Abstract

Understanding how public service accessibility is related to housing prices is crucial to housing equity, yet the heterogeneous capitalisation effect remains unknown. This study aims to investigate the spatial effect of public service accessibility on housing prices in rapidly urbanising regions. Here, we propose a novel methodological framework that integrates the hedonic price model, geographical detector model and the spatial association detector model to understand housing equity issues. The rapidly rising housing prices, vastly transformed urban planning and heterogeneous land use patterns make the urban centre of Wuhan a typical case study. High-value units of public service accessibility are concentrated in built-up areas, while low-value units are located at the urban fringe. The results indicate that larger public services have more significant clustering effects than smaller ones. Recreational, medical, educational and financial facilities all have capitalisation effects on housing prices. Both the geographical detector model and the spatial association detector model could identify the drivers of housing prices, but the explanatory power of the latter is greater and could enhance the validity and reliability of the findings. We further find that the explanatory power of the driving factors on housing prices obtained from the spatial association detector model is greater than that of the geographical detector model. Based on the spatial association detector model, the main drivers of public service facilities are accessibility to restaurants and bars and accessibility to ATMs. In addition, there are bivariate or nonlinear enhancement effects between each pair of driving factors. This approach provides significant insights for urban environmental development planning and local real estate planning.

1. Introduction

Spatial segregation and social exclusion, caused by rapidly growing global population pressures and the wealth gap, are driving unprecedented changes in social systems [1]. Socioeconomic status inequities are growing both within and among societies [2,3] and have become an indisputable reality in human settlements, especially in cities [4]. The rate of new housing construction has lagged far behind population growth in urban centres, and the gap between high housing prices and low affordability has led to growing migration to the outskirts of many burgeoning cities [5]. Housing costs have a significant impact on access to adequate and affordable housing, particularly for vulnerable groups [6]. In the context of the Sustainable Development Goals, the provision of equitable housing and infrastructure in settlements is fundamental to social equity [7]. Therefore, a redirection towards sustainability and well-being, which achieves the progressive realisation of the right to adequate housing, has been regarded as the most viable option for further development.

The spatial distribution, supply and demand of urban public service facilities are vital factors that affect the residents’ well-being [8,9,10]. Public services, as non-competitive public goods provided by the government, could bring economic benefits. When such economic benefits persist, they will enter asset prices and be influenced by the real estate market. This capitalisation effect represents a significant increase in the value of nearby housing as a result of investment in public services. Public services, such as cultural services, healthcare, eldercare and public transportation, could serve as catalysts to stimulate surrounding real estate development [11]. Public service facilities of superior quality in urban centres could stimulate residents’ willingness to buy houses and form a cluster of advantaged groups, thus attracting more public investment and providing better services [12]. However, imbalanced urbanisation and fragmented local government structures may cause concentralised patterns and spatial differences in public service provision [13,14]. These are capitalised to varying degrees, and thus affect housing price elasticities [15]. In addition, as residents are willing to pay more for better access to high-quality public services, space for high housing prices is likely to cluster together, and this distribution may offset the expected incentive effects of some policies [16,17]. For example, the simplistic educational policies pursuing equity, such as ‘nearby enrolment’ and ‘zero school choice’ policies [18], cannot achieve true equity, but rather reinforce the school district effect and aggravate inequities in neighbourhoods and educational opportunities [3]. In general, the spatial effect of accessibility to public service facilities on housing prices is not yet recognised.

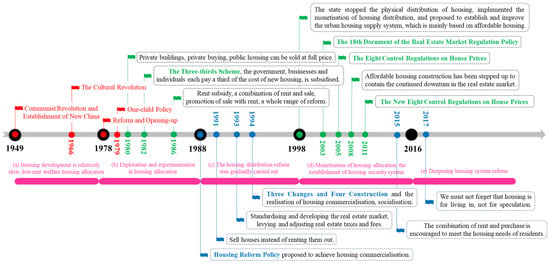

In addition, the causes of urban housing inequity could be explained by the dual mechanisms of the emerging housing market and the persisting socialist institution [19,20] (Figure 1). Prior to the economic reform and opening-up in 1978, China’s urban housing system was a welfare system that relied on unified national construction and low rent distribution [21,22]. This system had a strong constraint on urban spatial layout and social differentiation. After the economic reform and opening-up, China’s urban housing reform transformed access to housing from a socialist administrative allocation system to a more market-oriented housing development and consumption system [20,23]. The abolition of welfare housing policy provision in 1998 was a paramount milestone in Chinese urban housing reform, which shaped a market-oriented urban housing provision system [24]. Since then, the goal of housing commercialisation has provided Chinese urban households with the opportunity to choose their suitable houses and living environments [19]. Individuals with higher political status, better socioeconomic conditions and the possession of organisational resources and power were more likely to have access to superior living conditions [25,26]. The combined action of power and the market accelerates the division of urban housing space and gives way to the stratification process of housing space [27]. Accordingly, this historical process not only reveals China’s economic transformation and massive urbanisation process, but also affects residents’ well-being.

Figure 1.

The change of housing policy in China includes five stages: (a) 1978–1978: housing development was relatively slow, low-rent welfare housing allocation, (b) 1978–1988: exploration and experimentation in housing allocation, (c) 1988–1998: housing distribution reform was gradually carried out, (d) 1998–2016: monetisation of housing allocation and establishment of housing security system and (e) 2016–present: deepening housing system reform.

