Inhibition of Sterol Biosynthesis Alters Tubulin Association with Detergent-Insoluble Membranes and Affects Microtubule Organization in Pollen Tubes of Nicotiana tabacum L.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Squalestatin Affects Sterol Biosynthesis and Delays Pollen Tube Emission

2.2. Sterol Depletion Affects Interaction Between Tubulin and Detergent-Insoluble Membranes

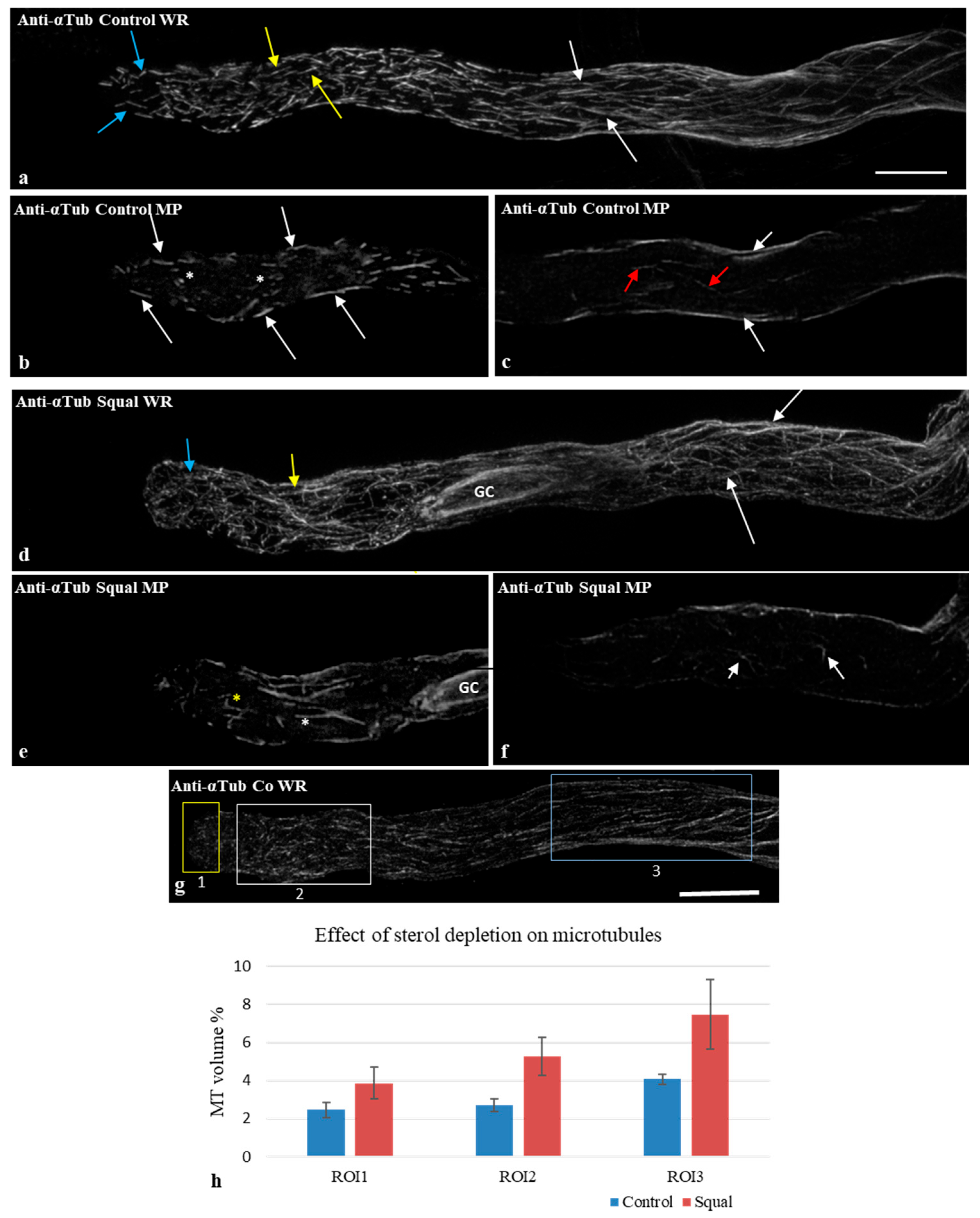

2.3. Squalestatin Induced Changes in Microtubule Distribution Pattern

2.4. Sterol Depletion Influences the Bundling Activity of Cortical Microtubules in the Apical and Subapical Regions of Pollen Tubes

