Saline–Alkaline Stress-Driven Rhizobacterial Community Restructuring and Alleviation of Stress by Indigenous PGPR in Alfalfa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

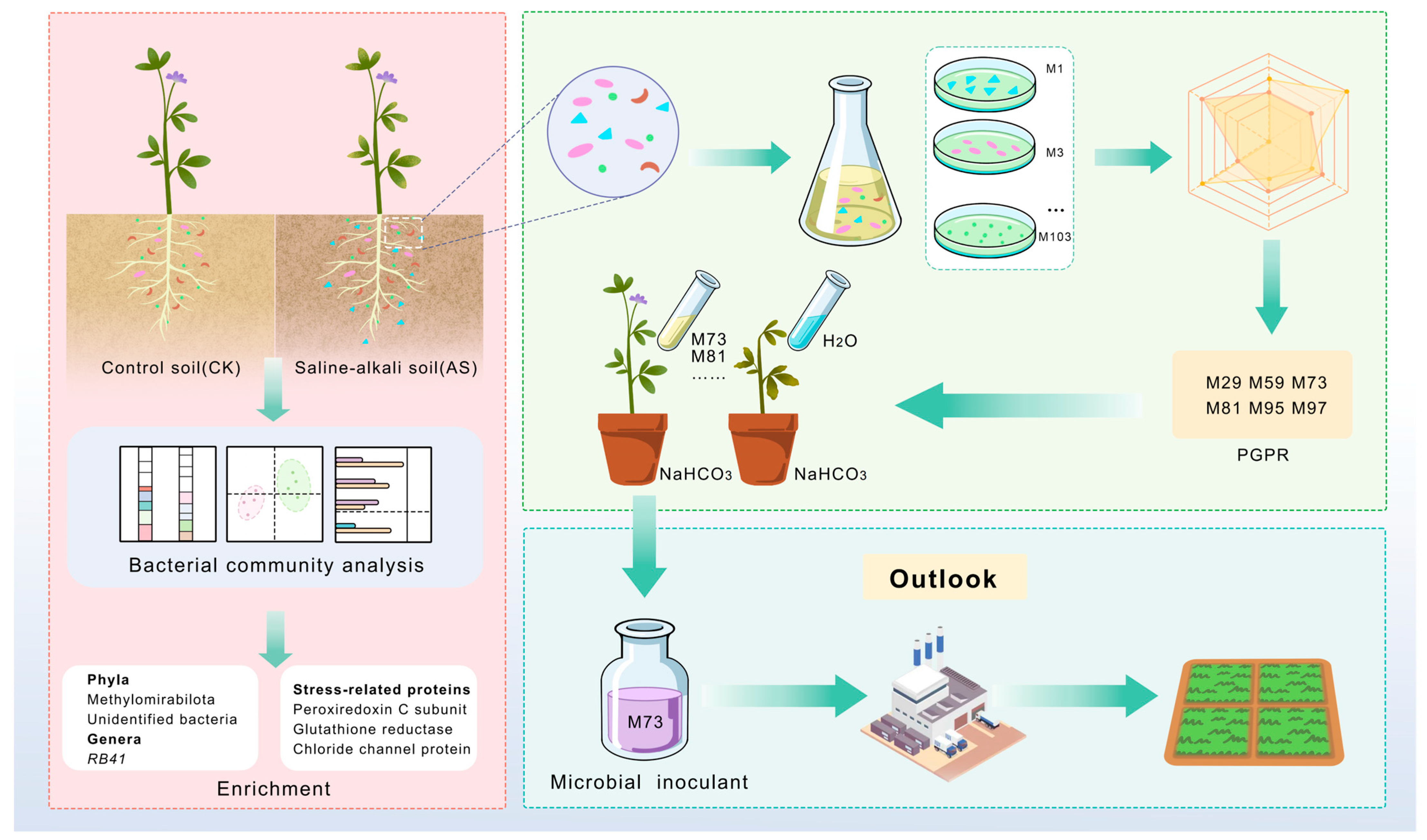

2.1. Experimental Design and Overview

2.2. Soil Physicochemical Properties

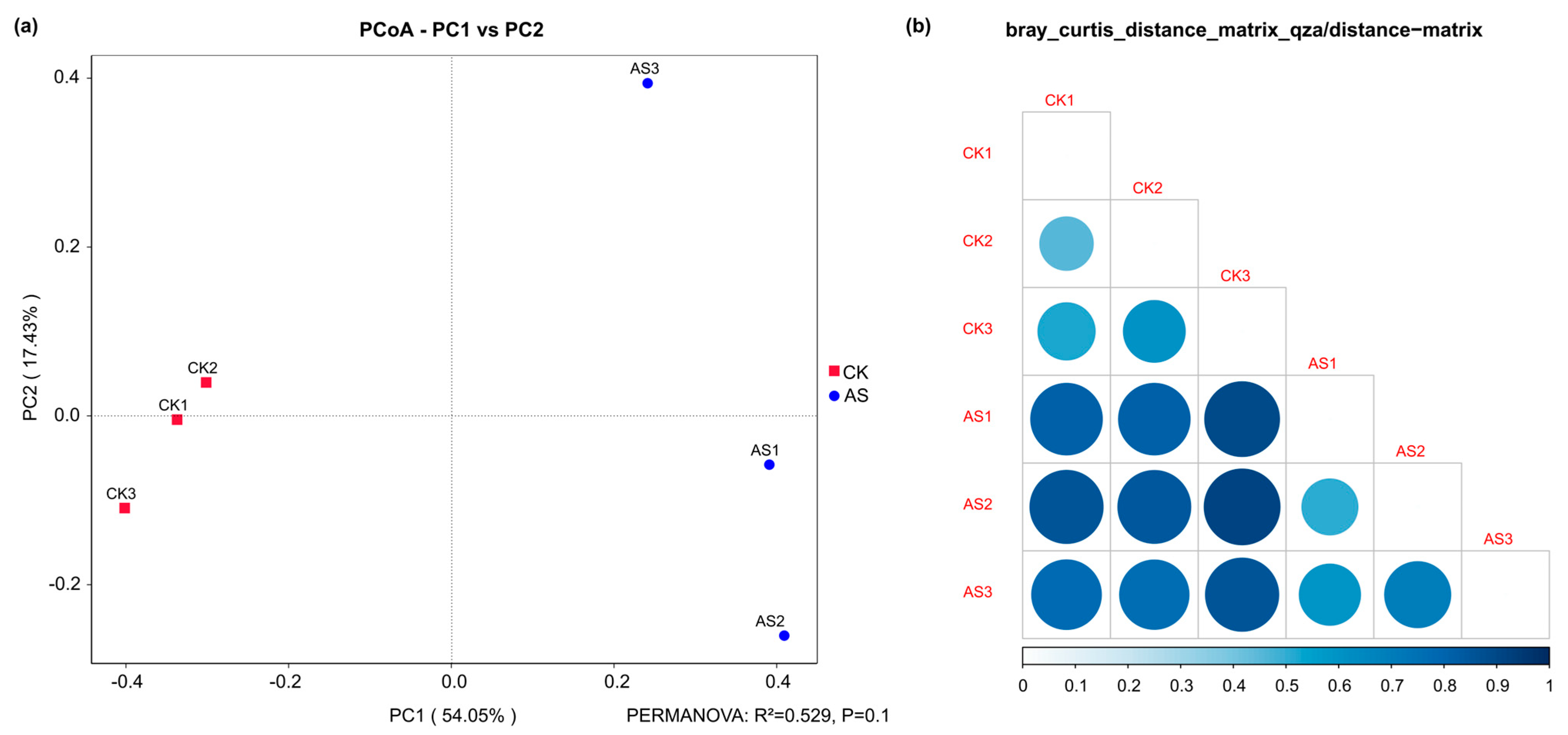

2.3. Changes in the Microbial Community Composition and Structure of the Alfalfa Rhizosphere Under Saline–Alkaline Conditions

