Dynamic Evaluation of Urban Park Service Performance from the Perspective of “Vitality-Demand-Supply”: A Case Study of 59 Parks in Gongshu District, Hangzhou

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Multi-Source Data and Processing

2.3. Dynamic Evaluation Model for the Vitality Performance of Urban Parks

2.3.1. Indicator Quantification

- Calculate the theoretical service area: Based on the “15-min walking accessibility” principle, starting from each park entrance, generate 15 min walking isochrones along the urban road network; the total buffer area is the theoretical maximum service range.

- Calculate the actual service area: Extract the 80th percentile of visitor commute distances from mobile phone signaling data as the service radius; the total buffer area calculated using this radius is the actual service area.

- The Effective Service Area Ratio (ESAR) is calculated as:

2.3.2. Weight Assignment

- Calculation of data-driven base weight: As described above in “Weight Assignment Based on Impact Factors”/“Objective Weighting Based on Entropy Method,” obtain the base weight Wbase.

- Setting of policy preference adjustment coefficient: Set the adjustment coefficient α. Under strong policy orientation, set ; under neutral policy, set ; under restrictive policy, set . This study’s weight assignment referenced the requirements for ensuring children’s activity spaces in the “Hangzhou Child-Friendly City Construction Plan” [53] and the emphasis on age-friendly construction, thus assigning a higher policy orientation ()to indicators like the Spatial Coupling Index for Vulnerable Groups.

- Calculation of hybrid weight: Combine the base weight with the policy coefficient to generate the hybrid weight. The sum of hybrid weights must not exceed the total dimension weight; if it does, scale proportionally. The calculation formulas are:

