Optimizing Water and Nitrogen Management Strategies to Unlock the Production Potential for Onion in the Hexi Corridor of China: Insights from Economic Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Analysis

2.1. The Effect of Water–Nitrogen Interaction on Onion Quality

2.2. The Effect of Water–Nitrogen Interaction on Onion Yield

2.3. The Effect of Water–Nitrogen Interaction on Onion Water–Nitrogen Use Efficiency

2.4. The Effect of Water–Nitrogen Interaction on Onion Economic Benefits

2.5. Water and Nitrogen Coupling Model and Scheme Optimization for Drip Irrigation Under Mulch

2.5.1. Water and Nitrogen Coupling Model Equation

2.5.2. Model Validation

2.5.3. Single-Factor Effect Analysis

2.5.4. Single-Factor Marginal Effect Analysis

2.5.5. Analysis of the Interaction Effect of Water and Nitrogen Factors

2.5.6. Optimization of Combination Schemes

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Water–Nitrogen Interactions on Onion Quality

3.2. Effects of Water–Nitrogen Interactions on Onion Yield and Water–Nitrogen Use Efficiency

3.3. Effects of Water–Nitrogen Interactions on Onion’s Economic Benefits

4. Materials and Methods

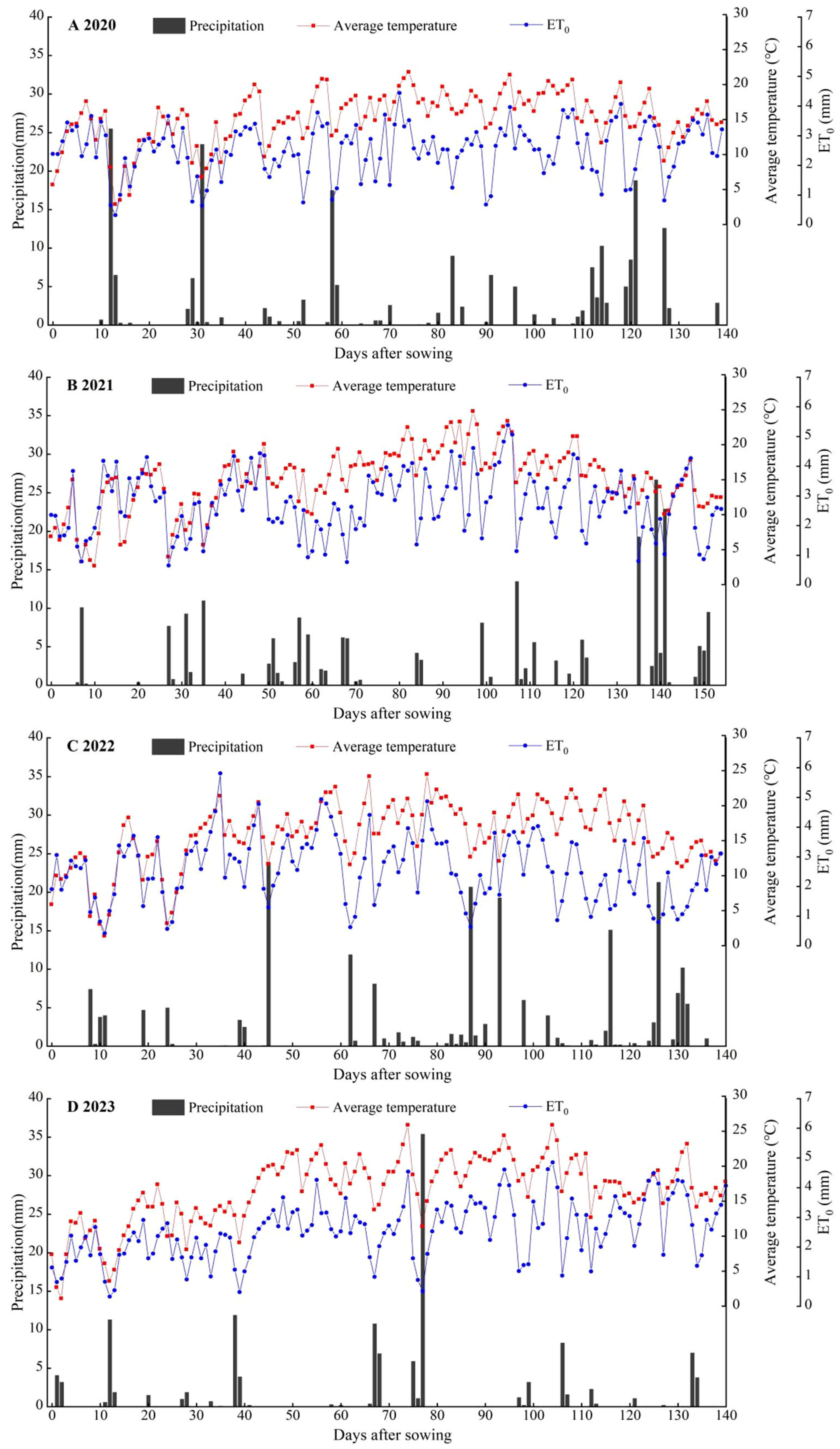

4.1. Experimental Site Profile

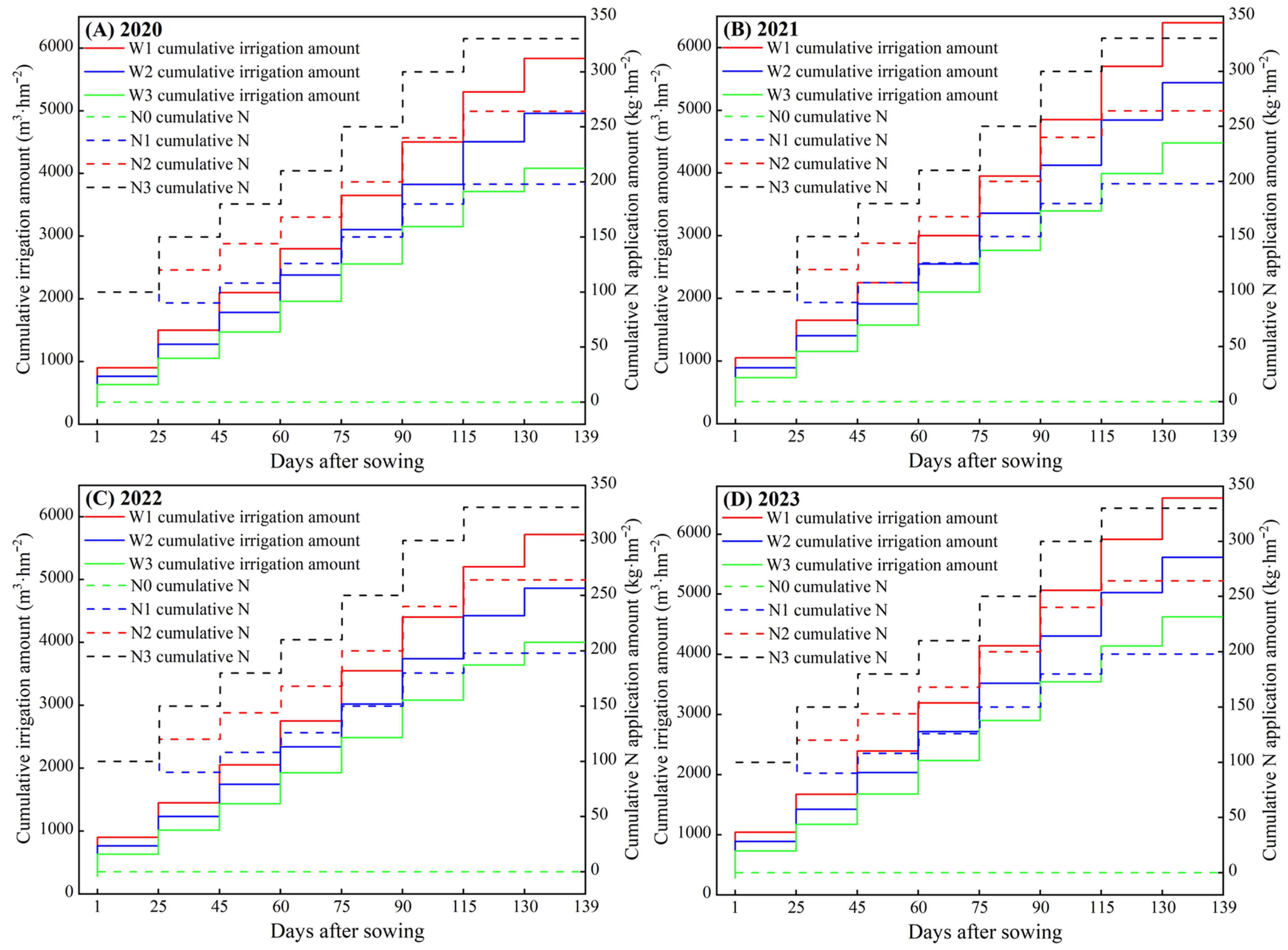

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Measurement Items and Methods

