Overexpression of SlMADS48 Alters the Structure of Inflorescence and the Sizes of Sepal and Fruit in Tomato

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

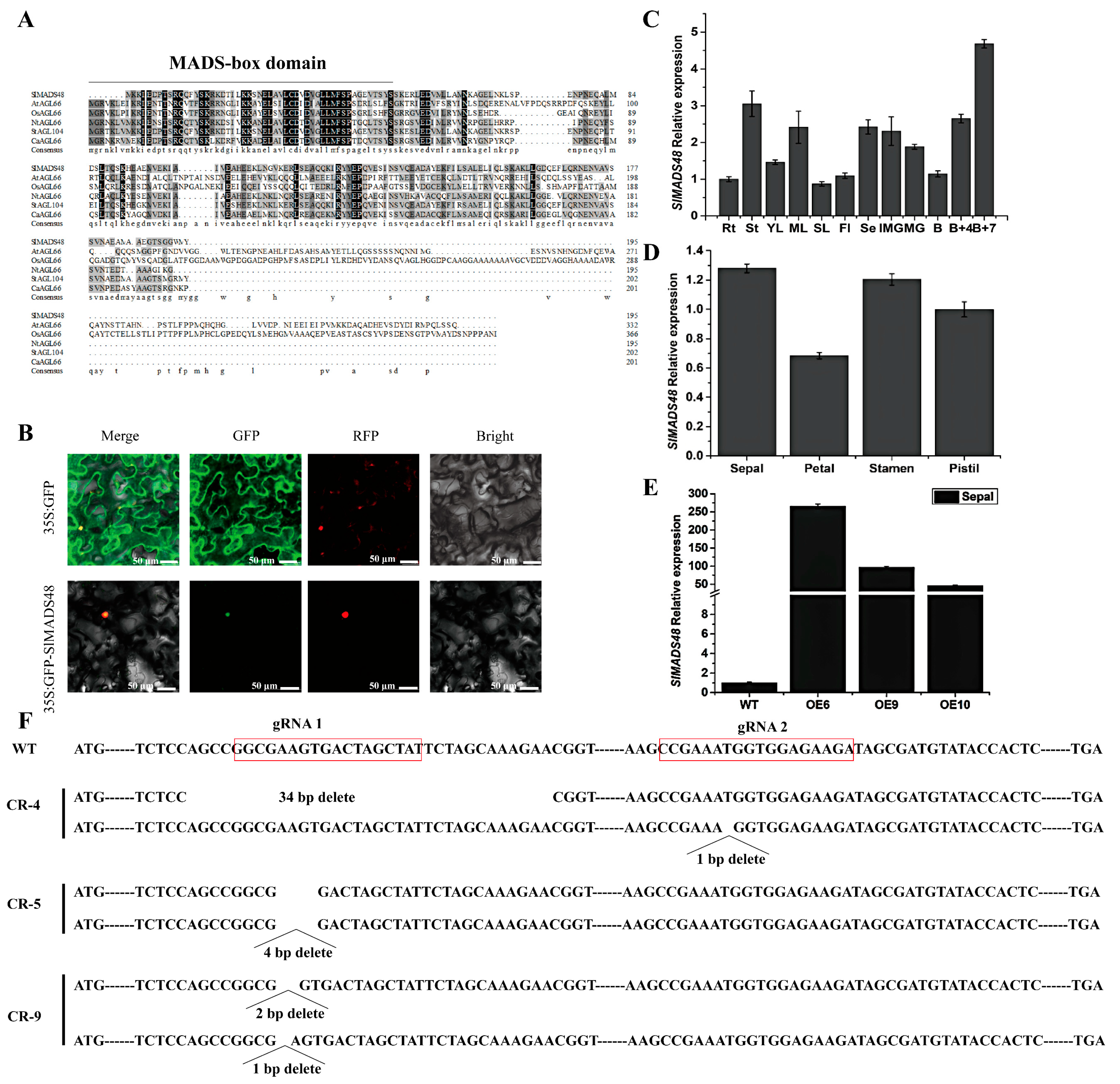

2.1. Characterization and Tissue Expression Pattern Analysis of the SlMADS48 Gene

2.2. Overexpression of SlMADS48 Generated Elongated Sepals

2.3. SlMADS48 Interacted with MBP21, JOINTLESS, MC, and FYFL

2.4. Transcriptome Analysis of Sepals Between OE-SlMADS48 and WT

2.5. Elongated Sepals Possibly Associated with Increased Gibberellin

2.6. Overexpression of SlMADS48 Alters Inflorescence Structure

2.7. Overexpression of SlMADS48 Changes Fruit Size with Altered Endogenous Hormones

2.8. RNA-Seq of 25DPA Fruit Between WT and OE-SlMADS48

2.9. Analyses of DEGs in 25DPA Fruit Between WT and OE-SlMADS48 Lines and Validation by qRT-PCR

2.10. SlMADS48 Directly Targeted SlIAA29 and SlcycD6;1

3. Discussion

3.1. Longer Sepals of OE-SlMADS48 Lines Were Possibly Caused by Increased Gibberellin and Interaction with Proteins Involved in Sepal Development

3.2. SlMADS48 Functions in Inflorescence Development by Interacting with FUL1, FUL2, MBP20, and TM29, and Directly Targeting SlTM3

3.3. SlMADS48 Directly Targets SlIAA29 and SlcycD6;1, Further Influencing Fruit Size via Auxin and Cytokinin Pathways

3.4. Application in Future Breeding

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Construction of Expression Vector and Tomato Transformation

4.3. Extraction of Total RNA and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Assay

4.4. Histological Analysis

4.5. Determination of Endogenous Hormones in Plants

4.6. RNA-Seq Analysis

4.7. Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Assay

4.8. Bimolecular Fluorescent Complementation (BiFC) Assay

4.9. Dual-LUC Assay

4.10. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

4.11. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation–Quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) Assay

