Asymmetric Fingerprint Scheme for Vector Geographic Data Based on Smart Contracts

Abstract

1. Introduction

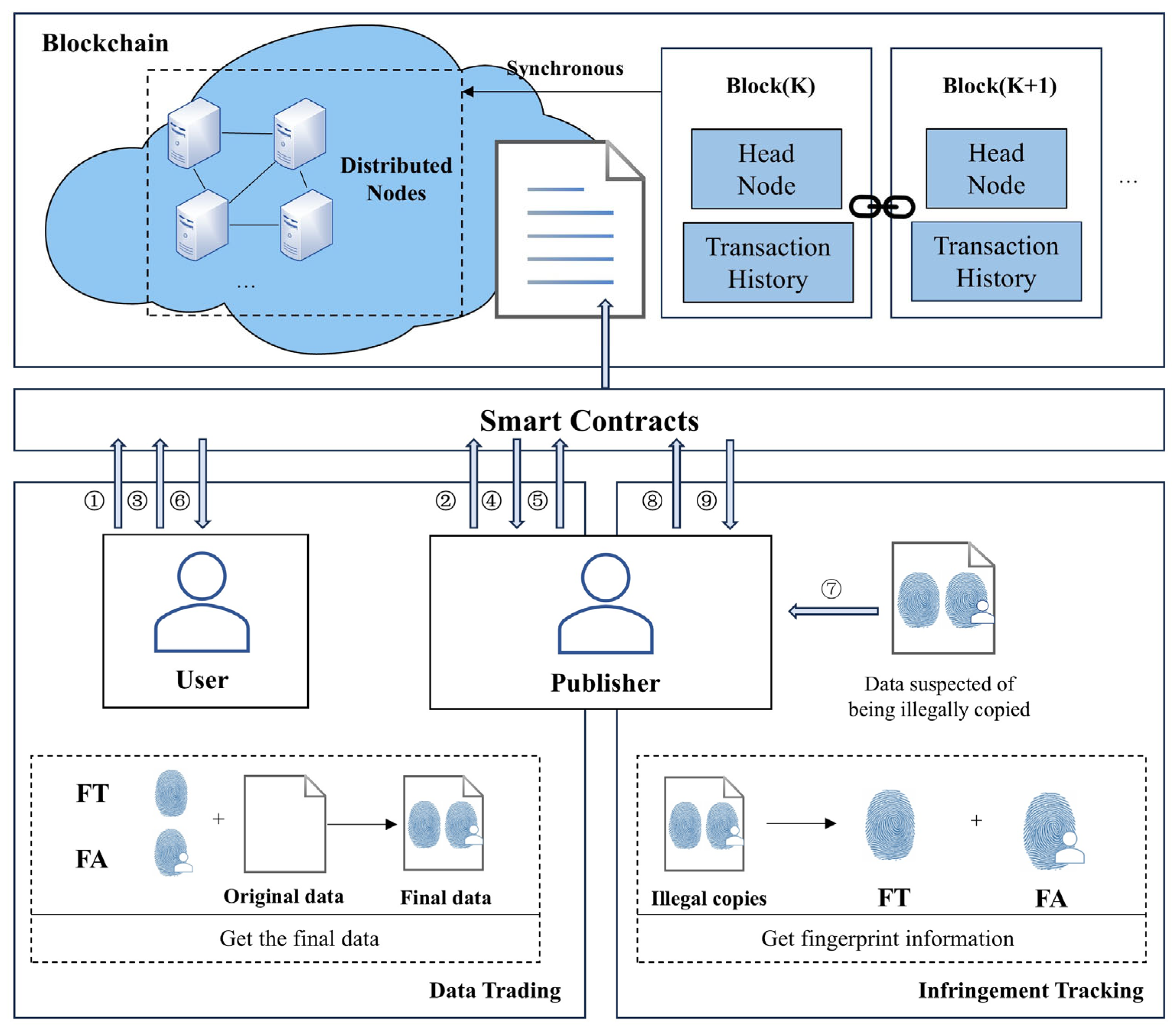

- An asymmetric fingerprinting scheme is proposed in which the merchant and the user jointly participate in fingerprint generation and embedding. This design prevents the merchant from obtaining the complete user fingerprint, thereby eliminating the inherent risk of fingerprint forgery and framing that exists in conventional symmetric fingerprinting schemes.

