effectiveness of the “Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan” on air quality improvements from 2013 to 2017. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 252, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Guo, W.; Zhou, C.; Li, Z. The variability of NO2 concentrations over China based on satellite and influencing factors analysis during 2019–2021. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1267627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshydromet. Obzor Sostoyaniya i Zagryazneniya Okruzhayushchey Sredy v ROSSIYSKOY FEDERATSII za 2024 God; Roshydromet: Moscow, Russia, 2024. Available online: https://www.meteorf.gov.ru/product/infomaterials/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Bondur, V.G.; Gordo, K.A.; Voronova, O.S.; Zima, A.L.; Feoktistova, N.V. Intense Wildfires in Russia over a 22-Year Period According to Satellite Data. Fire 2023, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, D.I.; Burton, C.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Jones, M.W.; Barbosa, M.L.F.; Brambleby, E.; McNorton, J.R.; Liu, Z.; Bradley, A.S.I.; Blackford, K.; et al. State of Wildfires 2024–2025. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 5377–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.A. On the features of air pollution in the Russian Far East. Ojkumena. Reg. Res. 2020, 1, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat). Territorial Body of the Federal State Statistics Service for the Amur Region (Amurstat); Environmental Protection in the Amur Region. Amurstat: Blagoveshchensk, Russia, 2019. Available online: https://irbis.amursu.ru/DigitalLibrary/%D0%A1%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B0/497.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat). Territorial Body of the Federal State Statistics Service for the Amur Region (Amurstat); State Report on Environmental Protection and the Ecological Situation in the Amur Region; Amurstat: Blagoveshchensk, Russia, 2019. Available online: https://28.rosstat.gov.ru/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Chernogaeva, G.M.; Gromov, S.A.; Zhuravleva, L.R.; Malevanov, Y.A.; Peshkov, Y.V.; Kotlyakova, M.G.; Krasil’nikova, T.A.; Korshenko, A.N.; Postnov, A.A.; Krutov, A.N.; et al. Obzor Sostoyaniya i Zagryazneniya Okruzhayushchey Sredy v Rossiyskoy Federatsii za 2021 God; Roshydromet: Moscow, Russia, 2021; 220p. Available online: https://www.meteorf.gov.ru (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Chernogaeva, G.M.; Zhuravleva, L.R.; Malevanov, Y.A.; Peshkov, Y.V.; Kotlyakova, M.G.; Krasil’nikova, T.A. Obzor Sostoyaniya i Zagryazneniya Okruzhayushchey Sredy v ROSSIYSKOY Federatsii za 2023 God; Roshydromet: Moscow, Russia, 2024. Available online: https://www.meteorf.gov.ru (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Roshydromet. Obzor Sostoyaniya i Zagryazneniya Okruzhayushchey Sredy v Rossiyskoy Federatsii za 2024 God; Roshydromet: Moscow, Russia, 2025. Available online: https://www.meteorf.gov.ru (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Ministry of Natural Resources of the Amur Region. State Budgetary Institution of the Amur Region “Ecology”. State Report on Environmental Protection and the Ecological Situation in the Amur Region, 2021; Ministry of Natural Resources of the Amur Region: Blagoveshchensk, Russia, 2021; 388p.

