A Semantic Collaborative Filtering-Based Recommendation System to Enhance Geospatial Data Discovery in Geoportals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Recommender-System Categories

2.2. Semantic and Ontology-Based Recommenders

2.3. Collaborative Filtering Recommendation System in Geoportals

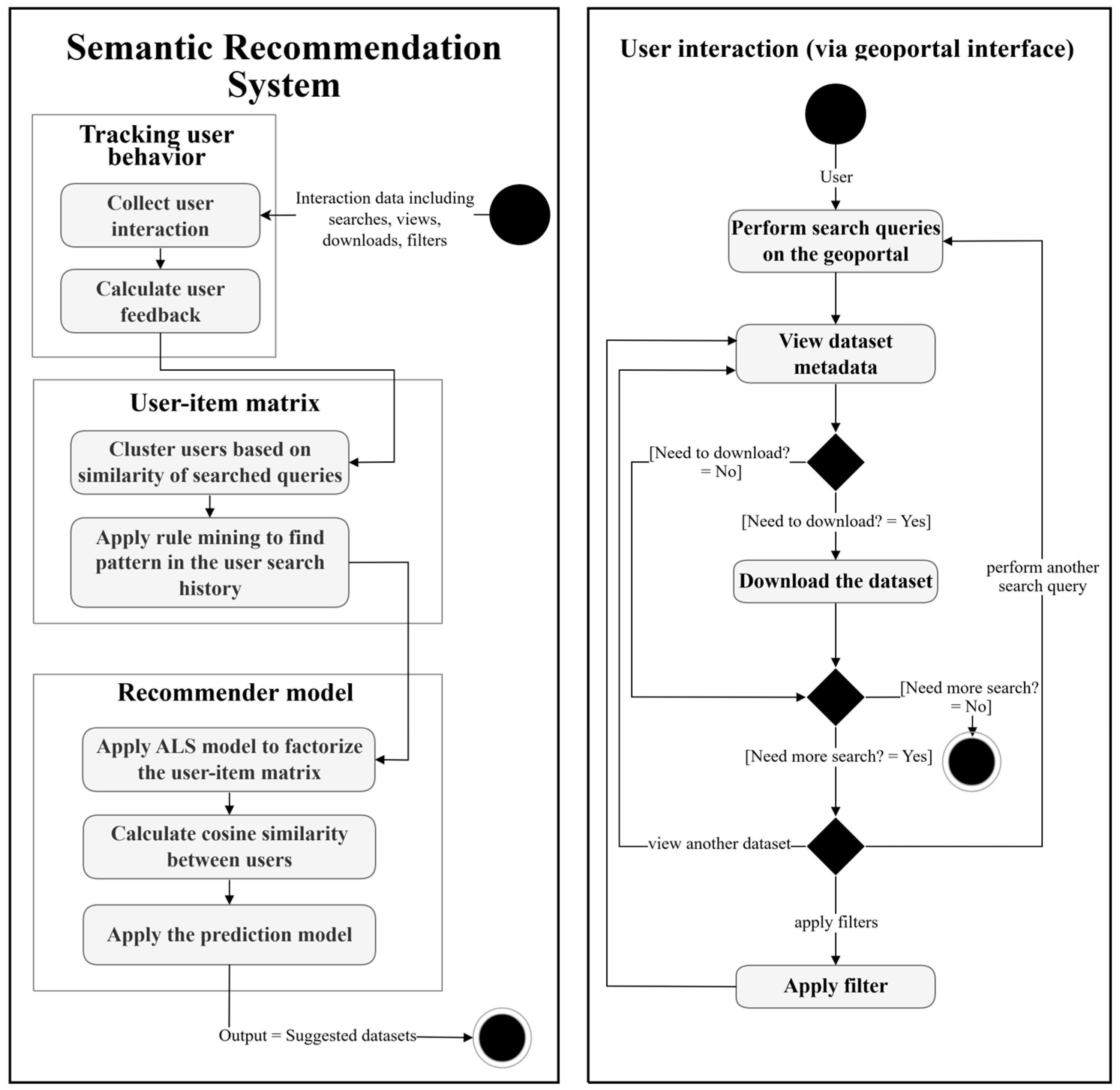

3. Methodology

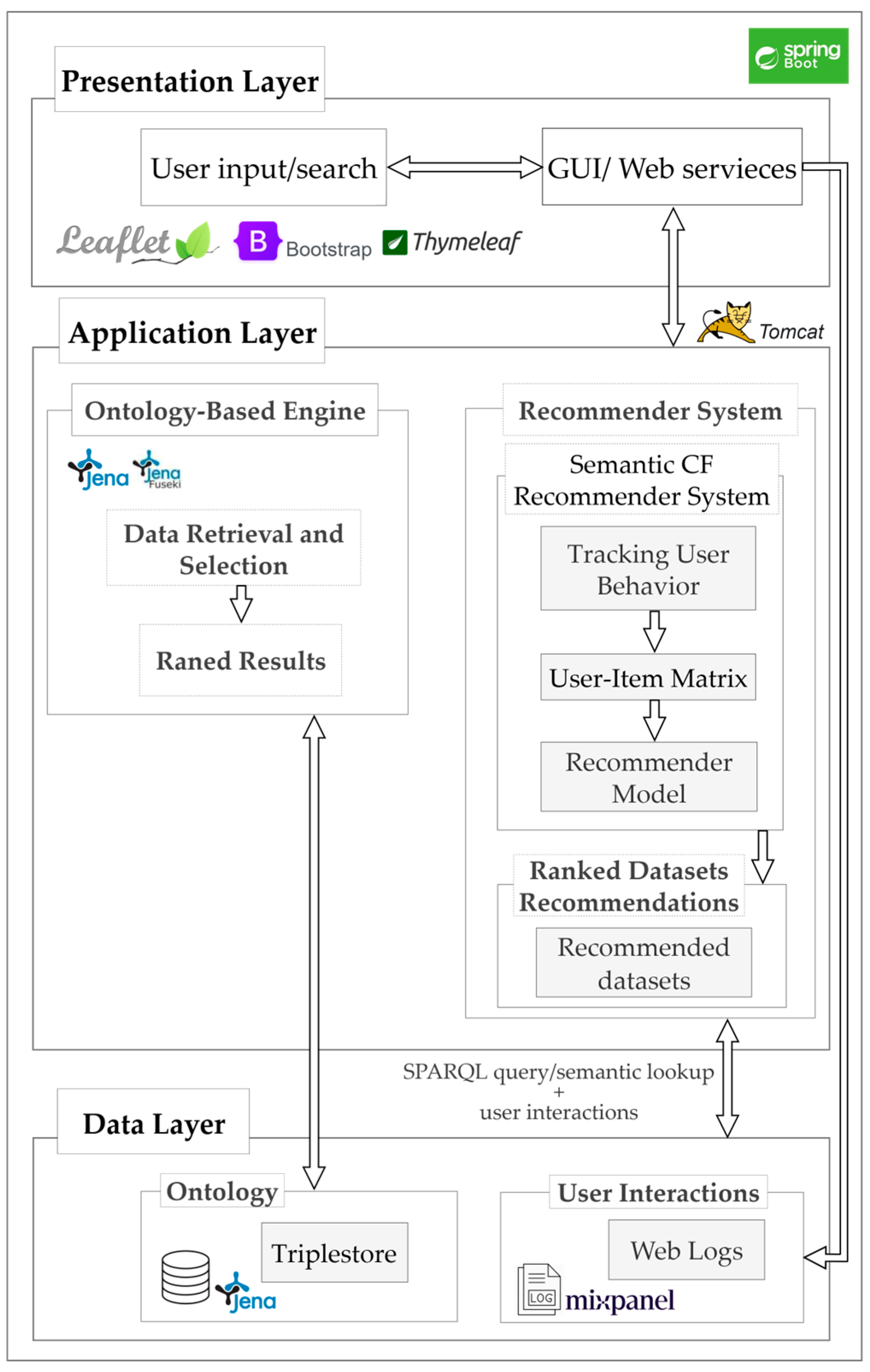

3.1. Framework Overview

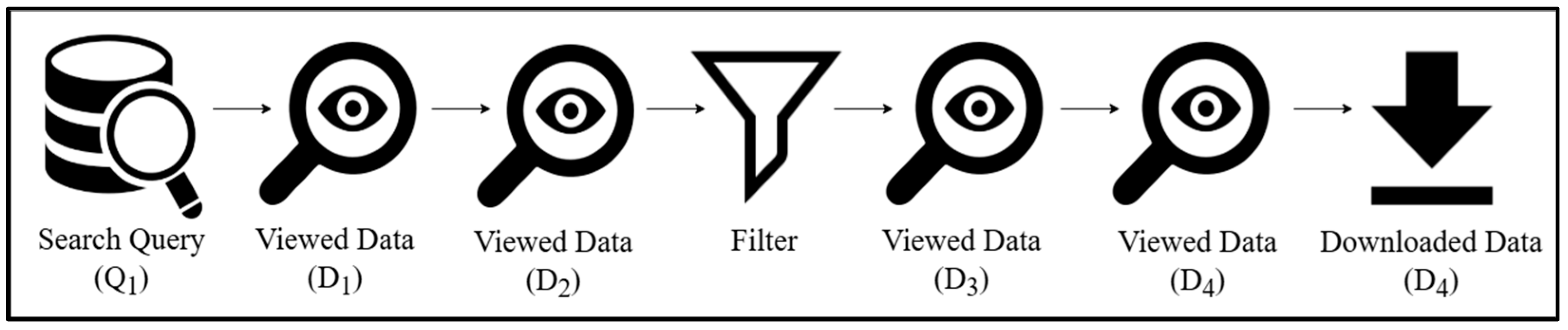

