Competitive Interactions Among Populus euphratica Seedlings Intensify Under Drought and Salt Stresses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Stress on Morphological Features

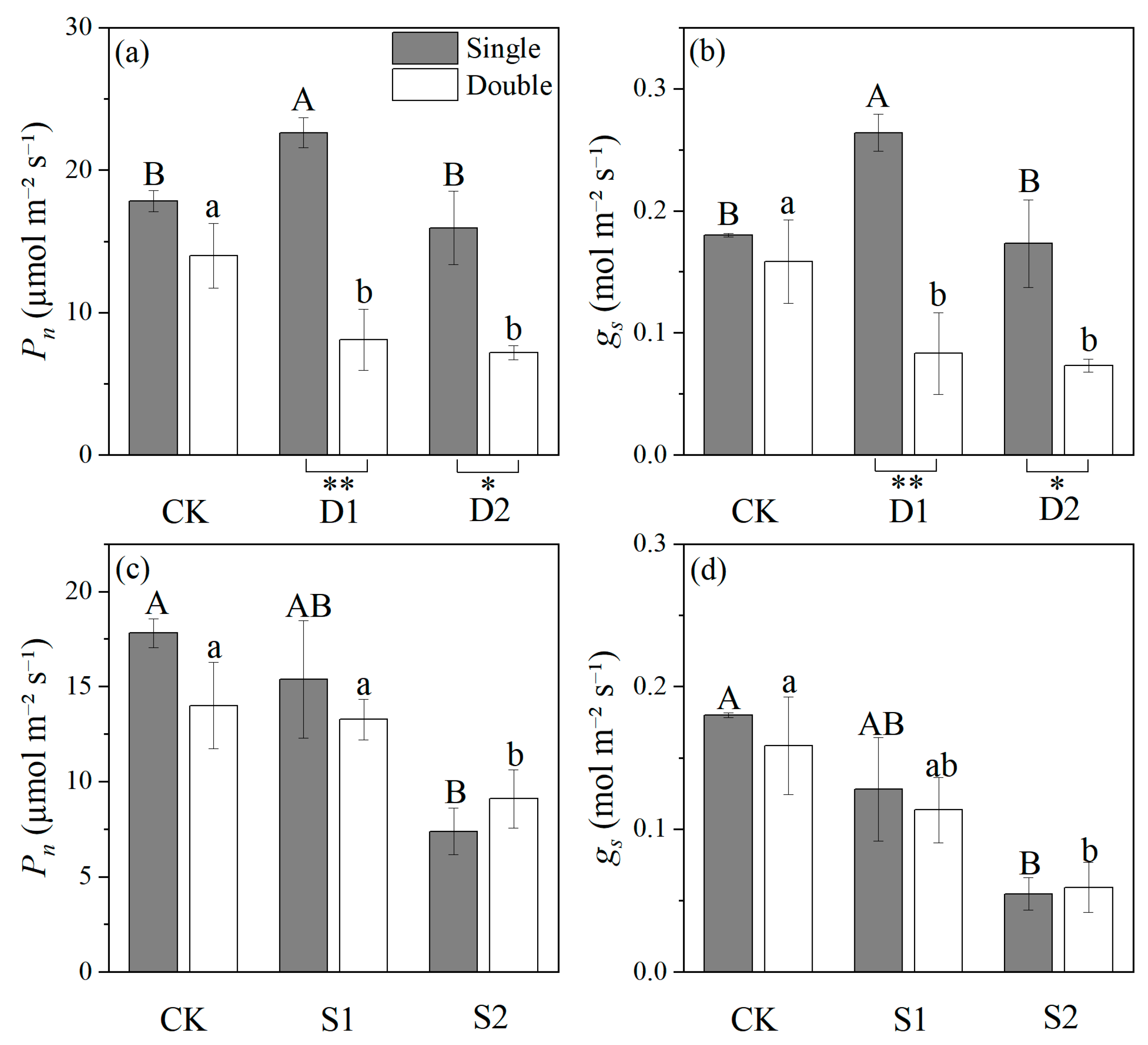

2.2. Effects of Stress on Photosynthetic Physiology

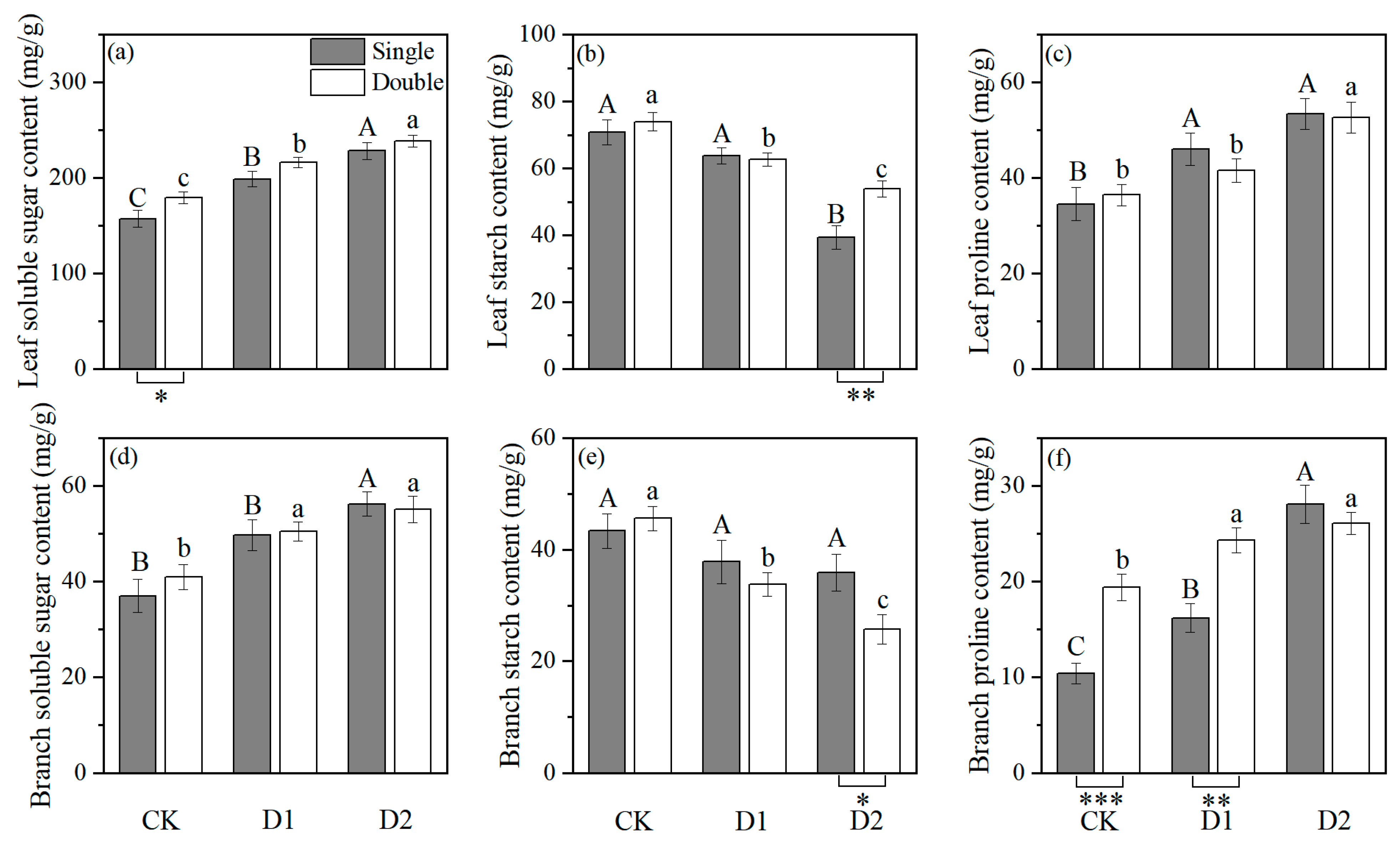

2.3. Effect of Stress on Chemical Features

