A Model of the Impact of Government Revenue and Quality of Governance on the Pupil/Teacher Ratio for Every Country in the World

Abstract

1. Introduction

| A qualified teacher | One who has the minimum academic qualifications necessary to teach at a specific level of education in each country. This is usually related to the subject (s) they teach. |

| A trained teacher | One who has fulfilled at least the minimum organized teacher-training requirements (pre-service or in-service) to teach a specific level of education according to the relevant national policy or law. These requirements usually include pedagogical knowledge (broad principles and strategies of classroom management and organization that transcend the subject matter being taught. |

| Sustainable Development Goals | |

| Target 4.c | Aims to substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers. |

| Indicator 4. c.1 | The proportion of teachers with the minimum required qualifications, by education level. |

| Indicator 4. c.2 | The pupil-trained teacher ratio by education level. |

| Indicator 4. c.3 | The percentage of teachers qualified according to national standards by education level and type of institution. |

| Indicator 4. c.4 | The pupil-qualified teacher ratio by education level |

2. Literature Review

2.1. The History of Education Scale-Up Globally

2.2. The Benefits of Education to the Individual and Society

2.3. Quantity Versus Quality

2.4. The Supply and Demand of Educational Scale-Up

2.5. Government Revenue and Education

2.6. Governance and Education

2.7. Bottlenecks in the Supply-Side Scale-Up in Education

3. The Methods

- Understanding the link between government revenue and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is crucial, as the actions of governments and international or multinational entities—including corporations and commercial banks—are more likely to affect revenue than expenditure. For instance, tax evasion by individuals and tax avoidance by multinational corporations can significantly reduce government revenue. In contrast, most international actors—except for the International Monetary Fund (Kentikelenis, 2023)—and donors in countries heavily reliant on aid have limited influence over how governments allocate their spending (O’Hare et al., 2018).

- Government revenue represents a government’s capacity to allocate resources across all sectors. While many studies focus narrowly on specific areas of social spending—such as health or education—these are only portions of total government expenditure. Our interest lies in the broader picture, encompassing all sectors that influence progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this study, we do not estimate the direct cost of achieving a specific SDG target, such as increasing the number of teachers, which could be calculated simply by multiplying teacher salaries. Instead, we recognize that if such funds were provided to a government, they would likely be absorbed into general spending rather than directed toward that specific goal. Therefore, our approach asks a different question: how much must government revenue increase for a government to make meaningful progress toward a given SDG target? This shifts the focus from cost estimation to understanding the fiscal conditions necessary for sustainable development.

