Context-Aware Knowledge Graph Learning for Point-of-Interest Recommendation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Data sparsity: Check-in data is inherently sparse, making it difficult to model user interests effectively using only check-in records.

- (2)

- Underutilization of contextual information: Many existing methods focus on static user–POI relationships without adequately capturing the dynamic spatio-temporal context embedded in check-ins.

- (3)

- Limited integration of social influence: Social correlations among users are often oversimplified, resulting in an inadequate capture of preference propagation among friends.

- (1)

- Multi-dimensional context integration: We construct a knowledge graph that incorporates user social networks, temporal sequences, and geographical information, enhancing the semantic representation capability of the data.

- (2)

- Spatio-temporal feature modeling: We introduce a Spatio-Temporal Gated Graph Neural Network (STG-GNN) to model user check-in sequences, capturing both temporal dependencies and spatial influences on user behavior.

- (3)

- Social influence propagation: We apply a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to optimize the propagation of preferences between user groups and POI regions, thus enhancing the personalization of recommendations.

2. Related Work

- (1)

- Contextual information is often insufficiently integrated, leading to a lack of fine-grained understanding of user behaviors.

- (2)

- Relation modeling in sparse data environments tends to be coarse-grained, reducing recommendation robustness.

- (3)

- The ability to fuse multi-source heterogeneous data remains limited.

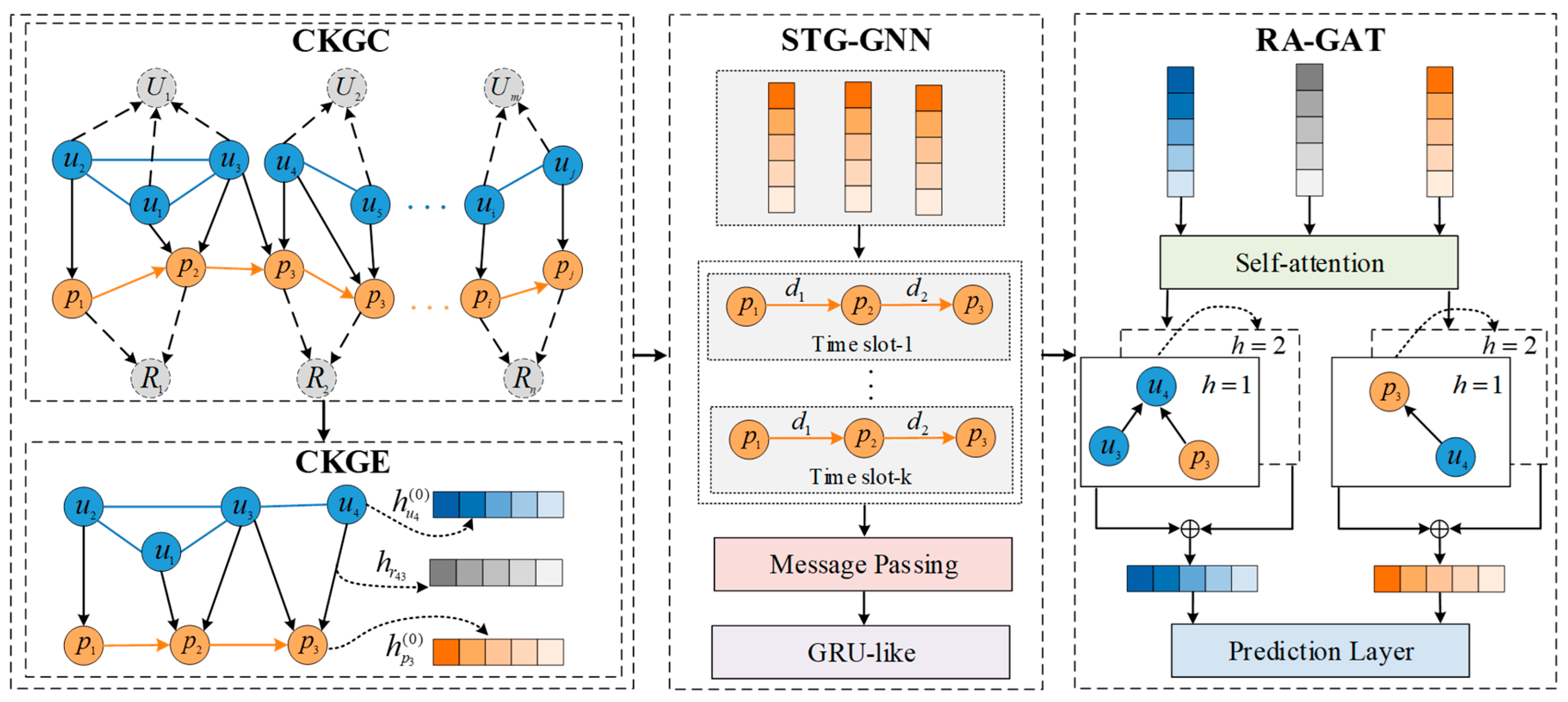

3. Overview

- (1)

- The first component, CKGC, constructs a context-aware knowledge graph (KG) that integrates multiple types of entities and relations, including users, POIs, check-in behaviors, POI categories, and temporal contexts. To enhance the expressiveness of the graph, additional edges are added to represent spatial and temporal dependencies, as well as social relationships among users. This comprehensive graph structure provides a unified representation of heterogeneous contextual information and serves as the foundation for subsequent embedding learning.

- (2)

- Based on the constructed KG, the second component focuses on embedding learning. To capture the semantics of different relations among entities, CKGL employs the Translational Distance Model with Relation-Specific Spaces (TransR) embedding model [30] to project entities and relations into a continuous low-dimensional space while preserving relation-specific semantics. This embedding process captures latent dependencies among users and POIs and enables the model to represent multi-relational information in a unified space. The learned embeddings serve as the initial input for subsequent graph neural network modeling, allowing high-level features to be propagated and aggregated effectively.