4.3.1. Yield

4.3.2. Quality

4.3.3. Economic Benefits

4.3.4. Soil Water Content

4.3.5. Water–Nitrogen Use Efficiency

4.3.6. Water–Nitrogen Economic Benefit Regression Model

4.4. Error Analysis

4.5. Data Statistics and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, J.; Niu, J.; Kang, S.Z.; Adeloye, A.J.; Du, T.S. Crop production in the Hexi Corridor challenged by future climate change. J. Hydrol. 2019, 579, 124197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.S.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhang, Y. Relationship between drought and precipitation heterogeneity: An analysis across rain-fed agricultural regions in eastern Gansu, China. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri, H.; Naserin, A. Effect of different levels of water, applied nitrogen and irrigation methods on yield, yield components and IWUE of onion. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 268, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarralesHeredia, S.M.; GrimaldoJuárez, O.; SuárezHernández, Á.M.; GonzálezVega, R.I.; DíazRamírez, J.; GarcíaLópez, A.M.; SotoOrtiz, R.; GonzálezMendoza, D.; IturraldeGarcía, R.D.; DórameMiranda, R.F.; et al. Effects of different irrigation regimes and nitrogen fertilization on the physicochemical and bioactive characteristics of onion (Allium cepa L.). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Jin, Y.Z.; Wang, W.J.; Wang, Y.B.; Li, B. Water-saving and high-yield irrigation schedule of drip irrigation under plastic film condition for onion production in Minqin Oasis. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas. 2016, 34, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.J.; Mo, F.; Yang, T.; Kong, W.P.; Lu, P.P.; Yang, X.T.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, H.; et al. Evolution and adaptive management of farming tillage ssystem under climate change in the loess plateau. Chin. J. Agrometeor. 2015, 36, 393–405. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Z.Y.; Qin, A.Z.; Liang, Y.P.; Duan, A.W.; Gao, Y. A review on regulation of irrigation management on wheat physiology, grain yield, and quality. Plants 2023, 12, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadi, A.; Alharbi, A.; Alomran, A.; Alghamdi, A.G.; Louki, I.; Alkhasha, A. Effect of biochar application on morpho-physiological traits, yield, and water use efficiency of tomato crop under water quality and drought stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.Y.; Hong, C.H.; Jiao, Y.J.; Hou, S.J.; Gao, H.B. Impacts of drought on photosynthesis in major food crops and the related mechanisms of plant responses to drought. Plants 2024, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Chavira, M.M.; Herrera-Hernández, M.G.; Guzmán-Maldonado, H.; Pons-Hernández, J.L. Controlled water deficit as abiotic stress factor for enhancing the phytochemical content and adding-value of crops. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xu, H.C.; Amanullah, S.; Du, Z.Q.; Hu, X.X.; Che, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, D. Deciphering the enhancing impact of exogenous brassinolide on physiological indices of melon plants under downy mildew-induced stress. Plants 2024, 13, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.J.; Yang, P.; Zuo, W.Q.; Zhang, W.F. Optimizing water and nitrogen management can enhance nitrogen heterogeneity and stimulate root foraging. Field Crops Res. 2023, 304, 109183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.L.; Lv, H.L.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Yin, M.H.; Kang, Y.X.; Qi, G.P.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.W.; Chen, J.X. Study on the synergistic regulation model for Lycium barbarum berries under integrated irrigation and fertigation in Northwest arid regions. Agronomy 2024, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H.M.; Gao, L.J.; Zhao, C.F.; Liu, X.X.; Jiang, D.; Dai, T.B.; Tian, Z.W. Low nitrogen priming enhances Rubisco activation and allocation of nitrogen to the photosynthetic apparatus as an adaptation to nitrogen-deficit stress in wheat seedling. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 303, 154337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofiq, G.K.; Halshoy, H.S.; Mohammed, H.J.; Braim, S.A. Potential impact of biochar and organic fertilizer application on morphology, productivity and biochemical composition of onion plants. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2432441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, W.; Yang, G.Z.; Irfan, M. Crop nitrogen (N) utilization mechanism and strategies to improve N use efficiency. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2023, 45, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.F.; Li, F.; Hong, M.; Chang, F.; Gao, H.Y. Effects of nitrogen rate and urease inhibitor on N2O emission and NH3 volatilization in drip irrigated potato fields. J. Plant Nutr. Fert. 2018, 24, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinca, L.C.; Grenni, P.; Onet, C.; Onet, A. Fertilization and soil microbial community: A review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Q.; Zhao, Z.H.; Jiang, B.L.; Baoyin, B.; Cui, Z.G.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, Q.Z.; Cui, J.H. Effects of long-term application of nitrogen fertilizer on soil acidification and biological properties in China: A aeta-analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.Y.; Jiang, W.T.; He, X.L.; Fiaz, S.; Ahmad, S.; Lei, X.; Wang, W.Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, X.K. A review of nitrogen translocation and nitrogen-use efficiency. J. Plant Nutr. 2019, 42, 2624–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Li, S.E.; Liang, H.; Hu, K.L.; Qin, S.J.; Guo, H. Comparison of water-and nitrogen-use efficiency over drip irrigation with border irrigation based on a model approach. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Pan, X.F.; Deng, H.L.; Li, M.; Yang, J.N. Effect of water and nitrogen coupling regulation on the growth, physiology, yield, and quality attributes of Isatis tinctoria L. in the oasis irrigation area of the Hexi Corridor. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehr, P.P.; Erban, A.; Hartwig, R.P.; Wimmer, M.A.; Kopka, J.; Zörb, C. Guard cell-specific metabolic responses to drought stress in maize. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.X.; Ma, X.L.; Wang, W.; Xu, C.T.; Xiang, X.; Li, W.J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Tran, L.S.P.; Zhang, B.Y. Ameliorating drought resistance in Arabidopsis and alfalfa under water deficit conditions through inoculation with Bacillus tequilensis G128 and B. velezensis G138 derived from an arid environment. Plant Stress. 2025, 15, 100727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Li, S.L.; Ning, C.C.; Ren, J.F.; Xia, Z.Q.; Zhu, M.M.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.H.; Ma, Q.; Yu, W.T. Effects of exogenous nitrogen addition on soil organic nitrogen fractions in different fertility soils: Result from a 15N cross-labeling experiment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 379, 109366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhang, L.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.Q.; Shi, W.M.; Li, Y. The role of the nitrate transporter NRT1.1 in plant iron homeostasis and toxicity on ammonium. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 232, 106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.H.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, T.X.; Chen, N.; Xin, M.X.; Qi, Q.; Liu, B. Controlled-release fertilizer improved sunflower yield and nitrogen use efficiency by promoting root growth and water and nitrogen capacity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Feng, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Shi, H.Z. Review of absorption and utilization of different nitrogen forms and their effects on plant physiological metabolism. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 25, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, G.C.; Minhas, P.S.; Meena, K.K.; Singh, N.P.; Hegade, P.M.; Sorty, A.M. Growth, bulb yield, water productivity and quality of onion (Allium cepa L.) as affected by deficit irrigation regimes and exogenous application of plant bio–regulators. Agric. Water Manage. 2018, 199, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, G.C.; Minhas, P.S.; Kumar, S.; Khapte, P.S.; Rane, J.; Reddy, K.S. Bulb productivity and quality of monsoon onion (Allium cepa L.) as affected by transient waterlogging at different growth stages and its alleviation with plant growth regulators. Agric. Water Manage. 2023, 278, 108136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Z.; Gao, J. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer reduction and amino acid liquid fertilizer increase on the growth, yield and quality of onion under dew film drip irrigation. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2019, 58, 838–845. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, P.; Batra, V.K.; Bhatia, A.K. Nutritional quality of onion as influenced by irrigation scheduling and nitrogen fertigation. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 44, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.Z.; Luo, S.Y.; Xu, Y.W.; Zhang, P.G.; Sun, Z.Y.; Hu, K.; Li, M. Optimization of irrigation and fertilization in maize–soybean system based on coupled water–carbon–nitrogen interactions. Agronomy 2024, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, T.; Mao, X.M.; Adeloye, A.J. Modeling crop water consumption and water productivity in the middle reaches of Heihe River Basin. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 123, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.T.; Wang, G.C.; Hu, F.L.; Fan, Z.L.; Yin, W.; Cao, W.D.; Chai, Q.; Yao, T. Additive intercropping green manure enhances maize water productivity through water competition and compensation under reduced nitrogen fertilizer application. Agric. Water Manage. 2025, 311, 109388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Chen, L.F.; Luo, D.W.; He, Z.B.; He, X.L. Nitrogen uptake, surplus, and leaching in desert oasis ields in the Hexi Corridor in northwestern China. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2024, 30, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, I.; Hamdan, A. Onion crop response to different irrigation and N-fertilizer levels in dry Mediterranean region. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 32, 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- Tagay, T.; Datt, S.P.; Tuma, A. Effect of the irrigation interval and nitrogen rate on yield and yield components of onion (Allium cepa L.) at Arba Minch, Southern Ethiopia. Adv. Agric. 2022, 2022, 4655590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.L.; Zhang, H.J.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, F.Q.; Yu, H.Y.; Wu, K.Q.; Wang, Y.C.; Zhou, H.; Li, X. Application of mulched drip irrigation under water deficit in improving the productivity and quality of onion in Hexi Corridor. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 34, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.N.; Yang, S.H.; Jiang, Z.W.; Xu, Y.; Jiao, X.Y. Effect of irrigation and fertilizer management on rice yield and nitrogen loss: A meta-analysis. Plants 2022, 11, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, M.; Patra, S.K.; Datta, A. Effects of nitrogen fertilization and micro-sprinkler irrigation on soil water and nitrogen contents, their productivities, bulb yield and economics of winter onion production. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 162, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, P.; Batra, V.K.; Bhatia, A.K.; Sain, V. Effect of water deficit and fertigation on nutrients uptake and soil fertility of drip irrigated onion (Allium cepa L.) in semi-arid region of India. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 44, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.Y.; Wang, M.D.; Yu, L.Y.; Xu, J.T.; Cai, H.J. Optimization of water and nitrogen management in wheat cultivation affected by biochar application—Insights into resource utilization and economic benefits. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 304, 109093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri, H.; Naserin, A. Comparison of different irrigation methods for onion by means of water and nitrogen response functions. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Xin, M.X.; Shi, H.B.; Yan, J.W.; Zhao, C.Y.; Hao, Y.F. Coupling effect and system optimization of controlled-release fertilizer and water in arid salinized areas. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.H.; Chen, S.Y.; Liu, P.Z. Exploration of the textbook system for plant physiology and biochemistry experiments in agricultural colleges and universities. Plant Physiol. J. 2004, 40, 487–488. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J. Determination of soluble protein in alfalfa by Coomassie bright blue G-250 staining. Agric. Eng. Technol. 2016, 36, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.F.; Chen, W.; Hui, L.C.; Xun, G.L.; Li, W.Y.; He, L.Y.; Chen, Z.T.; Miao, M.H.; Pan, M.H. Analysis and evaluation of nutritional quality of different varieties of onion. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2020, 36, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Z.W.; Wu, G.H.; Liu, G.L.; Zhang, Y.J.; Xu, K.; Xie, L.; Gan, L. Comparison of vitamin C concentrations in dark colour fruits and vegetables detected by automatic potentiometric titration and HPLC method. J. Jilin Univ. 2014, 40, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesini, G.; Eckert, D.J.; Florres, J.P.M.; Alves, L.A.; Filippi, D.; Naibo, G.; Vian, A.L.; Bredemeier, C.; dos Santos, D.R.; Tiecher, T. Band applied K increases agronomic and economic efficiency of K fertilization in a crop rotation under no-till in southern Brazil. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.F.; Zhang, H.J.; Yu, S.C.; Deng, H.L.; Chen, X.T.; Zhou, C.L.; Li, F.Q. Strategies for the management of water and nitrogen interaction in seed maize production; A case study from China Hexi Corridor Oasis Agricultural Area. Agric. Water Manage. 2024, 292, 108685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Treatment | Bulb Fresh Weight (g) | Diameter (mm) | Length (mm) | Onion Oil (%) | Soluble Sugars (mg·g−1) | Soluble Proteins (mg·g−1) | Vitamin C (mg·100g−1) | Propionic Acid (mg·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | N0W1 | 164.65 ± 4.06 i | 58.91 ± 2.40 g | 61.84 ± 1.09 g | 0.29 ± 0.011 h | 142.05 ± 7.58 fg | 16.44 ± 0.38 h | 15.58 ± 0.45 g | 0.20 ± 0.009 h |