2.4. Analysis of Microbial Diversity in the Alfalfa Rhizosphere Soil Under Saline–Alkaline Conditions

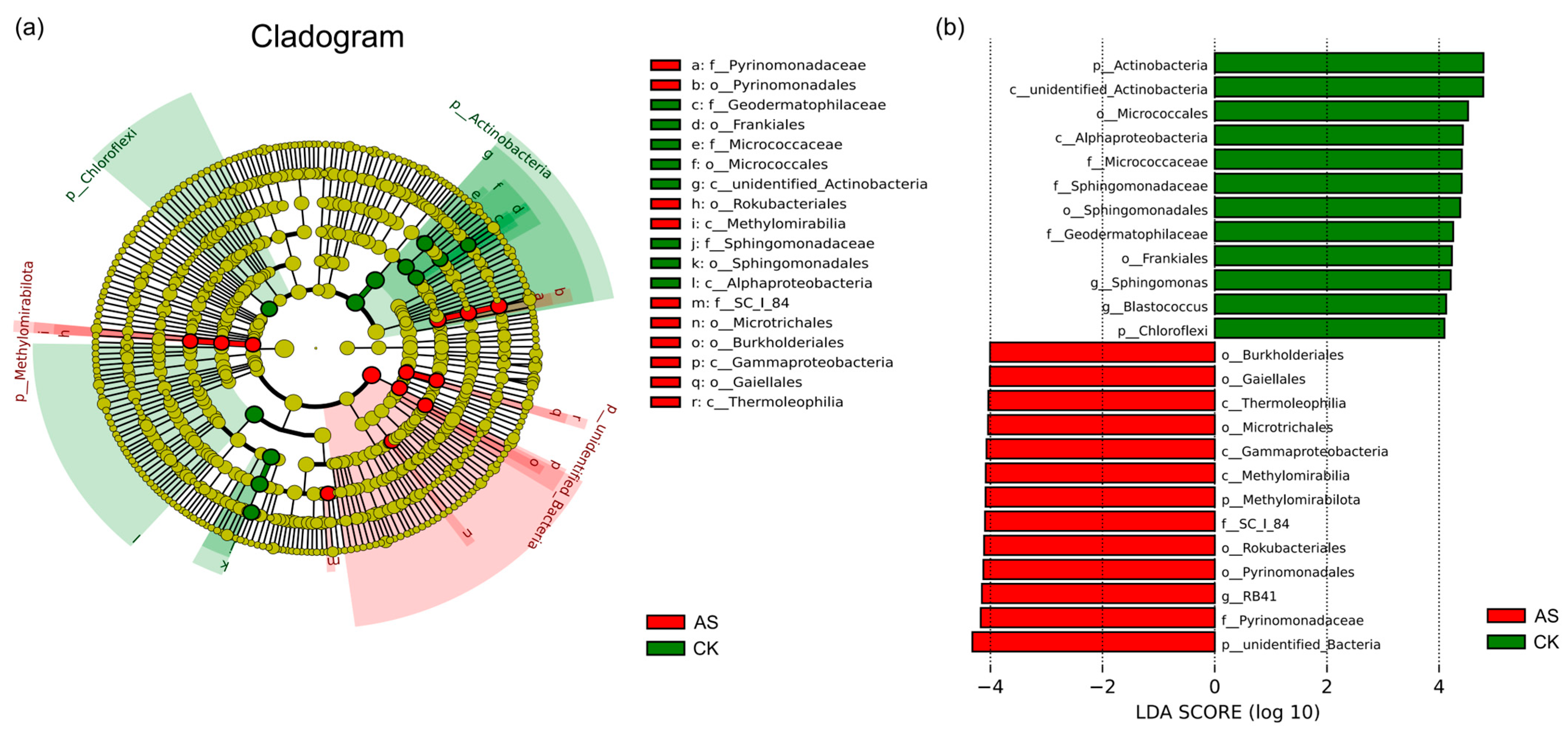

2.5. Differentially Abundant Microbial Taxa Under Saline–Alkaline Conditions

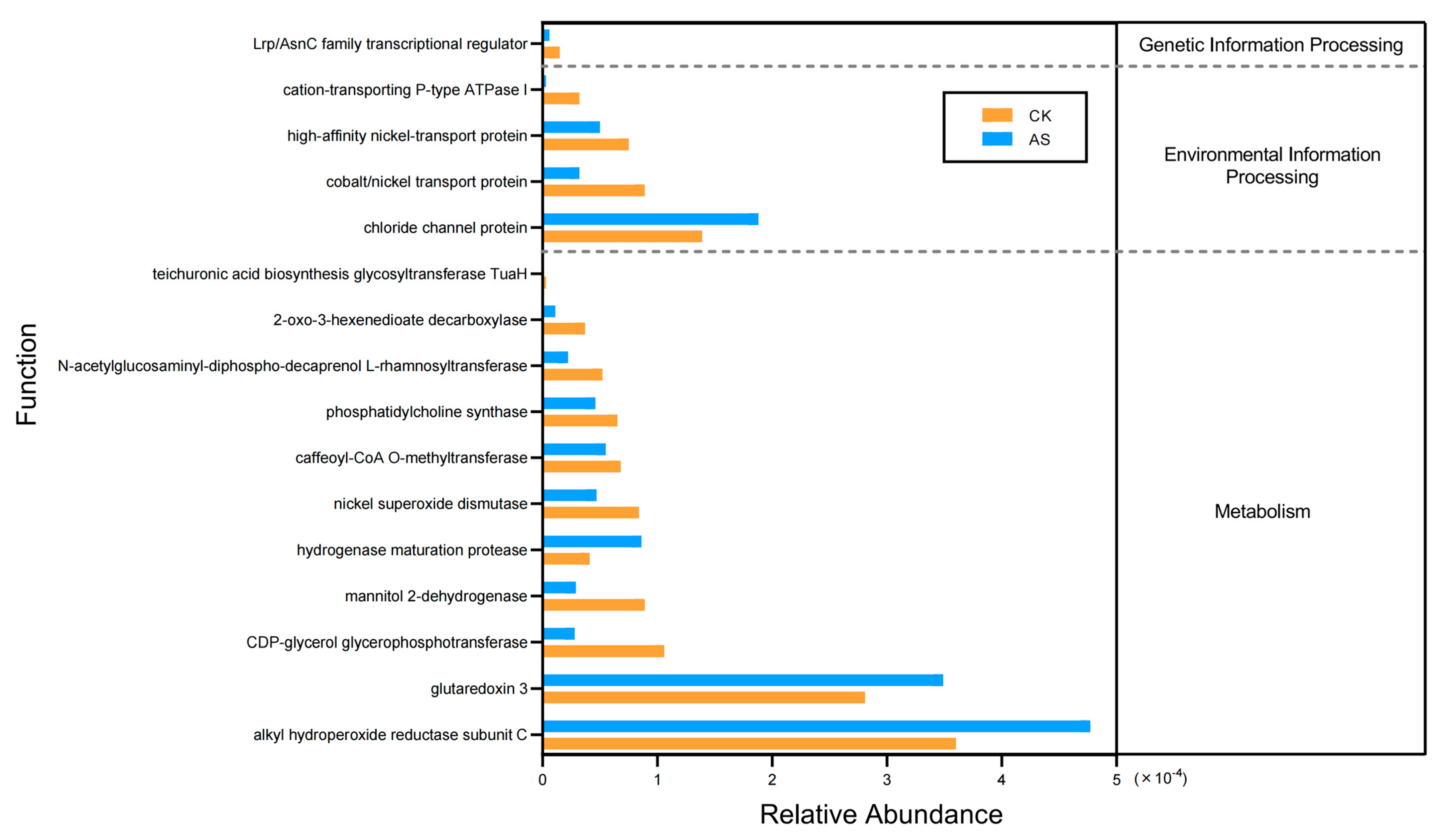

2.6. Predicted Functions of Soil Bacteria

2.7. Isolation and Phylogenetic Analysis of Culturable Microbes

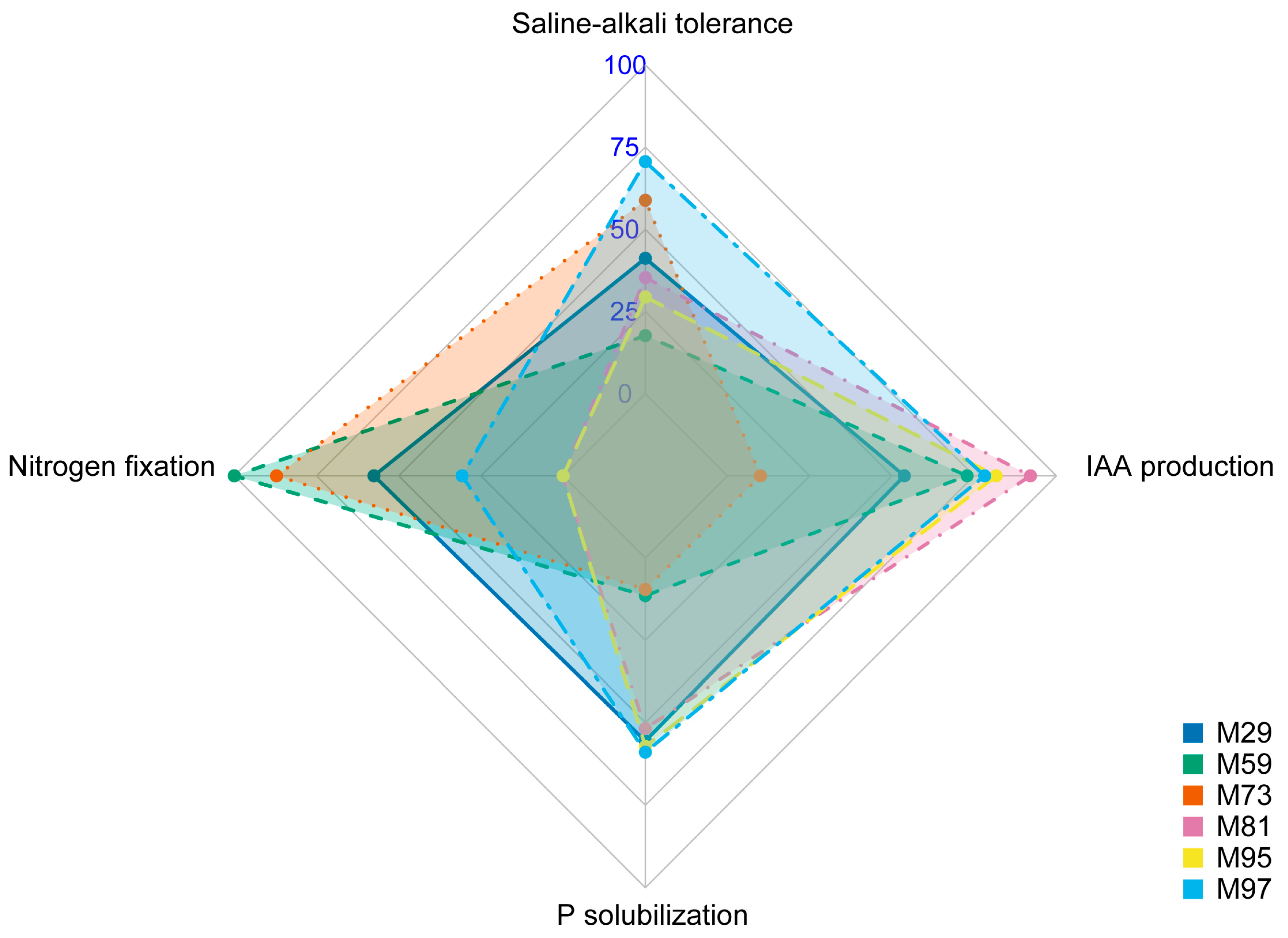

2.8. In Vitro Screening of PGP Traits

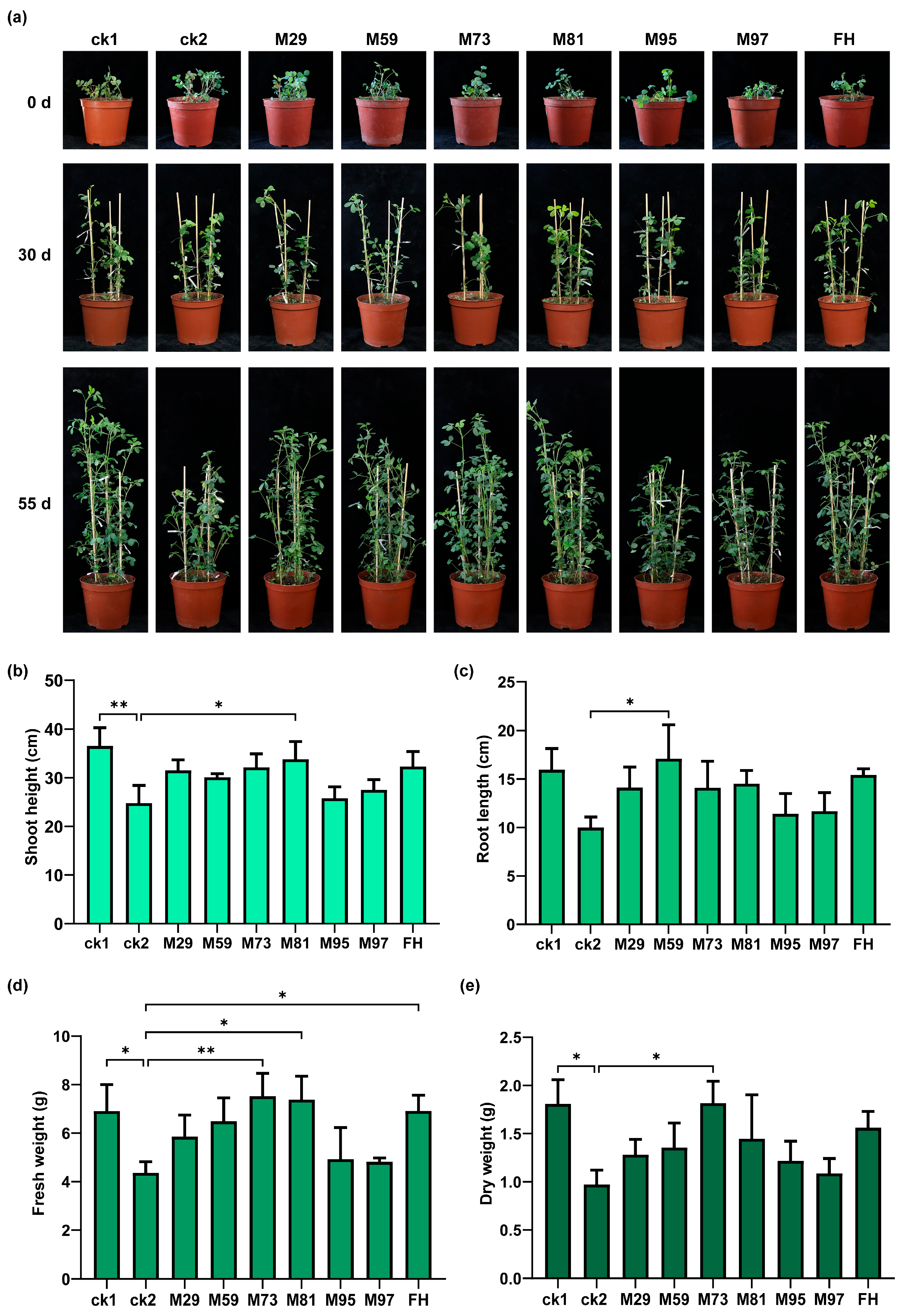

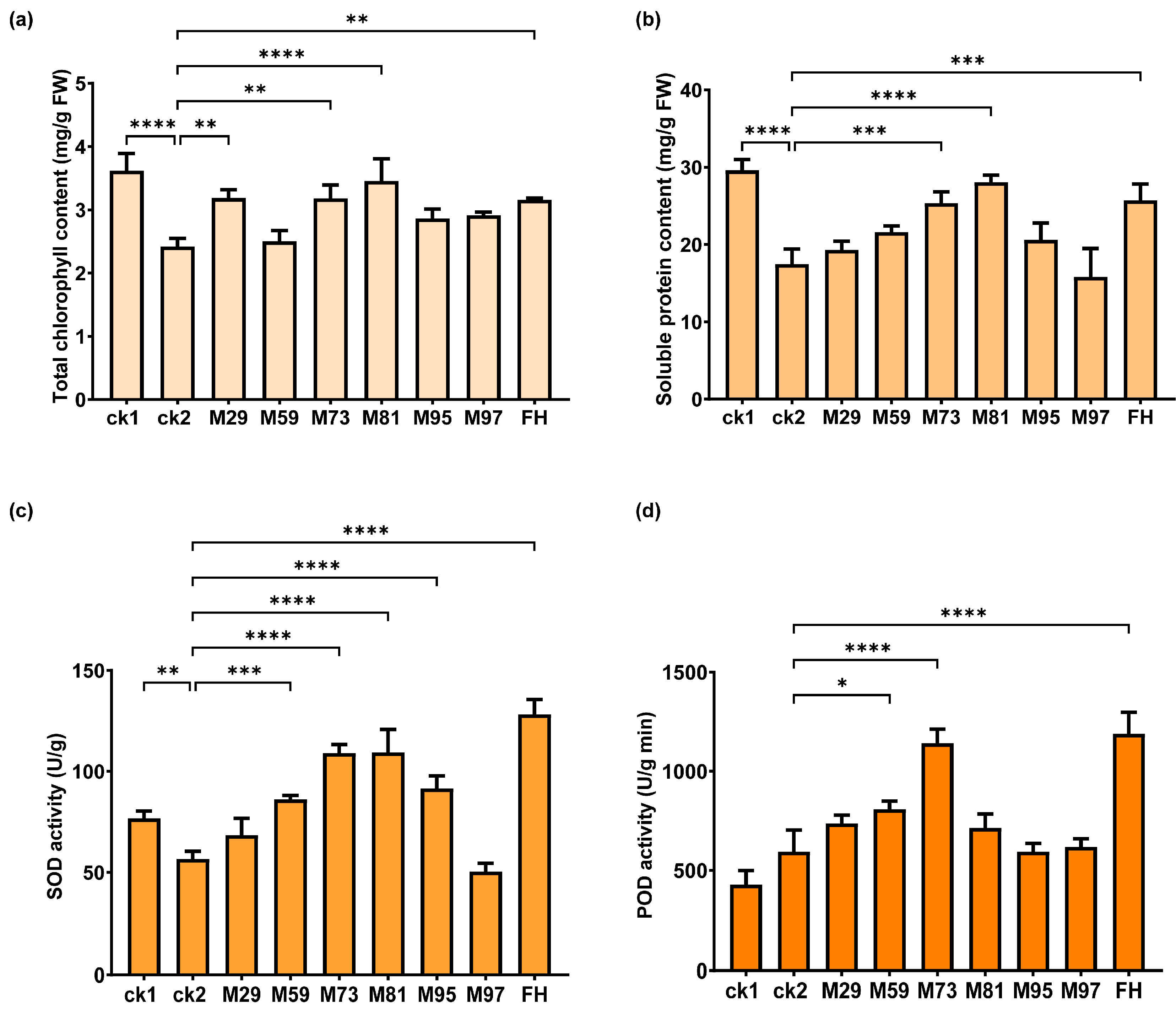

2.9. Plant Growth-Promoting Effects of Selected Strains in Pot Experiments

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Soil Sampling and Site Description

4.2. Soil Physicochemical Analysis

4.3. 16. S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

4.4. Bacterial Isolation and Identification

4.5. Functional Characterization of Bacterial Strains

4.6. Screening of PGPR Strains and Pot Experiments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGPR | Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| AS | Saline–alkaline soil |

| CK | Control soil |

| PGP | Plant growth-promoting |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TP | Total phosphorus |

| TK | Total potassium |

| AN | Available nitrogen |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| AK | Available potassium |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| LEfSe | Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size |

| PCoA | Principal Co-ordinates Analysis |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| OTUs | Operational taxonomic units |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| R2A | Reasoner’s 2A agar |

