Harnessing Rhizobial Inoculation for Sustainable Nitrogen Management in Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Rhizobial Strains for Mung Bean Under Controlled Conditions

2.2. Field Evaluation of Bradyrhizobium Strains as Inoculants for Mung Bean

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Selection of Rhizobial Strains for Mung Bean Under Controlled Conditions

3.2. Field Evaluation of Bradyrhizobium Strains as Inoculants for Mung Bean

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rawal, V.; Navarro, D.K. The Global Economy of Pulses; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2019; p. 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, G.R.; Jesus, E.d.C.; Dias, A.; Coelho, M.R.R.; Molina, Y.C.; Rumjanek, N.G. Contribution of Biofertilizers to Pulse Crops: From Single-Strain Inoculants to New Technologies Based on Microbiomes Strategies. Plants 2023, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, R.M.; Yang, R.; Easdown, W.J.; Thavarajah, D.; Thavarajah, P.; Hughes, J.D.; Keatinge, J. Biofortification of Mungbean (Vigna radiata) as a Whole Food to Enhance Human Health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 1805–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.F.; Oliveira, V.R.; Vieira, C. Cultivo do feijão-mungo-verde no verão em Viçosa e em Prudente de Morais. Hortic. Bras. 2003, 21, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMEXSTAT. Ministério da Indústria, Comércio Exterior e Serviços. 2021. Available online: http://comexstat.mdic.gov.br (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Favero, V.O.; de Carvalho, R.H.; Leite, A.B.C.; de Freitas, K.M.; Zilli, J.É.; Xavier, G.R.; Rumjanek, N.G.; Urquiaga, S. Characterization and Nodulation Capacity of Native Bacteria Isolated from Mung Bean Nodules Used as a Trap Plant in Brazilian Tropical Soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 167, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, V.O.; Carvalho, R.H.; Leite, A.B.C.; Santos, D.M.T.; Freitas, K.M.; Boddey, R.M.; Xavier, G.R.; Rumjanek, N.G. Bradyrhizobium strains from Brazilian tropical soils promote increases in nodulation, growth and nitrogen fixation in mung bean. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 175, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degefu, T.; Wolde-Meskel, E.; Rasche, F. Genetic Diversity and Symbiotic Effectiveness of Bradyrhizobium Strains Nodulating Selected Annual Grain Legumes Growing in Ethiopia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, S.; Imran, A.; Mirza, M.S. Phylogenetic Diversity Analysis Reveals Bradyrhizobium Yuanmingense and Ensifer Aridi as Major Symbionts of Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.) in Pakistan. Braz. J. Microbiol. Publ. Braz. Soc. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, J.M. A Manual for the Practical Study of the Root-Nodule Bacteria; International Biological Programme Handbook No. 15; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, F.M.d.S.; Michel, D.C.; Cardoso, R.M. The Elite Strain INPA03-11B Approved as a Cowpea Inoculant in Brazil Represents a New Bradyrhizobium Species and It Has High Adaptability to Stressful Soil Conditions. Braz. J. Microbiol. Publ. Braz. Soc. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, E.M.; de Carvalho, T.S.; Guimaraes manda, A.; Ribas Leao, A.C.; Cruz, L.M.; de Baura, V.A.; Lebbe, L.; Willems, A.; de Souza Moreira, F.M. Classification of the Inoculant Strain of Cowpea UFLA03-84 and of Other Strains from Soils of the Amazon Region as Bradyrhizobium Viridifuturi (Symbiovar Tropici). Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões-Araújo, J.L.; Leite, J.; Marie Rouws, L.F.; Passos, S.R.; Xavier, G.R.; Rumjanek, N.G. Zilli JÉ Draft Genome Sequence of Bradyrhizobium Sp Strain BR3262, an Effective Microsymbiont Recommended for Cowpea Inoculation in Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. Publ. Braz. Soc. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 783–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menna, P.; Barcellos, F.G.; Hungria, M. Phylogeny and Taxonomy of a Diverse Collection of Bradyrhizobium Strains Based on Multilocus Sequence Analysis of the 16S rRNA Gene, ITS Region and glnII, recA, atpD and dnaK Genes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2934–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepa, M.S.; diCenzo, G.C.; Hungria, M. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Bradyrhizobium Strains with Natural Variability in the Efficiency of Nitrogen Fixation, Competitiveness, and Adaptation to Stressful Edaphoclimatic Conditions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0026024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Agnol, R.F.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Ormeño-Orrillo, E.; Rogel, M.A.; Delamuta, J.R.M.; Andrade, D.S.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Hungria, M. Rhizobium Freirei Sp. Nov., a Symbiont of Phaseolus Vulgaris That Is Very Effective at Fixing Nitrogen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 4167–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostasso, L.; Mostasso, F.L.; Dias, B.G.; Vargas, M.A.T.; Hungria, M. Seleção de Estirpes de Rizóbio de Feijão (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Para o Cerrado Brasileiro. Field Crops Res. 2002, 73, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.W.; Frederick, L.R. Rhizobium. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; Part 2; pp. 1043–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, D.O.; Date, R.A. Legume Bacteriology. In Tropical Pasture Research: Principles and Methods; Shaw, N.H., Bryan, W.W., Eds.; CAB Publisher: Brisbane, Australia, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, W. Climatologia: Com um Estudo dos Climas da Terra; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, H.G.; Jacomine, P.K.T.; Dos Anjos, L.H.; De Oliveira, V.A.; Lumbreras, J.F.; Coelho, M.R.; De Almeida, J.A.; De Araujo Filho, J.C.; De Oliveira, J.B.; Cunha, T.J.F. Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos, 5th ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2018; ISBN 978-85-7035-817-2. [Google Scholar]