- A blockchain-enabled smart contract framework is developed to integrate fingerprint binding, data delivery, and automated dispute arbitration into a unified execution process. By embedding responsibility attribution logic directly into smart contracts, the proposed framework provides tamper-resistant, transparent, and third-party-free copyright protection for vector geographic data transactions.

- A collaborative technical framework is constructed by integrating GD-PBIBD-based fingerprint encoding, Paillier homomorphic encryption, and blockchain technology. Within this framework, GD-PBIBD encoding enhances resistance to collusion attacks, homomorphic encryption enables privacy-preserving fingerprint generation and tracing, and blockchain technology ensures verifiable execution and auditability. Collectively, these components enable accountable and trustworthy data transactions while preserving the geometric accuracy of vector geographic data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Paillier Encryption

2.2. Fingerprint Encoded

3. Overall Scheme Design and Smart Contract Framework

3.1. Adversary Model and Security Objectives

3.2. Smart Contract Overview

3.3. Smart Contract Process

| Algorithm 1. Trade Contract Execution Process |

| Input: B, S, message Output: status, events 1: if (buyer == 0 × 0 and seller == 0 × 0) then 2: if (B == 0 × 0 or S == 0 × 0 or B == S) then reject “Invalid parties” end if 3: if (caller != B and caller != S) then reject “Only buyer or seller can initialize” end if 4: buyer ← B 5: seller ← S 6: status ← Confirming 7: else 8: if (B != buyer or S != seller) then reject “Parties already set” end if 9: end if 10: if (caller == buyer) then 11: buyerConfirmed ← true 12: emit BuyerConfirmed(buyer) 13: else if (caller == seller) then 14: sellerConfirmed ← true 15: emit SellerConfirmed(seller) 16: else 17: reject “Only buyer or seller can confirm” 18: end if 19: if (buyerConfirmed and sellerConfirmed) then 20: status ← Confirmed 21: if (message != “”) then 22: if (caller == buyer) then emit MessageSent(buyer, seller, message) 23: else emit MessageSent(seller, buyer, message) 24: end if 25: end if 26: end if |