| N0W2 | 239.04 ± 9.12 f | 65.40 ± 3.19 f | 77.98 ± 2.46 f | 0.35 ± 0.015 def | 165.30 ± 6.21 cd | 18.48 ± 0.68 fg | 16.51 ± 0.53 ef | 0.25 ± 0.006 ef | |

| N0W3 | 262.19 ± 4.28 e | 79.45 ± 3.00 de | 85.23 ± 4.51 de | 0.34 ± 0.011 ef | 166.27 ± 3.30 cd | 17.75 ± 0.49 g | 17.91 ± 0.05 cd | 0.23 ± 0.003 g | |

| N1W1 | 227.46 ± 11.29 fg | 75.47 ± 1.76 e | 83.22 ± 1.94 de | 0.30 ± 0.015 h | 147.48 ± 5.70 f | 19.36 ± 1.12 ef | 16.05 ± 0.82 fg | 0.21 ± 0.011 h | |

| N1W2 | 325.12 ± 16.76 d | 82.33 ± 3.15 cd | 85.53 ± 4.20 de | 0.37 ± 0.020 cd | 172.35 ± 2.63 bc | 21.26 ± 0.72 bc | 18.28 ± 0.61 bc | 0.27 ± 0.005 cd | |

| N1W3 | 352.59 ± 13.38 c | 85.88 ± 4.52 bc | 87.14 ± 3.07 d | 0.36 ± 0.019 de | 178.69 ± 5.345 ab | 18.81 ± 0.65 fg | 18.84 ± 0.11 b | 0.26 ± 0.013 de | |

| N2W1 | 213.99 ± 11.21 g | 74.30 ± 2.37 e | 80.55 ± 1.09 ef | 0.33 ± 0.016 fg | 151.26 ± 2.75 ef | 22.90 ± 0.34 a | 17.59 ± 0.35 cd | 0.24 ± 0.008 fg | |

| N2W2 | 381.11 ± 10.59 b | 90.43 ± 4.31 ab | 99.84 ± 1.85 b | 0.42 ± 0.013 a | 180.45 ± 7.64 ab | 22.98 ± 0.20 a | 20.70 ± 0.74 a | 0.30 ± 0.012 a | |

| N2W3 | 409.12 ± 23.34 a | 90.97 ± 3.33 ab | 102.71 ± 4.26 b | 0.42 ± 0.021 a | 184.05 ± 4.30 a | 20.61 ± 0.61 cd | 20.43 ± 0.40 a | 0.29 ± 0.014 ab | |