- Döbereiner, J.; Andrade, V.d.O.; Baldani, V.L.D. Cell Culture for the Production of Inoculants; Embrapa-CNPAB. Documentos, 110; Embrapa Agrobiologia: Seropédica, Brazil, 1999; 38p, Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/624371 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Christopher, M.; Macdonald, B.; Yeates, S.; Seymour, N. Wild bradyrhizobia that occur in the Burdekin region of Queensland are as effective as commercial inoculum for mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.)) and black gram (Vigna mungo (L.)) in fixing nitrogen and dry matter production. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 124, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Risal, C.P.; Djedidi, S.; Dhakal, D.; Ohkama-Ohtsu, N.; Sekimoto, H.; Yokoyama, T. Diversidade Filogenética e Funcionamento Simbiótico Em Bradyrhizobia de Feijão-Mungo (Vigna Radiata L. Wilczek) de Regiões Agroecológicas Contrastantes Do Nepal. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 35, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.H.; Shang, J.Y.; Wang, E.T.; Chen, L.; Huo, B.; Sui, X.H.; Tian, C.F.; Chen, W.F.; Chen, W.X. Multiple Genes of Symbiotic Plasmid and Chromosome in Type II Peanut Bradyrhizobium Strains Corresponding to the Incompatible Symbiosis with Vigna Radiata. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htwe, A.Z.; Yamakawa, T.; Ishibashi, M.; Tsurumaru, H. Isolation and Characterization of Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.) Rhizobia in Myanmar. Symbiosis 2024, 94, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diatta, A.A.; Thomason, W.E.; Abaye, O.; Thompson, T.L.; Battaglia, M.L.; Vaughan, L.J.; Lo, M. Assessment of Nitrogen Fixation by Mung Bean Genotypes in Different Soil Textures Using 15N Natural Abundance Method. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 2230–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Hu, G.; Hu, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ning, K. Comparative Genomics Analysis Reveals Genetic Characteristics and Nitrogen Fixation Profile of Bradyrhizobium. iScience 2024, 27, 108948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piromyou, P.; Nguyen, H.P.; Songwattana, P.; Boonchuen, P.; Teamtisong, K.; Tittabutr, P.; Boonkerd, N.; Alisha Tantasawat, P.; Göttfert, M.; Okazaki, S.; et al. The Bradyrhizobium Diazoefficiens Type III Effector NopE Modulates the Regulation of Plant Hormones towards Nodulation in Vigna Radiata. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piromyou, P.; Pruksametanan, N.; Nguyen, H.P.; Songwattana, P.; Wongdee, J.; Nareephot, P.; Greetatorn, T.; Teamtisong, K.; Tittabutr, P.; Boonkerd, N.; et al. NopP2 Effector of Bradyrhizobium Elkanii USDA61 Is a Determinant of Nodulation in Vigna radiata Cultivars. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, V.O.; Carvalho, R.H.; Leite, A.B.C.; Santos, D.M.T.; Freitas, K.M.; Zilli, J.É.; Xavier, G.R.; Rumjanek, N.G. Cross-Inoculation of Elite Commercial Bradyrhizobium Strains from Cowpea and Soybean in Mung Bean and Comparison with Mung Bean Isolates. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 4356–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, J.É.; Neto, M.L.d.S.; Júnior, I.F.; Perin, L.; de Melo, A.R. Resposta do feijão-caupi à inoculação com estirpes de Bradyrhizobium recomendadas para a soja. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2011, 35, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hakim, S.; Mirza, B.S.; Imran, A.; Zaheer, A.; Yasmin, S.; Mubeen, F.; Mclean, J.E.; Mirza, M.S. Illumina Sequencing of 16S rRNA Tag Shows Disparity in Rhizobial and Non-Rhizobial Diversity Associated with Root Nodules of Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.) Growing in Different Habitats in Pakistan. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 231, 126356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.A.H.; Mian, M.H. Effect of Bradyrhizobium Inoculation on Nodulation, Biomass Production and Yield of Mung Bean. Bangladesh Journal of Microbiology. Bangladesh J. Microbiol. 