1. Introduction and Motivation

The GeoSPARQL standard, issued in 2012 by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) (

https://www.ogc.org, accessed on 30 October 2021) is one of the most popular

Semantic Web standards for spatial data. References to GeoSPARQL in other well-known standards, such as DCAT2 [

1] and CIDOC-CRM [

2,

3] suggests it is popular, as do the incoming links in Linked Open Vocabularies (

https://lov.linkeddata.es/dataset/lov/vocabs/gsp, accessed on 30 October 2021) and the list of implementors that includes most of the popular triplestore vendors, a list of which has been compiled here:

https://github.com/opengeospatial/ogc-geosparql/issues/59, accessed on 30 October 2021. The original release–GeoSPARQL 1.0 [

4]–contained:

In this form, GeoSPARQL 1.0 has been used widely; however, requests for updates to it have been received by the OGC. In this publication, an extension of the workshop paper [

11], we discuss the motivations behind updating GeoSPARQL 1.0 in the remainder of this section, content of the planned GeoSPARQL 1.1 release (see the GeoSPARQL working repository for the latest candidate release form of GeoSAPRQL 1.1:

https://github.com/opengeospatial/ogc-geosparql, accessed on 30 October 2021) in

Section 2 and reference implementations and use cases in

Section 3 and

Section 4. Finally, in

Section 5, we provide an outlook to further feature requests which are likely to be tackled in future GeoSPARQL releases or replacements.

As the GeoSPARQL 1.1 standard, at the time of publication of [

11] had still been in active development, we point to changes which have occurred since. These changes involve the removal of the class

geo:SpatialMeasure and the inclusion of several supplementary materials (alignments, SHACL shapes and JSON-LD contexts) on which we elaborate extensively in this publication.

The OGC and World Wide Web Consortium’s (W3C)

Spatial Data On The Web Working Group (SDWWG) published a list of Best Practice points (see

https://w3c.github.io/sdw/bp/, accessed on 30 October 2021 for an accessible version of the points online and [

12] for the corresponding academic publication) for rating web-based spatial data. Through the use of that rating system and other work, the SDWWG noted that: “A best practice for returning geometries in a specific requested CRS has not yet emerged”. Given the scope of GeoSPARQL 1.0, this statement indicates that GeoSPARQL 1.0 had not then ‘solved’ web-based spatial data publishing. The group also informally captured specific suggested updates for GeoSPARQL (

https://www.w3.org/2015/spatial/wiki/Further_development_of_GeoSPARQL, accessed on 30 October 2021), however no updates to GeoSPARQL itself were then made.

The authors note that in the 3+ years since that statement’s publication, GeoSPARQL 1.0 has become far more widely supported by Semantic Web databases (so-called “triplestores”) and other Semantic Web applications, as evidenced by frequent attempts to benchmark geospatial-aware triplestores for GeoSPARQL compliance and performance [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Some further notes on GeoSPARQL support is provided in

Section 5.1.

In 2019, the OGC reconstituted the

GeoSPARQL Standards Working Group (SWG) to update GeoSPARQL. The motivation for work within the area of GeoSPARQL, that of spatial

Semantic Web data more generally, and some specific fault fixes and proposed extensions to GeoSPARQL 1.0 are captured in an OGC White Paper [

17]. Some, but not all, of the SDWWG’s issues raised were taken up by the SDW, for example, the

Best Practices [

12] aspiration that “A possible way forward is an update for the GeoSPARQL spatial ontology. This would provide an agreed spatial ontology, i.e., a bridge or common ground between geographical and non-geographical spatial data

…”. This issue is specifically addressed in GeoSPARQL 1.1’s extensions for scalar spatial data.

Other Best Practices issues raised such as “it makes sense to publish different geometric representations of a spatial object that can be used for different purposes” are partly addressed; GeoSPARQL 1.1 indeed indicates how to use multiple geometric representations of geometries in relation to a single feature, but concepts such as defining roles for geometries, with respect to features, have not been implemented.

The SWG’s Charter–their final scope of work–is also published by the OGC [

18] and this guided the SWG’s activities. Specific actions of the SWG and their staging are explained through the use of a publicly-available, online, task tracking system within the SWG’s working online code repository (

https://github.com/opengeospatial/ogc-geosparql/projects/1, accessed on 30 October 2021).

At a high-level, proposed updates to GeoSPARQL by both the SDWWG and the SWG may be categorised as one of the following:

New geometry serialisations:

- −

GeoJSON, KML and other now-popular formats missing from GeoSPARQL 1.0.

- −

The possibility to convert between literal formats in-query.

New and specialised ontology classes and properties:

- −

More nuanced spatial data representation and alignment with other systems.

More spatial functions:

- −

Implementing functions well-known in non-Semantic Web spatial systems.

Scalar spatial properties:

- −

Area, volume, etc., alongside geometries.

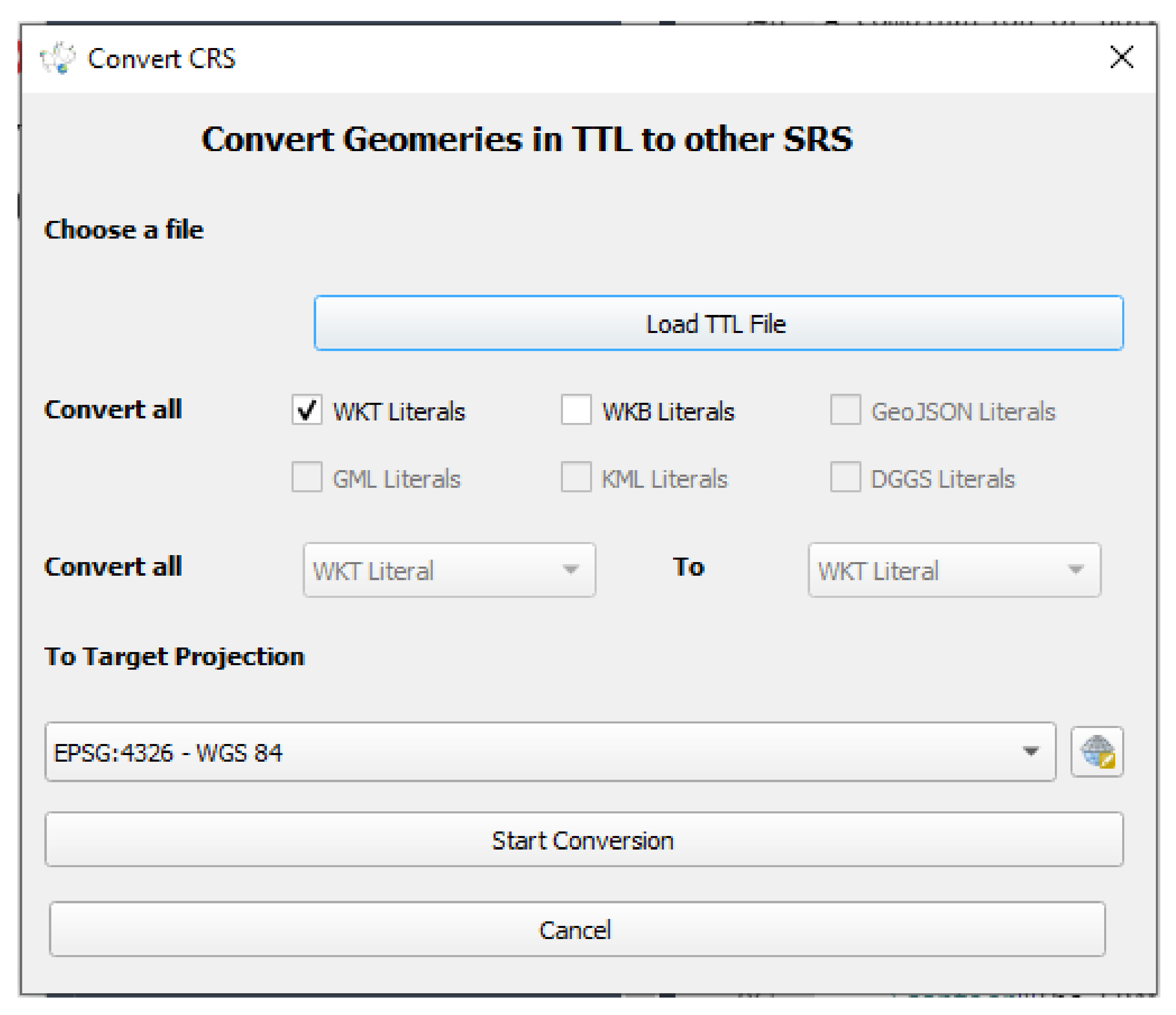

Better handling of Spatial (Coordinate) Reference Systems (SRS)

- −

Allowing for automated coordinate serialisation conversions.

Internet protocol-based selection of different geometries for features.

Some of these proposed updates were predicted in GeoSPARQL 1.0, with the Future Work section listing several of the points above. The SWG’s Charter, anticipating that the more obvious updates such as new geometry serialisations would certainly be implemented, listed the following extra areas of investigation that emerged from SWG proponent’s discussions:

Revising “upper ontology” GeoSPARQL structure–how its classes relate to fundamental concepts in ontology;

Alignments to other ontologies, perhaps

W3C Time Ontology in OWL [

19];

Catering for very different SRSes, such as Discrete Global Grid Systems.

Specifically ruled out of scope in the Charter was any investigation of property graphs. Recent (last several years) discussions in the OGC and elsewhere about property graphs motivated their consideration. However, the SWG proponents felt that while property graphs might be important for future Semantic Web spatial data systems, there was more than enough work scoped for initial SWG work (several revisions of the standard) to initially exclude this area of investigation.

After initial meetings, the SWG determined to make multiple versioned releases of GeoSPARQL updates with different goals:

1.1: Extensions that are fully compatible with GeoSPARQL 1.0;

1.2: Fully or mostly compatible extensions but which are larger additions to the standard’s conceptual coverage;

2.0: Future GeoSPARQL likely incompatible with GeoSPARQL 1.0.