This study aims to determine the spatial effects of accessibility to public service facilities on housing prices. Specifically, this paper attempts to answer three interrelated research questions: (i) Is there a significant spatial heterogeneity in the accessibility of different public service facilities? (ii) How does the accessibility of different public service facilities affect housing prices? (iii) What are the implications of the research results for promoting housing equity? To effectively engage with these research questions, the pattern of public service facilities is portrayed by road network analysis and hotspot analysis. The relationship between the accessibility of public service facilities and housing prices is investigated through the hedonic price model, geographical detector model and the spatial association detector model. The issue of housing equity is then discussed for sustainable urban planning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Accessibility and Capitalisation Effect of Public Service Facilities on Housing Prices

Housing prices are an external feature of the housing economy and are related to the indispensable public service facilities in urban space resources. High-priced clusters with higher public service accessibility are found in the central urban areas, whereas low-priced clusters with lower accessibility are concentrated in the urban fringes [13]. The distribution of transportation hubs [28,29], educational facilities [18,30], green spaces [31] and leisure facilities [32] has a capitalisation effect on housing prices, even in different social systems and backgrounds. It has been proven that the spatial distribution pattern of housing prices is affected by the diverse functions of multiple public service facilities [33,34], and a bivariate enhancement effect emerges when any two of these interact [35]. The spatial convenience of the high coverage rate of public service facilities may conflict with the housing price enhancement effect of a single facility in a region [36]. However, most previous studies have aimed to examine the impact of single type of public service on housing prices.

The impact of the quality of various public service facilities on housing prices has been explored to capture capitalisation [34,37]. The same type but different grades of public service facilities have different capitalisation effects on housing prices [38,39]. For instance, Wen et al. proved that adding one kindergarten within 1 km of the community increased housing prices by 0.3%, and the distance between housing and high schools or universities within 1 km increased housing prices by 2.737% or 0.904% in Hangzhou, China [40]. Thus, the research on housing prices could benefit from an integrated framework that considers the comprehensive capitalisation effect of the grade of various public service facilities as well as the surrounding environment on housing prices.

2.2. The Hedonic Price Model Is Rooted in Public Services Being Capitalised into Housing Prices

The hedonic price model allows for the investigation of the impact of micro-factors on housing prices, revealing that almost all types of public goods are capitalised into housing prices to varying degrees [30]. Location, housing and environmental attributes all affect housing prices in the hedonic price model [41]. Relevant studies in China [42], the United States [43], Britain [44] and other countries have confirmed that there is a significant spatial dependence of housing prices. As a result, location attributes such as accessibility to public service facilities and the nearest-neighbour distance to metro and bus stations, as one of the factors influencing housing prices, are widely utilised to explain spatial variation in housing prices [45,46]. Although low-income groups could obtain employment opportunities through public transportation [47], the incremental effect of housing prices around metro and bus stations will increase the economic burden of low-income groups [48]. In addition, marginal prices of key housing attributes (e.g., building height) vary over space [49], and models containing spatially correlated variables are more applicable to most areas [41]. Buyers refer to the surrounding environmental attributes (e.g., rivers/lakes, parks and air quality) in the actual purchase process [50]. On the one hand, accessibility could increase housing prices through access to opportunities and services [51,52]. On the other hand, environmental changes caused by accessibility could increase air pollution and lead to lower housing prices [53,54]. However, the combined effects of accessibility and environmental health risks on housing prices have not been well-examined in the literature, especially in auto-oriented urban environments.

2.3. Measurement of the Capitalisation Effect of Different Levels in Public Service Facilities

Most previous studies have implicitly assumed that valuations are under uniform capitalisation conditions. However, the extent of capitalisation may vary in light of differences in land use and geographical location [18,30]. Likewise, Cheshire and Sheppard have demonstrated that the capitalisation of school quality is significantly discounted, especially in areas with new construction [55]. The supply level and supply quantity of urban public goods such as educational facilities, landscapes and hospitals are insufficient and spatially uneven relative to people’s growing demand [56]. Consequently, the implied prices of public service facilities are spatially heterogeneous [18]. Nevertheless, the traditional hedonic price model, which ignores the effect of spatial heterogeneity, is far from sufficient to reveal real-world phenomena and could be somewhat misleading.

Although the spatial lag model and spatial error model make up for the lack of a spatial dependence effect in the ordinary least squares model in the traditional hedonic price model and improve the fitting degree [36], they ignore the spatial variation and non-stationarity caused by the differences in spatial location characteristics [37]. The geographical detector model has been utilised in a range of studies to detect driving factors [57,58,59]. It could reflect the similarity of the same region and the differences between different regions [60,61]. Its main advantage is that it has fewer assumptions than other methods, such as regression [59,62], which overcomes the limitations of traditional statistical methods in dealing with variables [63,64]. In addition, it could detect the interaction between two variables without considering the collinearity of multiple independent variables [65]. Therefore, it is widely adopted in the study of natural and human influence mechanisms. However, the geographical detector model does not explicitly consider the spatial characteristics of the data and is also affected by factor discretisation [66]. The spatial association detector model is an improved spatial data association method, which takes into account the spatial characteristics of data and the information loss caused by discretisation. It allows better measurement of associations between spatial data distribution and reflects the relationship between the accessibility of public service facilities and housing prices.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area and Data Sources