3.1. Data

3.1.1. Education Data

3.1.2. Government Revenue Data and Quality of Governance Indicators

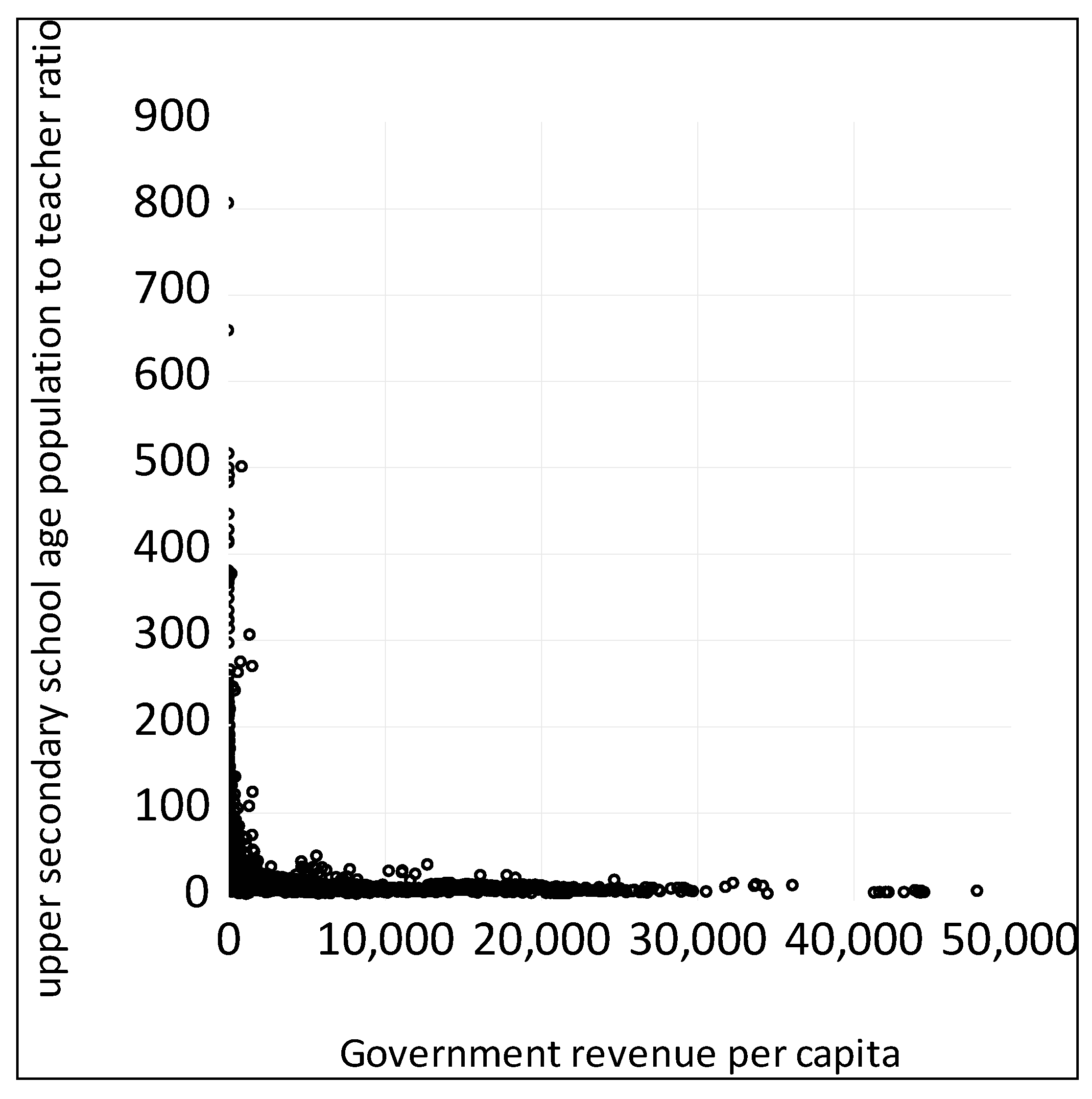

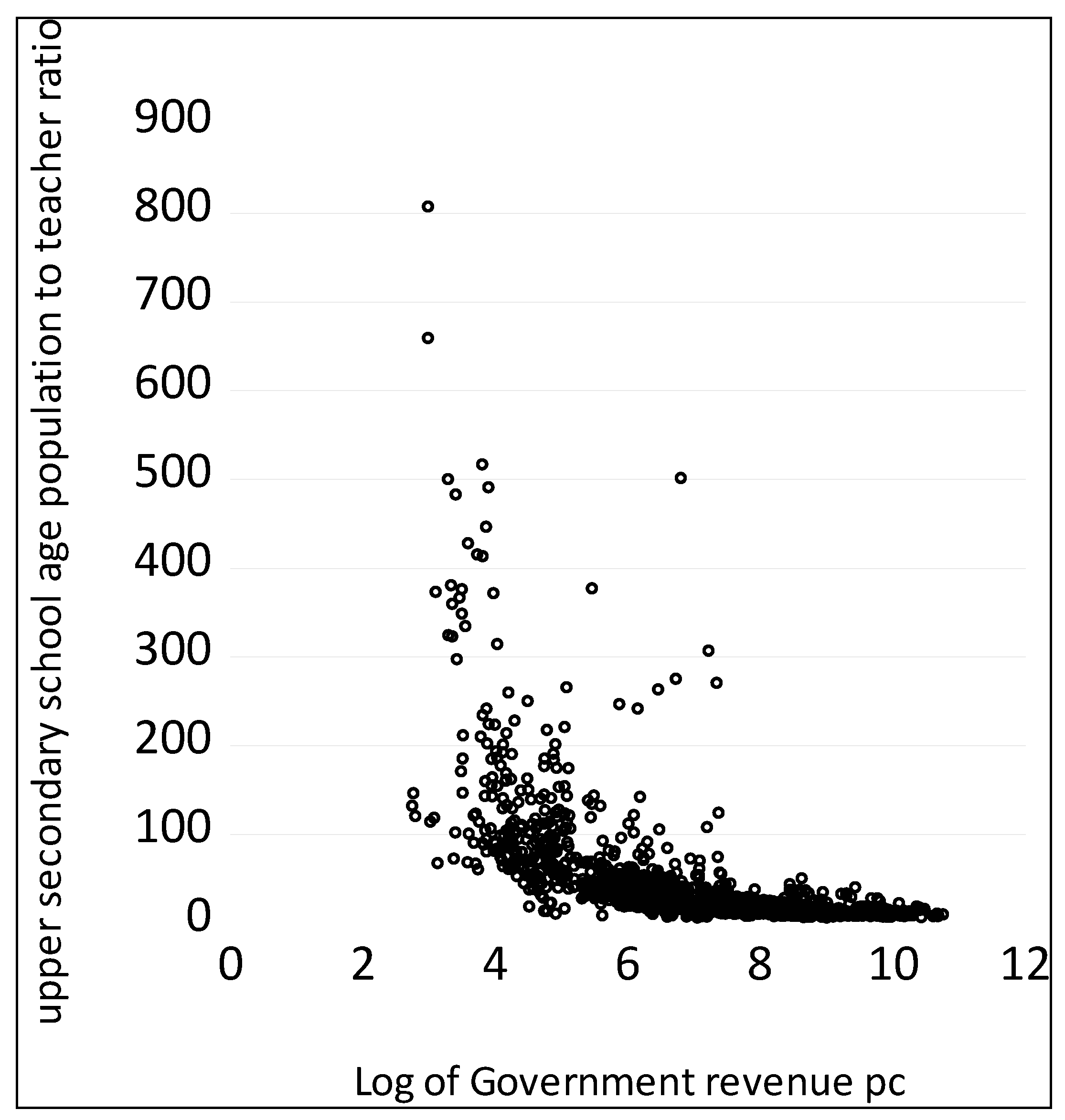

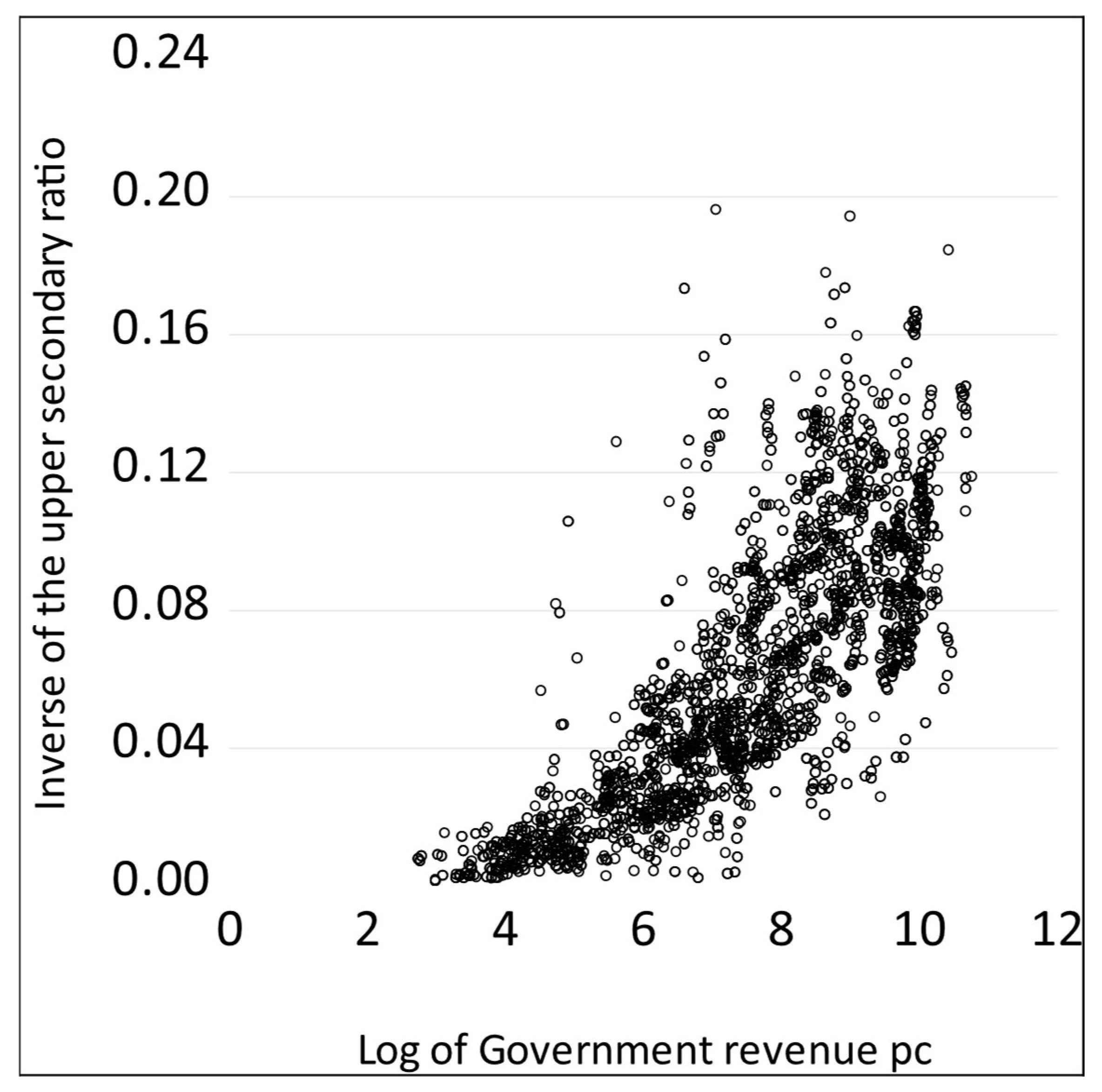