4. Asymmetric Fingerprint Algorithm Design

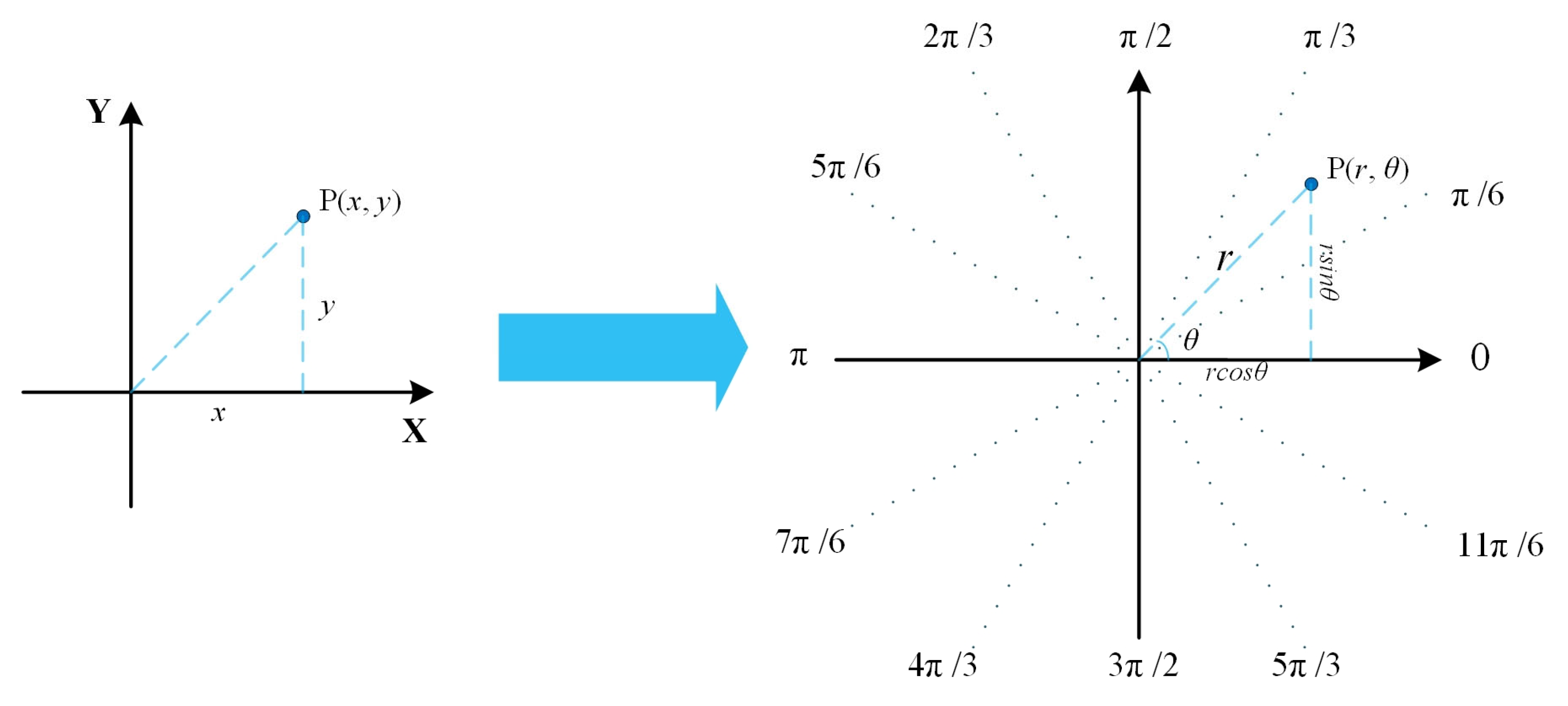

4.1. Fingerprint Embedding

4.2. Fingerprint Extraction

5. Experiments and Analysis

5.1. Analysis of Asymmetric Fingerprint Schemes

5.2. Prototype System Implementation

5.3. Smart Contract Performance Evaluation

5.4. Algorithm Performance Analysis

- Data precision and parameter sensitivity analysis

- 2.

- Encryption and decryption efficiency analysis

- 3.

- Algorithm robustness experiment

- 4.

