Effects of Cover Crops on Water Use Efficiency in Orchard Systems in the Danjiangkou Catchment, Central China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

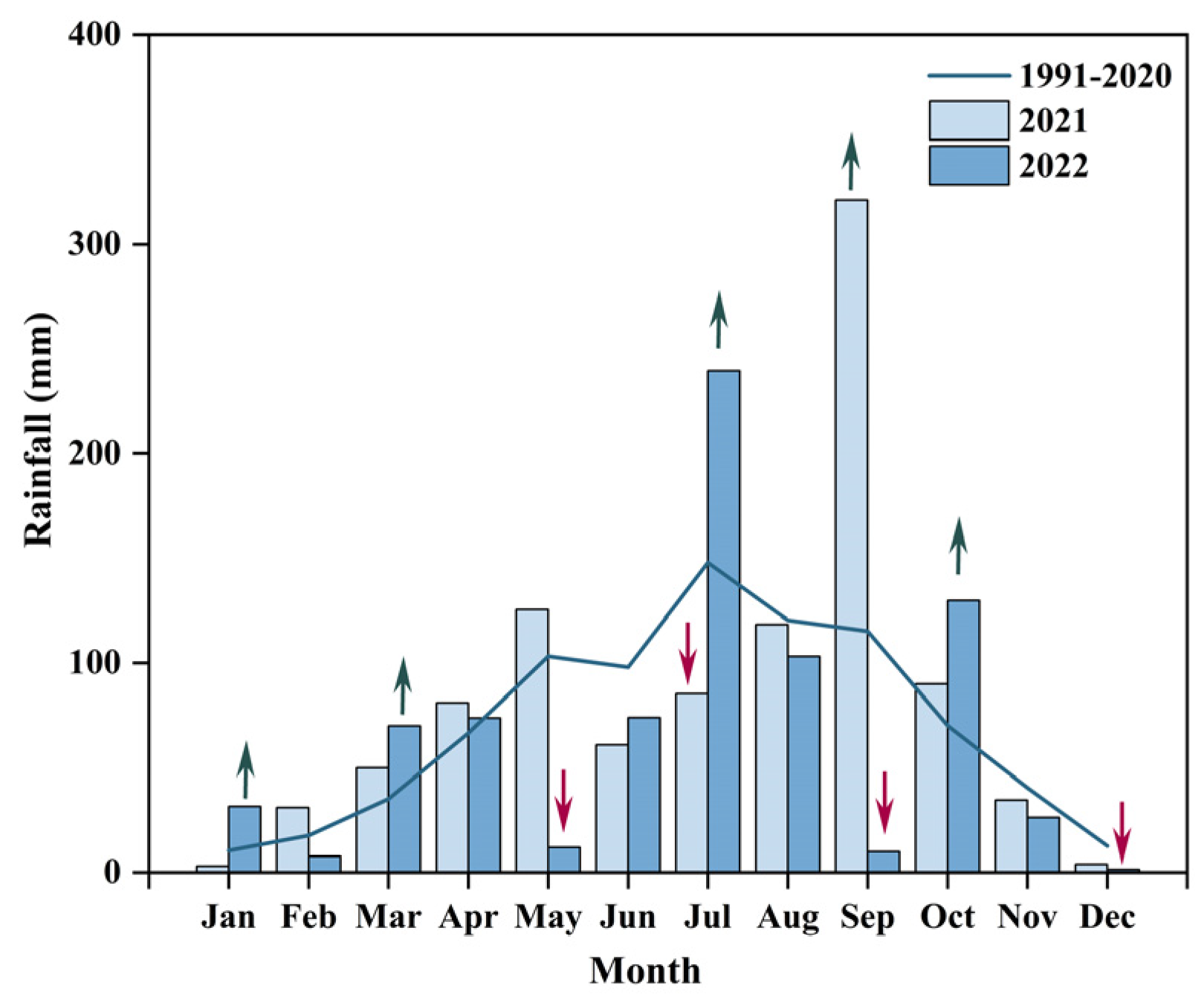

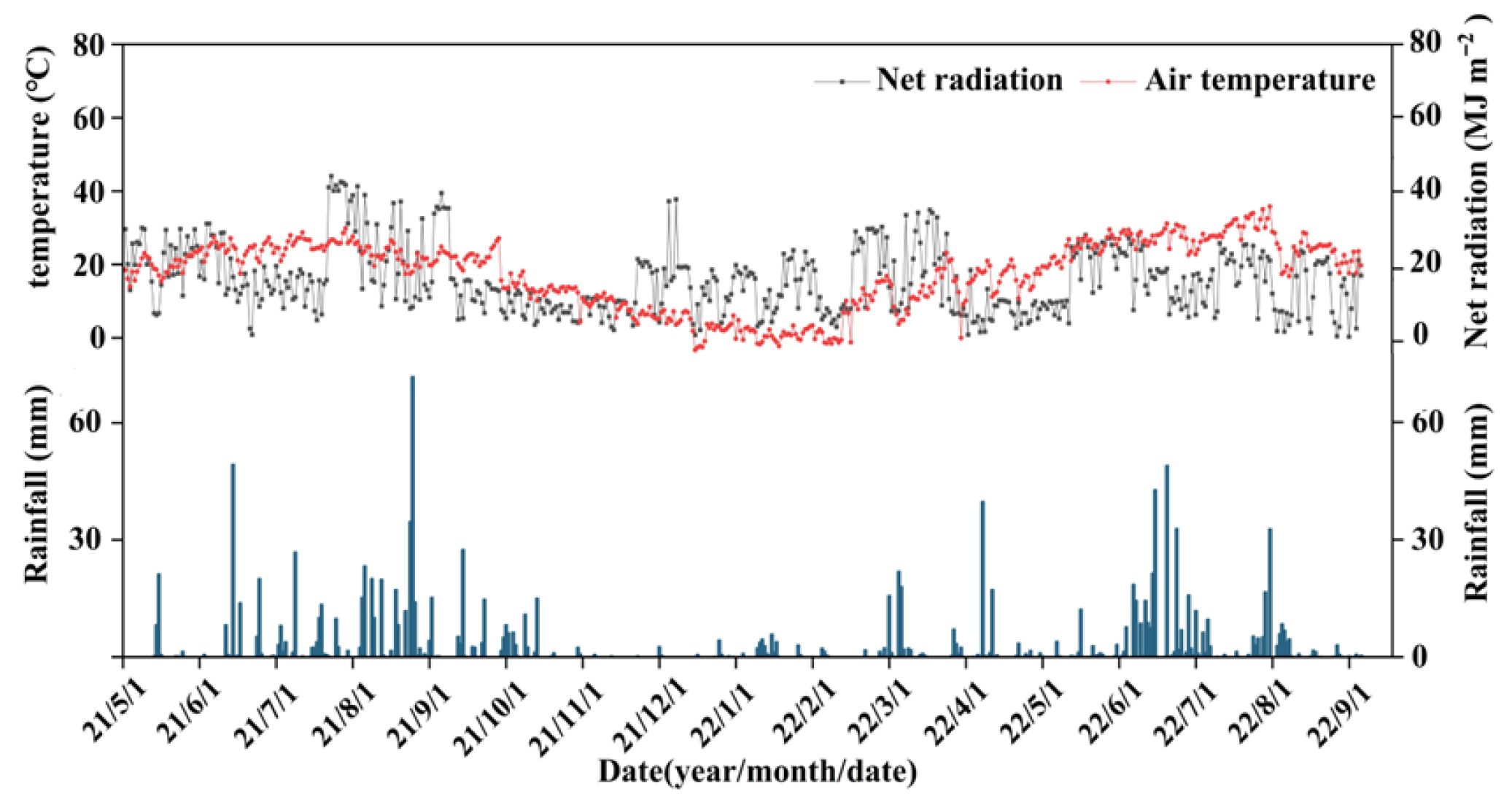

2.1. Variations in Environmental Factors

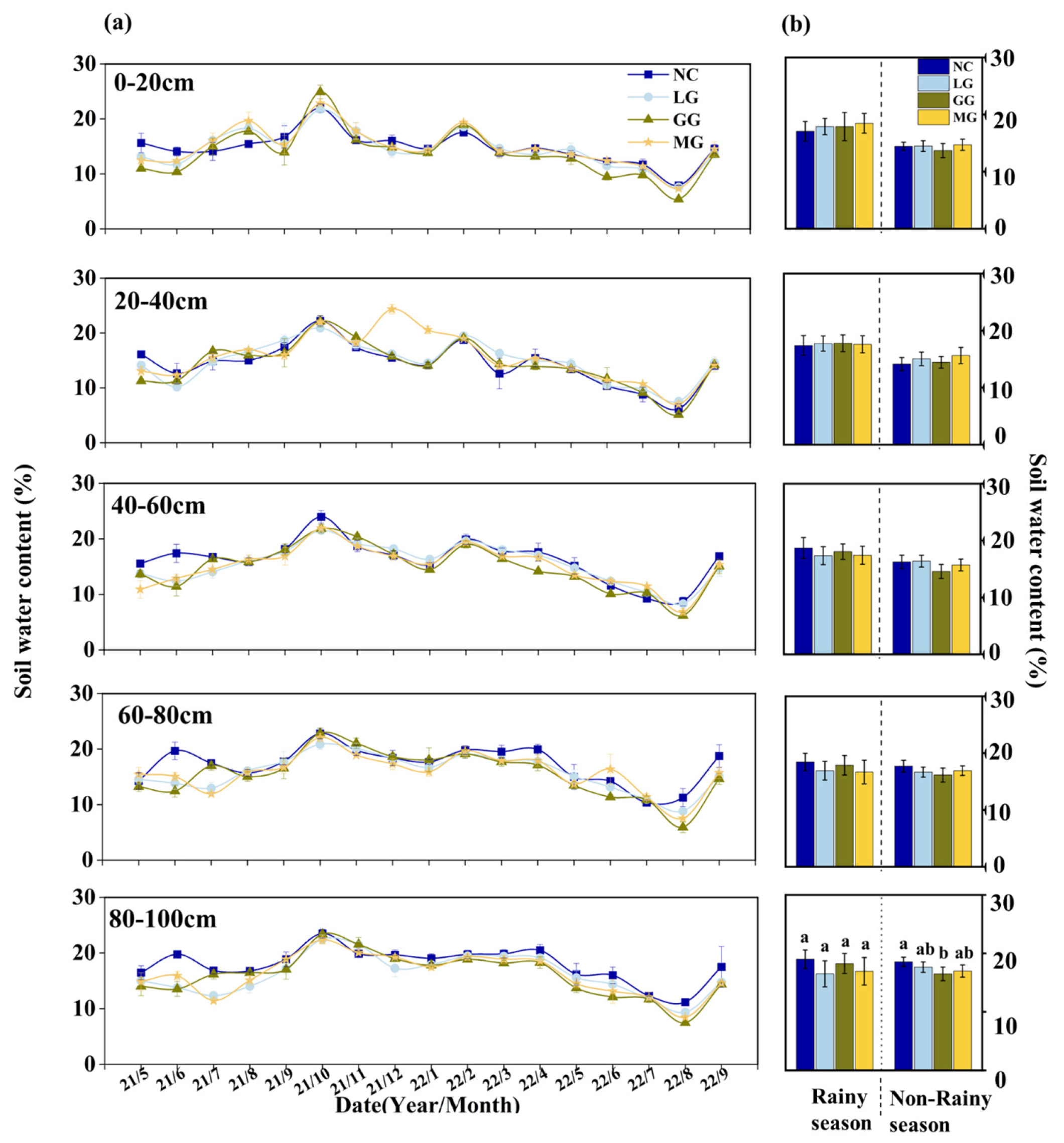