2007, 24, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, D.M.T.; Leite, A.B.C.; Favero, V.O.; Zonta, E.; Rumjanek, N.G.; Xavier, G.R. Desempenho de Feijão-Mungo Em Função de Diferentes Níveis de Nitrogênio. In Proceedings of the 5th ABC Symposium on Soils and Environmental Health, Brasília, Brazil, 30–31 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, V.O.; Carvalho, R.H.; Motta, V.M.; Leite, A.B.C.; Coelho, M.R.R.; Xavier, G.R.; Rumjanek, N.G.; Urquiaga, S. Bradyrhizobium as the Only Rhizobial Inhabitant of Mung Bean (Vigna Radiata) Nodules in Tropical Soils: A Strategy Based on Microbiome for Improving Biological Nitrogen Fixation Using Bio-Products. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 602645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, S.; Mirza, B.S.; Zaheer, A.; Mclean, J.E.; Imran, A.; Yasmin, S.; Sajjad Mirza, M. Retrieved 16S rRNA and nifH Sequences Reveal Co-Dominance of Bradyrhizobium and Ensifer (Sinorhizobium) Strains in Field-Collected Root Nodules of the Promiscuous Host Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.N.; Vo, T.M.T.; Nguyen, M.K.; Pham, C.D.; Phung, T.T.; Doan, T.M.T.; Le, T.P.T.; Nguyen, N.A.V.; Ta, N.M.P.; Tran, T.K.X.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Rhizobium Spp. and Bradyrhizobium Spp. from Legume Nodules. Eng. Technol. 2023, 12, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, S.; Imran, A.; Hussain, M.S.; Mirza, M.S. RNA-Seq Analysis of Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.) Roots Shows Differential Gene Expression and Predicts Regulatory Pathways Responding to Taxonomically Different Rhizobia. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 275, 127451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, K.E.C.; Júnior, C.V.T.; Guimarães, A.P.; da Silva, M.A.; Alves, B.J.R.; Urquiaga, S.; Boddey, R.M. Natural Abundance of 15N of N Derived from the Atmosphere by Different Strains of Bradyrhizobium in Symbiosis with Soybean Plants. Ciênc. Rural 2019, 49, e20180265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathu, S.; Herrmann, L.; Pypers, P.; Matiru, V.; Mwirichia, R.; Lesueur, D. Potential of Indigenous Bradyrhizobia versus Commercial Inoculants to Improve Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) and Green Gram (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek.) Yields in Kenya. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 58, 750–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herridge, D.F.; Robertson, M.J.; Cocks, B.; Peoples, M.B.; Holland, J.F.; Heuke, L. Low Nodulation and Nitrogen Fixation of Mungbean Reduce Biomass and Grain Yields. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2005, 45, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.C.P.; Hungria, M.; Sprent, J.I. The Physiology of Nitrogen Fixation in Tropical Grain Legumes. Plant Sci. 1987, 6, 267–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argaw, A.; Tsigie, A. The inorganic N requirement, nodulation and yield of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) as influenced by inherent soil fertility of eastern Ethiopia. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 1842–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, E.; Carro, L.; Flores-Felix, J.D.; Menendez, E.; Ramirez-Bahena, M.H.; Peix, A. Bacteria-Inducing Legume Nodules Involved in the Improvement of Plant Growth, Health and Nutrition. In Microbiome in Plant Health and Disease; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Longatti, S.M.; Marra, L.M.; Lima Soares, B.; Bomfeti, C.A.; da Silva, K.; Avelar Ferreira, P.A.; de Souza Moreira, F.M. Bacteria Isolated from Soils of the Western Amazon and from Rehabilitated Bauxite-Mining Areas Have Potential as Plant Growth Promoters. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, L.M.; de Oliveira, S.M.; Soares, C.R.F.S.; Moreira, F.M.d.S. Solubilisation of Inorganic Phosphates by Inoculant Strains from Tropical Legumes. Sci. Agric. 2011, 68, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Leguminous Species from Which It Was Isolated | Bacterial Strains (SEMIA) | Other Designations | Bacterial Species ** | Technical–Scientific Publications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cowpea | SEMIA 6463 | =BR 3301 or INPA 3-11B | Bradyrhizobium amazonense | de Souza Moreira et al. (2024) [11] |