| TSA | Tryptic Soy Agar |

| LB | Lysogeny Broth |

| ASVs | Amplicon Sequence Variants |

References

- FAO. Global Status of Salt-Affected Soils—Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Hou, X.; Liang, X. Response mechanisms of plants under saline-alkali stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Kota, S.; Flowers, T.J. Salt tolerance in rice: Seedling and reproductive stage QTL mapping come of age. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 3495–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Bi, Z.; Jiang, J.; Lu, J.; Li, K.; Bai, D.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Zhao, X.; et al. Genome-wide association and epistasis studies reveal the genetic basis of saline-alkali tolerance at the germination stage in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14., 1170641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Qiao, J.; Quan, R.; Wang, J.; Huang, R.; Qin, H. SALT AND ABA RESPONSE ERF1 improves seed germination and salt tolerance by repressing ABA signaling in rice. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1110–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Liang, X.; Zhao, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Qin, F.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, C. Cytokinin signaling promotes salt tolerance by modulating shoot chloride exclusion in maize. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1031–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liang, X.; Li, F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Jiang, C. Natural variation of an EF-hand Ca2+-binding-protein coding gene confers saline-alkaline tolerance in maize. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Feng, G.; Hou, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Luo, B.; Chen, L. Nondestructive detection of saline-alkali stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings via fusion technology. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, X.; Guo, J. Physiological and transcriptomic analyses of yellow horn (Xanthoceras sorbifolia) provide important insights into salt and saline-alkali stress tolerance. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ding, H.; Huang, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhan, S.; Ma, M. Effects of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Zobellella sp. DQSA1 on alleviating salt-alkali stress in job’s tears seedings and its growth-promoting mechanism. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Tisarum, R.; Kohli, R.K.; Batish, D.R.; Cha-um, S.; Singh, H.P. Inroads into saline-alkaline stress response in plants: Unravelling morphological, physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms. Planta 2024, 259, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, L. New Insight into Plant Saline-Alkali Tolerance Mechanisms and Application to Breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Yuan, F.; Guo, J.; Han, G.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, B. Current Understanding of Role of Vesicular Transport in Salt Secretion by Salt Glands in Recretohalophytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, B. Protection of Halophytes and Their Uses for Cultivation of Saline-Alkali Soil in China. Biology 2021, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Ma, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, W.; Liu, B. Responses of growth and photosynthesis to alkaline stress in three willow species. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Du, H.; Chen, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhu, F.; Chen, H.; Meng, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, P.; Zheng, L.; et al. The Chromosome-Level Genome Sequence of the Autotetraploid Alfalfa and Resequencing of Core Germplasms Provide Genomic Resources for Alfalfa Research. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaundal, R.; Duhan, N.; Acharya, B.R.; Pudussery, M.V.; Ferreira, J.F.S.; Suarez, D.L.; Sandhu, D. Transcriptional profiling of two contrasting genotypes uncovers molecular mechanisms underlying salt tolerance in alfalfa. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolabu, T.W.; Cong, L.; Park, J.-J.; Bao, Q.; Chen, M.; Sun, J.; Xu, B.; Ge, Y.; Chai, M.; Liu, Z.; et al. Development of a highly efficient multiplex genome editing system in outcrossing tetraploid alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Deng, Y.; Inubushi, K.; Liang, J.; Zhu, S.; Wei, Z.; Guo, X.; Luo, X. Sludge Biochar Amendment and Alfalfa Revegetation Improve Soil Physicochemical Properties and Increase Diversity of Soil Microbes in Soils from a Rare Earth Element Mining Wasteland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Zhang, N.; Wei, Q.; Cao, Y.; Li, D.; Cui, G. Alfalfa modified the effects of degraded black soil cultivated land on the soil microbial community. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 938187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Duan, X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, H.; Fu, T.; Chu, H.; Xue, S. Carbon sequestration potential and its main drivers in soils under alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Song, W.; Li, L.; Zhao, J.; Pang, Q. Salt-alkali-tolerant growth-promoting Streptomyces sp. Jrh8-9 enhances alfalfa growth and resilience under saline-alkali stress through integrated modulation of photosynthesis, antioxidant defense, and hormone signaling. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 296, 128158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Ji, J.; Zhao, W.; Guo, W.; Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Wang, D.; Yan, Z.; Guo, C. Flavonol synthase gene MsFLS13 regulates saline-alkali stress tolerance in alfalfa. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1218–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-S.; Ren, H.-L.; Wei, Z.-W.; Wang, Y.-W.; Ren, W.-B. Effects of neutral salt and alkali on ion distributions in the roots, shoots, and leaves of two alfalfa cultivars with differing degrees of salt tolerance. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Ren, Y.; Guo, R.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Chai, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, C. MsMIOX2, encoding a MsbZIP53-activated myo-inositol oxygenase, enhances saline–alkali stress tolerance by regulating cell wall pectin and hemicellulose biosynthesis in alfalfa. Plant J. 2024, 120, 998–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.A.; Lennon, J.T. Rapid responses of soil microorganisms improve plant fitness in novel environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14058–14062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eroğlu, Ç.G.; Cabral, C.; Ravnskov, S.; Bak Topbjerg, H.; Wollenweber, B. Arbuscular mycorrhiza influences carbon-use efficiency and grain yield of wheat grown under pre- and post-anthesis salinity stress. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, S.; Van Geel, M.; Yeasmin, T.; Verbruggen, E.; Honnay, O. Effects of single and multiple species inocula of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the salinity tolerance of a Bangladeshi rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivar. Mycorrhiza 2020, 30, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Wang, X.; Saleem, M.H.; Sumaira; Hafeez, A.; Afridi, M.S.; Khan, S.; Zaib-Un-Nisa; Ullah, I.; Amaral Júnior, A.T.d.; et al. PGPR-Mediated Salt Tolerance in Maize by Modulating Plant Physiology, Antioxidant Defense, Compatible Solutes Accumulation and Bio-Surfactant Producing Genes. Plants 2022, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Iqbal, A.; Ahmed, F.; Ahmad, M. Phytobeneficial and salt stress mitigating efficacy of IAA producing salt tolerant strains in Gossypium hirsutum. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5317–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.X.; Urón, P.; Glick, B.R.; Giachini, A.; Rossi, M.J. Genomic Analysis of the 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate Deaminase-Producing Pseudomonas thivervalensis SC5 Reveals Its Multifaceted Roles in Soil and in Beneficial Interactions with Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 752288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Arora, N.K. Pseudomonas entomophila PE3 and its exopolysaccharides as biostimulants for enhancing growth, yield and tolerance responses of sunflower under saline conditions. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 244, 126671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, P.; Pan, H.; Boak, E.N.; Pierson, L.S.; Pierson, E.A. Phenazine-producing rhizobacteria promote plant growth and reduce redox and osmotic stress in wheat seedlings under saline conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 575314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; He, W.; Li, Z.; Ge, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, T. Salt-tolerant endophytic bacterium Enterobacter ludwigii B30 enhance bermudagrass growth under salt stress by modulating plant physiology and changing rhizosphere and root bacterial community. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 959427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Leng, J.; Niu, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Gao, N.; Ying, H. Isolation and characterization of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and their effects on the growth of Medicago sativa L. under salinity conditions. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Xiao, Y.; Dong, J.; Xing, J.; Tang, F.; Shi, F. Variety-driven rhizosphere microbiome bestows differential salt tolerance to alfalfa for coping with salinity stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1324333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliere, J.M.; Wong, W.S.; Nevill, P.G.; Zhong, H.; Dixon, K.W. Preparing for the worst: Utilizing stress-tolerant soil microbial communities to aid ecological restoration in the Anthropocene. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2020, 1, e12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xun, W.; Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R. Rhizosphere microbes enhance plant salt tolerance: Toward crop production in saline soil. Comput. Struct. Biotec 2022, 20, 6543–6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Gaurav, A.K.; Srivastava, S.; Verma, J.P. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria: Biological Tools for the Mitigation of Salinity Stress in Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, M.; Haro, R.; Conchillo, L.B.; Benito, B. The endophyte Serendipita indica reduces the sodium content of Arabidopsis plants exposed to salt stress: Fungal ENA ATPases are expressed and regulated at high pH and during plant co-cultivation in salinity. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 3364–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Waqas, M.; Asaf, S.; Kamran, M.; Shahzad, R.; Bilal, S.; Khan, M.A.; Kang, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-H.; Yun, B.-W.; et al. Plant growth-promoting endophyte Sphingomonas sp. LK11 alleviates salinity stress in Solanum pimpinellifolium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 133, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M.; Ma, Y. Metal tolerance mechanisms in plants and microbe-mediated bioremediation. Environ. Res. 2023, 222, 115413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; La, S.; Zhang, X.; Gao, L.; Tian, Y. Salt-induced recruitment of specific root-associated bacterial consortium capable of enhancing plant adaptability to salt stress. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2865–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, N.H.; Hamzah, A.; Tangahu, B.V.; Warmadewanti, I.; Bachtiar Krishna Putra, A.; Purnomo, A.S.; Danilyan, E.; Putri, H.M.; Aqila, C.N.; Dewi, A.A.N.; et al. Microbiome profile of soil and rhizosphere plants growing in traditional oil mining land in Wonocolo, Bojonegoro, Indonesia. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2023, 25, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsodi, A.K.; Mucsi, M.; Krett, G.; Szabó, A.; Felföldi, T.; Szili-Kovács, T. Variation in Sodic Soil Bacterial Communities Associated with Different Alkali Vegetation Types. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, L.; Bacci, G.; Pinzari, F.; Lo Papa, G.; Dazzi, C.; Benedetti, A. Salinity and Bacterial Diversity: To What Extent Does the Concentration of Salt Affect the Bacterial Community in a Saline Soil? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Gong, J. A meta-analysis of the publicly available bacterial and archaeal sequence diversity in saline soils. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 2325–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Y.; Wu, X.; Ni, H.; Lu, Q.; Zang, S. Long-term surface composts application enhances saline-alkali soil carbon sequestration and increases bacterial community stability and complexity. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Ning, Z.; Li, M.; Qin, X.; Yue, X.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.; Sun, H.; Huang, Y. Microbial network-driven remediation of saline-alkali soils by salt-tolerant plants. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1565399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Cui, N.; Lu, X.; Mo, S.; Guo, Q.; Ma, P. Effect of PGPRs on the Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure and Yield of Silage Maize in Saline–Alkaline Fields. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Tóth, T.