2.2. Soil Water Content

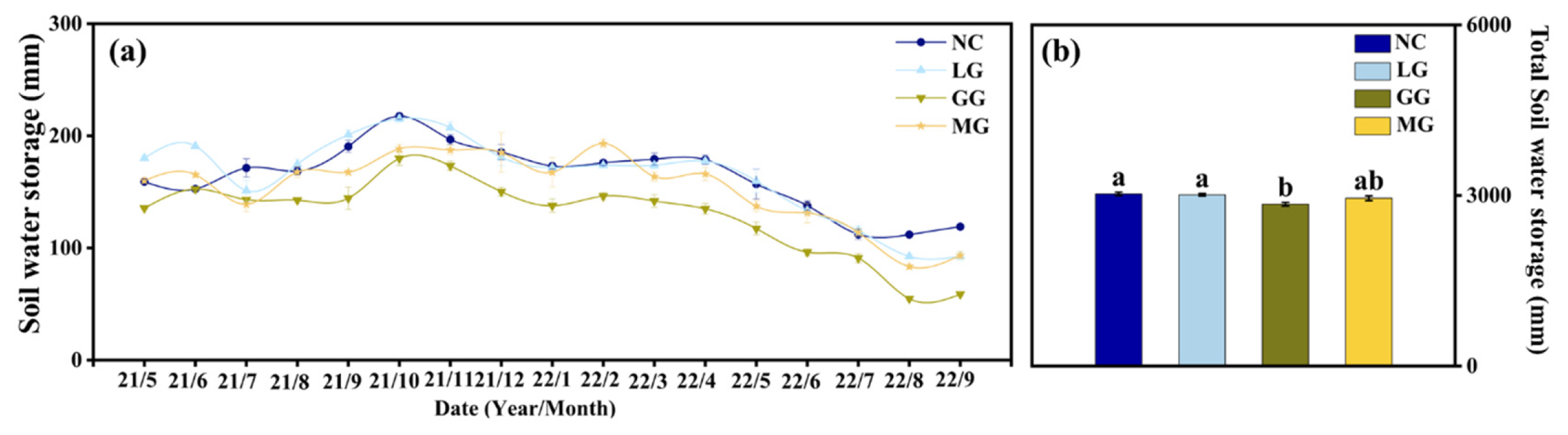

2.3. Soil Water Storage

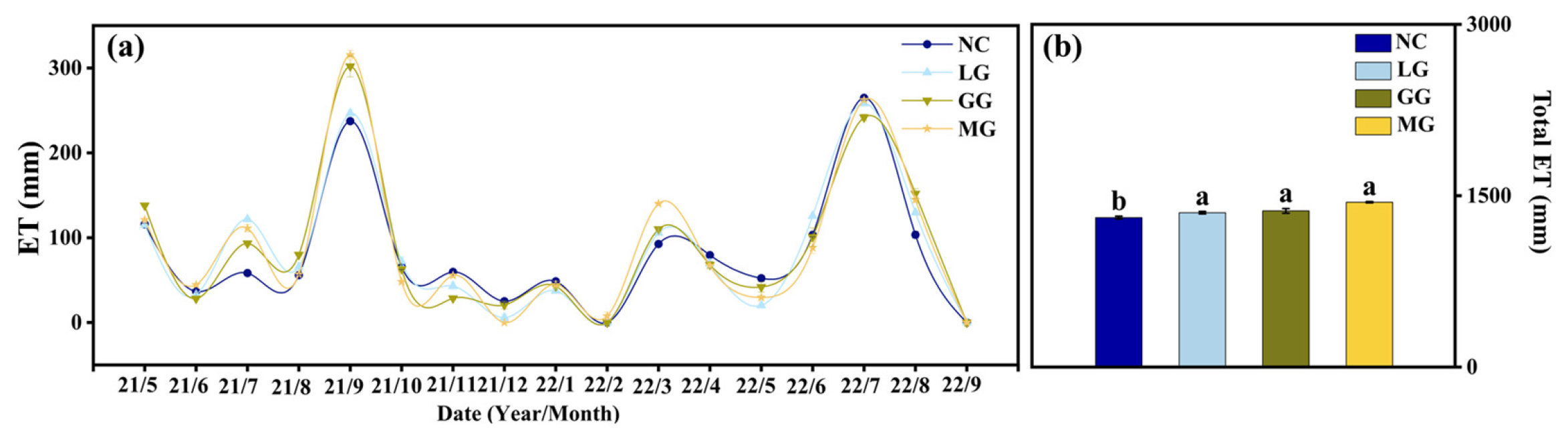

2.4. Dynamics of ET

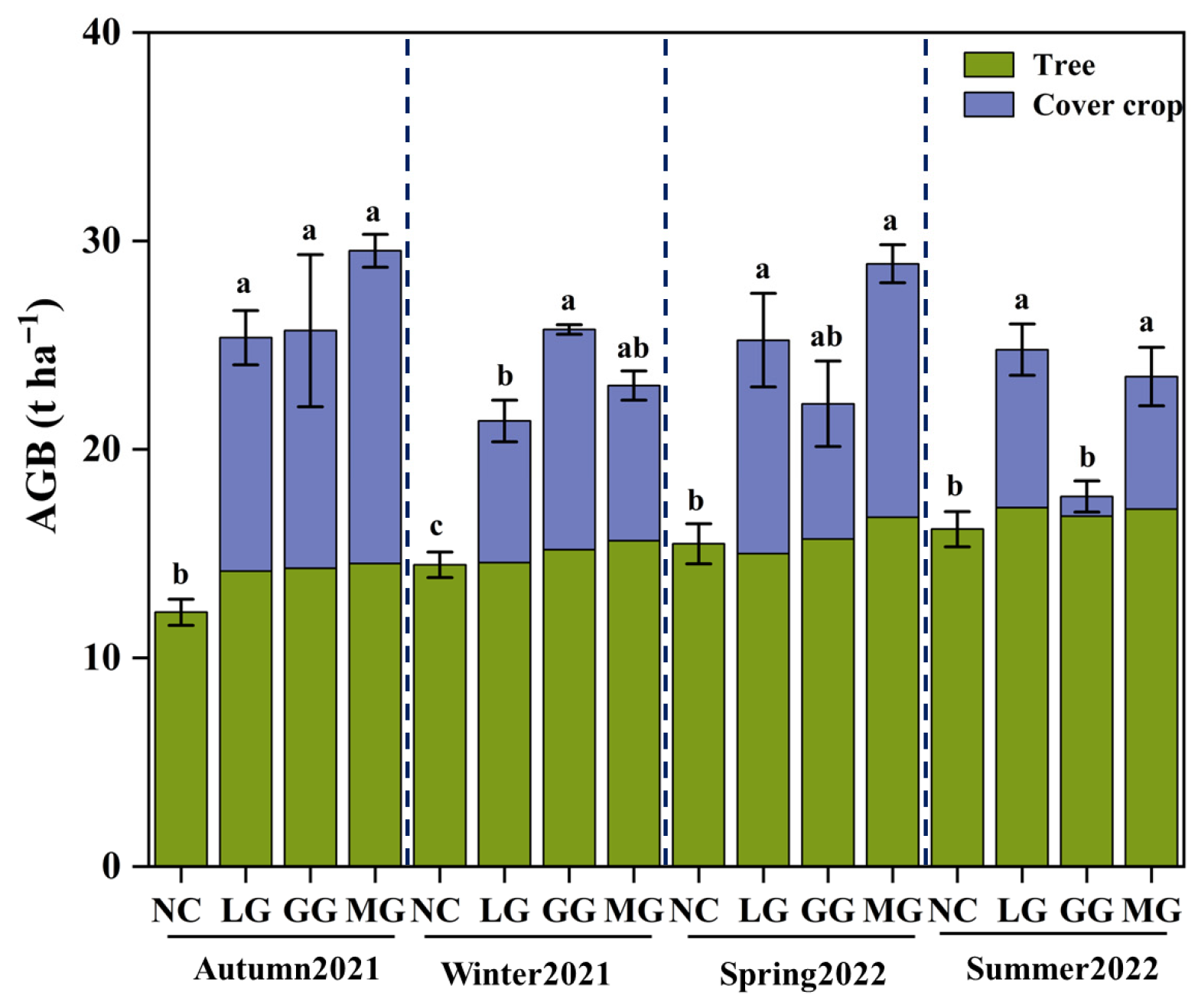

2.5. Biomass Dynamics of Fruit Trees and Cover Crops

2.6. Seasona Variation in Water Use Efficiency

2.7. Drivers of SWC, ET, and WUE

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Cover Crops on Soil Water Dynamics

3.2. Regulatory Mechanisms of Cover Crops on Evapotranspiration Patterns

3.3. Improvement of Water Use Efficiency by Cover Crops

3.4. Uncertainty in the Effects of Orchard Cover Crops on Water Indicators

3.5. Implications for Management Practices

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Site and Design

- NC: No cover crop (bare soil with manual weed removal)

- LG: Legume grass (Medicago sativa, 12 kg ha−1 seeding rate)

- GG: Gramineae grass (Festuca arundinacea, 18 kg ha−1 seeding rate)

- MG: Mixture Grass (MG, Medicago sativa and Festuca arundinacea)