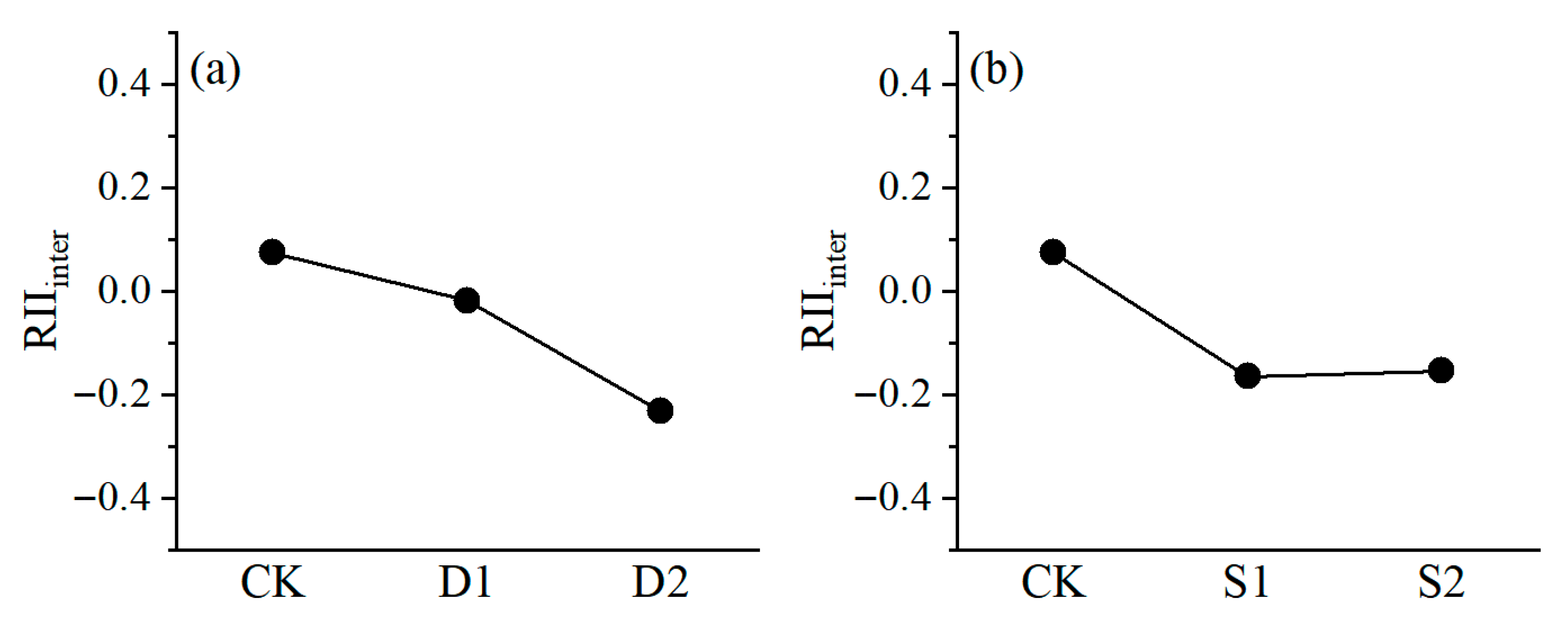

2.4. Intraspecific Relationships of P. euphratica Seedlings and Their Changes Across the Stress Gradient

3. Discussion

3.1. Morphological and Physiological Characteristics of Double-Planted P. euphratica Seedlings Responded More Significantly to Drought Stress

3.2. Morphological and Physiological Traits of Double-Planted P. euphratica Seedlings Responded Significantly Under Salt Stress

3.3. Intraspecific Competition in P. euphratica Increases with Stress Increase

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Sites and Materials

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Morphology and Biomass Determination