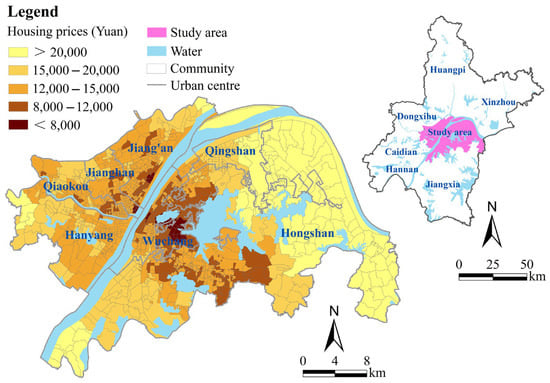

Wuhan is one of the most important central cities in China and is the capital of Hubei Province. It covered an area of 8569.15 km2 and had a residential population of 10.893 million as of 2019. Wuhan was listed as one of China’s megacities in 2016. With increasing urbanisation, considerable housing demand has led to a continuous and rapid adjustment of Wuhan’s land structure [67]. These typically reflect the development of megacities in developing countries. This study investigates the urban centre of Wuhan as defined in the Wuhan Urban Master Plan (2010–2020), which includes seven districts, namely Wuchang, Jianghan, Hanyang, Jiang’an, Qiaokou, Hongshan and Qingshan (Figure 2). It occupied an area of 955.15 km2 and had a residential population of 6.656 million as of 2019. The communities (n = 602) of the urban centre of Wuhan were taken as spatial research units. Due to the tremendous transformation and development of urban planning in Wuhan, the spatial structure pattern has developed from relatively simple to complex. This unique built environment is characterised by greater spatial heterogeneity in terms of accessibility to public services and house prices. The urban centre of Wuhan is therefore a suitable and representative example to explore this issue and can provide a necessary reference for urban planning in China and abroad [25].

Figure 2.

Housing prices in the urban centre of Wuhan, China.

Multi-source and heterogeneous data for both spatial and statistical aspects were integrated into this study. Specifically, (i) 3876 housing price data points (unit: yuan/m2) for 2020 were obtained through Lianjia (http://lianjia.com, accessed on 1 December 2020), the largest real estate intermediary website in China, (ii) the longitude and latitude of recreational, medical, educational and financial facilities were provided by the public service facilities layout map in 2020, (iii) community population survey data, land use data and road network data came from the Wuhan Natural Resources and Planning Bureau (http://whonemap.zrzyhgh.wuhan.gov.cn:8020, accessed on 1 December 2020) in 2020 and (iv) air pollution data (PM2.5 and ozone) were obtained from the Wuhan Environmental Protection Bureau (http://hbj.wuhan.gov.cn/hjsj, accessed on 1 December 2020).

3.2. Accessibility Measures

Road network analysis was employed to evaluate accessibility through the network analysis module of ArcGIS [25]. This method is considered suitable for both network routes and actual roads. It also allows the spatial analysis to connect point elements synthesised from facility attributes with linear elements formed by visualising the actual road network. Firstly, a vector road network database was established based on the road network categories, including the vector pedestrian network, the actual length of the road network, the pedestrian design speed and connectivity. Thereafter, different public service facilities were loaded, and analysis attributes were set up using the function of establishing service areas in Network Analyst. The hierarchical allocation of public service facilities was set according to the service radius specified in the planning and construction control of supporting facilities in the Standard for Urban Residential Area Planning and Design (GB50180–2018) and the Code for Urban Public Facilities Planning (GB50442–2008) (Table 1). Finally, the accessibility analysis based on the travel range was conducted in combination with the number of facilities in each community.

Table 1.

Hierarchical allocation of public service facilities.

3.3. Hotspot Analysis

Hotspot analysis is beneficial in identifying the location of statistically significant hotspots and cold-spots in the data [68,69]. This method involves clustering occurrence points into polygons or convergence points that are close to each other based on calculated distances. The analysis groups have these characteristics when similar high (hot) or low (cold) values are found within the clusters. This method works by viewing each accessibility unit around the community and comparing the local total of a single accessibility unit and its adjacent units with the total of all accessibility units. A statistically significant Z-score is reported when the local total is significantly different from the expected local total and cannot be randomly generated. The absolute value of the Z-score could be utilised to identify the spatial pattern in the accessibility distribution of public service facilities.

3.4. Hedonic Price Model

The hedonic price model is a widely adopted quantitative method for revealing the implicit price of housing attributes, the total of which is the hedonic price [70]. Sixteen independent variables were selected based on previous studies and conditions in the urban centre of Wuhan. They were divided into locational, housing and environmental variables. The accessibility of various public service facilities and the distance to the nearest metro station and bus station were highlighted as locational variables in the hedonic price model [45,46,47,71]. The number of plies is an essential indicator for the housing variables [49,72] and the environmental variables include distance to the nearest water, park and industrial land, and the air pollution concentrations (PM2.5 and ozone). In addition, housing price was selected as the dependent variable [54]. Variable definitions and expected effect signs are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The description of dependent and independent variables.