3.2. The Modelling Strategy

4. The Results

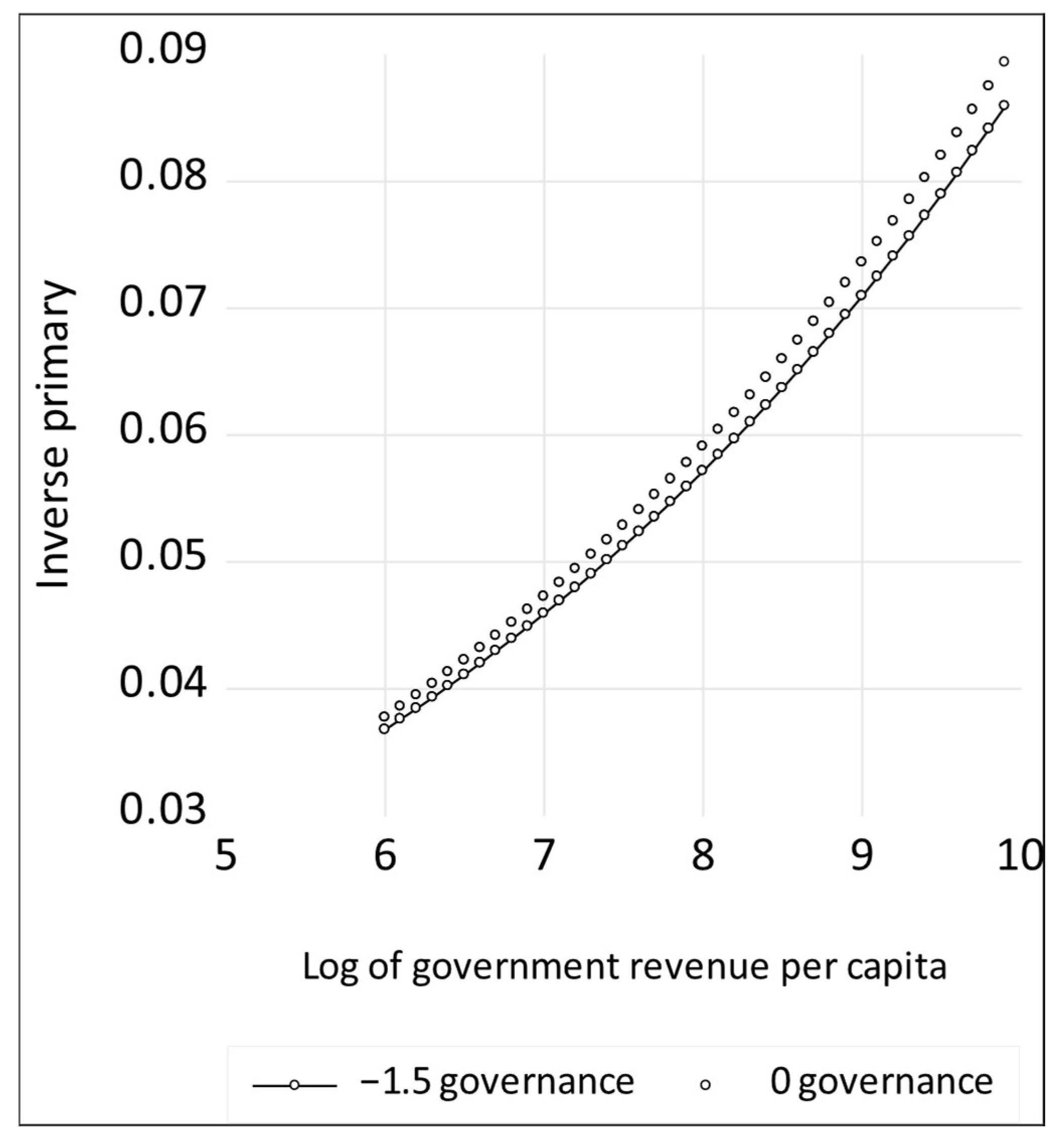