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z. Effects of different types of vegetation cover on soil microorganisms and humus characteristics of soda-saline land in the Songnen Plain. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1163444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-X.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Hou, Z.-A.; Min, W. Effects of Cotton Stalk Returning on Soil Enzyme Activity and Bacterial Community Structure Diversity in Cotton Field with Long-term Saline Water Irrigation. Environ. Sci. 2022, 43, 2192–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Sha, A.; Ren, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, Q. The impact of kaolin mining activities on bacterial diversity and community structure in the rhizosphere soil of three local plants. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1424687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Q.; Bao, Z.; Tu, W.; Li, L.; Zhao, C. The effect of phosphate mining activities on rhizosphere bacterial communities of surrounding vegetables and crops. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Chen, S.; Yu, X.; Chen, S.; Wan, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, Q. Three local plants adapt to ecological restoration of abandoned lead-zinc mines through assembly of rhizosphere bacterial communities. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1533965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Xie, T.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Yin, D.; Zhang, W. Genome-wide identification of key genes related to chloride ion (Cl−) channels and transporters in response to salt stress in birch. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.T.; Zamski, E.; Williamson, J.D.; Conkling, M.A.; Pharr, D.M. Subcellular Localization of Celery Mannitol Dehydrogenase (A Cytosolic Metabolic Enzyme in Nuclei). Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuan, N.H.; Lam, B.D.; Trung, N.T. Rhamnosyltransferases: Biochemical activities, potential biotechnology for production of natural products and their applications. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2025, 189, 110656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.; Sun, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Niu, Y. Bacillus halophilus BH-8 Combined with Coal Gangue as a Composite Microbial Agent for the Rehabilitation of Saline-Alkali Land. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoso, M.A.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, G.; Ko, S.N.; Pang, Q.; Liu, C.; et al. Bacillus altitudinis AD13−4 Enhances Saline–Alkali Stress Tolerance of Alfalfa and Affects Composition of Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Community. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buqori, D.M.A.I.; Sugiharto, B.; Suherman; Siswoyo, T.A.; Hariyono, K. Mitigating drought stress by application of drought-tolerant Bacillus spp. enhanced root architecture, growth, antioxidant and photosynthetic genes expression in sugarcane. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Pandey, R.; Chauhan, N.S. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia promotes wheat growth by enhancing nutrient assimilation and rhizosphere microbiota modulation. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2025, 13, 1563670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, F.; Hossain, M.M. Assessing the potentials of bacterial antagonists for plant growth promotion, nutrient acquisition, and biological control of Southern blight disease in tomato. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzma, M.; Iqbal, A.; Hasnain, S. Drought tolerance induction and growth promotion by indole acetic acid producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Vigna radiata. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, S.S.; Cappellari, L.d.R.; Giordano, W.; Banchio, E. Antifungal Activity and Alleviation of Salt Stress by Volatile Organic Compounds of Native Pseudomonas Obtained from Mentha piperita. Plants 2023, 12, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.; Elgorban, A.M.; Bahkali, A.H.; Eswaramoorthy, R.; Iqbal, R.K.; Danish, S. Metal-tolerant and siderophore producing Pseudomonas fluorescence and Trichoderma spp. improved the growth, biochemical features and yield attributes of chickpea by lowering Cd uptake. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Sahile, A.A.; Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Hamayun, M.; Imran, M.; Adhikari, A.; Kang, S.-M.; Kim, K.-M.; Lee, I.-J. Halotolerant bacteria mitigate the effects of salinity stress on soybean growth by regulating secondary metabolites and molecular responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Pandey, D.M.; Jha, P.N.; Ma, Y. ACC deaminase producing rhizobacterium Enterobacter cloacae ZNP-4 enhance abiotic stress tolerance in wheat plant. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3: Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America and American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Bain, D.A. A sodium hydroxide fusion method for the determination of total phosphate in soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1982, 13, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Subramanian, S.; Faith, J.J.; Gevers, D.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R.; Mills, D.A.; Caporaso, J.G. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, J. The Intratumor Microbiota Signatures Associate With Subtype, Tumor Stage, and Survival Status of Esophageal Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 754788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhine, E.D.; Mulvaney, R.L.; Pratt, E.J.; Sims, G.K. Improving the Berthelot Reaction for Determining Ammonium in Soil Extracts and Water. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1998, 62, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickmann, E.; Dessaux, Y. A critical examination of the specificity of the salkowski reagent for indolic compounds produced by phytopathogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper Enzymes in Isolated Chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta Vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Du, D. Optimization of chlorophyll content determination method for Brassica napus L. leaves and comparison of chlorophyll content at different stages. J. Qinghai Univ. 2024, 42, 56–60+93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J. Determination of soluble protein content in alfalfa by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 staining method. Agric. Eng. Technol. 2016, 36, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TN # g/kg | TP g/kg | TK g/kg | AN mg/kg | AP mg/kg | AK mg/kg | SOM g/kg | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 2.10 | 0.81 | 17.70 | 136.82 | 24.25 | 149.10 | 34.80 | 7.88 |