The reason for expecting a future, incompatible, GeoSPARQL 2.0 is that early SWG attendees thought spatio-temporal relations and fundamental ontology elements in GeoSPARQL either could or should be remodeled, which might break the current, familiar, feature/geometry class relations. Details of these potential changes have not been fully expounded at the time of this paper, however initial SWG attendees’ intuition is that a future GeoSPARQL 2.0, or perhaps a renamed GeoSPARQL replacement, might generalise spatial concepts and move away from only, or primarily,

geospatial, or perhaps focus not just on feature/geometry relations but look to generalised mechanisms for describing dimensions of features of which

geometry is just one of many, and

temporality might be another. See

Section 5 for further details.

Originally unexpected, an area of updates to standard presentation was considered by the SWG. Motivation from conceptual work within the W3C and OGC for the presentation of multi-part standards and the desire by the OGC’s “Naming Authority”. (the Naming Authority (

https://www.ogc.org/projects/groups/ogcnasc, accessed on 30 October 2021) has the remit to “…ensure an orderly process for assigning URIs for OGC resources, such as OGC documents, standards, XML namespaces, ontologies” and also acts as a process evangelist, promoting, as it sees, better standards publication practice) to publish standards more systematically and in more machine-readable forms, as well as programs of work such as the OGC’s “Test Bed 17: Model Driven-Standards” (The Testbed 17 work package “Model Driven Standards” (

https://portal.ogc.org/files/?artifact_id=95726#ModelDrivenStandards, accessed on 30 October 2021) focused on generating documents from models but also partly developed test implementations of formally-defined, multi-part, standards, such as GeoSPARQL 1.1), this has resulted in the profile declaration explained in the next section.

2. Updates in GeoSPARQL 1.1

In 2021, the GeoSPARQL SWG addressed many of the GeoSPARQL change requests in the 1.1 release. All of the changes reported here are now visible in the current working draft of the GeoSPARQL 1.1 standard, the specification document, and the other standard parts [

20]. It is expected that the candidate standard will remain essentially unchanged through to final publication, barring perhaps minor updates due to wider implementation feedback. This section lists work completed only (see

Section 5.1 for further notes on final GeoSPARQL 1.1 work) and will point out new features, possibilities, and applications of the elements included in the GeoSPARQL 1.1 update. At first, we discuss the new structure of the standard’s specification (

Section 2.1), describe relevant extensions to the ontology model and query language in

Section 2.4 and

Section 2.9.

2.1. Profile Declaration

One of the first SWG actions was to link GeoSPARQL 1.0 elements through a

profile declaration, where a

profile is a formally-defined variant of a

standard.

profile and

standard, as well as relations between them and their parts, are defined by

The Profiles Vocabulary [

21].

The initial motivation for this was twofold: the SWG’s recognition that GeoSPARQL 1.0 consisted of multiple parts, not all of which were easy to discover, so some GeoSPARQL users were unaware of GeoSPARQL resources, some of which have been accidentally duplicated or partly re-implemented, and the desire for machine-readable forms of as many of the standard’s parts as possible.

Descriptions of multi-part standards using the Profiles Vocabulary are anticipated by the OGC as being their future best practice method for standards delivery (This is ascertained through personal communication with the OGC’s Naming Authority staff, one of whom was a co-editor of The Profiles Vocabulary).

As the elements of GeoSPARQL 1.1 have been created, they too have been described using the Profile Vocabulary, and GeoSPARQL 1.0 has been indicated as being a profile of, that is, a subset of, GeoSPARQL 1.1 since all GeoSPARQL 1.0 elements are present in GeoSPARQL 1.1.

The profile declaration for GeoSPARQL 1.0 and all of its parts will be published alongside those of GeoSPARQL 1.1, currently expected in early 2022. Currently, all draft 1.0 and 1.1 resources are available in the SWG’s online code repository (

https://github.com/opengeospatial/ogc-geosparql, accessed on 30 October 2021).

The 1.1 releases’ profile resources, described using roles given in the Profiles Vocabulary are:

A profile declaration

A specification resource

As per GeoSPARQL 1.0, the normative document of the GeoSPARQL standard

Contains requirements and conformance classes

Presented as a document in human-readable form (a PDF) but also containing normative code (schema) snippets and function definition tables and examples

An RDF/OWL model schema resource

Several vocabulary resources

Mainly derived from the schema

Presented in human- and machine-readable forms of the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) taxonomy model [

22]

There are vocabularies for Functions, Rules, Conformance Classes in addition to GeoSPARQL 1.0’s Simple Features definitions

JSON-LD ‘context’ mappings

A validation resource

A series of Shapes Constraint Language (SHACL) [

23] shapes for RDF data validation.

All elements of the GeoSPARQL 1.1 profile are listed and linked to in the profile declaration’s current draft, online location:

2.2. Ontology Extensions

GeoSPARQL 1.1 extends the GeoSPARQL ontology by adding multiple new properties and three collection classes. Initially, the SWG proposed a

SpatialMeasure class to represent scalar spatial measurements too, but this was ultimately not added in favour of a series of ‘size’ properties only. See

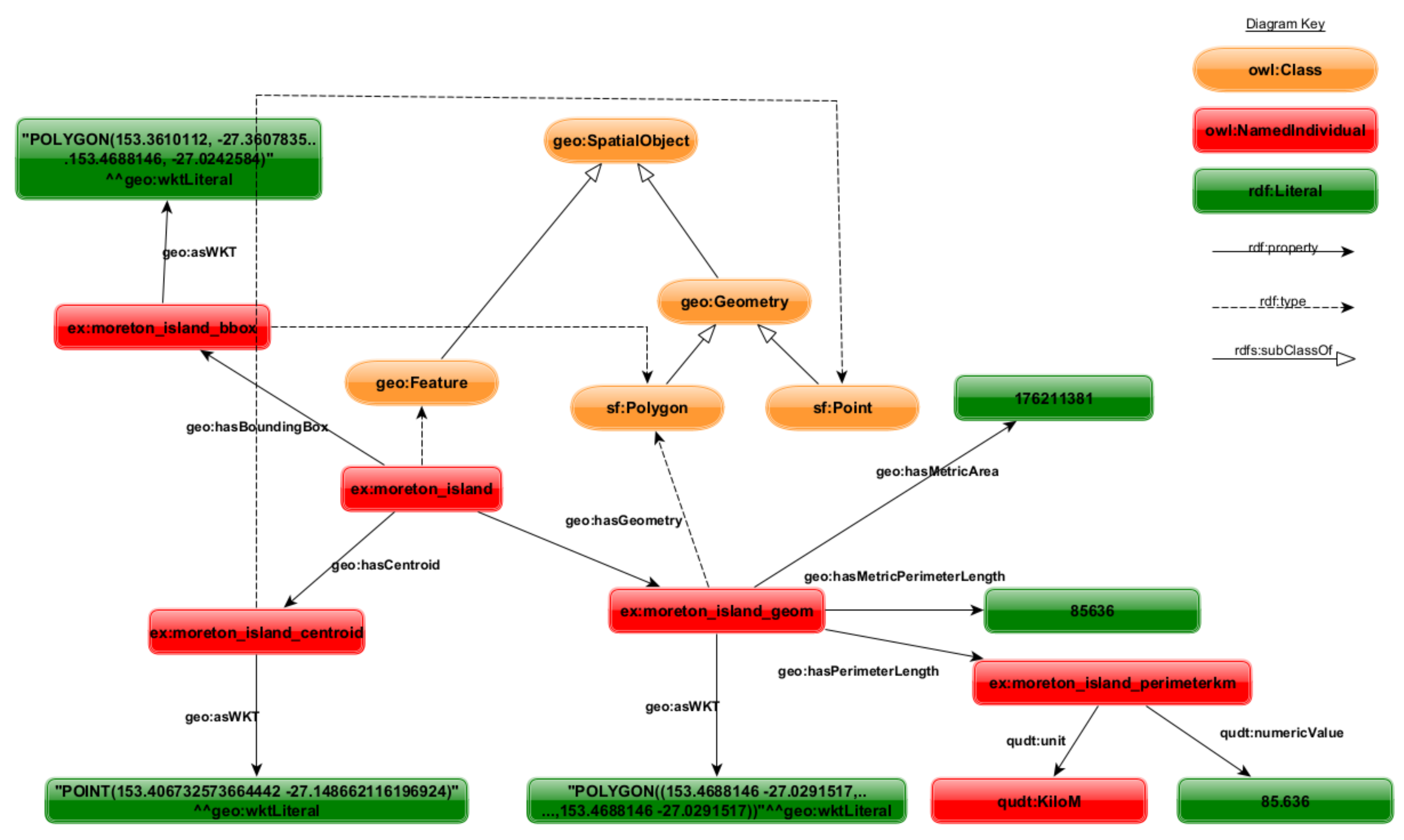

Figure 1 for an overview of the current, which is a redrawing of GeoSPARQL 1.1’s ontology overview diagram.