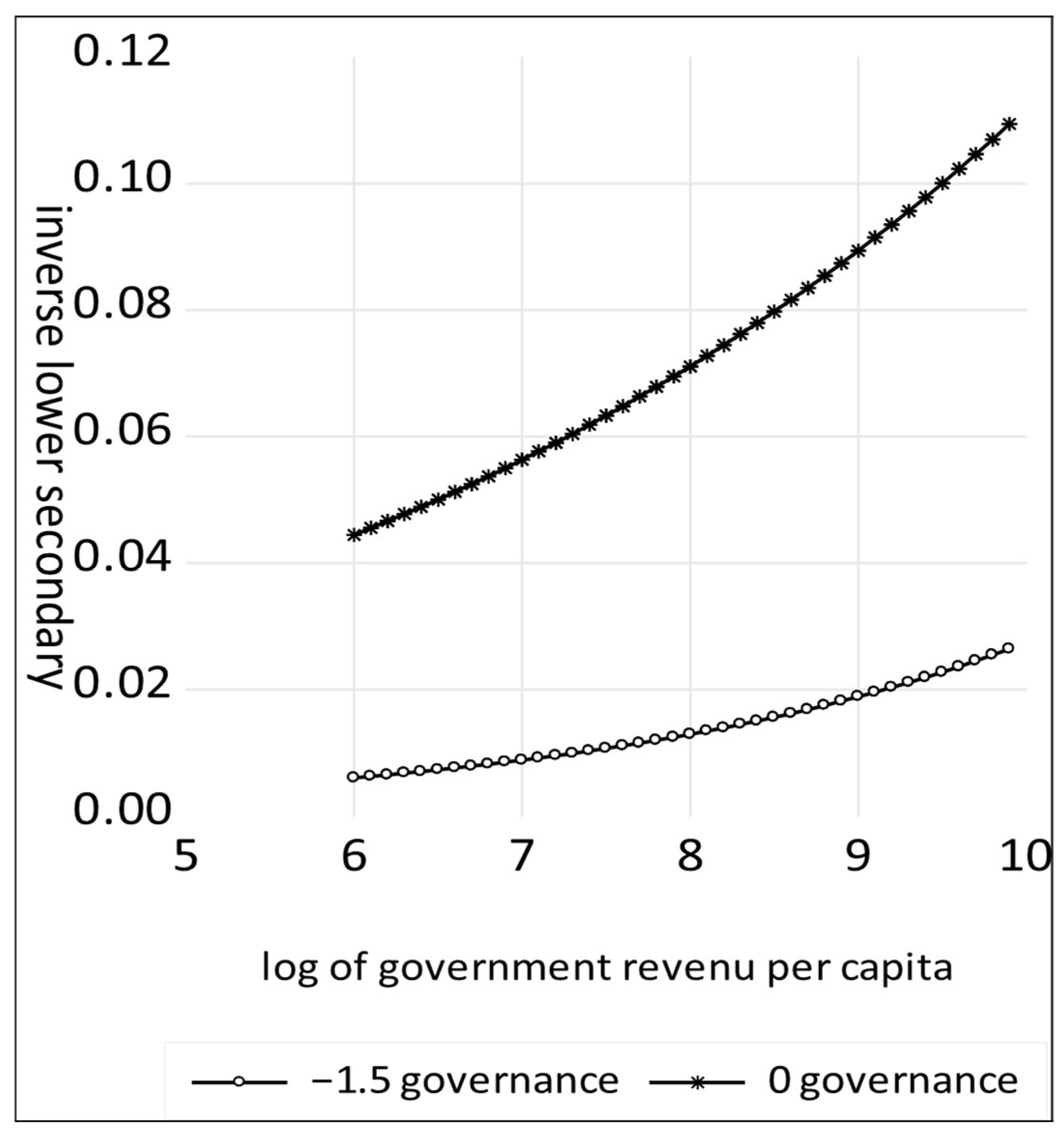

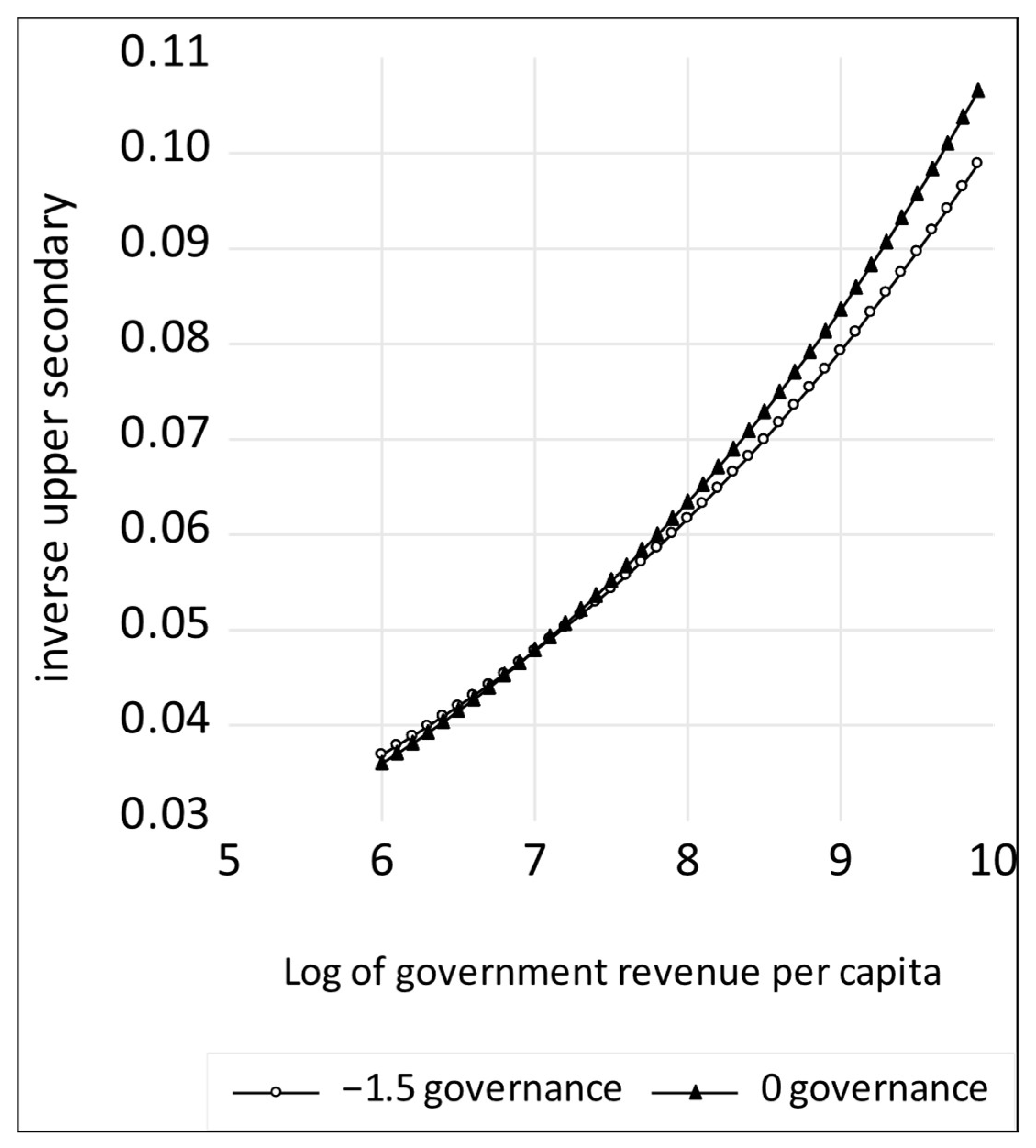

The Effect of Governance on the Shape of the Logistic Curve

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Relationship with Other Findings