3.2. Tracking User Behavior

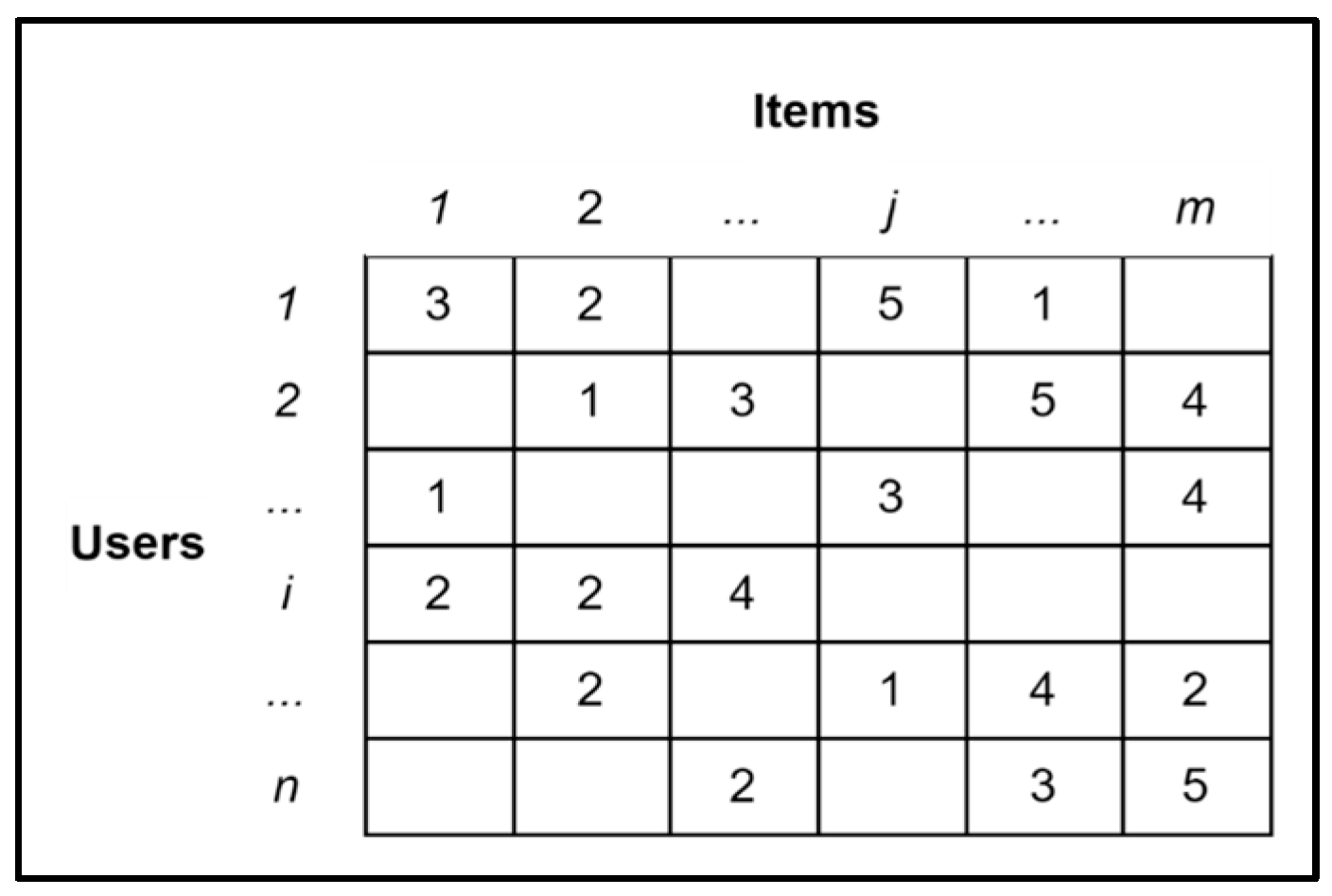

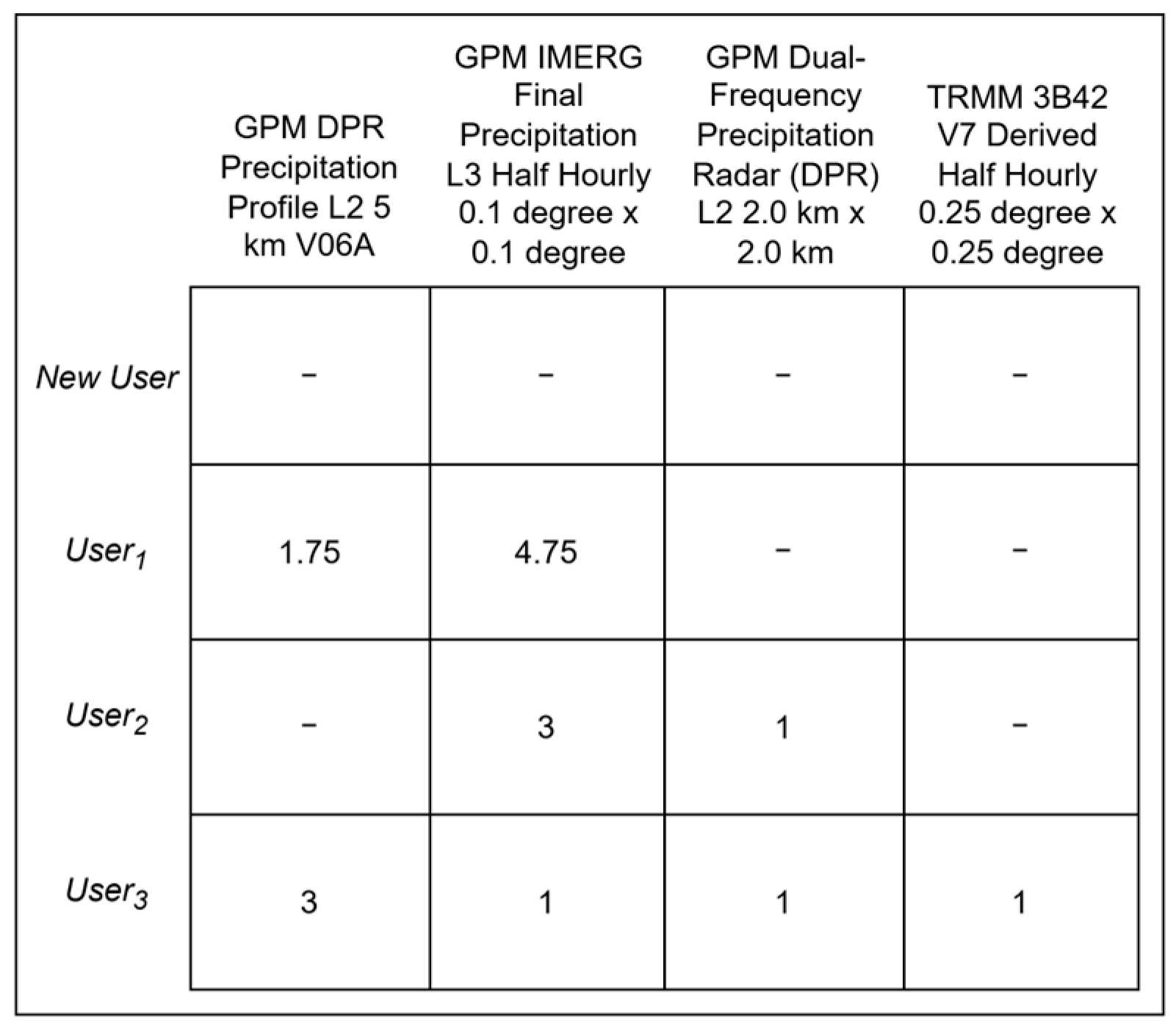

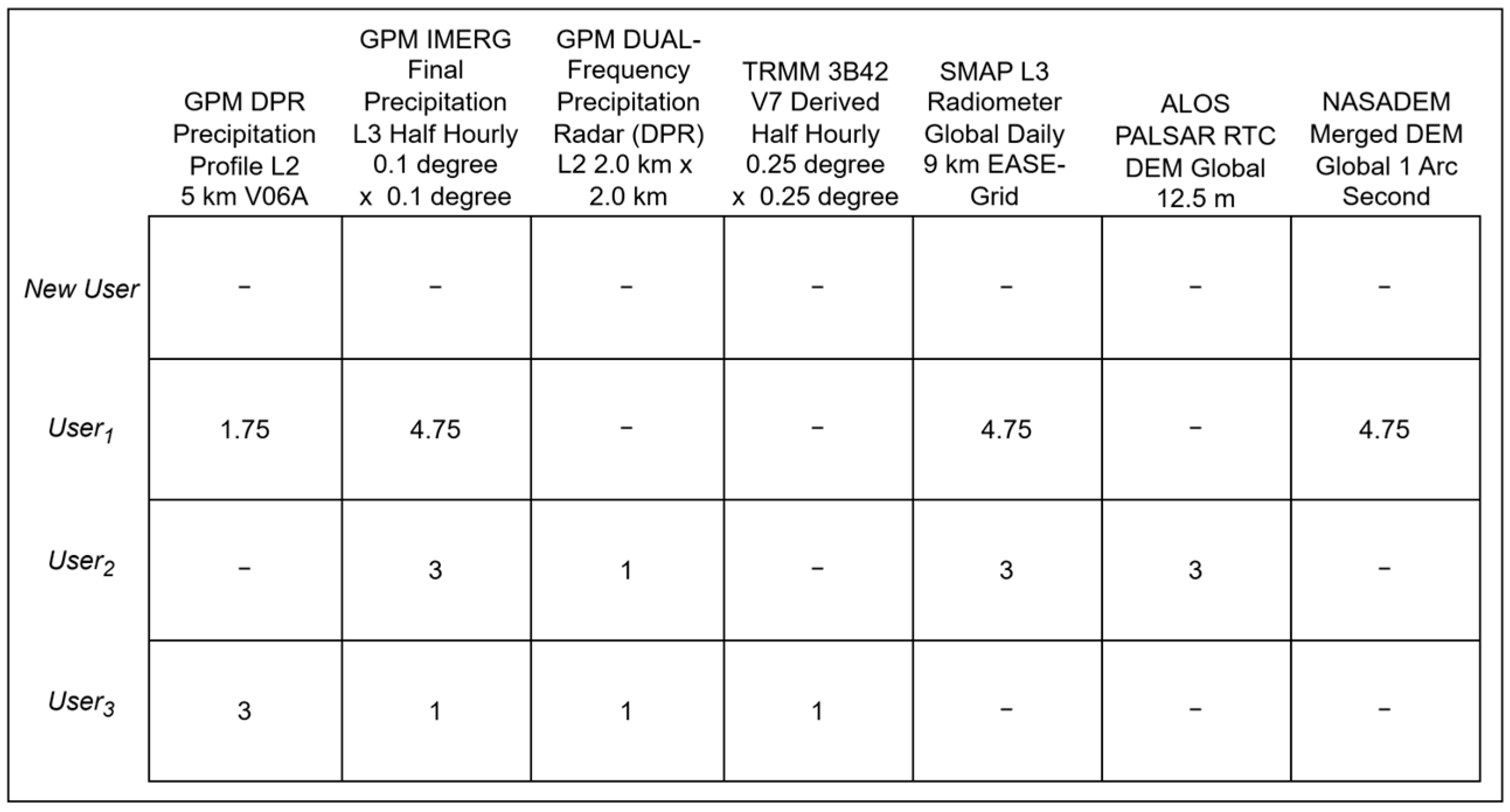

3.3. User–Item Matrix

- (a)

- Semantic User Clustering

- Precipitation > Precipitation Amount > 3 h Precipitation Amount.

- Precipitation > Precipitation Amount > 6 h Precipitation Amount.

- Precipitation > Precipitation Amount > 12 h Precipitation Amount.

- (b)

- Search Query Rule Mining

3.4. Recommender Model

- (a)

- Alternating Least Squares (ALS) and Cosine similarity

- is the actual interaction (such as rating) of user u with item i.

- is the latent factor vector for user u.

- is the latent factor vector for item i.

- K is the set of (user, item) pairs for which is known.

- λ is the regularization parameter.

- and are the L2 norms of the user and item factor vectors, respectively, used for regularization.

- (b)

