Can Urban Information Infrastructure Development Improve Resident Health? Evidence from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Policy Background and Research Hypothesis

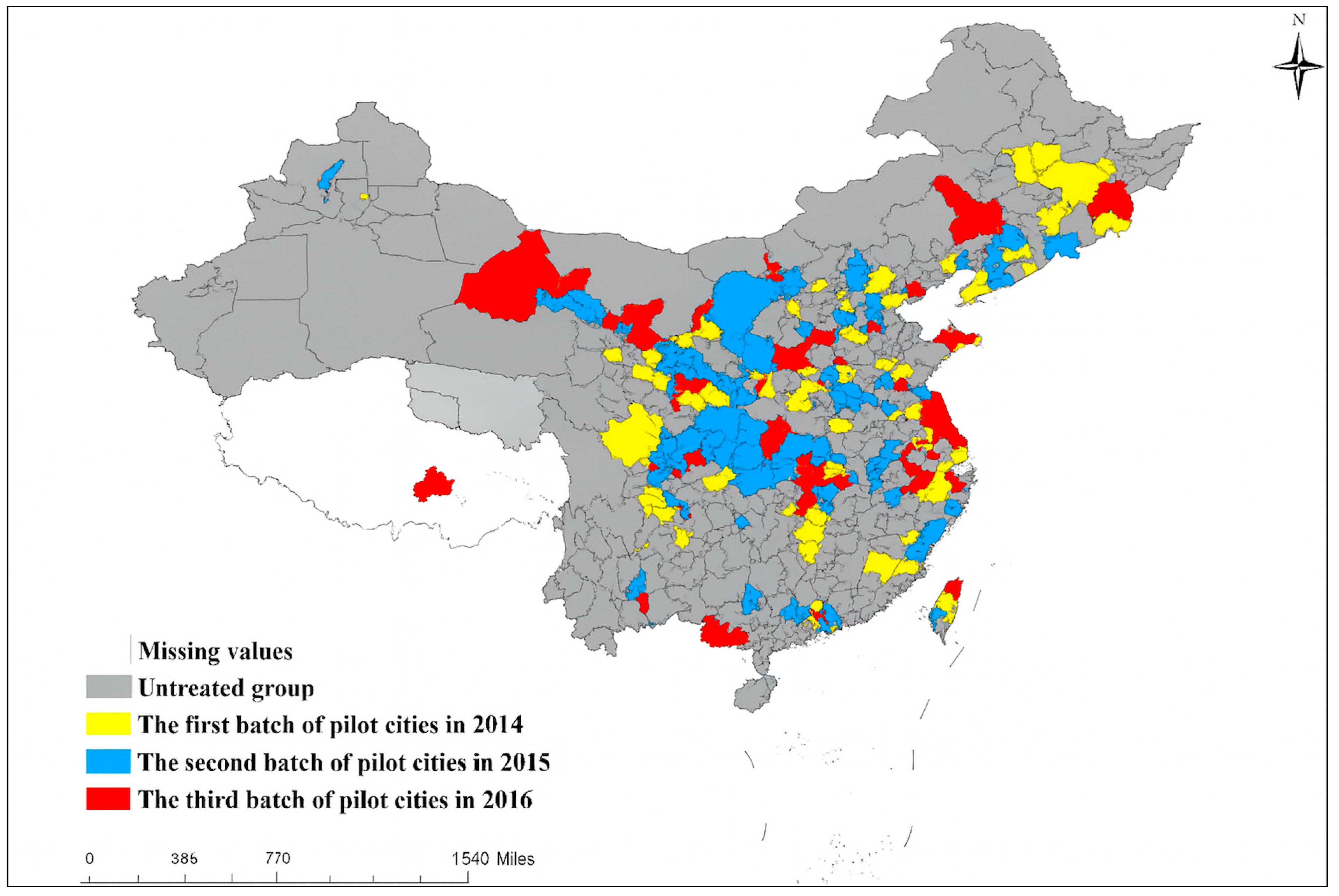

2.1. Policy Background

2.2. Research Hypothesis

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Data

3.2. Econometric Model

3.3. Variables

4. Results

4.1. Impact of Urban Information Infrastructure Development on Resident Health

4.2. Further Analysis

4.2.1. Differences in the Impact of Urban Information Infrastructure Development on Different Health Indicators

4.2.2. Mechanism of Urban Information Infrastructure Development Affecting Resident Health

4.2.3. Moderating Effects of Resident Healthcare Environment

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Individual-Level Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.2. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Re-Estimation Based on PSM-DID