| N3W1 | 187.69 ± 7.53 h | 69.00 ± 2.03 f | 78.01 ± 1.95 f | 0.31 ± 0.012 gh | 136.71 ± 5.98 g | 21.95 ± 0.92 ab | 17.16 ± 0.20 de | 0.23 ± 0.010 g | |

| N3W2 | 371.33 ± 11.86 bc | 87.65 ± 2.01 b | 93.86 ± 1.73 c | 0.40 ± 0.008 ab | 157.96 ± 6.58 de | 22.77 ± 0.53 a | 20.05 ± 0.74 a | 0.30 ± 0.011 a | |

| N3W3 | 412.54 ± 18.63 a | 93.25 ± 1.38 a | 109.18 ± 3.02 a | 0.39 ± 0.011 bc | 160.30 ± 7.94 de | 20.02 ± 0.34 de | 19.77 ± 0.46 a | 0.28 ± 0.012 bc | |

| Significance (F) | W | 487.71 *** | 116.30 *** | 156.13 *** | 101.10 *** | 83.69 *** | 32.47 *** | 93.77 *** | 116.98 *** |

| N | 130.14 *** | 63.96 *** | 90.99 *** | 31.66 *** | 21.51 *** | 96.20 *** | 57.94 *** | 46.99 *** | |

| W × N | 17.75 *** | 6.24 *** | 14.13 *** | 1.35 ns | 0.59 ns | 5.43 ** | 3.15 * | 1.00 ns | |

| 2021 | N0W1 | 142.67 ± 6.20 h | 54.68 ± 1.47 h | 66.33 ± 2.78 e | 0.26 ± 0.011 f | 133.86 ± 0.73 ij | 16.09 ± 0.94 g | 15.32 ± 0.67 g | 0.18 ± 0.003 h |

| N0W2 | 198.57 ± 7.74 ef | 70.95 ± 1.83 ef | 72.80 ± 1.00 d | 0.32 ± 0.006 cd | 154.32 ± 4.89 ef | 18.18 ± 0.95 ef | 16.49 ± 0.16 ef | 0.24 ± 0.013 de | |

| N0W3 | 217.56 ± 10.61 e | 73.92 ± 3.63 de | 73.24 ± 2.96 d | 0.31 ± 0.016 d | 159.17 ± 2.66 de | 17.62 ± 0.41 f | 17.53 ± 0.24 de | 0.22 ± 0.011 fg | |

| N1W1 | 189.37 ± 11.07 fg | 68.81 ± 1.87 fg | 71.99 ± 3.19 d | 0.27 ± 0.004 f | 137.46 ± 7.88 hi | 19.29 ± 0.29 de | 16.08 ± 0.87 fg | 0.19 ± 0.007 h | |

| N1W2 | 297.93 ± 13.58 d | 75.53 ± 2.03 d | 83.71 ± 4.55 bc | 0.35 ± 0.018 b | 165.03 ± 6.32 cd | 21.05 ± 1.02 bc | 18.27 ± 0.89 cd | 0.25 ± 0.013 d | |

| N1W3 | 307.94 ± 10.69 cd | 76.44 ± 2.14 cd | 83.69 ± 2.48 bc | 0.34 ± 0.008 bc | 170.18 ± 4.70 bc | 18.55 ± 0.35 ef | 18.91 ± 0.30 bc | 0.24 ± 0.008 de | |

| N2W1 | 192.49 ± 6.71 fg | 64.79 ± 1.16 g | 66.52 ± 2.16 e | 0.30 ± 0.016 de | 140.91 ± 1.09 hi | 22.02 ± 0.14 ab | 17.38 ± 0.80 de | 0.23 ± 0.010 ef | |

| N2W2 | 367.93 ± 16.83 b | 80.00 ± 2.67 c | 87.51 ± 3.12 b | 0.40 ± 0.013 a | 176.34 ± 6.48 ab | 22.51 ± 0.71 a | 20.62 ± 0.42 a | 0.31 ± 0.015 a | |

| N2W3 | 406.18 ± 8.38 a | 91.26 ± 4.22 a | 98.24 ± 2.32 a | 0.39 ± 0.020 a | 181.52 ± 3.68 a | 20.74 ± 1.08 bc | 20.41 ± 0.64 a | 0.29 ± 0.010 b | |

| N3W1 | 174.48 ± 5.03 g | 67.82 ± 2.16 fg | 63.67 ± 3.03 e | 0.28 ± 0.013 ef | 127.70 ± 1.55 j | 21.46 ± 0.32 ab | 17.05 ± 0.78 ef | 0.21 ± 0.009 g | |

| N3W2 | 322.56 ± 8.10 c | 77.88 ± 1.66 cd | 81.23 ± 1.71 c | 0.38 ± 0.014 a | 144.62 ± 7.00 gh | 21.93 ± 0.68 ab | 19.86 ± 0.71 ab | 0.30 ± 0.015 ab | |

| N3W3 | 399.12 ± 20.57 a | 87.06 ± 1.56 b | 97.80 ± 3.41 a | 0.38 ± 0.019 a | 149.47 ± 1.29 fg | 19.81 ± 0.66 cd | 19.53 ± 0.58 ab | 0.27 ± 0.010 c | |

| Significance (F) | W | 638.91 *** | 183.28 *** | 170.15 *** | 135.32 *** | 141.15 *** | 19.30 *** | 62.54 *** | 140.16 *** |

| N | 246.34 *** | 48.85 *** | 35.80 *** | 39.55 *** | 49.49 *** | 71.01 *** | 39.08 *** | 64.08 *** | |

| W × N | 34.58 *** | 9.41 *** | 18.22 *** | 2.25 ns | 3.10 * | 3.51 * | 1.72 ns | 1.60 ns | |

| 2022 | N0W1 | 113.28 ± 7.21 h | 56.34 ± 2.71 e | 52.23 ± 2.98 f | 0.24 ± 0.013 h | 129.62 ± 4.96 gh | 16.12 ± 0.76 e | 15.27 ± 0.49 h | 0.16 ± 0.003 g |

| N0W2 | 141.82 ± 9.17 g | 59.04 ± 3.04 e | 69.82 ± 3.68 de | 0.31 ± 0.013 ef | 150.46 ± 4.53 de | 17.81 ± 0.73 d | 16.18 ± 0.41 gh | 0.22 ± 0.007 de | |

| N0W3 | 207.42 ± 10.16 e | 66.82 ± 2.97 d | 75.15 ± 3.83 cd | 0.30 ± 0.011 f | 160.01 ± 6.49 cd | 17.46 ± 0.85 de | 17.49 ± 0.59 ef | 0.21 ± 0.003 e | |

| N1W1 | 149.82 ± 9.44 fg | 64.53 ± 2.72 d | 70.15 ± 3.12 de | 0.25 ± 0.005 gh | 134.38 ± 1.08 fg | 19.05 ± 0.58 cd | 15.93 ± 0.60 gh | 0.18 ± 0.007 f | |

| N1W2 | 257.75 ± 7.73 d | 72.38 ± 3.77 c | 76.82 ± 3.92 c | 0.35 ± 0.008 cd | 164.72 ± 7.58 c | 20.94 ± 0.70 ab | 18.05 ± 0.69 de | 0.24 ± 0.010 c | |

| N1W3 | 297.89 ± 12.51 c | 74.23 ± 3.09 c | 77.77 ± 3.67 c | 0.33 ± 0.011 de | 168.28 ± 3.97 bc | 18.32 ± 1.00 d | 18.64 ± 0.37 cd | 0.23 ± 0.009 cd | |

| N2W1 | 160.21 ± 9.85 f | 66.71 ± 1.37 d | 71.11 ± 1.86 de | 0.30 ± 0.013 f | 136.51 ± 6.79 fg | 22.08 ± 1.08 a | 17.02 ± 0.71 efg | 0.21 ± 0.009 e | |

| N2W2 | 342.93 ± 15.84 b | 84.54 ± 3.44 b | 83.52 ± 2.62 b | 0.41 ± 0.011 a | 175.39 ± 8.84 ab | 22.32 ± 0.40 a | 20.65 ± 0.87 a | 0.29 ± 0.007 a | |