2.3.3. Performance Calculation

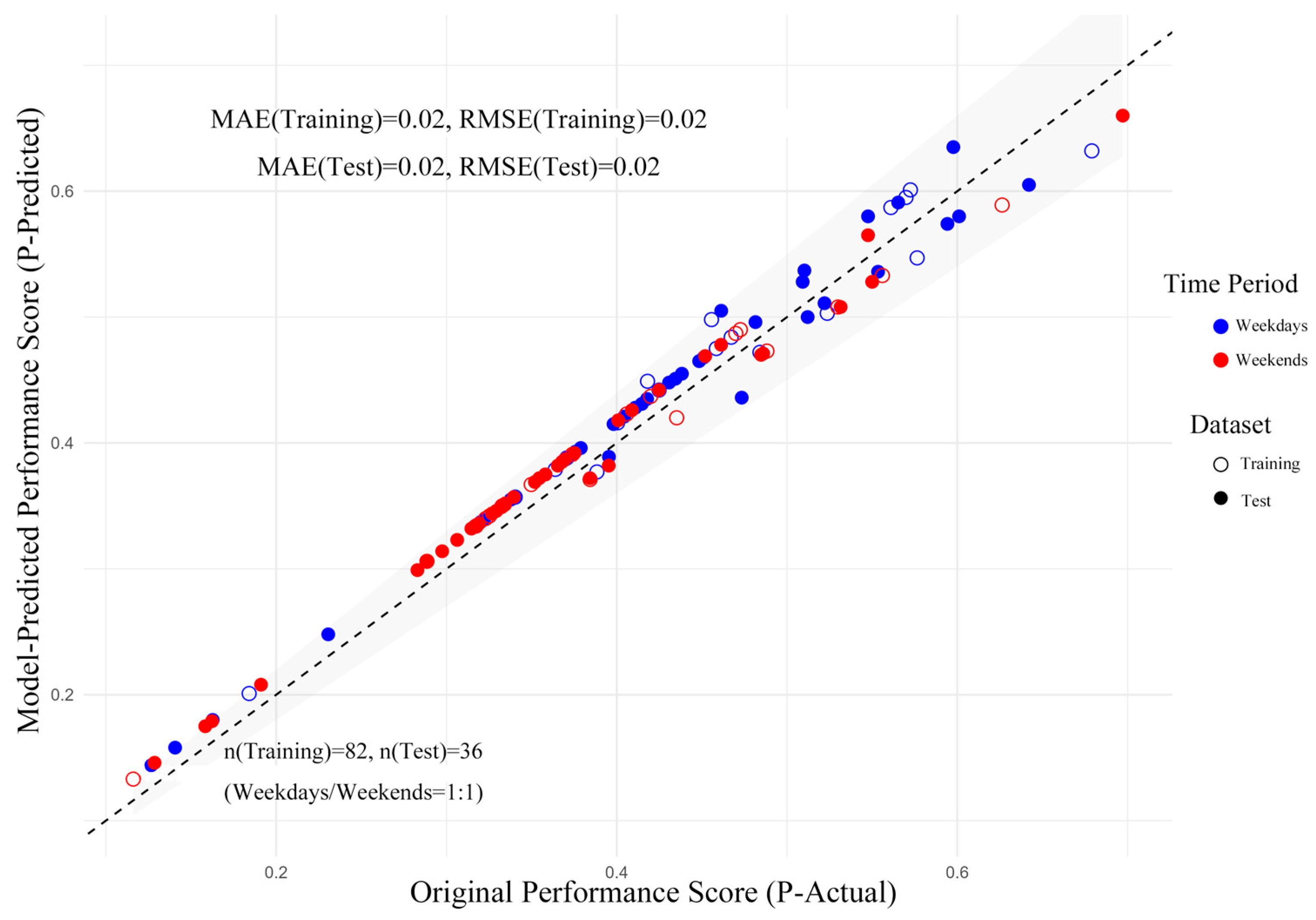

2.3.4. Model Validation and Robustness Testing

3. Results

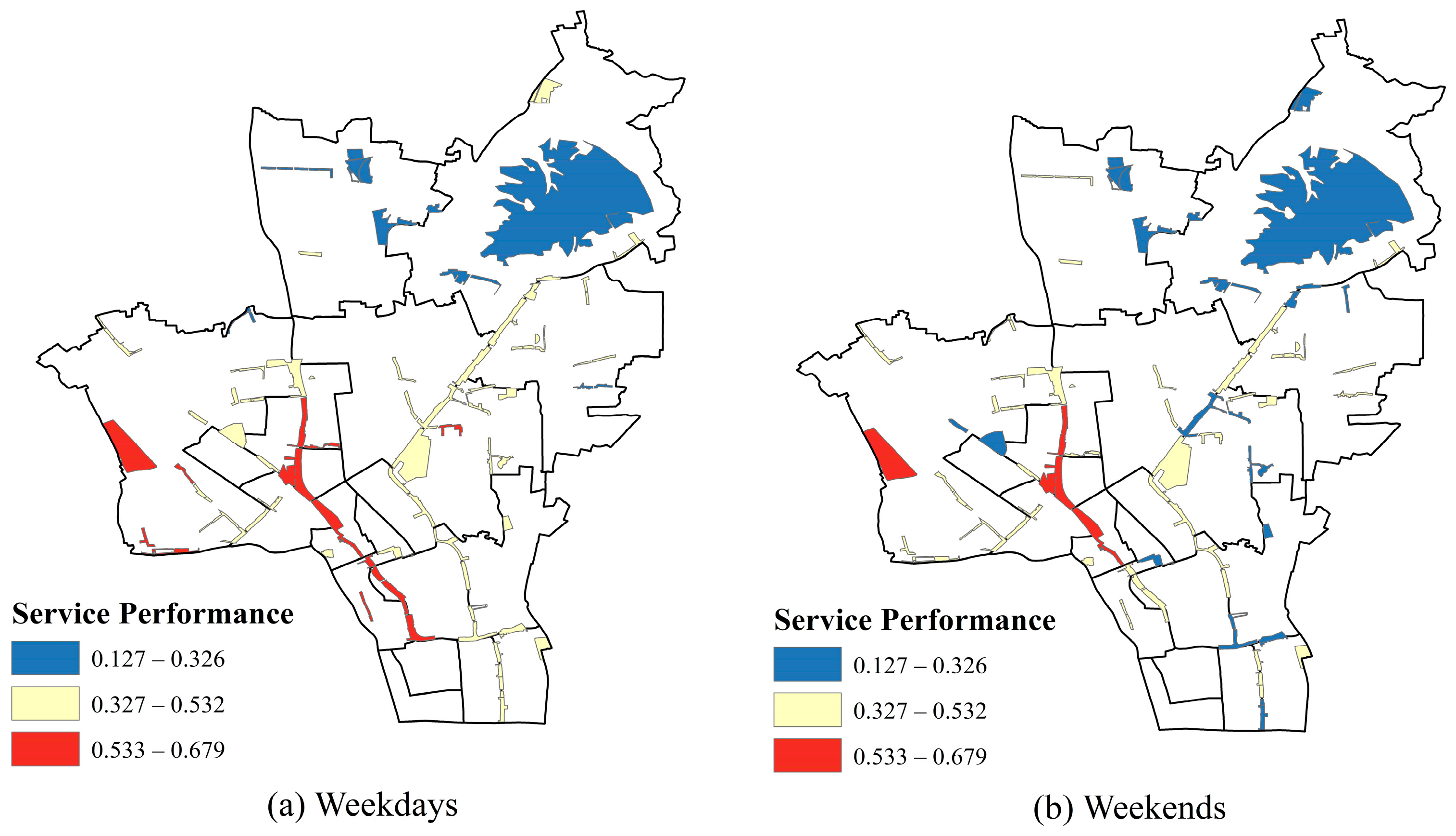

3.1. Performance Characteristics Across Dimensions

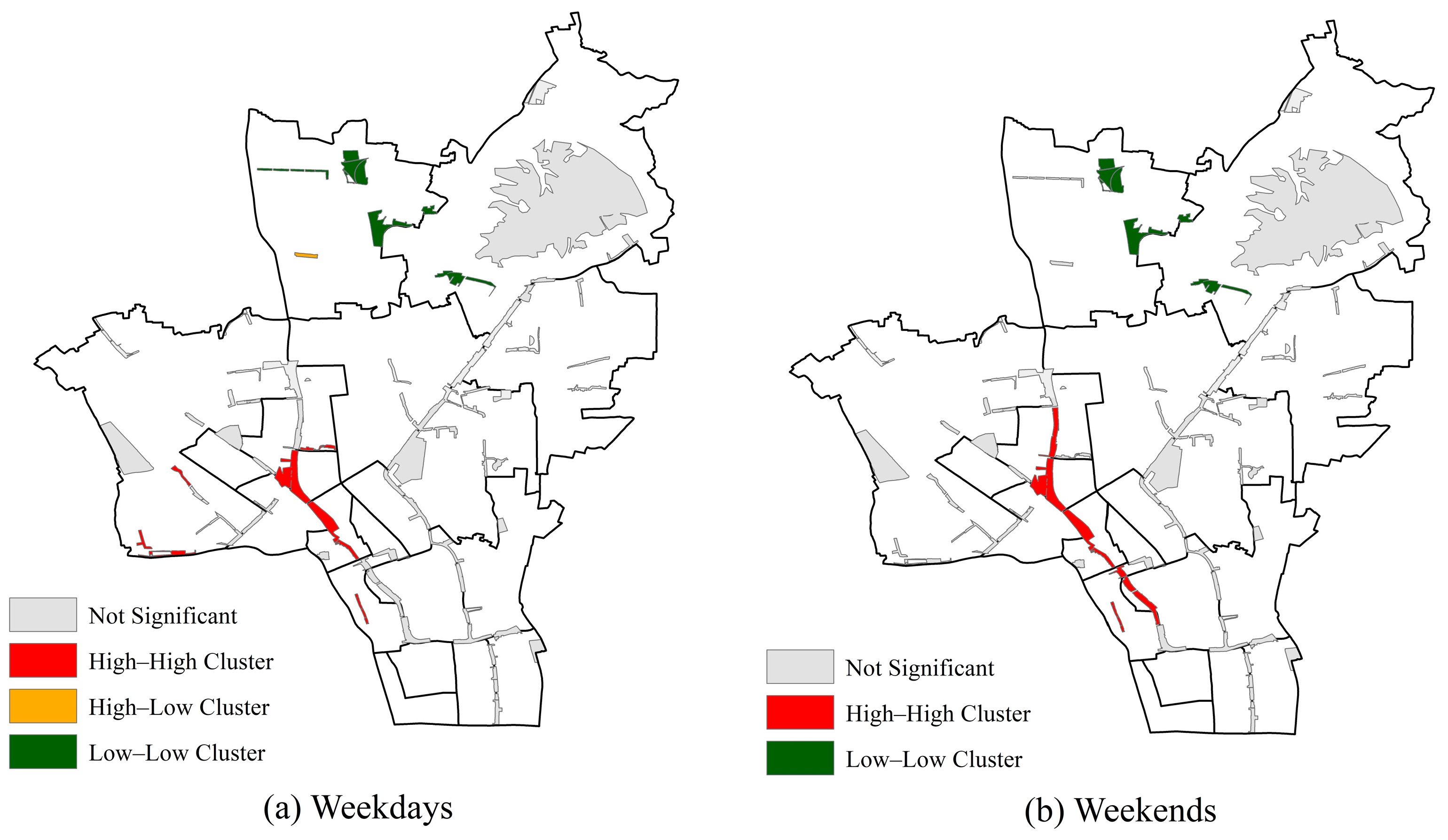

3.2. Spatiotemporal Differences in Comprehensive Performance

3.3. Model Robustness Verification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiesura, A. The Role of Urban Parks for the Sustainable City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsitano, E.; Rosa, A.G.; Posca, C.; Petruzzi, G.; Mundo, M.; Colao, M. A Sustainable Urban Regeneration Project to Protect Biodiversity. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, D. Accessibility to Greenspaces: GIS Based Indicators for Sustainable Planning in a Dense Urban Context. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 42, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; De Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and Mental Health: An Ecosystem Service Perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Research on Evaluating and Optimizing Landscape Vitality of Community Parks in Areas with Hot Summers and Cold Winters. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kuklina, V.; Sizov, O.; Fedorov, R. Green Spaces as an Indicator of Urban Sustainability in the Arctic Cities: Case of Nadym. Polar Sci. 2021, 29, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Greening Commission. National Territorial Spatial Planning Outline (2022–2030). Available online: https://www.forestry.gov.cn/c/www/lhxwdt/92479.jhtml (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. “14th Five-Year Plan” Rural Greening and Beautification Action Plan. Available online: https://www.forestry.gov.cn/c/www/lczc/27613.jhtml (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Beijing Municipal People’s Government. Beijing Urban Master Plan (2016–2035); Beijing Urban Planning and Land Resources Management Commission: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, E.