| AS | 3.20 | 0.74 | 23.00 | 224.92 | 16.95 | 157.40 | 53.90 | 8.25 |

| Strain ID | Comparative Information | Phylogenetic Affiliation | Similarity (%) | GenBank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 98.94% | OQ876139.1 |

| M2 | Enterobacter mori | Enterobacter | 94.70% | LC617171.1 |

| M3 | Proteus mirabilis | Proteus | 99.65% | OL629224.1 |

| M5 | Pseudomonas lini | Pseudomonas | 100.00% | OQ654023.1 |

| M7 | Escherichia sp. | Escherichia | 99.07% | KJ803863.1 |

| M9 | Escherichia coli | Escherichia | 99.58% | MN704526.1 |

| M10 | Bacillus siamensis | Bacillus | 99.93% | PV012710.1 |

| M13 | Janthinobacterium svalbardensis | Janthinobacterium | 99.22% | MW927167.1 |

| M16 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 100.00% | HQ433576.1 |

| M17 | Novosphingobium barchaimii | Novosphingobium | 100.00% | MW433633.1 |

| M21 | Duganella zoogloeoides | Duganella | 99.29% | MN752691.1 |

| M22 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 99.86% | KC119103.1 |

| M25 | Brevundimonas sp. | Brevundimonas | 100% | MK414927.1 |

| M27 | Bacillus cereus | Bacillus | 99.93% | MG027629.1 |

| M29 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 99.86% | KT900618.1 |

| M32 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 100.00% | PQ657652.1 |

| M33 | Bacillus toyonensis | Bacillus | 99.93% | MW405814.1 |

| M36 | Achromobacter xylosoxidans | Achromobacter | 99.79% | KJ569364.1 |

| M39 | Peribacillus frigoritolerans | Peribacillus | 99.59% | OM281797.1 |

| M40 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 99.86% | MW116732.1 |

| M49 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 99.93% | MW753132.1 |

| M51 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 100.00% | MH329935.1 |

| M53 | Paenibacillus sp. | Paenibacillus | 99.58% | AM162308.1 |

| M59 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 100.00% | KT583425.1 |

| M62 | Bacillus sp. | Priestia | 98.21% | OM346694.1 |

| M64 | Bacillus acidiceler | Bacillus | 99.79% | KJ575070.1 |

| M66 | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Stenotrophomonas | 99.93% | OP765271.1 |

| M67 | Enterobacter sp. | Enterobacter | 99.72% | KJ584024.1 |

| M68 | Pseudomonas chlororaphis | Pseudomonas | 100.00% | OQ363217.1 |

| M69 | Neobacillus sp. | Neobacillus | 99.79% | OR878890.1 |

| M72 | Bacillus thuringiensis | Bacillus | 100.00% | OP986100.1 |

| M73 | Pseudomonas putida | Pseudomonas | 99.93% | HM486417.1 |

| M77 | Kosakonia oryzendophytica | Kosakonia | 99.65% | MW020337.1 |

| M79 | Pseudomonas protegens | Pseudomonas | 100.00% | PQ573341.1 |

| M81 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas | 99.93% | JQ659631.1 |

| M89 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 100.00% | OR362817.1 |

| M92 | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus | 97.81% | MN044783.1 |

| M93 | Escherichia sp. | Escherichia | 99.30% | OQ876054.1 |

| M95 | Stenotrophomonas geniculata | Stenotrophomonas | 100.00% | KJ452162.2 |

| M97 | Acinetobacter guillouiae | Acinetobacter | 100.00% | MH144279.1 |

| M98 | Peribacillus frigoritolerans | Peribacillus | 100.00% | MZ712051.1 |

| M103 | Kosakonia oryzendophytica | Kosakonia | 99.79% | PQ781316.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Han, T.; Huang, F.; Li, X.; Shan, J.; Zhang, D.; Shen, Z.; Wang, J.; Qiao, K. Saline–Alkaline Stress-Driven Rhizobacterial Community Restructuring and Alleviation of Stress by Indigenous PGPR in Alfalfa. Plants 2025, 14, 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243844

Wang M, Han T, Huang F, Li X, Shan J, Zhang D, Shen Z, Wang J, Qiao K. Saline–Alkaline Stress-Driven Rhizobacterial Community Restructuring and Alleviation of Stress by Indigenous PGPR in Alfalfa. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243844

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Min, Ting Han, Fenghua Huang, Xiaochen Li, Jiayao Shan, Dongmei Zhang, Zhongbao Shen, Jianli Wang, and Kun Qiao. 2025. "Saline–Alkaline Stress-Driven Rhizobacterial Community Restructuring and Alleviation of Stress by Indigenous PGPR in Alfalfa" Plants 14, no. 24: 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243844

APA StyleWang, M., Han, T., Huang, F., Li, X., Shan, J., Zhang, D., Shen, Z., Wang, J., & Qiao, K. (2025). Saline–Alkaline Stress-Driven Rhizobacterial Community Restructuring and Alleviation of Stress by Indigenous PGPR in Alfalfa. Plants, 14(24), 3844. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243844