| N2W3 | 374.50 ± 7.77 a | 95.97 ± 3.79 a | 96.58 ± 1.92 a | 0.39 ± 0.015 ab | 182.43 ± 9.25 a | 20.65 ± 1.46 ab | 20.27 ± 0.86 ab | 0.28 ± 0.013 ab | |

| N3W1 | 133.83 ± 6.01 g | 58.70 ± 3.10 e | 67.21 ± 2.79 e | 0.27 ± 0.016 g | 124.08 ± 0.68 h | 21.29 ± 1.19 ab | 16.85 ± 0.70 fg | 0.19 ± 0.006 f | |

| N3W2 | 298.46 ± 14.93 c | 77.08 ± 3.47 c | 77.28 ± 2.96 c | 0.38 ± 0.012 b | 141.50 ± 5.77 ef | 21.74 ± 0.43 a | 19.51 ± 0.66 bc | 0.29 ± 0.008 a | |

| N3W3 | 365.91 ± 7.81 a | 87.98 ± 2.30 b | 85.74 ± 3.88 b | 0.37 ± 0.012 bc | 144.92 ± 1.00 ef | 19.93 ± 0.96 bc | 19.28 ± 0.55 bc | 0.27 ± 0.010 b | |

| Significance (F) | W | 883.95 *** | 126.33 *** | 105.27 *** | 230.22 *** | 108.15 *** | 10.02** | 61.13 *** | 280.72 *** |

| N | 305.26 *** | 78.84 *** | 48.94 *** | 81.90 *** | 38.29 *** | 45.50 *** | 36.93 *** | 112.41 *** | |

| W × N | 43.12 *** | 10.82 *** | 5.40 ** | 2.38 ns | 3.10 * | 2.03 ns | 2.55 * | 4.47 ** | |

| 2023 | N0W1 | 86.35 ± 4.02 h | 54.26 ± 2.87 g | 58.54 ± 2.75 e | 0.22 ± 0.004 g | 125.65 ± 4.43 gh | 15.98 ± 0.37 i | 15.04 ± 0.43 h | 0.14 ± 0.005 h |

| N0W2 | 159.54 ± 7.79 f | 59.03 ± 1.29 fg | 64.28 ± 2.65 d | 0.29 ± 0.008 e | 147.38 ± 1.89 de | 17.57 ± 0.65 gh | 15.75 ± 0.51 gh | 0.21 ± 0.011 de | |

| N0W3 | 227.52 ± 8.60 e | 70.55 ± 4.83 d | 72.43 ± 3.54 c | 0.28 ± 0.009 e | 154.90 ± 9.17 cd | 17.02 ± 0.47 h | 17.18 ± 0.38 ef | 0.19 ± 0.005 f | |

| N1W1 | 140.71 ± 5.25 g | 65.43 ± 1.64 de | 64.56 ± 1.97 d | 0.23 ± 0.011 g | 128.64 ± 7.25 gh | 18.93 ± 1.10 ef | 15.63 ± 0.80 gh | 0.16 ± 0.007 g | |

| N1W2 | 286.34 ± 10.97 d | 77.78 ± 2.56 c | 82.36 ± 2.75 b | 0.35 ± 0.009 c | 159.86 ± 9.60 bc | 20.75 ± 0.70 bcd | 17.85 ± 0.59 de | 0.25 ± 0.011 c | |

| N1W3 | 336.61 ± 17.71 bc | 85.36 ± 2.48 ab | 93.90 ± 5.12 a | 0.31 ± 0.013 d | 164.75 ± 8.45 bc | 18.40 ± 0.64 fg | 18.41 ± 0.50 cd | 0.22 ± 0.010 d | |

| N2W1 | 146.08 ± 7.43 fg | 67.93 ± 3.40 de | 71.86 ± 3.52 c | 0.27 ± 0.012 e | 132.83 ± 6.28 fg | 21.85 ± 0.33 ab | 16.74 ± 0.33 f | 0.20 ± 0.009 ef | |

| N2W2 | 347.38 ± 16.55 b | 86.02 ± 2.37 ab | 93.13 ± 1.69 a | 0.40 ± 0.018 a | 170.21 ± 8.62 ab | 22.17 ± 0.19 a | 20.49 ± 0.73 a | 0.29 ± 0.007 a | |

| N2W3 | 400.32 ± 14.64 a | 89.14 ± 3.94 a | 98.33 ± 2.46 a | 0.38 ± 0.020 b | 179.37 ± 3.57 a | 20.29 ± 0.60 cd | 20.07 ± 0.39 ab | 0.27 ± 0.012 b | |

| N3W1 | 136.02 ± 6.23 g | 63.85 ± 2.52 ef | 62.71 ± 3.52 de | 0.25 ± 0.001 f | 119.82 ± 3.04 h | 21.03 ± 0.88 bc | 16.28 ± 0.56 fg | 0.17 ± 0.006 g | |

| N3W2 | 327.26 ± 7.50 c | 82.56 ± 3.68 bc | 87.02 ± 1.73 b | 0.36 ± 0.015 bc | 137.09 ± 5.53 efg | 21.48 ± 0.50 ab | 19.36 ± 0.71 bc | 0.26 ± 0.009 bc | |

| N3W3 | 389.33 ± 5.76 a | 87.60 ± 2.74 ab | 96.54 ± 4.66 a | 0.36 ± 0.009 bc | 141.56 ± 6.11 ef | 19.67 ± 0.34 de | 18.92 ± 0.44 c | 0.26 ± 0.009 bc | |

| Significance (F) | W | 1333.80 *** | 141.23 *** | 203.39 *** | 286.85 *** | 85.71 *** | 22.14 *** | 88.75 *** | 317.06 *** |

| N | 335.95 *** | 76.75 *** | 82.44 *** | 88.85 *** | 29.17 *** | 97.39 *** | 52.19 *** | 114.10 *** | |

| W × N | 29.89 *** | 3.57 * | 7.14 *** | 5.69 ** | 2.26 ns | 3.43 * | 4.56 ** | 3.61 * |

| Treatment | 2020 Year (t·ha−1) | 2021 Year (t·ha−1) | 2022 Year (t·ha−1) | 2023 Year (t·ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N0W1 | 55.25 ± 1.22 i | 46.77 ± 0.43 h | 36.98 ± 0.87 i | 28.26 ± 0.86 h |

| N0W2 | 79.15 ± 1.38 f | 65.37 ± 0.79 ef | 46.88 ± 1.32 gh | 53.38 ± 0.67 f |

| N0W3 | 88.06 ± 2.06 e | 70.75 ± 2.06 e | 67.97 ± 1.47 e | 74.76 ± 1.14 e |

| N1W1 | 75.44 ± 1.97 fg | 62.91 ± 1.86 f | 51.27 ± 0.69 fg | 46.62 ± 0.68 g |

| N1W2 | 106.72 ± 2.84 d | 99.72 ± 0.83 d | 86.13 ± 1.91 d | 94.71 ± 1.79 d |

| N1W3 | 118.78 ± 1.62 c | 100.59 ± 2.03 d | 99.29 ± 3.01 c | 113.30 ± 1.89 bc |

| N2W1 | 69.71 ± 2.00 gh | 63.95 ± 0.91 f | 53.02 ± 0.98 f | 49.43 ± 1.43 fg |

| N2W2 | 127.06 ± 3.70 b | 123.19 ± 2.64 b | 115.63 ± 3.18 b | 115.23 ± 1.83 b |

| N2W3 | 135.44 ± 3.96 a | 134.41 ± 2.61 a | 125.94 ± 2.66 a | 132.26 ± 3.37 a |

| N3W1 | 63.88 ± 1.84 h | 56.75 ± 1.02 g | 45.22 ± 0.77 h | 45.86 ± 1.04 g |

| N3W2 | 123.30 ± 2.90 bc | 109.15 ± 1.60 c | 100.19 ± 1.32 c | 108.95 ± 2.80 c |

| N3W3 | 136.93 ± 2.69 a | 131.84 ± 3.68 a | 120.89 ± 1.04 ab | 128.25 ± 0.90 a |