4.4.2. Re-Estimation Using Different Dependent Variable

4.4.3. Re-Estimation with Additional City-Level Control Variables

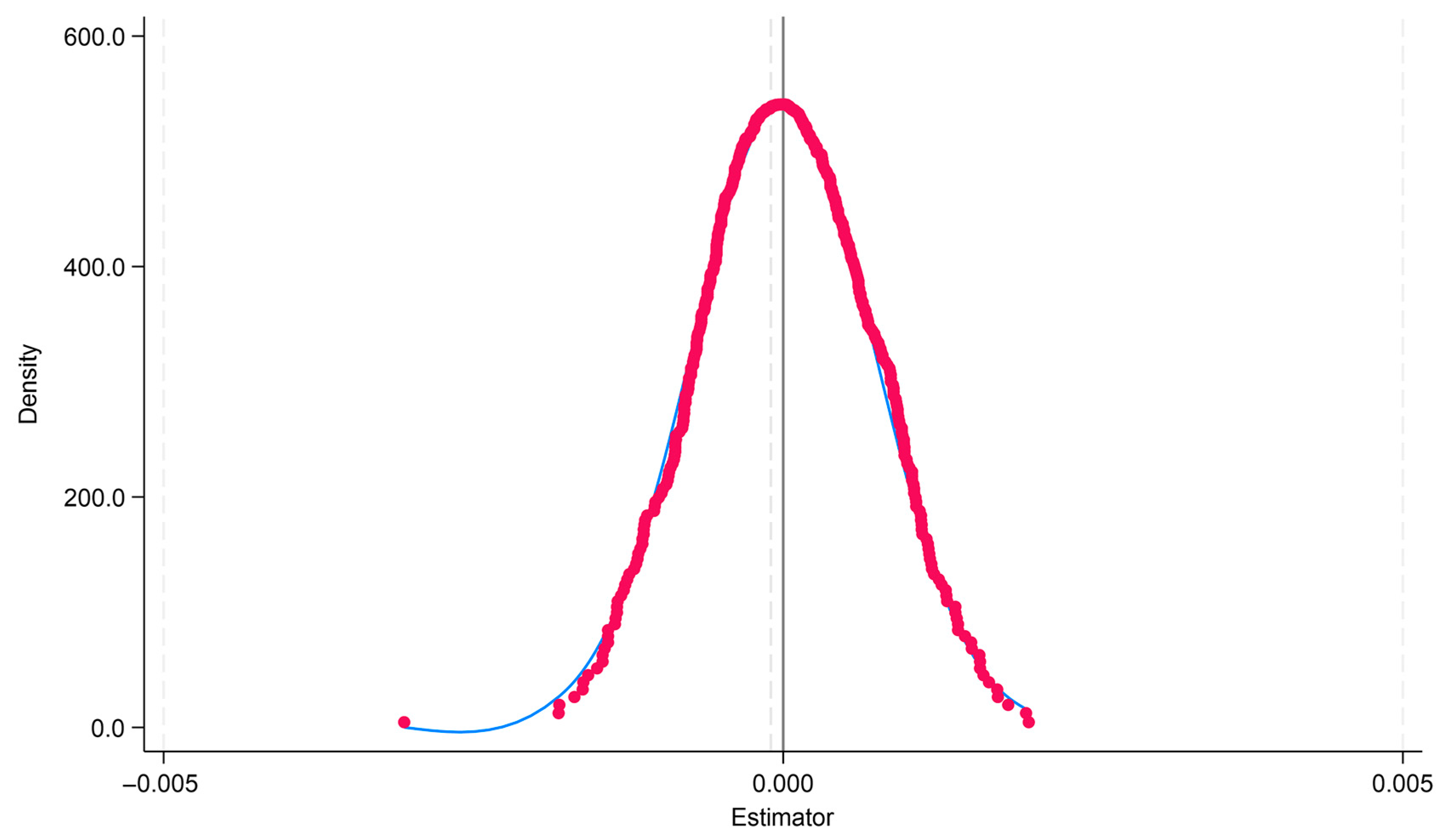

4.4.4. Placebo Test

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bergmark, K.H.; Bergmark, A.; Findahl, O. Extensive Internet Involvement—Addiction or Emerging Lifestyle? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 4488–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ba, N.; Ren, S.; Xu, L.; Chai, J.; Irfan, M.; Hao, Y.; Lu, Z.-N. The Impact of Internet Development on the Health of Chinese Residents: Transmission Mechanisms and Empirical Tests. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 81, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, Z.N.; Rahmani, A.M.; Hosseinzadeh, M. The Role of the Internet of Things in Healthcare: Future Trends and Challenges. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 199, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald, H.S.; Dube, C.E.; Anthony, D.C. Untangling the Web—The Impact of Internet Use on Health Care and the Physician–Patient Relationship. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 68, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, J.C.S.; Ching, C.B.D.; Co, S.P.S.; Noble, H.O.; Barcelo, A.B. LifeDoc: Availability and Monitoring System of Online Medical Consultation. In Proceedings of the 2021 11th IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), Penang, Malaysia, 27 August 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Batham, V.; Modi, B.S.; Thakur, C. Impact of Digital Screen Use in Relation to Dry Eye Symptoms and Quality of Sleep: A Study in Tertiary Care Centre. J. Adv. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 5, 2415–2419. [Google Scholar]