4.2. Site Characteristics and Climate

4.3. Water Balance Measurements and Calculations

4.3.1. Soil Moisture Monitoring and Storage Calculation

4.3.2. Evapotranspiration Components

4.3.3. Water Use Efficiency

4.4. Biomass Measurements and Calculations

4.4.1. Cover Crop Biomass

4.4.2. Tree Biomass Estimation

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, S.Z.; Zhao, L.; Liang, C.; Hu, X.T.; Wang, Y.S.; Gong, D.Z.; Zheng, S.S.; Huang, Y.W.; He, Q.Y.; Cui, N.B. Leaf-and ecosystem-scale water use efficiency and their controlling factors of a kiwifruit orchard in the humid region of Southwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, G.P.; Wu, J.J.; Wang, Q.F.; Lei, T.J.; He, B.; Li, X.H.; Mo, X.Y.; Luo, H.Y.; Zhou, H.K.; Liu, D.C. Agricultural drought hazard analysis during 1980-2008: A global perspective. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, G.P.; Zhao, X.N.; Gao, X.D.; Wang, S.F.; Pan, Y.H. Seasonal water use patterns of rainfed jujube trees in stands of different ages under semiarid Plantations in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.M.; Petrie, M.D.; Chen, H.; Zeng, F.J.; Ahmed, Z.; Sun, X.B. Effects of groundwater and seasonal streamflow on the symbiotic nitrogen fixation of deep-rooted legumes in a dryland floodplain. Geoderma 2023, 434, 116490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.T.; Roderick, M.L.; Guo, H.; Miralles, D.G.; Zhang, L.; Fatichi, S.; Luo, X.Z.; Zhang, Y.Q.; McVicar, T.R.; Tu, Z.Y.; et al. Evapotranspiration on a greening Earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S.M.; Ducharne, A.; Polcher, J. The impact of global land-cover change on the terrestrial water cycle. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Y.; Chen, P.; Wang, K.L.; Zhang, R.Q.; Yuan, X.L.; Ge, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.Q.; Li, Z.G. Gramineae-legumes mixed planting effectively reduces soil and nutrient loss in orchards. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.L.; Liu, Y.B.; Chen, H.S.; Ju, W.M.; Xu, C.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.L.; Yu, M. Causes for the increases in both evapotranspiration and water yield over vegetated mainland China during the last two decades. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 324, 109118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.K.; Wu, Y.H.; Cao, Q.; Shen, Y.Y.; Zhang, B.Q. Modeling the coupling processes of evapotranspiration and soil water balance in agroforestry systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 250, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribouillois, H.; Constantin, J.; Justes, E. Cover crops mitigate direct greenhouse gases balance but reduce drainage under climate change scenarios in temperate climate with dry summers. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 2513–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wang, Y.L.; Lyu, H.Q.; Fan, Z.L.; Hu, F.L.; He, W.; Yin, W.; Zhao, C.; Chai, Q.; Yu, A.Z. No-tillage mulch with leguminous green manure retention reduces soil evaporation and increases yield and water productivity of maize. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 290, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Sainju, U.M.; Liu, R.; Tan, G.Y.; Wen, M.M.; Zhao, J.; Pu, J.L.; Feng, J.R.; Wang, J. Winter legume cover crop with adequate nitrogen fertilization enhance dryland maize yield and water-use efficiency. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 306, 109209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.J.; Parvin, S.; McInnes, J.; van Zwieten, L.; Gibson, A.J.; Kearney, L.J.; Rose, M.T. Summer cover crop and temporary legume-cereal intercrop effects on soil microbial indicators, soil water and cash crop yields in a semi-arid environment. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, A.; Birru, G.; Tadesse, T.; Schmer, M.R.; Awada, T.; Jin, V.L.; Wardlow, B.; Iqbal, J.; Freidenreich, A.; Kharel, T.; et al. Optimizing Cover Crop Management in Eastern Nebraska: Insights from Crop Simulation Modeling. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basche, A.D.; Kaspar, T.C.; Archontoulis, S.V.; Jaynes, D.B.; Sauer, T.J.; Parkin, T.B.; Miguez, F.E. Soil water improvements with the long-term use of a winter rye cover crop. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 172, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, F.M.; Jing, Y.S.; Liu, Y.B.; Sun, G. Response of evapotranspiration to changes in land use and land cover and climate in China during 2001–2013. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 596, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.H.; Sainju, U.M.; Ghimire, R.; Zhao, F.Z. A meta-analysis on cover crop impact on soil water storage, succeeding crop yield, and water-use efficiency. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 256, 107085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadarrama-Escobar, L.M.; Hunt, J.; Gurung, A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Shabala, S.; Camino, C.; Hernandez, P.; Pourkheirandish, M. Back to the future for drought tolerance. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubvumba, P.; DeLaune, P.B.; Hons, F.M. Soil water dynamics under a warm-season cover crop mixture in continuous wheat. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 206, 104823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Lee, J.; Yin, X.H.; Tyler, D.D.; Saxton, A.M. Thirty-four years of no-tillage and cover crops improve soil quality and increase cotton yield in Alfisols, Southeastern USA. Geoderma 2019, 337, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler-Cole, K.; Elmore, R.W.; Blanco-Canqui, H.; Francis, C.A.; Shapiro, C.A.; Proctor, C.A.; Ruis, S.J.; Irmak, S.; Heeren, D.M. Cover crop planting practices determine their performance in the US Corn Belt. Agron. J. 2023, 115, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudahe, K.; Allen, S.C.; Djaman, K. Critical review of the impact of cover crops on soil properties. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2022, 10, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, S.I.; Reixachs, C.; Torti, M.J.; Beribe, M.J.; Giannini, A.P. Contrasting effects of soil type and use of cover crops on nitrogen and phosphorus leaching in agricultural systems of the Argentinean Pampas. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 364, 108897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Nie, J.Y.; Yang, J.; Ren, J.H.; van der Werf, W.; Evers, J.B.; Zhang, J.; Su, Z.C.; Zhang, L.Z. A lack of complementarity for water acquisition limits yield advantage of oats/vetch intercropping in a semi-arid condition. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 225, 105778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Qiao, Y.G.; She, W.W.; Miao, C.; Qin, S.G.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.Q. Interspecific competition alters water use patterns of coexisting plants in a desert ecosystem. Plant Soil 2024, 495, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.P.; Fang, L.C.; Shi, Z.H.; Deng, L.; Tan, W.F. Spatio-temporal dynamics of soil moisture driven by ‘Grain for Green’ program on the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 269, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Zha, T.S.; Black, A.; Jia, X.; Jassal, R.S.; Liu, P.; Tian, Y.; Jin, C.; Yang, R.Z.; Zhang, F.; et al. Stronger control of surface conductance by soil water content than vapor pressure deficit regulates evapotranspiration in an urban forest in Beijing, 2012–2022. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 344, 109815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.J.; Zhang, X.P.; Wang, L.; Wang, R.; Luo, Z.D.; He, X.G.; Rao, Z.G. Water stable isotope characteristics and water use strategies of co-occurring plants in ecological and economic forests in subtropical monsoon regions. J. Hydrol. 2023, 621, 129565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.X.; Su, Z.C.; Du, G.J.; Bai, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, R.N.; Nie, J.Y.; Sun, T.R.; Feng, C.; et al. Root plasticity and interspecific complementarity improve yields and water use efficiency of maize/soybean intercropping in a water-limited condition. Field Crops Res. 2022, 282, 108523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Xie, J.H.; Luo, Z.Z.; Niu, Y.N.; Coulter, J.A.; Zhang, R.Z.; Li, L.L. Forage yield, water use efficiency, and soil fertility response to alfalfa growing age in the semiarid Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, C.P.; Bueno, C.G.; Toussaint, A.; Träger, S.; Díaz, S.; Moora, M.; Munson, A.D.; Pärtel, M.; Zobel, M.; Tamme, R. Fine-root traits in the global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 2021, 597, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celette, F.; Gary, C. Dynamics of water and nitrogen stress along the grapevine cycle as affected by cover cropping. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 45, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.K.; Wu, G.; Mo, P.; Chen, S.