4.12. Statistical Analysis and Heatmap Drawing

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, K.; Lenhard, M. Genetic control of plant organ growth. New Phytol. 2011, 191, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Chen, G.; Guo, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Tian, S.; Hu, Z. Silencing SlAGL6, a tomato AGAMOUS-LIKE6 lineage gene, generates fused sepal and green petal. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Liao, C.; Zhu, M.; Chen, G. Suppression of a tomato SEPALLATA MADS-box gene, SlCMB1, generates altered inflorescence architecture and enlarged sepals. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2018, 272, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Hu, Z.; Yin, W.; Yu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G. The tomato floral homeotic protein FBP1-like gene, SlGLO1, plays key roles in petal and stamen development. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Huang, B.; Tang, N.; Jian, W.; Zou, J.; Chen, J.; Cao, H.; Habib, S.; Dong, X.; Wei, W.; et al. The MADS-Box Gene SlMBP21 Regulates Sepal Size Mediated by Ethylene and Auxin in Tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 2241–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Zhu, B.; Zhu, H.; Grierson, D.; Luo, Y.; Fu, D. A MADS-box transcription factor, SlMADS1, interacts with SlMACROCALYX to regulate tomato sepal growth. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2022, 322, 111366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zheng, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; Gao, S.; Zhang, C.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, B.; et al. The tomato CONSTANS-LIKE protein SlCOL1 regulates fruit yield by repressing SFT gene expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Xiang, Y.; Xian, Z.; Li, Z. Ectopic expression of SlAGO7 alters leaf pattern and inflorescence architecture and increases fruit yield in tomato. Physiol. Plant. 2016, 157, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wagner, D. Plant Inflorescence Architecture: The Formation, Activity, and Fate of Axillary Meristems. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2020, 12, a034652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAlister, C.A.; Park, S.J.; Jiang, K.; Marcel, F.; Bendahmane, A.; Izkovich, Y.; Eshed, Y.; Lippman, Z.B. Synchronization of the flowering transition by the tomato TERMINATING FLOWER gene. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippman, Z.B.; Cohen, O.; Alvarez, J.P.; Abu-Abied, M.; Pekker, I.; Paran, I.; Eshed, Y.; Zamir, D. The making of a compound inflorescence in tomato and related nightshades. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, U.; Lippman, Z.B.; Zamir, D. The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, Q.; Vayssières, A.; Ó’Maoiléidigh, D.S.; Yang, X.; Vincent, C.; Bertran Garcia de Olalla, E.; Cerise, M.; Franzen, R.; Coupland, G. MicroRNA172 controls inflorescence meristem size through regulation of APETALA2 in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2022, 235, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussin, S.H.; Wang, H.; Tang, S.; Zhi, H.; Tang, C.; Zhang, W.; Jia, G.; Diao, X. SiMADS34, an E-class MADS-box transcription factor, regulates inflorescence architecture and grain yield in Setaria italica. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 105, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevskaya, O.N.; Meng, X.; Selinger, D.A.; Deschamps, S.; Hermon, P.; Vansant, G.; Gupta, R.; Ananiev, E.V.; Muszynski, M.G. Involvement of the MADS-box gene ZMM4 in floral induction and inflorescence development in maize. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 2054–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacharrón, J.; Saedler, H.; Theissen, G. Expression of MADS box genes ZMM8 and ZMM14 during inflorescence development of Zea mays discriminates between the upper and the lower floret of each spikelet. Dev. Genes Evol. 1999, 209, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Bai, J.; Sun, S.; Song, J.; Li, R.; Cui, X. Antagonistic regulation of target genes by the SISTER OF TM3-JOINTLESS2 complex in tomato inflorescence branching. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2062–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, I.E.; Roelofsen, C.; Angenent, G.C.; Bemer, M. TM3 and STM3 Promote Flowering Together with FUL2 and MBP20, but Act Antagonistically in Inflorescence Branching in Tomato. Plants 2023, 12, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, P.; Sharrocks, A.D. The MADS-box family of transcription factors. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 229, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz-Sommer, Z.; Huijser, P.; Nacken, W.; Saedler, H.; Sommer, H. Genetic Control of Flower Development by Homeotic Genes in Antirrhinum majus. Science 1990, 250, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Guo, X.; Tian, S.; Chen, G. Genome-Wide Analysis of the MADS-Box Transcription Factor Family in Solanum lycopersicum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah-Zawawi, M.R.; Ahmad-Nizammuddin, N.F.; Govender, N.; Harun, S.; Mohd-Assaad, N.; Mohamed-Hussein, Z.A. Comparative genome-wide analysis of WRKY, MADS-box and MYB transcription factor families in Arabidopsis and rice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Yu, D.; Wang, D.; Guo, D.; Guo, C. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the MADS-box gene family in soybean. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 3901–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Chen, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zou, Q. Genome-Wide Analysis of the MADS-Box Gene Family in Maize: Gene Structure, Evolution, and Relationships. Genes 2021, 12, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Luo, W.; Yang, C.; Ding, P.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, L.; Chang, Z.; Geng, H.; Wang, P.; et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MADS-box gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Dong, Q.; Ji, Z.; Chi, F.; Cong, P.; Zhou, Z. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MADS-box gene family in apple. Gene 2015, 555, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.; Suh, S.S.; Lee, H.; Choi, K.R.; Hong, C.B.; Paek, N.C.; Kim, S.G.; Lee, I. The SOC1 MADS-box gene integrates vernalization and gibberellin signals for flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2003, 35, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelán-Muñoz, N.; Herrera, J.; Cajero-Sánchez, W.; Arrizubieta, M.; Trejo, C.; García-Ponce, B.; Sánchez, M.P.; Álvarez-Buylla, E.R.; Garay-Arroyo, A. MADS-Box Genes Are Key Components of Genetic Regulatory Networks Involved in Abiotic Stress and Plastic Developmental Responses in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, B.; Hu, L.; Li, M.; Su, W.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Jin, Z. Involvement of a banana MADS-box transcription factor gene in ethylene-induced fruit ripening. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Ma, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y.; Chen, M. Overexpression of BnaAGL11, a MADS-Box Transcription Factor, Regulates Leaf Morphogenesis and Senescence in Brassica napus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 3420–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cruz, K.V.; García-Ponce, B.; Garay-Arroyo, A.; Sanchez, M.P.; Ugartechea-Chirino, Y.; Desvoyes, B.; Pacheco-Escobedo, M.A.; Tapia-López, R.; Ransom-Rodríguez, I.; Gutierrez, C.; et al. The MADS-box XAANTAL1 increases proliferation at the Arabidopsis root stem-cell niche and participates in transition to differentiation by regulating cell-cycle components. Ann. Bot. 2016, 118, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, B.; Bai, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. The MADS-box transcription factor GlMADS1 regulates secondary metabolism in Ganoderma lucidum. Mycologia 2021, 113, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.S.; Shim, W.B. The role of MADS-box transcription factors in secondary metabolism and sexual development in the maize pathogen Fusarium verticillioides. Microbiology 2013, 159, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renau-Morata, B.; Carrillo, L.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J.; Molina, R.V.; Martí, R.; Domínguez-Figueroa, J.; Vicente-Carbajosa, J.; Medina, J.; Nebauer, S.G. The targeted overexpression of SlCDF4 in the fruit enhances tomato size and yield involving gibberellin signalling. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.; Song, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, N.