- Thorp, T.; Arnold, S.R.; Pope, R.J.; Spracklen, D.V.; Conibear, L.; Knote, C.; Arshinov, M.; Belan, B.; Asmi, E.; Laurila, T.; et al. Late-spring and summertime tropospheric ozone and NO2 in western Siberia and the Russian Arctic: Regional model evaluation and sensitivities. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 4677–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, A.G. Dinamika lesnykh pozharov na Dal’nem Vostoke Rossii. Sib. Lesn. Zhurnal 2021, 30–38. Available online: https://sibjforsci.com/upload/iblock/88d/88dfc2634c06c688cf042cbbc2a3e2c7.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Grell, G.A.; Peckham, S.E.; Schmitz, R.; McKeen, S.A.; Frost, G.; Skamarock, W.C.; Eder, B. Fully Coupled “Online” Chemistry in the WRF Model. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 6957–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, M.J.; Delamere, J.S.; Mlawer, E.J.; Shephard, M.W.; Clough, S.A.; Collins, W.D. Radiative forcing by long–lived greenhouse gases: Calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D13103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, M.; Chen, F.; Wang, W.; Dudhia, J.; LeMone, M.A.; Mitchell, K.E.; Ek, M.B.; Gayno, G.; Wegiel, J.W.; Cuenca, R. Implementation and verification of the unified Noah land-surface model in the WRF model [presentation]. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference on Weather Analysis and Forecasting/16th Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 January 2004; Available online: https://n2t.org/ark:/85065/d7fb523p (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Jiménez, P.A.; Dudhia, J.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Montávez, J.P.; García-Bustamante, E. A Revised Scheme for the WRF Surface Layer Formulation. Mon. Weather Rev. 2012, 140, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougeault, P.; Lacarrere, P. Parameterization of Orography–Induced Turbulence in a Mesobeta––Scale Model. Mon. Weather Rev. 1989, 117, 1872–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grell, G.A.; Devenyi, D. A generalized approach to parameterizing convection combining ensemble and data assimilation techniques. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 38-1–38-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Field, P.R.; Rasmussen, R.M.; Hall, W.D. Explicit Forecasts of Winter Precipitation Using an Improved Bulk Microphysics Scheme. Part II: Implementation of a New Snow Parameterization. Mon. Weather Rev. 2008, 136, 5095–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, L.K.; Walters, S.; Hess, P.G.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Pfister, G.G.; Fillmore, D.; Granier, C.; Guenther, A.; Kinnison, D.; Laepple, T.; et al. Description and evaluation of the Model for Ozone and Related chemical Tracers, version 4 (MOZART-4). Geosci. Model Dev. 2010, 3, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.; Ginoux, P.; Kinne, S.; Torres, O.; Holben, B.N.; Duncan, B.N.; Martin, R.V.; Logan, J.A.; Higurashi, A.; Nakajima, T. Tropospheric aerosol optical thickness from the GOCART model and comparisons with satellite and Sun photometer measurements. J. Atmos. Sci. 2002, 59, 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, L.; Beirle, S.; Kumar, V.; Osipov, S.; Pozzer, A.; Bösch, T.; Kumar, R.; Wagner, T. On the influence of vertical mixing, boundary layer schemes, and temporal emission profiles on tropospheric NO2 in WRF-Chem—Comparisons to in situ, satellite, and MAX-DOAS observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 185–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, L.K.; Schwantes, R.H.; Orlando, J.J.; Tyndall, G.; Kinnison, D.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Marsh, D.; Mills, M.J.; Tilmes, S.; Bardeen, C.; et al. The Chemistry Mechanism in the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2020, 12, e2019MS001882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettelman, A.; Mills, M.J.; Kinnison, D.E.; Garcia, R.R.; Smith, A.K.; Marsh, D.R.; Tilmes, S.; Vitt, F.; Bardeen, C.G.; McInerny, J.; et al. The whole atmosphere community climate model version 6 (WACCM6). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 12380–12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens-Maenhout, G.; Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Dentener, F.; Muntean, M.; Pouliot, G.; Keating, T.; Zhang, Q.; Kurokawa, J.; Wankmüller, R.; et al. HTAP_v2.2: A mosaic of regional and global emission grid maps for 2008 and 2010 to study hemispheric transport of air pollution. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 11411–11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, A.; Karl, T.; Harley, P.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Palmer, P.I.; Geron, C. Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006, 6, 3181–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedinmyer, C.; Kimura, Y.; McDonald-Buller, E.C.; Emmons, L.K.; Buchholz, R.R.; Tang, W.; Seto, K.; Joseph, M.B.; Barsanti, K.C.; Carlton, A.G.; et al. The Fire Inventory from NCAR version 2.5: An updated global fire emissions model for climate and chemistry applications. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 3873–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERA5: Data Documentation. Available online: https://confluence.ecmwf.int/display/CKB/ERA5%3A+data+documentation (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- IFS Documentation CY41R2—Part IV: Physical Processes. Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/elibrary/79697-ifs-documentation-cy41r2-part-iv-physical-processes (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- IFS Documentation CY41R2—Part I: Observations. Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/elibrary/79695-ifs-documentation-cy41r2-part-i-observations (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Federal Service for Surveillance on Consumer Rights Protection and Human Wellbeing (Rospotrebnadzor). SanPiN 1.2.3685-21. Hygienic Standards and Requirements for Ensuring the Safety and (or) Harmlessness to Humans of Environmental Factors; Rospotrebnadzor: Moscow, Russia, 2021; p. 988p. Available online: https://www.forus-nsk.ru/o-centre/dokumenty/SP123685_21_0.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Huszar, P.; Karlický, J.; Bartík, L.; Liaskoni, M.; Prieto Perez, A.P.; Šindelářová, K. Impact of urbanization on gas-phase pollutant concentrations: A regional-scale, model-based analysis of the contributing factors. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 12647–12674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, P.F.; van den Oord, G.H.J.; Dobber, M.R.; Malkki, A.; Visser, H.; de Vries, J.; Stammes, P.; Lundell, J.O.V.; Saari, H. The Ozone Monitoring Instrument. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMI Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document Volume IV. Available online: https://docserver.gesdisc.eosdis.nasa.gov/repository/Mission/OMI/3.3_ScienceDataProductDocumentation/3.3.4_ProductGenerationAlgorithm/ATBD-OMI-04.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NASA Data Platform GES DISC. Available online: https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- IASI Data Portal. Available online: https://iasi.aeris-data.fr (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Ehret, A.; Turquety, S.; George, M.; Hadji-Lazaro, J.; Clerbaux, C. Increase in Carbon Monoxide (CO) and Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD) observed by satellite in the northern hemisphere over the summers of 2008–2023, linked to an increase in wildfires. EGUsphere 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.-P.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Wu, Y.-R.; Zhaxi, Y.; Che, H.-Z.; La, B.; Wang, W.; Li, X.-W. Spatio-temporal variation trends of satellite-based aerosol optical depth in China during 1980–2008. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 6802–6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, W.; Wang, W. Development of a finer-resolution multi-year emission inventory for open biomass burning in Heilongjiang Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Qiu, H. The trend, seasonal cycle, and sources of tropospheric NO2 over China during 1997–2006 based on satellite measurement. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2007, 50, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synoptic Maps of Roshydromet. Available online: https://disk.yandex.ru/d/8gNOnIykHu7ugg (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- NASA Worldview. NASA’s ESDIS. Available online: https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Weather Forecast Web-Service. Available online: https://rp5.ru (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Main Weather-Climate Features in the Northern Hemisphere in July 2015. Roshydromet. Available online: https://meteoinfo.ru/climate/climat-tabl3/-2015-/11440--2015- (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- State Report on the Protection of the Population and Territories of the Russian Federation from Natural and Technogenic Emergencies in 2023. Amur Center for Hydrometeorology and Environmental Monitoring (Amur CGMS). Available online: https://amurmeteo.ru/news/416-obzor-pogodnyh-uslovij-v-2023-g.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