- Šmotek, M.; Fárková, E.; Manková, D.; Kopřivová, J. Evening and Night Exposure to Screens of Media Devices and Its Association with Subjectively Perceived Sleep: Should “Light Hygiene” Be given More Attention? Sleep Health 2020, 6, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarfaj, K.A.; Rahman, M.M.H. The Risk Assessment of the Security of Electronic Health Records Using Risk Matrix. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshta, I.; Odeh, A. Security and Privacy of Electronic Health Records: Concerns and Challenges. Egypt. Inf. J. 2021, 22, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health; Institute for Futures Studies: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991; Volume 27, pp. 4–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Fei, J.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Xie, X. Environmental Determinants of Dynamic Jogging Patterns: Insights from Trajectory Big Data Analysis and Interpretable Machine Learning. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 178, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Xie, X.; Tian, Z. Deciphering Spatiotemporal Patterns and Mobility Network of Outdoor Jogging Utilizing Large-Scale GPS Trajectory Data. Cities 2025, 165, 106185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, H.; Fei, J.; Xie, X. The Role of Blue-Green Spaces in Shaping Leisure Jogging: Explainable Machine Learning Insights into Jogging Flow and Duration. Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 41, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongphromma, N. The Link Between PM2.5 Exposure and Cardiovascular Health Risks. Int. J. Sci. Healthc. Res. 2024, 9, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Social Determinants of Health Inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Corvalan, C.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Dynamics of the Double Burden of Malnutrition and the Changing Nutrition Reality. Lancet 2020, 395, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieck, C.J.; Sheon, A.; Ancker, J.; Castek, J.; Callahan, B.; Siefer, A. Digital Inclusion as a Social Determinant of Health. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, T.; Wang, H. Does Internet Use Affect Levels of Depression among Older Adults in China? A Propensity Score Matching Approach. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Yan, H.; Wang, X. Impact of Internet Use on Mental Health among Elderly Individuals: A Difference-in-Differences Study Based on 2016–2018 CFPS Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Du, M. How Digital Finance Shapes Residents’ Health: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 87, 102246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Y. The Impact of Digital Economy Development on Public Health: Evidence from Chinese Cities. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1347572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Mahumud, R.A.; Alam, F.; Keramat, S.A.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O.; Sarker, A.R. Determinants of Access to eHealth Services in Regional Australia. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2019, 131, 103960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.; Freeman, T.; Schram, A.; Baum, F.; Friel, S. Implementing Policy on Next-Generation Broadband Networks and Implications for Equity of Access to High Speed Broadband: A Case Study of Australia’s NBN. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Onega, T.; Moen, E.L.; Tosteson, A.N.A.; Smith, R.E.; Wang, Q.; Cowan, L.; Wang, F. Digital Divides in Telehealth Accessibility for Cancer Care in the United States. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, O.E.; Dang, P.; Fuentes, C.; Liaw, W. Examining the Affordable Connectivity Program and Telehealth Use: A Pilot Survey of the Affordable Connectivity Program, Telehealth, Video and Audio Visits in a Racially Diverse, Lower-Income Population. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Liu, G.; Chen, P.; Ke, K.; Xie, R. The Impact of Internet Development on Urban Eco-Efficiency—A Quasi-Natural Experiment of “Broadband China” Pilot Policy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaraweera, S.P.; Halgamuge, M.N. Internet of Things in the Healthcare Sector: Overview of Security and Privacy Issues. In Security, Privacy and Trust in the IoT Environment; Mahmood, Z., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 153–179. ISBN 978-3-030-18074-4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Fu, H. China’s Health Care System Reform: Progress and Prospects. Health Plan. Manag. 2017, 32, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, E.; L’Espérance, S.; Mosconi, E. Use of Social Media Platforms for Promoting Healthy Employee Lifestyles and Occupational Health and Safety Prevention: A Systematic Review. Saf. Sci. 2020, 131, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, G.; Persico, V.; Pescapé, A. Industry 4.0 and Health: Internet of Things, Big Data, and Cloud Computing for Healthcare 4.0. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 18, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, P.; Priya, S.; Manupati, V.; Varela, M.L.; Machado, J.M.; Putnik, G. Impact of UTAUT Predictors on the Intention and Usage of Electronic Health Records and Telemedicine from the Perspective of Clinical Staffs. In Innovation, Engineering and Entrepreneurship; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, M.; Bentahar, O. Digitalization of the Healthcare Supply Chain: A Roadmap to Generate Benefits and Effectively Support Healthcare Delivery. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 167, 120717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Sun, S.; Mukkamala, R.R.; Vatrapu, R.; Ordieres-Meré, J. Accelerating Health Data Sharing: A Solution Based on the Internet of Things and Distributed Ledger Technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e13583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Krumholz, H.M.; Yip, W.; Cheng, K.K.; De Maeseneer, J.; Meng, Q.; Mossialos, E.; Li, C.; Lu, J.; Su, M.; et al. Quality of Primary Health Care in China: Challenges and Recommendations. Lancet 2020, 395, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristea, M.; Noja, G.G.; Stefea, P.; Sala, A.L. The Impact of Population Aging and Public Health Support on EU Labor Markets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Pang, S.; Li, Z. Does Internet Development Affect Urban-Rural Income Gap in China? An Empirical Investigation at Provincial Level. Inf. Dev. 2023, 39, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitsch, B.; Gohl, D.; Von Lengerke, T. Re-Revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: A Systematic Review of Studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Soc.-Med. 2012, 9, Doc11. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh, N.; Rezayi, S.; Saeedi, S. Telemedicine for Patient Management in Remote Areas and Underserved Populations. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Khoury, A.; Subbaraman, R. The Promise and Peril of Universal Health Care. Science 2018, 361, eaat9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, J.; Ahmad, R.; Kiani, A.K.; Ahmad, T.; Saeed, S.; Almuhaideb, A.M. Data Protection and Privacy of the Internet of Healthcare Things (IoHTs). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.C.A.; De Bruin, V.M.S.; Das Chagas Medeiros, F.; Santana, J.A.P.; Lima, A.B.; De Francesco Daher, E. Health of Psychiatry Residents: Nutritional Status, Physical Activity, and Mental Health. Acad. Psychiatry 2016, 40, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Sonnega, A.; Bromet, E.; Hughes, M.; Nelson, C.B. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. In Fear and Anxiety; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.; Conley, D. Health Shocks and Social Drift: Examining the Relationship between Acute Illness and Family Wealth. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. The Stress of Life, Revised ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Soldan, A.; Oishi, K.; Faria, A.; Zhu, Y.; Albert, M.; Van Zijl, P.C.M.; Li, X. Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping of Brain Iron and β-Amyloid in MRI and PET Relating to Cognitive Performance in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. Radiology 2021, 298, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, L.L.; Brackins, T.; Rajaram, S. Episodic Memory Performance Modifies the Strength of the Age–Brain Structure Relationship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlechter, P.; Morina, N. The Associations among Well-being Comparisons and Affective Styles in Depression, Anxiety, and Mental Health Quality of Life. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 80, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Kiefer, R.; Kerr, S.; Balling, C. Reliability and Validity of a Self-Report Scale for Daily Assessments of the Severity of Anxiety Symptoms. Compr. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Sim, K.; Cui, X.; Lin, J.-X.; Ungvari, G.S.; Xiang, Y.-T. Reliability and Validity of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self-Report Scale in Older Adults with Depressive Symptoms. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 686711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, L.M.; Piran, M.J.; Han, D.; Min, K.; Moon, H. A Survey on Internet of Things and Cloud Computing for Healthcare. Electronics 2019, 8, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Berger, T.; Westermann, S.; Klein, J.P.; Moritz, S. Internet Interventions for Depression: New Developments. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 18, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nopiana, N.; Egie, J.; Mers, O. The Impact of Internet Addiction on Introvert Personality. World Psychol. 2022, 1, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-Y.; Chien, M.-S.; Lee, C.-C. ICT Diffusion, Financial Development, and Economic Growth: An International Cross-Country Analysis. Econ. Model. 2021, 94, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V.; Raghupathi, W. Healthcare Expenditure and Economic Performance: Insights from the United States Data. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Thompson, T.; McQueen, A.; Garg, R. Addressing Social Needs in Health Care Settings: Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities for Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, N.; Wong, S.W.; Ren, Y.; Shen, L. Regional Disparity in Urbanizing China: Empirical Study of Unbalanced Development Phenomenon of Towns in Southwest China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 5020013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Ran, Q.; Irfan, M.; Ren, S.; Yang, X.; Wu, H.; Ahmad, M. Analysis of the Mechanism of the Impact of Internet Development on Green Economic Growth: Evidence from 269 Prefecture Cities in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 9990–10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Factor Allocation, Economic Growth and Unbalanced Regional Development in China. World Econ. 2018, 41, 2439–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Zhou, X. Urban Administrative Hierarchy and Urban Land Use Efficiency: Evidence from Chinese Cities. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 88, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Zang, C.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, C. Can Information Infrastructure Development Improve the Health Care Environment? Evidence from China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 987391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-T.; Chen, L.; Yue, W.-W.; Xu, H.-X. Digital Technology-Based Telemedicine for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 646506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittari, G.; Savva, D.; Tomassoni, D.; Tayebati, S.K.; Amenta, F. Telemedicine in the COVID-19 Era: A Narrative Review Based on Current Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerjes, W.; Harding, D. Telemedicine in the Post-COVID Era: Balancing Accessibility, Equity, and Sustainability in Primary Healthcare. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1432871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Resident Health | Variables | Indicators | Description of Indicators | Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health | Health_physical | Acute shock | Acute shocks encompass conditions such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and so forth, with each occurrence of a specific ailment assigned one point. The cumulative count of distinct illnesses constitutes the score for acute shocks. The scoring range is [0, 3]. | Negative |