3.5. Geographical Detector and Spatial Association Detector Model

The geographical detector model is a statistical method for detecting spatial stratified heterogeneity and revealing its factors. This model includes a factor detector, ecological detector and an interaction detector [59,61].

The factor detector was employed to analyse the differences in accessibility to various public service facilities on housing prices [58]. If there was a significant spatial similarity between the accessibility intensity of certain public service facilities and housing prices, the spatial configuration of such public service facilities could be suggested to be decisive for the formation of housing prices. The formula is:

where is the explanatory power of the comprehensive accessibility of public service facilities that affect the housing prices, is the number of grids and is the number of sub-regions. is the number of grids in the secondary region, is the variance of housing prices within the study area and is the variance of housing prices in the sub-region. Assuming that ≠ 0, the model is valid. The value interval of is [0, 1]. When = 0, it indicates that the spatial distribution of housing prices is not driven by influencing factors. The higher the value of , the greater the impact of accessibility of public service facilities on the housing prices.

The ecological detector compared the difference in the total variance of housing prices among the driving factors to determine whether there was a significant difference in the influence of each factor. The formula is:

where is the test value, and are the sample size of factors and , respectively, and and represent the stratified number of variables and , respectively.

The interaction detector identified the interactions between different public service facilities. That is, whether the evaluation factors increased or decreased the explanatory power of housing prices, or whether these factors had an independent impact on housing prices. There were five types of interaction relationships, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptions of the interaction relationships.

The spatial association detector model is an improved method for exploring the relationship between dependent variables and potential independent variables [66]. The power of spatial and multilevel discretisation determinants is applied to measure spatial data association, which solves the problem of lacking spatial correlation in the original geographical detector model. This method not only explicitly considers spatial variance, but also minimises the information loss caused by the discretisation level [66]. The formula is:

where is the power of spatial and multilevel discretisation, is the total count of samples in the th category, is the total number of levels, is the total count of samples and represents the spatial variance. The subscripts and are the th level and the total level of the independent variables, respectively. The subscripts and are the th level and the total level of the dependent variable, respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Pattern Characteristics of Public Service Accessibility

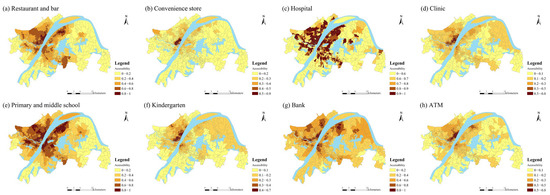

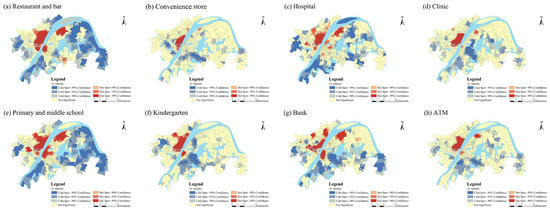

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial pattern of accessibility to public services in the urban centre of Wuhan, China: restaurants and bars, convenience stores, hospitals, clinics, primary and middle schools, kindergartens, banks and ATMs. There was significant spatial heterogeneity in the accessibility of public services. The high-value units of public service accessibility were concentrated in the built-up areas, suggesting that urban construction and development have promoted the spatial agglomeration of public service resources and more efficient land use. In contrast, low-value units of public service accessibility were located at the urban fringe and are less attractive to labour and capital. Figure 4 plots the hotspots of public service facilities in the urban centre of Wuhan, China. The cold-spots were much more prevalent than the hotspots, with the hotspots concentrated in the built-up areas, while the cold-spots were mostly located at the urban fringe. Larger public services, such as restaurants and bars, hospitals, primary and middle schools and banks, have more significant clustering effects than smaller public services, such as convenience stores, clinics, kindergartens and ATMs.

Figure 3.

Spatial accessibility pattern of public service facilities in the urban centre of Wuhan, China.

Figure 4.

Hotspot map of public service facilities in the urban centre of Wuhan, China.

4.2. The Influence of Driving Factors on Housing Prices

As a public product, public service facilities provide convenience for residents. The economic attributes significantly impact the externality of the real estate market. The results of the hedonic price model, geographical detector model and the spatial association detector model indicated that the accessibility of public service facilities has been capitalised into housing prices to some extent. The uneven spatial distribution of public service facilities promotes population agglomeration in big cities and urban core areas. This process has raised housing prices in these areas, leading to the divergence in the distribution of housing prices.

The factor detector results for the geographical detector and spatial association detector models are shown in Table 4. The variables largely passed the 5% significance level test, indicating that the capitalisation effects of most factors on housing prices were relatively significant, although the extent of these effects varied. Moreover, the explanatory power of the driving factors on housing prices obtained from the spatial association detector model was greater than that of the geographical detector model. Based on the spatial association detector model, the main driving factors affecting housing prices were D_INDUS and D_METRO, followed by A_RESTA and A_ATM. Among the locational variables, D_METRO (q = 0.457) had the greatest impact on housing prices, followed by the other two locational variables: A_RESTA (q = 0.418) and A_ATM (q = 0.412). The housing variable, which is FLOOR (q = 0.340), had a smaller impact on housing prices than the locational variables. Among the environmental variables, D_INDUS (q = 0.469) had the dominant influence, followed by PM2.5 (q = 0.333) and Ozone (q = 0.365), while D_WATER (q = 0.250) and D_PARK (q = 0.161) had the least influence on housing price values. In addition, different grades of the same type of public service facilities had varying interpretative power on housing prices.