- Comparative experiment

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, J.P.; Zhang, L.M.; Jiang, M.R.; Wang, H. Digital fingerprint algorithm for vector spatial data using GD-PBIBD coding. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2020, 8, 81–86+100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.P.; Zhang, L.M.; Jiang, M.R. A collusion-based vector spatial data fingerprinting scheme. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 2020, 45, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, K.; Devetsikiotis, M. Blockchains and smart contracts for the internet of things. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.R.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, B.W.; Deng, Y. Overview on the research status and development route of fully homomorphic encryption technology. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2024, 46, 1774–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.W. Privacy-preserving Hamming and Edit Distance Computation and Applications. Comput. Sci. 2022, 49, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.H.; Yu, H.T. Arbitration of digital fingerprint-based digital resource copyright. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 188, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Nisar, M.W.; Rashid, J.; Kim, J.; Kamran, M.; Hussain, A. A novel fingerprinting technique for data storing and sharing through clouds. Sensors 2021, 21, 7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W. A normalization-based watermarking scheme for 2D vector map data. Earth Sci. Inf. 2017, 10, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhu, C. A multiple watermarking algorithm for vector geographic data based on coordinate mapping and domain subdivision. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 19261–19279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, Q. Asymmetric fingerprinting based on 1-out-of-n oblivious transfer. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2010, 14, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, Q. Bandwidth efficient asymmetric fingerprinting scheme. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2012, 25, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Sui, A.; Lin, W.; Han, P. Research on the application of blockchain in copyright protection. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Culture-oriented Science & Technology (ICCST), Beijing, China, 28–31 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuribayashi, M.; Tanaka, H. Fingerprinting protocol for images based on additive homomorphic property. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2005, 14, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Ma, Z.; Luo, S. Blockchain-oriented privacy protection with online and offline verification in cross-chain system. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Information Security (ICBCTIS), Huaihua City, China, 15–17 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q. A novel invariant based commutative encryption and watermarking algorithm for vector maps. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf 2021, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Zong, L.F.; Jin, D.; Yuan, K. Security risk analysis and countermeasures in the circulation and use of data factors. Big Data Res. 2023, 9, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.H. A survey of digital fingerprinting. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2004, 21, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megias, D. Improved privacy-preserving P2P multimedia distribution based on recombined fingerprints. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2014, 12, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, R. HBRO: A registration oracle scheme for digital rights management based on heterogeneous blockchains. Commun. Netw. 2021, 14, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivanoglu, S. An asymmetric fingerprinting code for collusion-resistant buyer-seller watermarking. In Proceedings of the First ACM Workshop on Information Hiding and Multimedia Security, Montpellier, France, 17–19 June 2013; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.G.; Duan, H.T. A novel multi-stage watermarking scheme of vector maps. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 877–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red, V.A. Practical comparison of distributed ledger technologies for IoT. In Proceedings of the Disruptive Technologies in Sensors and Sensor Systems, Anaheim, CA, USA, 11–12 April 2017; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; Volume 10206, pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, C.; Gu, J. A multilevel digital watermarking protocol for vector geographic data based on blockchain. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2023, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Shimosawa, T.; Himura, Y. Operations smart contract to realize decentralized system operations workflow for consortium blockchain. IEICE Trans. Commun. 2022, 105, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappe, W.; Wu, M.; Wang, Z.J.; Liu, K.R. Anti-collusion fingerprinting for multimedia. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2003, 51, 1069–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jin, X.F. Application of surveying and mapping geographical information technology and data achievement service for territorial and spatial planning. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2020, 12, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.Y.; Dai, Q.Y.; Peng, Y.W.; Wang, W. Robust vector map watermarking algorithm in homomorphic encrypted domain. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2022, 24, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.-Y. Privacy-friendly blockchain based data trading and tracking. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Big Data Computing and Communications, Qingdao, China, 9–11 August 2019; pp. 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Ren, W.; Li, T.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, T.; Choo, K.-K.R. A multi-type and decentralized data transaction scheme based on smart contracts and digital watermarks. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 176, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, F.-Y. Blockchain: The State of the Art and Future Trends. Acta Autom. Sin. 2016, 42, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Zhang, L.M.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A digital fingerprinting algorithm of vector geographic data for multi-level distribution. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2023, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Yue, M.; Zhong-Yu, C.; Chang-Bing, T.; Xin, C. Zero-determinant strategy for the algorithm optimize of blockchain PoW consensus. In Proceedings of the 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Dalian, China, 26–28 July 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-J.; Hao, Q.; Kuang, W.; Liu, R.; Yu, T.; Zhang, X. Critical issues and optimization strategies in the territorial spatial planning monitoring-evaluation-warning system. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 2869–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.-T.; Zhang, H.-H.; Liu, G.; Luo, W.-L. Research on model system of monitoring-evaluation-warning for implementation supervision of territory spatial planning. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 2946–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tai, W.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. A blockchain-based spatial data trading framework. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, J.S.; Sun, M.Z.; Wang, J.Y.; Yang, K. Evolution of farmland abandonment research from 1993 to 2023 using CiteSpace-based scientometric analysis. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2024, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Comparison Category | Evaluation Indicator | Proposed Scheme | Liu et al., [35] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | Deployment cost | 2,762,930 Gas | 2,666,636 Gas |