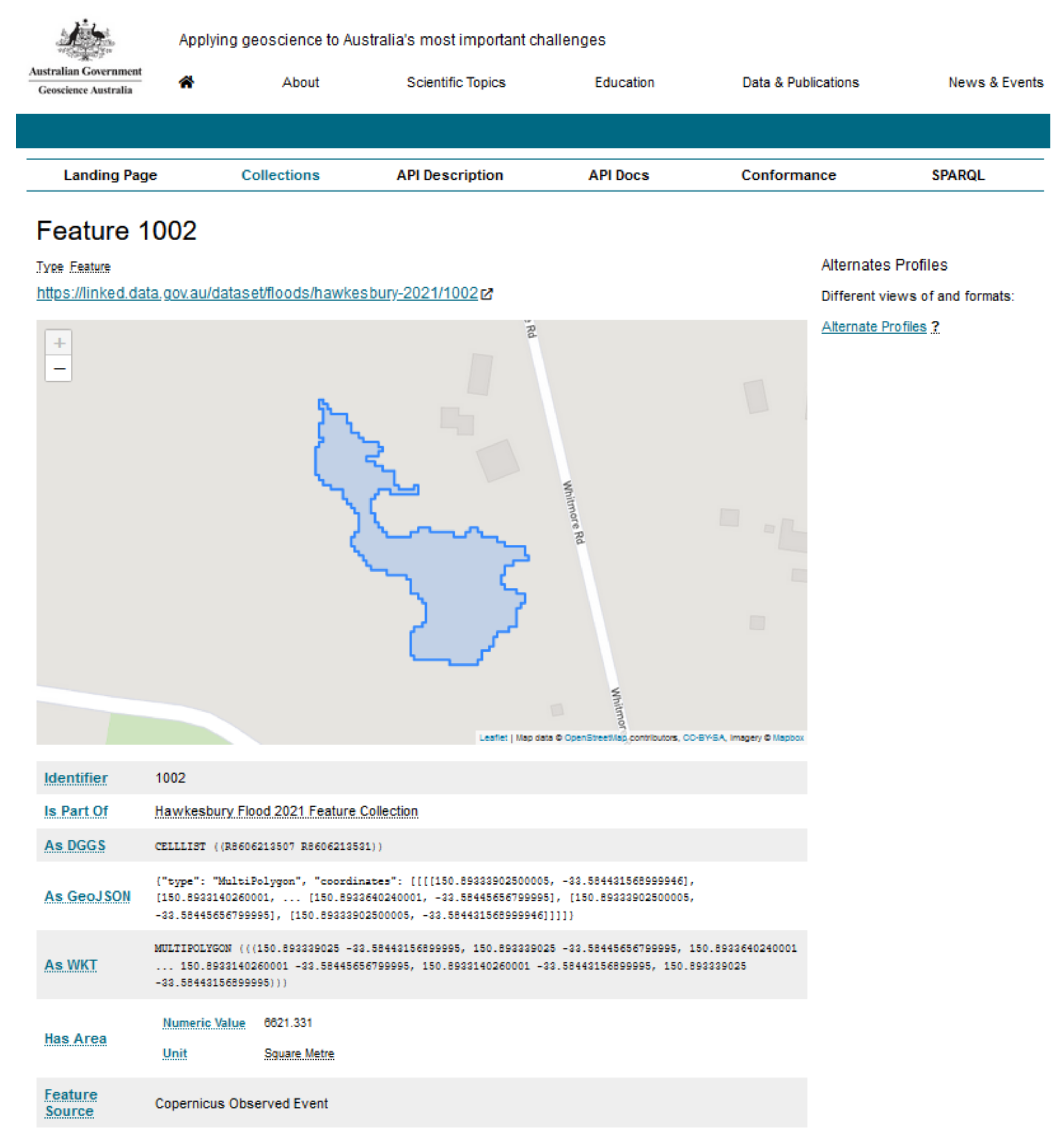

2.2.1. Scalar Spatial Properties

Scalar properties of spatial objects, such as a volume, length, can now be indicated in GeoSPARQL 1.1 with either a ‘metric’ property– one that indicates a literal value in meters–or a non-metric property that may indicate a measurement value and a unit of measure. The metric/non-metric property pairs are all sub properties of a generic ‘size’ property and have the domain of

geo:SpatialObject meaning they can be used with either

geo:Feature or

geo:Geometry instances. Properties pairs defined are:

The dual definition of metric and non-metric properties is aimed at allowing both simple and more detailed use. The metric properties are informally preferred for use. The SWG considered their inclusion only; however, the non-metric options were ultimately included to allow for the use of historic units for which no conversion to the metric system is known. Listing 1 shows two metric/non-metric pairs in use for the area and perimeter length, and

Figure 2 includes scalar spatial measure examples alongside other ontology implementation examples.

Listing 1.

Scalar spatial properties for the Australian federal electoral district of Brisbane.

Listing 1.

Scalar spatial properties for the Australian federal electoral district of Brisbane.

Inclusion of scalar spatial measurements within GeoSPARQL itself addresses concerns raised by the user community (see the SWG’s

Charter) that scalar spatial use with GeoSPARQL was occurring but that it was un-standardised or unguided and thus not necessarily interoperable. The particular pattern of non-metric scalar spatial measure chosen emulates common patterns for such measurements in ontologies such as the W3C’s

SOSA [

24,

25].

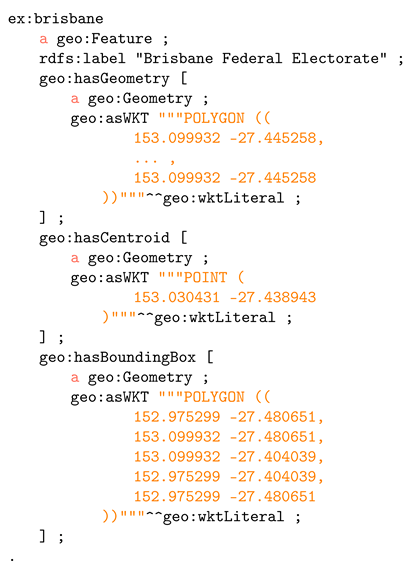

2.2.2. New Geometry Properties

GeoSPARQL 1.1 introduced more sub properties of

geo:hasGeometry. Where GeoSPARQL 1.0 defined only a single property of it,

geo:hasDefaultGeometry, GeoSPARQL 1.1 defines

geo:hasCentroid to indicate geometries with the role of centroid, and other, similar properties, such as

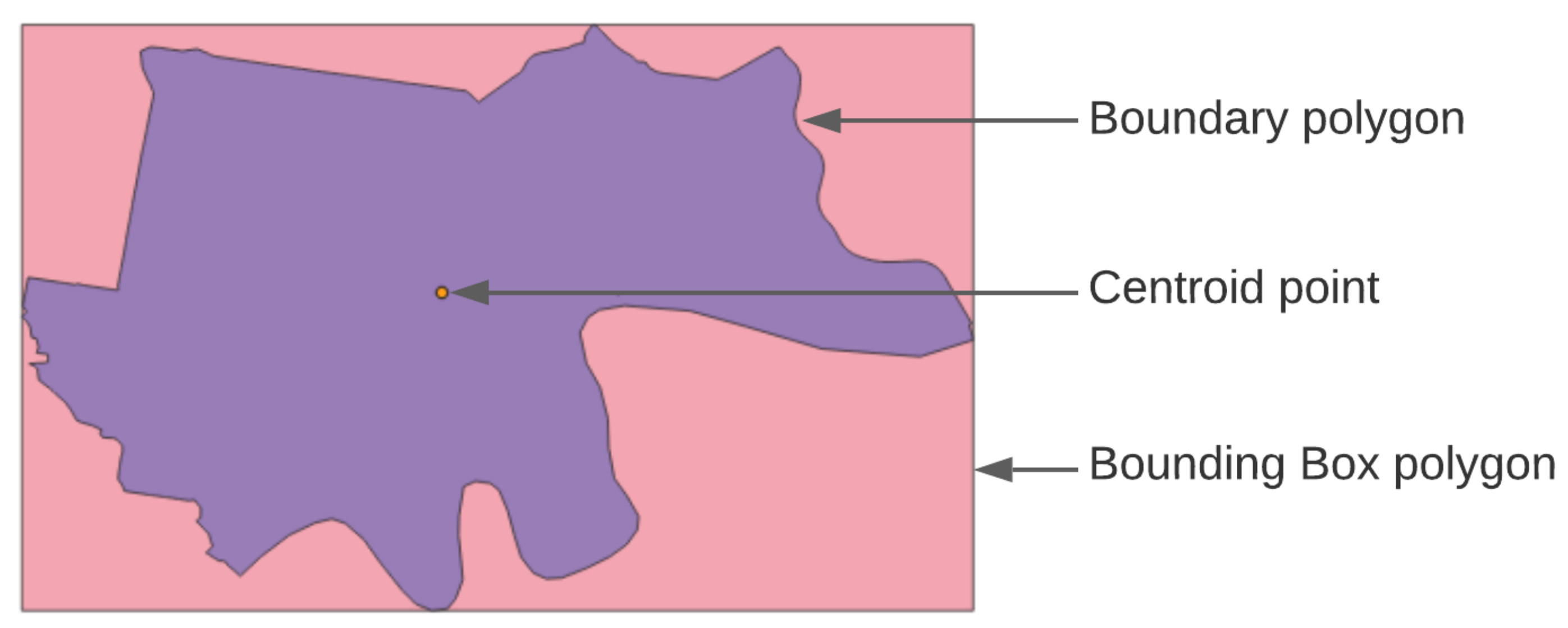

geo:hasBoundingBox.

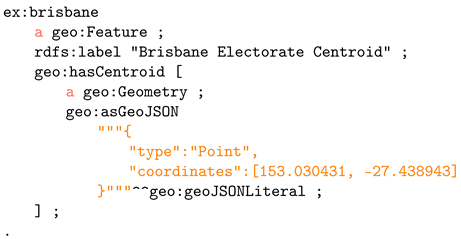

Figure 3 shows multiple geometries for a single feature and Listing 2 shows a representation of them in RDF with these new properties used.

The SWG recognised that there could be many more subproperties of

geo:hasGeometry added to GeoSPARQL 1.1 than the few they did ultimately add. However, no inclusion/exclusion logic was determined by the group nor properties deliberately excluded. One path for future exploration in this area mooted but not implemented for GeoSPARQL 1.1 was the concept of geometry roles–the nature of a geometry’s role with respect to a feature–and the SWG discussed creating a geometry roles vocabulary. This is noted again in

Section 5.

Listing 2.

A possible RDF representation of the elements in

Figure 3.

Listing 2.

