Comparative Assessment of Quantitative Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Feature Selection Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Software Employed

2.3. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping (LSM)

2.3.1. Landslide Causative Factor Classification and Normalization

2.3.2. Feature Selection Techniques

2.3.3. Model Selection

2.3.4. Model Evaluation

3. Results

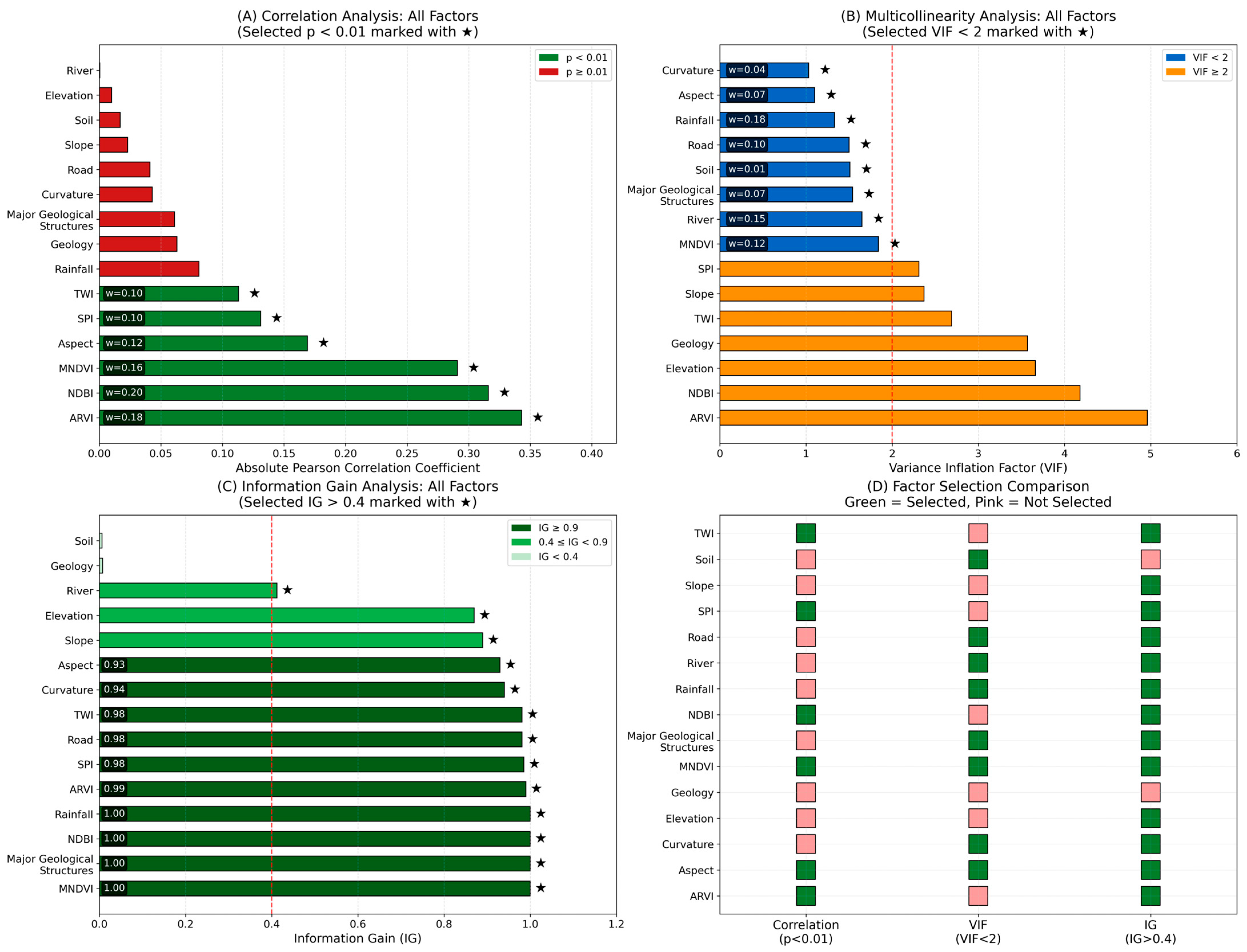

3.1. Feature (Landslide Causative Factor) Selection

3.1.1. Case 1: Correlation Analysis

3.1.2. Case 2: Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) Analysis

3.1.3. Case 3: Information Gain (IG) Analysis

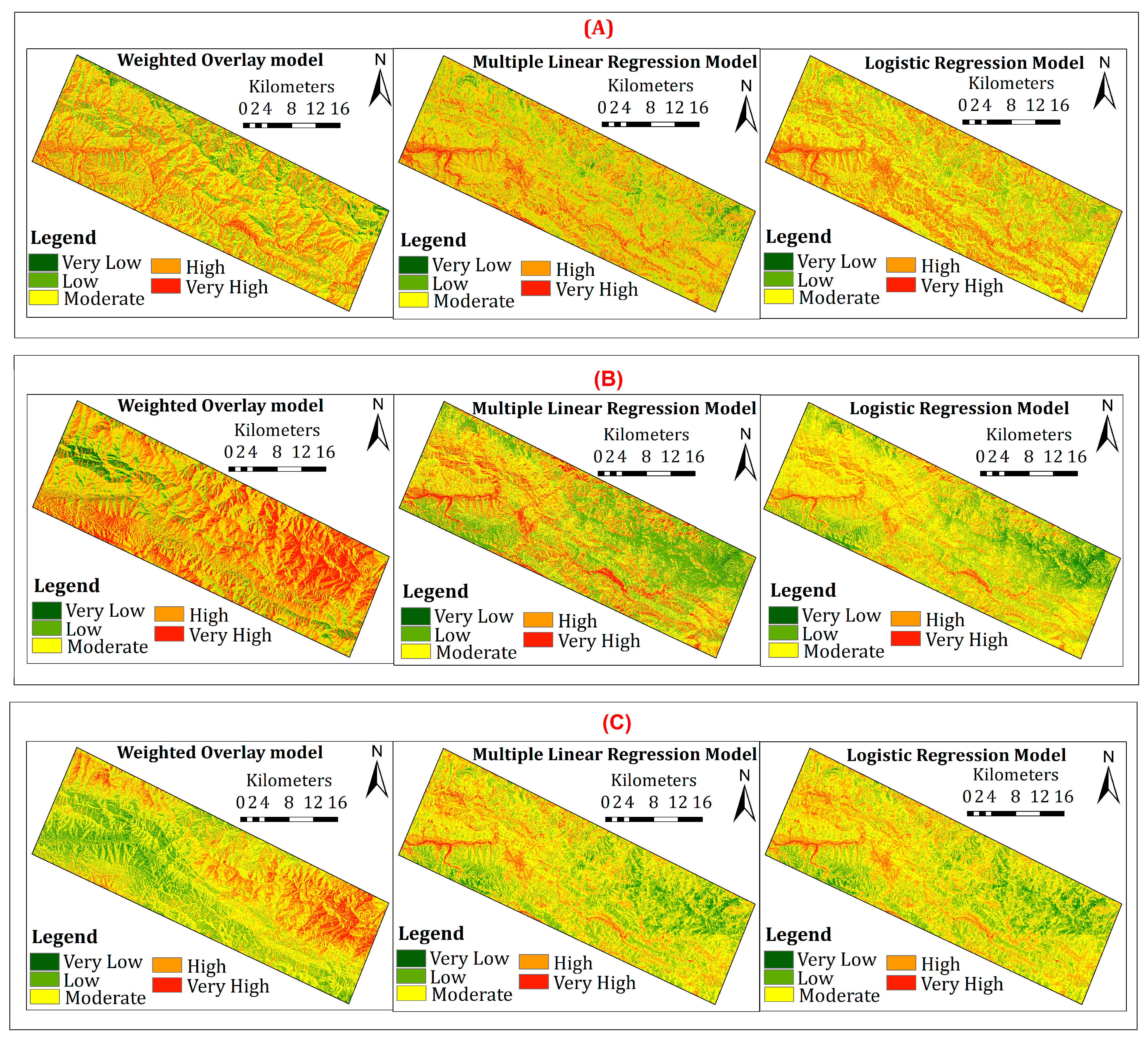

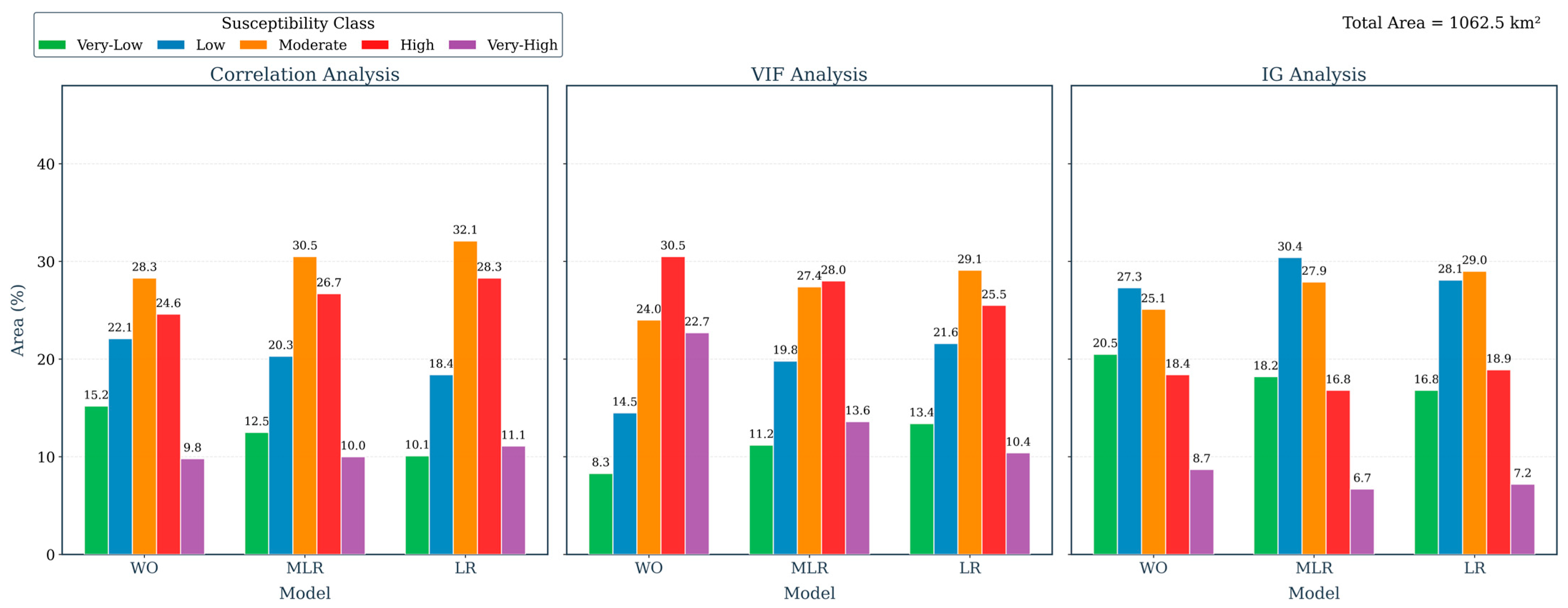

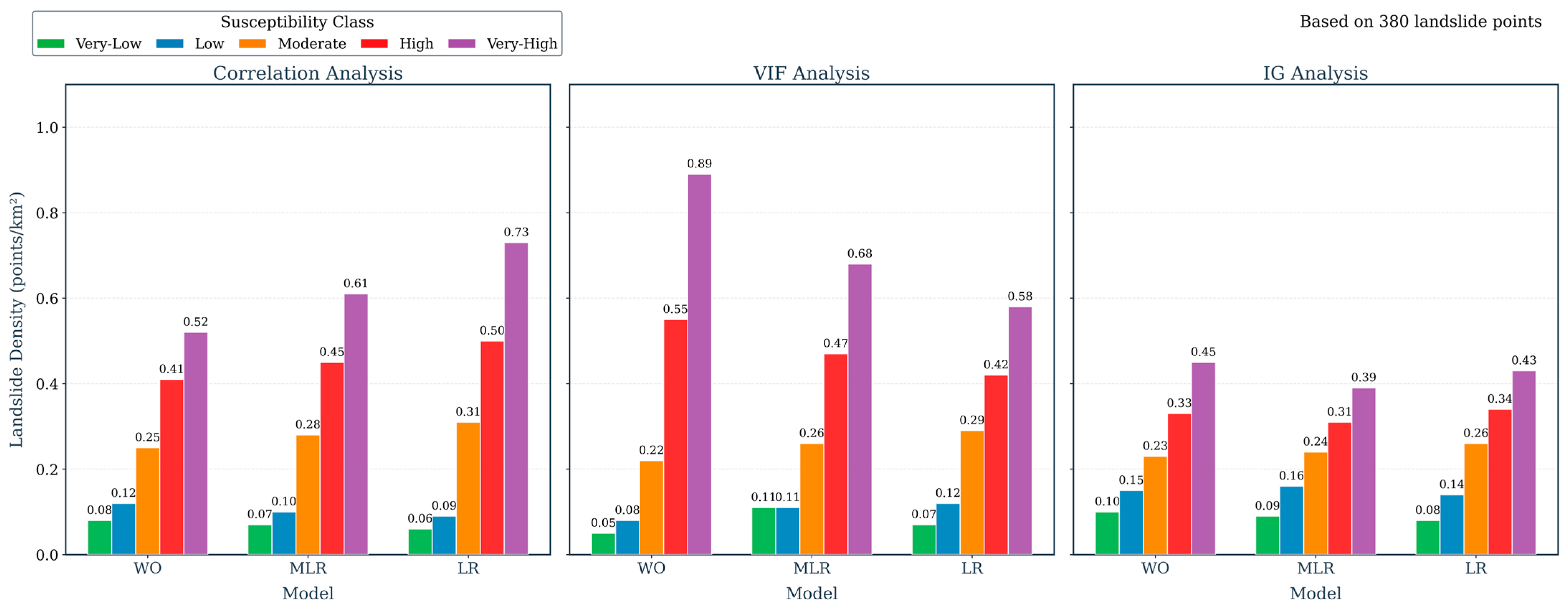

3.2. Landslide Susceptibility Maps (LSMs)

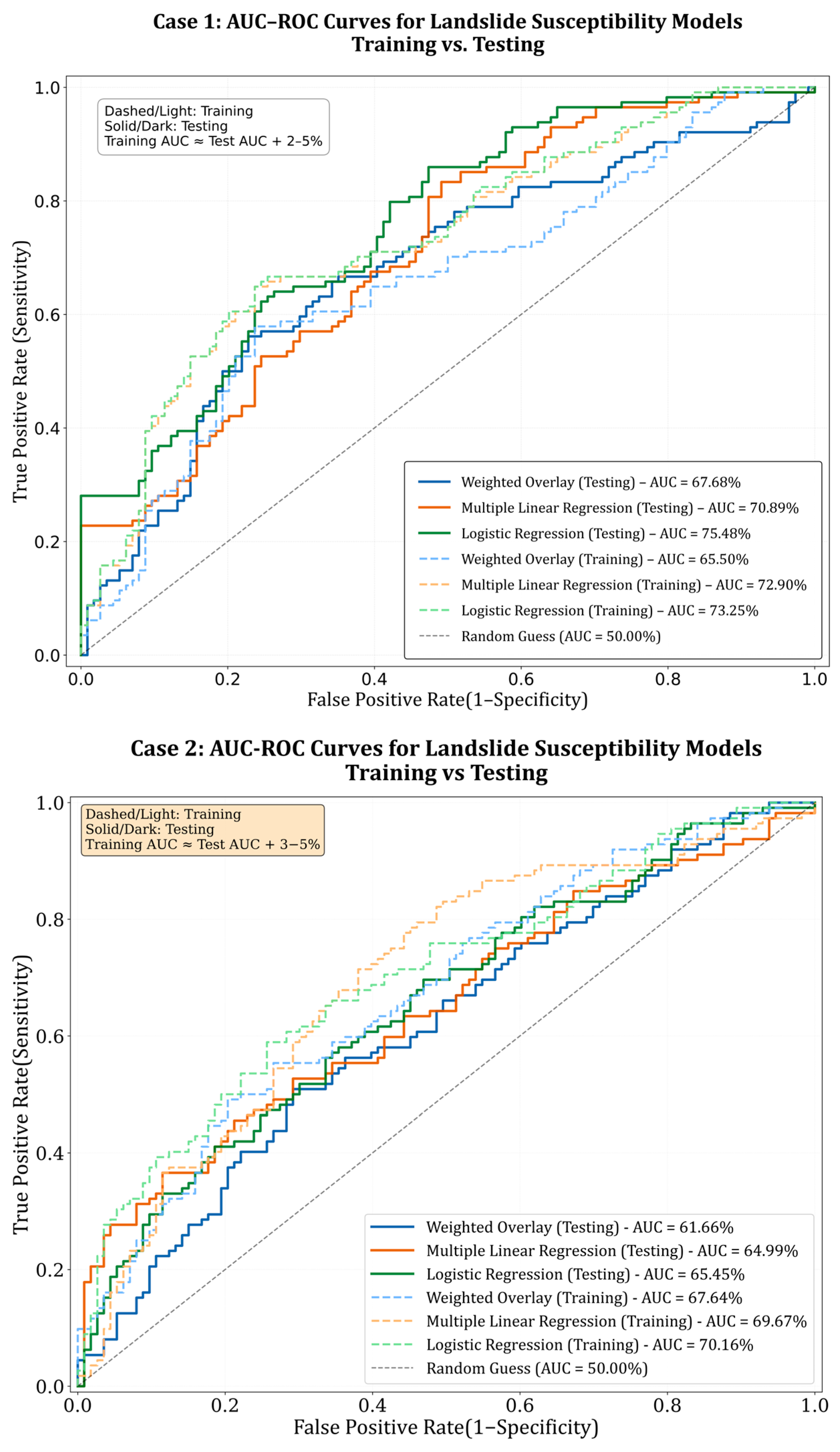

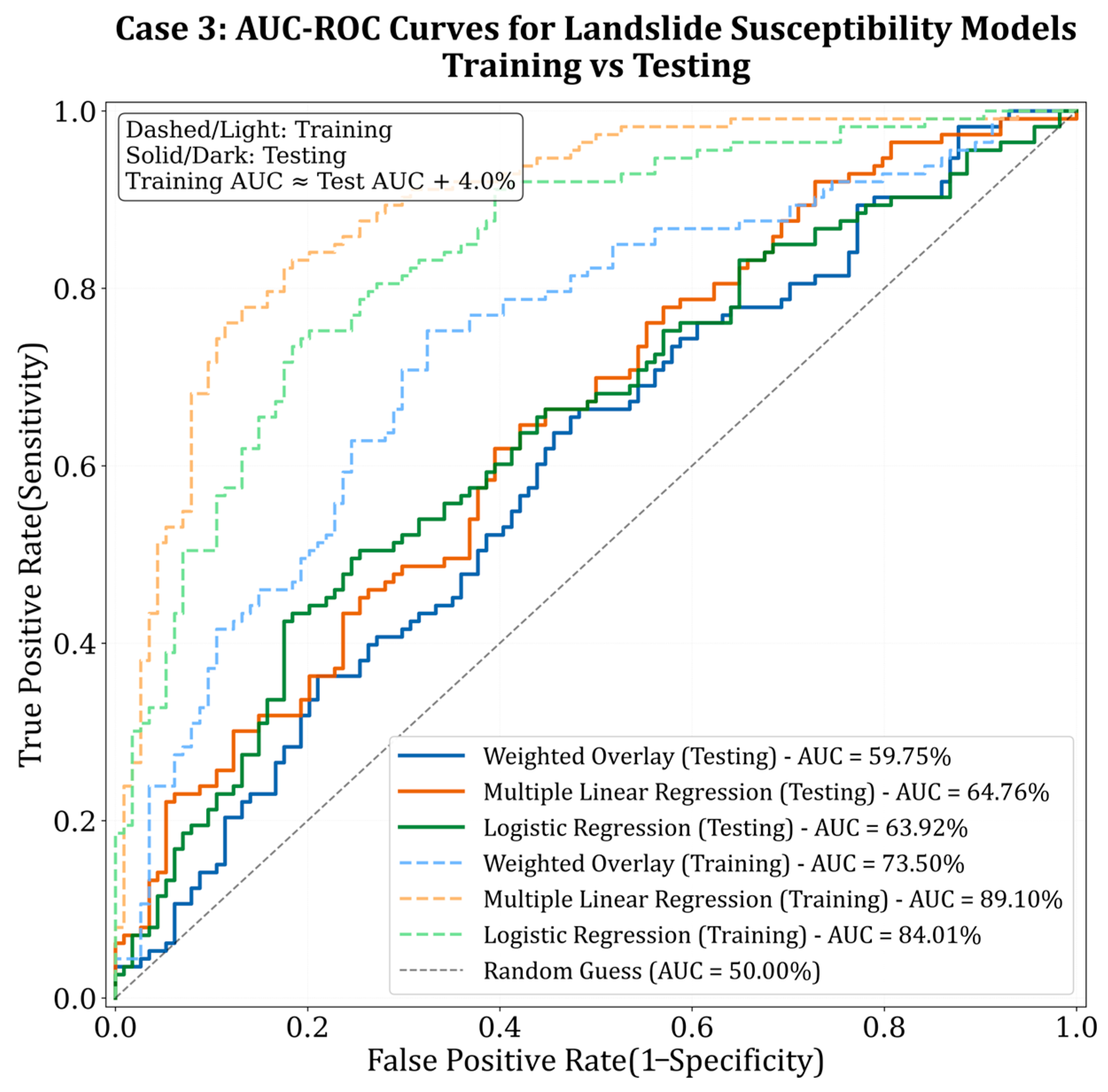

3.3. Accuracy Assessment

3.4. Validation Robustness

4. Discussion

5. Limitations/Challenges

5.1. Limitations Related to Input Data Accuracy and Resolution

5.2. Temporal Consistency Between Inventory and Environmental Data

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niraj, K.C.; Singh, A.; Shukla, D.P. Effect of the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) on GIS-enabled bivariate and multivariate statistical models for landslide susceptibility mapping. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2023, 51, 1739–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, U.; Blum, P.; da Silva, P.F.; Andersen, P.; Pilz, J.; Chalov, S.R.; Malet, J.-P.; Auflič, M.J.; Andres, N.; Poyiadji, E.; et al. Fatal landslides in Europe. Landslides 2016, 13, 1545–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicísimo, Á.M.; Cuartero, A.; Remondo, J.; Quirós, E. Mapping landslide susceptibility with logistic regression, multiple adaptive regression splines, classification and regression trees, and maximum entropy methods: A comparative study. Landslides 2013, 10, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Niu, R.; Jia, X. A comparison of information value and logistic regression models in landslide susceptibility mapping by using GIS. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chhetri, N.K.; Dhiman, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Shukla, D.P. Strategies for sampling pseudo-absences of landslide locations for landslide susceptibility mapping in complex mountainous terrain of Northwest Himalaya. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraj, K.C.; Singh, A.; Shukla, D.P. Improved Landslide Susceptibility mapping using statistical MLR model. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Machine Intelligence for GeoAnalytics and Remote Sensing (MIGARS), Hyderabad, India, 27–29 January 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Ye, Z.; Jiang, S.-H.; Huang, J.; Chang, Z.; Chen, J. Uncertainty study of landslide susceptibility prediction considering the different attribute interval numbers of environmental factors and different data-based models. Catena 2021, 202, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, A. Spatial prediction models for landslide hazards: Review, comparison, and evaluation. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2005, 5, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Shukla, D.P. Effect of scale and mapping unit on landslide susceptibility mapping of Mandakini River Basin, Uttarakhand, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Dhiman, N.; KC, N.; Shukla, D.P. Improving ML-based landslide susceptibility using ensemble method for sample selection: A case study of Kangra district in Himachal Pradesh, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ji, F.; Gao, Y.; Liang, P. Slope Stability Analysis Using a Surrogate Model with Varying Sampling Precision: A Case Study of Open-Pit Mine Dump Slopes. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 10963–10988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmoon, B.; Biniyaz, A.; Liu, Z. Use of High-Resolution Multi-Temporal DEM Data for Landslide Detection. Geosciences 2022, 12, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lari, S.; Frattini, P.; Crosta, G.B. A Probabilistic Approach for Landslide Hazard Analysis. Eng. Geol. 2014, 182, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvioli, M.; Marchesini, I.; Reichenbach, P.; Rossi, M.; Ardizzone, F.; Fiorucci, F.; Guzzetti, F. Automatic delineation of geomorphological slope units with r.slopeunits v1.0 and their optimization for landslide susceptibility modeling. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 3975–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, P.; Rossi, M.; Malamud, B.D.; Mihir, M.; Guzzetti, F. A review of statistically based landslide susceptibility models. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 180, 60–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudasaini, S.P.; Mergili, M. A multi-phase mass flow model. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2019, 124, 2920–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Peng, J.; Hong, H.; Shahabi, H.; Pradhan, B.; Liu, J.; Zhu, A.-X.; Pei, X.; Duan, Z. Landslide susceptibility modelling using GIS-based machine learning techniques for Chongren County, Jiangxi Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chong, J.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z. Application of information gain in the selection of factors for regional slope stability evaluation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chang, J.M. Landslide dam formation susceptibility analysis based on geomorphic features. Landslides 2016, 13, 1019–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, M.; Ghasemian, B.; Shirzadi, A.; Bui, D.T. A comparative study of support vector machine and logistic model tree classifiers for shallow landslide susceptibility modeling. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.L.; Zhang, Y.S.; Iqbal, J.; Yang, Z.H.; Yao, X. Landslide susceptibility mapping using an integrated model of information value method and logistic regression in the Bailongjiang watershed, Gansu Province, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, L. Landslide susceptibility mapping using an integration of different statistical models for the 2015 Nepal earthquake in Tibet. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2024, 15, 2396908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.; Razavi, S.; Bilish, S. Review of hydrological modelling in the Australian Alps: From rainfall-runoff to physically based models. Australas. J. Water Resour. 2024, 28, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucklick, J.-P.; Müller, O. Tackling the Accuracy-Interpretability Trade-Off: Interpretable Deep Learning Models for Satellite Image-Based Real Estate Appraisal. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2023, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Walton, G.; Santi, P.; Luza, C. An ensemble approach of feature selection and machine learning models for regional landslide susceptibility mapping in the arid mountainous terrain of Southern Peru. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizábal-Giraldo, E.V.; Vélez-Upegui, J.I.; Martínez-Carvajal, H.E. A Comparison of Linear and Nonlinear Model Perfor-mance of SHIA_Landslide: A Forecasting Model for Rainfall-Induced Landslides. Rev. Fac. Ing. Univ. Antioq. 