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, H.L.A.; Wen, T.; Guo, X.; Fan, G.Q. The combined effects of maize straw mulch and no-tillage on grain yield and water and nitrogen use efficiency of dry-land winter wheat Triticum aestivu L.). Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 197, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.C.; Kemanian, A.R.; Mortensen, D.A. Cover crop effects on maize drought stress and yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 311, 107294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeki, K.; Miyazawa, Y.; Sugiura, D. Rapid stomatal closure contributes to higher water use efficiency in major C-4 compared to C-3 Poaceae crops. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z.; Manevski, K.; Liu, F.L.; Andersen, M.N. Biomass accumulation and water use efficiency of faba bean-ryegrass intercropping system on sandy soil amended with biochar under reduced irrigation regimes. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 273, 107905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, M.M.; Chen, R.J.; Jing, Y.; Wu, F.B.; Chen, Z.H.; Tissue, D.; Jiang, H.J.; Wang, Y.Z. Guard cell and subsidiary cell sizes are key determinants for stomatal kinetics and drought adaptation in cereal crops. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 2479–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.W.; Dang, K.; Lv, S.M.; Zhao, G.; Tian, L.X.; Luo, Y.; Feng, B.L. Interspecific root interactions and water-use efficiency of intercropped proso millet and mung bean. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 115, 126034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Dold, C. Water-Use Efficiency: Advances and Challenges in a Changing Climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, S.J.; Li, S.Q.; Chen, X.P.; Chen, F. Growth and development of maize (Zea mays L.) in response to different field water management practices: Resource capture and use efficiency. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.Q.; Chen, F.; Yang, S.J.; Chen, X.P. Soil water dynamics and water use efficiency in spring maize (Zea mays L.) fields subjected to different water management practices on the Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lv, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Ma, H.; Liu, Z. Analysis of Potential Water Source Differences and Utilization Strategies of Desert Plants in Arid Regions. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2019, 28, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi, Z.; Merlin, O.; Le Dantec, V.; Khabba, S.; Mordelet, P.; Er-Raki, S.; Amazirh, A.; Olivera-Guerra, L.; Hssaine, B.A.; Simonneaux, V.; et al. Partitioning evapotranspiration of a drip-irrigated wheat crop: Inter-comparing eddy covariance-, sap flow-, lysimeter- and FAO-based methods. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 265, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Meng, X.J.; Singh, A.K.; Wang, P.Y.; Song, L.; Zakari, S.; Liu, W.J. Intercrops improve surface water availability in rubber-based agroforestry systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 298, 106937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deines, J.M.; Guan, K.Y.; Lopez, B.; Zhou, Q.; White, C.S.; Wang, S.; Lobell, D.B. Recent cover crop adoption is associated with small maize and soybean yield losses in the United States. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Wang, Y.K.; Zhang, X.; Wei, X.G.; Duan, X.W.; Muhammad, S. Understory mowing controls soil drying in a rainfed jujube agroforestry system in the Loess Plateau. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 246, 106703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Parks, S.A.; Hegewisch, K.C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steduto, P.; Hsiao, T.C.; Raes, D.; Fereres, E. AquaCrop-The FAO Crop Model to Simulate Yield Response to Water: I. Concepts and Underlying Principles. Agron. J. 2009, 101, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, G.; Gorné, L.D.; Zeballos, S.R.; Lipoma, M.L.; Gatica, G.; Kowaljow, E.; Whitworth-Hulse, J.I.; Cuchietti, A.; Poca, M.; Pestoni, S.; et al. Developing allometric models to predict the individual aboveground biomass of shrubs worldwide. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 28, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Depth (cm) | NC | LG | GG | MG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | Lag | Correlation | Lag | Correlation | Lag | Correlation | Lag | |