Table 4.

Comparison of results of the geographical detector and spatial association detector models.

4.3. Statistical Significance of Differences among Driving Factors

The significance of different effects among the sixteen driving factors was investigated via the ecological detector. The ecological detector reflected whether there were significant differences in the spatial distribution of housing prices among various driving factors and tested the significance level of 5%. If a significance level existed, it was marked with a ‘Y’, and vice versa with an ‘N’ (Table 5). The results revealed statistically significant differences in the relationship between A_RESTA and other public service variables, including A_STORE, A_HOSPI, A_CLINIC, A_KINDE, A_BANK and A_ATM, in the spatial distribution of housing prices. In addition, there were also statistically significant differences in the spatial distribution of housing prices in the relationship between A_SCHOOL and other variables, such as A_STORE, A_HOSPI, A_CLINIC, A_KINDE, A_BANK and A_ATM.

Table 5.

Statistical significance of the differences between two variables based on the ecological detector.

4.4. The Interactive Effects of Driving Factors on Housing Prices

As shown in Table 6, the interaction detector module of the geographical detector model detected multiple pairs of interactions among the sixteen driving factors, which suggests that the effect of each factor on housing prices was not independent but joint. The synergistic effects between each pair of driving factors manifested themselves as a bivariate enhancement or nonlinear enhancement affecting housing prices. This demonstrates that the interaction between two driving factors strengthened the impact of each factor on housing prices in this study. Among the bivariate enhanced interactions for all driving factors, q (D_METRO ∩ Ozone) was the maximum (0.560), evidencing the strongest bivariate enhancement interaction between D_METRO and Ozone, followed by q (A_CLINIC ∩ D_METRO) and q (D_METRO ∩ A_ATM) with values of 0.504 and 0.501. Among the nonlinear enhanced interactions for all driving factors, q (D_METRO ∩ FLOOR) was the largest (0.484), followed by q (D_METRO ∩ FLOOR) with a value of 0.474.

Table 6.

The statistical results of the interaction detector, which was used to identify whether two variables had an interactive effect on housing prices.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Heterogeneous Capitalisation Effect of Housing Prices

In terms of urban spatial resource allocation, various types of public services, such as recreational, medical, educational and financial facilities, all had capitalisation effects on housing prices based on the spatial association detector model. Recreational facilities closely related to daily life could meet the basic needs of residents’ lives and represent the convenience of regional life. The fast-paced life has led residents to demand more convenience from restaurants, bars and convenience stores, boosting housing prices. The construction of medical facilities such as hospitals and clinics not only has an essential impact on residents’ health and well-being, but also contributes to land development intensity, which results in increased property values in the vicinity. Educational facilities have a positive effect on the promotion of real estate and the increase in housing prices. The capitalisation effect of primary and middle schools is significantly higher than that of kindergartens, taking into account the ‘nearby enrolment’ and ‘zero school choice’ policies, and such findings are similar to those of Wen et al. [73]. In addition, evidence indicates that the capitalisation effect of ATMs is more pronounced than that of banks, and that financial facilities significantly contribute to forming the distribution pattern of housing prices.

The traffic condition is also regarded as one of the most critical factors affecting housing prices [54,74]. The construction of the metro not only changes urban land use and promotes land development intensity, but also improves the accessibility of surrounding properties to various urban services [47,75]. To a certain extent, it could reduce the time cost of residents’ travel and living, thus affecting the surrounding housing prices. The main reasons why the distance to the nearest metro station has significantly higher explanatory power for housing prices than the distance to the nearest bus station are the scarcity of metro stations and their significant increase in accessibility. The number of plies also plays an essential role in housing prices. In addition, there is also a spatial spill-over effect on housing prices for environmental elements such as rivers/lakes, parks and industrial land, as well as PM2.5 and ozone pollutants. Inhabitants are more willing to pay a higher price for comfortable environmental conditions due to the increasing importance residents place on their quality of life [26].

This study also revealed that the interaction effect between each pair of driving factors manifested itself as a bivariate enhancement or nonlinear enhancement affecting housing prices. Looking at our findings from another perspective, we could also speculate that the interaction between the two driving factors strengthened the effect of each on housing prices, and therefore urban planners could pay attention to multiple driving factors to promote a rational distribution of public services and housing equity.

5.2. Contributions and Limitations

Theoretically, we proposed an integrated framework to explain why and how the accessibility of multiple public services at different levels affects housing prices. Location attributes, housing attributes and environmental attributes were considered simultaneously, thus renewing knowledge about the heterogeneous capitalisation effect of public service accessibility on housing prices. It provides policy implications for the reasonable allocation of public services and housing equity. Methodologically, in contrast to previous studies that have used multiple regression models to explore the determinants of housing prices, this study applied the geographical detector model and the spatial association detector model to identify the individual and interactive effects of factors on housing prices. Particularly, this study confirmed that the hedonic price model, geographical detector model and the spatial association detector model could be valuable tools for examining differential impacts and interactions between the factors involved in housing prices, as the methodology is relatively simple and easy to implement. The methodology is not limited by geographical location and is flexible enough to be replicated and applied to other urban areas in both developed and developing countries.