| Runtime cost | 552,030 Gas | 349,542 Gas | |

| Functionality | Post-delivery responsibility traceability | Leaked data can be traced back to specific transaction participants | Data redistribution cannot be traced after transaction completion |

| On-chain recording of data delivery evidence | Delivery identifiers are recorded on-chain together with transaction states | Delivery actions and outcomes are not recorded | |

| Technical non-repudiation capability | User fingerprints are cryptographically bound to transaction processes | Only asset registration and transaction records are maintained | |

| Infringement dispute handling mechanism | Technical judgments are produced via on-chain fingerprint comparison | Disputes rely on off-chain manual or legal procedures |

| Data | Type | Size/KB | The Number of Vertices | The Number of Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Point | 377 | 13,769 | 13,769 |

| B | Polyline | 6917 | 338,986 | 29,625 |

| C | Polygon | 1140 | 70,084 | 581 |

| Data | n | Max Deviation | RMSE | Points with Deviation < 0.0001 m (%) | Total Number of Data Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 5.449575 × 10−5 | 1.884387 × 10−5 | 100% | 13,769 |

| 3 | 5.285191 × 10−5 | 1.879556 × 10−5 | 100% | ||

| 4 | 5.449575 × 10−5 | 1.886346 × 10−5 | 100% | ||

| B | 2 | 7.428597 × 10−6 | 1.390115 × 10−6 | 100% | 338,986 |

| 3 | 7.428597 × 10−6 | 1.394993 × 10−6 | 100% | ||

| 4 | 7.221957 × 10−6 | 1.397788 × 10−6 | 100% | ||

| C | 2 | 5.072406 × 10−5 | 2.253388 × 10−5 | 100% | 70,084 |

| 3 | 5.125154 × 10−5 | 2.274152 × 10−5 | 100% | ||

| 4 | 5.072406 × 10−5 | 2.263077 × 10−5 | 100% |

| Data | Number of Coordinates to Be Encrypted | Number of Elements to be Encrypted | Encryption Time (s) | Decryption Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12,685 | 3734 | 0.59 | 0.44 |

| 2 | 24,898 | 6724 | 1.15 | 0.88 |

| 3 | 50,704 | 10,654 | 2.45 | 1.95 |

| 4 | 105,422 | 17,911 | 4.86 | 3.48 |

| 5 | 249,595 | 31,512 | 11.80 | 9.74 |

| 6 | 425,900 | 44,734 | 20.42 | 16.91 |

| 7 | 841,486 | 76,985 | 42.61 | 33.31 |

| Degree of Attack | Fingerprint Type | Point | Polyline | Polygon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 m along the X-axis | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| 500 m along the Y-axis | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Scaling 0.5 | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Scaling 2.0 | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Clipping 10% | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Clipping 30% | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Add 20% | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Add 40% | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Delete20% | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Delete 40% | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Rotate 60° | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints | ||||

| Rotate 120° | Tracking fingerprints | |||

| Accuse fingerprints |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Qu, R.; Tan, T.; Liu, S.; Ren, N. Asymmetric Fingerprint Scheme for Vector Geographic Data Based on Smart Contracts. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2026, 15, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010015

Wang L, Zhang L, Qu R, Tan T, Liu S, Ren N. Asymmetric Fingerprint Scheme for Vector Geographic Data Based on Smart Contracts. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2026; 15(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lei, Liming Zhang, Ruitao Qu, Tao Tan, Shuaikang Liu, and Na Ren. 2026. "Asymmetric Fingerprint Scheme for Vector Geographic Data Based on Smart Contracts" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 15, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010015

APA StyleWang, L., Zhang, L., Qu, R., Tan, T., Liu, S., & Ren, N. (2026). Asymmetric Fingerprint Scheme for Vector Geographic Data Based on Smart Contracts. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 15(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010015