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, J. Research on Accessibility of Open Spaces in Urban Areas at Home and Abroad: Theme Framework and Frontier Trends. World Reg. Stud. 2024, 33, 136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Dong, X.; Zhai, X.; Shen, J. Rethinking Cultural Ecosystem Services in Urban Forest Parks: An Analysis of Citizens’ Physical Activities Based on Social Media Data. Forests 2024, 15, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Ye, Q.; Dong, X. Using Importance–Performance Analysis to Reveal Priorities for Multifunctional Landscape Optimization in Urban Parks. Land 2024, 13, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wu, R.; Bao, Z.; Yan, H.; Nan, X.; Luo, Y.; Dai, T. Effects of Urban Park Environmental Factors on Landscape Preference Based on Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of Visitors. Forests 2023, 14, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.; Kellar, I.; Conner, M.; Gidlow, C.; Kelly, B.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; McEachan, R. Associations Between Park Features, Park Satisfaction and Park Use in a Multi-Ethnic Deprived Urban Area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 46, 126485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Zhu, J. Green space fair performance evaluation based on the theory of coupled coordinated development. Urban Plan. 2017, 41, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S. Evaluation and Optimization of Recreational Services in Park Green Spaces in Haidian District, Beijing. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. Research on the Performance Evaluation and Optimization Countermeasures of Recreational Services in Park Green Spaces in Xi’an City. Master’s Thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Banchiero, F.; Blecic, I.; Saiu, V.; Trunfio, G.A. Neighbourhood Park Vitality Potential: From Jane Jacobs’s Theory to Evaluation Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. Analysis of the Spatial Vitality of Urban Parks in Zhengzhou City. Master’s Thesis, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Research on the Attractiveness of Urban Parks Based on the Perceptions of Elderly People for Recreation. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Wu, X.; Cao, Y.; Pan, S.; Cai, G. Evaluation of Service Efficiency of Large Parks in Wuhan Based on Mobile Signal Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Urban Planning Annual Conference, Wuhan, China, 23 September 2023; pp. 986–997. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, F. Research on the Service Efficiency of Park Green Spaces in the Central Urban Area of Haikou Based on Accessibility. Master’s Thesis, Hainan Normal University, Haikou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Han, R.; Ma, J.; Li, X. Evaluation and Optimization of Recreational Service Capacity of Urban Mountain Parks Based on Mountainous Characteristics: A Case Study of Chengde City. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 36, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, S.; Gong, L.; Kang, C.; Zhi, Y.; Chi, G.; Shi, L. Social Sensing: A New Approach to Understanding Our Socioeconomic Environments. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2015, 105, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lu, H.; Zheng, T.; Rong, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.; Tang, L. Vitality of Urban Parks and Its Influencing Factors from the Perspective of Recreational Service Supply, Demand, and Spatial Links. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Zong, W.; Peng, K.; Zhang, R. Assessing Spatial Heterogeneity in Urban Park Vitality for a Sustainable Built Environment: A Case Study of Changsha. Land 2024, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Liu, C. Exploring Factors Affecting Urban Park Use from a Geospatial Perspective: A Big Data Study in Fuzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Lei, G.; Zhang, L. Quality Evaluation of Park Green Space Based on Multi-Source Spatial Data in Shenyang. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Yan, W. Exploring Spatial Distribution of Urban Park Service Areas in Shanghai Based on Travel Time Estimation: A Method Combining Multi-Source Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Gan, Q.; Ma, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Spatial Vitality Detection and Evaluation in Zhengzhou’s Main Urban Area. Buildings 2024, 14, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Chen, Y.; Thy, P.T.M.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. Identifying Urban Vitality in Metropolitan Areas of Developing Countries from a Comparative Perspective: Ho Chi Minh City Versus Shanghai. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, D.; Fang, J. Exploring the Disparities in Park Access Through Mobile Phone Data: Evidence from Shanghai, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, M.; Wu, S.; Li, B. Exploring the Disparities in Park Accessibility through Mobile Phone Data: Evidence from Fuzhou of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 281, 111849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Fan, H.; Wang, L.; Zhu, D.; Yang, M. Revealing Urban Vibrancy Stability Based on Human Activity Time-Series. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 85, 104053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Re-Examining Urban Vitality through Jane Jacobs’ Criteria Using GIS-sDNA: The Case of Qingdao, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, S. Death and Life of Great American Cities, the/J. Jacobs. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-118-56844-6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, G. The Development, Connotations, and Interests of Research on Landscape Performance Evaluation for Evidence-Based Design. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2020, 8, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zheng, Z. Urban Spatiotemporal Behavioral Landscape Based on Space-Time-Human Coupling: Theory and Application Research. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 2271–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhejiang Meteorological Bureau. Zhejiang Weather Network. Available online: http://zj.weather.com.cn/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- GB/T 35790-2023; Information Security Technology—Security Technical Specification for Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) Systems. State Administration for Market Regulation, National Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Lou, G.; Chen, Q.; Chen, W. Strategic Planning for Sustainable Urban Park Vitality: Spatiotemporal Typologies and Land Use Implications in Hangzhou’s Gongshu District via Multi-Source Big Data. Land 2025, 14, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Li, S.; Jiang, B.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Hu, Y.; Wen, T.; Feng, Y. Actual Supply-Demand of the Urban Green Space in a Populous and Highly Developed City: Evidence Based on Mobile Signal Data in Guangzhou. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 51346-2019; Standard for Planning of Urban Green Space. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Gehl, J.; Rogers, L.R. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-59726-573-7. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; University Translation Series; Shanghai Translation Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2016; ISBN 978-7-5327-7051-9. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Luo, X. Research on the Dynamic Spatial-Temporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Urban Waterfront Parks—Taking Kunming City as an Example. South. Archit. 2024, 8, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice, 5th–6th ed.; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-674-00077-3. (Revised 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. The Theoretical Basis of Public Service Supply: Systematization and Framework Construction. J. Sichuan Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 4, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Fei, Y. A Discussion on Evaluation Methods of Community Public Service Level from the Perspective of “Living Circle”. Intell. Build. Smart City 2021, 3, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; ISBN 978-1-933771-77-9. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 25, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A. Evaluation and Optimization of Recreational Service Performance in Urban Park Green Spaces: A Case Study of Jiulongpo District, Chongqing. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Decision of the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress of Hangzhou City on Strengthening the Construction of a Child-Friendly City. Available online: http://www.hzrd.gov.cn/art/2022/12/21/art_1229690484_18827.html (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-0-387-84857-0. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, S.; Yang, J.; Feng, Y.; Yan, S. Measuring the spatio-temporal vitality and influencing factors of urban parks based on multi-source data: A case study of Nanjing. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Research on Evaluation Method and Application of Urban Park Equity Performance from the Perspective of Spatial Justice. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| First Dimension | Secondary Indicator | Quantitative Method | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitality Level | Temporal Activity Difference (TAD) | The degree of difference in activity intensity between weekdays and weekends | Mobile phone data |