| SEMIA 6461 | =BR 3302 and UFLA 3-84) | Bradyrhizobium viridifuturi | da Costa et al. (2019) [12] | |

| SEMIA 6462 | =BR 3267 | Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense | Simões-Araújo et al. (2016) [13] | |

| SEMIA 6464 | =BR 3262 | Bradyrhizobium pachyrhizi | Simões-Araújo et al. (2016) [13] | |

| Soybean | SEMIA 5080 | =BR 85 | Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens | Menna et al. (2009); Klepa et al. (2024) [14,15] |

| SEMIA 5079 | =BR 86 | Bradyrhizobium japonicum | Menna et al. (2009); Klepa et al. (2024) [14,15] | |

| SEMIA 587 | =BR 96 | Bradyrhizobium elkanii | Menna et al. (2009); Klepa et al. (2024) [14,15] | |

| SEMIA 5019 | =BR 29 | Bradyrhizobium elkanii | Menna et al. (2009); Klepa et al. (2024) [14,15] | |

| Common bean | SEMIA 4077 | =BR 322 | Rhizobium tropici | Dall’Agnol et al. (2013) [16] |

| SEMIA 4088 | =BR 534 | Rhizobium tropici | Mostasso et al. (2002) [17] | |

| SEMIA 4080 | =BR 520 | Rhizobium freirei | Klepa et al. (2024) [15] |

| Rhizobial Strains | Leguminous Plant | NN | NDM | RDM | SDM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule Plant−1 | mg Plant−1 | g Plant−1 | |||