| W | 520.40 *** | 803.88 *** | 1044.05 *** | 1710.28 *** |

| N | 134.63 *** | 325.68 *** | 386.08 *** | 442.83 *** |

| W × N | 18.41 *** | 46.02 *** | 52.59 *** | 35.50 *** |

| Year | Treatment | ET (mm) | WUE (kg·m−3) | IWUE (kg·m−3) | PFPN (kg·kg−1) | AUEN (kg·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | N0W1 | 557.91 ± 21.55 c | 9.91 ± 0.38 h | 13.53 ± 0.46 h | — | — |

| N0W2 | 568.44 ± 19.71 c | 13.93 ± 0.39 d | 15.96 ± 0.37 g | — | — | |

| N0W3 | 671.34 ± 28.30 b | 13.13 ± 0.54 e | 15.10 ± 0.20 g | — | — | |

| N1W1 | 570.50 ± 29.71 c | 13.23 ± 0.23 de | 18.48 ± 0.73 e | 381.03 ± 15.09 f | 101.99 ± 8.71 e | |

| N1W2 | 679.27 ± 13.62 b | 15.71 ± 0.13 c | 21.52 ± 0.67 c | 538.99 ± 9.16 b | 139.25 ± 7.35 cd | |

| N1W3 | 775.91 ± 15.78 a | 15.31 ± 0.14 c | 20.36 ± 0.50 d | 599.91 ± 14.71 a | 155.15 ± 8.85 b | |

| N2W1 | 576.52 ± 17.89 c | 12.09 ± 0.23 f | 17.07 ± 0.60 f | 264.05 ± 9.34 g | 54.77 ± 2.60 f | |

| N2W2 | 682.41 ± 25.13 b | 18.63 ± 0.39 a | 25.63 ± 0.61 a | 481.29 ± 11.45 d | 181.49 ± 4.81 a | |

| N2W3 | 777.53 ± 26.88 a | 17.43 ± 0.30 b | 23.22 ± 0.45 b | 513.05 ± 9.86 c | 179.47 ± 5.48 a | |

| N3W1 | 581.48 ± 33.58 c | 11.00 ± 0.35 g | 15.65 ± 0.67 g | 193.59 ± 8.28 h | 26.17 ± 5.12 g | |

| N3W2 | 685.60 ± 29.55 b | 18.01 ± 1.04 ab | 24.87 ± 0.54 a | 373.62 ± 8.05 f | 133.78 ± 3.41 d | |

| N3W3 | 786.51 ± 31.48 a | 17.42 ± 0.38 b | 23.47 ± 0.64 b | 414.93 ± 11.32 e | 148.07 ± 8.20 bc | |

| Significance (F) | W | 155.24 *** | 451.81 *** | 389.32 *** | 1088.16 *** | 660.54 *** |

| N | 23.00 *** | 124.44 *** | 333.14 *** | 589.30 *** | 79.48 *** | |

| W × N | 3.42 * | 22.09 *** | 40.60 *** | 5.70 ** | 47.73 *** | |

| 2021 | N0W1 | 566.17 ± 23.10 d | 8.26 ± 0.15 i | 10.44 ± 0.39 g | — | — |

| N0W2 | 617.88 ± 30.18 c | 10.58 ± 0.35 fg | 12.02 ± 0.25 f | — | — | |

| N0W3 | 716.23 ± 27.06 b | 9.88 ± 0.33 g | 11.06 ± 0.56 g | — | — | |

| N1W1 | 584.92 ± 13.65 cd | 10.75 ± 0.19 f | 14.05 ± 0.52 e | 317.72 ± 11.83 d | 81.52 ± 4.98 f | |

| N1W2 | 703.48 ± 26.94 b | 14.17 ± 0.40 d | 18.34 ± 0.27 c | 503.61 ± 7.31 a | 173.48 ± 4.56 c | |

| N1W3 | 848.86 ± 44.66 a | 11.85 ± 0.47 e | 15.72 ± 0.55 d | 508.05 ± 17.76 a | 150.75 ± 1.29 d | |

| N2W1 | 607.66 ± 19.41 cd | 10.52 ± 0.29 fg | 14.28 ± 0.35 e | 242.25 ± 5.98 e | 65.11 ± 5.99 g | |

| N2W2 | 731.76 ± 34.86 b | 16.84 ± 0.17 a | 22.65 ± 0.84 a | 466.64 ± 17.30 b | 219.0 ± 4 14.15 b | |

| N2W3 | 850.54 ± 31.10 a | 15.80 ± 0.79 b | 21.01 ± 0.70 b | 509.13 ± 17.08 a | 241.15 ± 10.24 a | |

| N3W1 | 628.71 ± 18.50 c | 9.03 ± 0.22 h | 12.67 ± 0.39 f | 171.95 ± 5.33 f | 30.24 ± 8.00 h | |

| N3W2 | 733.67 ± 16.80 b | 14.88 ± 0.27 cd | 20.07 ± 0.51 b | 330.76 ± 8.40 d | 132.68 ± 5.75 e | |

| N3W3 | 855.11 ± 12.66 a | 15.42 ± 0.90 bc | 20.61 ± 1.00 b | 399.51 ± 19.35 c | 185.13 ± 12.09 c | |

| Significance (F) | W | 208.92 *** | 345.96 *** | 298.59 *** | 751.50 *** | 674.80 *** |

| N | 29.74 *** | 191.17 *** | 344.95 *** | 274.62 *** | 116.46 *** | |

| W × N | 2.80 * | 30.63 *** | 37.63 *** | 10.06 *** | 40.83 *** | |

| 2022 | N0W1 | 485.30 ± 14.15 e | 7.62 ± 0.32 h | 9.24 ± 0.43 h | — | — |

| N0W2 | 540.23 ± 27.12 cd | 8.68 ± 0.12 g | 9.65 ± 0.40 h | — | — | |

| N0W3 | 608.05 ± 25.48 b | 11.18 ± 0.38 e | 11.89 ± 0.58 fg | — | — | |

| N1W1 | 512.23 ± 26.97 de | 10.01 ± 0.23 f | 12.81 ± 0.39 ef | 258.93 ± 7.88 f | 72.15 ± 3.17 e | |

| N1W2 | 603.72 ± 16.64 b | 14.27 ± 0.12 d | 17.72 ± 0.59 d | 434.99 ± 14.54 c | 198.21 ± 8.21 c | |

| N1W3 | 708.51 ± 26.58 a | 14.01 ± 0.19 d | 17.37 ± 0.89 d | 501.45 ± 25.72 a | 158.15 ± 9.06 d | |

| N2W1 | 540.29 ± 16.02 cd | 9.81 ± 0.27 f | 13.25 ± 0.65 e | 200.82 ± 9.82 g | 60.73 ± 5.49 f | |

| N2W2 | 609.14 ± 26.24 b | 18.98 ± 0.49 a | 23.79 ± 0.43 a | 438.00 ± 7.4 c | 260.41 ± 6.08 a | |

| N2W3 | 709.64 ± 20.16 a | 17.75 ± 0.34 b | 22.03 ± 0.55 b | 477.06 ± 11.91 b | 219.59 ± 1.55 b | |

| N3W1 | 557.40 ± 18.14 c | 8.11 ± 0.53 gh | 11.30 ± 0.63 g | 137.03 ± 7.69 h | 24.97 ± 3.29 g | |

| N3W2 | 610.13 ± 22.27 b | 16.42 ± 0.41 c | 20.62 ± 0.41 c | 303.60 ± 6.05 e | 161.53 ± 4.42 d | |

| N3W3 | 711.58 ± 32.93 a | 16.99 ± 0.44 c | 21.14 ± 0.67 bc | 366.32 ± 11.64 d | 160.34 ± 3.57 d | |

| Significance (F) | W | 142.96 *** | 1177.77 *** | 499.26 *** | 944.29 *** | 2011.70 *** |