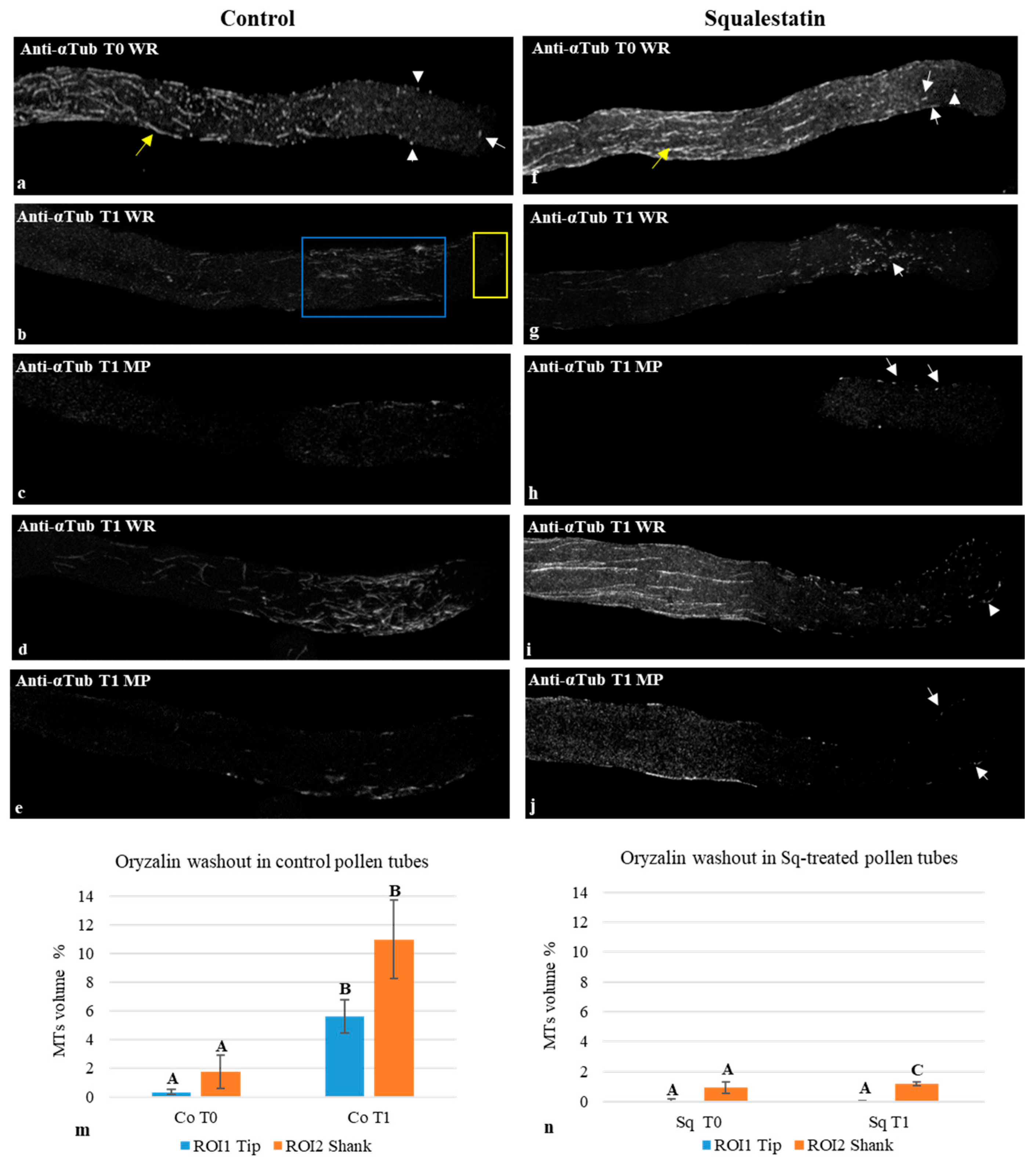

2.5. Oryzalin Washout Experiments

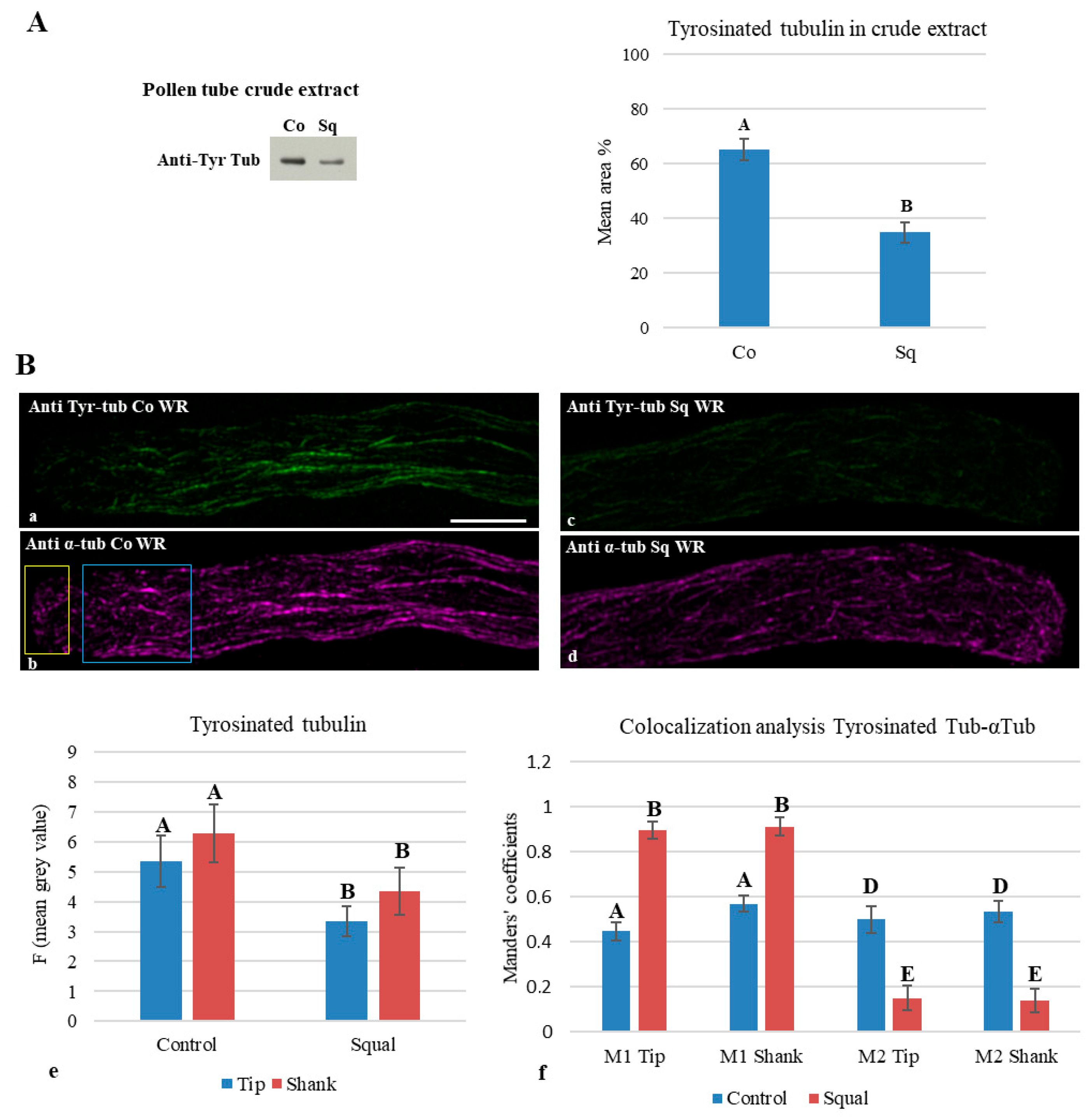

2.6. Post-Translational Modification of Tubulins

3. Discussion

3.1. Inhibition of Sterol Biosynthesis Delays Pollen Germination

3.2. Sterol Depletion Affects the Interaction of Tubulin with Pollen Tube Detergent-Insoluble Membranes

3.3. Sterols Are Involved in Microtubule Organization

3.4. Sterol Depletion Affected the Bundling Capacity of Cortical MTs

3.5. Sterol Depletion Affected MT Nucleation

3.6. Sterol Depletion Affected Post-Translational Modifications of Tubulin

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Germination Assay and Pollen Tube Measurement