| BR 3302 | cowpea | 49 a ** | 138 a | 0.294 a | 0.930 a |

| BR 96 | soybean | 70 a | 98 b | 0.178 bc | 0.582 b |

| BR 3301 | cowpea | 72 a | 89 b | 0.200 ab | 0.590 b |

| BR 3262 | cowpea | 2 b | 6 c | 0.122 bc | 0.222 c |

| BR 3267 | cowpea | 1 b | 3 c | 0.114 bc | 0.212 c |

| BR 29 | soybean | 3 b | 15 c | 0.138 bc | 0.264 c |

| BR 85 | soybean | 0 b | 0 c | 0.126 bc | 0.182 c |

| BR 86 | soybean | 0 b | 0 c | 0.114 bc | 0.190 c |

| BR 322 | common bean | 0 b | 0 c | 0.110 bc | 0.174 c |

| BR 534 | common bean | 0 b | 0 c | 0.110 bc | 0.204 c |

| BR 520 | common bean | 0 b | 0 c | 0.094 c | 0.180 c |

| Non-inoculated control | - | 0 b | 0 c | 0.112 bc | 0.188 c |

| Treatment | * | * | * | * | |

| Rhizobial Strains | NN | NDM |

|---|---|---|

| Nodule Plant−1 | mg Plant−1 | |

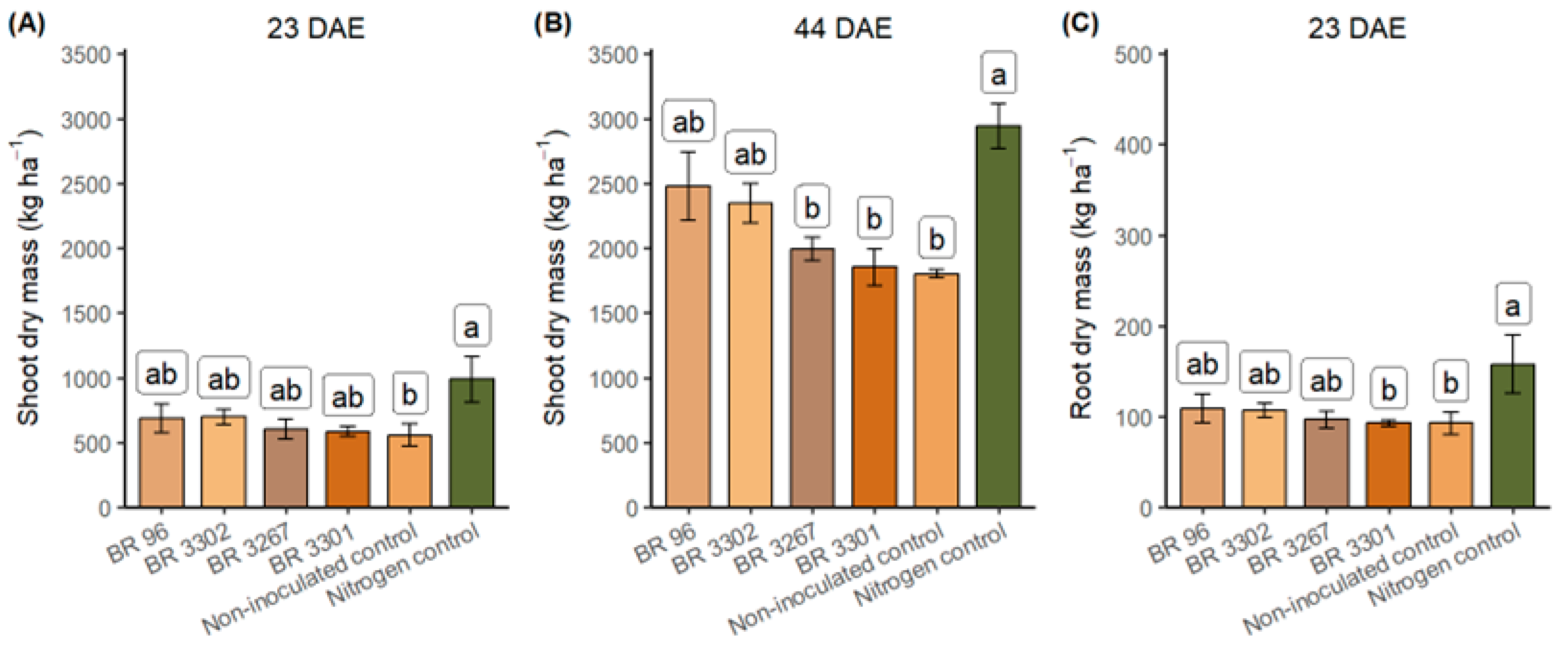

| BR 96 | 49.3 | 111.5 a * |

| BR 3302 | 43.1 | 96.0 a |

| BR 3267 | 44.1 | 92.8 ab |

| BR 3301 | 37.6 | 80.2 ab |

| Non-inoculated control | 45.4 | 91.3 ab |

| Nitrogen control (240 kg N ha−1) | 25.4 | 31.7 b |

| Treatment | ns | * |

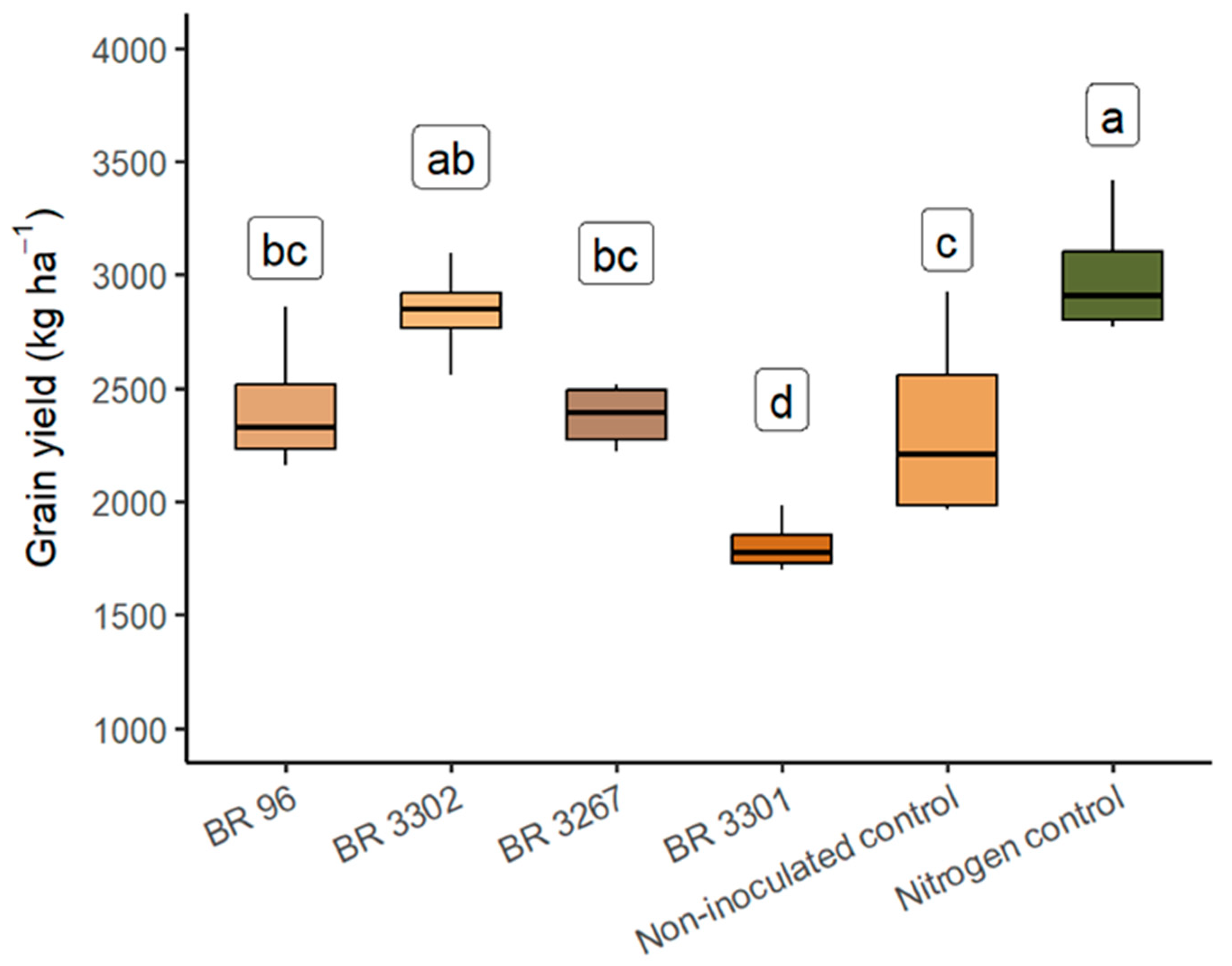

| Rhizobial Strains | SDM | N Content | TN | Ndfa | N-Fixed | Soil N-Uptake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kg ha−1 | % | kg ha−1 | % | kg ha−1 | ||