4.4. Measurement of Photosynthetic Physiology

4.5. Determination of Soluble Sugar and Starch

4.6. Determination of Proline

4.7. Data Processing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Xiao, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Chu, C. Advances in higher-order interactions between organisms. Biodivers. Sci. 2020, 28, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Berthomé, R.; Delavault, P.; Flutre, T.; Fréville, H.; Gibot-Leclerc, S.; Le Corre, V.; Morel, J.-B.; Moutier, N.; Munos, S. The ecologically relevant genetics of plant–plant interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, J.L. Cooperation within and among species. J. Evol. Biol. 2006, 19, 1415–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Ding, R.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Tong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Shukla, M.K. Drought, salt, and combined stresses in plants: Effects, tolerance mechanisms, and strategies. Adv. Agron. 2023, 178, 107–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sivalingam, P.; Mahajan, M.M.; Satheesh, V.; Chauhan, S.; Changal, H.; Gurjar, K.; Singh, D.; Bhan, C.; Sivalingam, A.; Marathe, A. Distinct morpho-physiological and biochemical features of arid and hyper-arid ecotypes of Ziziphus nummularia under drought suggest its higher tolerance compared with semi-arid ecotype. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 2063–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichenin, E.; Wardle, D.A.; Peltzer, D.A.; Morse, C.W.; Freschet, G.T. Contrasting effects of plant inter-and intraspecific variation on community-level trait measures along an environmental gradient. Funct. Ecol. 2013, 27, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Cui, L.-J.; Pan, X.; Li, W.; Ning, Y.; Zhou, J. Effect of nitrate supply on the facilitation between two salt-marsh plants (Suaeda salsa and Scirpus planiculmis). J. Plant Ecol. 2020, 13, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, J.; Wu, F. Response of Cucumis sativus to neighbors in a species-specific manner. Plants 2022, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, W.; Pan, S.; Jia, X.; Chu, C.; Xiao, S.; Lin, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, G. Effects of positive plant interactions on population dynamics and community structures: A review based on individual-based simulation models. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2013, 37, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertness, M.D.; Callaway, R. Positive interactions in communities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1994, 9, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, C.J.; Callaway, R.M. Re-analysis of meta-analysis: Support for the stress-gradient hypothesis. J. Ecol. 2006, 94, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, F.T.; Valladares, F.; Reynolds, J.F. Is the change of plant–plant interactions with abiotic stress predictable? A meta-analysis of field results in arid environments. J. Ecol. 2005, 93, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Bertness, M.D. Extreme stresses, niches, and positive species interactions along stress gradients. Ecology 2014, 95, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalet, R.; Le Bagousse-Pinguet, Y.; Maalouf, J.P.; Lortie, C.J. Two alternatives to the stress-gradient hypothesis at the edge of life: The collapse of facilitation and the switch from facilitation to competition. J. Veg. Sci. 2014, 25, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, J.M.; Marrs, R.H.; Potter, J.A. Interspecific and intraspecific interactions between salt marsh plants: Integrating the effects of environmental factors and density on plant performance. Oikos 2002, 96, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Luo, P.; Yang, H.; Mou, C.; Mo, L. Does stress alleviation always intensify plant-plant competition? A case study from alpine meadows with simulation of both climate warming and nitrogen deposition. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qi, M.; Lin, H.; Sun, Q.; Yang, W.; Sun, T. Productivity and tolerance reveal the shift from competition to facilitation among multiple species under multiple stressors. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 172, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tielbörger, K. Facilitation from an intraspecific perspective–stress tolerance determines facilitative effect and response in plants. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisse, E.-H.M.; Zhou, J.-J.; Fleisher, D.; Khan, Y.; Miao, L.-F.; Li, D.-D.; Tian, M.-J.; Yang, F. Intra-specific interactions disrupted the nutrient dynamics and multifactorial responses (drought and salinity) in Dalbergia odorifera in a pure planting system. Tree Physiol. 2025, 45, tpaf097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flexas, J.; DIAZ-ESPEJO, A.; Galmés, J.; Kaldenhoff, R.; Medrano, H.; RIBAS-CARBO, M. Rapid variations of mesophyll conductance in response to changes in CO2 concentration around leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 1284–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, A.; Sinha, R.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A.; Singh, A.K. Shaping the root system architecture in plants for adaptation to drought stress. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hartmann, H.; Adams, H.D.; Zhang, H.; Jin, C.; Zhao, C.; Guan, D.; Wang, A.; Yuan, F.; Wu, J. The sweet side of global change–dynamic responses of non-structural carbohydrates to drought, elevated CO2 and nitrogen fertilization in tree species. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 1706–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Pei, D.; Yu, L. Combined effects of water stress and salinity on growth, physiological, and biochemical traits in two walnut genotypes. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellouzi, H.; Zorrig, W.; Amraoui, S.; Oueslati, S.; Abdelly, C.; Rabhi, M.; Siddique, K.H.; Hessini, K. Seed priming with salicylic acid alleviates salt stress toxicity in barley by suppressing ROS accumulation and improving antioxidant defense systems, compared to halo-and gibberellin priming. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, F.; Rasheed, Y.; Asif, K.; Ashraf, H.; Maqsood, M.F.; Shahbaz, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Sardar, R.; Haider, F.U. Plant Biostimulants: Mechanisms and Applications for Enhancing Plant Resilience to Abiotic Stresses. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 6641–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, A.A.; Hey, M.H.; Couture, J.J.; Townsend, P.A.; Dalgleish, H.J. Intraspecific competition reduces plant size and quality and damage severity increases defense responses in the herbaceous perennial, Asclepias syriaca. Plant Ecol. 2020, 221, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abobatta, W.F. Plant responses and tolerance to combined salt and drought stress. In Salt and Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants: Signaling Networks and Adaptive Mechanisms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cervigón, A.I.; Gazol, A.; Sanz, V.; Camarero, J.J.; Olano, J.M. Intraspecific competition replaces interspecific facilitation as abiotic stress decreases: The shifting nature of plant–plant interactions. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013, 15, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penteriche, A.B.; Gallan, D.Z.; Silva-Filho, M.C. Is it time to shift towards multifactorial stress in biotic plant research? Plant Stress 2025, 17, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lei, J.-Q.; Zeng, F.-J.; Xu, L.-S.; Peng, S.-L.; Liu, G.-J. Effects of NaCl Treatments on Growth and Ecophysiological Characteristics of Populus euphratica. Arid Zone Res. 2015, 32, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, C.; Fahey, C.; Flory, S.L. Global change stressors alter resources and shift plant interactions from facilitation to competition over time. Ecology 2019, 100, e02859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamalero, E.; Bona, E.; Todeschini, V.; Lingua, G. Saline and arid soils: Impact on bacteria, plants, and their interaction. Biology 2020, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.Y.; Si, J.H.; Feng, Q.; Deo, R.C.; Yu, T.F.; Li, P.D. Physiological response to salinity stress and tolerance mechanics of Populus euphratica. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleamotu, M.; McCurdy, D.W.; Collings, D.A. Phi thickenings in roots: Novel secondary wall structures responsive to biotic and abiotic stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 4631–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Han, Q.; Duan, B.; Korpelainen, H.; Li, C. Sex-specific competition differently regulates ecophysiological responses and phytoremediation of Populus cathayana under Pb stress. Plant Soil 2017, 421, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Huang, Z.; Tang, S.; Korpelainen, H.; Li, C. Populus euphratica males exhibit stronger drought and salt stress resistance than females. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 205, 105114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olechowicz, J.; Chomontowski, C.; Olechowicz, P.; Pietkiewicz, S.; Jajoo, A.; Kalaji, M. Impact of intraspecific competition on photosynthetic apparatus efficiency in potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Su, J.; Tian, Q.; Shen, Y. Contrasting strategies of nitrogen absorption and utilization in alfalfa plants under different water stress. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Tang, S.; Guo, C.; Korpelainen, H.; Li, C. Differences in ecophysiological responses of Populus euphratica females and males exposed to salinity and alkali stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 198, 107707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R.W.; Maestre, F.T.; Callaway, R.M.; Lortie, C.L.; Cavieres, L.A.; Kunstler, G.; Liancourt, P.; Tielbörger, K.; Travis, J.M.; Anthelme, F. Facilitation in plant communities: The past, the present, and the future. J. Ecol. 2007, 96, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado, R.; Bråthen, K.A.; Pugnaire, F.I. Mutual positive effects between shrubs in an arid ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Guo, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Guo, W.; Tian, Q. Phenotypic plasticity variations in Phragmites australis under different plant–plant interactions influenced by salinity. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, X.; Imin, B.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Kahaer, Y. Effect of the competition mechanism of between co-dominant species on the ecological characteristics of Populus euphratica under a water gradient in a desert oasis. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, M.; Zhao, X.; Liu, M.; Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Lu, Z.; Han, Z. Combined transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis revealed the salt tolerance mechanism of Populus talassica × Populus euphratica. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestre, F.T.; Callaway, R.M.; Valladares, F.; Lortie, C.J. Refining the stress-gradient hypothesis for competition and facilitation in plant communities. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Bertness, M.D.; Altieri, A.H. Global shifts towards positive species interactions with increasing environmental stress. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, N.J.; Adler, P.B.; Godoy, O.; James, E.C.; Fuller, S.; Levine, J.M. Community assembly, coexistence and the environmental filtering metaphor. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hardrath, A.; Jin, H.; Van Kleunen, M. Increases in multiple resources promote competitive ability of naturalized non-native plants. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, P.; He, J.; Li, P.; Liang, Y. The spatial pattern of Populus euphratica competition based on competitive exclusion theory. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1276489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, G.; Feng, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Du, W.; Lei, Y.; Xiong, S.; Zhi, X. Response of cotton fruit growth, intraspecific competition and yield to plant density. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 114, 125991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schamp, B.S.; Aarssen, L.W. Plant species size and density-dependent effects on growth and survival. J. Veg. Sci. 2014, 25, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Yu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Korpelainen, H.; Niinemets, Ü.; Li, C. Nitrogen-controlled intra-and interspecific competition between Populus purdomii and Salix rehderiana drive primary succession in the Gongga Mountain glacier retreat area. Tree Physiol. 2017, 37, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.; Teare, I. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, H.B. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) dan aplikasinya dengan SPSS. J. Kesehat. Masy. Andalas 2009, 3, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FN | FD | FS | FN*D | FN*S | |