| 0–20 | −0.07 | 6 | −0.14 | 0 | −0.18 | 0 | −0.14 | 0 |

| 20–40 | −0.12 | 6 | −0.08 | 6 | −0.20 | 0 | −0.31 | 0 |

| 40–60 | −0.24 | 0 | −0.22 | 0 | −0.12 | 0 | −0.22 | 6 |

| 60–80 | −0.38 | 0 | −0.24 | 0 | −0.25 | 6 | −0.22 | 0 |

| 80–100 | −0.30 | 0 | −0.29 | 6 | −0.22 | 0 | −0.20 | 6 |

| Time | NC (g cm−3) | LG (g cm−3) | GG (g cm−3) | MG (g cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.06 | 1.00 ± 0.23 | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 1.05 ± 0.08 |

| 21.09 | 1.29 ± 0.07 | 1.15 ± 0.03 | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 1.27 ± 0.03 |

| 21.12 | 1.18 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.05 | 1.17 ± 0.04 | 1.12 ± 0.03 |

| 22.03 | 1.19 ± 0.08 | 1.22 ± 0.03 | 1.13 ± 0.02 | 1.07 ± 0.09 |

| 22.06 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 1.14 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 1.06 ± 0.05 |

| 22.09 | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 1.35 ± 0.09 | 1.30 ± 0.02 | 1.28 ± 0.05 |

| Sampling Time | NC (mm) | LG (mm) | GG (mm) | MG (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.05 | 5.74 | 2.44 | 2.47 | 2.29 |

| 21.06 | 22.51 | 12.32 | 13.67 | 10.87 |

| 21.07 | 5.70 | 2.48 | 2.43 | 2.29 |

| 21.08 | 40.60 | 26.60 | 26.59 | 18.58 |

| 21.09 | 11.50 | 7.16 | 10.38 | 7.30 |

| 21.10 | 6.35 | 2.80 | 2.32 | 2.24 |

| 21.11 | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.13 |

| 21.12 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| 22.01 | 0.47 | 0.19 | 2.00 | 0.11 |

| 22.02 | 0.38 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.10 |

| 22.03 | 4.00 | 1.49 | 2.02 | 1.53 |

| 22.04 | 4.26 | 1.52 | 2.71 | 1.58 |

| 22.05 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.17 |

| 22.06 | 4.35 | 1.49 | 2.49 | 2.02 |

| 22.07 | 25.34 | 16.79 | 17.42 | 15.21 |

| 22.08 | 9.24 | 6.78 | 7.82 | 4.79 |

| 22.09 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| Treatment | Shoot Length (cm) | Stem Diameter (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021.09 | 2022.09 | 2021.09 | 2022.09 | |

| NC | 24.88 ± 4.21 a | 33.65 ± 1.74 a | 6.30 ± 0.39 a | 11.40 ± 0.52 a |

| LG | 19.35 ± 4.38 a | 34.15 ± 1.47 a | 5.28 ± 0.42 a | 10.03 ± 0.48 a |

| GG | 19.90 ± 3.07 a | 30.92 ± 1.80 a | 5.86 ± 0.18 a | 10.58 ± 0.66 a |

| MG | 19.38 ± 2.73 a | 29.06 ± 2.00 a | 5.59 ± 0.36 a | 9.57 ± 0.30 a |

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficient (B) | Standard Error | Standardized Coefficient (β) | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 21.09 | 1.16 | - | 18.18 | <0.001 |

| Temperature (℃) | −0.28 | 0.02 | −0.67 | −13.20 | <0.001 |

| Radiation (MJ m−2) | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 3.21 | 0.001 |

| Wind speed (m s−1) | −3.41 | 1.35 | −0.13 | −2.53 | 0.012 |

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficient (B) | Standard Error | Standardized Coefficient (β) | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 46.24 | 38.59 | - | −1.20 | 0.235 |

| Rainfall (mm) | 0.87 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 10.82 | <0.001 |

| Temperature (°C) | 1.43 | 0.77 | 0.16 | 1.86 | 0.067 |

| Radiation (MJ m−2) | −2.32 | 0.99 | −0.17 | −2.35 | 0.020 |

| Wind speed (m s−1) | 122.85 | 44.56 | 0.21 | 2.76 | 0.008 |

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficient (B) | Standard Error | Standardized Coefficient (β) | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.20 | 0.07 | - | −2.88 | 0.006 |

| Humidity (KPa) | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.55 | 4.44 | <0.001 |

| Rainfall (mm) | −1.00 × 10−3 | −1.00 × 10−3 | −0.29 | −2.32 | 0.025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Chen, P.; Jing, X.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, R.; Yuan, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z. Effects of Cover Crops on Water Use Efficiency in Orchard Systems in the Danjiangkou Catchment, Central China. Plants 2025, 14, 3729. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243729

Li L, Chen P, Jing X, Lyu C, Zhang R, Yuan X, Li Q, Liu Y, Zhang X, Li Z. Effects of Cover Crops on Water Use Efficiency in Orchard Systems in the Danjiangkou Catchment, Central China. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3729. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243729

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Linyang, Peng Chen, Xinxin Jing, Chenhao Lyu, Runqin Zhang, Xiaoliang Yuan, Qian Li, Yi Liu, Xiaoquan Zhang, and Zhiguo Li. 2025. "Effects of Cover Crops on Water Use Efficiency in Orchard Systems in the Danjiangkou Catchment, Central China" Plants 14, no. 24: 3729. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243729

APA StyleLi, L., Chen, P., Jing, X., Lyu, C., Zhang, R., Yuan, X., Li, Q., Liu, Y., Zhang, X., & Li, Z. (2025). Effects of Cover Crops on Water Use Efficiency in Orchard Systems in the Danjiangkou Catchment, Central China. Plants, 14(24), 3729. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243729