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asongu, S. A., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2020). The role of governance in quality education in sub-Saharan Africa. International Social Science Journal, 70(237–238), 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteriou, D., & Hall, S. G. (2021). Applied econometrics. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Baldacci, E., Clements, B., Gupta, S., & Cui, Q. (2008). Social spending, human capital, and growth in developing countries. World Development, 36(8), 1317–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S., Lockheed, M., Ninan, E., & Tan, J.-P. (2018). Facing forward schooling for learning in Africa. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/29377 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Center for Global Development. (2022). Schooling for all: Feasible strategies to universal education. pp. 1–149. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/schooling-for-all-feasible-strategies-universal-eduction.pdf#page=86 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Chikoko, V., & Mthembu, P. (2020). Financing primary and secondary education in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of literature. South African Journal of Education, 40(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S. A., Ling Yew, S., & Ugur, M. (2015). Effects of government education and health expenditures on economic growth: A meta-analysis. Available online: https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/925653/effect_of_government_education_and_health_expenditures_on_economic_growth_a_meta-analysis.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Clemens, M. A. (2011). The long walk to school: International education goals in historical perspective. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L., & Ali, A. (2022). The case for free secondary education. In Schooling for all: Feasible strategies to achieve universal educaiton. Centre for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Dhrifi, A. (2020). Public health expenditure and child mortality: Does institutional quality matter? Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(2), 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E., & Banerjee, A. (2011). Poor economics. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. K., & Mendez Acosta, A. (2023). How to recruit teachers for hard-to-staff schools: A systematic review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Economics of Education Review, 95, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fomba, B. K., Talla, D. N. D. F., & Ningaye, P. (2022). Institutional quality and education quality in developing countries: Effects and transmission channels. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14, 86–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S., & O’Hare, B. (2023). A Model to explain the impact of government revenue on the quality of governance and the SDGs. Economies, 11(4), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halleröd, B., Rothstein, B., Daoud, A., & Nandy, S. (2013). Bad governance and poor children: A comparative analysis of government efficiency and severe child deprivation in 68 low- and middle-income countries. World Development, 48, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2021). The role of school improvement in economic development. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2020). Worldwide governance indicators. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Kentikelenis, A. (2023). A thousand cuts. pp. 1–16. Available online: https://assets.nationbuilder.com/eurodad/pages/3039/attachments/original/1664184662/Austerity_Ortiz_Cummins_FINAL_26-09.pdf?1664184662 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Kimani, M. E. (2022). Does increased government spending on additional teachers improve education quality? In The palgrave handbook of Africa’s economic sectors (pp. 1–1118). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masino, S., & Niño-Zarazúa, M. (2016). What works to improve the quality of student learning in developing countries? International Journal of Educational Development, 48, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, P. B. (2022). The routledge handbook of the economics of education. In Reference reviews (Vol. 30, Issue 4). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, C. E., & Patrinos, H. A. (2014, September). Comparable estimates of returns to schooling around the world (Policy Research Working Paper 7020). pp. 1–41. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2014/09/20173085/comparable-estimates-returns-schooling-around-world (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- O’Hare, B., & Hall, S. G. (2022). The impact of government revenue on the achievement of the sustainable development goals and the amplification potential of good governance. Central European Journal of Economic Modelling and Econometrics, 14(2), 109–129. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare, B., Mfutso Bengo, E., Devakumar, D., & Mfutso Bengo, J. (2018). Survival rights for children: What are the national and global barriers? African Human Rights Law Journal (AHRLJ), 18(2), 508–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pholphirul, P., Rukumnuaykit, P., & Teimtad, S. (2023). Teacher shortages and educational outcomes in developing countries: Empirical evidence from PISA-Thailand. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2243126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J., & Vining, A. R. (2015). Universal primary education in low-income countries: The contributing role of national governance. International Journal of Educational Development, 40(C), 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, M. (2020). Our world in data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/team/max-roser (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Taylor, S., & Spaull, N. (2013). The effects of rapidly expanding primary school access on effective learning: The case of Southern and Eastern Africa since 2000. Working Paper, 41, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations. (2022). Transforming education summit. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/transforming-education-summit/about (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- The World Bank. (2021). World development indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- UNESCO. (2021). Paris declaration: A global call for investing in the futures of education. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380116 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2022). National definitions of trained and qualified teachers: National definitions of trained and qualified teachers: Results from the metadata collection and feasibility survey. Available online: https://tcg.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2022/11/WG_T_3_Teachers_Definitions-and-global-minimum-standards-qualifications.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- United Nations. (1990). The United Nations convention on the rights of the child. Available online: http://www.unicef.org.uk/Documents/Publication-pdfs/UNCRC_PRESS200910web.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- United Nations. (2022, June). Transforming education summit thematic action thematic action track 5: Financing of education. pp. 1–22. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/search/72a71bb0-74c9-4ef5-a26b-934dd8b90ab8/N-bfc7b5bb-83c9-4eb5-b570-4933aff3f0e4 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2021). The sustainable development goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- UNU-WIDER. (2022). UNU-WIDER government revenue dataset, Version 2022; Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/project/grd-government-revenue-dataset (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Walker, J. (2023). Transforming education financing: A toolkit for activists. June. Available online: https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/27659:transforming-education-financing-a-toolkit-for-activists (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Woessmann, L. (2016). The economic case for education. Education Economics, 24(1), 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demand Side (Households) | Supply Side (Governance and Government Revenue) | |

|---|---|---|

| Household income |  | Teachers (numbers, professional development, salary, incentives, monitoring and sanctions) |

| Educated parents | Number of schools (distance) | |

| Private cost < private benefit | Removal of school fees (cash transfers, scholarships) | |