| Chronic shock | Chronic shocks comprise conditions such as hypertension, lipid abnormalities, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, liver diseases, kidney diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, arthritis, asthma, and so forth. Each instance of a specific condition is assigned one point, and the cumulative count of distinct ailments constitutes the score for chronic shocks. The scoring range is [0, 9]. | Negative | ||

| Mental health | Health_mental | Situational memory | Including short-term memory issues and delayed memory problems, the sum of the correct responses to these questions yields the situational memory score for the respondents. The scoring range is [0, 20]. | Positive |

| Mental cognition | Including calculations, inquiries about the date and season of the visit, graphic representations, and similar questions, the sum of correct responses to these queries yields the mental cognition score for the respondents. The scoring range is [0, 12]. | Positive | ||

| Depression self-assessment | Comprising 10 questions concerning the respondents’ feelings and behaviors in the previous week, participants choose from four options representing the frequency of occurrences. The sum of the scores associated with their selected options constitutes the depression self-assessment score. The scoring range is [10, 40]. | Negative |

| Variables | Variable Description | N | Mean | Min | Max | Std | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Health_physical | Physical health | 64,080 | 0.970 | 0.278 | 1.000 | 0.072 |

| Health_mental | Mental health | 64,080 | 0.469 | 0.059 | 1.000 | 0.148 | |

| Independent variable | BCP | Implementation of BCP | 64,080 | 0.194 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.396 |

| lnict | Information and communication technology level | 64,080 | 13.604 | 10.758 | 16.547 | 0.935 | |

| lnrgdp | Logarithmic values of GDP per capita | 64,080 | 10.595 | 8.842 | 13.056 | 0.591 | |

| lnha | Logarithmic values for healthcare providers | 64,080 | 9.981 | 8.201 | 12.010 | 0.636 | |

| Control variable | lnage | Logarithmic value of age | 64,080 | 4.093 | 3.807 | 4.771 | 0.162 |

| gender | Male = 1, female = 0 | 64,080 | 0.515 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.500 | |

| marital | Married = 1, otherwise = 0 | 64,080 | 0.867 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.340 | |

| residence | Rural = 1, urban = 0 | 64,080 | 0.128 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.334 | |

| lncost | Logarithmic value of hospitalization Costs | 64,080 | 1.034 | 0.000 | 14.152 | 2.803 | |

| toilet | No toilet = 0, otherwise = 1 | 64,080 | 0.788 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.409 | |

| water | No running water = 0, otherwise = 1 | 64,080 | 0.730 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.444 | |

| Variables | Health_Physical | Health_Mental | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| BCP | 0.023 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.017 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| lnage | −0.018 *** | 0.198 *** | ||

| (0.002) | (0.004) | |||

| gender | −0.003 *** | 0.053 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |||

| marital | −0.001 | −0.037 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| residence | −0.013 *** | −0.038 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| lncost | −0.002 *** | 0.002 *** | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| toilet | 0.001 | 0.015 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| water | 0.008 *** | 0.022 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| C | 0.966 *** | 1.042 *** | 0.465 *** | −0.419 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.008) | (0.001) | (0.019) | |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 |

| F | 608.866 | 139.069 | 143.575 | 777.521 |

| R2 | 0.024 | 0.036 | 0.061 | 0.168 |

| Variables | Acute Shock | Chronic Shock | Situational Memory | Mental Cognition | Depression Self-Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| BCP | −0.012 *** | −0.411 *** | 0.100 ** | 0.168 *** | 0.432 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.011) | (0.050) | (0.051) | (0.066) | |

| C | −0.438 *** | 0.555 *** | 37.787 *** | 70.950 *** | 23.822 *** |

| (0.030) | (0.093) | (0.531) | (2.070) | (0.720) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 |