A possible RDF representation of the elements in

Figure 3.

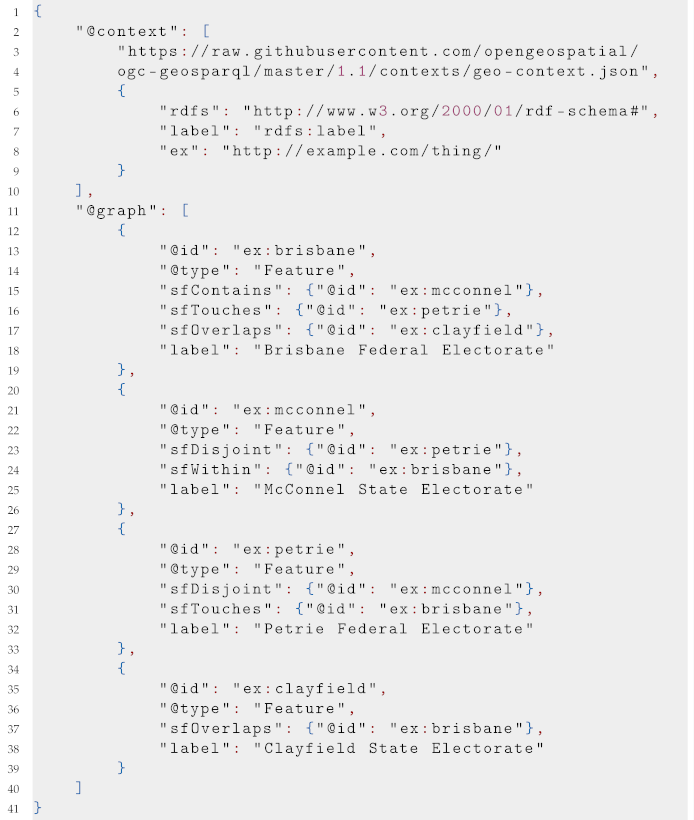

2.2.3. Topological Relations

GeoSPARQL 1.1 does not define any new topological relations or properties for them as compared to GeoSPARQL 1.0 (cf.

Table A1), however, the new specification version does include much more supporting material for users of these relations and GeoSPARQL in general, in particular examples of real-world geometry data represented in RDF according to GeoSPARQL 1.1.

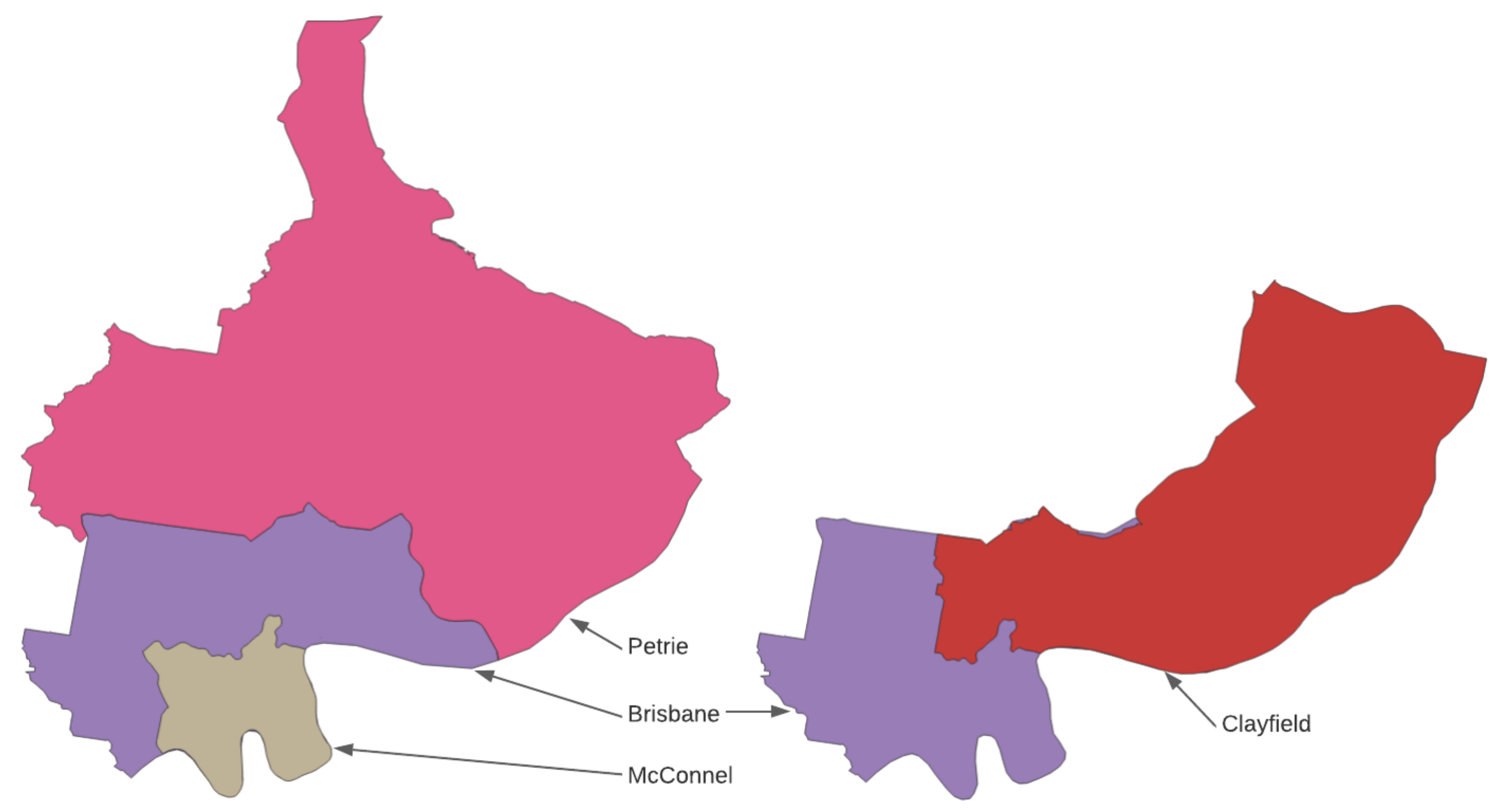

Figure 4 and its associated Listing, Listing 3, show the sorts of examples given in the GeoSPARQL 1.1 specification document (Annex C) as well as the GeoSPARQL repository of extended examples (

https://github.com/opengeospatial/ogc-geosparql/tree/master/1.1/examples, accessed on 30 October 2021).