| Kjeldahl method | ||||||

| BR 96 | 2479.3 ab | 2.96 | 73.97 ab * | - | - | - |

| BR 3302 | 2347.3 ab | 2.99 | 71.25 ab | - | - | - |

| BR 3267 | 1992.7 b | 3.06 | 61.15 b | - | - | - |

| BR 3301 | 1854.2 b | 2.71 | 50.47 b | - | - | - |

| Non-inoculated control | 1802.9 b | 3.04 | 54.97 b | - | - | - |

| Nitrogen control (240 kg N ha−1) | 2941.0 a | 3.40 | 100.66 a | - | - | - |

| Treatment | * | ns | * | nd | nd | nd |

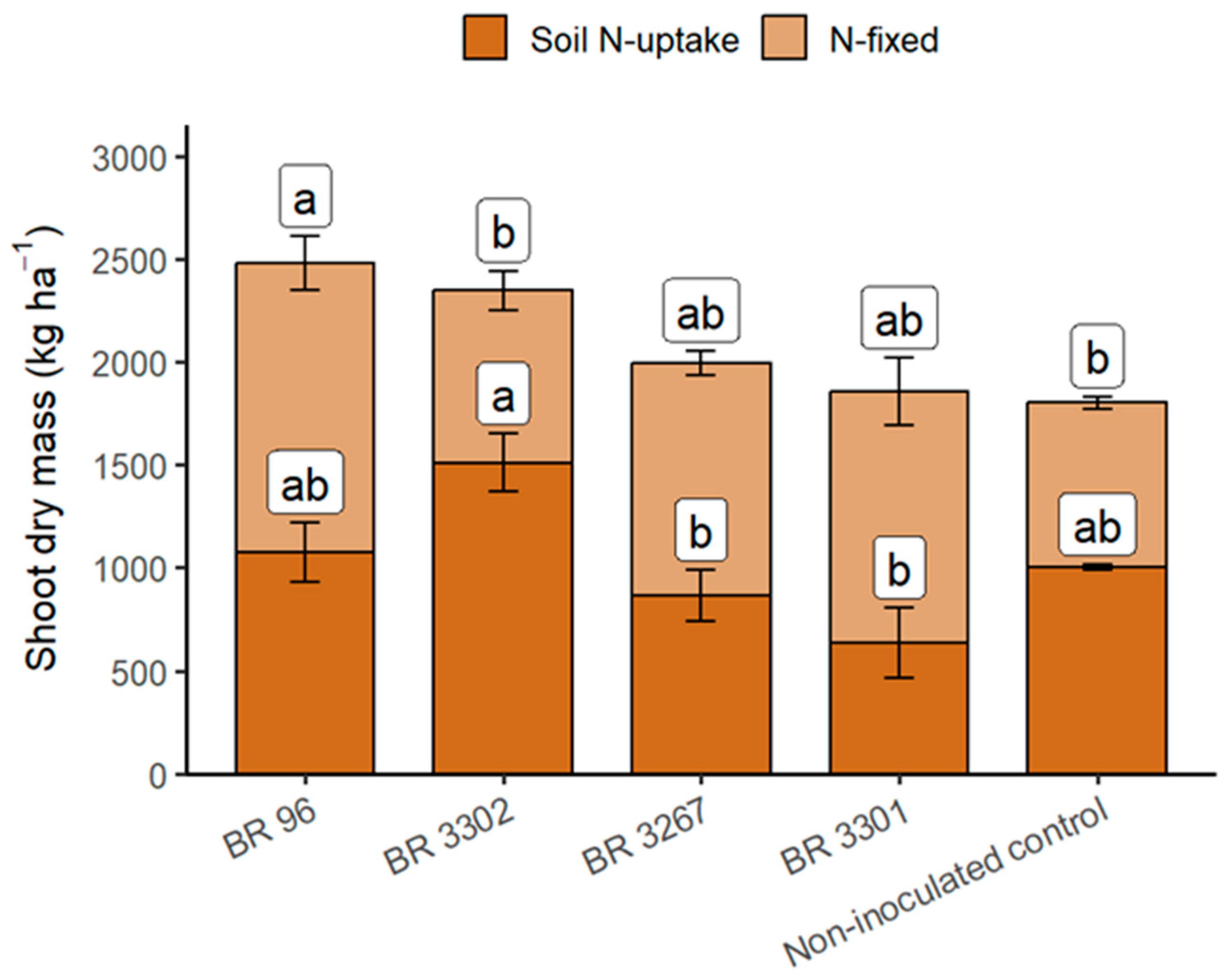

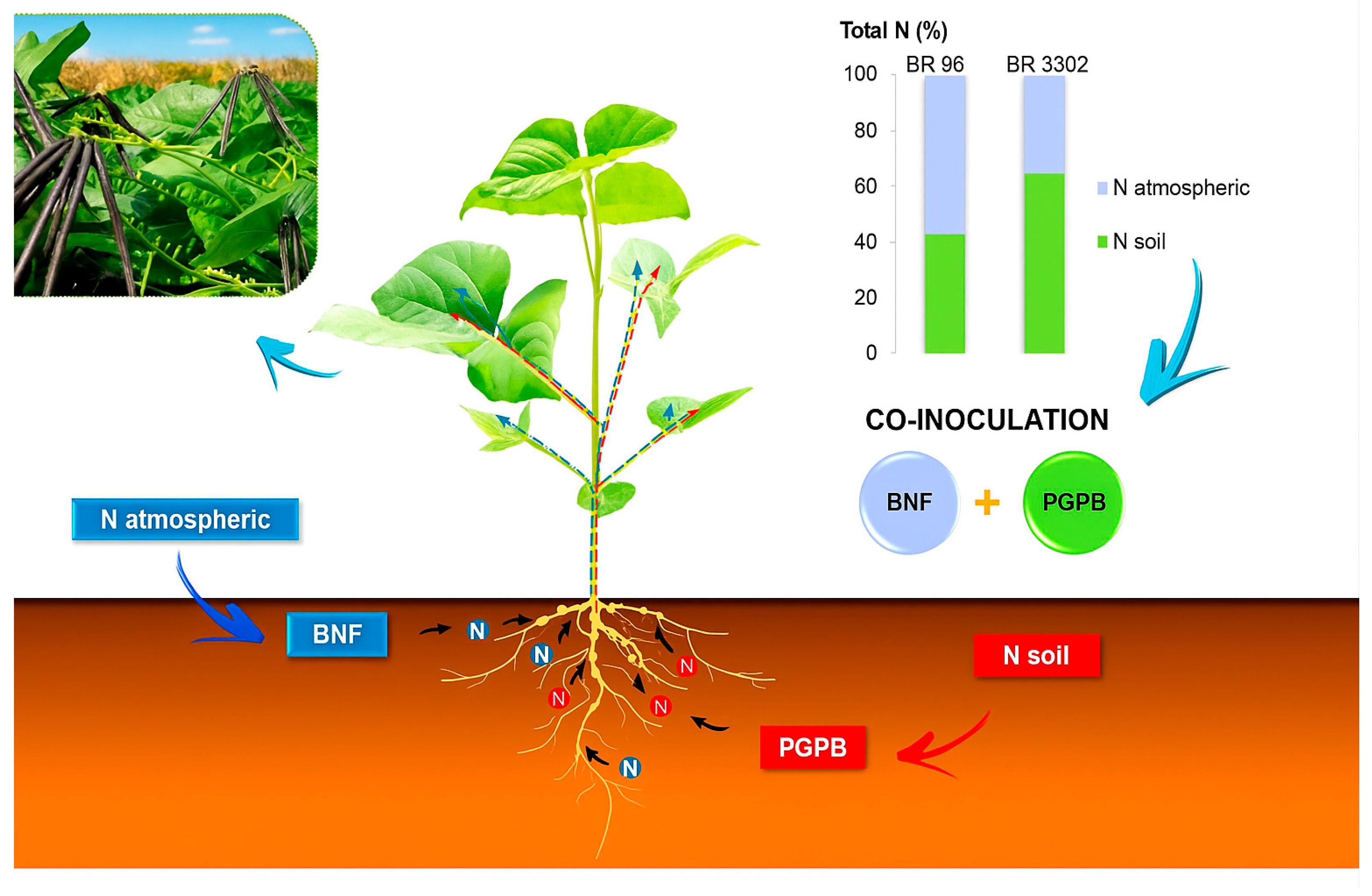

| Dumas method | ||||||

| BR 96 | 2479.3 | 2.51 | 62.03 a * | 57.12 ab | 35.27 a | 26.75 ab |

| BR 3302 | 2347.3 | 2.47 | 58.74 ab | 35.75 b | 20.88 b | 37.86 a |

| BR 3267 | 1992.7 | 2.53 | 50.58 ab | 57.02 ab | 28.68 ab | 21.90 b |

| BR 3301 | 1854.2 | 2.16 | 40.21 b | 66.15 a | 26.25 ab | 13.96 b |

| Non-inoculated control | 1802.9 | 2.32 | 41.93 ab | 44.27 ab | 18.54 b | 23.38 ab |

| Treatment | ns | ns | * | * | * | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, D.M.T.d.; Favero, V.O.; Leite, A.B.C.; Santos, G.d.C.R.d.; Almeida, J.C.d.; Batista, J.N.; Pereira, W.; Zonta, E.; Urquiaga, S.; Rumjanek, N.G.; et al. Harnessing Rhizobial Inoculation for Sustainable Nitrogen Management in Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.). Plants 2025, 14, 3695. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233695