| F | 91.528 | 222.904 | 836.781 | 171.381 | 207.284 |

| R2 | 0.031 | 0.039 | 0.166 | 0.694 | 0.065 |

| Variables | lnict | Health_ Physical | Health_ Mental | lnrgdp | Health_ Physical | Health_ Mental | lnma | Health_ Physical | Health_ Mental |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| BCP | 0.716 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.324 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.197 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.023 |

| (0.078) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.023) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.017) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| lnict | 0.021 *** | 0.017 *** | |||||||

| (0.001) | (0.001) | ||||||||

| lnrgdp | 0.071 *** | 0.031 *** | |||||||

| (0.002) | (0.003) | ||||||||

| lnha | 0.148 *** | 0.028 *** | |||||||

| (0.002) | (0.004) | ||||||||

| C | 13.464 *** | 0.779 *** | −0.633 *** | 10.532 *** | 0.324 *** | −0.734 *** | 9.942 *** | −0.395 *** | −0.150 *** |

| (0.015) | (0.013) | (0.023) | (0.005) | (0.018) | (0.033) | (0.003) | (0.025) | (0.041) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Obs | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 |

| F | 84.016 | 185.603 | 719.118 | 193.827 | 284.693 | 704.929 | 134.24 | 477.97 | 704.35 |

| R2 | 0.793 | 0.051 | 0.171 | 0.896 | 0.070 | 0.170 | 0.950 | 0.118 | 0.169 |

| Variables | Health_Physical | Health_Mental | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| lnphe | 0.047 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.046 *** | 0.027 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.003) | |

| BCP | 0.046 *** | 0.046 ** | ||

| (0.012) | (0.020) | |||

| lnphe × BCP | 0.005 *** | 0.006 *** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |||

| C | 0.538 *** | 0.677 *** | 0.039 | −0.654 *** |

| (0.074) | (0.018) | (0.079) | (0.032) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 |

| F | 33.659 | 146.833 | 29.715 | 630.247 |

| R2 | 0.031 | 0.046 | 0.063 | 0.170 |

| Variables | Gender | Residence | Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health_ Physical | Health_ Mental | Health_ Physical | Health_ Mental | Health_ Physical | Health_ Mental | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| BCP | 0.021 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.013 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| BCP × gender | 0.002 ** | −0.003 | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.003) | |||||

| BCP × residence | 0.015 *** | −0.004 | ||||

| (0.002) | (0.004) | |||||

| BCP × age | 0.001 | 0.010 *** | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.003) | |||||

| C | 1.043 *** | −0.420 *** | 1.043 *** | −0.419 *** | 1.041 *** | −0.440 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.019) | (0.008) | (0.019) | (0.009) | (0.019) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 | 64,080 |

| F | 123.611 | 692.186 | 124.718 | 691.735 | 128.543 | 695.521 |

| R2 | 0.036 | 0.169 | 0.037 | 0.169 | 0.036 | 0.169 |

| Variables | Health_Physical | Health_Mental | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Region | Central Region | Western Region | Eastern Region | Central Region | Western Region | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| BCP | 0.024 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.029 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| BdiffE (Eastern | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | ||||

| vs. Non-Eastern) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| BdiffW (Western | −0.001 *** | −0.016 *** | ||||

| vs. Non-Western) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| C | 1.051 *** | 1.045 *** | 1.024 *** | −0.423 *** | −0.454 *** | −0.380 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.030) | (0.032) | (0.035) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 24,020 | 22,034 | 18,026 | 24,020 | 22,034 | 18,026 |

| F | 50.322 | 49.449 | 48.400 | 270.765 | 266.634 | 248.421 |

| R2 | 0.036 | 0.033 | 0.039 | 0.144 | 0.159 | 0.186 |

| Variables | Health_Physical | Health_Mental | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Ordinary Prefecture-Level Cities | Ordinary Prefecture-Level Cities | Non-Ordinary Prefecture-Level Cities | Ordinary Prefecture-Level Cities | |