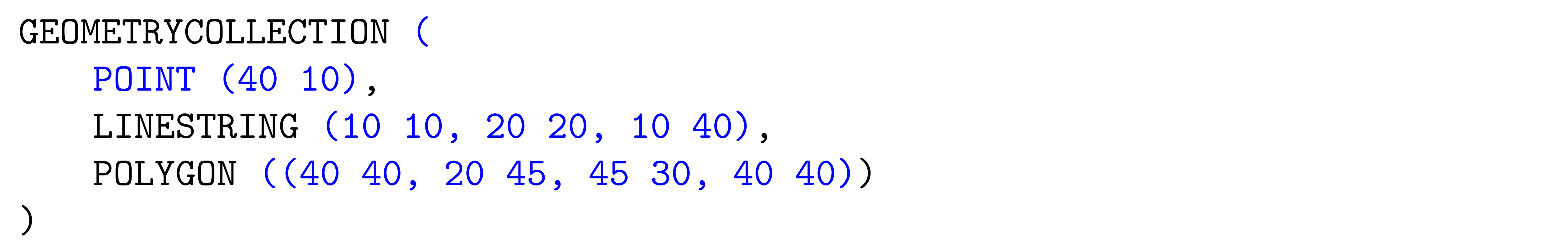

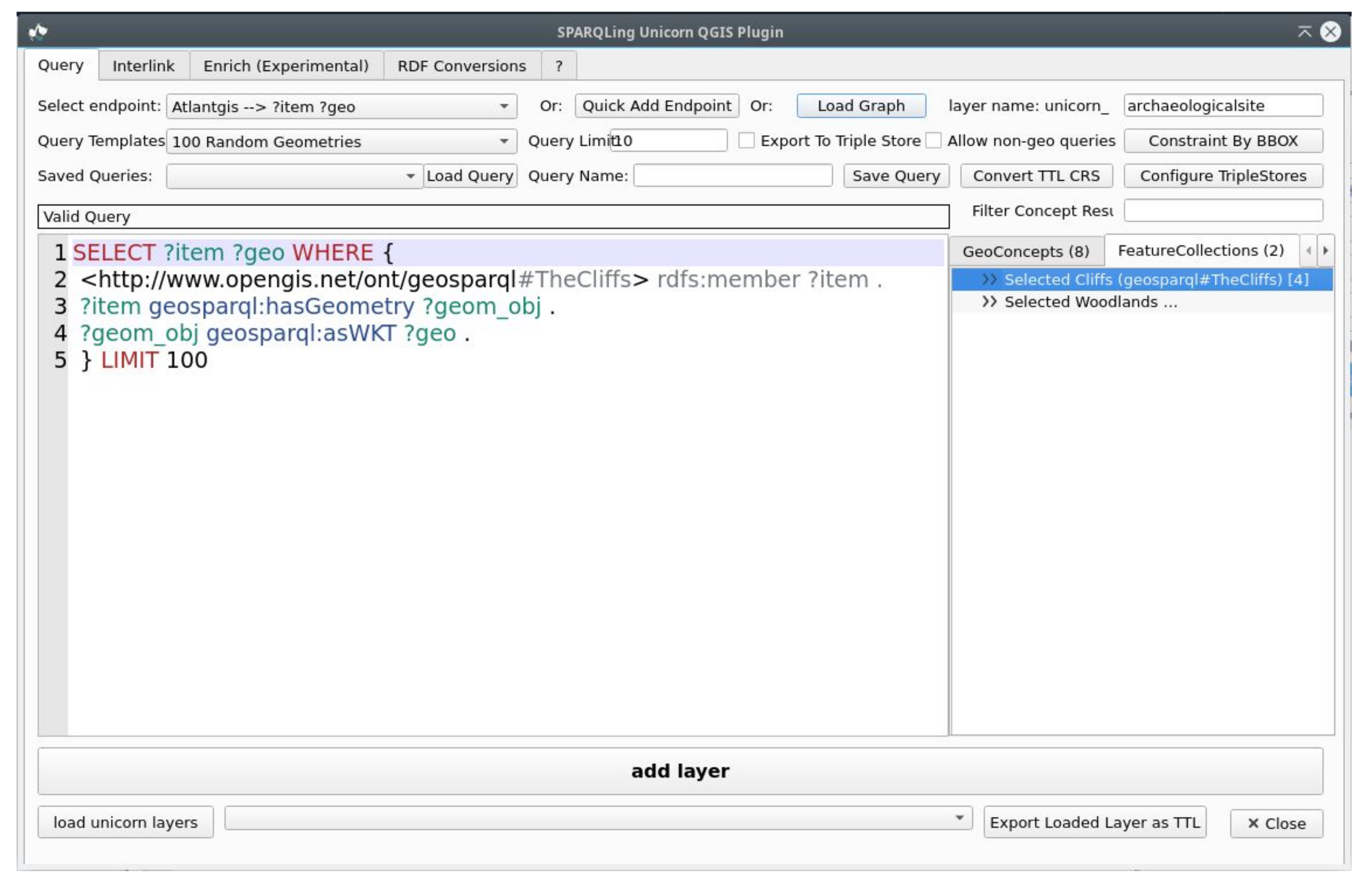

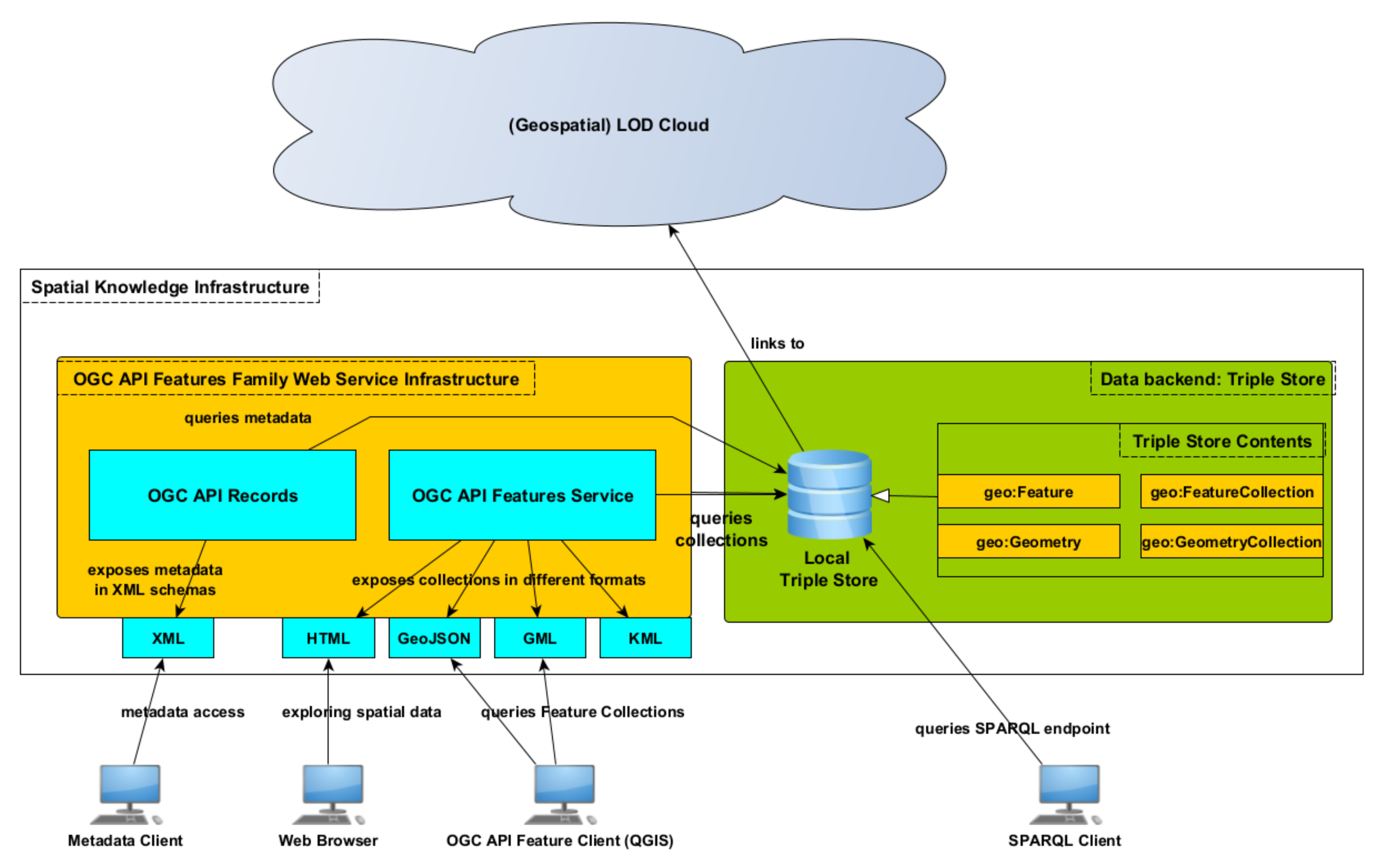

2.2.4. Support for Collections

GeoSPARQL 1.1 introduces support for collections of Features (

geo:FeatureCollection) and Geometries (

geo:GeometryCollection) which are both subclasses of the more general class

geo:SpatialObjectCollection. This allows for the grouping of features and geometries by specific attributes, and defined object collections in data are also required by standards such as the OGC’s

Features API [

26].

While the GIS community commonly organises geospatial features in the form of collections, including in software such as ArcGIS (

https://www.arcgis.com/, accessed on 30 October 2021) or QGIS (

https://www.qgis.org/, accessed on 30 October 2021), before the inclusion of specific collection classes in GeoSPARQL 1.1., GeoSPARQL data users had to implement virtual collections from the results of SPARQL queries for compatibility with many of their tools. This required more work on behalf of tool maintainers for tools such as the SPARQLing Unicorn QGIS plugin (

https://github.com/sparqlunicorn/sparqlunicornGoesGIS, accessed on 30 October 2021).

The SWG recognised that there is little semantic difference between virtual and defined collections from an OWL modelling point of view. However, they also recognised that other users of Semantic Web data might find defined collections much easier to use, hence their ultimate inclusion. This follows recent Semantic Web standards practice, for example, the creation of an extension to the W3C’s

SOSA ontology for observation collections [

27].

Listing 3.

A possible RDF representation of the elements in

Figure 4 in the JSON-LD format which imports the GeoSPARQL 1.1 profile’s JSON-LD context resource which allows for simpler JSON data representation through the use of locally-defined names. Supplementary context statements are also included for the example’s namespace and supporting namesaces–RDFS.

Listing 3.

A possible RDF representation of the elements in

Figure 4 in the JSON-LD format which imports the GeoSPARQL 1.1 profile’s JSON-LD context resource which allows for simpler JSON data representation through the use of locally-defined names. Supplementary context statements are also included for the example’s namespace and supporting namesaces–RDFS.

It needs to be remarked that the support of geometry collections in GeoSPARQL 1.1 does not replace the previously defined class

sf:GeometryCollection defined in the GeoSPARQL 1.0 Simple Features vocabulary. The

geo:GeometryCollection class can be used to group geometries which have been defined natively in RDF. The

sf:GeometryCollection class is used to define a GeometryCollection within a geometry literal, e.g., WKT Listing 4, which is therefore not modeled in RDF. Listing 4 exemplifies a GeometryCollection within a WKT geometry literal.

Listing 4.

GeometryCollection in WKT.

Listing 4.

GeometryCollection in WKT.

However, GeoSPARQL 1.1 improves the access to geometry collections defined in literal types by defining new SPARQL extension functions:

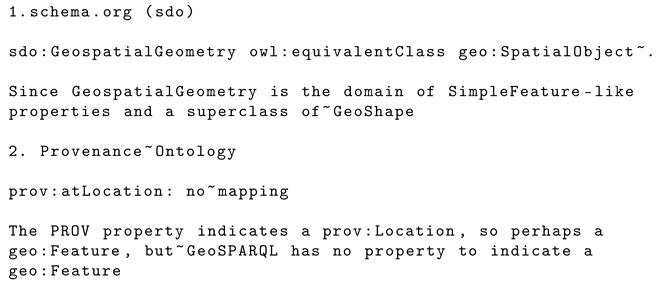

2.3. Ontology Alignments

GeoSPARQL may be the most widely used ontology to represent spatial data, but there are many other vocabularies in use which try to encode geospatial locations. Many of these ontologies, such as W3CGeo, Geonames or Wikidata representations of geolocations may only be used to encode point geometries. However, some vocabularies such as NeoGeo or schema.org, also allow for the representation of more complex geometries, for example in Well-Known-Text literals. Alignments with GeoSPARQL 1.1 and 15 other vocabularies containing spatial elements are presented in an Annex of the upcoming standard. In addition to written statements and tables of alignments, alignments have also been presented as RDF files for direct reuse in RDF databases. Listing 5 shows two individual alignments–from schema.org and from the Provenance Ontology–to exemplify their presentation in the standard: a direct class mapping and a property for which there is no mapping mapping.

Listing 5.

Two example mappings: a class mapping with schema.org and a non-mapping with a Provenance Ontology property.

Listing 5.

Two example mappings: a class mapping with schema.org and a non-mapping with a Provenance Ontology property.