- (3)

- The third component, STG-GNN, is designed to capture higher-order spatio-temporal dependencies within the knowledge graph. It introduces a gated mechanism to control the flow of spatial and temporal information during message propagation, ensuring that both short-term and long-term dependencies are adaptively modeled. By aggregating neighborhood information through the gating mechanism, the model learns context-aware representations that reflect users’ evolving user interests and temporal preferences. STG-GNN effectively enhances the spatial–temporal reasoning ability of CKGL, providing richer behavioral representations for recommendation.

- (4)

- The final component, RA-GAT, further refines the learned embeddings by introducing relation-specific attention weights. Unlike conventional GATs that treat all neighboring nodes equally, RA-GAT distinguishes different relation types and assigns adaptive weights according to their semantic importance. Through this relation-aware attention mechanism, the model selectively amplifies informative connections while suppressing less relevant ones, thereby improving the interpretability and accuracy of recommendations. Ultimately, CKGL fuses multi-source contextual information—spatial, temporal, and social—within RA-GAT to generate a personalized ranking of candidate POIs for each user.

4. The Proposed POI Recommendation Method

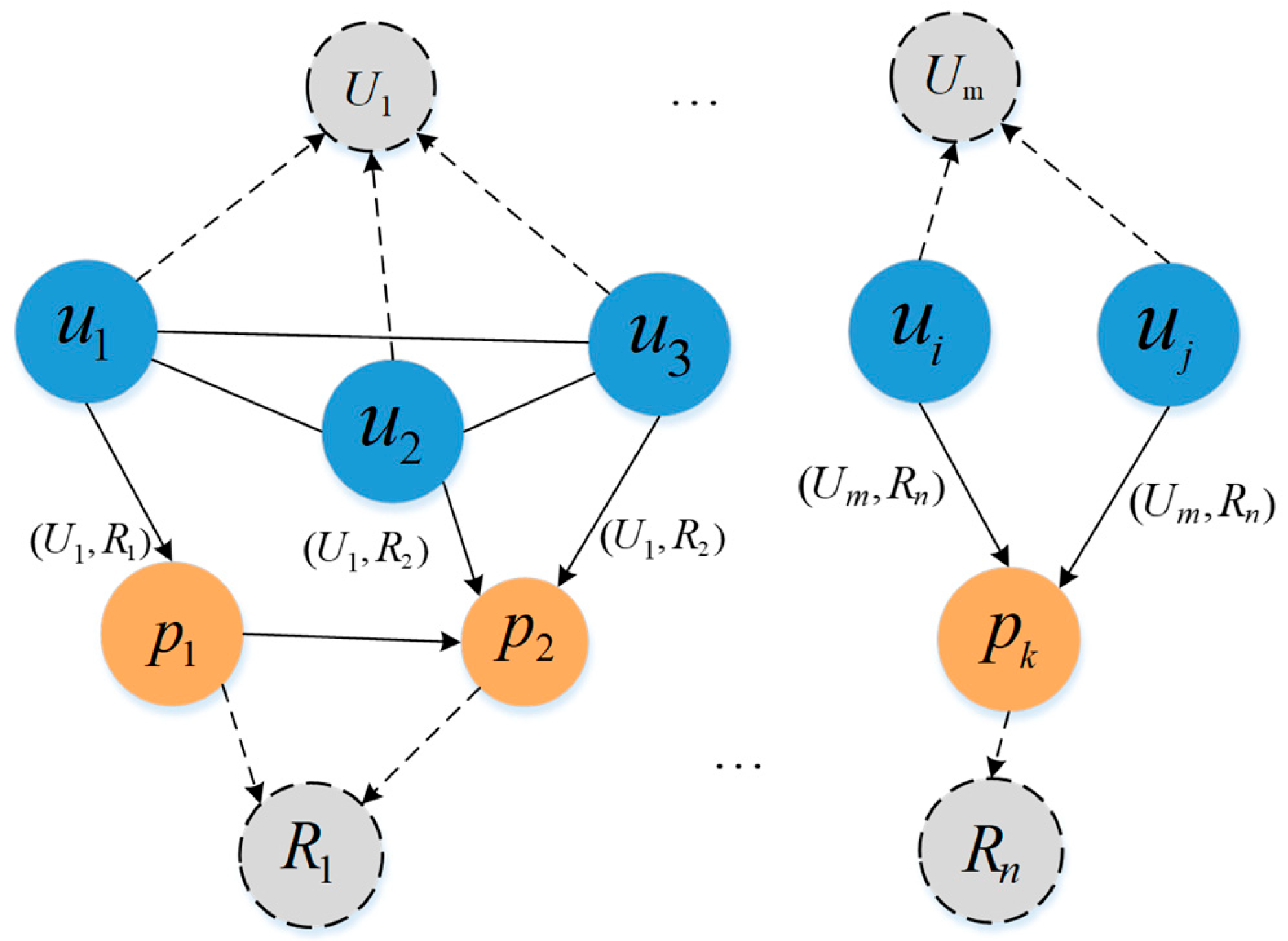

4.1. Context-Aware Knowledge Graph Construction

- (1)

- User–User Group (membership relation): User groups are generated by clustering users according to behavioral similarity, and each user is connected to the corresponding group. User groups represent collective preference patterns at the group level, which helps alleviate data sparsity and enhances the generalization capability of the recommendation model. Details of user-group construction are presented in Section 4.1.1.

- (2)

- User–User (social relation): This relation is constructed based on friendships in social networks, representing the propagation and mutual influence of preferences among users.