| Temporal Stability Index (TSI) | The ratio of the daily average activity value to the standard deviation of the daily activity value | Mobile phone data | |

| Spatiotemporal Synergy coefficient (STS) | Peak activity level and night-time activity decline rate | Mobile phone data | |

| Service Efficiency per Unit Area (SEUA) | Activity heat index/Green area (people/hectare/hour) | remote sensing image data | |

| Demand Matching | Effective Walking Coverage Rate (EWCR) | Population Percentage within 15 min Walkable Distance (%) | Mobile phone data |

| Vitality-Population Matching Index (VPMI) | Spatial coupling degree of resident population and activity intensity | Population | |

| Spatial Coupling Index for Vulnerable Groups (SCI) | Calculate the spatial coupling degree separately for the elderly and children. | Statistical yearbook, mobile phone data | |

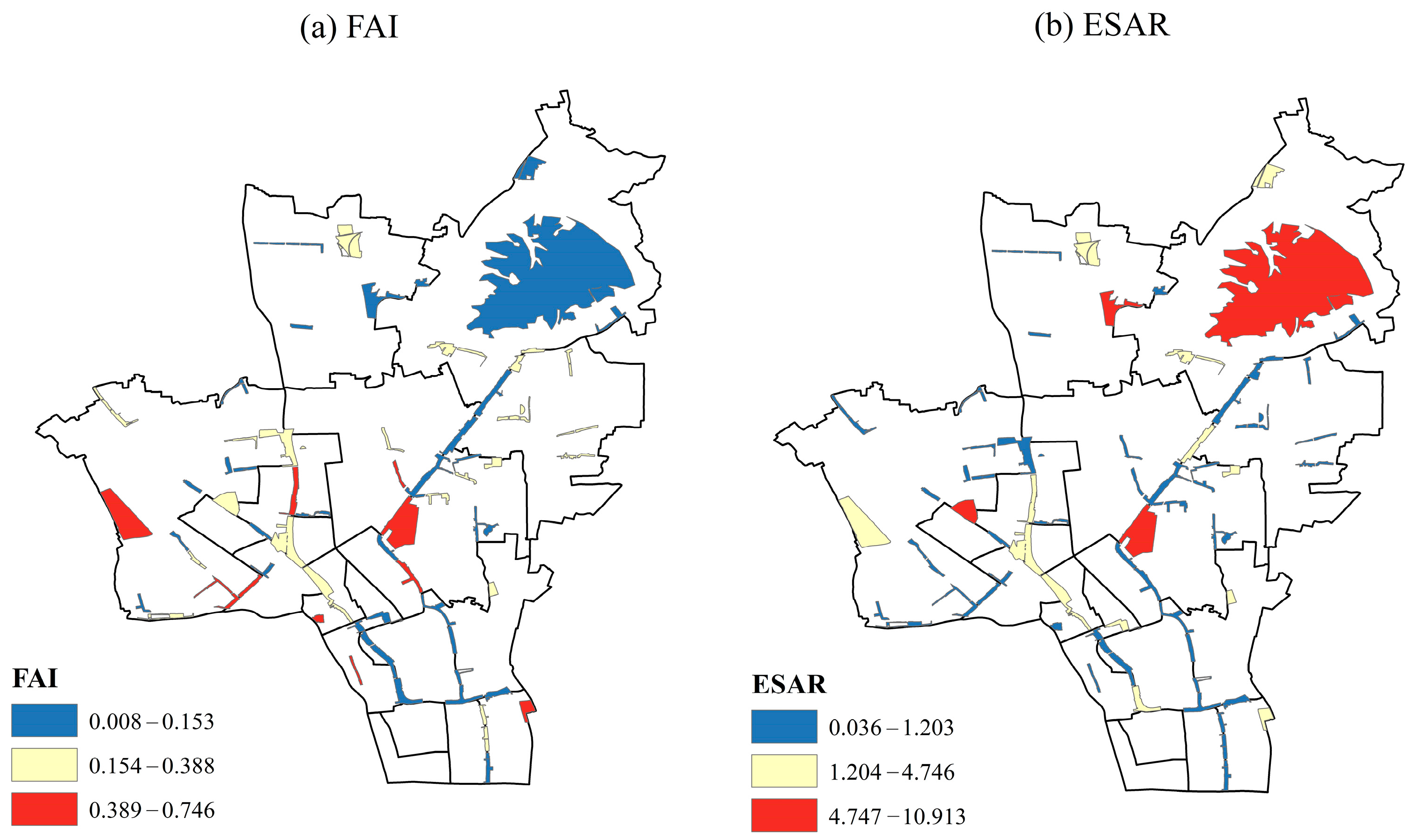

| Service Supply | Function Adaptation Index (FAI) | The ratio of POI to the number of residents | POI, population |

| Effective Service Area Ratio (ESAR) | The ratio of the actual service area to the theoretical service area | Mobile phone data |

| Statistical Item | Mean | Median | Max | Min | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pweekday | 0.412 | 0.405 | 0.679 | 0.127 | 0.138 |

| Pweekend | 0.375 | 0.368 | 0.697 | 0.128 | 0.142 |

| Time period differences (Pweekday − Pweekend) | +0.037 | +0.037 | −0.018 | −0.001 | Similar levels of dispersion |