- Prediction model

4. Testing the Quality of the Recommender System

4.1. System Architecture

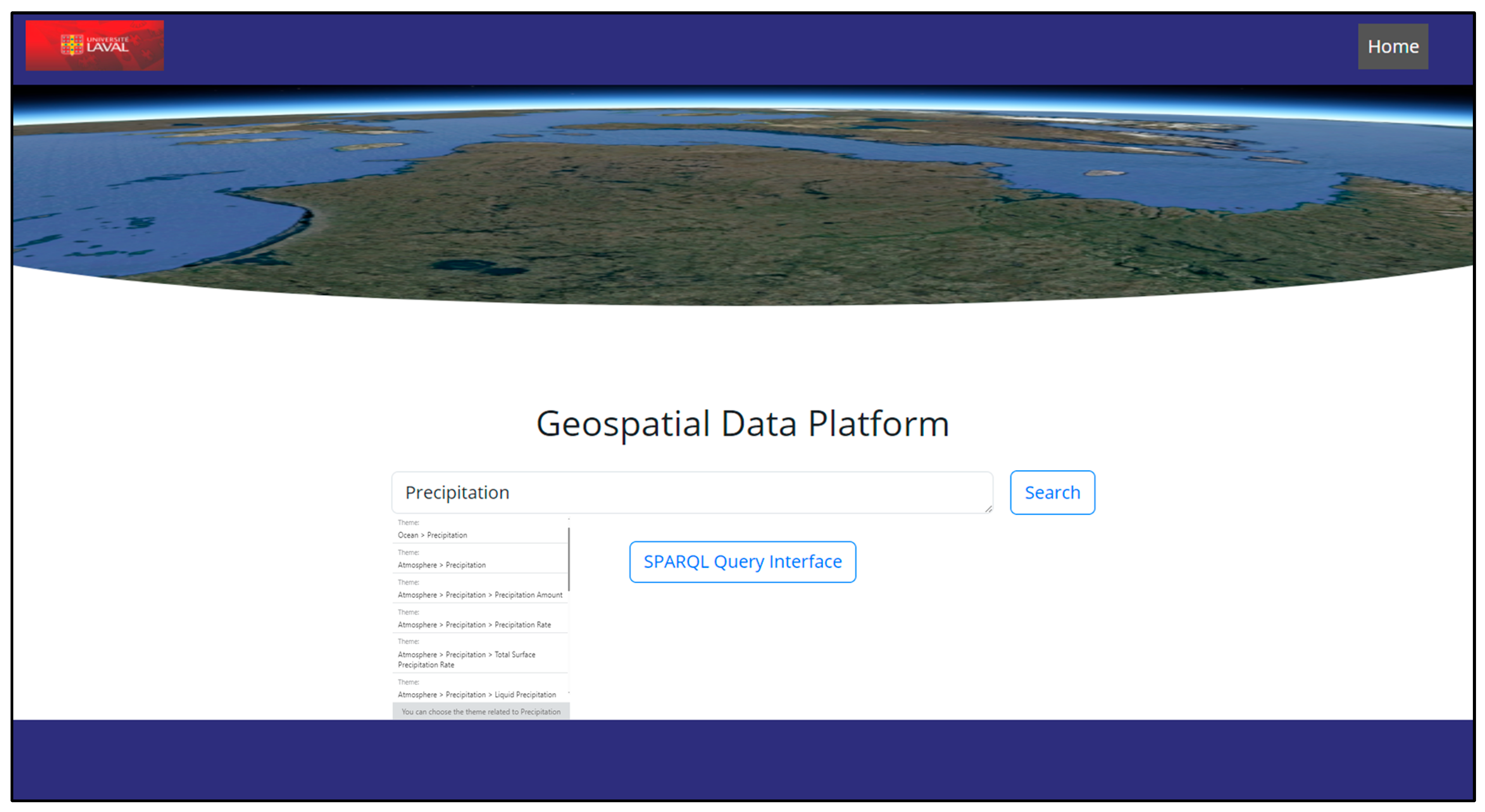

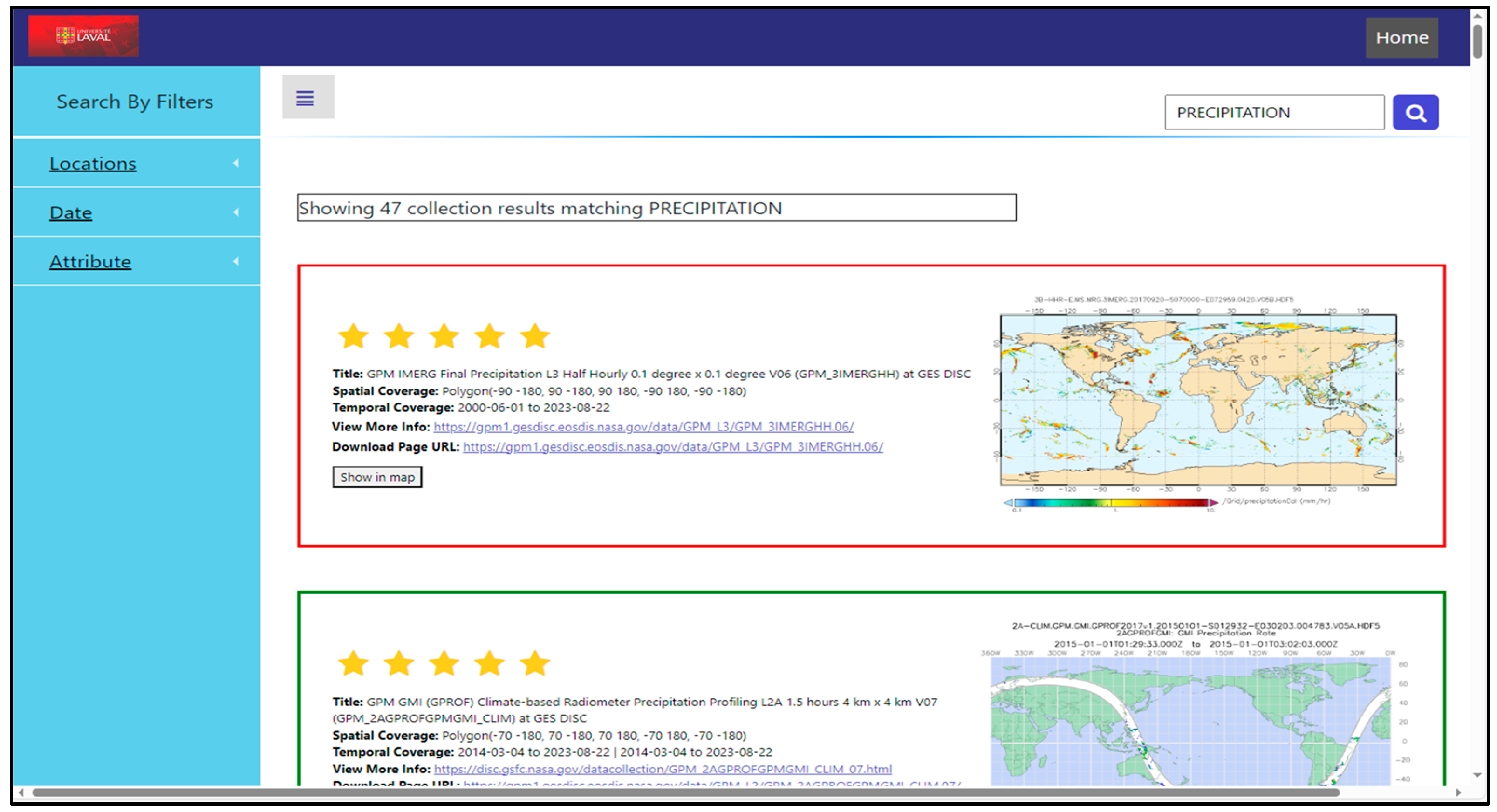

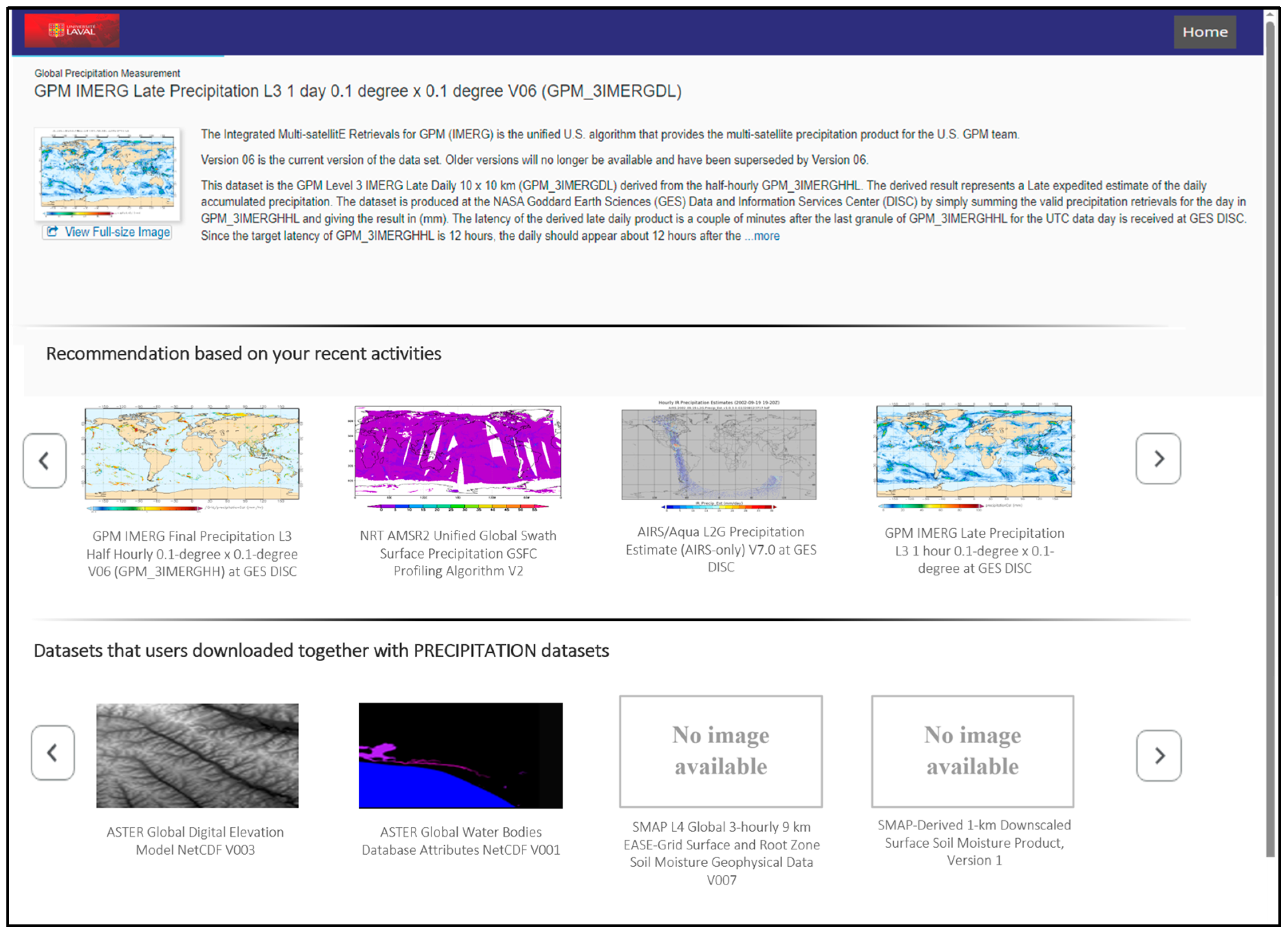

4.2. Interface and Recommendation Display

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

- True Positives (TP): The number of items correctly identified as relevant by the system, where “true” refers to items that are genuinely relevant to the user’s query or needs, based on ground truth data or expert validation.

- False Positives (FP): The number of items incorrectly identified as relevant.

- False Negatives (FN): The number of relevant items that the system failed to identify.