- (3)

- POI–ROI (belonging relation): POIs are clustered into ROIs using spatial clustering, and each POI is linked to its corresponding ROI. ROIs capture the spatial organization of POIs, reflecting how individual POIs are spatially grouped into higher-level regional structures. ROIs enrich the representation of geographical contextual semantics within the knowledge graph. The details of ROI construction are described in Section 4.1.2.

- (4)

- POI–POI (temporal sequence relation): User check-in times are discretized into multiple time slots, and directed edges are established between consecutive POIs according to the visit order within each slot. This relation characterizes the temporal evolution of user mobility patterns and models’ sequential dependencies between POIs. The time-slot division follows the discretization method proposed in our previous work [31], where one day is divided into 96 time slots.

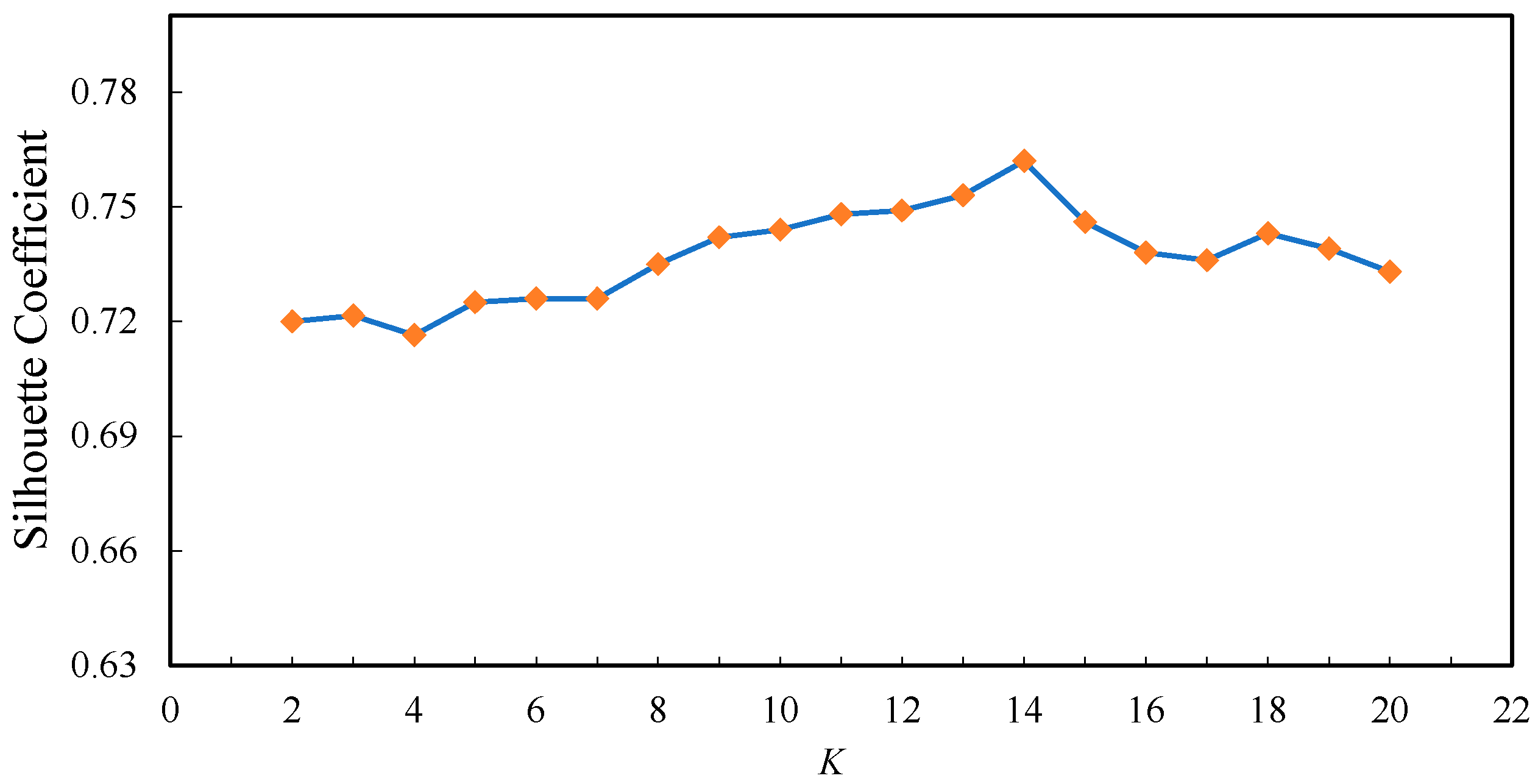

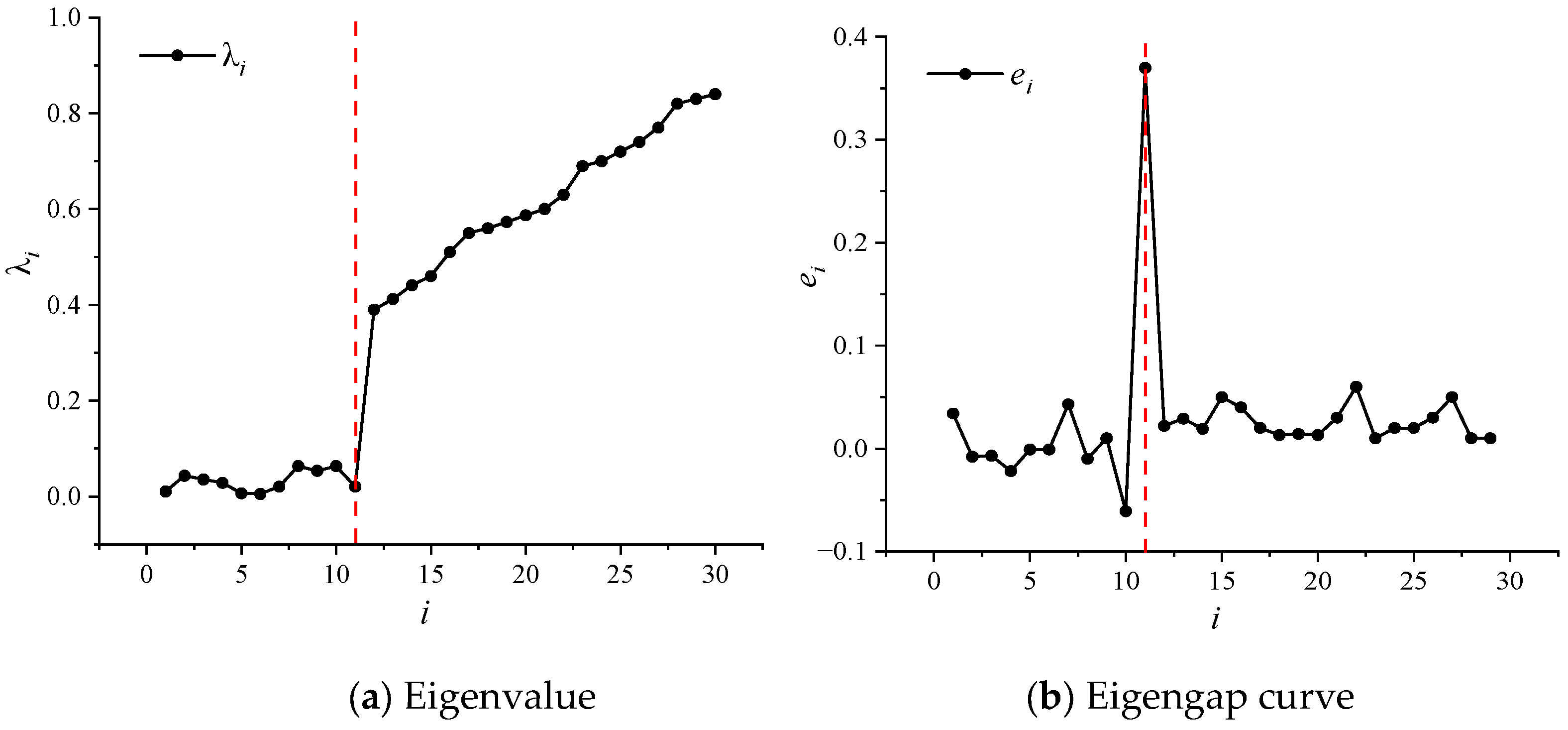