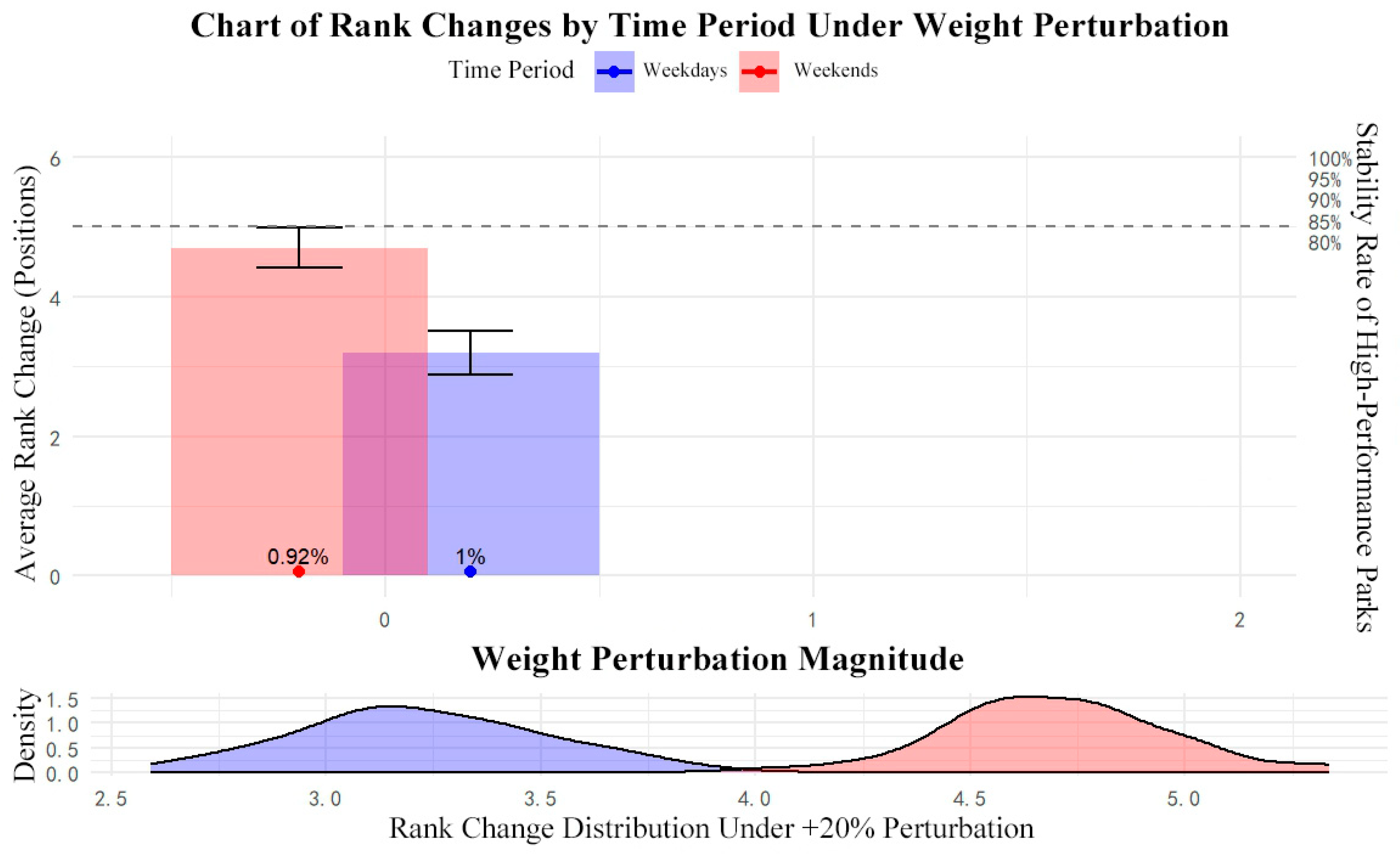

| Period | Performance Score Standard Deviation | Spearman Correlation Coefficient | Ranking Change Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | 0.032 | 0.92 *** | 3.8% |

| Weekend | 0.047 | 0.85 *** | 5.6% |

| Direction of Disturbance | Period | Average Ranking Change | The Proportion of Parks with 5 or More Changes | High-Performance Park Stability Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +20% weight perturbation | Weekday | 3.2 | 8.5% | 100% |

| −20% weight perturbation | Weekend | 4.7 | 12.2% | 92% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lou, G.; Qi, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Q. Dynamic Evaluation of Urban Park Service Performance from the Perspective of “Vitality-Demand-Supply”: A Case Study of 59 Parks in Gongshu District, Hangzhou. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2026, 15, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010021

Lou G, Qi Y, Chen X, Chen Q. Dynamic Evaluation of Urban Park Service Performance from the Perspective of “Vitality-Demand-Supply”: A Case Study of 59 Parks in Gongshu District, Hangzhou. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2026; 15(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleLou, Ge, Yiduo Qi, Xiuxiu Chen, and Qiuxiao Chen. 2026. "Dynamic Evaluation of Urban Park Service Performance from the Perspective of “Vitality-Demand-Supply”: A Case Study of 59 Parks in Gongshu District, Hangzhou" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 15, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010021

APA StyleLou, G., Qi, Y., Chen, X., & Chen, Q. (2026). Dynamic Evaluation of Urban Park Service Performance from the Perspective of “Vitality-Demand-Supply”: A Case Study of 59 Parks in Gongshu District, Hangzhou. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 15(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010021