2016, 80, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, R.B.; Paudyal, K.R. Geological control of mineral deposits in Nepal. J. Nepal Geol. Soc. 2019, 58, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesner, M.; Bollinger, L.; Rizza, M.; Klinger, Y.; Karakaş, Ç.; Sapkota, S.N.; Shah, C.; Guérin, C.; Tapponnier, P. Surface rupture and landscape response in the middle of the great Mw 8.3 1934 earthquake mesoseismal area: Khutti Khola site. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia Contributors. Sindhuli District. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Available online: https://en.wikipe-dia.org/wiki/Sindhuli_District (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanre, D. Atmospherically resistant vegetation index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Sun, W.; Li, S.W.; Shen, Z.X.; Fu, G. Interannual variation of the growing season maximum normalized difference vegetation index, MNDVI, and its relationship with climatic factors on the Tibetan Plateau. Pol. J. Ecol. 2015, 63, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Govil, H.; Dey, A.; Gill, N. Analytical study of land surface temperature with NDVI and NDBI using Landsat 8 OLI and TIRS data in Florence and Naples city, Italy. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2018, 51, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.; et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—A new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 150066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The Soil and Terrain Database for Nepal (SOTER) (1:1,000,000 Scale) [Data Set]. 1995. Available online: http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/soil-survey/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Department of Mines and Geology. General Geology (Government of Nepal). 2023. Available online: https://dmgnepal.gov.np/en/pages/general-geology-4128. (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. OpenStreetMap [Data set]. 2020. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Jones, K.H. A comparison of algorithms used to compute hill slope as a property of the DEM. Comput. Geosci. 1998, 24, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, C. The modified normalized difference vegetation index (MNDVI) a new index to determine frost damages in agriculture based on Landsat TM data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1997, 18, 3583–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, T.; Huete, A.R.; Yoshioka, H.; Holben, B.N. An error and sensitivity analysis of atmospheric resistant vegetation indices derived from dark target-based atmospheric