4.1.1. User Group Clustering Based on Similarity Measures

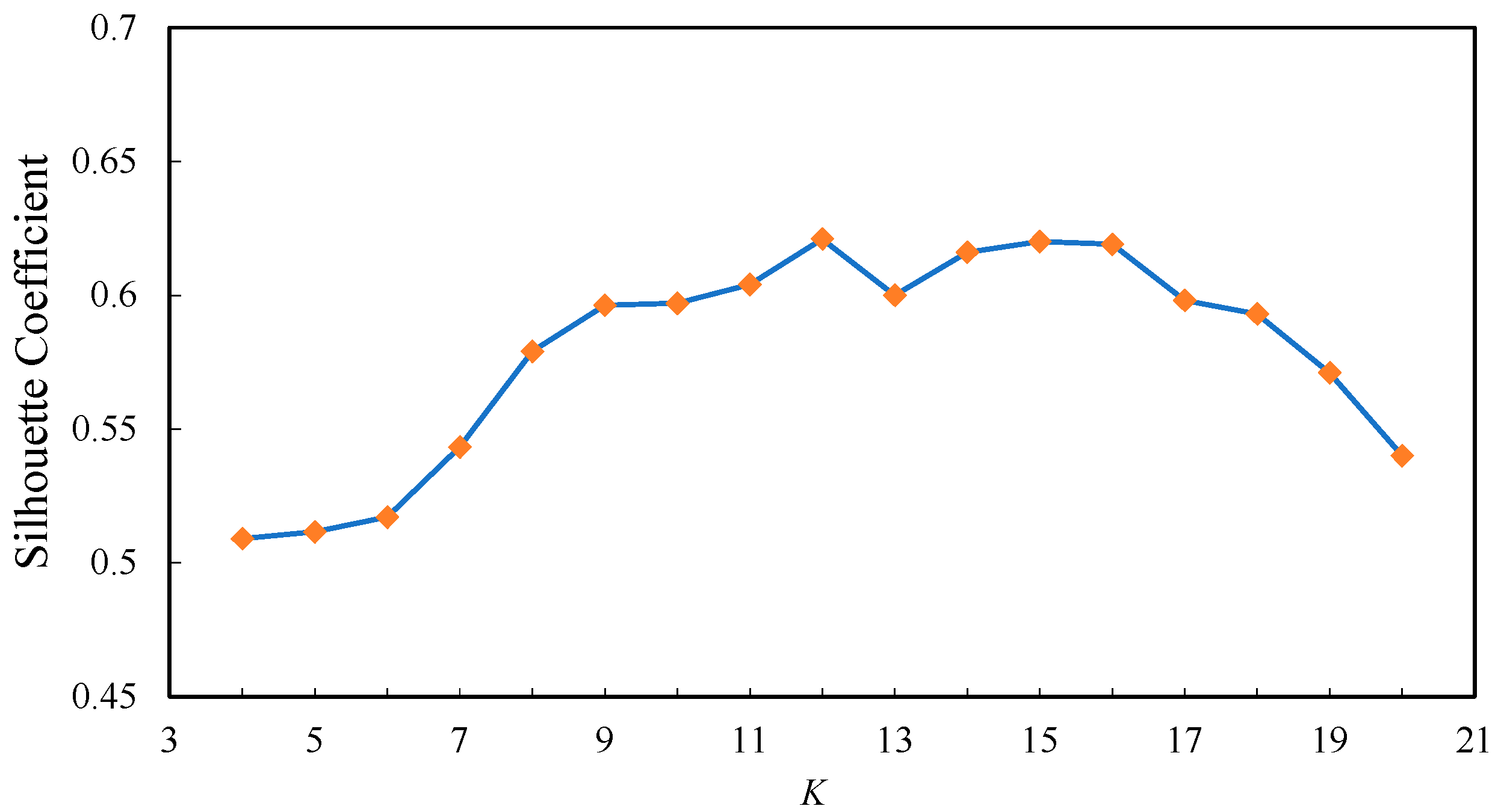

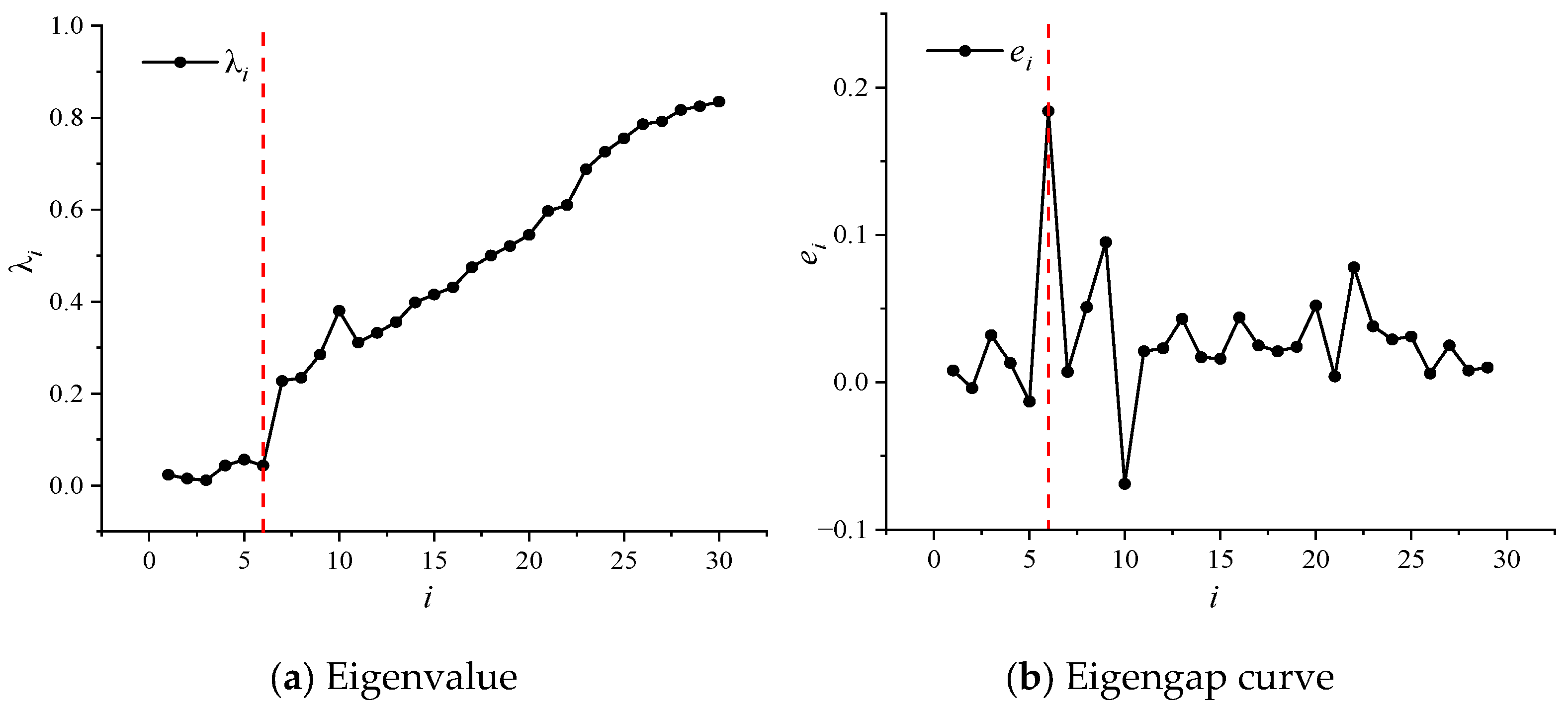

4.1.2. ROI Clustering Based on Spatial Proximity

4.2. Context-Aware Knowledge Graph Embedding

- (1)

- Social relationships between users: (user, friendship relation, user);

- (2)

- Check-in relationships based on spatially clustered user groups: (user, user-group–ROI check-in relation, POI);

- (3)

- POI sequential visit relationships: (POI, sequential check-in relation, POI).