However, several limitations should be mentioned in this study. First, housing authorities only keep records of housing prices for second-hand housing transactions. There are no official statistical data on rental housing or housing rental prices. Second, accessibility is not only related to the quantity of public service facilities, but also to their quality. Future research could serve housing equity by considering both simultaneously. Third, it is necessary to describe how public service facility land is provided in light of the information from the urban plans and land use plans to help understand the underlying logic of public service facility provision. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the daily commuting behaviours of urban residents. It would be valuable to monitor the changing housing rental prices, in order to examine whether the impact on housing rental prices would present different characteristics in the post-pandemic era.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study provided a novel framework for a comprehensive understanding of the spatial effect of public service accessibility on housing prices. Following this framework, we revealed the heterogeneous capitalisation effect of public service accessibility on housing prices, which provides policy implications for the rational allocation of public services and housing equity. The urban centre of Wuhan, China, was selected as a representative case study. The main conclusions obtained were as follows.

Spatial heterogeneity in the accessibility of public services was evident in the high-value units found in built-up areas, while low-value units were located at the urban fringe. Larger public services such as restaurants and bars, hospitals, primary and middle schools and banks had more significant clustering effects than smaller public services, such as convenience stores, clinics, kindergartens and ATMs. Various types of public services, such as recreational, medical, educational and financial facilities, all had capitalisation effects on housing prices. The explanatory power of the driving factors on housing prices obtained from the spatial association detector model was greater than that of the geographical detector model. Based on the spatial association detector model, the main driving factors affecting housing prices were distance to the nearest industrial land and distance to the nearest metro station, followed by accessibility to restaurants and bars and accessibility to ATMs. The interaction of any two driving factors strengthened the impact of each on housing prices in this study. We found that among the bivariate enhanced interactions for driving factors, the interaction between D_METRO and Ozone was the strongest. Among the nonlinear enhanced interactions for driving factors, the interaction between D_METRO and FLOOR was the strongest. The lessons learned from this study should be insightful for urban planning.