2.4. New Geometry Literal Types

Three new geometry serializations are introduced in GeoSPARQL 1.1:

GeoJSON (Geo-JavaScript Object Notation) [

28].

KML (Keyhole Markup Language) [

29].

DGGS (Discrete Global Grid System) [

30].

2.4.1. GeoJSON & KML

GeoJSON & KML have been much anticipated and were requested by the SDWWG and many users of GeoSPARQL, due to those formats’ popularity. The DGGS format is more forward-looking in that it is not driven by user demand but by predicted demand.

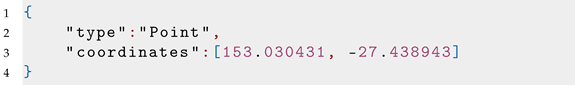

An example GeoJSON geometry, a point, representing the location of the centroid of the Brisbane electoral district from

Figure 3 is given in Listing 6, Listing 7 shows the same geometry in KML for comparison, and that geometry’s inclusion in GeoSPARQL 1.1. RDF is given in Listing 8.

Listing 6.

GeoJSON point geometry.

Listing 6.

GeoJSON point geometry.

Listing 7.

KML point geometry.

Listing 7.

KML point geometry.

In GeoSPARQL 1.1, geometry data formats that allow for feature information, such as GeoJSON, are limited to representing geometries only, to avoid possibly conflicting literal and RDF information. This is in keeping with GeoSPARQL 1.0, which imposed the same restriction on GML data. In the example in

Figure 3, GeoJSON is used to indicate the geometry type—

"type":"Point"—as well as give the geometry’s coordinates, but not feature annotations, such as name.

Keyhole Markup Language (KML) is a well-known, XML-based, GML-like geometry format. Its use in GeoSPARQL 1.1 is straightforward.

Listing 8.

A representation of the centroid point of the Brisbane electoral district from

Figure 3 in RDF (Turtle serialization) using the GeoJSON literal data from Listing 6.

Listing 8.

A representation of the centroid point of the Brisbane electoral district from

Figure 3 in RDF (Turtle serialization) using the GeoJSON literal data from Listing 6.

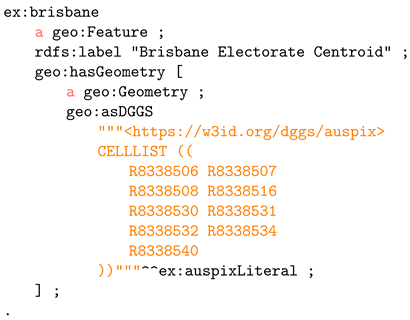

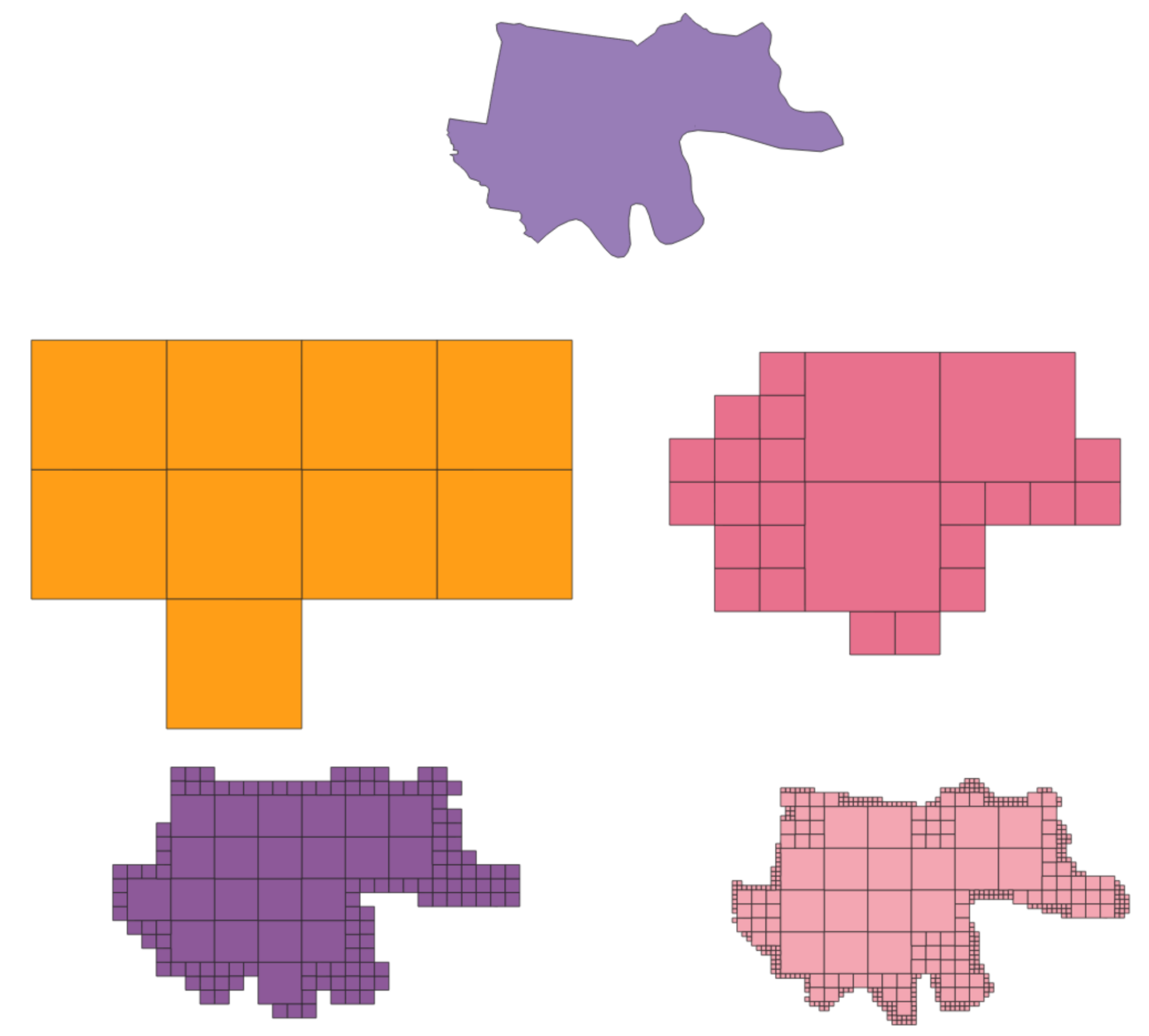

2.4.2. DGGS Literals

Discrete Global Grid System (DGGS) descriptions of spatial objects can be represented in GeoSPARQL 1.1 using literals too, and their inclusion in GeoSPARQL 1.1 took far more consideration than either GeoJSON or KML. Listing 9 gives an

AusPIX (

https://w3id.org/dggs/auspix, accessed on 30 October 2021) DGGS representation of the area of the Brisbane electoral district from

Figure 3.

Listing 9.

A DGGS geometry serialization example in RDF (Turtle) of the area of the feature in

Figure 3. The generic predicate for indicating a DGGS serialization—

geo:asDGGS—is used and the specific DGGS—

AusPIX—is indicated via use of a custom datatype

ex:auspixLiteral.

Listing 9.

A DGGS geometry serialization example in RDF (Turtle) of the area of the feature in

Figure 3. The generic predicate for indicating a DGGS serialization—

geo:asDGGS—is used and the specific DGGS—

AusPIX—is indicated via use of a custom datatype

ex:auspixLiteral.

GeoSPARQL 1.1 does not provide for specific DGGS literals, for example

AusPIX, directly but only for an abstract DGGS literal with the

geo:dggsLiteral datatype and the relevant

geo:asDGGS geometry property, hence the use of the example namespace

http://example.com/thing/ in Listing 9. This is because the DGGSes that currently exist, of which

AusPIX is just one, have vastly different representation formats. Users of GeoSPARQL 1.1’s

geo:asDGGS geometry property are expected to indicate the particular DGGS being used by implementations of custom literal datatype properties, as per Listing 9.

To assist with understanding what DGGS data is,

Figure 5 shows the data from Listing 9 as well as finer DGGS approximations of the Brisbane electoral district’s boundary polygon. DGGS such as

AusPIX represent areas, points, lines and other geometric shapes with collections of ‘cells’ of different sizes at different ‘levels’. There is no theoretical limit as to how many levels, and thus fine cells

AusPIX may use, thus too, no theoretical resolution limit.

2.4.3. Appropriateness of DGGS Data as Geometry Literals

The appropriateness of the addition of GeoJSON and KML to GeoSPARQL 1.1 as new geometry literal formats was uncontroversial, with the single consideration of substance being the exclusion of information other than geometry information from GeoJSON, as indicated above.

The inclusion of a placeholder or abstract property and datatype for DGGS literals was quite controversial due to differing perceptions of what DGGS data represents. The SWG members do not all agree that DGGS data represent geometries or features, and there is no straightforward theoretical case to be made for either due to DGGS’ novelty and mechanisms that are vastly different from traditional spatial data systems.

The SWG decided that the criteria for geometry representation in GeoSPARQL 1.1 were that the literals had to be able to act as geometry objects in order to satisfy at least some major proportion of the GeoSPARQL functions. Essentially, anything that could be used for spatial relations calculation and spatial aggregates could be treated, at least by GeoSPARQL 1.1, as a geometry literal.

During the first half of 2021, within the lifetime of the SWG, a software library was produced that implemented all the

Simple Features functions, except for

geof:sfCrosses (see

Section 3.1 for the implementation description). While not all

Simple Features functions were implemented for, nor were functions for the other families of spatial relations, the SWG determined that, given the implementation evidence so far,

AusPIX DGGS data could indeed act as geometry literals, from GeoSPARQL’s point of view. Thus, DGGS literals could satisfactorily act as geometries, at least from GeoSPARQL’s point of view. The SWG’s discussion on this matter is captured in their online code repository’s

Issue 112.