correction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 78, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Gao, J.; Ni, S. Use of normalized difference built-up index in automatically mapping urban areas from TM imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Pearson’s correlation coefficient. BMJ 2012, 345, e4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puth, M.T.; Neuhäuser, M.; Ruxton, G.D. Effective use of Spearman’s and Kendall’s correlation coefficients for association between two measured traits. Anim. Behav. 2015, 102, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.D. Point biserial correlation coefficient and its generalization. Psychometrika 1960, 25, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliev, M.; Mergili, M.; Mondal, I.; Nurtaev, B.; Pulatov, A.; Hübl, J. Comparative analysis of statistical methods for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Bostanlik District, Uzbekistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, M.; Rezaie, F.; Khosravi, K.; Kalantari, Z.; Bateni, S.M.; Lee, J.A. Beyond boundaries: AI-optimized global landslide susceptibility mapping. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2025, 16, 2493222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awawdeh, M.M.; ElMughrabi, M.A.; Atallah, M.Y. Landslide susceptibility mapping using GIS and weighted overlay method: A case study from North Jordan. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-López, E.; Fernández Del Castillo, T.; Sellers, C.; Delgado-García, J. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping of Landslides with Artificial Neural Networks: Multi-Approach Analysis of Backpropagation Algorithm Applying the Neuralnet Package in Cuenca, Ecuador. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costache, R.; Ali, S.A.; Parvin, F.; Pham, Q.B.; Arabameri, A.; Nguyen, H.; Crăciun, A.; Anh, D.T. Detection of areas prone to flood-induced landslides risk using certainty factor and its hybridization with FAHP, XGBoost and deep learning neural net-work. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 7303–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.H.; Basharat, M.; Riaz, M.T.; Riaz, M.T.; Wani, S.; Al-Ansari, N.; Le, L.B.; Linh, N.T.T. Spatiotemporal landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning models: A case study from district Hattian Bala, NW Himalaya, Pakistan. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G. Invariance Properties and Evaluation Metrics Derived from the Confusion Matrix in Multiclass Classification. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, F.S.; Calvello, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lacasse, S. Machine learning and landslide studies: Recent advances and applications. Nat. Hazards 2022, 114, 1197–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmaro, P.; Ausilio, E. Numerical evaluation of natural periods and mode shapes of earth dams for probabilistic seismic hazard analysis applications. Geosciences 2020, 10, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.M.; Bishop, T.F.; Wilford, J.R. Lithology and soil relationships for soil modelling and mapping. Catena 2016, 147, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Westen, C.J. The modelling of landslide hazards using GIS. Surv. Geophys. 2000, 21, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnes, D.J. Landslide Hazard Zonation: A Review of Principles and Practice (No. 3). 1984. Available online: http://worldcat.org/isbn/9231018957 (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Tien Bui, D.; Tuan, T.A.; Klempe, H.; Pradhan, B.; Revhaug, I. Spatial prediction models for shallow landslide hazards: A comparative assessment of the efficacy of support vector machines, artificial neural networks, kernel logistic regression, and logistic model tree. Landslides 2016, 13, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondini, A.C.; Guzzetti, F.; Melillo, M. Deep learning forecast of rainfall-induced shallow landslides. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, T.A.; Bhandari, B.P. Application of the bivariate frequency ratio method for landslide susceptibility mapping of Manthali Municipality, Ramechhap District, Nepal. Nepal J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lara Maia, A.C.; Ayres, A.L.d.S.M.; Kanai, C.S.; da Silva Ferreira, J.; Fontes, M.R.; Desani, N.M.; Guimarães, Y.C.; de Praga Baião, C.F.; Mantovani, J.R.; Nery, T.D.; et al. Scale-Dependent Controls on Landslide Susceptibility in Angra dos Reis (Brazil) Revealed by Spatial Regression and Autocorrelation Analyses. Geomatics 2025, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamud, B.D.; Turcotte, D.L.; Guzzetti, F.; Reichenbach, P. Landslide inventories and their statistical properties. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2004, 29, 687–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.C.; Lee, C.F.; Wang, S.J. Characterization of rainfall-induced landslides. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 4817–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shirzadi, A.; Shahabi, H.; Ahmad, B.B.; Zhang, S.; Hong, H.; Zhang, N. A novel hybrid artificial intelligence approach based on the rotation forest ensemble and naïve Bayes tree classifiers for a landslide susceptibility assessment in Langao County, China. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2017, 8, 1955–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, A. Spatial cross-validation and bootstrap for the assessment of prediction rules in remote sensing: The R package sperrorest. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Munich, Germany, 22–27 July 2012; pp. 5372–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Wu, H.; Oguchi, T.; Tang, Y.; Pei, X.; Wu, Y. Physically Based and Data-Driven Models for Landslide Susceptibility Assessment: Principles, Applications, and Challenges. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ji, J.; Hürlimann, M.; Medina, V. Probabilistic and physically-based modelling of rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility using integrated GIS-FORM algorithm. Landslides 2024, 21, 1461–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondo, J.; González-Díez, A.; De Terán, J.R.D.; Cendrero, A. Landslide susceptibility models utilising spatial data analysis techniques. A case study from the lower Deba Valley, Guipúzcoa (Spain). Nat. Hazards 2003, 30, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J.; Woo, I. The effect of spatial resolution on the accuracy of landslide susceptibility mapping: A case study in Boun, Korea. Geosci. J. 2004, 8, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, J.B.; Mirus, B.B. Overcoming the data limitations in landslide susceptibility modeling. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petley, D. Global patterns of loss of life from landslides. Geology 2012, 40, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Chun, K.W.; Kim, M.; Catani, F.; Choi, B.; Seo, J.I. Effect of antecedent rainfall conditions and their variations on shallow landslide-triggering rainfall thresholds in South Korea. Landslides 2021, 18, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, D.; Stanley, T.; Zhou, Y. Spatial and temporal analysis of a global landslide catalog. Geomorphology 2015, 249, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Causative Factors | Unit | Range/Classes | Description | Selection Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | meters (m) | 1910 to 2280 | Height above sea level influencing slope stability | Core Geomorphic |