Several policy and practice recommendations could be drawn for housing equity. Firstly, the government, as an administrative subject, could assume responsibility for dealing with public affairs and developing policies and practices to provide adequate support and assistance for housing equity and equitable access to public services for urban residents. On the one hand, the taxation system reform could be accelerated. It is essential to assess property values in a timely and appropriate manner based on the availability of public services. On the other hand, the government could increase investment in basic public services such as leisure, education, healthcare and finance, and ensure equity in housing resources through income redistribution. For the urban fringe, establishing accurate management mechanisms for public service facilities and anticipating the actual needs of residents are important in order to develop sustainable public service policies. Secondly, as there are differences in the impact of various types of public service facilities on housing prices, policymakers or planners are recommended to consider the priority of public services when making spatial allocations of resources. Priority should be given to public services that are urgently needed in residents’ lives to reduce the inequities caused by capitalisation. It is proposed to improve the accessibility of the metro station by providing additional transport links to the metro. The subsequent provision of additional restaurants and ATMs to meet the basic needs of residents would reduce the disparity in property values due to the insufficient supply of public services. It is also recommended that policies be formulated to prioritise the reduction of environmental pollution around industrial areas, such as strict control of PM2.5 and ozone pollution caused by industrial production. On this basis, the layout of parks, green spaces and rivers/lakes will be improved, and the differentiation of living spaces will be alleviated through land exchange and urban redevelopment. Lastly, it is necessary to consider the combined effect of public services and transport and environmental factors. Our findings revealed a strong synergistic capitalisation between housing prices and locational, housing and environmental variables. Urban planners are therefore recommended to consider the impact of various factors on housing prices when formulating policies. Specifically, public services such as stores and clinics should be added in areas of low accessibility to reduce spatial segregation and social exclusion generated by negative externalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Peiheng Yu and Yiyun Chen; methodology, Peiheng Yu, Esther H. K. Yung, Edwin H. W. Chan and Yiyun Chen; software, Peiheng Yu and Shujin Zhang; validation, Peiheng Yu and Siqiang Wang; formal analysis, Peiheng Yu and Yiyun Chen; investigation, Peiheng Yu, Esther H. K. Yung and Edwin H. W. Chan; resources, Peiheng Yu; data curation, Shujin Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Peiheng Yu; writing—review and editing, Esther H. K. Yung, Edwin H. W. Chan and Yiyun Chen; visualization, Shujin Zhang and Siqiang Wang; supervision, Esther H. K. Yung, Edwin H. W. Chan and Yiyun Chen; project administration, Esther H. K. Yung and Yiyun Chen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the General Research Fund of the Hong Kong SAR Government (PolyU 156102/18H) and the Seed Fund Program for Sino–Foreign Joint Scientific Research Platform of Wuhan University (Grant No. WHUZZJJ202216).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alibašić, H. Envisaging the Future of Strategic Resilience and Sustainability Planning. In Strategic Resilience and Sustainability Planning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy, L.; Pontusson, J. Rising Inequality and the Politics of Redistribution in Affluent Countries. Perspect. Polit. 2005, 3, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Song, W.; Liu, C. Social-Spatial Accessibility to Urban Educational Resources under the School District System: A Case Study of Public Primary Schools in Nanjing, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, J.; Dol, K. Attitudes towards Housing Equity Release Strategies among Older Home Owners: A European Comparison. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 1347–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.; Wong, F.W.; Hui, C.M.E. Relationship between Housing Affordability and Economic Development in Mainland China-Case of Shanghai. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2006, 132, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Chen, J.; Guo, J. Exploring Determinants of Housing Prices in Beijing: An Enhanced Hedonic Regression with Open Access POI Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.S.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Antons, D.C.; Munoz, P.; Bai, X.; Fragkias, M.; Gutscher, H. A Vision for Human Well-Being: Transition to Social Sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E.H.W. Public Open Spaces Planning for the Elderly: The Case of Dense Urban Renewal Districts in Hong Kong. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yung, E.H.K.; Cerin, E.; Yu, Y.; Yu, P. Older People’s Usage Pattern, Satisfaction with Community Facility and Well-Being in Urban Old Districts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Winky, K.O.H.; Chan, E.H.W. Elderly Satisfaction with Planning and Design of Public Parks in High Density Old Districts: An Ordered Logit Model. Landsc. Urban Plan 2017, 165, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chau, K.W.; Wang, X. Are Low-End Housing Purchasers More Willing to Pay for Access to Basic Public Services? Evidence from China. Res. Transp. Econ. 2019, 76, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, F.; Langset, B.; Rattsø, J.; Stambøl, L. Using Survey Data to Study Capitalization of Local Public Services. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2009, 39, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Shi, W.; Deng, Z.; Wang, H. Residential Clustering and Spatial Access to Public Services in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Xiao, Y.; Hui, E.C.M. Quantile Effect of Educational Facilities on Housing Price: Do Homebuyers of Higher-Priced Housing Pay More for Educational Resources? Cities 2019, 90, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilber, C.A.L. The Economic Implications of House Price Capitalization: A Synthesis. Real Estate Econ. 2017, 45, 301–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, T.; Jing, Y.; Fang, F. The Effects of Locational Factors on the Housing Prices of Residential Communities: The Case of Ningbo, China. Habitat Int. 2018, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hu, S.; Wang, S.; Zou, L. Effects of Rapid Urban Land Expansion on the Spatial Direction of Residential Land Prices: Evidence from Wuhan, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 101, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayantha, W.M.; Lam, S.O. Capitalization of Secondary School Education into Property Values: A Case Study in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, L. Housing Inequality in Transitional Beijing. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 936–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Housing Inequality in Urban China: Theoretical Debates, Empirical Evidences, and Future Directions. J. Plan. Lit. 2019, 35, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, F. Socio-Spatial Differentiation and Residential Inequalities in Shanghai: A Case Study of Three Neighbourhoods. Hous. Stud. 2006, 21, 695–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, F. Tenure-Based Residential Segregation in Post-Reform Chinese Cities: A Case Study of Shanghai. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2008, 33, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. China’s Evolving Inequality. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2017, 15, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, F.; Wu, Y. One Decade of Urban Housing Reform in China: Urban Housing Price Dynamics and the Role of Migration and Urbanization, 1995-2005. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Embedding of Spatial Equity in a Rapidly Urbanising Area: Walkability and Air Pollution Exposure. Cities 2022, 131, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y. Capturing Open Space Fragmentation in High—Density Cities: Towards Sustainable Open Space Planning. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 154, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Access to Housing in Urban China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Golub, A.; Kuby, M. Combined Impacts of Highways and Light Rail Transit on Residential Property Values: A Spatial Hedonic Price Model for Phoenix, Arizona. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 41, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Bai, X.; Xu, M. The Influence of Beijing Rail Transfer Stations on Surrounding Housing Prices. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, E.; Patrick, C. Paying for Priority in School Choice: Capitalization Effects of Charter School Admission Zones. J. Urban Econ. 2017, 100, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, P.; Chen, Y.; Jing, Y.; Zeng, F. Accessibility of Park Green Space in Wuhan, China: Implications for Spatial Equity in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Humphreys, B.R. The Impact of Professional Sports Facilities on Housing Values: Evidence from Census Block Group Data. City Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D.; Wu, Y.; Tian, G. Analyzing Housing Prices in Shanghai with Open Data: Amenity, Accessibility and Urban Structure. Cities 2019, 91, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Deng, Z.; Shi, W.; Wang, H. Local Public Expenditure, Public Service Accessibility, and Housing Price in Shanghai, China. Urban Aff. Rev. 2019, 55, 148–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ye, X.; Du, Q.; Luo, P. Spatial Effects of Accessibility to Parks on Housing Prices in Shenzhen, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Wei, Y.D.; Li, H. Effects of Accessibility and Environmental Health Risk on Housing Prices: A Case of Salt Lake County, Utah. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 89, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, T.; Da, H. Spatial Effects of Public Service Facilities Accessibility on Housing Prices: A Case Study of Xi’an, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panduro, T.E.; Veie, K.L. Classification and Valuation of Urban Green Spaces-A Hedonic House Price Valuation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Wilson, B.; Mosey, G.; Deal, B. Spatial Impacts of Multimodal Accessibility to Green Spaces on Housing Price in Cook County, Illinois. Urban For. Urban Green 2022, 67, 127370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Do Educational Facilities Affect Housing Price? An Empirical Study in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligus, M.; Peternek, P. Impacts of Urban Environmental Attributes on Residential Housing Prices in Warsaw (Poland): Spatial Hedonic Analysis of City Districts. In Contemporary Trends and Challenges in Finance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.C.; Wang, X. Hedonic House Prices and Spatial Quantile Regression. J. Hous. Econ. 2012, 21, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.P.; Ioannides, Y.M.; Wirathip Thanapisitikul, W. Spatial Effects and House Price Dynamics in the USA. J. Hous. Econ. 2016, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B.H.; Fingleton, B.; Pirotte, A. Spatial Lag Models with Nested Random Effects: An Instrumental Variable Procedure with an Application to English House Prices. J. Urban Econ. 2014, 80, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, D.R.; Ihlanfeldt, K.R. Identifying the Impacts of Rail Transit Stations on Residential Property Values. J. Urban Econ. 2001, 50, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrezion, G.; Pels, E.; Rietveld, P. The Impact of Rail Transport on Real Estate Prices: An Empirical Analysis of the Dutch Housing Market. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, L.; Zhao, P. The Impact of Metro Services on Housing Prices: A Case Study from Beijing. Transportation 2017, 46, 1291–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Lu, F. Exploring Housing Rent by Mixed Geographically Weighted Regression: A Case Study in Nanjing. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitter, C.; Mulligan, G.F.; Dall’erba, S. Incorporating Spatial Variation in Housing Attribute Prices: A Comparison of Geographically Weighted Regression and the Spatial Expansion Method. J. Geogr. Syst. 2007, 9, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.M.; Liang, C. Spatial Spillover Effect of Urban Landscape Views on Property Price. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 72, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Bardhan, R.; Sarkar, S.; Kumar, V. Framework to Assess and Locate Affordable and Accessible Housing for Developing Nations: Empirical Evidences from Mumbai. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Rees, P.; Xiang, L. Do Residents of Affordable Housing Communities in China Suffer from Relative Accessibility Deprivation? A Case Study of Nanjing. Cities 2019, 90, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D.; Yu, Z.; Tian, G. Amenity, Accessibility and Housing Values in Metropolitan USA: A Study of Salt Lake County, Utah. Cities 2016, 59, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkovich, O.; Rouwendal, J.; van Marwijk, R. The Effects of Highway Development on Housing Prices. Transportation 2016, 43, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, P.; Sheppard, S. Capitalising the Value of Free Schools: The Impact of Supply Characteristics and Uncertainty. Econ. J. 2004, 114, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wei, Y.D.; Wu, J. Amenity Effects of Urban Facilities on Housing Prices in China: Accessibility, Scarcity, and Urban Spaces. Cities 2020, 96, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Li, X.H.; Christakos, G.; Liao, Y.L.; Zhang, T.; Gu, X.; Zheng, X.Y. Geographical Detectors-Based Health Risk Assessment and Its Application in the Neural Tube Defects Study of the Heshun Region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Zhang, T.L.; Fu, B.J. A Measure of Spatial Stratified Heterogeneity. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and Prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yang, R.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. Delineation of the Northern Border of the Tropical Zone of China’s Mainland Using Geodetector. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Stein, A. The Spatial Statistic Trinity: A Generic Framework for Spatial Sampling and Inference. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 134, 104835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Tan, M. Using a Geographical Detector to Identify the Key Factors That Influence Urban Forest Spatial Differences within China. Urban For. Urban Green 2020, 49, 126623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, S.; Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Luan, B.; Chen, Y. On the Urban Compactness to Ecosystem Services in a Rapidly Urbanising Metropolitan Area: Highlighting Scale Effects and Spatial Non–Stationary. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 98, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, P.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Rice–Crayfish Field in Mid-China and Its Socioeconomic Benefits on Rural Revitalisation. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 139, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zhang, J. The Spatial Impact of Population on Housing Price in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration, China. In Chinese Cities in the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 199–214. ISBN 9783030347802. [Google Scholar]