2.5. New Geometry Conversion Functions

GeoSPARQL 1.1 provides the conversion functions

geof:asWKT,

geof:asGML,

geof:asKML,

geof:asGeoJSON and

geof:asDGGS to convert between different literal types while considering the literal types capabilities. For example, a conversion of a WKT literal in the

EPSG:25832 coordinate system to either KML or GeoJSON will result in the geometry being converted to the World Geodetic System 1984, as this is the only coordinate reference system valid in the two respective literal types. Hence, a conversion from GeoJSON or KML to WKT will stay in the World Geodetic System 1984 coordinate reference system. To still be able to convert geometries to other coordinate reference systems, GeoSPARQL 1.1 adds the

geof:transform function, which converts a geometry literal to another coordinate reference system if the literal formats allow such a transformation.

With these additions, future triplestore implementations become very flexible in providing a variety of geometry conversions even without being dependent on another intermediate web service for coordinate/format conversions.

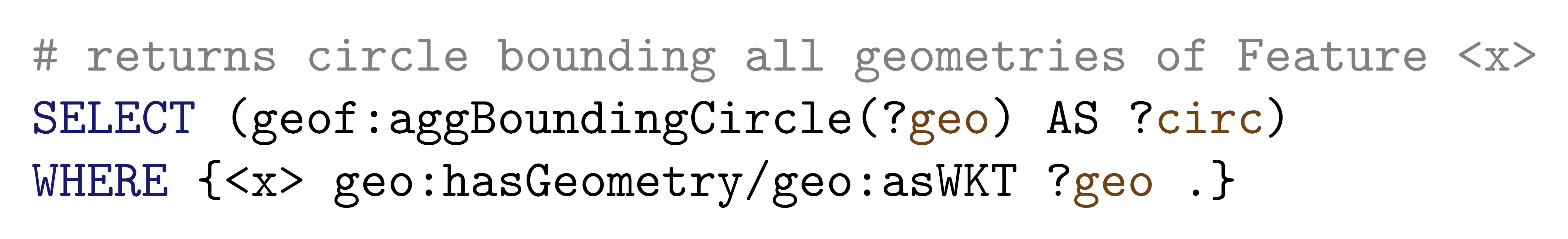

2.6. Spatial Aggregate Functions

While spatial aggregation functions are the norm in many non-semantic geospatial databases such as PostGIS or Oracle Spatial, at the time of defining the GeoSPARQL 1.0 standard, aggregation functions had not yet been introduced into the SPARQL standard, but have been with SPARQL 1.1 [

6]. Spatial aggregation functions similar to traditional (relational database) aggregation functions such as AVG, MAX, or MIN allow aggregated results of geometry queries, for example, to create the union of a set of selected serialised geometries. While calculating these aggregates is certainly possible outside of a semantic database, and thus GeoSPARQL, the inclusion of the functions provides distinct advantages:

No client-side library is needed to create an aggregated geometry result.

Fewer/more appropriate results are returned, for example a union result.

Federated SPARQL queries can aggregate results from multiple endpoints.

Listing 10.

Aggregation Function example SPARQL query.

Listing 10.

Aggregation Function example SPARQL query.

2.7. Comparison of Query Capabilities

It makes sense to determine how the new version GeoSPARQL 1.1 compares to other, also non-semantic query languages dealing with geospatial representations. We discuss the comparable query languages CQL [

31], Simple Features for SQL specification, and the PostGIS implementation extensions as the most typical representatives of spatial data query languages besides GeoSPARQL.

2.7.1. Common Query Language CQL

The Common Query Language CQL was developed for usage with OGC Web Services and provides filter capabilities for feature collection or coverage data. The CQL query language is also part of the currently in-development OGC API Features standard [

31], the successor specification to OGC web services. OGC API Features proposes using the Common Query Language (CQL) for filtering but is also open to other query language implementations such as GeoSPARQL. When comparing the filter capabilities of CQL to GeoSPARQL, one can observe that the two query languages provide comparable spatial functionality (cf.

Table 1). However, the CQL proposed supports spatiotemporal operators, which may be an addition to GeoSPARQL to be further explored in its continuous development process.

2.7.2. Simple Features for SQL

Another interesting comparison can be made between the query capabilities of GeoSPARQL and the Simple Features for SQL specification [

10]. To date, we can conclude that feature parity with the Simple feature specification has been reached with regards to the expression of geospatial relations using properties and using filter functions. Features still missing in the GeoSPARQL 1.1 standard are functions that specifically address attributes of particular geometry types. In that way, it is impossible to access specific points of LineStrings (such as start and end points) and their closedness in-query and the access of polygonal rings and single coordinates of points using query functions. These functions are planned to be implemented in an upcoming, possibly minor update to GeoSPARQL 1.1. We include a comparison table between SQL and the GeoSPARQL specification to highlight the differences in detail.

2.7.3. PostGIS Query Capabilities

In relational spatial databases, one may observe more types of spatial functions as compared to the Simple Features for SQL specification. In addition, more types of geospatial representations can be processed. Finally, one can look at comparable implementations in relational database systems, such as PostGIS. In particular, this is true for representing coverage data, i.e., rasters in PostGIS. The database features comparing raster data to vector data representations, raster algebra operations on raster, and further raster-specific modifications. These query capabilities are currently far beyond the capabilities of GeoSPARQL 1.1 and might be tackled in further development.

2.8. Shacl Shapes for Graph Validation

Since the adoption of SHACL [

23] as the recommended way to represent constraints on RDF graphs by W3C, the semantic web community has created shapes for various knowledge domains. These shapes fulfill different purposes, from checking the graph structure for consistency to checking the contents of the graph. Included with GeoSPARQL 1.1, there are SHACL shapes that validate the graph structure as defined in GeoSPARQL 1.1 in the following aspects:

Encouragement of a unified Geometry instance structure: GeoSPARQL 1.1 encourages geo:Geometry instances to only link to one serialisation. The intention behind this rule is that not all Geometry serialisations that GeoSPARQL 1.1 supports are 1:1 convertible. Users are still free to use more than one serialisation attached to a Geometry but should be warned about the fact that serialisations may not be 100% equivalent. A simple example of this non-equivalence can be seen when a geometry is associated with a WKT literal in a non CRS84 coordinate reference system and a GeoJSON literal. Because of a limitation of the GeoJSON literal to only accept one coordinate reference system, the literal values of these to literals cannot be equivalent.

Rudimentary checks of literal contents: Geometry literal contents are checked for plausibility. These checks do not contain the parsing of geometry literals and its validation but aim to check whether the contents of the geometry literal seem to be correct according to its literal type.

Correct usage of GeoSPARQL classes: Several SHACL shapes test the proper usage of GeoSPARQL classes. In particular, SpatialObjectCollections are expected to have at least one member relation, and

geo:Feature instances are expected to be associated to at least one

geo:Geometry instance, whereas each Geometry instance is expected to relate to at least one Geometry serialisation.

Geometry property consistency: Further SHACL shapes test for the consistency of values and cardinality of properties of a

geo:Feature or

geo:Geometry. For example, one SHACL shape tests the consistency of dimensionality properties of a

geo:Geometry.

For the scope of the standard, GeoSPARQL 1.1 stops at the definition of the aforementioned SHACL shapes. However, the SWG has identified the need for various research communities to define checks of geometry relations and further consistency checks of Geometry contents and their relations to each other. Independently of the efforts of the SWG [

32] introduced GeoSHACL for exactly this purpose and the SWG intends to found a community group for the collection of further useful validation shapes. Shapes will be created in a new Github Repository (

https://github.com/opengeospatial/ogc-geosparql-shapes, accessed on 30 October 2021).

We illustrate the usefulness of the defined GeoSPARQL 1.1 SHACL shapes using a minimum example in Listing 11.

Listing 11.

SHACL shape validation case: A geometry with a wrong literal type, two serializations, a missing connection to its corresponding feature and a non-connected FeatureCollection.

Listing 11.

SHACL shape validation case: A geometry with a wrong literal type, two serializations, a missing connection to its corresponding feature and a non-connected FeatureCollection.

The example shows possible common mistakes in GeoSPARQL graphs with respect to the aspects mentioned previously. Each mistake cannot be detected using OWL reasoning approaches. While an empty

geo:FeatureCollection and a non-connected feature instance are not necessarily wrong instances in a graph, we deem these as useless; hence they produce violations in a SHACL validation. Compared to this, using the wrong literal type (

xsd:string) or a wrong literal content (

geo:kmlLiteral for WKT content) is a clear error in applying the standard specification. The last issue, representing two serialisations connected to a geometry, is something noteworthy. Either the author of the given data is aware that geometries in different serialisations are not necessarily equivalent as precisions and CRS conversions might differ, or the author should consider creating different instances of geometry that can represent different aspects of geospatial data quality.