4.3. Spatio-Temporal Gated Graph Neural Network

4.4. Relation-Aware Graph Attention Network

5. Experiments and Analysis

5.1. Datasets

5.2. Computing Environment

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

5.4. Knowledge Graph Parameters

5.5. Experimental Results and Analysis

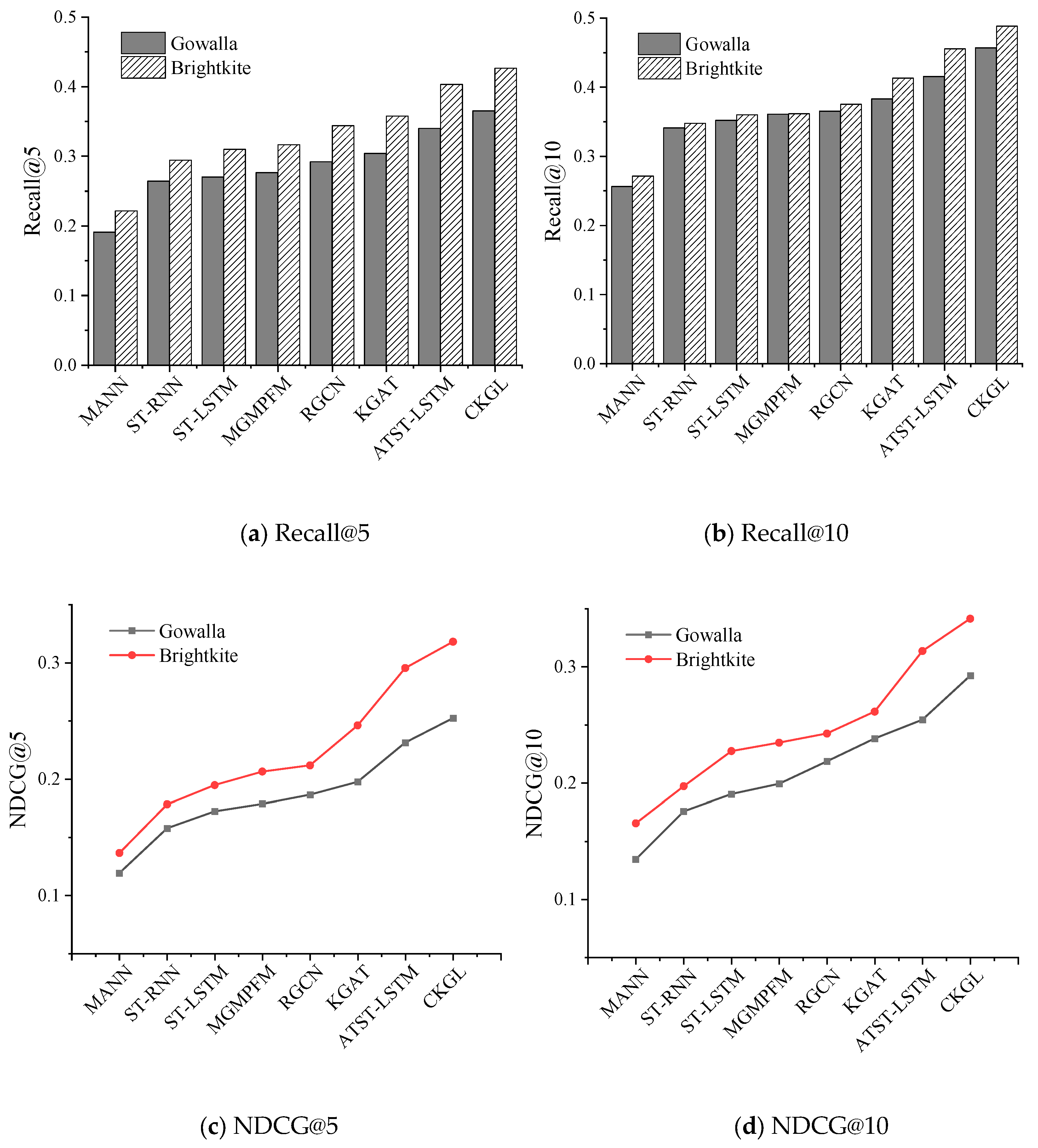

- MANN [35]: Introduces a memory mechanism into the recommendation system and integrates it with collaborative filtering.

- ST-RNN [36]: Models local spatio-temporal contexts using time-dependent transition matrices for different temporal intervals and distance-dependent matrices for geographical distances.

- ST-LSTM [37]: Proposes a spatio-temporal gated network (STGN) that models personalized sequential patterns based on users’ long-term and short-term preferences.

- MGMPFM [7]: A matrix factorization-based POI recommendation method that employs a multi-center Gaussian model to capture the geographical influence of users’ check-in behaviors.

- RGCN [38]: Extends the GCN to handle heterogeneous relationships within graphs.

- KGAT [27]: Incorporates attention mechanisms and knowledge graph information to enhance user–POI interaction modeling.

- ATST-LSTM [39]: Based on an LSTM network, integrates spatio-temporal information and attention mechanisms to capture sequential patterns in users’ check-in behaviors.

5.5.1. Performance Comparison

- (1)

- Multi-source contextual fusion: CKGL integrates user behavior, geographical location, and social network data within a unified knowledge graph, enabling the model to capture richer contextual semantics and structured representations between users and POIs.

- (2)

- Spatio-temporal graph modeling: By incorporating the STG-GNN network, CKGL effectively models the complex temporal evolution and spatial dependencies of user check-in behaviors, providing a finer representation of user behavioral dynamics.

- (3)

- Relation-aware graph attention mechanism: CKGL adopts a relation-aware graph attention mechanism to refine the aggregation of heterogeneous relational information, thereby enhancing both the accuracy and interpretability of user preference propagation across the knowledge graph.