5.2. Probes and Drugs

5.3. Pollen Tube Crude Extract

5.4. Cell Fractionation

5.5. HPTLC Analysis of Lipids

5.6. Preparation of Detergent-Insoluble Membranes (DIMs)

5.7. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot

5.8. Indirect Immunofluorescence

5.9. Double Immunofluorescence and Colocalization Analysis

5.10. Oryzalin Washout Experiments

5.11. Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy

5.12. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMP | Plasma membrane |

| Lo | Liquid-ordered domains |

| Ld | Liquid-disordered domains |

| DIMs | Detergent-insoluble membranes |

| AFs | Actin filaments |

| MTs | Microtubules |

| Sq | Squalestatin |

| Myr | Myriocin |

| MAPs | Microtubule-binding proteins |

| WR | Whole reconstruction |

| MP | Medial plane |

| GC | Generative cell |

References

- Navashin, S.G. Resultate einer revision der befruchtungsvorgange bei Lilium martagon und Fritillaria tenella. Bull. Acad. Sci. St. Petersburg 1898, 9, 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Guignard, M.L. Sur les antherozoides et la double copulation sexuelle chez les vegetaux angiosperms. Rev. Gén. Bot. 1899, 11, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Vidali, L.; McKenna, S.T.; Hepler, P.K. Actin polymerization is essential for pollen tube growth. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 2534–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, L.; Lovy-Wheeler, A.; Wilsen, K.L.; Hepler, P.K. Actin polymerization promotes the reversal of streaming in the apex of pollen tubes. Cell Motil. Cytoskel. 2005, 61, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.Y.; Wu, H.M. Structural and signalling networks for the polar cell growth machinery in pollen tubes. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 547–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.J.; Nicolson, G. The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science 1972, 175, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Ikonen, E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 1997, 387, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohvo-Rekilä, H.; Ramstedt, B.; Leppimäki, P.; Slotte, J.P. Cholesterol interactions with phospholipids in membranes. Prog. Lipid Res. 2002, 41, 66–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, J.R. Role of cholesterol in lipid raft formation: Lessons from lipid model systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1610, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingwood, D.; Simons, K. Lipid rafts as a membrane organization principle. Science 2010, 327, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillais, Y.; Ott, T. The nanoscale organization of the plasma membrane and its importance in signaling: A proteolipid perspective. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1682–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.; London, E.; Brown, D. Interactions between saturated acyl chains confer detergent resistance on lipids and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins: GPI-anchored proteins in liposomes and cells show similar behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 12130–12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; London, E. Structure of detergent-resistant membrane domains: Does phase separation occur in biological membranes? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 240, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñiz, M.; Zurzolo, C. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins from yeast to mammals--common pathways at different sites? J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 2793–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fratini, M.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Stenzel, I.; Riechmann, M.; Matzner, M.; Bacia, K.; Heilmann, M.; Heilmann, I. Plasma membrane nano-organization specifies phosphoinositide effects on Rho-GTPases and actin dynamics in tobacco pollen tubes. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 642–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.N.; Brown, D.A.; London, E. On the origin of sphingolipid/cholesterol-rich detergent-insoluble cell membranes: Physiological concentrations of cholesterol and sphingolipid induce formation of a detergent-insoluble, liquid-ordered lipid phase in model membranes. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 10944–10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; London, E. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17221–17224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.; Bagatolli, L.A.; Volovyk, Z.N.; Thompson, N.L.; Levi, M.; Jacobson, K.; Gratton, E. Lipid rafts reconstituted in model membranes. Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, E. into lipid raft structure and formation from experiments in model membranes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002, 12, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongrand, S.; Morel, J.; Laroche, J.; Claverol, S.; Carde, J.P.; Hartman, M.A.; Bonneu, M.; Simon Plas, F.; Lessire, R.; Bessoule, J.J. Lipid rafts in higher plant cells: Purification and characterization of Triton X-100-insoluble microdomains from tobacco plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 36277–36286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borner, G.H.; Sherrier, D.J.; Weimar, T.; Michaelson, L.V.; Hawkins, N.D.; Macaskill, A.; Napier, J.A.; Beale, M.H.; Lilley, K.S.; Dupree, P. Analysis of detergent-resistant membranes in Arabidopsis. Evidence for plasma membrane lipid rafts. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacas, J.L.; Furt, F.; Le Guedard, M.; Schmitter, J.M.; Buré, C.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P.; Moreau, P.; Bessoule, J.J.; Simon-Plas, F.; Mongrand, S. Lipids of plant membrane rafts. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012, 51, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscatelli, A.; Gagliardi, A.; Maneta-Peyret, L.; Bini, L.; Stroppa, N.; Onelli, E.; Scali, M.; Idilli, A.I.; Moreau, P. Characterization of detergent-insoluble membranes in pollen tubes of Nicotiana tabacum (L.). Biol. Open 2015, 4, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimmen, T. The sliding theory of cytoplasmic streaming: Fifty years of progress. J. Plant Res. 2007, 120, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, L.; Lovy-Wheeler, A.; Kunkel, J.G.; Hepler, P.K. Pollen tube oscillatory and intracellular calcium levels are reversibly modulated by actin polymerization. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Lee, D.; McCormick, S. Interdependence of endomembrane trafficking and actin dynamics during polarized growth of Arabidopsis pollen tubes. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 2200–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovy-Wheeler, A.; Wilsen, K.L.; Baskin, T.I.; Hepler, P.K. Enhanced fixation reveals the apical cortical fringe of actin filaments as a consistent feature if the pollen tube. Planta 2005, 221, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidali, L.; Round, C.M.; Hepler, P.K.; Bezanilla, M. Lifeact-mEGFP reveals a dynamic apical Factin network in tip growing plant cells. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounds, C.M.; Hepler, P.K.; Winship, L.J. The apical actin fringe contributes to localized cell wall deposition and polarized growth in the lily pollen tube. Plant Physiol. 2014, 18, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kost, B.; Lemichez, E.; Spielhofer, P.; Hong, Y.; Tolias, K.; Carpenter, C.; Chua, N.H. Rac homologues and compartmentalized phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate act in a common pathway to regulate polar pollen tube growth. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 145, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wu, G.; Yang, Z. Rop GTPase-dependent dynamics of tip localized F-actin controls tip growth in pollen tubes. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 152, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Vernoud, V.; Fu, Y.; Yang, Z. ROP GTPase regulation of pollen tube growth through the dynamics of tip-localized F-actin. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J.; Szumlanski, A.; Nielsen, E.; Yang, Z. Rho-GTPase-dependent filamentous actin dynamics coordinate vesicle targeting and exocytosis during tip growth. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 181, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smokvarska, M.; Jaillais, Y.; Martiniere, A. Function of membrane domains in rho-of-plant signaling. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furt, F.; Konig, S.; Bessoule, J.J.; Sargueil, F.; Zallot, R.; Stanislas, T.; Noirot, E.; Lherminier, J.; Simon-Plas, F.; Heilmann, I.; et al. Polyphosphoinositides are enriched in plant membrane rafts and form microdomains in the plasma membrane. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 2173–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Yang, N.; Pu, H.; Wang, T. Quantitative proteomics and cytology of rice pollen sterol-rich membrane domains reveals pre-established cell polarity cues in mature pollen. J. Proteome 2018, 17, 1532–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, M.; Bloch, D.; Hazak, O.; Gutman, I.; Poraty, L.; Sorek, N.; Sternberg, H.; Yalovsky, S. A novel ROP/RAC effector links cell polarity, root-meristem maintenance, and vesicle trafficking. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gu, Y.; Yan, A.; Lord, E.; Yang, Z.B. RIP1 (ROP Interactive Partner 1)/ICR1 marks pollen germination sites and may act in the ROP1 pathway in the control of polarized pollen growth. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Casino, C.; Li, Y.Q.; Moscatelli, A.; Scali, M.; Tiezzi, A.; Cresti, M. Distribution of microtubules during the growth of tobacco pollen tubes. Biol. Cell 1993, 79, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idilli, A.I.; Morandini, P.; Onelli, E.; Rodighiero, S.; Caccianiga, M.; Moscatelli, A. Microtubule depolymerization affects endocytosis and exocytosis in the tip and influences endosome movement in tobacco pollen tubes. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 1109–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrom, H. Acetylated alpha-tubulin in the pollen tube microtubules. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 1992, 16, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joos, U.; van Aken, J.; Kristen, U. Microtubules are involved in maintaining the cellular polarity in pollen tubes of Nicotiana sylvestris. Protoplasma 1994, 179, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onelli, E.; Idilli, A.I.; Moscatelli, A. Emerging roles for microtubules in angiosperm pollen tube growth highlight new research cues. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onelli, E.; Scali, M.; Caccianiga, M.; Stroppa, N.; Morandini, P.; Pavesi, G.; Moscatelli, A. Microtubules play a role in trafficking prevacuolar compartments to vacuoles in tobacco pollen tubes. Open Biol. 2018, 8, 180078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, E.; Wolf, S.G.; Downing, K.H. Structure of the alpha beta tubulin dimer by electron crystallography. Nature 1998, 391, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, E. Structural insight into microtubule function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2001, 30, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchison, T.K.; Kirschner, M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature 1984, 312, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Mitchison, T.J. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997, 13, 83–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horio, T.; Murata, T. The role of dynamic instability in microtubule organization. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snustad, D.P.; Haas, N.A.; Kopczak, S.D.; Silflow, C.D. The small genome of Arabidopsis contains at least nine expressed β-tubulin genes. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.L.; Ploense, S.E.; Snustad, D.P.; Silflow, C.D. Preferential expression of an α-tubulin gene of Arabidopsis in pollen. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, C.; Bulinski, J.C. Post-translational regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton: Mechanisms and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, J. Post-translational modifications of plant microtubules. Plant Sig. Behav. 2019, 14, e1654818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.; Calder, G.M.; Doonan, J.H.; Lloyd, C.W. EB1 reveals mobile microtubule nucleation sites in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, T.; Nagasaki-Takeuchi, N.; Kato, T.; Fujiwara, M.; Sonobe, S.; Fukao, Y.; Hashimoto, T. Purification and characterization of novel microtubule-associated proteins from Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 1804–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, T. Microtubule organization and microtubule-associated proteins in plant cells. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 312, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, H.V.; Jonasson, E.M. Microtubules and microtubule-associated proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a022608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Würtz, M.; Zupa, E.; Pfeffer, S.; Schiebel, E. Microtubule nucleation: The waltz between γ-tubulin ring complex and associated proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021, 68, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt, D.W.; Shaw, S.L. Microtubule dynamics and organization in the plant cortical array. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, J.C.; Wasteneys, G.O. CLASP modulates microtubule-cortex interaction during self-organization of acentrosomal microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 4730–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.; Shaw, S.L. Update: Plant cortical microtubule arrays. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roll-Mecak, A. The tubulin code in microtubule dynamics and information encoding. Dev. Cell 2020, 54, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancelle, S.A.; Cresti, M.; Hepler, P.K. Ultrastructure of the cytoskeleton in freeze-substituted pollen tubes of Nicotiana alata. Protoplasma 1987, 140, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Ovidi, E.; Romagnoli, S.; Vantard, M.; Cresti, M.; Tiezzi, A. Identification and characterization of plasma membrane proteins that bind to microtubules in pollen tubes and generative cells of tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005, 46, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.J.; Ahmed, S.N.; Zhu, Y.; London, E.; Brown, D.A. Cholesterol and sphingolipid enhance the Triton X-100 insolubility of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins by promoting the formation of detergent-insoluble ordered membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, E.; Brown, D.A. Insolubility of lipids in triton X-100: Physical origin and relationship to sphingolipid/cholesterol membrane domains (rafts). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1508, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, Y.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P.; Buhot, B.; Thomas, D.; Bonneau, L.; Gresti, J.; Mongrand, S.; Perrier-Cornet, J.M.; Simon-Plas, F. Depletion of phytosterols from the plant plasma membrane provides evidence for disruption of lipid rafts. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 3980–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linetti, A.; Fratangeli, A.; Taverna, E.; Valnegri, P.; Francolini, M.; Cappello, V.; Matteoli, M.; Passafaro, M.; Rosa, P. Cholesterol reduction impairs exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villette, C.; Berna, A.; Compagnon, V.; Schaller, H. Plant sterol diversity in pollen from angiosperms. Lipids 2015, 50, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroppa, N.; Onelli, E.; Moreau, P.; Maneta-Peyret, L.; Berno, V.; Cammarota, E.; Ambrosini, R.; Caccianiga, M.S.; Scali, M.; Moscatelli, A. Sterols and sphingolipids as new players in cell wall building and apical growth of Nicotiana tabacum L. pollen tubes. Plants 2023, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repko, E.M.; Maltese, W.A. Post-translational isoprenylation of cellular proteins is altered in response to mevalonate availability. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 9945–9952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, A.; Fitzgerald, B.J.; Hutson, J.L.; McCarthyS, A.D.; Motteram, J.M.; Ross, B.C.; Sapra, M.; Nowden, M.A.; Watson, N.S.; Williams, R.J.; et al. Squalestatin 1, a potent inhibitor of squalene synthase, which lowers serum cholesterol in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 11705–11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergstrom, J.D.; Kurtz, M.M.; Rew, D.J.; Amend, A.M.; Karkas, J.D.; Bostedor, R.G.; Bansal, V.S.; Dufresne, C.; Van Middlesworth, F.L.; Hensens, O.D.; et al. Zaragozic acids: A family of fungal metabolites that are picomolar competitive inhibitors of squalene synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechlivanis, M.; Kuhlmann, J. Hydrophobic modifications of Ras proteins by isoprenoid groups and fatty acids—More than just membrane anchoring. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1764, 1914–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotsch, A.H.; Kopka, J.; Feussner, I.; Ischebeck, T. Central metabolite and sterol profiling divides tobacco male gametophyte development and pollen tube growth into eight metabolic phases. Plant J. 2017, 92, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, C.; Magiera, M.M. The tubulin code and its role in controlling microtubule properties and functions. Nature 2020, 21, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, B.; Furt, F.; Hartmann, M.A.; Michaelson, L.V.; Carde, J.P.; Sargueil-Boiron, F.; Rossignol, M.; Napier, J.A.; Cullimore, J.; Bessoule, J.J.; et al. Characterization of lipid rafts from Medicago truncatula root plasma membranes: A proteomic study reveals the presence of a raft-associated redox system. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudenege, S.; Dargelos, E.; Claverol, S.; Bonneu, M.; Cottin, P.; Poussard, S. Comparative proteomic analysis of myotube caveolae after milli-calpain deregulation. Proteomics 2007, 7, 3289–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, S.N.; Gangaraju, S.; Aylsworth, A.; Hou, S.T. Membrane raft disruption results in neuritic retraction prior to neuronal death in cortical neurons. Bioscience Trends 2012, 6, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Zavzavadjian, J. Glycolipid-enriched membrane domains are assembled into membrane patches by associating with the actin cytoskeleton. Exp. Cell Res. 2001, 267, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, A.D.; Vale, R.D. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell 2005, 121, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, B.P.; Patel, H.H.; Roth, D.M.; Murray, F.; Swaney, J.S.; Niesman, I.R.; Farquhar, M.G.; Insel, P.A. Microtubules and actin microfilaments regulate lipid raft/caveolae localization of adenylyl cyclase signaling components. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 26391–26399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, A.; Gupta, N. Tether and trap: Regulation of membrane-raft dynamics by actin-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chichili, G.R.; Rodgers, W. Cytoskeleton-membrane interactions in membrane raft structure. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 2319–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Zhang, J.; Miyazawa, S.; Liu, Q.; Farzan, M.R.; Yao, W.D. Association of membrane rafts and postsynaptic density: Proteomics, biochemical, and ultrastructural analyses. J. Neurochem. 2011, 119, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilangumaran, S.; Hoessli, D.C. Effects of cholesterol depletion by cyclodextrin on the sphingolipid microdomains of the plasma membrane. Biochem. J. 1998, 335, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.C.; Polito, V.S. The initiation and organization of microtubules in germinating pear (Pyrus communis L.) pollen. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1990, 53, 384–389. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, T.; Ueda, H.; Kawase, T.; Hara-Nishimura, I. Microtubules contribute to tubule elongation and anchoring of endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in high network complexity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1869–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, L.; Stefano, G.; Slabaugh, E.; Wormsbaecher, C.; Sulpizio, A.; Zienkiewicz, K.; Brandizzi, F. TGNap1 is required for microtubule-dependent homeostasis of a subpopulation of the plant trans-Golgi network. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, M.O.; Ruano, G.; Zouhar, J.; Sauer, M.; Shen, J.; Lazarova, A.; Sanmartín, M.; Faat Lai, L.T.; Deng, C.; Wang, P.; et al. MTV proteins unveil ER- and microtubule-associated compartments in the plant vacuolar trafficking pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9884–9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.; Li, H.; Downing, K.H.; Nogales, E. Refined structure of alpha beta-tubulin at 3.5 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 313, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, R.E. Membrane tubulin. Biol. Cell 1986, 57, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambito, A.M.; Wolff, J. Palmitoylation of tubulin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 239, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caron, J.M. Posttranslational modification of tubulin by palmitoylation: I. in vivo and cell-free studies. Mol. Biol. Cell 1997, 8, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestini, P.; Pitto, M.; Tedeschi, G.; Ferraretto, A.; Parenti, M.; Brunner, J.; Masserini, M. Tubulin anchoring to glycolipid-enriched, detergent-resistant domains of the neuronal plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 9978–9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Hashimoto, T. Microtubule and katanin-dependent dynamics of microtubule nucleation complexes in the acentrosomal Arabidopsis cortical array. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeboom, J.J.; Nakamura, M.; Marco Saltini, M.; Hibbel, A.; Walia, A.; Ketelaar, T.; Emons, A.M.C.; Sedbrook, J.C.; Kirik, V.; Mulder, B.M.; et al. CLASP stabilization of plus ends created by severing promotes microtubule creation and reorientation. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 218, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaoka, Y.; Akatsuki Kimura, A.; Tani, T.; Goshima, G. Cytoplasmic nucleation and atypical branching nucleation generate endoplasmic microtubules in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Sonobe, S.; Baskin, T.I.; Hyodo, S.; Hasezawa, S.; Nagata, T.; Horio, T.; Hasebe, M. Microtubule-dependent microtubule nucleation based on recruitment of gamma-tubulin in higher plants. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 7, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, S.; Kumanogoh, H.; Funatsu, N.; Takei, N.; Inoue, K.; Endo, Y.; Hamada, K.; Sokawa, Y. Identification of NAP-22 and GAP-43 (neuromodulin) as major protein components in a Triton insoluble low density fraction of rat brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1323, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, S.; Morii, H.; Kumanogoh, H.; Sano, M.; Naruse, Y.; Sokawa, Y.; Mori, N. Localization of neuronal growth-associated, microtubule-destabilizing factor SCG10 in brain-derived raft membrane microdomain. J. Biochem. 2001, 129, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, J. The evolution and diversification of plant microtubule associated proteins. Plant J. 2013, 75, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiezzi, A.; Moscatelli, A.; Cai, G.; Bartalesi, A.; Cresti, M. An immunoreactive homolog of mammalian kinesin in Nicotiana tabacum pollen tube. Cell Motil. Cytoskel. 1992, 21, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Bartalesi, A.; Del Casino, C.; Moscatelli, A.; Tiezzi, A.; Cresti, M. The kinesin-immunoreactive homologue from Nicotiana tabacum pollen tubes: Biochemical properties and subcellular localization. Planta 1993, 191, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Romagnoli, S.; Moscatelli, A.; Ovidi, E.; Gambellini, G.; Tiezzi, A.; Cresti, M. Identification and characterization of a novel microtubule-based motor associated with membranous organelles in tobacco pollen tubes. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1719–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiguelman, G.; Cui, X.; Sternberg, H.; Ben Hur, E.; Higa, T.; Oda, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yalovsky, S. Microtubule-associated ROP interactors affect microtubule dynamics and modulate cell wall patterning and root hair growth. Development 2022, 149, dev201502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, S.V.; Chang, F. Mechanisms for maintaining microtubule bundles. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Hotta, T.; Lee, Y.R.J.; Horio, T.; Liu, B. The γ -tubulin complex protein GCP4 is required for organizing functional microtubule arrays in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smertenko, A.P.; Chang, H.-Y.; Wagner, V.; Kaloriti, D.; Fenyk, S.; Sonobe, S.; Lloyd, C.; Hauser, M.-T.; Hussey, P.J. The Arabidopsis microtubule-associated protein AtMAP65-1: Molecular analysis of its microtubule bundling activity. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2035–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulin, A.; McClerklin, S.; Huang, Y.; Dixit, R. Single-molecule analysis of the microtubule cross-linking protein MAP65-1 reveals a molecular mechanism for contact-angle-dependent microtubule bundling. Biophys. J. 2012, 22, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, W.J.C.; Shoji, T.; Kotzer, A.M.; Pighin, J.A.; Wasteneys, G.O. The Arabidopsis CLASP gene encodes a microtubule-associated protein involved in cell expansion and division. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2763–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoms, D.; Vineyard, L.; Elliott, A.; Shaw, S.L. CLASP facilitates transitions between cortical microtubule array patterns. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 1551–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirik, V.; Herrmann, U.; Parupalli, C.; Sedbrook, J.C.; Ehrhardt, D.W.; Hülskamp, M. CLASP localizes in two discrete patterns on cortical microtubules and is required for cell morphogenesis and cell division in Arabidopsis. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 4416–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Moscatelli, A.; Del Casino, C.; Chevrier, V.; Mazzi, M.; Tiezzi, A.; Cresti, M. The anti-centrosome monoclonal antibody 6C6 reacts with a plasma membrane-associated polypeptide of 77 kDa from Nicotiana tabacum pollen tubes. Protoplasma 1996, 190, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollman, J.M.; Merdes, A.; Mourey, L.; Agard, D.A. Microtubule nucleation by gamma-tubulin complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostalu, J.; Surrey, T. Microtubule nucleation: Beyond the template. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, T.J.; Borisy, G.G. Immunostructural evidence for the template mechanism of microtubule nucleation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppin, V.; Vantard, M.; Schmit, A.C.; Lambert, A.M. Isolated plant nuclei nucleate microtubule assembly: The nuclear surface in higher plants has centrosome-like activity. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, M.; Stoppin-Mellet, V.; Campagne, S.; Canaday, J.; Mutterer, J.; Fabian, T.; Sauter, M.; Muller, T.; Peter, C.; Lambert, A.M.; et al. The plant Spc98p homologue colocalizes with γ-tubulin at microtubule nucleation sites and is required for microtubule nucleation. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.L.; Kamyar, R.; Ehrhardt, D.W. Sustained microtubule treadmilling in Arabidopsis cortical arrays. Science 2003, 300, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bruaene, N.; Joss, G.; Van Oostveldt, P. Reorganization and in vivo dynamics of microtubules during Arabidopsis root hair development. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3905–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efimov, A.; Kharitonov, A.; Efimova, N.; Loncarek, J.; Miller, P.M.; Andreyeva, N.; Gleeson, P.; Galjart, N.; Maia, A.R.; McLeod, I.X.; et al. Asymmetric CLASP-dependent nucleation of noncentrosomal microtubules at the trans-Golgi Network. Dev. Cell 2007, 12, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luduena, R.F. Multiple forms of tubulin: Different gene products and covalent modifications. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1998, 178, 207–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhey, K.J.; Gaertig, J. The tubulin code. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 2152–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Flavin, M. Preferential action of a brain detyrosinolating carboxypeptidase on polymerized tubulin. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256, 7678–7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prota, A.E.; Magiera, M.M.; Kuijpers, M.; Bargsten, K.; Frey, D.; Wieser, M.; Jaussi, R.; Hoogenraad, C.C.; Kammerer, R.A.; Janke, C.; et al. Structural basis of tubulin tyrosination by tubulin tyrosine ligase. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Flavin, M. Modulation of some parameters of assembly of microtubules in vitro by tyrosinolation of tubulin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1982, 128, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreis, T.E. Microtubules containing detyrosinated tubulin are less dynamic. EMBO J. 1987, 6, 2597–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.R.; Gundersen, G.G.; Bulinski, J.C.; Borisy, G.G. Differential turnover of tyrosinated and detyrosinated microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 9040–9044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambray-Deakin, M.A.; Burgoyne, R.D. Acetylated and detyrosinated alpha- tubulins are co- localized in stable microtubules in rat meningeal fibroblasts. Cell Motil. Cytoskel. 1987, 8, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erck, C.; Peris, L.; Andrieux, A.; Meissirel, C.; Gruber, A.D.; Vernet, M.; Schweitzer, A.; Saoudi, Y.; Pointu, H.; Bosc, C.; et al. A vital role of tubulin-tyrosine-ligase for neuronal organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7853–7858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris, L.; Thery, M.; Fauré, J.; Saoudi, Y.; Lafanechère, L.; Chilton, J.K.; Gordon-Weeks, P.; Galjart, N.; Bornens, M.; Wordeman, L.; et al. Tubulin tyrosination is a major factor affecting the recruitment of CAP- Gly proteins at microtubule plus ends. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peris, L.; Wagenbach, M.; Lafanechere, L.; Brocard, J.; Moore, A.T.; Kozielski, F.; Job, D.; Wordeman, L.; Andrieux, A. Motor-dependent microtubule disassembly driven by tubulin tyrosination. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 185, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirajuddin, M.; Rice, L.M.; Vale, R.D. Regulation of microtubule motors by tubulin isotypes and post-translational modifications. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddé, B.; Rossier, J.; Le Carer, J.P.; Desbruyères, E.; Gros, F.; Denoulet, P. Posttranslational glutamylation of alpha-tubulin. Science 1990, 247, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audebert, S.; Desbruyères, E.; Gruszczynski, C.; Koulakoff, A.; Gros, F.; Denoulet, P.; Eddé, B. Reversible polyglutamylation of alpha- and beta- tubulin and microtubule dynamics in mouse brain neurons. Mol. Biol. Cell 1993, 4, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, C.; Rogowski, K.; Wloga, D.; Regnard, C.; Kajava, A.V.; Strub, J.M.; Temurak, N.; van Dijk, J.; Boucher, D.; van Dorsselaer, A.; et al. Tubulin polyglutamylase enzymes are members of the TTL domain protein family. Science 2005, 308, 1758–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, K.; van Dijk, J.; Magiera, M.M.; Bosc, C.; Deloulme, J.C.; Bosson, A.; Peris, L.; Gold, N.D.; Lacroix, B.; Bosch Grau, M.; et al. A family of protein-deglutamylating enzymes associated with neurodegeneration. Cell 2010, 143, 564–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A.; Houdayer, M.; Chillet, D.; de Ne´chaud, B.; Denoulet, P. Structure of the polyglutamyl chain of tubulin: Occurrence of alpha and gamma linkages between glutamyl units revealed by monoreactive polyclonal antibodies. Biol. Cell 1994, 81, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kirkpatrick, L.L.; Schilling, A.B.; Helseth, D.L.; Chabot, N.; Keillor, J.W.; Johnson, G.V.W.; Brady, S. Transglutaminase and polyamination of tubulin: Posttranslational modification for stabilizing axonal microtubules. Neuron 2013, 78, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, C.; Boucher, D.; Lazereg, S.; Pedrotti, B.; Islam, K.; Denoulet, P.; Larcher, J.C. Differential binding regulation of microtubule-associated proteins MAP1A, MAP1B, and MAP2 by tubulin polyglutamylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 12839–12848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewbaker, J.L.; Kwack, B.H. The essential role of calcium ions in pollen germination and pollen tube growth. Am. J. Bot. 1963, 50, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Poland, J.; Schnolzer, M.; Rabilloud, T. A new silver staining apparatus and procedure for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight analysis of proteins after two-dimensional electrophoresis. Proteomics 2001, 1, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towbin, H.; Staehelin, T.; Gordon, J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets. Procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 4350–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilemann, M.; van de Linde, S.; Schüttpelz, M.; Kasper, R.; Seefeldt, B.; Mukherjee, A.; Tinnefeld, P.; Sauer, M. Subdiffraction-resolution fluorescence imaging with conventional fluorescent probes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6172–6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangi, A.F.; Niessen, W.J.; Hoogeveen, R.M.; van Walsum, T.; Viergever, M.A. Model-based quantitation of 3-D magnetic resonance angiographic images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 1999, 18, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerman, T. Jerman Enhancement Filter. GitHub. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/timjerman/JermanEnhancementFilter (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Bolte, S.; Cordelières, F.P. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 2006, 224, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Onelli, E.; Maneta-Peyret, L.; Moreau, P.; Stroppa, N.; Berno, V.; Cammarota, E.; Caccianiga, M.; Gianfranceschi, L.; Moscatelli, A. Inhibition of Sterol Biosynthesis Alters Tubulin Association with Detergent-Insoluble Membranes and Affects Microtubule Organization in Pollen Tubes of Nicotiana tabacum L. Plants 2025, 14, 3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243845