| N | 23.20 *** | 550.25 *** | 454.53 *** | 258.15 *** | 313.36 *** | |

| W × N | 1.43 ns | 101.54 *** | 54.84 *** | 6.98 ** | 57.57 *** | |

| 2023 | N0W1 | 529.29 ± 25.22 h | 5.34 ± 0.24 h | 6.11 ± 0.24 g | — | — |

| N0W2 | 598.45 ± 20.83 fg | 8.92 ± 0.16 f | 9.51 ± 0.23 f | — | — | |

| N0W3 | 673.16 ± 26.78 de | 11.11 ± 0.15 e | 11.32 ± 0.60 d | — | — | |

| N1W1 | 562.83 ± 24.64 gh | 8.28 ± 0.16 f | 10.08 ± 0.34 ef | 235.43 ± 7.91 g | 92.71 ± 270 e | |

| N1W2 | 662.33 ± 17.50 e | 14.30 ± 0.32 d | 16.87 ± 0.33 c | 478.35 ± 9.43 c | 208.78 ± 2.97 b | |

| N1W3 | 761.36 ± 13.20 ab | 14.88 ± 0.20 cd | 17.16 ± 0.41 c | 572.22 ± 13.72 a | 194.64 ± 8.02 c | |

| N2W1 | 575.27 ± 26.25 gh | 8.59 ± 0.23 f | 10.69 ± 0.53 de | 187.23 ± 9.36 h | 80.18 ± 5.40 e | |

| N2W2 | 712.31 ± 28.65 cd | 16.18 ± 0.16 b | 20.53 ± 0.81 a | 436.49 ± 17.16 d | 234.31 ± 12.83 a | |

| N2W3 | 773.92 ± 32.39 ab | 17.09 ± 0.62 a | 20.03 ± 0.40 ab | 501.00 ± 9.90 b | 217.82 ± 8.51 b | |

| N3W1 | 630.60 ± 34.07 ef | 7.27 ± 0.20 g | 9.92 ± 0.40 ef | 138.97 ± 5.54 i | 53.33 ± 2.24 f | |

| N3W2 | 727.18 ± 35.55 bc | 14.98 ± 0.64 c | 19.41 ± 0.52 b | 330.14 ± 8.92 f | 168.40 ± 7.34 d | |

| N3W3 | 789.68 ± 35.95 a | 16.24 ± 0.67 b | 19.42 ± 0.85 b | 388.63 ± 17.03 e | 162.08 ± 8.71 d | |

| Significance (F) | W | 121.42 *** | 1406.70 *** | 885.96 *** | 1628.09 *** | 844.64 *** |

| N | 28.56 *** | 381.24 *** | 461.81 *** | 345.08 *** | 112.09 *** | |

| W × N | 1.22 ns | 23.96 *** | 27.05 *** | 12.58 *** | 8.26 ** |

| Year | Treatment | Water Input (USD·ha−1) | Fertilizer Input (USD·ha−1) | Other Inputs (USD·ha−1) | Total Input (USD·ha−1) | Economic Benefit (USD·ha−1) | Net Profit (USD·ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | N0W1 | 133.7 | 797.5 | 4821.4 | 5752.6 | 8221.8 ± 181.58 i | 2469.2 ± 181.58 i |

| N0W2 | 162.3 | 797.5 | 4821.4 | 5781.2 | 11,777.9 ± 204.61 f | 5996.7 ± 204.61 f | |

| N0W3 | 191.0 | 797.5 | 4821.4 | 5809.9 | 13,104.8 ± 306.71 e | 7294.9 ± 306.71 e | |

| N1W1 | 133.7 | 944.9 | 4821.4 | 5900.0 | 11,226.8 ± 293.00 fg | 5326.8 ± 293.00 fg | |

| N1W2 | 162.3 | 944.9 | 4821.4 | 5928.6 | 15,880.9 ± 422.31 d | 9952.3 ± 422.31 d | |

| N1W3 | 191.0 | 944.9 | 4821.4 | 5957.3 | 17,676.1 ± 240.88 c | 11,718.8 ± 240.88 c | |

| N2W1 | 133.7 | 994.0 | 4821.4 | 5949.1 | 10,373.4 ± 298.10 gh | 4424.3 ± 298.10 gh | |

| N2W2 | 162.3 | 994.0 | 4821.4 | 5977.7 | 18,907.9 ± 549.86 b | 12,930.2 ± 549.86 b | |

| N2W3 | 191.0 | 994.0 | 4821.4 | 6006.4 | 20,155.4 ± 589.51 a | 14,149.0 ± 589.51 a | |

| N3W1 | 133.7 | 1043.1 | 4821.4 | 5998.2 | 9506.7 ± 273.23 h | 3508.5 ± 273.33 h | |

| N3W2 | 162.3 | 1043.1 | 4821.4 | 6026.8 | 18,347.6 ± 431.32 bc | 12,320.8 ± 431.32 bc | |

| N3W3 | 191.0 | 1043.1 | 4821.4 | 6055.5 | 20,376.3 ± 400.85 a | 14,320.8 ± 400.85 a | |

| Significance (F) | W | — | — | — | — | 520.40 *** | 513.74 *** |

| N | — | — | — | — | 134.63 *** | 123.80 *** | |

| W × N | — | — | — | — | 18.41 *** | 18.41 *** | |

| 2021 | N0W1 | 154.2 | 824.7 | 5539.9 | 6518.8 | 10,246.1 ± 94.06 h | 3727.3 ± 94.06 h |

| N0W2 | 187.2 | 824.7 | 5539.9 | 6551.8 | 14,321.1 ± 172.31 ef | 7769.3 ± 172.31 ef | |

| N0W3 | 220.3 | 824.7 | 5539.9 | 6584.9 | 15,500.0 ± 421.15 e | 8915.1 ± 451.15 e | |

| N1W1 | 154.2 | 986.4 | 5539.9 | 6680.5 | 13,782.6 ± 407.60 f | 7102.1 ± 407.60 f | |

| N1W2 | 187.2 | 986.4 | 5539.9 | 6713.5 | 21,846.9 ± 182.59 d | 15,133.4 ± 182.59 d | |

| N1W3 | 220.3 | 986.4 | 5539.9 | 6746.6 | 22,039.5 ± 444.50 d | 15,292.9 ± 444.50 d | |

| N2W1 | 154.2 | 1040.3 | 5539.9 | 6734.4 | 14,011.9 ± 199.23 f | 7277.5 ± 199.23 f | |

| N2W2 | 187.2 | 1040.3 | 5539.9 | 6767.4 | 26,990.5 ± 578.01 b | 20,223.1 ± 578.01 b | |

| N2W3 | 220.3 | 1040.3 | 5539.9 | 6800.5 | 29,448.3 ± 570.86 a | 22,647.8 ± 570.86 a | |

| N3W1 | 154.2 | 1094.2 | 5539.9 | 6788.3 | 12,432.4 ± 222.83 g | 5644.1 ± 222.83 g | |

| N3W2 | 187.2 | 1094.2 | 5539.9 | 6821.3 | 23,913.8 ± 350.80 c | 17,092.5 ± 350.80 c | |

| N3W3 | 220.3 | 1094.2 | 5539.9 | 6854.4 | 28,885.0 ± 807.27 a | 22,030.6 ± 807.27 a | |

| Significance (F) | W | — | — | — | — | 803.88 *** | 795.63 *** |

| N | — | — | — | — | 325.68 *** | 309.89 *** | |

| W × N | — | — | — | — | 46.02 *** | 46.02 *** | |

| 2022 | N0W1 | 122.6 | 812.8 | 5369.1 | 6304.5 | 8756.3 ± 206.03 i | 2451.8 ± 206.03 i |

| N0W2 | 148.9 | 812.8 | 5369.1 | 6330.8 | 11,100.3 ± 313.70 gh | 4769.5 ± 313.70 gh | |

| N0W3 | 175.2 | 812.8 | 5369.1 | 6357.1 | 16,093.9 ± 351.32 e | 9736.8 ± 351.32 e | |

| N1W1 | 122.6 | 950.7 | 5369.1 | 6442.4 | 12,138.6 ± 163.83 fg | 5696.2 ± 163.83 fg | |

| N1W2 | 148.9 | 950.7 | 5369.1 | 6468.7 | 20,392.4 ± 451.05 d | 13,923.7 ± 451.05 d | |