| Height difference | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.002 | 0.072 | 0.192 |

| Base diameter difference | 0.156 | 0.155 | 0.003 | 0.435 | 0.714 |

| Above-ground biomass | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.746 | 0.200 |

| Below-ground biomass | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.725 | 0.179 |

| Total biomass | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.945 | 0.183 |

| R/S ratio | 0.904 | 0.034 | 0.002 | 0.153 | 0.893 |

| Pn | 0.011 | 0.060 | 0.004 | 0.144 | 0.290 |

| gs | 0.020 | 0.086 | 0.021 | 0.159 | 0.698 |

| Leaf soluble sugar content | 0.094 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.620 | 0.301 |

| Branch soluble sugar content | 0.554 | 0.059 | 0.091 | 0.742 | 0.505 |

| Leaf starch content | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.832 |

| Branch starch content | 0.009 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 0.315 | 0.878 |

| Leaf proline content | 0.888 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.581 | 0.004 |

| Branch proline content | 0.524 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.815 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.-H.; Zhang, X.-N.; Zhou, S.-F.; Li, H.-X.; Chen, Y.-F. Competitive Interactions Among Populus euphratica Seedlings Intensify Under Drought and Salt Stresses. Plants 2025, 14, 3842. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243842

Li X-H, Zhang X-N, Zhou S-F, Li H-X, Chen Y-F. Competitive Interactions Among Populus euphratica Seedlings Intensify Under Drought and Salt Stresses. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3842. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243842

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiao-Hui, Xue-Ni Zhang, Shuang-Fu Zhou, Hui-Xia Li, and Yu-Fei Chen. 2025. "Competitive Interactions Among Populus euphratica Seedlings Intensify Under Drought and Salt Stresses" Plants 14, no. 24: 3842. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243842

APA StyleLi, X.-H., Zhang, X.-N., Zhou, S.-F., Li, H.-X., & Chen, Y.-F. (2025). Competitive Interactions Among Populus euphratica Seedlings Intensify Under Drought and Salt Stresses. Plants, 14(24), 3842. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243842