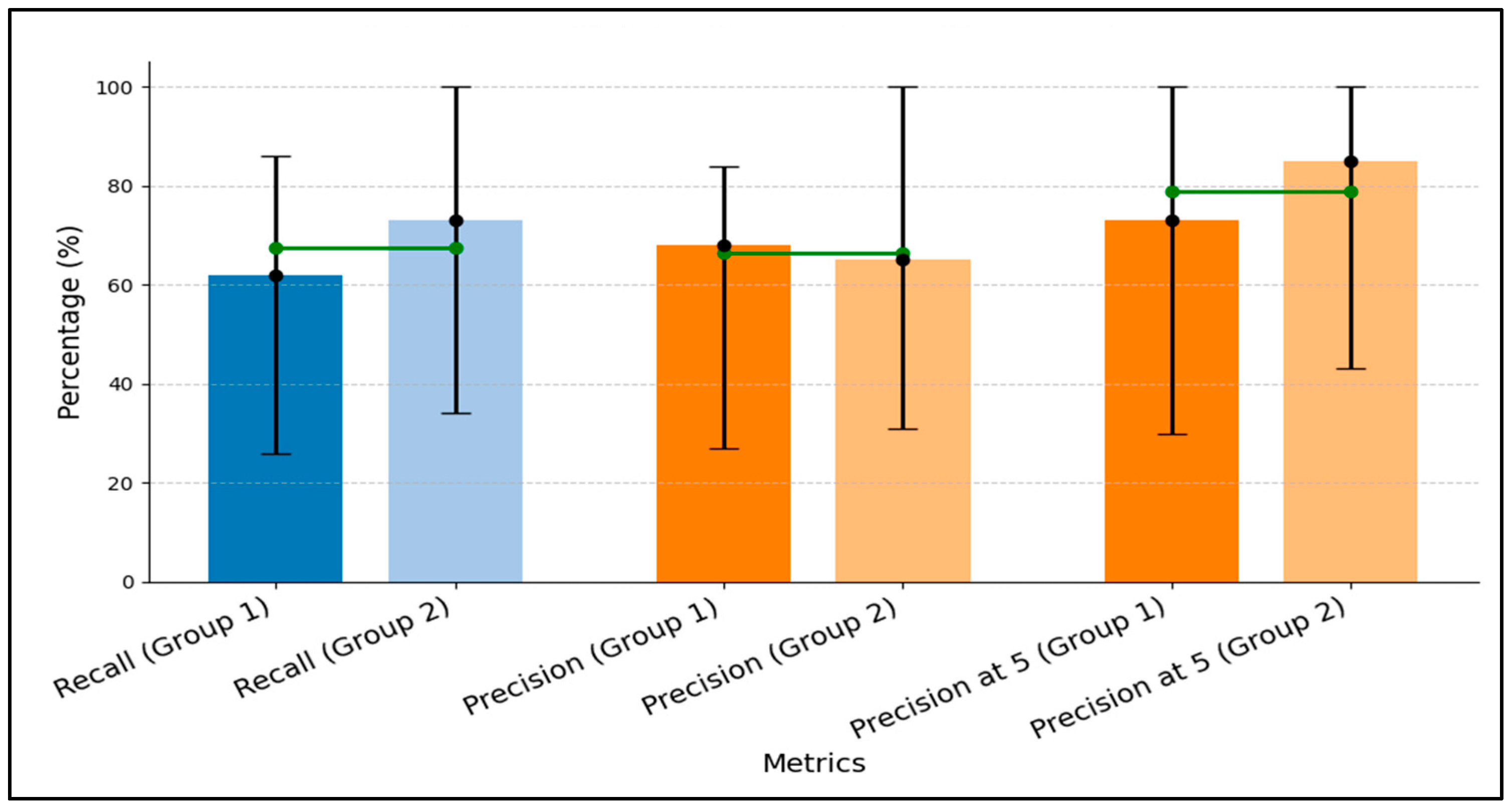

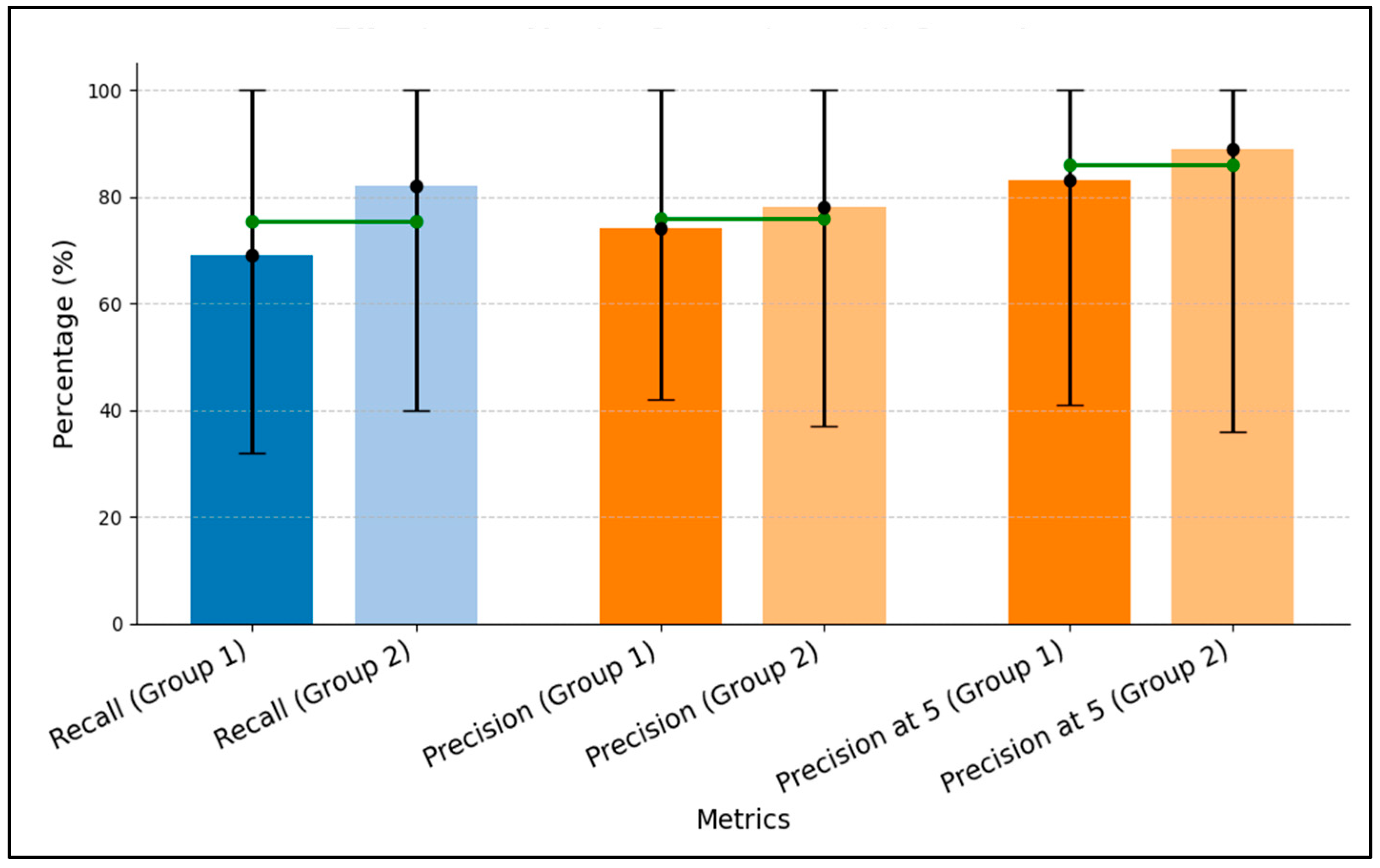

4.4. Experiment Results

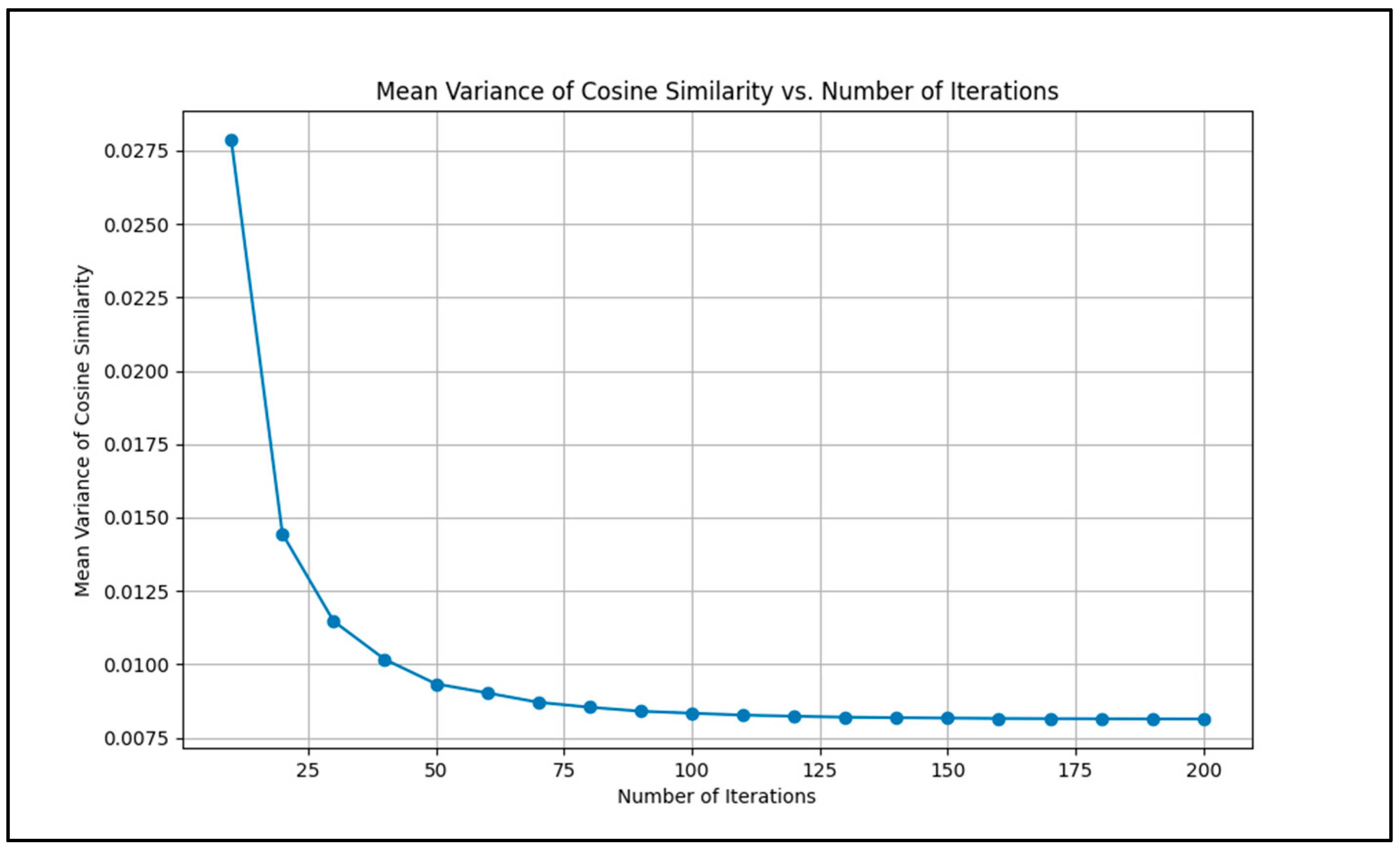

4.5. Optimizing the Parameters of the Recommendation System

4.6. Finding the Best Iteration for Training the ALS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sambasivan, N.; Arriaga, R.I.; Prabhakar, A.; Kamar, E.; Chayes, J. Everyone wants to do the model work, not the data work. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference Human Factors Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brickley, D.; Burgess, M.; Noy, N. Google Dataset Search: Building a search engine for datasets in an open web ecosystem. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 1365–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Stall, S.; Robinson, E.; Wyborn, L.; Yarmey, L.R.; Parsons, M.A.; Lehnert, K.; Cutcher-Gershenfeld, J.; Nosek, B.; Hanson, B. Enabling FAIR Data Across the Earth and Space Sciences. Eos 2017, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stall, S.; Cruse, P.; Cousijn, H.; Cutcher-Gershenfeld, J.; de Waard, A.; Hanson, B.; Heber, J.; Lehnert, K.; Parsons, M.; Robinson, E.; et al. Data sharing and citations: New author guidelines promoting open and FAIR data in the Earth, space, and environmental sciences. Sci. Ed. 2018, 41, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loenen, B.; Grothe, M.J.M. INSPIRE Empowers Re-Use of Public Sector Information. Int. J. Spat. Data Infrastruct. Res. 2014, 9, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Simperl, E.; Koesten, L.; Konstantinidis, G.; Ibáñez, L.-D.; Kacprzak, E.; Groth, P. Dataset search: A survey. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2020, 35, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nativi, S.; Mazzetti, P.; Santoro, M.; Papeschi, F.; Craglia, M.; Ochiai, O. Big Data challenges in building the Global Earth Observation System of Systems. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 68, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.C.; Mayernik, M.S.; Ramapriyan, H.K. Identifiers for Earth Science Data Sets: Where We Have Been and Where We Need to Go. Data Sci. J. 2017, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration. NASA Homepage. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. Environment and Climate Change Canada Homepage. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change.html (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- European Space Agency. ESA Homepage. Available online: https://www.esa.int/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Geoscience Australia. Digital Earth Australia—Open Data Cube. Available online: https://www.dea.ga.gov.au/about/open-data-cube (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Gao, F.; Yue, P.; Cao, Z.; Zhao, S.; Shangguan, B.; Jiang, L.; Hu, L.; Fang, Z.; Liang, Z. A Multi-Source Spatio-Temporal Data Cube for Large-Scale Geospatial Analysis. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2022, 36, 1853–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoCube Portal. Available online: http://www.openearth.org.cn/en-US (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- ISO 19115-1:2014; Geographic Information—Metadata—Part 1: Fundamentals. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 19115-2:2019; Geographic Information—Metadata—Part 2: Extensions for Acquisition and Processing. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management. Future Trends in Geospatial Information Management: The Five to Ten Year Vision; United Nations: London, UK, 2013.