| GDP growth | Books and equipment |

| Primary School | Lower Secondary | Upper Secondary | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | SAPTR 1980–2022 | SAPTR 2010–2022 | PTTR 2010–2022 | PQTR Primary 2010–2022 | SAPTR 1980–2022 | SAPTR 2010–2022 | PTTR 2010–2022 | PQTR 2010–2022 | SAPTR 1980–2022 | SAPTR 2010–2022 | PTTR 2010–2022 | PQTR 2010–2022 |

| East Asia and Pacific | 25 | 25 | 23 | 25 | 21 | 23 | 19 | 35 | 27 | 18 | 19 | |

| Observations | 871 | 257 | 0 | 172 | 366 | 170 | 118 | 108 | 326 | 152 | 78 | 80 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 16 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 22 | 10 | 14 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Observations | 1262 | 479 | 44 | 139 | 728 | 382 | 86 | 81 | 746 | 367 | 74 | 77 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 22 | 17 | 23 | 31 | 19 | 17 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 18 | 20 | 19 |

| Observations | 988 | 312 | 50 | 165 | 407 | 185 | 126 | 104 | 394 | 183 | 119 | 100 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 27 | 21 | 16 | 19 | 23 | 21 | 16 | 17 | 26 | 20 | 15 | 13 |

| Observations | 546 | 133 | 16 | 99 | 226 | 106 | 66 | 71 | 211 | 96 | 66 | 70 |

| North America | 14 | 11 | 8 | 13 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Observations | 53 | 14 | 3 | 9 | 29 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 41 | 25 | 11 | 9 |

| South Asia | 41 | 31 | 62 | 31 | 40 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 68 | 48 | 28 | 25 |

| Observations | 202 | 81 | 2 | 41 | 146 | 81 | 55 | 43 | 112 | 72 | 37 | 35 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 56 | 40 | 55 | 46 | 91 | 64 | 47 | 33 | 125 | 83 | 38 | 26 |

| Observations | 1408 | 401 | 30 | 248 | 336 | 164 | 94 | 84 | 271 | 151 | 78 | 70 |

| 1/Lower Secondary | 1/Upper Secondary | 1/Primary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 (32.6) | 0.3 (37.1) | 0.23 (62.2) | ||

| Control of corruption | - | 0.04 (3.6) | - | |

| Government effectiveness | 0.02 (6.2) | −0.02 (2.0) | - | |

| Political stability | - | 0.009 (4.6) | −0.009 (2.2) | |

| Regulatory quality | −0.4 (6.8) | - | - | |

| Rule of law | −0.2 (5.1) | −0.08 (7.3) | 0.03 (8.5) | |

| Voice and accountability | 0.05 (10.3) | 0.07 (11.7) | −0.02 (5.6) | |

| 18.3 (61.0) | 17.0 (75.1) | 19.8 (107.0) | ||

| Control of corruption | −0.5 (3.6) | −1.2 (3.8) | - | |

| Government effectiveness | - | 0.85 (3.2) | 0.4 (5.0) | |

| Political stability | 0.38 (4.8) | −3922.0 (3.7) | 0.7 (3.6) | |

| Regulatory quality | 1.7 (8.9) | - | −0.5 (6.1) | |

| Rule of law | - | 1.7 (5.5) | −2.0 (9.8) | |

| Voice and accountability | −2.3 (9.1) | −2.0 (9.0) | −1.1 (6.6) | |

| R2 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.71 |

| 1/Lower Secondary | 1/Upper Secondary | 1/Primary | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.009 (4.6) | 0.001 (5.9) | 0.0006 (6.8) | |

| −0.05 (6.7) | −0.021 (2.4) | −0.03 (4.8) | |

| - | −0.05 (2.4) | - | |

| R2 | 0.967 | 0.976 | 0.982 |

| DW | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hall, S.G.; O’Hare, B. A Model of the Impact of Government Revenue and Quality of Governance on the Pupil/Teacher Ratio for Every Country in the World. Econometrics 2025, 13, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics13040046

Hall SG, O’Hare B. A Model of the Impact of Government Revenue and Quality of Governance on the Pupil/Teacher Ratio for Every Country in the World. Econometrics. 2025; 13(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics13040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleHall, Stephen G., and Bernadette O’Hare. 2025. "A Model of the Impact of Government Revenue and Quality of Governance on the Pupil/Teacher Ratio for Every Country in the World" Econometrics 13, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics13040046

APA StyleHall, S. G., & O’Hare, B. (2025). A Model of the Impact of Government Revenue and Quality of Governance on the Pupil/Teacher Ratio for Every Country in the World. Econometrics, 13(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/econometrics13040046