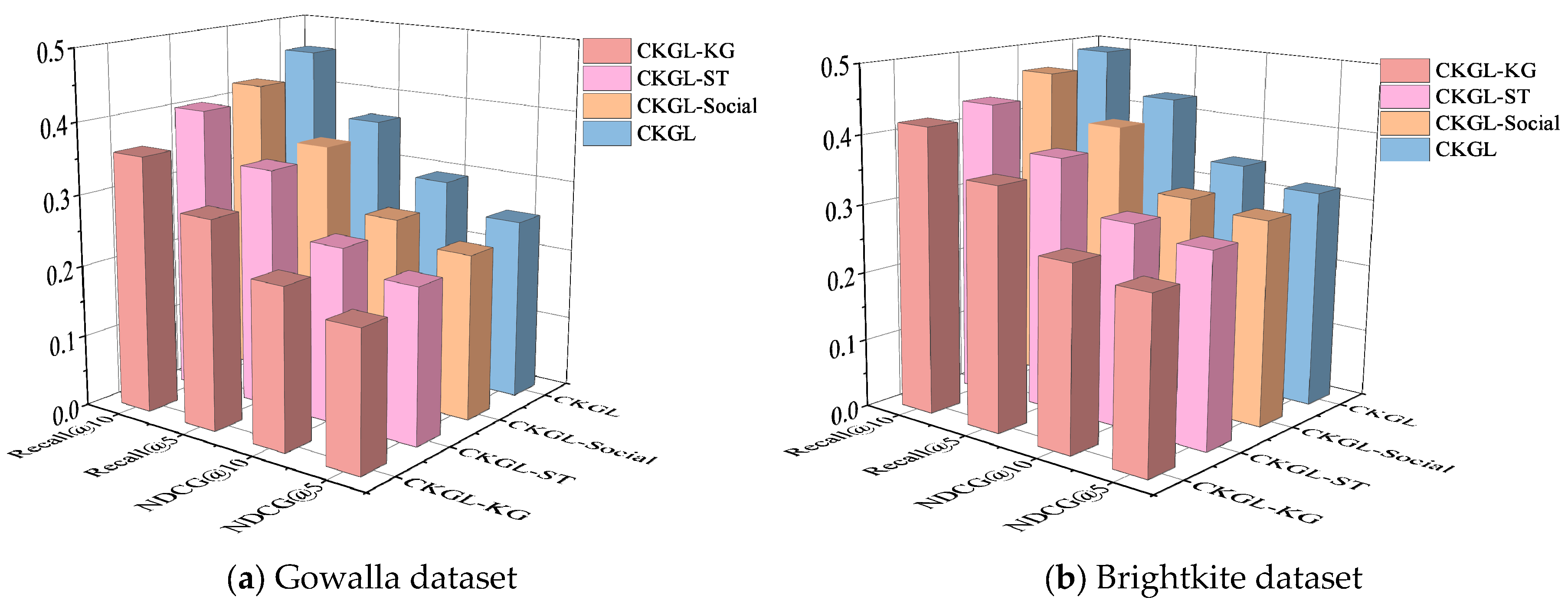

5.5.2. Ablation Study

- CKGL-KG: This variant retains only the basic structural relations in the knowledge graph, including user check-ins and geographical associations between POIs, while excluding the semantic enrichment introduced by entity clustering and multi-relational embedding.

- CKGL-ST: This variant models sequential user–POI relationships but omits the STG-GNN module for spatio-temporal feature extraction, without integrating temporal dynamics and spatial dependencies.

- CKGL-Social: This variant focuses solely on social relationships within the knowledge graph, without incorporating POI-related or spatio-temporal relational information.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boualaoui, B.; Zellou, A.; Berquedich, M. Knowledge graph-based recommender systems to mitigate data sparsity: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2025, 19, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Gao, Z.; Yu, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, F. Joint modeling of multimodal information based on dynamic and static knowledge graphs for next POI recommendation. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2025, 12, 3985–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, G.; Smith, B.; York, J. Amazon.com recommendations: Item-to-item collaborative filtering. IEEE Internet Comput. 2003, 7, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Yin, P.; Lee, W.-C.; Lee, D.-L. Exploiting geographical influence for collaborative point-of-interest recommendation. In Proceedings of the 34th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Beijing, China, 24–28 July 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Tang, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, H. Exploring temporal effects for location recommendation on location-based social networks. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Hong Kong, China, 12–16 October 2013; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Zhang, J.; Yorke-Smith, N. TrustSVD: Collaborative filtering with both the explicit and implicit influence of user trust and of item ratings. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Austin, TX, USA, 25–30 January 2015; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Yang, H.; King, I.; Lyu, M. Fused matrix factorization with geographical and social influence in location-based social networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–26 July 2012; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, W.; Liu, G.; Jiang, C.; Qi, L. Partition-based collaborative tensor factorization for POI recommendation. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2017, 4, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, M.; Hong, H.; Liao, L. A time-aware personalized point-of-interest recommendation via high-order tensor factorization. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2017, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G. Recurrent neural networks: A comprehensive review of architectures, variants, and applications. Information 2024, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Selwi, S.M.; Hassan, M.F.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Muneer, A.; Sumiea, E.H.; Alqushaibi, A.; Ragab, M.G. RNN-LSTM: From applications to modeling techniques and beyond—Systematic review. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivan, A.; Gananathan, K.; Pal Nesamony Rose Mary, J.D.; Balasubramanian, S. A systematic survey of graph convolutional networks for artificial intelligence applications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 15, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, P.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; He, X.; Yiu, S.-M.; Yin, H. A survey on point-of-interest recommendation: Models, architectures, and security. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 3153–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-S.; Shih, W.-Y.; Gau, H.-Y.; Chung, K.-C.; Huang, J.-L. On successive point-of-interest recommendation. World Wide Web 2019, 22, 1151–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. CANS-Net: Context-aware non-successive modeling network for next point-of-interest recommendation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.10054. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Zhou, C.; Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Guo, L. Social recommendation with an essential preference space. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; Ju, W.; Hou, X.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Lei, J.; Zhang, M. DisenPOI: Disentangling sequential and geographical influence for point-of-interest recommendation. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Singapore, 27 February–3 March 2023; pp. 508–516. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, W.; Qin, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, M. Kernel-based substructure exploration for next POI recommendation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Orlando, FL, USA, 28 November–1 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Scarselli, F.; Gori, M.; Tsoi, A.C.; Hagenbuchner, M.; Monfardini, G. The graph neural network model. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2008, 20, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Chu, X. Leveraging graph neural networks for point-of-interest recommendations. Neurocomputing 2021, 462, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, S.; Zang, C. A graph neural network-based algorithm for point-of-interest recommendation using social relation and time series. Int. J. Web Serv. Res. 2021, 18, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Perozzi, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Skiena, S. DeepWalk: Online learning of social representations. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 24–27 August 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 701–710. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, A.; Leskovec, J. node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 855–864. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Qu, M.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Yan, J.; Mei, Q. LINE: Large-scale information network embedding. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web, Florence, Italy, 18–22 May 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1067–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Dou, Y.; Ma, J.; Yu, P.S. ConsisRec: Enhancing GNN for social recommendation via consistent neighbor aggregation. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 11–15 July 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 2141–2145. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, N. Point-of-interest recommendation model based on graph convolutional neural network. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, M.; Chua, T.-S. KGAT: Knowledge graph attention network for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 950–958. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wan, H.; Guo, S.; Huang, H.; Zheng, S.; Li, J.; Lin, S.; Lin, Y. Building and exploiting spatial–temporal knowledge graph for next POI recommendation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 258, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, C.; Bian, J.; Deng, J.; Shen, G.; Kong, X. KDRank: Knowledge-driven user-aware POI recommendation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 278, 110884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Dong, G.; Hou, C.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Using TransR to enhance drug repurposing knowledge graph for COVID-19 and its complications. Methods 2024, 221, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, K.; Chen, S. Context-aware point-of-interest recommendation based on similar user clustering and tensor factorization. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berahmand, K.; Saberi-Movahed, F.; Sheikhpour, R.; Li, Y.; Jalili, M. A comprehensive survey on spectral clustering with graph structure learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyal, M.; Sharma, S. A review on analysis of K-means clustering machine learning algorithm based on unsupervised learning. J. Artif. Intell. Syst. 2024, 6, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tarlow, D.; Brockschmidt, M.; Zemel, R. Gated graph sequence neural networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.05493. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z. Sequential recommendation with user memory networks. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM), Marina Del Rey, CA, USA, 5–9 February 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Predicting the next location: A recurrent model with spatial and temporal contexts. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Sheng, V.S. Where to go next: A spatio-temporal LSTM model for next POI recommendation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.06671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichtkrull, M.; Kipf, T.N.; Bloem, P.; Van Den Berg, R.; Titov, I.; Welling, M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 15th European Semantic Web Conference (ESWC 2018), Heraklion, Greece, 3–7 June 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 593–607. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. An attention-based spatiotemporal LSTM network for next POI recommendation. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2019, 14, 1585–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Gowalla | Brightkite |