- Quarati, A.; De Martino, M.; Rosim, S. Geospatial Open Data Usage and Metadata Quality. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumaier, S.; Umbrich, J.; Polleres, A. Automated Quality Assessment of Metadata across Open Data Portals. J. Data Inf. Qual. 2016, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W3C; OGC. Spatial Data on the Web Best Practices; W3C Working Group Note and OGC Best Practice. 28 September 2017. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/sdw-bp/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Hu, F.; Armstrong, E.M.; Huang, T.; Moroni, D.; McGibbney, L.J.; Greguska, F.; Finch, C.J. A smart web-based geospatial data discovery system with oceanographic data as an example. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, E.; Koesten, L.; Ibáñez, L.-D.; Blount, T.; Tennison, J.; Simperl, E. Characterising dataset search—An analysis of search logs and data requests. J. Web Semant. 2019, 55, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vockner, B.; Mittlböck, M. Geo-enrichment and semantic enhancement of metadata sets to augment discovery in geoportals. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2014, 3, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, G.; Janowicz, K.; Prasad, S.; Shi, M.; Cai, L.; Zhu, R.; Regalia, B.; Lao, N. Semantically-enriched search engine for geoportals: A case study with ArcGIS Online. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.06561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, Q.; Du, Z.; Chen, X.; Cao, C. A comprehensive overview of RDF for spatial and spatiotemporal data management. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2021, 36, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasis, N.; Kalabokidis, K.; Vaitis, M.; Soulakellis, N. Towards a semantics-based approach in the development of geographic portals. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, J.; Müller, K.; Hellmann, S.; Rahm, E.; Vidal, M.E. Evaluation of metadata representations in RDF stores. Semant. Web 2019, 10, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F.; Rokach, L.; Shapira, B. Introduction to recommender systems handbook. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Ricci, F., Rokach, L., Shapira, B., Kantor, P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, C.C. Recommender Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zabala, A.; Masó, J.; Bastin, L.; Giuliani, G.; Pons, X. Geospatial User Feedback: How to Raise Users’ Voices and Collectively Build Knowledge at the Same Time. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaimatin, H.; Nili, A.; Barros, A. Reducing Consumer Uncertainty: Towards an Ontology for Geospatial User-Centric Metadata. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dareshiri, S.; Farnaghi, M.; Sahelgozin, M. A recommender geoportal for geospatial resource discovery and recommendation. J. Spat. Sci. 2019, 64, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vockner, B.; Belgiu, M.; Mittlböck, M. Recommender-based enhancement of discovery in geoportals. Int. J. Spat. Data Infrastruct. Res. 2012, 7, 441–463. [Google Scholar]

- NASA EOSDIS. American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) Reports for NASA Earth Science Data Systems. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/eosdis/system-performance/acsi-reports (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Copernicus Land Monitoring Service (CLMS) Annual Feedback Surveys, 2020–2024. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- European Space Agency. Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (CDSE) User Satisfaction Survey 2025. Available online: https://remotesensing.vito.be/news/cdse-user-satisfaction-survey-2025 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Adomavicius, G.; Tuzhilin, A. Toward the next generation of recommender systems: A survey of the state of the art and possible extensions. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2005, 17, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. Hybrid recommender systems: Survey and experiments. User Model. User-Adap. Interact. 2002, 12, 331–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, A. A New Approach to Enhance Geospatial Data Selection in Geoportals: Application for Supporting Natural Hazard Early Warning System in Nunavik, Québec. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jannach, D.; Zanker, M.; Felfernig, A.; Friedrich, G. Recommender Systems: An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lops, P.; de Gemmis, M.; Semeraro, G. Content-Based Recommender Systems: State of the Art and Trends. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Ricci, F., Rokach, L., Shapira, B., Kantor, P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R. Knowledge-Based Recommender Systems. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science; Kent, A., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 69, pp. 180–200. [Google Scholar]