| N1W3 | 175.2 | 950.7 | 5369.1 | 6495.0 | 23,508.1 ± 713.69 c | 17,013.1 ± 713.69 c | |

| N2W1 | 122.6 | 996.6 | 5369.1 | 6488.3 | 12,552.5 ± 231.85 f | 6064.2 ± 231.85 f | |

| N2W2 | 148.9 | 996.6 | 5369.1 | 6514.6 | 27,378.0 ± 753.37 b | 20,863.4 ± 753.37 b | |

| N2W3 | 175.2 | 996.6 | 5369.1 | 6540.9 | 29,819.8 ± 629.38 a | 23,278.9 ± 629.38 a | |

| N3W1 | 122.6 | 1042.6 | 5369.1 | 6534.3 | 10,707.0 ± 181.78 h | 4172.7 ± 181.78 h | |

| N3W2 | 148.9 | 1042.6 | 5369.1 | 6560.6 | 23,721.3 ± 313.15 c | 17,160.7 ± 313.15 c | |

| N3W3 | 175.2 | 1042.6 | 5369.1 | 6586.9 | 28,621.9 ± 245.20 ab | 22,035.0 ± 245.20 ab | |

| Significance (F) | W | — | — | — | — | 1044.05 *** | 1036.41 *** |

| N | — | — | — | — | 386.08 *** | 371.57 *** | |

| W × N | — | — | — | — | 52.59 *** | 52.59 *** | |

| 2023 | N0W1 | 143.2 | 682.1 | 5281.7 | 6107.0 | 5572.4 ± 170.51 h | −534.6 ± 170.51 h |

| N0W2 | 173.9 | 682.1 | 5281.7 | 6137.7 | 10,524.8 ± 132.40 f | 4387.1 ± 132.40 f | |

| N0W3 | 204.6 | 682.1 | 5281.7 | 6168.4 | 14,741.5 ± 225.44 e | 8573.1 ± 225.44 e | |

| N1W1 | 143.2 | 827.6 | 5281.7 | 6252.5 | 9191.9 ± 133.61 g | 2939.4 ± 133.61 g | |

| N1W2 | 173.9 | 827.6 | 5281.7 | 6283.2 | 18,675.9 ± 353.91 d | 12,392.7 ± 353.91 d | |

| N1W3 | 204.6 | 827.6 | 5281.7 | 6313.9 | 22,340.7 ± 373.52 bc | 16,026.8 ± 373.52 bc | |

| N2W1 | 143.2 | 876.1 | 5281.7 | 6301.0 | 9746.5 ± 281.15 fg | 3445.5 ± 281.15 fg | |

| N2W2 | 173.9 | 876.1 | 5281.7 | 6331.7 | 22,722.3 ± 361.62 b | 16,390.6 ± 361.62 b | |

| N2W3 | 204.6 | 876.1 | 5281.7 | 6362.4 | 26,080.3 ± 665.02 a | 19,717.9 ± 665.02 a | |

| N3W1 | 143.2 | 924.6 | 5281.7 | 6349.5 | 9042.6 ± 205.69 g | 2693.1 ± 205.69 g | |

| N3W2 | 173.9 | 924.6 | 5281.7 | 6380.2 | 21,482.4 ± 552.91 c | 15,102.2 ± 552.91 c | |

| N3W3 | 204.6 | 924.6 | 5281.7 | 6410.9 | 25,288.3 ± 177.00 a | 18,877.4 ± 177.00 a | |

| Significance (F) | W | — | — | — | — | 1710.28 *** | 1696.08 *** |

| N | — | — | — | — | 442.83 *** | 421.79 *** | |

| W × N | — | — | — | — | 35.50 *** | 35.51 *** |

| Targeted Economic Benefits (USD·ha−1) | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irrigation Amounts (mm) | Nitrogen Application Rates (kg·ha−1) | Irrigation Amounts (mm) | Nitrogen Application Rates (kg·ha−1) | Irrigation Amounts (mm) | Nitrogen Application Rates (kg·ha−1) | Irrigation Amounts (mm) | Nitrogen Application Rates (kg·ha−1) | |

| 19,000–17,000 | 416.5–465.3 | 146.0–204.5 | 295.5–323.9 | 127.1–253.1 | 270.5–314.3 | 91.5–259.3 | 379.4–401.0 | 139.2–256.8 |

| 21,000–19,000 | 503.1–534.9 | 219.8–259.0 | 332.4–367.9 | 117.1–235.7 | 300.7–335.0 | 127.2–253.1 | 422.3–453.5 | 140.2–206.6 |

| 23,000–21,000 | — | — | 365.6–459.3 | 120.9–234.5 | 340.2–381.1 | 124.3–235.1 | 589.4–620.8 | 127.4–236.1 |

| 25,000–23,000 | — | — | 441.6–518.9 | 110.6–193.7 | 387.1–463.7 | 112.6–216.5 | 477.3–540.4 | 123.4–222.9 |

| 27,000–25,000 | — | — | 470.4–536.2 | 152.6–225.8 | 430.5–491.9 | 138.4–222.4 | 542.0–583.7 | 161.9–224.0 |

| 29,000–27,000 | — | — | 529.6–572.1 | 203.1–257.7 | 469.9–511.4 | 194.8–254.0 | 609.4–640.3 | 226.4–275.2 |

| Growth Stages | Seedling Stage | Leaf Development Stage | Bulbification Stage | Maturity Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kc | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.05 | 0.75 |

| Treatment | Irrigation Amount (mm) | Irrigation Code Value X1 | Nitrogen Application Rate (kg·ha−1) | Nitrogen Application Rate Code Value X2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 Year | 2021 Year | 2022 Year | 2023 Year | ||||

| N0W1 | 408.31 | 447.87 | 400.20 | 462.24 | — | 0 | — |

| N0W2 | 495.81 | 543.85 | 485.96 | 561.29 | — | 0 | — |

| N0W3 | 583.30 | 639.82 | 571.72 | 660.34 | — | 0 | — |

| N1W1 | 408.31 | 447.87 | 400.20 | 462.24 | 1 | 198 | 1 |

| N1W2 | 495.81 | 543.85 | 485.96 | 561.29 | 0 | 198 | 1 |

| N1W3 | 583.30 | 639.82 | 571.72 | 660.34 | −1 | 198 | 1 |

| N2W1 | 408.31 | 447.87 | 400.20 | 462.24 | 1 | 264 | 0 |

| N2W2 | 495.81 | 543.85 | 485.96 | 561.29 | 0 | 264 | 0 |

| N2W3 | 583.30 | 639.82 | 571.72 | 660.34 | −1 | 264 | 0 |

| N3W1 | 408.31 | 447.87 | 400.20 | 462.24 | 1 | 330 | −1 |

| N3W2 | 495.81 | 543.85 | 485.96 | 561.29 | 0 | 330 | −1 |

| N3W3 | 583.30 | 639.82 | 571.72 | 660.34 | −1 | 330 | −1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pan, X.; Deng, H.; Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, R.; He, W.; Pan, W. Optimizing Water and Nitrogen Management Strategies to Unlock the Production Potential for Onion in the Hexi Corridor of China: Insights from Economic Analysis. Plants 2026, 15, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010006

Pan X, Deng H, Li G, Wang Q, Xiao R, He W, Pan W. Optimizing Water and Nitrogen Management Strategies to Unlock the Production Potential for Onion in the Hexi Corridor of China: Insights from Economic Analysis. Plants. 2026; 15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010006

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Xiaofan, Haoliang Deng, Guang Li, Qinli Wang, Rang Xiao, Wenbo He, and Wei Pan. 2026. "Optimizing Water and Nitrogen Management Strategies to Unlock the Production Potential for Onion in the Hexi Corridor of China: Insights from Economic Analysis" Plants 15, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010006

APA StylePan, X., Deng, H., Li, G., Wang, Q., Xiao, R., He, W., & Pan, W. (2026). Optimizing Water and Nitrogen Management Strategies to Unlock the Production Potential for Onion in the Hexi Corridor of China: Insights from Economic Analysis. Plants, 15(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010006