- Cang, X.; Luo, W. Spatial Association Detector (SPADE). Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 32, 2055–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Pan, Y. Human Capital, Housing Prices, and Regional Economic Development: Will “Vying for Talent” through Policy Succeed? Cities 2020, 98, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The Analysis of Spatial Association by Use of Distance Statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.Z.Y.; Qian, J. Land-Based Finance, Fiscal Autonomy and Land Supply for Affordable Housing in Urban China: A Prefecture-Level Analysis. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S. Hedonic Prices and Implicit Markets: Product Differentiation in Pure Competition. In Revealed Preference Approaches to Environmental Valuation Volumes I and II; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781351903448. [Google Scholar]

- Arundel, R. Equity Inequity: Housing Wealth Inequality, Inter and Intra-Generational Divergences, and the Rise of Private Landlordism. Hous. Theory Soc. 2017, 34, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.M.; Zhong, J.W.; Yu, K.H. The Impact of Landscape Views and Storey Levels on Property Prices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, L. School District, Education Quality, and Housing Price: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Hangzhou, China. Cities 2017, 66, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guo, Q. Analysis of Residential Space Structure Based on Housing Price in Lanzhou City. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 446, 022017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. The Impact of Metro Accessibility on Residential Property Values: An Empirical Analysis. Res. Transp. Econ. 2018, 70, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).