| Slope | degrees (°) | 0 to 61.78 | Steepness of terrain affecting landslide probability | Core Geomorphic [37] |

| Aspect | degrees (°) | −1 to 359.79 | Direction of slope face affecting soil moisture & erosion | Core Geomorphic |

| Curvature | – | −3.61 (concave) to 2.83 (convex) | Terrain curvature influencing water flow convergence/divergence | Core Geomorphic |

| TWI | – | 2.69 to 23.01 | Predicts soil moisture accumulation based on slope and upslope area | Mechanistic (Hydrologic) [38] |

| SPI | – | −13.82 to 12.15 | Estimates erosive power of streams based on slope and flow accumulation | Mechanistic (Hydrologic) |

| Distance to River | meters (m) | 0 to 1623.61 | Proximity to rivers affecting erosion and saturation | Regional Diagnostic [21] |

| Geology | – | Bh, OGR, Na, Qs, Si | Rock types and their susceptibility to weathering/erosion | Regional Diagnostic [27,28] |

| Soil Types | – | PHh, RGd, CMe, CMg | Soil properties influencing water retention and slope stability | Data-Constrained |

| Distance to Road | meters (m) | 0 to 13,606.1 | Human-induced destabilization due to construction | Anthropogenic Proxy [21,29] |

| NDBI | – | −0.53 to 0.29 | Indicates urbanization impact on land stability | Anthropogenic Proxy |

| Rainfall | millimeters (mm) | 1223.05 to 1575.3 | Precipitation intensity affecting soil saturation | Mechanistic (Trigger) |

| MNDVI | – | −0.066 to 0.92 | Vegetation cover density influencing slope reinforcement | Core Geomorphic |

| ARVI | – | −0.07 to 0.92 | Vegetation measure adjusted for atmospheric effects | Core Geomorphic |

| Distance to Major Geological Structures | meters (m) | 0 to 12,063.7 | Proximity to mapped faults and thrusts, representing zones of structural weakness, groundwater movement, and reduced shear strength | Regional Diagnostic |

| Proximity Zone (Meters) | Distance to Roads | Distance to Rivers |

|---|---|---|

| 0–500 | 1668 (78% of total) | 1604 (75% of total) |

| 500–1000 | 257 (12% of total) | 321 (15% of total) |

| 1000–2000 | 139 (7% of total) | 214 (10% of total) |

| 2000–5000 | 75 (3% of total) | 0 (0% of total) |

| >5000 | 0 (0% of total) | 0 (0% of total) |

| Total Landslides | 2139 (100%) | 2139 (100%) |

| Model | AUC-ROC (%) | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score | Prediction Range | Mean Prediction Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1: Correlation Analysis | |||||||

| WO | 67.68 | 66.67 | 71.11 | 56.14 | 0.6275 | 0.18–0.82 | 0.48 |

| MLR | 70.89 | 67.11 | 62.91 | 83.33 | 0.717 | 0.25–0.90 | 0.62 |

| LR | 75.48 | 69.3 | 64.47 | 85.96 | 0.7368 | 0.06–1.00 | 0.67 |

| Case 2: VIF analysis | |||||||

| WO | 61.66 | 63.56 | 58.72 | 90.18 | 0.7113 | 0.22–0.60 | 0.4 |

| MLR | 64.99 | 64.00 | 60.40 | 80.36 | 0.6897 | 0.30–0.78 | 0.53 |

| LR | 65.45 | 64.00 | 63.48 | 65.18 | 0.6432 | 0.28–0.85 | 0.55 |

| Case 3: IG analysis | |||||||

| WO | 59.75 | 57.71 | 66.04 | 53.97 | 0.5217 | 0.15–0.70 | 0.38 |

| MLR | 64.76 | 62.11 | 60.15 | 70.7 | 0.6504 | 0.21–0.84 | 0.5 |

| LR | 63.92 | 64.76 | 67.01 | 57.52 | 0.619 | 0.20–0.80 | 0.49 |

| Method | Model | AUC-ROC (%) | Accuracy (%) | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Analysis (top 6) | WO | 67.68 | 66.67 | 0.63 |

| MLR | 70.89 | 67.11 | 0.72 | |

| LR | 75.48 | 69.3 | 0.74 | |

| VIF Analysis (top 6) | WO | 60.88 | 62.34 | 0.7 |

| MLR | 64.21 | 63.45 | 0.68 | |

| LR | 64.87 | 63.12 | 0.64 | |

| IG Analysis (top 6) | WO | 59.32 | 56.78 | 0.52 |

| MLR | 63.45 | 61.23 | 0.65 | |

| LR | 62.89 | 63.45 | 0.61 |

| Model + Feature Selection | Mean AUC (±Std) | Mean Accuracy (±Std) | Mean F1-Score (±Std) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LR + Correlation | 0.745 (±0.018) | 0.688 (±0.015) | 0.728 (±0.012) |

| WO + VIF | 0.608 (±0.022) | 0.621 (±0.019) | 0.705 (±0.017) |

| MLR + IG | 0.638 (±0.016) | 0.615 (±0.014) | 0.642 (±0.011) |

| LR + IG | 0.630 (±0.020) | 0.628 (±0.018) | 0.612 (±0.015) |

| WO + Correlation | 0.665 (±0.017) | 0.658 (±0.015) | 0.620 (±0.013) |

| MLR + VIF | 0.640 (±0.019) | 0.625 (±0.016) | 0.682 (±0.014) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Joshi, B.R.; Bhandary, N.P.; Acharya, I.P.; K.C., N. Comparative Assessment of Quantitative Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Feature Selection Techniques. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2026, 15, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010020

Joshi BR, Bhandary NP, Acharya IP, K.C. N. Comparative Assessment of Quantitative Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Feature Selection Techniques. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2026; 15(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoshi, Buddhi Raj, Netra Prakash Bhandary, Indra Prasad Acharya, and Niraj K.C. 2026. "Comparative Assessment of Quantitative Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Feature Selection Techniques" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 15, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010020

APA StyleJoshi, B. R., Bhandary, N. P., Acharya, I. P., & K.C., N. (2026). Comparative Assessment of Quantitative Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Feature Selection Techniques. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 15(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010020