| Parameter | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal domain and resolution | 3096 × 3768 km2, 24 km | |

| Time steps (dynamics/chemistry) | 2 and 15 min | |

| Vertical distribution | 35 hybrid levels, from the surface up to 50 hPa | |

| Initial and boundary conditions | Meteorology | ERA5 reanalysis, horizontal resolution 0.25°, up to ~80 km on 137 hybrid levels |

| Chemistry | CAM-chem and WACCM simulations, horizontal resolution 0.9 × 1.25°, up to ~45 km on 56 hybrid levels | |

| Emission sources | Anthropogenic emissions | EDGARv8.1, 0.1° resolution, monthly mean data |

| Biogenic fluxes | Online biogenic model MEGAN, ~1 km resolution | |

| Biomass burning | FINN v2.4 and v2.5, ~1 km resolution | |

| Dust and sea salt | Online dust and sea salt emission preprocessors | |

| Chemical mechanism | MOZART | |

| Aerosol dynamics scheme | GOCART | |

| Simulation periods | 15 June–31 July 2015 15 December 2022–31 January 2023 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nerobelov, G.; Urmanov, V.; Tronin, A.; Kiselev, A.; Vasiliev, M.; Sedeeva, M.; Baklanov, A. Assessing the Impact of Natural and Anthropogenic Pollution on Air Quality in the Russian Far East. Climate 2025, 13, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120252

Nerobelov G, Urmanov V, Tronin A, Kiselev A, Vasiliev M, Sedeeva M, Baklanov A. Assessing the Impact of Natural and Anthropogenic Pollution on Air Quality in the Russian Far East. Climate. 2025; 13(12):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120252

Chicago/Turabian StyleNerobelov, Georgii, Vladislav Urmanov, Andrei Tronin, Andrey Kiselev, Mihail Vasiliev, Margarita Sedeeva, and Alexander Baklanov. 2025. "Assessing the Impact of Natural and Anthropogenic Pollution on Air Quality in the Russian Far East" Climate 13, no. 12: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120252

APA StyleNerobelov, G., Urmanov, V., Tronin, A., Kiselev, A., Vasiliev, M., Sedeeva, M., & Baklanov, A. (2025). Assessing the Impact of Natural and Anthropogenic Pollution on Air Quality in the Russian Far East. Climate, 13(12), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13120252