| (1) | (2) | (4) | (5) | |

| BCP | 0.035 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.017 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| Bdiff | −0.015 *** | −0.003 *** | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| C | 1.060 *** | 1.037 *** | −0.329 *** | −0.437 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.009) | (0.044) | (0.021) | |

| Control | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 11,448 | 52,632 | 11,448 | 52,632 |

| F | 59.313 | 83.443 | 89.695 | 715.241 |

| R2 | 0.073 | 0.029 | 0.122 | 0.179 |

| Variables | Nearest Neighbor Matching (n = 1) | Radius Matching (r = 0.03) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health_Physical | Health_Mental | Health_Physical | Health_Mental | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| BCP | 0.025 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.018 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.007) | |

| lnage | −0.022 *** | 0.215 *** | −0.014 *** | 0.210 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.008) | |

| gender | −0.002 *** | 0.051 *** | −0.001 | 0.049 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.003) | |

| marital | −0.001 | −0.034 *** | 0.001 | −0.036 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.004) | |

| residence | −0.013 *** | −0.037 *** | −0.005 *** | −0.040 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.004) | |

| lncost | −0.002 *** | 0.001 *** | −0.002 *** | 0.001 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| toilet | 0.003 ** | 0.016 *** | −0.001 | 0.019 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.004) | |

| water | 0.006 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.002 | 0.024 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| C | 1.051 *** | −0.495 *** | 1.013 *** | −0.475 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.028) | (0.015) | (0.037) | |

| City FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observation | 27,944 | 27,944 | 14,232 | 14,232 |

| F | 105.182 | 372.954 | 23.579 | 201.236 |

| R2 | 0.052 | 0.177 | 0.066 | 0.188 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| BCP | 0.555 *** | 0.516 *** |

| (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| lnage | −0.284 *** | |

| (0.037) | ||

| gender | −0.171 *** | |

| (0.011) | ||

| marital | −0.060 *** | |

| (0.018) | ||

| residence | 0.280 *** | |

| (0.017) | ||

| lncost | −0.051 *** | |

| (0.002) | ||

| toilet | 0.078 *** | |

| (0.013) | ||

| water | 0.179 *** | |

| (0.013) | ||

| C | 1.698 *** | 3.003 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.159) | |

| City FE | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y |

| Observation | 64,080 | 64,080 |

| F | 1494.992 | 413.237 |

| R2 | 0.050 | 0.080 |

| Variables | Health_Physical | Health_Mental |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| BCP | 0.003 *** | 0.015 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| lnage | −0.025 *** | 0.196 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.004) | |

| gender | −0.003 *** | 0.052 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| marital | −0.001 | −0.038 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| residence | −0.015 *** | −0.048 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| lncost | −0.002 *** | 0.002 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| toilet | 0.000 | 0.011 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| water | 0.003 *** | 0.015 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| ict | −0.001 | 0.003 ** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| is | 0.001 | 0.017 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| gov | −0.557 *** | −0.232 *** |

| (0.058) | (0.084) | |

| lnrgdp | 0.076 *** | −0.023 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| C | 0.292 *** | −0.206 *** |

| (0.019) | (0.027) | |

| City FE | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y |

| Observation | 64,080 | 64,080 |

| F | 223.889 | 540.479 |

| R2 | 0.071 | 0.147 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Yu, C.; Han, Z. Can Urban Information Infrastructure Development Improve Resident Health? Evidence from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120496

Zhao H, Yu C, Han Z. Can Urban Information Infrastructure Development Improve Resident Health? Evidence from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120496

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Huiling, Chenyang Yu, and Zhanchuang Han. 2025. "Can Urban Information Infrastructure Development Improve Resident Health? Evidence from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120496

APA StyleZhao, H., Yu, C., & Han, Z. (2025). Can Urban Information Infrastructure Development Improve Resident Health? Evidence from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120496