Santos DMTd, Favero VO, Leite ABC, Santos GdCRd, Almeida JCd, Batista JN, Pereira W, Zonta E, Urquiaga S, Rumjanek NG, et al. Harnessing Rhizobial Inoculation for Sustainable Nitrogen Management in Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.). Plants. 2025; 14(23):3695. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233695

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Dieini Melissa Teles dos, Vinício Oliosi Favero, Ana Beatriz Carneiro Leite, Giulia da Costa Rodrigues dos Santos, Jaqueline Carvalho de Almeida, Josimar Nogueira Batista, Willian Pereira, Everaldo Zonta, Segundo Urquiaga, Norma Gouvêa Rumjanek, and et al. 2025. "Harnessing Rhizobial Inoculation for Sustainable Nitrogen Management in Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.)" Plants 14, no. 23: 3695. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233695

APA StyleSantos, D. M. T. d., Favero, V. O., Leite, A. B. C., Santos, G. d. C. R. d., Almeida, J. C. d., Batista, J. N., Pereira, W., Zonta, E., Urquiaga, S., Rumjanek, N. G., & Xavier, G. R. (2025). Harnessing Rhizobial Inoculation for Sustainable Nitrogen Management in Mung Bean (Vigna radiata L.). Plants, 14(23), 3695. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233695