|---|---|---|

| Number of users | 5628 | 4844 |

| Number of POIs | 31,803 | 7675 |

| Number of friendship relations | 46,001 | 93,036 |

| Number of check-ins | 620,683 | 388,148 |

| Model | Gowalla | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall@5 | Recall@10 | NDCG@5 | NDCG @10 | |

| MANN | 0.1907 | 0.2562 | 0.1193 | 0.1345 |

| ST-RNN | 0.2643 | 0.3413 | 0.1577 | 0.1756 |

| ST-LSTM | 0.2702 | 0.3523 | 0.1723 | 0.1905 |

| MGMPFM | 0.2765 | 0.3612 | 0.1787 | 0.1993 |

| RGCN | 0.2922 | 0.3655 | 0.1865 | 0.2185 |

| KGAT | 0.3042 | 0.3833 | 0.1975 | 0.2382 |

| ATST-LSTM | 0.3402 | 0.4156 | 0.2312 | 0.2543 |

| CKGL | 0.3652 | 0.4572 | 0.2523 | 0.2924 |

| Model | Brightkite | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall@5 | Recall@10 | NDCG@5 | NDCG @10 | |

| MANN | 0.2217 | 0.2715 | 0.1365 | 0.1654 |

| ST-RNN | 0.2945 | 0.3479 | 0.1783 | 0.1971 |

| ST-LSTM | 0.3101 | 0.3602 | 0.1947 | 0.2274 |

| MGMPFM | 0.3166 | 0.3618 | 0.2064 | 0.2346 |

| RGCN | 0.3441 | 0.3755 | 0.2117 | 0.2425 |

| KGAT | 0.3577 | 0.4133 | 0.2461 | 0.2614 |

| ATST-LSTM | 0.4033 | 0.4557 | 0.2955 | 0.3136 |

| CKGL | 0.4266 | 0.4885 | 0.3182 | 0.3414 |

| Model | Gowalla | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall@5 | Recall@10 | NDCG@5 | NDCG @10 | |

| CKGL-KG | 0.2912 | 0.3579 | 0.1934 | 0.2236 |

| CKGL-ST | 0.3347 | 0.4023 | 0.2167 | 0.2471 |

| CKGL-Social | 0.3475 | 0.4216 | 0.2313 | 0.2611 |

| CKGL | 0.3652 | 0.4572 | 0.2523 | 0.2924 |

| Model | Brightkite | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recall@5 | Recall@10 | NDCG@5 | NDCG @10 | |

| CKGL-KG | 0.3523 | 0.4172 | 0.2514 | 0.2677 |

| CKGL-ST | 0.3721 | 0.4332 | 0.2825 | 0.2981 |

| CKGL-Social | 0.4001 | 0.4663 | 0.3005 | 0.3122 |

| CKGL | 0.4266 | 0.4885 | 0.3182 | 0.3414 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, K.; Han, P. Context-Aware Knowledge Graph Learning for Point-of-Interest Recommendation. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2026, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010014

Zhou Y, Zhang D, Zhou K, Han P. Context-Aware Knowledge Graph Learning for Point-of-Interest Recommendation. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2026; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yan, Di Zhang, Kaixuan Zhou, and Pengcheng Han. 2026. "Context-Aware Knowledge Graph Learning for Point-of-Interest Recommendation" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010014

APA StyleZhou, Y., Zhang, D., Zhou, K., & Han, P. (2026). Context-Aware Knowledge Graph Learning for Point-of-Interest Recommendation. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi15010014