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Cytokinins is involved in regulation of tomato pericarp thickness and fruit size. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Q.; Qin, L.; Pan, C.; Lamin-Samu, A.T.; Lu, G. Tomato AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 5 regulates fruit set and development via the mediation of auxin and gibberellin signaling. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, N.; van Nocker, S.; Li, Z.; Gao, M.; Wang, X. Role of grapevine SEPALLATA-related MADS-box gene VvMADS39 in flower and ovule development. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 111, 1565–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Zhang, X.; Tobón, E.; Ambrose, B.A. The Arabidopsis B-sister MADS-box protein, GORDITA, represses fruit growth and contributes to integument development. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010, 62, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Ma, J.; Zhu, K.; Zhao, J.; Yang, H.; Feng, L.; Nie, L.; Zhao, W. The MADS-box transcription factor CmFYF promotes the production of male flowers and inhibits the fruit development in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 221, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlova, R.; Rosin, F.M.; Busscher-Lange, J.; Parapunova, V.; Do, P.T.; Fernie, A.R.; Fraser, P.D.; Baxter, C.; Angenent, G.C.; de Maagd, R.A. Transcriptome and metabolite profiling show that APETALA2a is a major regulator of tomato fruit ripening. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, T.; Zhao, Z.; Cui, B.; Chen, G. Overexpression of a novel MADS-box gene SlFYFL delays senescence, fruit ripening and abscission in tomato. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrebalov, J.; Ruezinsky, D.; Padmanabhan, V.; White, R.; Medrano, D.; Drake, R.; Schuch, W.; Giovannoni, J. A MADS-box gene necessary for fruit ripening at the tomato ripening-inhibitor (rin) locus. Science 2002, 296, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak, E.J.; Irish, E.E. Interactions between jointless and wild-type tomato tissues during development of the pedicel abscission zone and the inflorescence meristem. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berger, Y.; Harpaz-Saad, S.; Brand, A.; Melnik, H.; Sirding, N.; Alvarez, J.P.; Zinder, M.; Samach, A.; Eshed, Y.; Ori, N. The NAC-domain transcription factor GOBLET specifies leaflet boundaries in compound tomato leaves. Development 2009, 136, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Folter, S.; Shchennikova, A.V.; Franken, J.; Busscher, M.; Baskar, R.; Grossniklaus, U.; Angenent, G.C.; Immink, R.G. A Bsister MADS-box gene involved in ovule and seed development in petunia and Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006, 47, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaro, R.; Immink, R.G.; Ferioli, V.; Bernasconi, B.; Byzova, M.; Angenent, G.C.; Kater, M.; Colombo, L. Ovule-specific MADS-box proteins have conserved protein-protein interactions in monocot and dicot plants. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2002, 268, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shchennikova, A.V.; Shulga, O.A.; Immink, R.; Skryabin, K.G.; Angenent, G.C. Identification and characterization of four chrysanthemum MADS-box genes, belonging to the APETALA1/FRUITFULL and SEPALLATA3 subfamilies. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leseberg, C.H.; Eissler, C.L.; Wang, X.; Johns, M.A.; Duvall, M.R.; Mao, L. Interaction study of MADS-domain proteins in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2253–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelissen, H.; Rymen, B.; Jikumaru, Y.; Demuynck, K.; Van Lijsebettens, M.; Kamiya, Y.; Inzé, D.; Beemster, G.T. A local maximum in gibberellin levels regulates maize leaf growth by spatial control of cell division. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; He, Y.; Niu, S.; Zhang, Y. A YABBY gene CRABS CLAW a (CRCa) negatively regulates flower and fruit sizes in tomato. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2022, 320, 111285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jathar, V.; Saini, K.; Chauhan, A.; Rani, R.; Ichihashi, Y.; Ranjan, A. Spatial control of cell division by GA-OsGRF7/8 module in a leaf explaining the leaf length variation between cultivated and wild rice. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; El-Sappah, A.H.; Liang, Y. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of the Development of Sepal Morphology in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.P.; Phillips, A.L.; Croker, S.J.; García-Lepe, R.; Lewis, M.J.; Hedden, P. Modification of gibberellin production and plant development in Arabidopsis by sense and antisense expression of gibberellin 20-oxidase genes. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999, 17, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Cai, X.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide analysis of the cyclin gene family in tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 15, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, M.; de Jager, S.M.; Gruissem, W.; Murray, J.A. Global analysis of the core cell cycle regulators of Arabidopsis identifies novel genes, reveals multiple and highly specific profiles of expression and provides a coherent model for plant cell cycle control. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005, 41, 546–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafati, M.; Frangne, N.; Hernould, M.; Chevalier, C.; Gévaudant, F. Functional characterization of the tomato cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor SlKRP1 domains involved in protein-protein interactions. New Phytol. 2010, 188, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, M.V.G.; Périlleux, C.; Morin, H.; Huerga-Fernandez, S.; Latrasse, D.; Benhamed, M.; Bendahmane, A. Natural and induced loss of function mutations in SlMBP21 MADS-box gene led to jointless-2 phenotype in tomato. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.E.; Wang, H. Suppression of SlHDT1 expression increases fruit yield and decreases drought and salt tolerance in tomato. Plant Mol. Biol. 2024, 114, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périlleux, C.; Lobet, G.; Tocquin, P. Inflorescence development in tomato: Gene functions within a zigzag model. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Jiang, K.; Schatz, M.C.; Lippman, Z.B. Rate of meristem maturation determines inflorescence architecture in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Lubini, G.; Hernandes-Lopes, J.; Rijnsburger, K.; Veltkamp, V.; de Maagd, R.A.; Angenent, G.C.; Bemer, M. FRUITFULL-like genes regulate flowering time and inflorescence architecture in tomato. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, S.; Wu, J.; Li, R.; Wang, H.; Cui, X. SISTER OF TM3 activates FRUITFULL1 to regulate inflorescence branching in tomato. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampomah-Dwamena, C.; Morris, B.A.; Sutherland, P.; Veit, B.; Yao, J.L. Down-regulation of TM29, a tomato SEPALLATA homolog, causes parthenocarpic fruit development and floral reversion. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Jia, W.; Fu, D. NAC transcription factor NOR-like1 regulates tomato fruit size. Planta 2023, 258, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, S.; Wang, L.; Luo, Z.; Ai, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; et al. ZjWRKY23 and ZjWRKY40 Promote Fruit Size Enlargement by Targeting and Downregulating Cytokinin Oxidase/Dehydrogenase 5 Expression in Chinese Jujube. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 18046–18058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Pang, E.; Lu, T.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Li, Q. Girdling promotes tomato fruit enlargement by enhancing fruit sink strength and triggering cytokinin accumulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1174403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.; Yu, W.; Yuan, H.; Yue, P.; Wei, Y.; Wang, A. Endogenous Auxin Content Contributes to Larger Size of Apple Fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 592540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, M.; Yang, H.; Yi, H.; Wu, J. Transcription factor CsMYB77 negatively regulates fruit ripening and fruit size in citrus. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, J.; Battaglia, R.; Bagnaresi, P.; Lucini, L.; Marocco, A. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of ZmYUC1 mutant reveals the role of auxin during early endosperm formation in maize. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2019, 281, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Clevenger, J.P.; Illa-Berenguer, E.; Meulia, T.; van der Knaap, E.; Sun, L. A Comparison of sun, ovate, fs8.1 and Auxin Application on Tomato Fruit Shape and Gene Expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, S.; De Rybel, B.; Beemster, G.T.S.; Ljung, K.; De Smet, I.; Van Isterdael, G.; Naudts, M.; Iida, R.; Gruissem, W.; Tasaka, M.; et al. Cell Cycle Progression in the Pericycle Is Not Sufficient for SOLITARY ROOT/IAA14-Mediated Lateral Root Initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3035–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakenfull, E.A.; Riou-Khamlichi, C.; Murray, J.A. Plant D-type cyclins and the control of G1 progression. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2002, 357, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudolf, V.; Vlieghe, K.; Beemster, G.T.; Magyar, Z.; Torres Acosta, J.A.; Maes, S.; Van Der Schueren, E.; Inzé, D.; De Veylder, L. The plant-specific cyclin-dependent kinase CDKB1;1 and transcription factor E2Fa-DPa control the balance of mitotically dividing and endoreduplicating cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2683–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G. [17] Binary ti vectors for plant transformation and promoter analysis. In Method Enzymol; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 153, pp. 292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Expósito-Rodríguez, M.; Borges, A.A.; Borges-Pérez, A.; Pérez, J.A. Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yan, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J. Simultaneous analysis of ten phytohormones in Sargassum horneri by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2016, 39, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floková, K.; Tarkowská, D.; Miersch, O.; Strnad, M.; Wasternack, C.; Novák, O. UHPLC-MS/MS based target profiling of stress-induced phytohormones. Phytochemistry 2014, 105, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Zong, Y.; Qian, M.; Yang, F.; Teng, Y. Simultaneous quantitative determination of major plant hormones in pear flowers and fruit by UPLC/ESI-MS/MS. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 1766–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Li, L.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tan, T.; Jia, Y.; Xie, Q.; Chen, G. Anthocyanin Accumulation and Transcriptional Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Purple Pepper. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12152–12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Thrimawithana, A.H.; Cooney, J.M.; Jensen, D.J.; Espley, R.V.; Allan, A.C. The proanthocyanin-related transcription factors MYBC1 and WRKY44 regulate branch points in the kiwifruit anthocyanin pathway. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kang, J.; Xie, Q.; Gong, J.; Shen, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G.; Hu, Z. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor bHLH95 affects fruit ripening and multiple metabolisms in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 6311–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, P.; Cheng, X.; Xing, C.; Gao, Z.; Xue, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z. Overexpression of SlMADS48 Alters the Structure of Inflorescence and the Sizes of Sepal and Fruit in Tomato. Plants 2025, 14, 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213259

Guo P, Cheng X, Xing C, Gao Z, Xue J, Zhang X, Chen G, Chen X, Hu Z. Overexpression of SlMADS48 Alters the Structure of Inflorescence and the Sizes of Sepal and Fruit in Tomato. Plants. 2025; 14(21):3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213259

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Pengyu, Xin Cheng, Chuanji Xing, Zihan Gao, Jing Xue, Xiuhai Zhang, Guoping Chen, Xuqing Chen, and Zongli Hu. 2025. "Overexpression of SlMADS48 Alters the Structure of Inflorescence and the Sizes of Sepal and Fruit in Tomato" Plants 14, no. 21: 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213259

APA StyleGuo, P., Cheng, X., Xing, C., Gao, Z., Xue, J., Zhang, X., Chen, G., Chen, X., & Hu, Z. (2025). Overexpression of SlMADS48 Alters the Structure of Inflorescence and the Sizes of Sepal and Fruit in Tomato. Plants, 14(21), 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213259