Onelli E, Maneta-Peyret L, Moreau P, Stroppa N, Berno V, Cammarota E, Caccianiga M, Gianfranceschi L, Moscatelli A. Inhibition of Sterol Biosynthesis Alters Tubulin Association with Detergent-Insoluble Membranes and Affects Microtubule Organization in Pollen Tubes of Nicotiana tabacum L. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243845

Chicago/Turabian StyleOnelli, Elisabetta, Lilly Maneta-Peyret, Patrick Moreau, Nadia Stroppa, Valeria Berno, Eugenia Cammarota, Marco Caccianiga, Luca Gianfranceschi, and Alessandra Moscatelli. 2025. "Inhibition of Sterol Biosynthesis Alters Tubulin Association with Detergent-Insoluble Membranes and Affects Microtubule Organization in Pollen Tubes of Nicotiana tabacum L." Plants 14, no. 24: 3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243845

APA StyleOnelli, E., Maneta-Peyret, L., Moreau, P., Stroppa, N., Berno, V., Cammarota, E., Caccianiga, M., Gianfranceschi, L., & Moscatelli, A. (2025). Inhibition of Sterol Biosynthesis Alters Tubulin Association with Detergent-Insoluble Membranes and Affects Microtubule Organization in Pollen Tubes of Nicotiana tabacum L. Plants, 14(24), 3845. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243845