- Felfernig, A.; Burke, R. Constraint-Based Recommender Systems: Technologies and Research Issues. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Electronic Commerce (ICEC ’08), Innsbruck, Austria, 19–22 August 2008; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueras-Iso, J.; Lacasta, J.; Ureña-Cámara, M.A.; Ariza-López, F.J. Quality of Metadata in Open Data Portals. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 60364–60382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.; Bechhofer, S. SKOS Simple Knowledge Organization System Reference; W3C Recommendation. 18 August 2009. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, C.; Yu, M.; Kamal, L.; Armstrong, E.M.; Huang, T.; Moroni, D.; McGibbney, L.J. Improving search ranking of geospatial data based on deep learning using user behavior data. Comput. Geosci. 2020, 142, 104520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Olmo, F.H.; Gaudioso, E. Evaluation of recommender systems: A new approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2008, 35, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.I.M.; Majeed, S.S. A review of collaborative filtering recommendation system. MJPS 2021, 8, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.A.; Philips, J.; Tabrizi, N. Current trends in collaborative filtering recommendation systems. In SERVICES 2019: 15th World Congress on Services; Proceedings of the SCF 2019, San Diego, CA, USA, 25–30 June 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fkih, F. Similarity measures for collaborative filtering-based recommender systems: Review and experimental comparison. J. King Saud Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 7645–7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganeshwari, G.; Syed Ibrahim, S.P. A survey on collaborative filtering based recommendation system. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Big Data and Cloud Computing Challenges, Vellur, India, 10–11 March 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Y. Collaborative filtering with temporal dynamics. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Paris, France, 28 June–1 July 2009; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yao, L.; Sun, A.; Tay, Y. Deep learning based recommender system: A survey and new perspectives. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobadilla, J.; Alonso, S.; Hernando, A. Deep learning architecture for collaborative filtering recommender systems. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, R.; He, R.; Chen, K.; Eksombatchai, P.; Hamilton, W.L.; Leskovec, J. Graph convolutional neural networks for web-scale recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 974–983. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, B.; Rokach, L.; Ricci, F. (Eds.) Recommender Systems Handbook, 3rd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Albertoni, R.; De Martino, M.; Podestà, P.; Abecker, A.; Wössner, R.; Schnitter, K. LusTRE: A framework of linked environmental thesauri for metadata management. Earth Sci. Inform. 2018, 11, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecker, A.; Schnitter, K.; Wössner, R.; Albertoni, R.; De Martino, M.; Podestà, P. Latest Developments of the Linked Thesaurus Framework for the Environment (LusTRE). In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Informatics for Environmental Protection & 3rd International Conference on ICT for Sustainability (EnviroInfo/ICT4S 2015), Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–9 September 2015; pp. 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats-Coll, I.; Kolshus, K.; Turbati, A.; Stellato, A.; Mietzsch, E.; Martini, D.; Zeng, M. AGROVOC: The linked data concept hub for food and agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 105965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenige, L.; Ruhland, J. SKOS-Based Concept Expansion for LOD-Enabled Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Metadata and Semantics Research (MTSR 2018), Limassol, Cyprus, 23–26 October 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, P.; Onsjö, M.; Becerra, C.; Jimenez, S.; Dueñas, G. An Ontology-Based Recommender System with an Application to the Star Trek Television Franchise. Future Internet 2019, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasingha, R.A.H.M.; Paik, I. Alleviating Sparsity by Specificity-Aware Ontology-Based Clustering for Improving Web Service Recommendation. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2019, 14, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard, K.; Rahmani, M.; Nilashi, M.; Rafe, V. Performance Improvement for Recommender Systems Using Ontology. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1772–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, F.; Likavec, S.; Osborne, F. Anisotropic Propagation of User Interests in Ontology-Based User Models. Inf. Sci. 2013, 250, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantador, I.; Castells, P.; Bellogín, A. An Enhanced Semantic Layer for Hybrid Recommender Systems: Application to News Recommendation. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. 2011, 7, 44–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vockner, B.; Richter, A.; Mittlböck, M. From geoportals to geographic knowledge portals. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2013, 2, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, K.; Armstrong, E.M.; Huang, T.; Moroni, D.; Finch, C. A comprehensive methodology for discovering semantic relationships among geospatial vocabularies using oceanographic data discovery as an example. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 2310–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, C.; Fan, L.; Kwan, M.-P. An OGC Web Service Geospatial Data Semantic Similarity Model for Improving Geospatial Service Discovery. Open Geosciences 2021, 13, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Yoo, D.; Kim, G.; Suh, Y. A hybrid online-product recommendation system: Combining implicit rating-based collaborative filtering and sequential pattern analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Cho, Y.H.; Kim, S.H. Collaborative filtering with ordinal scale-based implicit ratings for mobile music recommendations. Inf. Sci. 2010, 180, 2142–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekouar, L.; Iraqi, Y.; Damaj, I. A global user profile framework for effective recommender systems. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 50711–50731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrzadeh, Z.; Feizi-Derakhshi, M.R.; Balafar, M.A.; Mohasefi, J.B. Knowledge graph-based recommendation system enhanced by neural collaborative filtering and knowledge graph embedding. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djidjev, H.N.; Pantziou, G.E.; Zaroliagis, C.D. Computing shortest paths and distances in planar graphs. In Proceedings of the 18th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages and Programming, Madrid, Spain, 8–12 July 1991; pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- W3C. OWL Web Ontology Language Guide; W3C Recommendation. 2004. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-owl-guide-20040210 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- W3C. OWL 2 Web Ontology Language—Document Overview; W3C Recommendation. 2012. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/owl2-overview (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Global Change Master Directory (GCMD). GCMD Keywords, Version 22.5. Available online: https://forum.earthdata.nasa.gov/app.php/tag/GCMD+Keywords (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Li, W. Lowering the barriers for accessing distributed geospatial big data to advance spatial data science: The PolarHub solution. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2018, 108, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, A.; Badard, T.; Pouliot, J. Development of an ontology-based framework to enhance geospatial data discovery and selection in geoportals for natural-hazard early warning systems. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, Z.; Ebrahimian, M.; Nawara, D.; Ibrahim, A.; Kashef, R. Recommendation systems: Algorithms, challenges, metrics, and business opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, G.; Gunawardana, A. Evaluating recommendation systems. In Recommender Systems Handbook; Ricci, F., Rokach, L., Shapira, B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 257–297. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, T.; Zhang, M.; Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, S. How good is your recommender system? A survey on evaluations in recommendation. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2019, 10, 813–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlocker, J.L.; Konstan, J.A.; Terveen, L.G.; Riedl, J.T. Evaluating collaborative filtering recommender systems. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2004, 22, 5–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recommendation Category | Core Principle and Input Signals | Main Strengths | Main Challenges | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative filtering | Learns latent user and item factors from user–item interaction data (e.g., ratings, clicks, views, downloads), assuming that users with similar interaction histories tend to prefer similar items. | Domain-independent; does not require detailed item metadata; can exploit implicit feedback; captures cross-thematic usage patterns (e.g., datasets frequently used together in workflows) that are difficult to express in metadata. | Requires sufficient interaction logs; suffers from cold-start for new users and new items; performance degrades under extreme sparsity; may over-emphasize popular items and is often less interpretable. | [28,37,40] |

| Content-based | Compares item feature descriptions (textual keywords, structured attributes, embeddings) to a profile of user interests constructed from items previously accepted or used by that user. | Can operate with a single user; well suited to recommending new or long-tail items when their descriptors are available; recommendations can be more interpretable because they are grounded in item characteristics. | Strongly dependent on the completeness, consistency, and quality of item metadata; prone to overspecialization (recommending only very similar items); limited ability to exploit collective usage patterns across users. | [37,40,41] |

| Knowledge-based | Uses explicit domain knowledge (rules, constraints, cases) to match user requirements to items; recommendations are derived from means–end reasoning rather than from past user ratings or logs. | No ramp-up problem (does not require historical interactions); suitable for infrequent, high-impact, or technically complex choices; supports interactive, constraint-driven recommendation and transparent justification. | Requires substantial effort to elicit, encode, and maintain domain knowledge; rule bases may become large and difficult to manage; can be rigid or outdated if knowledge is not regularly revised as data offerings and user needs evolve. | [40,42,43] |

| Hybrid | Combines two or more of the above paradigms (e.g., collaborative + content-based, or collaborative + knowledge-based) by weighting, switching, cascading, or feature-level integration. | Can exploit complementary strengths (e.g., use metadata to mitigate cold-start in collaborative filtering, and use collaborative signals to reduce overspecialization in content-based methods); often more robust to sparsity and noisy metadata than single-paradigm approaches. | Design and tuning are more complex (integration strategy, weighting, and hyperparameters); may require both rich item descriptors and sufficiently dense interaction logs; higher implementation and maintenance cost. | [29,37,38,40] |

| User Id | User Interaction |

|---|---|

| User1 |

|

| |

| |

| User2 |

|

| |

| |

| User3 |

|

| User4 |

|

| Dataset Theme | Total Provided Datasets | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meet All the Criteria | Meet All the Criteria | ||

| Precipitation | 47 | 17 | 10 |

| Soil Moisture | 15 | 7 | 4 |

| DTM/DEM | 13 | 10 | 10 |

| User | Metric | Mean Value | Min Value | Max Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real users—Group 1 | Recall | 62% | 26% | 86% |

| Precision | 68% | 27% | 84% | |

| Precision@5 | 73% | 30% | 100% | |

| Real users—Group 2 | Recall | 73% | 34% | 100% |

| Precision | 65% | 31% | 100% | |

| Precision@5 | 85% | 43% | 100% | |

| Dummy Users—Group 1 | Recall | 69% | 32% | 100% |

| Precision | 74% | 42% | 100% | |

| Precision@5 | 83% | 41% | 100% | |

| Dummy Users—Group 2 | Recall | 82% | 40% | 100% |

| Precision | 78% | 37% | 100% | |

| Precision@5 | 89% | 36% | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vahdat, A.; Badard, T.; Pouliot, J. A Semantic Collaborative Filtering-Based Recommendation System to Enhance Geospatial Data Discovery in Geoportals. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120495

Vahdat A, Badard T, Pouliot J. A Semantic Collaborative Filtering-Based Recommendation System to Enhance Geospatial Data Discovery in Geoportals. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120495

Chicago/Turabian StyleVahdat, Amirhossein, Thierry Badard, and Jacynthe Pouliot. 2025. "A Semantic Collaborative Filtering-Based Recommendation System to Enhance Geospatial Data Discovery in Geoportals" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120495

APA StyleVahdat, A., Badard, T., & Pouliot, J. (2025). A Semantic Collaborative Filtering-Based Recommendation System to Enhance Geospatial Data Discovery in Geoportals. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120495