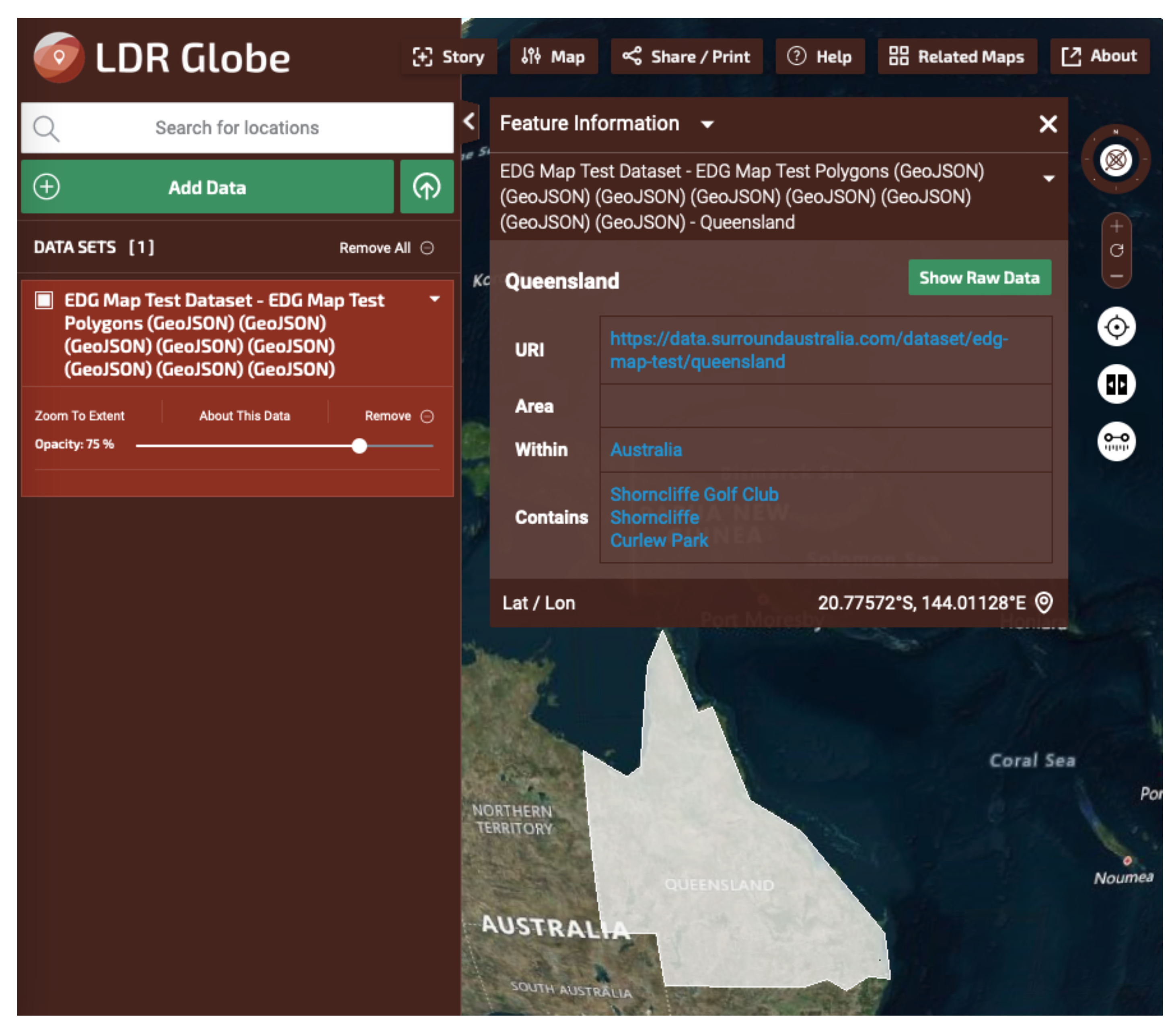

2.9. JSON-LD Contexts

GeoSPARQL 1.1 provides JSON-LD [

33] contexts for the Simple Features and GeoSPARQL vocabularies allowing for the publication of simpler representations of GeoSPARQL data. Listing 3 provides example data as context-less JSON, which can still be interpreted as RDF through its linking to the GeoSPARQL 1.1 JSON-LD context resource. Context-less JSON is simpler than the more verbose JSON-LD for systems to produce and for developers to understand. Presentation of a JSON-LD context for GeoSPARQL is also aimed at assisting implementors of APIs that wish to present both Linked Data API and OGC API Features [

26] interfaces: the context-less JSON will be far easier to incorporate into both required specifications’ outputs. Tests of such systems are in development (see

https://github.com/surroundaustralia/ogcldapi, accessed on 30 October 2021) for a combination of a Linked Data and OGC API framework and (

http://floods.surroundaustralia.com, accessed on 30 October 2021) for an instance of its use. This system plans to move its RDF payloads to context-less JSON).

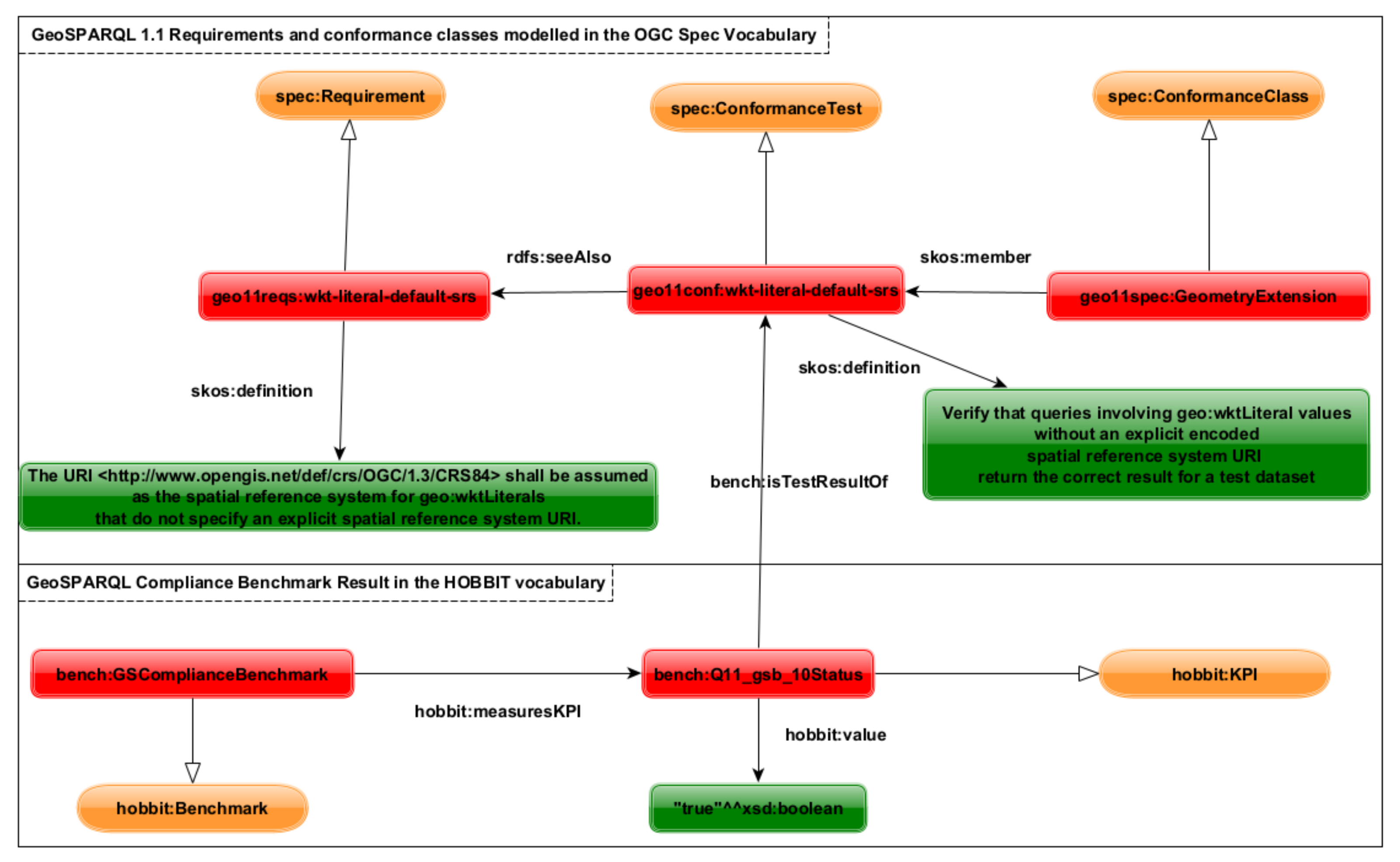

2.10. Requirements and Conformance Class Vocabulary

As the OGC mandates, all GeoSPARQL requirements and conformance classes are described using a URI. However, in the GeoSPARQL 1.1 specification, these unique identifiers are also modeled in RDF as part of the standard’s profile specification. This allows the combination of said vocabularies with different other RDF resources.

To date, we can see the usefulness of this design in two cases.

2.10.1. Compliance Benchmarking

Good practices of standards of any kind are that they are first defined and then implemented in reference implementations. To test whether the reference implementation and all following implementations fulfil the criteria that the given standard sets, compliance benchmarking can be used. [

13] created the first compliance benchmark for GeoSPARQL 1.0 using the HOBBIT benchmarking platform [

34]. Once an execution of the GeoSPARQL compliance benchmark is finished, it may produce a benchmark result in RDF (

https://github.com/hobbit-project/platform/issues/531, accessed on 30 October 2021). Since the definition of the GeoSPARQL 1.1 requirements and conformance class vocabulary, these results can now be related to the actual definitions of GeoSPARQL requirements in RDF as shown in

Figure 6.

The provision of benchmark results connected to requirements of a standard in RDF makes these results accessible as a machine-readable resource.

2.10.2. Partial Data Conformance Claims

In addition to systems claiming to implement GeoSPARQL functions, data may claim conformance to GeoSPARQL’s ontology. Such claims may be tested both with RDF reasoners and also with the use of the SHACL validators that GeoSPARQL 1.1 provides (see

Section 2.8). Since GeoSPARQL contains many parts, useful data may be created that is conformant to only part of GeoSPARQL, and the vocabulary of conformance classes allows for the indication of conformance of data to parts of GeoSPARQL, not just the whole.

Additionally, particular GeoSPARQL user communities might create more constrained SHACL validators to ensure that GeoSPARQL data conforms to a particular implementation pattern from a set of possible patterns. One example is the pattern whereby each geo:Feature is only associated with at most one geo:Geometry. In this case, a community could define additional conformance classes, like those in GeoSPARQL, and indicate data conformance to them too. Listing 12 shows a custom validator enforcing a restriction on GeoSPARQL 1.1 Features: that they must have one and only one GeoJSON geometry serialization.

Listing 12.

An custom GeoSPARQL Feature validator ensuring all Features have only one GeoJSON geometry representation.

Listing 12.

An custom GeoSPARQL Feature validator ensuring all Features have only one GeoJSON geometry representation.